Thursday, October 10, 2013

Better Off Ted: Bye Bye 'Bad' Part III

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now. If you missed Part I, click here. If you missed Part II, click here.

— Saul Goodman to Mike Ehrmantraut ("Buyout," written by Gennifer Hutchison, directed by Colin Bucksey)

By Edward Copeland

Playing to the back of the room: I love doing it as a writer and appreciate it even more as an audience member. While I understand how its origin in comedy clubs gives it a derogatory meaning, I say phooey in general. Another example of playing to the broadest, widest audience possible. Why not reward those knowledgeable ones who pay close attention? Why cater to the Michele Bachmanns of the world who believe that ignorance is bliss? What they don’t catch can’t hurt them. I know I’ve fought with many an editor about references that they didn’t get or feared would fly over most readers’ heads (and I’ve known other writers who suffered the same problems, including one told by an editor decades younger that she needed to explain further whom she meant when she mentioned Tracy and Hepburn in a review. Being a free-lancer with a real full-time job, she quit on the spot). Breaking Bad certainly didn’t invent the concept, but damn the show did it well — sneaking some past me the first time or two, those clever bastards, not only within dialogue, but visually as well. In that spirit, I don’t plan to explain all the little gems I'll discuss. Consider them chocolate treats for those in the know. Sam, release the falcon!

In a separate discussion on Facebook, I agreed with a friend at taking offense when referring to Breaking Bad as a crime show. In fact, I responded:

“I think Breaking Bad is the greatest dramatic series TV has yet produced, but I agree. Calling it a ‘crime show’ is an example of trying to pin every show or movie into a particular genre hole when, especially in the case of Breaking Bad, it has so many more layers than merely crime. In fact, I don't like the fact that I just referred to it as a drama series because, as disturbing, tragic and horrifying as Breaking Bad could be, it also could be hysterically funny. That humor also came in shapes and sizes across the spectrum of humor. Vince Gilligan's creation amazes me in a new way every time I think about it. I wonder how long I'll still find myself discovering new nuances or aspects to it. I imagine it's going to be like Airplane! — where I still found myself discovering gags I hadn't caught years and countless viewings after my initial one as an 11-year-old in 1980. Truth be told, I can't guarantee I have caught all that ZAZ placed in Airplane! yet even now. Can it be a mere coincidence that both Breaking Bad and Airplane! featured Jonathan Banks? Surely I can't be serious, but if I am, tread lightly.”

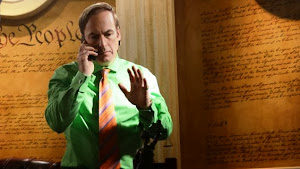

— Jonathan Banks as air traffic controller Gunderson in Airplane!

The second season episode “ABQ” (written by Vince Gilligan, directed by Adam Bernstein) introduced us to Banks as Mike and also featured John de Lancie as air traffic controller Donald Margulies, father of the doomed Jane. Listen to the DVD commentary about a previous time that Banks and De Lancie worked together. Speaking of air traffic controllers, if you don’t already know, look up how a real man named Walter White figured in an airline disaster. Remember Wayfarer 515! Saul never did, wearing that ribbon nearly constantly. Most realize the surreal pre-credit scenes that season foretold that ending cataclysm and where six of its second season episode titles, when placed together in the correct order, spell out the news of the disaster. Breaking Bad’s knack for its equivalent of DVD Easter eggs extended to episode titles, which most viewers never knew unless they looked them up. Speaking of Saul Goodman, he provided the voice for a multitude of Breaking Bad’s pop culture references from the moment the show introduced his character in season two’s “Better Call Saul” (written by Peter Gould, directed by Terry McDonough). Once he figures out (and it doesn’t take long) that Walt isn’t really Jesse’s uncle and pays him a visit in his high school classroom, the attorney and his client discuss a more specific role

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key

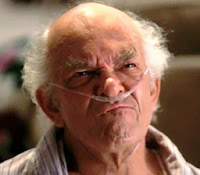

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.

players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.As I admitted, some of the nice touches escaped my notice until pointed out to me later. Two of the most obvious examples occurred in the final eight episodes. One wasn’t so much a reference as a callback to the very first episode that you’d need a sharp eye to spot. It occurs in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson) and I’d probably never noticed if not for a synched-up commentary track that Johnson did for the episode on The Ones Who Knock weekly podcast on Breaking Bad. He pointed out that as Walt rolls his barrel of $11 million through the desert (itself drawing echoes to Erich von Stroheim’s silent classic Greed and its lead character McTeague — that one I had caught) he passes the pair of pants he lost in the very first episode when they flew through the air as he frantically drove the RV with the presumed dead Krazy-8 and Emilio unconscious in the back. Check the still below, enlarged enough so you don’t miss the long lost trousers.

The other came when psycho Todd decided to give his meth cook prisoner Jesse ice cream as a reward. I wasn’t listening closely enough when he named one of the flavor choices as Ben & Jerry’s Americone Dream, and even if I’d heard the flavor’s name, I would have missed the joke until Stephen Colbert, whose name serves as a possessive prefix for the treat’s flavor, did an entire routine on The Colbert Report about the use of the ice cream named for him giving Jesse the strength to make an escape attempt. One hidden treasure I did not know concerned the appearance of the great Robert Forster as the fabled vacuum salesman who helped give people new identities for a price. Until I read it in a column on the episode “Granite State” (written and directed by Gould), I had no idea that in real life Forster once actually worked as a vacuum salesman.

Seeing so many episodes multiple times, the callbacks to previous moments in the series always impressed me. I didn’t recall until AMC held its marathon prior to the finale and I caught the scene where Skyler caught Ted about him cooking his company’s books in season two’s “Mandala” (written by Mastras, directed by Adam Bernstein),

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.I wanted this tribute to be so much grander and better organized, but my physical condition thwarted my ambitions. I doubt seriously my hands shall allow me to complete a fourth installment. (If you did miss Part I or Part II, follow those links.) While I hate ending on a patter list akin to a certain Billy Joel song, (I let you off easy. I almost referenced Jonathan Larson — and I considered narrowing the circle tighter by namedropping Gerome Ragni

& James Rado.) I feel I must to sing my hosannas to the actors, writers, directors and other artists who collaborated to realize the greatest hour-long series in

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

In fact, the series failed me only twice. No. 1: How can you dump the idea that Gus Fring had a particularly mysterious identity in the episode “Hermanos” and never get back to it? No. 2: That great-looking barrel-shaped box set of the entire series only will be made on Blu-ray. As someone of limited means, it would need to be a Christmas gift anyway and for the same reason, I never made the move to Blu-ray and remain with DVD. Medical bills will do that to you and, even if tempting or plausible, it’s difficult to start a meth business to fund it while bedridden. Despite those two disappointments, it doesn’t change Breaking Bad’s place in my heart as the best TV achievement so far. How do I know this? Because I say so.

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Cranston, D. Zucker, De Palma, Deadwood, Hackman, Hawks, HBO, J. Zucker, Jim Abrahams, K. Hepburn, O'Toole, Oliver Stone, Tracy, Treme, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, October 01, 2013

From the Vault: Natural Born Killers

BLOGGER'S NOTE: I originally wrote this review (with some additions for this event) upon Natural Born Killers' original 1994 release. I'm re-posting it for The Oliver Stone Blogathon concluding Oct. 6 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie LoverAs Mickey Knox lies on his motel bed, watching various violent films while images of Josef Stalin appear in the window behind him, he asks, "Why do they keep making all these fucking movies?" Good question, Mickey, but perhaps you should pose your query to the director of your movie because no amount of Oliver Stone's rationalizations will make Natural Born Killers original or worthwhile.

Forget The Doors. This film from the ever-controversial and increasingly dull (in all senses of the word) director marks the most extreme example yet of Stone spanking the monkey perpetually perched on his back. Quentin Tarantino* originally wrote the screenplay for Natural Born Killers, but Stone and co-conspirators David Veloz and Richard Rutowski butchered Tarantino's script to the point that he's now credited only with its story.

The film contains two halves: The first hour deals with a murder spree that companions Mickey and Mallory (Woody Harrelson, Juliette Lewis) undertake; the second chronicles the duo's incarceration and a live TV interview with Mickey by the host (Robert Downey Jr.) of a fictional tabloid TV series. The problems with Natural Born Killers accumulate at such a rapid pace that a thorough dissection of the film could end up as a thesis instead of a review. Stone, using what I assume must be either black magic, hypnotism or extortion, still manages to keep many film writers in his thrall to the point that they can't admit what a botch he's produced with Natural Born Killers. It's not that Stone can't be effective. He even made the silliness in the three-hour plus JFK entertaining despite the absurd claim that Kennedy was killed in order to stop the president from preventing the Vietnam War and, by extension, the need for Oliver Stone's film career. Stone's point-of-view concerning Natural Born Killers doesn't register anywhere near the realm of coherence.

The real subject — and I'm merely guessing — of Stone's awful opus aims at media obsession with sensationalism, certainly as timely as ever in the age of Tonya and Lorena, O.J. and the Menendez brothers. The number of usually reliable film fans who praise Natural Born Killers as original and fresh when no original idea resides in its empty little head amazes me. As usual, Stone proves as subtle as an 8.0 earthquake and twice as shaky (Exhibit A: See film still above). All the movie's points have been made before and better, from films dating back at least to 1967's Bonnie and Clyde, 1976's Network and even through the looking glass to 1931's The Front Page, which itself has been remade three times, the greatest being 1940's His Girl Friday

Stone also experiments more with film styles, alternating as he did in JFK between color, black and white, 16 millimeter, Super 8, video and even adds animation akin to graphic novels. Unlike JFK, these switches serve

no purpose other than to distract the audience. He also trots out other weird devices such as treating scenes with Mallory's monster of a father (Rodney Dangerfield) as if they exist in a TV sitcom, complete with laugh track and bleeped profanity — except for some reason some cuss words get bleeped and others don't. Of course, he can't resist tossing in some mystical Native Americans, just for good measure. It's hard to fault the performers (except for Tommy Lee Jones' inexplicable decision to play a prison warden as if he's imitating Reginald Van Gleason) since saving this mess would have been impossible for the greatest of actors, but at least Downey's wry performance injects some much-needed levity into this often tedious film. Downey appears to be the only actor aware that he's — in theory — signed on to the satire Stone believes he's making, but it's never a good idea to place a satire in the hands of someone without a sense of humor.

no purpose other than to distract the audience. He also trots out other weird devices such as treating scenes with Mallory's monster of a father (Rodney Dangerfield) as if they exist in a TV sitcom, complete with laugh track and bleeped profanity — except for some reason some cuss words get bleeped and others don't. Of course, he can't resist tossing in some mystical Native Americans, just for good measure. It's hard to fault the performers (except for Tommy Lee Jones' inexplicable decision to play a prison warden as if he's imitating Reginald Van Gleason) since saving this mess would have been impossible for the greatest of actors, but at least Downey's wry performance injects some much-needed levity into this often tedious film. Downey appears to be the only actor aware that he's — in theory — signed on to the satire Stone believes he's making, but it's never a good idea to place a satire in the hands of someone without a sense of humor. In the end, it's ironic that Natural Born Killers stars former Cheers regular Harrelson since a paraphrase of a question Frasier once asked Cliff on that show immediately sprang to my mind while watching this mess: "Hello in there, Oliver. Tell me, what color is the sky in your world?"

*BLOGGER'S NOTE: Shortly after seeing Natural Born Killers, I had the opportunity to interview Quentin Tarantino who was promoting Pulp Fiction. He shared his thoughts about how Stone changed his screenplay.

"Actually, to give the devil his due, he was very cool when I said I wanted to take my name off the screenplay. He facilitated that to happen. He could have caused a big problem, but he didn't. When it comes to Natural Born Killers, more or less the final word on it is that it has nothing to do with me. One of the reasons I wanted just a story credit was I wanted that to get across. If you like the movie, it's Oliver. If you don't like the movie, it's Oliver."

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Harrelson, Oliver Stone, Robert Downey Jr., Tarantino, Tommy Lee Jones

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, September 23, 2013

More than any of us can bear

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This review originally ran on this blog on Aug. 9, 2006. I'm re-posting it for The Oliver Stone Blogathon occurring through Oct. 6 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie Lover

By Edward Copeland

I finally caught up with Oliver Stone's World Trade Center and, as indicated by many reviews, it certainly qualifies as the least Oliver Stone-like film Stone has made (though Oliver can't resist tossing in a couple of ghostly images of Jesus in a light but hey, at least it wasn't a mystical Indian). World Trade Center does end up being Stone's best work in quite some time.

Like most Stone movies, it contains fat that could be lost easily and in the battle of 9/11 movies, I still prefer United 93, even though Stone's film contains good performances. Cage gives his best straight performance in ages. Yes, I loved him in Adaptation, but I can't remember the last time he played a dramatic role in a movie that wasn't a time-waster.

He's also ably supported by Michael Pena as the fellow Port Authority officer trapped with him beneath the rubble, and Maria Bello as Cage's wife and Maggie Gyllenhaal as Pena's wife, awaiting word on their husbands' fates. If I prefer United 93 to World Trade Center, it's for one main reason: the emotional wounds of 9/11 remain so fresh, that it seems almost unnecessary to tell personal, albeit true, stories to wring emotion from a viewer. The relative anonymity of the passengers depicted in United 93 touched me more deeply than the fleshed-out stories in World Trade Center did, especially when they tack on a lapsed paramedic (Frank Whaley) and a former Marine (Michael Shannon) who abandons his office job, throws on his old uniform and marches into Ground Zero to help.

World Trade Center depicts well the confusion and communications breakdowns on 9/11, where the first responders themselves don't realize that a second plane has hit the second tower until well after they've arrived on the scene of the first tower.

As you expect from a Stone production, his production team delivers top-notch technical aspects. While World Trade Center as a film comes off as Stone's finest in ages, it's difficult to compete with the real images we saw that day. Paul Greengrass found a way to accomplish that in United 93. While Stone's film offers good performances, somehow the personal touch ends up being less emotionally satisfying.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, M. Gyllenhaal, Maria Bello, Michael Shannon, Nicolas Cage, Oliver Stone

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, September 16, 2013

From the Vault: JFK

BLOGGER'S NOTE: I'm re-posting this review, originally written when JFK opened in 1991, as part of The Oliver Stone Blogathon occurring through Oct. 6 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie Lover

Seldom has reviewing a film proved as problematic as Oliver Stone's JFK. So much has been written about what is — and isn't — accurate in this film that I went in desperately trying to view solely on a cinematic basis, ignoring the fact that it concerns that fateful November day in Dallas in 1963. That sort of objectivity ends up being impossible because JFK demands evaluation and analysis and obliterates any chance of passive viewing with its strange hybrid of thriller, murder mystery and documentary.

Kevin Costner plays the lead in Stone's story as New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison, who launched a full-fledged investigation into the conspiracy he believed left both John F. Kennedy and the country mortally wounded. "Fundamentally, people are suckers for the truth," Donald Sutherland's Deep Throat-type character tells Garrison at one point in the film. While it remains to be seen whether Stone's version contains more truth than the preposterous idea that Lee Harvey Oswald (played well by Gary Oldman, part of the film's gargantuan, excellent ensemble) acted alone, fascination with the assassination keeps this three-hour film compulsively watchable.

Problems plague the film other than the ones that spark so much debate. Despite allegations that the film comes off as homophobic (I see why that charge has been leveled) or exists as nothing more than propaganda (could be), it fares fairly well. Stone keeps the pace speeding along most of the time except for a middle section that lags. His editing and jump-cuts that mix real footage, re-creations and original material triumph, especially in the film's very good opening segments. The movie stumbles the most when it presents scenes of Garrison's domestic life with his wife Liz (a thankless task given to the usually reliable Sissy Spacek, saddled with dialogue along the lines of "I think you care more about John Kennedy than your own family!") It also doesn't help that Garrison's son (played by Stone's own 7-year-old son Sean) never ages though the film covers more than half a decade.

Other demerits include John Williams' score, which nearly overpowers important scenes such as Sutherland's magnetic spinning of key elements of the "conspiracy" so that it makes sense as he's sharing it, and, it should really go without saying, Costner himself. While he manages to be fairly consistent with his Southern accent, he still can't emote effectively. He's a star, not an actor. Much of the popular opinion about the real Garrison refers to him either as someone seeking publicity or a crackpot. Regardless, Costner can't convey his obsession or possibly unstable nature. In his overrated Dances With Wolves, his lack of acting skills presented a similar problem. Both JFK and Dances would have been better served if they'd cast a performer capable of portraying people losing control. Lt. Dunbar tries to commit suicide and then asks to be placed on the frontier, but Costner couldn't pull off that conflict any more convincingly than he pulls off Garrison's drive for the truth.

Thankfully, able supporting performers abound to pick up the slack, even if they appear for a single scene. Actors deserving particular praise include Ed Asner, Kevin Bacon, John Candy, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Joe Pesci, Sutherland and Tommy Lee Jones, who gives a good performance despite the possible perception of his character as an offensive stereotype. Structurally, the film weakens in its final act by climaxing with Garrison's prosecution of Clay Shaw (Jones). While this conclusion comes naturally to a film focused on Garrison, it seems anticlimactic to the film's real subject — dealing with the demons of the past. Stone's obsession with the Vietnam era equals Garrison's with Kennedy's murder. Methods separate Garrison's obsession from Stone's. Stone uses cinema as his rosary to drag the audience kicking and screaming into his personal confessional. With JFK, that's not altogether inappropriate. Even people born since the assassination grew up with the myths and the facts of Nov. 22, 1963, as part of their lives, though for most of the younger of us, Jim Garrison and his actual prosecution of Clay Shaw was something few of us knew about until Stone's movie.

Growing up though with the history of the Kennedy and Martin Luther King assassinations ingrained in our brains shortened our attention span of shock when John Lennon, Reagan and Pope John Paul II encountered bullets in a period of just a few months. The explosion of the space shuttle Challenger seemed to affect us for only an hour or two instead of the lifelong effect JFK's assassination had on an earlier generation.

Personally, I don't know if I buy the revamped Garrison theory that Stone offers. I don't see how anyone can believe Oswald acted alone or all the shots came from behind — watching the Zapruder film enlarged on the big screen makes the "back and to the left" motion of Kennedy's head unmistakable. However, Stone can't quite pull off the idea that the reason Kennedy was killed was so the Vietnam War could happen.

In that respect, JFK plays like a murder trial where only the prosecution presents its case. I'm certainly no apologist for Oliver Stone and I think most of his films grow weaker on subsequent viewings. Indeed, his tendency to pass off fabrication as fact can be troubling when most viewers can't tell the difference. Reservations aside, JFK holds one's attention firmly and deserves a look.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Costner, D. Sutherland, John Williams, Kevin Bacon, Lemmon, Matthau, Oldman, Oliver Stone, Pesci, Spacek, Tommy Lee Jones

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, September 15, 2013

From the Vault: The Doors

BLOGGER'S NOTE: I'm re-posting this review, originally written when The Doors opened in 1991, as part of The Oliver Stone Blogathon occurring today through Oct. 6 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie LoverThe music was great. The man was out of control. The movie leaves a lot to be desired, namely a narrative. The film to which I refer goes by the name The Doors, though it should really be called Jim Morrison since the script by director Oliver Stone and J. Randal Johnson doesn't bother to depict the other band members with any depth.

Then lack of character development proves to be the major problem with this film. Near the beginning of the film, a 5-year-old Morrison vacations with his family in 1949 when they see the aftermath of a car wreck involving Navajos. The movie refers to the incident time and time again, apparently to explain why Morrison sets out on a path to self-destruction.

Alex Cox produced a much-better illustration of drugs sucking the life out of a talented individual in his 1986 film Sid & Nancy. Stone makes no secret of his admiration of Morrison, which makes me wonder how The Doors would have turned out if made by someone who didn't like Morrison since the resulting film comes off as spending 2 hours and 15 minutes with a truly repellent individual.

Val Kilmer does look and, in the live performance scenes, sound like Morrison, and his performance can't be faulted. Morrison comes off as a zonked-out prick and, since Stone worships him, you have to think that's an accurate portrayal. Then again, who's to say? The film creates a Morrison without any depth. It doesn't play him as a tortured artist or, in many ways, even a human being. He's just a doomed curiosity trapped in an extremely long music video — film as a hallucinogen, if you will.

The other members of The Doors may as well be cardboard cutouts for as much time and energy the film spends exploring them as individuals. Poor Kyle MacLachlan, trapped in a blond wig as Ray Manzarek, gets little more to do that sit at the keyboards, look concerned and occasionally defend Morrison in a DeForest Kelley-as-Dr. McCoy tone with lines such as, "Dammit, Jim's an artist."

The result comes off as even more despairing for the characters of Robby Krieger and John Densmore (Frank Whaley, Kevin Dillon), the other two members of the band. I don't know where Morrison and Manzarek met them. One scene, Ray suggests to Jim that they form a band. In the next, suddenly Krieger and Densmore complete the foursome.

Stone again finds himself trapped in the era of his obsession, namely the mid-1960s to the early 1970s, and, while the look rings true thanks to brilliant and stunning cinematography by Robert Richardson, the stilted dialogue borders on laughable, making me wonder if secret giggles lurk beneath the lines. On the plus side, Stone makes no assertions connecting the band to U.S. presence in Vietnam.

In many ways, the film reminds me of Tron, Disney's 1982 film about life inside a video game. That film looked great, but at its core offered nothing more than good graphics. The Doors stimulates visually, but doesn't engage the mind at all. In the end, it becomes nothing more than a meaningless assault on the senses about people who made good rock and roll between the sex and the drugs.

Stone, usually reliably opinionated, seems to lack a point of view here. He's neither defending Morrison nor chastising him. More importantly, the film lacks what much of Stone's work lacks — structure. When you go back and look at much of his body of work, Platoon, Wall Street and Born on the Fourth of July all fail to hold up on subsequent viewings, usually because of a lack of structure. Talk Radio remains the Stone film that holds up best because of its built-in structure of the radio broadcast. In The Doors, except for occasional reminders of the year, structure does not exist, just a drifting, mind-altering montage of events leading up to the inevitable discovery of Morrison in the bathtub. The most glaring example comes in a scene with Meg Ryan as Pamela, Morrison's "ornament." Jim finds Pam shooting heroin with another man and. in a rage, frightens her into a closet where he locks her in before setting the door ablaze. That's it. We hear no more about it. Twenty minutes later, Pam shows up at a recording studio. In the film's context, it's unclear that it's even the same time period as when he lit the fire and nothing explains her escape.

There are moments of fun, such as Crispin Glover's cameo as Andy Warhol and Stone's own brief ironic appearance as Morrison's UCLA film professor accusing Jim of being pretentious.

The Doors produced great music, but this film doesn't attempt to look behind the talent. Instead, it just shows an unpleasant man marching to his own beat on the way to his doom.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Blog-a-thons, Kyle MacLachlan, Meg Ryan, Oliver Stone, Val Kilmer

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, March 12, 2012

Is the magic and the meaning in the movies or ourselves?

was meant perhaps to suggest a mixture of horror movie and automated toyshop, but now just provides noisy irritation. Films

have become a lot quieter since then — at least in the music department. And above all the acting seems weirdly dated,

with its deliberately sought-out stiffness and posing.…Now the performance just looks arch, and we know that stylisation in film requires more extreme measures — a real marionette-effect, for instance. It's notable that in this film Resnais succeeds best

with his anti-naturalist note when the actors are either quite still — so still you don't know whether they are in a moving picture

or a photograph — or dancing, rocking slowly, dully, to the sounds of an unearthly waltz.”

— Michael Wood, The Guardian, July 14, 2011

By Edward Copeland

The above quote appeared in a piece Wood wrote on the occasion of a 50th anniversary engagement of Last Year in Marienbad. Despite the way it reads, Wood's overall tone was positive. Putting aside that he must not go to new movies that often if he thinks film scores today have become a lot quieter, his words about the acting in Marienbad struck me as another reason why Resnais' film entrances me in a way other films that could be called "similar" don't. I can't imagine anyone, fan or foe of the film, watching it thinking that acting or

characterization had occurred in Marienbad or even had been desired. Using the actors as props but attempting to make them "real" in other movies that could be lumped into the same category as Marienbad might be why works by a filmmaker such as Lars von Trier or each successive effort by Terrence Malick don't: They go to the trouble of pretending they care about narrative storytelling and their poor performers, such as a Kirsten Dunst in Melancholia or a Sean Penn in The Tree of Life, try to create characters in universes where that doesn't matter. At least Resnais and Robbe-Grillet made it clear to everyone that the actors' importance equaled that of the ceiling fixtures (probably less) in Marienbad so that doesn't get in my way. It's been a progression for Malick. His film that I tolerated best was Badlands. Then came Days of Heaven, pretty but blah with a voiceover from a poorly educated person with a Southern accent waxing philosophical as if she were in a Coen brothers movie, only not doing it for laughs. It got even worse in The Thin Red Line, so much so that I skipped The New World (with its Clue-like 15 different versions) entirely. So many spoke glowingly about The Tree of Life (I even let my contributior J.D. run a positive review of it before I saw it), even people who didn't care for The Thin Red Line, that I decided I'd give The Tree of Life a chance and went in with an open mind. I should have known better. Malick and I just aren't cut out for each other. I've been saying for a long time he really should be a nature documentarian because narratives aren't his forte. I can feel the anger of his fans exercising their fingers to beging composing their replies. Now, I didn't just write my anti-Malick feelings to get a rise out of them but also to remind people of one of the central objectives of this second, more generalized Marienbad-inspired post: All opinions about movies are subjective. Before we move on, just to calm the Malick fans before I whack on Lars von Trier, check out this interview with my good friend Matt Zoller Seitz, an ordained archbishop in the Church of Terrence Malick, and his five-part video essay series on Malick's films from Badlands through The Tree of Life for The Museum of the Moving Image.

characterization had occurred in Marienbad or even had been desired. Using the actors as props but attempting to make them "real" in other movies that could be lumped into the same category as Marienbad might be why works by a filmmaker such as Lars von Trier or each successive effort by Terrence Malick don't: They go to the trouble of pretending they care about narrative storytelling and their poor performers, such as a Kirsten Dunst in Melancholia or a Sean Penn in The Tree of Life, try to create characters in universes where that doesn't matter. At least Resnais and Robbe-Grillet made it clear to everyone that the actors' importance equaled that of the ceiling fixtures (probably less) in Marienbad so that doesn't get in my way. It's been a progression for Malick. His film that I tolerated best was Badlands. Then came Days of Heaven, pretty but blah with a voiceover from a poorly educated person with a Southern accent waxing philosophical as if she were in a Coen brothers movie, only not doing it for laughs. It got even worse in The Thin Red Line, so much so that I skipped The New World (with its Clue-like 15 different versions) entirely. So many spoke glowingly about The Tree of Life (I even let my contributior J.D. run a positive review of it before I saw it), even people who didn't care for The Thin Red Line, that I decided I'd give The Tree of Life a chance and went in with an open mind. I should have known better. Malick and I just aren't cut out for each other. I've been saying for a long time he really should be a nature documentarian because narratives aren't his forte. I can feel the anger of his fans exercising their fingers to beging composing their replies. Now, I didn't just write my anti-Malick feelings to get a rise out of them but also to remind people of one of the central objectives of this second, more generalized Marienbad-inspired post: All opinions about movies are subjective. Before we move on, just to calm the Malick fans before I whack on Lars von Trier, check out this interview with my good friend Matt Zoller Seitz, an ordained archbishop in the Church of Terrence Malick, and his five-part video essay series on Malick's films from Badlands through The Tree of Life for The Museum of the Moving Image.

As for Von Trier, we got off on the wrong foot with poor Max von Sydow's voiceover leading the somnambulistic tone of Zentropa. Somehow Emily Watson overcame his traps to give a good performance Breaking the Waves, which I otherwise rejected. I admit that I still would like to see The Kingdom and I liked Dancer in the Dark. Never saw The Idiots. Never wanted to see Dogville. The Five Obstructions sounds interesting as an experiment, not necessarily a movie. Perhaps a reality TV show. Then came Melancholia — ay caramba — though you definitely see the Marienbad influence there: He even had similarly sculpted trees. If you want to see a 2011 film that involves the sudden appearance of a planet in the sky, rent the indie Another Earth. It's shorter, better written and contains actual characters. It will mean sacrificing Udo Kier's appearance as a wedding planner complaining that the bride ruined his work. I'm certain I've said enough in this section to get blood pressures boiling, so now I can move on to what too many people — both moviegoers and critics alike — tend to do: Take what's said about their favorite movies and filmmakers way too seriously. Forgetting that the things I wrote above are my opinion and, more importantly, opinions about movies and filmmakers. This is hardly the equivalent of, let me think of a recent example, Rush Limbaugh calling a law student testifying to Congress about a friend's medical reason for access to contraceptives a slut who must have lots of sex and if health insurers cover female contraceptives, he should be allowed to see tapes of her having sex on his computer. Big difference between that and me saying I don't think Melancholia is a good movie. I'm giving a subjective opinion. Rush is being an asshole.

Thinking about how upset people can get when a favorite film has been attacked takes me back to my days as a working critic. I usually received angry letters or phone calls, since my paper fortunately didn't run movie critics' photos. I preferred anonymity, like a food critic. Ironically, given my physical state now, I once received a letter from an organization for disabled people taking me to task for referring to a character in a movie as being "confined to a wheelchair." They were right and I never used that phrase again even before I learned the hard way why those words are inaccurate. I recall the woman who called the day I gave The Beverly Hillbillies movie the smackdown it so richly deserved. (That's one plus to this nonprofit blog thing — with the exception of my

obsession of trying to see all the major Oscar nominees each year, I only see what I want. I feel sad for those few remaining paid critics who still have to sit through Adam Sandler movies.) Anyway, this woman called almost as soon as I arrived in the office that morning to harangue me about the bad review — even though she hadn't seen the movie. What cracked me up was her question: "Do you think the people who made that movie appreciate you writing those things about their film?" I didn't have phone numbers for Penelope Spheeris or any of the cast members to get the answer. The absolute funniest phone call came from an older-sounding man horrified because I'd given something a good review. It was the Monday after The Crying Game opened in our city. I already had placed it at No. 1 on my 10 best of 1992 list, but its January 1993 opening gave me the first chance for a full-fledged review. The man couldn't believe I liked that movie. "It made me ill," he told me. "I felt like I needed to take a shower afterward." It took every ounce of restraint I could muster not to respond, "You found Jaye Davidson attractive, eh?" The final one isn't really funny and it took place in person. I was heading to a dreaded radio-promoted screening of something and I stopped by the concession stand to get a drink. The kid working knew who I was and gave me an unmistakably dirty look, so obvious that I had to ask what was wrong. "I used to respect you. Your reviews were the only good ones that paper ever had," he said. I asked him what I did wrong. Turned out that he couldn't believe how I tore apart Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers. He was working and so was I, so I didn't have time to try to explain subjectivity or how great I thought Pauline Kael was though I probably disagreed with her more than I agreed, but what can you do?

obsession of trying to see all the major Oscar nominees each year, I only see what I want. I feel sad for those few remaining paid critics who still have to sit through Adam Sandler movies.) Anyway, this woman called almost as soon as I arrived in the office that morning to harangue me about the bad review — even though she hadn't seen the movie. What cracked me up was her question: "Do you think the people who made that movie appreciate you writing those things about their film?" I didn't have phone numbers for Penelope Spheeris or any of the cast members to get the answer. The absolute funniest phone call came from an older-sounding man horrified because I'd given something a good review. It was the Monday after The Crying Game opened in our city. I already had placed it at No. 1 on my 10 best of 1992 list, but its January 1993 opening gave me the first chance for a full-fledged review. The man couldn't believe I liked that movie. "It made me ill," he told me. "I felt like I needed to take a shower afterward." It took every ounce of restraint I could muster not to respond, "You found Jaye Davidson attractive, eh?" The final one isn't really funny and it took place in person. I was heading to a dreaded radio-promoted screening of something and I stopped by the concession stand to get a drink. The kid working knew who I was and gave me an unmistakably dirty look, so obvious that I had to ask what was wrong. "I used to respect you. Your reviews were the only good ones that paper ever had," he said. I asked him what I did wrong. Turned out that he couldn't believe how I tore apart Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers. He was working and so was I, so I didn't have time to try to explain subjectivity or how great I thought Pauline Kael was though I probably disagreed with her more than I agreed, but what can you do?

The other issue I wanted to address was whether meaning matters, though the person who responded most specifically to that query answered it more than 45 years ago and died nearly seven years ago. Susan Sontag's "Against Interpretation" struck me like a lightning bolt this week, probably quite annoyingly since I imagine many out there had read it long ago and I'm cheerleading it as if I just found out the world was round and am telling everyone I know. Sontag quotes a famous saying by D.H. Lawrence that I had heard before that might be the most concise warning against reading too much into art, be it literature or film: "Never trust the teller, trust the tale.” Sontag drops his line into Part 6, which I quoted a couple times in my review. She also writes there, "Interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art. It makes art into an article for use, for arrangement into a mental scheme of categories." Sontag carries it further, questioning (in 1966 remember) what role criticism should take. In Part 8, Sontag wrote:

"What kind of criticism, of commentary on the arts, is desirable today? For I am not saying that works of art are ineffable, that they cannot be described or paraphrased. They can be. The question is how. What would criticism look like that would serve the work of art, not usurp its place?

What is needed, first, is more attention to form in art. If excessive stress on content provokes the arrogance of interpretation, more extended and more thorough descriptions of form would silence. What is needed is a vocabulary — a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, vocabulary — for forms. The best criticism, and it is uncommon, is of this sort that dissolves considerations of content into those of form.…

Equally valuable would be acts of criticism which would supply a really accurate, sharp, loving description of the appearance of a work of art. This seems even harder to do than formal analysis."

Her essay really builds up a head of steam, so by the time she reaches Part 9, Sontag's words ignite a virtual bonfire of ideas, ideas that she had placed on paper decades earlier that I'd said and thought often before without knowing her essay existed. Part 9 added more to contemplate:

"Interpretation takes the sensory experience of the work of art for granted, and proceeds from there. This cannot be taken for granted, now. Think of the sheer multiplication of works of art available to every one of us, superadded to the conflicting tastes and odors and sights of the urban environment that bombard our senses. Ours is a culture based on excess, on overproduction; the result is a steady loss of sharpness in our sensory experience.…

What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.

Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all.

The aim of all commentary on art now should be to make works of art — and, by analogy, our own experience — more, rather than less, real to us. The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means."

"Against Interpretation" is an essay divided in 10 sections, though Sontag's last section consists of a single sentence calling for "an erotics of art." As I've said, I've never been one who spent much time trying to decipher a film's meaning. As I read Sontag's essay, the words sounded like an echo of my present sent from someone else's past. When Sontag added how overburdened her senses were — in the early to mid-1960s — compared to the overload now, it was as if I'd found a holy text by accident — but I promised you a punchline and I will give it to you, but first I'm going to share all the friends kind enough to contribute to this with thoughts on Last Year at Marienbad, films they love but can explain, style vs. substance, etc. Thanks to all who replied. Here they are, in alphabetical order:

"I would offer Syndromes and a Century as a movie that defies conventional understanding yet totally transported and transformed me: I left the theater in an elated state, but not sure how I got there. Couldn't begin to tell you what it 'means': there's no 'story' in the usual sense, yet I knew I was in the presence of a masterful filmmaker casting a spell I didn't want broken. Apitchapong Weerasethakul's films are both abstract and down to earth, so that they never feel pretentious the way, say, the late (Theo) Angelopoulos often did, where every gorgeous frame asked you to admire his (sometimes ponderous) brilliance. But of course many people find these Thai films baffling and boring. Chacun a son gout."

"Great art fills you with awe and wonder — whether it’s through substance, a particular style (the hallmark of a great artist, who may eventually seem like a friend on the same mental wavelength as you) or usually some combination of both. Being able to explain it eventually helps, but ultimately art is an emotional experience that changes you or takes you to a different place. If you are in the same frame of mind afterward as you were at the beginning, it’s probably not great art."

(1) “Why does Movie X work for me, but not for Critic A or others?” Because something “working” is a two-way street between the text and each member of the audience. We all have movies we love that we know we shouldn’t, and we all have movies we greatly admire

but dislike. There’s no accounting for taste.

but dislike. There’s no accounting for taste.(2) “How can a director…have either fans who think he walks on water or people such as myself who mock him mercilessly but seemingly few who look at him dispassionately from the middle ground?” In the case of Lars von Trier, it’s because he’s an agitator; his work is designed to provoke extreme reactions, and he wants you to either love or hate his movies — and I think he’d actually prefer you hate his work. (I’m actually on the dispassionate middle ground with him.) And remember that critics have agendas, too; some are simply provocateurs. More generally, directors/authors make connections with some people and not with others.

(3) “Does the magic reside in the movies or within ourselves?” Yes! The best critics don’t merely provide summary judgment; they show you how something worked or didn’t work for them. Essentially, they’re articulating and supporting a deeply personal reaction.

"'Substance' is such an abstract term when it comes to any discussion of the movies; I suppose, if you go by the conventional definition, Amistad has substance, whereas Bringing Up Baby does not…but does anyone reading this regard the Spielberg entry as the superior example of the filmmaker's craft? I think you need to accept each and every film on its own terms, and judge them based on how well they succeed in achieving their own objectives; you can't measure them all by the same scale, and it's probably a mistake to use subject matter, or even stylistic aesthetics, as your guide in determining the worth of any particular enterprise. There isn't a particular 'type' of film that I'm more inclined to like more than any other — you take them all on an individual basis (in reference to Marienbad, which I haven't seen, there are some very oblique films — The Tree of Life is a recent example — that have really connected with me…whereas others have left me absolutely cold.) That's the nature of the beast — whether it's gourmet cooking from a Five-Star Chef, or a damn good cheeseburger, a good eat is a good eat."

"I've always been a big believer in the idea that style is substance. I like this quote I found in the comments section of a Jim Emerson blog post: 'Style is supposed to express content, dammit — not disguise a lack of it! The meaning of a film is in what these images on the screen (and don't forget the sounds!) do to you while you experience them. (As you so eloquently put it: a film is about what happens to you when you're watching it.) If you ask me, we should stop seeing style and content as separate entities. In a good film, they're a natural unity.' I understand that this person is using 'content' instead of 'substance,' but I thought it still applied here. In fact, I liked it so much I used it as one of my blog's epigraphs."

"I, too, like Last Year at Marienbad. I like Delphine Seyrig. The formal garden. The chorus line of cypresses. It had the order and mystery of a de Chirico painting. I've often wondered why Pauline Kael and Manny Farber were so tough on it. But I saw it in the '70s, when it was an artifact of another civilization and not an expression of contemporary weltanschauung.

"When Pauline begged to be disinvited to the "Come-Dressed-as-the-Sick-Soul-of-Europe Parties" and Manny described the star of La Notte as 'Monica Unvital,' they were fighting a stealth battle against the New York intellectuals who assumed that film art came from Europe. (Manny and Pauline both grew up in the Bay Area and were somewhat suspicious of East Coast intellectuals. They saw art in American movies. My hunch is part of their irritation at the more Symbolist of the French and Italian new wave was because the intellectual quarterlies didn't respect American movies. Interestingly, Susan Sontag — who was raised in North Hollywood! — was one of those NY intellectuals they railed against.)

"As to the basic question: When we go to films we project ourselves and values on the screen. The beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

"Malick represents pure visual storytelling, which I find exciting as long as there are no lava lamps or dinosaurs."

"Last Year really builds on its predecessor, Hiroshima Mon Amour, which was a collaboration between Resnais and Margeurite Duras, the screenwriter/novelist. It kind of pushes the techniques of Hiroshima to the next level, juxtaposing elliptical or poetic editing and voiceover to create something very close to an experimental or puzzle film. I admire it more than I like it, and I think some of the people who made fun of it at the time as a film that was flattering art house audiences for 'getting' it when there was nothing to get might have had a point. It's mainly a stylistic and atmospheric exercise, I think, ultimately far less effective than Hiroshima because it's not rooted in psychological and historical specifics. It's a bit more aware of itself as a tour-de-force, as an attempt to top what the director had done before. It verges on self-parody rather often, and Resnais is not known for his humor, so I suspect most of this is unintentional."

"It doesn't take much for people to disagree about a movie, and that's partly because there's always so much to like or dislike: the story and the dialogue, the tone of the cinematography, the settings and costumes, the actors and their performances, the director's point of view. The closeness or distance of what's onscreen from your sensibility, and then how you feel about that. And it's complicated — loving a movie and respecting it are two different things. I don't care for Citizen Kane and I love Myra Breckinridge. I can't defend this preference on any sort of critical grounds…I know intellectually that Kane has all the virtues of script, acting, art direction, photography, and theme ('meaning,' in other words) and that Myra is an incoherent mess. But we don't evaluate movies intellectually. More than any other art form, they're an experience, and no two people have the same experience, even of the same event."

"I was once in a play called Slow Love. It was written by an Australian man who had epilepsy. He envisioned his work to come in a series of staged images that would be framed by lights up — some kind of abstract action — blackout. This would repeat maybe a hundred times to make up the content of the play. Of the many referenced works in the play was Last Year at Marienbad, which was quoted throughout. I think in the play it was meant to mirror what the writer was feeling, about the echoing of brief but substantial, memorable images. I suppose that film, therefore, does much of what every other art form does — it can be both abstract and entertaining. I think ultimately there is some kind of deeper meaning people take from even the most abstract works. It probably isn't a shared experience, the way it would be with a more accessible, universal story. In the end, I think it comes down to you, on that

day, as to whether the film will piss you off or pull you in. I was far more moved and intrigued by what Von Trier did in Melancholia that what Malick did in Tree of Life, perhaps because Tree of Life felt like a singular experience of a certain kind of family — whereas Melancholia (Take Shelter, too) was closer to what I think life is really like in 2011.

day, as to whether the film will piss you off or pull you in. I was far more moved and intrigued by what Von Trier did in Melancholia that what Malick did in Tree of Life, perhaps because Tree of Life felt like a singular experience of a certain kind of family — whereas Melancholia (Take Shelter, too) was closer to what I think life is really like in 2011. But I guess I'd have to say that, ultimately, the magic resides within us — and depending on how much energy we have that particular day to struggle with a meaningless film. This year seemed to offer up many fairly abstract, challenging stories that sort of meant what you wanted them to mean. But too many of those and you tune them out, reaching instead for the ones that tell stories that aren't open to interpretation. Marienbad stands out because it was one of a kind. It's hard to find anything that is one of a kind now.

The great thing about it all, I guess, is that there is room for both — frustratingly opaque art and pleasingly transparent entertainment."

"All I can say is that I do think movies cast a kind of spell when they work for you. I've seen movies under different circumstances and have had totally different reactions, other times my attempt at rediscovering something I thought maybe I was unprepared for only leaves to the depressing realization I was 'right' the first time."

"At the risk of polarizing some people here, I'm one of those biased moviegoers who thinks movies always need to be entertaining and — for the most part — have a plot, in order for me to be invested. At times I'm willing to bend the rules, of course; whenever kids at my college campus tell me they can't finish 2001 because it has no story, I always try to tell them that the film is meant to be an experience, full of ideas, and that a plot doesn't emerge until two-thirds into the movie…but at least it's telling a story. On second

thought, I guess Killer of Sheep didn't really have a story at all, but you know what? Burnett still drew me into that world. I got a feel for that environment. So, I love that movie too.

thought, I guess Killer of Sheep didn't really have a story at all, but you know what? Burnett still drew me into that world. I got a feel for that environment. So, I love that movie too.Again, though, being — for the most part — a proponent of movies with stories, I do have a bit of problem with movies that are all about exercises in style. This is why I have a more difficult time appreciating Godard than some of my peers in the blogosphere, or why I can't watch Soderbergh's Ocean remakes. The actors are clearly having fun on the screen, but I'm not having any fun watching them.

Again, though, there's always that Killer of Sheep-style of filmmaking: slow, slow case studies of slow characters. Uncle Boonmee and Gus Van Sant's Last Days both come to mind, and I love those movies, too. But those are the films in which all entertainment value derives from exploring those slow, introverted characters through repeated viewings. I had an even easier time appreciating Melancholia and Tree of Life because they have more of a narrative to them, though they're clearly also exercises in style.

I guess what I'm trying to say is: if I were a director, I'd want to be a storyteller, first and foremost. Have a good style, sure, but good substance first. Some of you guys are bringing up Howard Hawks, whom I do like, but the fact that most of his movies *are* mostly just full of talky sequences of camaraderie and bonding without much plot to them is probably the reason why you don't hear me raving about his work as much as others. Maybe that's why I enjoy John Ford's movies a little more.

By now, it certainly will seem anticlimactic, but as I previewed, I also stumbled upon an essay Susan Sontag wrote. Titled "Thirty Years Later," the essay was published in the Summer 1996 edition of The Threepenny Review to mark the reissuing of Against Interpretation on its 30th anniversary. What Sontag had to say as she looked backward began promising enough.

"The great revelation for me had been the cinema: I felt particularly marked by the films of Godard and Bresson. I wrote more about cinema than about literature, not because I loved movies more than novels but because I loved more new movies than new novels. Of course, I took the supremacy of the greatest literature for granted. (And assumed my readers did, too.) But it was clear to me that the film-makers I admired were, quite simply, better and more original artists than nearly all of the most acclaimed novelists; that, indeed, no other art was being so widely practiced at such a high level. One of my happiest achievements in the years that I was doing the writing collected in Against Interpretation is that no day passed without my seeing at least one, sometimes two or three, movies. Most of them were 'old.' My gluttonous absorption in cinema history only reinforced my gratitude for certain new films which (along with my roll-call of favorites from the silent era and the 1930s) I saw again and again, so exalting did they seem to me in their freedom and inventiveness of narrative method, their sensuality and gravity and beauty."

Then the essay turns decidedly toward the pessimistic side, not that you could argue with her much even though that is now almost 16 years old. "The world in which these essays were written no longer exists," Sontag wrote. "Instead of the utopian moment, we live in a time which is experienced as the end — more exactly, just past the end — of every ideal. (And therefore of culture: there is no possibility of true culture without altruism.) An illusion of the end, perhaps — and not more illusory than the conviction of thirty years ago that we were on the threshold of a great positive transformation of culture and society. No, not an illusion, I think." If Sontag felt this way in 1996, imagine what she'd think of our world today where the GOP presidential candidates try to outcrazy each other, little of good, substantive policy can be created in D.C. since both parties in Congress would rather do nothing that let the opposing team take partial credit for a "win" and, though film lovers such as myself hate to admit it, while television played a primary role in the debasing of our culture and still does with the various Real Housewives and Jersey Shores, the best shows that TV produces regularly exceed in quality the best in movies whether the films come from Hollywood studios or are produced independently. What grabbed me the most in "Thirty Years Later" were when Sontag wrote these words:

"So I can’t help viewing the writing collected in Against Interpretation with a certain irony. Still, I urge the reader not to lose sight of — it may take some effort of imagination — the larger context of admirations in which these essays were written. To call for an “erotics of art” did not mean to disparage the role of the critical intellect. To laud work condescended to, then, as 'popular' culture did not mean to conspire in the repudiation of high culture and its burden of seriousness, of depth. I thought I’d seen through certain kinds of facile moralism, and was denouncing them in the name of a more alert, less complacent seriousness. What I didn’t understand (I was surely not the right person to understand this) is that seriousness itself was in the early stages of losing credibility in the culture at large, and that some of the more transgressive art I was enjoying would reinforce frivolous, merely consumerist transgressions. Thirty years later, the undermining of standards of seriousness is almost complete, with the ascendancy of a culture whose most intelligible, persuasive values are drawn from the entertainment industries. Now the very idea of the serious (and the honorable) seems quaint, 'unrealistic,' to most people; and when allowed, as an arbitrary decision of temperament, probably unhealthy, too."

Surely, she can't be serious. I think she was and her name was Susan, not Shirley. It was enough to break my momentary spell. While I certainly agree with much of what Sontag wrote, where would we be without a little levity? (Watching nothing but Terrence Malick films, he said, followed by a rim shot from the drummer.)

I wish that I had had more time to organize these posts more coherently and given the number of comments I've received on the first two parts, I doesn't seemed to have sparked the conversation I'd hoped for either. Oh, well. Do you all think there was a subliminal message in Airplane!?

Tweet

Labels: Books, Coens, Criticism, Dunst, Godard, Hawks, John Ford, Kael, Malick, Oliver Stone, Resnais, Sean Penn, Soderbergh, Spielberg, Van Sant, Von Sydow, von Trier

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, January 18, 2012

How do you solve a problem like J. Edgar?

By Edward Copeland

After watching J. Edgar, I prepared to write my usual review, assessing the film overall for its direction, writing, performances and other technical qualities, but something kept sticking in my mind, preventing me from focusing on those aspects. My brain kept drifting back to a different question, one that has puzzled me in many movies for a long time but that reared its ugly head — literally — once again as I watched J. Edgar. Why in the 21st century, with all of the advancements that have been made in visual effects, does old age makeup still turn up so often looking so laughably bad as it does? It does such a disservice to the performers trying to act beneath the horrible messes slapped upon their visages. How can you concentrate on the performances of Leonardo DiCaprio, Armie Hammer and Naomi Watts in their characters' later years when their faces have been marred by such silly appliances? It doesn't always hurt — Jennifer Connelly won an Oscar for A Beautiful Mind despite the awful makeup that covered her at the end of that movie (or, more recently, Kate Winslet's awful aging in The Reader). What's more mystifying is when you look back at a film such as Arthur Penn's Little Big Man in 1970 and how great the old-age makeup on Dustin Hoffman was in that film. Enough on that subject. With that off my chest, I believe I'm ready to discuss the rest of J. Edgar now, truly a mixed bag of a movie if ever there were one.

John Edgar Hoover served as the first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, an agency whose creation he spearheaded in 1935 after leading its predecessor, the Bureau of Investigation, since 1924. Between the two bureaus, Hoover held the top job for nearly 50 years and in eight presidential administrations from Coolidge to Nixon. Hoover truly defined what it meant to be a man of contradictions. He led the way in modernizing many crucial techniques in criminal investigations such as fingerprinting and forensics but also frequently stepped outside the law to amass information on perceived enemies, either to himself or the country. His private life contained its own secrets, namely his close, perhaps gay, relationship with top assistant Clyde Tolson. At least as the movie portrays it, Hoover's paranoia about being gay stemmed from his mother, who once told him, "I would rather have a dead son than a daffodil for a son."

To compress a life full full of such huge historical events alongside the inner life of a man would be a challenge for any screenwriter and any director. While Dustin Lance Black (Oscar-winning writer of Milk) and two-time Oscar-winning director Clint Eastwood give it the old college try in J. Edgar, the sheer weight of all those years and all that material crushes them, leaving the film somewhat rudderless despite good performances.

Black's screenplay structures Hoover's life around the premise of a 1960s era Hoover (well-played by Leonardo DiCaprio, even beneath the hideous makeup) dictating his version of the events of his life to the first of several young agents, embellishing as he did in real life how much credit he deserved for various FBI triumphs. He practically claims to have shot and killed John Dillinger outside the movie theater himself, though he omits how in a pique he punished the agent who actually ended the '30s era bank robber's crime spree. Hoover, so closed-up and concerned about how he was perceived, would be a difficult role for any actor to pull off, so I don't think everyone realizes what a great job DiCaprio accomplishes here outside of those few rare moments of faint tenderness he allows himself to share with Clyde Tolson (equally well-played by Armie Hammer, so good as the Winklevoss twins in David Fincher's brilliant The Social Network.)

Because so much happened in U.S. history between 1924 and 1972, it would be damn near impossible to hit on everything that Hoover touched so the film concentrates on Communist radicals in the U.S. following the Russian Revolution, the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby and the war on the criminals such as Dillinger in the 1930s. It also hits upon Hoover's efforts to form the FBI in the first place.

The uncertainty of his relationship with Tolson gives the film some heart. There's one scene where after a dinner together when the two men ride off together, Hoover nervously places his hand on Tolson's that's reminiscent of scenes in Jean-Jacques Annaud's The Lover and Martin Scorsese's The Age of Innocence.

Some of the more unsavory sides of Hoover's nature get short shrift such as his plans to sabotage Martin Luther King with stories of infidelity and Communist associates thinking it will get King to refuse his Nobel Peace Prize. He gets one scene with Robert Kennedy (Jeffrey Donovan) where he shows him evidence of sexual excess he has on his brother but nothing more comes of it until he hears of JFK's assassination, call his brother and tells him the president has been shot and hangs up.

Judi Dench and Naomi Watts turn in solid performances as the two important women in Hoover's life. Dench plays his mother whom Hoover lived with until her death and you see where most of his psychological blocks formed. Watts gives a subtle turn as Helen Gandy, Hoover's lifelong secretary who has as little interest in men or a family life as Hoover does in women. The film also shows her shredding Hoover's secret files upon his death while Nixon's men search frantically for them.