Thursday, October 10, 2013

Better Off Ted: Bye Bye 'Bad' Part III

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now. If you missed Part I, click here. If you missed Part II, click here.

— Saul Goodman to Mike Ehrmantraut ("Buyout," written by Gennifer Hutchison, directed by Colin Bucksey)

By Edward Copeland

Playing to the back of the room: I love doing it as a writer and appreciate it even more as an audience member. While I understand how its origin in comedy clubs gives it a derogatory meaning, I say phooey in general. Another example of playing to the broadest, widest audience possible. Why not reward those knowledgeable ones who pay close attention? Why cater to the Michele Bachmanns of the world who believe that ignorance is bliss? What they don’t catch can’t hurt them. I know I’ve fought with many an editor about references that they didn’t get or feared would fly over most readers’ heads (and I’ve known other writers who suffered the same problems, including one told by an editor decades younger that she needed to explain further whom she meant when she mentioned Tracy and Hepburn in a review. Being a free-lancer with a real full-time job, she quit on the spot). Breaking Bad certainly didn’t invent the concept, but damn the show did it well — sneaking some past me the first time or two, those clever bastards, not only within dialogue, but visually as well. In that spirit, I don’t plan to explain all the little gems I'll discuss. Consider them chocolate treats for those in the know. Sam, release the falcon!

In a separate discussion on Facebook, I agreed with a friend at taking offense when referring to Breaking Bad as a crime show. In fact, I responded:

“I think Breaking Bad is the greatest dramatic series TV has yet produced, but I agree. Calling it a ‘crime show’ is an example of trying to pin every show or movie into a particular genre hole when, especially in the case of Breaking Bad, it has so many more layers than merely crime. In fact, I don't like the fact that I just referred to it as a drama series because, as disturbing, tragic and horrifying as Breaking Bad could be, it also could be hysterically funny. That humor also came in shapes and sizes across the spectrum of humor. Vince Gilligan's creation amazes me in a new way every time I think about it. I wonder how long I'll still find myself discovering new nuances or aspects to it. I imagine it's going to be like Airplane! — where I still found myself discovering gags I hadn't caught years and countless viewings after my initial one as an 11-year-old in 1980. Truth be told, I can't guarantee I have caught all that ZAZ placed in Airplane! yet even now. Can it be a mere coincidence that both Breaking Bad and Airplane! featured Jonathan Banks? Surely I can't be serious, but if I am, tread lightly.”

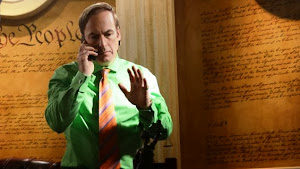

— Jonathan Banks as air traffic controller Gunderson in Airplane!

The second season episode “ABQ” (written by Vince Gilligan, directed by Adam Bernstein) introduced us to Banks as Mike and also featured John de Lancie as air traffic controller Donald Margulies, father of the doomed Jane. Listen to the DVD commentary about a previous time that Banks and De Lancie worked together. Speaking of air traffic controllers, if you don’t already know, look up how a real man named Walter White figured in an airline disaster. Remember Wayfarer 515! Saul never did, wearing that ribbon nearly constantly. Most realize the surreal pre-credit scenes that season foretold that ending cataclysm and where six of its second season episode titles, when placed together in the correct order, spell out the news of the disaster. Breaking Bad’s knack for its equivalent of DVD Easter eggs extended to episode titles, which most viewers never knew unless they looked them up. Speaking of Saul Goodman, he provided the voice for a multitude of Breaking Bad’s pop culture references from the moment the show introduced his character in season two’s “Better Call Saul” (written by Peter Gould, directed by Terry McDonough). Once he figures out (and it doesn’t take long) that Walt isn’t really Jesse’s uncle and pays him a visit in his high school classroom, the attorney and his client discuss a more specific role

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.

players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.As I admitted, some of the nice touches escaped my notice until pointed out to me later. Two of the most obvious examples occurred in the final eight episodes. One wasn’t so much a reference as a callback to the very first episode that you’d need a sharp eye to spot. It occurs in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson) and I’d probably never noticed if not for a synched-up commentary track that Johnson did for the episode on The Ones Who Knock weekly podcast on Breaking Bad. He pointed out that as Walt rolls his barrel of $11 million through the desert (itself drawing echoes to Erich von Stroheim’s silent classic Greed and its lead character McTeague — that one I had caught) he passes the pair of pants he lost in the very first episode when they flew through the air as he frantically drove the RV with the presumed dead Krazy-8 and Emilio unconscious in the back. Check the still below, enlarged enough so you don’t miss the long lost trousers.

The other came when psycho Todd decided to give his meth cook prisoner Jesse ice cream as a reward. I wasn’t listening closely enough when he named one of the flavor choices as Ben & Jerry’s Americone Dream, and even if I’d heard the flavor’s name, I would have missed the joke until Stephen Colbert, whose name serves as a possessive prefix for the treat’s flavor, did an entire routine on The Colbert Report about the use of the ice cream named for him giving Jesse the strength to make an escape attempt. One hidden treasure I did not know concerned the appearance of the great Robert Forster as the fabled vacuum salesman who helped give people new identities for a price. Until I read it in a column on the episode “Granite State” (written and directed by Gould), I had no idea that in real life Forster once actually worked as a vacuum salesman.

Seeing so many episodes multiple times, the callbacks to previous moments in the series always impressed me. I didn’t recall until AMC held its marathon prior to the finale and I caught the scene where Skyler caught Ted about him cooking his company’s books in season two’s “Mandala” (written by Mastras, directed by Adam Bernstein),

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.I wanted this tribute to be so much grander and better organized, but my physical condition thwarted my ambitions. I doubt seriously my hands shall allow me to complete a fourth installment. (If you did miss Part I or Part II, follow those links.) While I hate ending on a patter list akin to a certain Billy Joel song, (I let you off easy. I almost referenced Jonathan Larson — and I considered narrowing the circle tighter by namedropping Gerome Ragni

& James Rado.) I feel I must to sing my hosannas to the actors, writers, directors and other artists who collaborated to realize the greatest hour-long series in

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

In fact, the series failed me only twice. No. 1: How can you dump the idea that Gus Fring had a particularly mysterious identity in the episode “Hermanos” and never get back to it? No. 2: That great-looking barrel-shaped box set of the entire series only will be made on Blu-ray. As someone of limited means, it would need to be a Christmas gift anyway and for the same reason, I never made the move to Blu-ray and remain with DVD. Medical bills will do that to you and, even if tempting or plausible, it’s difficult to start a meth business to fund it while bedridden. Despite those two disappointments, it doesn’t change Breaking Bad’s place in my heart as the best TV achievement so far. How do I know this? Because I say so.

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Cranston, D. Zucker, De Palma, Deadwood, Hackman, Hawks, HBO, J. Zucker, Jim Abrahams, K. Hepburn, O'Toole, Oliver Stone, Tracy, Treme, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, October 03, 2013

Sirota already did it: Bye bye 'Bad' Part II

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now.

By Edward Copeland

When envisioning the epic farewell I felt I must write upon the conclusion of Breaking Bad, I didn't anticipate an important section of the tribute would begin with a South Park reference to The Simpsons. (If, by chance, you missed Part I, click here.)

Now, anyone with even a smidgeon of understanding of the basic tenets of comedy knows that if you need to explain a joke, you've failed somewhere in the telling. Despite this rule of humor, forgive me for explaining the title of the second part of my Breaking Bad tribute, but I can't assume that all Breaking Bad fans reading this also hold knowledge of specific South Park episodes. Way back in that animated series' sixth season in 2002, poor Butters' alter ego, Professor Chaos (six years before any of us knew Walter White and his inhabiting spirit Heisenberg), finds every scheme he devises greeted by some variation of the episode's title: "The Simpsons Already Did It." I just spent a long way to travel to the point of my headline, which refers to the great columnist David Sirota's article, posted by Salon on Sept. 28, the day before "Felina" aired, titled "Walter White's sickness mirrors America." (If you didn't understand before, I imagine you comprehend now how explaining a joke tends to kill its punchline.) In his piece, Sirota posits:

the specific pressures and ideologies that make America exceptional at the very moment

the country is itself breaking bad.

The most obvious way to see that is to look at how Walter White’s move into the drug trade

was first prompted, in part, by his family’s fear that he would die prematurely for lack

of adequate health care. It is the kind of fear most people in the industrialized world

have no personal connection to — but that many American television watchers no doubt do.

That’s because unlike other countries, Walter White’s country is exceptional for being a place

where 45,000 deaths a year are related to a lack of comprehensive health insurance coverage.

That’s about ten 9/11′s worth of death each year because of our exceptional position

as the only industrialized nation without a universal public health care system

(and, sadly, Obamacare will not fix that)."

Aside from the fact the Sirota misses the mark a bit concerning Walt’s original motives for entering the meth-making business and makes it sound as if his family encouraged the idea and raised money concerns before he even started to cook (more specifics on that later), Sirota’s piece covers ground that I always planned to discuss as well. Sirota might not be the first person to voice this hypothesis, but I’ve only seen and read his article (post finale, as I purposely tried to avoid other pieces to make mine my own as much as possible). I also saw the funny package envisioning how Walter's tale would play out if set in Canada. Health care costs in the U.S., significant in Breaking Bad, secured itself as a crucial aspect of my retrospective since the first half of season five given that I’ve

existed as a permanent patient for nearly the exact same time period as Breaking Bad’s television run. Unfortunately, my experiences give me much in the way of first-hand knowledge on the subject through which to view the series' take. While Sirota argues that Walt began his criminal career to pay for his exceedingly costly cancer treatments and White indeed used his ill-gotten gains toward those bills, he never expressed a desire to make a load of money to keep himself alive. Walter White already resigned himself to the idea of his impending death. The meth money’s only purpose originally, according to Walt, merely meant leaving behind a nest egg for Skyler, Walt Jr. and his as-of-then unborn child. He said as much in the great scene from the first season episode “Gray Matter” (written by Patty Lin, directed by Tricia Brock) where the entire family gathers at Skyler’s behest to stage a pseudo-intervention of the health care variety, passing around the “talking pillow” to take the floor and address Walt as to why he should accept the Schwartzes’ offer to pay for his treatments. The scene turns particularly grand

existed as a permanent patient for nearly the exact same time period as Breaking Bad’s television run. Unfortunately, my experiences give me much in the way of first-hand knowledge on the subject through which to view the series' take. While Sirota argues that Walt began his criminal career to pay for his exceedingly costly cancer treatments and White indeed used his ill-gotten gains toward those bills, he never expressed a desire to make a load of money to keep himself alive. Walter White already resigned himself to the idea of his impending death. The meth money’s only purpose originally, according to Walt, merely meant leaving behind a nest egg for Skyler, Walt Jr. and his as-of-then unborn child. He said as much in the great scene from the first season episode “Gray Matter” (written by Patty Lin, directed by Tricia Brock) where the entire family gathers at Skyler’s behest to stage a pseudo-intervention of the health care variety, passing around the “talking pillow” to take the floor and address Walt as to why he should accept the Schwartzes’ offer to pay for his treatments. The scene turns particularly grand when Marie surprises (and pisses off) her sister by agreeing with Walt about not wanting to suffer through the chemo treatments and succeeds at changing Hank’s mind as well. A wonderful example of how the show (as all the best dramas do) successfully mixed levity with tragedy. One of the funniest moments in the history of The Sopranos came in its fourth season episode “The Strong, Silent Type” (story by David Chase, written by Terence Winter, Robin Green & Mitchell Burgess, directed by Alan Taylor) when Tony’s crew attempts a drug intervention on Christopher with disastrous and hilarious results. The night that episode aired, the premiere of “The Grand Opening” episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm (directed by Robert B. Wiede) followed it, with Larry David’s own singular attempt at an emergency intervention for his new restaurant’s chef (Paul Sand) who had Tourette syndrome. My stomach hurt from laughing so hard that night. What makes interventions so easily comical? When Walt agrees to treatments and uses his meth money to pay (while lying to Skyler that he accepted Elliot and Gretchen’s offer to help), what motivates him isn’t (at least consciously) a sudden desire to fight the cancer but the need to live longer and build up a bigger bequest for his family. While the insanity of medical costs floats around the series at this time, this isn’t where Breaking Bad truly takes aim on our broken system.

when Marie surprises (and pisses off) her sister by agreeing with Walt about not wanting to suffer through the chemo treatments and succeeds at changing Hank’s mind as well. A wonderful example of how the show (as all the best dramas do) successfully mixed levity with tragedy. One of the funniest moments in the history of The Sopranos came in its fourth season episode “The Strong, Silent Type” (story by David Chase, written by Terence Winter, Robin Green & Mitchell Burgess, directed by Alan Taylor) when Tony’s crew attempts a drug intervention on Christopher with disastrous and hilarious results. The night that episode aired, the premiere of “The Grand Opening” episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm (directed by Robert B. Wiede) followed it, with Larry David’s own singular attempt at an emergency intervention for his new restaurant’s chef (Paul Sand) who had Tourette syndrome. My stomach hurt from laughing so hard that night. What makes interventions so easily comical? When Walt agrees to treatments and uses his meth money to pay (while lying to Skyler that he accepted Elliot and Gretchen’s offer to help), what motivates him isn’t (at least consciously) a sudden desire to fight the cancer but the need to live longer and build up a bigger bequest for his family. While the insanity of medical costs floats around the series at this time, this isn’t where Breaking Bad truly takes aim on our broken system.As I wrote in my sole previous piece on Breaking Bad prior to this post-series wake/celebration, I came to the series late and only began watching it live in the third season that premiered March 21, 2010, and ended with Gale Boetticher opening his apartment door to an emotionally fragile and gun-wielding Jesse Pinkman on June 13. As

proved to be the case with each season of Breaking Bad, each new season topped the one that preceded it, even though no bad seasons or mediocre episodes exist. Breaking Bad tackled the high price of medicine, if not as an overriding concern, or motivation, in the first two seasons not only through the obvious costs of Walt’s cancer treatments, but also when Heisenberg first appeared and marched into the headquarters of the psychotic Tuco, demanding not only advance payment for his “product” but reparations as well to cover Jesse’s hospital bills from Tuco beating poor Pinkman within an inch of his life. For myself (and, admittedly, this came from overidentifying with someone losing the use of his legs, albeit not because of an assassination attempt by vengeance-seeking lookalike cousins), the series’ most direct discussion of the flaws in this country’s health care system came in the hospital scenes dealing with the aftermath of Hank’s shooting. In the early days, when Walt coughed up cashier’s checks for cancer bills

proved to be the case with each season of Breaking Bad, each new season topped the one that preceded it, even though no bad seasons or mediocre episodes exist. Breaking Bad tackled the high price of medicine, if not as an overriding concern, or motivation, in the first two seasons not only through the obvious costs of Walt’s cancer treatments, but also when Heisenberg first appeared and marched into the headquarters of the psychotic Tuco, demanding not only advance payment for his “product” but reparations as well to cover Jesse’s hospital bills from Tuco beating poor Pinkman within an inch of his life. For myself (and, admittedly, this came from overidentifying with someone losing the use of his legs, albeit not because of an assassination attempt by vengeance-seeking lookalike cousins), the series’ most direct discussion of the flaws in this country’s health care system came in the hospital scenes dealing with the aftermath of Hank’s shooting. In the early days, when Walt coughed up cashier’s checks for cancer bills since his health insurance coverage through his school district didn’t approach the needed benefits to pay for his treatments, viewers saw some of the costs, but we never received a final bill, especially after Walt went the surgical option, handled by Dr. Victor Bravenec, played by Sam McMurray. McMurray also played Uncle Junior’s arrogant oncologist, Dr. John Kennedy, in the classic Sopranos episode “Second Opinion” (written by Lawrence Konner, directed by Tim Van Patten), where Tony and Furio used some not-so-friendly persuasion on the golf course to convince Kennedy to treat Junior right. (When McMurray showed up on Breaking Bad as an oncologist, part of me wondered if his character wasn’t Kennedy, having relocated under a new name to Albuquerque out of fear of mob repercussions, unaware that his new patient might be deadlier than anyone in that northern New Jersey crew could be.) Back to Hank. We know the extra needed to get Schrader on his feet again. That even came up again in the final eight episodes: $177,000. Pretty pathetic that a loyal public servant such as Hank Schrader, whose job constantly required him to put his life on the line, didn’t get the kind of catastrophic coverage he required when he needed it. For all the times, she could annoy him and cause him grief with that little kleptomania problem, Hank Schrader could not have chosen a better mate than the former Marie Lambert. Marie might only work as an X-ray technician, but she spoke the truth as she yelled at the various people in the hospital that Hank had to begin work on regaining the use of his legs immediately because a delay of even two weeks would be too late. I actually cried when I watched the episode where Betsy Brandt spoke those lines as Marie because I’d yelled those words myself at people in the hospital when I went in there in May 2008. (For those unfamiliar with my personal plight, click here.) I already had limited use of my legs because of my primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Two weeks stuck in bed can do irreparable damage to a marathon runner. Quite some time ago, I was able to make contact with Ms. Brandt and shared my tale with her about how I wish that I’d had someone like Marie back then to fight on my side. She graciously wrote back, “Edward, Marie would have definitely been your champion…and we all need a champion at times.”

since his health insurance coverage through his school district didn’t approach the needed benefits to pay for his treatments, viewers saw some of the costs, but we never received a final bill, especially after Walt went the surgical option, handled by Dr. Victor Bravenec, played by Sam McMurray. McMurray also played Uncle Junior’s arrogant oncologist, Dr. John Kennedy, in the classic Sopranos episode “Second Opinion” (written by Lawrence Konner, directed by Tim Van Patten), where Tony and Furio used some not-so-friendly persuasion on the golf course to convince Kennedy to treat Junior right. (When McMurray showed up on Breaking Bad as an oncologist, part of me wondered if his character wasn’t Kennedy, having relocated under a new name to Albuquerque out of fear of mob repercussions, unaware that his new patient might be deadlier than anyone in that northern New Jersey crew could be.) Back to Hank. We know the extra needed to get Schrader on his feet again. That even came up again in the final eight episodes: $177,000. Pretty pathetic that a loyal public servant such as Hank Schrader, whose job constantly required him to put his life on the line, didn’t get the kind of catastrophic coverage he required when he needed it. For all the times, she could annoy him and cause him grief with that little kleptomania problem, Hank Schrader could not have chosen a better mate than the former Marie Lambert. Marie might only work as an X-ray technician, but she spoke the truth as she yelled at the various people in the hospital that Hank had to begin work on regaining the use of his legs immediately because a delay of even two weeks would be too late. I actually cried when I watched the episode where Betsy Brandt spoke those lines as Marie because I’d yelled those words myself at people in the hospital when I went in there in May 2008. (For those unfamiliar with my personal plight, click here.) I already had limited use of my legs because of my primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Two weeks stuck in bed can do irreparable damage to a marathon runner. Quite some time ago, I was able to make contact with Ms. Brandt and shared my tale with her about how I wish that I’d had someone like Marie back then to fight on my side. She graciously wrote back, “Edward, Marie would have definitely been your champion…and we all need a champion at times.”So much more to say. Who knows when I will get them posted? As I posted on Facebook, odds are this is psychosomatic or coincidental, but my M.S. symptoms have spread to parts of my body they had avoided before since Breaking Bad ended. Perhaps sheer force of will held them at bay until I saw the series until its conclusion. I haven't written all I planned to yet, but this makes for a good stopping point for Part II.

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Curb Your Enthusiasm, David Chase, Larry David, South Park, The Simpsons, The Sopranos, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, September 30, 2013

What a ride: Bye bye 'Bad' Part I

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now.

By Edward Copeland

Kept you waiting there too long my love.

All that time without a word

Didn't know you'd think that I'd forget

Or I'd regret the special love I have for you —

My Baby Blue.

Perfection. I don’t intend (and never planned) to spend much of this farewell to Breaking Bad discussing its finale, but it happens too seldom that a movie or a final episode wraps with the absolute spot-on song. The Crying Game did it with Lyle Lovett singing “Stand By Your Man.” The Sopranos often accomplished it with specific episodes such as using The Eurythmics’ “I Saved the World Today” at the end of the second season’s “Knight in White Satin Armor” episode. Breaking Bad killed last night with some Badfinger — and how often do you read words along those lines?

We first met Walter Hartwell White, his family and associates (or, if you prefer, eventual victims/collateral damage) on Jan. 20, 2008. Viewers anyway. As for the time period of the show, the first scene or that first episode, I’d be a fool to venture a definitive guess. I start this piece with that date because it places the series damn close to the beginning of the 2008 calendar year. In the years since Vince Gilligan’s brilliant creation graced our TV screens, five full years of movies opened in the U.S. and ⅔ of a sixth. In that time, some great films crossed my path. Many I anticipate being favorites for the rest of my days: WALL-E, (500) Days of Summer and The Social Network, to name but three. As much as I love those movies and many others released in that time, I say without hyperbole that none equaled the quality or satisfied me as much as the five seasons of Breaking Bad.

For me to make such a declaration might come off as one more person jumping on the "what an amazing time we live in for quality TV" bandwagon. As someone who from a young age loved movies to such a degree that I sometimes attended new ones just to see something, admitting this amazes even me. On some level, early on in this sea change, it felt as if I not only had cheated on my wife but become a serial adulterer as well. In my childhood days of movie love, I also watched way too much TV, but I admittedly held the medium in disdain as a whole, an attitude that, despite the shows I loved and recognized as great, didn’t change until Hill Street Blues arrived. However, I can’t deny the transfer of my affection as to which medium satisfies, engages and gives me that natural high once exclusive to the best of cinema or, in those all-too-brief years I could attend, superb New York theater productions, most consistently now. It’s not that top-notch movies no longer get made, but experiencing sublime new films occurs far less frequently than in years past. (Perhaps a mere coincidence, but the most recent year that I’d cite as overflowing with works reaching higher heights happens to be 1999 — the same year The Sopranos premiered, marking the unofficial start of this era.) Granted, television and other outlets such as Netflix expanded the number of places available for programming exponentially, television as a whole still produces plenty of time-wasting crap. However, on a percentage basis, the total of fictional TV series produced that rank among the greatest in TV history probably hits a higher number than great films reach out of each year's crop of new movies.

Close readers of my movie posts know that when I compile lists of all-time favorite films, as I did last year, I require that a movie be at least 10 years old before it reaches eligibility for inclusion. With that requirement for film, it probably appears inconsistent on my part to declare Breaking Bad the greatest drama to air on television when it just concluded last night. However, I don’t feel like a hypocrite making this proclamation. When I saw any of the 62 episodes of Breaking Bad for the first time, never once did I feel afterward as if it had just been an “OK” episode. Obviously, some soared higher than others, but none ranked as so-so. I can’t say that about any other series. As much as I love The Sopranos, David Chase’s baby churned out some clunkers. The Wire almost matched Breaking Bad's achievement, but HBO prevented this by giving it a truncated fifth season that forced David Simon and gang to rush the ending in a way that made the final year unsatisfying following its brilliant fourth. Deadwood gets an incomplete, once again thanks to HBO, for not allowing David Milch to complete his five season vision. I recently re-read the one time I wrote about Breaking Bad, sometime in the middle of its third season, and though I didn't hail it to the extent I do now, the impending signs show in my protective nature toward the series since this came

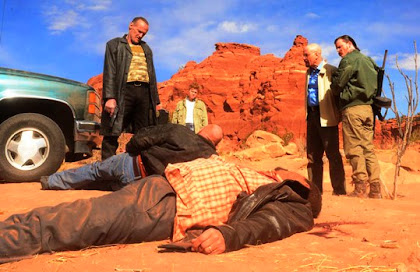

when it had a smaller, loyal cadre of fans such as myself who almost wanted to keep it our little secret. As the series moved forward, what amazed me — something that amazes me anytime it happens — was Breaking Bad’s ability to get better and better from season to season. That rarely occurs on any show, no matter how good. Programs might achieve a level of quality and maintain it, but rarely do any continue to top themselves. The Wire did that for its first four seasons but, as I wrote above, that stopped when HBO shorted them by three episodes in its final season. Breaking Bad not only grew better, it continued to experiment with its storytelling techniques right up to its final episodes. In this last batch of eight alone, we had “Rabid Dog” (written and directed by Sam Catlin) that begins with Walt, gun in hand, searching his gasoline-soaked house for an angry Jesse, whose car remains in the driveway while he can't be found. Then, well into the episode, we pick up where the previous episode ended with Jesse dousing the White residence with the flammable liquid and learn that Hank had tailed him and stopped Pinkman in the act and convinced the angry young man that the enemy of his enemy might be his friend. Then, in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson), the amazing first scene (following the pre-title card teaser scene) at To’hajiilee following the lopsided shootout between Uncle Jack, Todd and their Neo-Nazi gang versus Hank and Gomez, lasts an amazing 13½ riveting minutes. The credits don’t run until after the second commercial break, more than 20 minutes into the episode. Throughout the series, despite being on a commercial network, Breaking Bad never shied away from long scenes (and kudos to AMC for allowing them to do so) such as Skyler and Walt’s rehearsal in season 4’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) for telling Hank and Marie about Walt’s “gambling problem” and how that gave them the money to buy the car wash. The dramas on pay cable that lack commercials seldom provide scenes of that notable length. Fear of the short attention span. With as many channels as exist, I say fuck those fidgety fools. Cater to those who appreciate these scenes when done as well as Breaking Bad did them. That writing surpassed most everything else on TV most of the time and as usual at the Emmys, where I consider it a fluke if someone or something deserving wins, Breaking Bad received no nominations for writing until the two it earned this year (and lost). On Talking Bad following the finale, Anna Gunn compared each new script’s arrival to Christmas morning — and she also worked on Deadwood with a master wordsmith like David Milch.

when it had a smaller, loyal cadre of fans such as myself who almost wanted to keep it our little secret. As the series moved forward, what amazed me — something that amazes me anytime it happens — was Breaking Bad’s ability to get better and better from season to season. That rarely occurs on any show, no matter how good. Programs might achieve a level of quality and maintain it, but rarely do any continue to top themselves. The Wire did that for its first four seasons but, as I wrote above, that stopped when HBO shorted them by three episodes in its final season. Breaking Bad not only grew better, it continued to experiment with its storytelling techniques right up to its final episodes. In this last batch of eight alone, we had “Rabid Dog” (written and directed by Sam Catlin) that begins with Walt, gun in hand, searching his gasoline-soaked house for an angry Jesse, whose car remains in the driveway while he can't be found. Then, well into the episode, we pick up where the previous episode ended with Jesse dousing the White residence with the flammable liquid and learn that Hank had tailed him and stopped Pinkman in the act and convinced the angry young man that the enemy of his enemy might be his friend. Then, in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson), the amazing first scene (following the pre-title card teaser scene) at To’hajiilee following the lopsided shootout between Uncle Jack, Todd and their Neo-Nazi gang versus Hank and Gomez, lasts an amazing 13½ riveting minutes. The credits don’t run until after the second commercial break, more than 20 minutes into the episode. Throughout the series, despite being on a commercial network, Breaking Bad never shied away from long scenes (and kudos to AMC for allowing them to do so) such as Skyler and Walt’s rehearsal in season 4’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) for telling Hank and Marie about Walt’s “gambling problem” and how that gave them the money to buy the car wash. The dramas on pay cable that lack commercials seldom provide scenes of that notable length. Fear of the short attention span. With as many channels as exist, I say fuck those fidgety fools. Cater to those who appreciate these scenes when done as well as Breaking Bad did them. That writing surpassed most everything else on TV most of the time and as usual at the Emmys, where I consider it a fluke if someone or something deserving wins, Breaking Bad received no nominations for writing until the two it earned this year (and lost). On Talking Bad following the finale, Anna Gunn compared each new script’s arrival to Christmas morning — and she also worked on Deadwood with a master wordsmith like David Milch. Looking again at the initial moments of Breaking Bad, now viewed with the knowledge of everything to come, it establishes much about Walter White even though it occurred before Heisenberg made any official appearance. Watch this clip of our introduction to both Walt and Breaking Bad and see what I mean.

From the beginning, all the elements of Walt’s delusions had planted their roots in his head: the denial of criminality, his conviction that his family justified all his actions (which, compared to what events transpire later, seem rather minor moral transgressions now). One thing I wondered: Did Hank hang on to that gas mask somewhere in DEA evidence? It had Walt's fingerprints on it since he flung it away bare-handed. If Jesse told Schrader where they began cooking, hard evidence for a case existed and things might have turned out differently. Oh, well. No use crying over spilled brother-in-laws at this point. Dipping in and out of the AMC marathon preceding the finale and watching and re-watching episodes over the years (because, among the other outstanding attributes of Breaking Bad, the show belongs on the list of the most compulsively re-watchable television series in history), I always look for the exact moment when Heisenberg truly dominated Walter White’s personality because while I’m not in any way excusing Walt’s actions the way the deranged Team Walt types do, obviously this man suffers from a split personality disorder. You spot it in the season 2 episode where they hold the celebration party over Walt's cancer news and he keeps pouring tequila into Walt Jr.'s cup until Hank tries to put a stop to it, prompting a confrontation that mirrors in many ways Hank and Walt's after Hank deduced his alter ego. It also contains dialogue where Walt apologizes in the morning, saying, "I don't know who that was yesterday. It wasn't me." What caused that split, we don’t really know. We know that Walt’s dad died of Huntington’s disease when White was young and Skyler alluded to the way “he was raised” when he resisted accepting the Schwartzes’ help paying for his cancer treatments in the early days and he has no apparent relationship with his mother. Frankly, I praise creator Vince Gilligan for not taking that easy way out and trying to explain the cause of Walter White’s madness. I find it more interesting when creators don’t try to explain what made their monsters. I didn’t need to know that young Hannibal Lecter saw his parents killed by particularly ghoulish Nazis in World War II who ate his parents. Hannibal's character remains more interesting without some traumatic back story to explain what turned him into the serial killer he became. Since I brought up

those Team Walt members, while I can't conceive how anyone still defends him, I understand how people sympathized with Walter White at first and it took different actions and moments in the series for individual viewers to accept the fact that no classification fit Walter White other than that of a monster. In the beginning, the series made it easy to feel for Walt and cheer him on. When he took action on the asshole teens mocking Walt Jr. for his cerebral palsy, who didn't think those punks deserved it? While an excessive act, when he fried the car battery of the asshole who stole his parking space, who hasn't fantasized about getting even on someone like that? Even when Walt's acts got more serious, you sided with him, such as when he bawled, sobbing "I'm sorry" repeatedly as he killed Krazy-8. Even the moment most cite as the breaking point as Walt watches Jane die plays as open to interpretation. He looks like a deer in the headlights, uncertain of what to do as much as someone who sees the advantage of letting this woman in the process of extorting him expire. The credit for that ambiguity belongs to the brilliance of Bryan Cranston's performance. However, once you get to that final season 4 reveal of the Lily of the Valley plant, I don't see how anyone defended Walt after that, if they hadn't stopped already. As Hank said at the end, Walt was the smartest guy he ever met, so why couldn't he devise a way to either save himself or kill Gus that didn't involve poisoning a child?

those Team Walt members, while I can't conceive how anyone still defends him, I understand how people sympathized with Walter White at first and it took different actions and moments in the series for individual viewers to accept the fact that no classification fit Walter White other than that of a monster. In the beginning, the series made it easy to feel for Walt and cheer him on. When he took action on the asshole teens mocking Walt Jr. for his cerebral palsy, who didn't think those punks deserved it? While an excessive act, when he fried the car battery of the asshole who stole his parking space, who hasn't fantasized about getting even on someone like that? Even when Walt's acts got more serious, you sided with him, such as when he bawled, sobbing "I'm sorry" repeatedly as he killed Krazy-8. Even the moment most cite as the breaking point as Walt watches Jane die plays as open to interpretation. He looks like a deer in the headlights, uncertain of what to do as much as someone who sees the advantage of letting this woman in the process of extorting him expire. The credit for that ambiguity belongs to the brilliance of Bryan Cranston's performance. However, once you get to that final season 4 reveal of the Lily of the Valley plant, I don't see how anyone defended Walt after that, if they hadn't stopped already. As Hank said at the end, Walt was the smartest guy he ever met, so why couldn't he devise a way to either save himself or kill Gus that didn't involve poisoning a child?With all that said, Walt, while not redeemed, did rightfully regain some sympathy in the home stretch — surrendering his precious ill-gotten gains in a fruitless plea for Hank’s life, trying to clear Skyler of culpability, ultimately freeing Jesse and, most importantly, admitting that all his evil deeds had nothing to do with providing for his family but were because he enjoyed them, they made him feel alive. Heisenberg probably left that drink unfinished at the New Hampshire bar, but I think the old Walter White returned. The people he harmed deserved it and the scare he put in Elliot and Gretchen Schwartz merely a fake-out to ensure they did what he wanted with the money. He didn’t break good at the end, but he tied up loose ends and then allowed himself to die side by side with his true love — the blue meth he created that rocked the drug-addicted world.

Alas, my physical limitations prevent me from giving the series the farewell I envisioned in a single tribute, so I must break this into parts as much remains to be discussed — I’ve yet to touch upon the magnificent array of acting talent, brilliant direction and tons of other issues so, while Breaking Bad’s story has ended, this one has not. So, regretfully, as I collapse, I must say…

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Cranston, David Chase, David Simon, Deadwood, Hannibal Lecter, HBO, Milch, Netflix, The Sopranos, The Wire, Theater, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, June 03, 2012

Paging Dr. House!

UPDATE: Final installment that completes list of 10 favorite episodes has been posted. You can skip directly to the fourth part by clicking here.

By Edward Copeland

On May 21, the television series House (I refuse to use that blasted M.D. in the title — no one does anyway) ended its eight season run. I planned to do a suitable tribute along with a list of my 10 favorite episodes later in the week. I felt no need to rush my piece — no time-sensitive projects loomed on my calendar and I managed to get a review of the finale posted the day after — so I thought I'd earned the right to let it ferment before allowing the world a chance to read it. Unfortunately, as I prepared the piece with care, my body began to weaken from some sort of bug so I got less done and it did begin to bump up against other projects so I finally had to bite the bullet and get this out there — then a series of violent thunderstorms combined with my laptop suddenly acting flaky bumped against my longest, most exhausting doctor's appointment just as I neared completion. I kept feeling puny — sometimes sleeping most of a day away. Then I got pissed and decided I would finish this, starting by sending the two completed portions out ASAP. (The 10 favorites will begin in the second part). I owe it to the show, the character, Hugh Laurie and most of the cast. I wish this had turned out better, but the fates seemed aligned against it, but here it is, warts and all. I also wanted the thought that occurred to me while contemplating this tribute finally out in the universe (if anyone else posited this theory before, I apologize because it never crossed my path). I already miss Laurie and the creation he embodied for eight seasons, a character with a secure spot on the list of all-time great television characters. That ill-mannered, tell-it-like-it-is, Vicodin-addicted, crippled, socially maladjusted genius never failed to entertain me (even though the series that contained him hadn't accomplished that consistently for several seasons). As noted repeatedly and endlessly, House basically reimagined Sherlock Holmes in a medical setting, with Robert Sean Leonard's Wilson serving as his Dr. Watson. However, the more I reflected on Gregory House, the more I noticed that it's a different detective with whom he shares more striking similarities.

The detective that I saw signs of in Gregory House and vice versa (though not a 100 percent match — except for a brief separation, Pembleton had a happy married life) received his induction in that great TV character hall of fame back in the 1990s. When this parallel punched me in the face as I began this tribute, I believe the behind-the-scenes team at House must have had this thought in mind when they cast Andre Braugher as House's psychiatrist, Dr. Darryl Nolan, during his stay at Mayfield Mental Hospital since Braugher brought Baltimore homicide detective Frank Pembleton to life on Homicide: Life on the Street. I also think we can rule out coincidence as a factor because of Paul Attanasio, Attanasio served as an executive producer for all eight seasons of House. He also created Homicide: Life on the Street and wrote its first episode, “Gone for Goode,” basing Frank and the other characters on real Baltimore homicide detectives depicted in former Baltimore Sun crime reporter David Simon's nonfiction book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, before Simon turned to television himself. If you don't believe me, let's compare the detective and the doctor in more detail.

FELTON: Amazing. Life is amazing.

PEMBLETON: Really?

FELTON: This must be a mistake. Am I actually going on a routine call with Frank Pembleton?

PEMBLETON: You're right. It's a mistake.

FELTON: Frank Pembleton only works the big investigations. This is just some dead guy.

PEMBLETON See what happens when I come into the office?

FELTON: Imagine — handling a routine call with Detective Frank Pembleton.

PEMBLETON: I'm slumming.

HOUSE: "See that, they all assume I'm a patient because of the cane."

WILSON: "Then why don't you put on a white coat like the rest of us?"

HOUSE: "Then they'll think I'm a doctor."

House might enjoy staying away from his patients as long as he can, but he isn't bashful about boasting about his successes with a blurted, "I rock!" or some equivalent just as Pembleton similarly brags to rookie Detective Tim Bayliss (Kyle Secor), now his unwelcome partner,

about what he will see in the infamous Box, where they interrogate murder suspects. "What you will be privileged to witness will not be an interrogation, but an act of salesmanship — as silver-tongued and thieving as ever moved used cars, Florida swampland, or Bibles. But what I am selling is a long prison term, to a client who has no genuine use for the product," Pembleton proclaims. Needless to say, both men lived to solve puzzles, the major difference comes from what motivates the detective and the doctor. House figures out the puzzle for the puzzle's sake,

about what he will see in the infamous Box, where they interrogate murder suspects. "What you will be privileged to witness will not be an interrogation, but an act of salesmanship — as silver-tongued and thieving as ever moved used cars, Florida swampland, or Bibles. But what I am selling is a long prison term, to a client who has no genuine use for the product," Pembleton proclaims. Needless to say, both men lived to solve puzzles, the major difference comes from what motivates the detective and the doctor. House figures out the puzzle for the puzzle's sake, but Frank puts the mystery to an end because he feels as if the responsibility to speak for those murder victims who can't rests with him. The reason Pembleton believes this is his duty brings him closer to House in yet another way. While House makes no secret of his atheism, Pembleton hasn't gone that far, but he doesn't hide his anger at God, who the Jesuit-educated detective thinks no longer watches or cares about his creations. Pembleton's loss of faith runs so deep that he refuses to step inside a church. While Pembleton's character lacked an infirmity akin to House's leg when Homicide began, but he suffered a stroke at the end of the fourth season that he necessitated a recovery. (Well acted, as always, by Braugher, but why give your best character whose greatest attribute comes from his use of language impairment of that gift?) Finally, though Pembleton wasn't in charge of the one in the squad room, white boards played key roles in both shows.

but Frank puts the mystery to an end because he feels as if the responsibility to speak for those murder victims who can't rests with him. The reason Pembleton believes this is his duty brings him closer to House in yet another way. While House makes no secret of his atheism, Pembleton hasn't gone that far, but he doesn't hide his anger at God, who the Jesuit-educated detective thinks no longer watches or cares about his creations. Pembleton's loss of faith runs so deep that he refuses to step inside a church. While Pembleton's character lacked an infirmity akin to House's leg when Homicide began, but he suffered a stroke at the end of the fourth season that he necessitated a recovery. (Well acted, as always, by Braugher, but why give your best character whose greatest attribute comes from his use of language impairment of that gift?) Finally, though Pembleton wasn't in charge of the one in the squad room, white boards played key roles in both shows.

The two shows almost followed similar paths in other ways as well. Both produced three nearly flawless seasons and fourth seasons that continued to offer enough rewards to earn viewer fidelity worthwhile — then both series bore the signs that they'd overstayed their welcomes. The cases, be they murder or medical, ceased to hold our interest as they once did, and constant cast changes made each new season look as if the Princeton-Plainsboro Teaching Hospital (or the Baltimore homicide department) underwent extreme makeovers during the summer hiatus. (Each show had its annoying new additions too — Olivia Wilde's Thirteen on House; Jon Seda's Falsone on Homicide.) In the end, Wilde must have frustrated the show's producers as much as viewers,

being absent for most of the seventh season and only present for four or so episodes of the eighth so she wouldn't miss out on once-in-a-lifetime acting opportunities such as Tron: Legacy, Cowboys & Aliens and The Change-Up. Granted, Amber's death resulted in some compelling episodes such as "House's Head" and "Wilson's Heart" as well as when Anne Dudek returned to play Cutthroat Bitch as one of House's hallucinations. Still, wouldn't most fans willingly give those episodes up if it meant that House had fired Thirteen instead and Amber had joined the team? Awful decision on someone's part. I heard

being absent for most of the seventh season and only present for four or so episodes of the eighth so she wouldn't miss out on once-in-a-lifetime acting opportunities such as Tron: Legacy, Cowboys & Aliens and The Change-Up. Granted, Amber's death resulted in some compelling episodes such as "House's Head" and "Wilson's Heart" as well as when Anne Dudek returned to play Cutthroat Bitch as one of House's hallucinations. Still, wouldn't most fans willingly give those episodes up if it meant that House had fired Thirteen instead and Amber had joined the team? Awful decision on someone's part. I heard some people complain about Peter Jacobson as Taub, but I always liked him and if Kal Penn (Kutner) decides he wants to take a huge pay cut to work for the White House and what he believes in most strongly, you hardly can fault him for that. Of the final two additions for season eight, Charlyne Yi's Dr. Chi Park proved to be interesting and funny from the moment she showed up. On the other hand, Odette Annable's character turned out to be such a nonentity that I had to look up her character's name. (Dr. Jessica Adams. Adams rings a bell, but does anyone remember her being called Jessica?) When she showed up with a new hairdo, I didn't immediately recognize that she'd been the doctor in the prison episode. However, though I liked Jacobson, Penn and Yi, no chemistry worked as well as the original cast (which, though I said it immediately afterward, made the ending all the more incomplete without the presence of Lisa Edelstein as Cuddy. I had nothing against Amber Tamblyn's brief role, but I didn't need closure with Masters. Cuddy's absence left a giant gaping hole in the finale.)

some people complain about Peter Jacobson as Taub, but I always liked him and if Kal Penn (Kutner) decides he wants to take a huge pay cut to work for the White House and what he believes in most strongly, you hardly can fault him for that. Of the final two additions for season eight, Charlyne Yi's Dr. Chi Park proved to be interesting and funny from the moment she showed up. On the other hand, Odette Annable's character turned out to be such a nonentity that I had to look up her character's name. (Dr. Jessica Adams. Adams rings a bell, but does anyone remember her being called Jessica?) When she showed up with a new hairdo, I didn't immediately recognize that she'd been the doctor in the prison episode. However, though I liked Jacobson, Penn and Yi, no chemistry worked as well as the original cast (which, though I said it immediately afterward, made the ending all the more incomplete without the presence of Lisa Edelstein as Cuddy. I had nothing against Amber Tamblyn's brief role, but I didn't need closure with Masters. Cuddy's absence left a giant gaping hole in the finale.)

That's why, when I think most fondly about my favorite episodes of House, that my memory inevitably returns to those first three initial seasons. While House, at its core, presents mysteries in the form of medical stories, even in the early seasons and the occasional interesting one that would pop up in later seasons, the puzzle might have been what kept House interested but for the viewer, the regular characters grabbed our attention and earned our loyalty to the show. Sure, Jesse Spencer and Jennifer Morrison continued to be on the show, but once Chase and Cameron left the team, it wasn't the same. This wasn't a series like Law & Order where the procedure proved pivotal to the show and it new cast members

could be plugged into roles without harming the series. What a testament not only to Hugh Laurie's brilliance and David Shore's for inventing the character of House in the first place, but the magical chemistry between Laurie, Robert Sean Leonard and Lisa Edelstein. Omar Epps, Morrison and Spencer fit well in those first three seasons as well, but when they came back to the team, some of that magic had vanished through no fault of the performers. How many times could Foreman reasonably quit or threaten to quit? The early elements that made Cameron fascinating — such as the desire to save everyone, especially House — seemed to vanish. What made for an initially interesting idea of Chase choosing to kill the genocidal dictator played by James Earl Jones

could be plugged into roles without harming the series. What a testament not only to Hugh Laurie's brilliance and David Shore's for inventing the character of House in the first place, but the magical chemistry between Laurie, Robert Sean Leonard and Lisa Edelstein. Omar Epps, Morrison and Spencer fit well in those first three seasons as well, but when they came back to the team, some of that magic had vanished through no fault of the performers. How many times could Foreman reasonably quit or threaten to quit? The early elements that made Cameron fascinating — such as the desire to save everyone, especially House — seemed to vanish. What made for an initially interesting idea of Chase choosing to kill the genocidal dictator played by James Earl Jones faded from everyone's memory too fast. That's why it was funny when Cameron returned in the Season 6 episode "Lockdown" to have Chase sign divorce papers and the hospital gets locked down because of a missing infant, trapping the soon-to-be ex-spouses together. "You had a conversation with House, and came back, informed me I had been forever poisoned by him, and started packing," Chase told her, explaining his version of their breakup. "Interesting how your story leaves out the part where you murdered another human being," Cameron replied. As far as I can remember, the incident went unmentioned for the remainder of the series. House's reaction actually could be taken as

faded from everyone's memory too fast. That's why it was funny when Cameron returned in the Season 6 episode "Lockdown" to have Chase sign divorce papers and the hospital gets locked down because of a missing infant, trapping the soon-to-be ex-spouses together. "You had a conversation with House, and came back, informed me I had been forever poisoned by him, and started packing," Chase told her, explaining his version of their breakup. "Interesting how your story leaves out the part where you murdered another human being," Cameron replied. As far as I can remember, the incident went unmentioned for the remainder of the series. House's reaction actually could be taken as out of character. When he figures out what happened and he and Chase talk, House says, "Better murder than a misdiagnosis." He advises Chase seek some help, but that's it. When Wilson planned to give a speech endorsing euthanasia, he intervened to save his friend's career. Back in the Season 2 episode "Clueless," he had the wife secretly poisoning her husband to death with gold arrested. He even called the police on one of the potential team candidates, Dr. Travis Brennan (Andy Comeau), after he told him to quit for purposely making a patient sicker with polio-like symptoms to try to fund research for his idea that high doses of Vitamin C would eradicate polio in the Third World. Granted, Chase killed a dictator who ordered genocide, but the Aussie doc, who once entered a seminary, eventually seemed free of any guilt over his act and Foreman bore no regrets about covering it up and even gave House's old job to Chase after House "died." Enough about the series' failings and parallels between House, Pembleton and their shows. This piece celebrates what House did well.

out of character. When he figures out what happened and he and Chase talk, House says, "Better murder than a misdiagnosis." He advises Chase seek some help, but that's it. When Wilson planned to give a speech endorsing euthanasia, he intervened to save his friend's career. Back in the Season 2 episode "Clueless," he had the wife secretly poisoning her husband to death with gold arrested. He even called the police on one of the potential team candidates, Dr. Travis Brennan (Andy Comeau), after he told him to quit for purposely making a patient sicker with polio-like symptoms to try to fund research for his idea that high doses of Vitamin C would eradicate polio in the Third World. Granted, Chase killed a dictator who ordered genocide, but the Aussie doc, who once entered a seminary, eventually seemed free of any guilt over his act and Foreman bore no regrets about covering it up and even gave House's old job to Chase after House "died." Enough about the series' failings and parallels between House, Pembleton and their shows. This piece celebrates what House did well.As I mentioned in my brief farewell to the show prior to the airing of the finale, I came to House late. The show hooked me in a setting where you'd think a series involving medical crises wouldn't prove amenable. Despite the odds, my habitual viewing of House started while imprisoned in two hospitals for three-and-a-half months in summer 2008. Often the only palatable programming on the room's TV turned out to be the endless marathons of House episodes that USA ran. Other than Scrubs, which I counted more as a comedy than a medical drama in

spite of serious moments, I hadn't watched any new medical shows since my beloved St. Elsewhere went off the air in 1988. (I admit to watching a single episode of ER, but that's simply because Quentin Tarantino directed it.) Honestly, that much of a line shouldn't be drawn between House and Scrubs because most everything I enjoy on television and in movies tends to contain some comedy or it loses me quickly (and, in its own way, Scrubs touched on reality more than House simply by addressing the issues of billing and insurance). That's why House proved to be such a comfort to me during my long hospital imprisonment. I identified with Gregory House as my personal horror story dragged on. I didn't have a pain pill addiction, but I confess to appropriating parts of his attitude when necessary to get what I wanted and to put idiots in their place. I also enjoyed watching those marathons in the first hospital, a Catholic "not-for-profit" hospital that charged ridiculous fees (A 72-year-old woman was shocked to find she'd been billed for labor and maternity costs) and had the worst TV channel selection that thankfully included USA but only included one cable news channel — Fox. Enjoying my role as asshole, I told them that could violate their tax-exempt status as a religious-affiliated institution by seemingly taking political sides and come January, a new sheriff would be in the White House and I'd feel forced to report them. They kept bribing me to try to shut me up. I got a DVD player. They hooked up a laptop. Thank you, House. Since his exit leaves the prime time landscape with one less openly atheist on TV and the remainder exist on shows I don't watch, a clip of some of his best lines concerning religion.

spite of serious moments, I hadn't watched any new medical shows since my beloved St. Elsewhere went off the air in 1988. (I admit to watching a single episode of ER, but that's simply because Quentin Tarantino directed it.) Honestly, that much of a line shouldn't be drawn between House and Scrubs because most everything I enjoy on television and in movies tends to contain some comedy or it loses me quickly (and, in its own way, Scrubs touched on reality more than House simply by addressing the issues of billing and insurance). That's why House proved to be such a comfort to me during my long hospital imprisonment. I identified with Gregory House as my personal horror story dragged on. I didn't have a pain pill addiction, but I confess to appropriating parts of his attitude when necessary to get what I wanted and to put idiots in their place. I also enjoyed watching those marathons in the first hospital, a Catholic "not-for-profit" hospital that charged ridiculous fees (A 72-year-old woman was shocked to find she'd been billed for labor and maternity costs) and had the worst TV channel selection that thankfully included USA but only included one cable news channel — Fox. Enjoying my role as asshole, I told them that could violate their tax-exempt status as a religious-affiliated institution by seemingly taking political sides and come January, a new sheriff would be in the White House and I'd feel forced to report them. They kept bribing me to try to shut me up. I got a DVD player. They hooked up a laptop. Thank you, House. Since his exit leaves the prime time landscape with one less openly atheist on TV and the remainder exist on shows I don't watch, a clip of some of his best lines concerning religion.It surprised me when I discovered House to see Bryan Singer's name in the credits as one of the executive producers. I knew him as a film director, most of whose films had left me cold until he made the first two X-Men movies. He also directed the House pilot episode,

"Everybody Lies," which, like most first episodes, gets bogged down in exposition and character introductions that prevents it from soaring. Singer also helmed the third episode, "Occam's Razor," and by then House's slide into a comfortable groove nearly was complete. Creator David Shore wrote "Occam's Razor" and, like nearly every episode of those early seasons, it came full of memorable dialogue. Two choice selections courtesy of House himself: "No, there is not a thin line between love and hate. There is, in fact, a Great Wall of China with armed sentries posted every twenty feet between love and hate."; "What would you prefer — a doctor who holds your hand while you die or one who ignores you while you get better? I suppose it would particularly suck to have a doctor who ignores you while you die." Then House responses to Wilson and Cameron.

"Everybody Lies," which, like most first episodes, gets bogged down in exposition and character introductions that prevents it from soaring. Singer also helmed the third episode, "Occam's Razor," and by then House's slide into a comfortable groove nearly was complete. Creator David Shore wrote "Occam's Razor" and, like nearly every episode of those early seasons, it came full of memorable dialogue. Two choice selections courtesy of House himself: "No, there is not a thin line between love and hate. There is, in fact, a Great Wall of China with armed sentries posted every twenty feet between love and hate."; "What would you prefer — a doctor who holds your hand while you die or one who ignores you while you get better? I suppose it would particularly suck to have a doctor who ignores you while you die." Then House responses to Wilson and Cameron.WILSON: That smugness of yours really is an attractive quality.

HOUSE: Thank you. It was either that or get my hair highlighted. Smugness is easier to maintain.

CAMERON: Men should grow up.

HOUSE: Yeah, and dogs should stop licking themselves. It's not going to happen.

CAMERON: Brandon's not ready for surgery.

HOUSE: OK, let's leave it a couple of weeks. He should be feeling better by then. Oh wait, which way does time go?

Those examples don't show what made the original cast such a miracle of casting chemistry — while Laurie certainly ranked at the top of the heap in the humor department among the performers, the others didn't merely act as his straight men. The entire ensemble

contributed to the comedic elements of the show as well. I think that lies behind why so many fans had such a negative reaction to Olivia Wilde's Thirteen — she just wasn't funny. Peter Jacobson's Taub and Kal Penn's Kutner were funny. Charlyne Yi's Park garnered laughs from the moment she joined the show. Even Odette Annable's (what was her name again?) Adams had her moments. Anne Dudek's Amber — I don't think I have to elaborate on her comic gifts whether her character had a pulse or afterward. Returning to Bryan Singer for a moment, at least his sense of humor extends to himself. The Usual Suspects, the film that first gained Singer attention as a director, was an incredibly overrated film as far as I was concerned. Apparently House agreed, at least in the fifth season episode "Joy to the World" written by Peter Blake, who co-wrote the series finale with Shore and Eli Attie. "Why don't you hang out in the video store and tell everyone Kevin Spacey's Keyser Söze? And by the way, that ending really made no sense at all." While the show's ability to make me laugh definitely drew me in during my time of need, by no means am I trying to slight the emotional impact that it routinely delivered as well. The series portrayed all its characters as fallible — cumulatively almost as much as House himself. Though House almost always solved the puzzle, that didn't mean he'd always save the patient.