Thursday, October 10, 2013

Better Off Ted: Bye Bye 'Bad' Part III

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now. If you missed Part I, click here. If you missed Part II, click here.

— Saul Goodman to Mike Ehrmantraut ("Buyout," written by Gennifer Hutchison, directed by Colin Bucksey)

By Edward Copeland

Playing to the back of the room: I love doing it as a writer and appreciate it even more as an audience member. While I understand how its origin in comedy clubs gives it a derogatory meaning, I say phooey in general. Another example of playing to the broadest, widest audience possible. Why not reward those knowledgeable ones who pay close attention? Why cater to the Michele Bachmanns of the world who believe that ignorance is bliss? What they don’t catch can’t hurt them. I know I’ve fought with many an editor about references that they didn’t get or feared would fly over most readers’ heads (and I’ve known other writers who suffered the same problems, including one told by an editor decades younger that she needed to explain further whom she meant when she mentioned Tracy and Hepburn in a review. Being a free-lancer with a real full-time job, she quit on the spot). Breaking Bad certainly didn’t invent the concept, but damn the show did it well — sneaking some past me the first time or two, those clever bastards, not only within dialogue, but visually as well. In that spirit, I don’t plan to explain all the little gems I'll discuss. Consider them chocolate treats for those in the know. Sam, release the falcon!

In a separate discussion on Facebook, I agreed with a friend at taking offense when referring to Breaking Bad as a crime show. In fact, I responded:

“I think Breaking Bad is the greatest dramatic series TV has yet produced, but I agree. Calling it a ‘crime show’ is an example of trying to pin every show or movie into a particular genre hole when, especially in the case of Breaking Bad, it has so many more layers than merely crime. In fact, I don't like the fact that I just referred to it as a drama series because, as disturbing, tragic and horrifying as Breaking Bad could be, it also could be hysterically funny. That humor also came in shapes and sizes across the spectrum of humor. Vince Gilligan's creation amazes me in a new way every time I think about it. I wonder how long I'll still find myself discovering new nuances or aspects to it. I imagine it's going to be like Airplane! — where I still found myself discovering gags I hadn't caught years and countless viewings after my initial one as an 11-year-old in 1980. Truth be told, I can't guarantee I have caught all that ZAZ placed in Airplane! yet even now. Can it be a mere coincidence that both Breaking Bad and Airplane! featured Jonathan Banks? Surely I can't be serious, but if I am, tread lightly.”

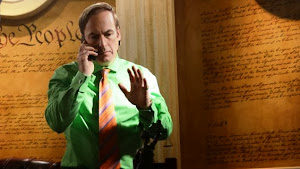

— Jonathan Banks as air traffic controller Gunderson in Airplane!

The second season episode “ABQ” (written by Vince Gilligan, directed by Adam Bernstein) introduced us to Banks as Mike and also featured John de Lancie as air traffic controller Donald Margulies, father of the doomed Jane. Listen to the DVD commentary about a previous time that Banks and De Lancie worked together. Speaking of air traffic controllers, if you don’t already know, look up how a real man named Walter White figured in an airline disaster. Remember Wayfarer 515! Saul never did, wearing that ribbon nearly constantly. Most realize the surreal pre-credit scenes that season foretold that ending cataclysm and where six of its second season episode titles, when placed together in the correct order, spell out the news of the disaster. Breaking Bad’s knack for its equivalent of DVD Easter eggs extended to episode titles, which most viewers never knew unless they looked them up. Speaking of Saul Goodman, he provided the voice for a multitude of Breaking Bad’s pop culture references from the moment the show introduced his character in season two’s “Better Call Saul” (written by Peter Gould, directed by Terry McDonough). Once he figures out (and it doesn’t take long) that Walt isn’t really Jesse’s uncle and pays him a visit in his high school classroom, the attorney and his client discuss a more specific role

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key

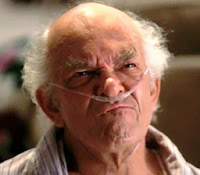

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.

players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.As I admitted, some of the nice touches escaped my notice until pointed out to me later. Two of the most obvious examples occurred in the final eight episodes. One wasn’t so much a reference as a callback to the very first episode that you’d need a sharp eye to spot. It occurs in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson) and I’d probably never noticed if not for a synched-up commentary track that Johnson did for the episode on The Ones Who Knock weekly podcast on Breaking Bad. He pointed out that as Walt rolls his barrel of $11 million through the desert (itself drawing echoes to Erich von Stroheim’s silent classic Greed and its lead character McTeague — that one I had caught) he passes the pair of pants he lost in the very first episode when they flew through the air as he frantically drove the RV with the presumed dead Krazy-8 and Emilio unconscious in the back. Check the still below, enlarged enough so you don’t miss the long lost trousers.

The other came when psycho Todd decided to give his meth cook prisoner Jesse ice cream as a reward. I wasn’t listening closely enough when he named one of the flavor choices as Ben & Jerry’s Americone Dream, and even if I’d heard the flavor’s name, I would have missed the joke until Stephen Colbert, whose name serves as a possessive prefix for the treat’s flavor, did an entire routine on The Colbert Report about the use of the ice cream named for him giving Jesse the strength to make an escape attempt. One hidden treasure I did not know concerned the appearance of the great Robert Forster as the fabled vacuum salesman who helped give people new identities for a price. Until I read it in a column on the episode “Granite State” (written and directed by Gould), I had no idea that in real life Forster once actually worked as a vacuum salesman.

Seeing so many episodes multiple times, the callbacks to previous moments in the series always impressed me. I didn’t recall until AMC held its marathon prior to the finale and I caught the scene where Skyler caught Ted about him cooking his company’s books in season two’s “Mandala” (written by Mastras, directed by Adam Bernstein),

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.I wanted this tribute to be so much grander and better organized, but my physical condition thwarted my ambitions. I doubt seriously my hands shall allow me to complete a fourth installment. (If you did miss Part I or Part II, follow those links.) While I hate ending on a patter list akin to a certain Billy Joel song, (I let you off easy. I almost referenced Jonathan Larson — and I considered narrowing the circle tighter by namedropping Gerome Ragni

& James Rado.) I feel I must to sing my hosannas to the actors, writers, directors and other artists who collaborated to realize the greatest hour-long series in

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

In fact, the series failed me only twice. No. 1: How can you dump the idea that Gus Fring had a particularly mysterious identity in the episode “Hermanos” and never get back to it? No. 2: That great-looking barrel-shaped box set of the entire series only will be made on Blu-ray. As someone of limited means, it would need to be a Christmas gift anyway and for the same reason, I never made the move to Blu-ray and remain with DVD. Medical bills will do that to you and, even if tempting or plausible, it’s difficult to start a meth business to fund it while bedridden. Despite those two disappointments, it doesn’t change Breaking Bad’s place in my heart as the best TV achievement so far. How do I know this? Because I say so.

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Cranston, D. Zucker, De Palma, Deadwood, Hackman, Hawks, HBO, J. Zucker, Jim Abrahams, K. Hepburn, O'Toole, Oliver Stone, Tracy, Treme, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, May 29, 2013

"A game-legged old man and a drunk. That's all you got?" "That's what I got."

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post is part of The Howard Hawks Blogathon occurring through May at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie Lover

By Edward Copeland

After the opening credits end, Howard Hawks begins Rio Bravo with a sequence somewhat unusual for a Western, or, for that matter, any film made in 1959. On the other hand, beneath the surface of Rio Bravo

you'll find many more layers than your typical Western. The scene almost plays as if it hails from the silent era as a haggard-looking Dean Martin tentatively enters a large establishment providing libations, meals and even barber services. Martin's character's face tells you that he wants to resist liquor's siren call, but he's weak and he struggles. A man at the bar (Claude Akins) spots him after purchasing his own drink. He flashes Martin a smile, gestures at his glass and asks with his eyes whether Martin desires one. Aside from the film score and the ambient noise of the establishment's environs, no dialogue emanates from any of the characters that Hawks' camera focuses upon in this scene that's practically choreographed in mime. Martin's character replies with an eager but wordless "yes" and Akins

you'll find many more layers than your typical Western. The scene almost plays as if it hails from the silent era as a haggard-looking Dean Martin tentatively enters a large establishment providing libations, meals and even barber services. Martin's character's face tells you that he wants to resist liquor's siren call, but he's weak and he struggles. A man at the bar (Claude Akins) spots him after purchasing his own drink. He flashes Martin a smile, gestures at his glass and asks with his eyes whether Martin desires one. Aside from the film score and the ambient noise of the establishment's environs, no dialogue emanates from any of the characters that Hawks' camera focuses upon in this scene that's practically choreographed in mime. Martin's character replies with an eager but wordless "yes" and Akins tosses a coin — into a spittoon — laughing with his buddies (the closest thing to a human voice heard in this building) as Martin's character's desperation outweighs his pride and he

tosses a coin — into a spittoon — laughing with his buddies (the closest thing to a human voice heard in this building) as Martin's character's desperation outweighs his pride and he gets down on his hands and knees, prepared to retrieve the money from the spit-out tobacco. Before he can, a foot kicks the spittoon out of the way and he looks up to see John Wayne towering above him in a great low-angle shot looking up at The Duke and giving him one of his many great screen entrances. His character's arrival also sets several of the story's strands into motion. You see, the man (Akins) taunting Dude (Martin) happens to be Joe Burdette, the blackest sheep of a powerful clan that gets away with practically anything it wants to do. Joe oversteps this time though as he continues to tease Dude after a brawl that includes the man who kicked over the spittoon, Sheriff John T. Chance (Wayne), Dude's boss when he's sober enough to carry out duties as deputy. Joe and his buddies keep harassing Dude when a sympathetic patron (Bing Russell) steps in, urging Joe to cut it out — still through gestures, not words. Joe Burdette doesn't take criticism well and shoots the unarmed man to death and exits the building to stagger to another saloon. Chance soon enters behind and speaks the film's first line, "Joe, you're under arrest."

gets down on his hands and knees, prepared to retrieve the money from the spit-out tobacco. Before he can, a foot kicks the spittoon out of the way and he looks up to see John Wayne towering above him in a great low-angle shot looking up at The Duke and giving him one of his many great screen entrances. His character's arrival also sets several of the story's strands into motion. You see, the man (Akins) taunting Dude (Martin) happens to be Joe Burdette, the blackest sheep of a powerful clan that gets away with practically anything it wants to do. Joe oversteps this time though as he continues to tease Dude after a brawl that includes the man who kicked over the spittoon, Sheriff John T. Chance (Wayne), Dude's boss when he's sober enough to carry out duties as deputy. Joe and his buddies keep harassing Dude when a sympathetic patron (Bing Russell) steps in, urging Joe to cut it out — still through gestures, not words. Joe Burdette doesn't take criticism well and shoots the unarmed man to death and exits the building to stagger to another saloon. Chance soon enters behind and speaks the film's first line, "Joe, you're under arrest."

Burdette and his buddies don't take the sheriff seriously and seem intent to mow the lawman down when a still-shaky Dude arrives as backup, having composed himself enough to shoot the guns out of a couple of bad guys' hands. Seems Dude might have a drinking problem, but he's also Chance's deputy, and the lawmen take Joe into custody where the movie's waiting game begins. Can Chance, Duke (always battling the battle) and Chance's other deputy, Stumpy (Walter Brennan), aging and falling apart physically, keep Joe locked up until the U.S. marshal's arrival several days later to take Joe into custody for trial before Burdette's clan tries to free him In a few short minutes of screentime, the main story that drives most of Rio Bravo's 2 hours and 20 minutes has been set. Sideplots await, but all basically will converge in the main thread. Though nearly 2½ hours long, Hawks doesn't rush his film along, yet somehow he still keeps it moving and it holds its length incredibly well.

I'm not reporting earth-shattering news when I inform readers that Howard Hawks belongs to that select group of directors who excelled in every genre he attempted. One thing that sets Rio Bravo apart from Hawks' other works is that, while it resides in the Western genre, it snatches from many others — romantic comedies, war tales, detective stories, social dramas, even musicals. As film critic Richard Schickel says on a commentary track for Rio Bravo, Hawks liked saying

that he loved to steal from himself. He'd do it again by practically remaking Rio Bravo as El Dorado eight years later, once again starring Wayne but with Robert Mitchum in the Dean Martin role. The plots diverge enough, as do the characters, (Mitchum plays a drunken sheriff as opposed to deputy while Wayne took on the role of gunfighter for hire helping a rancher's family get even with the rival rancher who killed their patriarch) to prevent it from being an exact facsimile. (Another shared aspect between the two films: screenwriter Leigh Brackett, who co-wrote Rio Bravo with Jules Furthman and wrote El Dorado by herself.) In the case of Rio Bravo, dialogue in the romantic sparring between Chance (Wayne) and possibly shady lady Feathers (Angie Dickinson) sounds lifted directly from To Have and Have Not, which Furthman co-wrote with William Faulkner. The relationship between Chance and Stumpy seems like a continuation of the one Wayne's Dunson and Brennan's Groot had in Red River, only minus Dunson's darkness. Part of Howard Hawks' greatness grew from his gift of swiping things from his previous films while changing the recipe just enough to make it fresh — a skill other self-plagiarists such as John Hughes never pulled off since they lacked Hawks' inherent talent, skill and imagination.

that he loved to steal from himself. He'd do it again by practically remaking Rio Bravo as El Dorado eight years later, once again starring Wayne but with Robert Mitchum in the Dean Martin role. The plots diverge enough, as do the characters, (Mitchum plays a drunken sheriff as opposed to deputy while Wayne took on the role of gunfighter for hire helping a rancher's family get even with the rival rancher who killed their patriarch) to prevent it from being an exact facsimile. (Another shared aspect between the two films: screenwriter Leigh Brackett, who co-wrote Rio Bravo with Jules Furthman and wrote El Dorado by herself.) In the case of Rio Bravo, dialogue in the romantic sparring between Chance (Wayne) and possibly shady lady Feathers (Angie Dickinson) sounds lifted directly from To Have and Have Not, which Furthman co-wrote with William Faulkner. The relationship between Chance and Stumpy seems like a continuation of the one Wayne's Dunson and Brennan's Groot had in Red River, only minus Dunson's darkness. Part of Howard Hawks' greatness grew from his gift of swiping things from his previous films while changing the recipe just enough to make it fresh — a skill other self-plagiarists such as John Hughes never pulled off since they lacked Hawks' inherent talent, skill and imagination.Hawks originally intended the action and imagery that runs beneath the opening credits to be its own sequence in the film, but later decided just to use it to accompany the list of cast and crew to a quieter piece of Dimitri Tiomkin's score before the set piece in the bar officially launches Rio Bravo. He films the footage of a wagon train caravan at such a distance that you can't readily identify its contents or characters, but a careful viewer connects it later as being the approach of the wagon train of Pat Wheeler

(Ward Bond), who turns up shortly after the opening incident. At first, the audience can't be certain how to take the arrival of this man and his large crew, which includes a young gunman named Colorado (played by Ricky Nelson, teen idol and sitcom star at the time, who turns in a solid performance). For all the audience knows, these could be people sent to break Joe Burdette out of the jail where Stumpy handles most of his supervision. Dude, by then sobered up and handling more of his duties as deputy to Chance's Presidio County Texas sheriff, stops the wagon train in the middle of the town's main thoroughfare and insists that Wheeler and all of his men remove their weapons and hang them on a fence. They'll be free to collect the firearms when they depart the town again. (Wouldn't you love to watch Rio Bravo with the National Rifle Association's head flunky Wayne LaPierre and see how he reacts to law enforcement working for John Wayne in a Western that enforcing those rules?) Wheeler and those in his employ grumble at first, but soon comply. When Chance shows up, we realize he and Wheeler go way back on friendly terms, though Wheeler advises the sheriff they need to be careful where they store their cargo — it contains a large amount of dynamite. (Paging Chekhov if you don't think that's going to pay off somewhere down the road.)

(Ward Bond), who turns up shortly after the opening incident. At first, the audience can't be certain how to take the arrival of this man and his large crew, which includes a young gunman named Colorado (played by Ricky Nelson, teen idol and sitcom star at the time, who turns in a solid performance). For all the audience knows, these could be people sent to break Joe Burdette out of the jail where Stumpy handles most of his supervision. Dude, by then sobered up and handling more of his duties as deputy to Chance's Presidio County Texas sheriff, stops the wagon train in the middle of the town's main thoroughfare and insists that Wheeler and all of his men remove their weapons and hang them on a fence. They'll be free to collect the firearms when they depart the town again. (Wouldn't you love to watch Rio Bravo with the National Rifle Association's head flunky Wayne LaPierre and see how he reacts to law enforcement working for John Wayne in a Western that enforcing those rules?) Wheeler and those in his employ grumble at first, but soon comply. When Chance shows up, we realize he and Wheeler go way back on friendly terms, though Wheeler advises the sheriff they need to be careful where they store their cargo — it contains a large amount of dynamite. (Paging Chekhov if you don't think that's going to pay off somewhere down the road.) Labels: 50s, Angie Dickinson, Blog-a-thons, Dean Martin, Faulkner, Hawks, John Hughes, Mitchum, Movie Tributes, W. Brennan, Wayne

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

"My Rifle, My Pony and Me" (Rio Bravo tribute, Part II)

While Sheriff Chance took on a major task by arresting Joe Burdette and incarcerating him in his small Presidio County jail, with Stumpy left to guard the bad guy most of the time, he still bears the responsibility for maintaining the law elsewhere in his town, something he accomplishes through street patrols and his nights staying at The Hotel Alamo (of all the names to pick) run by Carlos Robante (Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez) and his wife Consuela (Estelita Rodriguez). One night, a poker game piques his interest as two of the players (Angie Dickinson, Walter Barnes) fit the profile of two hustlers warned about on handbills. After a cursory investigation, Chance arrests the woman, who goes by the name Feathers. She declares her innocence and Chance fails to find the crooked cards on her after she's left the table following a huge winning streak. When he returns though, he does find the stacked deck on the man, who has raked it in since her departure and tells him to return his ill-gotten gains and be on the morning stagecoach. He suggests that Feathers do the same, but she decides to stick around.

That next day, the Burdettes arrive as expected, led by Joe's smooth brother Nathan (John Russell, the gaunt, veteran actor of mostly Westerns where he usually played the villain. His second-to-last film was as the cold-blooded killer in Clint Eastwood's Pale Rider). He asks Chance why the streets appear so full of people. Chance offers no explanation, but suggests that perhaps gawkers came to town, drawn to the possibility that the Burdettes planned to put on a show.

Chance makes his nightly trek to the Hotel Alamo. When he gets there, Spencer pulls him over for a drink. The wagon master has heard of the trouble Chance faces. "A game-legged old man and a drunk. That's all you got?" Spencer asks in disbelief. "That's what I got," Chance responds. Spencer offers himself and his men as help against the Burdettes, but the sheriff expresses reluctance to take responsibility for others. He does ask about the confident young gunman Colorado that Spencer has hired. If he is as good as he thinks he is and lacks the family ties of the older men, Chance would be willing to take him on if Colorado agrees. Spencer calls Colorado over, but the young man politely declines, earning Chance's respect for being smart enough to know when to sit out a fight. Not long afterward, while Feathers flirts again and Chance urges her to get on the morning stage, shots ring out on the street and Spencer falls dead. Later, Nathan Burdette makes his first visit to see his brother Joe, despite Stumpy's withering verbal assaults, at the jail. First, Nathan wants the sheriff to

explain why his brother looks so beat up. "He didn't take too kindly to being arrested for murder," Chance tells Nathan while Joe denies the shooting was murder. Nathan asks how Chance can be so certain or, at the very least, why Joe isn't being tried where the alleged murder occurred. Chance nixes that idea, content to let the U.S. marshal handle Joe Burdette and try him elsewhere. Nathan silkily makes no overt threats, but certainly implies that Joe might not remain in the Presidio County jail by the time that marshal shows up, especially if the sheriff relies on a drunk and an old man as his backup. Chance isn't in a mood to hide his cards. "You're a rich man, Burdette. Big ranch, pay a lot of people to do what you want 'em to do. And you got a brother. He's no good but he's your brother. He committed 20 murders you'd try and see he didn't hang for 'em," the sheriff spits out. "I don't like that kinda talk. Now you're practically accusing me," Nathan Burdette says, but Chance continues. "Let's get this straight. You don't like? I don't like a lot of things. I don't like your men sittin' on the road bottling up this town. I don't like your men watching us, trying to catch us with our backs turned. And I don't like it when a friend of mine offers to help and 20 minutes later he's dead! And i don't like you, Burdette, because you set it up." If war wasn't brewing before, it was now.

explain why his brother looks so beat up. "He didn't take too kindly to being arrested for murder," Chance tells Nathan while Joe denies the shooting was murder. Nathan asks how Chance can be so certain or, at the very least, why Joe isn't being tried where the alleged murder occurred. Chance nixes that idea, content to let the U.S. marshal handle Joe Burdette and try him elsewhere. Nathan silkily makes no overt threats, but certainly implies that Joe might not remain in the Presidio County jail by the time that marshal shows up, especially if the sheriff relies on a drunk and an old man as his backup. Chance isn't in a mood to hide his cards. "You're a rich man, Burdette. Big ranch, pay a lot of people to do what you want 'em to do. And you got a brother. He's no good but he's your brother. He committed 20 murders you'd try and see he didn't hang for 'em," the sheriff spits out. "I don't like that kinda talk. Now you're practically accusing me," Nathan Burdette says, but Chance continues. "Let's get this straight. You don't like? I don't like a lot of things. I don't like your men sittin' on the road bottling up this town. I don't like your men watching us, trying to catch us with our backs turned. And I don't like it when a friend of mine offers to help and 20 minutes later he's dead! And i don't like you, Burdette, because you set it up." If war wasn't brewing before, it was now.

The murder of Spencer fully incorporates the last two major characters more fully into the film and the action. With his boss dead, Colorado at first finds himself content to take his pay from the slain wagon master's possessions and remains determined to mind his own business. Once he witnesses some more of the Burdette brutality, Colorado decides to join up and Chance deputizes him. Colorado becomes part of the team and helps Chance escape an ambush, an ambush for which the sheriff seems prepared to occur, quickly pumping off rounds from his rifle. "You always leave the carbine cocked?" Colorado asks. "Only when I carry it," Chance replies. Originally, Hawks opposed casting Ricky Nelson, though the director admits he probably boosted box office. He had sought someone popular with young viewers, but felt Nelson — who turned 18 during filming — lacked age and experience for the part. Hawks had chased Elvis Presley for the role, but as often was the case, Col. Tom Parker demanded too much money for his client and the Rio Bravo production had to take a pass. The pseudo love affair between Feathers and Chance also heats up, though Wayne's discomfort with the romantic scenes with Dickinson is readily apparent. Wayne felt uneasy about the 25-year age gap between him and Dickinson. On top of that, nervous studio bosses wanted no implication made that Chance and Feathers ever sleep together. Double entendres and innuendos abound, but truthfully more sparks fly in brief scenes between Martin and Dickinson and Nelson and Dickinson than ever produce friction in the Wayne-Dickinson scenes. What becomes most interesting about the relationship between Feathers and Chance is Feathers' transformation into the sheriff's protector, keeping watch over him as he sleeps to make sure that no Burdette makes a move on him.

You don't need to know how the rest of Rio Bravo unfolds. Besides, part of what makes the film so fascinating and more than your ordinary Western comes from the multiple tones Hawks balances. A viewer seeing Rio Bravo for the first time couldn't positively predict what mood shall prevail by the final reel: light-hearted, tragic, heroic, romantic, some combination of those elements. At any given moment, you might change your mind. Most of this uncertainty reflects the nature of the character Dude. With the possible exception of Feathers, almost every other character in the film stays on a static path. Dude captures our attention the most because of the dynamics within him. Will he maintain the upper hand in his battle with booze or will he fall off the wagon again and if he does, what consequences does that

have for the others? Even sober, he's prone to depression, low self-esteem and self-pity. Still, he can croon a song or be a crack shot. A part this multifaceted requires a talented actor and back when Rio Bravo was made, Dean Martin wouldn't be one of the first names to jump to your mind. However, in the years 1958 and 1959, soon after the end of his partnership with Jerry Lewis, Martin turned in two impressive performances (perhaps three, but I haven't seen 1958's The Young Lions). In 1958, he gave a great turn as a professional gambler Bama Dillert in Vincente Minnelli's adaptation of the James Jones novel Some Came Running starring Frank Sinatra and Shirley MacLaine. He followed that with his astoundingly good work in Rio Bravo. While Martin continue to make entertaining films, for some reason those two years stand out as an aberration and he never got roles as good as Bama Dillert or Dude again.

have for the others? Even sober, he's prone to depression, low self-esteem and self-pity. Still, he can croon a song or be a crack shot. A part this multifaceted requires a talented actor and back when Rio Bravo was made, Dean Martin wouldn't be one of the first names to jump to your mind. However, in the years 1958 and 1959, soon after the end of his partnership with Jerry Lewis, Martin turned in two impressive performances (perhaps three, but I haven't seen 1958's The Young Lions). In 1958, he gave a great turn as a professional gambler Bama Dillert in Vincente Minnelli's adaptation of the James Jones novel Some Came Running starring Frank Sinatra and Shirley MacLaine. He followed that with his astoundingly good work in Rio Bravo. While Martin continue to make entertaining films, for some reason those two years stand out as an aberration and he never got roles as good as Bama Dillert or Dude again.Hawks' behind-the-scenes collaborators provided as much of the magic of Rio Bravo as its cast. From Russell Harlan's crisp and lush cinematography to Tiomkin's score that complements Hawks' leisurely pacing well. Tiomkin also teamed with lyricist Paul Francis West for the film's songs — "Cindy" and "My Rifle, My Pony and Me" in the extended musical interlude by Dude, Stumpy and

Colorado as well as the title song. Reportedly, Wayne joined the singing at one point until they decided it inappropriate for the sheriff to take part (and also because the Duke allegedly could not carry a tune). In another instance of borrowing from past work, at Wayne's suggestion, Tiomkin actually reworked the theme to Red River into the song "My Rifle, My Pony and Me." Tiomkin also composed "Degüello," aka "The Cutthroat Song," which the Burdettes play to psych out the good guys guarding Joe. The film claims the music comes from Mexico where Santa Anna's soldiers played it continuously to unnerve those holed up inside the Alamo. Wayne loved the music and the story so much, even though the tale wasn't true, he used it in his film The Alamo the following year. His screenwriting team of Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett both had worked with Hawks as a team and separately before and after Rio Bravo. Previously, Furthman and Brackett co-wrote Hawks' classic 1946 take on The Big Sleep. Furthman also co-wrote Come and Get It and To Have and Have Not and did a solo turn on Only Angels Have Wings. The legendary Brackett, despite her extensive screenwriting work, made a name for herself as a novelist, largely in the male-dominated field of science fiction. In Schickel's commentary, he refers to Brackett as an example of a real life Hawksian woman. In fact, before her death, the last screenplay she co-wrote was The Empire Strikes Back. In another non-Hawks project, she returned to Philip Marlowe when she wrote the screenplay for Robert Altman's The Long Goodbye. In addition to the Hawks titles already mentioned for Brackett, she also wrote the screenplay for 1962's Hatari! and co-wrote 1970's Rio Lobo. The DVD commentary also includes director John Carpenter, who names Hawks as his favorite director, and paid tribute to Leigh Brackett by naming the sheriff in the original Halloween after her.

Colorado as well as the title song. Reportedly, Wayne joined the singing at one point until they decided it inappropriate for the sheriff to take part (and also because the Duke allegedly could not carry a tune). In another instance of borrowing from past work, at Wayne's suggestion, Tiomkin actually reworked the theme to Red River into the song "My Rifle, My Pony and Me." Tiomkin also composed "Degüello," aka "The Cutthroat Song," which the Burdettes play to psych out the good guys guarding Joe. The film claims the music comes from Mexico where Santa Anna's soldiers played it continuously to unnerve those holed up inside the Alamo. Wayne loved the music and the story so much, even though the tale wasn't true, he used it in his film The Alamo the following year. His screenwriting team of Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett both had worked with Hawks as a team and separately before and after Rio Bravo. Previously, Furthman and Brackett co-wrote Hawks' classic 1946 take on The Big Sleep. Furthman also co-wrote Come and Get It and To Have and Have Not and did a solo turn on Only Angels Have Wings. The legendary Brackett, despite her extensive screenwriting work, made a name for herself as a novelist, largely in the male-dominated field of science fiction. In Schickel's commentary, he refers to Brackett as an example of a real life Hawksian woman. In fact, before her death, the last screenplay she co-wrote was The Empire Strikes Back. In another non-Hawks project, she returned to Philip Marlowe when she wrote the screenplay for Robert Altman's The Long Goodbye. In addition to the Hawks titles already mentioned for Brackett, she also wrote the screenplay for 1962's Hatari! and co-wrote 1970's Rio Lobo. The DVD commentary also includes director John Carpenter, who names Hawks as his favorite director, and paid tribute to Leigh Brackett by naming the sheriff in the original Halloween after her.Tweet

Labels: 50s, Altman, Angie Dickinson, Blog-a-thons, Dean Martin, Eastwood, Elvis, Hawks, Jerry Lewis, John Carpenter, MacLaine, Movie Tributes, Sinatra, Star Wars, W. Brennan, Wayne

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, May 17, 2013

Enough beef for hungry cinephiles

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post originally appeared Sept. 30, 2008. I'm re-posting it as part of The Howard Hawks Blogathon occurring through May 31 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie Lover

By Edward Copeland

Has any filmmaker shown mastery in more genres than Howard Hawks? Sixty years ago today, Hawks released one of his best Westerns (not a motel) in Red River, which also gave John Wayne one of his best roles and Montgomery Clift a notable early screen appearance.

Hawks made other great Westerns (most notably Rio Bravo, which also featured Wayne and Walter Brennan), but Red River, despite its abrupt climax, remains my favorite with its tale of a long cattle drive, surrogate father-son conflict and unmistakable gay subtext. Wayne admittedly was a limited actor, but he always was at his best when he played a character steeped in darkness and obsession such as Thomas Dunson here or Ethan Edwards in John Ford's The Searchers. He's helped immeasurably by getting to act opposite the young Clift, the antithesis of acting style when compared to Wayne. Hawks' direction of the film itself truly amazes, especially in the many scenes of the huge numbers of cattle, all done in the days without the easy out of CGI (A scene of the drive even earned a shoutout in Peter Bogdanovich's great 1971 film The Last Picture Show). He also manages to include plenty of his trademark humor, mostly through the ensemble of supporting character actors led by Brennan (whose character loses his false teeth in a poker game) and including Hank Worden (the decrepit waiter in Twin Peaks for those unfamiliar with the name) who gets plenty of throwaway lines such as how he doesn't like when things go good or bad, he just wants them to go in between.

Hawks even manages to toss in what may be an example of the ultimate Hawksian woman with Joanne Dru as Tess Millay, who doesn't let a little thing such as an arrow stop her from nagging a man with questions. Hawks astounds viewers to this day with his versatility among genres: Westerns, screwball comedies, musicals, war films, noirs, sci-fi — pick a genre and Hawks probably took it on and scored. It's a mystery to me why his name isn't brought up more by people other than the most obsessive film buffs. Red River isn't my favorite Hawks, but it's one of his many great ones and continues to entertain after 60 years.

Tweet

Labels: 40s, Bogdanovich, Clift, Hawks, John Ford, Movie Tributes, Twin Peaks, W. Brennan, Wayne

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Leave the rooster story alone. That's human interest.

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post originally appeared Jan. 18, 2010. I'm re-posting it as part of The Howard Hawks Blogathon occurring through May 31 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie Lover

By Edward Copeland

The list of remakes that exceed the original is a short one, especially when the original was a good one, but there never has been a better remake than Howard Hawks' His Girl Friday, which took the brilliance of The Front Page and turned it to genius by making its high-energy farce of an editor determined by hook or by crook to hang on to his star reporter by turning the roles of the two men into ex-spouses. Icing this delicious cake, which marks its 70th anniversary today, comes from casting Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell as the leads.

Words open His Girl Friday declaring that it takes place in the dark ages of journalism when getting that story justified anything short of murder, but insists that it bears no resemblance to the press of its day, 1940 in this case. What saddens me today is, despite the ethical lapses and underhandedness and downright lies

committed by the reporters in this version (and really all versions based on the original play The Front Page by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, themselves once Chicago journalists), their energetic devotion to capturing the story seems downright heroic compared to the herd mentality and lack of intellectual curiosity we see exhibited most of the time today by pack journalists such as the White House press corps. It's really why the first two film versions of the play are the only ones that work. The 1931 Lewis Milestone adaptation starring Adolphe Menjou definitely belonged to its time and Hawks' take with its inspired twist came along close enough to remain relevant. When Billy Wilder tried to remake the original in 1974 as a period piece with Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau, it fell flat because in the era of Vietnam and Watergate, journalists actually existed in a moment of heroism for their profession. The 1988 disaster Switching Channels returned to the His Girl Friday model with Burt Reynolds and Kathleen Turner and tried to set it in the world of cable news but the only update they came up with was hiding the fugitive in a copy machine instead of a rolltop desk.

committed by the reporters in this version (and really all versions based on the original play The Front Page by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, themselves once Chicago journalists), their energetic devotion to capturing the story seems downright heroic compared to the herd mentality and lack of intellectual curiosity we see exhibited most of the time today by pack journalists such as the White House press corps. It's really why the first two film versions of the play are the only ones that work. The 1931 Lewis Milestone adaptation starring Adolphe Menjou definitely belonged to its time and Hawks' take with its inspired twist came along close enough to remain relevant. When Billy Wilder tried to remake the original in 1974 as a period piece with Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau, it fell flat because in the era of Vietnam and Watergate, journalists actually existed in a moment of heroism for their profession. The 1988 disaster Switching Channels returned to the His Girl Friday model with Burt Reynolds and Kathleen Turner and tried to set it in the world of cable news but the only update they came up with was hiding the fugitive in a copy machine instead of a rolltop desk.Each time I write one of these anniversary tributes, no matter how many times I've seen the film in question (and I can't count that high when we're discussing Friday, I try to watch the movie again, in a quest for fresh thoughts and reminders of lines that may have slipped my mind. In nearly every, case I notice something new (and with the rapid-fire pace of Friday's dialogue, remembering them all borders on impossible). What stood out as I

started this salute wasn't just the work-a-day newshounds it depicts compared to the state of the industry today but the social subtext emerged more prominently this time. It's not that I've missed or ignored it before, but it's the light-speed comic hijinks that keeps me coming back. The story's main focus may concern Walter Burns (Grant), that sneaky editor of the Morning Post, trying to keep his ex-wife Hildy Johnson (Russell) from leaving the paper and his life to wed insurance agent Bruce Baldwin, who looks like that fellow in the movies, you know, Ralph Bellamy (who fortunately plays Bruce). However, the story Walter uses to keep his hooks into Hildy concerns that of Earl Williams (John Qualen), a man who killed a cop and received a ticket on a bullet train to the gallows by a politically hungry Republican mayor with an eye on unseating the Democratic, anti-death penalty governor, despite the fact the reporters and many others believe Earl's mental

started this salute wasn't just the work-a-day newshounds it depicts compared to the state of the industry today but the social subtext emerged more prominently this time. It's not that I've missed or ignored it before, but it's the light-speed comic hijinks that keeps me coming back. The story's main focus may concern Walter Burns (Grant), that sneaky editor of the Morning Post, trying to keep his ex-wife Hildy Johnson (Russell) from leaving the paper and his life to wed insurance agent Bruce Baldwin, who looks like that fellow in the movies, you know, Ralph Bellamy (who fortunately plays Bruce). However, the story Walter uses to keep his hooks into Hildy concerns that of Earl Williams (John Qualen), a man who killed a cop and received a ticket on a bullet train to the gallows by a politically hungry Republican mayor with an eye on unseating the Democratic, anti-death penalty governor, despite the fact the reporters and many others believe Earl's mental illness should stop his hanging. Qualen, a solid character actor in many films, and Mollie Malloy (Helen Mack), a woman who befriended Earl prior to the slaying and who the tabloids misrepresent as his lover and a prostitute, stand apart as the only characters in this screwball farce who play it completely straight. (In an all-time bit of miscasting, in the Wilder remake, Carol Burnett got the Mollie Malloy role. Of course, the nearly 50-year-old Jack Lemmon also was engaged to the 28-year-old Susan Sarandon in that film.) His Girl Friday requires neither Qualen nor Mack to garner laughs like every other character. As the courthouse reporters behave particularly cruelly to Mollie at one point, only Hildy comforts her. "They ain't human," Mollie cries. "I know," Hildy sympathizes. "They're newspapermen." Hildy realizes the jobless Earl spent too much time listening to socialist speeches in the park and his fascination with the concept of "production for use" led to his fatal error.

illness should stop his hanging. Qualen, a solid character actor in many films, and Mollie Malloy (Helen Mack), a woman who befriended Earl prior to the slaying and who the tabloids misrepresent as his lover and a prostitute, stand apart as the only characters in this screwball farce who play it completely straight. (In an all-time bit of miscasting, in the Wilder remake, Carol Burnett got the Mollie Malloy role. Of course, the nearly 50-year-old Jack Lemmon also was engaged to the 28-year-old Susan Sarandon in that film.) His Girl Friday requires neither Qualen nor Mack to garner laughs like every other character. As the courthouse reporters behave particularly cruelly to Mollie at one point, only Hildy comforts her. "They ain't human," Mollie cries. "I know," Hildy sympathizes. "They're newspapermen." Hildy realizes the jobless Earl spent too much time listening to socialist speeches in the park and his fascination with the concept of "production for use" led to his fatal error.

Social message aside, it's the earth-shattering cosmic comic chemistry of Grant and Russell, aided by Bellamy's perfect innocent foil and countless supporting vets. (One of them, Billy Gilbert, plays Mr. Pettibone (Roz holds his tie in the photo above) and I wish I could have found a good closeup photo of him because I think it's hysterical how much 9/11 mastermind/terrorist asshole Khalid Sheikh Mohammed resembles Gilbert in KSM's arrest mugshot.) The lines come fast and furious. While many do come from the original Hecht-MacArthur play, Hawks gets the credit for the film's amazing speed (though screenwriter Charles Lederer deserves more kudos). Still, in the end, Cary and Roz make the dialogue sizzle and Grant's physical touches serve as a master class in comic movement on film. Watch every little bounce he makes as Hildy kicks him beneath the table when he's trying to get things past poor Bruce and you'll crack up every time. Originally, I was writing down all my favorite lines, planning to try to work them all into this tribute, but then I thought: Maybe not everyone has seen His Girl Friday, even after 70 years,

_04.jpg)

Tweet

Labels: 40s, Bellamy, Burt Reynolds, Cary, Hawks, Hecht, K. Turner, Lemmon, Matthau, Menjou, Milestone, Movie Tributes, Remakes, Roz Russell, Susan Sarandon, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, August 03, 2012

Edward Copeland's Top 100 of 2012 (100-81)

With the release of the latest Sight & Sound poll, conducted every 10 years to determine the all-time best films, The House Next Door blog of Slant Magazine invited some of us not lucky enough to contribute to the S&S list to submit our own Top 10s to The House, which posted mine today. Sight & Sound magazine, a publication of the British Film Institute, began its survey in 1952, using only critics. Its 2002 list boasted its largest sample yet, receiving ballots from 145 film critics, writers and scholars as well as 108 directors. The results can be found here, though a note claims the page isn't actively maintained, though it appears complete to me. Since I planned to revise my personal Top 10, posted as part of my Top 100 in 2007, I figured I owed it to my entire Top 100 to redo my entire list. As before, my rule is simple: A film must be at least 10 years old to appear on my list. Therefore, movies released between 1998 and 2002 might appear on this list whereas they couldn't on the 2007 version. The most difficult part of assembling these lists always involves determining rankings. It's an arbitrary process and once you get past the Top 10 or 20, not only do the placements seem rather meaningless but inclusion and exclusions of films begin to weigh on you. In fact, selecting No. 1 remains easy but if I could, I'd have tied Numbers 2 through 20 or so at No. 2. A lot of great films didn't make this 100 through no fault of their own, falling victim to my whim at the moment I made the decision of what made the cut and where it went. In parentheses after a director's name, you'll find a film's 2007 rank or, if it's new to the list, you'll see NR for not ranked or NE for not eligible. I also should note that this does not mean the return of this blog. I had committed to taking part in The House's feature prior to pulling the plug and completed most of this before signing off.

Part of the arbitrary nature of this list (and from the very first all-time 10-best list I compiled in high school) was to try to make sure I represented my favorite directors while still allowing for those films that might be a more singular achievement. (For example, my first high school list had to be sure to include a Woody Allen, a Huston, a Hitchcock, a Wilder, a Truffaut, an Altman.) The more great cinema you see, the harder it becomes to justify that since lots of directors deserve recognition and many films might be a filmmaker's strongest work. As I've caught up with a lot of Werner Herzog's work over the years, I felt he'd earned inclusion. I was torn between choosing Nosferatu or Aguirre: The Wrath of God to represent him, but opted for the vampire tale because Herzog's "reversioning" of Murnau's silent classic manages to be both a masterpiece of atmospherics and the best version of the Dracula tale put on screen.

Pedro Almodóvar’s career evolution has taken an arc that I imagine few could have anticipated. I know I certainly didn’t back in the 1980s, when his films mainly consisted of camp, color and sexual obsession. Around the time of 1997’s Live Flesh, the Spanish filmmaker’s style took an abrupt change, filtering genres through his unique perspective to exhilarating results that continue through last year’s The Skin I Live In. The greatest of this run of seven features happens to be the most recent film to make this new Top 100 list. Telling the story of two men caring for women they love, both of whom happen to be comatose, Almodóvar’s Oscar-winning screenplay manages to balance humor, pathos and even outlandish touches you’d never expect to make one helluva movie and the writer-director’s best film so far.

Littered along the highways of film history lie multiple tales of adversity breeding triumphs of cinema. As director Jules Dassin faced a possible subpoena from the House Un-American Activities Committee, presumably followed by blacklisting, at the end of the 1940s, producer Darryl Zanuck gave him an exit strategy. Dassin flew to London to hurriedly begin filming an adaptation of the novel Night and the City, which he’d never read, and as a result produced one of the greatest noirs of all time. Not only did he make the movie on the fly, Zanuck even stuck him with creating a role for Gene Tierney, nearly suicidal after a bad love affair. The novel’s author, Gerald Kersh, hated the movie about hustler Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark) scheming to bring Greco-Roman wrestling to London while ducking all sorts of colorful characters played by wonderful actors such as Francis L. Sullivan, Googie Withers, Herbert Lom, Hugh Marlowe and Mike Mazurki. Of course, Kersh’s gripe was understandable — the film bore no resemblance whatsoever to his novel other than the title. However, that didn’t prevent it from being a damn fine film.

It takes a lot to fool me and, in retrospect, I should have seen the final twist coming, but I didn't because Sayles crafted in his best film a compelling story in which the plot turn was unexpected and the movie’s story didn't hinge on it. Even if the secret never had been revealed, this portrait of skeletons from the past and their influence on the lives of people in the present still would resonate. Sayles assembles a helluva ensemble including Chris Cooper, Elizabeth Peña, Matthew McConaughey, Kris Kristofferson, Joe Morton and, in one great single scene, Frances McDormand, to name but a few. Sayles has made some good films since Lone Star, but none come close to equaling the artistry, vitality and humanity of this one. I await another great one from him.

Set piece after set piece, Hitchcock puts Cary Grant through the paces and pulls the viewer along to his most purely entertaining offering. Grant never loses his cool as he's hunted by everyone, James Mason makes a suave bad guy and Martin Landau a perfectly sinister hired thug. With cameos by four former U.S. presidents. There's not much else to say about it: It's not an exercise in style or filled with layers and depth, it's just damn fun. In fact, it’s as much a comedy as a thriller.

There's something to be said for quitting while you're ahead and Charles Laughton, one of the finest screen actors ever, certainly did with the only film he ever directed. The film's influences seem more prevalent than people who have actually seen this disturbing thriller with the great Robert Mitchum as the creepy preacher with love on one hand and hate on the other and the legendary Lillian Gish as the equivalent of the old woman who lived in a shoe, assuming the old woman was well armed.

In describing the film that put Kurosawa on the world’s radar as a major filmmaker, I’m going to let Robert Altman speak for me. This quote comes from his introduction to the Criterion Collection edition of the movie. "Rashomon is the most interesting, for me, of Kurosawa's films.…The main thing here is that when one sees a film you see the characters on screen.…You see very specific things — you see a tree, you see a sword — so one takes that as truth, but in this film, you take it as truth and then you find out it's not necessarily true and you see these various versions of the episode that has taken place that these people are talking about. You're never told which is true and which isn't true which leads you to the proper conclusion that it's all true and none of it's true. It becomes a poem and it cracks this visual thing that we have in our minds that if we see it, it must be a fact. In reading, in radio — where you don't have these specific visuals — your mind is making them up. What my mind makes up and what your mind makes up…is never the same."

For years, my standard response when asked about Raging Bull was that it was a film easier to admire than love. Each time that I’d see the movie again though, that point-of-view became less satisfactory because, as any great film should, the film kept rising higher in my esteem. In the film's opening moments, when Robert De Niro plays the older, fat Jake preparing for his lounge act in 1964 before it cuts to the ripped fighter in 1941, even though I consciously know both versions of La Motta were played by the same actor and that De Niro was that actor, the performance so entrances that I actually ask, "Who is this guy and why hasn't he made more movies?" To gaze at the way he sculpted his body into the shape of a believable middleweight boxer, sweat glistening in Michael Chapman's gorgeous black-and-white cinematography, truly makes an impressive achievement. Acting isn't the proper word for what De Niro does here. He doesn't portray Jake La Motta, he becomes Jake La Motta, or at least the screen version, and leaves all vestiges of Robert De Niro somewhere else. Even when De Niro turns in good or great work in other roles, they never come as close to complete immersion as his La Motta does.

"Out of the worst crime novels I have ever read, Jules Dassin has made the best crime film I've ever seen," François Truffaut wrote about Rififi in his book The Films in My Life. I haven't read the Auguste Le Breton novel, but I don't doubt Truffaut's word. Dassin structures the film like a solid three-act play. Act I: Planning the heist. Act II: Carrying it out. Act III: The aftermath. Dassin fine-tunes each of the film's element to the point that Rififi practically runs as a machine all its own. The various characters behave more as chess pieces to be moved around as the story's game requires than as representatives of people. One single sequence though makes Rififi a landmark both in films and particularly heist movies: the robbery itself. Dassin films this in a 32-minute long silent sequence. No one speaks. Keeping everything as quiet as possible becomes the thieves' No. 1 priority. It's absolutely riveting. You'll be holding your breath as if you were involved in the crime yourself.

Howard Hawks appears for the first time on the list with a Western starring John Wayne that turned out to be so much fun they remade it (more or less) seven years later as El Dorado. I’ll stick with the original where the Duke’s allies include a great Dean Martin as a soused deputy sheriff, young Ricky Nelson and the always wily Walter Brennan. Wayne even gets to romance Angie Dickinson. No deep themes hidden here, though it's more layered than your typical Western. Still, that doesn't mean you can't kick up your spurs and enjoy.

The first time was the charm. One of the few insightful comments I heard on the 2007 AFI special was when Martin Scorsese said that in many ways he finds the primitive stop-motion effects of the original King Kong more impressive than later CGI versions. He's absolutely right. The 1933 version also offers more thrills and emotions (and in half the time) than Peter Jackson's technically superior but dramatically inferior and unnecessary remake. Let’s not even discuss the 1976 version.

When L.A. Confidential debuted on this list in its first year of eligibility in 2007, I wrote, “Of the films of fairly recent vintage, this is one that grows stronger each time I see it, earning comparisons to the great Chinatown…Well acted (even if Kim Basinger's Oscar was beyond generous), well written and well directed, I believe L.A. Confidential’s reputation will only grow greater as the years go on — yet it lost the Oscar (and a spot on the AFI list) to the insipid Titanic.” When I re-watched the film recently, my prediction proved to be spot-on as it only deepens as an experience and an entertainment as time passes. It still boggles my mind that with Russell Crowe, Guy Pearce, Kevin Spacey and James Cromwell (just to name four) delivering impeccable work that only Basinger landed a nomination, but losing best picture and director to James Cameron and Titanic remains the bigger crime.

Simply put: The tensest comedy ever made and perhaps Scorsese's most underrated film. Griffin Dunne plays the perfect beleaguered straight man enveloped by a universe of misfits and oddballs in lower Manhattan when all he wanted to do was get laid. It’s hard to imagine that this movie nearly became a Tim Burton project, but thanks to the many setbacks Scorsese endured attempting to make The Last Temptation of Christ, the film ended up being his — and recharged his batteries as well. While Scorsese has made great films since, I’d love to see him step back sometime and make another indie feature like After Hours on the fly just to see what happens. Joseph Minion wrote an excellent script and this represents one case where I think the changed ending actually proves superior to the originally intended one. By the way, whatever happened to Joseph Minion?

Watchability often gets undervalued when rating a film's worth, but I never tire of sitting through this thrill ride. One aspect that has impressed me since I first saw it as a teen back in 1985 (and I went two nights in a row, dragging my parents to it on the second) was its attention to detail such as Marty arriving in 1955 and mowing down a pine tree on the farm of the deranged man trying to “breed pines.” Then, when he returns to 1985, Twin Pines Mall now bears the sign Lone Pine Mall. It’s just a quiet sight gag in the background without any overt attempt to call attention to the joke. You either catch it or you don’t. I always admire films that respect audiences like that, especially when they happen to be this much fun. With equal touches of satire, suspense and genuine emotion, Back to the Future elicits pure joy. No matter how many times I see it, the final sequence where they prepare to send Marty back to 1985 holds me in rapt attention as I wonder if this time might be the time he doesn't actually make it.

A comedy about the Vietnam War that's full of blood and set in Korea, just as a matter of subterfuge. The film that put Altman on the map and inspired one of TV's best comedies (until it got too full of itself), MASH still holds up with its brilliant ensemble and wicked wit. I still wish the TV show had kept that theme song with its lyrics. Through early morning fog I see/visions of the things to be/the pains that are withheld for me/I realize and I can see.../That suicide is painless/It brings on many changes/and I can take or leave it if I please.

Back in 1985, before Goodfellas and The Sopranos really mixed mob stories with jet black comedy, the great director John Huston, in his second-to-last film, brought to the screen an adaptation of Richard Condon's Mafia satire Prizzi's Honor, complete with great performances and some of the most memorable lines ever collected in a single film. Huston may have been in the twilight of his days, but his filmmaking prowess was as strong as ever. Jack Nicholson disappeared into the role of Charley Partanna more than he had any role in recent memory. Kathleen Turner matched well with Nicholson as Charley's love whose work outside the house causes problems. William Hickey gave an eccentric and indelible portrait of the aging don. Finally, John's daughter Anjelica made up for a misfire of an acting debut decades earlier with her brilliant performance as the scheming Maerose and took home one of the most deserved supporting actress Oscars ever given.

Before Zhang Yimou started being obsessed with spectacle and martial arts, film after film, he produced some of the greatest personal stories in the history of movies, especially when his muse was the great and beautiful Gong Li. This film was their first truly flawless effort as Gong plays the young bride of a powerful lord who already has multiple wives and who encourages the sometimes brutal competition between the women.

"The film actually is like a snail — it kind of turns in on itself and becomes itself," Altman describes his film in an interview on its DVD. One of the many "comebacks" of Robert Altman's career, this brilliant Hollywood satire holds up viewing after viewing because it's so much more than merely a satire. Thanks to Tim Robbins' superb performance as the sympathetic heel of a Hollywood executive and the cynical yet deeper emotional punch of Michael Tolkin's script, Altman wows from the opening eight-minute take to one of the greatest final punchlines in movie history. However, the more times you see it, the more you discover to see. While some specific references have aged, the movie's relevance remains — now more than ever.

Schindler’s List marked an important moment in Spielberg’s development as a filmmaker: Peter Pan finally grew up. It’s a harrowing, well-made movie that everyone should see. At the same time, I can foresee a time when it slips off this list entirely. It isn’t the fault of the film — I find it nearly flawless. However, if someone placed a gun to my head and ordered me to choose to watch either Schindler’s or one of Spielberg’s best post-1993 films such as Catch Me If You Can or Minority Report, I’d opt for one of the latter two. Are they better films than Schindler’s List? I can’t say that. However, the epic holocaust tale isn’t a film you find yourself wanting to pop a bowl of popcorn and watching on a whim. As I said earlier, for me at least, rewatchability remains an important factor. I’ve seen Schindler’s List three times but I haven’t reached the point where I want to go through that wrenching experience again.

Bergman once said that by the time he was done making Wild Strawberries, the film really belonged more to Victor Sjöström, who played Borg, the renowned professor and lauded physician about to receive an honorary degree. The film marked Sjöström 's return from semi-retirement, but he already was a legend as the first true Swedish acting-directing star. Borg decides to drive his old Packard to the event instead of flying to meet his son. The journey becomes more than just a road trip for the professor, but a metaphysical trek through his past as he questions what led him to this moment. As the car winds closer to the ceremony, Borg's inner journey does as well as he comes to realize that for all his scientific training, the only thing he can't analyze is himself. "The day's clear reality dissolves into even clearer remnants of memory," he says. Wild Strawberries represents Bergman growing into his powers as a filmmaker and while it may concern a 78-year-old man examining his life, the subject proves as timeless for people of any age as the film itself.

Tweet

Labels: Almodóvar, Altman, D. Zanuck, Dassin, Hawks, Herzog, Hitchcock, Huston, Ingmar Bergman, Kurosawa, Laughton, Lists, Murnau, Sayles, Scorsese, Spielberg, Tim Burton, Truffaut, Zemeckis, Zhang Yimou

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Edward Copeland's Top 100 of 2012 (80-61)

People like to mock Frank Capra as simple-minded at times and this film especially, but it remains a rousing indictment of corruption in Washington that echoes to this very day. It's too bad that a filibuster doesn't still mean that a senator has to do what Jefferson Smith did and hold the floor for as long as he can instead of the procedural gimmick it's turned into today that prevents legislation from moving out of the Senate. Still, whenever I catch Mr. Smith, no matter how long it has been on, I have to watch until the end. It's the curse of being both a movie buff and a political junkie. In a way, with recent events, it seems to have a bit of timeliness beneath the treacle and idealistic love of how this country should work.

When people think Ingmar Bergman, they think heavy, but here flows one of his lightest and most enjoyable concoctions. In an introduction made for the Criterion edition of the film, Bergman remarks how Smiles changed everything for him. At the time, he was broke and living off the actress Bibi Andersson when his studio entered the film at Cannes and it won a prize (best poetic humor) and became an international success. Bergman says it was a turning point for both him and his studio, earning him free rein to go on and make even more of the greatest films of all time. The film contains obvious echoes of The Rules of the Game, though Smiles more than stands on its own with its tale of love and adultery, male vanity and female cunning, aging and youth. It's not only a delight as a film but inspired the great Stephen Sondheim to write one of his earliest great scores as composer and lyricist in A Little Night Music. Isn't it rich?

The Weinstein P.R. machine spun so much press off this film's twist that I think it takes away from how great a movie had developed before that plot turn even happens. I was fortunate enough to see it early, before the hype went into overdrive, so I thought another story turn was the "twist" and relaxed and the real twist took me by complete, wonderful surprise. I hope someday new viewers will be able to see the film without knowing what lies ahead. Even if they don’t though, they will see a great study in human nature as well as great performances from Stephen Rea, Forest Whitaker, Miranda Richardson and Jaye Davidson.