Monday, September 23, 2013

More than any of us can bear

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This review originally ran on this blog on Aug. 9, 2006. I'm re-posting it for The Oliver Stone Blogathon occurring through Oct. 6 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie Lover

By Edward Copeland

I finally caught up with Oliver Stone's World Trade Center and, as indicated by many reviews, it certainly qualifies as the least Oliver Stone-like film Stone has made (though Oliver can't resist tossing in a couple of ghostly images of Jesus in a light but hey, at least it wasn't a mystical Indian). World Trade Center does end up being Stone's best work in quite some time.

Like most Stone movies, it contains fat that could be lost easily and in the battle of 9/11 movies, I still prefer United 93, even though Stone's film contains good performances. Cage gives his best straight performance in ages. Yes, I loved him in Adaptation, but I can't remember the last time he played a dramatic role in a movie that wasn't a time-waster.

He's also ably supported by Michael Pena as the fellow Port Authority officer trapped with him beneath the rubble, and Maria Bello as Cage's wife and Maggie Gyllenhaal as Pena's wife, awaiting word on their husbands' fates. If I prefer United 93 to World Trade Center, it's for one main reason: the emotional wounds of 9/11 remain so fresh, that it seems almost unnecessary to tell personal, albeit true, stories to wring emotion from a viewer. The relative anonymity of the passengers depicted in United 93 touched me more deeply than the fleshed-out stories in World Trade Center did, especially when they tack on a lapsed paramedic (Frank Whaley) and a former Marine (Michael Shannon) who abandons his office job, throws on his old uniform and marches into Ground Zero to help.

World Trade Center depicts well the confusion and communications breakdowns on 9/11, where the first responders themselves don't realize that a second plane has hit the second tower until well after they've arrived on the scene of the first tower.

As you expect from a Stone production, his production team delivers top-notch technical aspects. While World Trade Center as a film comes off as Stone's finest in ages, it's difficult to compete with the real images we saw that day. Paul Greengrass found a way to accomplish that in United 93. While Stone's film offers good performances, somehow the personal touch ends up being less emotionally satisfying.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, M. Gyllenhaal, Maria Bello, Michael Shannon, Nicolas Cage, Oliver Stone

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, October 27, 2011

"Come out, Neville!"

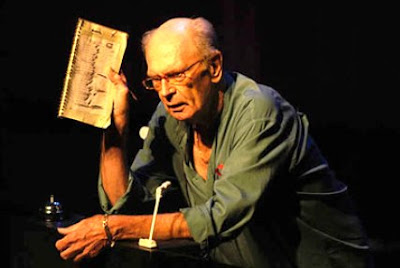

By le0pard13

Richard Matheson remains one of my favorite authors of all-time. When I attended the West Hollywood Book Fair a few years back, it re-ignited my interest in what I believe is the author's seminal novel, I Am Legend. Upon the book's initial release, it was an intriguing mix of horror and science fiction on the vampire mythology in the modern world. Arriving at the fair, I first stopped at one of the comic shop booths before heading over to the initial panel ("Ghost & Goblins: Exploring the Supernatural in Mystery Fiction") that featured author Charlie Huston (who writes his own vampire noir series). Among all of their wonderful comic book offerings, there was one particular graphic novel that stood out — the I Am Legend compilation of the Steve Niles and Elman Brown comic series from the early '90s. While I'd heard of it, I hadn't seen this adaptation in graphic form. Simply…wow. Between looking at its terrific illustrations and seeing how the artists constructed and re-told the author's tale, it was little wonder I was late to that book panel.

Then, upon finding and reaching the discussion, what were Charlie Huston and moderator Leslie Klinger discussing at that very moment? Yep. That same novel, which they then directly credited for being the impetus for much of the written work their panel was examining that day. Soon thereafter, author John Kenneth Muir noted in a blog post (which directly linked to blogger Brian Solomon's The Vault of Horror's list) The Cyber Horror Elite's Reading List: The Greatest Horror Literature of All-Time. This was the result from a panel of distinguished bloggers and writers condensing their favorite horror lit down to the cream of the crop*. What was at 15th rung? You guessed it. So, I felt the need to examine this pioneering novel (the chaser being that it was published the same year I was born). Besides, what better time than the month of Halloween

*That top 30 list drew such an interest-piquing response, B-Sol also posted the remaining novels, short stories and poems that didn't make it there or the honorable mentions list.

"I think the author who influenced me the most as a writer was Richard Matheson."

— Stephen King

It's been more than three decades since I first heard of this novel. I'd estimate I first read the work during the 1970s — which was likely in response to seeing the first of its film adaptations. The story is about one man, Robert Neville, and his fight to survive in a world that's been decimated by a '70s viral pandemic. It was eerie to me then, and strangely apropos with the recent Contagion film release. As far as the lead character is aware, he's the last uninfected man living on earth, and he's doing so among what's left of the population: the infected vampire horde wandering the Los Angeles nightscape. A couple of parallels are fairly obvious when reviewing the work. Daniel

Defoe's Robinson Crusoe tale seems relevant — especially when Neville is boarded up at night in his (desert island-like) home. The dwelling, like him, has become reinforced and hardened to the harsh reality, though his stash of food, drink, and classical music LPs keep him company. His 'Man Friday' could be the seemingly uninfected woman character, the biblically named Ruth. As well, the Cold War paranoia and fear track of the '50s permeates the tale. Matheson unfolds Robert Neville's story in a unique mix of flashback, science, mythological horror and ultimate irony. The fact that Matheson imagined a world (my hometown, actually), some 20 years beforehand, that even 21st century readers could still recognize on their first pass, proves the author was prophetically dead-on (so to speak) with this novel.

Defoe's Robinson Crusoe tale seems relevant — especially when Neville is boarded up at night in his (desert island-like) home. The dwelling, like him, has become reinforced and hardened to the harsh reality, though his stash of food, drink, and classical music LPs keep him company. His 'Man Friday' could be the seemingly uninfected woman character, the biblically named Ruth. As well, the Cold War paranoia and fear track of the '50s permeates the tale. Matheson unfolds Robert Neville's story in a unique mix of flashback, science, mythological horror and ultimate irony. The fact that Matheson imagined a world (my hometown, actually), some 20 years beforehand, that even 21st century readers could still recognize on their first pass, proves the author was prophetically dead-on (so to speak) with this novel.The American author/screenwriter's clever use of flashbacks used time (and its passage) as an interesting device in the novel's storytelling. It's a tool that subsequently leveled the distance between the moment in time the reader takes it in and that of the prescient world the author first imagined more than 50 years ago. I believe that tactic made it possible for the book reader to imagine Neville's plight of the damned and whatever future pandemic (natural or man-made) that could yet come. I Am Legend, then and now, was considered the first of the 'modern' vampire novels. Its prominent use of science to explain away old vampire lore, plus subjugate religion's treatment and links in ancient mythology, was a first. In the long run, the novel turned out to be the influential rootstock for so many authors' recent work in the vampire genre. It's hard to imagine many of today's modern blood-sucker tales (with the intertwining vampire and humans storylines) coming about without this one novel breaking through and freely mixing myth and science, or our own use of standards and technology, to explain things in the new vampire narratives. Even George Romero's unique zombie and apocalyptic series (that began with the equally seminal Night of the Living Dead film) would seem difficult to conjure without this novel breaching the surface in 1954.

I remember my younger brother telling me he'd seen The Last Man on Earth (1964) on some TV broadcast in the late '60s and trying to

explain the story to me. What can I say? Early teen recall is not worth the hormones they are imprinted upon. And it wasn't until the decade turned (a few years later) that I caught up to The Last Man on Earth on another late night showing. This Vincent Price feature, an Italian production, did have Richard Matheson write its original screenplay, but the subsequent changes and rewrites made to it had him pull his name from the film. However, this film does seem to come closest to the source and spirit of the author's novel. Yes, it suffers in its low cost production values, and the poor dubbing doesn't help matters. Still, I would say it's my sentimental favorite since it's the first telling of this story I ever saw (along with the next film) on celluloid. Price, as Dr. Robert Morgan, does embody Neville's tortured, mocking soul somewhat, although the film doesn't really attempt the book's powerful and ironic ending. Additionally, these first two pushed me to actually read the book that it was based upon.

explain the story to me. What can I say? Early teen recall is not worth the hormones they are imprinted upon. And it wasn't until the decade turned (a few years later) that I caught up to The Last Man on Earth on another late night showing. This Vincent Price feature, an Italian production, did have Richard Matheson write its original screenplay, but the subsequent changes and rewrites made to it had him pull his name from the film. However, this film does seem to come closest to the source and spirit of the author's novel. Yes, it suffers in its low cost production values, and the poor dubbing doesn't help matters. Still, I would say it's my sentimental favorite since it's the first telling of this story I ever saw (along with the next film) on celluloid. Price, as Dr. Robert Morgan, does embody Neville's tortured, mocking soul somewhat, although the film doesn't really attempt the book's powerful and ironic ending. Additionally, these first two pushed me to actually read the book that it was based upon.

The Omega Man (1971) was the first film adaptation that I saw in an actual movie theater. The Charlton Heston vehicle (along with the subsequent one decades later) began to shift this tale to more of the action/sci-fi genre in its execution and bearing. Gone are the plague aspects of the original work, along with the demythologized vampire text. Enter that period's introduction to the biological warfare scares as imagined by the screenwriter's adaptation in the midst of the Cold War. That, and homicidal mutants (meh). Although, The Omega Man was the only one among all the film conversions to make great and practical use of its L.A. setting and locations (like that originally used in the novel). Unfortunately, this film feels the most dated (hey, it's the '70s). Still, it was entertaining (as long as you let go of the superior narrative in the novel). The film's best moments are Heston being Heston (in his own inimitable way) and any of the scenes that had Rosalind Cash in them (I always admired the late actress and she was never in enough movies, for my liking). Yet I have to agree with my good friend, blogger Livius, on another of its charms:

"The other aspect that endears this film to me is Ron Grainer's achingly melancholic score — a real thing of beauty in my opinion."

This century's adaptation was the third film version, but the first to use the original title of Matheson's novel. I Am Legend (2007) also returned to the concept of a viral pandemic in this re-telling. And it has two of the most charismatic performances among all of these screen adaptations. Will Smith and Alice Braga, you say? Ah…no. Substitute Samantha the dog as lead actress and you have that couple

(and Will was hard pressed to garner more acting praise than her). For the record, Ms. Braga does indeed look better than the dog, but Sam simply acted better. Unfortunately, the film overemphasized its special effects and action over the original story's tenets. Plus, this one was a prime example of the filmmakers' tendency to overuse computer effects as characters of late. They were, to put it mildly, some of the worst CGI characters in any of the large budget, high profile film releases of the '00s. There, I said it. The final insult on top of injury, however, with I Am Legend was the use of an ending (be it the one in the theatrical cut or the alternate ending included on the DVD release) that seemed to be the antithesis of the novel's. And unfortunately, the film made a ton of money at the box office. So much so, the studio at one time was preparing for something that should have been abhorrent to anyone who appreciated the original book: a prequel. Luckily, if it's to be believed, that project is dead.

(and Will was hard pressed to garner more acting praise than her). For the record, Ms. Braga does indeed look better than the dog, but Sam simply acted better. Unfortunately, the film overemphasized its special effects and action over the original story's tenets. Plus, this one was a prime example of the filmmakers' tendency to overuse computer effects as characters of late. They were, to put it mildly, some of the worst CGI characters in any of the large budget, high profile film releases of the '00s. There, I said it. The final insult on top of injury, however, with I Am Legend was the use of an ending (be it the one in the theatrical cut or the alternate ending included on the DVD release) that seemed to be the antithesis of the novel's. And unfortunately, the film made a ton of money at the box office. So much so, the studio at one time was preparing for something that should have been abhorrent to anyone who appreciated the original book: a prequel. Luckily, if it's to be believed, that project is dead.Note: I Am Omega was a direct-to-video release that also came out in 2007 and has yet to be screened by me. Perhaps, one day…

Also in 2007 (in conjunction with the late year release of the above film), the original novel was re-issued (yet again) by a book publisher. And for the first time, Blackstone Audio published an unabridged audiobook for the legendary work. The high profile nature of the then upcoming film, and the importance of bringing a trailblazing novel to the spoken word form, necessitated the studio managers bring out one of its big guns for this first audio treatment. Narrator Robertson Dean, he of the "sonorous, classically disciplined bass-baritone" voice, was selected as the reader. As one of my 2008 reads/listens, all I can say is it was one of the best audiobooks I heard that year. His superlative reading gave a voice to that of the character of Robert Neville I hadn't imagined. And since it all came from the original novel by author Richard Matheson, without abridgement or adaptation, I'd recommend it hands down to anyone who wishes to visit his renowned story. And perhaps, this would include any of the aforementioned film versions (though the earliest of these are worth screening).

The I Am Legend novel remains a masterpiece of modern fiction by one of the true pioneers of books, television and film. Richard Matheson wrote novels of mystery, science fiction, horror, fantasy and, believe it or not, Westerns. Name a writer's award, and he's probably won it (the Hugo, Edgar Allen Poe, Golden Spur, and the Writer's Guild awards to name a few). And if I were to pick just one of his works to be emblematic of his skill and genius at writing, I don't think I could do better than naming this novel to represent that. It's a pity, but not too much of a shock, that the film treatments of the work don't really come close to the pages laid down more than half a century ago. And since I can't do better than that, I'll let the novel's final words close this out:

"Robert Neville looked out over the new people of the earth. He knew he did not belong to them; he knew that, like the vampires, he was anathema and black terror to be destroyed. And, abruptly, the concept came, amusing to him even in his pain.

A coughing chuckle filled his throat. He turned and leaned against the wall while he swallowed the pills. Full circle, he thought while the final lethargy crept into his limbs. Full circle. A new terror born in death, a new superstition entering the unassailable fortress of forever.

I am legend."

Tweet

Labels: 00s, 60s, 70s, Books, Fiction, Heston, Vincent Price, W. Smith

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

The twilight of an extraordinary life

By Edward Copeland

When Charles Nelson Reilly died in 2007, the percentage of people who knew who he was by name, unfortunately, already had fallen precipitously. Thankfully, in the final years of his life the theater actor turned game show fixture had developed and toured in a solo show about his life called Save It for the Stage. Even though Reilly had stopped touring with the show, The Life of Reilly's co-directors Frank L. Anderson and Barry Polterman talked him into performing it one more time in October 2004 so they could film it. As a result, they made this film record of Reilly's remarkable story as only he could tell it.

As title cards explain at the film's opening, the solo show evolved from a talk Reilly was asked to give in 1999. He didn't have anything planned and spoke extemporaneously for more than three hours, enjoying the hell out of it. After that experience, he worked with actor Paul Linke to pare down the show into a more compact running time and Save It for the Stage was born.

While the version of the solo show captured in The Life of Reilly runs half the time that original three-hour speech did, I imagine Reilly would hold your interest at the longer running time based on the nonstop cyclone

of energy he becomes as he shares an oral autobiography, beginning with his birth on Jan. 13, 1931, in The Bronx, and the difficulties growing up with his eccentric family, particularly his bigoted mother who was prone to say things such as "I should have thrown away the baby and kept the afterbirth." (She gave the stage show its name because any time young Charles would go on about something, she'd tell him to "Save it for the stage.") He was more enamored with his father who was a commercial artist, drawing beautiful color advertisements. Young Charles struggled in school, not realizing that his problem was his eyesight, not his intelligence, but he always was imaginative from an early age. A particularly poignant portion of the film comes when he describes his mom taking him to his first movie at the Loews Paradise and how he felt "so safe and warm" sitting there in the dark, gazing at those images.

of energy he becomes as he shares an oral autobiography, beginning with his birth on Jan. 13, 1931, in The Bronx, and the difficulties growing up with his eccentric family, particularly his bigoted mother who was prone to say things such as "I should have thrown away the baby and kept the afterbirth." (She gave the stage show its name because any time young Charles would go on about something, she'd tell him to "Save it for the stage.") He was more enamored with his father who was a commercial artist, drawing beautiful color advertisements. Young Charles struggled in school, not realizing that his problem was his eyesight, not his intelligence, but he always was imaginative from an early age. A particularly poignant portion of the film comes when he describes his mom taking him to his first movie at the Loews Paradise and how he felt "so safe and warm" sitting there in the dark, gazing at those images.Reilly's first taste of acting came in fourth grade when his teacher offered young Charles the role of Columbus in a class play. His mother was resistant, saying he'd never learn the lines because of his difficulties (still denying that eyesight was the problem) but the teacher talked her into it and his acting career was born in P.S. 53. Around the same time young Mr. Reilly received an opportunity, the elder Mr. Reilly missed a big one.

An artist who worked in black and white fell in love with his father's color artwork and urged him to go to California with him, but Reilly's mother nixed the move because all her relatives were on the East Coast. The man's name was Walt Disney. Soon, advertising turned more to photographs than illustrations and Reilly's father was thrown out of work and into alcoholism and eventually institutionalized, forcing young Charles and his mother to move to Hanover, Conn., to live with his uncle, aunt and grandparents, Swedish immigrants who spoke no English. Eventually, his father rejoined them and his aunt, who had her own problems, agreed to try a new medical procedure: a lobotomy. Though Reilly never dwells on his homosexuality, he tells how the neighbors to that household said that he was a "little odd."

"How do you think I felt being the odd one in that family?" he asks, adding that Eugene O'Neill wouldn't come near that house and that he spent his adolescence in an Ingmar Bergman film. However, he reminds his audience what Mark Twain said about laughter being the same in every language. Reilly's ability to tell these stories, some of them horrifying, and still be able to wring laughs from theatergoers was a great gift indeed and as he set out to act for a living in 1950, his tales of theater and show business prove even more entertaining.

A particularly astounding portion is when he discusses the acting class he attended taught by Uta Hagen at HB Studio, the school she founded with her husband Herbert Berghof. The cost was $3 a week. He reads the roll of his 11 a.m. Tuesday class and it's amazing because every name would achieve success, fame and accolades. Here is the list, minus Reilly, alphabetically:

As Reilly tells it, they all had three things in common: "We wanted to be on stage, none of us had any money and we COULDN'T ACT FOR SHIT!" Reilly adds that if they saw McQueen and Holbrook act out a scene as Biff and Happy Loman from Death of a Salesman one more time, "You'd go out of your fucking mind." He does make the point that people who wanted to act back then actually studied, something not as common as it used to be. By my count, this class (to date) has earned nine Tony Awards out of 30 nominations (11 out of 32 if you toss in Uta Hagen's two wins), six Oscars out of 16 nominations and 11 Emmys out of a whopping 61 nominations. Charles Nelson Reilly himself accounts for a Tony for featured actor in a musical as Bud Frump in the original production of Frank Loesser's How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, a nomination as Cornelius in the original Hello, Dolly! and a nomination for directing the revival of The Gin Game that starred Julie Harris and Charles Durning. Reilly earned three Emmy nominations: for The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, a guest shot on The Drew Carey Show and for reprising the Jose Chung character he created on The X-Files on an episode of Millennium.

As with all struggling actors in New York since the beginning of time, Reilly needed work to pay the bills until he started landing paying parts in production. He was excited when a female friend who worked at NBC got him a meeting with the possibility of on-air work. Reilly arrived and met Vincent J. Donahue, the NBC chief at the time, who dismissively sent him away telling him, "We don't put queers on television." Reilly admits that as hateful as that comment was, it rolled off his back. Words like that didn't bother him as much as coming home to find roaches in his Minute Rice. Though he eventually became somewhat of a gay icon, none of the autobiographical show deals with the difficulties of being a gay actor except for that anecdote and there is no mention of a romantic life. Reilly considered himself an actor first — his sexual orientation was just another aspect his life, just like his bad eyesight. Both were parts of him, but neither defined him.

Reilly lived and breathed theater and that is what he wanted to share with the audiences who came to his shows — the upbringing that got him to that point and how it always was an integral part of his life, even after he became better known for kids' TV shows and Match Game. In 1954, he appeared in 22 off-Broadway shows. His Broadway debut came, ironically, as an understudy for another actor who became a gay icon and game show staple — Paul Lynde. Lynde had to be out of Bye Bye Birdie every Thursday night because of a contract to appear on The Perry Como Show, so Reilly took his place once a week. Eventually, he also got to be Dick Van Dyke's understudy in the musical.

He discusses how his close friendship with Burt Reynolds began in New York when Reynolds was a struggling actor and then decades later, when Reynolds built his theater in Jupiter, Fla., he attached an acting school and gave Reilly a beach house to live in so he would teach.

He talks about his times in Hollywood, especially how much he enjoyed being on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson where he was a guest more than 100 times. He talks about one particular time when another guest was a woman who ran a Shakespeare in the Park program in Ohio and he said something and she responded, quite snootily, "What would someone like you know about Shakespeare?" Then he showed her.

Before he taught in Florida, he would teach acting back at that old HB Studio and in a story that particularly cracked me up because it reminded me of my days of both attending and judging high school drama contests almost 25 years ago now, he says, "If I saw one more Agnes of God…" If you've experienced high school drama contests since that play was written, you know exactly what he means (and I'd toss in 'night, Mother as well).

Reilly talks and talks and talks and you're never bored. You're usually laughing, but sometimes, as when he describes being present at 13 at an infamous Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus fire that claimed many lives, including that of one of his childhood friends, you're mesmerized. The Life of Reilly truly captivates. The biggest barrier to enjoying it is finding a way to see it. It's on streaming at Netflix but not DVD, so watch it there before you cancel and go back to DVD only. Neither GreenCine nor Blockbuster carries it on DVD or On Demand. Redbox doesn't carry it. Hulu Plus doesn't stream it. Amazon Instant Video DOES have it for $2.99, though you could buy it for $9.99. Best Buy CinemaNow doesn't have it for streaming. Comcast XfinityTV ON Demand doesn't have it either.

It's a miracle that Netflix's streaming has it right now because eventually, it won't as smaller, wonderful titles such as The Life of Reilly that are a whole FOUR years old and are perceived as having too small a niche audience disappear entirely from home rental availability. It's a shame because it means the number of people who remember Charles Nelson Reilly will decline more rapidly than it is declining already.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Awards, Burt Reynolds, Carson, Disney, Documentary, Durning, Frank Loesser, Geraldine Page, Grodin, Holbrook, Ingmar Bergman, Lemmon, Musicals, O'Neill, Oscars, Robards, Shakespeare, Television, Twain

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

Cinematic Grace

By J.D.

Decades in the making, the gestation period of Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011) is as epic as the film itself. After Days of Heaven (1978) was released to critical acclaim and nominated for four Academy Awards, Paramount, the studio that backed it, offered the director $1 million dollars for his next project, regardless of its subject matter. Despite being burnt out from making and editing Days, he agreed. Malick had been contemplating his most ambitious film yet: the creation of our galaxy and the Earth as well as the beginnings of life. It was originally called Qasida (a reference to an ancient Arabian form of rhythmic lyric poetry) and eventually shortened to Q. In 1979, Malick and a small crew began shooting footage in exotic locales all over the world. The footage they were getting looked great but Paramount was nervous about the absence of a screenplay (Malick would write 40-page poetic descriptions of the imagery) and a structured shooting schedule. Eventually, the studio lost patience with the director’s methods and he not only quit the project but the movie business for 20 years.

The first signs that Malick was returning to his Q project came during pre-production on The New World (2005) when producer Sarah Green received a revised treatment for what would become The Tree of Life. By July 2007, there was a script that fused the cosmic nature of Q with a semi-autobiographical story that focused on a Texas family in the 1950s as seen through the eyes of the oldest child Jack (Hunter McCracken as a child and Sean Penn as an adult). As early as Days of Heaven, Malick had been moving away from linear narratives to a more philosophical tone poem approach. With The Thin Red Line (1998), he began to explore in greater detail man’s relationship with his environment and with the Earth. This continued with The New World, which embraced a nonlinear narrative more than anything he had done before. The Tree of Life is the culmination of Malick’s body of work so far.

The film begins with the death of one of the O’Brien children. The mother (Jessica Chastain) is understandably devastated while the father (Brad Pitt) is stoic but eventually the cracks begin to show and he also grieves in his own way. Cut to the present day and Jack O’Brien (Sean Penn) is an architect, unhappy and adrift in the world, still haunted by the death of his brother. The film flashes back to his reminisces of his childhood in the ‘50s. In this first section, Malick cuts back and forth between the impersonal concrete and glass jungle of the big city in which Jack works and the idyllic suburban neighborhood of his youth.

Early on in the film, the mother says in a disembodied voiceover, “There are two ways through life: the way of nature, and the way of Grace. You have to choose which one you'll follow. Grace doesn't try to please itself. Accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked. Accepts insults and injuries. Nature only wants to please itself. Get others to please it too. Likes to lord it over them. To have its own way. It finds reasons to be unhappy when all the world is shining around it. And love is smiling through all things.” I believe that this passage is integral to understanding Malick’s film and it becomes apparent that the mother represents Grace, accepting insults and injuries, while the father represents nature, lording over his family.

Right from the get-go, Malick dispenses with the traditional notion of how a scene is structured and linked to another in favor of an impressionistic approach. This is no more apparent than when the narrative segues to an extraordinary sequence depicting the creation of our galaxy and the Earth with absolutely breathtaking imagery — a stunning mix of unusual practical effects (created by Dan Glass and the legendary Douglas Trumbull) and actual footage courtesy of NASA. With this sequence we are entering Stanley Kubrick territory. Like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Malick mixes science with spirituality, the cosmic and the ethereal, occasionally commented on via existential voiceover musings about God by the mother. He actually shows the Earth forming and early life being created on the most basic cellular level on up to the dinosaurs. This sequence and its placement so early on in the film is just one of the audacious choices Malick makes.

The film then goes back to early stages of the O’Brien family, to the creation of their children, the painful and glorious experience of childbirth, much like that of the Earth itself. Malick presents two approaches to parenting: the mother is a nurturing figure while the father is a stern disciplinarian. She is in tune with nature while he represents structure. It is this part of the film that is the most engaging as we are presented with familiar, relatable imagery: a very young boy gazes in wonderment and then jealousy at his baby sibling; the shadows of tree branches playing across a wall; the family playing with sparklers at night; kids playing in tall grass; and a tree-lined suburb at dusk with the sky the most amazing shade of purple-blue. These are the innocent, carefree days when you had no worries and would spend hours playing with other children until called in by your mother for the night. Malick has come full circle by returning to the same tranquil Texas suburbs first glimpsed at the beginning of Badlands (1973), his debut feature. These scenes will be instantly familiar to anyone who grew up in the suburbs or a rural environment.

As he did with Linda Manz in Days of Heaven, Malick demonstrates an incredible affinity for working with children and pulling naturalistic performances out of them. All of the kids, especially newcomer Hunter McCracken, act very comfortable in front of the camera, almost as if Malick caught them unaware that they were being filmed. McCracken has a very expressive face, which he utilizes well over the course of the film as Jack becomes increasingly rebellious, testing the rules imposed by his father. Malick documents the children’s behavior and all of their idiosyncrasies, like how they interact with each other and how this differs with their interaction with adults, especially in the ‘50s when they were much more respectful. Much of the film is seen from a child’s point-of-view with low angle shots that look up at adults, trees, and so on. It’s only in the scenes with other children that the camera takes a more level position.

At one point, the father tells Jack that his mother is naive and that “It takes fierce will to get ahead in this world.” Brad Pitt doesn’t play the stereotypical strict father figure but one with layers that are gradually revealed through the course of the film. He works in a factory, a labyrinthine maze of metal machinery but we learn that he wanted to originally be a musician but it didn’t work out. He had to become responsible and lead a more traditional life in order to provide for his family. He still plays piano and passes this ability on to his children. Pitt delivers an excellent performance that grounds the film. The actor has aged well and grown into his looks, relying less and less on them as he gets older. There is a nice scene where he accompanies one of his sons playing an acoustic guitar with the piano that is brief but does a lot to humanize his character. The mother, in comparison, is a more elusive character, more of an ethereal figure as played by Jessica Chastain.

You simply cannot engage The Tree of Life in a traditional way. The first section is a little impenetrable at first as one has to leave the concept of traditional narrative behind and get acclimatized to Malick’s approach. One has to let it wash over you and let his poetic imagery work its magic. Like all of his films, this is one that people will either passionately love or hate because of its ambitious, unusual approach. It will be seen as pretentious by some but any film that strives to tackle big themes like life and death and what it means to be human on such an epic (and also intimate) scale runs that risk. What prevents it from collapsing under its own thematic weight is Malick’s sincerity. He really believes in what he is showing us and treats it with the solemnity and weight it deserves. The Tree of Life has the kind of lofty ambitions most films only dream of reaching and it is easy to see why it is being compared to 2001. Like that film, Malick’s will undoubtedly reveal more upon repeated viewings. There is just so much to absorb that one viewing is not enough because you are too busy trying to make sense of what all this breathtaking imagery means. It will take repeated viewings to fully appreciate what Malick is trying to do and say. This is an important film by a master filmmaker.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Brad Pitt, Malick, Oscars, Sean Penn

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

South Korean Twists on American Genres

By Kevin J. Olson

For my money, some of the best films being released today are those coming out of South Korea. And one of the very best at making those films is Kim Jee-woon. Whether it’s the ghost Story (A Tale of Two Sisters), the mob flick (A Bittersweet Life) or the adventure picture (The Good, the Bad, and the Weird), Kim always is taking clichés from American genre pictures and making them more interesting than they have any right to be. With his A Tale of Two Sisters (one of my favorite films of the past decade), he turned an average ghost tale into a poignant story about sisterhood, memories and things lost. It was deeper and more heartfelt than it had any right to be. Not to mention the thing looked really damn good. Then there was his war picture, The Good, the Bad, and the Weird, which again took all of the clichés we Americans come to expect in an action/adventure picture and puts his twist on them so that without realizing it we’re giving ourselves completely over to the material despite being so familiar with the beats. It is this visceral energy and the fact that there’s always something deeper beneath the familiar surface of Kim’s films that makes them so engrossing.

I Saw the Devil is a slasher film, a torture film, a revenge picture and a serial killer procedural, and yet all of those labels don’t do the film justice at all. It brings together extreme violence with Lynchian humor. There’s a detour to a cannibal’s house that takes the film from slasher film/Silence of the Lambs-like serial killer picture to absurd comedy (it reminded me of another South Korean horror film in this regard, 2009’s Thirst, and somehow finds room for genuine emotion and, in typical Kim fashion, a poignant ending. It’s also one of the best films of 2011.

The film deals with Soo-hyun (Kim stalwart Lee Byung-hun, who is brilliantly stoic and vulnerable when he needs to be) a secret service agent that goes on a personal manhunt to find the man responsible for murdering his wife. Sounds simple enough, right? Kim however puts an interesting spin on this very basic tale as Soo-hyun quickly disposes of the suspects who turn out not to be the person he’s looking for. But then one night Soo-hyun can’t sleep, and he decides to go after his next suspect who turns out to be Kyung-chul (Choi Min-sik of Oldboy fame, who plays crazy and nihilistic better than anyone I’ve seen in a long time), the man responsible for murdering his wife. Oh, and he’s a cannibal to boot. I dare not reveal any more of the revenge tale because half the fun is seeing the how the cat-and-mouse game between the two unfolds as the seemingly normal agent Soo-hyun relentlessly tracks down the batshit insane cannibal Kyung-chul like he’s Yul Brynner from Westworld.

Everything aesthetically is top-notch in I Saw the Devil: The music by Mowg is operatic and fantastic during the montage scenes and low-key during the cerebral moments of the film; the framing and use of silhouette; the use of sound and silence in the film (just as he did in A Tale of Two Sisters works extremely well at creating an unnerving atmosphere; and Lee-Mo-gae’s cinematography is beautiful and has a nice sheen to it in both the big city scenes (such as Soo-hyun’s apartment at night or the final chase near the end) and in the rustic scenes where the film gets gory and unflinching and grimy in Kyung-chul’s barn (seriously, just watch one second of I Saw the Devil, and you’ll see why American horror directors can't even come close to framing a horror/torture scene the way Kim does).

The film, at 140 minutes, may overstay its welcome a tad, but it’s nothing that ever caused me to check the time and feel bored by what I was watching, and by the end I hadn’t even realized how long the film was. I got lost in this gruesome revenge tale, and by the end I was so invested that I found myself really affected by the final tete-a-tete between Soo-hyun and Kyung-chul. Like the end of A Tale of Two Sisters, Kim ends his film again with a tracking shot of the main character walking away from the scene as minimalist music plays in the background and the slow realization of the weight of everything that’s happened and the revelations that have been made finally pour over the characters. Here is Soo-hyun’s demons being exorcised and we’re not quite sure if he’s relieved because the ordeal is over and he indeed has taken and eye-for-an-eye, or if he’s horrified at the person he’s become. It’s a powerful moment that Kim wisely keeps minimalist as he ends his film, again like A Tale of Two Sisters, on a somber, contemplative note.

I Saw the Devil is easily one of Kim’s best films. It’s an unflinching and nasty genre picture at times (some of the revenge tale reminds me of a grindhouse movie) and a genuine, emotionally charged film in between the bloodshed (and man is there a lot of blood). The juxtaposition of viscera and poignancy (again, the end is brilliant in how it places the heartfelt tete-a-tete in the Grand Guignol setting) is one of the things that stand out in all of Kim’s films; it makes them more memorable, more lasting, than their basic genre components suggest they have any right to be. This is not a film for everyone, but if you can stomach the violence, you’ll find a film with a lot of humor and heart buried beneath its bloody surface.

Tweet

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, June 02, 2011

Schrader's return to safer ground

By J.D.

After dabbling briefly with a major studio on the debacle that became known as Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist (2005), writer/director Paul Schrader returned to the relatively safe confines of the independent film scene with The Walker (2007). This film continues his fascination with loner protagonists ostracized by their profession as examined in American Gigolo (1980) and Light Sleeper (1992), or by their worldview as in Taxi Driver (1976).

Carter Page III (Woody Harrelson) is a popular socialite who works as a confidant, companion, and card player to the wives of politicians in Washington — a professional “walker,” a term coined for Nancy Reagan’s companion when she was First Lady. Carter is the epitome of the Southern gentleman. He plays a weekly card game with three women as they gossip and tell stories complete with salacious details about the denizens of Capitol Hill. Carter is finely groomed and impeccably dressed with only the finest suits, living in a beautifully furnished place.

With the stories Carter tells his dates, he hints at a rich backstory but he is careful not to reveal too much about himself. While waiting for Lynn Lockner (Kristin Scott Thomas), one of his dates, to meet up with her lover, she comes back in shock. Her lover is dead and she asks Carter to keep the incident quiet. Of course, he decides to get involved (he knew the victim). Carter used to trade in juicy gossip and now he has become the subject of it.

It doesn’t help that he lost considerable money on an investment that the victim advised and this gives the socialite a motive. As a result, he decides to investigate the murder using his own insider contacts and uncover a few dirty secrets that people in positions of power don’t want revealed. His efforts to clear his name become more urgent once the Feds apply pressure thanks to a particular nasty agent (William Hope). Pretty soon, events conspire against him and Carter becomes the prime suspect.

Woody Harrelson disappears into the role affecting a flawless accent and does an excellent job with Schrader’s witty dialogue and distinctive cadence. Every few years between amiable comedies Harrelson gets a juicy dramatic role to sink his teeth into and showcase his acting chops: Natural Born Killers (1994), The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996), and now this film. Schrader’s screenplay, as you would expect, snaps and pops, especially the scenes where Carter and his companions banter and gossip. It doesn’t hurt that he has the likes of Lauren Bacall, Lily Tomlin and Kristin Scott Thomas delivering it.

The Walker is a fascinating inside look at a subculture that exists in Washington under the auspices of a murder mystery. It shows to what lengths politicians will go in order to protect themselves and their dirty secrets. Schrader has crafted a smart thriller with interesting characters that is driven by a well-plotted story and not a bunch of noisy, hastily edited action sequences.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Bacall, Harrelson, Kristin Scott Thomas, Lily Tomlin, Schrader

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Harry Potter and the Deadly Huhs?, Part I

By Edward Copeland

When this blog first began (actually before it began, when I would just jot short movie musings on my long defunct political blog the Copeland Institute for Lower Learning), one of the first films I wrote about was Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire under the title "Harry Potter and the Defiance of Sequel Expectations." It could hardly be called a review, as short as it was, but one thing I wrote was "How is it that a film series can keep getting better as it goes on instead of worse?" I fear I jinxed it with those words about the fourth in the series, because the fifth slipped just a bit, while the sixth installment flummoxed this viewer who'd never read a word of any of J.K. Rowlings' books. Now, I've caught up with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part I and it seemed to me as if I'd walked into a four-hour movie after missing the first two hours. It's a tiring befuddlement missing any sense of fun, suspense of consequence or, most importantly considering its realm, magic.

One thing that's interesting in Deathly Hallows — but just briefly — is seeing Harry, Hermione and Ron (Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson and Rupert Grint) running around London for a change instead of their usual Hogwarts haunts. It did again raise the question I've always had throughout the series: If these kids head off to this wizardry school to matriculate their magical skills, but they aren't supposed to practice their powers back among the muggles, what exactly is the point once they graduate? Do they automatically get stuck in careers as teachers of future young wizards? I take it none of them head back to the regular world and embark on normal careers and retire their wands. (As an aside, Hogwarts always has professors for subjects such as Defense Against the Dark Arts, but does anyone there bother to teach the students math, English or science?)

Anyway, Hogwarts isn't part of the equation in Deathly Hallows anyway. It seems to concern "the ministry" which I'm guessing is the Harry Potter equivalent of Buffy Summers' Watchers' Council and that evil Lord Voldemort, the blank-faced bad guy with some sort of shared memories with Harry (who is supposed to be Ralph Fiennes, hidden somewhere beneath that pasty, featureless makeup) has destroyed it much as The Council got itself blown up. At least I think that's what Bill Nighy's character, dressed as if he accidentally got teleported to the set from a production of Arthur Miller's The Crucible, tells us.

Most of the adult characters are absent or make just cursory appearances here. There's very little of Alan Rickman's Professor Snape and a nice but all-too-brief appearance by Brendan Gleeson's Mad-Eye Moody. I do admit I did get excited when Imelda Staunton reappeared as Dolores Umbridge, since I believe her performance in Order of the Phoenix remains the best given by any actor in the entire series and an argument could have been seriously made for nominating her for supporting actress. Unfortunately, we get a bit of Dolores' little giggle and then she's gone again.

Of course, the sequence she appears in lacks the coherence that most of this overlong and tedious film does. Near the beginning, the good guys, worried about keeping Harry's location secret from Voldemort, take time out to attend a wedding but for the life of me, I can't tell you who the hell was getting married or why it should have mattered.

I don't know why the producers of the series have remained glued to director David Yates. Once Chris Columbus thankfully exited after the first two bland installments, that's when the series started getting better, first with Alfonso Cuaron and then with Mike Newell. They turned to Yates starting with Order of the Phoenix, which Staunton basically saved, but that film overall and two since have taken the series into a downhill spiral instead of up toward a rousing conclusion.

Many years ago, a bunch of my friends and I went out to see David Lynch's film of Frank Herbert's Dune the weekend it opened. As with the Harry Potter books, I'd never read any of the Dune books either. I knew I was in trouble when at the theater they handed each ticketholder a sheet with a long list of definitions for terms that would be used in the movie. What was I supposed to have done — bring along a flashlight so I could look things up as the movie played in case I got confused or lost?

I saw Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part I at home on DVD. I sort of wish it had come with one of those lists to help me understand what the hell was going on. Then again, a good movie doesn't require supplements to explain itself. If it's any good, the film stands on its own and speaks for itself.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Arthur Miller, Books, Fiction, Lynch, Ralph Fiennes, Rickman, Sequels

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, May 23, 2011

Always a Bridesmaid

By David Gaffen

The new film Bridesmaids has been saddled with the unfortunate assignment of proving a movie centered largely around women can be funny, attract audiences across all ages and (more importantly) of both genders, and bring copious amounts of sexual and scatological humor, only this time, with girls!

The results are uneven — there are a number of huge laughs, notably in the scene where several of the bridesmaids-to-be erupt in a fit of vomit and diarrhea at a wedding dress fitting caused by food poisoning at an out-of-the-way Brazilian restaurant. (The movie takes place in Milwaukee, for some reason.)

It gets good mileage out of Kristin Wiig and Maya Rudolph, both from Saturday Night Live, as longtime friends who don't see each other as much as they used to, something that comes through after Rudolph's Lillian asks Wiig's Annie to be her maid of honor. This aspect of the story is mined well, along with some of the class resentments that seep through as Wiig grows jealous of her competition, Helen, played by Rose Byrne, who is swimming in money and isn't shy about showing it.

But what's worth considering is that this movie — which fits neatly in the group of so called "Frat Pack" movies that generally feature some combination of Will Ferrell, Seth Rogen, Paul Rudd, Jonah Hill, Adam Sandler, Vince Vaughn and a few others — is, like those movies, only partially successful and should cause us to remove the rose-colored glasses that tint our memories of the likes of Old School, Anchorman and other movies in this genre.

Judd Apatow (who produced Bridesmaids) is rightfully thought of as being at the center of a lot of these films, although his movies generally have more heart than some of the others in this group, and this movie — though over the top at times — shares some of those characteristics. It falls short of The 40-Year-Old Virgin, one of the best comedies (or movies) of the last 10 years, but slots in ahead of any of the other "Look at this wacky ensemble" movies such as Dodgeball, Wedding Crashers or Pineapple Express.

Those movies have grown in reputation over time, in part because of amusing set pieces and memorable moments. But most of the movies in this roughly 10-year time period were mediocre entertainment, enlivened by those few fantastic bits (the opening of Wedding Crashers, the climactic battle in Role Models) and weighted down with a lot of ballast — with enough juicy supporting turns to keep things interesting (Tim Meadows in Walk Hard, Jane Lynch in 40-Year-Old Virgin and, well, about everywhere else she showed up).

Which doesn't make Bridesmaids anything better or worse than this genre which it fits comfortably in. Wiig's Annie is in a bad place in life, and it keeps getting worse, and that aspect of the script is refreshing. She and the other women — particularly Melissa McCarthy, who serves the Zach Galifinakas/Stephen Root role of the hefty sidekick, but gets a few soulful moments that ground the movie — are given room to shine with gross-out material usually easily handled by men

But it has its problems. Goofy side plots, such as Wiig's British roommates, and her mother's (the late Jill Clayburgh in her final film role) penchant for attending AA meetings despite not being an addict, feel unfocused. That the movie seems on its way to making a nice chunk of change (it grossed $24 million in its first weekend, putting it on the path for about $60 million unless word of mouth pushes it further) is a testament to the pedigree of the producers involved and the marketing campaign as much as it is the script, which is good, but not great.

It's progress of a sort, one supposes — this isn't Sex and the City 2 — but it will take a few more movies in this vein before this appears to be a novelty.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Apatow, Jonah Hill, Paul Rudd, Seth Rogen

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, May 20, 2011

The sun may not come out tomorrow

By J.D.

In some respects, Danny Boyle is Britain’s answer to Steven Soderbergh — a filmmaker who moves effortlessly from independent to studio films and works in a variety of genres: gritty drug drama (Trainspotting), kids film (Millions) and edgy horror (28 Days Later). Like Soderbergh’s Solaris (2002), Boyle has tried his hand at science fiction with Sunshine (2007). It was critically lauded in England as a thinking person’s genre film but was met with mixed critical reaction in North America and lackluster box office.

Sometime in the far future, our Sun is dying. The Earth is in the grips of a solar winter and the only chance we have for survival is to reignite the star. A spacecraft called the Icarus II, with a crew of eight and carrying a nuclear bomb roughly the size of Manhattan, will hopefully kick-start the Sun and save humanity.

On the way there, they pick up a distress beacon from Icarus I, an earlier expedition with the same mission but that had mysteriously disappeared en route. Do they alter their course and check out the ship in the hopes that they can use its bomb and thereby doubling their chances? The decision lies with the ship’s physicist, Dr. Robert Capa (Cillian Murphy) and it is one that will affect the entire crew in ways they can’t yet imagine.

Through a series of intense situations brought on by unforeseen complications, there’s a real possibility that the Icarus II may not make it back alive and the characters have to realistically deal with this chilling realization.

Sunshine starts off as an intellectual science fiction film a la 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and then shifts focus to an engrossing mystery involving the Icarus I and shifts again to a slasher film reminiscent of Event Horizon (1997) for the last third. This last shift has drawn the most criticism from reviewers and does test the film’s credibility. Do the filmmakers really need to add even more danger for the protagonists to face? Isn’t the fact that they are heading straight toward the Sun with limited resources and crew challenging enough?

Sunshine does an excellent job showing the dynamic between the crew members and how it gradually breaks down when things go horribly wrong. They end up turning on each other and an oversight or miscalculation has catastrophic effects. The cast is uniformly excellent and refreshingly absent of big name movie stars. Instead, we get solid characters actors such as Cillian Murphy (The Wind That Shakes the Barley), Rose Byrne (28 Weeks Later), Michelle Yeoh (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) and Cliff Curtis (Bringing Out the Dead). Some of them are cast wonderfully against type and others, such as Chris Evans (Fantastic Four), show previously unseen depth.

It is also nice to see the characters solving problems with reason and intellect that actually makes sense. That’s not to say that Sunshine is all brainy posturing. There is plenty of intense, visceral action that is

emotionally draining much as Boyle did with 28 Days Later (2002). As he showed with that film and his debut, Shallow Grave (1994), he certainly knows how to ratchet up the tension. This also is a visually impressive film as Boyle not only shows off the usual iconography of the genre — spacecraft, spacesuits, etc. — but doesn’t fall into some of the more tired clichés, like aerodynamically-designed spacecraft and evil computers. He also doesn’t telegraph who lives and who dies which gives the film an edgy unpredictability. At times, it feels like Sunshine wants to be the 2001 for the new millennium but then the slasher film elements creep in and it resembles a more traditional thriller. It’s too bad because up to that point, Boyle’s film is a very smart, thought-provoking piece of speculative fiction.

emotionally draining much as Boyle did with 28 Days Later (2002). As he showed with that film and his debut, Shallow Grave (1994), he certainly knows how to ratchet up the tension. This also is a visually impressive film as Boyle not only shows off the usual iconography of the genre — spacecraft, spacesuits, etc. — but doesn’t fall into some of the more tired clichés, like aerodynamically-designed spacecraft and evil computers. He also doesn’t telegraph who lives and who dies which gives the film an edgy unpredictability. At times, it feels like Sunshine wants to be the 2001 for the new millennium but then the slasher film elements creep in and it resembles a more traditional thriller. It’s too bad because up to that point, Boyle’s film is a very smart, thought-provoking piece of speculative fiction.Tweet

Labels: 00s, Danny Boyle, Soderbergh

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, March 08, 2011

Fight Fiercely, Harvard

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

The subject of the most engaging documentaries I’ve watched recently…is a football game. Organized (and for that matter, unorganized) sports isn’t really a passion of mine — football, basketball, hockey, etc., I don’t have much use for that kind of gamesmanship; though I do make an exception in the case of baseball (there’s just something about “America’s national pastime” that stirs my sports-cynical heart). So I was genuinely surprised when I found my spirits lifted by director Kevin Rafferty’s Harvard Beats Yale 29-29 (2008), which chronicles one of the most phenomenal gridiron contests in Ivy League history. But even as many of the former players who participated acknowledge in the end that “it’s just a football game” you’ve no doubt probably guessed by now…the film is a little bit more than that.

For many, Nov. 23, 1968 was just another “Football Saturday” but for longtime Ivy League rivals Harvard and Yale, “The Game” that afternoon at Harvard Stadium was shaping up to be a real contest. Both schools were undefeated at the time of the final game of the season, the first time such an event had occurred since 1909. As to who would dominate the proceedings…the smart money was on the Bulldogs; ranked 16th and featuring the double-threat combination of senior quarterback Brian Dowling (a superb athlete who had never played in a losing football game since seventh grade) and halfback Calvin Hill, the No. 1 draft pick of the Dallas Cowboys. The scrappy Harvard team was being beat like a rented mule by their Yale competitors, trailing 22-0 near the end of the second quarter until Harvard coach John Yovicsin decided that quarterback George Lalich wasn’t getting the job done and replaced him with backup QB Frank Champi. Things improved only slightly for Team Crimson as they ended the half with a score of 22-6.

By the start of the third quarter, it looked as if it was all over but the crying for Harvard as the Bulldogs continued to dominate, leading 29-13 with only two minutes left in the game. What happened after that — described by one Yale player as “a slow-motion nightmare” — was a comedy of errors that allowed the Crimson to end up tying a game they had been expected to lose and provided both the Yale players and their supporters a textbook example of hubris, demonstrating that if a Supreme Being does exist s/he has one hell of a sense of humor.

The outcome of what many have called “the most famous game in Ivy League history” is never in doubt — the title of the documentary (inspired by a headline in the Harvard Crimson) is a giveaway for anyone not familiar with the events recorded in the film. But the genius of Rafferty’s documentary is that Harvard Beats Yale 29-29 makes the game’s foregone conclusion surprisingly nail-bitingly suspenseful and unabashedly entertaining; intercutting video of the 1968 match-up (with play-by-play by sportscasting veteran Don Gillis) with interviews from nearly fifty of the surviving players on both teams. Spending an hour and forty-five minutes listening to athletes ruminate about a long-forgotten football game wouldn’t be my ideal way of spending an evening, but the individuals interviewed in the movie are funny, engaging and charmingly philosophical about a contest that for many defined their collegiate experience and shaped their various worldviews of life beyond graduation.

The most famous face among the football players in Harvard Beats Yale undoubtedly belongs to Oscar-winning actor Tommy Lee Jones, a Crimson guard who demonstrates that adorable unflappability on camera (“I

remember telling myself to stay cool and be smooth”) with wry observations about the game…and about his equally famous college roommate, former Vice President Al Gore — who Jones recalls learned to play “Dixie” on their touch-tone phone (which were just replacing rotary-dial phones at that time) and once helped him prepare a Thanksgiving turkey in a fireplace. Gore’s GOP nemesis in 2000, President George W. Bush, was also around at that time (though he matriculated on the Yale campus as a roommate of Bulldog tackle Ted Livingston; another player admits that the team played a small role in Bush’s being arrested for tearing down goalposts at a November 1967 game) and so was a Vassar student who, like Jones, also later eked out a successful career in films (winning two Academy Awards for her thespic emoting): Meryl Streep. (A teammate of Yale fullback Bob Levin, who was dating Streep, remarks that he’s really been surprised by Meryl’s cinematic accomplishments because in those days she’s was a bit on the quiet side, “saying virtually nothing.”)

remember telling myself to stay cool and be smooth”) with wry observations about the game…and about his equally famous college roommate, former Vice President Al Gore — who Jones recalls learned to play “Dixie” on their touch-tone phone (which were just replacing rotary-dial phones at that time) and once helped him prepare a Thanksgiving turkey in a fireplace. Gore’s GOP nemesis in 2000, President George W. Bush, was also around at that time (though he matriculated on the Yale campus as a roommate of Bulldog tackle Ted Livingston; another player admits that the team played a small role in Bush’s being arrested for tearing down goalposts at a November 1967 game) and so was a Vassar student who, like Jones, also later eked out a successful career in films (winning two Academy Awards for her thespic emoting): Meryl Streep. (A teammate of Yale fullback Bob Levin, who was dating Streep, remarks that he’s really been surprised by Meryl’s cinematic accomplishments because in those days she’s was a bit on the quiet side, “saying virtually nothing.”)

Yale quarterback Brian Dowling has also registered in the pop culture consciousness, though not in the way he probably expected. During his heyday at the college, the Bulldog’s captain (who was nicknamed “God” by his fellow players and classmates; a Yale Daily News headline even once read “God Plays Quarterback for Yale”) and his team were frequently parodied in a comic strip that ran in the campus paper entitled Bull Tales, drawn by an underclassman named Garry Trudeau. Trudeau added the character of “B.D.” to his dramatis personae of Doonesbury, his Pulitzer Prize-winning creation.

The main character of Mike “the Man” Doonesbury is speculated by one player to have been based on Yale’s defensive captain, linebacker Mike Bouscaren, who is nothing like his illustrated counterpart is that he’s not quite as likable at certain times. He’s also a good example of how athletes have a tendency to embellish their

gridiron exploits in a revealing segment when he boasts of “taking out” Harvard halfback Ray Hornblower, dealing Hornblower an injury to his ankle that sidelined him for the rest of the game. (According to Bouscaren, he held a grudge against Ray when the Harvard player left Mike’s jockstrap on the ten-yard-line in a junior year game.) As the risk of using the old cliché “let’s go to the videotape,” an analysis of the video playback shows that Bouscaren wasn’t anywhere near Hornblower when the injury occurred. Nostalgia often has a way of clouding important events: John Waldman, a Yale player who got in the game for one play but whose pass interference penalty was just one of the many chinks in the Bulldog armor during the contest’s final crucial minutes, says he’s watched the video “4,000 times” and is pretty sure he “never touched” Harvard’s Pete Varney. (I watched it only once and it’s obvious the ref made the right call. Facts are stubborn things.)

gridiron exploits in a revealing segment when he boasts of “taking out” Harvard halfback Ray Hornblower, dealing Hornblower an injury to his ankle that sidelined him for the rest of the game. (According to Bouscaren, he held a grudge against Ray when the Harvard player left Mike’s jockstrap on the ten-yard-line in a junior year game.) As the risk of using the old cliché “let’s go to the videotape,” an analysis of the video playback shows that Bouscaren wasn’t anywhere near Hornblower when the injury occurred. Nostalgia often has a way of clouding important events: John Waldman, a Yale player who got in the game for one play but whose pass interference penalty was just one of the many chinks in the Bulldog armor during the contest’s final crucial minutes, says he’s watched the video “4,000 times” and is pretty sure he “never touched” Harvard’s Pete Varney. (I watched it only once and it’s obvious the ref made the right call. Facts are stubborn things.)

1968 was a year of tremendous social and political upheaval, and as such it’s interesting to hear many of the interviewees cogitate on how those events influenced their actions and thinking at the time. The insular and isolated Yale campus (where the Young Americans for Freedom maintained a larger presence than Students for a Democratic Society) was nevertheless unable to divert its attention from hot-button topics like the Vietnam War and the sexual resolution (viewers need to be reminded that, as Bulldog safety J.P. Goldsmith cracks, “women hadn’t been invented yet”—the Yale campus was still an all-male preserve at the time) and Harvard, long considered a “hotbed of liberalism,” sometimes experienced conflict between anti- and pro-Vietnam war players (such as defensive back Pat Conway, who animatedly recalls how he’d defiantly walk through picket lines situated outside the Yard’s buildings, monitored by politically-motivated students). But at a time when, as Goldsmith puts it, “everybody had a mad on,” hippies and brown shoes put aside their differences every Saturday in New Haven for football…and in Cambridge, any potential political knockdown/drag-outs took a back seat as those opposed and supportive of the U.S. overseas suited up for the sake of The Game.

Director Kevin Rafferty, who’s perhaps best known for his hilarious 1982 nuclear propaganda pastiche The Atomic Cafe (not to mention mentoring Michael Moore), has created a classic true story-narrative that

resonates with viewers because it’s a timeless tale of the triumph of the underdog. You can’t help but identify with the Harvard players who were astonished at how they were able to stave off an almost certain defeat even when they were “getting their butts kicked” and suffering jeers from the Yale supporters in the stadium (taunting the team with cries of “We’re Number 1” and “You’re Number 2”). But the beauty of Harvard Beats Yale is that the opposing team didn’t lose perspective as a result of their “defeat” and that concept remains the underlining impression throughout the film. “I’m glad that we lost,” Bouscaren muses as the film nudges toward its conclusion. “Because if we had won I’d probably have more difficulty becoming just a regular person…becoming a person who understands that all in life is not fair — that you can’t win all the time, and it’s good to be humble.”

resonates with viewers because it’s a timeless tale of the triumph of the underdog. You can’t help but identify with the Harvard players who were astonished at how they were able to stave off an almost certain defeat even when they were “getting their butts kicked” and suffering jeers from the Yale supporters in the stadium (taunting the team with cries of “We’re Number 1” and “You’re Number 2”). But the beauty of Harvard Beats Yale is that the opposing team didn’t lose perspective as a result of their “defeat” and that concept remains the underlining impression throughout the film. “I’m glad that we lost,” Bouscaren muses as the film nudges toward its conclusion. “Because if we had won I’d probably have more difficulty becoming just a regular person…becoming a person who understands that all in life is not fair — that you can’t win all the time, and it’s good to be humble.”“If it wasn’t for that game they wouldn’t be remembered today,” adds Harvard’s Frank Champi, referring to his gridiron competitors and their win-some, lose-some outlook on the final results. “It’s a win-win for everybody.” Precisely the sentiment I would beg, borrow and steal to describe my experience watching this exceptional film.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Documentary, Streep, Tommy Lee Jones

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, February 18, 2011

Walk Away. Drop It.

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post is part of the For the Love of Film (Noir): The Film Preservation Blogathon hosted by Ferdy on Films and The Self-Styled Siren. To donate to the fundraiser for The Film Noir Foundation, click here.

By VenetianBlond

First time director Rian Johnson walked away with the 2005 Sundance Special Jury Prize for originality of vision for his film Brick. Starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Lukas Haas, it was an attempt to film a noir but with a completely different set of visual cues. Rather than creating a 1940s detective in a rainy New York or Chicago, Johnson set his plot in motion in a modern Southern California high school. In the DVD commentary, Johnson admits that his script was on a knife edge-the slightest misstep in tone would have made it “dreadful.” However, apart from a couple of minor quibbles, I agree with the Sundance jury that he pulled it off.

Before the title, Brendan (Gordon-Levitt) is crouched at the mouth of a tunnel, staring at the body of a woman. After the title, she is seen placing a note into someone’s locker, and the next title is “Two Days Previous.” The flashback, of course, is a classic noir technique. The note sets up an increasingly desperate phone call, in which the woman, Brendan’s ex-girlfriend Emily, pleads for his help. They’re cut off before Emily can agree to meet him and Brendan begins a convoluted search. He gets information from Brain, a kid who sits in a hallway and seems to know everything about who’s eating lunch with whom and why. He also finds a scrap of an invitation to a popular rich girl’s party and he shows up. Everyone he talks to seems to know something and is incredibly reluctant to tell him anything.

He does eventually meet up with Emily, but she’s too scared to let him in on what is going on. She begs him to let her go, but he finds he can’t. In fact, he pickpockets a notebook from her in which he finds a clue that leads him to her body in the tunnel. He hears someone in the tunnel and pursues only to get knocked out. He’s now set on his path. In fact, he asks Brain to tell him to drop it, but then he enlists his help in getting to the bottom of what happened.

He also flashes back two months to when he and Emily broke up. Little half-clues lead him through the small-time drug dealing scene at the school, until he finds out about The Pin, as in Kingpin (Lukas Haas). He also

finds out about the brick — a brick of heroin cut badly that killed an underling who took a little off the top. Emily was blamed for the debacle, although Brendan can’t believe that she was in that deep. He insinuates himself with The Pin so that he can stay close, and ends up attempting to mediate a rising gang war between The Pin and Tug. Tug is The Pin’s hired muscle, also involved with Emily, who had been administering harsh words without the words to Brendan throughout. In the end, it was the rich girl Laura who set Emily up to take the fall for the deadly heroin. Brendan, who earlier rebuffed Laura, saying he couldn’t trust her, plants the remainder of the brick in her locker and notifies the authorities, but Laura has her own knife to twist. In their final confrontation, she reveals that Emily was pregnant with his child. Brendan brings Laura down, but at a terrible cost.

finds out about the brick — a brick of heroin cut badly that killed an underling who took a little off the top. Emily was blamed for the debacle, although Brendan can’t believe that she was in that deep. He insinuates himself with The Pin so that he can stay close, and ends up attempting to mediate a rising gang war between The Pin and Tug. Tug is The Pin’s hired muscle, also involved with Emily, who had been administering harsh words without the words to Brendan throughout. In the end, it was the rich girl Laura who set Emily up to take the fall for the deadly heroin. Brendan, who earlier rebuffed Laura, saying he couldn’t trust her, plants the remainder of the brick in her locker and notifies the authorities, but Laura has her own knife to twist. In their final confrontation, she reveals that Emily was pregnant with his child. Brendan brings Laura down, but at a terrible cost.The film is a little more than two hours long, so this recap naturally elides over many plot points and character developments. What’s interesting is that what seems like a gimmick actually works really well. On one level, the archetypes overlay onto high school characters: the femme fatale, the dupe, the muscle, the ringleader. But Brick works on other levels also. Johnson has his actors using language straight out of Hammett. “Keep your specs on,” “I’ll just stand here and bleed at you,” and one of my all-time favorite movie lines, “I got all five senses and I slept last night so that puts me six ahead of the lot of you,” are examples of the heightened speech used in the film. Would teenagers really speak that way? Not really, but they are expert at developing their own speech patterns and slang in direct rebellion to “regular” speech. If anybody would be speaking strangely and using words that don’t make sense to anybody else, it would be a teenager.

Second, the production and filming mirror the noir style perfectly. In other words, they were broke. Johnson shopped his script around for years until he finally gave up and financed it himself with friends and family. For that reason, they used zooms instead of tracking shots. They used low-tech effects. They used the locations they could get access to, whether or not there was actually room for a camera. This created the conditions for a film that looks very much like the traditional noirs — with crazy angles and less than “perfect” lighting.

Third, Johnson said in the DVD commentary that the film was not meant to be realistic. The language is part of the signaling that the world of Brick is not supposed to reflect anyone's actual experience. It was not meant to be high school as much as it was meant to feel like high school. “When you are a teenager and you are in that world, you don’t have any perspective and it’s the most serious time in your life. Your head is completely encased in that fishbowl, and it IS life or death, these small things, because it’s your entire field of vision.” Even though we know from the beginning that Emily is dead, Brendan’s quest is not so far off from the real teenage experience. Why didn’t it work out? Why is she hanging out with those people? What does she see in that guy? Why can’t I figure ANYTHING out? In addition, where else would an unintended pregnancy resonate in the same way as it would in 1947? In high school, perhaps.

Now for the quibbles. There are two scenes in which Brendan’s world crosses the “real” world. In the first, he has an encounter with the vice principal, and in the other, he meets The Pin’s mom. The scene with Vice Principal Trueman (Richard Roundtree) is terrific. The vice principal’s noir analogue is the police chief on the hero’s trail. He indicates that Brendan has been in trouble before, has helped them out before, and that he can give Brendan only so much leeway. This scene was filmed in a real office, with the camera on the floor (or close to it) so the uniform upward angles make it look like a battle of wills between equals.

The other scene, with The Pin’s mom, doesn’t make much sense. She serves them orange juice, no wait, she’s so sorry, they don’t have orange juice…perhaps she’s meant to be the dippy dame. Upon several viewings, it still doesn’t seem to serve the plot, and is as jarring as the first time I saw it.