Monday, September 16, 2013

From the Vault: JFK

BLOGGER'S NOTE: I'm re-posting this review, originally written when JFK opened in 1991, as part of The Oliver Stone Blogathon occurring through Oct. 6 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie Lover

Seldom has reviewing a film proved as problematic as Oliver Stone's JFK. So much has been written about what is — and isn't — accurate in this film that I went in desperately trying to view solely on a cinematic basis, ignoring the fact that it concerns that fateful November day in Dallas in 1963. That sort of objectivity ends up being impossible because JFK demands evaluation and analysis and obliterates any chance of passive viewing with its strange hybrid of thriller, murder mystery and documentary.

Kevin Costner plays the lead in Stone's story as New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison, who launched a full-fledged investigation into the conspiracy he believed left both John F. Kennedy and the country mortally wounded. "Fundamentally, people are suckers for the truth," Donald Sutherland's Deep Throat-type character tells Garrison at one point in the film. While it remains to be seen whether Stone's version contains more truth than the preposterous idea that Lee Harvey Oswald (played well by Gary Oldman, part of the film's gargantuan, excellent ensemble) acted alone, fascination with the assassination keeps this three-hour film compulsively watchable.

Problems plague the film other than the ones that spark so much debate. Despite allegations that the film comes off as homophobic (I see why that charge has been leveled) or exists as nothing more than propaganda (could be), it fares fairly well. Stone keeps the pace speeding along most of the time except for a middle section that lags. His editing and jump-cuts that mix real footage, re-creations and original material triumph, especially in the film's very good opening segments. The movie stumbles the most when it presents scenes of Garrison's domestic life with his wife Liz (a thankless task given to the usually reliable Sissy Spacek, saddled with dialogue along the lines of "I think you care more about John Kennedy than your own family!") It also doesn't help that Garrison's son (played by Stone's own 7-year-old son Sean) never ages though the film covers more than half a decade.

Other demerits include John Williams' score, which nearly overpowers important scenes such as Sutherland's magnetic spinning of key elements of the "conspiracy" so that it makes sense as he's sharing it, and, it should really go without saying, Costner himself. While he manages to be fairly consistent with his Southern accent, he still can't emote effectively. He's a star, not an actor. Much of the popular opinion about the real Garrison refers to him either as someone seeking publicity or a crackpot. Regardless, Costner can't convey his obsession or possibly unstable nature. In his overrated Dances With Wolves, his lack of acting skills presented a similar problem. Both JFK and Dances would have been better served if they'd cast a performer capable of portraying people losing control. Lt. Dunbar tries to commit suicide and then asks to be placed on the frontier, but Costner couldn't pull off that conflict any more convincingly than he pulls off Garrison's drive for the truth.

Thankfully, able supporting performers abound to pick up the slack, even if they appear for a single scene. Actors deserving particular praise include Ed Asner, Kevin Bacon, John Candy, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Joe Pesci, Sutherland and Tommy Lee Jones, who gives a good performance despite the possible perception of his character as an offensive stereotype. Structurally, the film weakens in its final act by climaxing with Garrison's prosecution of Clay Shaw (Jones). While this conclusion comes naturally to a film focused on Garrison, it seems anticlimactic to the film's real subject — dealing with the demons of the past. Stone's obsession with the Vietnam era equals Garrison's with Kennedy's murder. Methods separate Garrison's obsession from Stone's. Stone uses cinema as his rosary to drag the audience kicking and screaming into his personal confessional. With JFK, that's not altogether inappropriate. Even people born since the assassination grew up with the myths and the facts of Nov. 22, 1963, as part of their lives, though for most of the younger of us, Jim Garrison and his actual prosecution of Clay Shaw was something few of us knew about until Stone's movie.

Growing up though with the history of the Kennedy and Martin Luther King assassinations ingrained in our brains shortened our attention span of shock when John Lennon, Reagan and Pope John Paul II encountered bullets in a period of just a few months. The explosion of the space shuttle Challenger seemed to affect us for only an hour or two instead of the lifelong effect JFK's assassination had on an earlier generation.

Personally, I don't know if I buy the revamped Garrison theory that Stone offers. I don't see how anyone can believe Oswald acted alone or all the shots came from behind — watching the Zapruder film enlarged on the big screen makes the "back and to the left" motion of Kennedy's head unmistakable. However, Stone can't quite pull off the idea that the reason Kennedy was killed was so the Vietnam War could happen.

In that respect, JFK plays like a murder trial where only the prosecution presents its case. I'm certainly no apologist for Oliver Stone and I think most of his films grow weaker on subsequent viewings. Indeed, his tendency to pass off fabrication as fact can be troubling when most viewers can't tell the difference. Reservations aside, JFK holds one's attention firmly and deserves a look.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Costner, D. Sutherland, John Williams, Kevin Bacon, Lemmon, Matthau, Oldman, Oliver Stone, Pesci, Spacek, Tommy Lee Jones

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

A Riddle Wrapped in a Mystery Inside an Enigma

By Damian Arlyn

While some might be of the opinion that Oliver Stone’s most archetypal movie is Wall Street or Platoon, I happen to think the film which holds that particular distinction is JFK (which celebrates its 20th anniversary today). It is not necessarily his greatest movie, but it is his most significant in a number of ways. In a career littered with provocative, politically charged works, it has proved to be arguably his most controversial. It marked the beginning of a stylistic period in Stone’s filmmaking (a fast, in-your-face approach to storytelling which culminated in Stone’s outrageously anarchic Natural Born Killers). Finally, it was (and still seems to be) one of Stone’s most personal projects: the result of years of research, overwhelming passion and righteous indignation. Indeed, of all Stone’s protagonists, the man at the center of JFK (who is, somewhat ironically, not the titular character) serves as perhaps the best representative of the ideals and opinions of Oliver himself. In reality, the motives and actions of New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison (the only prosecutor ever to go to trial in the assassination of President Kennedy) are not entirely clear nor always seem purely honorable, but in the film, Garrison — wonderfully played by Kevin Costner — is a man on a crusade, a courageous hero of the highest intentions and noblest stature crying, “Let the truth be told though the heavens fall!” He is the director's alter ego, a lone wolf fighting the establishment in the name of truth, justice and, yes, the American way.

JFK was my first Oliver Stone picture. My dad took me to see it in the theater when I was a sophomore in high school and I was, as the expression goes, blown away by it. Incidentally, he was (and still is to some degree) a major expert on the Kennedy conspiracy, so he was able to lean over and tell me at various junctures "That's true" or "That's not true" which helped orient me in the somewhat overwhelming

deluge of faces, names, dates and theories with which I was being bludgeoned. My dad once owned the largest collection of books, magazines, videos and even vintage newspaper articles about that specific event which I have ever seen. After watching the film and concluding that there definitely was a conspiracy and a cover-up, I even read a few of them myself, including the screenplay to the film which contained a footnoted source for every piece of information that Stone wrote into the expository dialogue and/or imagery of the film. It gave me a whole new appreciation for a movie's potential to tell a story which, if not "true" or "historically accurate," is at least "factual." Eventually I became somewhat of an expert myself and years later, after getting married and moving to Dallas, I finally visited the sixth floor museum and Dealey Plaza (the latter of which, I was shocked to discover, is a very small, and intimately contained space). Now, however, having read multiple accounts from different writers arguing for both sides of the conspiracy debate — including this very compelling website run by Dave Reitzes, whose experience with the film is remarkably similar to my own — I have no idea what really happened on that day in Dallas (though I still think there is more to the story than we are being told). However, one thing that has not changed, is that JFK remains a seminal film in my development as a cinephile.

deluge of faces, names, dates and theories with which I was being bludgeoned. My dad once owned the largest collection of books, magazines, videos and even vintage newspaper articles about that specific event which I have ever seen. After watching the film and concluding that there definitely was a conspiracy and a cover-up, I even read a few of them myself, including the screenplay to the film which contained a footnoted source for every piece of information that Stone wrote into the expository dialogue and/or imagery of the film. It gave me a whole new appreciation for a movie's potential to tell a story which, if not "true" or "historically accurate," is at least "factual." Eventually I became somewhat of an expert myself and years later, after getting married and moving to Dallas, I finally visited the sixth floor museum and Dealey Plaza (the latter of which, I was shocked to discover, is a very small, and intimately contained space). Now, however, having read multiple accounts from different writers arguing for both sides of the conspiracy debate — including this very compelling website run by Dave Reitzes, whose experience with the film is remarkably similar to my own — I have no idea what really happened on that day in Dallas (though I still think there is more to the story than we are being told). However, one thing that has not changed, is that JFK remains a seminal film in my development as a cinephile.

Much can be said about the movie's many stellar qualities, such as the performances from its immense cast (a dizzying collection of such familiar faces as Sissy Spacek, Joe Pesci, Tommy Lee Jones, Kevin Bacon, John Candy, Ed Asner, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Gary Oldman, Donald Sutherland, etc). In a nice bit of subversive casting, Stone even got the real Jim Garrison to portray Judge Earl Warren of the Warren Commission. Much could also be said about John Williams' suspenseful and emotional Oscar-nominated music score, but the main element of the film which captivated me upon my first viewing (and which I studied very carefully upon numerous subsequent viewings) was its visual aesthetic. In order to make a film which was heavy on talk into an arresting experience, Stone deftly employed various cinematic techniques that until that time had never been employed with such enthusiastic exuberance nor wild abandon in a historical epic.

His approach to shooting and editing the film was considered confusing and indulgent by some and incredibly powerful and innovative by others. I personally fell into the latter camp. Jumping back and forth (sometimes in a seemingly random manner) from authentic to recreated footage, from color to black-and-white and from 35 to 16mm, JFK creates such an apparently chaotic product that people didn't know what to make of it. The more one delves deeper into it though, the more one discovers that there is indeed "method in the madness." Stone's is a stream-of-consciousness approach to examining history, a process that makes no distinction between past and present, between what has happened and what is happening and, perhaps most controversially, between theory and fact. To Stone, history is in the eye of the beholder and he presents so many different perspectives, ideas and judgments that he was essentially, as film critic Roger Ebert proposed, fighting the official establishment myth by "weaving a counter-myth." Not surprisingly, Stone's effort garnered a great deal of criticism from various esteemed news sources. It did not help their case that they were attacking the film well before it had come out and anyone, including them, had even seen it, their zeal and hostility seemingly inspired more by fear of losing their privileged authoritative status than by supposed journalistic integrity and objectivity.

In spite of (or perhaps because of) JFK's notoriety, it was very well-received upon its release in December 1991. The film grossed more than $50 million worldwide, which was impressive considering that the film was more than three hours long, and ended up receiving eight Academy Award nominations, including best picture, best director and best supporting actor for Tommy Lee Jones. It ended up winning two of those awards for the experimental cinematography and editing. It also, much to Stone's delight no doubt, incited a whole media discussion about the Kennedy assassination. Much like the media circus that surrounded the release of Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, all you could see and hear on the news for several months was talk of what actually occurred on Nov. 22, 1963. In point of fact, we probably will never know what occurred. As Pesci's nervous David Ferrie quotes Winston Churchill in the film, "It's a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma." Still, perhaps whether we ever know the truth (or, to be more precise, know THAT we know the truth since we may already know it) isn't as important as that we never give up looking for it. Maybe the real message behind the film is that the pursuit of truth is more important then the possession of it.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Costner, D. Sutherland, Ebert, John Williams, Kevin Bacon, Lemmon, Matthau, Mel Gibson, Movie Tributes, Oldman, Oliver Stone, Oscars, Pesci, Spacek, Tommy Lee Jones

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, June 25, 2011

Someone Is Watching

By Josh R

It is now more than 50 years since Jane Fonda’s image first flickered across movie screens in Josh Logan’s Tall Story, though in truth she has been a part of the public consciousness much longer than that. Her childhood — a subject, like so many others, about which she remains conflicted — was well-documented, and provides clues as to the circuitous, unpredictable, occasionally perilous path she has traveled ever since. She was the daughter of an American icon, beloved by the public but emotionally distant at home, and a mother whose suicide remained largely unexplained for years following her death. The disconnect between the reality of those years, as she and her brother experienced them, and the version of their family life that people read about in magazines, was as vast as the divide between Barbarella and Hanoi Jane.

Jane Fonda has bridged those gaps, among many others — if not always comfortably, then with a certain kind of fearlessness. Whether this quality can be characterized as courage or recklessness, enterprise or folly, soul-searching or self-sabotage, remains subject to interpretation. She was never a premeditated chameleon, like Madonna, whose aggressively exhibitionistic persona never really changed no matter how many times her hairstyle and fashion choices did. Fonda’s transformations and reincarnations, which were much more radical and even more difficult to reconcile (even, at times, by the lady herself), seem to have been a product of curiosity, in part triggered by the irresolute feelings brought on by self-examination, and a reflection of the turbulent times through which she has lived. The name itself has different associations for different people. My 24-year-old co-worker knows her only as a spandex-clad fitness guru staring out from the cover of a VHS tape on his mother’s bookcase; a 30-year-old friend remembers her as a celebrity fan, sitting next to Ted Turner during playoff season in Atlanta and cheering enthusiastically each time Chipper Jones parked one deep into left field. Some regard her as an icon; to others, she was and remains a traitor. When I think of Jane Fonda, I think of Klute. If Jane Fonda’s life has been a study in contradictions, there is no more brilliant study of the conflicted nature of the human soul, and the manner in which bracing intelligence can exist at striking odds with naked emotionalism, than her astonishing, revelatory performance in Alan J. Pakula’s 1971 suspense thriller, celebrating its 40th anniversary today. If I judge it to be among the greatest performances ever committed to celluloid, it is in no small part due to the fact that, whenever I am watching it, all other associations I have with Jane Fonda — cultural symbol, cinematic legend, perennial lightning rod for controversy — never enter my mind. When I see her in Klute, I see only Bree Daniels.

Klute is ostensibly the story of a prostitute being stalked by a killer. In reality, it’s a film about role-playing, and the means by which people keep their true nature concealed from others in order to survive. In a way, both the predator and his prey are in the same boat, operating behind a carefully maintained façade as a means of self-protection. When the façade begins to crack, both find themselves at risk. The catalyst for their unmasking is an investigation conducted by John Klute (Donald Sutherland), a small-town policeman who has come to New York to track the whereabouts of a missing friend. His only lead is Bree, a hardened pro who has received threatening anonymous letters from someone believed to be the man he is searching for. Although she initially greets Klute’s inquiries with hostility and resistance, Bree agrees to help with the search; she eventually begins to trust and develop feelings for him. As they get closer to unraveling the mystery, Klute becomes her friend, protector, and lover. While Bree fights her self-destructive need to sabotage their relationship, a killer lurks in the shadows, fearful of exposure and determined to destroy the object of his obsession and the agent of his potential unmasking. Bree knows that she is being watched — what neither she nor Klute realize is that she is at even greater risk than either of them could have possibly imagined.

Pakula’s lean, economical approach to the material showcases the performance of Jane Fonda, but the film does not simply exist in service to her tour-de-force. The director’s methods aren’t flashy, but Klute is nevertheless visually and stylistically interesting, building tension through camerawork, use of music, and carefully devised environmental set pieces that contribute a visceral sense of atmosphere to the proceedings. Most of the action takes place in Bree’s dingy, claustrophobic apartment and on the grimy mean streets of New York City, photographed in a washed-out color palette which emphasizes the impersonal, atrophied nature of the broken-down world denizens of the criminal subculture inhabit. This is no picturesque version of the city as seen through rose-colored glasses; what we see is a grittier, tougher version of the urban jungle as a kind of crumbling Babylon — desiccated, at once both decadent and seedy, and full of hidden dangers. When, in one startling sequence, Klute and Bree go searching for a woman who may be able to shed some light upon the case — a drug-addicted streetwalker named Arlyn Page who’s sunk so low that she’s fallen off the grid — the film becomes a nightmarish tour through the underbelly of the urban sex trade, showing the desperation, waste, and sense of helplessness which characterize sordid lives lived on the margins and conducted in the shadows.

Remarkably, Pakula’s treatment of his subject matter is in no way sensationalistic. The director doesn’t gawk at his subjects or invite the audience to leer at the catalog of perversions on display; John Klute is a stand-in for the viewer, and the images and behaviors both he and the audience encounter are too sad and human to be titillating. Even in the one scene that features nudity — Bree does a striptease for an elderly client in the office of his garment manufactory — the audience doesn’t feel as though they’re witnessing something prurient or being prompted to judge. The old man watches Bree with something strangely resembling gratitude while she rattles off a ludicrous Harlequin-romance fiction about being seduced by a handsome stranger on the beaches of Cannes. It’s a strangely fragile moment, with a disarming kind of courtliness to it; Bree is acting out a fantasy for someone whose life is so far removed from anything resembling gentility and glamour that this brokered charade is as close as he’ll ever get to it. Even moments that should be pathetic or repellent are imbued with a deep sense of empathy for the people involved. When Bree and Klute locate Arlyn and her boyfriend, they are in a state of panic, waiting for their dealer and jonesing for a fix. The dealer finally materializes, only to be frightened away by the presence of strangers — the addicts attempt to secure his return, without success. When they come back to the apartment, Arlyn strokes her boyfriend’s hair and soothes his forehead with a damp cloth; as strung-out as she is, she is assuming the role of maternal caretaker and showing concern for someone she loves. Pakula’s approach is unfailingly humane; even when observing the indignities of human degradation, the film pauses for small moments of grace.

It’s those small touches — the details, really — that lend the material a deeper sense of relevance beyond the standard-issue polemical observations about the dangers of prostitution, drug use, or even the unchecked permissiveness of a society that has lost its moral compass. Klute is not a feminist film per se, but the director and screenwriter pay particular attention to the reductive attitudes society assumes not just toward women on the margins of society (prostitutes and addicts) but women in general. The first woman we encounter in the film is not Bree, but the wife of the missing man; she’s a meek, helpless figure being grilled by detectives about her husband’s sexual proclivities, and powerless to either defend him or take any action on her own in terms of tracking him down. Regardless of what she says or does, the detectives have already made up their minds that the husband is living some kind of secret life based in deviant behavior; they choose to believe this, in part because they find the wife so unexciting — who wouldn’t stray from the reservation in search of something else? Bree is introduced in a very unorthodox manner; not in a star’s lingering close-up, but in a long line of women the camera pans across as a two disembodied voices — casting directors, looking for a model for an ad campaign — mercilessly critique each candidate based on her physical attributes. After Bree has been cursorily examined and summarily dismissed, the camera pans to the next woman in line. Pakula is showing us Bree as she’s viewed by the world — not as an individual, but as a disposable commodity, the value of which is determined by external appearances. In one of many sequences in which Bree is observed in session with her analyst, she notes how men “want me…well, not me…but they want a woman....” The johns who pay for Bree don’t care any more about her than she does about them — she’s something to be used, and she feels that she’s using them in turn.

As well-enacted as the analysis scenes are — valuable not because they serve to advance the plot, but because of what they reveal about Bree’s mindset — their presence is not essential; Fonda brings such emotional honestly to the performance that the internal life of the character is made explicit — she communicates everything Bree is thinking and feeling without even having to verbalize it. When she’s with her johns, she’s in complete control — she doesn’t have to experience anything on an emotional level, because it’s all part of the act. It’s only when she’s alone, curled up in bed and scared to pick up the phone, that her vulnerability comes into clear focus; the tough-cookie exterior and you-can-all-go-to-hell attitude mask the fragile soul of a wounded, frightened child. The relationship with Klute brings out feelings Bree didn’t even know she was capable of; feeling something genuine for another person is a new experience for her, and since she isn’t pulling the strings, she can’t adjust to what’s happening. So terrified by the prospect of relinquishing control that she can’t allow herself to be happy, Bree is trying to make sense of her willfully self-destructive impulses while at the same time holding painful realizations at bay for fear of what she might find. It’s a brave, unflinching performance that reveals something new upon each additional viewing, astonishing for both its complexity and the emotional transparency with which it is achieved. Among those “non-verbal” moments that have always stood out for me: the rueful turn of the head, as though she’s just been slapped in the face, when Bree learns that a sadistic, abusive john was deliberately sent to her by a jealous friend; the wistful, almost bewildered look she gives to a child perched on his father’s shoulders, as if she’s imagining for the first time what it might feel like to be a mother; the amazing sequence when, heavily stoned, she wanders through a club, registering all the conflicting emotions she’s feeling — defiance, vulnerability, excitement, dread, relief, self-loathing — as she makes her way through the crowd to her former pimp, curling up catlike against him as Klute looks on dumbstruck. Above all, there is the amazing moment where, cornered by the sociopath who has been stalking her, she is forced to listen to a recording of another call girl being savagely murdered. Fonda has written that she was surprised by her own reaction when the scene was actually being filmed; instead of experiencing a sense of terror, she was overcome with grief for her friend — and indeed, for all the women who do what they have to in order to survive, and have the life crushed out of them by a world that doesn’t really care whether they live or how they die.

Anyone who follows this blog with any regularity is doubtless bored to tears with my constant bemoaning of the popular wisdom by which greatness in acting is measured. For those who prefer flashy pyrotechnics to emotional honesty — and the unadorned simplicity that usually accompanies it — there will never be any dearth of strenuous physical and vocal transformations to fill out Oscar categories for years to come (any day now, I’m sure Cate Blanchett will strap on a hump to play Richard III; I’ll probably be home watching TCM when that happens). The rewards for working from the outside in are greater than working from the inside out, and I’m sure there are some who look at Jane Fonda’s work in Klute and say “So what? She looks and sounds like Jane Fonda.” Of course, Bree Daniels is not Jane Fonda any more than On the Waterfront’s Terry Malloy is Marlon Brando — they are independent creations, possessed of their own unique qualities, drives, and desires, and they have been brought to life with such raw intensity that they transcend the conventional definition of acting. Call it channeling, sorcery, whatever you will — it amounts to a pretty rare feat. When I saw the actress last, on Broadway, in a play called 33 Variations, it was very apparent that Jane Fonda is still possessed of the talent, energy, and skill to breathe life into a role in a way that others seldom can. It may not be easy for her to find roles that are commensurate with her abilities, but when she does, she still knows how to make them count. At the end of Klute, Bree Daniel’s fate is left open-ended; but for the purposes of the film, at least, her story has come to a close. Thankfully — for all of us — Jane Fonda’s is still being written.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Blanchett, Brando, D. Sutherland, J. Fonda, Movie Tributes, Oscars, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, December 01, 2010

Films That Transcend Their Weaknesses

By Squish

Not only does it have a terrible title, but the ending of Don't Look Now is laughable, containing the kind of climax that made me ask out loud, "Seriously? You couldn't come up with anything better than that?" But this is not why we are here today. I'd much rather go on about what makes this film genuinely great, what makes it work.

First the basic premise: a British couple suffer a devastating loss, a daughter killed in a drowning accident. The couple attempt to forge ahead and make a new life pulling up stakes and moving to Venice. Once there, the couple meet a psychic woman who claims not only to be able to see their deceased daughter, but that her father, John (Donald Sutherland), also has the gift of second sight. The mother, Laura (Julie Christie), wants to learn more while John wants nothing to do with this "psychic."

The film follows the thriller genre rather closely with heavy moments of drama, especially the strained relationship between husband and wife. If you've heard anything about the film, you'll know that Don't Look Now is famous for its sex scene. Throughout the film the couple have some heated arguments, and due to their frequency, the director felt the need to add an improvised sex scene to convey the love the couple shared as well. The scene is incredible because the couple is so perfectly natural in this moment, so much so that it is rumored for being actual "Julie on Donald" action.

The famous scene includes editing that cuts in the next moment of their slowly getting dressed for a dinner. Donald stands in front of the mirror, naked, brushing his teeth, while his wife also is there, nude, doing her own thing. Don't Look Now helped me realize the immediacy films tend to have in "getting on" with a sex/nude scene, as though throwing in a slice of "cheeky" for the folks at home rather than making it relevant to the characters. Don't Look Now, in that famous scene, did such a good job of conveying such familiarity between an on-screen couple that you know how close they are, that the fighting is just a fleeting thing compared to their sense of belonging to one another. Because it shows long takes of nude people in an everyday moment, we get a proper glimpse into their routine and we get it, we get them in this vulnerable yet trusting moment.

What Don't Look Now should be praised for, however, is not the sex scene, it's the atmosphere that is so perfect as to teach valuable lessons about suspense in cinematographic style.

Don't Look Now is creepy in that way that makes you doubt everything. Those I watched this with kept saying "something's off about that person too!" To compare to David Lynch's odd characters would be too severe. These quirks are far more subtle. Enhanced by the mood that has been set before, we're left with nothing more than a constant gut-feeling of something being amiss.

Film tends to be good for showing us exactly what we need to know to set up a moment — something as simple as showing a close-up of a gun lying next to a passed-out person, well you know what that means already. Watching Don't Look Now's restaurant scene where we're shown a lunch table, a close-up of a blind woman's broach, the waiter bringing a tray of food to the next table, a snippet of conversation, followed by a rapid close-up of people moving behind Laura... you just know something's about to happen, you're on edge, and Don't Look Now is one of the films I will forever reference as being able to perfectly deliver such red herrings. Rather than the camera showing us what we need, it shows us things in much the same way our own eye would during a time of high stress or danger: perception jumps, everything is slower... when a lens can recreate in us the same feeling our own mind would, that's more than impressive. What's great is that this is done frequently throughout the film, and for that reason alone, Don't Look Now is worthy of being brought out of obscurity.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, D. Sutherland, Julie Christie, Lynch

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, March 09, 2010

Old Altmans never die (or fade away)

visions of the things to be

the pains that are withheld for me

I realize and I can see...

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

By Edward Copeland

It began life as a novel by Richard Hooker, then Robert Altman transferred MASH into a movie and made his reputation. Later, Larry Gelbart transformed that film into a television comedy and made it a landmark series, adding the asterisks to the title M*A*S*H. Altman's film had its New York premiere in January 1970, but back in those days of slow, platform releases, there was no one day when it spread to the rest of the U.S. at once. The best I can find is that it was in March, so I pick today to mark the movie's 40th anniversary.

all our little joys relate

without that ever-present hate

but now I know that it's too late, and...

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

When Johnny Mandel's theme played week after week on the CBS series for 11 seasons, I often wondered what it would have been like if they'd kept Altman's son's Mike's lyrics for "Suicide Is Painless" as well. The sitcom may have taken MASH as its essential template, but they had to draw the line somewhere. (Even an iconoclastic risk taker such as Altman had to let some things from the novel go that early in his career, so we weren't treated to scenes of Elliott Gould as Trapper John dressed as Christ, flying around Korea on a cross suspended from a helicopter and signing autographs to raise money for Ho-Jon's college fund.)

Still, Altman's movie certainly broke ground as far as war movies were concerned and definitely formed the

initial portrait of what a Robert Altman film usually was like: large casts, overlapping dialogue using unusual recording techniques, largely plotless and when they worked, as they did with MASH, great films that changed the medium and that couldn't be mistaken as the work of another director. Watching MASH again for this piece, with its dizzying overheads of helicopters bringing the wounded to the 4077th, I thought of a comparison to another Altman opening for the very first time that came 23 years later: Short Cuts. Only in that instance, the helicopters weren't bearing the injured, they were spraying the injured with pesticide as part of California's battle with the Mediterranean fruit fly.

initial portrait of what a Robert Altman film usually was like: large casts, overlapping dialogue using unusual recording techniques, largely plotless and when they worked, as they did with MASH, great films that changed the medium and that couldn't be mistaken as the work of another director. Watching MASH again for this piece, with its dizzying overheads of helicopters bringing the wounded to the 4077th, I thought of a comparison to another Altman opening for the very first time that came 23 years later: Short Cuts. Only in that instance, the helicopters weren't bearing the injured, they were spraying the injured with pesticide as part of California's battle with the Mediterranean fruit fly.I'm gonna lose it anyway

The losing card I'll someday lay

so this is all I have to say.

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

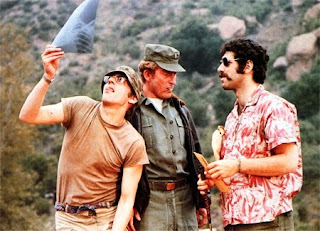

People who know the 4077th only from the TV series will certainly recognize the essential elements in the Altman movie, but they also will discover quite a few differences that follow the novel more closely. Only one cast member from the movie became a regular on the series and that was Gary Burghoff repeating his role as Radar. While the series began basically as Hawkeye (the great Donald Sutherland in the film) and Trapper

against the world, the movie had a third surgeon: Duke, played by Tom Skerritt. While many of the MASH characters share names with the M*A*S*H characters, in many areas they bear little resemblance. Hawkeye is a married man in the movie, not that it prevents his playing around, not Alan Alda's single lothario from the series. Robert Duvall's Frank Burns lives light years away from the buffoonish character Larry Linville grew tired of playing on TV. He's a strictly religious, nondrinker who is teaching Ho-Jon to learn English through the Bible. ("Were you on this religious kick at home or did you crack up over here?" Sutherland's Hawkeye asks Frank as he prays beside his cot.) That doesn't prevent Frank from falling prey his lust for Maj. Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan (Sally Kellerman). However, in the movie, Burns gets carted away early in a strait-jacket after a single prank.

against the world, the movie had a third surgeon: Duke, played by Tom Skerritt. While many of the MASH characters share names with the M*A*S*H characters, in many areas they bear little resemblance. Hawkeye is a married man in the movie, not that it prevents his playing around, not Alan Alda's single lothario from the series. Robert Duvall's Frank Burns lives light years away from the buffoonish character Larry Linville grew tired of playing on TV. He's a strictly religious, nondrinker who is teaching Ho-Jon to learn English through the Bible. ("Were you on this religious kick at home or did you crack up over here?" Sutherland's Hawkeye asks Frank as he prays beside his cot.) That doesn't prevent Frank from falling prey his lust for Maj. Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan (Sally Kellerman). However, in the movie, Burns gets carted away early in a strait-jacket after a single prank.And lay it down before I'm beat

and to another give my seat

for that's the only painless feat.

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

MASH is neither a conventional comedy nor a conventional war film and, since this a Robert Altman movie, you shouldn't expect a conventional climax either. Besides, in a film that is essentially untethered from any

plot, how could there be? So, the big finish for the film's third act is anything but obvious: It's a football game (Shades of the Marx Brothers' Horse Feathers). The 4077th gets challenged to a game by the commander of the 325th Evac. As General Hammond (G. Wood) tells Col. Henry Blake (Roger Bowen) in proposing the game, football is one of the "best gimmicks to keep the American way of life going in Asia." Wood did re-create his role as Hammond in a couple of guest appearances in the early seasons of the TV series. In an eerie coincidence, when McLean Stevenson, the sitcom's memorable Henry Blake died, the following day Bowen died. It almost was like Bowen knew that his death would get little notice unless he piggybacked on Stevenson's as the other Henry Blake. Hammond, of course, has his own ringer, so Trapper and Hawkeye set out to obtain one for their team, a neurosurgeon named Dr. Jones who was better known in his college football days as Spearchucker

plot, how could there be? So, the big finish for the film's third act is anything but obvious: It's a football game (Shades of the Marx Brothers' Horse Feathers). The 4077th gets challenged to a game by the commander of the 325th Evac. As General Hammond (G. Wood) tells Col. Henry Blake (Roger Bowen) in proposing the game, football is one of the "best gimmicks to keep the American way of life going in Asia." Wood did re-create his role as Hammond in a couple of guest appearances in the early seasons of the TV series. In an eerie coincidence, when McLean Stevenson, the sitcom's memorable Henry Blake died, the following day Bowen died. It almost was like Bowen knew that his death would get little notice unless he piggybacked on Stevenson's as the other Henry Blake. Hammond, of course, has his own ringer, so Trapper and Hawkeye set out to obtain one for their team, a neurosurgeon named Dr. Jones who was better known in his college football days as Spearchucker Jones (the film debut of Fred Williamson). They try to brush off the racist nickname by having some ask him why he's called Spearchucker and having him answer that he used to throw the javelin. While I worship Altman, one thing I never quite understood was his insistence that the TV show was racist, specifically against the Koreans, but if anyone can notice any appreciable difference betweeen the film and TV show on that count, I'd love to hear the argument. One of the biggest cheerleaders for the game is Hot Lips and if I have a problem with the film, it's the quick and inexplicable conversion of the Margaret Houlihan character. She's introduced as a no-nonsense, by-the-book Army major, constantly being humiliated by the pranksters of The Swamp (and a wonderful Oscar-

Jones (the film debut of Fred Williamson). They try to brush off the racist nickname by having some ask him why he's called Spearchucker and having him answer that he used to throw the javelin. While I worship Altman, one thing I never quite understood was his insistence that the TV show was racist, specifically against the Koreans, but if anyone can notice any appreciable difference betweeen the film and TV show on that count, I'd love to hear the argument. One of the biggest cheerleaders for the game is Hot Lips and if I have a problem with the film, it's the quick and inexplicable conversion of the Margaret Houlihan character. She's introduced as a no-nonsense, by-the-book Army major, constantly being humiliated by the pranksters of The Swamp (and a wonderful Oscar- nominated performance from Kellerman). When Hawkeye first meets her, always out to put the make on some new female flesh, he gives it to her for putting him off his lust and that she's just a regular Army clown and he's going back to his tent to drink scotch. Houlihan vents her outrage to the film's Father Mulcahy (Rene Auberjonois), known here as Dago Red, asking how someone so crass as Hawkeye could reach a position of responsibility in the Army. "He was drafted," the priest replies. When the gang exposes her shower and nudity to the camp, she has a breakdown to Henry, insisting that, "This is not a hospital, it's an insane asylum!" Then, before you know it, she's fooling around with Duke and playing cheerleader. It's odd, but it's still a minor criticism in an otherwise great film. (I'm just thinking off the top of my head, but has any great movie been turned into an almost equally great television show the way MASH was?)

nominated performance from Kellerman). When Hawkeye first meets her, always out to put the make on some new female flesh, he gives it to her for putting him off his lust and that she's just a regular Army clown and he's going back to his tent to drink scotch. Houlihan vents her outrage to the film's Father Mulcahy (Rene Auberjonois), known here as Dago Red, asking how someone so crass as Hawkeye could reach a position of responsibility in the Army. "He was drafted," the priest replies. When the gang exposes her shower and nudity to the camp, she has a breakdown to Henry, insisting that, "This is not a hospital, it's an insane asylum!" Then, before you know it, she's fooling around with Duke and playing cheerleader. It's odd, but it's still a minor criticism in an otherwise great film. (I'm just thinking off the top of my head, but has any great movie been turned into an almost equally great television show the way MASH was?)It doesn't hurt when it begins

But as it works its way on in

The pain grows stronger...watch it grin, but...

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

As I mentioned before, MASH is the first example of the Robert Altman ensemble that he'd become famous for and many of the actors who would become part of the unofficial Altman repertory company would make appearances here. Elliott Gould would follow his great work as Trapper John with similarly solid work in Altman's The Long Goodbye and California Split and would appear as himself in Nashville and The Player.

Skerritt returned to Altman for Thieves Like Us. Kellerman returned for Brewster McCloud and Ready to Wear and as herself in The Player. Duvall first appeared in Altman's Countdown and then reunited with him on The Gingerbread Man. Rene Auberjonois rejoined the director for Brewster McCloud, McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Images. David Arkin also appeared in The Long Goodbye, Nashville and Popeye. Last, but certainly not least, MASH marked the appearance of Michael Murphy who may have been the most regular of Altman regulars, appearing in McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville, Brewster McCloud, Kansas City, Countdown, That Cold Day in the Park, Tanner '88, Tanner on Tanner, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial and even episodes of TV's Combat, Kraft Suspense Theater and the 1964 TV movie Nightmare in Chicago. It also marked the film debut of Bud Cort who returned in Brewster McCloud. Surprisingly, the actor who gave the best performance in MASH never worked with Altman again. I always go back and forth as to whether or not Donald Sutherland's Hawkeye Pierce is lead or supporting but in either case, it is brilliant and yet another example of the outrage that this man has never received an Oscar nomination for anything. His little whistle as Hawkeye alone is a thing of wonder.

Skerritt returned to Altman for Thieves Like Us. Kellerman returned for Brewster McCloud and Ready to Wear and as herself in The Player. Duvall first appeared in Altman's Countdown and then reunited with him on The Gingerbread Man. Rene Auberjonois rejoined the director for Brewster McCloud, McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Images. David Arkin also appeared in The Long Goodbye, Nashville and Popeye. Last, but certainly not least, MASH marked the appearance of Michael Murphy who may have been the most regular of Altman regulars, appearing in McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville, Brewster McCloud, Kansas City, Countdown, That Cold Day in the Park, Tanner '88, Tanner on Tanner, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial and even episodes of TV's Combat, Kraft Suspense Theater and the 1964 TV movie Nightmare in Chicago. It also marked the film debut of Bud Cort who returned in Brewster McCloud. Surprisingly, the actor who gave the best performance in MASH never worked with Altman again. I always go back and forth as to whether or not Donald Sutherland's Hawkeye Pierce is lead or supporting but in either case, it is brilliant and yet another example of the outrage that this man has never received an Oscar nomination for anything. His little whistle as Hawkeye alone is a thing of wonder.to answer questions that are key

'is it to be or not to be'

and I replied 'oh why ask me?'

'Cause suicide is painless

it brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

...and you can do the same thing if you choose.

Alright, about that song. The painless it refers to is not just the idea that suicide is free from hurt but refers to a very specific character in MASH: Painless Pole the dentist, portrayed by another Altman regular, John

Schuck. Painless has a reputation not only as a Don Juan but as being particularly well endowed, so much so that when it's his turn in the shower, people take turns gazing upon his impressive manhood. The song opens the film but it is reprised again later when Painless, after a bout of impotence, becomes convinced that he may carry some latent homosexuality and even though he's never had any form of gay sex, he figures it's just a matter of time so he goes to Hawkeye for help for a way out. A last supper is arranged, where Painless will take the Black Capsule and commit suicide. Of course, Hawkeye has no intention of helping Painless to kill himself but instead enlists Lt. Dish (Jo Ann Pflug) to sleep with the unconscious Painless and restore his confidence. It works. There even is an instrumental, heavenly choir version of "Suicide Is Painless" to accompany the scene.

Schuck. Painless has a reputation not only as a Don Juan but as being particularly well endowed, so much so that when it's his turn in the shower, people take turns gazing upon his impressive manhood. The song opens the film but it is reprised again later when Painless, after a bout of impotence, becomes convinced that he may carry some latent homosexuality and even though he's never had any form of gay sex, he figures it's just a matter of time so he goes to Hawkeye for help for a way out. A last supper is arranged, where Painless will take the Black Capsule and commit suicide. Of course, Hawkeye has no intention of helping Painless to kill himself but instead enlists Lt. Dish (Jo Ann Pflug) to sleep with the unconscious Painless and restore his confidence. It works. There even is an instrumental, heavenly choir version of "Suicide Is Painless" to accompany the scene.Since MASH may well be the among the most plotless of Robert Altman's works (at least of the successful ones), I figured my appreciation of the film should be equally aimless, but I still had a few more things to say

and I've run out of stanzas to the song, so I'll just go with them. I love Altman's use of sound, already coming to life here, but particularly in the fun loudspeaker announcements. My personal favorite: the announcement that the American Medical Association had classified marijuana as a dangerous drug, despite previous studies that had found it no more harmful than alcohol. Also, it's worth noting that MASH did garner many Oscar nominations but in a tumultuous year such as 1970, there was no way that the stodgy Academy would go with the subversive Korean War comedy that everyone knew was really about Vietnam. (The Oscar went with the rah-rah jingoism of Patton.) MASH did manage to win adapted screenplay, which was particularly sweet, because its writer was Ring Lardner Jr., one of the most infamous victims of the Hollywood blacklist. Though Robert Altman had made features prior to MASH, truly this is the film that started the Altman canon and career and began to create the legend the late director became.

and I've run out of stanzas to the song, so I'll just go with them. I love Altman's use of sound, already coming to life here, but particularly in the fun loudspeaker announcements. My personal favorite: the announcement that the American Medical Association had classified marijuana as a dangerous drug, despite previous studies that had found it no more harmful than alcohol. Also, it's worth noting that MASH did garner many Oscar nominations but in a tumultuous year such as 1970, there was no way that the stodgy Academy would go with the subversive Korean War comedy that everyone knew was really about Vietnam. (The Oscar went with the rah-rah jingoism of Patton.) MASH did manage to win adapted screenplay, which was particularly sweet, because its writer was Ring Lardner Jr., one of the most infamous victims of the Hollywood blacklist. Though Robert Altman had made features prior to MASH, truly this is the film that started the Altman canon and career and began to create the legend the late director became.Tweet

Labels: 70s, Alda, Altman, blacklist, Bud Cort, D. Sutherland, Duvall, Gelbart, Marx Brothers, Movie Tributes, Television

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, March 04, 2008

From the Vault: Disclosure

Even worse, that climactic twist merely serves as the coup de grace of the countless unintentionally comic moments of this extremely silly adaptation of the Michael Crichton best seller about sexual harassment.

In the tradition of his work in Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct and Falling Down, Michael Douglas stars as yet another persecuted heel, only this time his characters acts even more like an irresponsible twit than usual.

Douglas plays Tom Sanders, an executive at DigiCom, a Seattle high-tech computer firm who finds that an ex-girlfriend, Meredith Johnson (Demi Moore) has been given the promotion he feels he deserves. On her first day on the job, Meredith invites Tom to her office for an after-hours drink and brain-storming session.

Once there, Tom realizes Meredith isn't interested in his mind but wants to engage in some carnal nostalgia. At first, Tom seems powerless to resist, despite his happy marriage to a lawyer (Caroline Goodall) and two children. After repeated shouts of "No," Tom gets away and Meredith vows corporate vengeance.

When Tom learns Meredith has lied to their boss (played by an entertaining Donald Sutherland) and claims that Tom came on to her, Tom forces her hand by filing a sexual harassment suit of his own.

The rest of the film revolves around the legal and corporate maneuvering between both sides, all of which takes place in the space of a single work week. Thanks to Barry Levinson's draggy pacing, it seems more like an eternity.

The few moments of wit in Paul Attanasio's script and provided by the supporting players make this would-be topical exercise watchable, but too often the dialogue drifts into platitudes. It's a disappointment from the screenwriter who gave us the sharp and witty Quiz Show.

When Tom muses to his wife that he fears becoming another "ghost with a resume," you realize that lines that might work as prose sink like a stone when they come out of the mouth of an actor like Douglas.

In fact, Douglas ends up being the film's biggest negative. His intrinsic unlikability as an actor makes Tom a shrill buffoon. Despite the fact that Tom's right, you still want to see him kicked around a bit.

Moore does OK by her part, bringing the necessary mix of vivaciousness and venom to Meredith, but she's as much a cartoon as Douglas' character. Their names should be Tom and Jerry instead of Tom and Meredith.

No moment makes more clear how wrong this movie goes than the virtual reality sequence. Leaving aside the fact that a virtual reality file room defeats the purpose of having a database at your fingertips and makes the information age more cumbersome not less, the sequence evokes laughs by its ridiculous setup.

Tom breaks into the hotel room of the CEO of a company planning to merge with DigiCom, where the virtual file room prototype has been assembled for the corporate bigwig to play with. As Tom nervously searches for the papers he needs, Meredith logs on at the office and becomes represented by Demi Moore's head on a Lawnmower Man-type graphic body. It looks even sillier than it sounds.

Sexual harassment could be a fascinating topic for a movie, but Disclosure is not that film. At times it looks as if it might take a detour into satire or suspense, but both avenues prove to be dead ends.

In the end, the virtual reality subplot seems an apt metaphor for this misfire. Occasionally you get the sensation of being in on the action but when you remove the goggles, you find yourself back in the real world.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, B. Levinson, D. Sutherland, M. Douglas

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE