Thursday, October 10, 2013

Better Off Ted: Bye Bye 'Bad' Part III

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now. If you missed Part I, click here. If you missed Part II, click here.

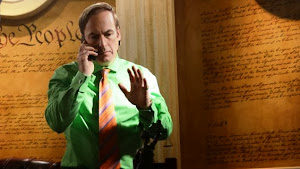

— Saul Goodman to Mike Ehrmantraut ("Buyout," written by Gennifer Hutchison, directed by Colin Bucksey)

By Edward Copeland

Playing to the back of the room: I love doing it as a writer and appreciate it even more as an audience member. While I understand how its origin in comedy clubs gives it a derogatory meaning, I say phooey in general. Another example of playing to the broadest, widest audience possible. Why not reward those knowledgeable ones who pay close attention? Why cater to the Michele Bachmanns of the world who believe that ignorance is bliss? What they don’t catch can’t hurt them. I know I’ve fought with many an editor about references that they didn’t get or feared would fly over most readers’ heads (and I’ve known other writers who suffered the same problems, including one told by an editor decades younger that she needed to explain further whom she meant when she mentioned Tracy and Hepburn in a review. Being a free-lancer with a real full-time job, she quit on the spot). Breaking Bad certainly didn’t invent the concept, but damn the show did it well — sneaking some past me the first time or two, those clever bastards, not only within dialogue, but visually as well. In that spirit, I don’t plan to explain all the little gems I'll discuss. Consider them chocolate treats for those in the know. Sam, release the falcon!

In a separate discussion on Facebook, I agreed with a friend at taking offense when referring to Breaking Bad as a crime show. In fact, I responded:

“I think Breaking Bad is the greatest dramatic series TV has yet produced, but I agree. Calling it a ‘crime show’ is an example of trying to pin every show or movie into a particular genre hole when, especially in the case of Breaking Bad, it has so many more layers than merely crime. In fact, I don't like the fact that I just referred to it as a drama series because, as disturbing, tragic and horrifying as Breaking Bad could be, it also could be hysterically funny. That humor also came in shapes and sizes across the spectrum of humor. Vince Gilligan's creation amazes me in a new way every time I think about it. I wonder how long I'll still find myself discovering new nuances or aspects to it. I imagine it's going to be like Airplane! — where I still found myself discovering gags I hadn't caught years and countless viewings after my initial one as an 11-year-old in 1980. Truth be told, I can't guarantee I have caught all that ZAZ placed in Airplane! yet even now. Can it be a mere coincidence that both Breaking Bad and Airplane! featured Jonathan Banks? Surely I can't be serious, but if I am, tread lightly.”

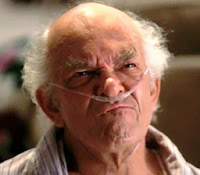

— Jonathan Banks as air traffic controller Gunderson in Airplane!

The second season episode “ABQ” (written by Vince Gilligan, directed by Adam Bernstein) introduced us to Banks as Mike and also featured John de Lancie as air traffic controller Donald Margulies, father of the doomed Jane. Listen to the DVD commentary about a previous time that Banks and De Lancie worked together. Speaking of air traffic controllers, if you don’t already know, look up how a real man named Walter White figured in an airline disaster. Remember Wayfarer 515! Saul never did, wearing that ribbon nearly constantly. Most realize the surreal pre-credit scenes that season foretold that ending cataclysm and where six of its second season episode titles, when placed together in the correct order, spell out the news of the disaster. Breaking Bad’s knack for its equivalent of DVD Easter eggs extended to episode titles, which most viewers never knew unless they looked them up. Speaking of Saul Goodman, he provided the voice for a multitude of Breaking Bad’s pop culture references from the moment the show introduced his character in season two’s “Better Call Saul” (written by Peter Gould, directed by Terry McDonough). Once he figures out (and it doesn’t take long) that Walt isn’t really Jesse’s uncle and pays him a visit in his high school classroom, the attorney and his client discuss a more specific role

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.

players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.As I admitted, some of the nice touches escaped my notice until pointed out to me later. Two of the most obvious examples occurred in the final eight episodes. One wasn’t so much a reference as a callback to the very first episode that you’d need a sharp eye to spot. It occurs in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson) and I’d probably never noticed if not for a synched-up commentary track that Johnson did for the episode on The Ones Who Knock weekly podcast on Breaking Bad. He pointed out that as Walt rolls his barrel of $11 million through the desert (itself drawing echoes to Erich von Stroheim’s silent classic Greed and its lead character McTeague — that one I had caught) he passes the pair of pants he lost in the very first episode when they flew through the air as he frantically drove the RV with the presumed dead Krazy-8 and Emilio unconscious in the back. Check the still below, enlarged enough so you don’t miss the long lost trousers.

The other came when psycho Todd decided to give his meth cook prisoner Jesse ice cream as a reward. I wasn’t listening closely enough when he named one of the flavor choices as Ben & Jerry’s Americone Dream, and even if I’d heard the flavor’s name, I would have missed the joke until Stephen Colbert, whose name serves as a possessive prefix for the treat’s flavor, did an entire routine on The Colbert Report about the use of the ice cream named for him giving Jesse the strength to make an escape attempt. One hidden treasure I did not know concerned the appearance of the great Robert Forster as the fabled vacuum salesman who helped give people new identities for a price. Until I read it in a column on the episode “Granite State” (written and directed by Gould), I had no idea that in real life Forster once actually worked as a vacuum salesman.

Seeing so many episodes multiple times, the callbacks to previous moments in the series always impressed me. I didn’t recall until AMC held its marathon prior to the finale and I caught the scene where Skyler caught Ted about him cooking his company’s books in season two’s “Mandala” (written by Mastras, directed by Adam Bernstein),

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.I wanted this tribute to be so much grander and better organized, but my physical condition thwarted my ambitions. I doubt seriously my hands shall allow me to complete a fourth installment. (If you did miss Part I or Part II, follow those links.) While I hate ending on a patter list akin to a certain Billy Joel song, (I let you off easy. I almost referenced Jonathan Larson — and I considered narrowing the circle tighter by namedropping Gerome Ragni

& James Rado.) I feel I must to sing my hosannas to the actors, writers, directors and other artists who collaborated to realize the greatest hour-long series in

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

In fact, the series failed me only twice. No. 1: How can you dump the idea that Gus Fring had a particularly mysterious identity in the episode “Hermanos” and never get back to it? No. 2: That great-looking barrel-shaped box set of the entire series only will be made on Blu-ray. As someone of limited means, it would need to be a Christmas gift anyway and for the same reason, I never made the move to Blu-ray and remain with DVD. Medical bills will do that to you and, even if tempting or plausible, it’s difficult to start a meth business to fund it while bedridden. Despite those two disappointments, it doesn’t change Breaking Bad’s place in my heart as the best TV achievement so far. How do I know this? Because I say so.

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Cranston, D. Zucker, De Palma, Deadwood, Hackman, Hawks, HBO, J. Zucker, Jim Abrahams, K. Hepburn, O'Toole, Oliver Stone, Tracy, Treme, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, May 07, 2012

Love Story

— Orson Welles on Make Way for Tomorrow

By John Cochrane

No one film dominated the 1937 Academy Awards, but with the country still in the grips of the Great Depression and slowly realizing Europe’s inevitable march back into war, the subtle theme of the evening in early 1938 seemed to be distant escapism — anything to help people forget the troubled times at home. The Life of Emile Zola, a period biopic set in France, won best picture. Spencer Tracy received his first best actor Oscar, playing a Portuguese sailor in Captains Courageous, and Luise Rainer was named best actress for a second year in a row, playing the wife of a struggling Chinese farmer in the morality tale The Good Earth.

Best director that year went to Hollywood veteran Leo McCarey for The Awful Truth. McCarey’s resume was impressive. He paired Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy together as a team, and he had directed, supervised or helped write much of their best silent work. He had collaborated with W.C. Fields, Charley Chase, Eddie Cantor, Mae West, Harold Lloyd, George Burns and Gracie Allen — almost an early Hollywood Comedy Hall of Fame. He had also directed the Marx Brothers in the freewheeling political satire Duck Soup (1933) — generally now considered their best film. The Awful Truth was a screwball comedy about an affluent couple whose romantic chemistry constantly sabotages their impending divorce that starred Irene Dunne, Ralph Bellamy — and a breakout performance by a handsome leading man named Cary Grant — who supposedly had based a lot of his on-screen persona on the personality of his witty and elegant director. Addressing the Academy, the affable McCarey said “Thank you for this wonderful award. But you gave it to me for the wrong picture.”

The picture that McCarey was referring to was his earlier production from 1937, titled Make Way for Tomorrow — an often tough and unsentimental drama about an elderly couple who loses their home to foreclosure and must separate when none of their children are able or willing to take them both in. The film opened to stellar reviews and promptly died at the box office — being unknown to most people for decades. Fortunately, recent events have begun to rectify this oversight as this buried American cinematic gem turns 75 years old.

Based on Josephine Lawrence’s novel The Years Are So Long, the film opens at the cozy home of Barkley and Lucy Cooper (Victor Moore, Beulah Bondi), who have been married for 50 years. Four of their five children have arrived for what they believe will be a joyous family dinner — until Bark breaks the news that he hasn’t been able to keep up with the

mortgage payments since being out of work and that the bank will repossess the property within days. Bark and Lucy insist that they will stay together, regardless of what happens. With little time to plan, the family decides that, for the time being, Lucy will move to New York to live with their eldest son George’s family in their apartment, while Bark will be 360 miles away — sleeping on the couch at the home of their daughter Cora (Elisabeth Risdon) and her unemployed husband Bill (Ralph Remley). For the film's first hour or so, we see Bark and Lucy trying to adjust to their new surroundings. While George (an excellent Thomas Mitchell) tries to be as pleasant and accommodating to his mother as possible, his wife Anita (Fay Bainter) and daughter Rhoda (Barbara Read) display little patience and dislike the disruption of their routines. Meanwhile, Bark spends his time walking around his new hometown, looking for a job and visiting a new friend, a local shopkeeper named Max Rubens (Maurice Moscowitz).

mortgage payments since being out of work and that the bank will repossess the property within days. Bark and Lucy insist that they will stay together, regardless of what happens. With little time to plan, the family decides that, for the time being, Lucy will move to New York to live with their eldest son George’s family in their apartment, while Bark will be 360 miles away — sleeping on the couch at the home of their daughter Cora (Elisabeth Risdon) and her unemployed husband Bill (Ralph Remley). For the film's first hour or so, we see Bark and Lucy trying to adjust to their new surroundings. While George (an excellent Thomas Mitchell) tries to be as pleasant and accommodating to his mother as possible, his wife Anita (Fay Bainter) and daughter Rhoda (Barbara Read) display little patience and dislike the disruption of their routines. Meanwhile, Bark spends his time walking around his new hometown, looking for a job and visiting a new friend, a local shopkeeper named Max Rubens (Maurice Moscowitz).Many filmmakers develop a visual signature that dominates their work, but McCarey employs a fairly basic and straightforward style, using group and reaction shots as well as perceptive editing that places the emphasis on the actors and the story. Working with screenwriter Vina Delmar, McCarey creates set pieces that blend touches of light comedy and everyday drama that feel so correct and truthful that audiences likely feel a sometimes uncomfortable recognition with them. Often, this stems from McCarey's use of improvisation to sharpen his scenes before filming them. If short on ideas, he would play a nearby piano on the set until he figured out what to do. This practice creates a freshness that, as Peter Bogdanovich points out, gives the impression that what you’re watching wasn't planned but just happened. A large part of the film’s greatness also comes from the cast, headed by Moore and Bondi as Bark and Lucy. Both theatrically trained actors, vaudeville star Moore (age 61) and future Emmy winner Bondi (age 48), through the wonders of make-up and black and white photography prove completely convincing as an elderly couple in their 70s.

Moore performs terrifically as the blunt, but loving Bark. Bondi gives an even better turn as Lucy. In one scene, representative of McCarey’s direction and Bondi’s performance, Lucy inadvertently interrupts a bridge-playing class being taught by her daughter-in-law at the apartment by making small talk and noticing the cards in players’ hands. She’s an intrusion, but by the end of the evening, after being abandoned by her granddaughter at the movies and returning home, she takes a phone call in the living room from her husband. Critic Gary Giddins notes that as the class listens in to her side of the conversation, she becomes highly sympathetic — and the scene now flips with the card students visibly moved and feeling invasive of her space and privacy. Then there’s the crucial scene where Lucy sees the writing on the wall and offers to move out of the apartment and into a nursing home without Bark’s knowledge, before her family can commit her — so as not to be a burden to them anymore. She shares a loving moment with her guilt-ridden son George. (“You were always my favorite child,” she sincerely tells him.) His disappointment in himself in the scene’s coda resonates deeply. Lucy’s character seems meek and easily taken advantage of when we first meet her, but she’s really the strongest person in the story. It’s her love and sacrifice for her husband and family that give the movie much of its emotional weight, and the unforgettable final shot belongs to her.

McCarey and Delmar create totally believable characters and it should be pointed out that while friendly, decent people, Bark and Lucy, by no means, lack flaws. Bark doesn't make a particularly good patient when sick in bed two-thirds of the way through the story, and Lucy stands firm in her ways and beliefs — traits that can annoy, but people can be that way. Even the children aren’t bad — they have reasons that the audience can understand — even if we don’t agree with their often seemingly selfish or preoccupied behavior. This delicate skill of observation was not lost on McCarey’s good friend, the great French director Jean Renoir, who once said, “McCarey understands people better than anyone in Hollywood.”

As memorable a first hour as Make Way for Tomorrow delivers, McCarey saves the best moments for the film’s third act. Bark and Lucy meet one last time in New York, hours before his train departure for California to live with their unseen daughter Addie for health reasons. For the first time since the opening scene, the couple finally reunites. The last 20 minutes of the picture overflows with what Roger Ebert refers to in his Great Movies essay on the film as mono no aware — which roughly translated means “a bittersweet sadness at the passing of all things.” Regrets, but nothing that Bark and Lucy really would change if they had to do everything over again.

Throughout the story, the Coopers often have been humiliated or brushed off by their children. When a car salesman (Dell Henderson) mistakes them for a wealthy couple and takes them for a ride in a fancy car, the audience cringes — expecting another uncomfortable moment — but then something interesting happens. As they arrive at their destination and an embarrassed Bark and Lucy explain that there’s been a misunderstanding, the salesman tactfully assuages their concerns. He allows them to save face, by saying his pride in the car made him want to show it off. Walking into The Vogard Hotel where they honeymooned 50 years ago, the Coopers get treated like friends or VIPs — first by a hat check girl (Louise Seidel) and then by the hotel manager (Paul Stanton), who happily takes his time talking to them and comps their bar tab. Bark and Lucy's children expect their parents at George’s apartment for dinner, but Bark phones them to say that they won't be coming.

At one point, we see the couple from behind as they sit together, sharing a loving moment of intimate conversation. As Lucy leans toward her husband to kiss him, she seems to notice the camera and demurely stops herself from such a public display of affection. It’s an extraordinary sequence that’s followed by another one when Bark and Lucy get up to dance. As they arrive on the dance floor, the orchestra breaks into a rumba and the Coopers seem lost and out of place. The watchful bandleader notices them, without a word, quickly instructs the musicians to switch to the love song “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.” Bark gratefully acknowledges the conductor as he waltzes Lucy around the room. Then the clock strikes 9, and Bark and Lucy rush off to the train station for the film’s closing scene.

Paramount studio head Adolph Zukor reportedly visited the set several times, pleading with his producer-director to change the ending, but McCarey — who saw the movie as a labor of love and a personal tribute to his recently deceased father — wouldn’t budge. The film was released to rave reviews, though at least one reviewer couldn’t recommend it because it would “ruin your day.” Industry friends and colleagues such as John Ford and Frank Capra were deeply impressed. McCarey even received an enthusiastic letter from legendary British playwright George Bernard Shaw, but the Paramount marketing department didn’t know what to do with the picture. Audiences, still facing a tough economy, didn’t want to see a movie about losing your home and being marginalized in old age. They stayed away, while the Motion Picture Academy didn’t seem to notice. McCarey was fired from his contract at Paramount (later rebounding that year at Columbia with the unqualified success of The Awful Truth), and the film seemed to disappear from view for many years.

The movie never was forgotten completely though. Screenwriter Kogo Noda, who wrote frequently with the great Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu, saw the film and used it as an inspiration for Ozu’s masterpiece Tokyo Story (1953), in which an elderly couple journey to the big city to visit their adult children and quietly realize that their offspring don’t have time for them in their busy lives — only temporarily getting their full attention when one of the parents unexpectedly dies during the trip home. Ironically, Ozu’s film also would be unknown to most of the world for decades, until exported in the early 1970s, almost 10 years after the master filmmaker’s death. Tokyo Story, with its sublime simplicity and quiet insight into human nature now is considered by many critics and filmmakers to be one of the greatest movies ever made — placing high in the Sight & Sound polls of 1992 and 2002. In the meantime, Make Way for Tomorrow slowly started getting more attention in its own right, probably sometime in the mid- to late 1960s. Although the movie never was released on VHS, it occasionally was shown enough on television to garner a devoted underground following. More recently, the movie played at the Telluride Film Festival, where audiences at sold out screenings were stunned by its undeniable quality and its powerful, timeless message. Make Way for Tomorrow was finally was released on DVD by The Criterion Collection and was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress on the National Film Registry in 2010.

The funny phenomenon of how audiences in general dislike unhappy endings, and yet somehow our psyches depend on them always proves puzzling. Classics such as Casablanca (1942), Vertigo (1958), The Third Man (1949 U.K.; 1950 U.S.) and even the fictional romance in a more contemporary hit such as Titanic (1997) wouldn't carry the same stature or mystique in popular culture if they somehow had been pleasantly resolved. Life often disappoints and turns out unpredictably, messy and frequently filled with loss. Even though many people claim they don’t like sad stories, it comforts somehow to know that we aren’t alone — that others understand and feel similarly as we do about life’s experiences. It’s what makes us human.

Make Way for Tomorrow serves as many things. It’s a movie about family dynamics and the Fifth Commandment. Gary Giddins points out that it’s also a message film about the need for a safety net such as Social Security — which hadn't been fully implemented when the

picture was released. It’s a plea for treating each other with more kindness — in a culture that increasingly pushes the old aside to embrace the young and the new, and it’s one of the saddest movies ever made. At its most basic level, it’s a tender love story between two people who have spent most of their lives together — knowing each other so well that words often seem unnecessary. However you choose to look at it, Make Way for Tomorrow remains one of the greatest American films — certainly a strong contender for the best classic Hollywood movie that most people have never heard of. Leo McCarey would create highly successful hits that were more sentimental later on in his career — including the enjoyable romance Love Affair (1939) and its subsequent color remake An Affair to Remember (1957), starring Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr. He also would direct Bing Crosby as a charismatic priest in 1944’s Going My Way (7 Oscars — including picture, director, actor) and its superior sequel, 1945’s The Bells of St. Mary’s (8 nominations, 1 win), co-starring Ingrid Bergman, but he never forgot about Make Way for Tomorrow, which remained a personal favorite until the day he died from emphysema in 1969. Leo McCarey did not live to see his masterpiece fully appreciated, but that wasn't necessary. In 1938, he knew the film’s value.

picture was released. It’s a plea for treating each other with more kindness — in a culture that increasingly pushes the old aside to embrace the young and the new, and it’s one of the saddest movies ever made. At its most basic level, it’s a tender love story between two people who have spent most of their lives together — knowing each other so well that words often seem unnecessary. However you choose to look at it, Make Way for Tomorrow remains one of the greatest American films — certainly a strong contender for the best classic Hollywood movie that most people have never heard of. Leo McCarey would create highly successful hits that were more sentimental later on in his career — including the enjoyable romance Love Affair (1939) and its subsequent color remake An Affair to Remember (1957), starring Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr. He also would direct Bing Crosby as a charismatic priest in 1944’s Going My Way (7 Oscars — including picture, director, actor) and its superior sequel, 1945’s The Bells of St. Mary’s (8 nominations, 1 win), co-starring Ingrid Bergman, but he never forgot about Make Way for Tomorrow, which remained a personal favorite until the day he died from emphysema in 1969. Leo McCarey did not live to see his masterpiece fully appreciated, but that wasn't necessary. In 1938, he knew the film’s value.It’s a marvelous picture. Bring plenty of Kleenex.

Tweet

Labels: 30s, Bellamy, Bogdanovich, Capra, Cary, Deborah Kerr, Ebert, Fields, Ingrid Bergman, Irene Dunne, John Ford, Luise Rainer, Marx Brothers, McCarey, Movie Tributes, Oscars, Renoir, T. Mitchell, Tracy, Welles

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, October 22, 2011

"A person can't sneeze in this town without someone offering them a handkerchief"

How come you treat me like a worn-out shoe?

My hair's still curly and my eyes are still blue

Why don't you love me like you used to do?

•••

Well, why don't you be just like you used to be?

How come you find so many faults with me?

Somebody's changed so let me give you a clue

Why don't you love me like you used to do?

By Edward Copeland

Even if Hank Williams Sr. weren't well represented with songs that play throughout Peter Bogdanovich's film adaptation of Larry McMurtry's novel The Last Picture Show, somehow I think the movie would play as if it were a cinematic evocation of the music legend. Despite the fact that today marks the 40th anniversary of the film's release and The Last Picture Show took as its setting a small, depressed Texas town in 1951 and 1952 (even going so far as to have cinematographer Robert Surtees shoot it in glorious black & white), it contains a universality that resonates today both in human and economic terms. Williams' hit "Why Don't You Love Me (Like You Used to Do)?" that I quote partially above are the first words we hear, before any character speaks a line. In the movie's context, the lyrics could be describing the first person we see — high school senior Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms). With the way the U.S. has been going of late, I know very few people who don't feel like a "worn-out shoe" and wish fondly for past, better days and these feelings stretch from one end of the ideological spectrum to the other. Fortunately, The Last Picture Show itself hasn't changed. Age has served the film well, helped in no small part by its amazing cast.

McMurtry, who based the town in the novel on his own small north Texas hometown of Archer City, co-wrote the screenplay with Bogdanovich, the former film critic who was directing his second credited feature film after the fun and tawdry thriller Targets that gave Boris Karloff a great, late career role. (Under the name Derek Thomas, he had filmed a sci-fi feature called Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women in 1968 starring Mamie Van Doren.) In the novel, McMurtry renamed the town Thalia, but the film gave it another moniker — Anarene.

The movie opens on Anarene's main stretch of road and passes the Royal movie theater. The wind howls ferociously, blowing dust, leaves, trash and anything that isn't tied down through the air and down the street. The flying debris leads us to Sonny and that Hank Williams song, which comes from the radio of his old pickup that he's having a helluva time getting started. Actually, the pickup only half belongs to

Sonny — he shares it with his best friend Duane Moore (Jeff Bridges), who always seems to get it first on date nights so he can neck with his girlfriend, Jacy Farrow (Cybill Shepherd in her film debut), widely considered the best-looking teen in town. Once Sonny gets that old pickup running, he spots young Billy (the late Sam Bottoms, Timothy's real-life younger brother) standing in the middle of the street with his broom, trying to sweep up the dust. Sonny honks at him and Billy smiles and climbs in the pickup with him. As he usually does, Sonny affectionately turns the mentally challenged boy's cap around backward and the two head to the pool hall owned by Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson). Sonny pays for what looks like a sticky bun and a bottle of pop, prompting Sam to shake his head. "You ain't ever gonna amount to nothing. Already spent a dime this morning, ain't even had a decent breakfast," Sam tells Sonny, but not in a mean-spirited way. "Why don't you comb you hair, Sonny? It sticks up…I'm surprised you had the nerve to show up this morning after that stomping y'all took last night." Sam's referring to Anarene High School's final football game of the year, where the team took a real beating. "It could've been worse," Sonny replies. "You could say that just about everything," Sam says.

Sonny — he shares it with his best friend Duane Moore (Jeff Bridges), who always seems to get it first on date nights so he can neck with his girlfriend, Jacy Farrow (Cybill Shepherd in her film debut), widely considered the best-looking teen in town. Once Sonny gets that old pickup running, he spots young Billy (the late Sam Bottoms, Timothy's real-life younger brother) standing in the middle of the street with his broom, trying to sweep up the dust. Sonny honks at him and Billy smiles and climbs in the pickup with him. As he usually does, Sonny affectionately turns the mentally challenged boy's cap around backward and the two head to the pool hall owned by Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson). Sonny pays for what looks like a sticky bun and a bottle of pop, prompting Sam to shake his head. "You ain't ever gonna amount to nothing. Already spent a dime this morning, ain't even had a decent breakfast," Sam tells Sonny, but not in a mean-spirited way. "Why don't you comb you hair, Sonny? It sticks up…I'm surprised you had the nerve to show up this morning after that stomping y'all took last night." Sam's referring to Anarene High School's final football game of the year, where the team took a real beating. "It could've been worse," Sonny replies. "You could say that just about everything," Sam says. "It could've been worse" applies to most of the situations in The Last Picture Show, which can be described accurately by the overused phrase "slice of life." Plot doesn't drive the story — character, not only of the people but of the town itself, does. While you watch the movie, you aren't concerned with what happens next or how the film ends because you realize that life will go on for most of these fictional folks you've come to know even after the lights come up in the theater and the projector shuts off. Wherever the movie finishes will resemble a chapter stop more than a finale. (As if to prove the point, McMurtry returned to Thalia in four more novels, though Duane becomes the main character in the followups as opposed to Sonny, who decidedly takes the lead here. Bogdanovich even filmed the first sequel, Texasville, in 1990 with mixed results.)

Sam's reference to the previous night's football debacle displays an excellent example of what captivates the citizens in a so-called "one-stoplight" town such as Amarene, as the team's players (mainly Sonny and Duane, since they are the teammates we know best) get repeatedly berated by their elders the day after the loss. A common refrain becomes variations of the question, "Have you ever heard of tackling?" That even continues when Abilene (Clu Gulager), one of the many oil-field workers who live in Amarene, when he comes straight from work to Sam's pool hall, changes clothes and takes billiards so seriously that he has his own cue stick that he keeps in a case and assembles. While he's there, he collects on a bet he had with Sam on the game. Abilene isn't faithful in most areas of his life and that's telegraphed right away when we see that he'd bet against the hometown high school football team. "You see? This is what I get for bettin' on my own hometown ballteam. I ought'a have better sense," Sam says as he forks over the cash. "Wouldn't hurt to have a better hometown," the emotionless Abilene declares. Soon enough, football will fade from the town's collective memory as they move into basketball season. While sports may be important in holding this dying town

together, we never see an actual game of any kind. The closest we come is one instance of basketball practice in the school gym. That's because high school sporting events aren't what The Last Picture Show wants to show us. It's telling a coming-of-age story — several in fact — and not all concern the teen characters in the tale. It's also about love and loss, not always in the present tense. Of course, at its core, The Last Picture Show also deals with community and by community, I mean gossip. In this small a town, very few secrets can be kept, yet at the same time its citizens seem fairly discreet about what they know and staying out of other people's business. I've never read the novel, but I can see how easily it would work in book form. There's a story that Bogdanovich, who was then married to multi-hyphenate Polly Platt, who died earlier this year, read the jacket cover of the book and didn't see a way it could work as a film until Platt outlined it for him in chronological form. She must have done a brilliant job since she not only changed Bogdanovich's mind but led him to the road where he ended up directing and co-writing one of the best films of all time. the balancing act needed to transfer The Last Picture Show to the screen would have been very tricky for anyone to pull off, but I think the reason it worked boiled down to two key elements: its look and its cast.

together, we never see an actual game of any kind. The closest we come is one instance of basketball practice in the school gym. That's because high school sporting events aren't what The Last Picture Show wants to show us. It's telling a coming-of-age story — several in fact — and not all concern the teen characters in the tale. It's also about love and loss, not always in the present tense. Of course, at its core, The Last Picture Show also deals with community and by community, I mean gossip. In this small a town, very few secrets can be kept, yet at the same time its citizens seem fairly discreet about what they know and staying out of other people's business. I've never read the novel, but I can see how easily it would work in book form. There's a story that Bogdanovich, who was then married to multi-hyphenate Polly Platt, who died earlier this year, read the jacket cover of the book and didn't see a way it could work as a film until Platt outlined it for him in chronological form. She must have done a brilliant job since she not only changed Bogdanovich's mind but led him to the road where he ended up directing and co-writing one of the best films of all time. the balancing act needed to transfer The Last Picture Show to the screen would have been very tricky for anyone to pull off, but I think the reason it worked boiled down to two key elements: its look and its cast.Platt, in addition to being the person who gave Bogdanovich the vision to turn McMurtry's novel into a feature film also served as the film's production designer and its uncredited costume designer, seamlessly taking the actors and Archer City, Texas, back in time nearly 20 years. Her work was helped in no small part by the legendary director of photography Robert Surtees' exquisite black & white images, which earned one of The Last Picture Show's eight Oscar nominations. Surtees received a total of 15 Oscar nominations for

cinematography in his career and won three: for King Solomon's Mines, The Bad and the Beautiful and Ben-Hur. He actually lost twice in 1971 — he was nominated for Summer of '42 as well as The Last Picture Show. He earned four consecutive nominations from 1975-78, when he made his last film before he retired. Other nominations included The Sting, The Graduate and Oklahoma! He showed a strong gift for using both color and black & white and his stark look in The Last Picture Show perfectly captured the time and place of the setting without letting any nostalgia sneak into the proceedings, which it really shouldn't. No one is looking back at the events from the future, so that element shouldn't be there. In a way, it's interesting to compare it to George Lucas' American Graffiti two years later. Both films look at high school seniors and eschew musical scores in favor of soundtracks full of the pop hits of the era. The difference is that Graffiti, while good, revels in a "good old days" spirit with barely a mention of sexual curiosity let alone activity while The Last Picture Show depicts an entirely different economic class that's having very few good times, but certainly getting drunk and laid. Of course, adults didn't exist in Graffiti whereas their roles prove integral in The Last Picture Show. Admittedly, I haven't seen American Graffiti in some time — Lucas hasn't re-edited it to make the drag race CGI and digitally replaced all the cars out cruising with hybrids, has he?

cinematography in his career and won three: for King Solomon's Mines, The Bad and the Beautiful and Ben-Hur. He actually lost twice in 1971 — he was nominated for Summer of '42 as well as The Last Picture Show. He earned four consecutive nominations from 1975-78, when he made his last film before he retired. Other nominations included The Sting, The Graduate and Oklahoma! He showed a strong gift for using both color and black & white and his stark look in The Last Picture Show perfectly captured the time and place of the setting without letting any nostalgia sneak into the proceedings, which it really shouldn't. No one is looking back at the events from the future, so that element shouldn't be there. In a way, it's interesting to compare it to George Lucas' American Graffiti two years later. Both films look at high school seniors and eschew musical scores in favor of soundtracks full of the pop hits of the era. The difference is that Graffiti, while good, revels in a "good old days" spirit with barely a mention of sexual curiosity let alone activity while The Last Picture Show depicts an entirely different economic class that's having very few good times, but certainly getting drunk and laid. Of course, adults didn't exist in Graffiti whereas their roles prove integral in The Last Picture Show. Admittedly, I haven't seen American Graffiti in some time — Lucas hasn't re-edited it to make the drag race CGI and digitally replaced all the cars out cruising with hybrids, has he?

Despite the film's ensemble nature, Sonny truly serves as the center of this movie's universe. Timothy Bottoms wears such deep, soulful eyes that it made him a natural to play a role that required deadpan humor as well heartbreaking drama. While the other younger cast members mostly continue to flourish in the industry if we can still count Randy Quaid, who made his film debut as Lester Marlow, a rich kid from Wichita Falls who lures Shepherd's Jacy to a nude swimming party, but has now transformed himself from a talented character actor into a fugitive from justice on the run with his wife and being pursued by Dog the Bounty Hunter), Bottoms' star never seemed to take off after such a promising start. The Last Picture Show was his second feature following Dalton Trumbo's Johnny Got His Gun and in 1973 he starred in The Paper Chase, but it has been mostly TV. low budget movies and downhill since then. (I suppose his most recent highlight was playing the title character in Trey Parker and Matt Stone's short-lived Comedy Central sitcom That's My Bush!) It's a shame because he's the key to so much of The Last Picture Show. Of those eight Oscar nominations that I mentioned it received, four went to acting and two won. All were much deserved, but Bottoms deserved a slot as well. I didn't add it up, but I imagine he appears in a great majority of the movie's scenes and a case could have easily been made for pushing him for lead — not that he stood a chance to win against Gene Hackman in The French Connection, but I would have nominated him before Walter Matthau in Kotch, George C. Scott in The Hospital or Topol in Fiddler on the Roof. However, I don't know if I could have evicted Peter Finch in Sunday Bloody Sunday for him.

Bottoms' Sonny though really serves as the line upon which so much of the movie's clothing hangs to dry. He's the first character we meet, introducing us to Billy, whose origin never gets explained, and more importantly Johnson's Oscar-winning Sam the Lion, who not only owns the pool hall but the diner and the Royal movie theater as well. Sonny takes us to the Royal for the first time, arriving late because of his delivery job. Miss Mosey (Jessie Lee Fulton), the kindly manager of the place who never has popcorn since she long ago forgot how the machine worked, tells Sonny that he already missed the newsreel and the comedy and the feature has started, so she only charges him 30 cents for admission. Imagine being able to see a movie for that cheap — and I imagine it wasn't that much more to get two movies and a newsreel, Now, the prices go up and up and up while, in general, the quality goes down further and

further. Once inside, he hooks up with his girlfriend Charlene Duggs (Sharon Taggart), who gets annoyed that he doesn't realize what an important day it is. It seems it's their one-year anniversary of going steady. With that perfect deadpan aplomb I mentioned earlier, Bottoms as Sonny simply says, "Seems longer." The main feature playing that night is Father of the Bride starring Spencer Tracy and Elizabeth Taylor. Though Sonny and Charlene have relocated to the back row so they can make out, it's clear that Sonny finds the giant image of Liz Taylor more alluring than the girl who is kissing him, While we met Duane earlier when he got off work from the oil field and went to the diner with Sonny, he and Jacy show up and take the seats in front of them and it's clear that Duane finds it very satisfying to be kissing Jacy because they don't seem to be watching the movie at all. When the movie is over and all the kids exit, they tell Miss Mosey they enjoyed it, but I bet they wouldn't want to take a quiz on it. However, that wind still howls giving the older woman trouble putting up the poster for the next attraction so Sam gives her a hand teasing the return of Sands of Iwo Jima starring John Wayne. The town can boast having a movie theater, but it certainly isn't first run. After the show, Duane lets Sonny have the pickup, so he drives Charlene out by the lake and they begin to make out. You can tell this is a choreographed routine for the teens because Charlene immediately unhooks her bra and hangs it from the rearview mirror, which is followed immediately by Sonny's hands going to her bare breasts as if they were magnets and her chest was built out of metal. Charlene complains that something's wrong

further. Once inside, he hooks up with his girlfriend Charlene Duggs (Sharon Taggart), who gets annoyed that he doesn't realize what an important day it is. It seems it's their one-year anniversary of going steady. With that perfect deadpan aplomb I mentioned earlier, Bottoms as Sonny simply says, "Seems longer." The main feature playing that night is Father of the Bride starring Spencer Tracy and Elizabeth Taylor. Though Sonny and Charlene have relocated to the back row so they can make out, it's clear that Sonny finds the giant image of Liz Taylor more alluring than the girl who is kissing him, While we met Duane earlier when he got off work from the oil field and went to the diner with Sonny, he and Jacy show up and take the seats in front of them and it's clear that Duane finds it very satisfying to be kissing Jacy because they don't seem to be watching the movie at all. When the movie is over and all the kids exit, they tell Miss Mosey they enjoyed it, but I bet they wouldn't want to take a quiz on it. However, that wind still howls giving the older woman trouble putting up the poster for the next attraction so Sam gives her a hand teasing the return of Sands of Iwo Jima starring John Wayne. The town can boast having a movie theater, but it certainly isn't first run. After the show, Duane lets Sonny have the pickup, so he drives Charlene out by the lake and they begin to make out. You can tell this is a choreographed routine for the teens because Charlene immediately unhooks her bra and hangs it from the rearview mirror, which is followed immediately by Sonny's hands going to her bare breasts as if they were magnets and her chest was built out of metal. Charlene complains that something's wrong with Sonny — that he's acting as if he's bored or would rather be somewhere else. However, when Sonny does venture to place his hand somewhere else, Charlene goes nuts. "You cheapskate — you didn't even get me an anniversary present. Now, you want to get me pregnant," she barks as she starts to put her top back on. Sonny argues that it was only his hand, but she says she knows how one thing leads to another and she's waiting until she gets married. Sonny, a hangdog expression on his face, tells her that they should break up then. This shocks Charlene, but she gets mad, not upset. "Now don't go tellin' all the boys how hot I was," she warns him. "You wasn't that hot," Sonny sighs sadly in a monotone. He can't decide if he's depressed or relieved to be rid of Charlene when he shows up at the diner and tells the ever faithful manager/waitress Genevieve (the great Eileen Brennan) about it. "Jacy's the only pretty girl in town and Duane's got her," Sonny tells her. "Jacy will bring you more misery than she'll ever be worth," Genevieve declares. What a font of wisdom her character will turn out to be. Sonny remembers hearing the news that Genevieve's husband Dan finally is able to return to work, so he figures that means she won't be working much longer. In another moment from a 1971 film set in 1951 that could be taking place in 2011, she responds, "We've got four thousand dollars in doctor bills to pay. I'll probably be making cheeseburgers for your grandkids." If the bills are that high in 1951, calculate them now.

with Sonny — that he's acting as if he's bored or would rather be somewhere else. However, when Sonny does venture to place his hand somewhere else, Charlene goes nuts. "You cheapskate — you didn't even get me an anniversary present. Now, you want to get me pregnant," she barks as she starts to put her top back on. Sonny argues that it was only his hand, but she says she knows how one thing leads to another and she's waiting until she gets married. Sonny, a hangdog expression on his face, tells her that they should break up then. This shocks Charlene, but she gets mad, not upset. "Now don't go tellin' all the boys how hot I was," she warns him. "You wasn't that hot," Sonny sighs sadly in a monotone. He can't decide if he's depressed or relieved to be rid of Charlene when he shows up at the diner and tells the ever faithful manager/waitress Genevieve (the great Eileen Brennan) about it. "Jacy's the only pretty girl in town and Duane's got her," Sonny tells her. "Jacy will bring you more misery than she'll ever be worth," Genevieve declares. What a font of wisdom her character will turn out to be. Sonny remembers hearing the news that Genevieve's husband Dan finally is able to return to work, so he figures that means she won't be working much longer. In another moment from a 1971 film set in 1951 that could be taking place in 2011, she responds, "We've got four thousand dollars in doctor bills to pay. I'll probably be making cheeseburgers for your grandkids." If the bills are that high in 1951, calculate them now.

You will have to forgive me for saying so much — I have an unfortunate tendency to ramble about films I love — but I also needed to get you to this point so we could talk about the most important part of film dealing with Sonny, something that begins with doing a simple favor for Coach Popper (Bill Thurman). The coach asks Sonny if he will drive his wife Ruth (Cloris Leachman in her Oscar-winning performance) to her doctor's appointment. In exchange, he'll get Sonny out of physics lab. Sonny will take any excuse to get out of that class so he agrees. Mrs. Popper is surprised when Sonny shows up at her door — her husband didn't tell her that he wasn't taking her. It's all quiet and above board on that trip. However, when Sonny sees her again at the town's sad Christmas dance, she asks him if he could help her take out the trash from the refreshment stand. He does and the two share their first kiss. Ruth asks the teen if he'd be able to drive

her to the clinic again next week. "You bet!" Sonny replies. Many movies and works of fiction have told stories of affairs between older married women and younger men of high school or college age, but none have done so with as much meaning or affection as The Last Picture Show does in its depiction of Sonny and Ruth, which tosses most of those clichés out. Ruth isn't some oversexed seductress — she's a lonely, needy woman of 40 trapped in a miserable marriage. The movie doesn't spell it out directly, but in the commentary on the DVD, Bogdanovich says that Coach Popper is supposed to be gay. To me what's so stunning about Leachman's performance is that I can't think of her in any other dramatic roles. She's a comic actress extraordinaire. but she's so frighteningly good as Ruth I wonder why we never saw her explore really juicy drama. When Ruth and Sonny make love for the first time, it's such a mixture of elements when you have the overanxious boy rushing to lose his virginity while the 40-year-old married woman cries because she feared she never know that feeling again. As their affair continues, she actually seems to grow younger. Sonny also finds himself surprised to learn how many people are aware of what's going on between the two of them.

her to the clinic again next week. "You bet!" Sonny replies. Many movies and works of fiction have told stories of affairs between older married women and younger men of high school or college age, but none have done so with as much meaning or affection as The Last Picture Show does in its depiction of Sonny and Ruth, which tosses most of those clichés out. Ruth isn't some oversexed seductress — she's a lonely, needy woman of 40 trapped in a miserable marriage. The movie doesn't spell it out directly, but in the commentary on the DVD, Bogdanovich says that Coach Popper is supposed to be gay. To me what's so stunning about Leachman's performance is that I can't think of her in any other dramatic roles. She's a comic actress extraordinaire. but she's so frighteningly good as Ruth I wonder why we never saw her explore really juicy drama. When Ruth and Sonny make love for the first time, it's such a mixture of elements when you have the overanxious boy rushing to lose his virginity while the 40-year-old married woman cries because she feared she never know that feeling again. As their affair continues, she actually seems to grow younger. Sonny also finds himself surprised to learn how many people are aware of what's going on between the two of them.

As great as Leachman is, she didn't win that Oscar in a walk. Her toughest competition came from the same film. Ellen Burstyn scored her first Oscar nomination in the same category, supporting actress, for playing Lois Farrow, Jacy's mother. Burstyn always is brilliant, but she

manages to make us have sympathy for Lois at the same time we realize that her somewhat crazy ways have rubbed off on her daughter and turned her into the superficial cocktease that she is. Jacy claims she loves Duane, but her parents won't ever permit her to marry a boy like him without a future. The Farrows are one of the few well-off families in town, thanks to her husband striking oil. Not that it has saved the marriage any because Lois has been having an on again-off again affair with Abilene for quite some time. Jacy tries to convince her mother that she married her father when he wasn't rich. "I scared your daddy into getting rich, beautiful," Lois tells her daughter. Jacy insists that if Daddy could do it, so could Duane. "Not married to you. You're not scary enough," her mother replies. Later, when Lois informs Jacy about Sonny and Ruth's affair, Jacy's shocked, "She is 40 years old." Her mother quickly says, "So am I, honey. It's an itchy age." The big scenes for Burstyn (and Leachman) don't come until after other developments.

manages to make us have sympathy for Lois at the same time we realize that her somewhat crazy ways have rubbed off on her daughter and turned her into the superficial cocktease that she is. Jacy claims she loves Duane, but her parents won't ever permit her to marry a boy like him without a future. The Farrows are one of the few well-off families in town, thanks to her husband striking oil. Not that it has saved the marriage any because Lois has been having an on again-off again affair with Abilene for quite some time. Jacy tries to convince her mother that she married her father when he wasn't rich. "I scared your daddy into getting rich, beautiful," Lois tells her daughter. Jacy insists that if Daddy could do it, so could Duane. "Not married to you. You're not scary enough," her mother replies. Later, when Lois informs Jacy about Sonny and Ruth's affair, Jacy's shocked, "She is 40 years old." Her mother quickly says, "So am I, honey. It's an itchy age." The big scenes for Burstyn (and Leachman) don't come until after other developments.The fourth performer to earn an acting nod from the film was the great Jeff Bridges as Duane. It was his very first. He's good, but Duane actually isn't that large a part despite the fact he becomes the central figure in the book sequels. Duane's love for Jacy goes beyond reason. When she ditches him at the dance to go to the nude swim party in Wichita Falls, he takes it. When she finally agrees to put out,

he can't perform (though Bridges' facial expression when she exposes her breasts to him is priceless). They try again and he comes out all smiles and she cuts him down, telling him, "Oh, quit prissing. I don't think you done it right, anyway." Finally, as she ducks him more often, he leaves town to take another job elsewhere, but gives Sonny explicit orders to watch if anyone starts seeing her. One night, Abilene stops by the Farrow house to tell her dad that a well came in, but he isn't home. He ends up taking Jacy to the pool hall and having sex with her on a pool table, her hands grabbing hold of the corner pockets. After awhile, when the boy she'd been dating from Wichita Falls runs off and gets married, she pursues Sonny, who is powerless to resist, no matter how it hurts Ruth. When Duane returns and finds out that Sonny and Jacy are dating, he breaks a beer bottle against his face, injuring his eye. "Jacy's just the kind of girl that brings out the meanness in men," Genevieve tells Sonny when she sees him with the patch on his eye. Soon after, he and Jacy drive to Oklahoma to elope, only Jacy left a long detailed note so the Oklahoma state troopers detain them until her parents arrive and get the marriage annulled. Sonny rides back with Lois who tells him he's lucky they saved him from her.

he can't perform (though Bridges' facial expression when she exposes her breasts to him is priceless). They try again and he comes out all smiles and she cuts him down, telling him, "Oh, quit prissing. I don't think you done it right, anyway." Finally, as she ducks him more often, he leaves town to take another job elsewhere, but gives Sonny explicit orders to watch if anyone starts seeing her. One night, Abilene stops by the Farrow house to tell her dad that a well came in, but he isn't home. He ends up taking Jacy to the pool hall and having sex with her on a pool table, her hands grabbing hold of the corner pockets. After awhile, when the boy she'd been dating from Wichita Falls runs off and gets married, she pursues Sonny, who is powerless to resist, no matter how it hurts Ruth. When Duane returns and finds out that Sonny and Jacy are dating, he breaks a beer bottle against his face, injuring his eye. "Jacy's just the kind of girl that brings out the meanness in men," Genevieve tells Sonny when she sees him with the patch on his eye. Soon after, he and Jacy drive to Oklahoma to elope, only Jacy left a long detailed note so the Oklahoma state troopers detain them until her parents arrive and get the marriage annulled. Sonny rides back with Lois who tells him he's lucky they saved him from her.

In a way, I have saved the best for last, except it isn't really the last. If Timothy Bottoms' Sonny provides the line from which all the characters and stories dangle, Ben Johnson's Sam the Lion provides the posts that anchors his line. The story goes that Johnson didn't want to take the part because he thought it was too wordy and Bogdanovich, who had just completed a documentary on John Ford asked Ford to talk him into it. Ford reportedly asked Johnson if he wanted to be the Duke's sidekick all his life and told him that if he played the part,

he'd win the Oscar for supporting actor and that's just what happened. There are so many moments in Johnson's performance that I'd love to pick, but so I don't go on forever, I'm concentrating on one, which also happens to be my favorite part of the film. Sam takes Sonny and Billy fishing at this reservoir on land he once owned and it opens him up about the past. He talks about this crazy girl he was involved with about 20 years ago after his wife had lost her mind and his sons had died and how they always came out there. She challenged him to ride horses across the water. He didn't think they'd make it, but somehow she did it. Sonny asks why he never married her, but Sam tells him she already was married — one of those young marriages people get into that makes them miserable. He figured some day it would end, but it never did. "If she was here I'd probably be just as crazy now as I was then in about five minutes. Ain't that ridiculous? Naw, it ain't really. 'Cause being crazy about a woman like her is always the right thing to do. Being an old decrepit bag of bones, that's what's ridiculous. Gettin' old," Sam declares. What makes the whole sequence and monologue even better is the way Bogdanovich films it. He starts out in a medium shot where you can see all three characters, but as the tale grows more romantic he slowly moves the camera in on Johnson's face. As he starts to tell how they never ended up together, the camera pulls back out again.

he'd win the Oscar for supporting actor and that's just what happened. There are so many moments in Johnson's performance that I'd love to pick, but so I don't go on forever, I'm concentrating on one, which also happens to be my favorite part of the film. Sam takes Sonny and Billy fishing at this reservoir on land he once owned and it opens him up about the past. He talks about this crazy girl he was involved with about 20 years ago after his wife had lost her mind and his sons had died and how they always came out there. She challenged him to ride horses across the water. He didn't think they'd make it, but somehow she did it. Sonny asks why he never married her, but Sam tells him she already was married — one of those young marriages people get into that makes them miserable. He figured some day it would end, but it never did. "If she was here I'd probably be just as crazy now as I was then in about five minutes. Ain't that ridiculous? Naw, it ain't really. 'Cause being crazy about a woman like her is always the right thing to do. Being an old decrepit bag of bones, that's what's ridiculous. Gettin' old," Sam declares. What makes the whole sequence and monologue even better is the way Bogdanovich films it. He starts out in a medium shot where you can see all three characters, but as the tale grows more romantic he slowly moves the camera in on Johnson's face. As he starts to tell how they never ended up together, the camera pulls back out again.

The Last Picture Show has so many great moments, big and small, that I want to talk about them all but I do have to mention one final Sam moment before wrapping up Lois and Ruth. Earlier in the film, before Duane beats him up (they reconcile anyway) Duane and Sonny drown separate sorrows in sundaes at the diner when Duane decides that he just wants to get out of town — that night — at least for the weekend. He suggests to

Sonny that they go to Mexico. The two friends check their cash reserves and decide they can do it and get up and leave. Genevieve asks where they are going. "Mexico," they tell her. "Mexico?" As they drive the pickup down the street, they notice Sam sitting on the curb outside the theater. They tell him of their plans. He gives them some money, telling them that Mexico has a way of swallowing your money. Wistfully, he even says that if he were younger, he might go with them. There's something odd in the town — as if he has something else to say, but he just tells them he'll see them around and gives them a wave. Somehow though, even when you're watching The Last Picture Show for the first time, you know that will be the last time in the movie you'll see Sam. When Sonny and Duane come back, they go to the pool room and find it locked. They find that odd. They ask a man what's going on. He remembers that they've been gone so they don't know. Sam died. "Keeled over one of the snooker tables. Had a stroke," the man says. He adds the Sam left the diner to Genevieve, the theater to Miss Mosey and the pool hall to Sonny.

Sonny that they go to Mexico. The two friends check their cash reserves and decide they can do it and get up and leave. Genevieve asks where they are going. "Mexico," they tell her. "Mexico?" As they drive the pickup down the street, they notice Sam sitting on the curb outside the theater. They tell him of their plans. He gives them some money, telling them that Mexico has a way of swallowing your money. Wistfully, he even says that if he were younger, he might go with them. There's something odd in the town — as if he has something else to say, but he just tells them he'll see them around and gives them a wave. Somehow though, even when you're watching The Last Picture Show for the first time, you know that will be the last time in the movie you'll see Sam. When Sonny and Duane come back, they go to the pool room and find it locked. They find that odd. They ask a man what's going on. He remembers that they've been gone so they don't know. Sam died. "Keeled over one of the snooker tables. Had a stroke," the man says. He adds the Sam left the diner to Genevieve, the theater to Miss Mosey and the pool hall to Sonny.

Back to that ride home from Oklahoma between Lois and Sonny. Before they get in the car, Lois tells him that he should have stayed with Ruth Popper. "Does everyone know about that?" he asks annoyed. She says yes. "I guess I treated her badly," Sonny admits. "Guess you did," Lois concurs. As she drives, Sonny says, "Nothin's really been right since Sam the Lion died." No, they really haven't, Lois agrees. Sonny guesses that she must have liked him a lot, but Lois says no, she loved him. Sonny mentions the story Sam told him about the girl and she's surprised. "He told you that? You know, I'm the one who started calling him Sam the Lion," Lois confesses as Sonny realizes that she was the girl that Sam talked about. She apologizes for getting slightly teary. "It's terrible to meet only one man in your life who knows what you're worth," Lois admits. "I guess if it wasn't for Sam, I'd have missed it, whatever it is. I'd have been one of them amity types that thinks that playin' bridge is about the best thing that life has to offer."

When Sonny gets back to town, he learns Duane, who has enlisted in the Army, is in town for a short visit. He asks if he wants to go with him to the Royal. Miss Mosey has to close the picture show. Duane agrees. The final movie is Howard Hawks' Red River. "No one wants to come to shows no more. Kid baseball in the summer, television all the time," Miss Mosey tells them. Imagine now. Out-of-sight prices, out-of-control crowds, declining quality of product, more at-home convenience, everything digital so there is in essence no difference between theaters and home. The next day, Duane boards a bus to his base to ship off for Korea. "I'll see you in a year or two if I don't get shot," he tells Sonny.

As Sonny works the pool hall, the scene mirrors the opening with the howling wind and blowing dust, only this time he hears a commotion. He runs outside and sees that a truck hauling cattle struck and killed Billy who, as usual was sweeping the middle of the street. A bunch of gawkers try to console the driver, explaining that the kid was "simple" and continuously asking why he had that broom. Sonny snaps. "He was sweeping you sons of bitches, he was sweeping!" he yells as he picks Billy's broken body up and lays it on the sidewalk.

Eventually, he works up the nerve to knock on Ruth's door and asks if he can have a cup of coffee with her. She apologizes for still being in her bathrobe this late in the day. Then, as she's starting to pour coffee, it's her turn to explode and she throws the cup and the coffee pot against the wall.

"What am I doing apologizing to you? Why am I always apologizing to you, you little bastard? Three months I've spent apologizing to you without you even being here. I haven't done anything wrong. Why can't I quit apologizing? You're the one ought to be sorry. I wouldn't still be in my bathrobe. I would've had my clothes on hours ago. It's because of you I quit caring if I got dressed or not. I guess because your friend got killed you want me to forget what you did and make it alright. I'm not sorry for you. You'd have left Billy too just like you left me. I bet you left him plenty of nights, whenever Jacy whistled. I wouldn't treat a dog that way. I guess I was so old and ugly it didn't matter how you treated me — you didn't love me."

Ruth sits down at the kitchen table across from Sonny. "You shouldn't have come here. I'm around that corner now. You've ruined it and it's lost completely. Just your needing me won't make it come back," Ruth tells him. He reaches out and takes her hand. She takes it and puts it to her face. He never says a word. The two of them just sit holding hands across the table.

Lots of people can quote the last lines of movies, but when you think about it, there aren't as many famous final ones as you would think. The Last Picture Show belongs in that exclusive company.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, B. Johnson, Bogdanovich, Burstyn, Cybill Shepherd, George C. Scott, Hackman, Hawks, Jeff Bridges, John Ford, Karloff, Liz, Lucas, Matthau, Movie Tributes, Oscars, R. Quaid, Sequels, Tracy, Wayne

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, October 09, 2011

A Lady and a Gentleman

By Eddie Selover