Thursday, October 10, 2013

Better Off Ted: Bye Bye 'Bad' Part III

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now. If you missed Part I, click here. If you missed Part II, click here.

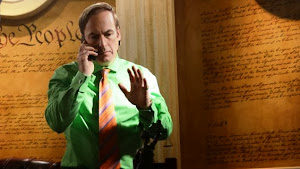

— Saul Goodman to Mike Ehrmantraut ("Buyout," written by Gennifer Hutchison, directed by Colin Bucksey)

By Edward Copeland

Playing to the back of the room: I love doing it as a writer and appreciate it even more as an audience member. While I understand how its origin in comedy clubs gives it a derogatory meaning, I say phooey in general. Another example of playing to the broadest, widest audience possible. Why not reward those knowledgeable ones who pay close attention? Why cater to the Michele Bachmanns of the world who believe that ignorance is bliss? What they don’t catch can’t hurt them. I know I’ve fought with many an editor about references that they didn’t get or feared would fly over most readers’ heads (and I’ve known other writers who suffered the same problems, including one told by an editor decades younger that she needed to explain further whom she meant when she mentioned Tracy and Hepburn in a review. Being a free-lancer with a real full-time job, she quit on the spot). Breaking Bad certainly didn’t invent the concept, but damn the show did it well — sneaking some past me the first time or two, those clever bastards, not only within dialogue, but visually as well. In that spirit, I don’t plan to explain all the little gems I'll discuss. Consider them chocolate treats for those in the know. Sam, release the falcon!

In a separate discussion on Facebook, I agreed with a friend at taking offense when referring to Breaking Bad as a crime show. In fact, I responded:

“I think Breaking Bad is the greatest dramatic series TV has yet produced, but I agree. Calling it a ‘crime show’ is an example of trying to pin every show or movie into a particular genre hole when, especially in the case of Breaking Bad, it has so many more layers than merely crime. In fact, I don't like the fact that I just referred to it as a drama series because, as disturbing, tragic and horrifying as Breaking Bad could be, it also could be hysterically funny. That humor also came in shapes and sizes across the spectrum of humor. Vince Gilligan's creation amazes me in a new way every time I think about it. I wonder how long I'll still find myself discovering new nuances or aspects to it. I imagine it's going to be like Airplane! — where I still found myself discovering gags I hadn't caught years and countless viewings after my initial one as an 11-year-old in 1980. Truth be told, I can't guarantee I have caught all that ZAZ placed in Airplane! yet even now. Can it be a mere coincidence that both Breaking Bad and Airplane! featured Jonathan Banks? Surely I can't be serious, but if I am, tread lightly.”

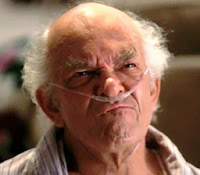

— Jonathan Banks as air traffic controller Gunderson in Airplane!

The second season episode “ABQ” (written by Vince Gilligan, directed by Adam Bernstein) introduced us to Banks as Mike and also featured John de Lancie as air traffic controller Donald Margulies, father of the doomed Jane. Listen to the DVD commentary about a previous time that Banks and De Lancie worked together. Speaking of air traffic controllers, if you don’t already know, look up how a real man named Walter White figured in an airline disaster. Remember Wayfarer 515! Saul never did, wearing that ribbon nearly constantly. Most realize the surreal pre-credit scenes that season foretold that ending cataclysm and where six of its second season episode titles, when placed together in the correct order, spell out the news of the disaster. Breaking Bad’s knack for its equivalent of DVD Easter eggs extended to episode titles, which most viewers never knew unless they looked them up. Speaking of Saul Goodman, he provided the voice for a multitude of Breaking Bad’s pop culture references from the moment the show introduced his character in season two’s “Better Call Saul” (written by Peter Gould, directed by Terry McDonough). Once he figures out (and it doesn’t take long) that Walt isn’t really Jesse’s uncle and pays him a visit in his high school classroom, the attorney and his client discuss a more specific role

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.

players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.As I admitted, some of the nice touches escaped my notice until pointed out to me later. Two of the most obvious examples occurred in the final eight episodes. One wasn’t so much a reference as a callback to the very first episode that you’d need a sharp eye to spot. It occurs in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson) and I’d probably never noticed if not for a synched-up commentary track that Johnson did for the episode on The Ones Who Knock weekly podcast on Breaking Bad. He pointed out that as Walt rolls his barrel of $11 million through the desert (itself drawing echoes to Erich von Stroheim’s silent classic Greed and its lead character McTeague — that one I had caught) he passes the pair of pants he lost in the very first episode when they flew through the air as he frantically drove the RV with the presumed dead Krazy-8 and Emilio unconscious in the back. Check the still below, enlarged enough so you don’t miss the long lost trousers.

The other came when psycho Todd decided to give his meth cook prisoner Jesse ice cream as a reward. I wasn’t listening closely enough when he named one of the flavor choices as Ben & Jerry’s Americone Dream, and even if I’d heard the flavor’s name, I would have missed the joke until Stephen Colbert, whose name serves as a possessive prefix for the treat’s flavor, did an entire routine on The Colbert Report about the use of the ice cream named for him giving Jesse the strength to make an escape attempt. One hidden treasure I did not know concerned the appearance of the great Robert Forster as the fabled vacuum salesman who helped give people new identities for a price. Until I read it in a column on the episode “Granite State” (written and directed by Gould), I had no idea that in real life Forster once actually worked as a vacuum salesman.

Seeing so many episodes multiple times, the callbacks to previous moments in the series always impressed me. I didn’t recall until AMC held its marathon prior to the finale and I caught the scene where Skyler caught Ted about him cooking his company’s books in season two’s “Mandala” (written by Mastras, directed by Adam Bernstein),

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.I wanted this tribute to be so much grander and better organized, but my physical condition thwarted my ambitions. I doubt seriously my hands shall allow me to complete a fourth installment. (If you did miss Part I or Part II, follow those links.) While I hate ending on a patter list akin to a certain Billy Joel song, (I let you off easy. I almost referenced Jonathan Larson — and I considered narrowing the circle tighter by namedropping Gerome Ragni

& James Rado.) I feel I must to sing my hosannas to the actors, writers, directors and other artists who collaborated to realize the greatest hour-long series in

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

In fact, the series failed me only twice. No. 1: How can you dump the idea that Gus Fring had a particularly mysterious identity in the episode “Hermanos” and never get back to it? No. 2: That great-looking barrel-shaped box set of the entire series only will be made on Blu-ray. As someone of limited means, it would need to be a Christmas gift anyway and for the same reason, I never made the move to Blu-ray and remain with DVD. Medical bills will do that to you and, even if tempting or plausible, it’s difficult to start a meth business to fund it while bedridden. Despite those two disappointments, it doesn’t change Breaking Bad’s place in my heart as the best TV achievement so far. How do I know this? Because I say so.

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Cranston, D. Zucker, De Palma, Deadwood, Hackman, Hawks, HBO, J. Zucker, Jim Abrahams, K. Hepburn, O'Toole, Oliver Stone, Tracy, Treme, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, April 16, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Catherine Scorsese

around the world, there would be no need for social workers."

— Nicholas Pileggi on Catherine Scorsese at a family-style dinner serving her recipes

held in her honor following her death at 84 in 1997.

By Edward Copeland

Pileggi, the author of the nonfiction books Wiseguy and Casino, and co-writer of their film versions, Goodfellas and Casino, with Martin Scorsese was speaking of the director's late mother, who engendered that feeling in many in Martin Scorsese's extended film family. At the same time, her frequent appearances in her son's films (and other directors' movies as well) made Catherine Scorsese one of the most

recognizable filmmaker's mothers who didn't work in show business to make a living. When Mrs. Scorsese did hold a job, she worked as a seamstress in New York's Garment District where she met Marty's father, Charles Scorsese, who toiled there as a clothes presser and also frequently appeared in their son's films as well until his death in 1993. Catherine Cappa, born 100 years ago today in New York to parents who emigrated from Sicily, also was a helluva cook, a gift passed down through generations of her family and Charles'. In fact, Catherine's culinary talents inspired the memorial dinner party that Suzanne Hamlin wrote about in The New York Times in February 1997. Catherine had gathered some of the best of the Scorsese and Cappa family recipes and published them in Italianamerican: The Scorsese Family Cookbook, which reached store shelves in December 1996. Unfortunately, her bout with Alzheimer's had advanced too far to allow her to promote the cookbook and she passed away the following month. I love Italian food and imagine consuming one of her dinners would have been one of the highlights of my life. However, her family recipes' reputation ring up resounding endorsements, but I imagine that her greatest creation of all goes by the name of Martin Charles Scorsese and her role in delivering that gift to the world prompted me to write this tribute to her today.

recognizable filmmaker's mothers who didn't work in show business to make a living. When Mrs. Scorsese did hold a job, she worked as a seamstress in New York's Garment District where she met Marty's father, Charles Scorsese, who toiled there as a clothes presser and also frequently appeared in their son's films as well until his death in 1993. Catherine Cappa, born 100 years ago today in New York to parents who emigrated from Sicily, also was a helluva cook, a gift passed down through generations of her family and Charles'. In fact, Catherine's culinary talents inspired the memorial dinner party that Suzanne Hamlin wrote about in The New York Times in February 1997. Catherine had gathered some of the best of the Scorsese and Cappa family recipes and published them in Italianamerican: The Scorsese Family Cookbook, which reached store shelves in December 1996. Unfortunately, her bout with Alzheimer's had advanced too far to allow her to promote the cookbook and she passed away the following month. I love Italian food and imagine consuming one of her dinners would have been one of the highlights of my life. However, her family recipes' reputation ring up resounding endorsements, but I imagine that her greatest creation of all goes by the name of Martin Charles Scorsese and her role in delivering that gift to the world prompted me to write this tribute to her today. In the 1990 American Masters episode "Martin Scorsese Directs," Charles and Catherine discussed what their son's early life was like growing up in New York's Little Italy. The sound in this clip is missing at the beginning, but then it kicks in.

Martin Scorsese started putting his mother into small roles in his films from the beginning (Charles didn't show up on camera until Scorsese's 1974 short documentary on them, Italianamerican) for financial reasons: He couldn't afford to pay actors. Catherine's personality not only proved made for the camera but she also displayed a charming gift for improvising dialogue. She appeared in her son's very first short, a 1964 comedy called It's Not You, Murray, which co-starred Mardik Martin who co-wrote the short with Scorsese and would go to co-write the screenplays for Mean Streets, New York, New York and Raging Bull. The comedy short about an accidental crook also featured future SCTV star Andrea Martin (no relation to Mardik). Catherine turned up again in Who's That Knocking at My Door? and Mean Streets, both of which starred Harvey Keitel who attended that memorial dinner and said of Mrs. Scorsese, "In my memory, Catherine was the epitome of a warm, loving Italian mother. She enjoyed watching me eat as much as I enjoyed eating her cooking." Then, as his feature filmmaking career had started to really take off, Martin took some time to make that 45-minute short documentary Italianamerican where the real Catherine Scorsese shines in all her glory. This segment details his parents' recent visit to Italy.

The end credits for Italianamerican actually ran the family recipe for spaghetti sauce and meatballs. The next time that Catherine contributed to one of her son's films, she only put in a vocal appearance as Rupert Pupkin's hector mother constantly yelling at him from upstairs in the great The King of Comedy with longtime fan of her homemade pizza, Robert De Niro.

Catherine Scorsese's next two film roles actually occurred in films that weren't directed by her son. First, in 1986 she played a birthday party guest in Brian De Palma's alleged comedy starring Danny DeVito and Joe Piscopo. The next year, she waited to be served as a customer at the bakery in Norman Jewison's Moonstruck. Later, she would play a woman in a cafe in Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather Part III. She also appeared in a 1994 movie called Men Lie that played a lot of film festivals, but I'm not sure if it ever received a theatrical release. Watch this promo and try to count how many actors in it eventually showed up on The Sopranos.

Catherine's next appearance in one of her son's film remains her longest and most memorable role as the lovable mother of Joe Pesci's psychotic mobster Tommy DeVito in Goodfellas. Pesci also attended the memorial dinner party for Katherine and told The Times, "Katie was one of the sweetest ladies I ever met. She was a true innocent. She never did anything bad; she never knew anything bad. In terms of her cooking, it's a toss-up as to who's a better cook, Katie or my mother." The hysterical scene where Tommy, Jimmy Conway (De Niro) and Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) drop by her house in the middle of the night looking for tools to dispose of a body in the trunk of Henry's car and she wakes up and insists on feeding them remains a classic scene in a film that's wall-to-wall classics. Of course, embedding Goodfellas clips from YouTube strictly won't be allowed, so you'll just have to click on that word "scene" to watch it again. However, we do have a clip from an AFI special where Jim Jarmusch interviews Martin Scorsese about his mother's role in the scene.

The next movie her son made, the role wasn't as plum as Tommy's mother — she merely shopped at a fruit stand in his Cape Fear remake. To promote the film, Marty appeared as a guest on Late Night with David Letterman in November 1991, and even took Catherine along to make some of that homemade pizza that De Niro loves so much for Marty, Dave and another guest we all know and love.

I so dearly wish I could have found a screenshot or YouTube clip of her appearance in 1993's The Age of Innocence because it's such a touching gift to his parents. Charles Scorsese died on Aug. 22, 1993 and The Age of Innocence would end up being his last appearance in one of his son's movies. The movie itself didn't get released until Oct. 1, but the image Scorsese filmed of his parents, showing them moving slowly toward the camera in a snowy, white haze couldn't have been a lovelier image. His mother managed to appear in a character role in a scene in Casino, his next movie, and that would be her last appearance.

What a gift Catherine Cappa Scorsese and Charles Scorsese gave the world. It's the American story. They were first-generation Italian Americans, struggling to raise two sons in New York while eking out livings in the Garment District. Keeping careful watch on the one boy, an asthmatic child who couldn't go play sports as the other children could but discovered a grand universe in the movies his father took him to at a young age. Charles Scorsese's centennial doesn't occur until next year, but honestly this tribute belongs to both of them (Catherine couldn't have created Marty by herself or we would have an entirely different story on our hands). If you haven't seen it, try to watch Italianamerican. I'm not the biggest believer in otherworldly things, but I'm grateful for fate, higher powers or whatever joined Charles and Catherine together to give us the unbelievably wonderful gift of their son.

Tweet

Labels: Books, Coppola, De Niro, De Palma, DeVito, Documentary, Jewison, Keitel, Letterman, Liotta, Murray, Pesci, Scorsese, The Sopranos

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, March 31, 2012

The World is Yours

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

Around my home base at Thrilling Days of Yesteryear, the “Gangster Trilogy” is the nickname assigned to the three movies that for many kicked off the crime film genre in the 1930s: Little Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and Scarface (1932). The first of these films starred Edward G. Robinson in what has commonly been called his “breakout” role, and Enemy did likewise for James Cagney…making both actors silver screen legends. Though there are variances in the plots of each movie, they feature a unifying theme of a racketeer who rises to the top of his profession stealing, killing and plundering all the way…only to achieve his comeuppance before the lights in the theater come up and the second show begins.

Scarface — which at the time of its release 80 years ago on this date was subtitled “The Shame of a Nation” — also made veteran stage actor Paul Muni a household name among theatergoers, though his starring turn in I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang equally boosted his cinematic stature (he received an Oscar nomination for the role, and was soon signed to a long-term contract by Warner Bros.) as well. While both Caesar and Enemy were Warner releases, Scarface was an independent production funded by the deep-pocketed Howard Hughes (and released by United Artists) and as such it’s often the overlooked feature of the three. (At one time, the movie even was withdrawn from release and didn’t resurface until 1979.) If it’s remembered at all today, it’s probably because it was the inspiration for the 1983 Brian De Palma cult classic with Al Pacino as the lead. But there’s much more than meets the eye in the Howard Hawks-directed original. (Much more.)

Crime boss “Big” Louis Costillo (Harry J. Vegar) is gunned down by a mysterious assailant shortly after he’s thrown one of his impressive shindigs, and as dedicated police inspector Ben Guarino (C. Henry Gordon) has been instructed to round up the usual suspects, he brings in Antonio “Tony” Camonte (Muni) and Guino “Little Boy” Renaldo (George Raft), two lieutenants who work for one of Costillo’s rivals, Johnny Lovo (Osgood Perkins). Lovo gets both men released with writs of habeas corpus, and we learn that Tony was responsible for croaking Big Louie at the behest of Lovo. Johnny then informs his now second-in-command that they’ll be taking over the beer concession on the city’s South Side, selling illegal suds to speakeasies and squeezing out those bars owned by rival gangs. Lovo has specifically ordered the ambitious Camonte to leave the North Side operation (run by a hood named O’Brien) alone, because that’s just asking for trouble.

Tony’s stock starts to rise in the beer rackets, and he finds himself constantly trying to attract the attention of Poppy (Karen Morley), Lovo’s girlfriend. He’s also earned the disapproval of his mother (Inez Palange), who scolds Tony’s sister Francesca (Ann Dvorak) when she accepts her brother's “dirty” money. Tony has a rather unhealthy (and suggestively incestuous) relationship with “Cesca” to the point that he gets enraged when he sees her in the company of eligible men. Finally, the impatient Tony makes a bid for the North Side operation by having Little Boy “eliminate” O’Hara in his flower shop, and this stunt earns him both the disapproval of Lovo and the enmity of Gaffney (Boris Karloff), the hood who takes over for the deceased O’Hara. Tony and his men wage a full assault on Gaffney and the other gangs…and seeing that Camonte is consolidating his power, Lovo orders a hit on Tony. The attempt fails, and Tony (with the help of Little Boy) exacts swift retribution.

The forces of good beat their collective breasts at the lawlessness exhibited by Tony, who is now king of all he surveys, and despite increased pressure by the newspapers and law enforcement, there seems to be little that will stop him. His downfall comes when he shoots and kills Little Boy after finding him in the same apartment with Cesca, not knowing that they have secretly wed. Returning to his stronghold (his sidekick Angelo, played by Vince Barnett, also has been killed as a result) as the police close in, Cesca arrives to Tony's surprise; she had planned to kill him for revenge but now realizes that “you’re me and I’m you” and she agrees to hold them off, but she’s felled by a stray bullet, and tear gas drives the now abandoned Tony out of his hideout to face Guarino and two detectives downstairs. Camonte agrees to come quietly, but bolts from his captors at the last minute and ends up gunned down in the street.

W.R. Burnett, the author responsible for the novel on which Little Caesar was adapted, was one of several credited scribes who supplied dialogue and continuity for Scarface, along with Seton I. Miller and John Lee Mahin (with uncredited contributions from producer Hawks and Fred Pasley) — but the bulk of the screenplay was penned by old newspaper hand Ben Hecht, who adapted Armitage Trail’s 1929 novel of the same name. “Scarface” also was the well-known nickname of racketeer Al Capone, and concerned that the film might possibly portray him in a negative light, he supposedly sent a couple of his boys around to see Hecht, hoping to discourage him from finishing the project. But Hecht, being a veteran ink-stained wretch, was not an easy man to scare…and according to legend, not only did he convince Capone’s goombahs that the movie was not about their boss, but he called upon them as consultants. (Further legend states that the end result pleased Al so much that he later obtained a print of the film for his very own.)

At the time of Scarface’s release, a vocal faction of individuals, concerned that others might be having more fun than they were, decried the product coming out of Hollywood…and the Hawks-Hughes movie was one on which they complained the longest and loudest. The accusations claimed the film glamorized gangsters and crime, and that this might be a bad influence on impressionable minds. Most of the time, this was true — it’s what was known as the “sin-and-salvation” approach to filmmaking. Cecil B. DeMille mastered this; presenting sequences of immorality and debauchery in his silent epics (which he got away with provided the characters received their just deserts at the end). Many of the later “message” movies that tried to warn innocent dupes away from sex or drugs (such as Reefer Madness) also took the same approach…and you often have to wonder how effective that was, showing kids having the time of their lives drinking and partying while frowning upont this type of behavior to be frowned.

I don’t think anyone would ever emulate the onscreen conduct in Scarface, however. The main character, Tony Camonte, isn’t a particularly admirable role model — as played by Muni, he’s positively primal; at times it’s as if someone shaved a simian and forced him into a nice suit. (Critic Danny Peary once observed that Muni’s Tony is essentially Fredric March’s Mr. Hyde, only without the fangs.) Camonte is constantly in a state of macho swagger, thinking himself sophisticated (but he’s not) and like a 1930s Donald Trump, judges the quality of what he buys by how much it costs. “That’s pretty hot” proves to be the highest praise he can bestow upon any item or individual, proving that Paris Hilton didn’t just come up with that asinine catchphrase by her lonesome. And like James Cagney’s Cody Jarrett in White Heat, Tony Camonte has some serious psychological problems. Man, has he got it bad for his sister Cesca. Of the film's many elements, the incest theme intrigues the most in what I consider to be the best gangster movie of the 1930s, addressed in the uncomfortable familial relationship between brother and sister Camonte. Hecht based the characters on the Borgia family, making actress Ann Dvorak a delightfully slutty carbon copy of Lucretia and while Muni received many of the critical kudos for his performance in the film, I think Dvorak walks away with the picture. Scarface made me a huge fan of the underrated actress; her tantalizing dance moves and naughty double entendres (not to mention that unmistakable glint she gets in her eye when she talks to Muni’s Tony) no doubt concerned the censors more than the violence.

I also became a Karen Morley fan because of this film, even though I’ll certainly concede that Dvorak gets the showier role and makes much more of an impression. (Morley was an underrated thesp, often on the receiving end of static from the industry about her personal life and politics, all coming to a boil in 1947 with her blacklisting in the motion picture industry after testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee.) As Poppy, the fair-weather bitch who switches her romantic allegiance to Tony when she’s able to read the tea leaves that Johnny Lovo hasn’t much of a future, I like her blasé responses to Camonte’s advances (“I’m nice with a lot of dressing”), and how at times it seems as if she’s having difficulty holding it in and not laughing at the jerk. Scarface also served as a breakout vehicle for actor George Raft, who had danced his way to fame on Broadway (under the tutelage of Texas Guinan) before venturing out to Hollywood to crash the movie business. Raft had appeared in films before Scarface but his “Little Boy” character in the picture really cemented his stature in the motion picture industry; during the 1930s he was the go-to individual for gangster portrayals alongside Cagney and Robinson. George was quite cozy with a number of real-life hoods (including Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky), which led many people to speculate that he actually might have been in the mob at one time (he wasn’t). A bit of business performed by Raft — flipping a nickel in the air and catching it while never looking at the coin — soon became a trademark and even provided a hilarious in-joke in 1959’s Some Like It Hot, in which he had a nice comic (and menacing) turn as hood Spats Columbo.

The actor who wasn’t quite as convincing as Raft playing a gangster was Boris Karloff, who also had a small role in Scarface as Gaffney. Personally, I welcome Boris in any movie but the man was just a little too cultured and refined to play a hood. Be that as it may, Boris does get a memorable death scene in which he’s gunned down by Muni and his mob while bowling…and though he leaves this world having bowled a strike, the “kingpin” symbolically takes a little time to fall before finally doing so. Symbolism plays a large part in Scarface; director Hawks came up with an interesting motif in that all of the gangsters who are “rubbed out” are designated as such with an “X” visible onscreen. Hawks thought this great fun, even to the point of offering crew members $200 for each creative suggestion to allow him to present this. Scarface originally had been scheduled to be released in September 1931, but producer Hughes still was getting grief from the Hays’ Office about the movie’s violent content. In an attempt to pacify the censors, the producer had Richard Rosson shoot an alternate ending, one in which Muni doesn’t die in a hail of bullets at the end but gets taken into custody, tried and convicted by a judge (who gives Muni’s character a lecture though you never see the actor) and sentenced to hang by the neck until he’s really most sincerely dead. (This scene also was shot without Muni’s participation; a double was used in long shots.) The censors weren’t wild about this ending either so Hughes finally threw up his hands and just did an end run around them, releasing the movie in states where there were no censorship boards. (It did great box office and received positive critical reviews.) The “alternate ending” has survived and is available on Universal’s 2007 DVD release…but seeing as how they also eliminated some of the more overt sexual attraction between the Muni and Dvorak characters, I’m glad Hughes stuck to his guns and kept Ending A.

That stand-alone disc release of Scarface provided the best news a classic film fan could get in that before that DVD, the only way you could purchase a copy of the Hawks original was on a 2003 “Anniversary Edition” box set of the 1983 Brian De Palma version…and that’s a purchase I simply wasn’t capable of justifying. There’s even more bad news on the horizon in that Universal has got another remake of the film in the works (this was announced last year) that will combine elements of the 1932 and 1983 films…but as a cinematic British barrister once observed: “Is that really desirable?” Classic film fans can take solace in that the one-and-only original is being looked after; having been added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 1994. Otherwise I’d have no other recourse than to respond with one of Tony Camonte’s most memorable quips: “Get out of my way, Johnny…I’m gonna spit!”

Tweet

Labels: 30s, blacklist, Cagney, De Palma, Edward G., Fredric March, Hawks, Hecht, Howard Hughes, Karloff, Movie Tributes, Pacino, Raft

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, March 06, 2012

How terrible is wisdom when it brings no profit to the wise

By Edward Copeland

When contemplating possible headlines for my 25th anniversary tribute to Alan Parker's thriller Angel Heart, I almost considered using the words SPOILER ALERT. The 1987 movie is one of the first films released in my moviegoing lifetime in which an essential part of its appeal comes from the plot twist revealed near the end, though I had guessed it earlier in the film and the gimmick doesn't distract from the solid atmospherics, the great lead performance by Mickey Rourke and several supporting performances including one credited as "Special Appearance by Robert De Niro." If by chance you have not seen Angel Heart, move along now because it's difficult to discuss without giving away its secrets, even 25 years later. Some other titles containing twists might come up as well. It reminds me of a very early post on this blog about twists in films. You have been warned. It also makes me recall my dream that when any friends become new parents I beg them to keep all knowledge about Psycho away from the child until they see it since by the time I saw it, I knew what was coming. Then again, in the original 1960 trailer, Alfred Hitchcock points out the shower and the top of the steps, shows Janet Leigh screaming and suggests something's wrong with Anthony Perkins' character, so Hitch didn't try to hide it much himself.

Though Alan Parker's filmography always glowed eclectically, 1987's Angel Heart marked yet another turn in the British director's career as he helmed his first unabashed mystery thriller — and one with supernatural and voodoo undercurrents at that. In an introduction recorded for the 2004 special edition DVD, Parker discussed watching Angel Heart for the first time in many years. "It's strange seeing it at a distance because you kinda see it for the first time," Parker said. "Actually, seeing it again, I'm very proud of it. I think it holds up."

I found myself much in the same position as Parker when I revisited Angel Heart for this anniversary tribute, though the film left such an impression on me when I originally saw it in 1987 and a few more times in years soon after that it surprised me how well its specifics had stayed with me, thanks to the craftsmanship, the

screenplay (which Parker also wrote, adapting it from the novel Falling Angel by William Hjortsberg) and the acting. Parker admits changing the novel quite a bit. While the novel took its setting exclusively certain parts of New York, primarily Brooklyn, Parker expanded it to Harlem and added the New Orleans element entirely. Parker also created characters, dialogue and shifted the time period backward from 1959 to 1955 because he wished to keep it further away from the 1960s and closer to the 1940s as a period piece. What, perhaps, startled me the most — seeing how young Mickey Rourke looked back when he was at the peak of his powers, though from a 2004 interview with Rourke on the DVD, you wouldn't get that. Rourke says he was close to losing his house when Angel Heart came his way and had been weighing quitting acting. The chance to work with Alan Parker attracted Rourke to Angel Heart more than the film itself. Thankfully, Rourke made his comeback after his flirtation with boxing, first in Sin City and then in The Wrestler (don't know if I should count Iron Man 2 or not), but I wonder how many great roles we lost while he was lost.

screenplay (which Parker also wrote, adapting it from the novel Falling Angel by William Hjortsberg) and the acting. Parker admits changing the novel quite a bit. While the novel took its setting exclusively certain parts of New York, primarily Brooklyn, Parker expanded it to Harlem and added the New Orleans element entirely. Parker also created characters, dialogue and shifted the time period backward from 1959 to 1955 because he wished to keep it further away from the 1960s and closer to the 1940s as a period piece. What, perhaps, startled me the most — seeing how young Mickey Rourke looked back when he was at the peak of his powers, though from a 2004 interview with Rourke on the DVD, you wouldn't get that. Rourke says he was close to losing his house when Angel Heart came his way and had been weighing quitting acting. The chance to work with Alan Parker attracted Rourke to Angel Heart more than the film itself. Thankfully, Rourke made his comeback after his flirtation with boxing, first in Sin City and then in The Wrestler (don't know if I should count Iron Man 2 or not), but I wonder how many great roles we lost while he was lost.

Of course, Angel Heart also includes that great supporting performance by Robert De Niro that reminds you of the days when he seemed to take parts for more than just a paycheck. In an interview on the DVD, Parker says he originally sought De Niro to play Harry Angel (Rourke's role), but De Niro expressed more interest in the Louis Cyphre role. Parker had been chasing Jack Nicholson for Cyphre, but Jack got to be devilish in a different 1987 film, as Darryl Van Horne in the in-title only adaptation of John Updike's The Witches of Eastwick. The process of nabbing De Niro, according to Parker, was an arduous game of back-and-forth until one day De Niro finally phoned and told Parker, "I'm of a mind to do the film." I gave you the spoiler warning up top, so, as the song goes, I hope you guessed De Niro's character's name and since he's a punny devil — Louis Cyphre…Lou-Cyphre…Lucifer. As Cyphre explains, "Mephistopheles is such a mouthful in Manhattan." Also like the lyrics of The Rolling Stones' classic, De Niro portrays Cyphre as a man of wealth and taste, well-dressed with frighteningly long fingernails, always playing with his cane. Many sources claim that De Niro's performance actually is a wicked impersonation of Martin Scorsese. Physically, he might resemble how Scorsese looks at times but that certainly isn't Marty's vocal style. De Niro's Angel Heart character speaks too deliberately without a shred of accent and never sounds as if he's on fast-forward as Scorsese does. I've said this many times about great actors and probably about De Niro, but his excellence extends to masterful manipulation of props. In Angel Heart, De Niro displays it with the cane and, later, with an egg. Like Rourke, 1987 gave moviegoers two memorable De Niro turns. He also preached "teamwork" as Al Capone in Brian De Palma's The Untouchables.

Angel Heart opens by getting the audience in a properly creepy mood opening on a dark street where a dog barks wildly on the pavement while way above the canine a cat hisses on a fire escape. At the bottom of the fire escape, where the pooch continues to make noise lays the violently slain body of a woman. Honestly, the movie never gets back around to telling us who she was or how she relates to rest of the story but the tableau combines with Trevor Jones' slightly sinister score and the proper look provided by d.p. Michael Seresin, who served as cinematographer on many Parker films including Midnight Express, Fame and Birdy. Seresin's work goes far in creating Angel Heart's atmosphere and accomplishing Parker's stated goal of making "a black-and-white film in color." After that opening, we appear to be on the same street, knowing now that it's Brooklyn 1955 as Mickey Rourke pops a bubble and then lights a cigarette as a faceless voice greets him as "Harry." Soon, he's sitting behind his desk in his disheveled office when he gets a phone call. "Harold Angel. Middle initial R. Just like in the phone book," he answers. "Of course I know what an attorney is. It's like a lawyer only their bills are higher," he tells the person on the phone. He scrounges for pen and paper, passing a gun in his desk drawer, and scrawls Winesap and McIntosh. Harry then adds Louis Cyphre and sets up a meeting, a bit out of his usual stomping grounds in Harlem, but Angel pledges to be there.

The best running gag in Angel Heart, since the film never tries too hard to conceal Louis Cyphre's true identity, has half of his meetings with Harry Angel taking place in churches — and Cyphre gets on the private detective when he uses unsavory language.

Their first meeting takes place at a Harlem church. Harry climbs to the church's second level where he meets Herman Winesap (Dann Florek, who we now know best as Captain Kragen on the original Law & Order and Law & Order: SVU but always will be L.A. Law 's Dave Meyer to me). As Winesap prepares to take Harry to meet Cyphre, Angel notices a shrouded woman furiously scrubbing blood off the wall of a room. "An unfortunate husband of one of Pastor John's flock took a gun to his head," Winesap explains. "Most unpleasant." When Winesap opens the door to another room, we see

Their first meeting takes place at a Harlem church. Harry climbs to the church's second level where he meets Herman Winesap (Dann Florek, who we now know best as Captain Kragen on the original Law & Order and Law & Order: SVU but always will be L.A. Law 's Dave Meyer to me). As Winesap prepares to take Harry to meet Cyphre, Angel notices a shrouded woman furiously scrubbing blood off the wall of a room. "An unfortunate husband of one of Pastor John's flock took a gun to his head," Winesap explains. "Most unpleasant." When Winesap opens the door to another room, we see that hand and those long fingernails playing with the handle of his cane before we see Louis Cyphre himself. Though De Niro makes no attempt at any sort of accent, he's introduced as "Monsieur Louis Cyphre." Without getting up, he shakes Harry's hand. In fact, Cyphre never stands in the entire film. He asks to see Angel's identification. "Nothing personal. I'm a little overcautious," Cyphre admits. De Niro's performance displays such control that it really makes me nostalgic for that De Niro. Harry asks how they came up with his name, assuming it was the phone book since most of his clients pick him since his last name starts with an A and they are lazy. As Harry spins his theory, Cyphre silently and definitely shakes his head no. That's a gesture most humans could make, but the De Niro of that time conveys so much with that small motion. He and Winesap then explain the case they want Angel to take. "Do you by chance remember the name Johnny Favorite?" Cyphre inquires.

that hand and those long fingernails playing with the handle of his cane before we see Louis Cyphre himself. Though De Niro makes no attempt at any sort of accent, he's introduced as "Monsieur Louis Cyphre." Without getting up, he shakes Harry's hand. In fact, Cyphre never stands in the entire film. He asks to see Angel's identification. "Nothing personal. I'm a little overcautious," Cyphre admits. De Niro's performance displays such control that it really makes me nostalgic for that De Niro. Harry asks how they came up with his name, assuming it was the phone book since most of his clients pick him since his last name starts with an A and they are lazy. As Harry spins his theory, Cyphre silently and definitely shakes his head no. That's a gesture most humans could make, but the De Niro of that time conveys so much with that small motion. He and Winesap then explain the case they want Angel to take. "Do you by chance remember the name Johnny Favorite?" Cyphre inquires.

The name Johnny Favorite doesn't ring a bell with Harry Angel, but Cyphre explains that Favorite was a crooner prior to the war. "Quite famous in his way," Louis adds. "I usually don't get involved in anything very heavy. I usually handle insurance jobs, divorces, things of that nature. If I'm lucky sometimes I handle people, but I don't know no crooners or anybody famous," Harry tells the mysterious Cyphre and his attorney. They inform the detective that Favorite’s real last name was Liebling, but Harry doesn’t know that name either. He asks the pair if this Johnny owes them money and that’s why they’re looking for him. “Not quite. I helped Johnny at the beginning of his career,” Cyphre says, leading Angel to ask if he was the singer’s agent. “No! Nothing so…,” the bearded man semi-smiles, not bothering to complete his thought. “Monsieur Cyphre has a contract. Certain collateral was to be forfeited in the event of his death,” Winesap steps in to explain. That takes Harry back a bit. “You're talking about a guy that's dead?” he asks. Cyphre and Winesap go on to tell Angel the story of how they lost track of Johnny Favorite. In 1943, the entertainer was drafted to aid the U.S. war effort in North Africa as part of the special entertainment services. Soon after his arrival, an attack severely disfigured Favorite, both physically and mentally. “Amnesia. I think you call it,” Cyphre tells Harry, who tosses out, “Shell shock.” Cyphre concurs with Angel’s description and his interest gets piqued when the private eye admits to knowing how that condition feels. He asks Harry if he was in the military. ‘I was in for a short time, but I got a little fucked up, excuse my language. They shipped me home, and I missed the whole shebang — the war, the medals, everything. I guess you could say I was lucky,” Harry declares. Louis continues Johnny Favorite’s story, telling Harry that Johnny wasn’t lucky. “He returned home a zombie. His friends had him transferred to a private hospital upstate. There was some sort of radical psychiatric treatment involved. His lawyers had the power of attorney to pay the bills, things like that, but you know how it is. He remained a vegetable, and my contract was never honored…I don't want to sound mercenary. My only interest in Johnny is in finding out if he's alive or dead,” Cyphre insists. “Each year, my office receives a signed affidavit confirming that Johnny Liebling is indeed among the living, but last weekend Monsieur

Cyphre and I, just by chance, were near the clinic in Poughkeepsie. We decided to check for ourselves, but we got misleading information,” Winesap informs Harry. “I didn't want to cause a scene, I hate any sort of fuss. I thought, perhaps you could subtly and in a quiet manner…,” Cyphre doesn't have to finish his sentence. “You want me to check it out,” Angel surmises as he accepts the case. He rises and shakes Cyphre’s hand. ”I have a feeling I've met you before,” Cyphre tells Harry, but Harry doesn’t think so. Admittedly, the first time I saw Angel Heart, I figured out the twist before its reveal, but not this early though it’s so obvious in retrospect that I don’t see how I missed it. With two more recent films with twists, Fight Club and The Sixth Sense, I knew their secrets before I saw them. In the case of David Fincher’s satiric masterpiece, I don’t think I would have figured out its twist on my own, but knowing that going in allowed me to watch more closely as I watched the film and admire it all the more. As for The Sixth Sense, I honestly don’t get why it wasn’t obvious to everyone who saw it that Bruce Willis’ character was dead all along. I also could watch that film more closely for the signs, but it didn't prevent dissatisfaction with the whole. Lots of movies stick pivotal scenes at the very start, be it another 1987 release such as No Way Out with Kevin Costner or Evil Under the Sun, the second Agatha Christie adaptation that had Peter Ustinov play Hercule Poirot, hoping that the scene slips the audience’s mind so when the film finally comes back to it, they are surprised. That’s the curse of my good memory. I remembered that odd scene of Costner in the room yelling at a two-way mirror, asking when they were going to come out, and guessed early that he indeed worked as a Russian mole. The entire time I watched the overrated Sixth Sense, I kept coming back to the first scene and wondering, “What happened to that deal with the patient that shot Willis in his bedroom?” Angel Heart lacks any scene like that, but the clues get placed before the moviegoer early and often and it’s a tribute to the skills of all involved that it engaged me to the point that I didn’t catch the hints until much later than I should have otherwise.

Cyphre and I, just by chance, were near the clinic in Poughkeepsie. We decided to check for ourselves, but we got misleading information,” Winesap informs Harry. “I didn't want to cause a scene, I hate any sort of fuss. I thought, perhaps you could subtly and in a quiet manner…,” Cyphre doesn't have to finish his sentence. “You want me to check it out,” Angel surmises as he accepts the case. He rises and shakes Cyphre’s hand. ”I have a feeling I've met you before,” Cyphre tells Harry, but Harry doesn’t think so. Admittedly, the first time I saw Angel Heart, I figured out the twist before its reveal, but not this early though it’s so obvious in retrospect that I don’t see how I missed it. With two more recent films with twists, Fight Club and The Sixth Sense, I knew their secrets before I saw them. In the case of David Fincher’s satiric masterpiece, I don’t think I would have figured out its twist on my own, but knowing that going in allowed me to watch more closely as I watched the film and admire it all the more. As for The Sixth Sense, I honestly don’t get why it wasn’t obvious to everyone who saw it that Bruce Willis’ character was dead all along. I also could watch that film more closely for the signs, but it didn't prevent dissatisfaction with the whole. Lots of movies stick pivotal scenes at the very start, be it another 1987 release such as No Way Out with Kevin Costner or Evil Under the Sun, the second Agatha Christie adaptation that had Peter Ustinov play Hercule Poirot, hoping that the scene slips the audience’s mind so when the film finally comes back to it, they are surprised. That’s the curse of my good memory. I remembered that odd scene of Costner in the room yelling at a two-way mirror, asking when they were going to come out, and guessed early that he indeed worked as a Russian mole. The entire time I watched the overrated Sixth Sense, I kept coming back to the first scene and wondering, “What happened to that deal with the patient that shot Willis in his bedroom?” Angel Heart lacks any scene like that, but the clues get placed before the moviegoer early and often and it’s a tribute to the skills of all involved that it engaged me to the point that I didn’t catch the hints until much later than I should have otherwise.So Harry Angel embarks on his investigation to find out what happened to Johnny Liebling nee Favorite after the war. He starts his search where Cyphre and Winesap got the "run-around" — The Sarah Dodds Harvest Memorial Clinic in Poughkeepsie. Pretending to be from the National Institute [sic] of Health, Harry inquires if they have Jonathan Liebling. The nurse (Kathleen Wilhoite) at the reception window tells Harry that he can't see a patient without an appointment, but Angel explains he just needs to know if he's "on the right track."

Checking the files, the nurse informs Harry that Liebling once was a patient there but was transferred to another hospital. Spinning the file around so that Harry can see, the transfer date, written in pen, reads 12/31/43 and an Albert Fowler signed the form. Harry points out to the nurse that whoever wrote the transfer note did it with a ballpoint pen — and ballpoints weren't around in the U.S. in 1943. He asks her if this Dr. Fowler still works at the clinic, but she says he only does part-time now. Harry finds Fowler's house, but the old doctor isn't there, so he breaks in and waits. Snooping in the meantime, he discovers a huge stash of morphine in Fowler's refrigerator. When Fowler (Michael Higgins) returns home, he threatens to call the police but Harry doubts he'll do that with his "opium den" and grills him about Johnny Favorite. The doctor lies and says he transferred him to a VA hospital in Albany, but Angel shoots that theory down. Fowler obviously needs a fix, but Harry won't let him have one until he gives him something he can

Checking the files, the nurse informs Harry that Liebling once was a patient there but was transferred to another hospital. Spinning the file around so that Harry can see, the transfer date, written in pen, reads 12/31/43 and an Albert Fowler signed the form. Harry points out to the nurse that whoever wrote the transfer note did it with a ballpoint pen — and ballpoints weren't around in the U.S. in 1943. He asks her if this Dr. Fowler still works at the clinic, but she says he only does part-time now. Harry finds Fowler's house, but the old doctor isn't there, so he breaks in and waits. Snooping in the meantime, he discovers a huge stash of morphine in Fowler's refrigerator. When Fowler (Michael Higgins) returns home, he threatens to call the police but Harry doubts he'll do that with his "opium den" and grills him about Johnny Favorite. The doctor lies and says he transferred him to a VA hospital in Albany, but Angel shoots that theory down. Fowler obviously needs a fix, but Harry won't let him have one until he gives him something he can use, like where Johnny is now. "Some people came one night years ago. He got in the car with them and left," Fowler confesses. Harry inquires how a man who reportedly was in a vegetative state managed to get into a car. "At first, he was in a coma, but he quickly recovered," Fowler tells him, adding that Valentine still had amnesia. Harry pumps him for details about the friends. The doctor says the man was named Edward Kelley, but he didn't know about the woman because she stayed in the car. He believes they went Down South. They paid Fowler off to keep up the charade that Valentine remained in the clinic. Harry decides he could use some food and Fowler could clear his head so he helps the doctor to his bedroom, promising a fix when he returns, locking the doc in his room in the meantime. After a cheeseburger in a diner, Harry returns to Fowler's, grabs a bottle of morphine from the fridge and heads upstairs. He unlocks the bedroom door and finds Fowler dead, apparently a suicide, clutching a photograph and a Bible. Harry strikes a match off Fowler's shoe and wipes his prints off everything. When he wipes off the Bible, it opens and turns out to be hollowed out with bullets inside. Fowler will be just the first of many stiffs that cross Harry's path on what one could call the ultimate journey to find yourself.

use, like where Johnny is now. "Some people came one night years ago. He got in the car with them and left," Fowler confesses. Harry inquires how a man who reportedly was in a vegetative state managed to get into a car. "At first, he was in a coma, but he quickly recovered," Fowler tells him, adding that Valentine still had amnesia. Harry pumps him for details about the friends. The doctor says the man was named Edward Kelley, but he didn't know about the woman because she stayed in the car. He believes they went Down South. They paid Fowler off to keep up the charade that Valentine remained in the clinic. Harry decides he could use some food and Fowler could clear his head so he helps the doctor to his bedroom, promising a fix when he returns, locking the doc in his room in the meantime. After a cheeseburger in a diner, Harry returns to Fowler's, grabs a bottle of morphine from the fridge and heads upstairs. He unlocks the bedroom door and finds Fowler dead, apparently a suicide, clutching a photograph and a Bible. Harry strikes a match off Fowler's shoe and wipes his prints off everything. When he wipes off the Bible, it opens and turns out to be hollowed out with bullets inside. Fowler will be just the first of many stiffs that cross Harry's path on what one could call the ultimate journey to find yourself.As Harry told Cyphre and Winesap, his cases usually involved divorces and insurance, nothing heavy — and nothing weighs heavier than a corpse such as Dr. Fowler's. Harry's prepared to tell Cyphre what he knows when he meets him at a tiny Brooklyn eatery and then wash his hands of this case. He informs Cyphre, who plays with a dish of hard-boiled eggs, about what he learned concerning this Edward Kelley taking Johnny Favorite away while paying Fowler all these years to make it appear as if he still resided in the Poughkeepsie clinic. It's that great scene I alluded to earlier involving De Niro's manipulation of the egg. YouTube has the clip but, alas, embedding isn't allowed so click here and watch, then return. Of course, Cyphre convinces Harry to stay on the case. Besides — what would happen with the rest of the

movie if he quit? I've never read Falling Angel but despite the changes that Parker acknowledges, I imagine the essential plot remains the same. Harry Angel hunts for Johnny Valentine and in a standard thriller, you could say that Valentine really serves as the MacGuffin, but Angel Heart pulls off something that not even Hitchcock tried. Sure, Norman assume his mother's identity in Psycho and Judy pretended to be Madeleine in Vertigo, but both are a far cry from Angel Heart where the MacGuffin actually is the main character, Harry Angel. He's hunting down himself and he's not aware of it. De Niro's Devil knows the whole time, but the people who aided Jonathan Liebling must pay a price and who better to deliver the bill than Johnny himself, unaware of what he's doing. Of course, selling your soul to the devil is an old story, but an innocent whose life becomes possessed by someone malevolent, even though Johnny Valentine appears just to be a rotten human being, foreshadows the inhabiting spirits, specifically BOB, of Twin Peaks who would commit heinous acts while in control of poor Leland Palmer, but Leland would have no memory until BOB exits and Leland's dying. When Harry gets together for a sexualromp with Epiphany Proudfoot (Lisa Bonet), the offspring of Johnny Valentine and a voodoo-practicing woman, he doesn't realize until it's after the fact — just like Leland — that he raped and murdered his own daughter. In a lot of ways, looking at Angel Heart now, it seems to portend some of the Lynchian trademarks that wouldn't really come to fruition until Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart. Blue Velvet debuted almost six months before Angel Heart, but for me it looks like a rough draft for the David Lynch template that he'd start perfecting in the '90s, especially with the large menagerice of eccentric characters.

movie if he quit? I've never read Falling Angel but despite the changes that Parker acknowledges, I imagine the essential plot remains the same. Harry Angel hunts for Johnny Valentine and in a standard thriller, you could say that Valentine really serves as the MacGuffin, but Angel Heart pulls off something that not even Hitchcock tried. Sure, Norman assume his mother's identity in Psycho and Judy pretended to be Madeleine in Vertigo, but both are a far cry from Angel Heart where the MacGuffin actually is the main character, Harry Angel. He's hunting down himself and he's not aware of it. De Niro's Devil knows the whole time, but the people who aided Jonathan Liebling must pay a price and who better to deliver the bill than Johnny himself, unaware of what he's doing. Of course, selling your soul to the devil is an old story, but an innocent whose life becomes possessed by someone malevolent, even though Johnny Valentine appears just to be a rotten human being, foreshadows the inhabiting spirits, specifically BOB, of Twin Peaks who would commit heinous acts while in control of poor Leland Palmer, but Leland would have no memory until BOB exits and Leland's dying. When Harry gets together for a sexualromp with Epiphany Proudfoot (Lisa Bonet), the offspring of Johnny Valentine and a voodoo-practicing woman, he doesn't realize until it's after the fact — just like Leland — that he raped and murdered his own daughter. In a lot of ways, looking at Angel Heart now, it seems to portend some of the Lynchian trademarks that wouldn't really come to fruition until Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart. Blue Velvet debuted almost six months before Angel Heart, but for me it looks like a rough draft for the David Lynch template that he'd start perfecting in the '90s, especially with the large menagerice of eccentric characters.

Those characters start coming to the forefront as Harry makes his way to New Orleans. Even before that, we encounter the blatant "give me" preaching of Pastor John (Gerald L. John) who opens tells his parishioners that if they love God, he shouldn't be driving a Cadillac, he should be driving a Rolls-Royce. Harry's investigative trail takes him to old musician Spider Simpson (Charles Gordons), whose band Johnny used to play with, in a resting home (providing some of those doddering old folks that Lynch would revel in) who sends him to Coney Island chasing a gypsy fortune teller named Madame Zora. Despite Parker's insistence that he wanted to make a black and white film in color, Michael Seresin paints some bright and beautiful beach scenes when he meets with two more leads, Izzy (George Buck) and his wife (Judith Drake) who stands in the ocean in the belief it helps her varicose veins, even though Izzy says she hates the water. The Izzy conversation proves hysterical as he likes to give away nose shields from a box he found beneath the Boardwalk. Harry notes there isn't much sun. "Yeah, but it keeps the rain off too," Izzy tells him. He remembers Zora and his Baptist wife knew her well. Toward the end of their talk, Harry asks Izzy what he does in the summertime. "Bite the heads off of rats," he answers. "What do you do in the winter?" Harry inquires. "Same," Izzy replies, scratching his balls. His wife lets him know that Madame Zora is the same person as a Louisiana heiress named Margaret Krusemark. "She wasn't a gypsy, she was a debutante," the wife informs Angel. The wonderful but woefully underused Charlotte Rampling plays Margaret.

The cast of interesting characters stretches further than those. There's Stocker Fontelieu as Ethan Krusemark, Margaret's wealthy and connected daddy who ends up explaining the whole situation to Harry. We even get an early role by Pruitt Taylor Vince as one of the

detectives aggravating Harry about the bodies that keep popping up connected to him. I made a reference earlier to Lisa Bonet's role. Harry first meets Epiphany with her infant son as she visits the grave of her mother, Evangeline Proudfoot, Johnny's secret lover. "Your mom left you with a very pretty name, Epiphany," Harry tells her. "And not much else," she replies. It seems so funny now how controversial it was at the time that she made this movie and ended up getting her booted off The Cosby Show because of her heavy duty sex scene with Mickey Rourke, soiling Denise Huxtable's

detectives aggravating Harry about the bodies that keep popping up connected to him. I made a reference earlier to Lisa Bonet's role. Harry first meets Epiphany with her infant son as she visits the grave of her mother, Evangeline Proudfoot, Johnny's secret lover. "Your mom left you with a very pretty name, Epiphany," Harry tells her. "And not much else," she replies. It seems so funny now how controversial it was at the time that she made this movie and ended up getting her booted off The Cosby Show because of her heavy duty sex scene with Mickey Rourke, soiling Denise Huxtable's innocent image. Apparently, the elaborate voodoo dance number where she appears to sacrifice a chicken and bathe her breasts in its blood was OK. (Interestingly enough, the same person staged the elaborate voodoo dance ritual as did the dance numbers in Fame — the late Louis Falco.) I wonder what would have happened if the story of Bill Cosby paying for the child of his former mistress had been revealed while the show had been on the air. Would he have kicked himself off the show? On the DVD, Parker admits that coming from England, he knew nothing of The Cosby Show or who Bonet was when he cast her. He said they all took great care to protect Bonet, then 19, when time came to film the explicit scene, but she exhibited fewer nerves than anyone else. Bonet, like most of the cast, got some good dialogue. Parker didn't write many of his films (and other than Bugsy Malone, the ones he did tended to be his lesser ones such as Come See the Paradise, The Road to Welville and Evita), but if he's telling the truth and he didn't take that much dialogue from the novel, he came up with a lot of keepers here. Before Harry and Epiphany couple, he asks her what her mother said about Valentine. "She once said that Johnny Valentine was as close to true evil as she ever wanted to be," Epiphany answers, adding that Evangeline called Johnny the best lover she ever had to which Harry shrugs as if to say, "That figures." Epiphany recognizes his reaction and tells him, "It's always the badass that makes a girl's heart beat faster."

innocent image. Apparently, the elaborate voodoo dance number where she appears to sacrifice a chicken and bathe her breasts in its blood was OK. (Interestingly enough, the same person staged the elaborate voodoo dance ritual as did the dance numbers in Fame — the late Louis Falco.) I wonder what would have happened if the story of Bill Cosby paying for the child of his former mistress had been revealed while the show had been on the air. Would he have kicked himself off the show? On the DVD, Parker admits that coming from England, he knew nothing of The Cosby Show or who Bonet was when he cast her. He said they all took great care to protect Bonet, then 19, when time came to film the explicit scene, but she exhibited fewer nerves than anyone else. Bonet, like most of the cast, got some good dialogue. Parker didn't write many of his films (and other than Bugsy Malone, the ones he did tended to be his lesser ones such as Come See the Paradise, The Road to Welville and Evita), but if he's telling the truth and he didn't take that much dialogue from the novel, he came up with a lot of keepers here. Before Harry and Epiphany couple, he asks her what her mother said about Valentine. "She once said that Johnny Valentine was as close to true evil as she ever wanted to be," Epiphany answers, adding that Evangeline called Johnny the best lover she ever had to which Harry shrugs as if to say, "That figures." Epiphany recognizes his reaction and tells him, "It's always the badass that makes a girl's heart beat faster."

As I mentioned early on, Parker said that rewatching the film for him was like seeing it for the first time. Parts of it did play like that for me with the exception of one character and the person who played him, who wasn't even an actor by trade. I forget who spoke the words but I remember a critic once saying that the mark of a memorable character was when the character's name stayed with you long after you'd finished watching the movie. It's 25 years, give or take, since I don't recall how soon I saw Angel Heart after its opening, and Toots Sweet remains vivid in my mind. It's a small role, a musician who played with Johnny Valentine and takes part in the voodoo rituals, portrayed by a real blues legend, Brownie McGhee. In real life, McGhee was known both for his solo work and his longtime musical partnership with blind harmonica player Sonny Terry. Harry offers to buy Toots a drink when he takes a break from his set,

but Toots gets his drinks comped and takes a very special order. "Two Sisters cocktails. I don't know what's in it but gives a bigger kick than six stingers," Toots tells him. When Harry reminds him of Spider Simpson, Toots recalls, "I remember Spider. He used to play his drums like jack rabbits fuckin'." He then excuses himself for the rest room before has to play again. "A piss and a spit and back to work," the musician says, but Harry follows him and pushes for information and Toots finds the warning of a chicken foot in the toilet. He'll eventually become one of the string of bodies, dying in a particularly graphic way, but in his brief time in the movie, McGhee's Toots Sweet has stayed with me for a long