Thursday, October 10, 2013

Better Off Ted: Bye Bye 'Bad' Part III

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now. If you missed Part I, click here. If you missed Part II, click here.

— Saul Goodman to Mike Ehrmantraut ("Buyout," written by Gennifer Hutchison, directed by Colin Bucksey)

By Edward Copeland

Playing to the back of the room: I love doing it as a writer and appreciate it even more as an audience member. While I understand how its origin in comedy clubs gives it a derogatory meaning, I say phooey in general. Another example of playing to the broadest, widest audience possible. Why not reward those knowledgeable ones who pay close attention? Why cater to the Michele Bachmanns of the world who believe that ignorance is bliss? What they don’t catch can’t hurt them. I know I’ve fought with many an editor about references that they didn’t get or feared would fly over most readers’ heads (and I’ve known other writers who suffered the same problems, including one told by an editor decades younger that she needed to explain further whom she meant when she mentioned Tracy and Hepburn in a review. Being a free-lancer with a real full-time job, she quit on the spot). Breaking Bad certainly didn’t invent the concept, but damn the show did it well — sneaking some past me the first time or two, those clever bastards, not only within dialogue, but visually as well. In that spirit, I don’t plan to explain all the little gems I'll discuss. Consider them chocolate treats for those in the know. Sam, release the falcon!

In a separate discussion on Facebook, I agreed with a friend at taking offense when referring to Breaking Bad as a crime show. In fact, I responded:

“I think Breaking Bad is the greatest dramatic series TV has yet produced, but I agree. Calling it a ‘crime show’ is an example of trying to pin every show or movie into a particular genre hole when, especially in the case of Breaking Bad, it has so many more layers than merely crime. In fact, I don't like the fact that I just referred to it as a drama series because, as disturbing, tragic and horrifying as Breaking Bad could be, it also could be hysterically funny. That humor also came in shapes and sizes across the spectrum of humor. Vince Gilligan's creation amazes me in a new way every time I think about it. I wonder how long I'll still find myself discovering new nuances or aspects to it. I imagine it's going to be like Airplane! — where I still found myself discovering gags I hadn't caught years and countless viewings after my initial one as an 11-year-old in 1980. Truth be told, I can't guarantee I have caught all that ZAZ placed in Airplane! yet even now. Can it be a mere coincidence that both Breaking Bad and Airplane! featured Jonathan Banks? Surely I can't be serious, but if I am, tread lightly.”

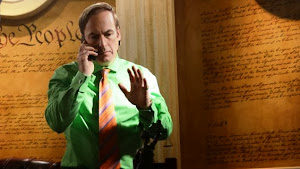

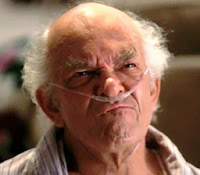

— Jonathan Banks as air traffic controller Gunderson in Airplane!

The second season episode “ABQ” (written by Vince Gilligan, directed by Adam Bernstein) introduced us to Banks as Mike and also featured John de Lancie as air traffic controller Donald Margulies, father of the doomed Jane. Listen to the DVD commentary about a previous time that Banks and De Lancie worked together. Speaking of air traffic controllers, if you don’t already know, look up how a real man named Walter White figured in an airline disaster. Remember Wayfarer 515! Saul never did, wearing that ribbon nearly constantly. Most realize the surreal pre-credit scenes that season foretold that ending cataclysm and where six of its second season episode titles, when placed together in the correct order, spell out the news of the disaster. Breaking Bad’s knack for its equivalent of DVD Easter eggs extended to episode titles, which most viewers never knew unless they looked them up. Speaking of Saul Goodman, he provided the voice for a multitude of Breaking Bad’s pop culture references from the moment the show introduced his character in season two’s “Better Call Saul” (written by Peter Gould, directed by Terry McDonough). Once he figures out (and it doesn’t take long) that Walt isn’t really Jesse’s uncle and pays him a visit in his high school classroom, the attorney and his client discuss a more specific role

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.

players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.As I admitted, some of the nice touches escaped my notice until pointed out to me later. Two of the most obvious examples occurred in the final eight episodes. One wasn’t so much a reference as a callback to the very first episode that you’d need a sharp eye to spot. It occurs in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson) and I’d probably never noticed if not for a synched-up commentary track that Johnson did for the episode on The Ones Who Knock weekly podcast on Breaking Bad. He pointed out that as Walt rolls his barrel of $11 million through the desert (itself drawing echoes to Erich von Stroheim’s silent classic Greed and its lead character McTeague — that one I had caught) he passes the pair of pants he lost in the very first episode when they flew through the air as he frantically drove the RV with the presumed dead Krazy-8 and Emilio unconscious in the back. Check the still below, enlarged enough so you don’t miss the long lost trousers.

The other came when psycho Todd decided to give his meth cook prisoner Jesse ice cream as a reward. I wasn’t listening closely enough when he named one of the flavor choices as Ben & Jerry’s Americone Dream, and even if I’d heard the flavor’s name, I would have missed the joke until Stephen Colbert, whose name serves as a possessive prefix for the treat’s flavor, did an entire routine on The Colbert Report about the use of the ice cream named for him giving Jesse the strength to make an escape attempt. One hidden treasure I did not know concerned the appearance of the great Robert Forster as the fabled vacuum salesman who helped give people new identities for a price. Until I read it in a column on the episode “Granite State” (written and directed by Gould), I had no idea that in real life Forster once actually worked as a vacuum salesman.

Seeing so many episodes multiple times, the callbacks to previous moments in the series always impressed me. I didn’t recall until AMC held its marathon prior to the finale and I caught the scene where Skyler caught Ted about him cooking his company’s books in season two’s “Mandala” (written by Mastras, directed by Adam Bernstein),

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.I wanted this tribute to be so much grander and better organized, but my physical condition thwarted my ambitions. I doubt seriously my hands shall allow me to complete a fourth installment. (If you did miss Part I or Part II, follow those links.) While I hate ending on a patter list akin to a certain Billy Joel song, (I let you off easy. I almost referenced Jonathan Larson — and I considered narrowing the circle tighter by namedropping Gerome Ragni

& James Rado.) I feel I must to sing my hosannas to the actors, writers, directors and other artists who collaborated to realize the greatest hour-long series in

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

In fact, the series failed me only twice. No. 1: How can you dump the idea that Gus Fring had a particularly mysterious identity in the episode “Hermanos” and never get back to it? No. 2: That great-looking barrel-shaped box set of the entire series only will be made on Blu-ray. As someone of limited means, it would need to be a Christmas gift anyway and for the same reason, I never made the move to Blu-ray and remain with DVD. Medical bills will do that to you and, even if tempting or plausible, it’s difficult to start a meth business to fund it while bedridden. Despite those two disappointments, it doesn’t change Breaking Bad’s place in my heart as the best TV achievement so far. How do I know this? Because I say so.

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Cranston, D. Zucker, De Palma, Deadwood, Hackman, Hawks, HBO, J. Zucker, Jim Abrahams, K. Hepburn, O'Toole, Oliver Stone, Tracy, Treme, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, March 10, 2012

Bringing Up Babs

By Damian Arlyn

I remember working in the video store one day when a regular customer came in to check out a few titles. He glanced at the enormous flat screen we had behind the counter, saw Barbra Streisand belting out some catchy show tune and uttered a question I got asked a lot in those days. "What are you watching?" he said. "Hello, Dolly!" I answered. He smiled, shook his head and exclaimed, "See, now, here's where I break with the stereotype. I'm a gay guy who doesn't like Barbra Streisand." I just laughed and replied, "That's OK. I'm a straight guy who does."

And it's true. Although she is by no means my favorite actress (nor would I ever see a film simply because she's in it), I happen to enjoy watching her onscreen. Funny Girl, Meet the Fockers and the aforementioned Hello, Dolly! are all films I love, but my favorite movie of hers would have to be the hilarious What's Up, Doc? which celebrates its 40th anniversary today. Nowhere is Babs' gift for comedy and sheer charisma on display better than in this film. They even find an excuse to show off her incredible voice once or twice: namely, in the film's opening and ending credits where she sings Cole Porter's "You're The Top" as well as the scene at the piano when she croons a few lines of "As Time Goes By."

It also doesn't hurt that What's Up, Doc? happens to be a really great movie. Hot off of his success with The Last Picture Show, Peter Bogdanovich originally conceived it as a remake of Howard Hawks' Bringing Up Baby, but wisely decided (much as Lawrence Kasdan would do later with his film noir tribute Body Heat) to use Hawks' film merely as an inspiration rather than a template and to give What's Up, Doc? its own identity. As a result, it comes off more as a love letter to screwball comedies in general as well as to iconic Warner Bros. feature films (such as Casablanca) and classic animated shorts. Hence, when Barbra's character, Judy Maxwell, is introduced first to Ryan O'Neal's nerdy Howard Bannister, she's seen munching on a carrot a la Bugs Bunny and/or Clark Gable from It Happened One Night. With her brash, fast-talking, trouble-making personality and his stiff, bespectacled, long-suffering demeanor, the two leads clearly are based on Baby's Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn. (Interestingly, Streisand shared a best actress Oscar with Ms. Hepburn only four years earlier in one of the Academy's rare ties. Streisand won for her film debut in Funny Girl while Hepburn earned her third best actress trophy for The Lion in Winter. Hepburn's prize was her second consecutive win in the category having taken the 1967 Oscar for Guess Who's Coming to Dinner.) Aside from Judy constantly getting Howard into trouble and a reminiscent coat-tearing gag, the similarities between Doc and Baby essentially end there.

Also, What's Up, Doc? lacks a leopard. Instead the chaos revolves around four identical carrying cases containing such varied items as clothes, rocks, jewels and classified government documents. When moviegoers first see the quartet of cases at the start of Doc, it's the filmmakers signaling audiences that much confusion and hilarity awaits. At this point I have to confess that, although I've seen the film at least a dozen times, I cannot to this day follow which case is which throughout the course of the film. Every time I sit down to watch, I swear I'm going to keep track of the cases, but I always give up about 20 minutes into it. I take some comfort, however, from the fact that even the great Buck Henry, in the process of re-writing the screenplay, reportedly phoned Bogdanovich to say, "I've lost one of the suitcases. It's in the hotel somewhere, but I don't know where I put it."

The gags come fast and furious in What's Up, Doc? More than a decade before Bruce Willis and Bogdanovich's ex-girlfriend Cybill Shepherd resurrected rapid-fire banter on TV's Moonlighting, Streisand and O'Neal fire a barrage of zingers at each other so quickly that you're almost afraid to laugh for fear you'll miss the next one. The behind-the-scenes team also populates the What's Up, Doc? universe with a whole host of kooky characters, each bringing his or her unique comic flair to those roles. There isn't a single boring person in What's Up, Doc? Everyone (right down to the painter who drops his cigar into the bucket) amuses. At the top of the heap resides the great Madeline Kahn in her feature film debut as Howard's frumpy fiancée Eunice Burns. Two years before she joined Mel Brooks' cinematic comedy troupe, she proved to the world her status as one of the funniest women ever to grace the silver screen. Another Mel Brooks' regular, Kenneth Mars, plays Hugh Simon, providing yet one more strangely accented flamboyant nutball to his immense repertoire. A very young Randy Quaid, a brief M. Emmet Walsh and a very annoyed John Hillerman also show up in hilarious bit parts.

All of this anarchy culminates in a spectacular car chase through the streets of San Francisco that actually rivals the one from Bullitt. Apparently it took four weeks to shoot, cost $1 million (¼ of the film's budget) and even managed to get the filmmakers in trouble with the city for destroying some of its property without permission. Nevertheless, Bogdanovich pulls out all the stops in creating this over-the-top action/slapstick set piece that overflows with both thrills and laughs. When watching it, one can't help but be reminded that physical comedy on this grand of a scale doesn't even get attempted anymore. One wishes another director would resurrect the kind of awesome stunt-comedy on display here and in The Pink Panther series.

The film's dénouement takes place in a courtroom where an embittered, elderly judge (the brilliant Liam Dunn) hears the arguments of everyone involved and tries to make sense of it all. Howard's attempt to explain only serves to frustrate and confuse the judge further and results in this gem of an exchange that owes more than a little bit to Abbott & Costello's "Who's on First?":

HOWARD: First, there was this trouble between me and Hugh.

JUDGE: You and me?

HOWARD: No, not you. Hugh.

HUGH: I am Hugh.

JUDGE: You are me?

HUGH: No, I am Hugh.

JUDGE: Stop saying that. [to bailiff] Make him stop saying that!

HUGH: Don't touch me, I'm a doctor.

JUDGE: Of what?

HUGH: Music.

JUDGE: Can you fix a hi-fi?

HUGH: No, sir.

JUDGE: Then shut up!

The tag line for What's Up, Doc? read: "A screwball comedy. Remember them?" Well, whether people remembered screwball comedy or simply discovered it for the first time, they certainly embraced the film as it was an enormous success upon its release. It took in $66 million in North America alone and became the third-highest grossing film of the year. Since The Last Picture Show was released in late '71 and Doc came out in early '72, Bogdanovich had two hugely successful films playing in theaters at the same time. Unfortunately, his career, which had just started to rise, also had neared its peak. Although he would follow Doc with Paper Moon his directing career would only see sporadic critical successes after that such as Saint Jack and Mask. He even filmed Texasville, the sequel to The Last Picture Show, but he'd never again see the kind of commercial or critical success he had achieved in the early 1970s. Bogdanovich would eventually end up working in television, often as an actor such as his long recurring role as Dr. Elliot Kupferberg, psychiatrist to Dr. Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) on The Sopranos. The most recent feature film he directed was 2001's fairly well-received The Cat's Meow starring Kirsten Dunst as Marion Davies and Edward Herrmann as William Randolph Hearst. Based on a play of the same name, The Cat's Meow concerned a real-life mystery in 1924 Hollywood involving the shooting death of writer/producer/director Thomas Ince (Cary Elwes) on Hearst's yacht.

When Bogdanovich was good, he was great and What's Up, Doc? is, in my opinion, the jewel in his crown. It made a once-forgotten genre popular again, it jump-started a lot of comic careers and it reminded us all that love meaning never having to say we're sorry is the dumbest thing we've ever heard.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Abbott and Costello, Bogdanovich, Buck Henry, Cary, Cole Porter, Cybill Shepherd, Dunst, Gable, Hawks, K. Hepburn, L. Kasdan, Mel Brooks, Movie Tributes, R. Quaid, Streisand, The Sopranos, Willis

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, March 04, 2012

Pearl Tributes: Rex Hamilton

By Edward Copeland

No, Rex Hamilton isn't really 30 years old, but today marks the pearl anniversary of his most famous performance. Sure, many fine actors have taken a shot at playing our 16th president — Ralph Ince, Benjamin Chapin and Francis Ford practically made entire careers out of playing Honest Abe in film after film after film during the silent era. Among the better-known names to don the stovepipe hat on the big screen and TV include Walter Huston, John Carradine, Henry Fonda, Raymond Massey, Hal Holbrook, Gregory Peck, Jason Robards and Sam Waterston. Many of those names would return to the role again and again — and we still haven't even seen Daniel Day-Lewis' take in Steven Spielberg's upcoming film. What none of these greats had that made Hamilton's portrait of Lincoln so much richer than any Lincoln before or since was his supporting cast: Ed Williams as Ted Olson; the great, recently passed William Duell as Johnny; Mission: Impossible veteran Peter Lupus as Officer Norberg; Alan North as Capt. Ed Hocken and, most importantly, Leslie Nielsen as Sgt. Frank Drebin, Detective Lieutenant, Police Squad! — a special division of the police force.

The writing-directing team of brothers David and Jerry Zucker and Jim Abrahams couldn't have been hotter following the surprise hit of their no-holds-barred comedy Airplane! Made for a mere $3.5 million, it tallied a domestic gross of $83,453,539 and became the fourth-biggest moneymaker of 1980. Paramount Pictures, headed then by Michael Eisner, was eager to work with the boys again. ZAZ (shorthand for the trio) had an idea to make a parody of old TV police dramas, but Paramount had offered them such a small window they couldn't figure out a way to turn the idea into a 90-minute script. Someone suggested that if they were spoofing a type of television show, why not make a television show? The idea appealed to them immediately since it meant having to produce a shorter script. According to commentaries on the DVD on two of the episodes by ZAZ and producer Robert Weiss (whose voices all sound terribly alike and hard to distinguish from each other), they sold the Police Squad! idea to ABC based on the opening credits sequence alone. As Airplane! took its premise from the 1957 film Zero Hour! (so much so that the rights to that film had to be acquired), Police Squad! was loosely based on the police drama M Squad that ran from 1957-1960 and starred Lee Marvin. Below are two YouTube clips. First, watch the memorable opening to Police Squad!, and then below it, the credits to M Squad, and see how closely ZAZ aped it, right down to the music.

The opening credits alone leave much to discuss. First, anyone old enough to remember series from the 1960s and 1970s such as Barnaby Jones, Cannon, The Fugitive and The Streets of San Francisco recalls the announcer who would proclaim the series "A Quinn Martin Production" as well as informing the viewer the title of the night's episode. In yet another instance of inaccuracy and inconsistency found on the Incompetent Movie Database, the entry for Police Squad! claims the narrator was Marvin Miller. However, the Quinn Martin announcer was Hank Simms, who IMDb also identifies as the narrator on Police Squad!, a fact verified by multiple sources across the Internet. You don't find Miller's name associated with Police Squad! anywhere else. The other distinctions that need to be pointed out about the credits is that when Simms announces the title, as in the premiere when he says, "Tonight's episode: The Broken Promise," on screen it would read, "tonight's episode: A SUBSTANTIAL GIFT." All six episodes had dual titles like that. Then there were the special guest

stars. In the clip, from the first episode, you saw it was Lorne Greene who rolled out of a car, a knife in his chest. It's never mentioned again. That happened each week with the special guest stars who always would be killed off and have nothing to do with the rest of that episode's story. In the second episode, they dropped a safe on Georg Stanford Brown, who made his name as an actor on The Rookies and went on to direct, including the third episode of Police Squad! In the third episode, Robert Goulet, the eventual villain in The Naked Gun 2½, bought it in front of a firing squad. The fourth special guest star honors went to William Shatner who dines with a beautiful blonde when a barrage of gunfire opens up on him. Shatner ducks, gets back up and fires back. He then smiles at his date and sips his wine and starts grabbing his throat. He points at her before keeling over. The fifth guest star death had Florence Henderson spoofing her Wesson Oil "Wessonality" commercials of the time. She's on a kitchen set holding a plate of fried chicken singing "Put on a Happy Face" when a hail of gunfire mows her down and she lets out a high note. We see her foot kicking up above the kitchen counter before it ends. The final celebrity death went to none other than an actual Quinn Martin production — William Conrad, Frank Cannon himself, doing a virtual shot-by-shot recreation of the Lorne Greene scene. The public has never seen the most infamous celebrity death scene and no one

stars. In the clip, from the first episode, you saw it was Lorne Greene who rolled out of a car, a knife in his chest. It's never mentioned again. That happened each week with the special guest stars who always would be killed off and have nothing to do with the rest of that episode's story. In the second episode, they dropped a safe on Georg Stanford Brown, who made his name as an actor on The Rookies and went on to direct, including the third episode of Police Squad! In the third episode, Robert Goulet, the eventual villain in The Naked Gun 2½, bought it in front of a firing squad. The fourth special guest star honors went to William Shatner who dines with a beautiful blonde when a barrage of gunfire opens up on him. Shatner ducks, gets back up and fires back. He then smiles at his date and sips his wine and starts grabbing his throat. He points at her before keeling over. The fifth guest star death had Florence Henderson spoofing her Wesson Oil "Wessonality" commercials of the time. She's on a kitchen set holding a plate of fried chicken singing "Put on a Happy Face" when a hail of gunfire mows her down and she lets out a high note. We see her foot kicking up above the kitchen counter before it ends. The final celebrity death went to none other than an actual Quinn Martin production — William Conrad, Frank Cannon himself, doing a virtual shot-by-shot recreation of the Lorne Greene scene. The public has never seen the most infamous celebrity death scene and no one knows if it has been lost or purposely destroyed. ZAZ met with John Belushi, who jokingly suggested they film him lying dead with a needle in his arm. What they did film was him having rocks attached to his feet and then sinking below the water, bubbles coming out of his mouth and a fish swimming by. The eerie part is that during the filming, something went wrong with the air, and when they pulled him out of the water, he started choking. Once he was OK, everyone was joking about mock obits saying, "Belushi was best known for his work on Saturday Night Live…" Two weeks later, Belushi did die of an overdose, so they didn't air his cameo. They thought about putting it on the DVD, but the footage couldn't be found. Of course, Greene, Goulet and Conrad all have passed on now. On the DVD, it includes a two-page memo of proposed celebrity death ideas they had (if the show had gone on) that included a shark attack, getting on the Hindenburg and signing a contract with ABC. The final credit detail worth noting is that, according to the commentary, ABC was uncomfortable with a show that aired at 7 p.m. in some time zones having a man run through the squad room on fire. ZAZ ignored them, but ABC kept complaining, and after three episodes had aired with that footage, ABC made them remove it, which was dumb considering the show was pulled after the fourth episode. Apparently for the DVD, they just used the same credits with the burning man for all six episodes.

knows if it has been lost or purposely destroyed. ZAZ met with John Belushi, who jokingly suggested they film him lying dead with a needle in his arm. What they did film was him having rocks attached to his feet and then sinking below the water, bubbles coming out of his mouth and a fish swimming by. The eerie part is that during the filming, something went wrong with the air, and when they pulled him out of the water, he started choking. Once he was OK, everyone was joking about mock obits saying, "Belushi was best known for his work on Saturday Night Live…" Two weeks later, Belushi did die of an overdose, so they didn't air his cameo. They thought about putting it on the DVD, but the footage couldn't be found. Of course, Greene, Goulet and Conrad all have passed on now. On the DVD, it includes a two-page memo of proposed celebrity death ideas they had (if the show had gone on) that included a shark attack, getting on the Hindenburg and signing a contract with ABC. The final credit detail worth noting is that, according to the commentary, ABC was uncomfortable with a show that aired at 7 p.m. in some time zones having a man run through the squad room on fire. ZAZ ignored them, but ABC kept complaining, and after three episodes had aired with that footage, ABC made them remove it, which was dumb considering the show was pulled after the fourth episode. Apparently for the DVD, they just used the same credits with the burning man for all six episodes.Yes, as beloved as many hold Police Squad! and Frank Drebin now, and even though less than two years earlier the comedy style employed by Abrahams and the Zucker brothers — namely having every kind of comedy running simultaneously as a nonstop bombardment of visual gags, puns, wordplay, very literal language, slapstick and more — reaped huge rewards in Airplane!, when ZAZ took that technique to TV, Police Squad! flopped badly. ABC didn't help the matter with where they placed Police Squad! on their schedule: the first show on Thursday nights opposite Magnum, P.I. on CBS and Fame on NBC (Yes Virginia, there once were only three commercial networks), filling in for Mork & Mindy. I'm uncertain what aired there for a couple weeks following its four-episode run, but then another short-lived (and truly bizarre) show, No Soap Radio, occupied the slot until Mork returned in May. While their madness appeared to be a new style of humor, on the commentaries the creators freely credit the influences of the Marx Brothers, Ernie Kovacs and MAD magazine. The trio had the right man for their star in Leslie Nielsen. In an interview on the DVD, he talked about how when he was making Airplane!, he noticed the writing-directing team watching him very closely, especially during the scene where he's trying to lift the spirits of Ted Stryker (Robert Hays) by telling him about George Zipp ("I don't know where I'll be then — but it won't smell too good, that's for sure"). "I thought, 'You know, if they watch too much, they're gonna find out I'm a fraud.' But it never turned out that way because they were watching me because they had detected in me the same wavelength in humor that they had." Indeed, aside from a few exceptions such as an early, hilarious episode of M*A*S*H, Airplane! unleashed the comic actor in Nielsen that always existed and

Police Squad! sealed it. Rewatching the six episodes, while each episode had its share of funny bits, the premiere episode, the only episode actually written and directed by ZAZ, is a gem from beginning to end. It opens at ACME Finance Credit Union where Sally Decker (Kathryn Leigh Scott) argues with the teller Jim Johnson (Terry Wills) about skimming more money for her because she owes money to her dentist, but Jim won't steal anymore. Then poor Ralph Twice (Russell Shannon) comes in to cash his last paycheck after being laid off from his job at the tire factory, giving Sally an idea as she takes two guns from her desk. Viewers who didn't already realize this wasn't your average TV comedy started to realize it as they watched Sally prepare but still heard Jim ask Ralph the usual check-cashing questions: form of ID, two major credit cards, thumbprint. Then it gets odd as Jim asks Ralph to look into a camera, to turn his head and cough and, finally, to spread his toes. Sally finishes loading her guns and she shoots Ralph with one of them and he dies in horribly fake slow-motion before she shoots Jim with the other, though he's conscientious enough to finish his paperwork before falling dead. Sally makes it look like Ralph shot Jim in an attempted robbery, and then she shot him. This leads to Nielsen's introduction as Drebin as he's driving his car.

Police Squad! sealed it. Rewatching the six episodes, while each episode had its share of funny bits, the premiere episode, the only episode actually written and directed by ZAZ, is a gem from beginning to end. It opens at ACME Finance Credit Union where Sally Decker (Kathryn Leigh Scott) argues with the teller Jim Johnson (Terry Wills) about skimming more money for her because she owes money to her dentist, but Jim won't steal anymore. Then poor Ralph Twice (Russell Shannon) comes in to cash his last paycheck after being laid off from his job at the tire factory, giving Sally an idea as she takes two guns from her desk. Viewers who didn't already realize this wasn't your average TV comedy started to realize it as they watched Sally prepare but still heard Jim ask Ralph the usual check-cashing questions: form of ID, two major credit cards, thumbprint. Then it gets odd as Jim asks Ralph to look into a camera, to turn his head and cough and, finally, to spread his toes. Sally finishes loading her guns and she shoots Ralph with one of them and he dies in horribly fake slow-motion before she shoots Jim with the other, though he's conscientious enough to finish his paperwork before falling dead. Sally makes it look like Ralph shot Jim in an attempted robbery, and then she shot him. This leads to Nielsen's introduction as Drebin as he's driving his car. "My name is Sergeant Frank Drebin, Detective Lieutenant, Police Squad, a special detail of the police department. There'd been a recent wave of gorgeous fashion models found naked and unconscious in laundromats on the west side. Unfortunately, I was assigned to investigate holdups at neighborhood credit unions," he says in voiceover. When Drebin pulls up to the crime scene, his car crashes into a garbage can. They didn't end up getting to do it through all six episodes, but in each subsequent episode they would add a trash can for Drebin's car to strike, but for whatever reason the gag only got up to four cans in the fourth episode. The visual gags begin nonstop when he arrives and his boss, Capt. Ed Hocken (Alan North), awaits. One of the corpses is being brought out of the credit union on an insanely long gurney. As they go inside, they walk past the chalk outline of Ralph's body where there also is an Egyptian hieroglyphic on the floor. Someone takes a photo of a man posing on a bench with Ralph's corpse as Drebin and Hocken go to interview Sally, where Frank introduces himself with his third rank, this time captain. What follows is another great ZAZ variation on the classic Abbott & Costello "Who's on First?" routine, which they used in Airplane! among the pilot, co-pilot and navigator. It gives a great example of the absolute straight-faced style of Nielsen and North.

"My name is Sergeant Frank Drebin, Detective Lieutenant, Police Squad, a special detail of the police department. There'd been a recent wave of gorgeous fashion models found naked and unconscious in laundromats on the west side. Unfortunately, I was assigned to investigate holdups at neighborhood credit unions," he says in voiceover. When Drebin pulls up to the crime scene, his car crashes into a garbage can. They didn't end up getting to do it through all six episodes, but in each subsequent episode they would add a trash can for Drebin's car to strike, but for whatever reason the gag only got up to four cans in the fourth episode. The visual gags begin nonstop when he arrives and his boss, Capt. Ed Hocken (Alan North), awaits. One of the corpses is being brought out of the credit union on an insanely long gurney. As they go inside, they walk past the chalk outline of Ralph's body where there also is an Egyptian hieroglyphic on the floor. Someone takes a photo of a man posing on a bench with Ralph's corpse as Drebin and Hocken go to interview Sally, where Frank introduces himself with his third rank, this time captain. What follows is another great ZAZ variation on the classic Abbott & Costello "Who's on First?" routine, which they used in Airplane! among the pilot, co-pilot and navigator. It gives a great example of the absolute straight-faced style of Nielsen and North.Nielsen and this episode's writing earned Police Squad!'s only Emmy nominations. Nielsen was brilliant, playing Drebin more deadpan than he eventually would in the movies. In an interesting comparison to their inspiration, click here to watch a clip of Lee Marvin in an episode of M Squad alongside a young Leonard Nimoy. In his interview, Nielsen says he broached the idea of a movie when the show died so quickly, but ZAZ still couldn't imagine stretching it out for 90 minutes. At one point, there was talk of trying to edit the six episodes together into a feature. In fact, according to the ZAZ and Weiss commentary, that's what prompted the freeze frames at the end of each episode. It wasn't just to spoof the old TV shows that would do that, but to use them as planned transitions for a feature. Surely, they

can't be serious. That would mean the Zuckers, Abrahams and Weiss would have had to know before the episodes aired that the series would flame out in the ratings so spectacularly. Nielsen summed up fairly well why the series failed. "(Tony) Thomopolous, who was the head of ABC at that time, said the series didn't work because you had to watch it. Well, it sounds funny and it sounds dumb, but it was true. You had to pay attention. You couldn't look away," Nielsen said. "You had to watch to make sure you caught the humor or where it was coming from. People don't really watch TV…That's why you can have a laugh track. You can read a book, then look up and ask, 'Oh, what are they laughing at? Oh yeah, that's funny.' Then you go back to reading or do anything you want, but you don't really watch TV." ZAZ and Weiss said that ABC tried to get them to use a laugh track, but, by contract, the final decision on that matter rested with them. An episode actually was tested with a laugh track and without one, but the results were negligible so they got to go without one. As one of the Zuckers or Weiss or Abrahams asked, "How do you put a laugh track on a sight gag?" Remember, Drebin and Hocken had told Sally Decker that she needed to go down to the station and make a "formal statement." Several minutes passed between that direction and the payoff. Nielsen also put some of the blame on the size of TV screens at the time, which made some of the sight gags too small to catch whereas in Airplane! they were huge and hard to miss. Man cannot live on sight gags alone and that first episode contained what I think was Nielsen's greatest Frank Drebin moment as he and Hocken go interview Ralph Twice's widow (Barbara Tarbuck) in the Twices' apartment in Little Italy. Something Mrs. Twice says gets Frank a little distracted and nostalgic.

can't be serious. That would mean the Zuckers, Abrahams and Weiss would have had to know before the episodes aired that the series would flame out in the ratings so spectacularly. Nielsen summed up fairly well why the series failed. "(Tony) Thomopolous, who was the head of ABC at that time, said the series didn't work because you had to watch it. Well, it sounds funny and it sounds dumb, but it was true. You had to pay attention. You couldn't look away," Nielsen said. "You had to watch to make sure you caught the humor or where it was coming from. People don't really watch TV…That's why you can have a laugh track. You can read a book, then look up and ask, 'Oh, what are they laughing at? Oh yeah, that's funny.' Then you go back to reading or do anything you want, but you don't really watch TV." ZAZ and Weiss said that ABC tried to get them to use a laugh track, but, by contract, the final decision on that matter rested with them. An episode actually was tested with a laugh track and without one, but the results were negligible so they got to go without one. As one of the Zuckers or Weiss or Abrahams asked, "How do you put a laugh track on a sight gag?" Remember, Drebin and Hocken had told Sally Decker that she needed to go down to the station and make a "formal statement." Several minutes passed between that direction and the payoff. Nielsen also put some of the blame on the size of TV screens at the time, which made some of the sight gags too small to catch whereas in Airplane! they were huge and hard to miss. Man cannot live on sight gags alone and that first episode contained what I think was Nielsen's greatest Frank Drebin moment as he and Hocken go interview Ralph Twice's widow (Barbara Tarbuck) in the Twices' apartment in Little Italy. Something Mrs. Twice says gets Frank a little distracted and nostalgic.In "A Substantial Gift"/"The Broken Promise," we meet two of the series' priceless recurring characters. First, we meet Mr. Ted Olson (Ed

Williams), sort of a forerunner of all those forensic specialists on the various CSI shows, only crossed with Mr. Wizard and perhaps someone who belongs on a neighborhood watch list. As Peter Graves' Capt. Clarence Oveur liked to ask young Joey uncomfortable questions such as, "Have you ever seen a grown man naked?" in Airplane!, each week when Frank goes to Olson's lab, he's always visiting with a child (of either sex) trying to explain different scientific things that inevitably draw comparisons to their mothers getting out of showers or something along those lines. Each week, he leaves them with a hysterically odd line. For those six brief weeks, we hear Olson make these promises or requests to various kids:

Williams), sort of a forerunner of all those forensic specialists on the various CSI shows, only crossed with Mr. Wizard and perhaps someone who belongs on a neighborhood watch list. As Peter Graves' Capt. Clarence Oveur liked to ask young Joey uncomfortable questions such as, "Have you ever seen a grown man naked?" in Airplane!, each week when Frank goes to Olson's lab, he's always visiting with a child (of either sex) trying to explain different scientific things that inevitably draw comparisons to their mothers getting out of showers or something along those lines. Each week, he leaves them with a hysterically odd line. For those six brief weeks, we hear Olson make these promises or requests to various kids:

What might be the biggest gag concerning Williams' great performance as Ted Olson is that it was his first acting role. Prior to auditioning for Police Squad! and winning the part, Williams had retired from a career actually teaching science. He's acted steadily in small roles ever since. Every visit to his lab, even in the lesser of the six episodes, usually proved worth it. In the perfection of the premiere, Olson discovers problems with Sally's story because of the depth and trajectory the bullets would have had to take to make her story true. He demonstrates this for Frank with a state-of-the-art ballistics test where he fires each weapon into videotapes of Barbara Walters interviews. His first firing goes all the way to her interview with Paul Newman where Walters "asks him if he's afraid to love." The bullet from the second gun goes through the entire row of tapes clear through "where she asks Katharine Hepburn what kind of tree she would be." For a first-time actor, one thing that sets Ed Williams apart is that when Police Squad! had its resurrection in the form of The Naked Gun movies, he was the only actor other than Nielsen to reprise his role. The Zuckers, Abraham and Weiss regret on the commentary not being able to bring Alan North back as Hocken, calling him "very good." The studio insisted on a better-known actor so George Kennedy got the role in the films and as (I think it was David Zucker) said, "We folded like a cheap suit."

Another recurring joke that Police Squad! spoofed from the Quinn Martin shows were mid-episode title cards that marked the start of an episode's second act. With that in mind, I will end the first half of the tribute here with my favorite second act joke. You can click here to go to Part II to read about the other recurring characters, the remainder of "A Substantial Gift/The Broken Promise," some of the best bits of the other episodes, other background tidbits and the lasting influence of Police Squad!

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Abbott and Costello, D. Zucker, G. Kennedy, J. Zucker, Jim Abrahams, K. Hepburn, Marvin, Marx Brothers, Newman, Nielsen, Nimoy, Shatner, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, February 22, 2012

He didn't need dialogue! He had his face!

By Edward Copeland

Writing a review of The Artist has proved unusually difficult for me. I watched the film for the first time a couple of weeks ago and found it charming enough but — and perhaps it's appropriate — I was at a loss for words. Not because the movie bowled me over so much that I was awestruck, I just felt that either I was missing something or the film was. I decided to watch The Artist a second time to try and determine what gnawed at me.

On the off chance you haven't heard about The Artist, I'll give you a brief synopsis of its plot. After all, the movie will be crowned the newest Academy Award-winning best picture Sunday night, you should probably know. There isn't much of a plot so it won't take long. In 1927, one of the biggest stars of the silent film era is George Valentin (Oscar nominee Jean Dujardin). Outside the premiere of his latest film, an eager fan named Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo, also nominated) stumbles into a paparazzi shot with Valentin and, later, as an extra on one of his films. From there, the story unfolds along the lines of A Star Is Born. Only in The Artist, George Valentin's career doesn't plummet because of alcohol but by sound coming to motion pictures. Peppy soars at the same time.

The Artist alludes to so many different films, I'm sure I missed some. What fascinated me about the choices was that the overwhelming number of references writer-director Michel Hazanavicius makes come from the sound era. For a throwback to the days of black-and-white silent films, very few pay tribute to classics of that era. (The closest — and it's a reach — is the opening scene of a film within the film showing Valentin strapped down with electrodes sending shocks to his head that vaguely recall Metropolis. Of course, he's not a robot and it gives the movie funny lines to open with as he tells his interrogators that he won't speak.) Contrast that with Martin Scorsese's nostalgic look back at silent film in his three-dimensional, color, sound production of Hugo which overflows with sets and sequences that include shout-outs to famous silent films such as Modern Times and Safety Last.

In The Artist, the breakfast table scenes between George and his wife, Doris (a nearly unrecognizable Penelope Ann Miller), obviously aims to evoke the famous scene in Citizen Kane. They revisit Kane later when George discovers that all of his personal treasures that the collapse of his career and the economy force him to auction have been stored in a room in Peppy's mansion beneath sheets. His find leads to the use of Bernard Herrmann's Vertigo score that gave Kim Novak a conniption fit. While I don't share the actress's over-the-top objections to its use, I do have to ask what message the audience should take from its presence. First, assuming that your average moviegoer recognizes that the music that begins playing comes from Hitchcock's classic (and that's a big if), by George's frantic fleeing, is the implication that Valentin fears that Peppy wants to shape him into his own image as Scottie Ferguson wished to turn Judy into Madeleine? Perhaps given their history of encounters he suspect she's a stalker.

You also can be pretty certain going into a silent film made in 2011 about the downward spiral of a silent film star that you aren't getting out of the theater without some Sunset Blvd. references. Valentin makes for the obvious Norma surrogate in this scenario. When the studio boss (John Goodman) tells him that he better not laugh at sound because it's the future, Valentin says (or, more accurately, a title card reads), "If that's the future, you can have it." Valentin even goes so far as to decide to make his own silent movie, though in 1929 he's typing out his screenplay instead of scribbling out a script of Salome as Norma Desmond was still doing by the time 1950 showed up. The big difference between Valentin and Norma though is that Valentin isn't bonkers and perhaps neither was Norma that soon after talkies took over. The crucial part of Sunset Blvd. concerns the screenwriter Joe Gillis seeking refuge in Norma's garage and meeting her, thinking he can scam her before he basically becomes a prisoner in her mansion. In The Artist, after being saved from a fire by the quick-thinking of his pooch Uggie (don't ask), George ends up hospitalized and Peppy takes him back to her mansion in a way, making her the Norma. This precedes the discovery of his auctioned memorabilia and the borrowing of Herrmann's Vertigo score. Even though earlier, Valentin's former chauffeur/butler Clifton (James Cromwell), who kept working for George for a year without pay but now works for Peppy swears to his former boss that Peppy "has a good heart." The Artist fires mixed signals all over the place.

Surprisingly, The Artist tends to steer clear of any direct references to the classic Singin' in the Rain, my choice and the choice of many others for Hollywood's greatest movie musical, that also covered film's transition to sound. Obviously, since The Artist eschews sound, except for a couple of appropriate moments, it can't very well be a musical or make a joke about a silent star having a horrible voice that won't work in talkies. More importantly, I don't think The Artist dared to go there because comparing it to Singin' in the Rain would be too dangerous. It can toss out references to great movies such as Citizen Kane, Vertigo and Sunset Blvd. because as a whole The Artist bears little resemblance to those films. Singin' in the Rain holds a mirror up to the essential emptiness inside The Artist.

This isn't to say that The Artist is a bad film, not by any means. It's affable, well directed and entertaining. It has many nice and funny moments. (One that probably only amused someone like me is the first time Peppy gets a screen credit, they misspell her first name as Pepi. It still amazes me how many times that happens. Frank Capra's 1948 film State of the Union was on recently and spelled Katharine Hepburn's above-the-title name as Katherine. No one has bothered to correct this in more than 60 years?) Guillaume Schiffman's black-and-white cinematography shimmers but I have to say that the original portions of Ludovic Bource's score can be overbearing. If they really wanted to do a silent movie now, why not have a score that sounds like what a moviegoer might have heard in a theater in 1927? Something simple, on a pipe organ, not a fully orchestrated blow-out-your-eardrums composition.

Jean Dujardin makes the film. You could believe he came from the silent era, yet when he's playing the offscreen Valentin you see the difference. Bérénice Bejo isn't the same story. There isn't much subtlety in anything she does.

I finally put my finger on what gnawed at me about The Artist. It's like the old joke about eating Chinese food. It's fulfilling enough while you're consuming it, but a few hours later you're hungry again.

Tweet

Labels: 10s, Capra, Herrmann, Hitchcock, John Goodman, K. Hepburn, Scorsese, Silents

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, December 23, 2011

“I never dreamed that any mere physical experience could be so stimulating!”

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

One of my fondest memories of collegiate life was a weekend in 1982 in which the activities department at Marshall University put together a film tribute to actor Humphrey Bogart as part of their weekly showing of classic and cult movies. I can’t recollect the exact scheduling (the MU people would showcase a feature on Friday afternoons/evenings and then have a matinee on Sundays) but I do recall that Key Largo, The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca made up the lineup and this little event exposed me to three of Bogie’s major classics for the first time. The last film, which I have forcefully stated many times at my home base of Thrilling Days of Yesteryear, is my favorite movie of all time. I still can remember the audience cheering wildly at Claude Rains’ discovery that Bogart, as Rick Blaine, has double-crossed him (“Not so fast, Louie…”) and will be helping Ingrid Bergman and Paul Henreid out on the next plane to Lisbon.

That weekend wasn’t my introduction to one of my favorite actors, however. Years earlier, through the magic of television, I saw the film that earned Bogie his best actor Oscar, The African Queen (1951), because my mother was a huge fan of the film and it soon became one of my favorites, one of those movies which gets watched to the very end if I should happen to see it playing on, say, Turner Classic Movies. Fortunately for classic movie fans, you don’t have to wait for its TCM scheduling — Queen made its Region 1 DVD debut (it had only been previously available in Region 2 releases) on March 23, 2010 (simultaneously with its Blu-ray debut) in a breathtakingly gorgeous restoration from Paramount Home Video. In fact, it was explained that its long absence from DVD was due to the difficulty in locating the film’s original negative. Queen, based on the 1935 novel by C.S. Forester, made the rounds of motion picture theaters 60 years ago today.

It is September 1914, and Anglican missionaries Samuel (Robert Morley) and Rose Sayer (Katharine Hepburn) spread the gospel to natives in the German Eastern African village of Kungdu when they receive a visit from Charlie Allnut (Bogart), skipper of the African Queen. Allnut is responsible for bringing their mail and supplies, and during his stopover informs the Sayers that since war has broken out between England and Germany, their mail delivery will be affected; he also advises the two of them to abandon their post because of his concern that the German army will recruit Kungdu’s able-bodied young men to fight for their cause. Samuel staunchly refuses, but only seconds after Charlie departs he and Rose are visited by German soldiers, who respond to Samuel’s protests with the business end of a rifle butt as his fellow conscripts start rounding up the natives and setting the village ablaze. With Kungdu in ruins, Samuel soon comes down with fever and dies — Charlie returns to the village in time to help Rose bury her brother and then agrees to spirit her away on his boat.

Despite the vessel being well-stocked with provisions, Charlie and Rose’s escape from their circumstances will not be an easy task; the Ulanga River presents obstacles in the three sets of rapids and a German stronghold in the form of a fort in the town of Shona. Because the ship’s supplies also include blasting materials (gelignite) and oxygen/hydrogen tanks, Rose, filled with both stiff-upper-lip patriotism and bitterness over her brother's death, proposes that the two of them fashion makeshift torpedoes out of the materials and use them to take on the Queen Louisa (or as the Germans refer to it, the Königin Luise), a large gunboat guarding the lake in which the Ulanga empties. Charlie is convinced that what Rose is suggesting will be a suicide mission, but he agrees to the plan only to get cold feet shortly after navigating the first set of rapids. He declares his intentions to have nothing to do with Rose’s plan after a gin-sponsored bender. The next morning, suffering from a hangover, Charlie watches helplessly as Rose pours every last drop of his precious gin into the Ulanga and follows this up with “the silent treatment,” Charlie reconsiders the mission.

German soldiers fire upon Charlie and Rose as they pass the fort at Shona, and though the two of them avoid being hit by gunfire, the men do manage to hit the African Queen’s boiler, disconnecting one of its steam pressure hoses and bringing the vessel to a temporary halt. (Charlie manages to reconnect the hose and they pass by the fort unscathed.) The boat then hits the second set of rapids and survives the ordeal with minimal damage, prompting the duo to engage in a celebratory embrace which leads to a kiss. It is by this time in their adventure that they cannot deny the strong attraction that has developed between them, which leads to an amusing scene in which Rose asks her new boyfriend awkwardly: “Dear, what is your first name?”

The couple finally navigates the final set of rapids, but in doing so sustain damage to the Queen’s shaft and propeller. Rose convinces Charlie that he has the skills to repair the boat and, using what is available on a nearby island, he restores the Queen to working order and they’re off again down the river. However, they soon discover the deception of the Ulanga River; they “lose the channel” and become stranded on a mud bank surrounded by reeds in all directions — with Charlie sidelined with fever (after an experience in which he emerges from the murky water covered with leeches). When all appears lost, Rose offers up a prayer asking that she and Charlie be granted entrance into the Kingdom of Heaven…and in answer to that prayer, rains from a monsoon soon lift the boat out of the mud and into the mouth of the lake — as it turns out, they were less than a hundred yards from their destination.

Charlie and Rose, having spotted the Louisa patrolling the lake, prepare the makeshift torpedoes and go after the German craft come nightfall, but en route they get trapped in a squall and the African Queen capsizes due to the holes made in its sides to accompany the torpedoes. The Louisa’s crew captures Charlie who is crestfallen because he thinks Rose has drowned, so much so that he stoically accepts the captain’s decision to hang him. Surprisingly, Rose has survived the Queen’s sinking and is brought aboard to face questioning where she proudly tells the Louisa’s captain of their plot to scuttle the ship, resulting in her sentence of execution as well. Before the couple's hanging, Charlie asks the Louisa’s captain if he’ll marry him and Rose; that buys enough time for the Louisa to run into the Queen’s wreckage, detonating the torpedoes and sinking the ship. The newly married Allnuts swim to safety toward the Belgian Congo as the film concludes.

Upon its publication in 1935, The African Queen originally was optioned for a film adaptation by several studios including RKO and Warner Bros. — Charles Laughton and Elsa Lanchester even made a movie (with a similar story, though the source material came from W.

Somerset Maugham) in 1938 entitled Vessel of Wrath (aka The Beachcomber). Over the years, several actors were suggested for the part of Charlie Allnut; John Mills, David Niven and James Mason being the most prominent — Bette Davis was the only actress in serious contention for Rose, but after an abortive attempt to do the movie in 1947 (scuttled because of Davis’ pregnancy) she was passed over two years later in favor of Katharine Hepburn when the production got underway. (Director John Huston, who had already chosen Humphrey Bogart for his Charlie, once stated in an interview that Hepburn was tabbed because Bogart had expressed an interest in working with her.) While it’s possible to see Davis playing the part, the choice of Hepburn (in what would be her first color film) was the right one despite some initial reservations on the part of Huston with Kate’s performance. Thinking she was making the Rose character a little too severe, John suggested that Hepburn imitate the indomitable spirit of former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who always remained cheerful despite any adversity. (Hepburn later observed that Huston’s suggestion was the finest bit of directing she’d ever received.)

Somerset Maugham) in 1938 entitled Vessel of Wrath (aka The Beachcomber). Over the years, several actors were suggested for the part of Charlie Allnut; John Mills, David Niven and James Mason being the most prominent — Bette Davis was the only actress in serious contention for Rose, but after an abortive attempt to do the movie in 1947 (scuttled because of Davis’ pregnancy) she was passed over two years later in favor of Katharine Hepburn when the production got underway. (Director John Huston, who had already chosen Humphrey Bogart for his Charlie, once stated in an interview that Hepburn was tabbed because Bogart had expressed an interest in working with her.) While it’s possible to see Davis playing the part, the choice of Hepburn (in what would be her first color film) was the right one despite some initial reservations on the part of Huston with Kate’s performance. Thinking she was making the Rose character a little too severe, John suggested that Hepburn imitate the indomitable spirit of former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who always remained cheerful despite any adversity. (Hepburn later observed that Huston’s suggestion was the finest bit of directing she’d ever received.)Hepburn’s performance in the film is a marvel because the actress bravely allowed herself to be filmed au natural, which no doubt stunned audiences at the time as they saw the great Kate playing her true middle-age (something that she would go on to do from that point in

her career, particularly in David Lean's wonderful 1955 film Summertime) and yet they witnessed a woman who transforms from a “crazy, psalm-singing, skinny old maid” into a spunky, sexy woman whose romance with the unlikely Charlie makes her giddy as a schoolgirl (I love the scene where she giggles and laughs uncontrollably at Charlie’s animal noises on the boat). The relationship between the characters is so genuine and feels so right, you literally watch the barriers between the two melt away during the course of their adventure. Pay particularly close attention when Rose helps Charlie pump water out of the boat and she stops momentarily, caught up in her romantic reverie. Charlie has got it bad as well. In assisting Rose with the task,c you can just see how dazed and delighted he is to have found true love. Director John Huston could scarcely ignore the magic between the two characters and decided to buck the tradition of most of his films (which tend to feature what one critic has called “beautiful losers”) by allowing Charlie and Rose’s torpedo scheme to succeed (in Forester’s book the plan doesn’t quite come off) and joining the two in holy matrimony (a plot device also designed to ward off criticism by bluenoses finger-wagging at Charlie and Rose’s cohabitation outside marriage).

her career, particularly in David Lean's wonderful 1955 film Summertime) and yet they witnessed a woman who transforms from a “crazy, psalm-singing, skinny old maid” into a spunky, sexy woman whose romance with the unlikely Charlie makes her giddy as a schoolgirl (I love the scene where she giggles and laughs uncontrollably at Charlie’s animal noises on the boat). The relationship between the characters is so genuine and feels so right, you literally watch the barriers between the two melt away during the course of their adventure. Pay particularly close attention when Rose helps Charlie pump water out of the boat and she stops momentarily, caught up in her romantic reverie. Charlie has got it bad as well. In assisting Rose with the task,c you can just see how dazed and delighted he is to have found true love. Director John Huston could scarcely ignore the magic between the two characters and decided to buck the tradition of most of his films (which tend to feature what one critic has called “beautiful losers”) by allowing Charlie and Rose’s torpedo scheme to succeed (in Forester’s book the plan doesn’t quite come off) and joining the two in holy matrimony (a plot device also designed to ward off criticism by bluenoses finger-wagging at Charlie and Rose’s cohabitation outside marriage).

Huston and Bogart were not only close friends in real life, they had made onscreen magic working together as far back as the director’s feature film debut, The Maltese Falcon, and as recently as one of Huston’s masterpieces, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. To accommodate the handicap of Bogart’s inability to do a Cockney accent, however, the character of Charlie Allnut became a Canadian, prompting a hefty rewrite of the script. Though the role of Charlie would seem a departure for Bogie, known for his tough-guy antiheroes, there are many shared characteristics between him and other Bogart characters (Allnut shares the same unshaven scruffiness as Sierra Madre’s Fred C. Dobbs, for example), particularly that of the individual who eventually comes around in support of the cause for the greater good. Bogart was nominated for a best actor Oscar for his performance (Hepburn also was tabbed, along with Huston for his direction and screenplay with co-writer James Agee) and despite stiff competition that year from Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift and Fredric March, the Academy got sentimental and awarded the actor the coveted trophy.

The realistic atmosphere and look of the film stem from the decision by Huston and producer Sam Spiegel (along with brothers John and James Woolf, who financed the movie through their Romulus Films company) to shoot on location in Uganda and the Congo in Africa.

Under normal circumstances, this production would have been daunting but because it was a Technicolor film (which necessitated large, unwieldy cameras), the shoot proved to be an ordeal for all involved. Hepburn later detailed the colorful history of the production in a book, The Making of the African Queen, or: How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind, and a fascinating featurette included on the Paramount Home Video DVD, Embracing Chaos: Making the African Queen, also contains enthralling anecdotes about this remarkable motion picture. The cast and crew survived any number of adverse conditions, chiefly among them sickness due to the dysentery resulting from contaminated drinking water. Hepburn, for example, became so ill that a bucket was placed near the pipe organ she plays in the opening church scenes. According to cinematographer Jack Cardiff, the actress was “a real trouper.” The only two individuals on the film who escaped illness, according to legend, were Huston and Bogart, primarily because the men subsisted on the imported Scotch they had brought with them. (Bogie later cracked: “All I ate was baked beans, canned asparagus and Scotch whiskey. Whenever a fly bit Huston or me, it dropped dead.”)

Under normal circumstances, this production would have been daunting but because it was a Technicolor film (which necessitated large, unwieldy cameras), the shoot proved to be an ordeal for all involved. Hepburn later detailed the colorful history of the production in a book, The Making of the African Queen, or: How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind, and a fascinating featurette included on the Paramount Home Video DVD, Embracing Chaos: Making the African Queen, also contains enthralling anecdotes about this remarkable motion picture. The cast and crew survived any number of adverse conditions, chiefly among them sickness due to the dysentery resulting from contaminated drinking water. Hepburn, for example, became so ill that a bucket was placed near the pipe organ she plays in the opening church scenes. According to cinematographer Jack Cardiff, the actress was “a real trouper.” The only two individuals on the film who escaped illness, according to legend, were Huston and Bogart, primarily because the men subsisted on the imported Scotch they had brought with them. (Bogie later cracked: “All I ate was baked beans, canned asparagus and Scotch whiskey. Whenever a fly bit Huston or me, it dropped dead.”)The size of the African Queen also presented problems where the Technicolor cameras were concerned — because there was not enough room for the cameras on the boat (which measured 16 feet long and 5 feet wide), a mock-up of the craft was put together on a larger raft and the production used several such rafts to the point where the river hosted a small flotilla, with the last pontoon housing Hepburn’s “loo” (her contract stipulated that she be provided with private restroom facilities). The waters of the river, considered poisonous due to bacteria, animal excrement, etc., were never utilized in shots or sequences requiring Bogie and Kate’s immersal — they were filmed separately in studio tanks at the Isleworth Studios in London. Despite the challenges presented in the making of the film, what resulted was a certified masterpiece — at a time when “independent” films are the Hollywood darlings of today, The African Queen was a noteworthy example of that particular type of movie (made outside the dictates of the studio system) even though industry wags remained skeptical about its performance at the box office. (The film was a tremendous success, but director Huston never collected on the payday because of his desire to sever his ties with producer Spiegel; cinematographer Cardiff also had the option of taking a percentage of the profits to subsidize a lower salary but he begged off, having had a bad experience with another film he had worked on in that same year, The Magic Box.)