Thursday, October 10, 2013

Better Off Ted: Bye Bye 'Bad' Part III

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now. If you missed Part I, click here. If you missed Part II, click here.

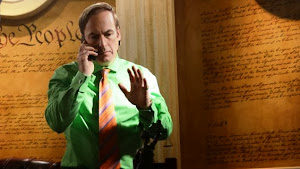

— Saul Goodman to Mike Ehrmantraut ("Buyout," written by Gennifer Hutchison, directed by Colin Bucksey)

By Edward Copeland

Playing to the back of the room: I love doing it as a writer and appreciate it even more as an audience member. While I understand how its origin in comedy clubs gives it a derogatory meaning, I say phooey in general. Another example of playing to the broadest, widest audience possible. Why not reward those knowledgeable ones who pay close attention? Why cater to the Michele Bachmanns of the world who believe that ignorance is bliss? What they don’t catch can’t hurt them. I know I’ve fought with many an editor about references that they didn’t get or feared would fly over most readers’ heads (and I’ve known other writers who suffered the same problems, including one told by an editor decades younger that she needed to explain further whom she meant when she mentioned Tracy and Hepburn in a review. Being a free-lancer with a real full-time job, she quit on the spot). Breaking Bad certainly didn’t invent the concept, but damn the show did it well — sneaking some past me the first time or two, those clever bastards, not only within dialogue, but visually as well. In that spirit, I don’t plan to explain all the little gems I'll discuss. Consider them chocolate treats for those in the know. Sam, release the falcon!

In a separate discussion on Facebook, I agreed with a friend at taking offense when referring to Breaking Bad as a crime show. In fact, I responded:

“I think Breaking Bad is the greatest dramatic series TV has yet produced, but I agree. Calling it a ‘crime show’ is an example of trying to pin every show or movie into a particular genre hole when, especially in the case of Breaking Bad, it has so many more layers than merely crime. In fact, I don't like the fact that I just referred to it as a drama series because, as disturbing, tragic and horrifying as Breaking Bad could be, it also could be hysterically funny. That humor also came in shapes and sizes across the spectrum of humor. Vince Gilligan's creation amazes me in a new way every time I think about it. I wonder how long I'll still find myself discovering new nuances or aspects to it. I imagine it's going to be like Airplane! — where I still found myself discovering gags I hadn't caught years and countless viewings after my initial one as an 11-year-old in 1980. Truth be told, I can't guarantee I have caught all that ZAZ placed in Airplane! yet even now. Can it be a mere coincidence that both Breaking Bad and Airplane! featured Jonathan Banks? Surely I can't be serious, but if I am, tread lightly.”

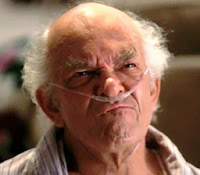

— Jonathan Banks as air traffic controller Gunderson in Airplane!

The second season episode “ABQ” (written by Vince Gilligan, directed by Adam Bernstein) introduced us to Banks as Mike and also featured John de Lancie as air traffic controller Donald Margulies, father of the doomed Jane. Listen to the DVD commentary about a previous time that Banks and De Lancie worked together. Speaking of air traffic controllers, if you don’t already know, look up how a real man named Walter White figured in an airline disaster. Remember Wayfarer 515! Saul never did, wearing that ribbon nearly constantly. Most realize the surreal pre-credit scenes that season foretold that ending cataclysm and where six of its second season episode titles, when placed together in the correct order, spell out the news of the disaster. Breaking Bad’s knack for its equivalent of DVD Easter eggs extended to episode titles, which most viewers never knew unless they looked them up. Speaking of Saul Goodman, he provided the voice for a multitude of Breaking Bad’s pop culture references from the moment the show introduced his character in season two’s “Better Call Saul” (written by Peter Gould, directed by Terry McDonough). Once he figures out (and it doesn’t take long) that Walt isn’t really Jesse’s uncle and pays him a visit in his high school classroom, the attorney and his client discuss a more specific role

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key

for the lawyer, with Saul referencing a particularly classic film without mentioning the title. “What are you offering me?” Walt asked, unclear as to Goodman’s suggestion for an expanded role. “What did Tom Hagen do for Vito Corleone?” the criminal attorney responds. “I'm no Vito Corleone,” an offended and shocked White replies. “No shit! Right now you're Fredo!” Saul informs Walt. Now, Walt easily knew what movie Saul summoned as an analogy there and I hope any reader easily can as well. It happens to be the same one referenced visually at the top of this piece when poor Ted Beneke took his fateful trip in season four’s classic “Crawl Space” (written by George Mastras & Sam Catlin, directed by Scott Winant). Gilligan from the beginning repeatedly told of how his original pitch for Breaking Bad was the idea of turning Mr. Chips into Scarface and he referred to Brian De Palma’s version of Scarface often, actually showing Walt and Walt Jr. watching the film together in the final season with the elder White commenting, “Everyone dies in this, don’t they?” — possible foreshadowing for how Breaking Bad would end, though it didn't play out that way. The show achieved homage more openly in casting key players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.

players from the 1983 film itself: Mark Margolis as Tio Hector Escalante and Steven Bauer as Mexican cartel chief Don Eladio. Of course, the entire series implies the reiterated refrain of De Palma’s film “Don’t get high on your own supply” because, while Walter White never used his blue meth literally, it certainly juiced him up and, as he told Skyler in the last episode “Felina” (written and directed by Gilligan), it made him feel alive. Unfortunately, I doubt any surviving cast members of 1939’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips remain with us so Breaking Bad might have cast them in appropriate roles, but many of the 1969 musical version still abound and what a kick it have been to see Peter O’Toole or Petula Clark appear as a character. Apparently, in 2002, a nonmusical British TV remake came about, but they needn’t have dipped that far in the referential well. Blasted remakes. As far as Scarface goes, I still prefer Howard Hawks’ original over De Palma’s anyway.As I admitted, some of the nice touches escaped my notice until pointed out to me later. Two of the most obvious examples occurred in the final eight episodes. One wasn’t so much a reference as a callback to the very first episode that you’d need a sharp eye to spot. It occurs in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson) and I’d probably never noticed if not for a synched-up commentary track that Johnson did for the episode on The Ones Who Knock weekly podcast on Breaking Bad. He pointed out that as Walt rolls his barrel of $11 million through the desert (itself drawing echoes to Erich von Stroheim’s silent classic Greed and its lead character McTeague — that one I had caught) he passes the pair of pants he lost in the very first episode when they flew through the air as he frantically drove the RV with the presumed dead Krazy-8 and Emilio unconscious in the back. Check the still below, enlarged enough so you don’t miss the long lost trousers.

The other came when psycho Todd decided to give his meth cook prisoner Jesse ice cream as a reward. I wasn’t listening closely enough when he named one of the flavor choices as Ben & Jerry’s Americone Dream, and even if I’d heard the flavor’s name, I would have missed the joke until Stephen Colbert, whose name serves as a possessive prefix for the treat’s flavor, did an entire routine on The Colbert Report about the use of the ice cream named for him giving Jesse the strength to make an escape attempt. One hidden treasure I did not know concerned the appearance of the great Robert Forster as the fabled vacuum salesman who helped give people new identities for a price. Until I read it in a column on the episode “Granite State” (written and directed by Gould), I had no idea that in real life Forster once actually worked as a vacuum salesman.

Seeing so many episodes multiple times, the callbacks to previous moments in the series always impressed me. I didn’t recall until AMC held its marathon prior to the finale and I caught the scene where Skyler caught Ted about him cooking his company’s books in season two’s “Mandala” (written by Mastras, directed by Adam Bernstein),

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.

Beneke actually raises his hands and says, “You got me” — words and movements that return in season four’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) when Hank tells Walt about the late Gale Boetticher and speculates jokingly about whether the W.W. in Gale’s notebook stands for Walter White. In the same episode, Hank discusses his disappointment (since he assumes Gale was Heisenberg) that he never got his Popeye Doyle moment from The French Connection and waved goodbye to Alain Charnier. Walt reminds Hank that Charnier escaped at the end of the movie, but in “Ozymandias,” Hank imitates Gene Hackman's wave anyway when he gets the cuffs on Walt and places him in the SUV. Film references and homages abound throughout the series. I don’t recall any to Oliver Stone off the top of my head (except, of course, that he wrote De Palma's Scarface) and I hope there weren’t given that filmmaker’s recent hypocritical and nonsensical whining about Breaking Bad’s ending where he called it “ridiculous” among other sleights. If that’s not a fool declaring a nugget of gold to be pyrite. (“IT’S A MINERAL, OLIVER!”) I'd also like to commend the nearly subliminal shout-outs to two great HBO series that received premature endings in the episode "Rabid Dog" (written and directed by Catlin). You can see the Deadwood DVD box set on Hank's bookshelf and, though the carpet cleaning company's name might be Xtreme, the way they design their logo on their van sure makes the words Treme stand out to me.I wanted this tribute to be so much grander and better organized, but my physical condition thwarted my ambitions. I doubt seriously my hands shall allow me to complete a fourth installment. (If you did miss Part I or Part II, follow those links.) While I hate ending on a patter list akin to a certain Billy Joel song, (I let you off easy. I almost referenced Jonathan Larson — and I considered narrowing the circle tighter by namedropping Gerome Ragni

& James Rado.) I feel I must to sing my hosannas to the actors, writers, directors and other artists who collaborated to realize the greatest hour-long series in

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray

television history. I wish I had the energy to be more specific about the contributions of these names in detail. In no particular order and with apologies for any omissions: Vince Gilligan, Michelle McLaren, Adam Bernstein, Colin Bucksey, Michael Slovis, Bryan Cranston, Terry McDonough, Johan Renck, Rian Johnson, Scott Winant, Peter Gould, Tricia Brock, Tim Hunter, Jim McKay, Phil Abraham, John Dahl, Félix Enríquez Alcalá, Charles Haid, Peter Medak, John Shiban, David Slade, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Sam Catlin, Moira Walley-Beckett, Gennifer Hutchison, J. Roberts, Patty Lin, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, Dean Norris, RJ Mitte, Bob Odenkirk, Steven Michael Quezada, Jonathan Banks, Giancarlo Esposito, (because I have to put them as a unit) Charles Baker and Matt Jones, Jesse Plemons, Christopher Cousins, Laura Fraser, Michael Shamus Wiles, (also need to be a unit) Lavell Crawford and Bill Burr, Ray Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

Campbell, Krysten Ritter, Ian Posada as the most shit-upon child in television history, Emily Rios, Tina Parker, Mark Margolis, Jeremiah Bitsui, David Costabile, Michael Bowen, Kevin Rankin, (another pair) Daniel and Luis Moncado, Jessica Hecht, Marius Stan, Rodney Rush, Raymond Cruz, Tess Harper, John de Lancie, Jere Burns, Nigel Gibbs, Larry Hankin, Max Arciniega, Michael Bofshever, Adam Godley, Julia Minesci, Danny Trejo, Dale Dickey, David Ury, Jim Beaver, Steven Bauer, DJ Qualls, Robert Forster, Melissa Bernstein, Mark Johnson, Stewart Lyons, Diane Mercer, Andrew Ortner, Karen Moore, Dave Porter, Reynaldo Villalobos, Peter Reniers, Nelson Cragg, Arthur Albert, John Toll, Marshall Adams, Kelley Dixon, Skip MacDonald, Lynne Willingham, Sharon Bialy, Sherry Thomas, Mark S. Freeborn, Robb Wilson King, Bjarne Sletteland, Marisa Frantz, Billy W. Ray, Paula Dal Santo, Michael Flowers, Brenda Meyers-Ballard, Kathleen Detoro, Jennifer L. Bryan, Thomas Golubic, Albuquerque, N.M., AMC Networks, University of Oklahoma Professor Donna Nelson and a list of crew members and departments I’d mention but, unfortunately, my hands aren’t holding out. Look them up because they all deserve kudos as well because Breaking Bad failed to have a weak link, at least from my perspective.

In fact, the series failed me only twice. No. 1: How can you dump the idea that Gus Fring had a particularly mysterious identity in the episode “Hermanos” and never get back to it? No. 2: That great-looking barrel-shaped box set of the entire series only will be made on Blu-ray. As someone of limited means, it would need to be a Christmas gift anyway and for the same reason, I never made the move to Blu-ray and remain with DVD. Medical bills will do that to you and, even if tempting or plausible, it’s difficult to start a meth business to fund it while bedridden. Despite those two disappointments, it doesn’t change Breaking Bad’s place in my heart as the best TV achievement so far. How do I know this? Because I say so.

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Cranston, D. Zucker, De Palma, Deadwood, Hackman, Hawks, HBO, J. Zucker, Jim Abrahams, K. Hepburn, O'Toole, Oliver Stone, Tracy, Treme, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, May 19, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part II

By Edward Copeland

We pick up our tribute to Richard Brooks in 1956. If you missed Part I, click here. Of Brooks' two 1956 releases, I've only seen one of them. The Last Hunt stars Stewart Granger as a rancher who loses all his cattle to a stampeding herd of buffalo. Robert Taylor plays a buffalo hunter who asks him to join in an expedition to slaughter the animals, but the rancher, an ex-buffalo hunter himself, had quit because he'd grown weary of the killing. Brooks may be the auteur of antiviolence. Filmed in Technicolor Cinemascope, I imagine it looked great on the big screen. Bosley Crowther wrote in his New York Times review, "Even so, the killing of the great bulls—the cold-blooded shooting down of them as they stand in all their majesty and grandeur around a water hole—is startling and slightly nauseating. When the bullets crash into their heads and they plunge to the ground in grotesque heaps it is not very pleasant to observe. Of course, that is as it was intended, for The Last Hunt is aimed to display the low and demoralizing influence of a lust for slaughter upon the nature of man." The second 1956 film I did see and given the talents involved and the paths it would take, it's a fairly odd tale. The Catered Affair was the third and last film in Richard Brooks' entire directing career that he also didn't write or co-write.

It began life as a teleplay by the great Paddy Chayefsky in 1955 called A Catered Affair starring Thelma Ritter, J. Pat O'Malley and Pat Henning before its adaptation for the big screen the following year, the same journey Chayefsky's Marty took that ended up in Oscar glory. This time, Chayefsky didn't adapt his work for the movies — Gore Vidal did. Articles of speech changed in its title as well as the teleplay A Catered Affair became The Catered Affair for Brooks' film. (Chayefsky apparently wasn't a particular fan of this work of his — it never was published or appeared in a collection of his scripts.) We're at the point where the project just got screwy. The simple story concerns an overbearing Irish mom in the Bronx determined to give her daughter a ritzy wedding because of the bragging she hears her future in-laws go on about describing the nuptials thrown for their girls. Despite the fact that the Hurley family lacks the funds for it, Mrs. Hurley stays determined while her husband Tom sighs — he's been saving to buy his own cab. On TV, the casting of Ritter and O'Malley for certain sounded appropriate. For the film, which added characters since it had to expand the length, the cast appeared to have been picked out of a hat because they certainly didn't seem related, most didn't register as Irish and as for being from the Bronx — fuhgeddaboudit. Meet Mr. and Mrs. Tom Hurley, better known to you as Ernest Borgnine and

Bette Davis. Unlikely match though they be, somehow their genes combined and out popped the most Bronx-like of Irish girls — Debbie Reynolds. The new character of Uncle Jack does add a bit of real Irish flavor by tossing in Barry Fitzgerald for no apparent reason. Unbelievably, it made the list of the top 10 films of the year from the National Board of Review who also named Reynolds best supporting actress (nothing against Reynolds in general — just miscast here). You would think that this Affair would fade into oblivion, but you'd be wrong. In 2008, it changed articles again and re-emerged on the Broadway stage as the musical A Catered Affair. Faith

Bette Davis. Unlikely match though they be, somehow their genes combined and out popped the most Bronx-like of Irish girls — Debbie Reynolds. The new character of Uncle Jack does add a bit of real Irish flavor by tossing in Barry Fitzgerald for no apparent reason. Unbelievably, it made the list of the top 10 films of the year from the National Board of Review who also named Reynolds best supporting actress (nothing against Reynolds in general — just miscast here). You would think that this Affair would fade into oblivion, but you'd be wrong. In 2008, it changed articles again and re-emerged on the Broadway stage as the musical A Catered Affair. Faith Prince and Tom Wopat(Yes — that Tom Wopat of Luke Duke fame) earned Tony nominations as the parents, Harvey Fierstein wrote the book and played the uncle (named Winston) and John Bucchino wrote the score. Why did Brooks make this one? Easy. He was under contract. MGM told him to make it, so he had no choice. From Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks, some of the cast talked on record about how Brooks could be a bit of a prick as a director. "I didn't know it at the time, but Brooks ate and digested actors for breakfast," Borgnine said later. "If things weren't working, he let you know it, and not gently." When a particular scene was not working to his satisfaction, (Brooks) ordered Borgnine and Davis to figure out the problem. Borgnine suggested a different pacing and Davis agreed the scene was better for it — as did (Brooks), though he offered Borgnine not praise but a putdown. 'Goddamn thinking actor.'" Reynolds also tells the author Douglass K. Daniel that from the first day she met Brooks he told her that he didn't want her in the part, but it wasn't his decision. "'He said he was stuck with me and he'd do the best he could with me,' Reynolds recalled. 'He hoped I could come through all right with him, because everybody else was so great, but he wasn't certain I could keep up with the others. He actually said he was stuck with me. And he said so in front of everybody, too. He was so cruel.'" Davis and Borgnine coached Reynolds on the side and Bette, not known to be a shrinking violet, told Reynolds once, according to the book, "'Don't pay any attention to him, the son of a bitch,' Davis told her. 'The only important thing is to work with the greats.'" Davis did get help from Brooks in her fight against the studio that a Bronx housewife shouldn't be wearing movie star costumes they wanted, so he supported her decision to buy clothes at a store like Mrs. Hurley would shop at in real life. Years later, Davis referred to Brooks as one of the greats. This wasn't the first time Brooks had treated a young actress oddly on a set, Anne Francis told Douglass Daniel for his book that he practically ignored her during the filming of Blackboard Jungle and she received no direction at all. Daniel suggests and, given the way Brooks ordered Borgnine and Davis to come up with an idea to fix a scene, that writing had been his greatest gift, he grew into a solid visual storyteller, but Brooks proved limited when it came to directing actors. Daniel wrote, "…(the accounts of Francis and Reynolds) suggested he had a limited ability to communicate what he wanted. He either paid them little attention…or tried to bully a performance from them." Despite that problem, 10 actors in Brooks-directed films earned Oscar nominations and three took home the statuette.

Prince and Tom Wopat(Yes — that Tom Wopat of Luke Duke fame) earned Tony nominations as the parents, Harvey Fierstein wrote the book and played the uncle (named Winston) and John Bucchino wrote the score. Why did Brooks make this one? Easy. He was under contract. MGM told him to make it, so he had no choice. From Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks, some of the cast talked on record about how Brooks could be a bit of a prick as a director. "I didn't know it at the time, but Brooks ate and digested actors for breakfast," Borgnine said later. "If things weren't working, he let you know it, and not gently." When a particular scene was not working to his satisfaction, (Brooks) ordered Borgnine and Davis to figure out the problem. Borgnine suggested a different pacing and Davis agreed the scene was better for it — as did (Brooks), though he offered Borgnine not praise but a putdown. 'Goddamn thinking actor.'" Reynolds also tells the author Douglass K. Daniel that from the first day she met Brooks he told her that he didn't want her in the part, but it wasn't his decision. "'He said he was stuck with me and he'd do the best he could with me,' Reynolds recalled. 'He hoped I could come through all right with him, because everybody else was so great, but he wasn't certain I could keep up with the others. He actually said he was stuck with me. And he said so in front of everybody, too. He was so cruel.'" Davis and Borgnine coached Reynolds on the side and Bette, not known to be a shrinking violet, told Reynolds once, according to the book, "'Don't pay any attention to him, the son of a bitch,' Davis told her. 'The only important thing is to work with the greats.'" Davis did get help from Brooks in her fight against the studio that a Bronx housewife shouldn't be wearing movie star costumes they wanted, so he supported her decision to buy clothes at a store like Mrs. Hurley would shop at in real life. Years later, Davis referred to Brooks as one of the greats. This wasn't the first time Brooks had treated a young actress oddly on a set, Anne Francis told Douglass Daniel for his book that he practically ignored her during the filming of Blackboard Jungle and she received no direction at all. Daniel suggests and, given the way Brooks ordered Borgnine and Davis to come up with an idea to fix a scene, that writing had been his greatest gift, he grew into a solid visual storyteller, but Brooks proved limited when it came to directing actors. Daniel wrote, "…(the accounts of Francis and Reynolds) suggested he had a limited ability to communicate what he wanted. He either paid them little attention…or tried to bully a performance from them." Despite that problem, 10 actors in Brooks-directed films earned Oscar nominations and three took home the statuette.

The following year, Brooks made another film that revolved around the hunt of an animal, though that just leads to much bigger issues in Something of Value, sometimes known as Africa Ablaze. Starring Rock Hudson and filmed in Kenya, the film, which I haven't seen, concerns tensions that erupt between formerly friendly colonial white settlers and the Kenyan tribesmen. It also began a run of films that Brooks adapted from serious literary sources. Something of Value had been written by Robert C. Ruark, a former journalist like Brooks, who fictionalized his experiences being present in Kenya during the Mau Mau rebellion. In 1958, the two authors he adapted carried names more prestigious and recognizable. The first movie released derived from a particularly literary source and Brooks didn't do all that heavy lifting alone. Julius and Philip Epstein did the original adaptation, working from the English translation of the novel by Constance Garnett before Brooks began his work writing a worthwhile screenplay that didn't run more than two-and-a-half hours out of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov. It wasn't easy. Brooks told Daniel that he "wrestled with the book for four months." What surprised me to learn, also according to what Brooks told Daniels, MGM assigned Karamazov to him. Brooks also said that he never initiated any of his films while under contract at MGM. I love Dostoyevsky. Hell, even a master such as Kurosawa couldn't pull off a screen adaptation of The Idiot. The only aspect of this film that holds your attention — actually it would be more accurate to say grabs you by your throat and keeps you awake for his moments — ends up being any scene with Lee J. Cobb playing the Father Karamazov. I don't know if Cobb realized that somebody needed to step up or what, but the brothers, with only Yul Brynner showing much charisma, also include William Shatner. It's almost embarrassing except for Cobb who got a deserved supporting actor Oscar nomination, the first of the 10 from Brooks-directed films.

The actor who Cobb lost that Oscar to that year had a major part in Brooks' other 1958 feature — the film adaptation of Tennessee Williams' Pulitzer Prize-winning play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. However, Burl Ives didn't win the prize for his great turn as Big Daddy, but for his role as a ruthless cattle baron fighting with another rancher over land and water in The Big Country. As with nearly all of Williams' works, movie versions castrated his plays' subtext (and sometimes just plain text) and this proved true with Cat as well, though the cast and its overriding theme of greed kept it involving enough. The film scored at the box office for MGM, taking in a (big for 1958) haul of $8.8 million — Leo the Lion's biggest hit of the year and third-biggest of the 1950s. It scored six Oscar nominations: best picture, best actress for Elizabeth Taylor as Maggie the Cat, best director for Brooks, best adapted screenplay for Brooks and James Poe best color cinematography for William Daniels and best actor for Paul Newman as Brick, Newman's first nomination and the film that truly cemented him as a star.

After the success of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Brooks decided to take an ocean voyage to Europe as a vacation. The writer-director packed the essentials for a lengthy trip: some articles on evangelism, a Gideon Bible a copy of Sinclair Lewis' novel Elmer Gantry and Angie Dickinson. By the time the ship docked in Europe, a first draft of a screenplay, based on the novel by one of the men who stood ready to

defend Brooks during The Brick Foxhole brouhaha with the Marines, lay finished. Dickinson, on the other hand, departed the cruise quite a while back, having grown annoyed by Brooks ignoring her for Elmer. For many lives, 1960 would prove quite eventful either professionally, personally or both. Brooks filmed the highly entertaining movie version of Elmer Gantry early in the year, directing one of his best friends, Burt Lancaster, for the first time in the title role, which is good since the film got made under the auspices of an independent Burt Lancaster/Richard Brooks Production. Lancaster gives one of his best performances and won his first Oscar. The film co-starred Jean Simmons, giving one of her greatest, most mesmerizing turns as Sister Sharon Falconer, the traveling tent show evangelist who gets Elmer into the biz. She fell for Brooks on the set. Within the calendar year, she ended her unhappy marriage to Stewart Granger and became Brooks' wife. Unfortunately, when the Oscar nominations came out the next year, Simmons got left out of the nominations for Elmer Gantry. It received five total. In addition to Lancaster's nomination and win for best actor, it received nominations for best picture; Shirley Jones as supporting actress, which she won; Andre Previn for best score for a drama or comedy; and Brooks for best adapted screenplay. That cruise paid off. Brooks won an Oscar and found a wife. Below, a bit of Lancaster at work — and singing too.

defend Brooks during The Brick Foxhole brouhaha with the Marines, lay finished. Dickinson, on the other hand, departed the cruise quite a while back, having grown annoyed by Brooks ignoring her for Elmer. For many lives, 1960 would prove quite eventful either professionally, personally or both. Brooks filmed the highly entertaining movie version of Elmer Gantry early in the year, directing one of his best friends, Burt Lancaster, for the first time in the title role, which is good since the film got made under the auspices of an independent Burt Lancaster/Richard Brooks Production. Lancaster gives one of his best performances and won his first Oscar. The film co-starred Jean Simmons, giving one of her greatest, most mesmerizing turns as Sister Sharon Falconer, the traveling tent show evangelist who gets Elmer into the biz. She fell for Brooks on the set. Within the calendar year, she ended her unhappy marriage to Stewart Granger and became Brooks' wife. Unfortunately, when the Oscar nominations came out the next year, Simmons got left out of the nominations for Elmer Gantry. It received five total. In addition to Lancaster's nomination and win for best actor, it received nominations for best picture; Shirley Jones as supporting actress, which she won; Andre Previn for best score for a drama or comedy; and Brooks for best adapted screenplay. That cruise paid off. Brooks won an Oscar and found a wife. Below, a bit of Lancaster at work — and singing too.With his next film, Brooks finally received the key that unlocked the leg shackles that bound him to MGM. The studio once again assigned him to a Tennessee Williams play. Though Sweet Bird of Youth did moderately well on Broadway, it wasn't one of The Glorious Bird's triumphs and took a long time to get to New York, starting as a one-act, premiering as a full-length play with a reviled ending in Florida in 1956 and, finally, the revised version's

opening in NY in 1959. (The play has yet to be revived on Broadway whereas, in contrast, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof has been revived four times, including twice in this young century, and A Streetcar Named Desire 's eighth Broadway revival currently runs.) Originally, its plot concerned a retired actress and a gigolo with dreams of Hollywood who brings her to his old Southern hometown to get away and runs into trouble with the town's corrupt political boss (Ed Begley) when he woos his daughter (Shirley Knight). Williams said he'd hoped for Brando and Magnani to play the parts on stage. Eventually, she became merely an aging actress and Geraldine Page and Paul Newman played the leads on Broadway. When it came time for the movie, according to legend, MGM desperately wanted Elvis for Newman's part, but the Colonel nixed that because he didn't like the character's morals. Instead, the great Page and Newman repeated their stage roles as did Rip Torn as the son of the political boss. Once again, Hollywood castrated a Williams play or, in this instance, literally didn't castrate it (people who know both the play and movie get that joke. Page and Knight received Oscar nominations in the lead and supporting actress categories, respectively, and Begley won as best supporting actor. In this clip, you can see Newman's Chance try to get a handle on Page's wasted Alexandra in their hotel room.

opening in NY in 1959. (The play has yet to be revived on Broadway whereas, in contrast, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof has been revived four times, including twice in this young century, and A Streetcar Named Desire 's eighth Broadway revival currently runs.) Originally, its plot concerned a retired actress and a gigolo with dreams of Hollywood who brings her to his old Southern hometown to get away and runs into trouble with the town's corrupt political boss (Ed Begley) when he woos his daughter (Shirley Knight). Williams said he'd hoped for Brando and Magnani to play the parts on stage. Eventually, she became merely an aging actress and Geraldine Page and Paul Newman played the leads on Broadway. When it came time for the movie, according to legend, MGM desperately wanted Elvis for Newman's part, but the Colonel nixed that because he didn't like the character's morals. Instead, the great Page and Newman repeated their stage roles as did Rip Torn as the son of the political boss. Once again, Hollywood castrated a Williams play or, in this instance, literally didn't castrate it (people who know both the play and movie get that joke. Page and Knight received Oscar nominations in the lead and supporting actress categories, respectively, and Begley won as best supporting actor. In this clip, you can see Newman's Chance try to get a handle on Page's wasted Alexandra in their hotel room.

Now a free agent, Brooks decided to stay that way — in essence becoming an independent filmmaker toward the end of his career instead of the beginning, as the path usually goes. He also defied that typical indie move of starting small — this wasn't John Cassavetes — but beginning this stage of his career more like the final films (and current ones for 1965) of David Lean. He went BIG. He even nabbed Lean's Lawrence to star in his adaptation of Joseph Conrad's Lord Jim, a longtime obsession of Brooks that he bought the rights to in 1958 for a mere $6,500. The filming took place in Hong Kong, Singapore and, dangerously in Cambodia as things grew tense. The movie crew's interpreter happened to be Dith Pran, the man the late Haing S. Ngor won an Oscar for playing in Roland Joffe's 1984 film The Killing Fields. O'Toole hated his time there, complaining about the living conditions — he isn't a fan of mosquitoes and snakes. Later, he also admitted he thought he'd been wrong for the part itself. Portions of the film ended up shot in London's Shepperton Studios as Cambodia became full of anti-American rage. When the film opened, it bombed and badly. Sony put it on DVD briefly, but it's currently out of print so, alas, I've never seen this one. Brooks did make an impression on O'Toole though, who told Variety when he died that Brooks was "the man who lived at the top of his voice."

Having a flop on the scale of Lord Jim the first time you produce your own film could really discourage a guy. However, it sure didn't show in what he produced next because The Professionals turned out to be the most well-made, entertaining film he'd directed up until this point in his career. (His next film swipes the most well-made title, but The Professionals continues to hold the prize for being one hell of a ride.) Based on a novel by Frank O'Rourke, the movie teamed Brooks with his pal Lancaster again. Set soon after the 1917 Mexican Revolution, early in the 20th century when the Old West and modern movement intermingle near the U.S.-Mexican border, it almost plays like a rough draft for Sam Peckinpah's admittedly superior Wild Bunch. Ralph Bellamy plays a rich tycoon who hires a team of soldiers of fortune to go in to Mexico and rescue his daughter who has been kidnapped by a guerrilla bandit (Jack Palance, hysterically funny and good despite making no attempt to appear Mexican). The team consists of Lancaster as a dynamite expert, Lee Marvin as a professional soldier, Robert Ryan as a wrangler and packmaster and Woody Strode as the team's scout and tracker. The film turned out to be a huge hit with audiences and critics alike and earned Brooks Oscar nominations for directing and adapted screenplay. The Academy also cited the cinematography of its director of photography, the master Conrad L. Hall, who would do some of the finest work of his career in Brooks' next film. Below, one of The Professionals' action sequences.

I hoped to complete this in two parts and considered breaking out the next film as a separate review because In Cold Blood stands firmly as Richard Brooks' masterpiece (and then there remain some other films to mention after that). So, another temporary pause.

Tweet

Labels: Angie Dickinson, Bellamy, Bette, Borgnine, Chayefsky, Debbie Reynolds, Geraldine Page, Jean Simmons, Lancaster, Lee J. Cobb, Liz, Marvin, Newman, O'Toole, Peckinpah, Rip Torn, Shatner, Tennessee Williams, Vidal

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, November 07, 2011

A fabulous disaster

By Edward Copeland

For people around my age, one of the biggest laughs in (500) Days of Summer comes when Zooey Deschanel's Summer tells Joseph Gordon-Levitt's Tom that lately they've been acting like Sid and Nancy. Tom takes offense, thinking she's comparing him to the late Sex Pistols bass guitarist who stabbed girlfriend Nancy Spungen to death, but Summer corrects him, "No, I'm Sid Vicious." For anyone such as myself for whom Alex Cox's Sid & Nancy served as a seminal film during high school years, it is a hysterical moment. Today marks the 25th anniversary of the U.S. release of Cox's film. There's always a danger when revisiting treasured films of your youth, that the experience won't be the same decades down the road but I'm pleased to report that a quarter-century later, Sid & Nancy works better as a movie than I remember it doing when I originally saw it.

When the movie begins, we gaze upon a young Gary Oldman's version of Sid Vicious staring blankly, without expression, at a TV in a dark hotel room as detectives ask if he is the one who called 911. He says nothing, but we glimpse his bloody hand for a moment. What struck me isn't the context of the scene — no matter how long it's been since you've seen Sid & Nancy, you know that she's dead — no, what struck me is how amazingly young Gary Oldman looks. The actor in this 1986 film bears so little resemblance to the actor working under that name today. Can this possibly be the same man? This remarkably talented actor, still a couple of years shy of his 30th birthday then, who transformed himself so memorably into the drugged-out punk rock legend couldn't possibly be the same man now is in his early 50s and seen most often as Commissioner Gordon in Christopher Nolan's Batman movies or Sirius Black in Harry Potter films? It just seems impossible, doesn't it? It's great to hear the buzz that Oldman is receiving for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy because embarrassments dominate his credits more than winners since at least 1995. Some examples: Lots of voice work for video games, The Scarlet Letter, Lost in Space, Hannibal, the TV show Friends and voices in Disney's 3-D Christmas Carol and Kung Fu Panda 2. Thankfully, we still have his Sid Vicious to be amazed by.

An even larger, more existential query loomed over me while I watched Sid & Nancy again, for the first time in I don't know how many years and began to think about what I would write in this tribute. First, came relief that I didn't find myself disappointed as has happened before when returning to a sacred relic from an earlier archaeological phase of my life. Then, I was struck by a question that had never occurred to me before about the movie — what appeal did it hold for me and many of my friends back in high school? We weren't punk rock enthusiasts — that day had largely passed though many of us owned the album Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's The Sex Pistols (and I mean album — on wax), but we tended to be eclectic musically. We weren't lurking around shooting heroin in our veins (though I can't make that statement with 100% certainty concerning one of our informal group). Why did Sid & Nancy speak to us in such a profound way that we not only fell for the film but went multiple times? The theater which showed this movie (and we often went to midnight showings — it wasn't always The Rocky Horror Picture Show or Pink Floyd — The Wall) would be the site for both the beginnings and ends of teen hookups. I guess watching a love story about two drug-addicted people, one of whom stabs the other to death, just brings out the romance

in people. As I pondered the possibilities of why this cinematic portrait of punk had such pull over us, I looked over my notes and discovered one word that seemed to recur from different characters in the movie: Bored. There lies the link between the punk rockers in the movie and the suburban teens in a Bible Belt multiplex watching them: Both groups felt stifled to the point of losing their minds. Sid Vicious found his escape in drugs and his music; we had to make do with watching movies about him until we were old enough to get the hell out of town. In one scene in the movie, someone says, (you can't really tell who because there's a jumble of bodies crowded in sleeping bags and blankets on an apartment floor) "You know I was so bored once I fucked a dog passionately." Thankfully, it never got that bad here (that I know about). Sid & Nancy shows that even the punk fans grew tired of punk, as in a scene at a club where several sit behind a wall, not even paying attention to the Pistols. One has even brought her baby adorned with a green Mohawk haircut. One of the group, Clive (Mark Monero) announces, "Ain't gonna be a punk no more. Gonna be a rude boy just like my dad." When you consume so many drugs that you can't tell what day or country you're in, a state of ennui comes easy as later when Nancy (Chloe Webb, who's as great as Oldman) lies in bed with Sid and complains that she's so bored that she hates her life. "This is just a rough patch. Things'll be much better when we get to America, I promise," Sid reassures her. "We're in America. We've been here a week. New York is in America, you fuck," she yells at him, prompting him to look out the balcony at the Hotel Chelsea sign.

in people. As I pondered the possibilities of why this cinematic portrait of punk had such pull over us, I looked over my notes and discovered one word that seemed to recur from different characters in the movie: Bored. There lies the link between the punk rockers in the movie and the suburban teens in a Bible Belt multiplex watching them: Both groups felt stifled to the point of losing their minds. Sid Vicious found his escape in drugs and his music; we had to make do with watching movies about him until we were old enough to get the hell out of town. In one scene in the movie, someone says, (you can't really tell who because there's a jumble of bodies crowded in sleeping bags and blankets on an apartment floor) "You know I was so bored once I fucked a dog passionately." Thankfully, it never got that bad here (that I know about). Sid & Nancy shows that even the punk fans grew tired of punk, as in a scene at a club where several sit behind a wall, not even paying attention to the Pistols. One has even brought her baby adorned with a green Mohawk haircut. One of the group, Clive (Mark Monero) announces, "Ain't gonna be a punk no more. Gonna be a rude boy just like my dad." When you consume so many drugs that you can't tell what day or country you're in, a state of ennui comes easy as later when Nancy (Chloe Webb, who's as great as Oldman) lies in bed with Sid and complains that she's so bored that she hates her life. "This is just a rough patch. Things'll be much better when we get to America, I promise," Sid reassures her. "We're in America. We've been here a week. New York is in America, you fuck," she yells at him, prompting him to look out the balcony at the Hotel Chelsea sign.

Watching Sid & Nancy now makes it easier to appreciate what Alex Cox accomplishes on a filmmaking level. He tosses out the idea of a conventional narrative (and shouldn't that be required when telling the story of punk pioneers?) while at the same time employing many standard cinematic techniques to great effect. When they get to the infamous concert on the ship on the Thames and the London police make them pull ashore, Cox throws in a short but effective tracking shot of Sid and Nancy, arm in arm and in love, oblivious to the chaos around them, as they simply walk away from the ship and the melee on the docks just to be with one another. Cox also frequently likes suddenly to distance us from characters, usually

the title ones, but not always, so they appear as specks against a background that gives the scene a different connotation such as a message about abortion. He's not above some wacky film use either. When Sid, Nancy and her friend Gretchen (played by none other than Courtney Love) cross a vacant lot and see some kids picking on another one, Sid tells them to stop. The bullies ask him who he thinks he is. "I'm Sid Vicious," he answers and then the kids run away in fast-motion speed like something out of an Our Gang short. A moment such as that reminds me of what really goes unappreciated about Sid & Nancy — its nearly continuous strain of humor, albeit mostly dark humor. Truth be told, that aspect led to my friends and I returning to the film as much as any empathy for the bored. If you just lay out the basic plot of the film — The true story of heroin-addicted musician and his heroin-addicted girlfriend who he stabs to death but doesn't face justice for his crime because he overdoses first — well, it doesn't exactly sound like a rollicking night out. The first response to that description probably would be something like, "Sounds bleak." The word that begins the IMDb plot summary is "morbid." I'm not trying to convince you that Sid & Nancy produces a laugh riot, but I've sat through many bleak films in my time (Wendy and Lucy leaps to mind) and Sid & Nancy isn't one of them because Cox and his collaborators approached the subject matter with such verve, creativity and vitality.

the title ones, but not always, so they appear as specks against a background that gives the scene a different connotation such as a message about abortion. He's not above some wacky film use either. When Sid, Nancy and her friend Gretchen (played by none other than Courtney Love) cross a vacant lot and see some kids picking on another one, Sid tells them to stop. The bullies ask him who he thinks he is. "I'm Sid Vicious," he answers and then the kids run away in fast-motion speed like something out of an Our Gang short. A moment such as that reminds me of what really goes unappreciated about Sid & Nancy — its nearly continuous strain of humor, albeit mostly dark humor. Truth be told, that aspect led to my friends and I returning to the film as much as any empathy for the bored. If you just lay out the basic plot of the film — The true story of heroin-addicted musician and his heroin-addicted girlfriend who he stabs to death but doesn't face justice for his crime because he overdoses first — well, it doesn't exactly sound like a rollicking night out. The first response to that description probably would be something like, "Sounds bleak." The word that begins the IMDb plot summary is "morbid." I'm not trying to convince you that Sid & Nancy produces a laugh riot, but I've sat through many bleak films in my time (Wendy and Lucy leaps to mind) and Sid & Nancy isn't one of them because Cox and his collaborators approached the subject matter with such verve, creativity and vitality.Speaking of the painful Wendy and Lucy, two scenes in Sid & Nancy reminded me of that pretentious piece of misery (but in a good way). One emphasizes the careful balancing act Alex Cox and Abbe Wool's screenplay took with scenes that show these characters' desperation (and that one gets hit out of the park by Chloe Webb's superb work. She and Oldman both were robbed in not receiving Oscar

recognition). The second one plays as sort of a twisted homage to another filmmakers' work. Both keep humor behind the anger and tears. In the first, the infamous telephone booth scene, anxious for drugs and out of cash, Nancy calls her mom in America in the middle of the night London time telling her that she and Sid just got married. She assures her mother that Vicious isn't at all as they describe him in the newspapers and no, she's not pregnant either. Not known for her subtlety, Nancy suggests that her mom would want to send them a wedding gift for their honeymoon. Nancy explains that they don't have a place yet, so money would be better and since it's a different time there, why doesn't she head over to Western Union and wire some to them and they can pick it up in the morning. We never hear the mother's side, but it's very reminiscent of that call Wendy (Michelle Williams) makes to her sister) who has heard all her crap before and doesn't want to deal with it. (Lucky her — I immediately wanted to watch a movie called Wendy's Sister and Lucy.) Nancy loses it. "I am so married!" Nancy yells into the phone. "YOU DON'T CARE ABOUT ME! IF YOU DON'T SEND US MONEY, WE'RE BOTH GONNA DIE! FUCK YOU!" Nancy screams before she hangs up and throws such a fit she breaks the glass in the phone booth. Sid gets her to rest down on the curb. "I fucking hate them! I fucking hate them! Fucking motherfuckers! They wouldn't send us any money! They said we'd spend it on DRUGS!" she tells Sid. Then Oldman gets the scene's deadpan punchline: "We would."

recognition). The second one plays as sort of a twisted homage to another filmmakers' work. Both keep humor behind the anger and tears. In the first, the infamous telephone booth scene, anxious for drugs and out of cash, Nancy calls her mom in America in the middle of the night London time telling her that she and Sid just got married. She assures her mother that Vicious isn't at all as they describe him in the newspapers and no, she's not pregnant either. Not known for her subtlety, Nancy suggests that her mom would want to send them a wedding gift for their honeymoon. Nancy explains that they don't have a place yet, so money would be better and since it's a different time there, why doesn't she head over to Western Union and wire some to them and they can pick it up in the morning. We never hear the mother's side, but it's very reminiscent of that call Wendy (Michelle Williams) makes to her sister) who has heard all her crap before and doesn't want to deal with it. (Lucky her — I immediately wanted to watch a movie called Wendy's Sister and Lucy.) Nancy loses it. "I am so married!" Nancy yells into the phone. "YOU DON'T CARE ABOUT ME! IF YOU DON'T SEND US MONEY, WE'RE BOTH GONNA DIE! FUCK YOU!" Nancy screams before she hangs up and throws such a fit she breaks the glass in the phone booth. Sid gets her to rest down on the curb. "I fucking hate them! I fucking hate them! Fucking motherfuckers! They wouldn't send us any money! They said we'd spend it on DRUGS!" she tells Sid. Then Oldman gets the scene's deadpan punchline: "We would."

The other sequence proves truly hysterical (unless you were living it I imagine). While in America, Nancy takes Sid to visit her grandparents in a dinner scene that plays as if it's a twisted homage to Alvy's visit to Annie's parents in Woody Allen's Annie Hall. There are other scenes

that obviously influenced later films or seem to predict other filmmakers' recurring trademarks. Recognizable character actors Gloria LeRoy (who still works today, which is her 80th birthday) and Milton Seltzer (who passed in 2006) play Granma and Granpa whose table gets filled out by many other men and women, mostly younger, whose relationship never is explained. What's so funny about the scene is that Nancy doesn't change herself in the presence of her grandparents and the young people, sprinkling her speech with F-bombs as always even though her demeanor is generally friendly. Sid comes off as downright polite — except for not wearing a shirt to the dinner table. The highlight comes when Granpa starts questioning Sid as he would any suitor. "So are you gonna make an honest woman of our Nancy, Sid?" he asks Vicious, who obviously misses the gist of the

that obviously influenced later films or seem to predict other filmmakers' recurring trademarks. Recognizable character actors Gloria LeRoy (who still works today, which is her 80th birthday) and Milton Seltzer (who passed in 2006) play Granma and Granpa whose table gets filled out by many other men and women, mostly younger, whose relationship never is explained. What's so funny about the scene is that Nancy doesn't change herself in the presence of her grandparents and the young people, sprinkling her speech with F-bombs as always even though her demeanor is generally friendly. Sid comes off as downright polite — except for not wearing a shirt to the dinner table. The highlight comes when Granpa starts questioning Sid as he would any suitor. "So are you gonna make an honest woman of our Nancy, Sid?" he asks Vicious, who obviously misses the gist of the question. "She's always been an honest woman to me, grandpa, sir. She never lied to me," Sid tells him. Granpa tries again, "What are your intentions?" Nancy steps in to outline the couple's plans for this: Monday they'd go to the methadone clinic, then she'd get Sid a few gigs (this takes place after The Pistols have broken up, but I'll get back to that), then they'd move to Paris "and go out in a blaze of glory," Nancy says. "Don't worry, you'll be proud of us," Sid reassures the grandparents who look anything but reassured. As the family retires to the living room, Sid promptly passing out in a chair from a bit too much

question. "She's always been an honest woman to me, grandpa, sir. She never lied to me," Sid tells him. Granpa tries again, "What are your intentions?" Nancy steps in to outline the couple's plans for this: Monday they'd go to the methadone clinic, then she'd get Sid a few gigs (this takes place after The Pistols have broken up, but I'll get back to that), then they'd move to Paris "and go out in a blaze of glory," Nancy says. "Don't worry, you'll be proud of us," Sid reassures the grandparents who look anything but reassured. As the family retires to the living room, Sid promptly passing out in a chair from a bit too much vodka, Nancy in his lap. Nancy assumes that they'll be staying there but Granma comes in and, being as polite as she can, tells her she thought it would be better if they stayed at a motel so they booked them a room there. Nancy admits she was hoping they'd drive them to the methadone clinic, but Granma says it's impossible because they are going on a trip the next day. One of the never-define teenage boys blurts, "Since when?" Granpa also gives Nancy money for transportation. She's wise enough to know what's up and storms out, but Vicious remains in the chair like a statue. The grandparents argue about how they can get him out. Eventually they do, and we see Sid and Nancy in the hotel lying in the dark watching TV. While much of the sequence has been played for laughs, it might be the film's most touching moment. "These people. Really lovely. Best fuckin' food I ever ate," Sid tells Nancy about her grandparents with a wisp of sadness in his voice. "Why'd they throw us out?" Just as he didn't understand what the meaning of Granpa's questions were, Vicious can't fathom how these people that seemed to be friendly and treating him like a human being would suddenly throw him out for some unknown reason. Nancy knows, and she gives the scene its clincher. "Because they know me." Oldman and Webb created such a magnificent acting partnership in Sid & Nancy that I wonder why no one has devised a project in 25 years that paired these two again.

vodka, Nancy in his lap. Nancy assumes that they'll be staying there but Granma comes in and, being as polite as she can, tells her she thought it would be better if they stayed at a motel so they booked them a room there. Nancy admits she was hoping they'd drive them to the methadone clinic, but Granma says it's impossible because they are going on a trip the next day. One of the never-define teenage boys blurts, "Since when?" Granpa also gives Nancy money for transportation. She's wise enough to know what's up and storms out, but Vicious remains in the chair like a statue. The grandparents argue about how they can get him out. Eventually they do, and we see Sid and Nancy in the hotel lying in the dark watching TV. While much of the sequence has been played for laughs, it might be the film's most touching moment. "These people. Really lovely. Best fuckin' food I ever ate," Sid tells Nancy about her grandparents with a wisp of sadness in his voice. "Why'd they throw us out?" Just as he didn't understand what the meaning of Granpa's questions were, Vicious can't fathom how these people that seemed to be friendly and treating him like a human being would suddenly throw him out for some unknown reason. Nancy knows, and she gives the scene its clincher. "Because they know me." Oldman and Webb created such a magnificent acting partnership in Sid & Nancy that I wonder why no one has devised a project in 25 years that paired these two again.

Granted, the movie focuses on the couple, but it also looks at The Sex Pistols and the music industry in England at the time as well and that's where we find a lot of the humor as well. Though Sid & Nancy really only takes time to develop John "Johnny Rotten" Lydon (well played by Andrew Schofield unless you are John Lydon or are friends with John Lydon) with the other band members being more or less ciphers. While the movie portrays him as a prick at times, it also shows him as someone who aspires to some degree of professionalism, something difficult to reach when your bass guitarist tends to be wasted or not there at all. They'll be on stage at a club, ready to go and Sid will be roughhousing elsewhere in the crowd. "Sid, we'll go on when you're ready," John ("He hates being called Johnny") will shout. The movie also has much fun

with its take on the band's manipulative manager Malcolm McLaren (acted with a perpetually bemused grin by David Hayman), who at times seems less concerned that Sid might be destroying himself as long as he gets press out of it. The first time we see Malcolm, he's standing outside a club trying to lure people into a performance. "Is it fucking worth it? Yes it is," he tells anyone who passes by. When Lydon and the other members come to him to complain, explaining that sometimes they have to turn off Vicious' amp because he isn't even playing the same song that the rest of the band is and they need a new bass guitarist, Malcolm doesn't seem upset. Instead, he replies, "Sidney's more than a mere bass player. He's a fabulous disaster. He's a symbol, a metaphor. He embodies the dementia of a

with its take on the band's manipulative manager Malcolm McLaren (acted with a perpetually bemused grin by David Hayman), who at times seems less concerned that Sid might be destroying himself as long as he gets press out of it. The first time we see Malcolm, he's standing outside a club trying to lure people into a performance. "Is it fucking worth it? Yes it is," he tells anyone who passes by. When Lydon and the other members come to him to complain, explaining that sometimes they have to turn off Vicious' amp because he isn't even playing the same song that the rest of the band is and they need a new bass guitarist, Malcolm doesn't seem upset. Instead, he replies, "Sidney's more than a mere bass player. He's a fabulous disaster. He's a symbol, a metaphor. He embodies the dementia of a nihilistic generation." Eventually, even McLaren sees the need for intervention. At first, he tries to talk his assistant Phoebe (Debby Bishop) to be Sid's handler for a couple of months, but she wants no part of it. He asks why. "Infectious hepatitis, loony girlfriend, drugs?" she lists off. "Boys will be boys," Malcolm counters. Everyone agrees when the discussion of an American tour comes up, that it's a good chance to separate Sid from Nancy for awhile, since both band and management see her as the bad influence. At a meeting at a small restaurant, they make it clear: no wives or girlfriends can go. When Nancy puts up a fit — Sid appears catatonic the whole time — Phoebe makes it clear that if they can't separate for a few weeks, Sid will be replaced. So Sid goes alone and that tour ends up being the band's end as they get booked in inappropriate venues by people not even clear who they are. (As in Atlanta, as you can see in the sign below.) The final straw comes when Sid heads to a party and walks through a hotel's glass door. When he reunites with Nancy and she decides to manage him, things go from bad to worse and everyone pretty much knows where this story ends.

nihilistic generation." Eventually, even McLaren sees the need for intervention. At first, he tries to talk his assistant Phoebe (Debby Bishop) to be Sid's handler for a couple of months, but she wants no part of it. He asks why. "Infectious hepatitis, loony girlfriend, drugs?" she lists off. "Boys will be boys," Malcolm counters. Everyone agrees when the discussion of an American tour comes up, that it's a good chance to separate Sid from Nancy for awhile, since both band and management see her as the bad influence. At a meeting at a small restaurant, they make it clear: no wives or girlfriends can go. When Nancy puts up a fit — Sid appears catatonic the whole time — Phoebe makes it clear that if they can't separate for a few weeks, Sid will be replaced. So Sid goes alone and that tour ends up being the band's end as they get booked in inappropriate venues by people not even clear who they are. (As in Atlanta, as you can see in the sign below.) The final straw comes when Sid heads to a party and walks through a hotel's glass door. When he reunites with Nancy and she decides to manage him, things go from bad to worse and everyone pretty much knows where this story ends.

As I mentioned before, the influences — intentional and otherwise — on other films and filmmakers become more apparent 25 years later. For example, it's even more obvious why Martin Scorsese thought of using Sid Vicious' take on "My Way" as the ending song for Goodfellas when you see the re-creation of the video for it in Sid & Nancy (and that is Gary Oldman doing the singing by the way), especially following the quick take of Joe Pesci as Tommy aping the famous shot from Edwin S. Porter's The Great Train Robbery. (Pardon the Portuguese subtitles.) Embedding is disabled for the Goodfellas ending, but click here.

While they stay at the Hotel Chelsea, Sid and Nancy manage to start a fire in their room and they just stare at it, fire fighters eventually coming in around them to extinguish the flames. The hotel manager (Sandy Baron), always bragging to potential tenants about the high-class clientele that have lived there, does berate them slightly but moves them to a room on the first floor accompanied by a slow-moving man who appears to be a decrepit bellhop, but doesn't appear to be that old. The only item he carries is Sid's guitar, which he hands back to him as he says something slow and cryptic along the lines of "Bob Dylan was born here" and

then extends his hand for a trip. It's the type of character we'd see frequent many a work by David Lynch, but I don't recall one making an appearance yet. They didn't really kick in until Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart a few years later. It could be pure coincidence, but when I saw him again, Lynch came to my mind immediately. Musicians and fires aren't that unusual, but it did in a way remind me of Oliver Stone's awful movie The Doors, which also only bothered to define two members of the band. As for the fire, I'm still waiting to find out how the hell Meg Ryan got out of that closet. Imagery may be what I took away most from this return visit because I'd forgotten, if I'd ever known, that the director of photography for Sid & Nancy was the ultra-talented and, of late, Coen brothers' favorite Roger Deakins. For those of you keeping score at home, Deakins has received nine Oscar nominations for cinematography and won zero. His nominations have come for The Shawshank Redemption, Fargo, Kundun, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, The Man Who Wasn't There, The Assassination of Jesse James By the Coward Robert Ford, No Country for Old Men, The Reader (shared with Chris Menges) and True Grit. Look at it this way: Deakins has received more nominations for best cinematography without winning than Peter O'Toole went winless for best actor — and they at least gave O'Toole an honorary Oscar.

then extends his hand for a trip. It's the type of character we'd see frequent many a work by David Lynch, but I don't recall one making an appearance yet. They didn't really kick in until Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart a few years later. It could be pure coincidence, but when I saw him again, Lynch came to my mind immediately. Musicians and fires aren't that unusual, but it did in a way remind me of Oliver Stone's awful movie The Doors, which also only bothered to define two members of the band. As for the fire, I'm still waiting to find out how the hell Meg Ryan got out of that closet. Imagery may be what I took away most from this return visit because I'd forgotten, if I'd ever known, that the director of photography for Sid & Nancy was the ultra-talented and, of late, Coen brothers' favorite Roger Deakins. For those of you keeping score at home, Deakins has received nine Oscar nominations for cinematography and won zero. His nominations have come for The Shawshank Redemption, Fargo, Kundun, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, The Man Who Wasn't There, The Assassination of Jesse James By the Coward Robert Ford, No Country for Old Men, The Reader (shared with Chris Menges) and True Grit. Look at it this way: Deakins has received more nominations for best cinematography without winning than Peter O'Toole went winless for best actor — and they at least gave O'Toole an honorary Oscar.What boggled my mind then and still does now are people who think that somehow Sid & Nancy comes off as an endorsement for heroin use. Being broke, unaware of your surroundings, killing a loved one and accidentally yourself — tell me where I sign up. As the methadone case worker (Sy Richardson) tells the duo, who dismiss it as "political bullshit" when he paints it as a government conspiracy he claims to have seen first-hand in Vietnam, "(S)mack is the great controller. Keeps people stupid when they could be smart." Yes, the fantastical ending paints the idea that perhaps Sid and Nancy reunite on another plane, but that doesn't mean it's endorsing smack addiction as the path. Still, those closing sequences seem more spellbinding today than before, Of course, no knew in 1986, the symbolic power of including this image of Sid Vicious' path to a pizza joint after making bail in Nancy's slaying.

I almost could have created a 25th anniversary tribute to Sid & Nancy composed entirely of photos. As it is, I've left out many line and anecdotes that I wanted to write about, but I keep cutting them to squeeze in more art — and I'm not even getting all the art in that I wanted. I didn't begin to get into discussing what the hell has happened to Alex Cox or Chloe Webb. Still, there are so many shots I didn't get in — Sid and Nancy having a mock shoot-out on the roof of a hotel, Nancy hanging upside down from a hotel window, Malcolm scaring off men beating up Sid simply by pointing his finger like a gun, Sid spontaneously dancing with some kids after the pizza, Nancy's friend Brenda and her S&M business — but I do want to use one shot from the closing reunion sequence because I think it's the most beautiful.

Finally, just in case anyone might still believe that the movie serves as an ad for heroin, the final card that appears on the screen.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Animation, Christopher Nolan, Coens, Disney, Dylan, Gordon-Levitt, Lynch, Michelle Williams, Movie Tributes, Music, O'Toole, Oldman, Oliver Stone, Oscars, Pesci, Scorsese, Twin Peaks, Woody, Zemeckis

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

My Missing Picture Nominees: Sons and Lovers (1960)

By Edward Copeland

Before I begin discussing the 1960 best picture nominee Sons and Lovers, based on the famed D.H. Lawrence novel and which earned acclaimed Oscar-winning cinematographer Jack Cardiff his only nomination as a director, I'd like to use this occasion to point out yet another reason any true film lover should dump their streaming only Netflix option in favor of DVDs only. Sons and Lovers is one of the few Oscar nominees for best picture that I've never been able to see, but Netflix only carries it on streaming so I've been trying to watch any titles they have only on streaming before I switch to DVDs only. Cardiff filmed Sons and Lovers in luscious black-and-white CinemaScope (actually his d.p., the equally famous and lauded Freddie Francis was the cinematographer on the film). While you will see the opening and closing credits in the intended aspect ratio, the film in between will be cropped and squeezed for no good reason. Other streaming titles are shown in CinmaScope from beginning to end. Another strike against Netflix streaming. You won't get that on the DVD unless it's a DVD that only offers fullscreen.

As you might expect, a film being directed by Jack Cardiff, the brilliant d.p. behind the look of the Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger classics A Matter of Life and Death aka Stairway to Heaven, Black Narcissus (for which he won the Oscar for cinematography) and The Red Shoes. He also shot Under Capricorn for Hitchcock, The African Queen for Huston, War and Peace for King Vidor (earning another Oscar nomination) and garnered his final cinematography nomination for Joshua Logan's Fanny in 1961. Believe it or not, he even served as d.p. on Rambo: First Blood Part II. The Academy saw fit to give him an honorary Oscar for his long career of exceptional work at the ceremony held in 2001.

Freddie Francis, his d.p. for Sons and Lovers, took home the Oscar for his work on the film. Despite a long list of impressive work, Francis was only nominated for the Oscar one other time — for Glory — and he won. Some of Francis' other films included Scorsese's version of Cape Fear and, his final film, David Lynch's The Straight Story. Also on Cardiff's crew as an assistant director was Peter Yates, who would go on to direct films as diverse as Bullitt and Breaking Away.

I wish I could say that I've read the D.H. Lawrence novel upon which the film is based, but the title itself makes it obvious that the adaptation by Gavin Lambert (who co-wrote Nicholas Ray's films Bigger Than Life and Bitter Victory) and T.E.B. Clarke (Oscar-winning writer of The Lavender Hill Mob) has taken some big liberties from the book. I mean the title indicates multiple sons, but aside from one brief scene that kills off Arthur (Sean Barrett), son of Walter and Gertrude Morel (the great Trevor Howard and Wendy Hiller, by far the film's greatest asset beyond its look and design), a couple of scenes with their son William (William Lucas), who lives in London, the film revolves around their son Paul (Dean Stockwell).

According to summaries of the novel online, Lawrence's book begins with a focus on the turbulent marriage of Walter, a working class miner in Nottingham, England, with a penchant for liquor and Gertrude, who develops unhealthy attachments to her sons. William still moves to London in the book, but is the eldest son and Gertrude's favorite, though he takes ill and dies. Arthur is an afterthought in the book and they also have a sister named Annie who doesn't exist in the film at all. None of the children follow dad into the mines. A near-death experience for Paul (in the novel, not the film) makes Gertrude transfer her obsession to him. Aspiring to be an artist, he gets a chance to move to London when a patron (Ernest Thesiger, who played Dr. Pretorious in 1935's Bride of Frankenstein) sees promise in Paul's work, but Paul abandons his chance to leave when he witness an incident of his drunken father mistreating his mother and stays, fearful of what his lout of a dad could do to his mom.

His mother also subtly and not so subtly interferes with Paul's romances, first with the overly pious Miriam (Heather Sears), who teases the poor lad unmercifully. and later with the married but separated suffragette Clara (Mary Ure) he meets when he takes a job at a sewing factory. (His boss is played by Donald Pleasence). While Miriam runs frigid, Clara burns hot and Paul eats her up, much to the disdain of Clara's cheating husband and his possessive mother.

Howard was nominated as best actor, though he's really supporting and deserved a nomination there. Ure was nominated as supporting actress. Hiller didn't get remembered at all, which is a shame. Given the five films up for best picture in 1960, they all were going to finish a distant second to Billy Wilder's The Apartment. John Wayne's starring in and directing The Alamo automatically lands in fifth. The middle three are tightly bunched, but I believe I'd rank Elmer Gantry second, then The Sundowners, and place Sons and Lovers fourth.