Friday, November 30, 2007

It's Good to Be Bad (Make that Really, Really Bad)

By Josh R

Here she is, boys … here she is, world … here’s Googie!

From the opening strains of “Tomorrow,” Little Orphan Annie’s sugar-coated ballad of optimism that kicks off a medley of showtunes performed (or to be more accurate, decimated) by Googie Gomez — a cabaret singer who couldn’t locate a melody if one hit her over the head — you know you’re in for something special. For Googie, a pint-size, glitter-encrusted dynamo with a king-size ego, a tin ear and the most ridiculous collection of wigs this side of Clown College, is not simply untalented — she’s untalented with a vengeance. Flanked by peppy go-go boys and bulldozing her way through the collected works of Jule Styne, Kander & Ebb and Rodgers & Hammerstein without betraying so much as a shred of musicality, she hits every wrong note with the hard-driving intensity and unshakable conviction of one who’s determined to see her name in lights, no matter who she has to step over or how many eardrums she shatters in the process. For 10 magnificently grotesque minutes, during which this legend-in-her-own-mind produces sounds alternately reminiscent of a cat being strangled, a miscalibrated foghorn and Fran Drescher, there isn’t a more joyful noise to be heard on Broadway.

Chalk this up to the fact that this tiny cyclone of terror in polyester prints and day-glo lipstick — whose woefully misplaced confidence is matched only by her ruthless hunger for success — is played by the infinitely resourceful Rosie Perez, an actress who knows exactly which notes to hit even when hitting the wrong ones. Her gut-busting, go-for-broke turn as a tone-deaf diva, hubristic and deluded enough to think she can make Streisand and Midler cower in her shadow, constitutes the only compelling reason to make a trip to Roundabout Theatre Company’s revival of The Ritz, a comedy set in a gay bathhouse and currently flexing its somewhat puny muscles at Studio 54.

Terrence McNally’s 1975 hit play, a product of the carefree era before the specter of AIDS brought an end to the heyday of the bathhouses, comes equipped with the standard trappings of farce. The helium-weight plot, which involves a lot of slamming doors, sight gags and multiple instances of mistaken identity, attempts to mine humor from the shell-shocked reactions of hetero squares dropped headlong into a flamboyantly gay universe. Gaetano Proclo, a hapless sanitation company president on the run from the mob, asks a cab driver to take him to the last place anyone would ever think to look for him; the driver duly deposits him at The Ritz, a seedy Dionysian pleasure palace populated mostly by buff specimens of manhood in teeny-tiny towels. It takes a while for Proclo to figure out that he hasn’t wandered into any run-of-the-mill health club; as played by Kevin Chamberlin as the kind of sheltered, complacent midwesterner who could listen to recordings of The Village People for hours on end without catching a whiff of irony, he registers his dawning awareness of the wonders on display with the aghast, wide-eyed befuddlement of a Benedictine novitiate trapped backstage at a Beastie Boys concert. While dodging the advances of a determined “chubby chaser” — a nimble little fellow who prefers his conquests on the portly side — and the dogged Googie, who has mistaken him for a Broadway producer, Proclo tries to evade capture by the assortment of private detectives, Mafia thugs, confused spouses and other lunatics who have descended upon The Ritz en masse for the purpose of tracking him down. Hiding in the steam room proves not to be the best idea.

The steam room is, of course, one of the prime attractions of the titular establishment, at least for the men who frequent it (and if you don’t understand why, I’m not going to spell it out for you). There is literally plenty of steam on display in Joe Mantello’s raucous new staging — kudos to the dry ice machine operators — and the result of so much moisture in a contained space is the unmistakable presence of mildew. The tradition of farce doesn’t demand much in the way of dramatic substance — if anything, it would seem to call for a complete lack of it — but it does require an element of cleverness, and humor that seems fresh even if the gags involved date back to Plautus. Most of the jokes in The Ritz are of the variety that you can see coming from a mile away, and what might have seemed titillating and risqué to audiences of the 1970s feels downright quaint in the present context. Great contemporary farces — Michael Frayn’s Noises Off! being an obvious example — can create an element of surprise in the way they frame their tried-and-true Keystone Kops style antics within a tight, ingenious structure that builds suspense through tension and release. In The Ritz, the sequence of slapstick set pieces feels haphazard and forced; nothing really fits together in the way that it’s supposed to, and the jokes feel more tired than they would otherwise — instead of a chain of firecrackers going off, The Ritz creates the impression of one slow fizzle.

The energetic cast members do as much as they can playing a broad spectrum of types … make that very broad, indeed. In addition to Patrick Kerr’s indefatigable chubby chaser, who is nothing if not dogged, there is Brooks Ashmanskas’ sashaying nymphomaniac, an irrepressible cut-up who serves as Proclo’s friendly tour guide through the realm of All Things Gay; Terrence Riordan as the dim-bulb private dick with the sculpted body of a marble Adonis and the speaking voice of a pre-adolescent girl; and David Turner and Lucas Near-Verbrugghe as a twin pair of bathhouse attendants who dispense towels and one-liners with twinkling good cheer. Among the scantily clad ensemble players — most of whom have obviously logged many hours at the gym — are actors playing characters listed simply as “Man in Chaps” and “Crisco Patron” (in reference to the shortening substitute; use your imagination). Anchoring the proceedings quite ably is the talented Mr. Chamberlin, who wrings more laughs than could be reasonably expected from McNally’s archaic set-ups. Scott Pask’s clever set design, which suggests the vast dimensions and labyrinthine twists and turns of this tacky sexual playground, abets the devices of farce in a way that the text only occasionally manages to do.

But the evening unequivocally belongs to the invaluable Ms. Perez, whose energy never flags even as the production around her tends to stall. The role’s originator, Rita Moreno, earned a Tony Award for her near-legendary performance, but her successor attacks it with a tenacity and verve that is menacingly proprietary. Brazenly trumpeting her gifts while promoting her wretched act to anyone within earshot, Googie warns that “the band sometimes plays (the song) in a different key than I sing it” — a statement which could easily qualify as the understatement of the decade (and for anyone who ever longed to hear “I Could Have Danced All Night” performed to a disco beat — and with a heavy Puerto Rican accent — your moment has come). Googie loses a stiletto pump midway through her routine — long after having lost the melody — but she soldiers on, blissfully impervious to her own shortcomings. Trouper that she is, she recognizes that the show must go on. Unfortunately, it’s a show that seems to go on without much of a point whenever its demented nightingale heads offstage for a breather. In the midst of so many half-naked men, it’s a woman — albeit one frequently mistaken for a transvestite — who stands out.

Tweet

Labels: Ebb, Hammerstein, Kander, Musicals, Rodgers, Streisand, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, November 29, 2007

A pair to remember

By Edward Copeland

Admittedly, I've never seen the more dramatic examples of the Tracy-Hepburn pairings (I haven't heard good things), but I did finally catch up with 1957's Desk Set. While it's hardly in the league of Woman of the Year or Adam's Rib (or even Pat and Mike), it does go to show what great comic chemistry this couple had.

In a way, the plot of Desk Set almost seems timeless as Katharine Hepburn plays the head of a television network's research department and Spencer Tracy plays an outsider hired by the network to use his magical computer technology to serve the research function in less time and with fewer employees.

The age-old battle of man versus machine plays as timely today when corporations try to do more with less as it must have in the 1950s. Still, it's just an excuse to let Tracy and Hepburn play.

Some things do strain credulity (Kate was 50 when she this film was released with her playing a single executive, pining away for her infrequent dates with the ever-reliable Gig Young as her superior). On the whole though, Desk Set is watchable fluff.

A prime example of the Tracy-Hepburn magic comes during the scene depicted in the photo at the top of this post. Tracy's character invites Hepburn's to a lunch to ask her some questions, ostensibly about the way her department runs. Kate anticipates a trip to a nice restaurant, but what Spence has in mind is a pseudo-picnic on the cold, wind-blown roof of the network's skyscraper.

The questions aren't of the normal variety either: Lots of odd math problems. However, the actors turn this into a comic feast, literally, with their mouths stuffed with food most of the time. The entire setpiece turns out to be priceless.

Desk Set offers others like this and while it's certainly nowhere near their earlier comic efforts, it's still mostly a joy to watch. Tracy and Hepburn create a vivid pair of corporate eccentrics and their skills sell the whole package.

For added measure, the supporting cast includes the great Joan Blondell as one of Kate's single co-workers (and she was older than Hepburn!) and she brings just the right amount of sass and spice to the mix.

Tweet

Labels: 50s, Blondell, K. Hepburn, Tracy

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

Kids paint the darndest things

Most documentaries end up coming out with a specific point-of-view or a detached approach that just lets the viewer decide. With Amir Bar-Lev's My Kid Could Paint That, you see a documentary where the filmmaker is as uncertain of the truth as many viewers might be. It makes for quite a compelling piece of film and, in a way, one that is as abstract as the art at the center of its story.

For those unfamiliar with this documentary's tale, it concerns the explosion of popularity for an artist named Marla Olmstead, whose works one art expert says is worthy of hanging in the Met. Oh yeah: Marla was only 4 years old.

After a local gallery owner in her hometown of Binghamton, N.Y., displays her works, she becomes a sensation with a newspaper article that gets picked up by The New York Times, a followup piece in the Times and eventually a piece on 60 Minutes.

The TV report is where everything changes, as Charlie Rose questions whether the paintings truly were Marla's works or were part of a larger fraud being perpetrated on art collectors. It's at this point that My Kid Could Paint That really becomes interesting, as Bar-Lev begins to question the truth of the Olmsteads' story about their daughter as well.

The heart of the film though isn't so much about this particular child and her particular paintings as much about art in all its forms, specifically abstract, modern art such as by Jackson Pollock, which always have been greeted with skepticism.

As the New York Times' art critic Michael Kimmelman asks, what is truth and what is a lie when it comes to art? Does art have an obligation to explain itself? Would these paintings, if they'd been attributed to an adult, have garnered so much acclaim? Are collectors buying the story as much as the work itself?

If there is a sympathetic character to be found in this tale, it is Marla's mother, Laura, who seems relieved to let the phenomenon go away. If she were in on a scam, she's one helluva actress, but her feelings seem genuine when she asks what she's allowed to happen to her children.

At the same time, obvious villains in this story don't come easily either, though my vote goes to gallery owner Tony Brunelli, who admits on camera that he enjoyed the idea of making people who embrace abstract art look like fools since his own artistic bents are photorealistic. (Though I have to ask if he's telling the truth that the most he's ever sold one of his own paintings for is $100,000, would such a scam really have been worth his while?)

Marla's dad Mark also seems to be a willing co-conspirator, if such a conspiracy happened, and while many struggle hard to hang on to their belief that these works sprang solely from the brushstrokes of a child, it seems pretty clear to me that that isn't the truth. At one point, Marla tries to tell her dad that her little brother Zane painted one work all by himself as dad tries to ignore what she's saying. At another, Marla laughingly says while she's painting, "Help me out, dude" to her dad, and asks him if it's done or not.

While many worry about how this entire experience will affect the kids in years to come, Marla and her brother seem blissfully unaware of the things that are driving adults crazy. Ignorance may truly be bliss.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Documentary

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, November 26, 2007

Welcome back boys

By Edward Copeland

For more than a decade now, I've lived in a critical wilderness when it comes to the Coen brothers. I was a huge fan of the siblings from the moment I saw Blood Simple back in 1985, through the great fun of Raising Arizona and the exquisite Miller's Crossing. I liked Barton Fink a lot, though something of their style was starting to strike me as repetitive.

When Fargo came and seemingly the entire critical world ravished it with hosannas, I felt as if I stood alone thinking the movie was overrated and the Coens were stuck in a rut, a feeling that only grew over the course of their next films, so much so that I skipped offerings such as the ill-advised remake of The Ladykillers and Intolerable Cruelty. When No Country for Old Men started garnering raves, I was skeptical as I had been post-Hudsucker Proxy, partly as self-defense so as not to be disappointed. Now I've seen No Country for Old Men and no one is more delighted than I am to say that Joel, Ethan and I have met up again on the same path.

This isn't to say that some of the praise for No Country for Old Men isn't overselling the film's worth, but I think it's understandable since it plays like such a radical departure from the usual Coen outing. As Tommy Lee Jones' sheriff says at one point, "it's hard to take measure of something when you don't understand." Still, this film adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's novel isn't really hard to grasp, it's just removed from most of the brothers' recent output in its coldness, straight-forward nature and relative lack of snark.

In a way, the Coen brothers film that No Country most closely resembles is their very first effort, Blood Simple, with its Western noir feel and Texas setting. Unlike Simple's great showiness, No Country resists all impulses to call attention to itself. It's as if the Coens, tired of two decades as the high school class clowns of American filmmaking, have finally matured to middle age.

The other Coen film that No Country parallels, albeit slightly, is Fargo since it really has no lead but instead three characters whose paths intersect at times. In addition to Jones' sheriff, who seems like a more reticent version of the character he played in his underrated directing debut, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, there is Josh Brolin's trailer park denizen who stumbles upon the scene of a drug deal gone bad and makes off with a briefcase full of cash.

The third, and most vivid, member of this trio is Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a stoic killing machine with pasty skin and a Prince Valiant haircut, out to retrieve the money as well as slaughter anyone whose death meets his peculiar fancy.

What's most remarkable about the film to me is its pacing, which seems very deliberate yet delivers much momentum without ever feeling rushed. I also liked how it's a period piece, but one so subtle that unless you pay close attention, you might not realize it is set in 1980.

In fact, what No Country bubbles over with more than anything else is subtlety, not something I've come to expect from the Coens. The themes of what a tough country America can be and the futility of chasing things that have fallen far from your reach are there, but delivered with a velvet touch instead of a sledgehammer. The other thing that impressed me most is that really none of the characters are particularly dumb.

Sure, they make mistakes, sometime fatal ones, but the movie never mocks them and some of their ingenuity seems out of a script from MacGyver. Also, while this is a violent film, much of the bloodshed is only seen either in the aftermath or not at all.

The performances are great across the board, from Jones and Brolin to Kelly Macdonald as Brolin's wife and Garret Dillahunt (late of HBO's Deadwood and John from Cincinnati) as Jones' deputy as well as brief appearances from Woody Harrelson and Barry Corbin.

Still, No Country for Old Men belongs to Bardem, who has created a monster for the ages.

One criticism I heard from people leaving the theater when I left was frustration with the somewhat vague ending that denies the audience clear-cut payoffs. That didn't bother me, because it's all there if you pay attention and the Coens aren't rubbing anything in the audience's face as they've done in the past.

In a way, it somewhat resembles the reaction to the finale of The Sopranos, emphasizing what many of that HBO series' fans hit upon: the recurrence of the idea that some things you never see coming. I have to admit I didn't see this good a film coming from the Coens again, but I'm most grateful that it did.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Bardem, Coens, Deadwood, Harrelson, HBO, Josh Brolin, The Sopranos, Tommy Lee Jones

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, November 22, 2007

From the Vault: Double Impact

Told in the new Jean-Claude Van Damme film Double Impact, their tale is a simple story of stolen destinies and exacted revenge. Van Damme plays both Alex and Chad, twins separated at birth by the murder of their parents, who are raised in two completely different environments.

Alex, left at a Hong Kong orphanage, becomes a small-time hoodlum smuggling contraband. Chad, raised by his parents' bodyguard (Geoffrey Lewis), turns out to be a successful martial arts instructor in Los Angeles who lacks street smarts but dresses appropriately preppy. When Lewis discovers Alex's whereabouts, he takes Chad to Hong Kong so the three can avenge the parents' deaths and restore their claim to the investment over which they were killed.

Dual roles are a challenge to actors and Van Damme comes at the parts kicking. Most actors would go the conventional route of creating two distinct flesh-and-blood characters who happen to look alike, such as Jeremy Irons did in Dead Ringers. Van Damme takes a more deceptively simple route by dressing Alex and Chad differently and giving them their own props.

Chad seems perpetually trendy and has a neatly groomed haircut while Alex dresses in black with slicked-back hair which makes him resemble Steven Seagal, which I'm certain must be a clever satirical point about the other action star who seems positively shallow when compared to Jean-Claude.

Furthermore, Alex seldom lacks a cigar in his mouth and his manipulation of that prop borders on the magnificent. Van Damme plays both characters perfectly without any typical thespian tricks getting in the way.

The script does explain that Chad grew up in Paris to account for his accent, but it doesn't feel the need to account for Alex's. Why should it? Van Damme takes his cue from Kevin Costner and just reads the lines without allowing a "performance" to distract from the film itself.

The story and screenplay credits four individuals, including Van Damme, and it shows. It would have been difficult for one person to come up with such a perfect spoof of traditional action archetypes and sustain that level for nearly two full hours.

Every nuance appears from the poorly filmed and fake-looking fight scenes to the crusty mentor Geoffrey Lewis plays, who seems to resemble G. Gordon Liddy.

The fights are choreographed hysterically so that Alex finds it necessary to roll prior to each time he fires a shot and where Lewis magically knows where to be in every shoot-out.

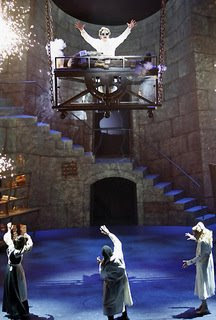

Even the climax proves a perfect action film parody with plenty of steam and pipes and the requisite "pits of hell" lighting that illustrates well the size of this film's budget.

Double Impact hits its target as a brilliant dissection of the martial arts/action cheapie genre. The film lacks a single serious moment and the people behind it couldn't have meant for it be taken at face value — could they?

Surely not.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Costner, Jeremy Irons

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

From the Vault: Casablanca

It's still the same old story, a fight for love and glory, a case of do or die, and after 50 years, Casablanca retains its place as the quintessential Hollywood movie. Released originally in November 1942, the prints of Casablanca have been refurbished and re-released in honor of the Oscar-winning best picture of 1943.

The influence of the film on American culture and filmmaking cannot be overstated. It wasn't a technical groundbreaker such as Citizen Kane or a stunning epic such as Gone With the Wind, it was a movie more apt to be discovered on late-night television, whose poster adorns many a college student's wall and whose dialogue is recognized by people of all ages.

There were the obvious homages, like Woody Allen's Play It Again, Sam, Neil Simon's Bogart-tribute The Cheap Detective and the bad Sydney Pollack-Robert Redford collaboration Havana, but there also were subtler tributes.

When Steven Spielberg traced Indiana Jones' route on a world map in Raiders of the Lost Ark, he took that from the opening of Casablanca. George Lucas copied the arrival of Major Strasser (Conrad Veidt) and his initial meeting with Capt. Renault (the incomparable Claude Rains) for Darth Vader's greeting of the Emperor in Return of the Jedi.

When Julie Hagerty became obsessed with the number 22 on the roulette wheel in Albert Brooks' Lost in America, it was because Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) rigged that number to allow the young couple to win on his gaming tables in Casablanca.

What should be remembered most about Michael Curtiz's film though are the wonderful cast and the sparkling dialogue by Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein and Howard Koch.

Bogart was at the top of his form as the smooth cynic "who sticks his neck out for nobody," but who suffers from a broken heart and a violent past.

Ingrid Bergman was stunningly beautiful as the woman who understandably left Bogart shattered. The cast was top-notch, from the waiters and bartenders at Rick's Cafe Americain to Peter Lorre as a "cut-rate parasite" and Sydney Greenstreet as the owner of the rival club, The Blue Parrot.

However, in my opinion, the film's real star was Claude Rains as Capt. Louis Renault. His role is like the other roles, only more so. A self-proclaimed corrupt official, Rains' Louis sparks scenes with his sly wit. He could have been a villain but in Rains' hands, you can't help but love him.

Then, there is Dooley Wilson's Sam, singing his heart out on the now-classic "As Time Goes By." Even the slightly hokey Paris flashbacks come off well.

Finally, there is possibly the most perfect ending of any Hollywood film. In the course of the film, a drunken Bogart lashes out at Bergman and tells her about stories with "wow endings." Curtiz's film delivers one of its own.

When things are looking hopeless in this plot, one character wishes for a miracle to which Rains replies, "The Germans have outlawed miracles." Fortunately, Hollywood used to be able to produce some miracles of its own and Casablanca was one of the greatest.

Tweet

Labels: 40s, Albert Brooks, Bogart, Curtiz, Ingrid Bergman, Lorre, Lucas, Movie Tributes, Neil Simon, Rains, Redford, Spielberg, Sydney Pollack, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, November 19, 2007

Oscar's rules for GLBT characters

This post was for the Queer Blog-a-Thon hosted at Queering the Apprentice, which apparently no longer exists. Be warned: the words below will contain spoilers for a lot of films, too many to mention, so don't read it and whine later.

The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences has been fairly generous in the past 20 or so years in nominating (and sometimes rewarding) actors and actresses who play gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgendered characters on screen. However, this does come with a price. Not to their careers, but in deciding whether or not the role gets nominated in the first place.

There seems to be only two types of gay roles that get deemed worthy of Oscar recognition: ones that are comicly broad or one where the gay character in question either ends up dead or alone. Look at just a couple of highly praised roles that got snubbed come Oscar time. Everyone thought Dennis Quaid was a lock for a nomination with his tortured married gay man in the 1950s in Far From Heaven, but he didn't make the cut. In the end of the film, his character has accepted his sexuality and found a boyfriend: no nomination for him.

Rupert Everett was a lot of fun as Julia Roberts' best gay friend in My Best Friend's Wedding, but his character was out, proud and presumably in a relationship. Strike him from your nominating ballot.

Now, here come the spoilers, as I look at all the performers who did get nominated or won an Oscar for playing a gay character. I'm only counting characters that are explicitly gay, not implied ones such as Clifton Webb in Laura For sake of simplicity, I'm going chronologically.

The first openly gay character that I can find with a nomination set one of the patterns: He's alone at the end.

Sarandon's character of Leon is already institutionalized (and wants nothing to do with Sonny) when we meet him. Sonny (Pacino) ends up alone and in prison.

The first instance (post Dog Day Afternoon) of Oscar nominating an openly gay character was for Coco's broad comic turn in this lesser Neil Simon outing.

Robert Preston in Victor, Victoria (both 1982)

Preston's great turn definitely belongs more in the broad comic category, though he might also be an exception since he is allowed to have a boyfriend by film's end. Lithgow, as the NFL player turned transsexual in Garp, might be an exception. He's alive at the end, but his role is mostly played for laughs and the film never provides him with a significant other.

Another possible exception, though the film makes it unclear if she's alone at the end, though she certainly looks guilt-stricken over possible involvement in her friend Karen's death.

Ding ding ding. We have a winner. While the movie was certainly a drama, Hurt does a lot of histrionic flouncing AND he ends up dead in the end, even after his straight cellmate (Raul Julia) gives him a mercy fuck.

It was five years before another gay character earned a nomination and Davison's character got the double whammy. First, he has to watch his lover die of AIDS, leaving him alone, and then he dies as well (and not even on screen).

Here's another example of a broad performance in a drama and while Jones' character lives in the end, it is complicated by the fact that he is portrayed as a villain (and with some over-the-top gay orgy scenes that only Oliver Stone could dream up). In contrast, Joe Pesci playing the less showy gay character who does get killed, didn't earn Academy notice.

First, Dil's lover gets killed during an IRA kidnapping and then when he/she falls for his captor, Fergus (Stephen Rea) gets sent to prison and Dil waits patiently, even though Fergus shows no intention of abandoning his heterosexuality.

Gay and dead takes home the prize again, though at least Hanks' portrayal wasn't a broad one, even if Denzel Washington gave the better lead role in the film.

I don't think Kinnear's character had a significant other by film's end, but I do remember he took a bad beating.

Here is an openly gay actor nominated for portraying a true-life openly gay director. Alas, James Whale dies in the end (as he did in real life) but the real travesty was that McKellen (and Nick Nolte and Edward Norton) lost to Roberto Benigni (Life Is Beautiful).

Bates was great as a take-no-prisoners political operative working on the campaign of a Bill Clinton-like candidate. Alas, her lesbian character had principles and ended up firing a gun into her head.

Swank won the first of her two Oscars for lead actress by playing the gender-confused Brandon Teena. It also was the first of two times that Swank made it to the winner's circle by getting beaten to death.

Based on a real person, Bardem's character has to fight problems in Cuba before getting to N.Y. for one of the longest death scenes (from AIDS) I've ever seen.

The same year that the Academy snubbed Dennis Quaid for his fine work in Far From Heaven, they nominated this awful performance by the usually fine Harris as an artist dying of AIDS.

If Virginia Woolf hadn't walked herself into the river, this nomination and win probably would have never happened.

In a way, her character here is similar to the one Quaid plays in Moore's other 2002 film. She's married, but unable to accept her sexuality. By the film's end, she appears to be alone, so she gets a pass while Quaid got snubbed. It may also explain one of the rare occasions where Meryl Streep didn't get an Oscar nomination since her lesbian character in The Hours had a lover in the end and doesn't die.

Another win based on a true story. Theron took the executed lesbian serial killer right up to the winner's circle.

This may be the true exception to the rule. Based on a real life character, the story didn't follow Truman Capote to his death and he did have a longtime companion. The closest this comes is denying him his crush on the executed killer.

Two nominated performances of gay character, so the Academy got to take one of each: Gyllenhaal's character ends up dead, Ledger's ends up alone.

I'm not sure where to place this performance of an in-process transsexual. She doesn't die in the end.

Tweet

Labels: Bardem, Capote, D. Quaid, Denzel, Hanks, J. Gyllenhaal, Julia Roberts, Julianne Moore, K. Bates, Lithgow, Neil Simon, Nicole Kidman, Oliver Stone, P.S. Hoffman, Pacino, Pesci, R. Preston, Tommy Lee Jones, Whale, William Hurt

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, November 16, 2007

Centennial Tributes: Burgess Meredith

By Edward Copeland

Not enough credit goes to our best character actors, actors who, more times than not, never fail, even if they seldom get near top billing. That's certainly the case with the late, great Burgess Meredith, who would have turned 100 today. He truly was a utility player: You could get the serious Burgess, the campy Burgess, the eccentrically fun Burgess or even the flat-out hammy Burgess, and he seldom failed at any of those. I wonder what he's most remembered for now, 10 years after his death. Is it his fantastic interpretation of The Penguin on the 1960s Batman TV series? Could it be Jack Lemmon's father in Grumpy Old Men? Is it Rocky Balboa's crotchety trainer in the first three Rocky movies? Meredith was all of these roles and so much more.

He made his film debut in 1936, six years after he made his debut on the Broadway stage in a production of Romeo and Juliet starring and directed by Eva Le Gallienne. He would return frequently to Broadway, often as a director (including a Tony nomination as director of a play for Ulysses in Nighttown in 1974.

Still, film and TV were where Meredith would leave his strongest impressions and he did that just three years into his career in the role of George in Lewis Milestone's film adaptation of John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men. Two years later, Meredith gave what is, for me, my favorite performance, depicted in the photo at the top of this post. In Ernst Lubitsch's That Uncertain Feeling Meredith gave a delightfully odd performance as concert pianist Alexander Sebastian, who manages to break up the marriage of the Bakers (Melvyn Douglas, Merle Oberon). The scene that introduces him, set in the lobby of a psychiatrist's office, is priceless even when standing alone. Sebastian describes himself as an "individualist" and insists that "I hate humankind and humankind hates me." The film itself is by far a lesser Lubitsch, but Meredith's performance makes the whole enterprise worthwhile.

He took on the role of real-life WWII journalist Ernie Pyle in 1945's The Story of G.I. Joe, which earned Robert Mitchum his only Oscar nomination. He continued to work frequently in film, including three films with Otto Preminger: 1962's Advise and Consent, 1963's The Cardinal and 1965's In Harm's Way. In the latter two, he mostly lent solid support, but Advise and Consent gave Meredith one of his very best screen roles as an extremely nervous witness in a congressional hearing.

Of course, 1966 brought him the role that first made me aware of him (and endeared me to the actor as well): The Penguin on TV's Batman. His, as just about everyone on that show, was a comic tour de force and I still prefer him to a Danny DeVito version of the role. After the TV show ended, he still made forays into film, including achieving the rare goal of winning two supporting actor nominations in a row. The first came for 1975's The Day of the Locust, an adaptation of Nathanael West's novella, which I saw a young child, dragging my parents to it because I knew The Penguin was in it. I haven't seen the film in more than 30 years, but I can still remember his character cackling from a coffin. The following year, he got his second Oscar nomination for another of his best-known turns: Rocky Balboa's trainer Mickey in the original Rocky, a role he repeated in the first two sequels. Meredith managed to make the crusty old dude fresh without being corny.

I also enjoyed him as Goldie Hawn's karate-fighting landlord in 1978's Foul Play. His melee with Rachel Roberts still makes me laugh. He also appeared as one of the many stars in 1981's Clash of the Titans. Late in his career, he enjoyed another resurgence as Lemmon's foul-mouthed dad in Grumpy Old Men and its sequel.

Still, aside from all these other memorable roles, I have a feeling he might get a big dose of fond remembrance for his appearances on Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone, on which he guest-starred four times, including in what, for me at least, was that series' finest episode: 1959's "Time Enough at Last." Playing a geeky bookworm who repeatedly sneaks away from his duties at a bank to read in the vault, his choice of hiding place ends up making him the sole survivor of a nuclear attack. The man is giddy with excitement: No one is left to mock him and he has all the time and all the books in the world at his disposal, until the script gives him one of the series' most cruel twists.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Burgess Meredith, DeVito, Lemmon, Lubitsch, Milestone, Mitchum, Oscars, Preminger, Television, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Last call at the Bada Bing

Having gone through the last Sopranos DVD set I had to own and then re-watching the final nine episodes, I thought it was time for reflection upon the final shows of one of the greatest TV series of all times. Needless to say, there are spoilers galore, but if you are behind by this point, you are really on your own anyway.

What struck me the most upon re-watching the final nine was how many of those episodes were almost standalones. Sure, storylines were forwarded, but they weren't the main focus. The first episode, "Soprano Home Movies," seemed to be judged harshly by some even when it first aired, but for me it only grows better upon later viewings. It's as if Edward Albee had decided to pen a Sopranos episode and as, what is essentially a four-character play, it's riveting.

The second outing, "Stage 5," was even better as we watch the sad final days of Johnny Sack (Vincent Curatola). What's even clearer upon another viewing is the entire focus on image versus reality for everyone. Johnny wants to know how he'll be remembered while Tony wonders if that lead character in Cleaver is how the world will see him (though it takes Carmela, prompted by Rosalie, for the self-absorbed Tony to even spot the parallels.) On the New York side, Phil is more bitter than ever and his brief decision to slow down and let others handle the business is thrown out the window by his perception that no one is living up to his standards.

"Remember When" is another great outing, though it falls off a bit from the first two episodes, mainly because the idea that Tony was going to off Paulie because he annoyed him during their Florida exile never rings true. Fortunately, the bulk of the episode gives Dominic Chianese one last episode for him to shine as Uncle Junior, hospitalized and trying to relive his glory days with poker games and a young apprentice. It is a true shame that Chianese didn't get a last Emmy nomination (or a win). Uncle Junior is one of the many great all-time characters David Chase introduced us to and he deserved more recognition.

The first real pothole (and the only one really) that the series hit in its final nine was "Chasing It." Tony's sudden gambling problem seemed really forced and the ending with Hesh and his girlfriend was rather odd, making it understandable why so many questioned whether Tony had something to do with her death when it still seemed fairly clear that he didn't. As if one weak storyline weren't enough, "Chasing It" also tosses in the plight of the troubled son of the late Vito Spatafore, making the entire episode seem more like it should be called "Stretching It" than "Chasing It."

The next episode though, "Walk Like a Man," more than makes up for it. When I first watched the final nine, I thought "The Blue Comet" might have been the best of the final episodes but seeing them again, it's clear that "Walk Like a Man" truly was the standout, focusing on Christopher's struggles with sobriety and the distrust of his mob associates. This may have been Michael Imperioli's finest hour in the entire series. It also is the episode in which Robert Iler's A.J. truly becomes the focus of the final run of episodes. It's amazing what a fine actor Iler turned into, starting as the chubby-cheeked pre-teen, to a young twentysomething with real acting chops. I hope his career doesn't stop here and he'll find other material at least close to the level he received here. He also provides a commentary track on one of the episodes of the DVD and admits he never really watched the series. He also notes how for years people would say what a great learning experience it must be to work with magnificent talents such as James Gandolfini and Edie Falco, but he didn't really appreciate how great they were until the last couple years when he really got material that made him bring his acting up to their level.

Of course, "Walk Like a Man" perfectly set up "Kennedy and Heidi" in which Christopher went out in a way I can't imagine many anticipated. It also was an exemplary example of showing Tony trying to justify what he does and get tacit approval from others, even when they don't know what he's really talking about.

"The Second Coming" continued the hot streak and was another great showcase for Iler as well as for Edie Falco, finally tiring of the ways the men in her life use depression. Falco seemed underused for most of the last nine episodes, but I think this is the one that allowed her to shine the most.

Then came "The Blue Comet," which not only contained one of the best-directed sequences in the history of the series, but finally showed Dr. Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) wising up about her wiseguy and giving Tony the heave-ho. It's a shame that Bracco, finally placed in supporting where she belonged, couldn't overcome the gauntlet of Grey's Anatomy actresses to win her overdue Emmy.

Of course, this leads us to the most talked-about episode (or at least ending): "Made in America." Most of the hour is spent tying up various loose ends (and giving us our final tastes of the bent comic brilliance of Tony Sirico) until we get to that final scene in the diner. Upon first viewing, I was annoyed like many viewers (I didn't think my TV had gone out: I knew what Chase was up to), not because I sought finality or a bloodbath, but because I feared its lack of resolution left open the possibility of some movie version to cash in years down the road. In subsequent airings, the cut to black really began to work for me.

However, what I gained, I've also lost. I realized that when you watch that final scene later, all the suspense that Chase built and viewers experienced the first time evaporates when you know that literally nothing is going to happen. Of course, theories abound, reading symbolism into everything about how it's all supposed to represent Tony's death and David Chase seems to have gone both ways in interviews. I think the true answer may lie in the commentary by Steven Van Zandt (Silvio) and Arthur Nascarella (Carlo) on "The Blue Comet" episode. The actors said that the fade to black was right there in the first table read of the episode. When it was done, Gandolfini asked Chase, "You're really going to end it like that?" and Chase replied that he didn't want to have an ending that said crime pays or one that says it doesn't.

As for the DVD itself, the commentaries (done by Steve Schirripa, Chianese, Iler and the previously mentioned one with Van Zandt and Nascarella) don't offer that much except for the tidbits from the Van Zandt and Nascarella one (I didn't know Nascarella used to be a NY cop).

The other extras include the hilarious Making of Cleaver piece that ran on HBO and another short about David Chase and the music of the show, which I'd never seen but was quite interesting. Still, it's the show itself that is the selling point here. I think it might have gone on too long at times, but when The Sopranos was firing on all cylinders, there was nothing better.

Tweet

Labels: Albee, David Chase, Gandolfini, HBO, Television, The Sopranos

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, November 12, 2007

Samuel Fuller and the Temple of Doom

By Edward Copeland

In many ways, Samuel Fuller was the founding father of the independent film in America and that truly shows in one of his earliest efforts, 1951's The Steel Helmet, a Korean War story told while that conflict still raged. Using spare sets and some so-so acting, Fuller certainly spun a silk purse from a sow's ear.

What's remarkable is how much Fuller covers with so little resources and such a short running time (less than 90 minutes). The Steel Helmet begins with one of the best opening sequences I've ever seen. As the opening credits unfurl, the camera stays focused on a soldier's helmet. You'd probably be right to think it's just emblematic of the title, but as the credits end, that helmet raises and you meet the eyes of gruff Sgt. Zack (Gene Evans), slowly looking around before struggling to free himself from the ties that bind him. Soon, he gets an unlikely ally to help him: A Korean orphan he names Short Round (William Chun), who immediately corrects the soldier when he dares to call the kid a gook. Racism underlies the entire movie, but it's never preachy which makes it all the more powerful.

Soon, the pair encounter an African-American medic (James Edwards) before hooking up with an entire brigade, searching for a Buddhist temple to serve as an outpost. What unfolds after that is more the stuff of psychological drama than that of standard war films, until its final, tense climax. Still, it's the relationships between the characters as they remained holed up in that temple that really gives Fuller's film its power. It's pretty incredible that this was made while the Korean War still was going on, though it's clear that World War II is as much the subject as Korea, much in the same way Robert Altman's MASH wasn't about Korea but Vietnam. In fact, instead of "The End" closing The Steel Helmet, instead Fuller fills the screen with words to the effect that this is a story that has no end. Fuller's reputation has grown over the years and deservedly so. This taut example of excellent filmmaking more than makes the case that you don't need a lot of resources to produce truly remarkable film.

Tweet

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, November 11, 2007

Weapon of mass distraction

By Edward Copeland

Seventy-five years ago today, Jean Renoir's comedy Boudu Saved From Drowning opened in France, even though it didn't land on American shores until 40 years ago, in early 1967. While it doesn't come close to Renoir's greatest works, it remains an entertaining diversion, thanks mainly to the inspired and, at times, downright odd performance by Michel Simon in the title role.

The story may seem familiar to many Americans, since Paul Mazursky remade it in 1986 as Down and Out in Beverly Hills with Nick Nolte playing the Simon role. Some things were better in the remake, but the original Renoir remains the film that holds up best on later viewings, with one notable exception: Mike the dog as Matisse was one of the most talented canines to cross the silver screen and was robbed of an Oscar nomination. What really separates Renoir's original from Mazursky's remake is that Renoir doesn't attempt for his well-off characters to learn anything from Boudu.

As in many of Renoir's film, Boudu concerns itself with class as an upper middle-class bookseller named Lestingois (Charles Granval) commits the title act, bringing the suicidal bum into his home in attempt to help him (and reap some glory in the process). Whereas Down and Out in Beverly Hills sets its rescuers at an even higher social level, it uses the Nolte character for them to give in to their desires and learn things. In contrast, Simon's Boudu is all id. He doesn't want to teach, he barely wants to leech, but he does enjoy filling his needs of food and attempting some carnal exploring among the women of the house. Of course, it helps that Boudu isn't grateful for having his life saved, asking why they did it: He viewed suicide as a way to save his life. Simon's performance is a wonder of someone out of control, flinging nightshirts away as too small, spitting out wine, preferring lard to butter, alienating the woman of the house by using her silk sheets to shine his shoes. When Lestingois' wife Emma (Marcelle Hainia) complains about the sheets, her husband is too preoccupied because he's discovered that Boudu has spit on a book by Balzac. "One should only come to the aid of equals," the bookseller sighs.

Of course, Boudu also interferes in the late-night liaisons Lestingois conducts with his maid (Severine Lerczinska), before Boudu cleans himself up enough to woo the woman for himself. Renoir definitely set up themes he would explore better in later films, but he keeps the pace moving languidly, which would seem at odds with what is basically a farce, but he never loses control. He even shows some interesting directorial touches, such as a spinning shot around a boat late in the film, when Boudu is embarking on marriage. Still, it's Michel Simon's performance that makes Boudu Saved From Drowning stand the test of time. His energy is amazing, what he does with his eyes is nearly as acrobatically impressive as when he's rolling around a table or engaging in an impromptu headstand.

Tweet

Labels: 30s, Foreign, Mazursky, Nolte, Renoir

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, November 10, 2007

Norman Mailer (1923-2007)

Of course, Mailer was far more than just a mere novelist. He changed the rules of nonfiction as well with his riveting account of Gary Gilmore's life, crimes and execution in The Executioner's Song, which won him the second of his two Pulitzer Prizes (the first came for Armies of the Night, an account of the 1968 Democratic convention). He blended his own career with fiction in the great Advertisements for Myself. He wrote screenplays of his novels and even tried his hand at directing, including the adaptation of his own novel Tough Guys Don't Dance. He even did some acting, most notably as the architect Stanford White in Milos Forman's Ragtime. According to IMDb, his last acting credit was as Harry Houdini in 1999's Cremaster 2. He helped to found The Village Voice. Of course, he also was a figure of great controversy, stemming from the stabbing of one of his wives and his mentorship of prisoner turned writer Jack Abbott, who promptly stabbed someone to death upon his release to a halfway house.

Though he made his name with a great World War II novel, The Naked and the Dead, he was often an antiwar figure, writing a book called Why Are We in Vietnam? and then turning expectations on their heads since the book depicted a bear hunt and didn't mention Vietnam once outside the title. During the current quagmire in Iraq, he published a more straight-forward book asking Why Are We at War?

He also was incredibly prolific, releasing The Castle in the Forest, which depicted agents of Satan grooming Hitler for his later evil deeds, earlier this year. It seems appropriate that a career that began with World War II would finish with an imaginative biography of that conflict's architect.

RIP Mr. Mailer.

Tweet

Labels: Books, Fiction, Mailer, Nonfiction, Obituary, Roth

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, November 09, 2007

The Devil's Reject

Quentin Tarantino can teach Sidney Lumet a thing or two about directing. And yes, my subject and object are in the proper places in that sentence. For better and worse, the short, meteoric rise of QT ushered in the still-active era of movies being told out of sequence, or in multiple and parallel flashbacks, for no reason whatsoever. Tarantino usually is able to pull it off because his direction embraces the fractured narrative, builds upon it and uses it to his full advantage. It's as if the film knows the flashbacks are coming or its sequence is out of order, and it adjusts accordingly without breaking its hold on the viewer. It doesn't announce FLASHBACK in giant capital letters. That's the lesson Sidney Lumet could learn from QT, because in Before The Devil Knows You're Dead, whenever the amateurish screenplay decides to go backward, Lumet announces it with incredibly annoying Pokemon-style screen flashing. It tosses the viewer right out of the movie.

Sondheim wrote "you gotta have a gimmick" and while that always works for strippers, it doesn't always work for film. Lumet builds tension so carefully in some scenes that the sudden announcement of flashbacks let all the air out of the balloon. Compare this to his devastating use of flashbacks in The Pawnbroker. There is absolutely no reason for the story to be told in this fashion, outside of sheer laziness and the screenwriter's knowledge that his script, if told straight, would have been no different than 8,000 other scripts with this same story. Yet Lumet's direction is so good at times that I felt he could have made this work without the gimmicks. The screenplay would still be just as derivative and unbelievable, but we would have been too busy being strangled by suspense to notice. This film just doesn't build the way it should have. It stops and starts like a traffic light-ridden NASCAR race. The herky-jerky back and forth gives far too much time to contemplate the numerous questions that derail the film's hold on the viewer.

In the screenplay chapter of his must-read book, Making Movies, Lumet writes:

"In a well made drama, I want to feel: 'Of course — that's where it was heading all along.' And yet the inevitability mustn't eliminate surprise. There's not much point in spending two hours on something that became clear in the first five minutes. Inevitability doesn't mean predictability. The script must still keep you off balance, keep you surprised, entertained, involved, and yet, when the denouement is reached, still give you the sense that the story had to turn out that way."

This is a very telling paragraph from Lumet. Is this film's construction a blatant attempt to stave off predictability without losing inevitability? And is this the reason why so many movies have flirted with the "off-balance" device of the non-linear gimmick? I really don't see much difference: if it's inevitable, then you can predict it's going to happen. This isn't as bad an idea as slowing down and hacking up your movie until the viewer can meditate on how illogical the story is.

Andy (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is the financially strapped eldest son of Charles (Albert Finney) and Nanette (Rosemary Harris). Between his drug addiction and his golddigger trophy wife, Gina (Marisa Tomei), Andy's wallet is screaming for help. To silence the noise, Andy has also been stealing money from payroll. Andy's younger brother Hank (Ethan Hawke) has money problems of his own: he can't pay his child support and his angry ex-wife Martha (Amy Ryan) is threatening him with court action. When he can't pay for his daughter's trip to The Lion King, he allows himself to be taken in by Andy's plan to help them both achieve hakuna matata. They decide to rob their Mom and Pop's Mom and Pop Jewelry Store — or rather, Andy decides Hank should do it — so that they can get quick cash and their parents can collect the insurance money that will result from the robbery. "It's a victimless crime," Andy says, using that bullying, manipulative manner we older brothers employ so well.

Of course, the robbery goes awry, and the primary reason for this is that Andy is, to use the film's love of the f-word, a fucking idiot. Hank's an idiot as well, but Andy knows not only this fact but also how wimpy Hank is in general. He assigns Hank the job, telling him to use a fake gun, and Hank instead gets a more hardened criminal (Brian F. O'Byrne from Frozen) to pull the job. Suffice it to say, the crime's not victimless, and O'Byrne winds up as dead as the victim he shoots in the heist.

As the brothers' world comes tumbling down, they make one inevitable mistake after another. They have to deal with Hank's ineptitude and Andy's horse addiction, their father's compulsive desire to find out who robbed his store and caused the carnage, the secrets that threaten to tear their fraternal love apart, and the women who drive them to do and say the darndest things. It sounds compelling, but the film's construction is far too distracting to be effective. And the questions that arise just nag at the viewer in the dark. Are these guys really in that much trouble that they need to resort to a jewelry heist? Why not Andy instead of wishy-washy Hank? How did Andy suddenly morph from Pillsbury Yuppie to Chuck Bronson? Why would Hank rent a car, effectively creating a paper trail, to do a robbery? If you have that much dope and dough in your house, wouldn't you have something besides a punk-ass revolver? Wouldn't an autopsy show that you smothered someone to death? Why steal from your job's payroll box when you know you're being audited? Why didn't the job call the cops on Andy? I could go on and on.

A film such as Before the Devil Knows You're Dead needs the kind of suspension of disbelief continuity of a film like To Catch a Thief or the film I wish this movie could have been: Sam Raimi's A Simple Plan. On occasion, Lumet reaches for the greatness he is known for, which makes the film's overall failure even more frustrating. Watch how he visually constructs an outdoor scene between Hoffman and Finney. Just the placement of the characters alone speaks volumes, making the stilted dialogue that pollutes the scene completely unnecessary. Observe how he visually plays out the scenes that depict Hank's criminal seduction by Andy. The robbery itself has incredible tension and an almost existential visual quality; it's as mean and lean as the rest of the film thinks it is.

Lumet's biggest failures usually stem from a lousy script or miscast performers (I'm looking at you, Miss Ross, in The Wiz). Before the Devil Knows You're Dead has both. Until his last reel gunplay, which does not work at all, Hoffman is a credibly smarmy creature with daddy issues and a wife he (correctly) thinks is out of his league. Ethan Hawke is so woefully miscast that it's painful to watch him. Albert Finney is wasted, but Rosemary Harris is interesting and far more credible with a gun than her cinematic son. Michael Shannon leaves an impressive mark on his limited screen time, as does Amy Ryan, and O'Byrne brings an expert's menace to his sacrificial role that can be used as a measuring stick for the brothers' amateur night at the criminal Apollo.

Marisa Tomei's character is one note and should have been accompanied by Whodini's "I'm a Ho" every time she appeared on the screen. Her sole purpose in the film is to show the naked body far too many critics are panting over, as if they've never seen tits and ass before. These are the same critics who have the nerve to be offended by the sex scene between her and Hoffman that opens the film, as if his far-from perfect (yet oddly film critic-like) body ruins their Tomei spank-bank entry and offends their sensibilities. I saw it as a harbringer of the film's dysfunction: it's superbly shot and visually arresting, but the content of the scene itself is not worth watching. Interestingly enough, it's the one stand alone scene in the picture (i.e., we don't know where it fits in with the rest of the timeline, short of assuming it comes before the film's story). It also tells us everything we need to know about the characters without saying a word.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Amy Ryan, Finney, Hawke, Lumet, Michael Shannon, P.S. Hoffman, Raimi, Sondheim, Tarantino, Tomei

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, November 07, 2007

It's Alive...If Not Exactly Kicking

By Josh R

A gathering mob is gearing up to march on Frankenstein’s castle, for the purpose of dispensing bloody justice. Transylvanian peasants bearing torches and pitchforks? Not quite — these vigilantes hail from the village of Manhattan, and are consequently more likely to be seen sporting fashions from Barney’s Fifth Avenue than dirndls and lederhosen. They’re the New York theater critics, and Mel Brooks, be warned — the head they’re coming for is yours.

Following up a monster success is the trickiest proposition on Broadway, and filmdom’s favorite mad scientist and his crack team of specialists — which includes director-choreographer Susan Stroman and bookwriter Thomas Meehan — find themselves faced with the toughest act to follow since Lerner and Loewe ignited The Great White Way with their tale of a cockney flower girl being molded into a fairy-tale princess. The team responsible for My Fair Lady followed that mammoth 1956 hit with the much-maligned Camelot — a worthy if less-than-sparkling entry that wound up on the receiving end of a critical tongue-lashing when it made its Broadway bow four years later. Negative comparisons to a previous success are inevitable when the bar has been set ridiculously high, and any player who has hit a home run in the first inning is likely to be accused of underachieving at their next turn at bat (check out the reviews for Alice Sebold’s latest for evidence of how quickly the critics can turn on their darlings).

Which brings us to Young Frankenstein, a show that has borne the weight of expectations about as lightly as a donkey carrying an elephant on its back. The 2001 musical adaptation of Brooks’ cult classic The Producers was greeted with the kind of enthusiasm Catholics usually reserve for a visit from the pope — if not the return of the Messiah, bringing with him his apostles, the cure for all diseases and The Fab Four, reunited to record a sequel to The White Album (Paul and Ringo aren't dead yet, but you get the drift). Indeed, critics all but exhausted their catalog of superlatives in their attempts to encapsulate its genius — the cheering section was so loud it practically blew out the eardrums of anyone within arm’s reach of a newspaper kiosk.

Young Frankenstein marks Brooks’ second attempt at adapting one of his cinematic properties into a Broadway musical, and from the minute he announced his intentions to do so, the deck has been stacked against him. Regardless of what the finished product may have turned out to be — and I’ll arrive at that presently — it is going to be compared unfavorably to its predecessor; sight unseen, that was always going to be the case. The Magnificent Ambersons had the bad fortune to come on the heels of Citizen Kane, and was dismissed as “a lesser effort” even by the critics who praised it — such is the nature of the beast.

It must be duly reported that Young Frankenstein, which opens on Nov. 8 at The Hilton Theatre, invites no such parallel — Orson Welles followed up his 1941 masterpiece with another, albeit lesser masterpiece. Mr. Brooks, Ms. Stroman and Mr. Meehan have followed up their gold-plated achievement with something that is mostly amusing, largely derivative and pretty solidly OK. While there is nothing about the show to cause any offense to the film’s vast army of fans, or to prevent audiences with cash to burn from having a perfectly agreeable experience, nor can Brooks & Co. be credited with having created anything for the ages.

Going over the plot of Young Frankenstein would constitute the ultimate exercise in redundancy, as it is doubtful that anyone reading this is unfamiliar with the film on which it is based — or, in some cases, would have any trouble reciting it line-for-line. The stage version is incredibly (and often slavishly) faithful to the original film, which is essentially a farcical recapitulation of Hollywood’s bowdlerized version of the Frankenstein tale — it owes more to James Whale’s 1931 film adaptation, and its even loopier sequel, than it does to anything that the morbid Victorian Mary Shelley ever cranked out. Jokes have been added, sequences have been streamlined while others have been padded out, but the alterations don’t take the material in a different direction; this is your father’s Young Frankenstein, preserved in all its original silly splendor. All of the film’s most cherished bits of comic business — from the monster’s slapstick encounter with a blind hermit to the sublime absurdity of “Puttin' on the Ritz” — are present and accounted for, as is most of the original dialogue. Nothing is quite as funny as it was in the context of the film, but the laughs are still there, and for the most part, they still work. As a musical adaptation, Young Frankenstein translates more smoothly than expected — although not as seamlessly as The Producers, which had an actual show business theme and milieu to make use of. The wittily conceived musical numbers are interpolated with the content of the screenplay in ways that seem natural at times and awkward at others — for every song that seems like a logical extension of the original material, there’s an elaborate production number that seems superfluous. The songs, while largely undistinguished, are tuneful and amusing enough, even if the musical highlight remains “Puttin' on the Ritz,” which was written by Irving Berlin in 1929. All in all, while not perfect, the show that’s rattling its chains on the stage of the cavernous Hilton Theatre is basically up to snuff.

Which is not to say that something — more than one thing, actually — doesn’t get lost in the shuffle. Much of the appeal of the 1974 film came from manner in which it paid winking homage to 1930s Universal horror features, creating a look and feel in keeping with the tradition of Whale’s creepy classic and its progeny; on a stage as opposed to the screen, and in full color as opposed to black & white, the effect can't really be duplicated. The scenic design, while nothing if not elaborate, suggests the Haunted Mansion at Disney World more than Hollywood’s ghoulishly baroque take on middle-European villages and castles — similarly, the energetic chorus seems like a bunch of smiling, high-leaping refugees from an Oktoberfest-theme amusement park. As a result, what seemed naughty, clever and rude about the film version is, in the present context, rather cute. Now, I for one have an amazingly high tolerance level for cute — I can ingest large quantities of whipped cream without gagging on it (I had fun at Legally Blonde, for Chrissakes), and I can even stomach a heaping spoonful of the warm fuzzies (somehow I made it through all seven seasons of Gilmore Girls), but for a show that is striving to be crude, dirty fun with streak of zaniness, cute doesn’t go very far toward achieving the desired effect. Even though much of Brooks’ humor is rooted in gleefully bad taste, this Young Frankenstein often winds up feeling like a lavishly produced work of children’s theater with R-rated jokes.

Nor can the cast, as talented and resourceful as they are, really compete with the memory of their cinematic forebearers (although one comes surprisingly close). That notwithstanding, every principal player more than justifies his or presence on the bill — with the exception of the leading man, who labors mightily to put his own stamp on the role but whose energies seem largely misdirected.

That’s a nice way of saying that the casting of Roger Bart in the central role of Dr. Friedrich Frankenstein (pronounced Fronck-en-steen, if you please) represents something of a misfire. With his withered lips and anxious features, Bart is a born character actor whose deliciously sour charms have been put to wondrous good use in roles that require an element of sly superciliousness. This is not to say that he isn’t leading man material — rather that, for the purposes of what Brooks has in mind, he does not come ideally equipped for the assignment. On film, Gene Wilder used his wonderfully woebegone milquetoast quality as the set-up for a great punchline; the soft-spoken, put-upon schlemiel attains the wild-eyed, manic intensity of a raving lunatic when visions of monsters start dancing in his head — the transformation from colorless nebbish to shrieking loony-bird was as improbable as it was hysterical. Bart isn’t physically or vocally equipped to make a similar transition — everything about him is too sharp, too brittle, too overtly flamboyant, to start out small and then get bigger (it would be like directing Paul Lynde to imitate Charles Grodin). As a result, the manic intensity is there from the outset, leaving the actor with nowhere to go — this doctor seems less like someone inadvertently stumbling onto his own madness than one who’s been wearing it as a badge of honor from the very beginning. Gene Wilder got his laughs in the early stages of the film by speaking in the abashed tones of one who functions in a perpetual state of queasy uncertainty; Bart gets his by upping the volume and making faces.

If the man leading the charge comes up a bit lame, the supporting cast makes up some of the stagger. In the past, Sutton Foster’s technical proficiency as a singer and dancer has occasionally had the effect of making her seem a bit mechanical (as in: wind her up and she does theater). The role of Inga, the good doctor’s cheerfully oversexed laboratory assistant, allows her to loosen up and channel her inner dingaling, at least in the show’s early going — with her candy-colored dirndl and Marie Osmond grin, she suggests nothing so much as Gretel after having gorged herself on the witch’s gingerbread shingles and gone goofy from the sugar rush. She takes full advantage of the polka-inflected “Roll, Roll, Roll in the Hay,” bouncing happily around a rickety cart while delivering a master class in yodeling — she’s like a singing marionette in a glockenspiel that’s popped its springs and gone haywire. If the actress doesn’t manage to strike the same note of giddy abandon in the remainder of her scenes, it’s because her character becomes something of an afterthought — and her second act seduction number, “Listen to Your Heart,” is played a bit too earnestly to make much of an impression. The ever-dependable Andrea Martin scrunches up her features into an expression of constipated discomfort as the morose housekeeper, Frau Blucher — the very mention of whose name is enough to send listeners of the equine variety into fits of apoplexy. Dragging a chair across the floor with mincing steps, then straddling it like a chorine at the Kit Kat Club, she clowns her way decadently through the Weill-esque “He Vas My Boyfriend,” detailing the humiliation and abuse she suffered at the hands of her deceased paramour (naturally, while professing her love for every disgusting, degrading minute of it). She comes much closer to suggesting the stylized delivery of Lotte Lenya than Donna Murphy did in LoveMusik, while parodying it to wonderfully hilarious effect. Megan Mullally, as the doctor’s frigid fiancée who is brought to the threshold of ecstasy after a tumble with Ol’ Zipperneck, enjoys herself thoroughly with the extended dirty joke of “Deep Love” — a romantic ballad extolling the virtues of the monster’s considerable, ahem, proportions. While I found the actress a bit much to take during her decadelong stint as Will & Grace's booze-swilling socialite, for the purposes of this show she lowers her voice, maintains her shtick level at a nongrating setting and fits right in as the third member of the show’s trio of female clowns. If none reach the delirious heights of Cloris Leachman, Madeline Kahn and Teri Garr, they all know exactly how to get their laughs — and moreover, how to milk them.

Nor are the male members of the supporting cast in any danger of fading into the background. With his green facepaint and bulky frame, Shuler Hensley suggests an unlikely hybrid of Boris Karloff and The Incredible Hulk. As The Monster, he is a more visually menacing presence than Peter Boyle was, which is fortunately not so scary that he ceases to be funny. His tap-dancing solo in “Puttin' on the Ritz,” which wittily pits him opposite his own, attention-seizing shadow, constitutes the show’s comedic highpoint, and he gets a well-earned laugh at the end as well — even if you’ve heard Hensley sing before, after an evening of grunts and growls, the unveiling of his soaring operatic baritone comes as a deliciously funny shock. The doughy-featured Fred Applegate has a rather nonspecific quality as a performer, which allows him to double in two wildly different roles; while his wooden-limbed Inspector Kemp lacks the scenery-chewing officiousness of Kenneth Mars’ indelible screen creation, he more than makes up for it with his wistful blind hermit, who adopts an Al Jolson-like posture — working the jazz hands on bended knee — while praying to the heavens to “Please Send Me Someone.”

Standing head and shoulders above them all is the diminutive Christopher Fitzgerald, who minces and mugs his way through the role of Igor as if the fate of Western Civilization depended upon it. While perhaps the most unheralded member of the star-studded cast, this infinitely resourceful comic imp comes the closest of anyone to capturing the frenetic spirit of the original film, and is the evening’s unequivocal standout. Fitzgerald is a whirling dervish of energy, and even when relegated to the sidelines, his comic inventiveness never flags — he attacks the role with such unbridled enthusiasm that he practically flies through it. Marty Feldman, the original Igor, had a pointy chin and peepers the size of hard-boiled eggs, which he used to deliciously comic effect — Fitzgerald, while possessed of a more circumspect set of features, has an improbably ridiculous array of facial expressions that not only conjure up fond memories of the role’s originator, but give him the hyper-animated quality of a rubbery-faced cartoon character brought to three-dimensional life.

The actor, who is a true find, is by far the best thing about a show that seems to have been predestined to settle for second best. Brooks and his cohorts labor mightily to match the standard of their previous collaboration, and to a large extent, the strain shows; there are many moments — say, for example, when a song's lyrics include something on the order of “There is nothing like a brain” — when you can catch more than a slight whiff of desperation in the air. As for the most pressing question — is the show worth giving up next month’s rent in order to see (orchestra seats go at an obscene $450 a pop) — as your physician, I’d advise against it. Die-hard Brooks fans won’t really get anything they couldn’t get from popping in the DVD for the umpteenth time, and musical theater buffs should hold out for discount tickets; frankly, even if Dr. Brooks had re-animated the dead corpse of Ethel Merman for an encore performance of Gypsy, I’d have to swallow hard before shelling out $450 for the privilege of seeing her in action. The Producers was a once-in-a-lifetime phenomenon — Young Frankenstein, while a perfectly enjoyable light diversion, doesn’t really distinguish itself as anything beyond that. In its last outing, Team Brooks served up chocolate soufflé with a raspberry filling, drenched in rum sauce. This time, the result, while tasty, feels more like leftover Halloween candy — easily digested, and just as easily forgotten.

Tweet

Labels: Grodin, Karloff, Mel Brooks, Musicals, Television, Theater, Welles, Whale

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, November 06, 2007

From the Vault: Lawrence of Arabia

Following the paths of Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, Lawrence of Arabia has marched back onto movie screens. Unlike those classic 1939 films which were restored and re-released to commemorate their 50th anniversaries, thanks for the meticulous work on Lawrence of Arabia goes to some of Hollywood's best-known modern directors.

Names such as Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese helped secure the funding to restore the 1962 David Lean classic that launched Peter O'Toole to stardom. Over the years since the film's release, cuts have been made and this re-release marks the first time in 25 years that the complete film has been shown anywhere.

Lawrence of Arabia tells the true story of T.E. Lawrence, a British soldier who rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel during World War I and helped lead the Arab revolt against the Turks in 1917 and 1918.

The film is a feast for the eyes and may well be the best use of widescreen ever. If you haven't seen the film before, don't watch it on television unless it is letterboxed — cropping saps this film of much of its power.

Lawrence contains a great ensemble cast, including the mesmerizing title role by O'Toole and a fine cast of actors including Anthony Quinn, Omar Sharif, Alec Guinness, Anthony Quayle, José Ferrer and Claude Rains. For me, a most fascinating benefit of this film was being able to see Rains in color. He seems as if he's permanently trapped in black and white in classics such as Casablanca and Notorious.

The film run 222 minutes, but it never bores. The movie illustrates epic filmmaking on a personal scale. Though the film lags a bit in the second half, it still is great. Visually, Lawrence of Arabia could very well be unsurpassed, especially when you see it on a 70 millimeter print. Sometimes the entire screen seems filled with sand and as figures appear over the dunes, it's hard to suppress your awe.

In addition to O'Toole's magnificent work, the rest of the cast contributes fine moments as well, especially David Lean-regular Guinness and Quinn. Trying to review a film such as this borders on ridiculous. The opportunity to see these sort of classics in a movie theater occur so rarely that you feel afraid to criticize any aspect for fear it will keep someone away.

One question always has puzzled me about biopics. Why does it seem necessary that every historical film begin by showing us how the main character dies? They did it in Gandhi and they do it in Lawrence. The film begins showing how Lawrence was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1935. While the sequence is exceptionally well done, I didn't know that much about T.E. when I entered the theater. Since the movie contains a lot of action and battle sequences, suspense over whether Lawrence could be killed is lost. Historians may know what happened to him, but I didn't.

Lean, who made this five years after Bridge on the River Kwai, has concentrated on epics in his later career — and he's still working, having just released A Passage to India five years ago.

Re-releases of anything not made by Disney are rare and movie fans would be remiss if they took a pass on this opportunity to see the restored Lawrence on the big screen.

Tweet

Labels: 60s, Disney, Ferrer, Guinness, Lean, O'Toole, Rains, Scorsese, Spielberg

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE