Friday, May 18, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part I

By Edward Copeland

"First comes the word, then comes the rest" might be the most famous quote attributed to Richard Brooks, who began his life 100 years ago today in Philadelphia as Ruben Sax, son of Jewish immigrants Hyman and Esther Sax. He wrote a lot of words too — sometimes using only images. In fact, too many to tell the story in a single post. so it will be three. His parents came from Crimea in 1908 when it belonged to the Russian Empire. Like the parents of a great director of a much later generation and an Italian Catholic heritage, Hyman and Esther Sax also worked in the textile and clothing industry. Sax's entire adult working life revolved around the written word — even while he busied himself with other tasks. “I write in toilets, on planes, when I’m

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

Though Brooks' legend derives predominantly from his film legacy, he experienced his first rush of acclaim with the publication of his debut novel, written while stationed at Quantico at night in the bathroom, according to the account in Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks by Douglass K. Daniel. Several publishers rejected it until Edward Aswell at Harper & Brothers, who also edited Thomas Wolfe, agreed to take it — and he shocked Brooks further by telling him (after a few suggestions) they planned to publish in May 1945. This news flabbergasted Brooks who obtained a weekend pass to go to New York because Aswell insisted on informing him in person. Now Brooks had to return to Quantico where the top officers of the Corps about shit bricks when The New York Times published a big review of The Brick Foxhole soon after it hit shelves. (Orville Prescott's take was mixed, assessing it as compulsively readable but weak on characterization.) Its story of hate and intolerance within the Marines brought threats of court-martialing Brooks, since he'd ignored procedure and never submitted the novel to Marine officials for approval ahead of time. They wanted to avoid bad publicity, especially with all the good feelings as the war wound down. "There was nothing in that book that violated security, but their rules and regulations were not for that purpose alone," Brooks told Daniel. Aswell prepared to launch a P.R. counteroffensive with literary giants such as Sinclair Lewis and Richard Wright ready to stand by Brooks. In case you don't know the story of the novel, it concerns a Marine unit in its barracks and on leave in Washington. Through their wartime experiences, some of the men truly turned ugly, suspecting cheating wives and tossing hate against any non-white Christian. It turns out, though the real Marines let the matter drop, what bothered them

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

While he didn't want to make a movie of The Brick Foxhole himself, another former newspaperman turned socially conscious film artist met with Brooks about working with his independent production company. At first, Mark Hellinger tried to lure Brooks away from Universal with the promise of doubling his salary if he'd adapt a play he liked into a movie, but before Brooks could consider that offer, Hellinger called with a more pressing matter. He was producing an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's famous short story The Killers. The problem: someone had to dream up what happened after the brief tale ends because it certainly wouldn't last 90 minutes otherwise. Hellinger flew Brooks out to meet Papa himself, but he didn't get much out of him but he did come up with an idea for what would happen after the story ends. Hellinger liked it and sent it to John Huston, who wrote the screenplay as a favor. Since both Brooks and Huston had contracts at other studios, neither got screen credits, so Ernest Hemingway's The Killers' official screenplay credit goes to Anthony Veiller, who received an Oscar nomination for best screenplay. He'd previously shared a nomination in the same category for Stage Door. The film also made a star out of Burt Lancaster, who would work with Brooks several times and be his lifelong friend. In fact, Lancaster would star in the next screenplay that Brooks wrote, a Mark Hellinger production directed by one of those people Edward Dmytryk eventually would name before the House Un-American Activities Committee. The film, of course, would be the still-powerful Brute Force, the director, Jules Dassin.

John Huston wasn't happy. Producer Jerry Wald called him, excitement in his voice, to tell him he'd secured the rights to Maxwell Anderson's Broadway play Key Largo for Huston to direct. This didn't thrill Huston, who thought the play gave new meaning to the word awful. Written in blank verse, Anderson's play concerned a deserter from the Spanish-American War. People at a hotel do get taken hostage, but by Mexican hostages. Essentially, Huston tossed the play in the trash bin. Huston hired Brooks to co-write an in-title only version and, still pissed at Wald, barred him from the set. Part of Huston's anger stemmed from the HUAC nonsense, (His outrage would drive him to move to Ireland for a large part of the 1950s.) so he couldn't stomach adapting a play by Anderson whom he considered a reactionary because of his hate of FDR. Despite Huston's distaste for the project, he

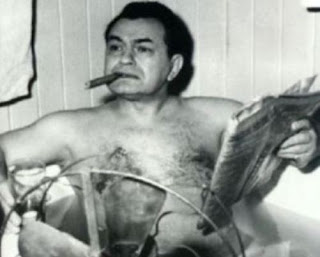

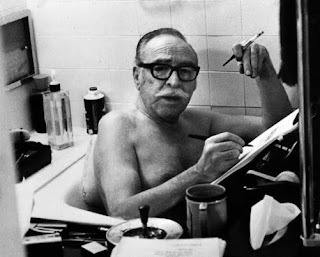

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.While I would have liked to have viewed more of Brooks' work that I've never seen (and to re-visit some which I have), time and availability, combined with his prolific nature and the industry's increasingly cavalier willingness to let both old and recent films fade into oblivion, proved to be a problem. After Huston's generosity, Brooks' directing debut would arrive two years later. Four films where Brooks worked

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.

enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.With 1955, Brooks wrote and directed the first film that truly garnered him an identity as more than a writer who directs but as a director with Blackboard Jungle, a film that admittedly manages to look both dated and timely simultanouesly, First, as so many old films did, it had to start with a long scroll explaining that American schools maintain high standards, but we need to worry about these juvenile

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk.

desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk. Tweet

Labels: blacklist, Bogart, Capra, Cary, Dassin, Doris Day, Edward G., Fiction, Fitzgerald, Fuller, Ginger Rogers, Glenn Ford, Hemingway, Huston, Lancaster, Liz, Mazursky, Poitier, Robert Ryan, Widmark

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, December 23, 2011

“I never dreamed that any mere physical experience could be so stimulating!”

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

One of my fondest memories of collegiate life was a weekend in 1982 in which the activities department at Marshall University put together a film tribute to actor Humphrey Bogart as part of their weekly showing of classic and cult movies. I can’t recollect the exact scheduling (the MU people would showcase a feature on Friday afternoons/evenings and then have a matinee on Sundays) but I do recall that Key Largo, The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca made up the lineup and this little event exposed me to three of Bogie’s major classics for the first time. The last film, which I have forcefully stated many times at my home base of Thrilling Days of Yesteryear, is my favorite movie of all time. I still can remember the audience cheering wildly at Claude Rains’ discovery that Bogart, as Rick Blaine, has double-crossed him (“Not so fast, Louie…”) and will be helping Ingrid Bergman and Paul Henreid out on the next plane to Lisbon.

That weekend wasn’t my introduction to one of my favorite actors, however. Years earlier, through the magic of television, I saw the film that earned Bogie his best actor Oscar, The African Queen (1951), because my mother was a huge fan of the film and it soon became one of my favorites, one of those movies which gets watched to the very end if I should happen to see it playing on, say, Turner Classic Movies. Fortunately for classic movie fans, you don’t have to wait for its TCM scheduling — Queen made its Region 1 DVD debut (it had only been previously available in Region 2 releases) on March 23, 2010 (simultaneously with its Blu-ray debut) in a breathtakingly gorgeous restoration from Paramount Home Video. In fact, it was explained that its long absence from DVD was due to the difficulty in locating the film’s original negative. Queen, based on the 1935 novel by C.S. Forester, made the rounds of motion picture theaters 60 years ago today.

It is September 1914, and Anglican missionaries Samuel (Robert Morley) and Rose Sayer (Katharine Hepburn) spread the gospel to natives in the German Eastern African village of Kungdu when they receive a visit from Charlie Allnut (Bogart), skipper of the African Queen. Allnut is responsible for bringing their mail and supplies, and during his stopover informs the Sayers that since war has broken out between England and Germany, their mail delivery will be affected; he also advises the two of them to abandon their post because of his concern that the German army will recruit Kungdu’s able-bodied young men to fight for their cause. Samuel staunchly refuses, but only seconds after Charlie departs he and Rose are visited by German soldiers, who respond to Samuel’s protests with the business end of a rifle butt as his fellow conscripts start rounding up the natives and setting the village ablaze. With Kungdu in ruins, Samuel soon comes down with fever and dies — Charlie returns to the village in time to help Rose bury her brother and then agrees to spirit her away on his boat.

Despite the vessel being well-stocked with provisions, Charlie and Rose’s escape from their circumstances will not be an easy task; the Ulanga River presents obstacles in the three sets of rapids and a German stronghold in the form of a fort in the town of Shona. Because the ship’s supplies also include blasting materials (gelignite) and oxygen/hydrogen tanks, Rose, filled with both stiff-upper-lip patriotism and bitterness over her brother's death, proposes that the two of them fashion makeshift torpedoes out of the materials and use them to take on the Queen Louisa (or as the Germans refer to it, the Königin Luise), a large gunboat guarding the lake in which the Ulanga empties. Charlie is convinced that what Rose is suggesting will be a suicide mission, but he agrees to the plan only to get cold feet shortly after navigating the first set of rapids. He declares his intentions to have nothing to do with Rose’s plan after a gin-sponsored bender. The next morning, suffering from a hangover, Charlie watches helplessly as Rose pours every last drop of his precious gin into the Ulanga and follows this up with “the silent treatment,” Charlie reconsiders the mission.

German soldiers fire upon Charlie and Rose as they pass the fort at Shona, and though the two of them avoid being hit by gunfire, the men do manage to hit the African Queen’s boiler, disconnecting one of its steam pressure hoses and bringing the vessel to a temporary halt. (Charlie manages to reconnect the hose and they pass by the fort unscathed.) The boat then hits the second set of rapids and survives the ordeal with minimal damage, prompting the duo to engage in a celebratory embrace which leads to a kiss. It is by this time in their adventure that they cannot deny the strong attraction that has developed between them, which leads to an amusing scene in which Rose asks her new boyfriend awkwardly: “Dear, what is your first name?”

The couple finally navigates the final set of rapids, but in doing so sustain damage to the Queen’s shaft and propeller. Rose convinces Charlie that he has the skills to repair the boat and, using what is available on a nearby island, he restores the Queen to working order and they’re off again down the river. However, they soon discover the deception of the Ulanga River; they “lose the channel” and become stranded on a mud bank surrounded by reeds in all directions — with Charlie sidelined with fever (after an experience in which he emerges from the murky water covered with leeches). When all appears lost, Rose offers up a prayer asking that she and Charlie be granted entrance into the Kingdom of Heaven…and in answer to that prayer, rains from a monsoon soon lift the boat out of the mud and into the mouth of the lake — as it turns out, they were less than a hundred yards from their destination.

Charlie and Rose, having spotted the Louisa patrolling the lake, prepare the makeshift torpedoes and go after the German craft come nightfall, but en route they get trapped in a squall and the African Queen capsizes due to the holes made in its sides to accompany the torpedoes. The Louisa’s crew captures Charlie who is crestfallen because he thinks Rose has drowned, so much so that he stoically accepts the captain’s decision to hang him. Surprisingly, Rose has survived the Queen’s sinking and is brought aboard to face questioning where she proudly tells the Louisa’s captain of their plot to scuttle the ship, resulting in her sentence of execution as well. Before the couple's hanging, Charlie asks the Louisa’s captain if he’ll marry him and Rose; that buys enough time for the Louisa to run into the Queen’s wreckage, detonating the torpedoes and sinking the ship. The newly married Allnuts swim to safety toward the Belgian Congo as the film concludes.

Upon its publication in 1935, The African Queen originally was optioned for a film adaptation by several studios including RKO and Warner Bros. — Charles Laughton and Elsa Lanchester even made a movie (with a similar story, though the source material came from W.

Somerset Maugham) in 1938 entitled Vessel of Wrath (aka The Beachcomber). Over the years, several actors were suggested for the part of Charlie Allnut; John Mills, David Niven and James Mason being the most prominent — Bette Davis was the only actress in serious contention for Rose, but after an abortive attempt to do the movie in 1947 (scuttled because of Davis’ pregnancy) she was passed over two years later in favor of Katharine Hepburn when the production got underway. (Director John Huston, who had already chosen Humphrey Bogart for his Charlie, once stated in an interview that Hepburn was tabbed because Bogart had expressed an interest in working with her.) While it’s possible to see Davis playing the part, the choice of Hepburn (in what would be her first color film) was the right one despite some initial reservations on the part of Huston with Kate’s performance. Thinking she was making the Rose character a little too severe, John suggested that Hepburn imitate the indomitable spirit of former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who always remained cheerful despite any adversity. (Hepburn later observed that Huston’s suggestion was the finest bit of directing she’d ever received.)

Somerset Maugham) in 1938 entitled Vessel of Wrath (aka The Beachcomber). Over the years, several actors were suggested for the part of Charlie Allnut; John Mills, David Niven and James Mason being the most prominent — Bette Davis was the only actress in serious contention for Rose, but after an abortive attempt to do the movie in 1947 (scuttled because of Davis’ pregnancy) she was passed over two years later in favor of Katharine Hepburn when the production got underway. (Director John Huston, who had already chosen Humphrey Bogart for his Charlie, once stated in an interview that Hepburn was tabbed because Bogart had expressed an interest in working with her.) While it’s possible to see Davis playing the part, the choice of Hepburn (in what would be her first color film) was the right one despite some initial reservations on the part of Huston with Kate’s performance. Thinking she was making the Rose character a little too severe, John suggested that Hepburn imitate the indomitable spirit of former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who always remained cheerful despite any adversity. (Hepburn later observed that Huston’s suggestion was the finest bit of directing she’d ever received.)Hepburn’s performance in the film is a marvel because the actress bravely allowed herself to be filmed au natural, which no doubt stunned audiences at the time as they saw the great Kate playing her true middle-age (something that she would go on to do from that point in

her career, particularly in David Lean's wonderful 1955 film Summertime) and yet they witnessed a woman who transforms from a “crazy, psalm-singing, skinny old maid” into a spunky, sexy woman whose romance with the unlikely Charlie makes her giddy as a schoolgirl (I love the scene where she giggles and laughs uncontrollably at Charlie’s animal noises on the boat). The relationship between the characters is so genuine and feels so right, you literally watch the barriers between the two melt away during the course of their adventure. Pay particularly close attention when Rose helps Charlie pump water out of the boat and she stops momentarily, caught up in her romantic reverie. Charlie has got it bad as well. In assisting Rose with the task,c you can just see how dazed and delighted he is to have found true love. Director John Huston could scarcely ignore the magic between the two characters and decided to buck the tradition of most of his films (which tend to feature what one critic has called “beautiful losers”) by allowing Charlie and Rose’s torpedo scheme to succeed (in Forester’s book the plan doesn’t quite come off) and joining the two in holy matrimony (a plot device also designed to ward off criticism by bluenoses finger-wagging at Charlie and Rose’s cohabitation outside marriage).

her career, particularly in David Lean's wonderful 1955 film Summertime) and yet they witnessed a woman who transforms from a “crazy, psalm-singing, skinny old maid” into a spunky, sexy woman whose romance with the unlikely Charlie makes her giddy as a schoolgirl (I love the scene where she giggles and laughs uncontrollably at Charlie’s animal noises on the boat). The relationship between the characters is so genuine and feels so right, you literally watch the barriers between the two melt away during the course of their adventure. Pay particularly close attention when Rose helps Charlie pump water out of the boat and she stops momentarily, caught up in her romantic reverie. Charlie has got it bad as well. In assisting Rose with the task,c you can just see how dazed and delighted he is to have found true love. Director John Huston could scarcely ignore the magic between the two characters and decided to buck the tradition of most of his films (which tend to feature what one critic has called “beautiful losers”) by allowing Charlie and Rose’s torpedo scheme to succeed (in Forester’s book the plan doesn’t quite come off) and joining the two in holy matrimony (a plot device also designed to ward off criticism by bluenoses finger-wagging at Charlie and Rose’s cohabitation outside marriage).

Huston and Bogart were not only close friends in real life, they had made onscreen magic working together as far back as the director’s feature film debut, The Maltese Falcon, and as recently as one of Huston’s masterpieces, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. To accommodate the handicap of Bogart’s inability to do a Cockney accent, however, the character of Charlie Allnut became a Canadian, prompting a hefty rewrite of the script. Though the role of Charlie would seem a departure for Bogie, known for his tough-guy antiheroes, there are many shared characteristics between him and other Bogart characters (Allnut shares the same unshaven scruffiness as Sierra Madre’s Fred C. Dobbs, for example), particularly that of the individual who eventually comes around in support of the cause for the greater good. Bogart was nominated for a best actor Oscar for his performance (Hepburn also was tabbed, along with Huston for his direction and screenplay with co-writer James Agee) and despite stiff competition that year from Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift and Fredric March, the Academy got sentimental and awarded the actor the coveted trophy.

The realistic atmosphere and look of the film stem from the decision by Huston and producer Sam Spiegel (along with brothers John and James Woolf, who financed the movie through their Romulus Films company) to shoot on location in Uganda and the Congo in Africa.

Under normal circumstances, this production would have been daunting but because it was a Technicolor film (which necessitated large, unwieldy cameras), the shoot proved to be an ordeal for all involved. Hepburn later detailed the colorful history of the production in a book, The Making of the African Queen, or: How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind, and a fascinating featurette included on the Paramount Home Video DVD, Embracing Chaos: Making the African Queen, also contains enthralling anecdotes about this remarkable motion picture. The cast and crew survived any number of adverse conditions, chiefly among them sickness due to the dysentery resulting from contaminated drinking water. Hepburn, for example, became so ill that a bucket was placed near the pipe organ she plays in the opening church scenes. According to cinematographer Jack Cardiff, the actress was “a real trouper.” The only two individuals on the film who escaped illness, according to legend, were Huston and Bogart, primarily because the men subsisted on the imported Scotch they had brought with them. (Bogie later cracked: “All I ate was baked beans, canned asparagus and Scotch whiskey. Whenever a fly bit Huston or me, it dropped dead.”)

Under normal circumstances, this production would have been daunting but because it was a Technicolor film (which necessitated large, unwieldy cameras), the shoot proved to be an ordeal for all involved. Hepburn later detailed the colorful history of the production in a book, The Making of the African Queen, or: How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind, and a fascinating featurette included on the Paramount Home Video DVD, Embracing Chaos: Making the African Queen, also contains enthralling anecdotes about this remarkable motion picture. The cast and crew survived any number of adverse conditions, chiefly among them sickness due to the dysentery resulting from contaminated drinking water. Hepburn, for example, became so ill that a bucket was placed near the pipe organ she plays in the opening church scenes. According to cinematographer Jack Cardiff, the actress was “a real trouper.” The only two individuals on the film who escaped illness, according to legend, were Huston and Bogart, primarily because the men subsisted on the imported Scotch they had brought with them. (Bogie later cracked: “All I ate was baked beans, canned asparagus and Scotch whiskey. Whenever a fly bit Huston or me, it dropped dead.”)The size of the African Queen also presented problems where the Technicolor cameras were concerned — because there was not enough room for the cameras on the boat (which measured 16 feet long and 5 feet wide), a mock-up of the craft was put together on a larger raft and the production used several such rafts to the point where the river hosted a small flotilla, with the last pontoon housing Hepburn’s “loo” (her contract stipulated that she be provided with private restroom facilities). The waters of the river, considered poisonous due to bacteria, animal excrement, etc., were never utilized in shots or sequences requiring Bogie and Kate’s immersal — they were filmed separately in studio tanks at the Isleworth Studios in London. Despite the challenges presented in the making of the film, what resulted was a certified masterpiece — at a time when “independent” films are the Hollywood darlings of today, The African Queen was a noteworthy example of that particular type of movie (made outside the dictates of the studio system) even though industry wags remained skeptical about its performance at the box office. (The film was a tremendous success, but director Huston never collected on the payday because of his desire to sever his ties with producer Spiegel; cinematographer Cardiff also had the option of taking a percentage of the profits to subsidize a lower salary but he begged off, having had a bad experience with another film he had worked on in that same year, The Magic Box.)

Queen enraptured me as a young movie fan, and continues to do so today — I think it would be the perfect film to introduce to classic movie-adverse audiences because of its skillful blend of adventure, romance and even comedy (There are some hilarious moments in this movie, chiefly the scene where Charlie sets down to tea with the Sayers). The fact that it’s in gorgeous Technicolor also is a plus, particularly since new generations often shrink from movies filmed in monochrome. Writer-director Nicholas Meyer observes in the Embracing Chaos documentary that “Movies are like soufflés — they either rise or they don’t — and people seldom are able to predict or tell you why. The African Queen is an improbably cinematic triumph, made against seemingly insurmountable odds and comprising a bunch of disparate, desperate characters who, saving the movie business, would probably not even be in the same world let alone the same room with each other.” The results of that grand moviemaking adventure captured on film make The African Queen a must-see for audiences of any age.

Tweet

Labels: 50s, Bacall, Bette, Bogart, Brando, Clift, Fredric March, Huston, Ingrid Bergman, K. Hepburn, Laughton, Lean, Mason, Movie Tributes, Niven, Rains

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, December 15, 2011

“Sitzen machen!”

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

The very first Billy Wilder film I watched as part of my burgeoning film education wasn’t one of his acknowledged classics such as Double Indemnity (1944) or Sunset Blvd. (1950) — or even Some Like it Hot (1959) or The Apartment (1960) but a movie I consider “second-tier” Wilder, the 1961 Cold War comedy One, Two, Three. Keep in mind that I don’t refer to the film as second-tier because I dislike it or am trying to denigrate the work; it’s just that with the passage of time, the topicality of One, Two, Three hasn’t particularly worn well, something that I’ve also noticed in Ninotchka (1939), a Wilder-scripted comedy (but directed by Ernst Lubitsch) whose plot and themes are revisited in the later feature. (One, Two, Three also contains echoes of the filmmaker’s earlier Sabrina, the 1954 romantic comedy starring Audrey Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart and William Holden.)

The dated political content of One, Two, Three doesn’t do it any favors, but this is nevertheless going to be an enthusiastic review of a film that debuted in motion picture theaters 50 years ago on this date. “Second-tier” Wilder is miles and away better than the best movie helmed by any director today, and with his longtime partner I.A.L. “Izzy” Diamond, Billy crafted a fast, frenetic and funny farce (based on a 1929 play, Egy, kettö, három, by Ferenc Molnár) that still can leave an audience breathless with laughter. The icing on this cinematic cake is that, before he returned briefly to movies for Ragtime in 1981, One, Two, Three served as the penultimate cinematic swan song for the legendary James Cagney.

C.R. “Mac” MacNamara (Cagney) is head of operations for Coca-Cola in West Berlin, a month or two before the closing of the Brandenburg Gate (and subsequent construction of the Berlin Wall). Company man Mac is extremely loyal to the Pause That Refreshes, and has been working diligently to advance himself, with an eye on assuming the post of European operations in London by shrewdly brokering a deal to introduce the soft drink to the Soviet Union. (Mac was formerly in charge of Coca-Cola’s interests in the Middle East but a mishap involving Benny Goodman resulted in Mac’s demotion after the bottling plant was destroyed in a riot.) He’s scheduled to meet Soviet representatives Peripetchikoff (Leon Askin), Borodenko (Ralf Wolter) and Mishkin (Peter Capell) to discuss introducing the soft drink behind the Iron Curtain, and is juggling that conference with plans to further his “language lessons” with luscious secretary Fräulein Ingeborg (Lilo Pulver).

The roguish MacNamara is planning to take advantage of his wife Phyllis’ (Arlene Francis) scheduled trip to Venice with their two children to dally with Ingeborg, but those plans are put on hold when Mac receives a call from his boss, Wendell P. Hazeltine (Howard St. John), in Atlanta. Hazeltine’s daughter Scarlett (Pamela Tiffin) is en route to Berlin, and he’s entrusted Mac to keep close tabs on her since Scarlett is a bit of a shameless flirt (despite being only 17). As an example of her hot-blooded tempestuousness, Mac and Phyllis meet her at the airport just in time to find her awarding herself as a lottery prize to the flight crew (the winner is a man called Pierre, prompting Phyllis to dub him “Lucky Pierre”). What starts out as a two-week assignment stretches into two months, but Mac is pleased that he’s keeping Scarlett on a tight leash.

On the day before the Hazeltines travel to Berlin to collect their daughter, Scarlett turns up missing. Mac learns from his chauffeur (Karl Lieffen) that the girl has been bribing him to let her off at the Brandenburg Gate every night to allow her to cross the border into East Berlin. Devastated by this news, MacNamara expresses relief when Scarlett turns up at his office, but then is hit by a streetcar when she announces that she’s been spending all her time with an East German Communist named Otto Ludwig Piffl (Horst Buchholz), whose political philosophy fills Mac with utter revulsion. The problem for Mac is that the fling between Otto and Scarlett has gone beyond mere puppy love — they tied the knot in East Berlin — something that will no doubt go over with her parents like flatulence at a funeral. The devious MacNamara arranges for the young Commie to be picked up by the East German authorities after they find a “Russkie Go Home” balloon affixed to his motorcycle’s exhaust pipe and a cuckoo clock (that plays “Yankee Doodle” on the hour) wrapped in a copy of The Wall Street Journal in his sidecar.

Mac’s machinations even go as far as to arranging for the couple’s marriage license to disappear from the official record, and he gloats about his triumph to a furious Phyllis, who has finally had enough of her husband’s neglect of their marriage in his pursuit of Coke advancement. The popping of champagne corks is put on hold when Scarlett faints after hearing of Otto’s arrest. An examination by a physician reveals that the girl has a Communist “bun in the oven!” Racing against an ever-ticking clock before the Hazeltines touch down in Berlin, Mac manages to spring Otto and then embarks on an extreme makeover of the hostile Bolshevik to transform him into someone whom Scarlett’s parents will approve. Against all odds, McNamars’s scheme comes off without a hitch, but his dreams of taking over as head of Coke’s European office are dashed when Hazeltine announces the job will go to his new son-in-law! Kicked upstairs to a position in the home office in Atlanta, Mac will reconcile with Phyllis and will hopefully live happy ever after.

Because the emphasis in Ninotchka is primarily on the romance between stars Greta Garbo and Melvyn Douglas, that film hasn’t dated nearly as badly as One, Two, Three, whose jibes at Cold War politics make it more of a period piece, and is likely to appeal mostly to the history majors in the audience. (Wilder’s cynicism also comes to the fore in this film in that you never really believe the romance between Scarlett and Otto. They have to stay married because there’s a “bouncing baby Bolshevik” on the way.) But if you’re able to put its topicality on a back burner, there is much to enjoy in the film; it is a spirited farce, buoyed by the participation of Cagney as the main character of C.R. MacNamara. Mac is a typical Wilder hero: not the most admirable man (he’s cheating on his wife and comes across as a bit of a jerk) but an individual who rises to the occasion when faced with a crisis. Cagney, whose screen performances were usually marked by his established persona as a fast-talking wise guy, is a marvel to watch in this film, barking out orders and, in the words of a reviewer for Time magazine, “swatting flies with a pile driver.”

Cagney did not have an easy time making the film. He was no spring chicken at the time of its production, and having to spout Wilder’s rat-a-tat dialogue at a furious pace was often difficult, particularly in one scene where the director insisted on Jimmy’s completing it in one take. Cagney was tripped up continually by the line, “Where is the morning coat and striped trousers?” It was never explained to his satisfaction why Billy refused to let him paraphrase the dialogue, and so it took 57 takes to get it done (which might explain why the finished product comes off as a little mechanical). Cagney also was not enamored of co-star Buchholz and his scene-stealing antics; Jimmy had experienced a similar incident when making Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942) and had trouble with character actor S.Z. “Cuddles” Sakall upstaging him in a scene, but he overlooked it because Sakall “was an incorrigible old ham who was quietly and respectfully put in his place by [director] Michael Curtiz.” But if Wilder hadn’t exercised his director’s prerogative and discouraged Horst to stop with the same, Cagney “would have been forced to knock him on his ass, which I would have very much enjoyed doing.”

All in all, the experience of making One, Two, Three drained Cagney and made him realize that he’d rather be enjoying retirement, and upon the movie’s completion, the actor settled in for a second career as a gentleman farmer (though he did narrate a TV special and a 1968 Western, Arizona Bushwhackers, in the interim). He was coaxed out of retirement for a small role in Ragtime in 1981 (as the police commissioner, his last big-screen appearance and a final reunion with his longtime chum/movie co-star Pat O’Brien), and an additional role in a 1984 TV movie Terrible Joe Moran where he played a retired boxer forced to used a wheelchair, but still a fighter to the core. Having suffered a stroke affected Cagney's performance somewhat and it was the final project before his passing in 1986.

In watching One, Two, Three, it almost seems like Wilder and Diamond presciently knew it would be James Cagney’s last significant silver screen work, what with all the in-jokes and references pertaining to the actor sprinkled throughout. There’s the aforementioned cuckoo clock (Cagney’s best actor Oscar was awarded for his role as George M. Cohan in Dandy), but there’s also a scene in which Jimmy picks up a grapefruit half and moves menacingly toward Buchholz’s Otto (shades of The Public Enemy!) and a funny cameo by Red Buttons as an Army MP who imitates Cagney while having a conversation with Jimmy’s MacNamara. Of course, the self-referential jokes are a staple of Wilder’s film comedies; at one point in the movie Cagney cries out “Mother of mercy, is this the end of little [sic] Rico?” as a nod toward Edward G. Robinson’s memorable last line in Little Caesar (something Billy also did in Some Like It Hot, in which George Raft asks a coin-flipping Edward G. Robinson, Jr., “Where’d you pick up that cheap trick?”).

Wilder also recycled a line used by Bogart in Sabrina, “I wish I were in hell with my back broken” (a variation of this also turns up in Wilder’s Five Graves to Cairo) and in fact, borrowed Sabrina’s “switcheroo” ending (right down to the hat and umbrella) and use of the song “Yes, We Have No Bananas” (only it’s sung in German in One, Two, Three). Music is at the center of many of the gags in the film; in addition to “Bananas,” comic set pieces use Aram Khachaturian's “Sabre Dance” (the main theme that accompanies MacNamara’s breakneck activities, described by Wilder and Diamond to be played “110 miles an hour on the curves…140 miles an hour on the straightways”), Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” and Brian Hyland’s “Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini.”

Though watching Cagney go through his paces is the main draw of One, Two, Three, his co-stars also rise to the occasion. Arlene Francis is probably best known as a panelist on the longtime TV show What’s My Line?, but she provides solid support as the acid-tongued, long-suffering Phyllis (“Yes, Mein Führer!”). The real-life antagonism Cagney had for Buchholz works to the film’s advantage, of course, but Horst has a certain goofy charm that makes his Otto likable despite his political leanings, and Pamela Tiffin is delightful as the ditzy Scarlett — many a classic movie buff has wondered why, despite high-profile showcases in films such as Summer and Smoke (1961) and Harper (1966), Tiffin’s film career never reached its full potential. Fans of Hogan’s Heroes will recognize Leon Askin as Comrade Peripetchikoff, but you can also hear Askin’s fellow Hogan player John “Sgt. Schultz” Banner as the voice of two of the characters in the film — in fact, when I watched One, Two, Three the other day, it was the first time I noticed that the voice for Count von Droste Schattenburg (the aristocrat who “adopts” Otto, played by Hubert von Meyerinck) is dubbed by character great Sig Ruman!

Jules White, the head of Columbia Studios’ comedy shorts department, once described his directorial style as “mak(ing) those pictures move so fast that even if the gags didn’t work, the audiences wouldn’t get bored.” Wilder and Diamond upped that ante with One, Two, Three; the film not only moves at lightning speed, the gags remain funny today. (My particular favorite has MacNamara calling one of the Russians “Karl Marx,” and when the comrade gives Fräulein Ingeborg a generous swat on her fanny, he quips, “I said Karl Marx not Groucho.”) In Cameron Crowe’s book Conversations with Wilder, the legendary writer-director observed: “The general idea was, let's make the fastest picture in the world…And yeah, we did not wait, for once, for the big laughs. We went through the big laughs. A lot of lines that needed a springboard, and we just went right through the springboard…” The film may not have been a box-office smash (both in the U.S. or Germany) but the final gag left an impression on me when I first saw it as a kid (“Schlemmer!”), and 50 years later watching the great Jimmy Cagney rush pell mell through farcical circumstances beyond his control remains a Wilder devotee’s delight.

Tweet

Labels: 60s, A. Hepburn, Bogart, Books, Cagney, Curtiz, Edward G., Garbo, Holden, Lubitsch, Movie Tributes, Nonfiction, Oscars, Raft, Television, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

The first time was not the charm

By Edward Copeland

Though one shouldn't assume, I'm guessing the third time did indeed prove to be the charm as far as screen adaptations of Dashiell Hammett's The Maltese Falcon go, even though time prevented me from sampling 1936's Satan Met a Lady starring Bette Davis. Reports on that incarnation of Hammett's story claim it turned the tale into farce, changed all names to protect the fictional and rechristened the much-sought-after Maltese Falcon as the fabled Horn of Roland. Unfortunately, I did have time to see the first crack movies took at Hammett's detective classic, director Roy Del Ruth's 1931 film The Maltese Falcon. I can see now — with Warner Bros., screwing up the story credited with creating the hard-boiled detective genre twice within seven years of its publication — how it became a matter of pride and urgency to try again as soon as 1941 to right the cinematic wrongs. This time, the studio hired a talented writer (John Huston) and gave him his first shot at directing in the hopes he'd make the definitive film version of The Maltese Falcon, which he did, even though his casting of Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade looked unorthodox at the time. However, Bogart's Spade ended up being as definitive a take on the private eye as the film itself became on the work of fiction. Now, I realize people exist who enjoy slowing down to gaze upon traffic accidents and part of these misguided souls wants to see how bad the 1931 version really could be. Trying to spare these folks an hour and 20 minutes of their lives prompts me to write about that 1931 Maltese Falcon today.

More than merely a decade separates the two films titled The Maltese Falcon and — with the exception of more sexual innuendo because the camera rolled on the 1931 version in pre-Code era Hollywood — little of what's different plays in the first film's favor. In fact, Huston's Maltese Falcon proved so beloved that when televisions began to spring up in U.S. households and old movies were rerun, the first Maltese Falcon got a new title: Dangerous Female. It's somewhat ironic that the 1931 movie would end up traveling under an alias

because one of the most mystifying changes the 1931 film made from Hammett's story was making that "dangerous female" be named Ruth Wonderly from beginning to end. She still lies and kills, but she doesn't use any fake names at all. Brigid O'Shaughnessy doesn't exist here. In Hammett's version, she also used other aliases but even Huston edited it down to two. Bebe Daniels plays Miss Wonderly in the 1931 version and she's representative of that film's biggest problem. Even some of the cast who were good in other roles in other films, weren't here. Perhaps it's just seeing them in contrast to the brilliant 1941 ensemble, but with the exception of Una Merkel, who plays Sam Spade's secretary Effie in 1931, nearly the entire cast stinks. Granted, part of the problem stemmed from the time period and the cast was populated with many performers who made their names in silents and didn't make the transition well. The only truly decent sound role that Daniels ever got was as the fading star Dorothy Brock in the 1933 musical 42nd Street. However, when I mentioned it as a pre-Code picture, that was not an exaggeration. The opening scene shows a pair of female legs adjusting her dress and walking out of Sam Spade's office followed by Spade (Ricardo Cortez) adjusting the pillows on the couch with the definite implication that hanky panky had been taking place. His relationship with Miss Wonderly seems to be sexual for sure and there's no question about his affair with partner Miles Archer's wife Iva. As Wonderly, hiding from Iva and trying to make her jealous at the same time, Bebe Daniels takes a bath in a scene that nearly shows her nude.

because one of the most mystifying changes the 1931 film made from Hammett's story was making that "dangerous female" be named Ruth Wonderly from beginning to end. She still lies and kills, but she doesn't use any fake names at all. Brigid O'Shaughnessy doesn't exist here. In Hammett's version, she also used other aliases but even Huston edited it down to two. Bebe Daniels plays Miss Wonderly in the 1931 version and she's representative of that film's biggest problem. Even some of the cast who were good in other roles in other films, weren't here. Perhaps it's just seeing them in contrast to the brilliant 1941 ensemble, but with the exception of Una Merkel, who plays Sam Spade's secretary Effie in 1931, nearly the entire cast stinks. Granted, part of the problem stemmed from the time period and the cast was populated with many performers who made their names in silents and didn't make the transition well. The only truly decent sound role that Daniels ever got was as the fading star Dorothy Brock in the 1933 musical 42nd Street. However, when I mentioned it as a pre-Code picture, that was not an exaggeration. The opening scene shows a pair of female legs adjusting her dress and walking out of Sam Spade's office followed by Spade (Ricardo Cortez) adjusting the pillows on the couch with the definite implication that hanky panky had been taking place. His relationship with Miss Wonderly seems to be sexual for sure and there's no question about his affair with partner Miles Archer's wife Iva. As Wonderly, hiding from Iva and trying to make her jealous at the same time, Bebe Daniels takes a bath in a scene that nearly shows her nude.

What ultimately ruins this version of The Maltese Falcon and, I suspect, would be the key to any attempt to tell this story belongs to whoever gets cast to play Sam Spade. In the 1931 case, Ricardo Cortez simply sinks the character and takes the movie down with him. Cortez, like Daniels, came from silents. Looking at his resume, he later did appear in one good film, his final film actually — John Ford's The Last Hurrah in 1958 — not that I recall him in it. Cortez portrays Spade as a grinning ghoul. He never stops smiling, laughing or giggling. Because he only seems to have one emotional note, every piece of dialogue gets the same spin, ruining some great lines.

When he's meeting with Caspar Gutman (Dudley Digges) — for some reason Gutman's first name starts with a C here but a K in 1941 — and Gutman explains the falcon's origin dating back to the Crusades, Sam says, "Holy wars? I'll bet that was a great racket!" In a talented actor's hands, that could get a laugh. Coming out of Cortez's mouth, it drops like a lead balloon, but it's how he delivers every line whether he's making a threat, toying with cops or trying to seduce a woman. I don't think it's director Roy Del Ruth who is to blame, not that he ever made an exceptional piece of work, but Cortez in the 1931 Maltese Falcon gives us another example of how a bad lead can ruin an entire film. For a modern example, think Danny Huston in John Sayles' Silver City. Other things that make this film's Sam Spade ridiculous don't have anything to do with Cortez. When he gets the call about Miles' murder, his bedroom looks suitably seedy just as Sam's apartment does in 1941. However, when you see his plush living room, egad. The first thing it reminded me of was those ridiculously large Manhattan apartments the characters in the sitcom Friends somehow afforded. How does Sam Spade afford this nice a place in San Francisco even that long ago when Miss Wonderly's $200 payment was way more than they expected?

When he's meeting with Caspar Gutman (Dudley Digges) — for some reason Gutman's first name starts with a C here but a K in 1941 — and Gutman explains the falcon's origin dating back to the Crusades, Sam says, "Holy wars? I'll bet that was a great racket!" In a talented actor's hands, that could get a laugh. Coming out of Cortez's mouth, it drops like a lead balloon, but it's how he delivers every line whether he's making a threat, toying with cops or trying to seduce a woman. I don't think it's director Roy Del Ruth who is to blame, not that he ever made an exceptional piece of work, but Cortez in the 1931 Maltese Falcon gives us another example of how a bad lead can ruin an entire film. For a modern example, think Danny Huston in John Sayles' Silver City. Other things that make this film's Sam Spade ridiculous don't have anything to do with Cortez. When he gets the call about Miles' murder, his bedroom looks suitably seedy just as Sam's apartment does in 1941. However, when you see his plush living room, egad. The first thing it reminded me of was those ridiculously large Manhattan apartments the characters in the sitcom Friends somehow afforded. How does Sam Spade afford this nice a place in San Francisco even that long ago when Miss Wonderly's $200 payment was way more than they expected?

One thing I searched in vain to find on the Web was how old Miles Archer is supposed to be in Hammett's original story. In the 1941 version, there doesn't seem to be that much of an age discrepancy between Jerome Cowan and Bogart (In real life, Cowan was born in 1897, Bogart in 1899). However, Roy Del Ruth's version shows Miles (Walter Long) looking as if he has quite a few years on Sam (Long was born in 1879, Cortez in 1900). I was curious how Hammett wrote them, but could never find an answer. The closest I found was a character description on something that claimed to be the final version of John Huston's screenplay for the 1941 film where he writes that Miles is "about as many years past 40 as Spade is past 30." Iva's role increases in the 1931 version and in it, Miles knows that she and Sam had an affair, He returns early from a trip while Iva has called to whisper sweet nothings to Sam on the phone. When Effie steps away from her desk, Miles picks up her extension and overhears his wife and Sam's conversation. He never really gets a chance to confront them about it because when he goes into Sam's office, that's when Miss Wonderly has begun telling her story and she'll kill Miles soon enough. One thing doesn't change — both Sam Spades anxiously want the affair with Iva to be over. An interesting note about how Spade and Archer work in 1931: They shared an office in 1941 and were called private investigators. In 1931, each man has his own office and the sign on the outer office door refers to them as "Samuel Spade & Miles Archer: Private Operatives."

In most respects, the broad outlines of the story follows the tale most people know through the 1941 film. Many of the same lines are used, so they probably originated with Hammett, but they just don't get the same spin or aren't rewritten the way Huston did. Mostly, things get left out to make things go more quickly. We don't see Archer shot and killed and he doesn't tumble the way he does in 1941. Spade still receives the news in the dark of his bedroom, though it isn't filmed nearly as well as it was by Huston, and we don't see him call and

ask Effie to inform Iva. We only learn that she did that deed from the cops who confront Sam with that tidbit. Effie gets to score with some information of her own as well, telling Sam that Iva wasn't there when she got there, even if that is a red herring. For instance, the character of Wilmer doesn't appear until very late in the movie and doesn't get but a handful of lines, though he does kill Gutman offscreen as he does in the story which doesn't happen in the 1941 film. What's shocking about that is what a waste it is of the actor who plays Wilmer here — Dwight Frye, who in 1931 proves so memorable as Fritz in James Whale's Frankenstein and Renfield in Tod Browning's Dracula. Iva's increased role as a troublemaking sexpot went to an actress whose own life ended up as a bigger mystery than the one in The Maltese Falcon — Thelma Todd. In just 10 years, she appeared in an astounding 119 features and shorts, probably best known for her work with the Marx Brothers in Monkey Business and Horse Feathers. In 1935, she was found dead in her car, a victim of carbon monoxide poisoning but it was long rumored that she'd been murdered, especially by gangsters eager to force her and her boyfriend, director Roland West, out of ownership of their club.