Wednesday, July 17, 2013

What he really wanted to do was be an actor

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post is part of The Sydney Pollack Blogathon occurring through July 22 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie Lover

By Edward Copeland

For 40 years, from 1965 to 2005, Sydney Pollack directed 19 feature films. His last directing effort appeared as an installment of PBS' American Masters series on the architect Frank Gehry. Prior to that, he directed lots of episodic television. As Pollack reached the end of his life (and beyond it) he produced projects more than he directed and toward the end he also resumed the artistic endeavor where he started, acting more

and more often. When he ventured into show business, he aimed toward acting. His father hoped that Pollack would pursue a career in dentistry, but after catching the theater bug in high school in South Bend, Ind., he left for New York following graduation and studied with legendary acting teacher Sanford Meisner at Meisner's Neighborhood Playhouse (The same year he directed the American Masters special on Frank Gehry, he executive produce another episode of the series on Meisner). Eventually, he became an assistant to Meisner and even taught acting to others, though in a 2006 interview with Venice Magazine, Pollack resisted calling the technique he learned and passed on "The Method." "People call a lot of things 'The Method,' but there really isn’t one Method," Pollack said, "but it’s all derived from Stanislavsky. It’s all derived from Stanislavsky, but Stella Adler taught it different than Sandy Meisner and Strasberg taught it differently from both of them, and Harold Clurman taught it differently than the three of them, and Bobby Lewis took it in his own direction, as well. They each took The Moscow Art Theater of Stanislavsky and basic principles, and then developed their own approach. The goal was always the same: to find a way to analyze the construction of truthful behavior within imaginary circumstances."

and more often. When he ventured into show business, he aimed toward acting. His father hoped that Pollack would pursue a career in dentistry, but after catching the theater bug in high school in South Bend, Ind., he left for New York following graduation and studied with legendary acting teacher Sanford Meisner at Meisner's Neighborhood Playhouse (The same year he directed the American Masters special on Frank Gehry, he executive produce another episode of the series on Meisner). Eventually, he became an assistant to Meisner and even taught acting to others, though in a 2006 interview with Venice Magazine, Pollack resisted calling the technique he learned and passed on "The Method." "People call a lot of things 'The Method,' but there really isn’t one Method," Pollack said, "but it’s all derived from Stanislavsky. It’s all derived from Stanislavsky, but Stella Adler taught it different than Sandy Meisner and Strasberg taught it differently from both of them, and Harold Clurman taught it differently than the three of them, and Bobby Lewis took it in his own direction, as well. They each took The Moscow Art Theater of Stanislavsky and basic principles, and then developed their own approach. The goal was always the same: to find a way to analyze the construction of truthful behavior within imaginary circumstances."As he acted a lot in television of the 1950s, Pollack's interest turned to directing. While Pollack directed and produced some great and good films (my favorite being 1982's Tootsie, where he took his first substantial acting role since an episodic television appearance on a 1964 episode of the crime drama Brenner starring Edward Binns and James Broderick), after Tootsie, he acted or did voicework in more films and TV shows than his entire filmography. In many ways, I found Pollack more interesting at times as an actor than as a filmmaker, and that's where his career in the arts began, with his single Broadway role in 1955's The Dark Is Light Enough by Christopher Fry and starring Katharine Cornell, Tyrone Power and featuring Christopher Plummer.

Pollack began directing episodic television in 1961 and had ceased television acting in 1964 with that appearance on Brenner. As he jettisoned acting to concentrate on directing, he made a single movie: the 1962 Korean War drama War Hunt. The film starred John Saxon and Charles Aidman, but in addition to Pollack's supporting role, the movie offered appearances by Gavin MacLeod, Tom Skerritt and uncredited work by another future director, Francis Ford Coppola, as an Army truck driver. The biggest name among the ranks (at least he would be eventually) turned out to be a young Robert Redford. Pollack would direct Redford in seven films: This Property Is Condemned, Jeremiah Johnson, The Way We Were, Three Days of the Condor, The Electric Horseman, Out of Africa and Havana. Redford served as one of the producers of A Civil Action which featured Pollack in an acting role.

The headline at the top of this piece isn't quite true. Pollack return to acting in 1982's Tootsie (aside from a brief cameo in 1979's The Electric Horseman) proved to be quite a reluctant one. He already had cast Dabney Coleman to play George Fields, agent to prima donna/unemployed actor Michael Dorsey (Dustin Hoffman) but Hoffman pushed Pollack into taking the role himself, seeing the dynamic they had in their disagreements over the script. Pollack didn't want to leave Coleman in the cold so he cast him in the role of movie's fictional soap opera's director instead. Hoffman's instincts didn't fail him or the film as his scenes with Pollack provide many of the movie's comic highlights. You get that in the scene above, in the scene in the Russian Tea Room where Michael surprises George by showing up as his new alter ego Dorothy Michaels and, in perhaps my favorite scene between the two of them, when Michael shows up at George's home late one night to try to explain the romantic complications, including the fact that the father (Charles Durning) of the woman he loves (Jessica Lange) bought Dorothy an engagement ring. Forgetting for a moment what this all means, Pollack's reaction to news of the proposal comes off as priceless.

Following Tootsie, Pollack returned to the directing-producing track for a decade. During this decade he won his two Oscars for Out of Africa, but looking at the projects in that decade on which he worked solely as a producer or executive producer actually look more interesting than most of the movies he directed in that time. Some examples of his producing output from 1982 to 1991: Songwriter, The Fabulous Baker Boys, Presumed Innocent, White Palace, (surprisingly) King Ralph and Dead Again. With Tootsie, Pollack displayed a grounded, realistic comic side, but when 1992 arrived and he began to act up a storm, his range

widened, even if for the most part Pollack got pigeonholed as either a lawyer or a doctor, he played distinct members of each profession. Ten years after Tootsie, he managed roles in three films (and found time to executive produce two movies as well: HBO's A Private Matter and Leaving Normal, which had the misfortune of being too similar to Thelma & Louise and coming out a few months after the other film). The photo at the top of this post shows Pollack in his first 1992 role, Dick Mellon, business lawyer to besieged studio exec Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins) in Robert Altman's The Player. As Mellon, Pollack plays a no-nonsense Hollywood figure who has seen it all and never changes his vocal tone, no matter how serious the situation becomes, and doles out truisms such as in this exchange with Mill. "Rumors are always true. You know that," Mellon tells Mill. "I'm always the last to hear about them," Griffin sighs. "No, you're always the last one to believe them," Dick corrects his client. Pollack, as in the case of his casting in Tootsie, hadn't been the first choice of the director. Of course, Pollack had helmed Tootsie and opposed casting himself as George Fields. With The Player, Altman tried to cast as many of the character parts with lesser-known faces because his film contained so many star cameos and he wanted to avoid as much audience

widened, even if for the most part Pollack got pigeonholed as either a lawyer or a doctor, he played distinct members of each profession. Ten years after Tootsie, he managed roles in three films (and found time to executive produce two movies as well: HBO's A Private Matter and Leaving Normal, which had the misfortune of being too similar to Thelma & Louise and coming out a few months after the other film). The photo at the top of this post shows Pollack in his first 1992 role, Dick Mellon, business lawyer to besieged studio exec Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins) in Robert Altman's The Player. As Mellon, Pollack plays a no-nonsense Hollywood figure who has seen it all and never changes his vocal tone, no matter how serious the situation becomes, and doles out truisms such as in this exchange with Mill. "Rumors are always true. You know that," Mellon tells Mill. "I'm always the last to hear about them," Griffin sighs. "No, you're always the last one to believe them," Dick corrects his client. Pollack, as in the case of his casting in Tootsie, hadn't been the first choice of the director. Of course, Pollack had helmed Tootsie and opposed casting himself as George Fields. With The Player, Altman tried to cast as many of the character parts with lesser-known faces because his film contained so many star cameos and he wanted to avoid as much audience confusion as possible. Initially, Altman sought writer-director Blake Edwards, who also started his career as an actor, though he hadn't appeared on screen since 1948, for the part of Mellon, but it didn't work out and he went with Pollack, who only had that one role in Tootsie in 30 years. While The Player offers darker, satirical laughs than Tootsie did and Pollack doesn't get the laughs out of Dick Mellon that he did out of George Fields, he garnered more laughs in his most dramatic, deepest film role yet as Jack, the divorcing best friend of Gabe Roth (Woody Allen) in Husbands and Wives. I wasn't as crazy about the film as others, but Pollack delivered one of his greatest acting jobs, ranging from the at-ease midlife divorced man finding renewed vigor with a twentysomething aerobics instructor (Lysette Anthony) and then turning downright nasty on her at a party when she doesn't meet his standards for intellectual heft. He literally drags her from the soiree and tosses her toward his car, accusing her of being an "infant." It's a scary side of Pollack that we'll see more of in other roles. His third on-screen role of 1992 didn't receive a credit, but the cameo in Death Becomes Her provides what could be Pollack's funniest moments as an ER doctor examining Meryl Streep. The clip below leaves out his character's final punch line.

confusion as possible. Initially, Altman sought writer-director Blake Edwards, who also started his career as an actor, though he hadn't appeared on screen since 1948, for the part of Mellon, but it didn't work out and he went with Pollack, who only had that one role in Tootsie in 30 years. While The Player offers darker, satirical laughs than Tootsie did and Pollack doesn't get the laughs out of Dick Mellon that he did out of George Fields, he garnered more laughs in his most dramatic, deepest film role yet as Jack, the divorcing best friend of Gabe Roth (Woody Allen) in Husbands and Wives. I wasn't as crazy about the film as others, but Pollack delivered one of his greatest acting jobs, ranging from the at-ease midlife divorced man finding renewed vigor with a twentysomething aerobics instructor (Lysette Anthony) and then turning downright nasty on her at a party when she doesn't meet his standards for intellectual heft. He literally drags her from the soiree and tosses her toward his car, accusing her of being an "infant." It's a scary side of Pollack that we'll see more of in other roles. His third on-screen role of 1992 didn't receive a credit, but the cameo in Death Becomes Her provides what could be Pollack's funniest moments as an ER doctor examining Meryl Streep. The clip below leaves out his character's final punch line.Until his death from cancer in May 2008, seeing Pollack act became a much more common sight than spotting his directing credit. He turned up in legal entanglements again in films such as A Civil Action, Michael Clayton and Changing Lanes. He guided Tom Cruise into the sexual netherworld of the rich and powerful in Stanley Kubrick's final film, Eyes Wide Shut. He took roles in the last two films he directed, Random Hearts and The Interpreter. Pollack even provided the voice for the studio executive in The Majestic and the French film Avenue Montaigne. His final film role was in the romantic comedy Made of Honor where he played the father of the male maid of honor (Patrick Dempsey). On television, he did more voice work on comedies such as Frasier and King of the Hill. He also played a doctor on an episode of Mad About You and had a recurring role as Will's father on Will & Grace. He even played himself on an episode of Entourage, his last TV or movie appearance. Of all his late appearances though, the one that stands out to me also came in 2007 and put him in the role of another doctor. In the batch of the last nine episodes of The Sopranos, Pollack played jailed oncologist Warren Feldman, incarcerated with the dying Johnny Sac (Vincent Curatola) in the great episode "Stage 5." This scene I believe gives a great example of how talented Pollack truly could be as an actor.

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Blake Edwards, Coppola, Cruise, Dabney Coleman, Durning, Dustin Hoffman, J. Lange, Kubrick, Plummer, Redford, Streep, Sydney Pollack, The Sopranos, Tim Robbins, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

Different ways of playing 'Cards'

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post contains spoilers for the three segment British miniseries House of Cards from the 1990s starring Ian Richardson and this year's 13-episode U.S. version made for Netflix, produced by David Fincher and starring Kevin Spacey. If you plan to watch either version and haven't yet, read no further.

By Edward Copeland

After giving people time to watch the American version of House of Cards and with its availability on DVD and Blu-ray for those without access to Netflix Instant, I thought enough time had transpired to discuss both the new version as well as the original BBC miniseries, whose first part premiered in 1990. Prior to watching the David Fincher-produced D.C.-set House of Cards with Kevin Spacey playing the wily lead, I felt I needed to see the British version to see how well the differences translated. (Obviously, Britain's parliamentary system of government works quite differently from our legislative branch — which, in its current state, doesn't work at all, but House of Cards exists in the land of make-believe. I lacked either the time or the energy given personal matters to attempt to read the novel by Michael Dobbs that spawned the BBC miniseries.)

Though the new version pads out its story to 13 roughly one-hour episodes while the first of the three British House of Cards miniseries told mostly the same story in four episodes of approximately the same length, the U.S. take does hit many of the same plot points except when it comes to the ending, but the makers of the U.S. House of Cards envision it as a continuing series. (I needn't have watched the second and third BBC miniseries, To Play the King and The Final Cut, since the stories in those sequels aren't covered in the first season of the U.S. House of Cards.) Both versions of the political chicanery, whether set here or across the pond, offer solid entertainment and mostly solid performances, though the U.S. House of Cards wins out in terms of production values. Unfortunately, when it comes to the battle of FUs (Francis Urquhart in the U.K., Francis Underwood in the U.S.), the late Ian Richardson wins hands down. Spacey proves capable as usual for the most part, but he burdens himself with an off-and-on Southern drawl that's wholly unnecessary and, at times, a major distraction. When Richardson's Urquhart speaks to the viewer in his well-mannered, upper-crust tone, it always works. When Spacey's Underwood attempts to pull it off while simultaneously putting on a generic son of the South voice for his South Carolina representative, at times it comes off as too cutesy by half.

Despite the differences in forms of government, both House of Cards begin with essentially the same kernel of a motivation for our two Francises. In the 1990 BBC version, Urquhart has served faithfully as an MP of the Conservative Party, functioning as their Chief Whip under Margaret Thatcher's reign as prime minister. In its fictionalized view of history, Thatcher's loss of support has led to her resignation and while the Conservatives look bound to keep a weakened majority hold of the British government, Urquhart expects

the new prime minister, Hal Collinridge (David Lyon, whose death at 72 was announced today), to appoint him to a long-sought Cabinet position and remove him from his duties as whip. Instead, with the slimmer majority, Collinridge decides not to shake up the Cabinet and an angry Urquhart starts maneuvering many people to get his revenge and build his own rise to power. In the 2013 U.S. take on the tale, Underwood long has held the title of Democratic Whip in the House, now the Majority Whip as a new Democratic president (not Barack Obama), Garrett Walker (Michael Gill), takes office. but Walker reneges on a promise to pick Underwood as his secretary of state. This begins Underwood's convoluted maneuvering. One problem that separates the two versions comes down to logic. You see why Urquhart longs to become the prime minister himself, but if you know U.S. history, it seems downright silly for Underwood to leap through all the hoops and commit all the deeds he does just to end up as vice president. When George H.W. Bush won the presidency, he was the first sitting vice president to manage the victory in his own right since Martin Van Buren. Unless Underwood plans to kill off Walker in a subsequent season of the U.S. House of Cards, why does he see that as a plausible path to the Oval Office?

the new prime minister, Hal Collinridge (David Lyon, whose death at 72 was announced today), to appoint him to a long-sought Cabinet position and remove him from his duties as whip. Instead, with the slimmer majority, Collinridge decides not to shake up the Cabinet and an angry Urquhart starts maneuvering many people to get his revenge and build his own rise to power. In the 2013 U.S. take on the tale, Underwood long has held the title of Democratic Whip in the House, now the Majority Whip as a new Democratic president (not Barack Obama), Garrett Walker (Michael Gill), takes office. but Walker reneges on a promise to pick Underwood as his secretary of state. This begins Underwood's convoluted maneuvering. One problem that separates the two versions comes down to logic. You see why Urquhart longs to become the prime minister himself, but if you know U.S. history, it seems downright silly for Underwood to leap through all the hoops and commit all the deeds he does just to end up as vice president. When George H.W. Bush won the presidency, he was the first sitting vice president to manage the victory in his own right since Martin Van Buren. Unless Underwood plans to kill off Walker in a subsequent season of the U.S. House of Cards, why does he see that as a plausible path to the Oval Office?

What delineates our two Francises (the U.S. version only uses the FU joke once as its expected, vulgar stand-in by some of Underwood's opponents while the BBC call Urquhart FU frequently and affectionately by both friends and foes to his face without a hit of a double meaning) most distinctly comes from the difference in the way Spacey acts the words by Beau Willmon and his writing staff and Richardson's delivery of Andrew Davies' dialogue. Almost everyone appears to be on to what Frank Underwood conspires to do at all times, even if his machinations win in the end since Spacey doesn't take much of an effort to hide his moves from those he attempts to manipulate. In contrast, it takes some time for people to catch on to the lengths that Francis Urquhart will go to to accomplish his means thanks to Richardson's performance, which he keeps close to his vest. Both versions rely on the conceit that the Francises speak in asides to the television viewer about what they think and plan, only Spacey talks to audiences in the same basic tone as most of the other characters. Richardson confides to us, letting us in on secrets that others aren't aware of and it makes his performance much richer and, given the late actor's training, provides Francis Urquhart with an almost Shakespearean air. Urquhart picks off opponents with a variety of means and accomplishes most of this without leaving any fingerprints. The game plan in the U.S. House of Cards differs slightly as no list of vice presidential contenders stand in Underwood's way, but they do match in terms of subject matter. Urquhart must sink health and education ministers while those two issues become legislative hurdles that play a part in Underwood's climb.

Both House of Cards include two main women in the lives of their protagonists: their wives and young reporters who become the pols' lovers as well as their tool to help advance their plots. The idea of the female journalist follows fairly closely in both versions (except where they end up in the first installment and the level of their naïveté). In the BBC, the young reporter Mattie Storin (Susannah Harker) takes a long time (too long for her sake) to catch on to Urquhart's true nature and their illicit romance takes on a somewhat twisted father figure complex where the young Mattie tends to call the much older Francis "Daddy" during their dalliances. In the U.S. version, the young woman journalist Zoe Barnes (Kate Mara) contains a much more ambitious nature and she uses Underwood as much as he uses her. Both Mattie and Zoe do make colleagues jealous with their scoops and end up booted from their newspapers, only the U.S. version updates for technological changes and makes Zoe's success come via instant blog posts and finds her gaining new employment with an online political publication. Probably due to the way Mattie is written, Harker comes off as a weaker actress than Mara, who has a more fully developed character. The bigger difference presents itself in the portrayal

of the political wives. Elizabeth Urquhart (Diane Fletcher) truly serves as her husband's partner-in-crime. She knows of his affair with Mattie (and other women in the later installments) but approves wholeheartedly because she knows that letting him have his extracurricular activity with Mattie only serves the couple's ultimate goal and doesn't pose a threat to her position. Claire Underwood (Robin Wright) begins that way early in the U.S. House of Cards, but as the series develops she exhibits jealousy. showing up at Zoe's apartment, interfering with part of Underwood's legislative agenda and even leaving D.C. to renew an affair with a former lover, a famous photographer (Ben Daniels). Presumably, the part required beefing up in order to get someone of Wright's caliber to agree to accept it in the first place. Claire also gets her own sideline with story strands involving the charitable foundation that she runs whereas Elizabeth Urquhart basically serves as Francis' adornment at party and sounding board at home but little else.

of the political wives. Elizabeth Urquhart (Diane Fletcher) truly serves as her husband's partner-in-crime. She knows of his affair with Mattie (and other women in the later installments) but approves wholeheartedly because she knows that letting him have his extracurricular activity with Mattie only serves the couple's ultimate goal and doesn't pose a threat to her position. Claire Underwood (Robin Wright) begins that way early in the U.S. House of Cards, but as the series develops she exhibits jealousy. showing up at Zoe's apartment, interfering with part of Underwood's legislative agenda and even leaving D.C. to renew an affair with a former lover, a famous photographer (Ben Daniels). Presumably, the part required beefing up in order to get someone of Wright's caliber to agree to accept it in the first place. Claire also gets her own sideline with story strands involving the charitable foundation that she runs whereas Elizabeth Urquhart basically serves as Francis' adornment at party and sounding board at home but little else.Both versions equip our FUs with henchmen named Stamper to help him carry out the more unseemly parts of his schemes, though the portrayals as well as the job titles come off quite differently in each country. In England, Urquhart's underling, Tim Stamper, comes across as quite a weasel in the hands of actor Colin

Jeavons. Tim Stamper functions as the Assistant Whip for the Conservatives in the House of Commons until Urquhart succeeds at ascending to the position of prime minister and Stamper moves up to Chief Whip. Later, unhappily, Urquhart moves him to the post party chairman. The British Stamper not only gets his hands dirty with delight, he also overflows with ambition himself and it costs him in the end (part of which may have been necessitated by Jeavons' decision to retire from acting after completing the second installment, To Play the King). The American Stamper gets a new first name — Doug — and does show signs of conscience even while he performs Underwood's errands. Doug Stamper serves as the House Majority Whip's chief of staff and holds no elected position. Michael Kelly, who most people will recognize him from many roles on television and in film, doesn't get down and dirty with the same glee that Jeavons does, but Kelly creates a different persona and plays him well. Odds are, depending how many seasons House of Cards continues, Doug Stamper either will turn on his boss or become a liability to him.

Jeavons. Tim Stamper functions as the Assistant Whip for the Conservatives in the House of Commons until Urquhart succeeds at ascending to the position of prime minister and Stamper moves up to Chief Whip. Later, unhappily, Urquhart moves him to the post party chairman. The British Stamper not only gets his hands dirty with delight, he also overflows with ambition himself and it costs him in the end (part of which may have been necessitated by Jeavons' decision to retire from acting after completing the second installment, To Play the King). The American Stamper gets a new first name — Doug — and does show signs of conscience even while he performs Underwood's errands. Doug Stamper serves as the House Majority Whip's chief of staff and holds no elected position. Michael Kelly, who most people will recognize him from many roles on television and in film, doesn't get down and dirty with the same glee that Jeavons does, but Kelly creates a different persona and plays him well. Odds are, depending how many seasons House of Cards continues, Doug Stamper either will turn on his boss or become a liability to him.

The one area besides production design where the U.S. House of Cards bests the British original comes from the actor who portrays Underwood's actual victim and how the U.S. version fleshes out his character in the first place. Before I began this piece, I issued a spoiler warning, but the U.S. House of Cards doesn't make it a secret that Underwood's deviousness takes a lethal turn, thanks to some of its promotional posters, and the very first sequence of the series gives viewers that impression by showing Underwood putting an injured dog out of its misery with his bare hands but making it clear that he isn't doing it to be merciful. In the British take, even though the first installment only consists of four 1-hour installments, it doesn't

let the audience know that Urquhart's manipulations include murder. In the BBC version, the first life that Urquhart literally takes with his own hand belongs to Roger O'Neill (Miles Anderson), the P.R. consultant for the Conservative Party whom Urquhart gets to use his girlfriend, Penny Guy (Alphonsia Emmanuel), to seduce Foreign Secretary Patrick Woolton (Malcolm Tierney), one of Urquhart's competitors for the prime minister post. Unfortunately, O'Neill loves Penny as much as he loves cocaine and when she dumps him when she realizes O'Neill used her, O'Neill becomes a wild card that Urquhart can't trust. To make sure nothing comes out that damages FU's plan and reveals his role in the Woolton revelation, Urquhart spikes O'Neill's coke supply with rat poison, assuring Mattie who figures out he did it that he was just putting O'Neill out of his misery.

let the audience know that Urquhart's manipulations include murder. In the BBC version, the first life that Urquhart literally takes with his own hand belongs to Roger O'Neill (Miles Anderson), the P.R. consultant for the Conservative Party whom Urquhart gets to use his girlfriend, Penny Guy (Alphonsia Emmanuel), to seduce Foreign Secretary Patrick Woolton (Malcolm Tierney), one of Urquhart's competitors for the prime minister post. Unfortunately, O'Neill loves Penny as much as he loves cocaine and when she dumps him when she realizes O'Neill used her, O'Neill becomes a wild card that Urquhart can't trust. To make sure nothing comes out that damages FU's plan and reveals his role in the Woolton revelation, Urquhart spikes O'Neill's coke supply with rat poison, assuring Mattie who figures out he did it that he was just putting O'Neill out of his misery.Overall, the American ensemble beats the British one. Granted, the U.S. version provides nine extra hours to fill with juicy parts for actors to the BBC's mere four, so the original lacks the room to develop many characters in depth so it's easy to see how Ian Richardson steals the show. Kevin Spacey, in addition to his aforementioned accent problem, shares time with a lot of great performers in parts large and small. On top of those mentioned already, Sebastian Arcelus, Reg E. Cathey, Kathleen Chalfant, Nathan Darrow, Sandrine Holt, Boris McGiver, Larry Pine, Al Sapienza, Constance Zimmer and Gerald McRaney all put in appearances. We also get three actors familiar to Treme fans in parts of various scope: Mahershala Ali, Lance E. Nichols and Dan Ziskie. The M.V.P. of the entire cast though turns out to be Corey Stoll, so great as Hemingway in

Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris, as the U.S. equivalent of Roger O'Neill. Instead of a P.R. guy, Stoll plays Pennsylvania Rep. Peter Russo, a divorced father of two with a penchant for drugs, booze and sex, despite his deep feelings for and relationship with his chief of staff Christina Gallagher (Kristen Connolly). For those who only know Stoll from Midnight in Paris, he'll be unrecognizable. In the short number of episodes though, he takes Russo through the largest journey of any character in the series, battling to sobriety and attempting to believe in himself, unaware of his status as a pawn in Underwood's game (both Underwoods, actually), until it's too late. Stoll makes Russo the only character that the audience develops any sympathy for at all. Though Russo behaves badly, his mistakes all flow from his personal weaknesses. He doesn't do things maliciously the way that Underwood and other characters do. When he commits wrongs, it's because he can't control himself. Underwood always stays in control, even if unexpected events force him to improvise. You feel bad for Russo when he can't

Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris, as the U.S. equivalent of Roger O'Neill. Instead of a P.R. guy, Stoll plays Pennsylvania Rep. Peter Russo, a divorced father of two with a penchant for drugs, booze and sex, despite his deep feelings for and relationship with his chief of staff Christina Gallagher (Kristen Connolly). For those who only know Stoll from Midnight in Paris, he'll be unrecognizable. In the short number of episodes though, he takes Russo through the largest journey of any character in the series, battling to sobriety and attempting to believe in himself, unaware of his status as a pawn in Underwood's game (both Underwoods, actually), until it's too late. Stoll makes Russo the only character that the audience develops any sympathy for at all. Though Russo behaves badly, his mistakes all flow from his personal weaknesses. He doesn't do things maliciously the way that Underwood and other characters do. When he commits wrongs, it's because he can't control himself. Underwood always stays in control, even if unexpected events force him to improvise. You feel bad for Russo when he can't stand up for himself and acts against his own interests and those of his constituents, just to be Underwood's toady and pay him back for covering up an incident when he got caught drunk with a prostitute. You get a sense of where this comes from a in a couple of brief scenes involving Russo and his hospitalized mother (a great Phyllis Somerville) that gives you insight into Russo and makes you feel sorry for the man at the same time it provides some wickedly dark humor. When he begins to turn himself around, you develop a rooting interest for him to succeed (even though having seen the U.K. version first, I figured what fate awaited Russo, though the U.S. changes the manner of his inevitable death at Underwood's hands slightly differently). Though the U.S. House of Cards contains a lot of great acting, no one comes close to turning in a performance as wonderful as Stoll's and no character gets as much development and detail as Rep. Peter Russo.

stand up for himself and acts against his own interests and those of his constituents, just to be Underwood's toady and pay him back for covering up an incident when he got caught drunk with a prostitute. You get a sense of where this comes from a in a couple of brief scenes involving Russo and his hospitalized mother (a great Phyllis Somerville) that gives you insight into Russo and makes you feel sorry for the man at the same time it provides some wickedly dark humor. When he begins to turn himself around, you develop a rooting interest for him to succeed (even though having seen the U.K. version first, I figured what fate awaited Russo, though the U.S. changes the manner of his inevitable death at Underwood's hands slightly differently). Though the U.S. House of Cards contains a lot of great acting, no one comes close to turning in a performance as wonderful as Stoll's and no character gets as much development and detail as Rep. Peter Russo.Since the British House of Cards only ran four hours, it had a sole director, Paul Seed, and writer, Andrew Davies. Davies and Seed returned to the same roles on the second installment, To Play the King, but Seed's directing work consists almost entirely of British television. Davies wrote the third and final part, The Final Cut, but Mike Vardy took over helming duties. Similarly, his directing work stayed restricted to British TV. Davies' writing extends to film including the screenplays for Circle of Friends, Emma, The Tailor of Panama, Bridget Jones's Diary, the 2008 feature of Brideshead Revisited and the 2011 version of The Three Musketeers directed by Paul W.S. Anderson.

While Beau Willmon had a hand in writing most of the U.S. episodes, he also had a staff of writers who either contributed or turned in their own episodes. On the directing side, Fincher started the series off by directing the first two episodes while James Foley directed the most at 4 episodes and Allen Coulter, Carl Franklin, Charles McDougall and Joel Schumacher helmed two each.

In the final assessment, the U.S. House of Cards moves fairly well except at times when it feels as if it stuffed itself with too many character and plot strands and an episode set at Underwood's reunion at The Citadel that, while OK, feels and plays like filler. The U.K. House of Cards comes off as far more efficient, even if most of the characters aside from Richardson's Urquhart prove far less compelling. In the second and third parts, they do at least give him actual adversaries, which make things slightly more interesting, but in the end all the British House of Cards episodes always belong to the great Richardson and his rich and delicious

performance. One really bizarre viewing experience for me came from the miniseries — which aired in 1990, 1995 and 1996 — incorporating Margaret Thatcher's fictional death. She died in the miniseries as I watched it before she died in real life earlier this year. Part of the subtext is that Francis Urquhart wants to break Thatcher's record for serving as prime minister longer in the post-WW2 era. One other thing that makes the British version slightly better than the American take is that the first installment ends with a great cliffhanger mystery that plays out over the course of the next two parts. The new House of Cards leaves us with reporters hot on Underwood's trail about Russo's "suicide," but it doesn't come off nearly as intriguing as the British version. I'm also curious where the U.S. version goes next. It obviously can't follow the storyline of the British To Play the King since we don't have a constitutional monarch and a newly sworn in Vice President Underwood wouldn't run into conflict with a recently crowned king. Presumably, that tension will present itself with his new boss, President Walker. It's a shame that Ian Richardson isn't with us anymore and that the third British House of Cards installment resolved the Francis Urquhart character. It might have been fun to see U.S. President Francis Underwood face off against British Prime Minister Francis Urquhart. I'd probably root for Urquhart, if only because he doesn't have that corny and awful Southern accent.

performance. One really bizarre viewing experience for me came from the miniseries — which aired in 1990, 1995 and 1996 — incorporating Margaret Thatcher's fictional death. She died in the miniseries as I watched it before she died in real life earlier this year. Part of the subtext is that Francis Urquhart wants to break Thatcher's record for serving as prime minister longer in the post-WW2 era. One other thing that makes the British version slightly better than the American take is that the first installment ends with a great cliffhanger mystery that plays out over the course of the next two parts. The new House of Cards leaves us with reporters hot on Underwood's trail about Russo's "suicide," but it doesn't come off nearly as intriguing as the British version. I'm also curious where the U.S. version goes next. It obviously can't follow the storyline of the British To Play the King since we don't have a constitutional monarch and a newly sworn in Vice President Underwood wouldn't run into conflict with a recently crowned king. Presumably, that tension will present itself with his new boss, President Walker. It's a shame that Ian Richardson isn't with us anymore and that the third British House of Cards installment resolved the Francis Urquhart character. It might have been fun to see U.S. President Francis Underwood face off against British Prime Minister Francis Urquhart. I'd probably root for Urquhart, if only because he doesn't have that corny and awful Southern accent.Tweet

Labels: 10s, 90s, Books, Fiction, Fincher, Hemingway, Netflix, Robin Wright, Shakespeare, Spacey, Television, Treme, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, August 03, 2012

Edward Copeland's Top 100 of 2012 (40-21)

Fritz Lang made a lot of good movies, but nothing equaled this tale told in his native language. Peter Lorre made his mark as the hunted child killer in a film filled with atmosphere, suspense and thought.

Kept from the public for years after its initial release, the one plus to its exile was that I experienced this masterpiece of a political thriller — 50 years old this year — for the first time on the big screen in a crisp, black-and-white print. I hope that Jonathan Demme’s misguided idea of trying to remake this classic didn’t sour the original or scare younger viewers away from seeking out Frankenheimer’s version. The 1962 Manchurian Candidate contains many attributes that make it worth recommending, but every film lover must witness Angela Lansbury’s portrayal of Mrs. Iselin, a contender for the top 10 screen villains of all time.

My much-missed dog Leland Palmer Copeland didn’t usually watch TV, but whenever this classic came on, she was drawn to it. One time, Leland even seemed to sit on the couch and watch it from beginning to end. Maybe it was the music, maybe it was the colors. The sad side effect of Leland’s affection for this film that no one truly ever outgrows is that now that she isn’t here to watch it Dorothy and her friends with me any longer, Oz sometimes proves too painful for me to revisit.

No one gives this film the credit for its darkness that it really deserves. This isn't sappy sentimental drivel; this is about a man who feels as if he's been pissed on all his life and finally reaches the end of his rope. James Stewart's talent, Capra's gifts and the script by Frances Goodrich & Albert Hackett make George Bailey's journey plausible and touching. Only a Mr. Potter could hate this film.

Howard Hawks directed John Wayne to his second-greatest performance in this thrilling tale of a cattle drive and bitter rivalries. It also contains the perfect example of a Hawksian woman as Joanne Dru keeps talking, even with an arrow protruding from her body. I feel as if Hawks has slipped some in esteem among the old masters as far as the younger critics out there go. This master of nearly all genres seems long overdue for resurgence.

I wrote in my 2007 list that The Graduate and Bonnie and Clyde constantly swap slots for my choice as the best film of 1967 and damn if they haven’t done it again five years later. One of the many great lines in 2009’s (500) Days of Summer comes when the narrator, in describing Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s character, says that an early exposure to sad British pop music and a misreading of The Graduate led him to believe that the search for love always leads to The One. (If I’m still around to make another top 100 in 2019, I suspect you’ll find (500) Days of Summer there — after multiple viewings I believe it’s the 21st century Annie Hall.) Back to The Graduate itself, Nichols’ direction looks better with each viewing and the cast remains remarkable. It’s just that my reaction to the story itself that waxes and wanes. It’s never bad – it’s just that sometimes I find myself loving it a bit less than the last time.

The history of movies doesn’t lack for great teamings of directors and actors and the man who more or less made John Wayne an icon with the way he introduced him as The Ringo Kid in Stagecoach also directed the Duke to his best acting performance here. Wayne always worked as a good guy, but he proved his acting chops when someone inserted an element of darkness into his characters. The Searchers also has proved to be a useful template for many other films, most notably Taxi Driver and Paul Schrader’s Hardcore. Ford brought a lot of great imagery to this story and it arguably contains the greatest closing shot of his long career.

As I foretold a couple notches back when writing about The Graduate, Bonnie and Clyde holds the higher esteem in my heart in this snapshot in time. Perhaps it’s a side effect of the journey I took through Penn’s entire filmography following his death, but it’s a great film regardless. Each time I watch it again I become more convinced — harrowing moments of violence aside — this truly plays as much as a comedy as The Graduate. At the time I re-visited it, watching how the Depression-era bank robbers became folk heroes to the masses, the resonance with the destruction 21st century Wall Street bankers wreaked on our nation’s economy was easier to identify with than ever before.

In the 1927-28 contest for "Artistic Quality of Production" at the Oscars, this film faced off against Sunrise and Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness. While Sunrise won and I wouldn’t argue against its status as a superb film (It’s not that far back on this list after all), I admit to preferring Vidor's film and its tale of striving to succeed as everything in the world appears to conspire to keep you down.

There's a good reason that so many cite Robert Towne's screenplay as one of the great examples of writing for film. If only all scripts (including some of Towne’s) were this superb. It remains one of the best examples of a modern noir, filmed in color, as well as Polanski’s best work. Jack Nicholson’s Jake Gittes came in his unbelievable and unforgettable run of great 1970s performances that began with 1969’s Easy Rider. It also gives us one of the sickest screen villains in Noah Cross, played so well by John Huston. Chinatown always will live on in the pantheon of film’s with last lines so memorable even people who’ve never seen it know the words.

You know 1950 was a great year for movies released in the United States when a picture as great as All About Eve only finishes third on my list for that year (behind The Third Man and Sunset Blvd.). That takes nothing away from All About Eve though with its brittle and brilliant dialogue and multiple great performances, including Bette Davis’ best, Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter and, most especially, George Sanders as Addison DeWitt.

Death comes in large doses in The Wild Bunch, but its violence, despite Peckinpah turning the carnage into quasi-ballet-like imagery, isn’t what makes the film so remarkable. The film delivers its true eulogy not for its human characters but for the death of an era and a way of life. As with so many of Peckinpah’s great films, too many misunderstood the film’s intent but The Wild Bunch only grows more evocative and timeless with age, thanks in large part to its ensemble of acting veterans who display the film’s themes through every crease and line on their faces. With the recent death of Ernest Borgnine, Jaime Sanchez (Angel) remains the last living actor who belonged to the bunch.

Billy Wilder (like Howard Hawks) had the talent to soar in almost any genre and this quintessential film noir is a supreme example. How it lost the Oscar to Going My Way and Fred MacMurray and Edward G. Robinson failed to get nominations still puzzles me. Wait — no it doesn't. The Academy picks wrong much more often than they pick right. Barbara Stanwyck gave a lot of great performances, but Phyllis Dietrichson may have topped them all — and if she didn’t, the others better look out.

Kurosawa gets routinely mentioned by many as a master (and deservedly so), thanks mainly to his great sword-laden epics, but for me this "modern" film stands high as one of his strongest, telling the sad story of a long suffering bureaucrat who seeks meaning in life when he's diagnosed with terminal cancer. A truly touching, remarkable film.

Has there ever been a more touching image placed on film that the ending of this silent film, made well after silent films were dead, when the newly sighted blind girl realizes her benefactor was a little tramp? I don't think so either.

The film that marked Woody’s leap from pure comedy to something more still stands as one of his very best 35 years later. With a structure that deserves comparisons to Citizen Kane in that you’re never quite sure what comes next that guarantees a perpetual freshness no matter how many times you’ve seen it. Allen threw almost every trick he could think of into Annie Hall — animated sequences, subtitles to translate what characters really thought, split screens (even if they actually filmed scenes in a room with a divider — and produced an instant classic. Diane Keaton delights as the title character, the film overflows with priceless lines and timeless sequences and the first great Christopher Walken monologue.

It's almost become shorthand to argue that Part II bests Part I in The Godfather trilogy, but I disagree. The original still takes the top spot in my book. I don't think the crosscutting of Michael and young Vito ever quite meshes and instead interrupts the rhythm of Part II. No such problem in the original, an example of making a movie masterpiece out of a pulpy novel. Examining the film more closely again earlier this year for its 40th anniversary while I enjoyed and admired it as much as ever, for the first time I had to acknowledge that unlike later mob classics such as Goodfellas or TV’s Sopranos, The Godfather does romanticize the Corleones. You never see innocents suffer from their line of work — Vito even denies they’re killers. It doesn’t change the film’s status as a fine piece of cinematic art, but it did make me think harder about it than I had before.

Many directors deliver great one-two punches in terms of brilliant consecutive films and Lumet pulled off one of the best of them in 1975 and 1976, beginning with this masterpiece based on a true bank robbery. Al Pacino delivers what may be one of his top two or three performances. It also contains the best work of the sadly too brief career of John Cazale and a peerless ensemble. Lumet’s direction aided by the editing of Dede Allen produced one of the most re-watchable films of all time. If I run across it on TV, even cut up, I stay glued to the end.

After more than 70 years, John Huston’s directing debut still sizzles. Watching Bogart embrace his first real role as a good guy exhilarates the viewer as he thrusts and parries with the delightful supporting cast of Mary Astor, Ward Bond, Elisha Cook Jr., Gladys George, Sydney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre, Barton McClane and Lee Patrick. What many forget about the film comes in that unforgettable climax that basically consists of five characters talking to each other for nearly 30 minutes — and it’s riveting.

The film that really put Spielberg on the pop culture map remains to me his greatest accomplishment. Two distinct and perfect halves: Terror on the beach followed by the brilliance of three men on a boat. It's also an example of how sometimes trashy novels can be turned into true works of film art in a way great novels usually miss the mark in translation (though Peter Benchley's novel at least killed Hooper off as well leaving nonexpert waterphobe Brody as the victor and sole survivor, which would have made for a slightly better ending but I'm nitpicking).

Tweet

Labels: Arthur Penn, Capra, Chaplin, Coppola, Hawks, John Ford, kinpah, Kurosawa, Lang, Lists, Lumet, Mankiewicz, Nichols, Polanski, Schrader, Spielberg, Towne, Wilder, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Edward Copeland's Top 100 of 2012 (20-1)

Charlie Chaplin was audacious enough to continue making silent films (although he did allow for sound effects and an occasional song) all the way to 1936. In my opinion, he saved the Little Tramp's best for last in this hysterical tale of man vs. the modern age. The comedy is as funny as you'd expect and even more pointed than usual. Since Chaplin knew the Little Tramp was making his swan song, he even let him waddle off into the sunrise. Sound didn't stop Chaplin, who had two great sound efforts to come with The Great Dictator and Monsieur Verdoux. Still, his early works are the most precious gifts. Truly, his silence was golden.

When compiling the 2007 list, I feared it was becoming too Hitchcock-centric, forcing the omission of other great filmmakers but dammit, he made so many films that mean so much to me, it would be dishonest to place a quota on him. In the intervening five years, seeing Strangers several more times only has lifted it in my extreme. Hitch's directing gifts come off at his most stylish and Robert Walker's wondrous performance as the sensitive sociopath Bruno who expects the wimpy Farley Granger to live up to his part of a hypothetical murder deal remains chilling (and darkly funny) to this day. One of the biggest leaps from the last list.

Buster Keaton always shares the title with Charlie Chaplin as one of the two great silent clowns and The General continues to be Keaton’s masterpiece 85 years later. However, while it doesn’t lack for laughs, the film more accurately could be called an adventure than a comedy. The realism of the film’s Civil War setting also proves quite striking and even though Keaton’s character Johnny Gray fights for the Confederacy against the Union, neither side comes off as particularly villainous and the film doesn’t contain the racist elements of something like Birth of a Nation. The film’s humor stems from Johnny’s two loves: his train and the woman he longs for who won’t love him until he joins the war effort, even though he’s been rejected as a fighter because of his skills as an engineer. The General never grows old.

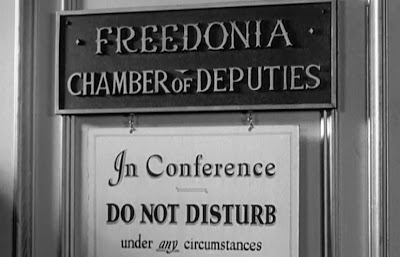

When Mickey (Woody Allen), depressed and suicidal, wanders into a movie theater in Hannah and Her Sisters, it's this inspired mixture of lunacy that brings him back around. After all, who can sit through Duck Soup and not feel better afterward. The question as to which Marx Brothers vehicle was the best got settled a long time ago and Duck Soup won. With its classic mirror scene and the loosest of plots designed to make the insanity of war look even crazier, I never get tired of Duck Soup. Watch it if only for the great Margaret Dumont. Remember, you are fighting for her honor, which is more than she ever did.

As a journalist, His Girl Friday contains one of my favorite nonsequiturs in the history of film. Delivered with frantic panache by Cary Grant as unscrupulous newspaper editor Walter Burns: "Leave the rooster story alone. That's human interest." Oh yeah, this may also be one of the funniest films ever made with rapid fire dialogue, a great sparring partner for Grant in Rosalind Russell and a priceless supporting cast to boot. It's the best remake ever made (and the film it was based on, The Front Page, is pretty damn good too). Making Hildy Johnson a woman and Burns' ex-wife was a stroke of genius. Besides, when you watch any version of this story where Walter and Hildy are both men, it's clear this isn't a platonic working relationship. I don't advise any more remakes (forget Switching Channels, if you can), but I wonder how it would play if the leads were two gay men?

As I wrote when marking the 100th anniversary of Reed's birth (forgive my self-plagiarism, but it makes this enterprise go faster), "Rewatching The Third Man recently, it once again captivated me from the moment the great zither music by Anton Karas begins to play over the credits.…If you haven't seen The Third Man (and shame on you if you call yourself a film buff and you haven't), watching the Criterion DVD really is the way to go, not only for a crisp print but to be able to compare the different versions offered for British and U.S. audiences (though only the different openings are included — we don't see what 17 minutes David Selznick cut for American audiences). With its great scenes of Vienna, sly performances and perhaps the greatest entrance of any character in movie history, The Third Man stays near the top of all films ever made, even nearly 60 years after its release."

I don’t know what I was thinking ranking Seven Samurai so low on my 2007 list. Having seen it a couple more times since, I’ve rectified that error. All films this long should hold their length as well as this rollicking adventure does. Each time I see it, it transfixes me from beginning to end. Hacks like Michael Bay should look to a film such as Seven Samurai and discover how characters trump stunts, explosions and special effects in great action-adventure films. It's amazing that with such a large cast, not just of the title samurai but of the farmers they defend as well, the actors and Kurosawa develop so many distinct and worthy portraits. Granted, the running time helps, but they establish characters rather quickly from Takashi Shimura (unrecognizable from his role as the dying bureaucrat in Ikiru) as the lead samurai organizing the mission to the brilliant Toshiro Mifune as Kikuchiyo, a reckless samurai haunted by his past as a farmer's son. Full of action, humor, sadness, a bit of romance and plenty of heart, its influence on so many films that have come since can’t be calculated.

Currently, we live in a time of a vicious circle: Movies inspire theatrical musicals which in turn become movie musicals (or in most cases, don't. Don't be looking for Leap of Faith: The Musical on the big screen anytime soon). Still, there was a time when musicals were created as motion pictures. Singin' in the Rain remains the very best example of one of those. The songs soar, the dance numbers inspire and the performances evoke joy. On top of that, it's even a Hollywood story, set in the awkward time between silent film and sound and milking plenty of laughs from the situation, especially through the spectacular performance of Jean Hagen as a silent superstar with a voice hardly made for sound and a personality barely suitable for Earth. Gene Kelly gives his best performance, a young Debbie Reynolds shines and Donald O'Connor makes us all laugh. Decades later, Singin' in the Rain got transformed (if that's the right word) a Broadway stage version. It wasn't very good. Stick with the movie.

When I wrote about this film for the Screenwriting Blog-a-Thon hosted by Mystery Man on Film in 2007, I said, "As far as I'm concerned, this film is Allen's masterpiece. Others will cite Annie Hall or Manhattan or some other titles and while I love Annie Hall and many others well, over time The Purple Rose of Cairo is the Allen screenplay that has reserved the fondest place in my heart. The screenplay isn't saddled with any extraneous scenes and no sequence falls flat as it builds toward its bittersweet ending. For me, it's Woody Allen's greatest screenplay and one of the best ever written as well." I've been pleasantly surprised at the number of people who have said to me since I wrote that how they agree, even among moviegoers who declare themselves not to like Woody Allen as a rule. It's the perfect blend of comedy, fantasy and realism and one of the greatest depictions of the magic of movies ever put on film. In The Purple Rose of Cairo, when Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels) and his pith helmet step off the screen, the repercussions end up being both hilarious, touching and painfully real.

While for me Jules and Jim stands as the high watermark of the French New Wave films, when you look objectively at the story of Jules and Jim, it may employ many of that movement's techniques but many aspects of Truffaut's film set it apart from its cinematic brethren such as its period setting and a time span that covers more than two decades separates it from the movement as well. However, that doesn’t affect the film’s magnificence. In a funny way, the 1962 film forecast the free love movement to come later that decade except its source material happened to be a semiautobiographical novel set in the early part of the 20th century. The prurience though lies in the mind of the fuddy duddy because part of what makes Jules and Jim so special comes from Truffaut's refusal to pass any judgment, be it positive or negative, upon the behavior of his characters. Despite the director's own criticism many years down the road that the film isn't cruel enough when it comes to love, the three main characters do suffer by the end but he doesn't paint it as punishment for their sins. In a 1977 interview, Truffaut said he thought he was "too young" when he made Jules and Jim. If he'd made it at any other age, it wouldn't be the same movie and probably wouldn't hold the same appeal for so many. For Jules and Jim to grab you, really grab you, I think you need to be young when you see it the first time, and that's why Truffaut, not yet 30 but captivated by the novel since 25, had to be young as well.

Wilder’s screenplay with Charles Brackett and D.M. Marshman Jr. proves surprisingly malleable, never fitting easily into one genre and playing differently in each viewing. It can be the darkest of Hollywood satires or the tragedy of a woman driven insane by a world that’s passed her by. Gloria Swanson’s brilliant performance as Norma Desmond can come off as a vulnerable madwoman or a master manipulator. Similarly, William Holden’s down-on-his-luck screenwriter Joe Gillis looks like a shallow opportunist in some scenes, an in-over-his-head dupe in others. The layers make Sunset Blvd. fresh and endlessly watchable. Wilder and his co-writers always produced great dialogue, but I believe Sunset Blvd. stands as Wilder’s greatest work as a director as well.

Hitchcock blessed us with so many classics, it’s hard to pick the best. This list contains seven Hitchcocks, but Rear Window stands tallest to me. I’ll allow two great directors to state my case. First, François Truffaut from The Films in My Life: “Rear Window is…a film about the impossibility of happiness, about dirty linen that gets washed in the courtyard; a film about moral solitude, an extraordinary symphony of daily life and ruined dreams." From David Lynch, as he wrote in Catching the Big Fish: “It's magical and everybody who sees it feels that. It's so nice to go back and visit that place." David, I couldn’t agree more.

Goodfellas rarely gets selected as the premier example of Scorsese’s brilliance as a filmmaker — and that’s a damn shame because, within its two hour and 20 minute running time, Goodfellas not only encapsulates Scorsese and filmmaking at their best but might be the director’s most personal film. If you wanted to demonstrate practically any aspect of moviemaking to a novice — editing, tracking shots, reverse pans, effective use of popular music — Scorsese disguised a film school in the form of this feature film about low-level gangsters. Goodfellas also happens to be the director’s most re-watchable film and, in a career stocked with masterpieces, it remains my favorite.

Every time I return to Paddy Chayefsky’s prescient screenplay, something new leaps out that I didn’t catch before. Most recently, it’s from one of Howard Beale’s monologues once he’s become the UBS network’s star. As part of the speech, delivered by the late, great Peter Finch, Beale tells his viewers, “Because you people, and 62 million other Americans, are listening to me right now. Because less than three percent of you people read books! Because less than 15 percent of you read newspapers!” Chayefsky died long before the Web revolution so remember that the next time someone blames the newspaper industry's death on the Internet. Better yet, watch Network and revel in the delicious words, magnificent ensemble and Lumet’s fine direction.

Many prefer the Kubrick of 2001: a Space Odyssey or later works such as A Clockwork Orange or Barry Lyndon, but I’ve always found him best when satirical, especially when that sharp humor took aim at the futility of war as in the underrated Full Metal Jacket, the great Paths of Glory and the best of the bunch, the incomparable Dr. Strangelove. To take the prospect of nuclear apocalypse instigated by a general driven mad by his impotence and produce one of the wall-to-wall funniest films ever was no small achievement, but having Peter Sellers in his multiple roles, Sterling Hayden and, most of all, George C. Scott’s hyperbolic, acrobatic and energetic work as Gen. Buck Turgidson, sure helped. That's not to mention Slim Pickens and Keenan Wynn as well and the surreal beauty of that closing of multiple mushroom clouds backed by that wonderfully ironic song.

So rarely does the best picture Oscar go to the best film, it always amazes me that the Academy recognized Casablanca (though for 1943, since it didn’t open in L.A. until a few months after its New York premiere). Claude Rains’ irreplaceable Captain Renault may say, “The Germans have outlawed miracles,” but the most miraculous thing of all was that a screenplay without an ending and based on an unproduced play managed to coalesce into the finest movie the Hollywood studio system ever produced. With a superb ensemble of character actors and stars delivering dialogue with more memorable lines than nearly any other film ever, courtesy of screenwriters Julius J. & Philip G. Epstein and Howard Koch, play it forever, Sam.

It does worry me that we seem to lack a filmmaker as ballsy as Robert Altman was (first person to suggest Paul Thomas Anderson gets punched in the face). Thankfully, he left us his body of work (some dogs to be certain, but the ecstasies we receive from his great ones allow us to forgive). For me, Nashville never wavers from its spot at the top of the Altman charts. It’s a musical, but not really. It’s about politics, but not really. We get to watch 24 characters intersect (or not) as Altman and screenwriter Joan Tewksbury design a tapestry displaying a picture of America on the eve of its bicentennial. It also presents ideas that in their own way prove as prescient as those in Network.

Many of the greatest films turn out to be examples of triumph over adversity and that certainly proved to be the case with Children of Paradise, Carné’s two-part masterpiece made during the Nazi occupation of France. When I wrote at length about this deceptively simple tale of mimes and actors, criminals and the aristocracy, I said that if I revised my 2007 list, the film likely would rise higher than its 18th rank. As you see, it most definitely has. Better to experience its beauty and magic than attempt to briefly describe it.

One wonders what the total would be if we calculated the number of words written extolling the brilliance and significance of Orson Welles’ filmmaking debut. Granted, the curmudgeons and contrarians exist and while not a day goes by that I don’t remind someone that all opinions are subjective by definition, Citizen Kane looms as the behemoth that practically defies that statement. Its status as a cinematic masterpiece comes close to being an objective truth. I have nothing new to add about this wonder. The film speaks for itself.

After what I wrote about Citizen Kane, you’d think it would rest in my top spot, but Renoir’s exquisite tragicomedy grabbed a foothold in my Top 10 as soon as I saw it in college and it took only one or two more viewings for Rules to clinch the No. 1 perch where it’s remained for more than two decades. Something personal within the film (too much identification with Renoir’s character of Octave; the character of Christine, who seems to cast a spell over all men who cross her path) hooks me in above and beyond the film’s artistry. If that explanation seems skimpy, I defer to what Octave says, "The awful thing about life is this: Everybody has their reasons."

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Carné, Carol Reed, Chaplin, Curtiz, Gene Kelly, Hawks, Hitchcock, Keaton, Kubrick, Kurosawa, Lists, Lumet, Renoir, Scorsese, Truffaut, Welles, Wilder, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

House No. 177: Everybody Dies

By Edward Copeland

When I first heard that House would end this season, I immediately told a friend that the only way the show could end would be with the prickly but brilliant doctor with a limp dying. I said, "He's been shot, practically killed himself several times attempting to solve a medical puzzle, committed himself to a mental hospital and been sent to jail — what else could they do but actually kill him?" Turns out I was right — sort of. I can't say that the finale overwhelmed me or that it falls onto the list with the worst series finales of all time. Except for its closing moments between Hugh Laurie and Robert Sean Leonard's Wilson, "Everyone Dies" played to me the same way most of the episodes in the past three seasons did — as if the show's creative team was stuck in idle and just spinning their wheels. My criticisms of Monday night's ending does contain several specifics, which I'll get to after the jump. In a post to come later, I'll talk about the series in general and an attempt to pick 10 favorite episodes of all time. Though I continue tinkering with that list, I can tell you I have decided that of the eight seasons, looking back at when all the best episodes were, the choice for best season hardly was a contest. That prize belongs to the second season.

The rumors circulated for a while that some former cast members such as Jennifer Morrison (Cameron) and Kal Penn (Kutner) would be making appearances and I saw a YouTube video with footage of the wrap party where Amber Tamblyn (that med student whose name I can't remember) mentioned that she'd pop up briefly in the last episode.

It seemed obvious to me that if they planned to resurrect Kutner that Amber (Anne Dudek) would not be far behind and she wasn't. (Hooray!) I don't know if the writers considered it, but if they planned for faces of his past to confront House as the building burned, why not try to get R. Lee Ermey back as the man who raised him and left him with so many psychological scars? More importantly, though I've read the stories that Lisa Edelstein's departure from House wasn't exactly a happy one, but the lack of Lisa Cuddy, either in House's imagination or at his "funeral" just rang false. I could imagine given the way the character left that Cuddy would not bother with the funeral, but you can't convince me that Amber, Kutner, Cameron and ex-girlfriend Stacy (Sela Ward) visit his smoke-inhalation induced reverie but Cuddy got turned away at the rope line by a bouncer. By the way, what in the hell has Sela Ward done to her face? Why do performers insist on damaging their most important

It seemed obvious to me that if they planned to resurrect Kutner that Amber (Anne Dudek) would not be far behind and she wasn't. (Hooray!) I don't know if the writers considered it, but if they planned for faces of his past to confront House as the building burned, why not try to get R. Lee Ermey back as the man who raised him and left him with so many psychological scars? More importantly, though I've read the stories that Lisa Edelstein's departure from House wasn't exactly a happy one, but the lack of Lisa Cuddy, either in House's imagination or at his "funeral" just rang false. I could imagine given the way the character left that Cuddy would not bother with the funeral, but you can't convince me that Amber, Kutner, Cameron and ex-girlfriend Stacy (Sela Ward) visit his smoke-inhalation induced reverie but Cuddy got turned away at the rope line by a bouncer. By the way, what in the hell has Sela Ward done to her face? Why do performers insist on damaging their most important asset this way? Have plastic surgery techniques grown worse over the years instead of better? Just for a light moment, they ought to have tossed in a moment of Taub (Peter Jacobson) looking horrified when he meets Stacy for the first time given that's what he used to do for a living. It's terrible — Ward's facial muscles looked as if they were frozen. I could cite lots of other examples — scary Kenny Rogers, Dolly Parton's new look that makes her cheeks and lips look as if they modeled them on a fish and all the lost, possibly great performances we could have from Faye Dunaway, who know resembles Jack Nicholson as The Joker in Tim Burton's Batman when he wears the flesh makeup. Pardon the digression. Cuddy's absence made for the biggest flaw. It was great to see many of the other past regulars or prominent guest stars, especially Andre Braugher's brief moments as Dr. Nolan. The resemblance to the Scrubs finale might have been too similar (the real finale, not that lame-ass med school half-season), but how about some of the patients he saved at the funeral or the ones he didn't haunting him? I wouldn't have hated seeing Michael Weston return as Lucas. Even when House's former personal P.I. dated Cuddy, he and Greg continued to get along in a civil manner and before that, his character really was the only other male character besides Wilson to forge some kind of bond with House. He never acted like the sort to let resentment simmer for long stretches of time, so I imagine Lucas got over Cuddy dumping him for House long ago and it's highly doubtful they reconciled since we last saw her. Again though, that goes back to a loose thread that deserved to be tied in some way, even if didn't take the form of an appearance by Edelstein.

asset this way? Have plastic surgery techniques grown worse over the years instead of better? Just for a light moment, they ought to have tossed in a moment of Taub (Peter Jacobson) looking horrified when he meets Stacy for the first time given that's what he used to do for a living. It's terrible — Ward's facial muscles looked as if they were frozen. I could cite lots of other examples — scary Kenny Rogers, Dolly Parton's new look that makes her cheeks and lips look as if they modeled them on a fish and all the lost, possibly great performances we could have from Faye Dunaway, who know resembles Jack Nicholson as The Joker in Tim Burton's Batman when he wears the flesh makeup. Pardon the digression. Cuddy's absence made for the biggest flaw. It was great to see many of the other past regulars or prominent guest stars, especially Andre Braugher's brief moments as Dr. Nolan. The resemblance to the Scrubs finale might have been too similar (the real finale, not that lame-ass med school half-season), but how about some of the patients he saved at the funeral or the ones he didn't haunting him? I wouldn't have hated seeing Michael Weston return as Lucas. Even when House's former personal P.I. dated Cuddy, he and Greg continued to get along in a civil manner and before that, his character really was the only other male character besides Wilson to forge some kind of bond with House. He never acted like the sort to let resentment simmer for long stretches of time, so I imagine Lucas got over Cuddy dumping him for House long ago and it's highly doubtful they reconciled since we last saw her. Again though, that goes back to a loose thread that deserved to be tied in some way, even if didn't take the form of an appearance by Edelstein.

"Everybody Dies" lacked — until its very final moments — the key asset that attracted me to House in the first place: Its humor. (Though I give them points for waiting eight years before making a Dead Poets Society reference.) At least the final medical case involving guest patient James LeGros (looking physically more like the LeGros I'm familiar with than his beer-bellied Wally Burgan in HBO's Mildred Pierce miniseries) actually tied into the plot. House might have insisted on only taking "interesting" patients, but that part of the show stopped being interesting to me and most viewers I know a long time ago. I also had a couple of nitpicky things. Chase (Jesse Spencer) quits two weeks ago and now that House is "dead," he comes back and gets his job? Honestly, maybe I'm alone on this, but hasn't Taub demonstrated better diagnostic skills? I also find it funny that such a huge deal keeps being made about House driving his car into a living room and then breaking parole by causing a ceiling to collapse. Foreman (Omar Epps) refuses to commit perjury for him to get House off the hook about accidental ceiling collapse, but he's complicit in covering up the murder of Dibala (James Earl Jones), the dictator of an unnamed African country and just appointed the doctor who killed Dibala on purpose to head House's department. They call House a dangerous jerk? Also, while it's nice to see that Cameron already found a new guy and gave birth, I can't be the only one who wants to know if she defrosted dead husband No. 1's sperm to spawn or if the tot belongs to the man.

On the other hand, while we assume that House and Wilson's honeymoon will be short, could the show end any other way? In many ways, House wasn't simply Sherlock Holmes recast as a doctor, it focused on living in and with pain. You could summarize the show's thesis with almost any of the classic jokes that Woody Allen's Alvy Singer delivers in Annie Hall. The final season of House even included an episode titled "We Need the Eggs." You could take any of them: "And such small portions." That's why the idea of House considering suicide just rang false. He might after Wilson lost his battle with cancer, but not before. His attitude echoes Alvy (coincidentally, the name of his hyper buddy from his time at the mental hospital, but spelled with an "ie" instead of a "y," played by Lin-Manuel Miranda). Life is "full of loneliness, and misery, and suffering, and unhappiness, and it's all over much too quickly." Actually, the closest Annie Hall line I believe has to be when Alvy says, "I feel that life is divided into the horrible and the miserable. That's the two categories. The horrible are like, I don't know, terminal cases, you know, and blind people, crippled. I don't know how they get through life. It's amazing to me. And the miserable is everyone else. So you should be thankful that you're miserable, because that's very lucky, to be miserable." Now though, for at least five months, James Wilson and the late Gregory House ride off in the sunset together. That one woman in their apartment building "mistakenly" thought they were gay. Not counting why Wilson and Amber split up, something must keep breaking up Wilson's relationships — and some preceded Wilson meeting House. If the motorcycles break down and they end up on a bus as Wilson nears the end, I will have a hard time picturing him as Ratso Rizzo to House's Joe Buck though.

Laurie alone kept me hanging on to the end of House because I loved the character he created. Sadly, I believe he soon will join an exclusive club. Members include Ian McShane's Al Swearengen on Deadwood, Jeffrey Tambor as Hank Kingsley on The Larry Sanders Show, Jason Alexander as George Costanza on Seinfeld, John Goodman as Dan Conner on Roseanne and Jackie Gleason as Ralph Kramden on The Honeymooners, to name a few of the actors who created some of the greatest characters in television history, none of whom ever received an Emmy Award. Hugh Laurie certainly belongs in this group because Dr. Gregory House was one of a kind. Still to come, saluting the series as a whole and unveiling that list.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Braugher, Deadwood, Dunaway, HBO, House, J.E. Jones, John Goodman, Larry Sanders, Nicholson, Seinfeld, Tambor, Tim Burton, TV Recap, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE