Wednesday, August 31, 2011

From the Vault: Beethoven

Good family films make you feel like a child again. In one respect, Beethoven succeeds on that level — it certainly made me want to lie down and take a nap.

Charles Grodin, the latest victim of a career setback caused by co-starring in a film with Jim Belushi, returns as the gruff, money-obsessed father of a family who adopts a lost dog. Grodin's character hates dogs — especially large St. Bernards like Beethoven that he fears will wreck his life.

Grodin should have been more concerned with a movie this lame wrecking his career.

Beethoven tells the story of the young St. Bernard's life from puppydom to maturity. It seems that Beethoven was stolen from a pet store where he was destined to be used for experiments by the requisite evil authority figure.

Happily, a canine pal escapes with Beethoven, sparing both from the dastardly plot. Alas, the moviegoer has no such luck.

Dean Jones (ironic, considering he once was The Shaggy D.A.) plays the veterinarian who earns money by testing new forms of ammunition on the heads of dogs. Now, that will certainly making kids seeing the film more comfortable the next time dad takes Fido to the vet, won't it? ("Don't worry son — it's not like the doctor is going to shoot Fido in the head.")

The film itself contains nothing else so original. It takes every cliche from every dog story ever told. From urination to drool in the shoes (a sly reference to Turner & Hooch), every plot development conveniently provided alongside typical superdog twists.

I checked the writing credits and lo and behold — guess who gets half credit for concocting this mess? None other than John "King of Formula" Hughes.

This St. Bernard truly earns his sainthood — he gets the oldest daughter a date, allows the son to get the better of bullies and saves the youngest girl from drowning. The kids are your standard sitcom variety — bland and talentless Stepford Child performers.

As in most family TV shows, Grodin's family contains the requisite three kids. A sappy musical score even accompanies the film, substituting for the fourth child TV families inevitably get in the third or fourth season.

Yes, all the TV elements show up — yuppie foils, sensible mother, frazzled father, bullied kid, little daughter who speaks rhythmically, oldest child with a streak of rebellion, evil authority figure, the dog's canine pal. Beethoven houses neither anything new nor good. The movie needed to be put to sleep so the audience could be put of its misery.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Grodin, John Hughes

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, August 07, 2011

A soul is never lost, no matter what overcoat you put on

By Edward Copeland

As people who read me regularly know, it takes a lot to get me to see a remake of a movie I deemed very good or better because I find that it is usually A). Pointless. and B). Almost certain to disappoint. The instances where a remake turned out better than a good or great original have been few. I hadn't established this rule when I saw 1978's Heaven Can Wait starring Warren Beatty, co-written by Beatty and Elaine May and co-directed by Beatty and Buck Henry. At the time, I didn't even know it was a remake of 1941's Here Comes Mr. Jordan, which marks its 70th anniversary today. Those two films mark a rare time when the original and its remake nearly equal each other in quality (The third time was not a charm when Chris Rock tried to re-do it as Down to Earth). Today, we celebrate Here Comes Mr. Jordan on its birthday and watching it again, the movie continues to hold up, though I admit that Beatty's version bests it in some areas.

Here Comes Mr. Jordan didn't begin as an original screenplay. Sidney Buchman & Seton I. Miller adapted Harry Segall's play Heaven Can Wait and rechristened it with the new title, though Beatty brought the orignal moniker back when he remade the story in 1978. Both versions were nominated for the Oscar for best picture, though both lost. (To add a little confusion to different titles for the two best picture nominees, in 1943, Ernst Lubitsch directed the film version of the play Birthday and called it Heaven Can Wait and it received a nomination for best picture. So there are two best picture nominees called Heaven Can Wait, but they have nothing to do with one another.)

Here Comes Mr. Jordan begins with some words on the screen telling us about "this fantastic yarn" they heard from Max Corkle that they just had to share with us. Then following the credits, more words set up the movie's opening locale, telling us, just a few words at a time, accompanied by images of nature:

where all is…

Peace…

and Harmony…

and Love…

After the literal punchline, we meet boxer Joe Pendleton (Robert Montgomery) as he finishes his sparring match and climbs out of the ring to speak with his manager Max Corkle (James Gleason). Max has news for his prized fighter — it appears that he has finally managed to get Joe a chance at the world title with a bout against the current champ, only they'll have to leave their ideal New Jersey training camp immediately and hop the train to New York. Pendleton can't wait to leave, but he'll meet them there — it will give him some time for his hobby — flying his plane. Corkle begs him not to fly, but Joe tells him not to worry, he will have his lucky saxophone with him, which he begins playing much to Corkle's annoyance. Joe takes to the air, lucky sax with him. He even tries playing it and flying at the same time — until part of the plane starts to rip apart. He puts his sax down and tries to regain control of the aircraft, but it's too late — the plane spirals to earth and crashes.

With the impact with which the plane hit, leaving nothing but crumpled wreckage, it's understandable that someone such as Messenger 7013 (the always delightful Edward Everett Horton) would presume Pendleton was toast. Unfortunately, 7013 is new to his job as an afterlife guide and this is his first assignment. He

breaks a cardinal rule: He removes Joe's soul before it's confirmed that he would have died in the crash. So, when Joe, still clutching his sax, and his guide arrive in the cloud-strewn weigh station where the newly dead board a plane to their final destination, Joe protests quite adamantly that he isn't dead. He's in great shape "in the pink," as he says. His assignment annoys 7013 quite a bit and he's making so much noise that he's attracted the attention of the man in charge of the weigh station, Mr. Jordan (Claude Rains). When Jordan finds that Pendleton isn't on the list of new arrivals, he has the plane's co-pilot (a young Lloyd Bridges) radio for information on when Joe Pendleton was due to arrive. The information comes back: Joe would have survived the crash. He wasn't scheduled to die until 1991. (Robert Montgomery almost made that in real life: He died in 1981.) Jordan chastises 7013 for being premature and decides to handle Joe's case himself: They'll have to return him to his body.

breaks a cardinal rule: He removes Joe's soul before it's confirmed that he would have died in the crash. So, when Joe, still clutching his sax, and his guide arrive in the cloud-strewn weigh station where the newly dead board a plane to their final destination, Joe protests quite adamantly that he isn't dead. He's in great shape "in the pink," as he says. His assignment annoys 7013 quite a bit and he's making so much noise that he's attracted the attention of the man in charge of the weigh station, Mr. Jordan (Claude Rains). When Jordan finds that Pendleton isn't on the list of new arrivals, he has the plane's co-pilot (a young Lloyd Bridges) radio for information on when Joe Pendleton was due to arrive. The information comes back: Joe would have survived the crash. He wasn't scheduled to die until 1991. (Robert Montgomery almost made that in real life: He died in 1981.) Jordan chastises 7013 for being premature and decides to handle Joe's case himself: They'll have to return him to his body.

Easier said than done. When Mr. Jordan and Joe arrive at the crash scene, his body already has been retrieved, so he's been discovered and likely declared dead. Joe suggests they find Corkle so they head to New York, passing a newspaper boy touting the news of his death in a plane crash. When they get to Max's apartment, a devastated Corkle greets mourners, including a group of neighborhood kids saying what a swell guy Joe was. They'd been planning to take flowers to where Max says they took Joe, but couldn't remember what he called it. "Crematorium," Max reminds them. Uh-oh. Not only has Pendleton's death been reported already, his body no longer exists for Mr. Jordan to re-insert his soul even if a resurrection could be rationally explained at this point. Joe demands satisfaction for this screwup — they owe him 50 more years of life — so Mr, Jordan proposes that they find another body for him. Inside, he'll still be Joe Pendleton, but on the outside he'll take on another person who was due to die's identity. Joe does have some demands: He was on the verge of getting a shot at the world boxing title so whatever body they find has to be in shape so he can accomplish the same task. After previewing countless bodies around the world, none of which meet Joe's standards, Jordan takes him to yet

another one, saying he thinks this one might be promising. Pendleton reminds him again that he needs to be in good physical condition because, "I was in the pink." Jordan, who seems an extremely patient sort, has grown tired of finicky Joe, particularly this phrase. "That is becoming a most obnoxious color. Don't use it again," Jordan tells him. They are outside the gates of a mansion. Jordan explains the wealthy banker inherited his fortune and his name is Bruce Farnsworth (though it was changed to Leo in Heaven Can Wait because in the '70s, no one liked the name Bruce for some reason. Just ask TV's The Incredible Hulk). Jordan sits down at the piano and calmly starts flipping through sheet music. Joe asks where this Farnsworth is and Jordan explains he's upstairs being drowned to death — murdered by his wife and personal secretary. Joe goes nuts. Shouldn't they be calling the police? Jordan has to remind him again that no one can see or hear them. Joe already has made up his mind not to take a body that's mixed up in murder and they should skedaddle, but Jordan has to wait and collect Farnsworth, regardless of whether Joe accepts his body or not. Jordan stops looking through the music and turns and faces Joe. "It's over," he says, indicating that Farnsworth is dead.

another one, saying he thinks this one might be promising. Pendleton reminds him again that he needs to be in good physical condition because, "I was in the pink." Jordan, who seems an extremely patient sort, has grown tired of finicky Joe, particularly this phrase. "That is becoming a most obnoxious color. Don't use it again," Jordan tells him. They are outside the gates of a mansion. Jordan explains the wealthy banker inherited his fortune and his name is Bruce Farnsworth (though it was changed to Leo in Heaven Can Wait because in the '70s, no one liked the name Bruce for some reason. Just ask TV's The Incredible Hulk). Jordan sits down at the piano and calmly starts flipping through sheet music. Joe asks where this Farnsworth is and Jordan explains he's upstairs being drowned to death — murdered by his wife and personal secretary. Joe goes nuts. Shouldn't they be calling the police? Jordan has to remind him again that no one can see or hear them. Joe already has made up his mind not to take a body that's mixed up in murder and they should skedaddle, but Jordan has to wait and collect Farnsworth, regardless of whether Joe accepts his body or not. Jordan stops looking through the music and turns and faces Joe. "It's over," he says, indicating that Farnsworth is dead.

Jordan, though he works on Heaven's side, does have a bit of devilish manipulation in him (as Rains always played so well, and would five years later as the devil himself in another film from a story by Harry Segall, Angel on My Shoulder). Until Farnsworth's body is discovered, Jordan still has time to talk Joe into taking his body. They eavesdrop as the co-conspirators come downstairs and the personal secretary Tony Abbott (John Emery) tries to calm the nerves of Farnsworth's wife Julia (Rita Johnson), reassuring her that they won't be caught and that Bruce certainly is dead. Watching Here Comes Mr. Jordan this time, it's

impossible not to say that Heaven Can Wait certainly did a better job in the casting of Abbott and Julia. It isn't that Emery and Johnson are bad, but their characters are far less important in the original film while in the remake when the parts were placed in the very capable hands of Charles Grodin and Dyan Cannon, not only were the roles beefed up, they also were hilarious villains. Emery and Johnson play straight-faced villains for the most part whereas Grodin and Cannon added to the comic ensemble. You're laughing as they botch attempt after attempt on Warren Beatty's Joe Pendleton. Back in the 1941 version, while Robert Montgomery's Joe finds it interesting that he can listen in on these newly minted murderers, he also finds it frustrating that he can't punish them somehow. He asks Mr. Jordan what happens if these two killed him again. Won't he be in the same predicament he's in now? Jordan describes the human body as nothing more than an overcoat. What makes a person who he or she really is resides inside. "A soul is never lost, no matter what overcoat you put on," Jordan tells Joe. Then, the game changer enters in the form of a beautiful woman (Evelyn Keyes) asking to see Mr. Farnsworth. Now, Joe is intrigued.

impossible not to say that Heaven Can Wait certainly did a better job in the casting of Abbott and Julia. It isn't that Emery and Johnson are bad, but their characters are far less important in the original film while in the remake when the parts were placed in the very capable hands of Charles Grodin and Dyan Cannon, not only were the roles beefed up, they also were hilarious villains. Emery and Johnson play straight-faced villains for the most part whereas Grodin and Cannon added to the comic ensemble. You're laughing as they botch attempt after attempt on Warren Beatty's Joe Pendleton. Back in the 1941 version, while Robert Montgomery's Joe finds it interesting that he can listen in on these newly minted murderers, he also finds it frustrating that he can't punish them somehow. He asks Mr. Jordan what happens if these two killed him again. Won't he be in the same predicament he's in now? Jordan describes the human body as nothing more than an overcoat. What makes a person who he or she really is resides inside. "A soul is never lost, no matter what overcoat you put on," Jordan tells Joe. Then, the game changer enters in the form of a beautiful woman (Evelyn Keyes) asking to see Mr. Farnsworth. Now, Joe is intrigued.Her name is Bette Logan (when Julie Christie played the role in Heaven Can Wait along with many of her details being changed to explain her British accent, they also changed the spelling of her first name to Betty for some reason) and she wants to see Farnsworth because her father has been accused by the currently dead

tycoon in a stock swindle that Farnsworth himself perpetrated and framed Bette's father for, putting the man behind bars. Bette knows her father is innocent and wants to plead to Farnsworth to look personally into the story and help prove that he didn't steal anything from him. At first, Abbott and Julia act quite sympathetic to Ms. Logan, mainly because Abbott has whispered to Julia before the butler Sisk (Halliwell Hobbes) showed her in that she'd help their story if they are meeting with her when Farnsworth's body is found. Joe and Jordan serve as invisible witnesses to Bette's story and it touches Pendleton, who tells Jordan he wishes he could help her. Jordan tells Joe he can — if he becomes Bruce Farnsworth. Joe stays on the fence, but that's when Abbott sends Sisk upstairs to fetch the dead man. Jordan reminds him that there isn't much time to decide now. As Sisk heads upstairs, Abbott and Julia turn on Bette, saying her father is guilty of all of

tycoon in a stock swindle that Farnsworth himself perpetrated and framed Bette's father for, putting the man behind bars. Bette knows her father is innocent and wants to plead to Farnsworth to look personally into the story and help prove that he didn't steal anything from him. At first, Abbott and Julia act quite sympathetic to Ms. Logan, mainly because Abbott has whispered to Julia before the butler Sisk (Halliwell Hobbes) showed her in that she'd help their story if they are meeting with her when Farnsworth's body is found. Joe and Jordan serve as invisible witnesses to Bette's story and it touches Pendleton, who tells Jordan he wishes he could help her. Jordan tells Joe he can — if he becomes Bruce Farnsworth. Joe stays on the fence, but that's when Abbott sends Sisk upstairs to fetch the dead man. Jordan reminds him that there isn't much time to decide now. As Sisk heads upstairs, Abbott and Julia turn on Bette, saying her father is guilty of all of which he is accused. Joe asks Jordan if he can just use Farnsworth's body long enough to help Bette and then find a body in better shape. Jordan agrees and before he knows it, the two are upstairs in Farnsworth's bathroom. Jordan wraps a robe around Joe as he climbs out of the tub, but Pendleton looks in the mirror and still sees himself and when he opens his mouth, he sounds the same. Sisk knocks on the door, asking if he's OK. Jordan assures Joe that he only looks and sounds the same to himself. The rest of the world will see and hear him as Bruce Farnsworth. Joe answers Sisk that he'll be out in a minute and Sisk doesn't appear suspicious. Pendleton remains worried as he leaves the bathroom wearing the robe, obviously too big for his body. He almost marches straight downstairs until Sisk reminds him what he is wearing and that perhaps he should get dressed first. Then Sisk notices something he's never seen before and asks his employer if it's his. Of course, Pendleton says, taking his lucky sax.

which he is accused. Joe asks Jordan if he can just use Farnsworth's body long enough to help Bette and then find a body in better shape. Jordan agrees and before he knows it, the two are upstairs in Farnsworth's bathroom. Jordan wraps a robe around Joe as he climbs out of the tub, but Pendleton looks in the mirror and still sees himself and when he opens his mouth, he sounds the same. Sisk knocks on the door, asking if he's OK. Jordan assures Joe that he only looks and sounds the same to himself. The rest of the world will see and hear him as Bruce Farnsworth. Joe answers Sisk that he'll be out in a minute and Sisk doesn't appear suspicious. Pendleton remains worried as he leaves the bathroom wearing the robe, obviously too big for his body. He almost marches straight downstairs until Sisk reminds him what he is wearing and that perhaps he should get dressed first. Then Sisk notices something he's never seen before and asks his employer if it's his. Of course, Pendleton says, taking his lucky sax.Once Sisk has helped dress Joe/Farnsworth in what appears to be a more dapper-looking robe, he heads downstairs, much to the shock of Abbott and Julia. If the conspirators weren't confused enough that he isn't dead, they become downright dumbfounded when he starts speaking to Bette in a friendly tone and indicating that he's sure they can solve her problem. Abbott, who's aware that Farnsworth committed the crime himself, steps in and tries to scuttle the inroads Joe tries to make until a frustrated Bette leaves. Joe orders Abbott and Julia out of the study so he can practice his saxophone. When they exit, he consults Mr. Jordan, dejected because Bette hates him but Jordan tells him to give it time. Then Joe sets out to get to work on his other project — getting Farnsworth's flabby body into fighting shape and he's going to need Max Corkle for that.

Gleason most decidedly deserved his Oscar nomination as Corkle. He was another in the seemingly endless line of dependable character players of the 1930s and '40s, usually in comedies, but he never seemed to let the moviegoer down even if he was in a film that did. He's joined in Here Comes Mr. Jordan with another

example in Edward Everett Horton, but his role is a rather small one and doesn't equal the best of his work from the 1930s. Then of course, they've got the versatile Claude Rains along too, who could seemingly do it all — lead or supporting — in every possible genre: comedy, drama, action, adventure, horror, you name it. However, Here Comes Mr. Jordan is Gleason's time to shine, earning him his sole nomination the same year he was one of the best parts of Capra's Meet John Doe. His career lasted well into the late '50s, including Charles Laughton's sole directing effort The Night of the Hunter with arguably Robert Mitchum's most indelible role and his penultimate film was John Ford's great political drama The Last Hurrah starring Spencer Tracy. Gleason also has some credits as a director and a writer (which unfortunately includes being responsible for the dialogue in my choice for the worst best picture winner of all time, The Broadway Melody). The scene where Corkle shows up at the

example in Edward Everett Horton, but his role is a rather small one and doesn't equal the best of his work from the 1930s. Then of course, they've got the versatile Claude Rains along too, who could seemingly do it all — lead or supporting — in every possible genre: comedy, drama, action, adventure, horror, you name it. However, Here Comes Mr. Jordan is Gleason's time to shine, earning him his sole nomination the same year he was one of the best parts of Capra's Meet John Doe. His career lasted well into the late '50s, including Charles Laughton's sole directing effort The Night of the Hunter with arguably Robert Mitchum's most indelible role and his penultimate film was John Ford's great political drama The Last Hurrah starring Spencer Tracy. Gleason also has some credits as a director and a writer (which unfortunately includes being responsible for the dialogue in my choice for the worst best picture winner of all time, The Broadway Melody). The scene where Corkle shows up at the Farnsworth estate — and nearly gets kicked out by Abbott who doesn't know why he's there, not that Max does either — is a comic highlight as Joe inside Farnsworth's body works overtime to convince his manager that he really is Joe Pendleton and not some insane rich guy. Corkle is just convinced Farnsworth is a nutjob, especially when he begins talking to the invisible (to Max anyway) Mr. Jordan asking how to convince him. Finally, Joe thinks of the obvious and pulls out the sax. Max starts to believe. Joe explains he wants to get ready to get back in the ring, but he needs him to train him. He even promises to give Corkle 40 percent of whatever he wins. This is another area where Heaven Can Wait makes a bit more sense. Farnsworth would still have to fight his way up to get near the championship. It's a little less ludicrous when Warren Beatty's Farnsworth simply buys the football team and makes himself a player on it, but then Montgomery's Farnsworth won't have to worry about any bouts. As Corkle continues to try to believe what he's heard, Sisk interrupts to announce that Ms. Logan has returned, so Joe excuses himself for a moment and it's funny as Gleason's Corkle talks to the now-departed Jordan and feels around to see if he's there.

Farnsworth estate — and nearly gets kicked out by Abbott who doesn't know why he's there, not that Max does either — is a comic highlight as Joe inside Farnsworth's body works overtime to convince his manager that he really is Joe Pendleton and not some insane rich guy. Corkle is just convinced Farnsworth is a nutjob, especially when he begins talking to the invisible (to Max anyway) Mr. Jordan asking how to convince him. Finally, Joe thinks of the obvious and pulls out the sax. Max starts to believe. Joe explains he wants to get ready to get back in the ring, but he needs him to train him. He even promises to give Corkle 40 percent of whatever he wins. This is another area where Heaven Can Wait makes a bit more sense. Farnsworth would still have to fight his way up to get near the championship. It's a little less ludicrous when Warren Beatty's Farnsworth simply buys the football team and makes himself a player on it, but then Montgomery's Farnsworth won't have to worry about any bouts. As Corkle continues to try to believe what he's heard, Sisk interrupts to announce that Ms. Logan has returned, so Joe excuses himself for a moment and it's funny as Gleason's Corkle talks to the now-departed Jordan and feels around to see if he's there.

Needless to say, not only does Joe as Farnsworth get Bette's father off the hook, the pair fall in love as well. Bette worries, since Farnsworth has a wife, but Joe tries to explain the state of their relationship. He can't go into his real identity since she wouldn't know who Joe Pendleton is and saying that Julia and Abbott tried to kill him has risks as well, so he just leaves it as they are separated and she's cheating on him. He's very unhappy one day when Messenger 7013 shows up, telling Joe that it's time to exit Farnsworth. He orders him out, telling him he's "always gumming up the works." Now that he loves Bette, he's fine with Farnsworth. Mr. Jordan returns and reminds Joe that he asked to use Farnsworth on a

temporary basis. Joe ignores him and proceeds to make a phone call until a shot is heard and he falls to the floor, but he's fighting. Jordan has to coax him into leaving Farnsworth's body before it's too late. Abbott and Julia are thrilled that it worked this time and hide his body. Bette is beside herself, Corkle can't believe it's happened again, commenting that "Forty percent of a ghost is forty percent of nothing" and a new character, Inspector Williams of the police department (Donald MacBride) starts investigating Farnsworth's disappearance since Corkle tells him that Abbott and Julia killed him once before, but since he phrased it that way, Williams suspects Corkle may just be a kook. Max remains persistent while Abbott and Julia try to point suspicions at Bette, even though her father was cleared. The inspector just gets frustrated with the nonsense.

temporary basis. Joe ignores him and proceeds to make a phone call until a shot is heard and he falls to the floor, but he's fighting. Jordan has to coax him into leaving Farnsworth's body before it's too late. Abbott and Julia are thrilled that it worked this time and hide his body. Bette is beside herself, Corkle can't believe it's happened again, commenting that "Forty percent of a ghost is forty percent of nothing" and a new character, Inspector Williams of the police department (Donald MacBride) starts investigating Farnsworth's disappearance since Corkle tells him that Abbott and Julia killed him once before, but since he phrased it that way, Williams suspects Corkle may just be a kook. Max remains persistent while Abbott and Julia try to point suspicions at Bette, even though her father was cleared. The inspector just gets frustrated with the nonsense.Even if you haven't seen Here Comes Mr. Jordan or any of its remakes, good or bad, you probably have a good idea how things resolve themselves and while both it and Heaven Can Wait pack plenty of laughs for most of their running times and the romances in both films are rather run-of-the-mill, they still manage to be quite touching in their final moments, not just in the resolution of Joe and Bette/Betty but even more so with the realization that when Joe gets placed in his permanent body, his Pendleton memories are lost and both James Gleason and Jack Warden perfectly captured that bittersweet moment for Max Corkle in their respective films.

Admittedly, for a film I enjoy as much as I enjoy Here Comes Mr. Jordan, I never remember who directed it. Even when I see the name Alexander Hall, it rings no bells. Only one other title on his filmography sticks out and that's Rosalind Russell in My Sister Eileen. I have seen the last film he directed and it's somewhat ironic that it's that one. It's the 1956 Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz vehicle Forever, Darling where Ball's character gets advice from a guardian angel who takes the form of her favorite actor, James Mason. I only saw the film because I was working on my centennial tribute to Mason back in 2009. Otherwise, I can't imagine any other circumstances that would have made me watch it, but it is funny that the final film Hall helmed featured Mason as a guardian angel and then 22 years later Mason would play Mr. Jordan, another character from above, in Heaven Can Wait. Mason is very good in the role, but for me, there is only one Mr. Jordan.

Tweet

Labels: 40s, Buck Henry, Capra, Grodin, Jack Warden, John Ford, Julie Christie, L. Ball, Laughton, Lubitsch, Mason, Mitchum, Movie Tributes, Oscars, Rains, Remakes, Roz Russell, Tracy, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

The twilight of an extraordinary life

By Edward Copeland

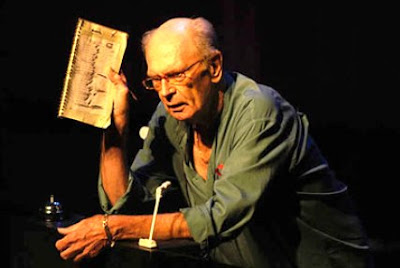

When Charles Nelson Reilly died in 2007, the percentage of people who knew who he was by name, unfortunately, already had fallen precipitously. Thankfully, in the final years of his life the theater actor turned game show fixture had developed and toured in a solo show about his life called Save It for the Stage. Even though Reilly had stopped touring with the show, The Life of Reilly's co-directors Frank L. Anderson and Barry Polterman talked him into performing it one more time in October 2004 so they could film it. As a result, they made this film record of Reilly's remarkable story as only he could tell it.

As title cards explain at the film's opening, the solo show evolved from a talk Reilly was asked to give in 1999. He didn't have anything planned and spoke extemporaneously for more than three hours, enjoying the hell out of it. After that experience, he worked with actor Paul Linke to pare down the show into a more compact running time and Save It for the Stage was born.

While the version of the solo show captured in The Life of Reilly runs half the time that original three-hour speech did, I imagine Reilly would hold your interest at the longer running time based on the nonstop cyclone

of energy he becomes as he shares an oral autobiography, beginning with his birth on Jan. 13, 1931, in The Bronx, and the difficulties growing up with his eccentric family, particularly his bigoted mother who was prone to say things such as "I should have thrown away the baby and kept the afterbirth." (She gave the stage show its name because any time young Charles would go on about something, she'd tell him to "Save it for the stage.") He was more enamored with his father who was a commercial artist, drawing beautiful color advertisements. Young Charles struggled in school, not realizing that his problem was his eyesight, not his intelligence, but he always was imaginative from an early age. A particularly poignant portion of the film comes when he describes his mom taking him to his first movie at the Loews Paradise and how he felt "so safe and warm" sitting there in the dark, gazing at those images.

of energy he becomes as he shares an oral autobiography, beginning with his birth on Jan. 13, 1931, in The Bronx, and the difficulties growing up with his eccentric family, particularly his bigoted mother who was prone to say things such as "I should have thrown away the baby and kept the afterbirth." (She gave the stage show its name because any time young Charles would go on about something, she'd tell him to "Save it for the stage.") He was more enamored with his father who was a commercial artist, drawing beautiful color advertisements. Young Charles struggled in school, not realizing that his problem was his eyesight, not his intelligence, but he always was imaginative from an early age. A particularly poignant portion of the film comes when he describes his mom taking him to his first movie at the Loews Paradise and how he felt "so safe and warm" sitting there in the dark, gazing at those images.Reilly's first taste of acting came in fourth grade when his teacher offered young Charles the role of Columbus in a class play. His mother was resistant, saying he'd never learn the lines because of his difficulties (still denying that eyesight was the problem) but the teacher talked her into it and his acting career was born in P.S. 53. Around the same time young Mr. Reilly received an opportunity, the elder Mr. Reilly missed a big one.

An artist who worked in black and white fell in love with his father's color artwork and urged him to go to California with him, but Reilly's mother nixed the move because all her relatives were on the East Coast. The man's name was Walt Disney. Soon, advertising turned more to photographs than illustrations and Reilly's father was thrown out of work and into alcoholism and eventually institutionalized, forcing young Charles and his mother to move to Hanover, Conn., to live with his uncle, aunt and grandparents, Swedish immigrants who spoke no English. Eventually, his father rejoined them and his aunt, who had her own problems, agreed to try a new medical procedure: a lobotomy. Though Reilly never dwells on his homosexuality, he tells how the neighbors to that household said that he was a "little odd."

"How do you think I felt being the odd one in that family?" he asks, adding that Eugene O'Neill wouldn't come near that house and that he spent his adolescence in an Ingmar Bergman film. However, he reminds his audience what Mark Twain said about laughter being the same in every language. Reilly's ability to tell these stories, some of them horrifying, and still be able to wring laughs from theatergoers was a great gift indeed and as he set out to act for a living in 1950, his tales of theater and show business prove even more entertaining.

A particularly astounding portion is when he discusses the acting class he attended taught by Uta Hagen at HB Studio, the school she founded with her husband Herbert Berghof. The cost was $3 a week. He reads the roll of his 11 a.m. Tuesday class and it's amazing because every name would achieve success, fame and accolades. Here is the list, minus Reilly, alphabetically:

As Reilly tells it, they all had three things in common: "We wanted to be on stage, none of us had any money and we COULDN'T ACT FOR SHIT!" Reilly adds that if they saw McQueen and Holbrook act out a scene as Biff and Happy Loman from Death of a Salesman one more time, "You'd go out of your fucking mind." He does make the point that people who wanted to act back then actually studied, something not as common as it used to be. By my count, this class (to date) has earned nine Tony Awards out of 30 nominations (11 out of 32 if you toss in Uta Hagen's two wins), six Oscars out of 16 nominations and 11 Emmys out of a whopping 61 nominations. Charles Nelson Reilly himself accounts for a Tony for featured actor in a musical as Bud Frump in the original production of Frank Loesser's How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, a nomination as Cornelius in the original Hello, Dolly! and a nomination for directing the revival of The Gin Game that starred Julie Harris and Charles Durning. Reilly earned three Emmy nominations: for The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, a guest shot on The Drew Carey Show and for reprising the Jose Chung character he created on The X-Files on an episode of Millennium.

As with all struggling actors in New York since the beginning of time, Reilly needed work to pay the bills until he started landing paying parts in production. He was excited when a female friend who worked at NBC got him a meeting with the possibility of on-air work. Reilly arrived and met Vincent J. Donahue, the NBC chief at the time, who dismissively sent him away telling him, "We don't put queers on television." Reilly admits that as hateful as that comment was, it rolled off his back. Words like that didn't bother him as much as coming home to find roaches in his Minute Rice. Though he eventually became somewhat of a gay icon, none of the autobiographical show deals with the difficulties of being a gay actor except for that anecdote and there is no mention of a romantic life. Reilly considered himself an actor first — his sexual orientation was just another aspect his life, just like his bad eyesight. Both were parts of him, but neither defined him.

Reilly lived and breathed theater and that is what he wanted to share with the audiences who came to his shows — the upbringing that got him to that point and how it always was an integral part of his life, even after he became better known for kids' TV shows and Match Game. In 1954, he appeared in 22 off-Broadway shows. His Broadway debut came, ironically, as an understudy for another actor who became a gay icon and game show staple — Paul Lynde. Lynde had to be out of Bye Bye Birdie every Thursday night because of a contract to appear on The Perry Como Show, so Reilly took his place once a week. Eventually, he also got to be Dick Van Dyke's understudy in the musical.

He discusses how his close friendship with Burt Reynolds began in New York when Reynolds was a struggling actor and then decades later, when Reynolds built his theater in Jupiter, Fla., he attached an acting school and gave Reilly a beach house to live in so he would teach.

He talks about his times in Hollywood, especially how much he enjoyed being on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson where he was a guest more than 100 times. He talks about one particular time when another guest was a woman who ran a Shakespeare in the Park program in Ohio and he said something and she responded, quite snootily, "What would someone like you know about Shakespeare?" Then he showed her.

Before he taught in Florida, he would teach acting back at that old HB Studio and in a story that particularly cracked me up because it reminded me of my days of both attending and judging high school drama contests almost 25 years ago now, he says, "If I saw one more Agnes of God…" If you've experienced high school drama contests since that play was written, you know exactly what he means (and I'd toss in 'night, Mother as well).

Reilly talks and talks and talks and you're never bored. You're usually laughing, but sometimes, as when he describes being present at 13 at an infamous Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus fire that claimed many lives, including that of one of his childhood friends, you're mesmerized. The Life of Reilly truly captivates. The biggest barrier to enjoying it is finding a way to see it. It's on streaming at Netflix but not DVD, so watch it there before you cancel and go back to DVD only. Neither GreenCine nor Blockbuster carries it on DVD or On Demand. Redbox doesn't carry it. Hulu Plus doesn't stream it. Amazon Instant Video DOES have it for $2.99, though you could buy it for $9.99. Best Buy CinemaNow doesn't have it for streaming. Comcast XfinityTV ON Demand doesn't have it either.

It's a miracle that Netflix's streaming has it right now because eventually, it won't as smaller, wonderful titles such as The Life of Reilly that are a whole FOUR years old and are perceived as having too small a niche audience disappear entirely from home rental availability. It's a shame because it means the number of people who remember Charles Nelson Reilly will decline more rapidly than it is declining already.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Awards, Burt Reynolds, Carson, Disney, Documentary, Durning, Frank Loesser, Geraldine Page, Grodin, Holbrook, Ingmar Bergman, Lemmon, Musicals, O'Neill, Oscars, Robards, Shakespeare, Television, Twain

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, November 05, 2010

Jill Clayburgh (1944-2010)

In the mid-1970s, Jill Clayburgh turned in great screen performance after great screen performance earning consecutive Oscar nominations for An Unmarried Woman and Starting Over in 1978 and 1979, then she seemed to vanish from the scene. In recent years, she had begun to reappear again in smaller roles, and I always hoped for a comeback as she always has been one of my favorites. Unfortunately, the cause for her disappearance appears to have been her health, particularly a form of chronic leukemia which has taken the actress's life at the age of 66.

She made her Broadway and film debuts practically in the same time period. In 1968, she hit the stage in the play The Sudden & Accidental Re-Education of Horse Johnson, which ran a mere five performances. That same year she had a brief part on a TV series called N.Y.P.D. before making her film debut in 1969's The Wedding Party directed by Brian De Palma and featuring Robert De Niro. That same year, she began a two-year run on the soap opera Search for Tomorrow.

She departed the soap for a starring role in the Broadway musical The Rothschilds which starred Hal Linden and with music by the Fiddler on the Roof team of lyricist Sheldon Harnick and composer Jerry Bock, who died just earlier this week. She also was an original cast member of the musical Pippin and Tom Stoppard's play Jumpers. Her last Broadway appearance was in a 2006 revival of Barefoot in the Park.

In 1972, she appeared in the film adaptation of Philip Roth's novel Portnoy's Complaint. She appeared in various roles of episodic television before starring opposite Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor in 1976's Silver Streak. She stuck to comedy again the next year in Semi-Tough with Burt Reynolds and Kris Kristofferson.

In 1978, she got one of her strongest roles and her first Oscar nomination as a sudden divorcee in Paul Mazursky's An Unmarried Woman, the part which may be the best she ever put on screen, perfectly blending the shock, humor and pathos of a woman whose husband leaves her and is forced to re-enter the dating world.

In 1979, she co-starred with Burt Reynolds again in another comedy-drama concerning divorce, Starting Over, which brought her a second consecutive Oscar nomination. That same year, she starred in Bernardo Bertolucci's controversial Luna as a decidedly nontraditional mother and opera star and recent widow with an extremely close relationship with her teenage son.

In 1980, she had to choose between boyfriend Charles Grodin and her new stepmother's son (Michael Douglas) in It's My Turn. In 1981, she starred opposite Walter Matthau as the first woman Supreme Court justice in First Monday in October, ironically the same year the U.S. got its first woman Supreme Court justice. In 1982, she played a woman addicted to prescription medication in I'm Dancing As Fast As I Can.

After that, her screen and television appearances became less frequent, though she did have a particularly good guest shot on an episode of Law & Order as a divorce attorney in 1998 and a recurring role on Ally McBeal as Ally's mom. She received an Emmy nomination for a guest appearance on Nip/Tuck. She was a regular on Dirty Sexy Money.

Clayburgh was one of the many talents wasted in the film Running with Scissors. She will be seen later this month in Edward Zwick's Love and Other Drugs starring Jake Gyllenhaal. Another film featuring Clayburgh, Bridesmaids, directed by Paul Feig and starring Rose Byrne and Jon Hamm is due next year.

She is survived by her husband, the playwright David Rabe, and their daughter, the actress Lily Rabe.

RIP Ms. Clayburgh.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Burt Reynolds, De Niro, De Palma, Grodin, J. Gyllenhaal, Law and Order, M. Douglas, Matthau, Mazursky, Musicals, Obituary, Oscars, Roth, Stoppard, Television, Theater, Zwick

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Farrah Fawcett (1947-2009)

It seems as if most eras have their pinup girls and in the mid-'70s, that title undoubtedly belonged to Farrah Fawcett (who had a hyphenated Majors on the end of her name at the time). Fawcett lost her battle with cancer today at 62. The famous poster at the left sold a mind-boggling 8 million copies and led to her most famous role. Skyrocketing to superstardom as one of the original of Charlie's Angels in television's T&A era, like many sudden stars, she overestimated her fame and left the show after a single season, though she did return as Jill Munroe for a handful of episodes in later seasons as settlement of a breach of contract lawsuit. Her TV career didn't actually begin with that series though. She'd earlier appeared on Harry-O and The Six Million Dollar Man (with then-husband Lee Majors) as well as appearances on many other series and in feature films, most notably Logan's Run. Once she left Charlie's Angels, she tried her luck on the big screen, but critics and audiences were skeptical of the poster star as an actress or a movie star. She did work with talented performers (Jeff Bridges in Somebody Killed Her Husband, Charles Grodin and Art Carney in Sunburn and Kirk Douglas in Saturn 3), but none of it seemed to help. Around 1979, she and Majors separated and soon she dropped his last name.

She did get a hit with a film that didn't require acting opposite Burt Reynolds and Dom DeLuise in The Cannonball Run. Three years later though, she showed some acting chops when she went back to TV for the telefilm The Burning Bed, which earned her an Emmy nomination.

Two years after that, she repeated a success she'd had on stage with the film version of Extremities about a woman getting revenge on a rapist. She continued to prove her doubters wrong, earning two more Emmy nominations and making more features, good and bad, most notably Robert Duvall's The Apostle and Robert Altman's Dr. T and the Women.

Her perseverance was impressive given her off-screen travails with on-again/off-again love Ryan O'Neal, an abusive boyfriend and flaky talk show appearances before the devastating cancer that claimed her life. It was a long, hard climb from poster joke to respected actress, but Farrah Fawcett made it.

RIP Ms. Fawcett. You deserve the rest.

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Burt Reynolds, Duvall, Grodin, Jeff Bridges, K. Douglas, Obituary, Television

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, April 07, 2008

Made it, Ann. Top of the world!

By Edward Copeland

Seventy five years ago today, King Kong stomped onto movie screens for the first time. He's been back many times since in sequels and in two remakes, but the Merian C. Cooper/Ernest B. Schoedsack original remains the best.

It's a well-worn cliché that the journey trumps the destination in importance and that certainly proved to be the case with King Kong. If you went into the film blind, you might have no idea as to the story's direction. There's the one and only filmmaker Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong) with his "reputation for recklessness" setting out to film some sort of adventure on the fly on a mysterious, unchartered island. The only problem: He needs a female lead. Denham would be happy to ditch the romantic element, but you know those damn critics and audiences: You have to have a woman. The film drops hints here and there that the island may offer something bigger than just an exotic location. Denham acknowledges that he knows that something is "holding that island in the grip of fear. Something no white man has ever seen." Of course, because of Denham's reputation, no reputable agent will sacrifice a client to him, but thankfully (for Denham anyway) he stumbles upon the struggling Ann Darrow (Fay Wray) and talks her into enlisting in his voyage. He even gives her screen tests for gowns and shrieks while they sail and we get a preview of that scream, that delicious scream.

Of course, the all-male crew on the ship resent having a dame aboard as only men in a 1930s film could, but that doesn't stop Jack Driscoll (Bruce Cabot) from falling for Ann in a way only Hollywood's Golden Age would allow: Basically, give them one scene together of friction, then have them declare their love for each other. When Jack pours out his feelings for Ann, she says, "But Jack, you hate women!" "But you ain't women," he replies. When you really get deep into it, in many ways the later relationship that blooms between Kong and Ann might be more realistic and better developed. One thing I noticed this time (thanks to a DVD commentary by special effects legend Ray Harryhausen and visual effects wizard Ken Rolston) that never caught my attention before: Aside from the opening credits, Max Steiner's memorable score doesn't even begin until the ship arrives in the fog outside Skull Island.

Harryhausen makes a couple of other cogent points that should have occurred to me before: 1) If the natives built a wall big enough to keep Kong out, why did they add a gate big enough for him to come through? and 2) What happened to all the native women that had been sacrificed to Kong prior to Ann? Did he eat them? When Kong makes his first appearance, the stop-action movements bear a bit of a resemblance to the first shots of the Abominable Snowman coming over the mountain in the TV classic Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Sure, sometimes the scale misses the mark a bit in the effects (such as when the Loch Ness-type dinosaur flings bodies around), but I'd trade these primitive effects over bloated CGI anyday. In their running commentary (which really ranks as one of the best DVD commentaries I've heard and includes bits of archival interviews with Cooper and Wray), Harryhausen and Rolston express wonder at the magic conjured with the limited abilities of 1933 Hollywood. Rolston goes so far as to call King Kong the Jurassic Park of that generation (though I'd come up with a better movie example than that). "Everything today is reinventing the wheel," Harryhausen says. "And they are making it worse," Rolston replies. He's right.

As Harryhausen points out, the more they strive for realism, the more mundane movies become. They should strive to take us to another world such as the strange universe of Skull Island with its giant apes and still-living dinosaurs. The horrible 1976 remake and

Peter Jackson's bloated 2005 do-over both missed the magic of the 1933 version. The other night, the 1976 version aired on AMC and I caught parts of it, reminding me of how truly bad it was. It only had two things I thought improved on the other versions: It bothered to show how they actually transferred Kong on a ship back to New York and its equivalent of the Denham character (Charles Grodin) got what he deserved). Actually, one other plus to the 1976 version (I write this solely as a present for Josh R): The 1976 animatronic Kong had more realistic facial expressions

Peter Jackson's bloated 2005 do-over both missed the magic of the 1933 version. The other night, the 1976 version aired on AMC and I caught parts of it, reminding me of how truly bad it was. It only had two things I thought improved on the other versions: It bothered to show how they actually transferred Kong on a ship back to New York and its equivalent of the Denham character (Charles Grodin) got what he deserved). Actually, one other plus to the 1976 version (I write this solely as a present for Josh R): The 1976 animatronic Kong had more realistic facial expressions than Jessica Lange. Of course, if Kong had put his foot down with Armstrong, it would have deprived us of one of the classic closing lines in movie history. That's something else that the original doesn't get enough credit for: Its screenplay by James Creelman and Ruth Rose holds up much better than you'd expect in an action fantasy of this type. Just listen to the throwaway lines as jaded New York theatergoers crowd in to see Denham's show paying the then-outrageous ticket price of $20. I also love the little touches, such as when Kong breaks free of his arm restraints and then slowly and methodically undoes his other chains instead of just tearing them out in a fury. "A film is like an ink blot," Harryhausen says at another point in his DVD commentary. "It tells you more about the person watching it than the film itself." This proves most especially true about the 1933 King Kong, which deserves the title of the eighth wonder of the world, if only for finding pathos in a foot-and-a-half tall rubber puppet.

than Jessica Lange. Of course, if Kong had put his foot down with Armstrong, it would have deprived us of one of the classic closing lines in movie history. That's something else that the original doesn't get enough credit for: Its screenplay by James Creelman and Ruth Rose holds up much better than you'd expect in an action fantasy of this type. Just listen to the throwaway lines as jaded New York theatergoers crowd in to see Denham's show paying the then-outrageous ticket price of $20. I also love the little touches, such as when Kong breaks free of his arm restraints and then slowly and methodically undoes his other chains instead of just tearing them out in a fury. "A film is like an ink blot," Harryhausen says at another point in his DVD commentary. "It tells you more about the person watching it than the film itself." This proves most especially true about the 1933 King Kong, which deserves the title of the eighth wonder of the world, if only for finding pathos in a foot-and-a-half tall rubber puppet.Tweet

Labels: 30s, Grodin, J. Lange, Movie Tributes, Peter Jackson, Remakes

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, November 07, 2007

It's Alive...If Not Exactly Kicking

By Josh R

A gathering mob is gearing up to march on Frankenstein’s castle, for the purpose of dispensing bloody justice. Transylvanian peasants bearing torches and pitchforks? Not quite — these vigilantes hail from the village of Manhattan, and are consequently more likely to be seen sporting fashions from Barney’s Fifth Avenue than dirndls and lederhosen. They’re the New York theater critics, and Mel Brooks, be warned — the head they’re coming for is yours.

Following up a monster success is the trickiest proposition on Broadway, and filmdom’s favorite mad scientist and his crack team of specialists — which includes director-choreographer Susan Stroman and bookwriter Thomas Meehan — find themselves faced with the toughest act to follow since Lerner and Loewe ignited The Great White Way with their tale of a cockney flower girl being molded into a fairy-tale princess. The team responsible for My Fair Lady followed that mammoth 1956 hit with the much-maligned Camelot — a worthy if less-than-sparkling entry that wound up on the receiving end of a critical tongue-lashing when it made its Broadway bow four years later. Negative comparisons to a previous success are inevitable when the bar has been set ridiculously high, and any player who has hit a home run in the first inning is likely to be accused of underachieving at their next turn at bat (check out the reviews for Alice Sebold’s latest for evidence of how quickly the critics can turn on their darlings).

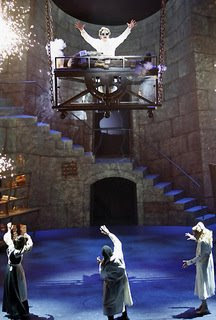

Which brings us to Young Frankenstein, a show that has borne the weight of expectations about as lightly as a donkey carrying an elephant on its back. The 2001 musical adaptation of Brooks’ cult classic The Producers was greeted with the kind of enthusiasm Catholics usually reserve for a visit from the pope — if not the return of the Messiah, bringing with him his apostles, the cure for all diseases and The Fab Four, reunited to record a sequel to The White Album (Paul and Ringo aren't dead yet, but you get the drift). Indeed, critics all but exhausted their catalog of superlatives in their attempts to encapsulate its genius — the cheering section was so loud it practically blew out the eardrums of anyone within arm’s reach of a newspaper kiosk.

Young Frankenstein marks Brooks’ second attempt at adapting one of his cinematic properties into a Broadway musical, and from the minute he announced his intentions to do so, the deck has been stacked against him. Regardless of what the finished product may have turned out to be — and I’ll arrive at that presently — it is going to be compared unfavorably to its predecessor; sight unseen, that was always going to be the case. The Magnificent Ambersons had the bad fortune to come on the heels of Citizen Kane, and was dismissed as “a lesser effort” even by the critics who praised it — such is the nature of the beast.

It must be duly reported that Young Frankenstein, which opens on Nov. 8 at The Hilton Theatre, invites no such parallel — Orson Welles followed up his 1941 masterpiece with another, albeit lesser masterpiece. Mr. Brooks, Ms. Stroman and Mr. Meehan have followed up their gold-plated achievement with something that is mostly amusing, largely derivative and pretty solidly OK. While there is nothing about the show to cause any offense to the film’s vast army of fans, or to prevent audiences with cash to burn from having a perfectly agreeable experience, nor can Brooks & Co. be credited with having created anything for the ages.

Going over the plot of Young Frankenstein would constitute the ultimate exercise in redundancy, as it is doubtful that anyone reading this is unfamiliar with the film on which it is based — or, in some cases, would have any trouble reciting it line-for-line. The stage version is incredibly (and often slavishly) faithful to the original film, which is essentially a farcical recapitulation of Hollywood’s bowdlerized version of the Frankenstein tale — it owes more to James Whale’s 1931 film adaptation, and its even loopier sequel, than it does to anything that the morbid Victorian Mary Shelley ever cranked out. Jokes have been added, sequences have been streamlined while others have been padded out, but the alterations don’t take the material in a different direction; this is your father’s Young Frankenstein, preserved in all its original silly splendor. All of the film’s most cherished bits of comic business — from the monster’s slapstick encounter with a blind hermit to the sublime absurdity of “Puttin' on the Ritz” — are present and accounted for, as is most of the original dialogue. Nothing is quite as funny as it was in the context of the film, but the laughs are still there, and for the most part, they still work. As a musical adaptation, Young Frankenstein translates more smoothly than expected — although not as seamlessly as The Producers, which had an actual show business theme and milieu to make use of. The wittily conceived musical numbers are interpolated with the content of the screenplay in ways that seem natural at times and awkward at others — for every song that seems like a logical extension of the original material, there’s an elaborate production number that seems superfluous. The songs, while largely undistinguished, are tuneful and amusing enough, even if the musical highlight remains “Puttin' on the Ritz,” which was written by Irving Berlin in 1929. All in all, while not perfect, the show that’s rattling its chains on the stage of the cavernous Hilton Theatre is basically up to snuff.

Which is not to say that something — more than one thing, actually — doesn’t get lost in the shuffle. Much of the appeal of the 1974 film came from manner in which it paid winking homage to 1930s Universal horror features, creating a look and feel in keeping with the tradition of Whale’s creepy classic and its progeny; on a stage as opposed to the screen, and in full color as opposed to black & white, the effect can't really be duplicated. The scenic design, while nothing if not elaborate, suggests the Haunted Mansion at Disney World more than Hollywood’s ghoulishly baroque take on middle-European villages and castles — similarly, the energetic chorus seems like a bunch of smiling, high-leaping refugees from an Oktoberfest-theme amusement park. As a result, what seemed naughty, clever and rude about the film version is, in the present context, rather cute. Now, I for one have an amazingly high tolerance level for cute — I can ingest large quantities of whipped cream without gagging on it (I had fun at Legally Blonde, for Chrissakes), and I can even stomach a heaping spoonful of the warm fuzzies (somehow I made it through all seven seasons of Gilmore Girls), but for a show that is striving to be crude, dirty fun with streak of zaniness, cute doesn’t go very far toward achieving the desired effect. Even though much of Brooks’ humor is rooted in gleefully bad taste, this Young Frankenstein often winds up feeling like a lavishly produced work of children’s theater with R-rated jokes.

Nor can the cast, as talented and resourceful as they are, really compete with the memory of their cinematic forebearers (although one comes surprisingly close). That notwithstanding, every principal player more than justifies his or presence on the bill — with the exception of the leading man, who labors mightily to put his own stamp on the role but whose energies seem largely misdirected.

That’s a nice way of saying that the casting of Roger Bart in the central role of Dr. Friedrich Frankenstein (pronounced Fronck-en-steen, if you please) represents something of a misfire. With his withered lips and anxious features, Bart is a born character actor whose deliciously sour charms have been put to wondrous good use in roles that require an element of sly superciliousness. This is not to say that he isn’t leading man material — rather that, for the purposes of what Brooks has in mind, he does not come ideally equipped for the assignment. On film, Gene Wilder used his wonderfully woebegone milquetoast quality as the set-up for a great punchline; the soft-spoken, put-upon schlemiel attains the wild-eyed, manic intensity of a raving lunatic when visions of monsters start dancing in his head — the transformation from colorless nebbish to shrieking loony-bird was as improbable as it was hysterical. Bart isn’t physically or vocally equipped to make a similar transition — everything about him is too sharp, too brittle, too overtly flamboyant, to start out small and then get bigger (it would be like directing Paul Lynde to imitate Charles Grodin). As a result, the manic intensity is there from the outset, leaving the actor with nowhere to go — this doctor seems less like someone inadvertently stumbling onto his own madness than one who’s been wearing it as a badge of honor from the very beginning. Gene Wilder got his laughs in the early stages of the film by speaking in the abashed tones of one who functions in a perpetual state of queasy uncertainty; Bart gets his by upping the volume and making faces.

If the man leading the charge comes up a bit lame, the supporting cast makes up some of the stagger. In the past, Sutton Foster’s technical proficiency as a singer and dancer has occasionally had the effect of making her seem a bit mechanical (as in: wind her up and she does theater). The role of Inga, the good doctor’s cheerfully oversexed laboratory assistant, allows her to loosen up and channel her inner dingaling, at least in the show’s early going — with her candy-colored dirndl and Marie Osmond grin, she suggests nothing so much as Gretel after having gorged herself on the witch’s gingerbread shingles and gone goofy from the sugar rush. She takes full advantage of the polka-inflected “Roll, Roll, Roll in the Hay,” bouncing happily around a rickety cart while delivering a master class in yodeling — she’s like a singing marionette in a glockenspiel that’s popped its springs and gone haywire. If the actress doesn’t manage to strike the same note of giddy abandon in the remainder of her scenes, it’s because her character becomes something of an afterthought — and her second act seduction number, “Listen to Your Heart,” is played a bit too earnestly to make much of an impression. The ever-dependable Andrea Martin scrunches up her features into an expression of constipated discomfort as the morose housekeeper, Frau Blucher — the very mention of whose name is enough to send listeners of the equine variety into fits of apoplexy. Dragging a chair across the floor with mincing steps, then straddling it like a chorine at the Kit Kat Club, she clowns her way decadently through the Weill-esque “He Vas My Boyfriend,” detailing the humiliation and abuse she suffered at the hands of her deceased paramour (naturally, while professing her love for every disgusting, degrading minute of it). She comes much closer to suggesting the stylized delivery of Lotte Lenya than Donna Murphy did in LoveMusik, while parodying it to wonderfully hilarious effect. Megan Mullally, as the doctor’s frigid fiancée who is brought to the threshold of ecstasy after a tumble with Ol’ Zipperneck, enjoys herself thoroughly with the extended dirty joke of “Deep Love” — a romantic ballad extolling the virtues of the monster’s considerable, ahem, proportions. While I found the actress a bit much to take during her decadelong stint as Will & Grace's booze-swilling socialite, for the purposes of this show she lowers her voice, maintains her shtick level at a nongrating setting and fits right in as the third member of the show’s trio of female clowns. If none reach the delirious heights of Cloris Leachman, Madeline Kahn and Teri Garr, they all know exactly how to get their laughs — and moreover, how to milk them.

Nor are the male members of the supporting cast in any danger of fading into the background. With his green facepaint and bulky frame, Shuler Hensley suggests an unlikely hybrid of Boris Karloff and The Incredible Hulk. As The Monster, he is a more visually menacing presence than Peter Boyle was, which is fortunately not so scary that he ceases to be funny. His tap-dancing solo in “Puttin' on the Ritz,” which wittily pits him opposite his own, attention-seizing shadow, constitutes the show’s comedic highpoint, and he gets a well-earned laugh at the end as well — even if you’ve heard Hensley sing before, after an evening of grunts and growls, the unveiling of his soaring operatic baritone comes as a deliciously funny shock. The doughy-featured Fred Applegate has a rather nonspecific quality as a performer, which allows him to double in two wildly different roles; while his wooden-limbed Inspector Kemp lacks the scenery-chewing officiousness of Kenneth Mars’ indelible screen creation, he more than makes up for it with his wistful blind hermit, who adopts an Al Jolson-like posture — working the jazz hands on bended knee — while praying to the heavens to “Please Send Me Someone.”

Standing head and shoulders above them all is the diminutive Christopher Fitzgerald, who minces and mugs his way through the role of Igor as if the fate of Western Civilization depended upon it. While perhaps the most unheralded member of the star-studded cast, this infinitely resourceful comic imp comes the closest of anyone to capturing the frenetic spirit of the original film, and is the evening’s unequivocal standout. Fitzgerald is a whirling dervish of energy, and even when relegated to the sidelines, his comic inventiveness never flags — he attacks the role with such unbridled enthusiasm that he practically flies through it. Marty Feldman, the original Igor, had a pointy chin and peepers the size of hard-boiled eggs, which he used to deliciously comic effect — Fitzgerald, while possessed of a more circumspect set of features, has an improbably ridiculous array of facial expressions that not only conjure up fond memories of the role’s originator, but give him the hyper-animated quality of a rubbery-faced cartoon character brought to three-dimensional life.

The actor, who is a true find, is by far the best thing about a show that seems to have been predestined to settle for second best. Brooks and his cohorts labor mightily to match the standard of their previous collaboration, and to a large extent, the strain shows; there are many moments — say, for example, when a song's lyrics include something on the order of “There is nothing like a brain” — when you can catch more than a slight whiff of desperation in the air. As for the most pressing question — is the show worth giving up next month’s rent in order to see (orchestra seats go at an obscene $450 a pop) — as your physician, I’d advise against it. Die-hard Brooks fans won’t really get anything they couldn’t get from popping in the DVD for the umpteenth time, and musical theater buffs should hold out for discount tickets; frankly, even if Dr. Brooks had re-animated the dead corpse of Ethel Merman for an encore performance of Gypsy, I’d have to swallow hard before shelling out $450 for the privilege of seeing her in action. The Producers was a once-in-a-lifetime phenomenon — Young Frankenstein, while a perfectly enjoyable light diversion, doesn’t really distinguish itself as anything beyond that. In its last outing, Team Brooks served up chocolate soufflé with a raspberry filling, drenched in rum sauce. This time, the result, while tasty, feels more like leftover Halloween candy — easily digested, and just as easily forgotten.

Tweet

Labels: Grodin, Karloff, Mel Brooks, Musicals, Television, Theater, Welles, Whale

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, January 27, 2006

King Loooooooooooooooong

Great special effects alone does not a good movie make. This is most decidedly the case with Peter Jackson's bloated remake of King Kong. As a general rule, I try to avoid remakes of good and great films on principle, but with the mostly positive reviews of King Kong, I finally relented and watched it. I should have stuck by my initial thoughts.

That's not to say there isn't a lot to admire in Jackson's film — as one would expect, the technical work is outstanding — but the 3 hour running time is absolutely ridiculous. I'm sure it might be possible to make a 3 hour thrill ride, but not when the main attraction of the ride doesn't show up until after an hour and 10 minutes of exposition.

Some critics have tried to make the comparison that Jackson's choice not to show us the great ape until more than an hour into the movie is akin to Steven Spielberg holding off on showing us the shark in Jaws. Setting aside the fact that the delay in showing the shark had more to do with technical problems than a plan, there are two important differences: 1) the shark is always a presence, even if you don't see it and 2) the surrounding story and characters are so involving in Jaws that it doesn't matter.

Unlike the Hobbitologists out there who believe that Jackson's Lord of the Rings trilogy was some kind of holy sign sent to humans in the form of three way-too-long movies, I wasn't a big fan of the films. I thought the first installment was good, but not great and I didn't care much for parts two and three, even while I admired parts of all the films.

It seems that getting away with three blockbusters in a row than ran more than three hours went to Jackson's head — because there is no reason King Kong needs to be this long. The great 1933 version told the whole story in barely more than 90 minutes — and it's still the best version. In fact, if it weren't for the great effects and outstanding art direction and cinematography, I can't say that Jackson's version is that substantially better than the 1976 remake.

I remember standing in line to see the 1976 version — I was 7 years old and had not yet developed my anti-remake philosophy — and though I eventually realized its lameness, it did have some things that were superior to Jackson's version. While Naomi Watts is a huge improvement on Jessica Lange, I can't say that Adrien Brody and Jack Black are really better than Jeff Bridges and Charles Grodin were in their similar 1976 roles.

In fact, Watts is probably the best non-effect in this movie. You have to suffer from a one-scene romance between her and Brody that really belongs in a movie of the 1930s, but thankfully Watts' Ann Darrow really seems to grow to care for the giant ape — and who can blame her? Kong has more charisma and depth than Brody's character does.

While there are some great action sequences, I found that even some of the effects looked phonier than they should — especially the dinosaur stampede on the island. (Sidenote: a friend of mine pointed out than in all the versions of this story, it's odd that everyone goes crazy about the giant ape but no one seems compelled to mention that there is an island that has living dinosaurs on it.)

Another thing that I think was a little better in the 1976 version is that it at least included scenes that showed Kong on the ship sailing back to New York. Jackson's version cheats — we see Kong passed out and captured, but there is nothing to indicate how they get him on the ship or if anything happens on the ship. The next scene has us back in New York for Kong's Broadway debut, though I'm sure Jackson probably has those scenes in the can for the inevitable extended 4-hour DVD version.

Don't get me wrong — I don't think the 1976 version was good either. In fact, the most memorable thing to come out of that version for me was a Colorform play kit that I wish I still had, if only to have a tangible, iconic version of the World Trade Center I could hold in my hands now.

Even though Jackson's film has made a lot of money, it's considered a financial disappointment in the United States. Hopefully, Jackson has learned a lesson — a movie doesn't have to be long just because you can get away with making it long.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Grodin, J. Lange, Jeff Bridges, Naomi Watts, Peter Jackson, Remakes, Spielberg

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE