Friday, August 03, 2012

Edward Copeland's Top 100 of 2012 (20-1)

Charlie Chaplin was audacious enough to continue making silent films (although he did allow for sound effects and an occasional song) all the way to 1936. In my opinion, he saved the Little Tramp's best for last in this hysterical tale of man vs. the modern age. The comedy is as funny as you'd expect and even more pointed than usual. Since Chaplin knew the Little Tramp was making his swan song, he even let him waddle off into the sunrise. Sound didn't stop Chaplin, who had two great sound efforts to come with The Great Dictator and Monsieur Verdoux. Still, his early works are the most precious gifts. Truly, his silence was golden.

When compiling the 2007 list, I feared it was becoming too Hitchcock-centric, forcing the omission of other great filmmakers but dammit, he made so many films that mean so much to me, it would be dishonest to place a quota on him. In the intervening five years, seeing Strangers several more times only has lifted it in my extreme. Hitch's directing gifts come off at his most stylish and Robert Walker's wondrous performance as the sensitive sociopath Bruno who expects the wimpy Farley Granger to live up to his part of a hypothetical murder deal remains chilling (and darkly funny) to this day. One of the biggest leaps from the last list.

Buster Keaton always shares the title with Charlie Chaplin as one of the two great silent clowns and The General continues to be Keaton’s masterpiece 85 years later. However, while it doesn’t lack for laughs, the film more accurately could be called an adventure than a comedy. The realism of the film’s Civil War setting also proves quite striking and even though Keaton’s character Johnny Gray fights for the Confederacy against the Union, neither side comes off as particularly villainous and the film doesn’t contain the racist elements of something like Birth of a Nation. The film’s humor stems from Johnny’s two loves: his train and the woman he longs for who won’t love him until he joins the war effort, even though he’s been rejected as a fighter because of his skills as an engineer. The General never grows old.

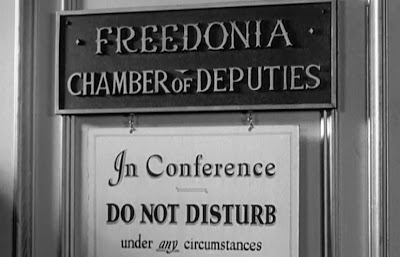

When Mickey (Woody Allen), depressed and suicidal, wanders into a movie theater in Hannah and Her Sisters, it's this inspired mixture of lunacy that brings him back around. After all, who can sit through Duck Soup and not feel better afterward. The question as to which Marx Brothers vehicle was the best got settled a long time ago and Duck Soup won. With its classic mirror scene and the loosest of plots designed to make the insanity of war look even crazier, I never get tired of Duck Soup. Watch it if only for the great Margaret Dumont. Remember, you are fighting for her honor, which is more than she ever did.

As a journalist, His Girl Friday contains one of my favorite nonsequiturs in the history of film. Delivered with frantic panache by Cary Grant as unscrupulous newspaper editor Walter Burns: "Leave the rooster story alone. That's human interest." Oh yeah, this may also be one of the funniest films ever made with rapid fire dialogue, a great sparring partner for Grant in Rosalind Russell and a priceless supporting cast to boot. It's the best remake ever made (and the film it was based on, The Front Page, is pretty damn good too). Making Hildy Johnson a woman and Burns' ex-wife was a stroke of genius. Besides, when you watch any version of this story where Walter and Hildy are both men, it's clear this isn't a platonic working relationship. I don't advise any more remakes (forget Switching Channels, if you can), but I wonder how it would play if the leads were two gay men?

As I wrote when marking the 100th anniversary of Reed's birth (forgive my self-plagiarism, but it makes this enterprise go faster), "Rewatching The Third Man recently, it once again captivated me from the moment the great zither music by Anton Karas begins to play over the credits.…If you haven't seen The Third Man (and shame on you if you call yourself a film buff and you haven't), watching the Criterion DVD really is the way to go, not only for a crisp print but to be able to compare the different versions offered for British and U.S. audiences (though only the different openings are included — we don't see what 17 minutes David Selznick cut for American audiences). With its great scenes of Vienna, sly performances and perhaps the greatest entrance of any character in movie history, The Third Man stays near the top of all films ever made, even nearly 60 years after its release."

I don’t know what I was thinking ranking Seven Samurai so low on my 2007 list. Having seen it a couple more times since, I’ve rectified that error. All films this long should hold their length as well as this rollicking adventure does. Each time I see it, it transfixes me from beginning to end. Hacks like Michael Bay should look to a film such as Seven Samurai and discover how characters trump stunts, explosions and special effects in great action-adventure films. It's amazing that with such a large cast, not just of the title samurai but of the farmers they defend as well, the actors and Kurosawa develop so many distinct and worthy portraits. Granted, the running time helps, but they establish characters rather quickly from Takashi Shimura (unrecognizable from his role as the dying bureaucrat in Ikiru) as the lead samurai organizing the mission to the brilliant Toshiro Mifune as Kikuchiyo, a reckless samurai haunted by his past as a farmer's son. Full of action, humor, sadness, a bit of romance and plenty of heart, its influence on so many films that have come since can’t be calculated.

Currently, we live in a time of a vicious circle: Movies inspire theatrical musicals which in turn become movie musicals (or in most cases, don't. Don't be looking for Leap of Faith: The Musical on the big screen anytime soon). Still, there was a time when musicals were created as motion pictures. Singin' in the Rain remains the very best example of one of those. The songs soar, the dance numbers inspire and the performances evoke joy. On top of that, it's even a Hollywood story, set in the awkward time between silent film and sound and milking plenty of laughs from the situation, especially through the spectacular performance of Jean Hagen as a silent superstar with a voice hardly made for sound and a personality barely suitable for Earth. Gene Kelly gives his best performance, a young Debbie Reynolds shines and Donald O'Connor makes us all laugh. Decades later, Singin' in the Rain got transformed (if that's the right word) a Broadway stage version. It wasn't very good. Stick with the movie.

When I wrote about this film for the Screenwriting Blog-a-Thon hosted by Mystery Man on Film in 2007, I said, "As far as I'm concerned, this film is Allen's masterpiece. Others will cite Annie Hall or Manhattan or some other titles and while I love Annie Hall and many others well, over time The Purple Rose of Cairo is the Allen screenplay that has reserved the fondest place in my heart. The screenplay isn't saddled with any extraneous scenes and no sequence falls flat as it builds toward its bittersweet ending. For me, it's Woody Allen's greatest screenplay and one of the best ever written as well." I've been pleasantly surprised at the number of people who have said to me since I wrote that how they agree, even among moviegoers who declare themselves not to like Woody Allen as a rule. It's the perfect blend of comedy, fantasy and realism and one of the greatest depictions of the magic of movies ever put on film. In The Purple Rose of Cairo, when Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels) and his pith helmet step off the screen, the repercussions end up being both hilarious, touching and painfully real.

While for me Jules and Jim stands as the high watermark of the French New Wave films, when you look objectively at the story of Jules and Jim, it may employ many of that movement's techniques but many aspects of Truffaut's film set it apart from its cinematic brethren such as its period setting and a time span that covers more than two decades separates it from the movement as well. However, that doesn’t affect the film’s magnificence. In a funny way, the 1962 film forecast the free love movement to come later that decade except its source material happened to be a semiautobiographical novel set in the early part of the 20th century. The prurience though lies in the mind of the fuddy duddy because part of what makes Jules and Jim so special comes from Truffaut's refusal to pass any judgment, be it positive or negative, upon the behavior of his characters. Despite the director's own criticism many years down the road that the film isn't cruel enough when it comes to love, the three main characters do suffer by the end but he doesn't paint it as punishment for their sins. In a 1977 interview, Truffaut said he thought he was "too young" when he made Jules and Jim. If he'd made it at any other age, it wouldn't be the same movie and probably wouldn't hold the same appeal for so many. For Jules and Jim to grab you, really grab you, I think you need to be young when you see it the first time, and that's why Truffaut, not yet 30 but captivated by the novel since 25, had to be young as well.

Wilder’s screenplay with Charles Brackett and D.M. Marshman Jr. proves surprisingly malleable, never fitting easily into one genre and playing differently in each viewing. It can be the darkest of Hollywood satires or the tragedy of a woman driven insane by a world that’s passed her by. Gloria Swanson’s brilliant performance as Norma Desmond can come off as a vulnerable madwoman or a master manipulator. Similarly, William Holden’s down-on-his-luck screenwriter Joe Gillis looks like a shallow opportunist in some scenes, an in-over-his-head dupe in others. The layers make Sunset Blvd. fresh and endlessly watchable. Wilder and his co-writers always produced great dialogue, but I believe Sunset Blvd. stands as Wilder’s greatest work as a director as well.

Hitchcock blessed us with so many classics, it’s hard to pick the best. This list contains seven Hitchcocks, but Rear Window stands tallest to me. I’ll allow two great directors to state my case. First, François Truffaut from The Films in My Life: “Rear Window is…a film about the impossibility of happiness, about dirty linen that gets washed in the courtyard; a film about moral solitude, an extraordinary symphony of daily life and ruined dreams." From David Lynch, as he wrote in Catching the Big Fish: “It's magical and everybody who sees it feels that. It's so nice to go back and visit that place." David, I couldn’t agree more.

Goodfellas rarely gets selected as the premier example of Scorsese’s brilliance as a filmmaker — and that’s a damn shame because, within its two hour and 20 minute running time, Goodfellas not only encapsulates Scorsese and filmmaking at their best but might be the director’s most personal film. If you wanted to demonstrate practically any aspect of moviemaking to a novice — editing, tracking shots, reverse pans, effective use of popular music — Scorsese disguised a film school in the form of this feature film about low-level gangsters. Goodfellas also happens to be the director’s most re-watchable film and, in a career stocked with masterpieces, it remains my favorite.

Every time I return to Paddy Chayefsky’s prescient screenplay, something new leaps out that I didn’t catch before. Most recently, it’s from one of Howard Beale’s monologues once he’s become the UBS network’s star. As part of the speech, delivered by the late, great Peter Finch, Beale tells his viewers, “Because you people, and 62 million other Americans, are listening to me right now. Because less than three percent of you people read books! Because less than 15 percent of you read newspapers!” Chayefsky died long before the Web revolution so remember that the next time someone blames the newspaper industry's death on the Internet. Better yet, watch Network and revel in the delicious words, magnificent ensemble and Lumet’s fine direction.

Many prefer the Kubrick of 2001: a Space Odyssey or later works such as A Clockwork Orange or Barry Lyndon, but I’ve always found him best when satirical, especially when that sharp humor took aim at the futility of war as in the underrated Full Metal Jacket, the great Paths of Glory and the best of the bunch, the incomparable Dr. Strangelove. To take the prospect of nuclear apocalypse instigated by a general driven mad by his impotence and produce one of the wall-to-wall funniest films ever was no small achievement, but having Peter Sellers in his multiple roles, Sterling Hayden and, most of all, George C. Scott’s hyperbolic, acrobatic and energetic work as Gen. Buck Turgidson, sure helped. That's not to mention Slim Pickens and Keenan Wynn as well and the surreal beauty of that closing of multiple mushroom clouds backed by that wonderfully ironic song.

So rarely does the best picture Oscar go to the best film, it always amazes me that the Academy recognized Casablanca (though for 1943, since it didn’t open in L.A. until a few months after its New York premiere). Claude Rains’ irreplaceable Captain Renault may say, “The Germans have outlawed miracles,” but the most miraculous thing of all was that a screenplay without an ending and based on an unproduced play managed to coalesce into the finest movie the Hollywood studio system ever produced. With a superb ensemble of character actors and stars delivering dialogue with more memorable lines than nearly any other film ever, courtesy of screenwriters Julius J. & Philip G. Epstein and Howard Koch, play it forever, Sam.

It does worry me that we seem to lack a filmmaker as ballsy as Robert Altman was (first person to suggest Paul Thomas Anderson gets punched in the face). Thankfully, he left us his body of work (some dogs to be certain, but the ecstasies we receive from his great ones allow us to forgive). For me, Nashville never wavers from its spot at the top of the Altman charts. It’s a musical, but not really. It’s about politics, but not really. We get to watch 24 characters intersect (or not) as Altman and screenwriter Joan Tewksbury design a tapestry displaying a picture of America on the eve of its bicentennial. It also presents ideas that in their own way prove as prescient as those in Network.

Many of the greatest films turn out to be examples of triumph over adversity and that certainly proved to be the case with Children of Paradise, Carné’s two-part masterpiece made during the Nazi occupation of France. When I wrote at length about this deceptively simple tale of mimes and actors, criminals and the aristocracy, I said that if I revised my 2007 list, the film likely would rise higher than its 18th rank. As you see, it most definitely has. Better to experience its beauty and magic than attempt to briefly describe it.

One wonders what the total would be if we calculated the number of words written extolling the brilliance and significance of Orson Welles’ filmmaking debut. Granted, the curmudgeons and contrarians exist and while not a day goes by that I don’t remind someone that all opinions are subjective by definition, Citizen Kane looms as the behemoth that practically defies that statement. Its status as a cinematic masterpiece comes close to being an objective truth. I have nothing new to add about this wonder. The film speaks for itself.

After what I wrote about Citizen Kane, you’d think it would rest in my top spot, but Renoir’s exquisite tragicomedy grabbed a foothold in my Top 10 as soon as I saw it in college and it took only one or two more viewings for Rules to clinch the No. 1 perch where it’s remained for more than two decades. Something personal within the film (too much identification with Renoir’s character of Octave; the character of Christine, who seems to cast a spell over all men who cross her path) hooks me in above and beyond the film’s artistry. If that explanation seems skimpy, I defer to what Octave says, "The awful thing about life is this: Everybody has their reasons."

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Carné, Carol Reed, Chaplin, Curtiz, Gene Kelly, Hawks, Hitchcock, Keaton, Kubrick, Kurosawa, Lists, Lumet, Renoir, Scorsese, Truffaut, Welles, Wilder, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, June 03, 2012

Closing on the House

"House's Head" undoubtedly stands as the most exciting and riveting hour the series ever produced, but the switch to its essential second half, "Wilson's Heart," may necessitate a move to a different pace but it more than compensates for that with its emotional impact. It provoked real sadness in having to bid farewell to the great character of Dr. Amber Volakis aka Cutthroat Bitch, so marvelously played by Anne Dudek — at least as a living, breathing role. You have to suspect that the decision-makers at House realized the mistake they made by not letting House hire her as part of his team. They did everything to keep bringing her back to the show, first as Wilson's girlfriend then as House's hallucination, even letting her reprise that role in the series finale. Dudek received more screentime in that final hour than Olivia Wilde's Thirteen did. Just imagine how much more entertaining those final three seasons could have been with Amber as a living member of the team.

The same quartet of writers who penned "House's Head" wrote "Wilson's Heart," though Katie Jacobs receives the directing reins. The second half of the story begins at a different New Jersey hospital — Princeton General — where Wilson and House find Amber hooked up to a ventilator, a heart monitor and various IVs. The attending physician, Dr. Richmond (Dan Desmond), informs them, "Her heart won't stop racing, no idea what's causing it." Ever the diplomat, House responds, "Sure it wasn't the bus that landed on her?" House wants to move Amber by ambulance immediately to Princeton-Plainsboro. Richmond, not in a mood to cooperate now, argues that House lacks the authority to make such a decision. "But her husband can," House responds, hinting at a spaced-out Wilson. "Move her!" Wilson insists. During the ambulance ride, while House works desperately to figure out what's wrong with Amber, the grief-stricken Wilson stays stuck on the question of why Amber was on the bus with House in the first place. “I’m not hiding anything, I just don’t remember,” House finally tells him in an attempt to get him to focus. As Amber starts to flatline, House prepares the defibrillators and it snaps Wilson back to the issue at hand. He urges House to stop. “Protective hypothermia,” Wilson suggests. House reminds Wilson that Amber's heart already has

stopped beating, why does he want to freeze her? Wilson's theorizes that since her heart has incurred damage, if they revived her now, they'd just be killing her brain as well. If they can lower her temperature, it can buy time for House to diagnose the problem. “This is not a solution. All you’re doing in pressing pause,” House argues, but Wilson stays adamant. "House, this is Amber! Please,” Wilson pleads to his friend. House tells him to pull the saline solution as he starts grabbing the ice packs. While a mystery (actually two) lie at the center of "Wilson's Heart," it doesn't play at the same pace as it did in "House's Head" because of the undercurrent of melancholy and higher stakes. At the hospital, they get her body cooled and Chase hooks her up to a heart-lung bypass while everyone gets to work trying to figure out a solution. Taub becomes the first brave enough to ask House if he and Amber had an affair, which House denies. "You can’t really say that if you can’t remember," Taub counters. "I lost four hours, not four months," House replies. Taub asks if House might have taken any drugs with her and House again doesn't think so, but agrees to Taub's suggestion of a tox screen. As Thirteen and Kutner search Wilson and Amber's apartment for any clues, Kutner stumbles upon a sex tape, prompting Thirteen to protest that none of them should be treating Amber in the first place. Treating a friend can cloud judgments, Thirteen says. Kutner reminds Thirteen that she didn't even like Amber. As House stares at the whiteboard, we see a sign of Ambers yet

stopped beating, why does he want to freeze her? Wilson's theorizes that since her heart has incurred damage, if they revived her now, they'd just be killing her brain as well. If they can lower her temperature, it can buy time for House to diagnose the problem. “This is not a solution. All you’re doing in pressing pause,” House argues, but Wilson stays adamant. "House, this is Amber! Please,” Wilson pleads to his friend. House tells him to pull the saline solution as he starts grabbing the ice packs. While a mystery (actually two) lie at the center of "Wilson's Heart," it doesn't play at the same pace as it did in "House's Head" because of the undercurrent of melancholy and higher stakes. At the hospital, they get her body cooled and Chase hooks her up to a heart-lung bypass while everyone gets to work trying to figure out a solution. Taub becomes the first brave enough to ask House if he and Amber had an affair, which House denies. "You can’t really say that if you can’t remember," Taub counters. "I lost four hours, not four months," House replies. Taub asks if House might have taken any drugs with her and House again doesn't think so, but agrees to Taub's suggestion of a tox screen. As Thirteen and Kutner search Wilson and Amber's apartment for any clues, Kutner stumbles upon a sex tape, prompting Thirteen to protest that none of them should be treating Amber in the first place. Treating a friend can cloud judgments, Thirteen says. Kutner reminds Thirteen that she didn't even like Amber. As House stares at the whiteboard, we see a sign of Ambers yet  to come as he experiences his first Amber hallucination. "Are you OK?” she asks as she appears in the office. House tries to ignore her and even recognizes that he's hallucinating. “What did we do last night?” She pours House a glass of sherry and continues. “Maybe she always had a thing for him…his mind, his blue eyes…” Dream Amber straddles his lap. "So maybe they decide to meet one night at an out of the way bar. Does that sound familiar? Do I feel familiar? What do you feel?” She whispers in his ear, “Electricity.” House awakens and limps to ICU. He wants to apply electrical impulses directly to the hypothalamus so he can evoke his detailed memories. Wilson and Cuddy don’t think it’s a good idea. Before House can experiment, everyone gets paged. Kutner found prescription diet pills containing amphetamines in vitamin jars. House wants to check manually if Amber's heart valves calcified and Chase prepares for open heart surgery, but Wilson stomps off, not looking pleased. As Chase puts drops in Amber's eyes, he notices that they are jaundiced. meaning liver failure. Diet pills don't do that so they return her to ICU. More diagnoses get posited, then pushed aside. Wilson just keeps pushing for cooling Amber down further, but Taub again becomes the voice of reason. He realizes he loves her, but cooling her down isn't going to save her. House gets stuck on the idea that Amber poured him a sherry in his hallucination. Kutner recalls that there's a bar near the crash site called Sherrie's. House orders them to keep Amber cool — he's taking

to come as he experiences his first Amber hallucination. "Are you OK?” she asks as she appears in the office. House tries to ignore her and even recognizes that he's hallucinating. “What did we do last night?” She pours House a glass of sherry and continues. “Maybe she always had a thing for him…his mind, his blue eyes…” Dream Amber straddles his lap. "So maybe they decide to meet one night at an out of the way bar. Does that sound familiar? Do I feel familiar? What do you feel?” She whispers in his ear, “Electricity.” House awakens and limps to ICU. He wants to apply electrical impulses directly to the hypothalamus so he can evoke his detailed memories. Wilson and Cuddy don’t think it’s a good idea. Before House can experiment, everyone gets paged. Kutner found prescription diet pills containing amphetamines in vitamin jars. House wants to check manually if Amber's heart valves calcified and Chase prepares for open heart surgery, but Wilson stomps off, not looking pleased. As Chase puts drops in Amber's eyes, he notices that they are jaundiced. meaning liver failure. Diet pills don't do that so they return her to ICU. More diagnoses get posited, then pushed aside. Wilson just keeps pushing for cooling Amber down further, but Taub again becomes the voice of reason. He realizes he loves her, but cooling her down isn't going to save her. House gets stuck on the idea that Amber poured him a sherry in his hallucination. Kutner recalls that there's a bar near the crash site called Sherrie's. House orders them to keep Amber cool — he's taking Wilson for a drink. When they get to the bar, the bartender recognizes House and assumes he's returned for his keys, which he gives to him. He asks if the bartender saw him with a blonde and if she appeared ill. The bartender remembers her sneezing. "Did you see the color of the sputum?" House inquires. "I assume sputum means snot? Look, I see a lot of drunk chicks in here. I didn't have time to stop and analyze the color of your girlfriend's boogers," the bartender replies. “She’s not my girlfriend genius,” House responds. “She was hot, you seemed into her and she bought you drinks. Last night she was your girlfriend,” the bartender insists. House ignores him and wonders if Amber already had an infection, but Wilson gets stuck on the bartender's comment. “You seemed into her?” Wilson repeats. “If he had a brain he wouldn’t be tending a bar,” House answers. After Taub and Foreman find some infiltrates and minor inflammation on the liver biopsy, House leaps to the conclusion that Hepatitis B lies at the root of the problem. "Start her on IV interferon. I'm going to tell Wilson." House tells Foreman. Noting how

Wilson for a drink. When they get to the bar, the bartender recognizes House and assumes he's returned for his keys, which he gives to him. He asks if the bartender saw him with a blonde and if she appeared ill. The bartender remembers her sneezing. "Did you see the color of the sputum?" House inquires. "I assume sputum means snot? Look, I see a lot of drunk chicks in here. I didn't have time to stop and analyze the color of your girlfriend's boogers," the bartender replies. “She’s not my girlfriend genius,” House responds. “She was hot, you seemed into her and she bought you drinks. Last night she was your girlfriend,” the bartender insists. House ignores him and wonders if Amber already had an infection, but Wilson gets stuck on the bartender's comment. “You seemed into her?” Wilson repeats. “If he had a brain he wouldn’t be tending a bar,” House answers. After Taub and Foreman find some infiltrates and minor inflammation on the liver biopsy, House leaps to the conclusion that Hepatitis B lies at the root of the problem. "Start her on IV interferon. I'm going to tell Wilson." House tells Foreman. Noting how obvious it is that his boss is running on fumes responds sarcastically, "Good idea and I'll go nap because I was concussed last night and had a heart attack this morning. I'll tell Wilson. You go sleep." Since when has House taken anyone's advice? He heads to the ICU where Amber opens her eyes, sits up straight and criticizes House for making such a "lame diagnosis" as Hepatitis B. She points to a red rash on her lower back. House wakes up in his office and says to himself, "I get less

obvious it is that his boss is running on fumes responds sarcastically, "Good idea and I'll go nap because I was concussed last night and had a heart attack this morning. I'll tell Wilson. You go sleep." Since when has House taken anyone's advice? He heads to the ICU where Amber opens her eyes, sits up straight and criticizes House for making such a "lame diagnosis" as Hepatitis B. She points to a red rash on her lower back. House wakes up in his office and says to himself, "I get less rest when I'm sleeping." He heads back to the ICU and gets help turning her and, sure enough, the red rash marks her back where the Dream Amber showed him. More speculating ensues. “We are not starting her heart until we’re 100 percent certain!” Wilson shouts. "We’re never 100 percent certain,” Foreman reminds him, then gets shocked when House sides with Wilson. "You know he’s wrong! You can’t change your mind just because a family member starts crying. They’re always scared!” Foreman argues. House insists on running blood cultures on the rash. Foreman goes to Cuddy and lets her in on what's going on, saying that Amber will die for sure if she doesn't step in. Wilson walks into the ICU as Foreman and Cuddy begin the process of warming Amber back up. Foreman says it's the only way to see if the antibiotics are working. Wilson spots the EEG readings. “Well done. We still don’t know what it is but you just let it spread to her brain!” He confronts Cuddy later in House's office. "This is exactly what I said would happen, it’s in her BRAIN now!" he yells at Cuddy."Brain involvement gives us a new symptom," she responds defensively. "That wouldn’t BE there if you hadn’t —" Wilson can't finish his sentence. "It’s where the disease was going, we needed to know that," Cuddy says. "This was not your decision to make!! You went behind MY back, you went behind House’s back!" Wilson chides her, halfway between anger and tears. The arguing awakens House, who stumbles his way into the middle of the mess pleading for "inside voices." Cuddy tells Wilson that House wanted to warm Amber up but that Wilson has guilted him into changing

rest when I'm sleeping." He heads back to the ICU and gets help turning her and, sure enough, the red rash marks her back where the Dream Amber showed him. More speculating ensues. “We are not starting her heart until we’re 100 percent certain!” Wilson shouts. "We’re never 100 percent certain,” Foreman reminds him, then gets shocked when House sides with Wilson. "You know he’s wrong! You can’t change your mind just because a family member starts crying. They’re always scared!” Foreman argues. House insists on running blood cultures on the rash. Foreman goes to Cuddy and lets her in on what's going on, saying that Amber will die for sure if she doesn't step in. Wilson walks into the ICU as Foreman and Cuddy begin the process of warming Amber back up. Foreman says it's the only way to see if the antibiotics are working. Wilson spots the EEG readings. “Well done. We still don’t know what it is but you just let it spread to her brain!” He confronts Cuddy later in House's office. "This is exactly what I said would happen, it’s in her BRAIN now!" he yells at Cuddy."Brain involvement gives us a new symptom," she responds defensively. "That wouldn’t BE there if you hadn’t —" Wilson can't finish his sentence. "It’s where the disease was going, we needed to know that," Cuddy says. "This was not your decision to make!! You went behind MY back, you went behind House’s back!" Wilson chides her, halfway between anger and tears. The arguing awakens House, who stumbles his way into the middle of the mess pleading for "inside voices." Cuddy tells Wilson that House wanted to warm Amber up but that Wilson has guilted him into changing his mind. “Heart. Liver. Rash. And now her brain,” Cuddy lays it out. House can't cover up the facts for his friend anymore. Autoimmune fits best," House admits, advocating warming Amber up. Wilson won't give up yet. He fears that if something else turns out to be the culprit, steroids could make her worse. He’s the attending, you’re the family. Go spend more time with the patient.” Cuddy tells him as gently as she can before leaving Wilson and House alone. "You can't do this," Wilson says, just shaking his head. "It’s not a good argument. It’s not an argument at all. I’m sorry,” House replies regretfully. Wilson kicks a chair and leaves, but he returns, seeming as if reason has returned to him. “Cuddy’s right. I was afraid to do anything. I thought if everything just stopped it’d be OK.” House tries to reassure him that it will be and tells him that Taub has begun treatment. Wilson then says they haven't tried everything and suggests House's earlier crazy idea about zapping his brain with electricity to see if he can jog loose any other clues. “You think I should risk my life to save Amber's?” House asks. Wilson nods and House lets out a joy-free laugh before nodding himself. Once he's strapped in and Chase inserts the voltage, he's transported back to Sherrie's bar, but the images come in black and white and without sound. "As long as I'm risking my life, I might as well be watching a talkie," House tells Chase, giving him the OK to up the voltage. Chase doesn't like the idea, but Wilson turns it up. House recalls the bartender taking his keys. He called Wilson to pick him up, but Wilson was on call and Amber

his mind. “Heart. Liver. Rash. And now her brain,” Cuddy lays it out. House can't cover up the facts for his friend anymore. Autoimmune fits best," House admits, advocating warming Amber up. Wilson won't give up yet. He fears that if something else turns out to be the culprit, steroids could make her worse. He’s the attending, you’re the family. Go spend more time with the patient.” Cuddy tells him as gently as she can before leaving Wilson and House alone. "You can't do this," Wilson says, just shaking his head. "It’s not a good argument. It’s not an argument at all. I’m sorry,” House replies regretfully. Wilson kicks a chair and leaves, but he returns, seeming as if reason has returned to him. “Cuddy’s right. I was afraid to do anything. I thought if everything just stopped it’d be OK.” House tries to reassure him that it will be and tells him that Taub has begun treatment. Wilson then says they haven't tried everything and suggests House's earlier crazy idea about zapping his brain with electricity to see if he can jog loose any other clues. “You think I should risk my life to save Amber's?” House asks. Wilson nods and House lets out a joy-free laugh before nodding himself. Once he's strapped in and Chase inserts the voltage, he's transported back to Sherrie's bar, but the images come in black and white and without sound. "As long as I'm risking my life, I might as well be watching a talkie," House tells Chase, giving him the OK to up the voltage. Chase doesn't like the idea, but Wilson turns it up. House recalls the bartender taking his keys. He called Wilson to pick him up, but Wilson was on call and Amber answered so she agreed to come fetch him. House talked Amber into one drink. He was so blotto that he forgot to take his cane or to pay the bill, but Amber went back and took care of both. House tells her to go home, he'll take the bus, but she boards the bus to return his cane. "Are you doing this for me or Wilson?" he remembers asking her. "Wilson," she answered. House salutes her. On the bus, House remembers Amber sneezing again and telling him she thought she was coming down with the flu. He then visualizes her reaching into her purse for pills — he yells in vain for her not to take them but she does and House has the answer and it isn't good news. The crash destroyed her kidneys and her body can't filter the drugs out of her system. Dialysis won't clear out the amantadine poisoning. Nothing can save Amber. House collapses, falling into a coma. Chase and a surgical team try to shock Amber's heart to no avail.

answered so she agreed to come fetch him. House talked Amber into one drink. He was so blotto that he forgot to take his cane or to pay the bill, but Amber went back and took care of both. House tells her to go home, he'll take the bus, but she boards the bus to return his cane. "Are you doing this for me or Wilson?" he remembers asking her. "Wilson," she answered. House salutes her. On the bus, House remembers Amber sneezing again and telling him she thought she was coming down with the flu. He then visualizes her reaching into her purse for pills — he yells in vain for her not to take them but she does and House has the answer and it isn't good news. The crash destroyed her kidneys and her body can't filter the drugs out of her system. Dialysis won't clear out the amantadine poisoning. Nothing can save Amber. House collapses, falling into a coma. Chase and a surgical team try to shock Amber's heart to no avail. Chase prepares to call the time of death, but Cuddy tells him not to do it but wake her up instead. “Wake her up? Just to tell her that she’s — that she’s — ” Wilson can’t speak the words. He places his hands over his faces. Cuddy put her hand on his shoulder. Wilson pulls Cuddy into a tear-soaked hug. “You are waking her up. So you can both say goodbye to each other. She would want it,” Cuddy tells him while still holding tight. Wilson eventually lets go and returns to ICU where Amber slowly opens her eyes. Cuddy keeps a solitary vigil by House's bedside. House's team prepares their farewells. "We should say goodbye," Thirteen suggests. "She didn't even like us," Taub says. "We liked her," Kutner declares. "Did we?" Taub asks. "We do now," Foreman responds. When Amber starts to come to, she remembers the bus crash. Wilson describes a little bit of what happened but when he mentions her liver and she sees how upset he is, Amber deduces the rest. “I’m dying,” she declares. The team comes by one at a time, not saying much, though Thirteen gives her a big hug that seems to take Amber

Chase prepares to call the time of death, but Cuddy tells him not to do it but wake her up instead. “Wake her up? Just to tell her that she’s — that she’s — ” Wilson can’t speak the words. He places his hands over his faces. Cuddy put her hand on his shoulder. Wilson pulls Cuddy into a tear-soaked hug. “You are waking her up. So you can both say goodbye to each other. She would want it,” Cuddy tells him while still holding tight. Wilson eventually lets go and returns to ICU where Amber slowly opens her eyes. Cuddy keeps a solitary vigil by House's bedside. House's team prepares their farewells. "We should say goodbye," Thirteen suggests. "She didn't even like us," Taub says. "We liked her," Kutner declares. "Did we?" Taub asks. "We do now," Foreman responds. When Amber starts to come to, she remembers the bus crash. Wilson describes a little bit of what happened but when he mentions her liver and she sees how upset he is, Amber deduces the rest. “I’m dying,” she declares. The team comes by one at a time, not saying much, though Thirteen gives her a big hug that seems to take Amber by surprise. Amber admits she's tired and wants to sleep, but Wilson begs her to hang on a little longer. "I’m always going to watch out for you, OK," she tells him. "I don’t think I can do it," Wilson starts to break and hold her tighter. "It's OK," she whispers. "It’s not OK. Why is it OK with you? Why aren’t you angry?” he asks as he tears up. “That’s not

by surprise. Amber admits she's tired and wants to sleep, but Wilson begs her to hang on a little longer. "I’m always going to watch out for you, OK," she tells him. "I don’t think I can do it," Wilson starts to break and hold her tighter. "It's OK," she whispers. "It’s not OK. Why is it OK with you? Why aren’t you angry?” he asks as he tears up. “That’s not the last feeling I want to experience,” she replies. Wilson pulls back and kisses her, then turns off the bypass machine. Amber stares at him for a second or two longer before her eyes slowly close. Wilson holds her and cries. House, meanwhile, remains in a coma with Cuddy asleep in the chair beside his bed, her hand gripping his. Inside his mind, House imagines himself on the bus again with Amber. He wears his hospital gown and they alone ride the vehicle. "You're dead," he says to her.

the last feeling I want to experience,” she replies. Wilson pulls back and kisses her, then turns off the bypass machine. Amber stares at him for a second or two longer before her eyes slowly close. Wilson holds her and cries. House, meanwhile, remains in a coma with Cuddy asleep in the chair beside his bed, her hand gripping his. Inside his mind, House imagines himself on the bus again with Amber. He wears his hospital gown and they alone ride the vehicle. "You're dead," he says to her. "Everybody dies," Amber points out. "Am I dead?" he asks her. "Not yet," Amber answers. "I should be," House declares. "Why?" she inquires. "Because life shouldn’t be random. This lonely misanthropic drug addict should die in bus crashes. And young do-gooders in love who get dragged out of their apartment in the middle of the night should walk away clean," he insists. "Self pity isn’t like you," Amber notes. "Yeah well, I’m branching out from self-loathing and self-destruction. Wilson is gonna hate me," House worries. "You kind of deserve it," Amber tells him. "He’s my best friend. I know. What now? Can I stay here with you?" he asks Amber. "Get off the bus," Amber suggests. "I can't," House claims. "Why not?" Amber

"Everybody dies," Amber points out. "Am I dead?" he asks her. "Not yet," Amber answers. "I should be," House declares. "Why?" she inquires. "Because life shouldn’t be random. This lonely misanthropic drug addict should die in bus crashes. And young do-gooders in love who get dragged out of their apartment in the middle of the night should walk away clean," he insists. "Self pity isn’t like you," Amber notes. "Yeah well, I’m branching out from self-loathing and self-destruction. Wilson is gonna hate me," House worries. "You kind of deserve it," Amber tells him. "He’s my best friend. I know. What now? Can I stay here with you?" he asks Amber. "Get off the bus," Amber suggests. "I can't," House claims. "Why not?" Amber wants to know. "Because…because it doesn't hurt here. Because I…I don't want to be in pain, I don't want to be miserable. And I don't want him to hate me," House admits. "Well…you can't always get what you want," Amber says, quoting his favorite philosopher. House stands up and walks to the exit of the bus. In his hospital room, his eyes open. "Hey, I'm here. Blink if you can hear me," Cuddy says to him. House blinks and starts to speak, but she tells him to rest. Later, Wilson looks in and he and House exchange

wants to know. "Because…because it doesn't hurt here. Because I…I don't want to be in pain, I don't want to be miserable. And I don't want him to hate me," House admits. "Well…you can't always get what you want," Amber says, quoting his favorite philosopher. House stands up and walks to the exit of the bus. In his hospital room, his eyes open. "Hey, I'm here. Blink if you can hear me," Cuddy says to him. House blinks and starts to speak, but she tells him to rest. Later, Wilson looks in and he and House exchange glances but no words. Wilson goes home. When he gets to his apartment, he finds a note on his bed from Amber telling him that she's gone to a bar to pick up a drunken House. What a triumphant two-hours of storytelling that made use of all its characters, giving us backgrounds on Kutner's past and Thirteen's future (as if we cared) and didn't even need guest stars. It also cemented more strongly the idea that perhaps there could be something romantic between Cuddy and House. In many ways, it marked the highpoint of the series. It had individual episodes that scored after that, but mostly the remaining years of the show involved a rollercoaster of quality. Still, I have one episode that ranks higher.

glances but no words. Wilson goes home. When he gets to his apartment, he finds a note on his bed from Amber telling him that she's gone to a bar to pick up a drunken House. What a triumphant two-hours of storytelling that made use of all its characters, giving us backgrounds on Kutner's past and Thirteen's future (as if we cared) and didn't even need guest stars. It also cemented more strongly the idea that perhaps there could be something romantic between Cuddy and House. In many ways, it marked the highpoint of the series. It had individual episodes that scored after that, but mostly the remaining years of the show involved a rollercoaster of quality. Still, I have one episode that ranks higher.

When I decided that the penultimate episode of House's inaugural season, the episode that won its creator David Shore an Emmy for outstanding writing in a drama series, deserved my top spot, I pondered how many great series produced their finest installments way back in the show's initial year of existence. The first example to pop into my head happened to be "Tuttle" from the first season of M*A*S*H, but with most other series I tend to think of best seasons and they usually come later, as was the case, in my opinion, with House as well. In fact, if I ranked the eight seasons of House from 1 to 8 with 1 being the best, I'd place them in this order:

I suppose the fact that my choice for my favorite of the series' 177 episodes (actually, the total should be 176, but they count the behind-the-scenes special "Swan Song" that aired before the "Everyone Dies" finale May 21) comes from my fourth-favorite of the series' seasons must speak volumes for the greatness of "Three Stories." As I've written earlier in this piece, I came to House late and didn't see the show in order, but the series didn't bother to explain from the beginning what caused the injury to Dr. Gregory House's leg and the genius of "Three Stories" stems from the fact that his "audience" of med students, literally representing the home viewer, don't realize at first

that the lessons he shares with them aren't simply situations they might face when they become doctors but that he's actually describing his own traumatic past. It all comes about simply enough when Cuddy informs him that usual doctor who presents the lecture, Dr. Reilly, "is throwing up. He obviously can't lecture." House, always looking for a way out of busy work asks her, "You witness the spew? Or you just have his word for it? I think I'm coming down with a little bit of the clap. May have to go home for a few days." She makes him give the lecture anyway and we're essentially rewarded for an hour with a command performance by Hugh Laurie as Dr. Gregory House, literally standing on a stage above his audience and holding us all in rapt attention. Before House gets to the auditorium, a face from his past stops him. His former girlfriend Stacy Warner (Sela Ward) approaches him. She knows he isn't happy to see her, but she needs his help with a case — her husband’s. He's been suffering from severe abdominal pain and fainting spells. They’ve gone to three doctors and nobody has answers. She gives House his file and begs him to think about it. "I know you're not too busy. You avoid work like the plague. Unless it actually is the plague. I'm asking you a favor," Stacy says. "I'm not too busy, but I'm not sure I want him to live. It's

that the lessons he shares with them aren't simply situations they might face when they become doctors but that he's actually describing his own traumatic past. It all comes about simply enough when Cuddy informs him that usual doctor who presents the lecture, Dr. Reilly, "is throwing up. He obviously can't lecture." House, always looking for a way out of busy work asks her, "You witness the spew? Or you just have his word for it? I think I'm coming down with a little bit of the clap. May have to go home for a few days." She makes him give the lecture anyway and we're essentially rewarded for an hour with a command performance by Hugh Laurie as Dr. Gregory House, literally standing on a stage above his audience and holding us all in rapt attention. Before House gets to the auditorium, a face from his past stops him. His former girlfriend Stacy Warner (Sela Ward) approaches him. She knows he isn't happy to see her, but she needs his help with a case — her husband’s. He's been suffering from severe abdominal pain and fainting spells. They’ve gone to three doctors and nobody has answers. She gives House his file and begs him to think about it. "I know you're not too busy. You avoid work like the plague. Unless it actually is the plague. I'm asking you a favor," Stacy says. "I'm not too busy, but I'm not sure I want him to live. It's good seeing you again," he replies as he limps past her on the way to the auditorium. Really, choosing "Three Stories" almost counts as a no-brainer on my part since the episode earned near-universal praise from critics and fans when it originally aired (Not that I noticed at the time). It completely upended not only what had becoming the formula for House but for any medical drama in history. With the seats of the auditorium a little more than half-full of fresh young faces wearing clean white coats (though the audience's size will wax and wane throughout the day(, House takes to the stage. "Three guys walk into a clinic. Their legs hurt. What's wrong with them?" House asks the students. One of the students — given the moniker Keen Student (Josh Zuckerman) in the script — shoots his hand into the air quickly. House gives him an annoyed glance. "I'm not going to like you, am I?" Don't misunderstand the statement I'm about to make about "Three Stories" — if you just skim the comment and don't pay attention to the context, you're liable to think I'm overrating this episode beyond the realm of good reason and judgment. However, I mean it with all sincerity when I equate "Three Stories" to episodic television drama as Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is to cinema. That doesn't mean that I think "Three Stories" stands as the greatest example of an hour of TV drama ever produced (I don't even think that about Citizen Kane in

good seeing you again," he replies as he limps past her on the way to the auditorium. Really, choosing "Three Stories" almost counts as a no-brainer on my part since the episode earned near-universal praise from critics and fans when it originally aired (Not that I noticed at the time). It completely upended not only what had becoming the formula for House but for any medical drama in history. With the seats of the auditorium a little more than half-full of fresh young faces wearing clean white coats (though the audience's size will wax and wane throughout the day(, House takes to the stage. "Three guys walk into a clinic. Their legs hurt. What's wrong with them?" House asks the students. One of the students — given the moniker Keen Student (Josh Zuckerman) in the script — shoots his hand into the air quickly. House gives him an annoyed glance. "I'm not going to like you, am I?" Don't misunderstand the statement I'm about to make about "Three Stories" — if you just skim the comment and don't pay attention to the context, you're liable to think I'm overrating this episode beyond the realm of good reason and judgment. However, I mean it with all sincerity when I equate "Three Stories" to episodic television drama as Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is to cinema. That doesn't mean that I think "Three Stories" stands as the greatest example of an hour of TV drama ever produced (I don't even think that about Citizen Kane in terms of film). I'm referring solely to its structure. As so many point out about Kane, no matter how many times you've seen it, you're never positive what scene comes next. Other films work that same way and so does "Three Stories." To begin with, the title of this episode of House happens to be both a complete misnomer and totally accurate at the same time. When House tells the med students that "three guys" walk into the clinic, those cases will merge and bleed together, one will be a young woman, another becomes Carmen Electra and soon not only the cases don't match the genders but they add up to more than three. On the other hand, in the larger scheme of things, the episode does concern itself with three stories: 1) House's lecture to the

terms of film). I'm referring solely to its structure. As so many point out about Kane, no matter how many times you've seen it, you're never positive what scene comes next. Other films work that same way and so does "Three Stories." To begin with, the title of this episode of House happens to be both a complete misnomer and totally accurate at the same time. When House tells the med students that "three guys" walk into the clinic, those cases will merge and bleed together, one will be a young woman, another becomes Carmen Electra and soon not only the cases don't match the genders but they add up to more than three. On the other hand, in the larger scheme of things, the episode does concern itself with three stories: 1) House's lecture to the students; 2) Stacy's return and her attempt to get House to take her husband's case; and 3) flashbacks to House's leg injury and Stacy's involvement in that. While it defies the structure of a typical House episode, "Three Stories" manages to blend most of the elements we've come to know and love, even this early in the show's run: the cynical humor, the pathos, the truth, the idiocy. "Three Stories" belongs in that rare section of television episodes that deserve the title masterpiece such as "Three Men and Adena" from the first season and "Black and Blue" from the second season of Homicide: Life on the Street. "Guy Walks Into an

students; 2) Stacy's return and her attempt to get House to take her husband's case; and 3) flashbacks to House's leg injury and Stacy's involvement in that. While it defies the structure of a typical House episode, "Three Stories" manages to blend most of the elements we've come to know and love, even this early in the show's run: the cynical humor, the pathos, the truth, the idiocy. "Three Stories" belongs in that rare section of television episodes that deserve the title masterpiece such as "Three Men and Adena" from the first season and "Black and Blue" from the second season of Homicide: Life on the Street. "Guy Walks Into an Advertising Agency" from season three and "The Suitcase" from season four of Mad Men. Too many episodes of The Sopranos, Deadwood and Breaking Bad would qualify. The Wire plays like one long episode to me so I can't even separate it into chapters. "Three Stories" separates itself from every other House episode (even some later attempts to abandon chronological order) by defying the need for synopsis or highlights. It's not because I'd give away spoilers — it's because if you've never watched an episode of House before, watch "Three Stories." The series hooked me in that hospital bed before I ever caught up with this episode, but I find it hard to imagine anyone watching this episode of House and not coming back for more. I will share a handful of the episode's best quotes, since House as teacher makes for an interesting idea. "It is in the nature of medicine, that you are gonna screw up. You are gonna kill someone. If you can't handle that reality, pick another profession. Or, finish medical school and teach."; "I'm sure this goes against everything you've been taught, but right and wrong do exist. Just because you don't know what the right answer is — maybe

Advertising Agency" from season three and "The Suitcase" from season four of Mad Men. Too many episodes of The Sopranos, Deadwood and Breaking Bad would qualify. The Wire plays like one long episode to me so I can't even separate it into chapters. "Three Stories" separates itself from every other House episode (even some later attempts to abandon chronological order) by defying the need for synopsis or highlights. It's not because I'd give away spoilers — it's because if you've never watched an episode of House before, watch "Three Stories." The series hooked me in that hospital bed before I ever caught up with this episode, but I find it hard to imagine anyone watching this episode of House and not coming back for more. I will share a handful of the episode's best quotes, since House as teacher makes for an interesting idea. "It is in the nature of medicine, that you are gonna screw up. You are gonna kill someone. If you can't handle that reality, pick another profession. Or, finish medical school and teach."; "I'm sure this goes against everything you've been taught, but right and wrong do exist. Just because you don't know what the right answer is — maybe there's even no way you could know what the right answer is — doesn't make your answer right or even OK. It's much simpler than that. It's just plain wrong."; "This buddy of mine, I gotta give him ten bucks every time somebody says 'Thank you.' Imagine that. This guy's so good, people thank him for telling them that they're dying.…I don't get thanked that often… It's a basic truth of the human condition that everybody lies. The only variable is about what. The weird thing about telling someone they're dying is it tends to focus their priorities. You find out what matters to them. What they're willing to die for. What they're willing to lie for." Also, pertaining to his real-life situation when an aneurysm caused an infarction in his leg muscle, killing the muscle. Cuddy and Stacy advise amputating his leg to save House's life, but House refuses despite the risks. "I like my leg. I've had it for as long as I can remember," House

there's even no way you could know what the right answer is — doesn't make your answer right or even OK. It's much simpler than that. It's just plain wrong."; "This buddy of mine, I gotta give him ten bucks every time somebody says 'Thank you.' Imagine that. This guy's so good, people thank him for telling them that they're dying.…I don't get thanked that often… It's a basic truth of the human condition that everybody lies. The only variable is about what. The weird thing about telling someone they're dying is it tends to focus their priorities. You find out what matters to them. What they're willing to die for. What they're willing to lie for." Also, pertaining to his real-life situation when an aneurysm caused an infarction in his leg muscle, killing the muscle. Cuddy and Stacy advise amputating his leg to save House's life, but House refuses despite the risks. "I like my leg. I've had it for as long as I can remember," House declares. He wants a bypass to attempt to restore circulation. When that surgery doesn't completely succeed, House suffers a heart attack. He requests to be put in a temporary coma to get through the pain. Stacy, acting as his medical proxy, tells Cuddy to take the middle ground between amputation and a bypass, so they remove as much of the dead muscle tissue as possible, leaving House as the limping, pain-afflicted man we know. At last, I've finished. There were many episodes I wanted to talk about, lines I wished to quote, points I wanted to make. Oh, well. Arrivederci House and Wilson — riding those motorcycles out there somewhere. Let's hope those five months last awhile and when you two find yourselves alone, you won't be as broken as everyone who stepped into Princeton-Plainsboro Teaching Hospital seemed to be. Greg House's problems grabbed the spotlight, but the true theme of House was healing in every sense of the word and it wasn't just the patients who needed fixing. All staff members were damaged. Not just House, but Wilson, Cuddy, Foreman, Cameron, Chase, Taub, Park, etc. House always tried to get the old band together again because what would his life be likewithout his dysfunctional relatives? What will ours be like without his?

declares. He wants a bypass to attempt to restore circulation. When that surgery doesn't completely succeed, House suffers a heart attack. He requests to be put in a temporary coma to get through the pain. Stacy, acting as his medical proxy, tells Cuddy to take the middle ground between amputation and a bypass, so they remove as much of the dead muscle tissue as possible, leaving House as the limping, pain-afflicted man we know. At last, I've finished. There were many episodes I wanted to talk about, lines I wished to quote, points I wanted to make. Oh, well. Arrivederci House and Wilson — riding those motorcycles out there somewhere. Let's hope those five months last awhile and when you two find yourselves alone, you won't be as broken as everyone who stepped into Princeton-Plainsboro Teaching Hospital seemed to be. Greg House's problems grabbed the spotlight, but the true theme of House was healing in every sense of the word and it wasn't just the patients who needed fixing. All staff members were damaged. Not just House, but Wilson, Cuddy, Foreman, Cameron, Chase, Taub, Park, etc. House always tried to get the old band together again because what would his life be likewithout his dysfunctional relatives? What will ours be like without his?

..

Labels: Awards, Breaking Bad, Deadwood, Homicide, House, Lists, Mad Men, The Sopranos, The Wire, TV Tribute, Welles

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, May 08, 2012

Puttering all around the house

It occurs to me that I haven't bothered to even attempt to summarize the plot of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Partly, that's because Stephen Sondheim's song "Comedy Tonight" spells out most of the characters pretty well, but mainly it's because the shenanigans that Larry Gelbart and Burt Shevelove cooked up out of surviving Plautus works contain so many complications that it would

prove damn difficult to synopsize. However, I do feel that one character in particular — Erronius — deserves separate mention since he didn't get a song of his own. In Finishing the Hat, Sondheim provides the lyrics for a cut song that had been intended for the character called "A Gaggle of Geese," which referred to his family's crest that appears on rings worn by his long-lost children, kidnapped decades earlier by pirates. He, however, persists in searching for his son and daughter. In the original Broadway production, Raymond Walburn, who made his Broadway debut in 1914 and his film debut in 1916, played the role. He played the butler Walter in Frank Capra's Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. In the 1972 revival, the part went to Reginald Owen, who first appeared on Broadway in 1925, though he started making movies in 1911 where his most famous role probably remains Scrooge in the 1938 version of A Christmas Carol. In the 1966 film version, the Erronius role found a masterful custodian in the great Buster Keaton, making his final film appearance. The reason I chose the photo above from the 1996 revival wasn't based solely on availability but because it shows its Erronius, William Duell, who just passed away in December. A very recognizable character actor of stage and screen, Duell appeared in both the original production, revival and film of 1776 as well as one of the patients in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. For many though, he'll always remain Johnny the shoeshine boy from TV's Police Squad!

prove damn difficult to synopsize. However, I do feel that one character in particular — Erronius — deserves separate mention since he didn't get a song of his own. In Finishing the Hat, Sondheim provides the lyrics for a cut song that had been intended for the character called "A Gaggle of Geese," which referred to his family's crest that appears on rings worn by his long-lost children, kidnapped decades earlier by pirates. He, however, persists in searching for his son and daughter. In the original Broadway production, Raymond Walburn, who made his Broadway debut in 1914 and his film debut in 1916, played the role. He played the butler Walter in Frank Capra's Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. In the 1972 revival, the part went to Reginald Owen, who first appeared on Broadway in 1925, though he started making movies in 1911 where his most famous role probably remains Scrooge in the 1938 version of A Christmas Carol. In the 1966 film version, the Erronius role found a masterful custodian in the great Buster Keaton, making his final film appearance. The reason I chose the photo above from the 1996 revival wasn't based solely on availability but because it shows its Erronius, William Duell, who just passed away in December. A very recognizable character actor of stage and screen, Duell appeared in both the original production, revival and film of 1776 as well as one of the patients in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. For many though, he'll always remain Johnny the shoeshine boy from TV's Police Squad! After all the excised songs and subplots, the restoration of said subplots, tensions causing everyone to blame each other for the problems (such as when Shevelove yelled at Sondheim, pointing to his songs as the main reason for the show's failings) and strained relations leftover from the blacklist, the audiences loved it and most reviews praised it. Looking back at those 1962 New York reviews, thanks to a friend with access to them since The New York Times alone provides easy

online access to its archives, not only do the critics provide interesting insight into the show's reception but it's amazing to see how many newspapers that city supported in 1962. Few of the critics, while acknowledging A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum entertained them immensely, wrote much — if anything — about Sondheim's score. The morning after it premiered, Howard Taubman, chief drama critic for The Times since Brooks Atkinson's retirement in 1960, wrote, "Know what they found on the way to the forum? Burlesque, vaudeville and a cornucopia of mad, comic hokum. The phrase for the title of the new musical comedy that arrived at the Alvin last night might be, caveat emptor. A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum indeed! No one gets to the forum; no one even starts for it. And nothing really happens that isn't older than the forum, more ancient than the agora in Athens. But somehow, you keep laughing as if the old sight and sound gags were as good as new. As for the score, Taubman said, "Mr. Sondheim's songs are accessories to the pre-meditated offense. With the Messrs. Mostel, Gilford, Burns and Carradine as a coy foursome, 'Everybody Ought to Have a Maid' recalls the days when delirious farceurs like the Marx Brothers could devastate a number. When Mr. Mostel, the slave with a nimble mind and a desire to be free, persuades Mr. Gilford, the nervous straw boss of the slaves, to don virgin's white, the two convert the show's romantic and pretty 'Lovely' into irresistible nonsense." Taubman penned one of the kinder notices to Sondheim's songs though he appears to have missed the point that even the first version of "Lovely" sung by the story's virginal courtesan Philia comes steeped in satire as the beauty sings an ode to superficiality and her own bubbleheadedness. (The first link takes you to Preshy Marker's version from 1962, the second to Jessica Boevers' from the 1996 revival; since I used the 1962 recording of "Everybody Ought to Have a Maid" at the beginning of the first half, this link goes to the BBC Proms rendition by Daniel Evans, Julian Ovendon, Simon Russell Beale and Bryn Terfel.) The score's assessment changes over the years and as of today, Sondheim may remain the toughest critic. In his book, he again wrote, "I made the subtle, though thankfully not fatal, error of being witty instead of funny." Below, watch a quite different take on "Lovely" from Putting It Together as performed by Carol Burnett and Ruthie Henshall.

online access to its archives, not only do the critics provide interesting insight into the show's reception but it's amazing to see how many newspapers that city supported in 1962. Few of the critics, while acknowledging A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum entertained them immensely, wrote much — if anything — about Sondheim's score. The morning after it premiered, Howard Taubman, chief drama critic for The Times since Brooks Atkinson's retirement in 1960, wrote, "Know what they found on the way to the forum? Burlesque, vaudeville and a cornucopia of mad, comic hokum. The phrase for the title of the new musical comedy that arrived at the Alvin last night might be, caveat emptor. A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum indeed! No one gets to the forum; no one even starts for it. And nothing really happens that isn't older than the forum, more ancient than the agora in Athens. But somehow, you keep laughing as if the old sight and sound gags were as good as new. As for the score, Taubman said, "Mr. Sondheim's songs are accessories to the pre-meditated offense. With the Messrs. Mostel, Gilford, Burns and Carradine as a coy foursome, 'Everybody Ought to Have a Maid' recalls the days when delirious farceurs like the Marx Brothers could devastate a number. When Mr. Mostel, the slave with a nimble mind and a desire to be free, persuades Mr. Gilford, the nervous straw boss of the slaves, to don virgin's white, the two convert the show's romantic and pretty 'Lovely' into irresistible nonsense." Taubman penned one of the kinder notices to Sondheim's songs though he appears to have missed the point that even the first version of "Lovely" sung by the story's virginal courtesan Philia comes steeped in satire as the beauty sings an ode to superficiality and her own bubbleheadedness. (The first link takes you to Preshy Marker's version from 1962, the second to Jessica Boevers' from the 1996 revival; since I used the 1962 recording of "Everybody Ought to Have a Maid" at the beginning of the first half, this link goes to the BBC Proms rendition by Daniel Evans, Julian Ovendon, Simon Russell Beale and Bryn Terfel.) The score's assessment changes over the years and as of today, Sondheim may remain the toughest critic. In his book, he again wrote, "I made the subtle, though thankfully not fatal, error of being witty instead of funny." Below, watch a quite different take on "Lovely" from Putting It Together as performed by Carol Burnett and Ruthie Henshall.Let's skip quickly through some excerpts from the other opening night reviews. Remember: Each of these came from New York newspapers and many no longer exist. Still, today, when some major cities fail to support one daily newspaper to think that this many could thrive in a single city, albeit one as large as New York, makes an old ex-journalist such as myself fill with both wonder and sadness. Walter Kerr for The New York Herald Tribune: "The funny thing about A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum is that it's

funny. I'm not going to tell you it's anything more than that, but maybe I don't have to. For all I know, you like funny musicals. You may even like classical funny musicals, and this one is very classic.…Composer Stephen Sondheim begins by giving his lightfooted fools some rather odd recitative as substitute for melody and same vaguely Oriental wood-block effects as substitute for lively accompaniment. You wonder. Then, with a foursome in which Mr. Mostel, Mr. Burns, Mr. Gilford and a borrowed scarecrow named John Carradine, take off to a tune called 'Everybody Ought to Have a Maid,' the odd figurations Mr. Sondheim is attracted to begin to pay off. There's a faint edge of musical sarcasm to be dealt with here, and it crops up again — most effectively — in 'I'm Calm,' 'Impossible,' 'That Dirty Old Man,' and in Mr, Mostel's swooning reprise of a number that was mocking in the first place, "Lovely." The score is in and out, but wins out. The lyrics are fine. Is it me or does it seem as if Kerr keeps changing his mind as he's writing? Though a Broadway theater remains named after the critic today, I've always been leery of Kerr since he actively participated in the industry as a writer, director and lyricist at the same time he worked regularly as a critic. At least he recognized the humor in the first version of "Lovely" though, I'll give him that. (Isn't it fascinating to imagine that Broadway theater owners sometimes honor critics this way? A theater bears Brooks Atkinson's name as well and they even awarded him a special Tony after he retired. When will we see The Frank Rich Theater? Can you imagine and honorary Oscar to a film critic?) The links: "Everybody Ought to Have a Maid" from 1966 film; "Impossible" from the 1996 revival recording; "I'm Calm" and "That Dirty Old Man" both from the 1962 original cast recording. Below we have the clip from the poorly shot bootleg of the "Lovely" (reprise) from the 1996 revival performed by Nathan Lane and Mark Linn-Baker.

funny. I'm not going to tell you it's anything more than that, but maybe I don't have to. For all I know, you like funny musicals. You may even like classical funny musicals, and this one is very classic.…Composer Stephen Sondheim begins by giving his lightfooted fools some rather odd recitative as substitute for melody and same vaguely Oriental wood-block effects as substitute for lively accompaniment. You wonder. Then, with a foursome in which Mr. Mostel, Mr. Burns, Mr. Gilford and a borrowed scarecrow named John Carradine, take off to a tune called 'Everybody Ought to Have a Maid,' the odd figurations Mr. Sondheim is attracted to begin to pay off. There's a faint edge of musical sarcasm to be dealt with here, and it crops up again — most effectively — in 'I'm Calm,' 'Impossible,' 'That Dirty Old Man,' and in Mr, Mostel's swooning reprise of a number that was mocking in the first place, "Lovely." The score is in and out, but wins out. The lyrics are fine. Is it me or does it seem as if Kerr keeps changing his mind as he's writing? Though a Broadway theater remains named after the critic today, I've always been leery of Kerr since he actively participated in the industry as a writer, director and lyricist at the same time he worked regularly as a critic. At least he recognized the humor in the first version of "Lovely" though, I'll give him that. (Isn't it fascinating to imagine that Broadway theater owners sometimes honor critics this way? A theater bears Brooks Atkinson's name as well and they even awarded him a special Tony after he retired. When will we see The Frank Rich Theater? Can you imagine and honorary Oscar to a film critic?) The links: "Everybody Ought to Have a Maid" from 1966 film; "Impossible" from the 1996 revival recording; "I'm Calm" and "That Dirty Old Man" both from the 1962 original cast recording. Below we have the clip from the poorly shot bootleg of the "Lovely" (reprise) from the 1996 revival performed by Nathan Lane and Mark Linn-Baker.Others who opined about opening night. Unless they took contrarian views on the show itself, I'm limiting the comments to the score.: Except for calling Forum a musical comedy in his lead, the only other reference to the score Richard Watts Jr. made in The New York Post comes as part of the review's penultimate sentence. "…and Stephen Sondheim’s score is modest but pleasant." John McClain wrote in The Journal American, "Zero Mostel, a very animated blimp, will personally defy you not to like A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum…The clients laughed and seemed to enjoy themselves, but there was always the suggestion that had they not, Mr. Mostel would have passed among them and belabored them with a baseball bat. He is quite largely the whole show… The book by Burt Shevelove and Larry Gelbart (claiming some debt to Plautus) is a wispy affair, and Stephen Sondheim's score is less than inspired,

but under George Abbott's slick direction the show moves and the audience roars. I should think it would succeed." At The New York Daily News, John Chapman chimed in, "(The performers) are grand muggers, leerers and slapstickers, and any old vaudeville fan will be happy to see them in operation.…The songwriter, Stephen Sondheim, comes up with an occasional bright and funny number, such as the four burlesquers song 'Everybody Ought to Have a Maid,' and Miss Kobart’s venomous hymn to Burns, 'That Dirty Old Man of Mine.'" Did he not look at his Playbill? How did he get the song title wrong? Links: "Everybody Ought to Have a Maid" performed by Carol Burnett and Bronson Pinchot in Putting It Together; "That Dirty Old Man" from 1996 revival cast recording. Another critic who didn't find it important to check song titles was Norman Nadel in The New York World Telegram, who delivered the harshest review I read. "But too high a price must be paid for entertaining moments in A Funny Thing… Much of the comedy repeats itself. Some of the players work so hard to exploit their thin materials that they generate more sympathy than laughter. The show is slow starting and sometimes heavy-footed. Stephen Sondheim’s music would have been a second-rate score even in 1940, but he has come up with some catchy lyrics. One is “All I Know is Lovely,” sung by Ms. Marker and Mr. Davies. Another is 'Bring Me My Bride,' in which Miles proclaims his own glory; this is done resonantly by baritone Holgate.…There are indications at the Alvin that A Funny Thing might have been an earthy, boisterous delight. From time to time, it is. For the most part, however, it strains too hard to achieve too little." Link: "Bring Me My Bride" from original 1962 cast recording; I've run out of versions of "Lovely." Finally, we get to Robert Colman reviewing at The New York Mirror with the nicest words for Sondheim's score. "Stephen Sondheim has supplied a score that falls pleasantly on the ears. Jack Cole has choreographed dances that would have delighted Billy Minsky’s. We suspect that A Funny Thing will prove the most controversial song-and-dancer of the season. You’ll either love it or loathe it. In our book, it looms as a hot ticket. A riotous and rowdy hit." The retired Brooks Atkinson filed a "critic at large" piece for The New York Times in July where he barely mentions that Forum contains music and Sondheim's name never appears, though the "low comedy" delights him to no end. Since "Everybody Ought to Have a Maid" comes up so often, I've reserved two video clips for you to watch. The first comes from the 1996 revival.