Thursday, September 01, 2011

From the Vault: A Midnight Clear

Few recent films deserve to be called poetic. A Midnight Clear earns that description, though if the movie were actually a poem it would a couple of stanzas too long.

Ethan Hawke narrates as Will Knott, a young Army sergeant stationed with an intelligence unit near the border of France and Germany in World War II. Adapted by director Keith Gordon from William Wharton's novel, A Midnight Clear invokes an almost hypnotic presence as it invigorates the familiar film terrain of young men in battle.

Knott and the five remaining members of his unit are, in many ways, stock characters, but the script and performers bring the young men to vivid life.

In addition to Hawke, A Midnight Clear features the young actors Peter Berg, Kevin Dillon, Frank Whaley, Arye Gross and Gary Sinise. All do well playing men who find a sliver of hope in a dreadful situation.

What makes the film's portrayal of youth at war so refreshing is that not only are the American soldiers uncertain of their European purpose, so are the German troops they encounter while on reconnaissance.

It's Christmas 1944 and the men are sent by their major (John C. McGinley, whose overplaying of the requisite jerk officer is the film's weakest element) to an abandoned house to search for a lost patrol, who were presumably captured or killed by German troops.

Once there, besides enjoying comparatively luxurious housing, they also discover the nearby presence of several German soldiers, who at first seem to be taunting them but soon reveal other purposes.

The film produces many startling images such as corpses in the frozen woods, a forest where one can never be certain where a sound is coming from. Even Hawke's voiceover narration ends up being an above-average example of this overused technique.

The plot's developments, surprising even though the eventual outcome seems telegraphed, occur so clearly and so wonderfully that they inspire. The perfect mood and individual scenes mesmerize to such an extent that the structure seems too fragile to survive. If the film had ended 15 minutes sooner, the mood would have been preserved and A Midnight Clear would have been a perfect tone poem of a film.

Unfortunately, the film goes on. McGinley returns in standard-issue scenes that don't deserve a place in this film and the unit's story continues, telling what happens to the men. Most of the ending scenes are good, but following the nearly flawless sequences that precede them, it lowers the film's entire worth.

It could be argued that the ending scenes need to be there to avoid the feeling of unfinished business. That might be true, but the result drops what could be a truly great film to the realm of the merely good. Either way, Gordon creates a satisfying film experience which, flaws and all, succeeds at the uneasy task of being both hopeful and thoughtful.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Books, Fiction, Hawke

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, July 05, 2011

The longest tracking shot ever

By Edward Copeland

OK, technically, Slacker isn't one unbroken shot, but it almost feels that way, even 20 years after it finally completed its long, arduous journey toward a major U.S. release on this date (major for an indie arthouse film anyway). It only took writer-director Richard Linklater two months to film it in the summer of 1989, but the task of getting it released took two years. On the commentary track for the Criterion DVD that Linklater recorded in 2004, he says that he wanted the film to be "one long take" and re-watching it, Slacker still stuns me by how close it comes to evoking that feel, even though it's artifice. In many ways, it's an experimental film, so it's quite remarkable that its appeal became as broad as it did, that it remains so enjoyable on repeat viewings and that it even got made in the first place, especially for that fabled budget of $23,000.

Slacker covers 24 hours in Austin, though as Linklater points out in his commentary, it's actually only a small portion of the Texas city — confined mainly to the west side of the University of Texas campus and a few downtown clubs. The film contains no plot or narrative or central characters (In fact, characters don't get names as much as descriptions.); it just follows one person who then leads to another and another and so on, as if it's a funky sort of relay race with the baton constantly being passed. Miraculously, almost every character we meet and every short scene that plays out turns out to be as entertaining or fascinating as the one that came before. Slacker truly lacks any dead spots because we're watching all forms of humanity on display and though it's fiction, it almost plays like a documentary. "It seems spontaneous, but we always knew what was coming next," Linklater says on the DVD. The writer-director also is the first character to launch the chain, playing what he says is sort of a continuation of his first full-length feature It's Impossible to Learn to Plow By Reading Books, which is on the Criterion DVD and I'd planned to watch but simply ran out of time. Linklater plays Should Have Stayed at Bus Station who gets into a cab and tells Taxi Driver (Rudy Basquez) about a dream he had, which more or less sums up the idea behind Slacker itself.

"Do you ever have those dreams that are just completely real? I mean, they're so vivid it's just like completely real. It's like there's always something bizarre going on in those.…There's always someone getting run over or something really weird.…Anyway, so this dream I just had was just like that except instead of anything bizarre going on, there was nothing going on at all.…I was just traveling around…When I was at home, I was flipping through TV stations endlessly.Reading. I mean, how many dreams do you have where read in a dream?…it was like the premise for this whole book was that every thought you have creates its own reality, you know? It's like every choice or decision you make, the thing you choose not to do, fractions off and becomes its own reality, you know, and just goes on from there, forever. I mean, it's like you know in The Wizard of Oz where Dorothy meets the Scarecrow and they do that little dance at the crossroads and they think about going in all those directions and they end up going in that one direction? All those other directions, just because they thought about them, become separate realities. I mean, they just went on from there and lived the rest of their life…you know, entirely different movies, but we'll never see it because we're kind of trapped in this one reality restriction type of thing."

His full monologue runs much longer than that, but I had to cut it down a bit, but you don't know it the first time you see Slacker, but in hindsight and later viewings, he's giving you a lot of foreshadowing. For one thing, he mentions there is "always someone getting run over" and when he exits the cab to start the first handoff, that's the first thing he sees: a mother, Roadkill (Jean Caffeine) plowed down by a car we'll learn was driven by her Hit-and-Run Son (Mark James) as a couple of witnesses gather. Which one will we follow though? The movie of the Jogger (Jan Hockey) or the

businessman Running Late (Stephen Hockey)? Maybe the third person to appear on the scene, Grocery Grabber of Death's Bounty (Samuel Dietert). Nah. They all were just links waiting for the Hit-and-Run Son's car to reappear so we can see his story which, according to Linklater, may have been based on a true story which had become sort of a neighborhood legend, since the murdering son waited around for the police — reading no less. He also talks about flipping channels endlessly and we will eventually meet Video Backpacker (Kalman Spellitich) who has flooded his room with all types of TVs showing different images — he even has one strapped to his back. Should Have Stayed at Bus Station says the book with the different realities concept he described must have been written by him since it's in his dream and the part is played by Linklater after all, who described the structure of the film as "jumping from movie to movie" and said the content of the film was of less concern to him than the form. When I first saw Slacker, I laughed when Should Have Stayed at Bus Station made the comparison to The Wizard of Oz because ever since I was a kid and saw that movie for the first time, I always wondered what would happen if Dorothy and the gang decided to follow one of those brick roads of another color. They had to lead somewhere, didn't they?

businessman Running Late (Stephen Hockey)? Maybe the third person to appear on the scene, Grocery Grabber of Death's Bounty (Samuel Dietert). Nah. They all were just links waiting for the Hit-and-Run Son's car to reappear so we can see his story which, according to Linklater, may have been based on a true story which had become sort of a neighborhood legend, since the murdering son waited around for the police — reading no less. He also talks about flipping channels endlessly and we will eventually meet Video Backpacker (Kalman Spellitich) who has flooded his room with all types of TVs showing different images — he even has one strapped to his back. Should Have Stayed at Bus Station says the book with the different realities concept he described must have been written by him since it's in his dream and the part is played by Linklater after all, who described the structure of the film as "jumping from movie to movie" and said the content of the film was of less concern to him than the form. When I first saw Slacker, I laughed when Should Have Stayed at Bus Station made the comparison to The Wizard of Oz because ever since I was a kid and saw that movie for the first time, I always wondered what would happen if Dorothy and the gang decided to follow one of those brick roads of another color. They had to lead somewhere, didn't they?

While true that the structure formed the basis for the idea for Slacker, the budding filmmaker, who celebrated his 29th birthday during shooting (It's hard to believe Linklater is 51 now), also selected the premise of a plotless film where one character leads to the next as a matter of convenience. It eliminated the need for continuity concerns. A character once they appeared wouldn't be coming back later in the film, so hairstyle changes or other things weren't a worry. However, because Linklater wanted the movie to appear seamless, every decision on where to make a cut or edit became a "big deal." Since the film aimed to cover a 24-hour period but wasn't going to run 24 hours, at some point the movie had to switch from day to night and he did that with a dissolve that, at least in 2004 when he recorded the commentary, he still felt "was a cheat" 15 years after he'd done it. He employed 16mm, Super 8 and even a Fisher-Price toy "PixelVision" cameras to film the movie which were able to produce a viewable 16mm print but, Linklater admits, did present problems getting all actors in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio frame. Otherwise, Linklater had a relatively easy shoot, even laying down dolly tracks on public streets without permits and not getting in trouble for doing so.

Linklater did have some tryouts for roles in the movie, but many were played by friends, many who seemed to have been former or future roommates. His funniest recurring comment on the DVD is that everyone in the cast is a musician unless otherwise noted. That applied to the person in the movie's most infamous scene, Teresa Taylor, who portrays Pap Smear Pusher and also was the drummer for the band The Butthole Surfers, whose song "Strangers Die Everyday" plays over the end credits. What's forgotten in the memory of someone trying to sell Madonna's pap smear is that before she brings that up, she tells a pretty hilarious story about a man speeding down a highway squawking like a chicken and firing a gun in the air with one bullet ricocheting inside the car for awhile and another lodging in a girl's ponytail and the girl "called the pigs." An interesting note from Linklater's commentary track is that he wanted to avoid references that might date the movie too much and he pondered, since it was filmed in 1989 and Madonna had only been a star for about five years at that point, if her fame would last long enough that audiences well into the future would know who she was.

Because so many in the cast are playing characters that resemble themselves, you're not certain whether to praise someone's acting because you can't be sure that acting is taking place. However, there were some real or beginning actors in the cast, including a person who played a character that made quite an impression and that's Charles Gunning as Hitchhiker. Gunning had started acting not very long before Slacker: Joel and Ethan Coen discovered him and put him in Miller's Crossing. His scenes contain so much power that I believe he's the only character who doesn't just hand off to the next person he encounters: Linklater wisely lets him

linger a little longer. In fact, Linklater liked him so much that he used him again in his underrated film The Newton Boys and Waking Life. As Hitchhiker, Gunning's off-kilter deadpan delivery truly proves riotous, whether he's telling Nova (Scott Van Horn), the passenger in the convertible he's hitched a ride in, that he's coming from a funeral and Nova says he's sorry, "Fuck it — should have let him rot." As he explains further that the dead man was his stepfather who always got drunk and beat on his mom, him and his siblings. "He was a serious fuckup. I'm glad the son of a bitch is dead. Thought he'd never die.…I couldn't wait for the bastard to die. (pause) I'll probably go back next week and dance on his grave." Once he's left the car, even though he's already bummed a cigarette off the guys in the car, he asks a man at an outdoor cafe if he can have one, palms two and sticks the extra one behind his ear. He then gets stopped by the Video Interviewer (Tammy Ringler) who wants to see if he'll answer some questions, which he agrees to do. She asks if he voted in the last election. "Hell no — I've got less important things to do." She asks what he does to earn a living. "You mean work? To hell with the kind of work you have to do to earn a living. All that does is fill the bellies of the pigs that exploit us. Hey, look at me — I'm making it. I may live badly, but at least I don't have to work to do it." Just reading his lines doesn't do justice to Gunning's delivery. Sadly, Gunning died in December 2002 due to injuries from a car wreck. He was 51.

linger a little longer. In fact, Linklater liked him so much that he used him again in his underrated film The Newton Boys and Waking Life. As Hitchhiker, Gunning's off-kilter deadpan delivery truly proves riotous, whether he's telling Nova (Scott Van Horn), the passenger in the convertible he's hitched a ride in, that he's coming from a funeral and Nova says he's sorry, "Fuck it — should have let him rot." As he explains further that the dead man was his stepfather who always got drunk and beat on his mom, him and his siblings. "He was a serious fuckup. I'm glad the son of a bitch is dead. Thought he'd never die.…I couldn't wait for the bastard to die. (pause) I'll probably go back next week and dance on his grave." Once he's left the car, even though he's already bummed a cigarette off the guys in the car, he asks a man at an outdoor cafe if he can have one, palms two and sticks the extra one behind his ear. He then gets stopped by the Video Interviewer (Tammy Ringler) who wants to see if he'll answer some questions, which he agrees to do. She asks if he voted in the last election. "Hell no — I've got less important things to do." She asks what he does to earn a living. "You mean work? To hell with the kind of work you have to do to earn a living. All that does is fill the bellies of the pigs that exploit us. Hey, look at me — I'm making it. I may live badly, but at least I don't have to work to do it." Just reading his lines doesn't do justice to Gunning's delivery. Sadly, Gunning died in December 2002 due to injuries from a car wreck. He was 51.Members of the cast who aren't actors or musicians do pretty damn well too, though I suppose being a philosophy professor at UT as Louis Mackey was at the time when he played the Old Anarchist requires performing skills as well and Mackey shares them delightfully in another of my favorite scenes. The Old Anarchist and his daughter Delia (Kathy McCarty) enter the movie as they witness the apprehension of the Shoplifter (Shelly Kristaponis) outside a grocery store. Delia tells her father that Shoplifter was in her ethics class and he comments, "Well, I'm always glad to see any young person doing SOMETHING" only he's referring to the shoplifting, not the ethics class. When they arrive home, they happen upon Burglar (Michael Laird), a

particularly inept criminal who fumbles with his gun and didn't get a chance to try to steal anything because he was reading one of the many books in the house. The Old Anarchist easily takes the gun from Burglar and befriends him immediately, telling him, "No one's going to call the police. I hate the police more than you probably. Never done me any good." Just the idea of some aging, white-haired anarchist who says the things he does was pretty damn daring for a filmmaker trying to get his career off the ground and forming his first major work around a specific city. Old Anarchist would praise Leon Czolgosz as an American hero and lament not being on campus the day Charles Whitman went up into the tower with a sniper's rifle "because my fucking wife — God rest her soul — she had some stupid appointment that day. So during this town's finest hour, where the hell was I? Way the hell out on South Congress." You would think there would still be enough survivors or relatives of Whitman's victims in Austin that the film would have been reviled there, but it was embraced. Linklater says on the DVD that he "really thought Slacker had something in it to alienate everybody on some level or another." In referring to the Whitman lines, he even referenced what I thought of when I saw it — Alan Alda's character's formula in Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors : "Comedy equals tragedy plus time." Mackey though plays the nutty old kook wonderfully as he tries to impart life lessons on the would-be thief. "It's taken my entire life, but I can now say that I've practically given up on not only my own people but for mankind in its entirety. I can only address myself to singular human beings now."

particularly inept criminal who fumbles with his gun and didn't get a chance to try to steal anything because he was reading one of the many books in the house. The Old Anarchist easily takes the gun from Burglar and befriends him immediately, telling him, "No one's going to call the police. I hate the police more than you probably. Never done me any good." Just the idea of some aging, white-haired anarchist who says the things he does was pretty damn daring for a filmmaker trying to get his career off the ground and forming his first major work around a specific city. Old Anarchist would praise Leon Czolgosz as an American hero and lament not being on campus the day Charles Whitman went up into the tower with a sniper's rifle "because my fucking wife — God rest her soul — she had some stupid appointment that day. So during this town's finest hour, where the hell was I? Way the hell out on South Congress." You would think there would still be enough survivors or relatives of Whitman's victims in Austin that the film would have been reviled there, but it was embraced. Linklater says on the DVD that he "really thought Slacker had something in it to alienate everybody on some level or another." In referring to the Whitman lines, he even referenced what I thought of when I saw it — Alan Alda's character's formula in Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors : "Comedy equals tragedy plus time." Mackey though plays the nutty old kook wonderfully as he tries to impart life lessons on the would-be thief. "It's taken my entire life, but I can now say that I've practically given up on not only my own people but for mankind in its entirety. I can only address myself to singular human beings now."As far as I can remember, Slacker never played in my city in 1991 as was often the case with many arthouse films back then. So, as would often happen, I would either drive to Dallas by myself or with friends to catch those types of movies, usually at the Inwood on Lovers Lane. That's where I saw Slacker. Austin may have been able to get past the Charles Whitman part, but I wasn't there to know if they laughed. I do know

however that Dallas moviegoers still carry sensitivity relating to JFK's assassination. The whole scene, involving the character called JFK Buff (John Slate) is pretty funny. Linklater even calls it one of, if not his favorite scene in the film. However, when JFK Buff appeared on screen wearing a T-shirt with a big picture of Ruby shooting Oswald, my visiting friends and I all laughed out loud. I don't think our laughter was particularly noisy — it just stood out from the others in the audience who were from Dallas and in complete silence. I even caught one or two people look our direction. If I weren't a strict proponent of not talking during movies, I might have said, "Relax. Neither you nor your city killed him and that was almost 30 years ago (at that time)." As you would expect, JFK Buff was an authority on all things Kennedy, conspiracy and otherwise and he's advising a young woman called Girlfriend (she's not his, but played by Sarah Harmon) who is browsing through the Kennedy section of a bookstore which are the best books to read. He's also writing his own JFK book which he wanted to call Profiles in Cowardice, but his publisher suggested issuing as Conspiracy-a-Go-Go. He suggests she "snap up" the book Forgive My Grief which has the story of how Oswald and Officer Tippet were supposed to have their "'breakfast of infamy.' Yeah, the waitresses went on the record, in the Warren Report, as saying Oswald didn't like his eggs and used bad language," JFK Buff tells her. Ironically, as recently as 2006, John Slate worked as the city archivist for Dallas so he actually works with Kennedy assassination documents.

however that Dallas moviegoers still carry sensitivity relating to JFK's assassination. The whole scene, involving the character called JFK Buff (John Slate) is pretty funny. Linklater even calls it one of, if not his favorite scene in the film. However, when JFK Buff appeared on screen wearing a T-shirt with a big picture of Ruby shooting Oswald, my visiting friends and I all laughed out loud. I don't think our laughter was particularly noisy — it just stood out from the others in the audience who were from Dallas and in complete silence. I even caught one or two people look our direction. If I weren't a strict proponent of not talking during movies, I might have said, "Relax. Neither you nor your city killed him and that was almost 30 years ago (at that time)." As you would expect, JFK Buff was an authority on all things Kennedy, conspiracy and otherwise and he's advising a young woman called Girlfriend (she's not his, but played by Sarah Harmon) who is browsing through the Kennedy section of a bookstore which are the best books to read. He's also writing his own JFK book which he wanted to call Profiles in Cowardice, but his publisher suggested issuing as Conspiracy-a-Go-Go. He suggests she "snap up" the book Forgive My Grief which has the story of how Oswald and Officer Tippet were supposed to have their "'breakfast of infamy.' Yeah, the waitresses went on the record, in the Warren Report, as saying Oswald didn't like his eggs and used bad language," JFK Buff tells her. Ironically, as recently as 2006, John Slate worked as the city archivist for Dallas so he actually works with Kennedy assassination documents. When you have a 100 minute film that's stuffed full of so many unique and interesting characters and memorable moments, you can't possibly highlight them all, no matter how much you might want to pay tribute to them on this anniversary. There's the Dostoyevsky Wannabe (Brecht Andersch) "Who's ever written the great work about the immense effort required NOT to create?"; I'd really love to write at length about the

scene with Been on Moon (Jerry Deloney) "So they must like children too, because FBI statistics since 1980 say that 350,000 children are just missing — they disappeared. There's not that many perverts around."; Bush Basher (Daniel Dugan) and his ideas on how the nonvoting majority wins ever election; Prodder (Steve Anderson) who makes Jilted Boyfriend (Kevin Whitley) perform ritual sacrifice of items related to his ex-girlfriend with Boyfriend (Robert Pierson) along to watch; Scooby-Doo Philosopher (R. Malice) explaining how the cartoon teaches kids about bribery and how he thinks Smurfs has something to do with Krishna so people will be used to seeing blue people; Having a Breakthrough Day (D. Montgomery) handing out her oblique strategy cards and I could keep going, but I'll stop with Old Man (Joseph Jones), who appears toward the end walking down a road talking into a tape recorder and saying, "When young, we mourn for one woman. As we grow old, for women in general."

scene with Been on Moon (Jerry Deloney) "So they must like children too, because FBI statistics since 1980 say that 350,000 children are just missing — they disappeared. There's not that many perverts around."; Bush Basher (Daniel Dugan) and his ideas on how the nonvoting majority wins ever election; Prodder (Steve Anderson) who makes Jilted Boyfriend (Kevin Whitley) perform ritual sacrifice of items related to his ex-girlfriend with Boyfriend (Robert Pierson) along to watch; Scooby-Doo Philosopher (R. Malice) explaining how the cartoon teaches kids about bribery and how he thinks Smurfs has something to do with Krishna so people will be used to seeing blue people; Having a Breakthrough Day (D. Montgomery) handing out her oblique strategy cards and I could keep going, but I'll stop with Old Man (Joseph Jones), who appears toward the end walking down a road talking into a tape recorder and saying, "When young, we mourn for one woman. As we grow old, for women in general."When it comes to picking the best part of Slacker, selecting that choice doesn't require any mulling or contemplation because Richard Linklater himself serves as the film's strongest and longest-lasting legacy. Slacker belongs in that same category of film as Citizen Kane (I'm not saying in terms of greatness) where its structure guarantees its freshness because it's so unique no matter how many times you see it, you're never certain what comes next. Not all of Linklater's films have turned out to be gems, but then that's the case with most great filmmakers. Robert Altman and Billy Wilder had their duds too. In fact, with the exception of School of Rock (which I love) and The Bad News Bears remake (which I still refuse to see), he reminds me of Altman in the way he avoids commercial prospects when picking projects. He's also been very prolific, to the point that I think some of his movies escaped people's notice altogether.

Look at the body of work he's compiled since Slacker: the great Dazed and Confused; the exquisite yet complete change-of-pace that was Before Sunrise, which I got to interview him about on the phone; the very good adaptation of Eric Bogosian's off-Broadway play SubUrbia; The Newton Boys, long overdue for reappraisal; Waking Life, which admittedly works better as an experiment in style than as a film; the underseen and very strong Tape featuring searing work by Robert Sean Leonard, Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke; the aforementioned blast that is The School of Rock; Before Sunset, the unlikeliest sequel ever made; turning a nonfiction best seller into a fiction film with the same message in Fast Food Nation; A Scanner Darkly, his venture into Philip K. Dick and sci-fi using the animation technique from Waking Life; Inning by Inning: A Portrait of a Coach, a documentary about Texas' baseball coach who holds the most wins in NCAA history, a film I didn't even know about until I was going through IMDb; and his most recent film, Me and Orson Welles, which is simply one of the best he's made. Later this year, there should be a new Linklater crime comedy called Bernie that reunites him with Jack Black and Matthew McConaughey and also starring Shirley MacLaine.

Back to Slacker, the film I'm saluting. On that commentary, Linklater says that much of the movie really revolves around deciding whether or not to do something or, as he put it, "To act or not to act." If that is the question Slacker poses, Linklater chose the positive response and film lovers are better off for him doing so.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Alda, Altman, Coens, Hawke, Linklater, MacLaine, Movie Tributes, Remakes, Sequels, Welles, Wilder, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, April 09, 2011

Sidney Lumet (1924-2011)

I want you to get up right now. I want you to stand up, out of your chairs. I want you to get up, go to your window, open it and shout, "I'm as sad as hell. Sidney Lumet has died." One of the all-time great film directors, whose debut in 1957, 12 Angry Men, earned him his first Oscar nomination, and who 50 years later still was capable of producing as great a film as Before the Devil Knows You're Dead died today in New York at 86.

Lumet actually began his career as a child actor, making his first appearance on the Broadway stage in 1935 in the original production of Dead End. He'd act on Broadway multiple times until 1948 when directing for

television caught his eye. He only directed on Broadway three times. His direction for television began in 1951 and included both episodic television and the many live playhouse shows until the chance to direct 12 Angry Men as a feature came along in 1957. Its origins as a play clearly showed, but there was no point trying to open this tale up since the claustrophobia of that jury room heightened the drama and Lumet used to his advantage, as in the moment when they discuss the unusual knife the defendant had and that the victim was killed with and Henry Fonda suddenly whips out one of his own, tossing it so the blade sticks in the middle of the table. The film contained a great cast including, in addition to Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, E.G. Marshall and Jack Warden. In fact, of the 12 members of that jury, only Jack Klugman remains with us today.

television caught his eye. He only directed on Broadway three times. His direction for television began in 1951 and included both episodic television and the many live playhouse shows until the chance to direct 12 Angry Men as a feature came along in 1957. Its origins as a play clearly showed, but there was no point trying to open this tale up since the claustrophobia of that jury room heightened the drama and Lumet used to his advantage, as in the moment when they discuss the unusual knife the defendant had and that the victim was killed with and Henry Fonda suddenly whips out one of his own, tossing it so the blade sticks in the middle of the table. The film contained a great cast including, in addition to Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, E.G. Marshall and Jack Warden. In fact, of the 12 members of that jury, only Jack Klugman remains with us today.Lumet continued his television work, not directing another feature until 1959's That Kind of Woman starring Sophia Loren. The following year, he got more notice when Tennessee Williams adapted his own play Orpheus Descending into The Fugitive Kind which Lumet filmed with Marlon Brando and Anna Magnani. In 1962, Lumet made a film of another stage classic, Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night, starring Katharine Hepburn as the opium-addicted Mary Tyrone.

In 1964, he filmed two of his most underrated movies: The Pawnbroker, featuring a great performance by Rod Steiger as the Jewish title character, a Holocaust survivor, who has given up on mankind; and Fail-Safe, a tense nuclear thriller starring Henry Fonda that got overshadowed by the satire of Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove which came out first the same year.

He kept quite busy for the rest of the 1960s and early '70s, directing The Hill, The Group, Bye Bye Braverman, The Sea Gull, The Appointment, Last of the Mobile Hot Shots, The Anderson Tapes, The Offence and Child's Play. In 1971, Lumet and Joseph L. Mankiewicz co-directed the documentary King: A Filmed Record...Montgomery to Memphis about Martin Luther King Jr.

Beginning in 1973, Lumet started what was the most creatively fertile and rewarding period of his filmmaking career, one that earned him four consecutive nominations from the Directors Guild. Starting with Al Pacino in Serpico, it was one of many times in Lumet's career he'd turn his lens on the issue of corruption among police. In 1974, he went in another direction, casting Albert Finney as Agatha Christie's famed Belgian sleuth Hercule Poirot and assembled an amazing cast for Murder on the Orient Express.

Then came the first of an amazing one-two punch with 1975's Dog Day Afternoon, one of Lumet's greatest achievements and a film I never tire of watching. With Al Pacino and John Cazale attempting to rob a bank and having it turn into a hostage situation and a media sideshow, it's a wonder. It brought Lumet his first Oscar nomination for directing since that initial one for 12 Angry Men. It's not only proof of what a great director Lumet could be but when they released the special two-disc DVD edition of the film, Lumet also showed that he's one of the few people who actually recorded DVD commentaries that were worth listening to, sharing many interesting details about the production of this great work which deftly blends the humorous, the tragic and the absurd.

He followed Dog Day up in 1976 with the incomparable Network. While much of the credit for this satirical and prescient masterpiece deservedly goes to Paddy Chayefsky's Oscar-winning script, Lumet's direction

shouldn't get short shrift. The way he filmed the chaos of the network control rooms and its overlapping dialogue and always found the right pacing for whatever craziness was going on. Also, as in Dog Day, Lumet didn't have a musical score. Except for the opening song in the 1975 film and the network news theme in Network, he eschewed any musical underscore. Neither film needed one. He also assembled some great visual compositions, such as the long view down the canyons of New York with windows open as far as the eyes could see with heads sticking out screaming "I'm mad as hell" to Ned Beatty and the lighting as he's at the end of that long conference table about to give Peter Finch his corporate cosmology speech. Brilliant. Lumet received his third directing nomination.

shouldn't get short shrift. The way he filmed the chaos of the network control rooms and its overlapping dialogue and always found the right pacing for whatever craziness was going on. Also, as in Dog Day, Lumet didn't have a musical score. Except for the opening song in the 1975 film and the network news theme in Network, he eschewed any musical underscore. Neither film needed one. He also assembled some great visual compositions, such as the long view down the canyons of New York with windows open as far as the eyes could see with heads sticking out screaming "I'm mad as hell" to Ned Beatty and the lighting as he's at the end of that long conference table about to give Peter Finch his corporate cosmology speech. Brilliant. Lumet received his third directing nomination.Things got a little bumpy filmwise after that. Next came the adaptation of the play Equus followed by what many count as his biggest mistake: casting a too old Diana Ross as Dorothy in the big screen version of the Broadway musical The Wiz, which also featured Michael Jackson as the Scarecrow. Next came a rather lame Alan King-Ali McGraw romantic comedy (Yes, you read that correctly) called Just Tell Me What You Want.

Lumet began to get his bearings again by going back to police corruption with 1981's Prince of the City, which earned him his first Oscar nomination in a writing category. The next year brought him his final nomination as a director for The Verdict, starring Paul Newman as an alcoholic lawyer seeking redemption. That same year, he made the fun adaptation of the play Deathtrap starring Michael Caine and Christopher Reeve.

The remainder of his career mixed some OK efforts with some really bad ones. He made Running on Empty, which earned River Phoenix an Oscar nominaton but did his best when going back to corruption in movies such as 1990's Q&A and 1996's Night Falls on Manhattan. In 2005, the Academy finally saw fit to award him an honorary Oscar, back when they still televised those events. At least he ended on a high note, with the really good 2007 film Before the Devil Knows You're Dead starring Philip Seymour Hoffman, Ethan Hawke and Albert Finney.

RIP Mr. Lumet.

Tweet

Labels: Brando, Caine, Chayefsky, E.G. Marshall, H. Fonda, Hawke, Jack Warden, K. Hepburn, Kubrick, Lee J. Cobb, Magnani, Mankiewicz, N. Beatty, Newman, O'Neill, Obituary, P.S. Hoffman, Pacino, River Phoenix, Tennessee Williams

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, June 19, 2010

From the Vault: Before Sunrise

In an interview last month, director Robert Altman said it's always better seeing a movie a second time. Knowing what's going to happen, he proposed, relaxes filmgoers so they can concentrate on details.

Unfortunately, constraints more often than not prevent a critic from having a second viewing before the review is due. Thankfully, this was not the case with Before Sunrise, writer-director Richard Linklater's latest film, which offers great support for Altman's statement.

Linklater, with his naturalistic style and the ensemble casts of his first two films, Slacker and Dazed and Confused, could be superficially compared to Altman, but the most important trait they share is the rarest of things in movies today - the willingness to cross the cinematic tightrope without a net.

This is what Linklater has done with Before Sunrise, a distinct departure from the free-wheeling fun of his first two efforts. While it's hardly a complete success, it does provide ample rewards for the discerning viewer and further secures the 33-year-old Linklater's place as one of the major talents of the new generation of filmmakers.

Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy star in Before Sunrise and, unlike the vast casts of Linklater's previous work, they are the only characters the viewer has to focus on, playing twentysomethings from the United States and France, who meet each other aboard an Austrian train and decide to spend Hawke's remaining hours in Europe strolling around Vienna.

Linklater co-wrote the film with Kim Krizan and together they take An Affair to Remember, drop the hokey melodrama and crossbreed it with My Dinner With Andre. On one level, it's a brief romance between strangers, but deeper down Before Sunrise tackles the love of conversations and ideas.

Given its talky nature, audiences with short attention spans will likely grow fidgety waiting for a plot engine that doesn't arrive.

Though I admired Before Sunrise the first time, I didn't freely enjoy it until that second viewing.

The first time, Hawke seemed too frantic in the early stages of the movie, coming off like a grunge Woody Allen. In retrospect though, his exuberance stems purely from his character's desire to captivate Delpy and not from a conceit.

Delpy, on the other hand, is charming from the very first, and the fact that she is as much a newcomer to Vienna as Hawke adds to the accurate depiction of visitors to foreign countries.

Aside from a slow start, the only real problem is the abrupt ending. It leaves you wanting more and even a tentative resolution would be more satisfying.

However, that's a quibble, because Linklater is sticking his artistic neck out so far, you want to couch criticism of it in the softest terms so as not to discourage him from striking out in daring directions.

Since Linklater is so talented, that probably shouldn't be a concern. Before Sunrise will not please everyone, but only the grumpiest of moviegoers should fail to be seduced by its charm.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Altman, Hawke, Linklater, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

From the Vault: Richard Linklater

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED JAN. 27, 1995

Few things can stir as much excitement as finding a promising young artist and watching him grow. Austin, Texas-based writer-director Richard Linklater, 33, currently promoting his third theatrical release, has shown much willingness to grow. His latest movie, Before Sunrise, demonstrates he is never content to play it safe.

Before Sunrise stars Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy. The film shows a brief romance between a young American man and a young French woman who meet on an Austrian train and decide to spend several hours walking the streets of Vienna together.

The pared-down cast is quite a switch for Linklater, whose two previous efforts were two different types of ensembles: a collage of characters in Slacker and many students populating Dazed and Confused.

"The making of (Before Sunrise) was very intimate. I worked very closely, very intensely with two people, but I was up for that. I was looking forward to that. I felt I needed to do that next."

Linklater was speaking by telephone from Austin last week where Before Sunrise premiered one day prior to kicking off the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

Before Sunrise was made in 25 days for $3 million, a low budget for most film releases but a staggering increase considering Slacker cost a mere $23,000. Sunrise cost about half what Dazed and Confused cost to make.

"It's really not the budget, but how much each film needs to be made the right way. I felt I got everything I wanted."

Part of what he wanted became the city of Vienna itself, where the movie was made, though Linklater returned to his home base of Austin for post-production work.

"The Austrian government was very accommodating. They were open to us filming there, unlike a lot of cities. I liked the city. I wouldn't have used it otherwise. I just thought it was an interesting, kind of classical backdrop. It could have been other cities, but once it was Vienna I really wanted to make ... a movie that couldn't have been anywhere else."

The romance in Before Sunrise achieves a kind of universal appeal, even if the exact details of the film haven't happened to each individual viewer.

"I think everyone's had an experience like this, in some way or another."

In some respects, Linklater has been surprised by how well received his somewhat idiosyncratic movies have been.

"When I first set out to make films, I didn't know if they would be funny or if people would relate to them. You never really know. I guess it was surprising to see my sensibilities hooked up with more people than I thought they would have. We all imagine ourselves way off in the corner, doing something really weird, but I have to admit that there's something kind of common about me. I kind of tap into a common experience."

Unlike many talented filmmakers of Linklater's generation or the two generations that preceded them, Linklater wasn't weaned on movies in childhood. His interest came rather late.

"It wasn't until later that I got interested in films. I guess the most fascinating film of my childhood was ... watching 2001. I think I was in first grade. I thought, 'My God.' It really intrigued me, and it still does. It's really amazing, the power of the medium to appeal to a 7-year-old or an older person, same film. I think films communicate on a deeper level that way. It was in college I really started watching films more seriously, or thinking of them as an art form. I was just coming in contact with great films, not just the entertainments that opened that week, but the classics."

Ideally, Linklater would like to make a film a year, though he admits that can be tough to do. Once the promotion cycle for Before Sunrise winds down, he hopes to get back to work on his next script, a more epic-type film involving Texas history set in the 1920s.

"It'll be yet another big change, but I think it will still be very character driven."

He hopes to film in summer or fall of this year with a possible 1996 release. For the foreseeable future, Linklater plans to stick to scripts that he's been involved in writing. Filming someone else's screenplay is "quite a ways down the road, I think. I have a lot of stories of my own I really want to do. Whatever feels right next, you know, that sort of thing."

Tweet

Labels: Hawke, Interview, Linklater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, November 09, 2007

The Devil's Reject

Quentin Tarantino can teach Sidney Lumet a thing or two about directing. And yes, my subject and object are in the proper places in that sentence. For better and worse, the short, meteoric rise of QT ushered in the still-active era of movies being told out of sequence, or in multiple and parallel flashbacks, for no reason whatsoever. Tarantino usually is able to pull it off because his direction embraces the fractured narrative, builds upon it and uses it to his full advantage. It's as if the film knows the flashbacks are coming or its sequence is out of order, and it adjusts accordingly without breaking its hold on the viewer. It doesn't announce FLASHBACK in giant capital letters. That's the lesson Sidney Lumet could learn from QT, because in Before The Devil Knows You're Dead, whenever the amateurish screenplay decides to go backward, Lumet announces it with incredibly annoying Pokemon-style screen flashing. It tosses the viewer right out of the movie.

Sondheim wrote "you gotta have a gimmick" and while that always works for strippers, it doesn't always work for film. Lumet builds tension so carefully in some scenes that the sudden announcement of flashbacks let all the air out of the balloon. Compare this to his devastating use of flashbacks in The Pawnbroker. There is absolutely no reason for the story to be told in this fashion, outside of sheer laziness and the screenwriter's knowledge that his script, if told straight, would have been no different than 8,000 other scripts with this same story. Yet Lumet's direction is so good at times that I felt he could have made this work without the gimmicks. The screenplay would still be just as derivative and unbelievable, but we would have been too busy being strangled by suspense to notice. This film just doesn't build the way it should have. It stops and starts like a traffic light-ridden NASCAR race. The herky-jerky back and forth gives far too much time to contemplate the numerous questions that derail the film's hold on the viewer.

In the screenplay chapter of his must-read book, Making Movies, Lumet writes:

"In a well made drama, I want to feel: 'Of course — that's where it was heading all along.' And yet the inevitability mustn't eliminate surprise. There's not much point in spending two hours on something that became clear in the first five minutes. Inevitability doesn't mean predictability. The script must still keep you off balance, keep you surprised, entertained, involved, and yet, when the denouement is reached, still give you the sense that the story had to turn out that way."

This is a very telling paragraph from Lumet. Is this film's construction a blatant attempt to stave off predictability without losing inevitability? And is this the reason why so many movies have flirted with the "off-balance" device of the non-linear gimmick? I really don't see much difference: if it's inevitable, then you can predict it's going to happen. This isn't as bad an idea as slowing down and hacking up your movie until the viewer can meditate on how illogical the story is.

Andy (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is the financially strapped eldest son of Charles (Albert Finney) and Nanette (Rosemary Harris). Between his drug addiction and his golddigger trophy wife, Gina (Marisa Tomei), Andy's wallet is screaming for help. To silence the noise, Andy has also been stealing money from payroll. Andy's younger brother Hank (Ethan Hawke) has money problems of his own: he can't pay his child support and his angry ex-wife Martha (Amy Ryan) is threatening him with court action. When he can't pay for his daughter's trip to The Lion King, he allows himself to be taken in by Andy's plan to help them both achieve hakuna matata. They decide to rob their Mom and Pop's Mom and Pop Jewelry Store — or rather, Andy decides Hank should do it — so that they can get quick cash and their parents can collect the insurance money that will result from the robbery. "It's a victimless crime," Andy says, using that bullying, manipulative manner we older brothers employ so well.

Of course, the robbery goes awry, and the primary reason for this is that Andy is, to use the film's love of the f-word, a fucking idiot. Hank's an idiot as well, but Andy knows not only this fact but also how wimpy Hank is in general. He assigns Hank the job, telling him to use a fake gun, and Hank instead gets a more hardened criminal (Brian F. O'Byrne from Frozen) to pull the job. Suffice it to say, the crime's not victimless, and O'Byrne winds up as dead as the victim he shoots in the heist.

As the brothers' world comes tumbling down, they make one inevitable mistake after another. They have to deal with Hank's ineptitude and Andy's horse addiction, their father's compulsive desire to find out who robbed his store and caused the carnage, the secrets that threaten to tear their fraternal love apart, and the women who drive them to do and say the darndest things. It sounds compelling, but the film's construction is far too distracting to be effective. And the questions that arise just nag at the viewer in the dark. Are these guys really in that much trouble that they need to resort to a jewelry heist? Why not Andy instead of wishy-washy Hank? How did Andy suddenly morph from Pillsbury Yuppie to Chuck Bronson? Why would Hank rent a car, effectively creating a paper trail, to do a robbery? If you have that much dope and dough in your house, wouldn't you have something besides a punk-ass revolver? Wouldn't an autopsy show that you smothered someone to death? Why steal from your job's payroll box when you know you're being audited? Why didn't the job call the cops on Andy? I could go on and on.

A film such as Before the Devil Knows You're Dead needs the kind of suspension of disbelief continuity of a film like To Catch a Thief or the film I wish this movie could have been: Sam Raimi's A Simple Plan. On occasion, Lumet reaches for the greatness he is known for, which makes the film's overall failure even more frustrating. Watch how he visually constructs an outdoor scene between Hoffman and Finney. Just the placement of the characters alone speaks volumes, making the stilted dialogue that pollutes the scene completely unnecessary. Observe how he visually plays out the scenes that depict Hank's criminal seduction by Andy. The robbery itself has incredible tension and an almost existential visual quality; it's as mean and lean as the rest of the film thinks it is.

Lumet's biggest failures usually stem from a lousy script or miscast performers (I'm looking at you, Miss Ross, in The Wiz). Before the Devil Knows You're Dead has both. Until his last reel gunplay, which does not work at all, Hoffman is a credibly smarmy creature with daddy issues and a wife he (correctly) thinks is out of his league. Ethan Hawke is so woefully miscast that it's painful to watch him. Albert Finney is wasted, but Rosemary Harris is interesting and far more credible with a gun than her cinematic son. Michael Shannon leaves an impressive mark on his limited screen time, as does Amy Ryan, and O'Byrne brings an expert's menace to his sacrificial role that can be used as a measuring stick for the brothers' amateur night at the criminal Apollo.

Marisa Tomei's character is one note and should have been accompanied by Whodini's "I'm a Ho" every time she appeared on the screen. Her sole purpose in the film is to show the naked body far too many critics are panting over, as if they've never seen tits and ass before. These are the same critics who have the nerve to be offended by the sex scene between her and Hoffman that opens the film, as if his far-from perfect (yet oddly film critic-like) body ruins their Tomei spank-bank entry and offends their sensibilities. I saw it as a harbringer of the film's dysfunction: it's superbly shot and visually arresting, but the content of the scene itself is not worth watching. Interestingly enough, it's the one stand alone scene in the picture (i.e., we don't know where it fits in with the rest of the timeline, short of assuming it comes before the film's story). It also tells us everything we need to know about the characters without saying a word.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Amy Ryan, Finney, Hawke, Lumet, Michael Shannon, P.S. Hoffman, Raimi, Sondheim, Tarantino, Tomei

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, April 16, 2007

At 8½ hours, this playwright ain't Russian

The questions prompted by Tom Stoppard’s The Coast of Utopia, the ambitious three-play cycle being performed in repertory at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater, extend beyond those of the philosophical

bent being posed by the characters onstage. This is especially true for anyone attempting to write about it — exactly how does one go about summarizing an 8½ hour work of theater, so broad in scope of purpose and meaning as to all but defy any attempt at description?

bent being posed by the characters onstage. This is especially true for anyone attempting to write about it — exactly how does one go about summarizing an 8½ hour work of theater, so broad in scope of purpose and meaning as to all but defy any attempt at description?

For the obdurate critic, it’s a daunting proposition. If one had the time and the inclination, the assignment might entail drawing up an outline, mapping out the overall narrative arc and the journeys of the major characters in minute detail, then endeavoring to explain how it all relates to the playwright’s observations about the nature of revolution in all its permutations, both literal and figurative. Shew.

If I sound overawed by the prospect, I think many would concur that The Coast of Utopia is a work to inspire awe — and trepidation. Well in anticipation of its Broadway premiere, the intimidation factor surrounding Stoppard’s epic treatment of the lives and loves of revolutionary thinkers in 19th-century Russia was giving advance ticketholders night sweats. The panic reached its apotheosis when The New York Times (much to the chagrin of the people involved with the production) ran a list of publications prospective theatergoers ought to read before attempting to see the show — presumably to preserve any hope of understanding it. This recommended reading list, with citations ranging from the novels of Pushkin and Turgenev to long out-of-print collections of obscurely authored letters, conveyed the impression that a trip to the Beaumont represented less a night at the theater than a sort of winnowing-out process, the intellectual equivalent of Survivor. For those who were smart or well-studied enough to hang tough, the rewards would be manifold. For those who didn’t do their homework, the titles of the three installments, when recited in order — “Voyage,” “Shipwreck” and “Salvage” — had a ring of grim prophecy.

Of course, if the trilogy had been the work of say, Neil Simon, the appearance of a suggested reading list in the Times might not have produced nearly as much anxiety. Fairly or not, the name of Stoppard has always inspired an automatic sense of dread in certain quarters. Never the most user-friendly of playwrights to begin with, the term “genius” has often been used in reference to both the writer and his work — and not always in the spirit of a compliment. His critics accuse him of talking over the heads of his audiences; I, for one, will freely admit to never having been able to make heads or tails of Jumpers, one of his more inscrutable exercises in cerebral esoterica. Those who accuse his work of being emotionally inaccessible are given to say that he writes with his head, as opposed to his heart. To some extent (even though I don’t necessarily agree with that assessment), the reputation has been earned. Even with his best works — and the recent Broadway productions of The Invention of Love and The Real Thing stand as two of the highlights of my life’s theatergoing experience — there are moments when dramatic concision gets lost in a tangle of knotty verbiage, while considerations of character and plot take a back seat to the myriad of ideas floating in the ether.

The Coast of Utopia is not immune to some of these flaws, but it is not, as it detractors have suggested, dry, dull and dramatically inert. It’s talky, to be sure — often, too much so — but behind the intellectual discourse is something real and raw, a wellspring of human emotions both beautiful and terrible. When they bubble to the surface, the result is as arresting as anything to be seen on the stage in this or any season. A panoramic view of the tumult of European history, politics and thought, Stoppard’s most ambitious work to date is as miraculous as it is maddening — but it can never be accused of lacking in passion.

Just for the record, neither is it impossible to understand. As someone who did none of the required reading on the Times syllabus, I experienced no difficulty in following the action, although I made a deliberate decision early on not to try to assimilate every piece of revolutionary theory (featuring the ruminations of Marx, Kant, Hegel and a host of others) being trotted out on display. Be grateful for the fact that these revolutionaries led such colorful lives — beneath all the high-minded talk are the workings of a juicy, multigenerational soap opera.

Rather than tackling this three-headed hydra head-on, for the purposes of this writing it’s better to distill the plot down to the barest of essentials; a prolonged discussion of

the various subplots, which are legion, would only breed confusion for the reader (and even more so for the writer.) The play charts the changing fortunes of an extended circle of 19th-century Russian revolutionaries — writers, philosophers, activists and agitators — over a span of 30 years. Their personal lives follow the same chaotic path as the politics of the Russian state, with optimism giving way to disillusionment as the idealism of youth is thwarted and confused by the capricious currents of history. The tragedy of these visionaries lies in the fact that, in spite of their best intentions, their vision got away from them — so much so as to leave them bewildered. A quixotic dream of Utopian Socialism is distorted by the tumult of constant upheaval and radical revisionism to the point that it eventually mutates into a harsher strain of Bolshevism (and ultimately, Communism.) These dreamers reach the coast of utopia, but never quite set foot on land.

the various subplots, which are legion, would only breed confusion for the reader (and even more so for the writer.) The play charts the changing fortunes of an extended circle of 19th-century Russian revolutionaries — writers, philosophers, activists and agitators — over a span of 30 years. Their personal lives follow the same chaotic path as the politics of the Russian state, with optimism giving way to disillusionment as the idealism of youth is thwarted and confused by the capricious currents of history. The tragedy of these visionaries lies in the fact that, in spite of their best intentions, their vision got away from them — so much so as to leave them bewildered. A quixotic dream of Utopian Socialism is distorted by the tumult of constant upheaval and radical revisionism to the point that it eventually mutates into a harsher strain of Bolshevism (and ultimately, Communism.) These dreamers reach the coast of utopia, but never quite set foot on land.

The action moves from a bucolic county estate in the Russian countryside to the pressure-cooker of Moscow across the politically unstable landscape of 19th-century Europe, featuring an ever-rotating merry-go-round of more than 40 major and minor characters. Anchoring the trilogy is the writer Alexander Herzen (Brian F. O’Byrne), credited as being the father of Western socialism. Exiled from his homeland, he relocates to France and later Italy with his young family, continuing his advocacy for political reform. After the death of his wife, Natalie (Jennifer Ehle), he eventually establishes a Free Russian press based out of London, and ends his life in Switzerland, if not forgotten then widely discounted by the new breed of revolutionaries who rise up in his generation’s place. If O’Byrne, who has become one of Broadway’s most prolific leading men, came across as rather stiff and oratorical in the trilogy’s middle passage (he remains on the periphery of the action in the first play), by the time I saw him in “Shipwreck” several weeks later, he seemed to have relaxed nicely into the role.

Orbiting around Herzen is a galaxy of satellites — a motley collection of aristocrats, free-thinkers, lovers and rabble-rousers — and one would be hard-pressed to recall a starrier ensemble of actors than the one currently assembled at the Beaumont. It’s impossible to single out all of the 40-odd players who comprise this gallery of historical figures, although it should be mentioned that a number of them perform double or triple duty in multiple roles. Ethan Hawke hits the right notes of arrogance and petulance in a spry, funny turn as Michael Bakunin, the spoiled scion of privileged landed gentry who pursues his revolutionary interests with the brash moral certitude of an ego unchecked. Billy Crudup is virtually unrecognizable in his finely-tuned portrayal of the nebbishy journalist and critic Vissarion Belinsky, while Josh Hamilton finds subtle shades of regret and resignation in the poet and historian Nicolas Ogarev. Richard Easton is outstanding as the Bakunin patriarch,

his self-satisfied complacency being slowly eroded by the harsh winds of change, and supplies moments of unbearable poignancy later on in his depiction of a dying Polish aristocrat in exile. Amy Irving is convincing enough as the fussy matriarch in “Voyage,” which makes her full-bodied, unabashedly confrontational sensuality as Maria Ogarev in “Shipwreck” all the more unexpected. Jason Butler Harner is a droll delight as the wry, bemused Turgenev, while David Harbour is particularly memorable as an enigmatic nihilist — a fine study of coiled aggression. Martha Plimpton does nicely by “Voyage’s” dutiful Varenka, who makes a sensible marriage and lives to regret it, but is an absolute revelation in the third play as the emotionally volatile Natasha, whose vivacious, impetuous nature hardens into a mass of vacillating feelings fueled by self-recrimination. As great as she was in the recent Shining City, is it in this role that she truly confirms her status as a stage actress of remarkable presence and charisma.

his self-satisfied complacency being slowly eroded by the harsh winds of change, and supplies moments of unbearable poignancy later on in his depiction of a dying Polish aristocrat in exile. Amy Irving is convincing enough as the fussy matriarch in “Voyage,” which makes her full-bodied, unabashedly confrontational sensuality as Maria Ogarev in “Shipwreck” all the more unexpected. Jason Butler Harner is a droll delight as the wry, bemused Turgenev, while David Harbour is particularly memorable as an enigmatic nihilist — a fine study of coiled aggression. Martha Plimpton does nicely by “Voyage’s” dutiful Varenka, who makes a sensible marriage and lives to regret it, but is an absolute revelation in the third play as the emotionally volatile Natasha, whose vivacious, impetuous nature hardens into a mass of vacillating feelings fueled by self-recrimination. As great as she was in the recent Shining City, is it in this role that she truly confirms her status as a stage actress of remarkable presence and charisma.

As impressive as everyone in the cast is, top acting honors must be conferred upon the luminous Ms. Ehle, who excels in three strikingly different roles. The tremulous delicacy that she brings to her performance in “Voyage” as the frail, gentle Liubuv, who finds bittersweet if fleeting happiness in the blush of first romance, exists in stark contrast to the firm-minded pragmatism of “Salvage’s” Malwida, the perspicacious German governess who exerts a steadying influence on the children of the Herzen household while keeping a wary eye fixed on the reckless behavior of its elders. It is in “Shipwreck,” however, that the actress is most prominently featured, and where she makes her most indelible impression. Far from the square-shouldered, sensible spinster of Part 3, or the pale, shy ingenue of Part I, Natalie Herzen is a rose in full bloom, a ravishing, vibrant romantic heroine who follows her heart into uncharted territory even as the ground beneath her feet begins to give way. The actress creates a captivating study in contradictions; winsome yet seductive, incisive yet wrong-headed, alternately reflective and impulsive, she provides the trilogy with its richest characterization, and its most lyrical.

As evidenced by her brilliant, Tony-winning turn in The Real Thing, Ehle has an instinctive grasp of the nuances of Stoppard’s language; her delivery is so natural and assured that it doesn’t even sound scripted, but rather something being thought up freshly on the spot. This is something I haven’t observed with any other actor in a Stoppard play, or really with many stage actors in general (stage acting seemingly necessitates a certain degree of staginess). The actress’s proficiency with dialogue is made all the more remarkable by its artlessness; although her physical transformation from role to role is quite stunning, her command of the language allows her to thoroughly embody her characters to a point where the effort is no longer visible.

The production itself is top-notch. Director Jack O’Brien corrals the action with a remarkably assured hand, bringing cohesion and succinctness to an occasionally unwieldy text, while Bob Crowley and Scott Pask’s ingenious scenic designs, Brian MacDevitt’s impressionistic lighting and Catherine Zuber’s sumptuous costumes create a resplendent visual tapestry which is stunning to behold. During the intermission of another show I attended this past week, I overheard three other theater patrons describing The Coast of Utopia as a great big, thundering bore. Truth be told, there are moments when it stalls and one’s focus is given to wander —

I have a feeling that “Shipwreck,” by my estimation the weakest of the three plays, would be a rather interminable affair if not for the invaluable contribution of Ms. Ehle, who is fortuitously placed as the center of its action. Stoppard is fond of big ideas and, perhaps in an effort to give his audiences a better chance of latching onto them, stresses his points through repetition. This is not an approach that will resonate with everyone — a few seats over from where I was sitting during “Shipwreck,” Martha Stewart could be observed snoozing away on the aisle (she woke up at intermission, talked on her cell for a bit, then went right back to sleep during the second act). She’s a busy lady; she needs to take her rest where she can get it. For everyone else, staying awake through the entire 8½ hour marathon — while admittedly more taxing than the average theatergoing experience — is something to be heartily recommended.

Tweet

Labels: Hawke, Neil Simon, Stoppard, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Lead or supporting?

It's a debate that's been going on almost from the moment the Academy Awards instituted the supporting acting categories in 1936. Most often, people get put in the "wrong" category for marketing purposes. For example, the producers of Ordinary People had to know in 1980 that Timothy Hutton was a long shot to win lead in a year with Robert De Niro's Jake La Motta in Raging Bull, so they followed the old young performer conceit and stuck him in supporting actor where he won. Here are some examples through the history of the Oscars where I though people were in the wrong category. At the Tony Awards the use the criteria (though it can be overturned) that if you are above the title you are a lead, if you are below you are featured. This had led to cases where Joel Grey got left out of a nomination for the Broadway revival of Chicago and when the same role can be featured some years and leads others (such as the King in The King & I and the M.C. in Cabaret. Feel free to agree or disagree or add your own.

1936: In the very first year, they really sort of messed up by putting Luise Rainer up as lead in The Great Ziegfeld. She won anyway.

1937: Even though Roland Young was as much a lead as Cary Grant and Constance Bennett in Topper, he got relegated to supporting actor where he lost.

1939: An insanely strong years for movies and performances, somehow Greer Garson made the cut as lead in Goodbye Mr. Chips when she shows up late in the film and disappears soon after.

1940: Walter Brennan won his third supporting actor Oscar in five years for his great performance in The Westerner, but he was as much a lead as Judge Roy Bean in that film as Gary Cooper was.

1944: The Oscars themselves got screwy this year nominated Barry Fitzgerald's turn in Going My Way in both the lead and the supporting categories. He won supporting and they changed the rules after that so the same performance couldn't pop up in both. In the same year, they relegated the great Claude Rains to supporting actor for his title role in Mr. Skeffington, where he is barely off screen for most of the movie.

1947: Many people argue over this one but I think that Edmund Gwenn's Santa Claus in Miracle on 34th Street is a lead, but he won in supporting.

1950: Some people think that Anne Baxter was supporting in All About Eve, but I think they were right to put both her and Bette Davis in lead.

1956: I think the great James Dean was clearly supporting in Giant and who knows — if they'd stuck him there, he might have won.

1958: Really the entire cast of Separate Tables was supporting, which made David Niven's win all the more ridiculous. The same year, it can also be argued that Shirley MacLaine was really supporting in Some Came Running, though she snagged her first lead nomination for it.

1959: Practically the entire field of best actress contenders could have been considered supporting. Only Doris Day and Audrey Hepburn were true leads. Neither Katharine Hepburn nor Elizabeth Taylor can really be called a lead in Suddenly Last Summer and that year's winner, Simone Signoret in A Room at the Top, is definitely supporting — though she is great.

1962: One of the first instances of sticking the young in supporting. Mary Badham's Scout is really the lead of To Kill a Mockingbird, but she got stuck in supporting with another arguable young lead — Patty Duke in The Miracle Worker.

1963: Patricia Neal deserved an Oscar for her work in Hud — but it should have been in supporting actress. There really is no question here — she's not a lead.

1967: Both Anne Bancroft's turn in The Graduate and Katharine Hepburn's in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner are arguably supporting turns.

1968: Ron Moody's delightful Fagin in Oliver! is yet another supporting role that sneaked in the lead field. In the same year, Gene Wilder's Leo Bloom in The Producers was on screen nearly as much as Zero Mostel's Max Bialystock, though he got stuck in supporting. When the musical version hit Broadway decades later, both Max and Leo were nominated as leads. When the musical was turned into a lame movie, Matthew Broderick's Leo was campaigned as supporting, to no avail.

1970: Again, they were reaching to fill out the lead actress slate and that's how Glenda Jackson got nominated there for Women in Love and won.

1972: Many people believe that Marlon Brando and Al Pacino are in the wrong categories for The Godfather, that Pacino is the true lead and Brando supporting. I go back and forth on what I think and I've never settled on a decision. That same year, Paul Winfield and Cicely Tyson were both nominated as leads for Sounder when young Kevin Hooks is the real star. Winfield is especially out of place, since he spends much of the film off-screen in prison.

1984: Haing S. Ngor won supporting actor for The Killing Fields, but I say he is a co-lead with Waterston, since the second half of the movie focuses on his character almost exclusively.

1988: Again, a young actor gets stuck in the supporting ghetto by virtue of his age. There can be no argument that Running on Empty was about River Phoenix's character, but he didn't get a shot at lead.

1989: To my eyes, Dead Poets Society is an ensemble about the kids and Robin Williams' teacher was supporting. The same year, I think a case can be made that Martin Landau was the lead of Crimes and Misdemeanors.

1991: We get to probably the most obvious of all cases of mistaken categorization: Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs. Hannibal Lecter is in the 2-hour film for less than 30 minutes, he doesn't enter right away and once he escapes, he's never heard from again until the film's coda. There is no doubt in my mind — Hopkins is supporting here and he should have won supporting.

1996: A less-argued case here, but one I feel strongly about. Frances McDormand should have been in supporting for Fargo. She doesn't enter the movie for 30 minutes and then she disappears for significant stretches. William H. Macy who was nominated for supporting actor actually has more screen time than McDormand. When you time it, the film is almost equally divided between McDormand, Macy and Steve Buscemi, so they are either all lead or all supporting in my book and I say supporting. Also in 1996, Geoffrey Rush's work in Shine is really more limited than you'd think for a lead performance. I've never timed it (because I didn't want to sit through it again) but I bet Noah Taylor has almost as much screen time as the younger David Helfgott.

2001: Another case where marketing trumpeted facts and Ethan Hawke got put in supporting actor for Training Day when he's in the movie before Denzel Washington and after him as well with no significant absences.

2002: A mess of issues involving The Hours, where there again is really no lead and it sure seems like the supporting-nominated Julianne Moore and the non-nominated Meryl Streep have as much if not more screen time than lead winner Nicole Kidman.

2004: One of the biggest miscategorizations and unnecessary nominations of all time: Jamie Foxx in Collateral. He's so clearly the lead in that movie, in it before and after Tom Cruise shows up. It's not like Foxx wasn't going to win lead for Ray, so this nomination boggles my mind.

2005: This year has one glaring questionable categorizations Is Jake Gyllenhaal any less a lead in Brokeback Mountain than Heath Ledger? I don't think so. Of course, I also think Gyllenhaal's work is noticeably weaker than Ledger's, but that's not part of this discussion.

Tweet

Labels: Bancroft, Bette, Brando, Denzel, Garson, Hawke, Hopkins, James Dean, K. Hepburn, Landau, Liz, Luise Rainer, MacLaine, McDormand, Niven, Pacino, Patricia Neal, Rains, Robin, W. Brennan

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, December 17, 2005

From the Vault: River Phoenix (1970-1993)

On the same day cinema legend Federico Fellini died at age 73 following a landmark career, a film artist 50 years younger than Fellini also passed away.

On the same day cinema legend Federico Fellini died at age 73 following a landmark career, a film artist 50 years younger than Fellini also passed away.While Fellini leaves an impressive and influential body of work, the full promise of River Phoenix's acting career will never be fulfilled because the young actor died Sunday at the age of 23. As tends to be the case in the deaths of young performers, the circumstances of his death, which are still unclear as of this writing, will likely overshadow Phoenix's body of work.

They shouldn't. Though his career was tragically brief, Phoenix did leave an impressive body of work as one of the foremost talents of the generation born after 1961.

His performances embodied his generation's restless spirit as well as its hidden strengths. At times, Phoenix was undisciplined but mostly his talent overflowed. Phoenix was also one of the rare examples of a performer who began his career at a young age but was able to adapt and grow into adult roles.

The first time I noticed Phoenix was in the 1985 television movie Surviving, one of the many teen suicide-theme telefilms made in the mid-'80s. The film starred Zach Galligan, then hot off 1984's Gremlins, and Molly Ringwald, the reigning princess of John Hughes' teen film fiefdom of the time.

Phoenix played Galligan's younger brother — the actor must have been about 14 — and he gave the most effective performance in the movie.

Now, eight years later, hardly a peep is heard from the careers of Galligan and Ringwald while, in contrast, Phoenix's star continued to ascend. Prior to his death, Phoenix was set to play the role of the interviewer in Neil Jordan's film of Interview With the Vampire starring Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise.

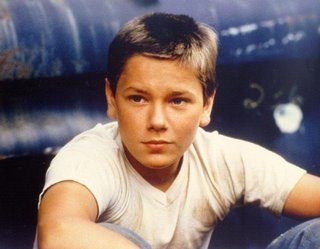

Following Surviving, Phoenix soon began popping up in big-screen movies. He made the forgettable Explorers, which co-starred Ethan Hawke, another rising talent of the 13th generation.

Phoenix's real breakthrough, though, came with two films in 1986. First, in Rob Reiner's Stand By Me, he stood out among the four young actors, playing the kid whose tough veneer masked an inferiority complex. Later that same year, he took what could be considered his first lead, playing Harrison Ford's son in The Mosquito Coast. He was the narrator and the story focused on his reaction to and relationship with a radical and possibly delusional father.