Friday, August 03, 2012

Edward Copeland's Top 100 of 2012 (20-1)

Charlie Chaplin was audacious enough to continue making silent films (although he did allow for sound effects and an occasional song) all the way to 1936. In my opinion, he saved the Little Tramp's best for last in this hysterical tale of man vs. the modern age. The comedy is as funny as you'd expect and even more pointed than usual. Since Chaplin knew the Little Tramp was making his swan song, he even let him waddle off into the sunrise. Sound didn't stop Chaplin, who had two great sound efforts to come with The Great Dictator and Monsieur Verdoux. Still, his early works are the most precious gifts. Truly, his silence was golden.

When compiling the 2007 list, I feared it was becoming too Hitchcock-centric, forcing the omission of other great filmmakers but dammit, he made so many films that mean so much to me, it would be dishonest to place a quota on him. In the intervening five years, seeing Strangers several more times only has lifted it in my extreme. Hitch's directing gifts come off at his most stylish and Robert Walker's wondrous performance as the sensitive sociopath Bruno who expects the wimpy Farley Granger to live up to his part of a hypothetical murder deal remains chilling (and darkly funny) to this day. One of the biggest leaps from the last list.

Buster Keaton always shares the title with Charlie Chaplin as one of the two great silent clowns and The General continues to be Keaton’s masterpiece 85 years later. However, while it doesn’t lack for laughs, the film more accurately could be called an adventure than a comedy. The realism of the film’s Civil War setting also proves quite striking and even though Keaton’s character Johnny Gray fights for the Confederacy against the Union, neither side comes off as particularly villainous and the film doesn’t contain the racist elements of something like Birth of a Nation. The film’s humor stems from Johnny’s two loves: his train and the woman he longs for who won’t love him until he joins the war effort, even though he’s been rejected as a fighter because of his skills as an engineer. The General never grows old.

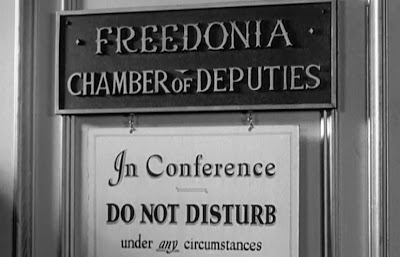

When Mickey (Woody Allen), depressed and suicidal, wanders into a movie theater in Hannah and Her Sisters, it's this inspired mixture of lunacy that brings him back around. After all, who can sit through Duck Soup and not feel better afterward. The question as to which Marx Brothers vehicle was the best got settled a long time ago and Duck Soup won. With its classic mirror scene and the loosest of plots designed to make the insanity of war look even crazier, I never get tired of Duck Soup. Watch it if only for the great Margaret Dumont. Remember, you are fighting for her honor, which is more than she ever did.

As a journalist, His Girl Friday contains one of my favorite nonsequiturs in the history of film. Delivered with frantic panache by Cary Grant as unscrupulous newspaper editor Walter Burns: "Leave the rooster story alone. That's human interest." Oh yeah, this may also be one of the funniest films ever made with rapid fire dialogue, a great sparring partner for Grant in Rosalind Russell and a priceless supporting cast to boot. It's the best remake ever made (and the film it was based on, The Front Page, is pretty damn good too). Making Hildy Johnson a woman and Burns' ex-wife was a stroke of genius. Besides, when you watch any version of this story where Walter and Hildy are both men, it's clear this isn't a platonic working relationship. I don't advise any more remakes (forget Switching Channels, if you can), but I wonder how it would play if the leads were two gay men?

As I wrote when marking the 100th anniversary of Reed's birth (forgive my self-plagiarism, but it makes this enterprise go faster), "Rewatching The Third Man recently, it once again captivated me from the moment the great zither music by Anton Karas begins to play over the credits.…If you haven't seen The Third Man (and shame on you if you call yourself a film buff and you haven't), watching the Criterion DVD really is the way to go, not only for a crisp print but to be able to compare the different versions offered for British and U.S. audiences (though only the different openings are included — we don't see what 17 minutes David Selznick cut for American audiences). With its great scenes of Vienna, sly performances and perhaps the greatest entrance of any character in movie history, The Third Man stays near the top of all films ever made, even nearly 60 years after its release."

I don’t know what I was thinking ranking Seven Samurai so low on my 2007 list. Having seen it a couple more times since, I’ve rectified that error. All films this long should hold their length as well as this rollicking adventure does. Each time I see it, it transfixes me from beginning to end. Hacks like Michael Bay should look to a film such as Seven Samurai and discover how characters trump stunts, explosions and special effects in great action-adventure films. It's amazing that with such a large cast, not just of the title samurai but of the farmers they defend as well, the actors and Kurosawa develop so many distinct and worthy portraits. Granted, the running time helps, but they establish characters rather quickly from Takashi Shimura (unrecognizable from his role as the dying bureaucrat in Ikiru) as the lead samurai organizing the mission to the brilliant Toshiro Mifune as Kikuchiyo, a reckless samurai haunted by his past as a farmer's son. Full of action, humor, sadness, a bit of romance and plenty of heart, its influence on so many films that have come since can’t be calculated.

Currently, we live in a time of a vicious circle: Movies inspire theatrical musicals which in turn become movie musicals (or in most cases, don't. Don't be looking for Leap of Faith: The Musical on the big screen anytime soon). Still, there was a time when musicals were created as motion pictures. Singin' in the Rain remains the very best example of one of those. The songs soar, the dance numbers inspire and the performances evoke joy. On top of that, it's even a Hollywood story, set in the awkward time between silent film and sound and milking plenty of laughs from the situation, especially through the spectacular performance of Jean Hagen as a silent superstar with a voice hardly made for sound and a personality barely suitable for Earth. Gene Kelly gives his best performance, a young Debbie Reynolds shines and Donald O'Connor makes us all laugh. Decades later, Singin' in the Rain got transformed (if that's the right word) a Broadway stage version. It wasn't very good. Stick with the movie.

When I wrote about this film for the Screenwriting Blog-a-Thon hosted by Mystery Man on Film in 2007, I said, "As far as I'm concerned, this film is Allen's masterpiece. Others will cite Annie Hall or Manhattan or some other titles and while I love Annie Hall and many others well, over time The Purple Rose of Cairo is the Allen screenplay that has reserved the fondest place in my heart. The screenplay isn't saddled with any extraneous scenes and no sequence falls flat as it builds toward its bittersweet ending. For me, it's Woody Allen's greatest screenplay and one of the best ever written as well." I've been pleasantly surprised at the number of people who have said to me since I wrote that how they agree, even among moviegoers who declare themselves not to like Woody Allen as a rule. It's the perfect blend of comedy, fantasy and realism and one of the greatest depictions of the magic of movies ever put on film. In The Purple Rose of Cairo, when Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels) and his pith helmet step off the screen, the repercussions end up being both hilarious, touching and painfully real.

While for me Jules and Jim stands as the high watermark of the French New Wave films, when you look objectively at the story of Jules and Jim, it may employ many of that movement's techniques but many aspects of Truffaut's film set it apart from its cinematic brethren such as its period setting and a time span that covers more than two decades separates it from the movement as well. However, that doesn’t affect the film’s magnificence. In a funny way, the 1962 film forecast the free love movement to come later that decade except its source material happened to be a semiautobiographical novel set in the early part of the 20th century. The prurience though lies in the mind of the fuddy duddy because part of what makes Jules and Jim so special comes from Truffaut's refusal to pass any judgment, be it positive or negative, upon the behavior of his characters. Despite the director's own criticism many years down the road that the film isn't cruel enough when it comes to love, the three main characters do suffer by the end but he doesn't paint it as punishment for their sins. In a 1977 interview, Truffaut said he thought he was "too young" when he made Jules and Jim. If he'd made it at any other age, it wouldn't be the same movie and probably wouldn't hold the same appeal for so many. For Jules and Jim to grab you, really grab you, I think you need to be young when you see it the first time, and that's why Truffaut, not yet 30 but captivated by the novel since 25, had to be young as well.

Wilder’s screenplay with Charles Brackett and D.M. Marshman Jr. proves surprisingly malleable, never fitting easily into one genre and playing differently in each viewing. It can be the darkest of Hollywood satires or the tragedy of a woman driven insane by a world that’s passed her by. Gloria Swanson’s brilliant performance as Norma Desmond can come off as a vulnerable madwoman or a master manipulator. Similarly, William Holden’s down-on-his-luck screenwriter Joe Gillis looks like a shallow opportunist in some scenes, an in-over-his-head dupe in others. The layers make Sunset Blvd. fresh and endlessly watchable. Wilder and his co-writers always produced great dialogue, but I believe Sunset Blvd. stands as Wilder’s greatest work as a director as well.

Hitchcock blessed us with so many classics, it’s hard to pick the best. This list contains seven Hitchcocks, but Rear Window stands tallest to me. I’ll allow two great directors to state my case. First, François Truffaut from The Films in My Life: “Rear Window is…a film about the impossibility of happiness, about dirty linen that gets washed in the courtyard; a film about moral solitude, an extraordinary symphony of daily life and ruined dreams." From David Lynch, as he wrote in Catching the Big Fish: “It's magical and everybody who sees it feels that. It's so nice to go back and visit that place." David, I couldn’t agree more.

Goodfellas rarely gets selected as the premier example of Scorsese’s brilliance as a filmmaker — and that’s a damn shame because, within its two hour and 20 minute running time, Goodfellas not only encapsulates Scorsese and filmmaking at their best but might be the director’s most personal film. If you wanted to demonstrate practically any aspect of moviemaking to a novice — editing, tracking shots, reverse pans, effective use of popular music — Scorsese disguised a film school in the form of this feature film about low-level gangsters. Goodfellas also happens to be the director’s most re-watchable film and, in a career stocked with masterpieces, it remains my favorite.

Every time I return to Paddy Chayefsky’s prescient screenplay, something new leaps out that I didn’t catch before. Most recently, it’s from one of Howard Beale’s monologues once he’s become the UBS network’s star. As part of the speech, delivered by the late, great Peter Finch, Beale tells his viewers, “Because you people, and 62 million other Americans, are listening to me right now. Because less than three percent of you people read books! Because less than 15 percent of you read newspapers!” Chayefsky died long before the Web revolution so remember that the next time someone blames the newspaper industry's death on the Internet. Better yet, watch Network and revel in the delicious words, magnificent ensemble and Lumet’s fine direction.

Many prefer the Kubrick of 2001: a Space Odyssey or later works such as A Clockwork Orange or Barry Lyndon, but I’ve always found him best when satirical, especially when that sharp humor took aim at the futility of war as in the underrated Full Metal Jacket, the great Paths of Glory and the best of the bunch, the incomparable Dr. Strangelove. To take the prospect of nuclear apocalypse instigated by a general driven mad by his impotence and produce one of the wall-to-wall funniest films ever was no small achievement, but having Peter Sellers in his multiple roles, Sterling Hayden and, most of all, George C. Scott’s hyperbolic, acrobatic and energetic work as Gen. Buck Turgidson, sure helped. That's not to mention Slim Pickens and Keenan Wynn as well and the surreal beauty of that closing of multiple mushroom clouds backed by that wonderfully ironic song.

So rarely does the best picture Oscar go to the best film, it always amazes me that the Academy recognized Casablanca (though for 1943, since it didn’t open in L.A. until a few months after its New York premiere). Claude Rains’ irreplaceable Captain Renault may say, “The Germans have outlawed miracles,” but the most miraculous thing of all was that a screenplay without an ending and based on an unproduced play managed to coalesce into the finest movie the Hollywood studio system ever produced. With a superb ensemble of character actors and stars delivering dialogue with more memorable lines than nearly any other film ever, courtesy of screenwriters Julius J. & Philip G. Epstein and Howard Koch, play it forever, Sam.

It does worry me that we seem to lack a filmmaker as ballsy as Robert Altman was (first person to suggest Paul Thomas Anderson gets punched in the face). Thankfully, he left us his body of work (some dogs to be certain, but the ecstasies we receive from his great ones allow us to forgive). For me, Nashville never wavers from its spot at the top of the Altman charts. It’s a musical, but not really. It’s about politics, but not really. We get to watch 24 characters intersect (or not) as Altman and screenwriter Joan Tewksbury design a tapestry displaying a picture of America on the eve of its bicentennial. It also presents ideas that in their own way prove as prescient as those in Network.

Many of the greatest films turn out to be examples of triumph over adversity and that certainly proved to be the case with Children of Paradise, Carné’s two-part masterpiece made during the Nazi occupation of France. When I wrote at length about this deceptively simple tale of mimes and actors, criminals and the aristocracy, I said that if I revised my 2007 list, the film likely would rise higher than its 18th rank. As you see, it most definitely has. Better to experience its beauty and magic than attempt to briefly describe it.

One wonders what the total would be if we calculated the number of words written extolling the brilliance and significance of Orson Welles’ filmmaking debut. Granted, the curmudgeons and contrarians exist and while not a day goes by that I don’t remind someone that all opinions are subjective by definition, Citizen Kane looms as the behemoth that practically defies that statement. Its status as a cinematic masterpiece comes close to being an objective truth. I have nothing new to add about this wonder. The film speaks for itself.

After what I wrote about Citizen Kane, you’d think it would rest in my top spot, but Renoir’s exquisite tragicomedy grabbed a foothold in my Top 10 as soon as I saw it in college and it took only one or two more viewings for Rules to clinch the No. 1 perch where it’s remained for more than two decades. Something personal within the film (too much identification with Renoir’s character of Octave; the character of Christine, who seems to cast a spell over all men who cross her path) hooks me in above and beyond the film’s artistry. If that explanation seems skimpy, I defer to what Octave says, "The awful thing about life is this: Everybody has their reasons."

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Carné, Carol Reed, Chaplin, Curtiz, Gene Kelly, Hawks, Hitchcock, Keaton, Kubrick, Kurosawa, Lists, Lumet, Renoir, Scorsese, Truffaut, Welles, Wilder, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, April 05, 2012

Chosen — twice

to audition for Elvis. There were so many of us in line that day and I can't believe I got the part." — former actress Dolores Hart

— Mother Prioress Dolores Hart of The Abbey of Regina Laudis, Bethlehem, Conn.

By Edward Copeland

Dolores Hart's acting career spanned a mere six years from 1957 through 1963 on stage, television and, most famously, the silver screen, where she worked opposite such leading men as Anthony Quinn, Montgomery Clift, Robert Wagner and twice with Elvis Presley, where Hart received Presley's first onscreen kiss in 1957's Loving You. In 1963, Hart found a co-star for life with the biggest name she'd worked with so far — Jesus Christ — when Hart abandoned her stardom to devote her life to God as a Benedictine nun in a rural Connecticut abbey. The documentary short about Mother Prioress Dolores Hart's life today, God is the Bigger Elvis, which was among the nominees for the 2011 Oscar nominees for documentary short subject, debuts on HBO tonight at 8 Eastern/Pacific and 7 Central.

Hart's film career consisted of 10 films, admittedly none of which I've seen, but in director Rebecca Cammisa's film, you recognize that Hart, nearly 50 years removed from her former vocation, retains the charisma that captured the attention of those who cast the then-19-year-old Hart in her first film opposite Elvis. Mother Prioress Dolores Hart admits that she prayed that she would win the role — she converted to Catholicism at the age of 10 — but interestingly the documentary doesn't mention that her father, Bert Hicks, was a bit player in movies in the 1940s and that a visit to the set of the Otto Preminger film he appeared in, 1947's Forever Amber, put the idea of acting into young Dolores' head. (Another anecdote the film neglects: Mario Lanza was Hart's uncle by marriage.)

What the documentary does reveal about Hart's parents is that they had her as teens of 17 and 18 and her grandmother thought that the pair had created a situation so tragic, Hart's mother should abort her. That's a fairly startling anecdote, considering it occurred in 1938, that the subjects drops out as soon as it gets mentioned. On the other hand, while this documentary concerns a woman who abandoned stardom for life as a nun, the film doesn't come off as overtly religious (Director Cammisa's mother actually used to be a nun).

Even though God is the Bigger Elvis focuses on Hart and the works at The Abbey of Regina Laudis in Bethlehem, Conn., it does take time to speak to some other members of the order about what brought them such as novice nun Sister John Mary, who came from the corporate and political world and addictions to drugs and alcohol. She says she still gets stares when she attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in her habit. However, this short belongs to Mother Prioress Dolores Hart, which makes it all the more surprising the many details you can find in a cursory search of the Web that didn't make it into the movie. There seems to have been more than enough material out there for a feature. For example, though the short does talk about Hart's involvement in a performing arts program out of the abbey, the film omits any reference to the fact that the open-air theater at the abbey, The Gary-The Olivia Theater, that was built in 1982 came about largely through the aid of Patricia Neal, who was buried at the abbey when she died in 2010.

Commenting on Neal's death to Tim Drake at the National Catholic Register. I learned that while Hart left acting behind nearly 50 years ago, she didn't completely abandon Hollywood as she maintains an active voting membership in the actors' branch of the Academy. The interview also shares a story that seems awfully pivotal to her decision to become a nun. When the actress went to Rome in the early 1960s to play Clare in Michael Curtiz's Francis of Assisi. The young Hart got the opportunity to have a meeting with Pope John XXIII, where she informed the pontiff about her role as the future saint.

"It was quite startling when I met his Holiness. I wasn’t prepared for it. When I greeted him I told him my name was Dolores Hart. He took my hands in his and said, 'No, you are Clara.' I replied, 'No, no, that’s my name in the film.' He looked at me again and said, 'No, you are Clara.' I wanted to sink to the floor, because I wasn’t there to begin arguing with the Pope. It gave me great pause for a number of hours. Being young, I dismissed it as one of those things that happened, but it stayed very deeply in my mind for a long time."

The only other problem I found with the documentary isn't one of omission but what seems to be a deliberate conflation of chronology. The film makes it appear as if she first visited the abbey toward the end of her career, coming at the suggestion of a friend as the young

Hart faced exhaustion following nine months of appearing on Broadway in the hit comedy The Pleasure of His Company, which opened in 1958. The play co-starred George Peppard and was directed by and starred Cyril Ritchard and included a cast of old pros such as Walter Abel and Charlie Ruggles (who won the Tony for best featured actor in a play). The film also fails to mention that Hart's work in the show earned her a Tony nomination as featured actress in a play (which she lost to Julie Newmar for The Marriage-Go-Round) and won her a Theatre World Award, which goes to the six most promising male and female acting debuts in Broadway and off-Broadway shows in a season (included in Hart's 1958-59 class were Tammy Grimes, Larry Hagman, William Shatner and Rip Torn). While Hart visited the Abbey of Regina Laudis for the first time, she learned that as a Catholic, she shouldn't pursue a movie career because she could be "aroused sexually" and get involved with men. That leads to the saddest part of the film. Hart had become engaged to another good Catholic, an architect named Don Robinson. Even today, she describes it as a "terrifying time" as she found herself torn between her love for Don and the unmistakable call beckoning her life in the abbey. Needless to say, Robinson's heart broke and though he admits to dating some other women eventually (it never indicates that he married) he visits her once a year at the abbey. To watch this man in his 70s pine away for the woman he lost to God almost proves too much to bear.

Hart faced exhaustion following nine months of appearing on Broadway in the hit comedy The Pleasure of His Company, which opened in 1958. The play co-starred George Peppard and was directed by and starred Cyril Ritchard and included a cast of old pros such as Walter Abel and Charlie Ruggles (who won the Tony for best featured actor in a play). The film also fails to mention that Hart's work in the show earned her a Tony nomination as featured actress in a play (which she lost to Julie Newmar for The Marriage-Go-Round) and won her a Theatre World Award, which goes to the six most promising male and female acting debuts in Broadway and off-Broadway shows in a season (included in Hart's 1958-59 class were Tammy Grimes, Larry Hagman, William Shatner and Rip Torn). While Hart visited the Abbey of Regina Laudis for the first time, she learned that as a Catholic, she shouldn't pursue a movie career because she could be "aroused sexually" and get involved with men. That leads to the saddest part of the film. Hart had become engaged to another good Catholic, an architect named Don Robinson. Even today, she describes it as a "terrifying time" as she found herself torn between her love for Don and the unmistakable call beckoning her life in the abbey. Needless to say, Robinson's heart broke and though he admits to dating some other women eventually (it never indicates that he married) he visits her once a year at the abbey. To watch this man in his 70s pine away for the woman he lost to God almost proves too much to bear.Overall, nitpicking aside, God is the Bigger Elvis provides an interesting profile of a woman who made a decision most people wouldn't make, even if the details deserved more fleshing out and it would have withstood more than its 35-minute running time. The documentary premiere on HBO at 8 tonight Eastern/Pacific and 7 Central. It airs several more times throughout April and will be available on HBO GO after its debut.

Tweet

Labels: 10s, Awards, Clift, Curtiz, Documentary, Elvis, HBO, Oscars, Patricia Neal, Preminger, Rip Torn, Shatner, Shorts, Television, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, December 15, 2011

“Sitzen machen!”

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

The very first Billy Wilder film I watched as part of my burgeoning film education wasn’t one of his acknowledged classics such as Double Indemnity (1944) or Sunset Blvd. (1950) — or even Some Like it Hot (1959) or The Apartment (1960) but a movie I consider “second-tier” Wilder, the 1961 Cold War comedy One, Two, Three. Keep in mind that I don’t refer to the film as second-tier because I dislike it or am trying to denigrate the work; it’s just that with the passage of time, the topicality of One, Two, Three hasn’t particularly worn well, something that I’ve also noticed in Ninotchka (1939), a Wilder-scripted comedy (but directed by Ernst Lubitsch) whose plot and themes are revisited in the later feature. (One, Two, Three also contains echoes of the filmmaker’s earlier Sabrina, the 1954 romantic comedy starring Audrey Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart and William Holden.)

The dated political content of One, Two, Three doesn’t do it any favors, but this is nevertheless going to be an enthusiastic review of a film that debuted in motion picture theaters 50 years ago on this date. “Second-tier” Wilder is miles and away better than the best movie helmed by any director today, and with his longtime partner I.A.L. “Izzy” Diamond, Billy crafted a fast, frenetic and funny farce (based on a 1929 play, Egy, kettö, három, by Ferenc Molnár) that still can leave an audience breathless with laughter. The icing on this cinematic cake is that, before he returned briefly to movies for Ragtime in 1981, One, Two, Three served as the penultimate cinematic swan song for the legendary James Cagney.

C.R. “Mac” MacNamara (Cagney) is head of operations for Coca-Cola in West Berlin, a month or two before the closing of the Brandenburg Gate (and subsequent construction of the Berlin Wall). Company man Mac is extremely loyal to the Pause That Refreshes, and has been working diligently to advance himself, with an eye on assuming the post of European operations in London by shrewdly brokering a deal to introduce the soft drink to the Soviet Union. (Mac was formerly in charge of Coca-Cola’s interests in the Middle East but a mishap involving Benny Goodman resulted in Mac’s demotion after the bottling plant was destroyed in a riot.) He’s scheduled to meet Soviet representatives Peripetchikoff (Leon Askin), Borodenko (Ralf Wolter) and Mishkin (Peter Capell) to discuss introducing the soft drink behind the Iron Curtain, and is juggling that conference with plans to further his “language lessons” with luscious secretary Fräulein Ingeborg (Lilo Pulver).

The roguish MacNamara is planning to take advantage of his wife Phyllis’ (Arlene Francis) scheduled trip to Venice with their two children to dally with Ingeborg, but those plans are put on hold when Mac receives a call from his boss, Wendell P. Hazeltine (Howard St. John), in Atlanta. Hazeltine’s daughter Scarlett (Pamela Tiffin) is en route to Berlin, and he’s entrusted Mac to keep close tabs on her since Scarlett is a bit of a shameless flirt (despite being only 17). As an example of her hot-blooded tempestuousness, Mac and Phyllis meet her at the airport just in time to find her awarding herself as a lottery prize to the flight crew (the winner is a man called Pierre, prompting Phyllis to dub him “Lucky Pierre”). What starts out as a two-week assignment stretches into two months, but Mac is pleased that he’s keeping Scarlett on a tight leash.

On the day before the Hazeltines travel to Berlin to collect their daughter, Scarlett turns up missing. Mac learns from his chauffeur (Karl Lieffen) that the girl has been bribing him to let her off at the Brandenburg Gate every night to allow her to cross the border into East Berlin. Devastated by this news, MacNamara expresses relief when Scarlett turns up at his office, but then is hit by a streetcar when she announces that she’s been spending all her time with an East German Communist named Otto Ludwig Piffl (Horst Buchholz), whose political philosophy fills Mac with utter revulsion. The problem for Mac is that the fling between Otto and Scarlett has gone beyond mere puppy love — they tied the knot in East Berlin — something that will no doubt go over with her parents like flatulence at a funeral. The devious MacNamara arranges for the young Commie to be picked up by the East German authorities after they find a “Russkie Go Home” balloon affixed to his motorcycle’s exhaust pipe and a cuckoo clock (that plays “Yankee Doodle” on the hour) wrapped in a copy of The Wall Street Journal in his sidecar.

Mac’s machinations even go as far as to arranging for the couple’s marriage license to disappear from the official record, and he gloats about his triumph to a furious Phyllis, who has finally had enough of her husband’s neglect of their marriage in his pursuit of Coke advancement. The popping of champagne corks is put on hold when Scarlett faints after hearing of Otto’s arrest. An examination by a physician reveals that the girl has a Communist “bun in the oven!” Racing against an ever-ticking clock before the Hazeltines touch down in Berlin, Mac manages to spring Otto and then embarks on an extreme makeover of the hostile Bolshevik to transform him into someone whom Scarlett’s parents will approve. Against all odds, McNamars’s scheme comes off without a hitch, but his dreams of taking over as head of Coke’s European office are dashed when Hazeltine announces the job will go to his new son-in-law! Kicked upstairs to a position in the home office in Atlanta, Mac will reconcile with Phyllis and will hopefully live happy ever after.

Because the emphasis in Ninotchka is primarily on the romance between stars Greta Garbo and Melvyn Douglas, that film hasn’t dated nearly as badly as One, Two, Three, whose jibes at Cold War politics make it more of a period piece, and is likely to appeal mostly to the history majors in the audience. (Wilder’s cynicism also comes to the fore in this film in that you never really believe the romance between Scarlett and Otto. They have to stay married because there’s a “bouncing baby Bolshevik” on the way.) But if you’re able to put its topicality on a back burner, there is much to enjoy in the film; it is a spirited farce, buoyed by the participation of Cagney as the main character of C.R. MacNamara. Mac is a typical Wilder hero: not the most admirable man (he’s cheating on his wife and comes across as a bit of a jerk) but an individual who rises to the occasion when faced with a crisis. Cagney, whose screen performances were usually marked by his established persona as a fast-talking wise guy, is a marvel to watch in this film, barking out orders and, in the words of a reviewer for Time magazine, “swatting flies with a pile driver.”

Cagney did not have an easy time making the film. He was no spring chicken at the time of its production, and having to spout Wilder’s rat-a-tat dialogue at a furious pace was often difficult, particularly in one scene where the director insisted on Jimmy’s completing it in one take. Cagney was tripped up continually by the line, “Where is the morning coat and striped trousers?” It was never explained to his satisfaction why Billy refused to let him paraphrase the dialogue, and so it took 57 takes to get it done (which might explain why the finished product comes off as a little mechanical). Cagney also was not enamored of co-star Buchholz and his scene-stealing antics; Jimmy had experienced a similar incident when making Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942) and had trouble with character actor S.Z. “Cuddles” Sakall upstaging him in a scene, but he overlooked it because Sakall “was an incorrigible old ham who was quietly and respectfully put in his place by [director] Michael Curtiz.” But if Wilder hadn’t exercised his director’s prerogative and discouraged Horst to stop with the same, Cagney “would have been forced to knock him on his ass, which I would have very much enjoyed doing.”

All in all, the experience of making One, Two, Three drained Cagney and made him realize that he’d rather be enjoying retirement, and upon the movie’s completion, the actor settled in for a second career as a gentleman farmer (though he did narrate a TV special and a 1968 Western, Arizona Bushwhackers, in the interim). He was coaxed out of retirement for a small role in Ragtime in 1981 (as the police commissioner, his last big-screen appearance and a final reunion with his longtime chum/movie co-star Pat O’Brien), and an additional role in a 1984 TV movie Terrible Joe Moran where he played a retired boxer forced to used a wheelchair, but still a fighter to the core. Having suffered a stroke affected Cagney's performance somewhat and it was the final project before his passing in 1986.

In watching One, Two, Three, it almost seems like Wilder and Diamond presciently knew it would be James Cagney’s last significant silver screen work, what with all the in-jokes and references pertaining to the actor sprinkled throughout. There’s the aforementioned cuckoo clock (Cagney’s best actor Oscar was awarded for his role as George M. Cohan in Dandy), but there’s also a scene in which Jimmy picks up a grapefruit half and moves menacingly toward Buchholz’s Otto (shades of The Public Enemy!) and a funny cameo by Red Buttons as an Army MP who imitates Cagney while having a conversation with Jimmy’s MacNamara. Of course, the self-referential jokes are a staple of Wilder’s film comedies; at one point in the movie Cagney cries out “Mother of mercy, is this the end of little [sic] Rico?” as a nod toward Edward G. Robinson’s memorable last line in Little Caesar (something Billy also did in Some Like It Hot, in which George Raft asks a coin-flipping Edward G. Robinson, Jr., “Where’d you pick up that cheap trick?”).

Wilder also recycled a line used by Bogart in Sabrina, “I wish I were in hell with my back broken” (a variation of this also turns up in Wilder’s Five Graves to Cairo) and in fact, borrowed Sabrina’s “switcheroo” ending (right down to the hat and umbrella) and use of the song “Yes, We Have No Bananas” (only it’s sung in German in One, Two, Three). Music is at the center of many of the gags in the film; in addition to “Bananas,” comic set pieces use Aram Khachaturian's “Sabre Dance” (the main theme that accompanies MacNamara’s breakneck activities, described by Wilder and Diamond to be played “110 miles an hour on the curves…140 miles an hour on the straightways”), Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” and Brian Hyland’s “Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini.”

Though watching Cagney go through his paces is the main draw of One, Two, Three, his co-stars also rise to the occasion. Arlene Francis is probably best known as a panelist on the longtime TV show What’s My Line?, but she provides solid support as the acid-tongued, long-suffering Phyllis (“Yes, Mein Führer!”). The real-life antagonism Cagney had for Buchholz works to the film’s advantage, of course, but Horst has a certain goofy charm that makes his Otto likable despite his political leanings, and Pamela Tiffin is delightful as the ditzy Scarlett — many a classic movie buff has wondered why, despite high-profile showcases in films such as Summer and Smoke (1961) and Harper (1966), Tiffin’s film career never reached its full potential. Fans of Hogan’s Heroes will recognize Leon Askin as Comrade Peripetchikoff, but you can also hear Askin’s fellow Hogan player John “Sgt. Schultz” Banner as the voice of two of the characters in the film — in fact, when I watched One, Two, Three the other day, it was the first time I noticed that the voice for Count von Droste Schattenburg (the aristocrat who “adopts” Otto, played by Hubert von Meyerinck) is dubbed by character great Sig Ruman!

Jules White, the head of Columbia Studios’ comedy shorts department, once described his directorial style as “mak(ing) those pictures move so fast that even if the gags didn’t work, the audiences wouldn’t get bored.” Wilder and Diamond upped that ante with One, Two, Three; the film not only moves at lightning speed, the gags remain funny today. (My particular favorite has MacNamara calling one of the Russians “Karl Marx,” and when the comrade gives Fräulein Ingeborg a generous swat on her fanny, he quips, “I said Karl Marx not Groucho.”) In Cameron Crowe’s book Conversations with Wilder, the legendary writer-director observed: “The general idea was, let's make the fastest picture in the world…And yeah, we did not wait, for once, for the big laughs. We went through the big laughs. A lot of lines that needed a springboard, and we just went right through the springboard…” The film may not have been a box-office smash (both in the U.S. or Germany) but the final gag left an impression on me when I first saw it as a kid (“Schlemmer!”), and 50 years later watching the great Jimmy Cagney rush pell mell through farcical circumstances beyond his control remains a Wilder devotee’s delight.

Tweet

Labels: 60s, A. Hepburn, Bogart, Books, Cagney, Curtiz, Edward G., Garbo, Holden, Lubitsch, Movie Tributes, Nonfiction, Oscars, Raft, Television, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, November 21, 2011

The Last Stand

By Eddie Selover

They Died With Their Boots On, which premiered 70 years ago today, is the eighth and final pairing of Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland. It's not as famous as some of the others — for example, the pirate swashbuckler Captain Blood or the bejeweled Technicolor storybook Adventures of Robin Hood — but it deserves to be. Those are happy, exuberant movies; this is a tragedy of slowly unfolding power that leaves you unsettled and upset. It's the rare adventure movie that gets under your skin; it achieves its epic qualities through emotion rather than action. The movie is based on the story of George Armstrong Custer, the general whose command of 500 cavalrymen was overwhelmed by ten times as many Native Americans in 1876. Never were the words "based on" more of a euphemism. As history, Boots On bears only a passing resemblance to actual events — in fact the more you know about Custer, the more outrageous the film's portrait becomes. Virtually every event is twisted almost 180 degrees in order to turn a vainglorious and highly flawed man into a noble figure.

Yet even as the film moves toward its barroom-painting view of Custer and his men staging their heroic last stand surrounded by savages, it has to explain how he got there. It does so by setting him up as vain, callow, physically daring but reckless and prone to troublemaking. Cleverly, the filmmakers play the first half of the movie as a light comedy, in which Custer gets himself into one mess after another and strikes ludicrous poses trying to act like a bigger man than he is. We see him making mistakes and extricating himself through charm and luck; instinctively we know it's only a matter of time before that luck runs out.

The fact that the same thing was true of Flynn in real life gives the movie an unusual resonance. He was at least as vain as Custer, and easily as reckless; his road to fame and success was just as fast and fortunate, and left him just as unprepared to deal with real challenges. During the making of this movie, Flynn had a couple of underage girls on his yacht, an escapade that led to a long and embarrassing trial for statutory rape that turned him into a public joke after the premiere — particularly after it was revealed in court that Flynn made love with his socks on. His pre-movie life of adventure had left him with an assortment of

chronic maladies that resulted in his being declared 4-F and ineligible for the draft. Because Warner Bros. hushed this up, the public thought him a slacker for not serving in World War II as other stars did. Personal and professional disasters came faster and faster, and his drinking and drug use kept pace. Eventually booze, narcotics and dissipation made him a puffy, slurring, dead-eyed zombie before they finally killed him at the age of 50. Some presentiment of this terrible fate seems to hang over Flynn throughout Boots On. He gives one of his most sensitive and aware performances. His eyes often look wide with fright and he seems more attuned to other actors than usual. Often he pauses and hesitates before taking action, as if genuinely unsure of himself, and when he does act, it's always a shade too swiftly. He's as dashing as ever, but often he dashes right into a brick wall. Some of the credit for this must go to the great Raoul Walsh, here directing Flynn for the first time, after the actor had quarreled with his usual director, Michael Curtiz (the fact that the much-younger Flynn was married to Curtiz's ex-wife Lili Damita is strangely never mentioned in accounts of the poisonously bad relationship between the two men). Curtiz had directed Flynn like a toy action figure, throwing him into the middle of clanging swords and galloping horses and trusting him to sail above it all. Walsh's action scenes were rougher than Curtiz's, less choreographed and clever, and always suggestive of real threat — as you might expect of a man who had lost an eye in an accident.

chronic maladies that resulted in his being declared 4-F and ineligible for the draft. Because Warner Bros. hushed this up, the public thought him a slacker for not serving in World War II as other stars did. Personal and professional disasters came faster and faster, and his drinking and drug use kept pace. Eventually booze, narcotics and dissipation made him a puffy, slurring, dead-eyed zombie before they finally killed him at the age of 50. Some presentiment of this terrible fate seems to hang over Flynn throughout Boots On. He gives one of his most sensitive and aware performances. His eyes often look wide with fright and he seems more attuned to other actors than usual. Often he pauses and hesitates before taking action, as if genuinely unsure of himself, and when he does act, it's always a shade too swiftly. He's as dashing as ever, but often he dashes right into a brick wall. Some of the credit for this must go to the great Raoul Walsh, here directing Flynn for the first time, after the actor had quarreled with his usual director, Michael Curtiz (the fact that the much-younger Flynn was married to Curtiz's ex-wife Lili Damita is strangely never mentioned in accounts of the poisonously bad relationship between the two men). Curtiz had directed Flynn like a toy action figure, throwing him into the middle of clanging swords and galloping horses and trusting him to sail above it all. Walsh's action scenes were rougher than Curtiz's, less choreographed and clever, and always suggestive of real threat — as you might expect of a man who had lost an eye in an accident.At this point in her career, de Havilland had developed some serious ambitions and no longer wanted to be the clinging heroine of Flynn's boys-own-adventure movies. She only made the film at Flynn's express request, after they had cleared the air of several years of misunderstanding. By all accounts, including hers, they were seriously in love, but their relationship was undermined continually by his

immaturity and instability. Boots On is the only one of their films in which their characters have a real arc, moving from youthful high spirits into a serious relationship, into marriage and ultimately the tragedy of his death. To sweeten the deal for de Havilland, the producer Hal Wallis brought in the fine screenwriter Lenore Coffee for rewrites that rounded out the character of Libby Custer and made her a flesh-and-blood woman rather than a cardboard cutout. De Havilland responds with one of her best and most consistent performances.

immaturity and instability. Boots On is the only one of their films in which their characters have a real arc, moving from youthful high spirits into a serious relationship, into marriage and ultimately the tragedy of his death. To sweeten the deal for de Havilland, the producer Hal Wallis brought in the fine screenwriter Lenore Coffee for rewrites that rounded out the character of Libby Custer and made her a flesh-and-blood woman rather than a cardboard cutout. De Havilland responds with one of her best and most consistent performances. In their final scene, she helps him prepare for the battle of Little Big Horn. Both know he's not coming back, and they can barely look at each other while mouthing cheery sentiments they clearly don't believe for a second. They're almost getting away with it when he finds her diary and begins reading it aloud. In it, she confesses her terror over unshakable premonitions of his death. I must have written that every time you left for battle, she says. "Of course," he murmurs softly. They say their goodbyes and he leaves; she's rigid against a wall for support. The camera pulls in suddenly on her and she faints from the accumulated tension. Fainting in movies usually is phony as hell, but this time we've been holding our breaths too, and it feels like a natural reaction. In real life, de Havilland knew she'd never work with Flynn again, and she felt that he knew it as well. The scene is almost unbearable in its poignancy, for both the characters and the actors. Such is its enduring power that at a screening 40 years later, de Havilland, then about 65, walked out in the middle of it. She went to the lobby, sat down and began to cry.

Tweet

Labels: 40s, Curtiz, de Havilland, Erroll Flynn, Walsh

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, September 02, 2011

What you've seen on the big screen (but not in its original release)

By Edward Copeland

As my readers can no doubt tell, my contributors and myself don't have much in the way of original copy to offer this week (that's why you've seen three days in a row of From the Vault posts of old reviews written when the films in question originally came out prior to this blog's existence). I'm taking this "week off" because I have several projects coming up that require lots of watching and writing so I can more or less place ECOF on autopilot. It then occurred to me that this would be a great opportunity to me to run something I've always wanted to and that really isn't labor intensive.

Since seeing movies in a theater, for the most part, is a logistical impossibility for me now, I've always wanted to list the films that I was fortunate enough to see in a theater through re-releases that I either wasn't born when they originally came out, I was too young to see in their original release or somehow I missed the first time and they happened to come back. I figured that would be a great comment starter. I've only linked to reviews I wrote based on being able to see the films in a theater the way God intended. Of course, I didn't count The Rocky Horror Picture Show since it never stopped playing. I just went with alphabetical order. I hope I've recalled them all.

Hamilton Luske & Wolfgang Reitherman

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Browning, Buñuel, Coppola, Curtiz, Fellini, G. Stevens, Godard, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Landis, Lean, Peckinpah, R. Scott, Renoir, Scorsese, Welles, Whale, Wilder, Wise

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, August 08, 2011

Nursing has always seemed like a second nature to me

By Edward Copeland

Sometimes you have to wonder what made some of the pre-Code Hollywood classics such as Night Nurse, which turns 80 years old today, so shocking. Sure, Barbara Stanwyck and Joan Blondell spend an inordinate amount of time in various states of undress, but the subject matter doesn't approach the lurid level of a Baby Face (also with Stanwyck) or Red-Headed Woman with Jean Harlow. Maybe it's because even then it raised questions about the motives of some involved in the health care system or the practice of medicine. Whatever the reason, what's most important about Night Nurse is that just 20 years shy of being a century old, it remains a damn good movie.

Directed by William "Wild Bill" Wellman, Night Nurse begins in an almost comic tone before it takes a suspenseful turn in its second half. Wellman brings a lot of nice touches to the film visually. It opens from the point-of-view of an ambulance speeding through city streets on its way to a hospital's emergency's room.

Ambulance is spelled in reverse inside the driver's window. They were aiming to be reversed as many used to be so they would read correctly in other vehicles' rear-view mirrors, only they have it backward and it's written forward on the front of the ambulance. As the injured man is unloaded, the orderly guesses correctly that he's been in a car wreck. "Cement truck hit one of those Baby Austins," the ambulance driver tells him as they wheel him into the hospital. The orderly comments that you'd never catch him in one of those little cars, but the ambulance driver corrects him that the injured man was driving the cement truck. As they move through the hall, the pass a nervous father-to-be letting go of his wife's hand as she heads to the delivery room. A nurse places a screen around another man in the crowded ward and a woman asks her, "Why can't my son have a screen?" The nurse explains that it's against the rules. The woman points out that she just placed one around the other man and the nurse explains that's because that man is dying.

The camera finally moves past all the chaos as we see sharp dark shoes entering the office of Miss Dillon (Vera Lewis), the superintendent of nurses to apply for a nursing job. Her name is Lora Hart and she's played by the great Barbara Stanwyck. Miss Dillon is a bit of a harridan, barely taking her eyes off what she's doing to give Lora much attention. Her education doesn't impress her and she asks her why in the world she would want to be a nurse. Lora tries not to laugh as she notices that the woman has a habit of making a grotesque throat-clearing sound ever few seconds. "Nursing people has always seemed liked a second nature to me," Lora tells the superintendent of nurses, but she seems less than impressed and dismisses her out of hand. As Lora marches out of the woman's office, she makes certain to stop at the door and clear her throat with a smile before she leaves.

When she's exiting the hospital, a preoccupied man bumps into her, spilling the contents of Lora's purse and falling on his ass. Lora takes the stance that he was trying to be fresh with her, but he gets up and reassures her that isn't the case. He introduces himself as Dr. Arthur Bell (Charles Winninger) and asks why she was

there. She tells him she had hoped to get a job as a nurse, but that Miss Dillon didn't seem interested. Bell offers to take her back and asks her name. When she shares that her name is Lora Hart, Bell replies, "Hart — that's a good name for a nurse." Lora, escorted by Dr. Bell, returns to Miss Dillon's office. When she sees Lora with the doctor, the superintendent gets tongue-tied, but Bell doesn't give Dillon much of a chance to say anything anyway, just tells her to treat Miss Hart well and find a place for her and perhaps she can help improve things around then. He wishes Lora good luck and departs, leaving her to have a real interview with Miss Dillon. While Miss Dillon's attitude toward Lora improves slightly, mainly she wants to know why she didn't tell her before that she was acquainted with Dr. Bell. She explains that she will begin work as a probationary nurse, which means she will live in a dorm and have a curfew (in bed with lights out by 10). Because she'll just be on probation on first, she must pay strict attention to the rules or she could be let go. "Rules mean something — you'll be told about them later," Miss Dillon tells her.

there. She tells him she had hoped to get a job as a nurse, but that Miss Dillon didn't seem interested. Bell offers to take her back and asks her name. When she shares that her name is Lora Hart, Bell replies, "Hart — that's a good name for a nurse." Lora, escorted by Dr. Bell, returns to Miss Dillon's office. When she sees Lora with the doctor, the superintendent gets tongue-tied, but Bell doesn't give Dillon much of a chance to say anything anyway, just tells her to treat Miss Hart well and find a place for her and perhaps she can help improve things around then. He wishes Lora good luck and departs, leaving her to have a real interview with Miss Dillon. While Miss Dillon's attitude toward Lora improves slightly, mainly she wants to know why she didn't tell her before that she was acquainted with Dr. Bell. She explains that she will begin work as a probationary nurse, which means she will live in a dorm and have a curfew (in bed with lights out by 10). Because she'll just be on probation on first, she must pay strict attention to the rules or she could be let go. "Rules mean something — you'll be told about them later," Miss Dillon tells her.The superintendent sees another probationary nurse passing and calls out, "Maloney." Maloney (Joan Blondell) enters and Miss Wilson introduces her to Lora and says since Maloney (the film never gives her a first name,

just the initial B.) doesn't have a roommate, she should get Lora a uniform and show her the ropes. At first, Maloney isn't very friendly, seeing any new probationary nurse as competition, even handing her a uniform several sizes too large at first, but soon the girls hit it off and Maloney warns her about the different types of men to watch out for, such as interns. Just as she says that, an intern named Eagan (Edward Nugent) sticks his head in the dressing room and acts generally obnoxious. Maloney makes no attempt to hide her disdain. "Sometimes I don't like you, Maloney," Eagan tells her. "I wish I could find a way to make that permanent," she replies. What do you say newcomer?" he asks Lora. "Two-nothin' in favor of the lady," Lora concludes. Eagan knows when he's licked and leaves. "Take my advice and stay away from interns," Maloney reiterates. "They're like cancer. The disease you know, but there ain't no cure."

just the initial B.) doesn't have a roommate, she should get Lora a uniform and show her the ropes. At first, Maloney isn't very friendly, seeing any new probationary nurse as competition, even handing her a uniform several sizes too large at first, but soon the girls hit it off and Maloney warns her about the different types of men to watch out for, such as interns. Just as she says that, an intern named Eagan (Edward Nugent) sticks his head in the dressing room and acts generally obnoxious. Maloney makes no attempt to hide her disdain. "Sometimes I don't like you, Maloney," Eagan tells her. "I wish I could find a way to make that permanent," she replies. What do you say newcomer?" he asks Lora. "Two-nothin' in favor of the lady," Lora concludes. Eagan knows when he's licked and leaves. "Take my advice and stay away from interns," Maloney reiterates. "They're like cancer. The disease you know, but there ain't no cure."It must be said that while Night Nurse would barely be classified as a B picture by most at the time it was made, the movie not only surpasses that level in terms of quality, but in Wellman's distinctive touches and Barney McGill's cinematography. For instance, in one particularly effective sequence, Maloney and Lora must assist a surgery as one of their final tasks before they can take the oath and be full-fledged nurses. Lora, as we will learn, can be a bit skittish (though the growth of her strength marks the journey of both her character and the film). Maloney warns her that if she faints or messes up, she's done so hang on. They stage the scene in a large operating theater and Wellman films most of the sequence in overhead shots. The surgery doesn't go well and there's blood as the surgeon's try to save the man. Lora almost buckles, but Maloney gives her her hand. As the man dies, they show a series of almost ritualistic shots as the body gets slowly covered. The OR clears out but Lora lingers behind, waiting until the room has emptied to collapse to the floor which Wellman again captures in an overhead shot.

What's interesting is that while William A. Wellman had a reputation prior to Night Nurse (he did direct Oscar's first best picture (Wings) after all and would go on to make many more notable films), the other members of the creative team really didn't have that much else of note on their filmographies. McGill's only other significant films as a d.p. were Svengali starring John Barrymore and Michael Curtiz's The Cabin in the Cotton that kick-started Bette Davis' career. The movie was based on a novel of the same name by Dora Macy (a pen name used by writer Grace Perkins) and written by Oliver H.P. Garrett who was prolific but only made noise as a co-writer on Manhattan Melodrama (with Joseph L. Mankiewicz), Duel in the Sun (with David O. Selznick and uncredited work by Ben Hecht) and Dead Reckoning (with four other men). On Night Nurse, additional dialogue was credited to Charles Kenyon, who was just as prolific as Garrett. His most recognizable credits were helping to adapt Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream in 1935 and Robert Sherwood's play The Petrified Forest in 1936. Somehow though these people pooled together to produce crackling dialogue, memorable images and efficient storytelling out of a movie that most viewed as filler. It's a minor miracle.

Perhaps what makes Night Nurse one of those daring pre-Code pictures is that, while it never shows Lora or Maloney leading a loose lifestyle, the young single gals do sneak out of the dorm and come back in after curfew drunk. Presumably Maloney has dragged Lora out on a manhunting expedition since what type of mate

to pursue tends to be all Maloney talks about. In addition to interns being a no-no, she warns against doctors as well, saying that you'd just end up running their office while they chase other women. As for patients, for some reason Maloney thinks that "appendicitis cases are best." However, for Maloney, only one male is ideal. "There's only one guy in the world that can do a nurse any good and that's a patient with dough!" she says. "Just catch one of them with a high fever and a low pulse and make him think you saved his life and you'll be getting somewhere." Those conversations are for another time. Right now, the pie-eyed pals are more concerned with getting undressed

to pursue tends to be all Maloney talks about. In addition to interns being a no-no, she warns against doctors as well, saying that you'd just end up running their office while they chase other women. As for patients, for some reason Maloney thinks that "appendicitis cases are best." However, for Maloney, only one male is ideal. "There's only one guy in the world that can do a nurse any good and that's a patient with dough!" she says. "Just catch one of them with a high fever and a low pulse and make him think you saved his life and you'll be getting somewhere." Those conversations are for another time. Right now, the pie-eyed pals are more concerned with getting undressed in the dark and climbing into bed without tipping off Miss Dillon that they'd broken curfew. That plan goes bust thanks to Eagan, who left a surprise under Lora's blanket — a skeleton from the anatomy class that causes Lora to let out a shriek. Maloney tells her to hurry and get under the covers and act asleep, in case Dillon comes in. Lora doesn't want to be that close to the bones, but she does it. Sure enough, Miss Dillon comes in and flips the lights on. Maloney tries to fake that she just woke them up but the superintendent throws back the blanket and exclaims, "I thought so" as she sees that Maloney still has part of her clothing on. The girls fear that a firing is coming, but instead as punishment Dillon assigns them to the night shift working with the worst cases that come in off the streets: drunks, beatings, etc. As she leaves them to get some sleep, Eagan drops by to taunt them and they yell at him. Lora continues to lack the nerve to sleep where the skeleton was, so Maloney lets her crawl into bed with her for the night.

in the dark and climbing into bed without tipping off Miss Dillon that they'd broken curfew. That plan goes bust thanks to Eagan, who left a surprise under Lora's blanket — a skeleton from the anatomy class that causes Lora to let out a shriek. Maloney tells her to hurry and get under the covers and act asleep, in case Dillon comes in. Lora doesn't want to be that close to the bones, but she does it. Sure enough, Miss Dillon comes in and flips the lights on. Maloney tries to fake that she just woke them up but the superintendent throws back the blanket and exclaims, "I thought so" as she sees that Maloney still has part of her clothing on. The girls fear that a firing is coming, but instead as punishment Dillon assigns them to the night shift working with the worst cases that come in off the streets: drunks, beatings, etc. As she leaves them to get some sleep, Eagan drops by to taunt them and they yell at him. Lora continues to lack the nerve to sleep where the skeleton was, so Maloney lets her crawl into bed with her for the night.The "punishment" that Miss Dillon gives Lara and Maloney actually only serves to forward the plot. They only work there long enough to meet a new character who will play an important role going forward (and it's neither the drunk nor the intern helping to treat those coming in for help). A sharp-dressed man comes

staggering in, having lost some blood. Lora gets to work patching him up which necessitates cutting his shirt. "Hey! That's silk!" the man (Ben Lyon) objects. "That's how I knew you were a bootlegger," Lora tells him, but then she realizes his injury is a bullet wound. "That looks like it's a bullet wound!" Lora says. "Well, it's a cinch it's not a vaccination mark," he replies. By law, nurses are required to report all bullet wounds to the police, but the man begs her not to do it. Lora finds herself torn because she likes this nameless bootlegger. Maloney comes up and spots the bullet wound and tells them they have to report it — they can't risk their jobs before they even officially start them. "Maybe 56 bucks a week isn't much but it's 56 bucks," Maloney says. Eventually, Maloney gives in and she and Lora fix the bootlegger up and keep his secret. After that is when the operating room test comes and Lora and Maloney pass. The pals join the other probies and take the Florence Nightingale Pledge and become full-fledged nurses.

staggering in, having lost some blood. Lora gets to work patching him up which necessitates cutting his shirt. "Hey! That's silk!" the man (Ben Lyon) objects. "That's how I knew you were a bootlegger," Lora tells him, but then she realizes his injury is a bullet wound. "That looks like it's a bullet wound!" Lora says. "Well, it's a cinch it's not a vaccination mark," he replies. By law, nurses are required to report all bullet wounds to the police, but the man begs her not to do it. Lora finds herself torn because she likes this nameless bootlegger. Maloney comes up and spots the bullet wound and tells them they have to report it — they can't risk their jobs before they even officially start them. "Maybe 56 bucks a week isn't much but it's 56 bucks," Maloney says. Eventually, Maloney gives in and she and Lora fix the bootlegger up and keep his secret. After that is when the operating room test comes and Lora and Maloney pass. The pals join the other probies and take the Florence Nightingale Pledge and become full-fledged nurses."I solemnly pledge myself before God and in the presence of this assembly, to pass my life in purity and to practice my profession faithfully. I will abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous, and will not take or knowingly administer any harmful drug. I will do all in my power to maintain and elevate the standard of my profession, and will hold in confidence all personal matters committed to my keeping and all family affairs coming to my knowledge in the practice of my calling. With loyalty will I endeavor to aid the physician in his work, and devote myself to the welfare of those committed to my care."

It's at this point that Night Nurse makes its pivot. Aside from the great opening, when we saw anonymous characters doing their work, Lora and Maloney patching up the bootlegger and the OR scene, we've really witnessed little in the way of the practice of medicine. That pledge the newly minted nurses took (at least as far as Lora is concerned — aside from a couple of brief appearances by Maloney, Joan Blondell mostly vanishes from the film, unfortunately) means something to them, It wasn't just a line that Lora was trying to pull on Miss Dillon when she told her that "nursing has always seemed like a second nature to me." Skittishness over

skeletons and blood aside, Lora has only grown stronger and she will need that strength for what she confronts next. At the hospital, she had assisted Dr. Bell in the treatment of two sick little girls, Desney and Nanny Richey (Betty Jane Graham, Marcia Mae Jones). For some reason though, their widowed mother (Charlotte Merriam) removed Bell from the case and took them home for

skeletons and blood aside, Lora has only grown stronger and she will need that strength for what she confronts next. At the hospital, she had assisted Dr. Bell in the treatment of two sick little girls, Desney and Nanny Richey (Betty Jane Graham, Marcia Mae Jones). For some reason though, their widowed mother (Charlotte Merriam) removed Bell from the case and took them home for treatment there under a Dr. Milton Ranger (Ralf Harolde) and an ever-rotating staff of nurses who keep quitting or getting fired. Maloney currently holds the daytime shift and when the latest night nurse exits, Lora gets the job and hits it off with the children who are ecstatic, to their detriment, one falling to the floor in weakness over the excitement. The housekeeper Mrs. Maxwell (Blanche Frederici) enters to put a stop to it. Lora had been warned to be wary of the household staff, particularly Nick the chauffeur (Clark Gable, who got the role which originally was intended for James Cagney. However, when The Public Enemy hit so big earlier in 1931, the studio and Cagney agreed he shouldn't play such a small role as a hood now). Gable gets the most unintentionally funny introductions in the movie (or just about any movie). After Lora had been specifically warned about "Nick the chauffeur," when she encounters him and asks who he is he actually says in complete monotone, "I'm Nick — the chauffeur." The way that moment plays could only have been sillier if it had been followed by ominous organ music.

treatment there under a Dr. Milton Ranger (Ralf Harolde) and an ever-rotating staff of nurses who keep quitting or getting fired. Maloney currently holds the daytime shift and when the latest night nurse exits, Lora gets the job and hits it off with the children who are ecstatic, to their detriment, one falling to the floor in weakness over the excitement. The housekeeper Mrs. Maxwell (Blanche Frederici) enters to put a stop to it. Lora had been warned to be wary of the household staff, particularly Nick the chauffeur (Clark Gable, who got the role which originally was intended for James Cagney. However, when The Public Enemy hit so big earlier in 1931, the studio and Cagney agreed he shouldn't play such a small role as a hood now). Gable gets the most unintentionally funny introductions in the movie (or just about any movie). After Lora had been specifically warned about "Nick the chauffeur," when she encounters him and asks who he is he actually says in complete monotone, "I'm Nick — the chauffeur." The way that moment plays could only have been sillier if it had been followed by ominous organ music.

Lora attempts to find Mrs. Richey somewhere within the mansion to tell her what dire straits her children are in and finds that she appears to be either drunk or passed out 24 hours a day, usually on the arm of her equally inebriated boyfriend Mack (Walter McGrail). Often, the place overflows with many partying friends in a scene of bacchanalia. When Mrs. Richey nods off one time, Mack makes moves on Lora should Lora parries his pawing fairly well, but the first time she meets Nick is when he shows up and lays Mack out with a punch. Lora and Nick don't maintain a friendly relationship for long as she tells him she's calling a doctor. He warns her not to unless Dr. Ranger has given her orders to that effect. She ignores him and proceeds to the phone. Nick shouts that he runs this place, but Lora gets someone on the line so Nick knocks her out and carries her unconscious into another room.

The next day, Lora goes to see this Dr. Ranger to report what's going on, but it soon becomes clear to her that he's not particularly interested in the welfare of the children and she puts together what must be going on: The children must have a trust fund that will pass on to their tipsy mother if they die and they'll have Nick marry her and he and the doctor will steal the fortune. She threatens to report Ranger to the authorities. He

seems unconcerned, telling her she has no proof and to make such allegations will just end her career. Lora storms out and goes to see Dr. Bell who, to her surprise, agrees with everything she says but doesn't want to lift a finger to help her either since, even though he's long had suspicions about Ranger, "he is a colleague." Not much has changed in 80 years: Doctors always protect one another no matter how bad they know the other doctor is. Bell tries to put his inability to report Ranger off on "ethics." This really sets Lora off. "Oh, ethic, ethics. That's all I've heard in this business. Isn't there any humanity left? Aren't there any ethics about letting little babies be murdered?" she yells at him. Bell advises that if she really wants to help the children, she should go back and apologize to Ranger so she can keep working. Lora agrees, but first she stops for a soda and happens to run into the bootlegger and tells him her story. When he hears what Nick did, he offers to talk to a couple of guys to take care of him. Lora learns his name is Mortie and he promises that he's out of the bootlegging business now, but he agrees to help her anyway he can. The bootlegger would be more ethical than the doctors.

seems unconcerned, telling her she has no proof and to make such allegations will just end her career. Lora storms out and goes to see Dr. Bell who, to her surprise, agrees with everything she says but doesn't want to lift a finger to help her either since, even though he's long had suspicions about Ranger, "he is a colleague." Not much has changed in 80 years: Doctors always protect one another no matter how bad they know the other doctor is. Bell tries to put his inability to report Ranger off on "ethics." This really sets Lora off. "Oh, ethic, ethics. That's all I've heard in this business. Isn't there any humanity left? Aren't there any ethics about letting little babies be murdered?" she yells at him. Bell advises that if she really wants to help the children, she should go back and apologize to Ranger so she can keep working. Lora agrees, but first she stops for a soda and happens to run into the bootlegger and tells him her story. When he hears what Nick did, he offers to talk to a couple of guys to take care of him. Lora learns his name is Mortie and he promises that he's out of the bootlegging business now, but he agrees to help her anyway he can. The bootlegger would be more ethical than the doctors.Now, I won't tell you how Night Nurse resolves itself, but it packs so much into its running time that it's damn remarkable it all got squeezed in. Logically, Night Nurse shouldn't be the gem that it is, but lightning struck. Not the type that wins awards but the more important type of electricity — bolts that go off in one time period and continue to reverberate decades later. I do have to share a couple of other favorite moments before I wrap it up though. Wellman put so much effort into this programmer with the different way he set up shots and another of my favorites is the perspective he uses when Mack comes on to Lora again and she lays him out with a punch of her own. It almost looks like 3-D. Then, for comedy, we get to see Mack crawl on the floor to take refuge behind the bar.

Soon after that, Lora tries to physically drag Mrs. Richey so she can see how her daughter is but the drunken women isn't cooperating. Lora even drags her by the throat at one point until Mrs. Richey finally collapses on the floor, passed out. Lora tosses a bucket of ice water on her trying to wake her up to no avail. As she walks away, Lora almost give us some pre-Code profanity as she mutters, "You mothers." The young Stanwyck amazes and this was only her third year making movies and she also scored with another brilliant turn in 1931 in Frank Capra's The Miracle Woman — and so many more and greater performances were still on the way.

Tweet

Labels: 30s, Bette, Blondell, Cagney, Capra, Curtiz, Gable, Harlow, Hecht, Movie Tributes, Oscars, Selznick, Shakespeare, Stanwyck, Wellman

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE