Friday, August 03, 2012

Edward Copeland's Top 100 of 2012 (100-81)

With the release of the latest Sight & Sound poll, conducted every 10 years to determine the all-time best films, The House Next Door blog of Slant Magazine invited some of us not lucky enough to contribute to the S&S list to submit our own Top 10s to The House, which posted mine today. Sight & Sound magazine, a publication of the British Film Institute, began its survey in 1952, using only critics. Its 2002 list boasted its largest sample yet, receiving ballots from 145 film critics, writers and scholars as well as 108 directors. The results can be found here, though a note claims the page isn't actively maintained, though it appears complete to me. Since I planned to revise my personal Top 10, posted as part of my Top 100 in 2007, I figured I owed it to my entire Top 100 to redo my entire list. As before, my rule is simple: A film must be at least 10 years old to appear on my list. Therefore, movies released between 1998 and 2002 might appear on this list whereas they couldn't on the 2007 version. The most difficult part of assembling these lists always involves determining rankings. It's an arbitrary process and once you get past the Top 10 or 20, not only do the placements seem rather meaningless but inclusion and exclusions of films begin to weigh on you. In fact, selecting No. 1 remains easy but if I could, I'd have tied Numbers 2 through 20 or so at No. 2. A lot of great films didn't make this 100 through no fault of their own, falling victim to my whim at the moment I made the decision of what made the cut and where it went. In parentheses after a director's name, you'll find a film's 2007 rank or, if it's new to the list, you'll see NR for not ranked or NE for not eligible. I also should note that this does not mean the return of this blog. I had committed to taking part in The House's feature prior to pulling the plug and completed most of this before signing off.

Part of the arbitrary nature of this list (and from the very first all-time 10-best list I compiled in high school) was to try to make sure I represented my favorite directors while still allowing for those films that might be a more singular achievement. (For example, my first high school list had to be sure to include a Woody Allen, a Huston, a Hitchcock, a Wilder, a Truffaut, an Altman.) The more great cinema you see, the harder it becomes to justify that since lots of directors deserve recognition and many films might be a filmmaker's strongest work. As I've caught up with a lot of Werner Herzog's work over the years, I felt he'd earned inclusion. I was torn between choosing Nosferatu or Aguirre: The Wrath of God to represent him, but opted for the vampire tale because Herzog's "reversioning" of Murnau's silent classic manages to be both a masterpiece of atmospherics and the best version of the Dracula tale put on screen.

Pedro Almodóvar’s career evolution has taken an arc that I imagine few could have anticipated. I know I certainly didn’t back in the 1980s, when his films mainly consisted of camp, color and sexual obsession. Around the time of 1997’s Live Flesh, the Spanish filmmaker’s style took an abrupt change, filtering genres through his unique perspective to exhilarating results that continue through last year’s The Skin I Live In. The greatest of this run of seven features happens to be the most recent film to make this new Top 100 list. Telling the story of two men caring for women they love, both of whom happen to be comatose, Almodóvar’s Oscar-winning screenplay manages to balance humor, pathos and even outlandish touches you’d never expect to make one helluva movie and the writer-director’s best film so far.

Littered along the highways of film history lie multiple tales of adversity breeding triumphs of cinema. As director Jules Dassin faced a possible subpoena from the House Un-American Activities Committee, presumably followed by blacklisting, at the end of the 1940s, producer Darryl Zanuck gave him an exit strategy. Dassin flew to London to hurriedly begin filming an adaptation of the novel Night and the City, which he’d never read, and as a result produced one of the greatest noirs of all time. Not only did he make the movie on the fly, Zanuck even stuck him with creating a role for Gene Tierney, nearly suicidal after a bad love affair. The novel’s author, Gerald Kersh, hated the movie about hustler Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark) scheming to bring Greco-Roman wrestling to London while ducking all sorts of colorful characters played by wonderful actors such as Francis L. Sullivan, Googie Withers, Herbert Lom, Hugh Marlowe and Mike Mazurki. Of course, Kersh’s gripe was understandable — the film bore no resemblance whatsoever to his novel other than the title. However, that didn’t prevent it from being a damn fine film.

It takes a lot to fool me and, in retrospect, I should have seen the final twist coming, but I didn't because Sayles crafted in his best film a compelling story in which the plot turn was unexpected and the movie’s story didn't hinge on it. Even if the secret never had been revealed, this portrait of skeletons from the past and their influence on the lives of people in the present still would resonate. Sayles assembles a helluva ensemble including Chris Cooper, Elizabeth Peña, Matthew McConaughey, Kris Kristofferson, Joe Morton and, in one great single scene, Frances McDormand, to name but a few. Sayles has made some good films since Lone Star, but none come close to equaling the artistry, vitality and humanity of this one. I await another great one from him.

Set piece after set piece, Hitchcock puts Cary Grant through the paces and pulls the viewer along to his most purely entertaining offering. Grant never loses his cool as he's hunted by everyone, James Mason makes a suave bad guy and Martin Landau a perfectly sinister hired thug. With cameos by four former U.S. presidents. There's not much else to say about it: It's not an exercise in style or filled with layers and depth, it's just damn fun. In fact, it’s as much a comedy as a thriller.

There's something to be said for quitting while you're ahead and Charles Laughton, one of the finest screen actors ever, certainly did with the only film he ever directed. The film's influences seem more prevalent than people who have actually seen this disturbing thriller with the great Robert Mitchum as the creepy preacher with love on one hand and hate on the other and the legendary Lillian Gish as the equivalent of the old woman who lived in a shoe, assuming the old woman was well armed.

In describing the film that put Kurosawa on the world’s radar as a major filmmaker, I’m going to let Robert Altman speak for me. This quote comes from his introduction to the Criterion Collection edition of the movie. "Rashomon is the most interesting, for me, of Kurosawa's films.…The main thing here is that when one sees a film you see the characters on screen.…You see very specific things — you see a tree, you see a sword — so one takes that as truth, but in this film, you take it as truth and then you find out it's not necessarily true and you see these various versions of the episode that has taken place that these people are talking about. You're never told which is true and which isn't true which leads you to the proper conclusion that it's all true and none of it's true. It becomes a poem and it cracks this visual thing that we have in our minds that if we see it, it must be a fact. In reading, in radio — where you don't have these specific visuals — your mind is making them up. What my mind makes up and what your mind makes up…is never the same."

For years, my standard response when asked about Raging Bull was that it was a film easier to admire than love. Each time that I’d see the movie again though, that point-of-view became less satisfactory because, as any great film should, the film kept rising higher in my esteem. In the film's opening moments, when Robert De Niro plays the older, fat Jake preparing for his lounge act in 1964 before it cuts to the ripped fighter in 1941, even though I consciously know both versions of La Motta were played by the same actor and that De Niro was that actor, the performance so entrances that I actually ask, "Who is this guy and why hasn't he made more movies?" To gaze at the way he sculpted his body into the shape of a believable middleweight boxer, sweat glistening in Michael Chapman's gorgeous black-and-white cinematography, truly makes an impressive achievement. Acting isn't the proper word for what De Niro does here. He doesn't portray Jake La Motta, he becomes Jake La Motta, or at least the screen version, and leaves all vestiges of Robert De Niro somewhere else. Even when De Niro turns in good or great work in other roles, they never come as close to complete immersion as his La Motta does.

"Out of the worst crime novels I have ever read, Jules Dassin has made the best crime film I've ever seen," François Truffaut wrote about Rififi in his book The Films in My Life. I haven't read the Auguste Le Breton novel, but I don't doubt Truffaut's word. Dassin structures the film like a solid three-act play. Act I: Planning the heist. Act II: Carrying it out. Act III: The aftermath. Dassin fine-tunes each of the film's element to the point that Rififi practically runs as a machine all its own. The various characters behave more as chess pieces to be moved around as the story's game requires than as representatives of people. One single sequence though makes Rififi a landmark both in films and particularly heist movies: the robbery itself. Dassin films this in a 32-minute long silent sequence. No one speaks. Keeping everything as quiet as possible becomes the thieves' No. 1 priority. It's absolutely riveting. You'll be holding your breath as if you were involved in the crime yourself.

Howard Hawks appears for the first time on the list with a Western starring John Wayne that turned out to be so much fun they remade it (more or less) seven years later as El Dorado. I’ll stick with the original where the Duke’s allies include a great Dean Martin as a soused deputy sheriff, young Ricky Nelson and the always wily Walter Brennan. Wayne even gets to romance Angie Dickinson. No deep themes hidden here, though it's more layered than your typical Western. Still, that doesn't mean you can't kick up your spurs and enjoy.

The first time was the charm. One of the few insightful comments I heard on the 2007 AFI special was when Martin Scorsese said that in many ways he finds the primitive stop-motion effects of the original King Kong more impressive than later CGI versions. He's absolutely right. The 1933 version also offers more thrills and emotions (and in half the time) than Peter Jackson's technically superior but dramatically inferior and unnecessary remake. Let’s not even discuss the 1976 version.

When L.A. Confidential debuted on this list in its first year of eligibility in 2007, I wrote, “Of the films of fairly recent vintage, this is one that grows stronger each time I see it, earning comparisons to the great Chinatown…Well acted (even if Kim Basinger's Oscar was beyond generous), well written and well directed, I believe L.A. Confidential’s reputation will only grow greater as the years go on — yet it lost the Oscar (and a spot on the AFI list) to the insipid Titanic.” When I re-watched the film recently, my prediction proved to be spot-on as it only deepens as an experience and an entertainment as time passes. It still boggles my mind that with Russell Crowe, Guy Pearce, Kevin Spacey and James Cromwell (just to name four) delivering impeccable work that only Basinger landed a nomination, but losing best picture and director to James Cameron and Titanic remains the bigger crime.

Simply put: The tensest comedy ever made and perhaps Scorsese's most underrated film. Griffin Dunne plays the perfect beleaguered straight man enveloped by a universe of misfits and oddballs in lower Manhattan when all he wanted to do was get laid. It’s hard to imagine that this movie nearly became a Tim Burton project, but thanks to the many setbacks Scorsese endured attempting to make The Last Temptation of Christ, the film ended up being his — and recharged his batteries as well. While Scorsese has made great films since, I’d love to see him step back sometime and make another indie feature like After Hours on the fly just to see what happens. Joseph Minion wrote an excellent script and this represents one case where I think the changed ending actually proves superior to the originally intended one. By the way, whatever happened to Joseph Minion?

Watchability often gets undervalued when rating a film's worth, but I never tire of sitting through this thrill ride. One aspect that has impressed me since I first saw it as a teen back in 1985 (and I went two nights in a row, dragging my parents to it on the second) was its attention to detail such as Marty arriving in 1955 and mowing down a pine tree on the farm of the deranged man trying to “breed pines.” Then, when he returns to 1985, Twin Pines Mall now bears the sign Lone Pine Mall. It’s just a quiet sight gag in the background without any overt attempt to call attention to the joke. You either catch it or you don’t. I always admire films that respect audiences like that, especially when they happen to be this much fun. With equal touches of satire, suspense and genuine emotion, Back to the Future elicits pure joy. No matter how many times I see it, the final sequence where they prepare to send Marty back to 1985 holds me in rapt attention as I wonder if this time might be the time he doesn't actually make it.

A comedy about the Vietnam War that's full of blood and set in Korea, just as a matter of subterfuge. The film that put Altman on the map and inspired one of TV's best comedies (until it got too full of itself), MASH still holds up with its brilliant ensemble and wicked wit. I still wish the TV show had kept that theme song with its lyrics. Through early morning fog I see/visions of the things to be/the pains that are withheld for me/I realize and I can see.../That suicide is painless/It brings on many changes/and I can take or leave it if I please.

Back in 1985, before Goodfellas and The Sopranos really mixed mob stories with jet black comedy, the great director John Huston, in his second-to-last film, brought to the screen an adaptation of Richard Condon's Mafia satire Prizzi's Honor, complete with great performances and some of the most memorable lines ever collected in a single film. Huston may have been in the twilight of his days, but his filmmaking prowess was as strong as ever. Jack Nicholson disappeared into the role of Charley Partanna more than he had any role in recent memory. Kathleen Turner matched well with Nicholson as Charley's love whose work outside the house causes problems. William Hickey gave an eccentric and indelible portrait of the aging don. Finally, John's daughter Anjelica made up for a misfire of an acting debut decades earlier with her brilliant performance as the scheming Maerose and took home one of the most deserved supporting actress Oscars ever given.

Before Zhang Yimou started being obsessed with spectacle and martial arts, film after film, he produced some of the greatest personal stories in the history of movies, especially when his muse was the great and beautiful Gong Li. This film was their first truly flawless effort as Gong plays the young bride of a powerful lord who already has multiple wives and who encourages the sometimes brutal competition between the women.

"The film actually is like a snail — it kind of turns in on itself and becomes itself," Altman describes his film in an interview on its DVD. One of the many "comebacks" of Robert Altman's career, this brilliant Hollywood satire holds up viewing after viewing because it's so much more than merely a satire. Thanks to Tim Robbins' superb performance as the sympathetic heel of a Hollywood executive and the cynical yet deeper emotional punch of Michael Tolkin's script, Altman wows from the opening eight-minute take to one of the greatest final punchlines in movie history. However, the more times you see it, the more you discover to see. While some specific references have aged, the movie's relevance remains — now more than ever.

Schindler’s List marked an important moment in Spielberg’s development as a filmmaker: Peter Pan finally grew up. It’s a harrowing, well-made movie that everyone should see. At the same time, I can foresee a time when it slips off this list entirely. It isn’t the fault of the film — I find it nearly flawless. However, if someone placed a gun to my head and ordered me to choose to watch either Schindler’s or one of Spielberg’s best post-1993 films such as Catch Me If You Can or Minority Report, I’d opt for one of the latter two. Are they better films than Schindler’s List? I can’t say that. However, the epic holocaust tale isn’t a film you find yourself wanting to pop a bowl of popcorn and watching on a whim. As I said earlier, for me at least, rewatchability remains an important factor. I’ve seen Schindler’s List three times but I haven’t reached the point where I want to go through that wrenching experience again.

Bergman once said that by the time he was done making Wild Strawberries, the film really belonged more to Victor Sjöström, who played Borg, the renowned professor and lauded physician about to receive an honorary degree. The film marked Sjöström 's return from semi-retirement, but he already was a legend as the first true Swedish acting-directing star. Borg decides to drive his old Packard to the event instead of flying to meet his son. The journey becomes more than just a road trip for the professor, but a metaphysical trek through his past as he questions what led him to this moment. As the car winds closer to the ceremony, Borg's inner journey does as well as he comes to realize that for all his scientific training, the only thing he can't analyze is himself. "The day's clear reality dissolves into even clearer remnants of memory," he says. Wild Strawberries represents Bergman growing into his powers as a filmmaker and while it may concern a 78-year-old man examining his life, the subject proves as timeless for people of any age as the film itself.

Tweet

Labels: Almodóvar, Altman, D. Zanuck, Dassin, Hawks, Herzog, Hitchcock, Huston, Ingmar Bergman, Kurosawa, Laughton, Lists, Murnau, Sayles, Scorsese, Spielberg, Tim Burton, Truffaut, Zemeckis, Zhang Yimou

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Edward Copeland's Top 100 of 2012 (60-41)

Perhaps the crowning achievement of the Italian neorealist movement. This story of Italians fighting back against fascism and the Nazis during World War II plays as powerful and moving today as it ever did, with a great cast led by Anna Magnani, who appears in one of the film's most memorable sequences. Despite being generally hard on the film, Manny Farber declared Open City the best film released in the U.S. in 1946 and called Magnani’s performance “the most perfect job by an actress in years and years.”

A breathtaking debut that launched a mostly great film series about Truffaut's screen alter ego, Antoine Doinel, and containing perhaps the most famous freeze frame in film history. It's not bad as a coming-of-age picture either. While The 400 Blows stands alone as the best of the Antoine Doinel films, it’s fascinating to watch Jean-Pierre Leaud play the character from an adolescent to an adult. In its own way, the film resembles the first installment of a fictional version of Michael Apted’s Up documentary series only focusing on a single character.

Pollack didn't just direct and act in this comic masterpiece, he really played tailor as well, stitching together multiple versions of its screenplay to come up with the exquisite finished garment. Dustin Hoffman's brilliant performance as perfectionist pain-in-the-ass actor Michael Dorsey and Dorothy Michaels, the female persona he creates to get work, stands as the crowning achievement of his acting career. It doesn't hurt to be surrounded by an equally solid ensemble that includes Teri Garr, Dabney Coleman, Charles Durning, George Gaynes, Doris Belack, Geena Davis and a nearly all-improvised role by Bill Murray.

Preminger’s crowning achievement could be a routine noirish mystery if it weren’t for its great ensemble of Dana Andrews, Gene Tierney, Judith Anderson, Vincent Price and, most of all, Clifton Webb delivering its wry and witty dialogue by Jay Dratler, Samuel Hoffenstein and Betty Reinhardt (with alleged uncredited contributions from Ring Lardner Jr.). A couple of examples: Price as Laura’s cad of a fiancé Shelby Carpenter declaring ,"I can afford a blemish on my character, but not on my clothes" and Webb as bitchy newspaper columnist Waldo Lydecker describing his work, "I don't use a pen. I write with a goose quill dipped in venom." Laura could be called the All About Eve of film noir mysteries.

Every time I hear that a friend or acquaintance is going to have a baby, I make the same simple request: Do everything in their power to keep all knowledge of this movie away from them until they see it. I would have loved to have seen it without knowing that the shower scene was coming or the truth about Norman Bates. I hope others can have that experience.

One of the biggest jumps of any films from the last list. When revisiting The Last Picture Show for its 40th anniversary last year after having not seen the movie in years, it truly captivated me with its stark beauty. Despite its setting in 1951 in a small Texas town, it contains a universality that resonates today both in human and economic terms. Plot doesn't drive the story — character, not only of the people but of the town itself, does. While you watch the movie, you aren't concerned with what happens next or how the film ends because you realize that life will go on for most of these fictional folks you've come to know. It's telling a coming-of-age story — several in fact — and not all concern the teen characters in the tale. It's also about love and loss, not always in the present tense.

Not only does Broadcast News hold up to repeated viewings, it holds such a special place in my heart that I almost can’t view it rationally. I overidentify with Albert Brooks’ character of Aaron Altman and I’ve known a couple of women with similarities to Holly Hunter’s Jane Craig. More importantly, James L. Brooks wrote and directed a very funny and touching valentine to the decline in television news standards and set it against an unrequited love triangle (with William Hurt’s Tom Grunick filling the third point as well as representing TV news’s deterioration). The supporting cast also aids the entertaining proceedings with the likes of Robert Prosky, Joan Cusack, Lois Chiles, Peter Hackes, Christian Clemenson and Jack Nicholson as the anchor of the network’s evening news.

Even people who view Capra as a sentimental sap tend to like this great madcap romantic romp thanks to the great chemistry of Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert. The first film to sweep the top five categories at the Oscar continues to hold up thanks in no small part to the chemistry between Gable and Colbert. Memorable scenes pile up one after another involving great character actors such as Roscoe Karns and Alan Hale Sr. Perhaps the most magical scene comes when Colbert’s Ellie asks Gable’s Peter if he's ever been in love while on opposite sides of the blanket and he momentarily gets serious, wistfully describing his ideal woman while Ellie slowly melts on the other side of the blanket. May the walls of Jericho always fall.

Here comes Hitch again with his most personal and, in many ways, disturbing film about love and obsession and the need to replace what one has lost. It also happens to be another of my great moviegoing experiences, having been able to see the 1996 restoration at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York. Robert Burks’ cinematography never came across as vividly, especially the reds in the scenes set at Ernie’s. James Stewart delivered one of his best performances as a former cop, already damaged psychologically, pushed further to the edge when he falls for a woman named Madeline (Kim Novak) that he’s been hired to follow and later when he meets her doppelganger and attempts to make her over in Madeline’s image.

As the years roll by, many find themselves less enthused by Tarantino's film. I am not among their ranks, finding that I'm as enthralled, entertained and as giddy as I was the first time I saw it whenever I see any part of it again. Similarly, my faith in Quentin remains strong as well, especially in the wake of Inglourious Basterds, which I definitely could see on a list like this once it reaches its eligibility if it holds up as well as it has so far.

Billy Wilder made so many great comedies with varying levels of pathos that it's hard to pick just one. I considered Some Like It Hot and One, Two Three, but this one remains for me his best film among the ones played primarily for laughs. In the wake of Mad Men, the film proves particularly interesting to watch (even if Roger Sterling thinks female elevator operators defy reality).

Even before the recent passing of Andy Griffith, I had decided that I had to make a spot for A Face in the Crowd on this list. As far as I’m concerned, it undoubtedly stands as Kazan’s best film and as a bit of a prescient one. Without this film, I’m not sure Paddy Chayefsky would have been inspired nearly 20 years later to write Network. Budd Schulberg deserves the bulk of the credit, adapting A Face in the Crowd from a short story he wrote called “Arkansas Traveler.” The film broke ground in its depiction of the convergence and intermingling of the media, corporate and political worlds. In addition to Griffith’s stellar performance as Lonesome Rhodes, the cast includes exemplary work from Patricia Neal, Walter Matthau and Tony Franciosa. Mike Wallace, John Cameron Swayze and Walter Winchell even make cameos as themselves. The film’s reputation should only grow.

When one of the early moments of a movie shows Edward Norton squeezed against the man breasts of a sobbing Meat Loaf, it boggles my mind how many people who saw Fight Club when it came out didn’t immediately recognize the film as a satire. Every time I’ve watched this film, I’ve loved it more than I did originally. To further emphasize its strength, the first time I saw it, I already knew the twist because of an out-of-nowhere comment by David Thomson in a completely unrelated article in The New York Times. Based on Chuck Palahniuk’s novel, Jim Uhl’s screenplay and David Fincher’s direction spin a funhouse tour of the consumer culture, self-help groups and machismo. Norton turns in a great performance as always as do Brad Pitt as the devil on his shoulder and Helena Bonham-Carter as a twisted kindred spirit.

A running gag between Wagstaff and I in recent years is that I believe Die Hard is the greatest film ever made. OK, I don't really believe that, but this is one of the best, especially as far as action goes and Alan Rickman remains one of the all-time great movie villains. In addition to having a great bad guy, what sets Die Hard apart from other action films is that its hero, John McClane (Bruce Willis) isn't superhuman. By the end of the movie, he looks as if he's been through hell.

This film doesn't get mentioned as often as it should, but its portrait of the perils of vigilante justice comes through as strongly today as I imagine it did when it was originally released. Henry Fonda and Harry Morgan try to speak for calm and rationality against the horde ready to inflict mob violence.

The time is over for the debate as to whether the Oscar this classic silent won in the Academy's first year was the equivalent of "best picture." All that needs to be said is that is a great film, Academy seal of approval or not. It remains both heartbreaking and beautiful 85 years after its debut.

The Godfather Part II may have won best picture in 1974, but for my money it wasn't even the best Coppola film that year, let alone the best picture (not that it isn't good). This simple tale of an eavesdropping expert (Gene Hackman giving one of his best, most restrained performances) experiencing sudden moral qualms remains riveting and thoughtful to this day.

Supposedly, Hitchcock often named this gem as his personal favorite of his films and it certainly remains one of his best with its dry, mordant wit and a great lead in Joseph Cotten as Uncle Charlie, worshipped by Teresa Wright as his niece Charlie. Much comic relief gets provided by Henry Travers as young Charlie's father and Hume Cronyn as his murder mystery-loving friend.

I'm not talking to you Travis, but about you, and Scorsese and Paul Schrader's dark, modern spin on The Searchers only grows more stunning as the years roll on. Robert De Niro gives one of his greatest performances and, for my money, this may remain Jodie Foster's finest work.

Jean Renoir made a lot of great films and at least two unquestionable masterpieces, including this one, yet you seldom hear his name come up unless you are talking with real cinephiles. Shameful — because his films don't belong to elite tastes: They belong to everyone. This vivid portrait of WWI prisoners of war proves that since it was the very first time the Academy bothered to nominate a foreign language film for best picture. It should have won too.

Tweet

Labels: Bogdanovich, Capra, Chayefsky, Coppola, Fincher, Hitchcock, Kazan, Lists, Murnau, Preminger, Renoir, Scorsese, Sydney Pollack, Tarantino, Truffaut, Wellman

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Edward Copeland's Top 100 of 2012 (20-1)

Charlie Chaplin was audacious enough to continue making silent films (although he did allow for sound effects and an occasional song) all the way to 1936. In my opinion, he saved the Little Tramp's best for last in this hysterical tale of man vs. the modern age. The comedy is as funny as you'd expect and even more pointed than usual. Since Chaplin knew the Little Tramp was making his swan song, he even let him waddle off into the sunrise. Sound didn't stop Chaplin, who had two great sound efforts to come with The Great Dictator and Monsieur Verdoux. Still, his early works are the most precious gifts. Truly, his silence was golden.

When compiling the 2007 list, I feared it was becoming too Hitchcock-centric, forcing the omission of other great filmmakers but dammit, he made so many films that mean so much to me, it would be dishonest to place a quota on him. In the intervening five years, seeing Strangers several more times only has lifted it in my extreme. Hitch's directing gifts come off at his most stylish and Robert Walker's wondrous performance as the sensitive sociopath Bruno who expects the wimpy Farley Granger to live up to his part of a hypothetical murder deal remains chilling (and darkly funny) to this day. One of the biggest leaps from the last list.

Buster Keaton always shares the title with Charlie Chaplin as one of the two great silent clowns and The General continues to be Keaton’s masterpiece 85 years later. However, while it doesn’t lack for laughs, the film more accurately could be called an adventure than a comedy. The realism of the film’s Civil War setting also proves quite striking and even though Keaton’s character Johnny Gray fights for the Confederacy against the Union, neither side comes off as particularly villainous and the film doesn’t contain the racist elements of something like Birth of a Nation. The film’s humor stems from Johnny’s two loves: his train and the woman he longs for who won’t love him until he joins the war effort, even though he’s been rejected as a fighter because of his skills as an engineer. The General never grows old.

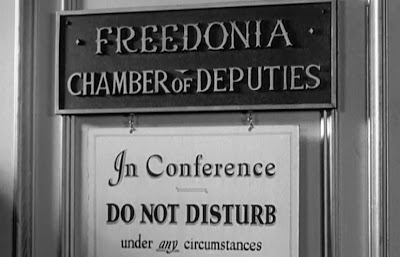

When Mickey (Woody Allen), depressed and suicidal, wanders into a movie theater in Hannah and Her Sisters, it's this inspired mixture of lunacy that brings him back around. After all, who can sit through Duck Soup and not feel better afterward. The question as to which Marx Brothers vehicle was the best got settled a long time ago and Duck Soup won. With its classic mirror scene and the loosest of plots designed to make the insanity of war look even crazier, I never get tired of Duck Soup. Watch it if only for the great Margaret Dumont. Remember, you are fighting for her honor, which is more than she ever did.

As a journalist, His Girl Friday contains one of my favorite nonsequiturs in the history of film. Delivered with frantic panache by Cary Grant as unscrupulous newspaper editor Walter Burns: "Leave the rooster story alone. That's human interest." Oh yeah, this may also be one of the funniest films ever made with rapid fire dialogue, a great sparring partner for Grant in Rosalind Russell and a priceless supporting cast to boot. It's the best remake ever made (and the film it was based on, The Front Page, is pretty damn good too). Making Hildy Johnson a woman and Burns' ex-wife was a stroke of genius. Besides, when you watch any version of this story where Walter and Hildy are both men, it's clear this isn't a platonic working relationship. I don't advise any more remakes (forget Switching Channels, if you can), but I wonder how it would play if the leads were two gay men?

As I wrote when marking the 100th anniversary of Reed's birth (forgive my self-plagiarism, but it makes this enterprise go faster), "Rewatching The Third Man recently, it once again captivated me from the moment the great zither music by Anton Karas begins to play over the credits.…If you haven't seen The Third Man (and shame on you if you call yourself a film buff and you haven't), watching the Criterion DVD really is the way to go, not only for a crisp print but to be able to compare the different versions offered for British and U.S. audiences (though only the different openings are included — we don't see what 17 minutes David Selznick cut for American audiences). With its great scenes of Vienna, sly performances and perhaps the greatest entrance of any character in movie history, The Third Man stays near the top of all films ever made, even nearly 60 years after its release."

I don’t know what I was thinking ranking Seven Samurai so low on my 2007 list. Having seen it a couple more times since, I’ve rectified that error. All films this long should hold their length as well as this rollicking adventure does. Each time I see it, it transfixes me from beginning to end. Hacks like Michael Bay should look to a film such as Seven Samurai and discover how characters trump stunts, explosions and special effects in great action-adventure films. It's amazing that with such a large cast, not just of the title samurai but of the farmers they defend as well, the actors and Kurosawa develop so many distinct and worthy portraits. Granted, the running time helps, but they establish characters rather quickly from Takashi Shimura (unrecognizable from his role as the dying bureaucrat in Ikiru) as the lead samurai organizing the mission to the brilliant Toshiro Mifune as Kikuchiyo, a reckless samurai haunted by his past as a farmer's son. Full of action, humor, sadness, a bit of romance and plenty of heart, its influence on so many films that have come since can’t be calculated.

Currently, we live in a time of a vicious circle: Movies inspire theatrical musicals which in turn become movie musicals (or in most cases, don't. Don't be looking for Leap of Faith: The Musical on the big screen anytime soon). Still, there was a time when musicals were created as motion pictures. Singin' in the Rain remains the very best example of one of those. The songs soar, the dance numbers inspire and the performances evoke joy. On top of that, it's even a Hollywood story, set in the awkward time between silent film and sound and milking plenty of laughs from the situation, especially through the spectacular performance of Jean Hagen as a silent superstar with a voice hardly made for sound and a personality barely suitable for Earth. Gene Kelly gives his best performance, a young Debbie Reynolds shines and Donald O'Connor makes us all laugh. Decades later, Singin' in the Rain got transformed (if that's the right word) a Broadway stage version. It wasn't very good. Stick with the movie.

When I wrote about this film for the Screenwriting Blog-a-Thon hosted by Mystery Man on Film in 2007, I said, "As far as I'm concerned, this film is Allen's masterpiece. Others will cite Annie Hall or Manhattan or some other titles and while I love Annie Hall and many others well, over time The Purple Rose of Cairo is the Allen screenplay that has reserved the fondest place in my heart. The screenplay isn't saddled with any extraneous scenes and no sequence falls flat as it builds toward its bittersweet ending. For me, it's Woody Allen's greatest screenplay and one of the best ever written as well." I've been pleasantly surprised at the number of people who have said to me since I wrote that how they agree, even among moviegoers who declare themselves not to like Woody Allen as a rule. It's the perfect blend of comedy, fantasy and realism and one of the greatest depictions of the magic of movies ever put on film. In The Purple Rose of Cairo, when Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels) and his pith helmet step off the screen, the repercussions end up being both hilarious, touching and painfully real.

While for me Jules and Jim stands as the high watermark of the French New Wave films, when you look objectively at the story of Jules and Jim, it may employ many of that movement's techniques but many aspects of Truffaut's film set it apart from its cinematic brethren such as its period setting and a time span that covers more than two decades separates it from the movement as well. However, that doesn’t affect the film’s magnificence. In a funny way, the 1962 film forecast the free love movement to come later that decade except its source material happened to be a semiautobiographical novel set in the early part of the 20th century. The prurience though lies in the mind of the fuddy duddy because part of what makes Jules and Jim so special comes from Truffaut's refusal to pass any judgment, be it positive or negative, upon the behavior of his characters. Despite the director's own criticism many years down the road that the film isn't cruel enough when it comes to love, the three main characters do suffer by the end but he doesn't paint it as punishment for their sins. In a 1977 interview, Truffaut said he thought he was "too young" when he made Jules and Jim. If he'd made it at any other age, it wouldn't be the same movie and probably wouldn't hold the same appeal for so many. For Jules and Jim to grab you, really grab you, I think you need to be young when you see it the first time, and that's why Truffaut, not yet 30 but captivated by the novel since 25, had to be young as well.

Wilder’s screenplay with Charles Brackett and D.M. Marshman Jr. proves surprisingly malleable, never fitting easily into one genre and playing differently in each viewing. It can be the darkest of Hollywood satires or the tragedy of a woman driven insane by a world that’s passed her by. Gloria Swanson’s brilliant performance as Norma Desmond can come off as a vulnerable madwoman or a master manipulator. Similarly, William Holden’s down-on-his-luck screenwriter Joe Gillis looks like a shallow opportunist in some scenes, an in-over-his-head dupe in others. The layers make Sunset Blvd. fresh and endlessly watchable. Wilder and his co-writers always produced great dialogue, but I believe Sunset Blvd. stands as Wilder’s greatest work as a director as well.

Hitchcock blessed us with so many classics, it’s hard to pick the best. This list contains seven Hitchcocks, but Rear Window stands tallest to me. I’ll allow two great directors to state my case. First, François Truffaut from The Films in My Life: “Rear Window is…a film about the impossibility of happiness, about dirty linen that gets washed in the courtyard; a film about moral solitude, an extraordinary symphony of daily life and ruined dreams." From David Lynch, as he wrote in Catching the Big Fish: “It's magical and everybody who sees it feels that. It's so nice to go back and visit that place." David, I couldn’t agree more.

Goodfellas rarely gets selected as the premier example of Scorsese’s brilliance as a filmmaker — and that’s a damn shame because, within its two hour and 20 minute running time, Goodfellas not only encapsulates Scorsese and filmmaking at their best but might be the director’s most personal film. If you wanted to demonstrate practically any aspect of moviemaking to a novice — editing, tracking shots, reverse pans, effective use of popular music — Scorsese disguised a film school in the form of this feature film about low-level gangsters. Goodfellas also happens to be the director’s most re-watchable film and, in a career stocked with masterpieces, it remains my favorite.

Every time I return to Paddy Chayefsky’s prescient screenplay, something new leaps out that I didn’t catch before. Most recently, it’s from one of Howard Beale’s monologues once he’s become the UBS network’s star. As part of the speech, delivered by the late, great Peter Finch, Beale tells his viewers, “Because you people, and 62 million other Americans, are listening to me right now. Because less than three percent of you people read books! Because less than 15 percent of you read newspapers!” Chayefsky died long before the Web revolution so remember that the next time someone blames the newspaper industry's death on the Internet. Better yet, watch Network and revel in the delicious words, magnificent ensemble and Lumet’s fine direction.

Many prefer the Kubrick of 2001: a Space Odyssey or later works such as A Clockwork Orange or Barry Lyndon, but I’ve always found him best when satirical, especially when that sharp humor took aim at the futility of war as in the underrated Full Metal Jacket, the great Paths of Glory and the best of the bunch, the incomparable Dr. Strangelove. To take the prospect of nuclear apocalypse instigated by a general driven mad by his impotence and produce one of the wall-to-wall funniest films ever was no small achievement, but having Peter Sellers in his multiple roles, Sterling Hayden and, most of all, George C. Scott’s hyperbolic, acrobatic and energetic work as Gen. Buck Turgidson, sure helped. That's not to mention Slim Pickens and Keenan Wynn as well and the surreal beauty of that closing of multiple mushroom clouds backed by that wonderfully ironic song.

So rarely does the best picture Oscar go to the best film, it always amazes me that the Academy recognized Casablanca (though for 1943, since it didn’t open in L.A. until a few months after its New York premiere). Claude Rains’ irreplaceable Captain Renault may say, “The Germans have outlawed miracles,” but the most miraculous thing of all was that a screenplay without an ending and based on an unproduced play managed to coalesce into the finest movie the Hollywood studio system ever produced. With a superb ensemble of character actors and stars delivering dialogue with more memorable lines than nearly any other film ever, courtesy of screenwriters Julius J. & Philip G. Epstein and Howard Koch, play it forever, Sam.

It does worry me that we seem to lack a filmmaker as ballsy as Robert Altman was (first person to suggest Paul Thomas Anderson gets punched in the face). Thankfully, he left us his body of work (some dogs to be certain, but the ecstasies we receive from his great ones allow us to forgive). For me, Nashville never wavers from its spot at the top of the Altman charts. It’s a musical, but not really. It’s about politics, but not really. We get to watch 24 characters intersect (or not) as Altman and screenwriter Joan Tewksbury design a tapestry displaying a picture of America on the eve of its bicentennial. It also presents ideas that in their own way prove as prescient as those in Network.

Many of the greatest films turn out to be examples of triumph over adversity and that certainly proved to be the case with Children of Paradise, Carné’s two-part masterpiece made during the Nazi occupation of France. When I wrote at length about this deceptively simple tale of mimes and actors, criminals and the aristocracy, I said that if I revised my 2007 list, the film likely would rise higher than its 18th rank. As you see, it most definitely has. Better to experience its beauty and magic than attempt to briefly describe it.

One wonders what the total would be if we calculated the number of words written extolling the brilliance and significance of Orson Welles’ filmmaking debut. Granted, the curmudgeons and contrarians exist and while not a day goes by that I don’t remind someone that all opinions are subjective by definition, Citizen Kane looms as the behemoth that practically defies that statement. Its status as a cinematic masterpiece comes close to being an objective truth. I have nothing new to add about this wonder. The film speaks for itself.

After what I wrote about Citizen Kane, you’d think it would rest in my top spot, but Renoir’s exquisite tragicomedy grabbed a foothold in my Top 10 as soon as I saw it in college and it took only one or two more viewings for Rules to clinch the No. 1 perch where it’s remained for more than two decades. Something personal within the film (too much identification with Renoir’s character of Octave; the character of Christine, who seems to cast a spell over all men who cross her path) hooks me in above and beyond the film’s artistry. If that explanation seems skimpy, I defer to what Octave says, "The awful thing about life is this: Everybody has their reasons."

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Carné, Carol Reed, Chaplin, Curtiz, Gene Kelly, Hawks, Hitchcock, Keaton, Kubrick, Kurosawa, Lists, Lumet, Renoir, Scorsese, Truffaut, Welles, Wilder, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, April 30, 2012

A vision for all — perhaps not meant for one man alone

"I was most jealous of Truffaut — in a friendly way — with Jules and Jim. I said, 'It's so good! How I wish I'd made it.' Certain scenes had me dying of jealousy. I said, 'I should've done that, not him.'" — Jean Renoir

By Edward Copeland

From the first time I saw Jules and Jim in high school, the movie became a personal touchstone and remains one as we mark its 50th anniversary. Truthfully, I know the parallels my teen eyes recognized between myself and others in my life then didn't mirror the characters on screen as closely as my imagination wanted to believe, but as that fantasy faded away, I began to appreciate more of the artistry of a film that I already loved. In addition to what Jules and Jim contains within its frames, the movie also forged the connection I've always felt with François Truffaut.

If you discovered, probably early in your life, that your genetic makeup left you susceptible to artistic impulses of some kind — it needn't matter whether that creative bent took the form of movies, writing, art, music, whatever — the odds weighed heavily toward you falling for at least one Catherine in your lifetime. (Now, I'm speaking from the point-of-view of a straight male. I wouldn't dare presume straight female or gay perspectives, though I've witnessed similar dynamics secondhand.) As far as we go, the Catherines of the real world function like those purple-hued bug zappers hanging on summer porches and inevitably drawing us like moths to their pulsating light and our doom — and we wouldn't trade one goddamn miserable minute of it if it meant losing a single second of the joy. This isn't a new phenomenon:

F. Scott had his Zelda and Tom had his Viv during the same era when Jules and Jim takes place. (A brief aside: I think Tom sent me a personal message from the past when he published The Waste Land in 1922 and penned those lines, "April is the cruellest month.") To casual and outside observers, proclaiming that Catherine must be crazy comes rather easily and mounting a counterargument against that assumption makes for a steep climb. Yes, our real world Catherines come with a fair amount of mental instability, as do we, but without our neuroses and idiosyncrasies, we probably wouldn't be drawn to these wild, wonderful, wounding women in the first place. Of course, Henri-Pierre Roché's novel and François Truffaut's film take the men's point-of-view, even when filtered through Michel Sobor's narration, so Jules and Jim aren't portrayed as being as unstable as Catherine. The closest the male friends come shows through Jules' fear and neediness at times. As for the Catherines of the real world, people do have the capacity for change, no matter what David Chase might believe, and can end up being vital parts of your life even as you become the one holding the monopoly on the madness in the friendship. It's a cliché, but it originates from truth: Most of the best art stems from suffering. Anyone remember Billy Joel during the years when he and Christie Brinkley were happily married? Jules and Jim, for me at least, represents a cinematic temple to that idea. Of course, it also begs the question that if misery breeds great art, why in the hell haven't I accomplished something of note?

F. Scott had his Zelda and Tom had his Viv during the same era when Jules and Jim takes place. (A brief aside: I think Tom sent me a personal message from the past when he published The Waste Land in 1922 and penned those lines, "April is the cruellest month.") To casual and outside observers, proclaiming that Catherine must be crazy comes rather easily and mounting a counterargument against that assumption makes for a steep climb. Yes, our real world Catherines come with a fair amount of mental instability, as do we, but without our neuroses and idiosyncrasies, we probably wouldn't be drawn to these wild, wonderful, wounding women in the first place. Of course, Henri-Pierre Roché's novel and François Truffaut's film take the men's point-of-view, even when filtered through Michel Sobor's narration, so Jules and Jim aren't portrayed as being as unstable as Catherine. The closest the male friends come shows through Jules' fear and neediness at times. As for the Catherines of the real world, people do have the capacity for change, no matter what David Chase might believe, and can end up being vital parts of your life even as you become the one holding the monopoly on the madness in the friendship. It's a cliché, but it originates from truth: Most of the best art stems from suffering. Anyone remember Billy Joel during the years when he and Christie Brinkley were happily married? Jules and Jim, for me at least, represents a cinematic temple to that idea. Of course, it also begs the question that if misery breeds great art, why in the hell haven't I accomplished something of note? Jules and Jim made its U.S. premiere April 23, 1962, the same year the film made its initial debut in France on Jan. 23. Though it marked Truffaut's third feature film as a director following The 400 Blows and Shoot the Piano Player, Jules and Jim was only the second of his films to reach U.S. movie theaters. Shoot the Piano Player, though it opened elsewhere in 1960, wouldn't get its U.S. release until July 23, 1962. (Like Jules and Jim, The 400 Blows reached U.S. shores in the same year, 1959, that Truffaut's directing

debut did elsewhere, just a few months later.) As I remind people as often as possible, all opinions about movies are subjective. Before beginning my lovesick tribute to what I think holds the title as the true masterpiece born of the French New Wave, I feel that I shouldn't pretend all critics agreed about Jules and Jim and I'd allow one to have his say before I got started. "With the years, I've sometimes felt the reputation of Jules and Jim is a bit exaggerated," this former critic said to Richard Roud, then-director of the New York Film Festival, in October 1977 on a television program called Camera Three. The ex-critic added, "and that I was too young when I made it." That appearance happened to be François Truffaut's first time on American television. I guess you can remove the man from the role of film critic but you can't take the critic out of the man. "I continue to re-read the book every year. It was one of my favorites. I've often felt that the film was too decorative, not cruel enough, that love was crueler that that," Truffaut went on to tell Roud. Now, François, don't be so hard on yourself. For those who haven't seen Jules and Jim, I'll be vague, I think you could call the film's dénouement fairly devastating. Besides, most recognize (or know from experience) that cruelty usually crosses love's path at some point. On top of that, the subject cuts too close to Truffaut for him to judge. Jules and Jim may speak to me in personal ways, but that isn't why the film rests among my 20 favorite films of all time. As John Houseman used to claim in TV commercials about how Smith Barney made money, Jules and Jim got that rank on my list "the old-fashioned way. It earned it."

debut did elsewhere, just a few months later.) As I remind people as often as possible, all opinions about movies are subjective. Before beginning my lovesick tribute to what I think holds the title as the true masterpiece born of the French New Wave, I feel that I shouldn't pretend all critics agreed about Jules and Jim and I'd allow one to have his say before I got started. "With the years, I've sometimes felt the reputation of Jules and Jim is a bit exaggerated," this former critic said to Richard Roud, then-director of the New York Film Festival, in October 1977 on a television program called Camera Three. The ex-critic added, "and that I was too young when I made it." That appearance happened to be François Truffaut's first time on American television. I guess you can remove the man from the role of film critic but you can't take the critic out of the man. "I continue to re-read the book every year. It was one of my favorites. I've often felt that the film was too decorative, not cruel enough, that love was crueler that that," Truffaut went on to tell Roud. Now, François, don't be so hard on yourself. For those who haven't seen Jules and Jim, I'll be vague, I think you could call the film's dénouement fairly devastating. Besides, most recognize (or know from experience) that cruelty usually crosses love's path at some point. On top of that, the subject cuts too close to Truffaut for him to judge. Jules and Jim may speak to me in personal ways, but that isn't why the film rests among my 20 favorite films of all time. As John Houseman used to claim in TV commercials about how Smith Barney made money, Jules and Jim got that rank on my list "the old-fashioned way. It earned it."While I knew that Jules and Jim originated as a novel by Henri-Pierre Roché, it wasn't until I obtained the Criterion edition that I learned that Roché loosely based it on his relationship with Franz Hessel, a German writer who translated Proust into German (as Jim does in the film) and Helen Grund, who became Hessel's wife and herself translated Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita into German. Legend has it that Roché also introduced Gertrude Stein to Pablo Picasso through his original career as an art dealer and art collector. Though the circles that Roché circulated in preceded the time period of Woody Allen's recent Midnight in Paris, he did know many of the literary and artistic figures depicted in Allen's fantasy. The real-life coincidences that brought Truffaut and Roché together border on the extraordinary. Truffaut

stumbled upon the novel in a secondhand bookstore and it led to a letter-writing relationship between himself and Roché where the young critic Truffaut promised that if he ever made movies, he would bring Jules and Jim to the screen. Jules and Jim was the first novel that Roché ever wrote — which he did at the age of 74. His second novel, also autobiographical, Two English Girls and the Continent, eventually became the source material of a later Truffaut film, Two English Girls. Two English Girls, sort of the inverse of Jules and Jim with two women pining for the same man, marks its 40th anniversary this year but unfortunately, like too many other great films I'd like to write about this year, no proper DVD copy has been made for rental or at a reasonable price, the same situation that in the past two years has befallen other films such as Steven Soderbergh's Kafka, Barbet Schroeder's Barfly with its great performances by Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway and two of John Sayles' very best films — City of Hope and Matewan. Who said only old classics become lost films? With the constant format changes, some never made the leap from pan-and-scanned VHS. A true travesty, but I've digressed from the subject at hand. Roché didn't live long enough to see the movie of his first novel, but the film version brought best-seller status to his book that it never saw in his lifetime. One aspect that didn't occur to me until I re-watched the movie for this tribute: Not only has the film reached its 50th anniversary this year, 2012 also means a full century has passed from where its story begins in 1912.

stumbled upon the novel in a secondhand bookstore and it led to a letter-writing relationship between himself and Roché where the young critic Truffaut promised that if he ever made movies, he would bring Jules and Jim to the screen. Jules and Jim was the first novel that Roché ever wrote — which he did at the age of 74. His second novel, also autobiographical, Two English Girls and the Continent, eventually became the source material of a later Truffaut film, Two English Girls. Two English Girls, sort of the inverse of Jules and Jim with two women pining for the same man, marks its 40th anniversary this year but unfortunately, like too many other great films I'd like to write about this year, no proper DVD copy has been made for rental or at a reasonable price, the same situation that in the past two years has befallen other films such as Steven Soderbergh's Kafka, Barbet Schroeder's Barfly with its great performances by Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway and two of John Sayles' very best films — City of Hope and Matewan. Who said only old classics become lost films? With the constant format changes, some never made the leap from pan-and-scanned VHS. A true travesty, but I've digressed from the subject at hand. Roché didn't live long enough to see the movie of his first novel, but the film version brought best-seller status to his book that it never saw in his lifetime. One aspect that didn't occur to me until I re-watched the movie for this tribute: Not only has the film reached its 50th anniversary this year, 2012 also means a full century has passed from where its story begins in 1912.

The film starts in blackness — literally if you were in a French-speaking country or watching without subtitles. You hear a voice (Jeanne Moreau's as Catherine, though we wouldn't know that yet) say, "You said, 'I love you.' I said, 'Wait.' I was about to say, 'Take me.' You said, 'Go.'" Then, quite abruptly, Truffaut launches us into the film's imagery with a bouncy spirit, playing music beneath the credits that seems to herald that a carnival lies ahead courtesy of prolific film composer Georges Delerue, who scores the entire film, though it won't all sound like this energetic romp which accompanies clips, some of scenes that will arrive later in the film, others that just fit the tone of the piece — such as Jules and Jim jokingly fencing with brooms. As with many others, Delerue would collaborate with Truffaut on nearly all of his films, having first worked on Shoot the Piano Player. We'll also get a glimpse of an hourglass, its sand pouring through to clue us in advance of the importance the passage of time serves in the story. We see our first swift sightings of Moreau as Catherine, though her actual entrance

into the film doesn't occur immediately. While Catherine certainly acts as the catalyst for most events in Jules and Jim, her name isn't in the title for a reason. At its heart, Jules and Jim spins a story of friendship between two men. Oskar Werner's Jules acts as the outsider, the Austrian in Paris, until Henri Serre's Jim takes him beneath his wing, acting, quite literally, in the early days of their acquaintance as Jules' wingman. As with many Truffaut films, Jules and Jim employs a narrator (Michel Subor) not only to for exposition purposes but because Truffaut wanted to maintain as much of Roché's prose as possible in the adaptation he co-wrote with Jean Gruault. Jules and Jim's friendship begins when Jules, the foreigner in Paris, approaches Jim blindly to see if the Frenchman might wrangle him an invitation to the Quatres Arts Ball. Jim succeeds and a friendship blossoms as they search for a slave costume for Jules to wear to the event. From that, the men began to teach one another the other's language and culture and shared their poems,

into the film doesn't occur immediately. While Catherine certainly acts as the catalyst for most events in Jules and Jim, her name isn't in the title for a reason. At its heart, Jules and Jim spins a story of friendship between two men. Oskar Werner's Jules acts as the outsider, the Austrian in Paris, until Henri Serre's Jim takes him beneath his wing, acting, quite literally, in the early days of their acquaintance as Jules' wingman. As with many Truffaut films, Jules and Jim employs a narrator (Michel Subor) not only to for exposition purposes but because Truffaut wanted to maintain as much of Roché's prose as possible in the adaptation he co-wrote with Jean Gruault. Jules and Jim's friendship begins when Jules, the foreigner in Paris, approaches Jim blindly to see if the Frenchman might wrangle him an invitation to the Quatres Arts Ball. Jim succeeds and a friendship blossoms as they search for a slave costume for Jules to wear to the event. From that, the men began to teach one another the other's language and culture and shared their poems, which they'd translate into the other's native tongue. Before long, the men saw each other every day, talking endlessly, finding common ground such as, the narrator informs us, "a relative indifference toward money." The omniscient voice also tells the viewer, "They chatted easily. Neither had ever had such an attentive listener." Jules though lacks luck when it comes to love in Paris, even of the transitory kind while Jim draws women to him as if he were a magnet. Jim finds getting women so easy that he willingly hands some off to Jules, including a musician. "They were in love for about a week." This early setup runs us through the women, most of whom bear little importance to the story so they receive scant attention from the film. Desperate for some amorous action, Jules even ignores Jim's warning to stay away from the "professionals" only to learn that he should have trusted Jim's word and avoided the disappointment. This changes one evening, when the men encounter a woman named Thérèse (Marie Dubois) seeking refuge from her loutish anarchist boyfriend who blames her for a shortage of paint that he thinks will make people believe that anarchists don't know how to spell.

which they'd translate into the other's native tongue. Before long, the men saw each other every day, talking endlessly, finding common ground such as, the narrator informs us, "a relative indifference toward money." The omniscient voice also tells the viewer, "They chatted easily. Neither had ever had such an attentive listener." Jules though lacks luck when it comes to love in Paris, even of the transitory kind while Jim draws women to him as if he were a magnet. Jim finds getting women so easy that he willingly hands some off to Jules, including a musician. "They were in love for about a week." This early setup runs us through the women, most of whom bear little importance to the story so they receive scant attention from the film. Desperate for some amorous action, Jules even ignores Jim's warning to stay away from the "professionals" only to learn that he should have trusted Jim's word and avoided the disappointment. This changes one evening, when the men encounter a woman named Thérèse (Marie Dubois) seeking refuge from her loutish anarchist boyfriend who blames her for a shortage of paint that he thinks will make people believe that anarchists don't know how to spell.

What separates Jules' and Jim's relationship with Thérèse from what lies ahead with Catherine comes from Thérèse clearly indicating a preference between the two men, in this case Jules. Though Dubois' role takes up very little screen time, she does prove a charmer (and remember that U.S. moviegoers, at the time of Jules and Jim's release, had yet to see her film debut as the waitress Lena in love with Charles Aznavour's piano-playing Charlie in Truffaut's second feature, Shoot the Piano Player). When they return to the house,

Jules acts the part of the gentleman, offering Thérèse his bed while he sleeps in a rocking chair, but romance occurs quickly and rectifies that situation. That hourglass first spotted in the opening credits reappears and Jules explains that he prefers it to a clock. When all the sand passes through to the bottom, that means it's time to go to sleep, he explains. She simply smiles and tells him he's sweet. Thérèse demonstrates for Jules her trick that she calls "the steam engine." She places a lit cigarette in her mouth and puffs out her cheeks like a blowfish and then chugs in a circle in the bedroom until she has reached Jules' chair, one of the many, recurrent visuals of circular imagery that Truffaut utilizes in the film. You shouldn't feel bad for Jim — he's busy bedding his frequent lover Gilberte (Vanna Urbino) and making excuses to depart her bed before the sun rises despite her request to lie beside her for a complete night for a change. Jim nixes that idea, saying that if they did that they might as well be married and she'd expect him to stay the next night as well. Gilberte expresses skepticism at his excuse, especially when he suggests that she imagine he's working at a factory, betting that his plan involves sleeping until noon. Later that night, Jules, Jim and Thérèse go to a café and no sooner have they sat down that after making eyes at another

Jules acts the part of the gentleman, offering Thérèse his bed while he sleeps in a rocking chair, but romance occurs quickly and rectifies that situation. That hourglass first spotted in the opening credits reappears and Jules explains that he prefers it to a clock. When all the sand passes through to the bottom, that means it's time to go to sleep, he explains. She simply smiles and tells him he's sweet. Thérèse demonstrates for Jules her trick that she calls "the steam engine." She places a lit cigarette in her mouth and puffs out her cheeks like a blowfish and then chugs in a circle in the bedroom until she has reached Jules' chair, one of the many, recurrent visuals of circular imagery that Truffaut utilizes in the film. You shouldn't feel bad for Jim — he's busy bedding his frequent lover Gilberte (Vanna Urbino) and making excuses to depart her bed before the sun rises despite her request to lie beside her for a complete night for a change. Jim nixes that idea, saying that if they did that they might as well be married and she'd expect him to stay the next night as well. Gilberte expresses skepticism at his excuse, especially when he suggests that she imagine he's working at a factory, betting that his plan involves sleeping until noon. Later that night, Jules, Jim and Thérèse go to a café and no sooner have they sat down that after making eyes at another man, Thérèse asks Jules for some change to play music. He complies, she takes the money and the man follows her. Thérèse asks if she can stay with him that night and the two depart. Jules starts to stand in outrage, but Jim grabs his arm and he sits back down. "Lose one, find 10 more," Jim advises. Jules admits that he didn't love Thérèse. "She was both mother and doting daughter at the same time," Jules says, sighing that he doesn't have luck with Parisian women. He shows Jim photos of some of the women back home he loves, presenting them in order of preference and contemplating returning for one of them in a couple of months if the situation in France doesn't change. However, Jules lacks a photograph of one named Helga so he sketches her in broad strokes on the café's table. Jim tries to buy the table, but the establishment's owner refuses unless he purchases the entire set.

man, Thérèse asks Jules for some change to play music. He complies, she takes the money and the man follows her. Thérèse asks if she can stay with him that night and the two depart. Jules starts to stand in outrage, but Jim grabs his arm and he sits back down. "Lose one, find 10 more," Jim advises. Jules admits that he didn't love Thérèse. "She was both mother and doting daughter at the same time," Jules says, sighing that he doesn't have luck with Parisian women. He shows Jim photos of some of the women back home he loves, presenting them in order of preference and contemplating returning for one of them in a couple of months if the situation in France doesn't change. However, Jules lacks a photograph of one named Helga so he sketches her in broad strokes on the café's table. Jim tries to buy the table, but the establishment's owner refuses unless he purchases the entire set.

That night, they go to the home of Jules' friend Albert (played by Serge Rezvani, a renaissance artist, though he prefers the term multidisciplinarian, who billed himself as Bassiak here and added the first name Boris when taking credit as the composer of "Le Tourbillon" that Moreau memorably sings) to see his slides of ancient sculptures he found around the country. (Somehow it slips my mind between viewings of Jules and Jim how little dialogue the actors actually get to speak openly in the film in favor of voiceover. For example, when Jules and Jim enter Albert's place, they exchange introductions out loud but then Henri Serre as Jim doesn't simply ask Oskar Werner's Jules, "Who's Albert?" Instead, we hear Michel Subor's narrator say, "Jim asked" — When I first heard

this the first few times I watched the film, it sounded as if Subor narrated this entire dialogue. After hearing it for the umpteenth time, it sounds as if Subor merely starts it the Serre asks in voiceover, "Who's Albert?" with Werner's voice replying, "A friend to artists and sculptors. He knows everyone who'll be famous in 10 years." I can't say with 100% certainty which interpretation stands as the correct answer. I've looked for verification, but found none. Jules' response tipped me in that direction because Werner's voice can be distinguished easily from Subor's while Serre's falls in the same vocal range.) One slide of a stone face particularly strikes the friends' fancy — and Subor definitely

this the first few times I watched the film, it sounded as if Subor narrated this entire dialogue. After hearing it for the umpteenth time, it sounds as if Subor merely starts it the Serre asks in voiceover, "Who's Albert?" with Werner's voice replying, "A friend to artists and sculptors. He knows everyone who'll be famous in 10 years." I can't say with 100% certainty which interpretation stands as the correct answer. I've looked for verification, but found none. Jules' response tipped me in that direction because Werner's voice can be distinguished easily from Subor's while Serre's falls in the same vocal range.) One slide of a stone face particularly strikes the friends' fancy — and Subor definitely describes this, informing the viewer, "The tranquil smile of the crudely sculpted face mesmerized them. The statue was in an outdoor museum on an Adriatic island. They set out immediately to see it. They both had the same white suit made. They spent an hour by the statue. It exceeded their expectations. They walked rapidly around it in silence. They didn't speak of it until the next day. Had they ever met such a smile? Never. And if they ever did, they'd follow it. Jules and Jim returned home, full of this revelation. Paris took them gently back in." Later, Jules and Jim hit the gym where they spar with some kickboxing. Jules inquires about the progress of Jim's book. Jim tells him he thinks it's going well and will turn out to be very autobiographical and concern their friendship. He proceeds to read Jules a passage. "Jacques and Julien were inseparable. Julien's last novel had been a success. He had described, as if in a fairy tale, the women he had known before he met Jacques or even Lucienne. Jacques was proud for Jules' sake. People called them Don Quixote and Sancho Panza and rumors circulated behind their

describes this, informing the viewer, "The tranquil smile of the crudely sculpted face mesmerized them. The statue was in an outdoor museum on an Adriatic island. They set out immediately to see it. They both had the same white suit made. They spent an hour by the statue. It exceeded their expectations. They walked rapidly around it in silence. They didn't speak of it until the next day. Had they ever met such a smile? Never. And if they ever did, they'd follow it. Jules and Jim returned home, full of this revelation. Paris took them gently back in." Later, Jules and Jim hit the gym where they spar with some kickboxing. Jules inquires about the progress of Jim's book. Jim tells him he thinks it's going well and will turn out to be very autobiographical and concern their friendship. He proceeds to read Jules a passage. "Jacques and Julien were inseparable. Julien's last novel had been a success. He had described, as if in a fairy tale, the women he had known before he met Jacques or even Lucienne. Jacques was proud for Jules' sake. People called them Don Quixote and Sancho Panza and rumors circulated behind their backs about their unusual friendship. They ate together in small restaurants, and each splurged on the best cigars to give the other." Jules finds the writing beautiful and offers to translate it to German. Jim's brief allusion in his novel to "rumors" about his friendship with Jules marks the closest the film ever comes to implying anything homoerotic between the men. While Jules and Jim opened the door for many cinematic variations on your standard triangle, we'd still need almost 40 years before Y Tu Mama Tambien. As the guys shower, Jules announces that his cousin wrote him and three girls that studied with him in Munich would be visiting Paris — one from Berlin, one from Holland and one from there in France, Jules plans to host a dinner for the visitors the next night. Neither friend has any idea who Catherine happens to be yet or that she will be the French girl in that group of visitors. This Quixote and Sancho soon will be tilting at a very shapely and unpredictable windmill that will change the course of all three lives forever. The next night, when Catherine (Moreau) descends the stairs and lifts the lace netting covering her face, her resemblance to the sculpture stuns Jules and Jim, something Truffaut emphasizes through quick cuts, and Michel Subor's narration, and the young men will keep the oath they made to that statue — they've found that smile, now they must follow it.

backs about their unusual friendship. They ate together in small restaurants, and each splurged on the best cigars to give the other." Jules finds the writing beautiful and offers to translate it to German. Jim's brief allusion in his novel to "rumors" about his friendship with Jules marks the closest the film ever comes to implying anything homoerotic between the men. While Jules and Jim opened the door for many cinematic variations on your standard triangle, we'd still need almost 40 years before Y Tu Mama Tambien. As the guys shower, Jules announces that his cousin wrote him and three girls that studied with him in Munich would be visiting Paris — one from Berlin, one from Holland and one from there in France, Jules plans to host a dinner for the visitors the next night. Neither friend has any idea who Catherine happens to be yet or that she will be the French girl in that group of visitors. This Quixote and Sancho soon will be tilting at a very shapely and unpredictable windmill that will change the course of all three lives forever. The next night, when Catherine (Moreau) descends the stairs and lifts the lace netting covering her face, her resemblance to the sculpture stuns Jules and Jim, something Truffaut emphasizes through quick cuts, and Michel Subor's narration, and the young men will keep the oath they made to that statue — they've found that smile, now they must follow it. While for me, Jules and Jim stands at the high watermark of the French New Wave films, I know many others won't agree and when you look objectively at the story of Jules and Jim, it may employ many of that movement's techniques but many aspects of Truffaut's film set it apart from its cinematic brethren such as its period setting and a time span that covers more than two decades. Jules and Jim also caused moral uproars about the open relationships among the various characters in the film (and though Jules, Jim and Catherine might be involved simultaneously, they never took part in a ménage à trois). In a funny way, the 1962 film forecast the free love movement to come later that decade except its source material happened to be a semiautobiographical novel set in the early part of the 20th century. The prurience though lies in the mind of the fuddy duddy because part of what makes Jules and Jim so special comes from Truffaut's refusal to pass any judgment, be it positive or negative, upon the behavior of his characters. Despite the director's own criticism many years down the road that the film isn't cruel enough when it comes to love, the three main characters do suffer by the end but he doesn't paint it as punishment for their sins.

Tweet

Labels: 60s, Books, Criticism, Dunaway, Fiction, Fitzgerald, Foreign, Mickey Rourke, Movie Tributes, Ray Top 100, Renoir, Sayles, Soderbergh, Truffaut, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE