Thursday, May 16, 2013

Leave the rooster story alone. That's human interest.

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post originally appeared Jan. 18, 2010. I'm re-posting it as part of The Howard Hawks Blogathon occurring through May 31 at Seetimaar — Diary of a Movie Lover

By Edward Copeland

The list of remakes that exceed the original is a short one, especially when the original was a good one, but there never has been a better remake than Howard Hawks' His Girl Friday, which took the brilliance of The Front Page and turned it to genius by making its high-energy farce of an editor determined by hook or by crook to hang on to his star reporter by turning the roles of the two men into ex-spouses. Icing this delicious cake, which marks its 70th anniversary today, comes from casting Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell as the leads.

Words open His Girl Friday declaring that it takes place in the dark ages of journalism when getting that story justified anything short of murder, but insists that it bears no resemblance to the press of its day, 1940 in this case. What saddens me today is, despite the ethical lapses and underhandedness and downright lies

committed by the reporters in this version (and really all versions based on the original play The Front Page by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, themselves once Chicago journalists), their energetic devotion to capturing the story seems downright heroic compared to the herd mentality and lack of intellectual curiosity we see exhibited most of the time today by pack journalists such as the White House press corps. It's really why the first two film versions of the play are the only ones that work. The 1931 Lewis Milestone adaptation starring Adolphe Menjou definitely belonged to its time and Hawks' take with its inspired twist came along close enough to remain relevant. When Billy Wilder tried to remake the original in 1974 as a period piece with Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau, it fell flat because in the era of Vietnam and Watergate, journalists actually existed in a moment of heroism for their profession. The 1988 disaster Switching Channels returned to the His Girl Friday model with Burt Reynolds and Kathleen Turner and tried to set it in the world of cable news but the only update they came up with was hiding the fugitive in a copy machine instead of a rolltop desk.

committed by the reporters in this version (and really all versions based on the original play The Front Page by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, themselves once Chicago journalists), their energetic devotion to capturing the story seems downright heroic compared to the herd mentality and lack of intellectual curiosity we see exhibited most of the time today by pack journalists such as the White House press corps. It's really why the first two film versions of the play are the only ones that work. The 1931 Lewis Milestone adaptation starring Adolphe Menjou definitely belonged to its time and Hawks' take with its inspired twist came along close enough to remain relevant. When Billy Wilder tried to remake the original in 1974 as a period piece with Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau, it fell flat because in the era of Vietnam and Watergate, journalists actually existed in a moment of heroism for their profession. The 1988 disaster Switching Channels returned to the His Girl Friday model with Burt Reynolds and Kathleen Turner and tried to set it in the world of cable news but the only update they came up with was hiding the fugitive in a copy machine instead of a rolltop desk.Each time I write one of these anniversary tributes, no matter how many times I've seen the film in question (and I can't count that high when we're discussing Friday, I try to watch the movie again, in a quest for fresh thoughts and reminders of lines that may have slipped my mind. In nearly every, case I notice something new (and with the rapid-fire pace of Friday's dialogue, remembering them all borders on impossible). What stood out as I

started this salute wasn't just the work-a-day newshounds it depicts compared to the state of the industry today but the social subtext emerged more prominently this time. It's not that I've missed or ignored it before, but it's the light-speed comic hijinks that keeps me coming back. The story's main focus may concern Walter Burns (Grant), that sneaky editor of the Morning Post, trying to keep his ex-wife Hildy Johnson (Russell) from leaving the paper and his life to wed insurance agent Bruce Baldwin, who looks like that fellow in the movies, you know, Ralph Bellamy (who fortunately plays Bruce). However, the story Walter uses to keep his hooks into Hildy concerns that of Earl Williams (John Qualen), a man who killed a cop and received a ticket on a bullet train to the gallows by a politically hungry Republican mayor with an eye on unseating the Democratic, anti-death penalty governor, despite the fact the reporters and many others believe Earl's mental

started this salute wasn't just the work-a-day newshounds it depicts compared to the state of the industry today but the social subtext emerged more prominently this time. It's not that I've missed or ignored it before, but it's the light-speed comic hijinks that keeps me coming back. The story's main focus may concern Walter Burns (Grant), that sneaky editor of the Morning Post, trying to keep his ex-wife Hildy Johnson (Russell) from leaving the paper and his life to wed insurance agent Bruce Baldwin, who looks like that fellow in the movies, you know, Ralph Bellamy (who fortunately plays Bruce). However, the story Walter uses to keep his hooks into Hildy concerns that of Earl Williams (John Qualen), a man who killed a cop and received a ticket on a bullet train to the gallows by a politically hungry Republican mayor with an eye on unseating the Democratic, anti-death penalty governor, despite the fact the reporters and many others believe Earl's mental illness should stop his hanging. Qualen, a solid character actor in many films, and Mollie Malloy (Helen Mack), a woman who befriended Earl prior to the slaying and who the tabloids misrepresent as his lover and a prostitute, stand apart as the only characters in this screwball farce who play it completely straight. (In an all-time bit of miscasting, in the Wilder remake, Carol Burnett got the Mollie Malloy role. Of course, the nearly 50-year-old Jack Lemmon also was engaged to the 28-year-old Susan Sarandon in that film.) His Girl Friday requires neither Qualen nor Mack to garner laughs like every other character. As the courthouse reporters behave particularly cruelly to Mollie at one point, only Hildy comforts her. "They ain't human," Mollie cries. "I know," Hildy sympathizes. "They're newspapermen." Hildy realizes the jobless Earl spent too much time listening to socialist speeches in the park and his fascination with the concept of "production for use" led to his fatal error.

illness should stop his hanging. Qualen, a solid character actor in many films, and Mollie Malloy (Helen Mack), a woman who befriended Earl prior to the slaying and who the tabloids misrepresent as his lover and a prostitute, stand apart as the only characters in this screwball farce who play it completely straight. (In an all-time bit of miscasting, in the Wilder remake, Carol Burnett got the Mollie Malloy role. Of course, the nearly 50-year-old Jack Lemmon also was engaged to the 28-year-old Susan Sarandon in that film.) His Girl Friday requires neither Qualen nor Mack to garner laughs like every other character. As the courthouse reporters behave particularly cruelly to Mollie at one point, only Hildy comforts her. "They ain't human," Mollie cries. "I know," Hildy sympathizes. "They're newspapermen." Hildy realizes the jobless Earl spent too much time listening to socialist speeches in the park and his fascination with the concept of "production for use" led to his fatal error.

Social message aside, it's the earth-shattering cosmic comic chemistry of Grant and Russell, aided by Bellamy's perfect innocent foil and countless supporting vets. (One of them, Billy Gilbert, plays Mr. Pettibone (Roz holds his tie in the photo above) and I wish I could have found a good closeup photo of him because I think it's hysterical how much 9/11 mastermind/terrorist asshole Khalid Sheikh Mohammed resembles Gilbert in KSM's arrest mugshot.) The lines come fast and furious. While many do come from the original Hecht-MacArthur play, Hawks gets the credit for the film's amazing speed (though screenwriter Charles Lederer deserves more kudos). Still, in the end, Cary and Roz make the dialogue sizzle and Grant's physical touches serve as a master class in comic movement on film. Watch every little bounce he makes as Hildy kicks him beneath the table when he's trying to get things past poor Bruce and you'll crack up every time. Originally, I was writing down all my favorite lines, planning to try to work them all into this tribute, but then I thought: Maybe not everyone has seen His Girl Friday, even after 70 years,

_04.jpg)

Tweet

Labels: 40s, Bellamy, Burt Reynolds, Cary, Hawks, Hecht, K. Turner, Lemmon, Matthau, Menjou, Milestone, Movie Tributes, Remakes, Roz Russell, Susan Sarandon, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, May 18, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part I

By Edward Copeland

"First comes the word, then comes the rest" might be the most famous quote attributed to Richard Brooks, who began his life 100 years ago today in Philadelphia as Ruben Sax, son of Jewish immigrants Hyman and Esther Sax. He wrote a lot of words too — sometimes using only images. In fact, too many to tell the story in a single post. so it will be three. His parents came from Crimea in 1908 when it belonged to the Russian Empire. Like the parents of a great director of a much later generation and an Italian Catholic heritage, Hyman and Esther Sax also worked in the textile and clothing industry. Sax's entire adult working life revolved around the written word — even while he busied himself with other tasks. “I write in toilets, on planes, when I’m

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

Though Brooks' legend derives predominantly from his film legacy, he experienced his first rush of acclaim with the publication of his debut novel, written while stationed at Quantico at night in the bathroom, according to the account in Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks by Douglass K. Daniel. Several publishers rejected it until Edward Aswell at Harper & Brothers, who also edited Thomas Wolfe, agreed to take it — and he shocked Brooks further by telling him (after a few suggestions) they planned to publish in May 1945. This news flabbergasted Brooks who obtained a weekend pass to go to New York because Aswell insisted on informing him in person. Now Brooks had to return to Quantico where the top officers of the Corps about shit bricks when The New York Times published a big review of The Brick Foxhole soon after it hit shelves. (Orville Prescott's take was mixed, assessing it as compulsively readable but weak on characterization.) Its story of hate and intolerance within the Marines brought threats of court-martialing Brooks, since he'd ignored procedure and never submitted the novel to Marine officials for approval ahead of time. They wanted to avoid bad publicity, especially with all the good feelings as the war wound down. "There was nothing in that book that violated security, but their rules and regulations were not for that purpose alone," Brooks told Daniel. Aswell prepared to launch a P.R. counteroffensive with literary giants such as Sinclair Lewis and Richard Wright ready to stand by Brooks. In case you don't know the story of the novel, it concerns a Marine unit in its barracks and on leave in Washington. Through their wartime experiences, some of the men truly turned ugly, suspecting cheating wives and tossing hate against any non-white Christian. It turns out, though the real Marines let the matter drop, what bothered them

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

While he didn't want to make a movie of The Brick Foxhole himself, another former newspaperman turned socially conscious film artist met with Brooks about working with his independent production company. At first, Mark Hellinger tried to lure Brooks away from Universal with the promise of doubling his salary if he'd adapt a play he liked into a movie, but before Brooks could consider that offer, Hellinger called with a more pressing matter. He was producing an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's famous short story The Killers. The problem: someone had to dream up what happened after the brief tale ends because it certainly wouldn't last 90 minutes otherwise. Hellinger flew Brooks out to meet Papa himself, but he didn't get much out of him but he did come up with an idea for what would happen after the story ends. Hellinger liked it and sent it to John Huston, who wrote the screenplay as a favor. Since both Brooks and Huston had contracts at other studios, neither got screen credits, so Ernest Hemingway's The Killers' official screenplay credit goes to Anthony Veiller, who received an Oscar nomination for best screenplay. He'd previously shared a nomination in the same category for Stage Door. The film also made a star out of Burt Lancaster, who would work with Brooks several times and be his lifelong friend. In fact, Lancaster would star in the next screenplay that Brooks wrote, a Mark Hellinger production directed by one of those people Edward Dmytryk eventually would name before the House Un-American Activities Committee. The film, of course, would be the still-powerful Brute Force, the director, Jules Dassin.

John Huston wasn't happy. Producer Jerry Wald called him, excitement in his voice, to tell him he'd secured the rights to Maxwell Anderson's Broadway play Key Largo for Huston to direct. This didn't thrill Huston, who thought the play gave new meaning to the word awful. Written in blank verse, Anderson's play concerned a deserter from the Spanish-American War. People at a hotel do get taken hostage, but by Mexican hostages. Essentially, Huston tossed the play in the trash bin. Huston hired Brooks to co-write an in-title only version and, still pissed at Wald, barred him from the set. Part of Huston's anger stemmed from the HUAC nonsense, (His outrage would drive him to move to Ireland for a large part of the 1950s.) so he couldn't stomach adapting a play by Anderson whom he considered a reactionary because of his hate of FDR. Despite Huston's distaste for the project, he

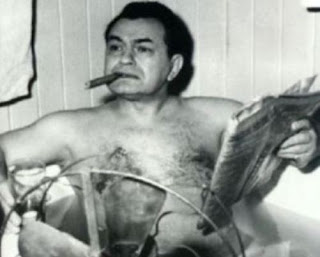

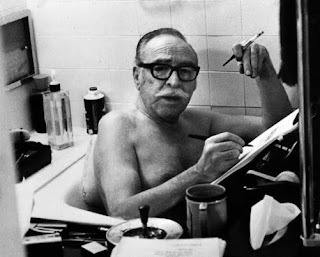

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.While I would have liked to have viewed more of Brooks' work that I've never seen (and to re-visit some which I have), time and availability, combined with his prolific nature and the industry's increasingly cavalier willingness to let both old and recent films fade into oblivion, proved to be a problem. After Huston's generosity, Brooks' directing debut would arrive two years later. Four films where Brooks worked

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.

enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.With 1955, Brooks wrote and directed the first film that truly garnered him an identity as more than a writer who directs but as a director with Blackboard Jungle, a film that admittedly manages to look both dated and timely simultanouesly, First, as so many old films did, it had to start with a long scroll explaining that American schools maintain high standards, but we need to worry about these juvenile

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk.

desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk. Tweet

Labels: blacklist, Bogart, Capra, Cary, Dassin, Doris Day, Edward G., Fiction, Fitzgerald, Fuller, Ginger Rogers, Glenn Ford, Hemingway, Huston, Lancaster, Liz, Mazursky, Poitier, Robert Ryan, Widmark

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, May 07, 2012

Love Story

— Orson Welles on Make Way for Tomorrow

By John Cochrane

No one film dominated the 1937 Academy Awards, but with the country still in the grips of the Great Depression and slowly realizing Europe’s inevitable march back into war, the subtle theme of the evening in early 1938 seemed to be distant escapism — anything to help people forget the troubled times at home. The Life of Emile Zola, a period biopic set in France, won best picture. Spencer Tracy received his first best actor Oscar, playing a Portuguese sailor in Captains Courageous, and Luise Rainer was named best actress for a second year in a row, playing the wife of a struggling Chinese farmer in the morality tale The Good Earth.

Best director that year went to Hollywood veteran Leo McCarey for The Awful Truth. McCarey’s resume was impressive. He paired Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy together as a team, and he had directed, supervised or helped write much of their best silent work. He had collaborated with W.C. Fields, Charley Chase, Eddie Cantor, Mae West, Harold Lloyd, George Burns and Gracie Allen — almost an early Hollywood Comedy Hall of Fame. He had also directed the Marx Brothers in the freewheeling political satire Duck Soup (1933) — generally now considered their best film. The Awful Truth was a screwball comedy about an affluent couple whose romantic chemistry constantly sabotages their impending divorce that starred Irene Dunne, Ralph Bellamy — and a breakout performance by a handsome leading man named Cary Grant — who supposedly had based a lot of his on-screen persona on the personality of his witty and elegant director. Addressing the Academy, the affable McCarey said “Thank you for this wonderful award. But you gave it to me for the wrong picture.”

The picture that McCarey was referring to was his earlier production from 1937, titled Make Way for Tomorrow — an often tough and unsentimental drama about an elderly couple who loses their home to foreclosure and must separate when none of their children are able or willing to take them both in. The film opened to stellar reviews and promptly died at the box office — being unknown to most people for decades. Fortunately, recent events have begun to rectify this oversight as this buried American cinematic gem turns 75 years old.

Based on Josephine Lawrence’s novel The Years Are So Long, the film opens at the cozy home of Barkley and Lucy Cooper (Victor Moore, Beulah Bondi), who have been married for 50 years. Four of their five children have arrived for what they believe will be a joyous family dinner — until Bark breaks the news that he hasn’t been able to keep up with the

mortgage payments since being out of work and that the bank will repossess the property within days. Bark and Lucy insist that they will stay together, regardless of what happens. With little time to plan, the family decides that, for the time being, Lucy will move to New York to live with their eldest son George’s family in their apartment, while Bark will be 360 miles away — sleeping on the couch at the home of their daughter Cora (Elisabeth Risdon) and her unemployed husband Bill (Ralph Remley). For the film's first hour or so, we see Bark and Lucy trying to adjust to their new surroundings. While George (an excellent Thomas Mitchell) tries to be as pleasant and accommodating to his mother as possible, his wife Anita (Fay Bainter) and daughter Rhoda (Barbara Read) display little patience and dislike the disruption of their routines. Meanwhile, Bark spends his time walking around his new hometown, looking for a job and visiting a new friend, a local shopkeeper named Max Rubens (Maurice Moscowitz).

mortgage payments since being out of work and that the bank will repossess the property within days. Bark and Lucy insist that they will stay together, regardless of what happens. With little time to plan, the family decides that, for the time being, Lucy will move to New York to live with their eldest son George’s family in their apartment, while Bark will be 360 miles away — sleeping on the couch at the home of their daughter Cora (Elisabeth Risdon) and her unemployed husband Bill (Ralph Remley). For the film's first hour or so, we see Bark and Lucy trying to adjust to their new surroundings. While George (an excellent Thomas Mitchell) tries to be as pleasant and accommodating to his mother as possible, his wife Anita (Fay Bainter) and daughter Rhoda (Barbara Read) display little patience and dislike the disruption of their routines. Meanwhile, Bark spends his time walking around his new hometown, looking for a job and visiting a new friend, a local shopkeeper named Max Rubens (Maurice Moscowitz).Many filmmakers develop a visual signature that dominates their work, but McCarey employs a fairly basic and straightforward style, using group and reaction shots as well as perceptive editing that places the emphasis on the actors and the story. Working with screenwriter Vina Delmar, McCarey creates set pieces that blend touches of light comedy and everyday drama that feel so correct and truthful that audiences likely feel a sometimes uncomfortable recognition with them. Often, this stems from McCarey's use of improvisation to sharpen his scenes before filming them. If short on ideas, he would play a nearby piano on the set until he figured out what to do. This practice creates a freshness that, as Peter Bogdanovich points out, gives the impression that what you’re watching wasn't planned but just happened. A large part of the film’s greatness also comes from the cast, headed by Moore and Bondi as Bark and Lucy. Both theatrically trained actors, vaudeville star Moore (age 61) and future Emmy winner Bondi (age 48), through the wonders of make-up and black and white photography prove completely convincing as an elderly couple in their 70s.

Moore performs terrifically as the blunt, but loving Bark. Bondi gives an even better turn as Lucy. In one scene, representative of McCarey’s direction and Bondi’s performance, Lucy inadvertently interrupts a bridge-playing class being taught by her daughter-in-law at the apartment by making small talk and noticing the cards in players’ hands. She’s an intrusion, but by the end of the evening, after being abandoned by her granddaughter at the movies and returning home, she takes a phone call in the living room from her husband. Critic Gary Giddins notes that as the class listens in to her side of the conversation, she becomes highly sympathetic — and the scene now flips with the card students visibly moved and feeling invasive of her space and privacy. Then there’s the crucial scene where Lucy sees the writing on the wall and offers to move out of the apartment and into a nursing home without Bark’s knowledge, before her family can commit her — so as not to be a burden to them anymore. She shares a loving moment with her guilt-ridden son George. (“You were always my favorite child,” she sincerely tells him.) His disappointment in himself in the scene’s coda resonates deeply. Lucy’s character seems meek and easily taken advantage of when we first meet her, but she’s really the strongest person in the story. It’s her love and sacrifice for her husband and family that give the movie much of its emotional weight, and the unforgettable final shot belongs to her.

McCarey and Delmar create totally believable characters and it should be pointed out that while friendly, decent people, Bark and Lucy, by no means, lack flaws. Bark doesn't make a particularly good patient when sick in bed two-thirds of the way through the story, and Lucy stands firm in her ways and beliefs — traits that can annoy, but people can be that way. Even the children aren’t bad — they have reasons that the audience can understand — even if we don’t agree with their often seemingly selfish or preoccupied behavior. This delicate skill of observation was not lost on McCarey’s good friend, the great French director Jean Renoir, who once said, “McCarey understands people better than anyone in Hollywood.”

As memorable a first hour as Make Way for Tomorrow delivers, McCarey saves the best moments for the film’s third act. Bark and Lucy meet one last time in New York, hours before his train departure for California to live with their unseen daughter Addie for health reasons. For the first time since the opening scene, the couple finally reunites. The last 20 minutes of the picture overflows with what Roger Ebert refers to in his Great Movies essay on the film as mono no aware — which roughly translated means “a bittersweet sadness at the passing of all things.” Regrets, but nothing that Bark and Lucy really would change if they had to do everything over again.

Throughout the story, the Coopers often have been humiliated or brushed off by their children. When a car salesman (Dell Henderson) mistakes them for a wealthy couple and takes them for a ride in a fancy car, the audience cringes — expecting another uncomfortable moment — but then something interesting happens. As they arrive at their destination and an embarrassed Bark and Lucy explain that there’s been a misunderstanding, the salesman tactfully assuages their concerns. He allows them to save face, by saying his pride in the car made him want to show it off. Walking into The Vogard Hotel where they honeymooned 50 years ago, the Coopers get treated like friends or VIPs — first by a hat check girl (Louise Seidel) and then by the hotel manager (Paul Stanton), who happily takes his time talking to them and comps their bar tab. Bark and Lucy's children expect their parents at George’s apartment for dinner, but Bark phones them to say that they won't be coming.

At one point, we see the couple from behind as they sit together, sharing a loving moment of intimate conversation. As Lucy leans toward her husband to kiss him, she seems to notice the camera and demurely stops herself from such a public display of affection. It’s an extraordinary sequence that’s followed by another one when Bark and Lucy get up to dance. As they arrive on the dance floor, the orchestra breaks into a rumba and the Coopers seem lost and out of place. The watchful bandleader notices them, without a word, quickly instructs the musicians to switch to the love song “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.” Bark gratefully acknowledges the conductor as he waltzes Lucy around the room. Then the clock strikes 9, and Bark and Lucy rush off to the train station for the film’s closing scene.

Paramount studio head Adolph Zukor reportedly visited the set several times, pleading with his producer-director to change the ending, but McCarey — who saw the movie as a labor of love and a personal tribute to his recently deceased father — wouldn’t budge. The film was released to rave reviews, though at least one reviewer couldn’t recommend it because it would “ruin your day.” Industry friends and colleagues such as John Ford and Frank Capra were deeply impressed. McCarey even received an enthusiastic letter from legendary British playwright George Bernard Shaw, but the Paramount marketing department didn’t know what to do with the picture. Audiences, still facing a tough economy, didn’t want to see a movie about losing your home and being marginalized in old age. They stayed away, while the Motion Picture Academy didn’t seem to notice. McCarey was fired from his contract at Paramount (later rebounding that year at Columbia with the unqualified success of The Awful Truth), and the film seemed to disappear from view for many years.

The movie never was forgotten completely though. Screenwriter Kogo Noda, who wrote frequently with the great Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu, saw the film and used it as an inspiration for Ozu’s masterpiece Tokyo Story (1953), in which an elderly couple journey to the big city to visit their adult children and quietly realize that their offspring don’t have time for them in their busy lives — only temporarily getting their full attention when one of the parents unexpectedly dies during the trip home. Ironically, Ozu’s film also would be unknown to most of the world for decades, until exported in the early 1970s, almost 10 years after the master filmmaker’s death. Tokyo Story, with its sublime simplicity and quiet insight into human nature now is considered by many critics and filmmakers to be one of the greatest movies ever made — placing high in the Sight & Sound polls of 1992 and 2002. In the meantime, Make Way for Tomorrow slowly started getting more attention in its own right, probably sometime in the mid- to late 1960s. Although the movie never was released on VHS, it occasionally was shown enough on television to garner a devoted underground following. More recently, the movie played at the Telluride Film Festival, where audiences at sold out screenings were stunned by its undeniable quality and its powerful, timeless message. Make Way for Tomorrow was finally was released on DVD by The Criterion Collection and was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress on the National Film Registry in 2010.

The funny phenomenon of how audiences in general dislike unhappy endings, and yet somehow our psyches depend on them always proves puzzling. Classics such as Casablanca (1942), Vertigo (1958), The Third Man (1949 U.K.; 1950 U.S.) and even the fictional romance in a more contemporary hit such as Titanic (1997) wouldn't carry the same stature or mystique in popular culture if they somehow had been pleasantly resolved. Life often disappoints and turns out unpredictably, messy and frequently filled with loss. Even though many people claim they don’t like sad stories, it comforts somehow to know that we aren’t alone — that others understand and feel similarly as we do about life’s experiences. It’s what makes us human.

Make Way for Tomorrow serves as many things. It’s a movie about family dynamics and the Fifth Commandment. Gary Giddins points out that it’s also a message film about the need for a safety net such as Social Security — which hadn't been fully implemented when the

picture was released. It’s a plea for treating each other with more kindness — in a culture that increasingly pushes the old aside to embrace the young and the new, and it’s one of the saddest movies ever made. At its most basic level, it’s a tender love story between two people who have spent most of their lives together — knowing each other so well that words often seem unnecessary. However you choose to look at it, Make Way for Tomorrow remains one of the greatest American films — certainly a strong contender for the best classic Hollywood movie that most people have never heard of. Leo McCarey would create highly successful hits that were more sentimental later on in his career — including the enjoyable romance Love Affair (1939) and its subsequent color remake An Affair to Remember (1957), starring Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr. He also would direct Bing Crosby as a charismatic priest in 1944’s Going My Way (7 Oscars — including picture, director, actor) and its superior sequel, 1945’s The Bells of St. Mary’s (8 nominations, 1 win), co-starring Ingrid Bergman, but he never forgot about Make Way for Tomorrow, which remained a personal favorite until the day he died from emphysema in 1969. Leo McCarey did not live to see his masterpiece fully appreciated, but that wasn't necessary. In 1938, he knew the film’s value.

picture was released. It’s a plea for treating each other with more kindness — in a culture that increasingly pushes the old aside to embrace the young and the new, and it’s one of the saddest movies ever made. At its most basic level, it’s a tender love story between two people who have spent most of their lives together — knowing each other so well that words often seem unnecessary. However you choose to look at it, Make Way for Tomorrow remains one of the greatest American films — certainly a strong contender for the best classic Hollywood movie that most people have never heard of. Leo McCarey would create highly successful hits that were more sentimental later on in his career — including the enjoyable romance Love Affair (1939) and its subsequent color remake An Affair to Remember (1957), starring Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr. He also would direct Bing Crosby as a charismatic priest in 1944’s Going My Way (7 Oscars — including picture, director, actor) and its superior sequel, 1945’s The Bells of St. Mary’s (8 nominations, 1 win), co-starring Ingrid Bergman, but he never forgot about Make Way for Tomorrow, which remained a personal favorite until the day he died from emphysema in 1969. Leo McCarey did not live to see his masterpiece fully appreciated, but that wasn't necessary. In 1938, he knew the film’s value.It’s a marvelous picture. Bring plenty of Kleenex.

Tweet

Labels: 30s, Bellamy, Bogdanovich, Capra, Cary, Deborah Kerr, Ebert, Fields, Ingrid Bergman, Irene Dunne, John Ford, Luise Rainer, Marx Brothers, McCarey, Movie Tributes, Oscars, Renoir, T. Mitchell, Tracy, Welles

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, March 10, 2012

Bringing Up Babs

By Damian Arlyn

I remember working in the video store one day when a regular customer came in to check out a few titles. He glanced at the enormous flat screen we had behind the counter, saw Barbra Streisand belting out some catchy show tune and uttered a question I got asked a lot in those days. "What are you watching?" he said. "Hello, Dolly!" I answered. He smiled, shook his head and exclaimed, "See, now, here's where I break with the stereotype. I'm a gay guy who doesn't like Barbra Streisand." I just laughed and replied, "That's OK. I'm a straight guy who does."

And it's true. Although she is by no means my favorite actress (nor would I ever see a film simply because she's in it), I happen to enjoy watching her onscreen. Funny Girl, Meet the Fockers and the aforementioned Hello, Dolly! are all films I love, but my favorite movie of hers would have to be the hilarious What's Up, Doc? which celebrates its 40th anniversary today. Nowhere is Babs' gift for comedy and sheer charisma on display better than in this film. They even find an excuse to show off her incredible voice once or twice: namely, in the film's opening and ending credits where she sings Cole Porter's "You're The Top" as well as the scene at the piano when she croons a few lines of "As Time Goes By."

It also doesn't hurt that What's Up, Doc? happens to be a really great movie. Hot off of his success with The Last Picture Show, Peter Bogdanovich originally conceived it as a remake of Howard Hawks' Bringing Up Baby, but wisely decided (much as Lawrence Kasdan would do later with his film noir tribute Body Heat) to use Hawks' film merely as an inspiration rather than a template and to give What's Up, Doc? its own identity. As a result, it comes off more as a love letter to screwball comedies in general as well as to iconic Warner Bros. feature films (such as Casablanca) and classic animated shorts. Hence, when Barbra's character, Judy Maxwell, is introduced first to Ryan O'Neal's nerdy Howard Bannister, she's seen munching on a carrot a la Bugs Bunny and/or Clark Gable from It Happened One Night. With her brash, fast-talking, trouble-making personality and his stiff, bespectacled, long-suffering demeanor, the two leads clearly are based on Baby's Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn. (Interestingly, Streisand shared a best actress Oscar with Ms. Hepburn only four years earlier in one of the Academy's rare ties. Streisand won for her film debut in Funny Girl while Hepburn earned her third best actress trophy for The Lion in Winter. Hepburn's prize was her second consecutive win in the category having taken the 1967 Oscar for Guess Who's Coming to Dinner.) Aside from Judy constantly getting Howard into trouble and a reminiscent coat-tearing gag, the similarities between Doc and Baby essentially end there.

Also, What's Up, Doc? lacks a leopard. Instead the chaos revolves around four identical carrying cases containing such varied items as clothes, rocks, jewels and classified government documents. When moviegoers first see the quartet of cases at the start of Doc, it's the filmmakers signaling audiences that much confusion and hilarity awaits. At this point I have to confess that, although I've seen the film at least a dozen times, I cannot to this day follow which case is which throughout the course of the film. Every time I sit down to watch, I swear I'm going to keep track of the cases, but I always give up about 20 minutes into it. I take some comfort, however, from the fact that even the great Buck Henry, in the process of re-writing the screenplay, reportedly phoned Bogdanovich to say, "I've lost one of the suitcases. It's in the hotel somewhere, but I don't know where I put it."

The gags come fast and furious in What's Up, Doc? More than a decade before Bruce Willis and Bogdanovich's ex-girlfriend Cybill Shepherd resurrected rapid-fire banter on TV's Moonlighting, Streisand and O'Neal fire a barrage of zingers at each other so quickly that you're almost afraid to laugh for fear you'll miss the next one. The behind-the-scenes team also populates the What's Up, Doc? universe with a whole host of kooky characters, each bringing his or her unique comic flair to those roles. There isn't a single boring person in What's Up, Doc? Everyone (right down to the painter who drops his cigar into the bucket) amuses. At the top of the heap resides the great Madeline Kahn in her feature film debut as Howard's frumpy fiancée Eunice Burns. Two years before she joined Mel Brooks' cinematic comedy troupe, she proved to the world her status as one of the funniest women ever to grace the silver screen. Another Mel Brooks' regular, Kenneth Mars, plays Hugh Simon, providing yet one more strangely accented flamboyant nutball to his immense repertoire. A very young Randy Quaid, a brief M. Emmet Walsh and a very annoyed John Hillerman also show up in hilarious bit parts.

All of this anarchy culminates in a spectacular car chase through the streets of San Francisco that actually rivals the one from Bullitt. Apparently it took four weeks to shoot, cost $1 million (¼ of the film's budget) and even managed to get the filmmakers in trouble with the city for destroying some of its property without permission. Nevertheless, Bogdanovich pulls out all the stops in creating this over-the-top action/slapstick set piece that overflows with both thrills and laughs. When watching it, one can't help but be reminded that physical comedy on this grand of a scale doesn't even get attempted anymore. One wishes another director would resurrect the kind of awesome stunt-comedy on display here and in The Pink Panther series.

The film's dénouement takes place in a courtroom where an embittered, elderly judge (the brilliant Liam Dunn) hears the arguments of everyone involved and tries to make sense of it all. Howard's attempt to explain only serves to frustrate and confuse the judge further and results in this gem of an exchange that owes more than a little bit to Abbott & Costello's "Who's on First?":

HOWARD: First, there was this trouble between me and Hugh.

JUDGE: You and me?

HOWARD: No, not you. Hugh.

HUGH: I am Hugh.

JUDGE: You are me?

HUGH: No, I am Hugh.

JUDGE: Stop saying that. [to bailiff] Make him stop saying that!

HUGH: Don't touch me, I'm a doctor.

JUDGE: Of what?

HUGH: Music.

JUDGE: Can you fix a hi-fi?

HUGH: No, sir.

JUDGE: Then shut up!

The tag line for What's Up, Doc? read: "A screwball comedy. Remember them?" Well, whether people remembered screwball comedy or simply discovered it for the first time, they certainly embraced the film as it was an enormous success upon its release. It took in $66 million in North America alone and became the third-highest grossing film of the year. Since The Last Picture Show was released in late '71 and Doc came out in early '72, Bogdanovich had two hugely successful films playing in theaters at the same time. Unfortunately, his career, which had just started to rise, also had neared its peak. Although he would follow Doc with Paper Moon his directing career would only see sporadic critical successes after that such as Saint Jack and Mask. He even filmed Texasville, the sequel to The Last Picture Show, but he'd never again see the kind of commercial or critical success he had achieved in the early 1970s. Bogdanovich would eventually end up working in television, often as an actor such as his long recurring role as Dr. Elliot Kupferberg, psychiatrist to Dr. Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) on The Sopranos. The most recent feature film he directed was 2001's fairly well-received The Cat's Meow starring Kirsten Dunst as Marion Davies and Edward Herrmann as William Randolph Hearst. Based on a play of the same name, The Cat's Meow concerned a real-life mystery in 1924 Hollywood involving the shooting death of writer/producer/director Thomas Ince (Cary Elwes) on Hearst's yacht.

When Bogdanovich was good, he was great and What's Up, Doc? is, in my opinion, the jewel in his crown. It made a once-forgotten genre popular again, it jump-started a lot of comic careers and it reminded us all that love meaning never having to say we're sorry is the dumbest thing we've ever heard.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Abbott and Costello, Bogdanovich, Buck Henry, Cary, Cole Porter, Cybill Shepherd, Dunst, Gable, Hawks, K. Hepburn, L. Kasdan, Mel Brooks, Movie Tributes, R. Quaid, Streisand, The Sopranos, Willis

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, December 09, 2011

Centennial Tributes: Broderick Crawford

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

In 1949, Columbia Pictures brought Robert Penn Warren’s classic novel All the King’s Men to the big screen in an adaptation that deviated a great deal from the source material (as most films are wont to do) but nevertheless made for a compelling movie about idealism and political corruption in telling the tragic story of the rise and fall of a populist demagogue named Willie Stark. In casting the film, director Robert Rossen first offered the role of Stark to John Wayne who — not surprisingly — turned down the part, thinking the script unpatriotic. Rossen then decided upon Broderick Crawford, a burly character actor whose prolific if undistinguished cinematic career was comprised of playing tough guys and Runyonesque hoods in vehicles such as Tight Shoes (1941) and Butch Minds the Baby (1942). The role of Willie Stark fit Crawford like a glove, however; he won an Oscar for his performance in King’s Men beating out the Duke, who also had been nominated that same year for his starring turn in Sands of Iwo Jima.

Crawford’s triumph for All the King’s Men has often acted as a litmus test where Academy Awards are concerned; many film historians and critics argue that the Best Actor Oscar should not have gone to someone whose movie career, with the exception of King’s Men and Born Yesterday (1950), was marked by admittedly one-note performances in B-pictures, alternately playing heroes and villains. Is the purpose of Academy Awards to single out meritorious individual performances, or are they largely recognition for an entire distinguished body of work? I suppose it matters very little in the final analysis, because there are no mulligans when it comes to Oscars: Crawford won his, and in all honesty I think it was most deserved. The actor, who would become one of Hollywood’s most cantankerous character thespians, was born 100 years ago today, and now is good as time as any to see if his stage, screen and television legacy holds up.

Broderick Crawford was born in Philadelphia in 1911 to a second generation of performers, vaudevillians Lester Crawford and Helen Broderick. The latter name is familiar to many classic film buffs that’ve seen the comedienne in such Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers vehicles as Top Hat (1935) and Swing Time (1936). Before her movie career, she and her husband were a successful comedy duo in vaudeville, with an act that occasionally featured their young son in small roles. Brod graduated from the Dean Academy in Franklin, Mass., (where he was a well-regarded athlete) and was accepted at Harvard but his further academic pursuits came to a halt when he dropped out after three months to find work in New York. He became a jack-of-all-trades (longshoreman, seaman, etc.) though eventually the show business bug consumed him and he landed a number of radio jobs in the 1930s; reportedly appearing from time to time on Flywheel, Shyster and Flywheel — the 1932-33 half-hour comedy series starring Groucho and Chico Marx.

With performing in his blood, Broderick made his Broadway debut in 1934 as a football player in She Loves Me Not (he had made his stage debut in the same production in 1932 in London, where his talents attracted the notice of Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, who in turn introduced him to Noel Coward) and later appeared in such productions as Coward’s Point Verlaine, Sweet Mystery of Life and Of Mice and Men. It was for the latter play that Crawford earned exceptional critical acclaim, though when it came time for Hollywood to do its adaptation Brod was overlooked for the part in favor of Lon Chaney, Jr. By that point in his show business career, Crawford had set stage work aside in favor of the movies; his film debut was in the Samuel Goldwyn-produced Woman Chases Man (1937; with Miriam Hopkins and Joel McCrea) and he continued to appear in such B-flicks as Submarine D-1, Undercover Doctor and Eternally Yours. On occasion, Broderick would land roles in “A” productions such as Beau Geste, The Real Glory, Seven Sinners and Slightly Honorable but his rough-hewn manner and less-than-matinee-idol looks (in later years he remarked that his cinematic countenance resembled that of “a retired pugilist”) usually relegated him to character parts in scores of shoot-‘em-up Westerns like The Texas Rangers Ride Again and When the Daltons Rode. He did, however, prove versatile and adept at humorous turns in films like The Black Cat (Brod’s actually one of the “heroes” in this horror comedy, teamed with cinematic toothache Hugh Herbert) and Larceny, Inc.; he supported Edward G. Robinson in this last one as the lunkheaded Jug Martin, who assists Eddie and Ed Brophy in their attempts to rob a bank by purchasing and operating a luggage store next to it. (A decade later, Crawford paid homage to Robinson by re-creating a role that Eddie G. had played in the 1938 crime comedy A Slight Case of Murder but unfortunately, Stop, You’re Killing Me can’t quite measure up to the original.)

Crawford’s film career was interrupted briefly by World War II; he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and while in Europe saw action in the Battle of the Bulge. He later was assigned to the Armed Forces Radio Network in 1944, where as Sergeant Crawford he fell back on his previous radio experience to serve as an announcer for Glenn Miller’s band. Back in Hollywood by 1946, Brod returned to the B-picture grind with occasional bright spots such as Black Angel, The Time of Your Life (as a melancholy policeman) and Night unto Night. His gig in All the King’s Men transformed him into a box-office draw and made him the most unlikely leading man since Wallace Beery; signing a contract with Columbia that same year, he also nabbed the plum role of tyrannical junk tycoon Harry Brock opposite Judy Holliday in Born Yesterday — a part that actor Paul Douglas had played to great acclaim on stage.

Crawford’s brilliant comic turn in Yesterday had an unfortunate side effect in that it earned him enmity from critics who have argued that, for the most part, he played variations of Harry Brock in practically every film in its wake. The success of both King’s Men and Yesterday nevertheless earned him considerable cache to appear in “A” productions such as Night People (1954) and Not as a Stranger (1955) —the latter film once described by one critic as “the worst film with the best cast.” His turn as Capt. “Waco” Grimes in Between Heaven and Hell (1956) features some of his best work, and his approach to the character may remind you of Col. Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. That same year, he surprised critics again by scoring as a petty thief seeking redemption in Federico Fellini’s Il Bidone.

Truth be told, Crawford worked his magic best as a screen heavy; he appeared as a formidable villain against Clark Gable in 1952’s Lone Star, and particularly shone in film noirs such as Big House, U.S.A. and New York Confidential (both 1955). One of his best showcases in that style was in 1952’s Scandal Sheet, a film directed by Phil Karlson (based on a novel by Sam Fuller) in which he plays a tyrannical tabloid editor who assigns his star reporter (John Derek, who had played son Tom Stark in King’s Men) to investigate a sensationalistic murder knowing full well that he is the guilty party. Scandal Sheet bears a strong resemblance to the earlier The Big Clock (1948) — in which powerful magazine magnate Charles Laughton tries to frame editor Ray Milland for a murder Charlie committed — but while Crawford was certainly not in Laughton’s league watching him sweat bullets as the noose tightens around his neck during Derek and girlfriend Donna Reed’s relentless investigation is certainly worth the price of admission.

Crawford also headlined another underrated noir entitled The Mob (1951); as undercover cop Johnny Damico, Crawford sets out to find a hit man while exposing corruption in the waterfront rackets — Mob has some memorably snappy dialogue in addition to its first-rate supporting cast (Richard Kiley, Ernest Borgnine, Neville Brand) though I will admit Brod seems more like the guy who’d be running the waterfront in the first place. Other standout noirs with Crawford include Down Three Dark Streets (1954), in which he plays a stalwart FBI agent, and Human Desire (also 1954), a Fritz Lang-directed remake of Jean Renoir's La Bête Humaine that cast him as the cuckolded husband in a torrid love affair between wife Gloria Grahame and co-worker Glenn Ford. (Crawford’s husband in Desire is a truly pitiful soul who earns the audience’s sympathy because Gloria, not to put too fine a point on it, is a real bitch.)

Ford and Crawford squared off again two years later in an underrated Western that’s been a longtime favorite of mine, The Fastest Gun Alive. Brod is the loathsome Vinnie Harold, a gun-toting bully compelled to challenge any individual who’s acquired a reputation as a fast gun. When he arrives in a town where shopkeeper Ford’s prowess with a firearm is being kept under wraps by the populace (they’re afraid that Glenn’s rep will draw every gunslinger in for miles around…and they were pretty much right), he and his men (John Dehner, Noah Beery, Jr.) threaten to set the burg ablaze unless they identify Ford. A great psychological oater, Fastest Gun stands out among the many Westerns Crawford appeared in at that time, which included such films as Last of the Comanches and The Last Posse (both 1953).