Sunday, February 02, 2014

Philip Seymour Hoffman (1967-2014)

Boogie Nights marked Hoffman's second film with Anderson following Hard Eight. They would team again in Magnolia, Punch-Drunk Love and The Master, which earned Hoffman an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor, his fourth overall. He also received supporting nods for Doubt and Charlie Wilson's War and won on his first try, his only nomination in the lead category, for Capote.

Though his film career only began in 1991, it proved to prolific. Once his fame and reliability grew, even if some of the films he appeared in weren't so great, I never saw him give a bad performance. A cattle call of some of my favorite Hoffman performances: Happiness, The Talented Mr. Ripley, 25th Hour, The Savages, Before the Devil Knows You're Dead, Moneyball and The Ides of March.

The performance perhaps closest to my heart was his turn as legendary rock journalist Lester Bangs in Cameron Crowe's Almost Famous. I also loved his work in two less well-known films: Owning Mahowny and Jack Goes Boating, a role he originated in the off-Broadway production and he also directed the film.

He appeared on Broadway three times and received a Tony nomination each time. His first came in the inaugural Broadway production of Sam Shepard's True West, where he and John C. Reilly alternated the lead roles at different performances. He earned a featured actor nod in the star-studded, highly praised revival of O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night starring Brian Dennehy and Vanessa Redgrave. His third nomination came for taking on Willy Loman in a revival of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman.

RIP Mr. Hoffman.

Tweet

Labels: Arthur Miller, O'Neill, Obituary, Oscars, P.S. Hoffman, Shepard, Theater, Vanessa Redgrave

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, January 12, 2014

Love Hurts

Why do we always hurt the ones we love?

Anyone who’s been a part of any kind of significant relationship, whether of the familial or romantic variety, has been given to ponder the paradoxical nature of those thorny, forged-in-fire entanglements. As evidenced by the brutal, bruising verbal brickbats the family members of August: Osage County lob at each other’s heads like hand grenades, no one can inflict quite as much damage as one’s nearest and dearest. This axiom may be most commonly applied in reference to human interaction, but it holds equally true when considering a writer and his work.

Anyone who’s ever put pen to paper — or, in this modern age, spent hours staring at a blinking monitor — knows that the peculiar bond between a scribe and his prose can be as complex and as intimate as that of any of the human variety. Many playwrights and novelists have likened their labors to the birthing process, and discuss their work in the same way that parents talk about their children. By that definition, writers who do harm to their own creations can be charged — at least, on some metaphysical plane — with child abuse.

This is not to cast aspersions on the character of Tracy Letts, who has adapted his Pulitzer Prize-winning play for the screen, and whom I suspect is only minimally to blame for what has happened to it (nothing good) en route. Still and all, it begs the eternal question: Why do we hurt the ones we love? As far as selling a book or a play to the movies is concerned, nine times out of ten, the road to perdition is paved with good intentions.

Rather than veering too far off course into the realm of psychoanalytic introspection, it may be best to consider the history of the property in question. August: Osage County premiered in the summer of 2007 at The Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago. The production subsequently moved to Broadway in the fall of 2008, with most of its original cast intact. It remained ensconced on The Beltway for a year and a half — a rare feat for a non-musical production not featuring a movie or TV star — picking up virtually every major award along the way. I saw the production three times over the course of its run — anyone familiar with Broadway pricing will recognize that this represents a sacrifice — and reviewed it for this site in 2009. It is not an overstatement to say that, then as now, I regard it as one of the highlights of my life’s theatergoing experience. Admittedly, I am not the ideal person to review the film adaptation, since I cannot approach the material with any kind of objectivity. Nor would I want to. Even if it’s a fundamental part of our nature to hurt the ones we love, it doesn’t follow that we enjoy doing it.

Nevertheless, when the owner and proprietor of this blog calls me up for active duty, I do my best to answer the call. In interest of full disclosure, I must state that while I tried to approach the assignment with an open mind, personal prejudice (did I mention how much I loved the show on Broadway?) has gotten the better of me to some degree. Oddly enough, without that pre-existing prejudice, my response toward the film might have been even less felicitous than it is now.

It’s bad form when reviewers reference other critics’ opinions to reinforce and/or validate their own position. The mere act of doing so suggests lack of confidence in one’s opinion. That said, one of the things I’ve been struck (and depressed) by is the manner in which many non-theatergoing critics have suggested, based solely on their reaction to the film version, that August: Osage County is not, and in fact never could have been, much of a play. The critic for The New York Times, while allowing that that the material may have been “mishandled…(in its) transition from stage to screen,” pondered whether that transition may have “exposed weak spots in (Letts’) dramatic architecture and bald spots in his writing.” On the opposite coast, the scribe for The Los Angeles Times took it a step further in declaring that while he had not seem the stage incarnation, “nothing about this film version makes me regret that choice.”

I suspect many people on the receiving end of years’ worth of glowing testimonials will react in much the same fashion. Anyone experiencing director John Wells’ hamfisted, ultimately rather conventional Hollywood treatment of family dysfunction without a suitable frame of reference may well be given to wonder, “Is this what all the fuss was about?” Advance reports suggested that the filmmakers made a deliberate effort to brighten things up, even going so far as to tack on a happy ending. That’s not the case. While truncated, the play has not been radically revised. In a certain sense, that’s good news. The bad news is that fundamental fidelity to the text doesn’t bring this baby snugly into port. You could rewrite every line and still arrive at something that felt closer in spirit and purpose to what Letts created for the stage than what Wells and company have come up with. As played for cozy camp by a cast of Hollywood heavyweights, the material has not been softened as much as it has been neutered.

For a sharp-fanged predator used to trolling the wild with confidence, this has an effect of bland domestication, despite the fact that its path through the jungle remains essentially the same. What sets the plot in motion is the mysterious disappearance of Beverly Weston (Sam Shepard), the craggy, alcoholic patriarch of an extended clan that includes three daughters, one grandchild and an assortment of in-laws. A noted poet whose output didn’t extend beyond one fledgling success, Beverly has a habit of going missing without so much a heads up to his nearest and dearest. This time, however, his absence has an unmistakable air of finality. No one can be quite certain whether he’s alive or dead, but the likelihood of his coming back seems slim to none. One by one, the far-flung Weston children, two of whom have wisely chosen to get themselves as far away from Mom and Dad as humanly possible, descend upon the family homestead en masse to try to piece together exactly what happened to Dad, and what in hell to do about mother Violet (Meryl Streep), a chain-smoking, pill-popping, cancer-riddled gorgon who shows no signs of becoming more manageable now that her chief antagonist has vanished without a trace. Leading the charge is pragmatic, sardonic Barbara (Julia Roberts, keeping that million-dollar smile firmly under wraps), who isn’t about to let Mom off the hook without answering a few questions. Of course, when you start digging for the truth, there’s no telling what sort horrors you may uncover. As it turns out, there are good and plenty festering away in the crypt of family secrets, and Violet is perfectly willing to invite them out to dance.

Even as I lavished praise upon the play and the production in my original review, I did so with the caveat that August: Osage County was not a revolutionary work of theater, nor even a particularly original one. Borrowing liberally from Eugene O’Neill, Lillian Hellman and Sam Shepard, among others, the play harks back to the classic traditions of American drama while reinvigorating the tried-and-true machinery of melodrama with brazen, jolting theatricality. The chief mistake Wells has made for the purposes of the film version – besides some critically misjudged casting choices — is in his confusion of theatricality with camp. He encourages his cast members to go for the easy laughs whenever they can, and irons out the characters’ idiosyncrasies to the point that their behavior seems almost quaint. When Violet and Barbara literally come to blows in the climatic dinner table scene, it’s like watching Joan Collins and Linda Evans wrestling on the marble foyer at Carrington Manor. It’s outrageous, to be sure, but not particularly shocking. Without the emotional resonance that original stage players Deanna Dunagan and Amy Morton brought to the proceedings, under the skillful direction of Anna D. Shapiro, what you’re left with feels more along the lines of a live action cartoon.

While the sins of the director shouldn't be heaped at feet of the playwright, Letts' screenplay adaptation doesn’t help matters much. The clunky efforts at opening up the piece for the screen, taking the action out of doors at select intervals, never feel like an organic extension of the action. The element of claustrophobia that contributed so much to the proceedings onstage, in the rambling Pawhuska, Okla., farmhouse with its shades drawn tight to keep out light and air, has been jettisoned in favor of woebegone glimpses of parched prairies. Certain nuances inevitably fall by the wayside when condensing a 3 hour play into a 2 hour film, and while the cuts do not fundamentally alter the dramatic structure, the action occasionally feels rushed, as if the filmmakers were working on a limited budget and needed to hit all the major plot points before running out of film stock. Some characters have been whittled down to near non-existence (the Native American housekeeper, here played by Misty Upham, has been reduced to a virtual extra), while the participation of others has been severely curtailed so as not to distract from the main event of the Streep-Roberts smackdown.

About that smackdown. Judging by the posters for the film, which flaunt a scrunch-faced, teeth-baring Ms. Roberts wrestling a very harassed-looking Ms. Streep to the ground, the battle royal between two living legends already has been designated as the chief selling point for this film. I won’t argue the point. The tattered Baby Jane template still has some blood coursing through its skeletal remains, and I suspect it isn’t just camp-starved audiences who will pony up the cash to see the two biggest female stars of their respective generations going at each other like a pair of fabulously plumed Japanese fighting fish. Both actresses seem to have taken their cues from that WWE poster aesthetic, and while the ham they serve up may be to many people’s taste, the meal as a whole is less than nourishing.

At this point, we’re really not supposed to say anything bad about Meryl Streep, since certain things are to be accepted without questioning. Remember that thing they taught us in school about Democracy being the best form of government? Well, even if a few dozen Tea Party crackpots can force a complete shutdown of the entire federal shebang, you can’t fault the model, God dammit. Likewise, I’ve discovered that in certain quarters, if you broach any contradiction to the edict that Meryl Streep is The Greatest Actress Who Ever Was, people will react as if you said something bad about America. I’ve spoken this blasphemy before, and I’ve been unfriended on Facebook for doing it. I’m not exactly sure why certain folks seem to have so little sense of proportion when it comes to Our Lady of the Accents, but this is not to imply that their insistence upon her genius is entirely lacking in merit. Ms. Streep is unquestionably great. She has given some of the best and most memorable performances of the last 30-odd years. That her talent level is through the roof, residing somewhere in the stratosphere, is beyond reproof. I suspect she’s abundantly aware of this.

It isn’t that Streep has become complacent as a performer; she doesn’t just coast on her abilities, though at times, she seems to be responding more to her characters as Great Acting Opportunities than as flesh-and-blood human beings. By default, she is undoubtedly the best thing in August: Osage County. Her performance is the most finely honed and easily the most convincing of the bunch, even if the favored mannerisms and inflections are starting to look so precise and polished that they might as well be kept under glass at Tiffany’s. Where the performance loses credibility (and probably, this is the director’s fault as much as hers) is in her rendering of Violet as a lip-smacking Diva turn. Part of the fun of watching Deanna Dunagan onstage was the slow reveal of Violet’s true nature; behind the drug-induced haze and tortured insecurities lie an ineffably shrewd, twisted, Machiavellian mind, sharp as a tack and ready to do battle. By contrast, Streep takes to the screen like she’s warming up to play Eleanor of Aquitaine. When it’s crystal clear from the outset exactly who’s pulling the strings, a vital element of suspense is lost. Frankly, given who’s she up against, it isn’t as though she has much in the way of competition, anyway.

Lest anyone misunderstand my intentions, I must duly assert that I am not a snob when it comes to acting pedigree. Range and/or skill set, whether acquired by classical or method training, does not necessarily place one person on a higher pedestal than anyone else. Talent is talent, and I’ve always had a soft spot for performers who can make assembly-line crap compulsively watchable by sheer force of personality. Julia Roberts has her limitations as an actor, and her fair share of detractors (and boy, are they emphatic), but she’s also given some of the great movie star performances of her era. It’s not a knock on Audrey Hepburn to say that she probably didn’t have the chops for Albee, or that Barbra Streisand might have been absolutely disastrous in Pinter. Nor should it be perceived as a negative reflection on Ms. Roberts to say that what is required of her in this context is simply beyond her abilities. Unfortunately, that negative balance takes a lot of the charge out of the material, and gives the mother-daughter skirmish the appearance of a lopsided battle.

On stage, Amy Morton’s cornhusk-dry delivery, powerful physicality and searing emotional transparency went a long way towards revealing the deep reserves of anger and pain which informed Barbara’s metamorphosis from defeated, resentful onlooker to fully engaged combatant. While Barbara is nominally the protagonist, she’s not really the hero. That she is very much her mother’s daughter, as damaged and damaging as Violet and with the same capacity for unleashing icy torrents of cold, hard fury, is made abundantly clear as soon as Mama starts turning up the heat. You have to believe, as one character asserts, that in spite of surface appearances, there’s “no difference” between the two. Roberts endeavors diligently to embody the complexities and contradictions of the role, but going to the dark places is not the most comfortable place to be when one has made a career out of flooding the screen with sunshine. She overcompensates by punching up her sassy, feisty Erin Brockovich shtick, but what worked like gangbusters in a miniskirt and push-up-bra does not here dimension make. It’s an uncharacteristically flat, colorless performance. There’s never any risk of Barbara turning into her mother, not does it ever seems as though she is willing or able to take Violet to the mats.

No one else meandering through the din makes much of an impression, although a few of the performers — notably Chris Cooper, Margo Martindale and Juliette Lewis, who brings some nice flashes of hysteria to her marginalized role as the most clueless and least functional of the three sisters — are at least better suited to the material. While Benedict Cumberbatch has carved out a nice niche for himself in recent years as the thinking girl’s sex symbol, and Ewan McGregor likely will remain boyishly handsome well into his 60s, their presence here as, respectively, a sad-sack, slow-witted underachiever and an unprepossessing middle-age college professor, defies all measure of reason. Julianne Nicholson, Dermot Mulroney and Abigail Breslin are among those also caught in the cross-hairs, although everyone not named Meryl or Julia is essentially treated as window-dressing. While it’s something we’ve come to expect of the movies, casting so many extremely photogenic performers was probably a mistake. Quiet desperation, romantic neglect and midlife crisis have never looked more red-carpet-ready.

That red carpet will doubtless unfurl in the months to come for at least one member, and possibly more, of August: Osage County’s creative team. Tracy Letts may reap some of the rewards for his contribution here. Of course, nominations are nice, and so is the money…but reading between the lines of the playwright’s recent comments to The New York Times, he’s not entirely satisfied with the finished product. A writer’s life is one of compromise when the camera comes into the picture, and based on Letts’ statements, he probably realized that trying to maintain too much control over the film version would have been fighting a losing battle. At least, by doing the adaptation himself, he could still score a few points and protect some of what needed to be preserved. Why do we hurt the ones we love? If August: Osage County is any indication, the answer may be to prevent others from hurting them instead.

Tweet

Labels: 10s, A. Hepburn, Albee, Chris Cooper, Ewan McGregor, Harold Pinter, Julia Roberts, O'Neill, Shepard, Streep, Streisand, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, February 03, 2012

Ben Gazzara (1930-2012)

We've lost yet another of the unofficial John Cassavetes repertory company with the news that the great Ben Gazzara lost his battle with pancreatic cancer Friday at the age of 81. Gazzara left his mark on stage, screen and television throughout his long career and never abandoned his taste for taking risks beyond the works of Cassavetes, who directed Gazzara in three films and co-starred with him in two movies directed by others, eventually appearing in films by directors such as David Mamet, Vincent Gallo, the Coen brothers, Todd Solondz, Spike Lee, Lars von Trier and Gérard Depardieu.

A native Manhattanite from a working class family, once the acting bug bit Gazzara, he studied under Lee Strasberg at The Actors Studio. He made his Broadway debut in 1953 in Calder Willingham's adaptation of his own novel End as a Man which earned Gazzara a 1954 Theater World Award. In March 1955, he created the role of Brick in the original production of Tennessee Williams' Cat on a Hot Tin Roof under Elia Kazan's direction. Barbara Bel Geddes had the role of the original Maggie and Burl Ives put his mark on Big Daddy. Only Ives and Madeleine Sherwood as sister woman Mae made the leap to the 1958 movie version. Though the Pulitzer Prize-winning play was a huge hit, Gazzara departed it later in 1955 to take the lead role of Johnny Pope in A Hatful or Rain written by Michael V. Gazzo, who movie buffs undoubtedly know better as Frankie Pentageli in The Godfather Part II. The play concerned a Korean War veteran who came home addicted to morphine and how it tore his family apart, It earned Gazzara his first Tony nomination as lead actor and co-star Anthony Franciosa a nomination as featured actor as his younger brother. When it was made into a film in 1957, Don Murray got to play Johnny though Franciosa kept his part and earned an Oscar nomination in the lead category. Gazzara's final Broadway appearance in the 1950s was a gigantic flop. The Night Circus also was written by Gazzo, but it closed after seven performances. It did co-star Janice Rule, who Gazzara would wed in 1961. For the remainder of his New York stage career, he would receive two more Tony nominations (but never a win). One for playing George to Colleen Dewhurst's Martha in a revival of Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, the other for an evening of paired one acts: Eugene O'Neill's Hughie and David Scott Milton's Duet. In 2004, he received a Drama Desk nomination for solo performance for his off-Broadway play Nobody Don't Like Yogi about baseball legend Yogi Berra, which he took on tour. He received a 2006 Drama Desk Award as part of the winning ensemble for the Broadway revival of Clifford Odets' Awake and Sing!, his last stage appearance.

Concurrent to his stage work in the 1950s, Gazzara appeared frequently on television, almost exclusively on the many live theater programs that originated from New York, though some episodic appearances pre-date his Broadway debut and stretch back to 1952 on series such as Treasury Men in Action, Danger and Justice. He didn't make his film debut until 1957 in The Strange One, which is the title they gave to a reworked version of the play End as a Man with many of the original Broadway cast repeating roles along with Gazzara including Pat Hingle, Peter Mark Richman (not using the Peter yet), Paul E. Richards and Arthur Storch. His second film in 1959 though is one of his works that will keep his memory alive as the defendant in Otto Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder starring James Stewart. The film still plays well today, though it's hardly as daring now as it was in its original release. While Gazzara always bounced between the three mediums, his only regular roles on series took place in the 1960s. First, as Det. Sgt. Nick Anderson on the 30 episodes of Arrest and Trial from 1963-1964, then as Paul Bryan in the far-more-successful Run for Your Life which aired from 1965=1968 and earned him two Emmy nominations as outstanding lead actor in a drama series. He also was nominated in 1986 for the lead actor in the TV movie An Early Frost and won as supporting actor in a TV movie for the 2002 HBO film Hysterical Blindness.

Gazzara never stopped working and if I attempted to be comprehensive, I'd never finish this. It would be impossible to have seen everything he has made — I imagine even he never saw all of his films. I never realized how many movies he made in Italy. In The New York Times obit, it quotes a 1994 interview he gave to Cigar Aficionado magazine about those movies where he said, “You go where they love you.” So, forgive any omissions, because I'm finishing this fast.

You always want to start with the Cassavetes trilogy: Husbands, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie and Opening Night and how those working friendships spread to other projects such as Gazzara directing Husbands co-star Peter Falk in two episodes of Columbo and, many decades later Cassavetes' widow Gena Rowlands wrote a short film for her and Gazzara to star in that Gérard Depardieu directed as part of Paris, je t'aime . There was the incredibly goofy Patrick Swayze vehicle Road House where Gazzara played the bad guy, but he portrayed Brad Wesley in such a damn entertaining way you kept forgetting that he was the one you were supposed to be rooting against. His mysterious Mr. Klein, one of the many puzzling characters in David Mamet's puzzle picture The Spanish Prisoner. The magnificent duet of dysfunction that he and Anjelica Huston performed in Vincent Gallo's Buffalo '66. The neighborhood boss trying to play peacekeeper and vigilante at the same time in Spike Lee's Summer of Sam. Then he was part of the quirky ensembles that made up Todd Solondz's Happiness and the Coens' Big Lebowski.

Gazzara lived to take chances and loved to work and he did both about as well as anyone. RIP Mr. Gazzara.

Tweet

Labels: A. Huston, Albee, Awards, Cassavetes, Coens, Falk, J. Stewart, Kazan, Mamet, O'Neill, Obituary, Preminger, Spike Lee, Tennessee Williams, von Trier

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, December 04, 2011

Re-fighting the Cold War

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This piece originally posted Jan. 3, 2007. I'm re-running it today to mark the 30th anniversary of the release of the movie Reds.

By Edward Copeland

It was with trepidation that I decided to use the occasion of its 25th anniversary DVD release to face off again with one of my old cinematic archenemies, namely Warren Beatty's 1981 film Reds. I'd known for a long time this day would come because through those two-and-a-half decades, I'd carried the scars of enduring the film and it had remained as one of the most boredom-inducing experiences of my filmgoing life. However, I also knew that it probably wasn't fair to the film. I saw Reds in its initial release — when my Oscar obsession was blossoming in seventh grade and deep down, I knew that perhaps a 12-year-old wasn't the movie's ideal audience and I needed to give the film another chance, to watch it with fresh, adult eyes.

Could the Reds I watched again in 2006 possibly be the same Reds that felt like as if a dentist were performing a root canal on me when I saw it decades ago — or is the real truth that the film remains the same but I'm not a different moviewatcher than I was back then? I think the answer is clear — and it would probably be plain stubborness on my part not to acknowledge that conditions must truly be correct for an individual to appreciate some films and a three hour-plus account of early socialists and the Russian revolution isn't really the best material for someone who at the time worshipped the reels Raiders of the Lost Ark unspooled from, especially since over the years Raiders has diminished in my eyes. Re-watching Reds, which initially to me seemed to move slower than Heinz ketchup, surprised the hell out of me when I realized that its pacing seemed exceptional for such a long movie. Sure, no Nazi faces were melting, but Reds' richness finally has become apparent to me. It's also worth noting that in the period between my initial seventh-grade viewing of Reds and my second encounter in 2006, one of my favorite courses at college was called Era of Russian Revolutions.

In many ways, Reds not only plays as a great film to me today in a way it didn't back in the 1980s, it also works as a far more relevant one as well. When you watch as the idealism of those who felt socialism was the answer to capitalism's wrongs inevitably gives way to cynicism as the communists in Russia begin using their power to deny the people rather than to give them a stronger voice, it's hard not

to see the parallels. Ideology by necessity almost always gives way to disillusionment as true believers, no matter where they fall on the political spectrum, realize that the people whom they've trusted and believed in to realize their ideal dreams either have something else in mind or lack the essential ability to implement their goals. Reds also plays more clearly to me today as a story of the battle between art and politics as Jack Reed (Beatty) tries to balance his love of writing with his political sensibilities. He wants to help fight for his cause, but he still bristles when anyone tries to change his words. Deep down, even if he didn't admit it, he was more writer than revolutionary. Of course, the love that really lies at the heart of Reds is that between Reed and Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton). Keaton's performance resonates much more strongly for me now than it did when I was a bored adolescent. Perhaps, as much as I love Annie Hall, this might be Keaton's best performance as an often-fickle woman whose political views often drift as often as her interest in the men in her life. One of the things that annoyed me the most in junior high were the witness scenes, where the talking heads against the black backgrounds recounted their experiences with Reed and Bryant. I never appreciated the contradictions their stories presented at the time, but they shine through now, especially in the case of Bryant who remains a bit of an enigma.

to see the parallels. Ideology by necessity almost always gives way to disillusionment as true believers, no matter where they fall on the political spectrum, realize that the people whom they've trusted and believed in to realize their ideal dreams either have something else in mind or lack the essential ability to implement their goals. Reds also plays more clearly to me today as a story of the battle between art and politics as Jack Reed (Beatty) tries to balance his love of writing with his political sensibilities. He wants to help fight for his cause, but he still bristles when anyone tries to change his words. Deep down, even if he didn't admit it, he was more writer than revolutionary. Of course, the love that really lies at the heart of Reds is that between Reed and Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton). Keaton's performance resonates much more strongly for me now than it did when I was a bored adolescent. Perhaps, as much as I love Annie Hall, this might be Keaton's best performance as an often-fickle woman whose political views often drift as often as her interest in the men in her life. One of the things that annoyed me the most in junior high were the witness scenes, where the talking heads against the black backgrounds recounted their experiences with Reed and Bryant. I never appreciated the contradictions their stories presented at the time, but they shine through now, especially in the case of Bryant who remains a bit of an enigma.

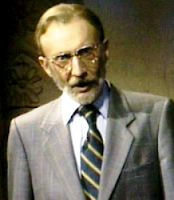

Keaton hardly is the only actor who comes off even better than I remember from my first viewing. While Oscar winner Maureen Stapleton was my favorite part of the movie at the time, her great work as Emma Goldman actually is a much smaller role than I recalled. The other performance that plays even better now than it did

then is Jack Nicholson's work as Louise's sometime lover, playwright Eugene O'Neill. It may well be Nicholson's most quiet and reserved work on film ever. I love Jack — and I love when he goes over the top, but there isn't any sign of that Nicholson here. Nicholson's O'Neill is smart, quiet and bitter over his treatment by Louise though still willing to help her in a pinch when she needs it. In the featurettes included on the 25th anniversary DVD, Nicholson recalls asking Beatty why he wanted him for this part and Beatty replied that he wanted someone who could conceivably steal Louise from Jack Reed and Nicholson certainly fills that bill. As for Beatty's work, you almost have to divide it into the four roles he served on the film. As producer, getting Reds made truly seems an impressive accomplishment in hindsight. As co-writer with Trevor Griffiths, his script plays much better than it did for the 12-year-old Edward Copeland. As director, his Oscar win seems deserved to me now, though I might still opt for Spielberg's work on Raiders in a pinch.

then is Jack Nicholson's work as Louise's sometime lover, playwright Eugene O'Neill. It may well be Nicholson's most quiet and reserved work on film ever. I love Jack — and I love when he goes over the top, but there isn't any sign of that Nicholson here. Nicholson's O'Neill is smart, quiet and bitter over his treatment by Louise though still willing to help her in a pinch when she needs it. In the featurettes included on the 25th anniversary DVD, Nicholson recalls asking Beatty why he wanted him for this part and Beatty replied that he wanted someone who could conceivably steal Louise from Jack Reed and Nicholson certainly fills that bill. As for Beatty's work, you almost have to divide it into the four roles he served on the film. As producer, getting Reds made truly seems an impressive accomplishment in hindsight. As co-writer with Trevor Griffiths, his script plays much better than it did for the 12-year-old Edward Copeland. As director, his Oscar win seems deserved to me now, though I might still opt for Spielberg's work on Raiders in a pinch.

Then there is Beatty the actor. Beatty is never bad, but when you really get down to it, most of his performances come off sounding like the same person. The exceptions would be his earlier work as Clyde Barrow for Arthur Penn in Bonnie and Clyde and especially as John McCabe for Robert Altman in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Close your eyes and listen to Heaven Can Wait's Joe Pendleton, Reds' Jack Reed or Bugsy's Bugsy Siegel, and aside from subject matter, they all sound the same. Even Bulworth to some extent falls prey to this. Perhaps it has something to do with when Beatty directs himself, even though Buck Henry co-directed him in Heaven Can Wait and Barry Levinson helmed Bugsy. Beatty reminds me much of Robert Redford — more star than actor. His range is limited and his directing output has been so scarce, I can't help but wonder if he'd moved more toward Clint Eastwood's later career and did less work in front of the camera and more behind, his film reputation might be held in higher esteem.

Reds as a whole plays as such a great movie to me now (even at 12, I recognized how great Oscar-winning Vittorio Storaro's cinematography was, though it's embarrassing to admit that I wasn't familiar with the movie's composer, a man named Sondheim), and Beatty's role in its success is so essential, that I won't begrudge him scoring high in only three of his four jobs on the film. Critics don't like to admit they were wrong — but I was, but at least I can blame it on my young age at the time. In one of the anecdotes on the great featurettes on the DVD, Beatty admits that when he offered to show Reds to his 13-year-old daughter she seemed completely disinterested, though he claims she saw it and liked it anyway, but would a young teen really want to tell her famous father what she really thought? Besides, even if she were lying, she likely will grow to admire it as she ages.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Altman, Arthur Penn, B. Levinson, Buck Henry, Diane Keaton, Eastwood, Nicholson, O'Neill, Oscars, Redford, Sondheim, Spielberg, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

The twilight of an extraordinary life

By Edward Copeland

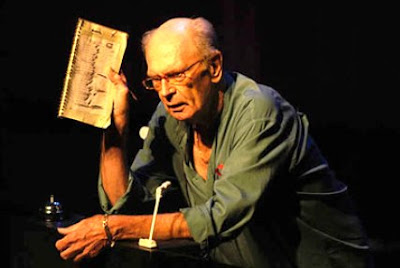

When Charles Nelson Reilly died in 2007, the percentage of people who knew who he was by name, unfortunately, already had fallen precipitously. Thankfully, in the final years of his life the theater actor turned game show fixture had developed and toured in a solo show about his life called Save It for the Stage. Even though Reilly had stopped touring with the show, The Life of Reilly's co-directors Frank L. Anderson and Barry Polterman talked him into performing it one more time in October 2004 so they could film it. As a result, they made this film record of Reilly's remarkable story as only he could tell it.

As title cards explain at the film's opening, the solo show evolved from a talk Reilly was asked to give in 1999. He didn't have anything planned and spoke extemporaneously for more than three hours, enjoying the hell out of it. After that experience, he worked with actor Paul Linke to pare down the show into a more compact running time and Save It for the Stage was born.

While the version of the solo show captured in The Life of Reilly runs half the time that original three-hour speech did, I imagine Reilly would hold your interest at the longer running time based on the nonstop cyclone

of energy he becomes as he shares an oral autobiography, beginning with his birth on Jan. 13, 1931, in The Bronx, and the difficulties growing up with his eccentric family, particularly his bigoted mother who was prone to say things such as "I should have thrown away the baby and kept the afterbirth." (She gave the stage show its name because any time young Charles would go on about something, she'd tell him to "Save it for the stage.") He was more enamored with his father who was a commercial artist, drawing beautiful color advertisements. Young Charles struggled in school, not realizing that his problem was his eyesight, not his intelligence, but he always was imaginative from an early age. A particularly poignant portion of the film comes when he describes his mom taking him to his first movie at the Loews Paradise and how he felt "so safe and warm" sitting there in the dark, gazing at those images.

of energy he becomes as he shares an oral autobiography, beginning with his birth on Jan. 13, 1931, in The Bronx, and the difficulties growing up with his eccentric family, particularly his bigoted mother who was prone to say things such as "I should have thrown away the baby and kept the afterbirth." (She gave the stage show its name because any time young Charles would go on about something, she'd tell him to "Save it for the stage.") He was more enamored with his father who was a commercial artist, drawing beautiful color advertisements. Young Charles struggled in school, not realizing that his problem was his eyesight, not his intelligence, but he always was imaginative from an early age. A particularly poignant portion of the film comes when he describes his mom taking him to his first movie at the Loews Paradise and how he felt "so safe and warm" sitting there in the dark, gazing at those images.Reilly's first taste of acting came in fourth grade when his teacher offered young Charles the role of Columbus in a class play. His mother was resistant, saying he'd never learn the lines because of his difficulties (still denying that eyesight was the problem) but the teacher talked her into it and his acting career was born in P.S. 53. Around the same time young Mr. Reilly received an opportunity, the elder Mr. Reilly missed a big one.

An artist who worked in black and white fell in love with his father's color artwork and urged him to go to California with him, but Reilly's mother nixed the move because all her relatives were on the East Coast. The man's name was Walt Disney. Soon, advertising turned more to photographs than illustrations and Reilly's father was thrown out of work and into alcoholism and eventually institutionalized, forcing young Charles and his mother to move to Hanover, Conn., to live with his uncle, aunt and grandparents, Swedish immigrants who spoke no English. Eventually, his father rejoined them and his aunt, who had her own problems, agreed to try a new medical procedure: a lobotomy. Though Reilly never dwells on his homosexuality, he tells how the neighbors to that household said that he was a "little odd."

"How do you think I felt being the odd one in that family?" he asks, adding that Eugene O'Neill wouldn't come near that house and that he spent his adolescence in an Ingmar Bergman film. However, he reminds his audience what Mark Twain said about laughter being the same in every language. Reilly's ability to tell these stories, some of them horrifying, and still be able to wring laughs from theatergoers was a great gift indeed and as he set out to act for a living in 1950, his tales of theater and show business prove even more entertaining.

A particularly astounding portion is when he discusses the acting class he attended taught by Uta Hagen at HB Studio, the school she founded with her husband Herbert Berghof. The cost was $3 a week. He reads the roll of his 11 a.m. Tuesday class and it's amazing because every name would achieve success, fame and accolades. Here is the list, minus Reilly, alphabetically:

As Reilly tells it, they all had three things in common: "We wanted to be on stage, none of us had any money and we COULDN'T ACT FOR SHIT!" Reilly adds that if they saw McQueen and Holbrook act out a scene as Biff and Happy Loman from Death of a Salesman one more time, "You'd go out of your fucking mind." He does make the point that people who wanted to act back then actually studied, something not as common as it used to be. By my count, this class (to date) has earned nine Tony Awards out of 30 nominations (11 out of 32 if you toss in Uta Hagen's two wins), six Oscars out of 16 nominations and 11 Emmys out of a whopping 61 nominations. Charles Nelson Reilly himself accounts for a Tony for featured actor in a musical as Bud Frump in the original production of Frank Loesser's How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, a nomination as Cornelius in the original Hello, Dolly! and a nomination for directing the revival of The Gin Game that starred Julie Harris and Charles Durning. Reilly earned three Emmy nominations: for The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, a guest shot on The Drew Carey Show and for reprising the Jose Chung character he created on The X-Files on an episode of Millennium.

As with all struggling actors in New York since the beginning of time, Reilly needed work to pay the bills until he started landing paying parts in production. He was excited when a female friend who worked at NBC got him a meeting with the possibility of on-air work. Reilly arrived and met Vincent J. Donahue, the NBC chief at the time, who dismissively sent him away telling him, "We don't put queers on television." Reilly admits that as hateful as that comment was, it rolled off his back. Words like that didn't bother him as much as coming home to find roaches in his Minute Rice. Though he eventually became somewhat of a gay icon, none of the autobiographical show deals with the difficulties of being a gay actor except for that anecdote and there is no mention of a romantic life. Reilly considered himself an actor first — his sexual orientation was just another aspect his life, just like his bad eyesight. Both were parts of him, but neither defined him.

Reilly lived and breathed theater and that is what he wanted to share with the audiences who came to his shows — the upbringing that got him to that point and how it always was an integral part of his life, even after he became better known for kids' TV shows and Match Game. In 1954, he appeared in 22 off-Broadway shows. His Broadway debut came, ironically, as an understudy for another actor who became a gay icon and game show staple — Paul Lynde. Lynde had to be out of Bye Bye Birdie every Thursday night because of a contract to appear on The Perry Como Show, so Reilly took his place once a week. Eventually, he also got to be Dick Van Dyke's understudy in the musical.

He discusses how his close friendship with Burt Reynolds began in New York when Reynolds was a struggling actor and then decades later, when Reynolds built his theater in Jupiter, Fla., he attached an acting school and gave Reilly a beach house to live in so he would teach.

He talks about his times in Hollywood, especially how much he enjoyed being on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson where he was a guest more than 100 times. He talks about one particular time when another guest was a woman who ran a Shakespeare in the Park program in Ohio and he said something and she responded, quite snootily, "What would someone like you know about Shakespeare?" Then he showed her.

Before he taught in Florida, he would teach acting back at that old HB Studio and in a story that particularly cracked me up because it reminded me of my days of both attending and judging high school drama contests almost 25 years ago now, he says, "If I saw one more Agnes of God…" If you've experienced high school drama contests since that play was written, you know exactly what he means (and I'd toss in 'night, Mother as well).

Reilly talks and talks and talks and you're never bored. You're usually laughing, but sometimes, as when he describes being present at 13 at an infamous Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus fire that claimed many lives, including that of one of his childhood friends, you're mesmerized. The Life of Reilly truly captivates. The biggest barrier to enjoying it is finding a way to see it. It's on streaming at Netflix but not DVD, so watch it there before you cancel and go back to DVD only. Neither GreenCine nor Blockbuster carries it on DVD or On Demand. Redbox doesn't carry it. Hulu Plus doesn't stream it. Amazon Instant Video DOES have it for $2.99, though you could buy it for $9.99. Best Buy CinemaNow doesn't have it for streaming. Comcast XfinityTV ON Demand doesn't have it either.

It's a miracle that Netflix's streaming has it right now because eventually, it won't as smaller, wonderful titles such as The Life of Reilly that are a whole FOUR years old and are perceived as having too small a niche audience disappear entirely from home rental availability. It's a shame because it means the number of people who remember Charles Nelson Reilly will decline more rapidly than it is declining already.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Awards, Burt Reynolds, Carson, Disney, Documentary, Durning, Frank Loesser, Geraldine Page, Grodin, Holbrook, Ingmar Bergman, Lemmon, Musicals, O'Neill, Oscars, Robards, Shakespeare, Television, Twain

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, July 23, 2011

Tom Aldredge (1928-2011)

When I was just beginning my years of obsessive New York theatergoing, the second Broadway show I took in was the last new Stephen Sondheim musical to premiere on Broadway, Passion, in 1994. I was still an amateur as far as theatergoing went so I got to the Longacre Theatre for the 2 p.m. Saturday matinee very early. Seated on the sidewalk by the stage door in a T-shirt and jeans wearing a baseball cap creased to the point it resembled a duck bill, was the actor Tom Aldredge. Throughout my theatergoing years, which basically ran from 1994 until 1999 with a handful later before ending permanently in 2002, I saw Aldredge, not by design, in more shows than any other actor. Readers who haven't attended New York theater regularly since Aldredge made his Broadway debut in 1959 probably know him best from his television work, be it as Carmela's father Hugh DeAngelis on The Sopranos, Patty Hewes' Uncle Pete on Damages or Nucky Thompson's bitter father Ethan on Boardwalk Empire. Aldredge died Friday after a long battle with cancer. He was 83.

As I said, I saw him more on stage than any other actor (not that it took much) seeing him in four shows between 1994-97. In addition to Passion, I saw Aldredge as Rev. Jeremiah Brown in the revival of Inherit the Wind with George C. Scott and Charles Durning. I got to see him perform Solyony (the Captain) in Chekhov's The Three Sisters, replacing Jerry Stiller in the role. Finally, I saw him play Stephen Hopkins in the revival of the musical 1776 with Brent Spiner and the late Pat Hingle.

Aldredge was born Feb. 28, 1928, in Dayton, Ohio. He attended the Goodman School of Drama at DePaul University. He married his wife Theoni V. Aldredge in 1953, a union that lasted until her death in January of this year. Theoni was an acclaimed costume designer for theater and movies who won three Tonys for her work (Annie, Barnum and La Cage Aux Folles ) out of a total 14 nominations and won an Oscar for her costumes for 1974's The Great Gatsby.

The first time I recall seeing Tom Aldredge actually combined theater and television. It was when PBS aired a filmed version of Sondheim's great Broadway musical Into the Woods in 1991. Aldredge played the dual role of the narrator and the Mysterious Man. Given Aldredge's prolific output in television and movies, I'm certain I ran across him before that, but it certainly was the first time he left an impression on me. The second time came courtesy of HBO, but not on the more celebrated series he's probably most recognizable from, but from what may be the first really good made-for-HBO movie: 1993's Barbarians at the Gate. Aldredge's part wasn't huge, but I remembered him in that great Larry Gelbart-scripted account of the takeover battle for RJR Nabisco starring James Garner and Jonathan Pryce. After that, most of my Aldredge performances were seen on stage.

Tom Aldredge's New York stage career began in 1957 and he landed his first Broadway show in 1959 in the musical comedy The Nervous Set which also featured Larry Hagman in its cast. It took seven years to land another Broadway role but when he did, what a cast he got to work alongside. The original comedy UTBU was directed by Nancy Walker and had an ensemble featuring Cathryn Damon (Mary Campbell on Soap), Margaret Hamilton, Tony Randall and Thelma Ritter. Alas, it only lasted 15 previews and seven performances. Fortunately, Aldredge was back on Broadway the next month in Slapstick Tragedy, which was an evening of two new Tennessee Williams' one-act plays. Aldredge appeared in the first, The Mutilated. The second one-act was The Gnadiges Fraulein.

In the seven year interim between his Broadway debut in 1959 and his return in 1966, Aldredge was by no means idle. He made his television debut in 1961 as part of The Premise Players on a Paul Anka special called The Seasons of Youth where Anka discusses a long-lost crush and the actors perform skits about young love. In 1963, Aldredge made his film debut in The Mouse on the Moon, the sequel to The Mouse That Roared. In 1964, many of the same members of The Premise Players, which now included Buck Henry who co-wrote the script, made The Troublemaker about a New Jersey chicken farmer who moves to Greenwich Village to open a coffee shop. Aldredge had a role in 1965's Who Killed Teddy Bear?, whose plot, as described by IMDb, is "A busboy at a disco has sexual problems related to events in his childhood. He becomes obsessed with a disc jockey at the club, leading to obscene phone calls, voyeurism, trips to the porn shop and adult movie palace, and more!" The unusual cast includes Sal Mineo, Juliet Prowse, Jan Murray, Elaine Stritch and Daniel J. Travanti. Aired on TV in 1966 after Aldredge had returned to New York was a movie adaptation of Tennessee Williams' Ten Blocks on the Camino Real which Williams wrote and which starred Martin Sheen.

Back in New York, before he returned to Broadway, Aldredge took part in two of Joseph Papp's Shakespeare in the Park productions in the summer of 1965. First, he played Boyet in Love's Labors Lost. Then he played Nestor in Troilus and Cressida, whose cast included James Earl Jones, Michael Moriarty and John Vernon. Throughout his career he would return to the Delacorte and Shakespeare. He played Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet in 1968, Sir Andrew Aguecheek in Twelfth Night in 1969, the title role in Cymbeline in 1971, the 2nd Gravedigger in Hamlet in 1972, Lear's Fool in King Lear in 1973 and John of Gaunt in Richard II in 1987. Ironically, the only time Aldredge received an Emmy nomination, it was a Daytime Emmy nomination (which he won) for playing Shakespeare in a 1973 episode of The CBS Festival of Lively Arts for Young People titled "Henry Winkler Meets William Shakespeare." Aldredge appeared in many off-Broadway productions but two to take note of are his role of Emory in the original production of the landmark play The Boys in the Band and the Joseph Papp production of David Rabe's Sticks and Bones, which transferred to Broadway and earned Aldredge the first of his five Tony nominations.

His 1972 nomination for lead actor in a play for Sticks and Bones, which won best play, was Aldredge's only in the lead category. His other nominations came for the revival of the musical Where's Charley? in 1975, the revival of The Little Foxes opposite Elizabeth Taylor in 1981, in the original musical Passion in 1994 and in the revival of the play Twentieth Century in 2004.

Throughout his Broadway career, he performed the works of O'Neill (The Iceman Cometh, Strange Interlude), George Bernard Shaw (Saint Joan) and Arthur Miller (The Crucible) and created the role of Norman Thayer Jr. in the original production of On Golden Pond. His final Broadway show was a revival of Twelve Angry Men that closed in May 2005.

His many film credits include Coppola's The Rain People, a 1973 film version of his stage success Sticks and Bones directed by Robert Downey Sr., Lawn Dogs, Rounders, Intolerable Cruelty, Cold Mountain, the remake of All the King's Men, What About Bob? and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford.

He appeared in lots of episodic television and some notable TV movies including the miniseries The Adams Chronicles, Great Performances' Heartbreak House, playing Justice Hugo Black in Separate But Equal and O Pioneers!

Aldredge was a talented and prolific actor who needs to be remembered for more than playing Carmela Soprano's dad, but for Sopranos trivia buffs I'll toss in that Hugh and Carmela's mother Mary (Suzanne Shepherd) didn't appear until Livia was banned from the Soprano home. Who can forget him ripping into Livia at her wake? I wish YouTube had the actual clip of "Ever After" that Aldredge starts the cast singing at the end of Act I of Into the Woods, for I feel it's a fitting close. Click here and listen anyway,

RIP Mr. Aldredge.

Tweet

Labels: Arthur Miller, Boardwalk Empire, Buck Henry, Coppola, Durning, Gelbart, George C. Scott, HBO, J.E. Jones, Liz, M. Sheen, O'Neill, Obituary, Shakespeare, Sondheim, Tennessee Williams, The Sopranos, Theater, Thelma Ritter, Tony Randall

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, April 09, 2011

Sidney Lumet (1924-2011)

I want you to get up right now. I want you to stand up, out of your chairs. I want you to get up, go to your window, open it and shout, "I'm as sad as hell. Sidney Lumet has died." One of the all-time great film directors, whose debut in 1957, 12 Angry Men, earned him his first Oscar nomination, and who 50 years later still was capable of producing as great a film as Before the Devil Knows You're Dead died today in New York at 86.

Lumet actually began his career as a child actor, making his first appearance on the Broadway stage in 1935 in the original production of Dead End. He'd act on Broadway multiple times until 1948 when directing for

television caught his eye. He only directed on Broadway three times. His direction for television began in 1951 and included both episodic television and the many live playhouse shows until the chance to direct 12 Angry Men as a feature came along in 1957. Its origins as a play clearly showed, but there was no point trying to open this tale up since the claustrophobia of that jury room heightened the drama and Lumet used to his advantage, as in the moment when they discuss the unusual knife the defendant had and that the victim was killed with and Henry Fonda suddenly whips out one of his own, tossing it so the blade sticks in the middle of the table. The film contained a great cast including, in addition to Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, E.G. Marshall and Jack Warden. In fact, of the 12 members of that jury, only Jack Klugman remains with us today.

television caught his eye. He only directed on Broadway three times. His direction for television began in 1951 and included both episodic television and the many live playhouse shows until the chance to direct 12 Angry Men as a feature came along in 1957. Its origins as a play clearly showed, but there was no point trying to open this tale up since the claustrophobia of that jury room heightened the drama and Lumet used to his advantage, as in the moment when they discuss the unusual knife the defendant had and that the victim was killed with and Henry Fonda suddenly whips out one of his own, tossing it so the blade sticks in the middle of the table. The film contained a great cast including, in addition to Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, E.G. Marshall and Jack Warden. In fact, of the 12 members of that jury, only Jack Klugman remains with us today.Lumet continued his television work, not directing another feature until 1959's That Kind of Woman starring Sophia Loren. The following year, he got more notice when Tennessee Williams adapted his own play Orpheus Descending into The Fugitive Kind which Lumet filmed with Marlon Brando and Anna Magnani. In 1962, Lumet made a film of another stage classic, Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night, starring Katharine Hepburn as the opium-addicted Mary Tyrone.

In 1964, he filmed two of his most underrated movies: The Pawnbroker, featuring a great performance by Rod Steiger as the Jewish title character, a Holocaust survivor, who has given up on mankind; and Fail-Safe, a tense nuclear thriller starring Henry Fonda that got overshadowed by the satire of Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove which came out first the same year.

He kept quite busy for the rest of the 1960s and early '70s, directing The Hill, The Group, Bye Bye Braverman, The Sea Gull, The Appointment, Last of the Mobile Hot Shots, The Anderson Tapes, The Offence and Child's Play. In 1971, Lumet and Joseph L. Mankiewicz co-directed the documentary King: A Filmed Record...Montgomery to Memphis about Martin Luther King Jr.

Beginning in 1973, Lumet started what was the most creatively fertile and rewarding period of his filmmaking career, one that earned him four consecutive nominations from the Directors Guild. Starting with Al Pacino in Serpico, it was one of many times in Lumet's career he'd turn his lens on the issue of corruption among police. In 1974, he went in another direction, casting Albert Finney as Agatha Christie's famed Belgian sleuth Hercule Poirot and assembled an amazing cast for Murder on the Orient Express.

Then came the first of an amazing one-two punch with 1975's Dog Day Afternoon, one of Lumet's greatest achievements and a film I never tire of watching. With Al Pacino and John Cazale attempting to rob a bank and having it turn into a hostage situation and a media sideshow, it's a wonder. It brought Lumet his first Oscar nomination for directing since that initial one for 12 Angry Men. It's not only proof of what a great director Lumet could be but when they released the special two-disc DVD edition of the film, Lumet also showed that he's one of the few people who actually recorded DVD commentaries that were worth listening to, sharing many interesting details about the production of this great work which deftly blends the humorous, the tragic and the absurd.

He followed Dog Day up in 1976 with the incomparable Network. While much of the credit for this satirical and prescient masterpiece deservedly goes to Paddy Chayefsky's Oscar-winning script, Lumet's direction

shouldn't get short shrift. The way he filmed the chaos of the network control rooms and its overlapping dialogue and always found the right pacing for whatever craziness was going on. Also, as in Dog Day, Lumet didn't have a musical score. Except for the opening song in the 1975 film and the network news theme in Network, he eschewed any musical underscore. Neither film needed one. He also assembled some great visual compositions, such as the long view down the canyons of New York with windows open as far as the eyes could see with heads sticking out screaming "I'm mad as hell" to Ned Beatty and the lighting as he's at the end of that long conference table about to give Peter Finch his corporate cosmology speech. Brilliant. Lumet received his third directing nomination.

shouldn't get short shrift. The way he filmed the chaos of the network control rooms and its overlapping dialogue and always found the right pacing for whatever craziness was going on. Also, as in Dog Day, Lumet didn't have a musical score. Except for the opening song in the 1975 film and the network news theme in Network, he eschewed any musical underscore. Neither film needed one. He also assembled some great visual compositions, such as the long view down the canyons of New York with windows open as far as the eyes could see with heads sticking out screaming "I'm mad as hell" to Ned Beatty and the lighting as he's at the end of that long conference table about to give Peter Finch his corporate cosmology speech. Brilliant. Lumet received his third directing nomination.Things got a little bumpy filmwise after that. Next came the adaptation of the play Equus followed by what many count as his biggest mistake: casting a too old Diana Ross as Dorothy in the big screen version of the Broadway musical The Wiz, which also featured Michael Jackson as the Scarecrow. Next came a rather lame Alan King-Ali McGraw romantic comedy (Yes, you read that correctly) called Just Tell Me What You Want.

Lumet began to get his bearings again by going back to police corruption with 1981's Prince of the City, which earned him his first Oscar nomination in a writing category. The next year brought him his final nomination as a director for The Verdict, starring Paul Newman as an alcoholic lawyer seeking redemption. That same year, he made the fun adaptation of the play Deathtrap starring Michael Caine and Christopher Reeve.

The remainder of his career mixed some OK efforts with some really bad ones. He made Running on Empty, which earned River Phoenix an Oscar nominaton but did his best when going back to corruption in movies such as 1990's Q&A and 1996's Night Falls on Manhattan. In 2005, the Academy finally saw fit to award him an honorary Oscar, back when they still televised those events. At least he ended on a high note, with the really good 2007 film Before the Devil Knows You're Dead starring Philip Seymour Hoffman, Ethan Hawke and Albert Finney.

RIP Mr. Lumet.

Tweet

Labels: Brando, Caine, Chayefsky, E.G. Marshall, H. Fonda, Hawke, Jack Warden, K. Hepburn, Kubrick, Lee J. Cobb, Magnani, Mankiewicz, N. Beatty, Newman, O'Neill, Obituary, P.S. Hoffman, Pacino, River Phoenix, Tennessee Williams

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, March 26, 2011

Centennial Tributes: Tennessee Williams

By Sheila O'Malley

An interviewer once asked Tennessee Williams, “What is the definition of happiness?” Williams thought a bit and then replied, “Insensitivity, I guess.”

The great female characters of the Williams canon — Laura and Amanda Wingfield (Glass Menagerie), Blanche DuBois (Streetcar Named Desire), Alma Winemiller (Summer and Smoke), Maggie the Cat (Cat on a Hot Tin Roof), Catherine Holly (Suddenly, Last Summer), to name just a few — are the “sensitives” of the world, predisposed to unhappy lives because of their sensitivity, but in Williams’ view, the sensitives are the strongest of all of us. This psychological standpoint is still his most radical contribution. The more obviously hearty people will not understand, and would wish Blanche to “buck up” a little bit, or Alma to stop mooning around about John Buchanan…but to wish that is to wish away Williams’ drama, of course, and to wish away the best part of ourselves, which is our vulnerability. Williams spoke to that vulnerability and gave it a voice in a way no other 20th century playwright did. His only rival was Eugene O’Neill. In a 1948 essay in The New York Times, Williams wrote about the questions that people would ask him about his plays and his characters:

On this particular occasion the question that floored me was, “Why do you always write about frustrated women?”

To say that floored me is to put it mildly, because I would say that frustrated is almost exactly what the women I write about are not. What was frustrated about Amanda Wingfield? Circumstances, yes! But spirit? See Helen Hayes in London’s Glass Menagerie if you still think Amanda was a frustrated spirit! No, there is nothing interesting about frustration, per se. I could not write a line about it for the simple reason that I can’t write a line about anything that bores me. Was Blanche of A Streetcar Named Desire frustrated? About as frustrated as a beast of the jungle! And Alma Winemiller? What is frustrated about loving with such white hot intensity that it alters the whole direction of your life, and removes you from the parlor of the Episcopal rectory to a secret room above Moon Lake Casino?

Tennessee Williams was born Thomas Lanier Williams III on March 26, 1911, in Columbus, Miss., to parents Cornelius and Edwina Williams. He had a brother, Dakin, and a sister, Rose. He was very close to his maternal grandfather, Walter Dakin, an Episcopal priest who, later in life, traveled extensively with his grandson, and set up house with him in Key West on occasion. Cornelius Williams was often absent due to his job as a traveling salesman (Tennessee would utilize this experience in his first hit play, Glass Menagerie, where Mr. Wingfield, never seen in the play, was described as “a telephone man — who fell in love with long-distance!”), and so the three children were raised primarily by Edwina. His father thought “Tom” was effeminate and gave him a hard time about it.

The family moved to St. Louis, where Tennessee attended high school and began writing in earnest. He tried his hand at poetry, short stories, essays. His interest in drama would come a bit later.

In 1937, he was accepted into the University of Iowa (after dabbling in journalism at the University of Missouri). He transferred eventually to Washington University in St. Louis where we start to see the playwright Tennessee Williams being born. He worked on the campus literary journal, whose members are pictured here (Williams is second from the left). He became involved with a local theater group called the Mummers of St.

Louis, who produced one of his earliest known plays. He looked back very fondly on that company and even as an old man said that the productions of the Mummers represented to him the best that theater had to offer: the sheer joy in the process, the collaboration, and the sense of a supportive cohesive community. This was the 1930s and Clifford Odets was the biggest star in American playwriting, his socially conscious and politically left-leaning plays taking Broadway by storm in the productions of the short-lived Group Theatre. Williams loved Odets, and his earliest plays (some of which will be published for the first time this April in a collection called The Magic Tower show that influence, an influence he would quickly shed. (The new book can be found on Amazon here.) While his successful plays are some of the most socially conscious plays ever written, in terms of their constant reminders to us that we need to be KIND to one another, he was not explicitly political, and the left-wing bandwagon was not for him. Odets’ mantle fit awkwardly on Williams’ shoulders. It was around this time in Williams’ life that his beloved sister Rose began her long descent into madness.

Louis, who produced one of his earliest known plays. He looked back very fondly on that company and even as an old man said that the productions of the Mummers represented to him the best that theater had to offer: the sheer joy in the process, the collaboration, and the sense of a supportive cohesive community. This was the 1930s and Clifford Odets was the biggest star in American playwriting, his socially conscious and politically left-leaning plays taking Broadway by storm in the productions of the short-lived Group Theatre. Williams loved Odets, and his earliest plays (some of which will be published for the first time this April in a collection called The Magic Tower show that influence, an influence he would quickly shed. (The new book can be found on Amazon here.) While his successful plays are some of the most socially conscious plays ever written, in terms of their constant reminders to us that we need to be KIND to one another, he was not explicitly political, and the left-wing bandwagon was not for him. Odets’ mantle fit awkwardly on Williams’ shoulders. It was around this time in Williams’ life that his beloved sister Rose began her long descent into madness.Tom’s sister Rose was always thought to be neurotic, too “nervous,” and once she hit her teenage years and became boy-crazy (like most teenage girls), the cracks in her psyche began to open. A failed “debut” seems to have been particularly traumatic, and Rose had a series of breakdowns (one psychiatrist told her that her problem was that she needed to get married), was hospitalized, given insulin treatments, shock treatments, and finally, in 1943, a prefrontal lobotomy. By that point, Williams had left town and was living in New York, struggling to get by on writing grants and odd jobs. On March 24, 1943, he wrote in his journal, after receiving a letter from his mother about Rose’s “operation”:

1000 miles away.

Rose.

Her head cut open. A knife thrust in her brain.

Me. Here. Smoking.

This was the defining event in his life, even more so than being a gay man in the 1930s and '40s, even more so than being a writer from the South. Rose’s inability to either heal the cracks within her, or live with those cracks, haunted Tennessee Williams to his dying day, and play after play deals with madness, fear of madness, and also, in one case specifically (Suddenly, Last Summer) lobotomies. There is a danger in assigning too much autobiographical meaning to Williams’ works, as though there should be a literal A to B correlation. To read the plays as glorified journal entries is a huge disservice to the universality of his work (the recent failed production of Glass Menagerie at The Long Wharf, reviewed here by John Lahr, is evidence of that.) Williams turned what had happened to his sister Rose into art. As Tom Wingfield says, in his final monologue in The Glass Menagerie:

I would have stopped, but I was pursued by something. It always came upon me unawares, taking me altogether by surprise. Perhaps it was a familiar bit of music. Perhaps it was only a piece of transparent glass. Perhaps I am walking along a street at night, in some strange city, before I have found companions. I pass the lighted window of a shop where perfume is sold. The window is filled with pieces of colored glass, tiny transparent bottles in delicate colors, like bits of a shattered rainbow. Then all at once my sister touches my shoulder. I turn around and look into her eyes. Oh, Laura, Laura, I tried to leave you behind me, but I am more faithful than I intended to be! I reach for a cigarette, I cross the street, I run into the movies or a bar, I buy a drink, I speak to the nearest stranger — anything that can blow your candles out! For nowadays the world is lit by lightning! Blow out your candles, Laura — and so goodbye...

In 1939, Williams moved to New Orleans, and it was there that he began to emerge as an individual voice. It also was when he formally changed his name to “Tennessee,” the state where his father was born. In his journals and letters, it is apparent that during this fertile time in his life he already was percolating the ideas that would become Glass Menagerie and Streetcar Named Desire: There are early one-acts that are rehearsals for those later plays. His first major full-length play was Battle of Angels (1940), about a virile young drifter named Val who strolls into a dressmaker’s shop in a small town after his car breaks down, looking for help. The dressmaker’s shop is run by a woman named Myra who is trapped in a loveless marriage. Battle of Angels would eventually be rewritten by Williams in 1957 as Orpheus Descending. Battle of Angels was produced in Boston and was a resounding flop. It would be his first (but not his last) experience of controversy and calls for censorship, due to the explicit sexual subtexts in his plays. Although Battle of Angels was not a success, it brought him into contact with powerful people, producers and agents (Margo Jones, Audrey Wood and others), who would become lifelong supporters of Williams and his work. Around this time, he wrote in his journal:

My next play will be simple, direct and terrible — a picture of my own heart — there will be no artifice in it — I will speak truth as I see it — distort as I see distortion — be wild as I am wild — tender as I am tender — mad as I am mad — passionate as I am passionate — It will be myself without concealment or evasion and with a fearless unashamed frontal assault upon life that will leave no room for trepidation. I believe that the way to write a good play is to convince yourself that it is easy to do — then go ahead and do it with ease. Don’t maul, don’t suffer, don’t groan — till the first draft is finished. Then Calvary — but not till then. Doubt — and be lost — until the first draft is finished.

It was out of this attitude that The Glass Menagerie was born. Williams had written a short story called “Portrait of a Girl in Glass” (1943) and began to turn it into a play (he often worked this way, backing into the play format). Margo Jones, one of the pioneers of the American regional theater movement, had hitched herself to Tennessee Williams early on, and was tireless in promoting him. She and Eddie Dowling produced The Glass Menagerie (Dowling also directed and played Tom Wingfield) and a production was planned to open in Chicago in 1944. Casting was a challenge and getting the once-great and now-washed-up Laurette Taylor (who had been a star of vaudeville) to play Amanda Wingfield was a big coup. Taylor had been famous as a young actress, but now was known mainly for her drinking problem. Rehearsals for Glass Menagerie were difficult sometimes. Lyle Leverich wrote in Tom, his magnificent biography of Tennessee Williams:

Tennessee remembered that Laurette appeared to know only a fraction of her lines, and these she was delivering in “a Southern accent which she had acquired from some long-ago black domestic.” He was even more disconcerted when she said she was modeling her accent after his! Tom wrote to Donald Windham, complaining that Laurette was ad-libbing many of her speeches and that the play was beginning to sound more like the Aunt Jemima Pancake hour.

To him, Laurette’s “bright-eyed attentiveness to the other performances seemed a symptom of lunacy, and so did the rapturous manner of dear Julie.” He was witnessing a characteristic of many of the theater’s great actors who were quick studies but painfully deliberate in their approach to a role. As Laurette’s daughter explained, “She seemed blandly unconscious of the discomfort of the others…Amanda [the role] fascinated her. She could see whole facets of the woman’s life before the action of the play and after it was over.” This is what her husband had taught her was the test of a good part. “The outer aspect of this inner search concerned her not at all.”

Paul Bowles, a friend of Williams who composed the music that played throughout the play, came to Chicago for the dress rehearsal, and described the atmosphere:

“I flew out to Chicago [and] arrived in a terrible blizzard, I remember. It was horrible. A traumatic experience. And the auditorium was cold. Laurette Taylor was on the bottle, unfortunately. Back on it, really. She had got off it with the first part of the rehearsals but suddenly the dress rehearsal coming up was too much. [Laurette was discovered] unconscious, down behind the furnace in the basement. And there was gloom, I can tell you, all over the theater because no one thought she would be able to go on the next night.”

But she did go on, and by all accounts it was one of the greatest performances ever given by an American actress in the history of our theatrical tradition. The praise runs far and wide, and while Williams’ play, with its delicate heartbreak, and keening sense of loss and memory, was definitely something “new” (nobody was writing like he was at the time), it was Laurette Taylor’s magnificent performance that helped launch Williams into the stratosphere. His life would never be the same again. Leverich wrote:

Laurette Taylor never lost an opportunity to divert the praise that was being heaped upon her to that “nice little guy,” Tennessee Williams. She was always quick to remind her admirers that it was he, not she, who had written the lines that gave The Glass Menagerie its special power and beauty. And she told Tennessee, “It’s a beautiful — a wonderful — a great play!”

For his part, Tennessee Williams always said that, as much as he regarded Laurette Taylor a personal friend, he never ceased to be in awe of her. “She had such a creative mind,” he once remarked. “Something magical happened with Laurette. I used to stand backstage. There was a little peephole in the scenery, and I could be just about three feet from her, and when the lights hit her face, suddenly twenty years would drop off. An incandescent thing would happen in her face; it was really supernatural.”

The Glass Menagerie moved to Broadway in 1945, and was a smash hit, Laurette Taylor becoming the toast of the town once again (she would die in 1946), and Williams becoming a star. In 1947, Williams wrote a letter to his friend (poet and publisher Jay Laughlin):

I have done a lot of work, finished two long plays. One of them, laid in New Orleans, A STREETCAR CALLED DESIRE, turned out quite well. It is a strong play, closer to Battle of Angels than any of my other work, but is not what critics call “pleasant.” In fact it is pretty unpleasant.

This “unpleasant” play would bring him into contact for the first time with one of his most important collaborators, Elia Kazan. It may seem like an odd combination: the lyrical openly gay Southern writer paired up with the virile manipulative ambitious Greek immigrant, but it turned out to be a perfect fit. Kazan’s genius with theatrical language, with turning “psychology into behavior” (his definition of good acting), his strong basis in production values and practical matters (there was a reason why his nickname was “Gadg” — short for “Gadget”, a fix-it man) helped ground Williams’ work in a living-and-breathing reality. If a “lyrical” director had taken Williams’ plays on, it could have been disastrous, but Kazan’s gritty sense of truth often saved Williams from himself. Williams recognized this, recognized what Kazan provided. It was an intense, combative (at times) and very fruitful working relationship, and Kazan would go on to direct some of Williams’ biggest successes. A Streetcar Named Desire, starring Jessica Tandy as Blanche DuBois and a young relatively unknown Marlon Brando as Stanley Kowalski, opened on Broadway in 1947. Glass Menagerie had launched him, A Streetcar Named Desire solidified his position. It also made Marlon Brando a star. Brando described, years later, his experience of that time: