Saturday, May 19, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part II

By Edward Copeland

We pick up our tribute to Richard Brooks in 1956. If you missed Part I, click here. Of Brooks' two 1956 releases, I've only seen one of them. The Last Hunt stars Stewart Granger as a rancher who loses all his cattle to a stampeding herd of buffalo. Robert Taylor plays a buffalo hunter who asks him to join in an expedition to slaughter the animals, but the rancher, an ex-buffalo hunter himself, had quit because he'd grown weary of the killing. Brooks may be the auteur of antiviolence. Filmed in Technicolor Cinemascope, I imagine it looked great on the big screen. Bosley Crowther wrote in his New York Times review, "Even so, the killing of the great bulls—the cold-blooded shooting down of them as they stand in all their majesty and grandeur around a water hole—is startling and slightly nauseating. When the bullets crash into their heads and they plunge to the ground in grotesque heaps it is not very pleasant to observe. Of course, that is as it was intended, for The Last Hunt is aimed to display the low and demoralizing influence of a lust for slaughter upon the nature of man." The second 1956 film I did see and given the talents involved and the paths it would take, it's a fairly odd tale. The Catered Affair was the third and last film in Richard Brooks' entire directing career that he also didn't write or co-write.

It began life as a teleplay by the great Paddy Chayefsky in 1955 called A Catered Affair starring Thelma Ritter, J. Pat O'Malley and Pat Henning before its adaptation for the big screen the following year, the same journey Chayefsky's Marty took that ended up in Oscar glory. This time, Chayefsky didn't adapt his work for the movies — Gore Vidal did. Articles of speech changed in its title as well as the teleplay A Catered Affair became The Catered Affair for Brooks' film. (Chayefsky apparently wasn't a particular fan of this work of his — it never was published or appeared in a collection of his scripts.) We're at the point where the project just got screwy. The simple story concerns an overbearing Irish mom in the Bronx determined to give her daughter a ritzy wedding because of the bragging she hears her future in-laws go on about describing the nuptials thrown for their girls. Despite the fact that the Hurley family lacks the funds for it, Mrs. Hurley stays determined while her husband Tom sighs — he's been saving to buy his own cab. On TV, the casting of Ritter and O'Malley for certain sounded appropriate. For the film, which added characters since it had to expand the length, the cast appeared to have been picked out of a hat because they certainly didn't seem related, most didn't register as Irish and as for being from the Bronx — fuhgeddaboudit. Meet Mr. and Mrs. Tom Hurley, better known to you as Ernest Borgnine and

Bette Davis. Unlikely match though they be, somehow their genes combined and out popped the most Bronx-like of Irish girls — Debbie Reynolds. The new character of Uncle Jack does add a bit of real Irish flavor by tossing in Barry Fitzgerald for no apparent reason. Unbelievably, it made the list of the top 10 films of the year from the National Board of Review who also named Reynolds best supporting actress (nothing against Reynolds in general — just miscast here). You would think that this Affair would fade into oblivion, but you'd be wrong. In 2008, it changed articles again and re-emerged on the Broadway stage as the musical A Catered Affair. Faith

Bette Davis. Unlikely match though they be, somehow their genes combined and out popped the most Bronx-like of Irish girls — Debbie Reynolds. The new character of Uncle Jack does add a bit of real Irish flavor by tossing in Barry Fitzgerald for no apparent reason. Unbelievably, it made the list of the top 10 films of the year from the National Board of Review who also named Reynolds best supporting actress (nothing against Reynolds in general — just miscast here). You would think that this Affair would fade into oblivion, but you'd be wrong. In 2008, it changed articles again and re-emerged on the Broadway stage as the musical A Catered Affair. Faith Prince and Tom Wopat(Yes — that Tom Wopat of Luke Duke fame) earned Tony nominations as the parents, Harvey Fierstein wrote the book and played the uncle (named Winston) and John Bucchino wrote the score. Why did Brooks make this one? Easy. He was under contract. MGM told him to make it, so he had no choice. From Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks, some of the cast talked on record about how Brooks could be a bit of a prick as a director. "I didn't know it at the time, but Brooks ate and digested actors for breakfast," Borgnine said later. "If things weren't working, he let you know it, and not gently." When a particular scene was not working to his satisfaction, (Brooks) ordered Borgnine and Davis to figure out the problem. Borgnine suggested a different pacing and Davis agreed the scene was better for it — as did (Brooks), though he offered Borgnine not praise but a putdown. 'Goddamn thinking actor.'" Reynolds also tells the author Douglass K. Daniel that from the first day she met Brooks he told her that he didn't want her in the part, but it wasn't his decision. "'He said he was stuck with me and he'd do the best he could with me,' Reynolds recalled. 'He hoped I could come through all right with him, because everybody else was so great, but he wasn't certain I could keep up with the others. He actually said he was stuck with me. And he said so in front of everybody, too. He was so cruel.'" Davis and Borgnine coached Reynolds on the side and Bette, not known to be a shrinking violet, told Reynolds once, according to the book, "'Don't pay any attention to him, the son of a bitch,' Davis told her. 'The only important thing is to work with the greats.'" Davis did get help from Brooks in her fight against the studio that a Bronx housewife shouldn't be wearing movie star costumes they wanted, so he supported her decision to buy clothes at a store like Mrs. Hurley would shop at in real life. Years later, Davis referred to Brooks as one of the greats. This wasn't the first time Brooks had treated a young actress oddly on a set, Anne Francis told Douglass Daniel for his book that he practically ignored her during the filming of Blackboard Jungle and she received no direction at all. Daniel suggests and, given the way Brooks ordered Borgnine and Davis to come up with an idea to fix a scene, that writing had been his greatest gift, he grew into a solid visual storyteller, but Brooks proved limited when it came to directing actors. Daniel wrote, "…(the accounts of Francis and Reynolds) suggested he had a limited ability to communicate what he wanted. He either paid them little attention…or tried to bully a performance from them." Despite that problem, 10 actors in Brooks-directed films earned Oscar nominations and three took home the statuette.

Prince and Tom Wopat(Yes — that Tom Wopat of Luke Duke fame) earned Tony nominations as the parents, Harvey Fierstein wrote the book and played the uncle (named Winston) and John Bucchino wrote the score. Why did Brooks make this one? Easy. He was under contract. MGM told him to make it, so he had no choice. From Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks, some of the cast talked on record about how Brooks could be a bit of a prick as a director. "I didn't know it at the time, but Brooks ate and digested actors for breakfast," Borgnine said later. "If things weren't working, he let you know it, and not gently." When a particular scene was not working to his satisfaction, (Brooks) ordered Borgnine and Davis to figure out the problem. Borgnine suggested a different pacing and Davis agreed the scene was better for it — as did (Brooks), though he offered Borgnine not praise but a putdown. 'Goddamn thinking actor.'" Reynolds also tells the author Douglass K. Daniel that from the first day she met Brooks he told her that he didn't want her in the part, but it wasn't his decision. "'He said he was stuck with me and he'd do the best he could with me,' Reynolds recalled. 'He hoped I could come through all right with him, because everybody else was so great, but he wasn't certain I could keep up with the others. He actually said he was stuck with me. And he said so in front of everybody, too. He was so cruel.'" Davis and Borgnine coached Reynolds on the side and Bette, not known to be a shrinking violet, told Reynolds once, according to the book, "'Don't pay any attention to him, the son of a bitch,' Davis told her. 'The only important thing is to work with the greats.'" Davis did get help from Brooks in her fight against the studio that a Bronx housewife shouldn't be wearing movie star costumes they wanted, so he supported her decision to buy clothes at a store like Mrs. Hurley would shop at in real life. Years later, Davis referred to Brooks as one of the greats. This wasn't the first time Brooks had treated a young actress oddly on a set, Anne Francis told Douglass Daniel for his book that he practically ignored her during the filming of Blackboard Jungle and she received no direction at all. Daniel suggests and, given the way Brooks ordered Borgnine and Davis to come up with an idea to fix a scene, that writing had been his greatest gift, he grew into a solid visual storyteller, but Brooks proved limited when it came to directing actors. Daniel wrote, "…(the accounts of Francis and Reynolds) suggested he had a limited ability to communicate what he wanted. He either paid them little attention…or tried to bully a performance from them." Despite that problem, 10 actors in Brooks-directed films earned Oscar nominations and three took home the statuette.

The following year, Brooks made another film that revolved around the hunt of an animal, though that just leads to much bigger issues in Something of Value, sometimes known as Africa Ablaze. Starring Rock Hudson and filmed in Kenya, the film, which I haven't seen, concerns tensions that erupt between formerly friendly colonial white settlers and the Kenyan tribesmen. It also began a run of films that Brooks adapted from serious literary sources. Something of Value had been written by Robert C. Ruark, a former journalist like Brooks, who fictionalized his experiences being present in Kenya during the Mau Mau rebellion. In 1958, the two authors he adapted carried names more prestigious and recognizable. The first movie released derived from a particularly literary source and Brooks didn't do all that heavy lifting alone. Julius and Philip Epstein did the original adaptation, working from the English translation of the novel by Constance Garnett before Brooks began his work writing a worthwhile screenplay that didn't run more than two-and-a-half hours out of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov. It wasn't easy. Brooks told Daniel that he "wrestled with the book for four months." What surprised me to learn, also according to what Brooks told Daniels, MGM assigned Karamazov to him. Brooks also said that he never initiated any of his films while under contract at MGM. I love Dostoyevsky. Hell, even a master such as Kurosawa couldn't pull off a screen adaptation of The Idiot. The only aspect of this film that holds your attention — actually it would be more accurate to say grabs you by your throat and keeps you awake for his moments — ends up being any scene with Lee J. Cobb playing the Father Karamazov. I don't know if Cobb realized that somebody needed to step up or what, but the brothers, with only Yul Brynner showing much charisma, also include William Shatner. It's almost embarrassing except for Cobb who got a deserved supporting actor Oscar nomination, the first of the 10 from Brooks-directed films.

The actor who Cobb lost that Oscar to that year had a major part in Brooks' other 1958 feature — the film adaptation of Tennessee Williams' Pulitzer Prize-winning play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. However, Burl Ives didn't win the prize for his great turn as Big Daddy, but for his role as a ruthless cattle baron fighting with another rancher over land and water in The Big Country. As with nearly all of Williams' works, movie versions castrated his plays' subtext (and sometimes just plain text) and this proved true with Cat as well, though the cast and its overriding theme of greed kept it involving enough. The film scored at the box office for MGM, taking in a (big for 1958) haul of $8.8 million — Leo the Lion's biggest hit of the year and third-biggest of the 1950s. It scored six Oscar nominations: best picture, best actress for Elizabeth Taylor as Maggie the Cat, best director for Brooks, best adapted screenplay for Brooks and James Poe best color cinematography for William Daniels and best actor for Paul Newman as Brick, Newman's first nomination and the film that truly cemented him as a star.

After the success of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Brooks decided to take an ocean voyage to Europe as a vacation. The writer-director packed the essentials for a lengthy trip: some articles on evangelism, a Gideon Bible a copy of Sinclair Lewis' novel Elmer Gantry and Angie Dickinson. By the time the ship docked in Europe, a first draft of a screenplay, based on the novel by one of the men who stood ready to

defend Brooks during The Brick Foxhole brouhaha with the Marines, lay finished. Dickinson, on the other hand, departed the cruise quite a while back, having grown annoyed by Brooks ignoring her for Elmer. For many lives, 1960 would prove quite eventful either professionally, personally or both. Brooks filmed the highly entertaining movie version of Elmer Gantry early in the year, directing one of his best friends, Burt Lancaster, for the first time in the title role, which is good since the film got made under the auspices of an independent Burt Lancaster/Richard Brooks Production. Lancaster gives one of his best performances and won his first Oscar. The film co-starred Jean Simmons, giving one of her greatest, most mesmerizing turns as Sister Sharon Falconer, the traveling tent show evangelist who gets Elmer into the biz. She fell for Brooks on the set. Within the calendar year, she ended her unhappy marriage to Stewart Granger and became Brooks' wife. Unfortunately, when the Oscar nominations came out the next year, Simmons got left out of the nominations for Elmer Gantry. It received five total. In addition to Lancaster's nomination and win for best actor, it received nominations for best picture; Shirley Jones as supporting actress, which she won; Andre Previn for best score for a drama or comedy; and Brooks for best adapted screenplay. That cruise paid off. Brooks won an Oscar and found a wife. Below, a bit of Lancaster at work — and singing too.

defend Brooks during The Brick Foxhole brouhaha with the Marines, lay finished. Dickinson, on the other hand, departed the cruise quite a while back, having grown annoyed by Brooks ignoring her for Elmer. For many lives, 1960 would prove quite eventful either professionally, personally or both. Brooks filmed the highly entertaining movie version of Elmer Gantry early in the year, directing one of his best friends, Burt Lancaster, for the first time in the title role, which is good since the film got made under the auspices of an independent Burt Lancaster/Richard Brooks Production. Lancaster gives one of his best performances and won his first Oscar. The film co-starred Jean Simmons, giving one of her greatest, most mesmerizing turns as Sister Sharon Falconer, the traveling tent show evangelist who gets Elmer into the biz. She fell for Brooks on the set. Within the calendar year, she ended her unhappy marriage to Stewart Granger and became Brooks' wife. Unfortunately, when the Oscar nominations came out the next year, Simmons got left out of the nominations for Elmer Gantry. It received five total. In addition to Lancaster's nomination and win for best actor, it received nominations for best picture; Shirley Jones as supporting actress, which she won; Andre Previn for best score for a drama or comedy; and Brooks for best adapted screenplay. That cruise paid off. Brooks won an Oscar and found a wife. Below, a bit of Lancaster at work — and singing too.With his next film, Brooks finally received the key that unlocked the leg shackles that bound him to MGM. The studio once again assigned him to a Tennessee Williams play. Though Sweet Bird of Youth did moderately well on Broadway, it wasn't one of The Glorious Bird's triumphs and took a long time to get to New York, starting as a one-act, premiering as a full-length play with a reviled ending in Florida in 1956 and, finally, the revised version's

opening in NY in 1959. (The play has yet to be revived on Broadway whereas, in contrast, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof has been revived four times, including twice in this young century, and A Streetcar Named Desire 's eighth Broadway revival currently runs.) Originally, its plot concerned a retired actress and a gigolo with dreams of Hollywood who brings her to his old Southern hometown to get away and runs into trouble with the town's corrupt political boss (Ed Begley) when he woos his daughter (Shirley Knight). Williams said he'd hoped for Brando and Magnani to play the parts on stage. Eventually, she became merely an aging actress and Geraldine Page and Paul Newman played the leads on Broadway. When it came time for the movie, according to legend, MGM desperately wanted Elvis for Newman's part, but the Colonel nixed that because he didn't like the character's morals. Instead, the great Page and Newman repeated their stage roles as did Rip Torn as the son of the political boss. Once again, Hollywood castrated a Williams play or, in this instance, literally didn't castrate it (people who know both the play and movie get that joke. Page and Knight received Oscar nominations in the lead and supporting actress categories, respectively, and Begley won as best supporting actor. In this clip, you can see Newman's Chance try to get a handle on Page's wasted Alexandra in their hotel room.

opening in NY in 1959. (The play has yet to be revived on Broadway whereas, in contrast, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof has been revived four times, including twice in this young century, and A Streetcar Named Desire 's eighth Broadway revival currently runs.) Originally, its plot concerned a retired actress and a gigolo with dreams of Hollywood who brings her to his old Southern hometown to get away and runs into trouble with the town's corrupt political boss (Ed Begley) when he woos his daughter (Shirley Knight). Williams said he'd hoped for Brando and Magnani to play the parts on stage. Eventually, she became merely an aging actress and Geraldine Page and Paul Newman played the leads on Broadway. When it came time for the movie, according to legend, MGM desperately wanted Elvis for Newman's part, but the Colonel nixed that because he didn't like the character's morals. Instead, the great Page and Newman repeated their stage roles as did Rip Torn as the son of the political boss. Once again, Hollywood castrated a Williams play or, in this instance, literally didn't castrate it (people who know both the play and movie get that joke. Page and Knight received Oscar nominations in the lead and supporting actress categories, respectively, and Begley won as best supporting actor. In this clip, you can see Newman's Chance try to get a handle on Page's wasted Alexandra in their hotel room.

Now a free agent, Brooks decided to stay that way — in essence becoming an independent filmmaker toward the end of his career instead of the beginning, as the path usually goes. He also defied that typical indie move of starting small — this wasn't John Cassavetes — but beginning this stage of his career more like the final films (and current ones for 1965) of David Lean. He went BIG. He even nabbed Lean's Lawrence to star in his adaptation of Joseph Conrad's Lord Jim, a longtime obsession of Brooks that he bought the rights to in 1958 for a mere $6,500. The filming took place in Hong Kong, Singapore and, dangerously in Cambodia as things grew tense. The movie crew's interpreter happened to be Dith Pran, the man the late Haing S. Ngor won an Oscar for playing in Roland Joffe's 1984 film The Killing Fields. O'Toole hated his time there, complaining about the living conditions — he isn't a fan of mosquitoes and snakes. Later, he also admitted he thought he'd been wrong for the part itself. Portions of the film ended up shot in London's Shepperton Studios as Cambodia became full of anti-American rage. When the film opened, it bombed and badly. Sony put it on DVD briefly, but it's currently out of print so, alas, I've never seen this one. Brooks did make an impression on O'Toole though, who told Variety when he died that Brooks was "the man who lived at the top of his voice."

Having a flop on the scale of Lord Jim the first time you produce your own film could really discourage a guy. However, it sure didn't show in what he produced next because The Professionals turned out to be the most well-made, entertaining film he'd directed up until this point in his career. (His next film swipes the most well-made title, but The Professionals continues to hold the prize for being one hell of a ride.) Based on a novel by Frank O'Rourke, the movie teamed Brooks with his pal Lancaster again. Set soon after the 1917 Mexican Revolution, early in the 20th century when the Old West and modern movement intermingle near the U.S.-Mexican border, it almost plays like a rough draft for Sam Peckinpah's admittedly superior Wild Bunch. Ralph Bellamy plays a rich tycoon who hires a team of soldiers of fortune to go in to Mexico and rescue his daughter who has been kidnapped by a guerrilla bandit (Jack Palance, hysterically funny and good despite making no attempt to appear Mexican). The team consists of Lancaster as a dynamite expert, Lee Marvin as a professional soldier, Robert Ryan as a wrangler and packmaster and Woody Strode as the team's scout and tracker. The film turned out to be a huge hit with audiences and critics alike and earned Brooks Oscar nominations for directing and adapted screenplay. The Academy also cited the cinematography of its director of photography, the master Conrad L. Hall, who would do some of the finest work of his career in Brooks' next film. Below, one of The Professionals' action sequences.

I hoped to complete this in two parts and considered breaking out the next film as a separate review because In Cold Blood stands firmly as Richard Brooks' masterpiece (and then there remain some other films to mention after that). So, another temporary pause.

Tweet

Labels: Angie Dickinson, Bellamy, Bette, Borgnine, Chayefsky, Debbie Reynolds, Geraldine Page, Jean Simmons, Lancaster, Lee J. Cobb, Liz, Marvin, Newman, O'Toole, Peckinpah, Rip Torn, Shatner, Tennessee Williams, Vidal

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, May 18, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part I

By Edward Copeland

"First comes the word, then comes the rest" might be the most famous quote attributed to Richard Brooks, who began his life 100 years ago today in Philadelphia as Ruben Sax, son of Jewish immigrants Hyman and Esther Sax. He wrote a lot of words too — sometimes using only images. In fact, too many to tell the story in a single post. so it will be three. His parents came from Crimea in 1908 when it belonged to the Russian Empire. Like the parents of a great director of a much later generation and an Italian Catholic heritage, Hyman and Esther Sax also worked in the textile and clothing industry. Sax's entire adult working life revolved around the written word — even while he busied himself with other tasks. “I write in toilets, on planes, when I’m

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

Though Brooks' legend derives predominantly from his film legacy, he experienced his first rush of acclaim with the publication of his debut novel, written while stationed at Quantico at night in the bathroom, according to the account in Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks by Douglass K. Daniel. Several publishers rejected it until Edward Aswell at Harper & Brothers, who also edited Thomas Wolfe, agreed to take it — and he shocked Brooks further by telling him (after a few suggestions) they planned to publish in May 1945. This news flabbergasted Brooks who obtained a weekend pass to go to New York because Aswell insisted on informing him in person. Now Brooks had to return to Quantico where the top officers of the Corps about shit bricks when The New York Times published a big review of The Brick Foxhole soon after it hit shelves. (Orville Prescott's take was mixed, assessing it as compulsively readable but weak on characterization.) Its story of hate and intolerance within the Marines brought threats of court-martialing Brooks, since he'd ignored procedure and never submitted the novel to Marine officials for approval ahead of time. They wanted to avoid bad publicity, especially with all the good feelings as the war wound down. "There was nothing in that book that violated security, but their rules and regulations were not for that purpose alone," Brooks told Daniel. Aswell prepared to launch a P.R. counteroffensive with literary giants such as Sinclair Lewis and Richard Wright ready to stand by Brooks. In case you don't know the story of the novel, it concerns a Marine unit in its barracks and on leave in Washington. Through their wartime experiences, some of the men truly turned ugly, suspecting cheating wives and tossing hate against any non-white Christian. It turns out, though the real Marines let the matter drop, what bothered them

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

While he didn't want to make a movie of The Brick Foxhole himself, another former newspaperman turned socially conscious film artist met with Brooks about working with his independent production company. At first, Mark Hellinger tried to lure Brooks away from Universal with the promise of doubling his salary if he'd adapt a play he liked into a movie, but before Brooks could consider that offer, Hellinger called with a more pressing matter. He was producing an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's famous short story The Killers. The problem: someone had to dream up what happened after the brief tale ends because it certainly wouldn't last 90 minutes otherwise. Hellinger flew Brooks out to meet Papa himself, but he didn't get much out of him but he did come up with an idea for what would happen after the story ends. Hellinger liked it and sent it to John Huston, who wrote the screenplay as a favor. Since both Brooks and Huston had contracts at other studios, neither got screen credits, so Ernest Hemingway's The Killers' official screenplay credit goes to Anthony Veiller, who received an Oscar nomination for best screenplay. He'd previously shared a nomination in the same category for Stage Door. The film also made a star out of Burt Lancaster, who would work with Brooks several times and be his lifelong friend. In fact, Lancaster would star in the next screenplay that Brooks wrote, a Mark Hellinger production directed by one of those people Edward Dmytryk eventually would name before the House Un-American Activities Committee. The film, of course, would be the still-powerful Brute Force, the director, Jules Dassin.

John Huston wasn't happy. Producer Jerry Wald called him, excitement in his voice, to tell him he'd secured the rights to Maxwell Anderson's Broadway play Key Largo for Huston to direct. This didn't thrill Huston, who thought the play gave new meaning to the word awful. Written in blank verse, Anderson's play concerned a deserter from the Spanish-American War. People at a hotel do get taken hostage, but by Mexican hostages. Essentially, Huston tossed the play in the trash bin. Huston hired Brooks to co-write an in-title only version and, still pissed at Wald, barred him from the set. Part of Huston's anger stemmed from the HUAC nonsense, (His outrage would drive him to move to Ireland for a large part of the 1950s.) so he couldn't stomach adapting a play by Anderson whom he considered a reactionary because of his hate of FDR. Despite Huston's distaste for the project, he

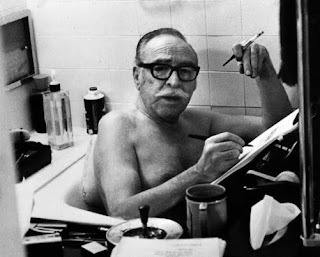

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.While I would have liked to have viewed more of Brooks' work that I've never seen (and to re-visit some which I have), time and availability, combined with his prolific nature and the industry's increasingly cavalier willingness to let both old and recent films fade into oblivion, proved to be a problem. After Huston's generosity, Brooks' directing debut would arrive two years later. Four films where Brooks worked

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.

enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.With 1955, Brooks wrote and directed the first film that truly garnered him an identity as more than a writer who directs but as a director with Blackboard Jungle, a film that admittedly manages to look both dated and timely simultanouesly, First, as so many old films did, it had to start with a long scroll explaining that American schools maintain high standards, but we need to worry about these juvenile

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk.

desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk. Tweet

Labels: blacklist, Bogart, Capra, Cary, Dassin, Doris Day, Edward G., Fiction, Fitzgerald, Fuller, Ginger Rogers, Glenn Ford, Hemingway, Huston, Lancaster, Liz, Mazursky, Poitier, Robert Ryan, Widmark

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, October 22, 2011

"A person can't sneeze in this town without someone offering them a handkerchief"

How come you treat me like a worn-out shoe?

My hair's still curly and my eyes are still blue

Why don't you love me like you used to do?

•••

Well, why don't you be just like you used to be?

How come you find so many faults with me?

Somebody's changed so let me give you a clue

Why don't you love me like you used to do?

By Edward Copeland

Even if Hank Williams Sr. weren't well represented with songs that play throughout Peter Bogdanovich's film adaptation of Larry McMurtry's novel The Last Picture Show, somehow I think the movie would play as if it were a cinematic evocation of the music legend. Despite the fact that today marks the 40th anniversary of the film's release and The Last Picture Show took as its setting a small, depressed Texas town in 1951 and 1952 (even going so far as to have cinematographer Robert Surtees shoot it in glorious black & white), it contains a universality that resonates today both in human and economic terms. Williams' hit "Why Don't You Love Me (Like You Used to Do)?" that I quote partially above are the first words we hear, before any character speaks a line. In the movie's context, the lyrics could be describing the first person we see — high school senior Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms). With the way the U.S. has been going of late, I know very few people who don't feel like a "worn-out shoe" and wish fondly for past, better days and these feelings stretch from one end of the ideological spectrum to the other. Fortunately, The Last Picture Show itself hasn't changed. Age has served the film well, helped in no small part by its amazing cast.

McMurtry, who based the town in the novel on his own small north Texas hometown of Archer City, co-wrote the screenplay with Bogdanovich, the former film critic who was directing his second credited feature film after the fun and tawdry thriller Targets that gave Boris Karloff a great, late career role. (Under the name Derek Thomas, he had filmed a sci-fi feature called Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women in 1968 starring Mamie Van Doren.) In the novel, McMurtry renamed the town Thalia, but the film gave it another moniker — Anarene.

The movie opens on Anarene's main stretch of road and passes the Royal movie theater. The wind howls ferociously, blowing dust, leaves, trash and anything that isn't tied down through the air and down the street. The flying debris leads us to Sonny and that Hank Williams song, which comes from the radio of his old pickup that he's having a helluva time getting started. Actually, the pickup only half belongs to

Sonny — he shares it with his best friend Duane Moore (Jeff Bridges), who always seems to get it first on date nights so he can neck with his girlfriend, Jacy Farrow (Cybill Shepherd in her film debut), widely considered the best-looking teen in town. Once Sonny gets that old pickup running, he spots young Billy (the late Sam Bottoms, Timothy's real-life younger brother) standing in the middle of the street with his broom, trying to sweep up the dust. Sonny honks at him and Billy smiles and climbs in the pickup with him. As he usually does, Sonny affectionately turns the mentally challenged boy's cap around backward and the two head to the pool hall owned by Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson). Sonny pays for what looks like a sticky bun and a bottle of pop, prompting Sam to shake his head. "You ain't ever gonna amount to nothing. Already spent a dime this morning, ain't even had a decent breakfast," Sam tells Sonny, but not in a mean-spirited way. "Why don't you comb you hair, Sonny? It sticks up…I'm surprised you had the nerve to show up this morning after that stomping y'all took last night." Sam's referring to Anarene High School's final football game of the year, where the team took a real beating. "It could've been worse," Sonny replies. "You could say that just about everything," Sam says.

Sonny — he shares it with his best friend Duane Moore (Jeff Bridges), who always seems to get it first on date nights so he can neck with his girlfriend, Jacy Farrow (Cybill Shepherd in her film debut), widely considered the best-looking teen in town. Once Sonny gets that old pickup running, he spots young Billy (the late Sam Bottoms, Timothy's real-life younger brother) standing in the middle of the street with his broom, trying to sweep up the dust. Sonny honks at him and Billy smiles and climbs in the pickup with him. As he usually does, Sonny affectionately turns the mentally challenged boy's cap around backward and the two head to the pool hall owned by Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson). Sonny pays for what looks like a sticky bun and a bottle of pop, prompting Sam to shake his head. "You ain't ever gonna amount to nothing. Already spent a dime this morning, ain't even had a decent breakfast," Sam tells Sonny, but not in a mean-spirited way. "Why don't you comb you hair, Sonny? It sticks up…I'm surprised you had the nerve to show up this morning after that stomping y'all took last night." Sam's referring to Anarene High School's final football game of the year, where the team took a real beating. "It could've been worse," Sonny replies. "You could say that just about everything," Sam says. "It could've been worse" applies to most of the situations in The Last Picture Show, which can be described accurately by the overused phrase "slice of life." Plot doesn't drive the story — character, not only of the people but of the town itself, does. While you watch the movie, you aren't concerned with what happens next or how the film ends because you realize that life will go on for most of these fictional folks you've come to know even after the lights come up in the theater and the projector shuts off. Wherever the movie finishes will resemble a chapter stop more than a finale. (As if to prove the point, McMurtry returned to Thalia in four more novels, though Duane becomes the main character in the followups as opposed to Sonny, who decidedly takes the lead here. Bogdanovich even filmed the first sequel, Texasville, in 1990 with mixed results.)

Sam's reference to the previous night's football debacle displays an excellent example of what captivates the citizens in a so-called "one-stoplight" town such as Amarene, as the team's players (mainly Sonny and Duane, since they are the teammates we know best) get repeatedly berated by their elders the day after the loss. A common refrain becomes variations of the question, "Have you ever heard of tackling?" That even continues when Abilene (Clu Gulager), one of the many oil-field workers who live in Amarene, when he comes straight from work to Sam's pool hall, changes clothes and takes billiards so seriously that he has his own cue stick that he keeps in a case and assembles. While he's there, he collects on a bet he had with Sam on the game. Abilene isn't faithful in most areas of his life and that's telegraphed right away when we see that he'd bet against the hometown high school football team. "You see? This is what I get for bettin' on my own hometown ballteam. I ought'a have better sense," Sam says as he forks over the cash. "Wouldn't hurt to have a better hometown," the emotionless Abilene declares. Soon enough, football will fade from the town's collective memory as they move into basketball season. While sports may be important in holding this dying town

together, we never see an actual game of any kind. The closest we come is one instance of basketball practice in the school gym. That's because high school sporting events aren't what The Last Picture Show wants to show us. It's telling a coming-of-age story — several in fact — and not all concern the teen characters in the tale. It's also about love and loss, not always in the present tense. Of course, at its core, The Last Picture Show also deals with community and by community, I mean gossip. In this small a town, very few secrets can be kept, yet at the same time its citizens seem fairly discreet about what they know and staying out of other people's business. I've never read the novel, but I can see how easily it would work in book form. There's a story that Bogdanovich, who was then married to multi-hyphenate Polly Platt, who died earlier this year, read the jacket cover of the book and didn't see a way it could work as a film until Platt outlined it for him in chronological form. She must have done a brilliant job since she not only changed Bogdanovich's mind but led him to the road where he ended up directing and co-writing one of the best films of all time. the balancing act needed to transfer The Last Picture Show to the screen would have been very tricky for anyone to pull off, but I think the reason it worked boiled down to two key elements: its look and its cast.

together, we never see an actual game of any kind. The closest we come is one instance of basketball practice in the school gym. That's because high school sporting events aren't what The Last Picture Show wants to show us. It's telling a coming-of-age story — several in fact — and not all concern the teen characters in the tale. It's also about love and loss, not always in the present tense. Of course, at its core, The Last Picture Show also deals with community and by community, I mean gossip. In this small a town, very few secrets can be kept, yet at the same time its citizens seem fairly discreet about what they know and staying out of other people's business. I've never read the novel, but I can see how easily it would work in book form. There's a story that Bogdanovich, who was then married to multi-hyphenate Polly Platt, who died earlier this year, read the jacket cover of the book and didn't see a way it could work as a film until Platt outlined it for him in chronological form. She must have done a brilliant job since she not only changed Bogdanovich's mind but led him to the road where he ended up directing and co-writing one of the best films of all time. the balancing act needed to transfer The Last Picture Show to the screen would have been very tricky for anyone to pull off, but I think the reason it worked boiled down to two key elements: its look and its cast.Platt, in addition to being the person who gave Bogdanovich the vision to turn McMurtry's novel into a feature film also served as the film's production designer and its uncredited costume designer, seamlessly taking the actors and Archer City, Texas, back in time nearly 20 years. Her work was helped in no small part by the legendary director of photography Robert Surtees' exquisite black & white images, which earned one of The Last Picture Show's eight Oscar nominations. Surtees received a total of 15 Oscar nominations for

cinematography in his career and won three: for King Solomon's Mines, The Bad and the Beautiful and Ben-Hur. He actually lost twice in 1971 — he was nominated for Summer of '42 as well as The Last Picture Show. He earned four consecutive nominations from 1975-78, when he made his last film before he retired. Other nominations included The Sting, The Graduate and Oklahoma! He showed a strong gift for using both color and black & white and his stark look in The Last Picture Show perfectly captured the time and place of the setting without letting any nostalgia sneak into the proceedings, which it really shouldn't. No one is looking back at the events from the future, so that element shouldn't be there. In a way, it's interesting to compare it to George Lucas' American Graffiti two years later. Both films look at high school seniors and eschew musical scores in favor of soundtracks full of the pop hits of the era. The difference is that Graffiti, while good, revels in a "good old days" spirit with barely a mention of sexual curiosity let alone activity while The Last Picture Show depicts an entirely different economic class that's having very few good times, but certainly getting drunk and laid. Of course, adults didn't exist in Graffiti whereas their roles prove integral in The Last Picture Show. Admittedly, I haven't seen American Graffiti in some time — Lucas hasn't re-edited it to make the drag race CGI and digitally replaced all the cars out cruising with hybrids, has he?

cinematography in his career and won three: for King Solomon's Mines, The Bad and the Beautiful and Ben-Hur. He actually lost twice in 1971 — he was nominated for Summer of '42 as well as The Last Picture Show. He earned four consecutive nominations from 1975-78, when he made his last film before he retired. Other nominations included The Sting, The Graduate and Oklahoma! He showed a strong gift for using both color and black & white and his stark look in The Last Picture Show perfectly captured the time and place of the setting without letting any nostalgia sneak into the proceedings, which it really shouldn't. No one is looking back at the events from the future, so that element shouldn't be there. In a way, it's interesting to compare it to George Lucas' American Graffiti two years later. Both films look at high school seniors and eschew musical scores in favor of soundtracks full of the pop hits of the era. The difference is that Graffiti, while good, revels in a "good old days" spirit with barely a mention of sexual curiosity let alone activity while The Last Picture Show depicts an entirely different economic class that's having very few good times, but certainly getting drunk and laid. Of course, adults didn't exist in Graffiti whereas their roles prove integral in The Last Picture Show. Admittedly, I haven't seen American Graffiti in some time — Lucas hasn't re-edited it to make the drag race CGI and digitally replaced all the cars out cruising with hybrids, has he?

Despite the film's ensemble nature, Sonny truly serves as the center of this movie's universe. Timothy Bottoms wears such deep, soulful eyes that it made him a natural to play a role that required deadpan humor as well heartbreaking drama. While the other younger cast members mostly continue to flourish in the industry if we can still count Randy Quaid, who made his film debut as Lester Marlow, a rich kid from Wichita Falls who lures Shepherd's Jacy to a nude swimming party, but has now transformed himself from a talented character actor into a fugitive from justice on the run with his wife and being pursued by Dog the Bounty Hunter), Bottoms' star never seemed to take off after such a promising start. The Last Picture Show was his second feature following Dalton Trumbo's Johnny Got His Gun and in 1973 he starred in The Paper Chase, but it has been mostly TV. low budget movies and downhill since then. (I suppose his most recent highlight was playing the title character in Trey Parker and Matt Stone's short-lived Comedy Central sitcom That's My Bush!) It's a shame because he's the key to so much of The Last Picture Show. Of those eight Oscar nominations that I mentioned it received, four went to acting and two won. All were much deserved, but Bottoms deserved a slot as well. I didn't add it up, but I imagine he appears in a great majority of the movie's scenes and a case could have easily been made for pushing him for lead — not that he stood a chance to win against Gene Hackman in The French Connection, but I would have nominated him before Walter Matthau in Kotch, George C. Scott in The Hospital or Topol in Fiddler on the Roof. However, I don't know if I could have evicted Peter Finch in Sunday Bloody Sunday for him.

Bottoms' Sonny though really serves as the line upon which so much of the movie's clothing hangs to dry. He's the first character we meet, introducing us to Billy, whose origin never gets explained, and more importantly Johnson's Oscar-winning Sam the Lion, who not only owns the pool hall but the diner and the Royal movie theater as well. Sonny takes us to the Royal for the first time, arriving late because of his delivery job. Miss Mosey (Jessie Lee Fulton), the kindly manager of the place who never has popcorn since she long ago forgot how the machine worked, tells Sonny that he already missed the newsreel and the comedy and the feature has started, so she only charges him 30 cents for admission. Imagine being able to see a movie for that cheap — and I imagine it wasn't that much more to get two movies and a newsreel, Now, the prices go up and up and up while, in general, the quality goes down further and

further. Once inside, he hooks up with his girlfriend Charlene Duggs (Sharon Taggart), who gets annoyed that he doesn't realize what an important day it is. It seems it's their one-year anniversary of going steady. With that perfect deadpan aplomb I mentioned earlier, Bottoms as Sonny simply says, "Seems longer." The main feature playing that night is Father of the Bride starring Spencer Tracy and Elizabeth Taylor. Though Sonny and Charlene have relocated to the back row so they can make out, it's clear that Sonny finds the giant image of Liz Taylor more alluring than the girl who is kissing him, While we met Duane earlier when he got off work from the oil field and went to the diner with Sonny, he and Jacy show up and take the seats in front of them and it's clear that Duane finds it very satisfying to be kissing Jacy because they don't seem to be watching the movie at all. When the movie is over and all the kids exit, they tell Miss Mosey they enjoyed it, but I bet they wouldn't want to take a quiz on it. However, that wind still howls giving the older woman trouble putting up the poster for the next attraction so Sam gives her a hand teasing the return of Sands of Iwo Jima starring John Wayne. The town can boast having a movie theater, but it certainly isn't first run. After the show, Duane lets Sonny have the pickup, so he drives Charlene out by the lake and they begin to make out. You can tell this is a choreographed routine for the teens because Charlene immediately unhooks her bra and hangs it from the rearview mirror, which is followed immediately by Sonny's hands going to her bare breasts as if they were magnets and her chest was built out of metal. Charlene complains that something's wrong

further. Once inside, he hooks up with his girlfriend Charlene Duggs (Sharon Taggart), who gets annoyed that he doesn't realize what an important day it is. It seems it's their one-year anniversary of going steady. With that perfect deadpan aplomb I mentioned earlier, Bottoms as Sonny simply says, "Seems longer." The main feature playing that night is Father of the Bride starring Spencer Tracy and Elizabeth Taylor. Though Sonny and Charlene have relocated to the back row so they can make out, it's clear that Sonny finds the giant image of Liz Taylor more alluring than the girl who is kissing him, While we met Duane earlier when he got off work from the oil field and went to the diner with Sonny, he and Jacy show up and take the seats in front of them and it's clear that Duane finds it very satisfying to be kissing Jacy because they don't seem to be watching the movie at all. When the movie is over and all the kids exit, they tell Miss Mosey they enjoyed it, but I bet they wouldn't want to take a quiz on it. However, that wind still howls giving the older woman trouble putting up the poster for the next attraction so Sam gives her a hand teasing the return of Sands of Iwo Jima starring John Wayne. The town can boast having a movie theater, but it certainly isn't first run. After the show, Duane lets Sonny have the pickup, so he drives Charlene out by the lake and they begin to make out. You can tell this is a choreographed routine for the teens because Charlene immediately unhooks her bra and hangs it from the rearview mirror, which is followed immediately by Sonny's hands going to her bare breasts as if they were magnets and her chest was built out of metal. Charlene complains that something's wrong with Sonny — that he's acting as if he's bored or would rather be somewhere else. However, when Sonny does venture to place his hand somewhere else, Charlene goes nuts. "You cheapskate — you didn't even get me an anniversary present. Now, you want to get me pregnant," she barks as she starts to put her top back on. Sonny argues that it was only his hand, but she says she knows how one thing leads to another and she's waiting until she gets married. Sonny, a hangdog expression on his face, tells her that they should break up then. This shocks Charlene, but she gets mad, not upset. "Now don't go tellin' all the boys how hot I was," she warns him. "You wasn't that hot," Sonny sighs sadly in a monotone. He can't decide if he's depressed or relieved to be rid of Charlene when he shows up at the diner and tells the ever faithful manager/waitress Genevieve (the great Eileen Brennan) about it. "Jacy's the only pretty girl in town and Duane's got her," Sonny tells her. "Jacy will bring you more misery than she'll ever be worth," Genevieve declares. What a font of wisdom her character will turn out to be. Sonny remembers hearing the news that Genevieve's husband Dan finally is able to return to work, so he figures that means she won't be working much longer. In another moment from a 1971 film set in 1951 that could be taking place in 2011, she responds, "We've got four thousand dollars in doctor bills to pay. I'll probably be making cheeseburgers for your grandkids." If the bills are that high in 1951, calculate them now.