Monday, May 21, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part III

By Edward Copeland

It isn't often that a masterpiece of literature begets a masterpiece of cinema yet both retain distinct identities all their own, but that's the case with In Cold Blood, Truman Capote's "nonfiction novel" and Richard Brooks' stunning film adaptation of his book. Capote often gets credit for inventing the genre of adapting the techniques of a novelist to that of straight reporting, but earlier attempts existed — Capote's stood out because In Cold Blood 's excellence made everyone forget any other examples (at least until more than a decade later when Norman Mailer added his own brilliant take on the genre with The Executioner's Song). Brooks, with his job as a crime reporter in his past, on the surface appears to follow Capote's approach, but the director, forever the activist, skips the objectivity that Capote tried to evoke in his book. Brooks didn't want to minimize the horror of the crime that occurred at the Clutter farm in Holcomb, Kans., but he also wanted to humanize the killers, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. In a way, Brooks' film inspired the path for the two films made decades later telling the story of Capote's writing of the book and his getting to know the killers first-hand as they waited on Death Row. Even today, Brooks' 1967 film remains more powerful and better made than the two more recent tales. Undoubtedly, In Cold Blood remains Brooks' greatest film. If you got here before reading either Part I or Part II of this tribute, click on the respective links.

The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call "out there." Some seventy miles east of the Colorado border, the countryside, with its hard blue skies and desert-clear air, has an atmosphere that is rather more Far West than Middle West. The local accent is barbed with a prairie twang, a ranch-hand nasalness, and the men, many of them, wear narrow frontier trousers, Stetsons, and high-heeled boots with pointed toes. The land is flat, and the views are awesomely extensive; horses, herds of cattle, a white cluster of grain elevators rising as gracefully as Greek temples are visible long before a traveler reaches them.

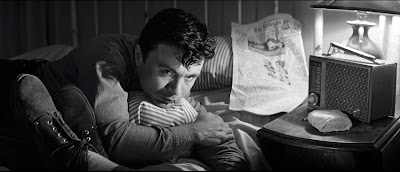

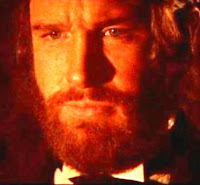

Capote begins his book with that paragraph in the first chapter titled The Last to See Them Alive. Brooks begins the film of In Cold Blood introducing us to The Last to See Them Alive in the forms of Robert Blake as newly paroled inmate Perry Smith and Scott Wilson as an acquaintance he met in prison who had been freed earlier, Dick Hickok. Brooks gives Blake — and the movie — a memorable entrance, especially thanks to his decision to go against the grain of the time and film in black-and-white Panavision. We see a bus driving down a two-lane highway, passing signs showing the distance to different Kansas towns, including the horrific Olathe. On the bus, a young female stumbles down the aisle to get a closer look at the pair of pointed-toe cowboy boots with buckles on its heels before creeping back. The shadowy man who wears the boots also has a guitar strung around his neck. A flame suddenly illuminates Robert Blake's face as he lights a cigarette and Quincy Jones' ominous yet jazzy score kicks in to start the credits. The sequence not only sets the tone for the film that follows, it also introduces us to the movie's most important participant — cinematographer Conrad L. Hall (though he didn't need to use the L. yet since his son, Conrad W. Hall, wasn't old enough to follow his dad into the business).

The movie spends its opening minutes introducing us to the soft-spoken Perry and getting him hooked up with Dick. Whereas Blake's Perry comes off as a puppy repeatedly kicked by his owner, Scott Wilson portrays Hickok as a cocky, livewire and a chatterbox — and Brooks gives him great lines, especially in the scenes where he and Blake drive around. "Ever seen a millionaire fry in the electric chair? Hell, no. There's two kinds of laws, one for the rich and one for the poor," Dick imparts as wisdom to Perry. When the two buy supplies for the planned robbery of the Clutter farm, Dick shoplifts some razorblades for no good reason, leading Perry to chastise him for taking such a risk for something so small. "That was stupid — stealin' a lousy pack of razor blades! To prove what?" Perry asks. Smiling, Dick replies, "It's the national pastime, baby, stealin' and cheatin'. If they ever count every cheatin' wife and tax chiseler, the whole country would be behind prison walls." Though in the two recent biographical films about Truman Capote's research into the case, it's strongly implied that Capote at least developed a crush on Smith and that Perry may have been gay. In Cold Blood never explicltly claims that Perry Smith was gay, but throughout the film Dick taunts him by

calling him "honey," "baby" or something along those lines. Hickock on the other hand chases every skirt he gets near and during the robbery/murder, Perry intervenes to stop Dick from raping the Clutters' 16-year-old daughter Nancy (Brenda Currin). Wilson made his first two feature films in 1967 and he landed roles in two of the biggest — this one and the eventual Oscar winner for best picture, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night. The jaws of younger readers should hit the floor when they see Wilson's great work here and it slowly dawns on them that playing Dick Hickok is a younger incarnation of Herschel on AMC's The Walking Dead. When Perry and Dick do get together, they meet at Dick's father's house where Dick tries to aid his old man, who's slowly losing his battle with terminal cancer. (Veteran character actor Jeff Corey, who co-starred in the Brooks-scripted 1947 classic Brute Force, plays the elder Hickock.) Contrasting Capote's take with Brooks' version fascinates in the ways the works reflect each other yet, like a mirror, many things appear on the opposite side. The book introduces its readers to the Clutter family first before Perry and Dick enter the story (by name anyway). Brooks' screenplay reverses the order, beginning with the killers then letting us meet the Kansas family. However, both aim to draw parallels between the victims and their eventual murderers. "That morning an apple and a glass of milk were enough for him; because

calling him "honey," "baby" or something along those lines. Hickock on the other hand chases every skirt he gets near and during the robbery/murder, Perry intervenes to stop Dick from raping the Clutters' 16-year-old daughter Nancy (Brenda Currin). Wilson made his first two feature films in 1967 and he landed roles in two of the biggest — this one and the eventual Oscar winner for best picture, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night. The jaws of younger readers should hit the floor when they see Wilson's great work here and it slowly dawns on them that playing Dick Hickok is a younger incarnation of Herschel on AMC's The Walking Dead. When Perry and Dick do get together, they meet at Dick's father's house where Dick tries to aid his old man, who's slowly losing his battle with terminal cancer. (Veteran character actor Jeff Corey, who co-starred in the Brooks-scripted 1947 classic Brute Force, plays the elder Hickock.) Contrasting Capote's take with Brooks' version fascinates in the ways the works reflect each other yet, like a mirror, many things appear on the opposite side. The book introduces its readers to the Clutter family first before Perry and Dick enter the story (by name anyway). Brooks' screenplay reverses the order, beginning with the killers then letting us meet the Kansas family. However, both aim to draw parallels between the victims and their eventual murderers. "That morning an apple and a glass of milk were enough for him; because he touched neither coffee or tea, he was accustomed to begin the day on a cold stomach. The truth was he opposed all stimulants, however gentle. He did not smoke, and of course he did not drink; indeed, he had never tasted spirits, and was inclined to avoid people who had — a circumstance that did not shrink his social circle as much as might be supposed, for the center of that circle was supplied by the members of Garden City's First Methodist Church, a congregation totaling seventeen hundred, most of whom were as abstemious as Mr. Clutter could desire," Capote described the Clutter patriarch. A few pages later in the first chapter, Perry Smith makes his entrance into Capote's book. "Like Mr. Clutter, the young man breakfasting in a cafe called the Little Jewel never drank coffee. He preferred root beer. Three aspirin, cold root beer, and a chain of Pall Mall cigarettes — that was his notion of a proper "chow-down." Sipping and smoking, he studied a map spread on the counter before him — a Phillips 66 map of Mexico — but it was difficult to concentrate, for he was expecting a friend, and the friend was late. He looked out a window at the silent small-town street, a street he had never seen until yesterday. Still no sign of Dick," Capote wrote. Brooks uses a visual link to draw victim and killer together, showing Herbert Clutter (John McLiam) performing his morning shave. As Clutter leans into the sink to rinse the remaining shaving cream from his face, the face that rises up and looks in the mirror sees Perry Smith, excising his excess whiskers as well.

he touched neither coffee or tea, he was accustomed to begin the day on a cold stomach. The truth was he opposed all stimulants, however gentle. He did not smoke, and of course he did not drink; indeed, he had never tasted spirits, and was inclined to avoid people who had — a circumstance that did not shrink his social circle as much as might be supposed, for the center of that circle was supplied by the members of Garden City's First Methodist Church, a congregation totaling seventeen hundred, most of whom were as abstemious as Mr. Clutter could desire," Capote described the Clutter patriarch. A few pages later in the first chapter, Perry Smith makes his entrance into Capote's book. "Like Mr. Clutter, the young man breakfasting in a cafe called the Little Jewel never drank coffee. He preferred root beer. Three aspirin, cold root beer, and a chain of Pall Mall cigarettes — that was his notion of a proper "chow-down." Sipping and smoking, he studied a map spread on the counter before him — a Phillips 66 map of Mexico — but it was difficult to concentrate, for he was expecting a friend, and the friend was late. He looked out a window at the silent small-town street, a street he had never seen until yesterday. Still no sign of Dick," Capote wrote. Brooks uses a visual link to draw victim and killer together, showing Herbert Clutter (John McLiam) performing his morning shave. As Clutter leans into the sink to rinse the remaining shaving cream from his face, the face that rises up and looks in the mirror sees Perry Smith, excising his excess whiskers as well.

The biggest difference between the book and the movie came with Brooks' introduction of a Truman Capote surrogate, a magazine reporter named Jensen, who travels to Holcomb to cover the case. Jensen isn't played in a way similar to the extremely distinctive Capote — such as the way that won Philip Seymour Hoffman an Oscar for Capote, that Toby Jones played even better in Infamous or that Tru himself played best of all as Lionel Twain in Neil Simon's 1976 mystery spoof Murder By Death. Brooks wrote the Jensen character straight (no pun intended) and conventionally, even giving him a narrator's function at times. He doesn't precisely follow how Capote researched the story though because Capote didn't arrive in Kansas until after Smith and Hickok had been apprehended. In the movie, Jensen arrives almost from the beginning of the investigation. For the role of Jensen, Brooks cast another veteran character actor — Paul Stewart, whose first credited screen role was the butler Raymond in Citizen Kane. His 42-year film and television career ended in 1983 with an episode of Remington Steele and he died three years later, a month shy of his 88th birthday. After starting with Kane, a few of Stewart's eclectic highlights included Champion, Brooks' Deadline-U.S.A., The Bad and the Beautiful, Kiss Me Deadly, Hell on Frisco Bay, King Creole, Opening Night, Revenge of the Pink Panther,

S.O.B. and appearances on nearly every episodic police or detective show between the 1950s and the 1970s, including The Mod Squad. The Jensen character arrives around the same time that the Kansas Bureau of Investigation joins the case led by John Forsythe as Alvin Dewey, what may be Forsythe's best performance. Brooks gives him a lot of speeches — and some come off as less pristine than others, but Forsythe succeeds at selling most of them. Forsythe gets so identified with Dynasty or as a voice on Charlie's Angels that I think people forget that he really act when the material was there for him as it was here or in the short-lived and underrated Norman Lear sitcom The Powers That Be and having fun with Hitchcock in The Trouble With Harry (though no one could help Topaz much). He also was a replacement performer of one of the major roles in Arthur Miller's All My Sons on Broadway. Granted, didn't see him, but he had to show some chops to land that one. Of his filmed work though, I think In Cold Blood stands as the best. Sure, this speech reads as overwrought, but he pulled it off as he delivered it to Jensen. "Someday, someone will have to explain the motive of a newspaper to me. First, you scream, 'Find the bastards.' Till we do find 'em, you want to get us fired. When we find 'em, you accuse us of brutality. Before we go

S.O.B. and appearances on nearly every episodic police or detective show between the 1950s and the 1970s, including The Mod Squad. The Jensen character arrives around the same time that the Kansas Bureau of Investigation joins the case led by John Forsythe as Alvin Dewey, what may be Forsythe's best performance. Brooks gives him a lot of speeches — and some come off as less pristine than others, but Forsythe succeeds at selling most of them. Forsythe gets so identified with Dynasty or as a voice on Charlie's Angels that I think people forget that he really act when the material was there for him as it was here or in the short-lived and underrated Norman Lear sitcom The Powers That Be and having fun with Hitchcock in The Trouble With Harry (though no one could help Topaz much). He also was a replacement performer of one of the major roles in Arthur Miller's All My Sons on Broadway. Granted, didn't see him, but he had to show some chops to land that one. Of his filmed work though, I think In Cold Blood stands as the best. Sure, this speech reads as overwrought, but he pulled it off as he delivered it to Jensen. "Someday, someone will have to explain the motive of a newspaper to me. First, you scream, 'Find the bastards.' Till we do find 'em, you want to get us fired. When we find 'em, you accuse us of brutality. Before we go into court, you give them a trial in the newspaper, When we finally get a conviction, you want to save 'em by proving they were really crazy in the first place. All of which adds up to one thing — you've got the killers," Dewey tells Jensen as he's taking down to the basement of the Clutter house. Dewey also serves as Mr. Exposition, explaining why these two numbskulls just out of prison would decide to go to this one particular farmhouse and rob this family, making sure to "leave no witnesses," even though Dick and Perry only gain $40 from the crime. A fellow investigator asks Dewey if Clutter might have been rich and Alvin sort of laughs knowingly. "Ahh — the old Kansas myth. Every farmer with a big spread is supposed to have a secret black box with lots of money in it." It isn't until the ending that you realize the Brooks gave Dewey some of that dialogue because he's supposed to symbolize the parts of the system that disgust him. Brooks ardently opposed capital punishment and he made no secret that he wanted the ending to make clear that it was murder. At Smith's hanging, another reporter asks Dewey about how much the executioner makes. "Three hundred dollars a man," Dewey answers. "Who does he work for? Does he have a name?" the reporter follows up and then poor John Forsythe has to deliver the clunkiest line of dialogue in the entire film. "Yes. We the people." Earlier, it had been the topic of discussion between Jensen and an imprisoned Hickock.

into court, you give them a trial in the newspaper, When we finally get a conviction, you want to save 'em by proving they were really crazy in the first place. All of which adds up to one thing — you've got the killers," Dewey tells Jensen as he's taking down to the basement of the Clutter house. Dewey also serves as Mr. Exposition, explaining why these two numbskulls just out of prison would decide to go to this one particular farmhouse and rob this family, making sure to "leave no witnesses," even though Dick and Perry only gain $40 from the crime. A fellow investigator asks Dewey if Clutter might have been rich and Alvin sort of laughs knowingly. "Ahh — the old Kansas myth. Every farmer with a big spread is supposed to have a secret black box with lots of money in it." It isn't until the ending that you realize the Brooks gave Dewey some of that dialogue because he's supposed to symbolize the parts of the system that disgust him. Brooks ardently opposed capital punishment and he made no secret that he wanted the ending to make clear that it was murder. At Smith's hanging, another reporter asks Dewey about how much the executioner makes. "Three hundred dollars a man," Dewey answers. "Who does he work for? Does he have a name?" the reporter follows up and then poor John Forsythe has to deliver the clunkiest line of dialogue in the entire film. "Yes. We the people." Earlier, it had been the topic of discussion between Jensen and an imprisoned Hickock.DICK: Perry's the only one talking against capital punishment.

JENSEN: Don't tell me you're for it.

DICK: Hell, hangin' only getting revenge. What's wrong with revenge? I've been revenging myself all my life.

Part of the film's brilliance stems from the way Brooks structures the scenes detailing the crime itself. Toward the beginning of the movie, he presents what probably remains the greatest sequence of his directing career without actually showing the murder. Then, as the film winds down, he shows us what we didn't see and it's horrifying. Through a window of the farmhouse, we can see Nancy kneeling beside her bed saying her prayers. At that moment, it isn't made clear who could be seeing that — are Dick and Perry outside her window or are we simply the voyeurs right then? A split second later we spot Dick and Perry still sitting in the car beneath the cover of night. I guess it was us. The discordant sound of a doorbell suddenly fills the soundtrack and the viewer realizes he or she has moved inside the Clutter house — and sunlight shines through the windows. The camera tracks slowly around the furniture of the living room as it makes its way toward the front door. A woman and some other people open the door calling out for the Clutters. We faintly hear church bells tolling and the visitors wear their Sunday best. The woman continues to call out the Clutters by their first names as she ascends the stairs to the second floor. The film cuts quickly to the house's

exterior just as we hear the woman let out a horrified scream. Coming on the heels of The Professionals, it's as if somehow Brooks transformed himself from a competent director and damn good writer into a master of both. I don't know if the fact he had Conrad Hall working as his d.p. on both films made any sort of difference or if that proved to be just fortuitous, but that one-two punch sealed Brooks' artistic reputation forever beyond what respect he'd earned before. I've never been fortunate enough to see In Cold Blood on the big screen and allow Hall's haunting and beautiful mix of light and shadow to bathe me in its glow, but I did get the next best thing when in 1993 at the Inwood Theater in Dallas I saw Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy and Stuart Samuels' documentary Visions of Light, a film devoted to the art of cinematography and highlighting some of its greatest practitioners and their best moments. One of the highlighted scenes comes from In Cold Blood when Robert Blake as Perry gives an emotional monologue about his father in his prison cell while he looks out the window at the rain coming down. The reflection of the raindrops cast shadows on Blake's face that make it appear as if he's crying. The moment stuns in its beauty — even when you learn that as so many say, accidents ends up producing some of the best parts of film. Hall admitted it hadn't been planned but the humidity in the prison set had pumped up the window's perspiration so much (as well as everyone else's) that's how the magic happened. Thankfully, YouTube had that clip.

exterior just as we hear the woman let out a horrified scream. Coming on the heels of The Professionals, it's as if somehow Brooks transformed himself from a competent director and damn good writer into a master of both. I don't know if the fact he had Conrad Hall working as his d.p. on both films made any sort of difference or if that proved to be just fortuitous, but that one-two punch sealed Brooks' artistic reputation forever beyond what respect he'd earned before. I've never been fortunate enough to see In Cold Blood on the big screen and allow Hall's haunting and beautiful mix of light and shadow to bathe me in its glow, but I did get the next best thing when in 1993 at the Inwood Theater in Dallas I saw Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy and Stuart Samuels' documentary Visions of Light, a film devoted to the art of cinematography and highlighting some of its greatest practitioners and their best moments. One of the highlighted scenes comes from In Cold Blood when Robert Blake as Perry gives an emotional monologue about his father in his prison cell while he looks out the window at the rain coming down. The reflection of the raindrops cast shadows on Blake's face that make it appear as if he's crying. The moment stuns in its beauty — even when you learn that as so many say, accidents ends up producing some of the best parts of film. Hall admitted it hadn't been planned but the humidity in the prison set had pumped up the window's perspiration so much (as well as everyone else's) that's how the magic happened. Thankfully, YouTube had that clip.It must be said how good a performance Blake gives while at the same time acknowledging that it can't be viewed the way many of us assessed it originally. When a Naked Gun movie pops up and you see O.J. Simpson play an idiot and constantly take a beating, somehow that's OK. When you watch In Cold Blood again and see Blake give such a convincing and chilling performance as a mass murderer (especially when Forsythe's Alvin Dewey engages him in conversation during the ride to jail and Perry tells him, "I thought Mr. Clutter was a very nice gentleman. I thought it right till the moment I cut his throat."), you can't help but recall that a few decades later, the actor stood trial and received an acquittal for killing his wife. It doesn't stand out as groundbreaking now, when last night's Mad Men said shit twice, but in 1967, In Cold Blood became the first major release to utter the word bullshit. For the second year in a row, Brooks received Oscar nominations for directing and adapted screenplay and Hall got one for cinematography. Quincy Jones also picked up a nomination for original score, though Jones didn't receive one for his music for In the Heat of the Night. I don't understand how the nimrods at the Academy left it out of the top five for best picture. They nominated two films that deserved to be there: Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate. The film that won, a fine film but certainly expendable: In the Heat of the Night. A perceived prestige project of social significance that's overrated as hell: Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. The fifth nominee that would make no sense in any year: Doctor Dofuckinglittle. Basically, three out of the five films could have been tossed to make room for In Cold Blood. A few other more deserving 1967 titles: Cool Hand Luke, The Dirty Dozen, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, Accident, Wait Until Dark, Point Blank, The Jungle Book. The National Board of Review did honor Brooks' direction. Brooks also received his sixth Directors Guild nomination and his sixth Writers Guild nomination. With the exception of the WGA, Brooks would never be named for any of the top awards again. In Cold Blood marked his best, but from there things went downhill fast.

One of the most difficult films to find (I've never seen it) for that recent a film with a best actress nomination. Brooks wrote his first original screenplay since Deadline-U.S.A. as a vehicle for wife Jean Simmons. From descriptions I've read, Simmons plays Mary Wilson, who was raised on romantic notions of marriage from the movies, finds herself in a funk on her anniversary and flies to the Bahamas on a whim, running into a free spirit (Shirley Jones) while there.

I missed this one as well. From TCM's web site; "In Hamburg, Germany, American Joe Collins (Warren Beatty) is considered by bank manager Kessel (Gert Fröbe) to be the most honest, hard-working bank security expert in the world. Unknown to Kessel, Joe has been devising a plan with his girlfriend, American expatriate prostitute Dawn Divine (Goldie Hawn), to take the contents from bank safe-deposit boxes owned by several criminals and place them into one owned by Dawn. Roger Ebert gave it three stars in his original review.

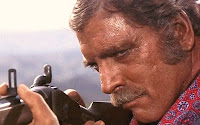

I wanted to see this one, but just ran out of time. Here's what qualifies as TCM's full synopsis: A former roughrider (Gene Hackman) matches wits with a lovely but shady lady-in-distress (Candice Bergen), as a drifting ex-cowboy (James Coburn) and a young, reckless cowboy (Jan-Michael Vincent) join in on a 700 mile journey. Ebert gave it three and a half stars in his original review.

I've actually seen this one. In fact, as we near the end of Brooks' career, I've watched two of the last three movies. As an unrelated sidenote, this year also marked the end of Brooks' 17-year marriage to Jean Simmons. If by chance you aren't familiar with this movie, think of it as sort of the Shame of the 1970s — and I don't mean the Ingmar Bergman movie. Diane Keaton stars as a teacher of deaf students whose affair with her college professor ends badly. She reacts as anyone would to a breakup — she starts cruising New York bars and picking up strangers for one-night stands while also developing a taste for drugs. The film definitely didn't belong in the genre of liberated women films of the 1970s as Keaton's character will pay. I saw this when I was a young man and I found it distasteful then, though it did have more sensible plotting than last year's Shame. Brooks directed his last performer to an Oscar nomination with Tuesday Weld getting a supporting actress nod. Keaton won the best actress Oscar for 1977 — but for Annie Hall. Brooks adapted a novel by Judith Rossen that was loosely based on a real incident, but most reviews by people who had read the novel seemed to indicate that Brooks changed key elements. Then, that matches the speech Brooks gave the movie's cast and crew on the first day of shooting, according to Douglass K. Daniel's Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks. "I'm sure that all of you have your own ideas about what kind of contributions you can make to this film, what you can do to improve it or make it better. Keep it to yourself. It's my fucking movie and I'm going to make it my way!" Daniel wrote. Goodbar also featured Richard Gere in one of his earliest roles. This clip plays off the tension of whether fun and games are at hands or something more dangerous.

Brooks referred to this film as "the biggest disaster" of his career. Later, he amended it slightly, blaming TV for purposely not coverage the film because the movie criticized "checkbook journalism." Having watched Wrong Is Right for the first time recently, this compels me to ask, "It did?" Sean Connery stars as a globetrotting reporting for what appears to be a CNN-like news station. The opening sequence contains some amusing moments, (including a young Jennifer Jason Leigh, nearly 30 years after her dad Vic Morrow played the worst punk in Brooks; Blackboard Jungle) but what could be cutting-edge satire of a media form just being born transforms into a scattershot satire involving fictional oil-rich African countries, the CIA, a presidential race and arms dealers trading suitcase nukes, Based on a novel, I hope that it had a plot, but Wrong Is Right just ends up being one of those strange satires like The Men Who Stared at Goats where once it ends you still don't know what the hell happened. This clip shows the opening sequence. Nothing after it deserves your attention.

I've got good news and bad news when it comes to Richard Brooks' final film. The good news: it brought him awards consideration again. The bad news: It was at the Razzies where it earned nominations for worst picture, worst director, worst screenplay and worst musical score. I'm not sure whether or not it relieved him that the film lost in all four categories, with Rambo: First Blood Part II taking worst picture, director and screenplay and Rocky IV winning worst score dishonors. I have not seen Fever Pitch which TCM hasn't even given a synopsis, but I know enough to tell you that Ryan O'Neal plays an investigator reporter doing a story on compulsive gambling who discovers he suffers from the problem. The subject of the movie came up on my Facebook page and Richard Brody, critic at The New Yorker, commented, "I saw Fever Pitch when it came out and loved every overheated second. Haven't seen it since then. Seeing The Connection has brought it back: no detached observer but a participant almost instantly in over his head." At the time of its release, it became one of the rare films that Ebert gave zero stars.

Following Fever Pitch, Brooks toyed with the idea of writing a screenplay about the blacklist, basing it around an incident in 1950 when fights broke out at the Directors Guild over the loyalty oath, but he didn't get around to it. The man who could be quite a bully on the set, had quite a bit of bitterness toward the industry by now as he showed in the second half of that 1985 interview.

Richard Brooks died of congestive heart failure on March 11, 1992, at 79. He did have close friends, but most of them had died themselves by then. The stepdaughter he basically raised as his own when he married Jean Simmons, Tracy Granger, made certain, his tombstone bore the only appropriate epitaph for the man.

Tweet

Labels: Arthur Miller, blacklist, Books, Capote, Connery, Diane Keaton, Ebert, Hackman, Hitchcock, J.J. Leigh, James Coburn, Jean Simmons, Jewison, Mailer, N. Lear, Neil Simon, P.S. Hoffman, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, March 29, 2012

Just when you thought you were out…

"If a team of assassins planned to ambush their target at a tollbooth, would it really be deemed necessary that the killers

wear their finest suits and fedoras while hiding before they perform the task? Did murder in the 1940s

require a dress code?" — Edward Copeland

By Edward Copeland

Some movies you love so much, have seen so many times in whole or in part, that when you stop to watch the film with a purpose (such as writing this post as well as the two previous ones, "America's first family" and "Merging art and commerce," to mark the 40th anniversary of The Godfather), you discover things you never noticed before and ideas occur to you for the first time. I still love The Godfather, but haven't watched it this closely in a long time — probably since viewing it in that Midtown Manhattan theater in 1997. When I saw it then, Goodfellas already existed in my life, but the sheer size of Coppola's images filtered through Gordon Willis' magnificent cinematography overwhelmed me so Martin Scorsese's masterpiece, albeit the greater film, didn't intrude on my thoughts then. This time though, I watched The Godfather on DVD on my TV — twice really, once for the movie, once for Coppola's commentary. This screening of rapt attention not only took place semi-horizontally at home, it also marked my first time observing The Godfather closely and in its entirety since The Sopranos entered the world. Because I have a lot to say, this will be a two-part post unlike the first two, which could stand alone. I plan, theoretically, for this final post to flow as a single piece even though I've divided it in half. To be a tease, I'm saving my new observations until the last section of this piece.

This reunion with the Corleones didn't change one aspect that amazed me the first time I viewed the film in a single, uncut setting: its miraculous pacing. Only a few minutes shy of three hours, The Godfather holds its length incredibly well. It never lags and you falsely sense that you've just settled in to the tale when, before you know it, the end credits roll. Coppola and his editing team of William

Reynolds and Peter Zinner accomplish this without making the movie seem rushed either. While I knew the film incredibly well before I watched it again, the obvious never stood out until I heard what Coppola said on the commentary that I quoted in the first Godfather-related post, "America's first family," when he talked about seeing The French Connection during editing and thinking, "Compared to that, The Godfather is going to be this dark, boring, long movie with a lot of guys sitting around in chairs talking." On the commentary, Coppola follows that with the quote I put at the top of this post. Of course, the director's stress coughed up the adjective boring, but the film indeed does contain many scenes involving men sitting around talking. When you think about The Godfather, what usually springs to mind involves the masterfully choreographed sequences of violence such as the ending baptism montage or other memorable scenes such as the opening "I believe in America" monologue by the undertaker Bonsasera (Salvatore Corsitto). Those scenes with men talking play perfectly well, but you don't think about it. Not when the film containz scenes such as James Caan's Sonny being assassinated at the tollbooth, which Coppola freely acknowledges as his homage to Arthur Penn's finale in Bonnie and Clyde. "Like my dad always said, 'Steal from the best,'" Coppola says.

Reynolds and Peter Zinner accomplish this without making the movie seem rushed either. While I knew the film incredibly well before I watched it again, the obvious never stood out until I heard what Coppola said on the commentary that I quoted in the first Godfather-related post, "America's first family," when he talked about seeing The French Connection during editing and thinking, "Compared to that, The Godfather is going to be this dark, boring, long movie with a lot of guys sitting around in chairs talking." On the commentary, Coppola follows that with the quote I put at the top of this post. Of course, the director's stress coughed up the adjective boring, but the film indeed does contain many scenes involving men sitting around talking. When you think about The Godfather, what usually springs to mind involves the masterfully choreographed sequences of violence such as the ending baptism montage or other memorable scenes such as the opening "I believe in America" monologue by the undertaker Bonsasera (Salvatore Corsitto). Those scenes with men talking play perfectly well, but you don't think about it. Not when the film containz scenes such as James Caan's Sonny being assassinated at the tollbooth, which Coppola freely acknowledges as his homage to Arthur Penn's finale in Bonnie and Clyde. "Like my dad always said, 'Steal from the best,'" Coppola says. The reason all those "talking scenes" work corresponds with the reason all those stylized scenes of violence work: great dialogue. Coppola didn't invent this. From the beginning of the torch Hollywood (and moviegoers) carried for gangsters and the mob, the genre's best examples always brought with them some of the most memorable line in movie history stretching back almost to the beginning of film. Literally, the list extends too long to name all the precursors. Of course, as the years went by, the country allowed more freedom of content in its movies. The Godfather debuted early in the process of those changes, becoming the first gangster film to truly benefit. As you'd expect, the prudes whined about moral decay then — just as many do now. (Those who yell loudest about losing their freedom inevitably also want to take it away from anyone who doesn't believe as they do.) Coppola addresses the issue of violence on the DVD. "The thing about violence in a film like this is you have to try to make every moment be in some way eccentric or have some unusual or memorable aspect so it's not just a bludgeoning or just violence but…there is some sort of context that singles it out," Coppola says. Wwile the big names get the lion's share of praise (deservedly) for their acting in The Godfather, not enough gets said about those in the

smaller roles because on top of its other positive attributes, The Godfather, despite Coppola's fights with Paramount, turned out to be an exceptionally well-cast movie. Richard Conte not only performs well as the oily and duplicitous rival boss Barzini, his presence provides a crucial link to the history of the genre, as did several other actors, through films such as Joseph L. Mankiewicz's House of Strangers, The Brothers Rico and Jules Dassin's great Thieves' Highway, which includes a memorable truck crash whose shot of rolling apples echoes the strewn oranges when Marlon Brando's Don Vito gets shot in The Godfather. Another link to past noirs come through Sterling Hayden's turn as the crooked cop Capt. McCluskey after roles in classics such as John Huston's The Asphalt Jungle and Stanley Kubrick's The Killing. Leaving his mark, sadly an all too brief one, was Al

smaller roles because on top of its other positive attributes, The Godfather, despite Coppola's fights with Paramount, turned out to be an exceptionally well-cast movie. Richard Conte not only performs well as the oily and duplicitous rival boss Barzini, his presence provides a crucial link to the history of the genre, as did several other actors, through films such as Joseph L. Mankiewicz's House of Strangers, The Brothers Rico and Jules Dassin's great Thieves' Highway, which includes a memorable truck crash whose shot of rolling apples echoes the strewn oranges when Marlon Brando's Don Vito gets shot in The Godfather. Another link to past noirs come through Sterling Hayden's turn as the crooked cop Capt. McCluskey after roles in classics such as John Huston's The Asphalt Jungle and Stanley Kubrick's The Killing. Leaving his mark, sadly an all too brief one, was Al Lettieri as Sollozzo, the Sicilian who wanted to bring narcotics into the city. Lettieri's acting success came late, appearing first on TV in 1957 at 29 but not making a movie until 1965. 1972 truly turned out to be his breakout year, appearing not only in The Godfather but in Sam Peckinpah's The Getaway. He died of a heart attack three years later at 47. One final connection, in a way, to noirs and gangsters of old came in the brief but fun performance of John Marley as movie studio President Jack Woltz with the unfortunate horse. Marley worked since the 1940s, mostly on

Lettieri as Sollozzo, the Sicilian who wanted to bring narcotics into the city. Lettieri's acting success came late, appearing first on TV in 1957 at 29 but not making a movie until 1965. 1972 truly turned out to be his breakout year, appearing not only in The Godfather but in Sam Peckinpah's The Getaway. He died of a heart attack three years later at 47. One final connection, in a way, to noirs and gangsters of old came in the brief but fun performance of John Marley as movie studio President Jack Woltz with the unfortunate horse. Marley worked since the 1940s, mostly on television, but included uncredited work in Kiss of Death and The Naked City and a small credited role in 1951's The Mob. Still, Marley remained one of those familiar faces that no one could name. It wasn't until the 1960s that he began to gain notice with parts in films such as Cat Ballou, a well-received starring role in John Cassavetes' Faces and a 1970 supporting actor nomination as Ali MacGraw's father in Love Story. Woltz's role didn't take up much screentime, but Marley made the most of it, paired mostly with the sublime Robert Duvall as Tom Hagen. The dinner scene between the two men delights every time. Coppola says that Duvall usually only needed a couple of takes to nail a scene, but I don't know how he couldn't crack up since the meal consists mostly of Marley's monologue about why he

television, but included uncredited work in Kiss of Death and The Naked City and a small credited role in 1951's The Mob. Still, Marley remained one of those familiar faces that no one could name. It wasn't until the 1960s that he began to gain notice with parts in films such as Cat Ballou, a well-received starring role in John Cassavetes' Faces and a 1970 supporting actor nomination as Ali MacGraw's father in Love Story. Woltz's role didn't take up much screentime, but Marley made the most of it, paired mostly with the sublime Robert Duvall as Tom Hagen. The dinner scene between the two men delights every time. Coppola says that Duvall usually only needed a couple of takes to nail a scene, but I don't know how he couldn't crack up since the meal consists mostly of Marley's monologue about why he hates Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) and wants to run him out of the business How Duvall sat there and ate without cracking up constantly I can't fathom. His spite stems because Fontane stole a girl that Woltz had from him, so that's why the studio chief seems determined not to give the singer the part in the movie he desires. "She was the greatest piece of ass I ever had — and I've had 'en all over the world," Woltz yells at Tom. This leads to the famous scene of Woltz waking up the next morning to find the head of his prized $400,000 thoroughbred in his bed, That wasn't a fake head either. Part of the crew went to a dog food company and looked over the horses they planned to kill eventually to turn into Fido's fixings. They selected the horse they liked and had the company save the head in dry ice and send it to them when they slaughtered the animal. Needless to say, many people went ballistic, Coppola said. He always thought it was fascinating how upset people got that they used the head of an already dead horse but the film's many human killings didn't bug many. As for Marley, years later he appeared on SCTV Network when they did their spoof of The Godfather with Joe Flaherty's station owner Guy Caballero as the title character, only Marley played Leonard Bernstein.

hates Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) and wants to run him out of the business How Duvall sat there and ate without cracking up constantly I can't fathom. His spite stems because Fontane stole a girl that Woltz had from him, so that's why the studio chief seems determined not to give the singer the part in the movie he desires. "She was the greatest piece of ass I ever had — and I've had 'en all over the world," Woltz yells at Tom. This leads to the famous scene of Woltz waking up the next morning to find the head of his prized $400,000 thoroughbred in his bed, That wasn't a fake head either. Part of the crew went to a dog food company and looked over the horses they planned to kill eventually to turn into Fido's fixings. They selected the horse they liked and had the company save the head in dry ice and send it to them when they slaughtered the animal. Needless to say, many people went ballistic, Coppola said. He always thought it was fascinating how upset people got that they used the head of an already dead horse but the film's many human killings didn't bug many. As for Marley, years later he appeared on SCTV Network when they did their spoof of The Godfather with Joe Flaherty's station owner Guy Caballero as the title character, only Marley played Leonard Bernstein.

Of the larger supporting roles in The Godfather, the actor and character I come away admiring and enjoying more each time I see the film in whole or in part continues to be Richard Castellano as Pete Clemenza, one of Don Corleone's capos and best killers. He also happens to be the funniest character in the movie. If any of the creations in The Godfather universe reminds me of someone who could turn up working on Tony Soprano's crew, Clemenza would be the one. Castellano gets so many classic bits, whether he's teasing Michael (Al Pacino) about not being able to tell Kay (Diane Keaton) he loves her on the phone in the kitchen full of Corleone soldiers. "Mikey, why don't you tell that nice girl you love her? I love you with all-a my heart, if I don't see-a you again soon, I'm-a gonna die," Clemenza needles him with a mock girl's voice while he makes a huge pot of "gravy." Among Clemenza's other duties, he teaches well. Not only does he try to pass on the recipe to Michael, he's the one who instructs him how to pull off the hit on Sollozzo and McCluskey. Castellano worked wonders grabbing a laugh before or after whacking someone. When Carlo (Gianni Russo), the no-good husband of Corleone sister Connie (Talia Shire), gets in a car, believing Michael when he says that he's only exiling him to Vegas and kicking him out of the family business as punishment for

setting up Sonny, Clemenza sounds perfectly friendly as he greets him with, "Hello Carlo" from the back seat before throttling him to death. According to Coppola, Castellano also improvised his most famous line (and one of the most repeated from the film as well). After a brief scene where Clemenza leaves his house to head to work, his wife (Adelle Sheridan) yells to him to remember to pick up cannolis. The top item on Clemenza's work schedule that day, by Sonny's orders, involvee killing Paulie (John Martino), the don's usual driver/bodyguard who conveniently was out ill the day before when Vito was ambushed. As Paulie drives Clemenza and Rocco (Tom Rosqui), one of

setting up Sonny, Clemenza sounds perfectly friendly as he greets him with, "Hello Carlo" from the back seat before throttling him to death. According to Coppola, Castellano also improvised his most famous line (and one of the most repeated from the film as well). After a brief scene where Clemenza leaves his house to head to work, his wife (Adelle Sheridan) yells to him to remember to pick up cannolis. The top item on Clemenza's work schedule that day, by Sonny's orders, involvee killing Paulie (John Martino), the don's usual driver/bodyguard who conveniently was out ill the day before when Vito was ambushed. As Paulie drives Clemenza and Rocco (Tom Rosqui), one of Clemenza's crew, Clemenza asks Paulie to pull over so he can take a piss. As Clemenza gets out of the car, Rocco kills Paulie. Clemenza returns and utters those immortal words that Castellano improvised, "Leave the gun. Take the cannoli." Later, in that kitchen scene where Clemenza cooks and ribs Michael, Sonny comes in and asks him simply, "How's Paulie?" "Oh, Paulie…won't see him no more," Clemenza states matter-of-factly, never pausing in his stirring of the sauce. One thing I noticed this time that slipped by me before is that Clemenza actually supplied me with the origin of the phrase "going to the mattresses." It's so obvious in meaning I don't know how it escaped me, especially since Tony and his men did exactly that in the penultimate Sopranos episode. In the Godfather sequel, Bruno Kirby played the young Clemenza, but Castellano's presence was sorely missed. They couldn't reach a deal on a contract. In a rarity, the issue had nothing to do with pay. Castellano insisted that a friend of his had to be hired to write all his dialogue personally for The Godfather Part II. That request proved way too easy for Coppola to refuse and that's how Michael V. Gazzo's character of Frank Pentangeli got created for Part II, earning Gazzo a supporting actor Oscar nomination. Castellano received a supporting actor nomination, but not for The Godfather. His came for the 1970 comedy Lovers and Other Strangers. The actor died in 1988.

Clemenza's crew, Clemenza asks Paulie to pull over so he can take a piss. As Clemenza gets out of the car, Rocco kills Paulie. Clemenza returns and utters those immortal words that Castellano improvised, "Leave the gun. Take the cannoli." Later, in that kitchen scene where Clemenza cooks and ribs Michael, Sonny comes in and asks him simply, "How's Paulie?" "Oh, Paulie…won't see him no more," Clemenza states matter-of-factly, never pausing in his stirring of the sauce. One thing I noticed this time that slipped by me before is that Clemenza actually supplied me with the origin of the phrase "going to the mattresses." It's so obvious in meaning I don't know how it escaped me, especially since Tony and his men did exactly that in the penultimate Sopranos episode. In the Godfather sequel, Bruno Kirby played the young Clemenza, but Castellano's presence was sorely missed. They couldn't reach a deal on a contract. In a rarity, the issue had nothing to do with pay. Castellano insisted that a friend of his had to be hired to write all his dialogue personally for The Godfather Part II. That request proved way too easy for Coppola to refuse and that's how Michael V. Gazzo's character of Frank Pentangeli got created for Part II, earning Gazzo a supporting actor Oscar nomination. Castellano received a supporting actor nomination, but not for The Godfather. His came for the 1970 comedy Lovers and Other Strangers. The actor died in 1988.

Another good supporting performance brings with it a great story. As I mentioned before, throughout his DVD commentary Coppola offers advice to new directors. One tip he gives repeatedly, actually he suggests it for directors at all levels of experience: Always hold at least a day or two of open auditions. He did this on The Godfather and filled several roles this way, but his best find (according to Coppola and I agree) turned out to be Abe Vigoda as Sal Tessio, Corleone's other main capo. Vigoda turned in a great performance, especially at the end when it's figured out that Tessio betrayed the Corleones and he knows he's being taken off to his death and makes a quiet plea to Duvall's Hagen to get him out of it "for old time's sake." Vigoda went on to become such a cult figure after playing Fish on Barney Miller and his short-lived spinoff Fish to getting much mileage out of premature reports of his death, especially through frequent appearances on Late Night With Conan O'Brien. Vigoda continues to work, having turned 91 in February and, according to the Inaccurate Movie Database, in pre-production for a feature comedy called The Mobster Movie co-starring Alice Cooper to be released next year. Vigoda's final moment in The Godfather should be a lesson to all directors to hold at least a day or two of open auditions because "you never know who is out there," Coppola said.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Arthur Penn, Brando, Caan, Cassavetes, Coppola, Dassin, Diane Keaton, Duvall, Huston, Kubrick, Mankiewicz, Movie Tributes, Pacino, Peckinpah, Scorsese, The Sopranos

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

…I pull you back in

By Edward Copeland

Among film buffs and people coming of mature moviegoing age in the 1970s, the name John Cazale engenders sadness in many of them. Featured in prominent roles in five features between 1972 and 1978, each received a nomination for the best picture Oscar and three of them won. However, by the time The Deer Hunter, the fifth of those films, was nominated along with Cazale's fiancée, Meryl Streep, getting her first supporting actress nomination for that film, Cazale had been dead for almost a year, having lost his battle with cancer on March 12, 1978, at the age of 42, leaving behind one helluva legacy in a short span of time. In addition to The Deer Hunter, Fredo in both parts of The Godfather; Stan, the assistant to eavesdropping expert Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), in another Francis Ford Coppola masterpiece, The Conversation and, Cazale's greatest performance, in my opinion, as Sal, bank robbing partner of Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino) in Sidney Lumet's magnificent Dog Day Afternoon. This piece concerns The Godfather, so let's talk Fredo.

Cazale does fine as Fredo in The Godfather but, truth be told, his time on screen doesn't add up to a lot. His role increases in Part II, but he actually has less to do in the 1972 film than many of the non-Corleones. Fredo though has acquired a legacy almost removed from the film itself. The name has become synonymous with a ne'er do, usually a ne'er do well brother. I imagine people who can't name John Cazale as the actor who portrayed Fredo recognize what someone means if they refer to someone as a Fredo. The Urban Dictionary includes multiple definitions such as the simple "family's black sheep" to having sex with two waitresses simultaneously as Moe Greene claimed he caught Fredo doing and Vince Vaughn's character reference in Swingers. The truth of the matter just happens to be that Fredo Corleone, the middle son, can't stop fucking up. It's sad, because you see in Cazale's portrayal that Fredo wants to be a good son, but he's messed up so many times that even he understands why his family can't rely on him. His big, heartbreaking scene comes when rival gangsters make their assassination attempt on his father and Fredo bobbles his own gun, unable to shoot back. He ends up sitting on the curb, next to his critically wounded dad, the gun dangling from his hand, weeping like a child.

You'd think that Talia Shire had the easiest path to landing her role as Corleone daughter Connie, given that her brother Francis was directing the film, but Coppola says he almost didn't consider her for the part because he thought his kid sister was "too beautiful." Connie isn't much more than a plot point in The Godfather — a Corleone daughter to get wed, beaten and, finally, to lash out at her brother for killing her no-good husband. Shire and Connie don't get to grow into interesting characters until the sequels, for certain Part II and, reportedly, a re-edited Part III on DVD and Blu-ray that drastically improves that misfire, including her character's motivations. Walter Murch is said to have led the restoration and re-cutting of Part III, which was rushed in 1990 in order to qualify for the Oscars. Reported rumors that the new cut of Part III replaces Sofia Coppola with Andy Serkis have not been verified. The other major female role in The Godfather got more to do but, like Connie, developed even further in Part II. This was Diane Keaton's second feature film after Lovers and Other Strangers co-starring Richard Castellano (Clemenza). While Keaton proved often that she's adept at drama, she's always better in comedies as Woody Allen utilized with great success.

The don's oldest son and his adopted one represent fire and ice, and James Caan and Robert Duvall excel at those elemental levels as Sonny Corleone and Tom Hagen. One moment I noticed this time that I'd never observed before occurs when Sonny, after finding Connie beaten and bruised by Carlo, beats the hell out of his brother-in-law in the street. When Carlo grabs hold of a railing, Sonny actually bites into

Carlo's hands to make him let go (in front of a Thomas Dewey campaign poster no less). Going back to Coppola's concern about guys sitting around talking, you don't get tired of these two doing that, especially in scenes such as debating what actions to take following the attempt on their father's life. When Michael comes home with a swollen jaw courtesy of the crooked police captain, it sets Sonny off again, ready to go to war against Sollozzo. Tom, functioning as the levelheaded consigliere, tries to explain to his adopted brother that even the man upstairs recovering from his bullet wounds would understand that it wasn't personal.

Carlo's hands to make him let go (in front of a Thomas Dewey campaign poster no less). Going back to Coppola's concern about guys sitting around talking, you don't get tired of these two doing that, especially in scenes such as debating what actions to take following the attempt on their father's life. When Michael comes home with a swollen jaw courtesy of the crooked police captain, it sets Sonny off again, ready to go to war against Sollozzo. Tom, functioning as the levelheaded consigliere, tries to explain to his adopted brother that even the man upstairs recovering from his bullet wounds would understand that it wasn't personal.TOM: Your father wouldn't want to hear this, Sonny. This is business, not personal.

SONNY: They shoot my father and it's business, my ass!

TOM: Even shooting your father was business not personal, Sonny!

Caan dances through the movie, all energy, sometimes comic, sometimes violent, sometimes sexual. When brother Michael (Al Pacino) decides he doesn't want to be the straight-arrow civilian anymore, Sonny laughs at his kid brother, even using Hagen's words. "Hey,

whaddya gonna do, nice college boy, eh? Didn't want to get mixed up in the family business, huh? Now you wanna gun down a police captain. Why? Because he slapped ya in the face a little bit? Hah? What do you think this is the Army, where you shoot 'em a mile away? You've gotta get up close like this and — bada-BING! — you blow their brains all over your nice Ivy League suit. You're taking this very personal. Tom, this is business and this man is taking it very, very personal," Sonny teases. Of course, Duvall's path to success had been forming prior to The Godfather, but this did earn him his first Oscar nomination as supporting actor. Caan, Duvall and Pacino all earned supporting nominations, one of the rare times a single film grabbed three slots in an acting category. The Godfather Part II repeated the feat in the same category. It also had been achieved by On the Waterfront. The movie Tom Jones accomplished it in supporting actress and the 1935 Mutiny on the Bounty did it in best actor (out of four nominees), but this was prior to the creation of the supporting categories.

whaddya gonna do, nice college boy, eh? Didn't want to get mixed up in the family business, huh? Now you wanna gun down a police captain. Why? Because he slapped ya in the face a little bit? Hah? What do you think this is the Army, where you shoot 'em a mile away? You've gotta get up close like this and — bada-BING! — you blow their brains all over your nice Ivy League suit. You're taking this very personal. Tom, this is business and this man is taking it very, very personal," Sonny teases. Of course, Duvall's path to success had been forming prior to The Godfather, but this did earn him his first Oscar nomination as supporting actor. Caan, Duvall and Pacino all earned supporting nominations, one of the rare times a single film grabbed three slots in an acting category. The Godfather Part II repeated the feat in the same category. It also had been achieved by On the Waterfront. The movie Tom Jones accomplished it in supporting actress and the 1935 Mutiny on the Bounty did it in best actor (out of four nominees), but this was prior to the creation of the supporting categories.

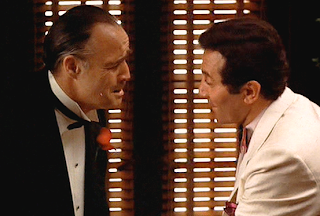

Which leaves us with the film's two most important characters who also happen to be its most important actors as well. One of the first practitioners of the Method who had set the world on fire and a brash newcomer with a new generation's take on the same style meeting together. The old master Marlon Brando, showing the world that he still had power, while the rising star Al Pacino makes his presence known loudly (back in the days when Pacino did this without being literally loud). Before watching the movie this time, I read someone commenting how as Michael shifts into Vito's role, Pacino subtly transforms physically. That swollen jaw from McCluskey's punch starts to resemble those cotton-stuffed jowls Brando gave Vito. When I did watch it, especially when you really pay attention to that great contribution from Robert Towne, it's as if Vito and Michael undergo a Persona-like transference. I believe the key moment of Michael's switch happens when he protects his father at the hospital, hiding his bed in the stairwell and

clutching his hand, whispering, "I'm with you now, pop." The don, who hasn't regained consciousness since the shooting, does then and gives his son the sweetest smile. It's a touching moment — if you forget the family business. Everyone debates whether Brando has the movie's lead role or if that title really belongs to Pacino. I always swear that I'm gonna add up minutes of screentime, but I can never do it because I get too involved. To me, it feels more or less as if it's an ensemble piece. Brando disappears for awhile after he's shot, but so does Pacino immediately after he flees the country. (It's worth pointing out that even the greatest films ever made have flaws. As I feel the Paris flashbacks in my beloved Casablanca come off as hokey, Michael's Sicily scenes and sudden marriage may be The Godfather's Achilles' heel.) What I know for certain is that both actors deliver great performances. You see very little of the Brando silliness that sometimes pop up with the most obvious example being when singer Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) seeks his help at the wedding at the don unmercifully mocks him as Fontane practically cries acting what he can do to get that movie part. Corleone shakes him vigorously and shouts, "You can act like a man!" He then slaps him and ridicules him further. "What's the matter with you? Is this what you've become, a Hollywood finocchio who cries like a woman?" Then the funny Brando comes out as he does a little girl voice, "'Oh, what do I do? What do I do?' What is that nonsense? Ridiculous!" You spot Tom Hagen laughing in the background, but part of me suspects that really was Duvall trying not to crack up. Other than that, Brando plays things remarkably straight and truthfully as when he calls in the favor the undertaker Bonasera owes him to clean up Sonny for his funeral. "Look how they massacred my boy," he cries.

clutching his hand, whispering, "I'm with you now, pop." The don, who hasn't regained consciousness since the shooting, does then and gives his son the sweetest smile. It's a touching moment — if you forget the family business. Everyone debates whether Brando has the movie's lead role or if that title really belongs to Pacino. I always swear that I'm gonna add up minutes of screentime, but I can never do it because I get too involved. To me, it feels more or less as if it's an ensemble piece. Brando disappears for awhile after he's shot, but so does Pacino immediately after he flees the country. (It's worth pointing out that even the greatest films ever made have flaws. As I feel the Paris flashbacks in my beloved Casablanca come off as hokey, Michael's Sicily scenes and sudden marriage may be The Godfather's Achilles' heel.) What I know for certain is that both actors deliver great performances. You see very little of the Brando silliness that sometimes pop up with the most obvious example being when singer Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) seeks his help at the wedding at the don unmercifully mocks him as Fontane practically cries acting what he can do to get that movie part. Corleone shakes him vigorously and shouts, "You can act like a man!" He then slaps him and ridicules him further. "What's the matter with you? Is this what you've become, a Hollywood finocchio who cries like a woman?" Then the funny Brando comes out as he does a little girl voice, "'Oh, what do I do? What do I do?' What is that nonsense? Ridiculous!" You spot Tom Hagen laughing in the background, but part of me suspects that really was Duvall trying not to crack up. Other than that, Brando plays things remarkably straight and truthfully as when he calls in the favor the undertaker Bonasera owes him to clean up Sonny for his funeral. "Look how they massacred my boy," he cries.Looking at the young Pacino engenders the same kind of sadness that recent appearances by Robert De Niro do — did their love of the craft give way totally to monetary concerns? Pacino actually hasn't been quite as bad as De Niro, but to see his Michael, when Pacino knew the word subtlety…sigh. My God — I didn't see it, but what in the hell was he doing playing himself opposite Adam Sandler in Jack and Jill? To Pacino's credit, at least I can believe he appears in that kind of shit so he can keep returning to the stage. Michael Corleone's arc allows viewers to see a master class in screen acting over the first two movies. You can accomplish this with the first film alone, watching as he slinks further into the darkness. Another thing I've always loved that I'm grateful I found a YouTube clip to use is the strut Michael develops once he's completed his turn and just watched Carlo ride off to his demise. What an evocative, physical symbol of a man's change.

At the beginning of this post (I apologize that happened so long ago) I promised that I would be discussing things new to me about The Godfather. That time has arrived. In case it's slipped your mind, what I began this piece by saying was that sometimes you know a movie so well that when you actually watch it closely and purposefully, you'll notice things or have ideas that haven't occurred to you before.

Don't get me wrong. The reason I've spent so much space talking about the acting, writing and directing after the setup before I got to the crux of this assessment was meant to reassure those out there that The Godfather remains one of my favorite films of all time before I described a shift in my outlook on it. Back in the previous posts, as I detailed all the chaos endured to get the film made, I mentioned briefly how Paramount pursued some of the top directors at that time but all turned the project down, citing a fear of glamorizing or glorifying the Mafia. That's a criticism that gets hurled at most mob-related entertainments. Some said that about Martin Scorsese's Goodfellas. Even larger numbers lodged that complaint against The Sopranos. Reflexively, I've always responded that those accusations were nothing but a load of crap — and they are when it comes to Goodfellas and The Sopranos, which don't try to hide the fact that these people steal, kill and basically don't contribute to a civil society. Watching The Godfather this time, a light suddenly illuminated its depiction of the Corleones as whitewashed, to say the least. It starts from the very first scene when the undertaker Bonasera asks the don to kill the men who attacked his daughter, but Vito refuses. When Bonasera leaves, Vito even says to Tom Hagen, "We're not murderers, no matter what he thinks." Except mobsters are murderers. That line only marks the first example of the film turning the criminal family into reputable heroes. These photos are just for contrast. At left, we have Corleone family soldier Luca Brasi (Lenny Montana) being strangled in an ambush set up by the "bad gangsters"

Sollozzo (Al Lettieri) and Bruno Tattaglia (Tony Giorgio). In the photo on the right, the star of The Sopranos, James Gandolfini as Tony, personally throttles Fabian Petrulio (Tony Ray Rossi), who used to be a gangster but became a "rat" when he testified for the feds and went into the Witness Protection Program. This took place in "College," the heralded fifth episode of the series. They wasted no time showing that Tony would commit a hands-on murder. Examine Goodfellas in comparison to The Godfather. Goodfellas came from Nicholas Pileggi's well-researched nonfiction book Wiseguys. While Mario Puzo's novel played the guessing game of "Who could this character be based on?", Puzo never asserted it to be anything but a fictionalized portrait and the film version watered down the Corleones even further. Coppola openly admits he wanted to use the story to be less about organized crime but a comment on American capitalism as well as being about a family in the generic sense. While corporate businessmen may not call their mistresses goomahs, they have them. You'd have to watch very closely to notice that a wife exists that Sonny cheats on (You never see a ring on his finger). They show him having a vigorous sex life, but certainly downplay that it's an adulterous one. We get a few brief shots of his spouse and one comment from his dad when Sonny comes into his father's office following a sexual encounter and his dad talks with Fontane. When Vito sees Sonny enter, he asks the singer but looks pointedly at his son, "Are you good to your family?" In Goodfellas, the girlfriends existed as part of the gangster lifestyle with, separate nights set aside for them at the Copacabana. By the era of The Sopranos, the wives know they exist and accept them somewhat as long as they keep the benefits of their lifestyle.

Sollozzo (Al Lettieri) and Bruno Tattaglia (Tony Giorgio). In the photo on the right, the star of The Sopranos, James Gandolfini as Tony, personally throttles Fabian Petrulio (Tony Ray Rossi), who used to be a gangster but became a "rat" when he testified for the feds and went into the Witness Protection Program. This took place in "College," the heralded fifth episode of the series. They wasted no time showing that Tony would commit a hands-on murder. Examine Goodfellas in comparison to The Godfather. Goodfellas came from Nicholas Pileggi's well-researched nonfiction book Wiseguys. While Mario Puzo's novel played the guessing game of "Who could this character be based on?", Puzo never asserted it to be anything but a fictionalized portrait and the film version watered down the Corleones even further. Coppola openly admits he wanted to use the story to be less about organized crime but a comment on American capitalism as well as being about a family in the generic sense. While corporate businessmen may not call their mistresses goomahs, they have them. You'd have to watch very closely to notice that a wife exists that Sonny cheats on (You never see a ring on his finger). They show him having a vigorous sex life, but certainly downplay that it's an adulterous one. We get a few brief shots of his spouse and one comment from his dad when Sonny comes into his father's office following a sexual encounter and his dad talks with Fontane. When Vito sees Sonny enter, he asks the singer but looks pointedly at his son, "Are you good to your family?" In Goodfellas, the girlfriends existed as part of the gangster lifestyle with, separate nights set aside for them at the Copacabana. By the era of The Sopranos, the wives know they exist and accept them somewhat as long as they keep the benefits of their lifestyle.I don't know how this could come as such a shock to me now, having seen The Godfather so many times over so many years other than my love for Goodfellas superseding it and subliminally planting seeds in my mind which The Sopranos watered, allowing the realization to blossom. The recent Blu-ray release The Godfather Coppola Restoration includes a special feature in which Sopranos creator David Chase says he intended his series to be about the first generation of gangsters actually influenced by Coppola's film. I'm sure that's true (the characters made lots of references to the trilogy), but their lives more closely resemble those of the real gangsters in Henry Hill's universe in Goodfellas than they do the Corleones, with their huge family compound. Even Paulie (Paul Sorvino), the boss in Goodfellas, lived a

more middle-class-looking lifestyle, at least in terms of appearance. The fictional Tony got to move into upper middle-class suburbs, but those who worked for him lived much more meagerly. Hell, when you compare them, the brief shot in The Godfather of the home where Clemenza lives looks much nicer than the Belleville, N.J. residence of Corrado Soprano (Dominic Chianese). While not a gangster, even Walter White (Bryan Cranston) lived in a much nicer house when his salary came solely from teaching chemistry than Uncle Junior's or most of Tony's crew's places did, but the cost-of-living in Albuquerque probably is a lot less expensive than New Jersey. What's more relevant than the living arrangements of the various fictional and nonfictional criminals comes from my recognition of the unwillingness to show the true nature of the Corleone family unlike Scorsese did with the criminals in Goodfellas, Chase showed with his characters on The Sopranos and Vince Gilligan does on Breaking Bad charting, as he's said often, "Mr. Chips turning into Scarface." In Goodfellas and the TV shows, you see the innocent who pay the price for their crimes. In The Godfather, we don't see a single instance of how the Corleones conduct their criminal enterprises. The Godfather board game that I mentioned having in the first post, "America's first family," explicitly references bookmaking, extortion, bootlegging, loan sharking and hijacking though those activities never cross the lips of the Corleones or anyone who works for them (though it's doubtful that by 1945, bootlegging draws much revenue for the New York-based family). Are we to presume the Corleones actually built the mansion with profits from selling Genco Olive Oil?

more middle-class-looking lifestyle, at least in terms of appearance. The fictional Tony got to move into upper middle-class suburbs, but those who worked for him lived much more meagerly. Hell, when you compare them, the brief shot in The Godfather of the home where Clemenza lives looks much nicer than the Belleville, N.J. residence of Corrado Soprano (Dominic Chianese). While not a gangster, even Walter White (Bryan Cranston) lived in a much nicer house when his salary came solely from teaching chemistry than Uncle Junior's or most of Tony's crew's places did, but the cost-of-living in Albuquerque probably is a lot less expensive than New Jersey. What's more relevant than the living arrangements of the various fictional and nonfictional criminals comes from my recognition of the unwillingness to show the true nature of the Corleone family unlike Scorsese did with the criminals in Goodfellas, Chase showed with his characters on The Sopranos and Vince Gilligan does on Breaking Bad charting, as he's said often, "Mr. Chips turning into Scarface." In Goodfellas and the TV shows, you see the innocent who pay the price for their crimes. In The Godfather, we don't see a single instance of how the Corleones conduct their criminal enterprises. The Godfather board game that I mentioned having in the first post, "America's first family," explicitly references bookmaking, extortion, bootlegging, loan sharking and hijacking though those activities never cross the lips of the Corleones or anyone who works for them (though it's doubtful that by 1945, bootlegging draws much revenue for the New York-based family). Are we to presume the Corleones actually built the mansion with profits from selling Genco Olive Oil?you got whacked. Everybody knew the rules. But sometimes, even if people didn't get out of line, they got whacked.

I mean, hits just became a habit for some of the guys. Guys would get into arguments over nothing and before you knew it,

one of them was dead. And they were shooting each other all the time. Shooting people was a normal thing. It was no big deal."

— Ray Liotta as Henry Hill in Goodfellas

Where The Godfather goes to the greatest length to make the Corleones "good gangsters" can be viewed by the people they do kill. Every single one of them has wronged them first and/or been shown as someone worthy of elimination. You never see any incident such as in Goodfellas where psycho Tommy (Joe Pesci) kills the waiter Spider (Michael Imperioli) because he told him to "go fuck himself" (since Spider justifiably nurses a grudge after Tommy shot him in the foot before for not serving him a drink fast enough). You don't see

anything like on The Sopranos where a waiter follows Paulie (Tony Sirico) and Christopher (Imperioli again) out to the parking lot to ask why he didn't get a tip and they smash him in the head, causing convulsions and then shoot him to finish him off. Don Vito plays the peacemaker, despite being nearly killed and losing a son. The movie perpetuates the myth that the American Mafia likes to perpetuate that they stayed hands off narcotics trafficking (even Paulie Cicero in Goodfellas, based on the real-life Paulie Vario, peddles that line though, like the fictional Corleone, it isn't so much a moral objection as a fear of losing friends in high positions). It sounds particularly ridiculous since Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky already had started dealing heroin in the 1920s, something being depicted in the TV series Boardwalk Empire which may be set prior to the time period of The Godfather but by far pays the most obvious homages to the movie. This sudden realization raises questions in my mind: Does it matter? Should it matter? If The Godfather glamorizes gangsters, does that mean I should consider it a lesser movie? My answer has to be no to all of the above. It doesn't change its artistry and I already loved Goodfellas more anyway (and it only glamorizes their food). How can I really penalize a fictional film for not being more truthful? In the wake of The Godfather, did organized crime grow and get a bunch of new recruits eager to join mob ranks? Hardly. It's just interesting that it took me this long to notice this, but the film hasn't changed, I have.