Monday, May 21, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part III

By Edward Copeland

It isn't often that a masterpiece of literature begets a masterpiece of cinema yet both retain distinct identities all their own, but that's the case with In Cold Blood, Truman Capote's "nonfiction novel" and Richard Brooks' stunning film adaptation of his book. Capote often gets credit for inventing the genre of adapting the techniques of a novelist to that of straight reporting, but earlier attempts existed — Capote's stood out because In Cold Blood 's excellence made everyone forget any other examples (at least until more than a decade later when Norman Mailer added his own brilliant take on the genre with The Executioner's Song). Brooks, with his job as a crime reporter in his past, on the surface appears to follow Capote's approach, but the director, forever the activist, skips the objectivity that Capote tried to evoke in his book. Brooks didn't want to minimize the horror of the crime that occurred at the Clutter farm in Holcomb, Kans., but he also wanted to humanize the killers, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. In a way, Brooks' film inspired the path for the two films made decades later telling the story of Capote's writing of the book and his getting to know the killers first-hand as they waited on Death Row. Even today, Brooks' 1967 film remains more powerful and better made than the two more recent tales. Undoubtedly, In Cold Blood remains Brooks' greatest film. If you got here before reading either Part I or Part II of this tribute, click on the respective links.

The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call "out there." Some seventy miles east of the Colorado border, the countryside, with its hard blue skies and desert-clear air, has an atmosphere that is rather more Far West than Middle West. The local accent is barbed with a prairie twang, a ranch-hand nasalness, and the men, many of them, wear narrow frontier trousers, Stetsons, and high-heeled boots with pointed toes. The land is flat, and the views are awesomely extensive; horses, herds of cattle, a white cluster of grain elevators rising as gracefully as Greek temples are visible long before a traveler reaches them.

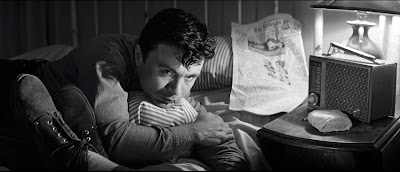

Capote begins his book with that paragraph in the first chapter titled The Last to See Them Alive. Brooks begins the film of In Cold Blood introducing us to The Last to See Them Alive in the forms of Robert Blake as newly paroled inmate Perry Smith and Scott Wilson as an acquaintance he met in prison who had been freed earlier, Dick Hickok. Brooks gives Blake — and the movie — a memorable entrance, especially thanks to his decision to go against the grain of the time and film in black-and-white Panavision. We see a bus driving down a two-lane highway, passing signs showing the distance to different Kansas towns, including the horrific Olathe. On the bus, a young female stumbles down the aisle to get a closer look at the pair of pointed-toe cowboy boots with buckles on its heels before creeping back. The shadowy man who wears the boots also has a guitar strung around his neck. A flame suddenly illuminates Robert Blake's face as he lights a cigarette and Quincy Jones' ominous yet jazzy score kicks in to start the credits. The sequence not only sets the tone for the film that follows, it also introduces us to the movie's most important participant — cinematographer Conrad L. Hall (though he didn't need to use the L. yet since his son, Conrad W. Hall, wasn't old enough to follow his dad into the business).

The movie spends its opening minutes introducing us to the soft-spoken Perry and getting him hooked up with Dick. Whereas Blake's Perry comes off as a puppy repeatedly kicked by his owner, Scott Wilson portrays Hickok as a cocky, livewire and a chatterbox — and Brooks gives him great lines, especially in the scenes where he and Blake drive around. "Ever seen a millionaire fry in the electric chair? Hell, no. There's two kinds of laws, one for the rich and one for the poor," Dick imparts as wisdom to Perry. When the two buy supplies for the planned robbery of the Clutter farm, Dick shoplifts some razorblades for no good reason, leading Perry to chastise him for taking such a risk for something so small. "That was stupid — stealin' a lousy pack of razor blades! To prove what?" Perry asks. Smiling, Dick replies, "It's the national pastime, baby, stealin' and cheatin'. If they ever count every cheatin' wife and tax chiseler, the whole country would be behind prison walls." Though in the two recent biographical films about Truman Capote's research into the case, it's strongly implied that Capote at least developed a crush on Smith and that Perry may have been gay. In Cold Blood never explicltly claims that Perry Smith was gay, but throughout the film Dick taunts him by

calling him "honey," "baby" or something along those lines. Hickock on the other hand chases every skirt he gets near and during the robbery/murder, Perry intervenes to stop Dick from raping the Clutters' 16-year-old daughter Nancy (Brenda Currin). Wilson made his first two feature films in 1967 and he landed roles in two of the biggest — this one and the eventual Oscar winner for best picture, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night. The jaws of younger readers should hit the floor when they see Wilson's great work here and it slowly dawns on them that playing Dick Hickok is a younger incarnation of Herschel on AMC's The Walking Dead. When Perry and Dick do get together, they meet at Dick's father's house where Dick tries to aid his old man, who's slowly losing his battle with terminal cancer. (Veteran character actor Jeff Corey, who co-starred in the Brooks-scripted 1947 classic Brute Force, plays the elder Hickock.) Contrasting Capote's take with Brooks' version fascinates in the ways the works reflect each other yet, like a mirror, many things appear on the opposite side. The book introduces its readers to the Clutter family first before Perry and Dick enter the story (by name anyway). Brooks' screenplay reverses the order, beginning with the killers then letting us meet the Kansas family. However, both aim to draw parallels between the victims and their eventual murderers. "That morning an apple and a glass of milk were enough for him; because

calling him "honey," "baby" or something along those lines. Hickock on the other hand chases every skirt he gets near and during the robbery/murder, Perry intervenes to stop Dick from raping the Clutters' 16-year-old daughter Nancy (Brenda Currin). Wilson made his first two feature films in 1967 and he landed roles in two of the biggest — this one and the eventual Oscar winner for best picture, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night. The jaws of younger readers should hit the floor when they see Wilson's great work here and it slowly dawns on them that playing Dick Hickok is a younger incarnation of Herschel on AMC's The Walking Dead. When Perry and Dick do get together, they meet at Dick's father's house where Dick tries to aid his old man, who's slowly losing his battle with terminal cancer. (Veteran character actor Jeff Corey, who co-starred in the Brooks-scripted 1947 classic Brute Force, plays the elder Hickock.) Contrasting Capote's take with Brooks' version fascinates in the ways the works reflect each other yet, like a mirror, many things appear on the opposite side. The book introduces its readers to the Clutter family first before Perry and Dick enter the story (by name anyway). Brooks' screenplay reverses the order, beginning with the killers then letting us meet the Kansas family. However, both aim to draw parallels between the victims and their eventual murderers. "That morning an apple and a glass of milk were enough for him; because he touched neither coffee or tea, he was accustomed to begin the day on a cold stomach. The truth was he opposed all stimulants, however gentle. He did not smoke, and of course he did not drink; indeed, he had never tasted spirits, and was inclined to avoid people who had — a circumstance that did not shrink his social circle as much as might be supposed, for the center of that circle was supplied by the members of Garden City's First Methodist Church, a congregation totaling seventeen hundred, most of whom were as abstemious as Mr. Clutter could desire," Capote described the Clutter patriarch. A few pages later in the first chapter, Perry Smith makes his entrance into Capote's book. "Like Mr. Clutter, the young man breakfasting in a cafe called the Little Jewel never drank coffee. He preferred root beer. Three aspirin, cold root beer, and a chain of Pall Mall cigarettes — that was his notion of a proper "chow-down." Sipping and smoking, he studied a map spread on the counter before him — a Phillips 66 map of Mexico — but it was difficult to concentrate, for he was expecting a friend, and the friend was late. He looked out a window at the silent small-town street, a street he had never seen until yesterday. Still no sign of Dick," Capote wrote. Brooks uses a visual link to draw victim and killer together, showing Herbert Clutter (John McLiam) performing his morning shave. As Clutter leans into the sink to rinse the remaining shaving cream from his face, the face that rises up and looks in the mirror sees Perry Smith, excising his excess whiskers as well.

he touched neither coffee or tea, he was accustomed to begin the day on a cold stomach. The truth was he opposed all stimulants, however gentle. He did not smoke, and of course he did not drink; indeed, he had never tasted spirits, and was inclined to avoid people who had — a circumstance that did not shrink his social circle as much as might be supposed, for the center of that circle was supplied by the members of Garden City's First Methodist Church, a congregation totaling seventeen hundred, most of whom were as abstemious as Mr. Clutter could desire," Capote described the Clutter patriarch. A few pages later in the first chapter, Perry Smith makes his entrance into Capote's book. "Like Mr. Clutter, the young man breakfasting in a cafe called the Little Jewel never drank coffee. He preferred root beer. Three aspirin, cold root beer, and a chain of Pall Mall cigarettes — that was his notion of a proper "chow-down." Sipping and smoking, he studied a map spread on the counter before him — a Phillips 66 map of Mexico — but it was difficult to concentrate, for he was expecting a friend, and the friend was late. He looked out a window at the silent small-town street, a street he had never seen until yesterday. Still no sign of Dick," Capote wrote. Brooks uses a visual link to draw victim and killer together, showing Herbert Clutter (John McLiam) performing his morning shave. As Clutter leans into the sink to rinse the remaining shaving cream from his face, the face that rises up and looks in the mirror sees Perry Smith, excising his excess whiskers as well.

The biggest difference between the book and the movie came with Brooks' introduction of a Truman Capote surrogate, a magazine reporter named Jensen, who travels to Holcomb to cover the case. Jensen isn't played in a way similar to the extremely distinctive Capote — such as the way that won Philip Seymour Hoffman an Oscar for Capote, that Toby Jones played even better in Infamous or that Tru himself played best of all as Lionel Twain in Neil Simon's 1976 mystery spoof Murder By Death. Brooks wrote the Jensen character straight (no pun intended) and conventionally, even giving him a narrator's function at times. He doesn't precisely follow how Capote researched the story though because Capote didn't arrive in Kansas until after Smith and Hickok had been apprehended. In the movie, Jensen arrives almost from the beginning of the investigation. For the role of Jensen, Brooks cast another veteran character actor — Paul Stewart, whose first credited screen role was the butler Raymond in Citizen Kane. His 42-year film and television career ended in 1983 with an episode of Remington Steele and he died three years later, a month shy of his 88th birthday. After starting with Kane, a few of Stewart's eclectic highlights included Champion, Brooks' Deadline-U.S.A., The Bad and the Beautiful, Kiss Me Deadly, Hell on Frisco Bay, King Creole, Opening Night, Revenge of the Pink Panther,

S.O.B. and appearances on nearly every episodic police or detective show between the 1950s and the 1970s, including The Mod Squad. The Jensen character arrives around the same time that the Kansas Bureau of Investigation joins the case led by John Forsythe as Alvin Dewey, what may be Forsythe's best performance. Brooks gives him a lot of speeches — and some come off as less pristine than others, but Forsythe succeeds at selling most of them. Forsythe gets so identified with Dynasty or as a voice on Charlie's Angels that I think people forget that he really act when the material was there for him as it was here or in the short-lived and underrated Norman Lear sitcom The Powers That Be and having fun with Hitchcock in The Trouble With Harry (though no one could help Topaz much). He also was a replacement performer of one of the major roles in Arthur Miller's All My Sons on Broadway. Granted, didn't see him, but he had to show some chops to land that one. Of his filmed work though, I think In Cold Blood stands as the best. Sure, this speech reads as overwrought, but he pulled it off as he delivered it to Jensen. "Someday, someone will have to explain the motive of a newspaper to me. First, you scream, 'Find the bastards.' Till we do find 'em, you want to get us fired. When we find 'em, you accuse us of brutality. Before we go

S.O.B. and appearances on nearly every episodic police or detective show between the 1950s and the 1970s, including The Mod Squad. The Jensen character arrives around the same time that the Kansas Bureau of Investigation joins the case led by John Forsythe as Alvin Dewey, what may be Forsythe's best performance. Brooks gives him a lot of speeches — and some come off as less pristine than others, but Forsythe succeeds at selling most of them. Forsythe gets so identified with Dynasty or as a voice on Charlie's Angels that I think people forget that he really act when the material was there for him as it was here or in the short-lived and underrated Norman Lear sitcom The Powers That Be and having fun with Hitchcock in The Trouble With Harry (though no one could help Topaz much). He also was a replacement performer of one of the major roles in Arthur Miller's All My Sons on Broadway. Granted, didn't see him, but he had to show some chops to land that one. Of his filmed work though, I think In Cold Blood stands as the best. Sure, this speech reads as overwrought, but he pulled it off as he delivered it to Jensen. "Someday, someone will have to explain the motive of a newspaper to me. First, you scream, 'Find the bastards.' Till we do find 'em, you want to get us fired. When we find 'em, you accuse us of brutality. Before we go into court, you give them a trial in the newspaper, When we finally get a conviction, you want to save 'em by proving they were really crazy in the first place. All of which adds up to one thing — you've got the killers," Dewey tells Jensen as he's taking down to the basement of the Clutter house. Dewey also serves as Mr. Exposition, explaining why these two numbskulls just out of prison would decide to go to this one particular farmhouse and rob this family, making sure to "leave no witnesses," even though Dick and Perry only gain $40 from the crime. A fellow investigator asks Dewey if Clutter might have been rich and Alvin sort of laughs knowingly. "Ahh — the old Kansas myth. Every farmer with a big spread is supposed to have a secret black box with lots of money in it." It isn't until the ending that you realize the Brooks gave Dewey some of that dialogue because he's supposed to symbolize the parts of the system that disgust him. Brooks ardently opposed capital punishment and he made no secret that he wanted the ending to make clear that it was murder. At Smith's hanging, another reporter asks Dewey about how much the executioner makes. "Three hundred dollars a man," Dewey answers. "Who does he work for? Does he have a name?" the reporter follows up and then poor John Forsythe has to deliver the clunkiest line of dialogue in the entire film. "Yes. We the people." Earlier, it had been the topic of discussion between Jensen and an imprisoned Hickock.

into court, you give them a trial in the newspaper, When we finally get a conviction, you want to save 'em by proving they were really crazy in the first place. All of which adds up to one thing — you've got the killers," Dewey tells Jensen as he's taking down to the basement of the Clutter house. Dewey also serves as Mr. Exposition, explaining why these two numbskulls just out of prison would decide to go to this one particular farmhouse and rob this family, making sure to "leave no witnesses," even though Dick and Perry only gain $40 from the crime. A fellow investigator asks Dewey if Clutter might have been rich and Alvin sort of laughs knowingly. "Ahh — the old Kansas myth. Every farmer with a big spread is supposed to have a secret black box with lots of money in it." It isn't until the ending that you realize the Brooks gave Dewey some of that dialogue because he's supposed to symbolize the parts of the system that disgust him. Brooks ardently opposed capital punishment and he made no secret that he wanted the ending to make clear that it was murder. At Smith's hanging, another reporter asks Dewey about how much the executioner makes. "Three hundred dollars a man," Dewey answers. "Who does he work for? Does he have a name?" the reporter follows up and then poor John Forsythe has to deliver the clunkiest line of dialogue in the entire film. "Yes. We the people." Earlier, it had been the topic of discussion between Jensen and an imprisoned Hickock.DICK: Perry's the only one talking against capital punishment.

JENSEN: Don't tell me you're for it.

DICK: Hell, hangin' only getting revenge. What's wrong with revenge? I've been revenging myself all my life.

Part of the film's brilliance stems from the way Brooks structures the scenes detailing the crime itself. Toward the beginning of the movie, he presents what probably remains the greatest sequence of his directing career without actually showing the murder. Then, as the film winds down, he shows us what we didn't see and it's horrifying. Through a window of the farmhouse, we can see Nancy kneeling beside her bed saying her prayers. At that moment, it isn't made clear who could be seeing that — are Dick and Perry outside her window or are we simply the voyeurs right then? A split second later we spot Dick and Perry still sitting in the car beneath the cover of night. I guess it was us. The discordant sound of a doorbell suddenly fills the soundtrack and the viewer realizes he or she has moved inside the Clutter house — and sunlight shines through the windows. The camera tracks slowly around the furniture of the living room as it makes its way toward the front door. A woman and some other people open the door calling out for the Clutters. We faintly hear church bells tolling and the visitors wear their Sunday best. The woman continues to call out the Clutters by their first names as she ascends the stairs to the second floor. The film cuts quickly to the house's

exterior just as we hear the woman let out a horrified scream. Coming on the heels of The Professionals, it's as if somehow Brooks transformed himself from a competent director and damn good writer into a master of both. I don't know if the fact he had Conrad Hall working as his d.p. on both films made any sort of difference or if that proved to be just fortuitous, but that one-two punch sealed Brooks' artistic reputation forever beyond what respect he'd earned before. I've never been fortunate enough to see In Cold Blood on the big screen and allow Hall's haunting and beautiful mix of light and shadow to bathe me in its glow, but I did get the next best thing when in 1993 at the Inwood Theater in Dallas I saw Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy and Stuart Samuels' documentary Visions of Light, a film devoted to the art of cinematography and highlighting some of its greatest practitioners and their best moments. One of the highlighted scenes comes from In Cold Blood when Robert Blake as Perry gives an emotional monologue about his father in his prison cell while he looks out the window at the rain coming down. The reflection of the raindrops cast shadows on Blake's face that make it appear as if he's crying. The moment stuns in its beauty — even when you learn that as so many say, accidents ends up producing some of the best parts of film. Hall admitted it hadn't been planned but the humidity in the prison set had pumped up the window's perspiration so much (as well as everyone else's) that's how the magic happened. Thankfully, YouTube had that clip.

exterior just as we hear the woman let out a horrified scream. Coming on the heels of The Professionals, it's as if somehow Brooks transformed himself from a competent director and damn good writer into a master of both. I don't know if the fact he had Conrad Hall working as his d.p. on both films made any sort of difference or if that proved to be just fortuitous, but that one-two punch sealed Brooks' artistic reputation forever beyond what respect he'd earned before. I've never been fortunate enough to see In Cold Blood on the big screen and allow Hall's haunting and beautiful mix of light and shadow to bathe me in its glow, but I did get the next best thing when in 1993 at the Inwood Theater in Dallas I saw Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy and Stuart Samuels' documentary Visions of Light, a film devoted to the art of cinematography and highlighting some of its greatest practitioners and their best moments. One of the highlighted scenes comes from In Cold Blood when Robert Blake as Perry gives an emotional monologue about his father in his prison cell while he looks out the window at the rain coming down. The reflection of the raindrops cast shadows on Blake's face that make it appear as if he's crying. The moment stuns in its beauty — even when you learn that as so many say, accidents ends up producing some of the best parts of film. Hall admitted it hadn't been planned but the humidity in the prison set had pumped up the window's perspiration so much (as well as everyone else's) that's how the magic happened. Thankfully, YouTube had that clip.It must be said how good a performance Blake gives while at the same time acknowledging that it can't be viewed the way many of us assessed it originally. When a Naked Gun movie pops up and you see O.J. Simpson play an idiot and constantly take a beating, somehow that's OK. When you watch In Cold Blood again and see Blake give such a convincing and chilling performance as a mass murderer (especially when Forsythe's Alvin Dewey engages him in conversation during the ride to jail and Perry tells him, "I thought Mr. Clutter was a very nice gentleman. I thought it right till the moment I cut his throat."), you can't help but recall that a few decades later, the actor stood trial and received an acquittal for killing his wife. It doesn't stand out as groundbreaking now, when last night's Mad Men said shit twice, but in 1967, In Cold Blood became the first major release to utter the word bullshit. For the second year in a row, Brooks received Oscar nominations for directing and adapted screenplay and Hall got one for cinematography. Quincy Jones also picked up a nomination for original score, though Jones didn't receive one for his music for In the Heat of the Night. I don't understand how the nimrods at the Academy left it out of the top five for best picture. They nominated two films that deserved to be there: Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate. The film that won, a fine film but certainly expendable: In the Heat of the Night. A perceived prestige project of social significance that's overrated as hell: Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. The fifth nominee that would make no sense in any year: Doctor Dofuckinglittle. Basically, three out of the five films could have been tossed to make room for In Cold Blood. A few other more deserving 1967 titles: Cool Hand Luke, The Dirty Dozen, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, Accident, Wait Until Dark, Point Blank, The Jungle Book. The National Board of Review did honor Brooks' direction. Brooks also received his sixth Directors Guild nomination and his sixth Writers Guild nomination. With the exception of the WGA, Brooks would never be named for any of the top awards again. In Cold Blood marked his best, but from there things went downhill fast.

One of the most difficult films to find (I've never seen it) for that recent a film with a best actress nomination. Brooks wrote his first original screenplay since Deadline-U.S.A. as a vehicle for wife Jean Simmons. From descriptions I've read, Simmons plays Mary Wilson, who was raised on romantic notions of marriage from the movies, finds herself in a funk on her anniversary and flies to the Bahamas on a whim, running into a free spirit (Shirley Jones) while there.

I missed this one as well. From TCM's web site; "In Hamburg, Germany, American Joe Collins (Warren Beatty) is considered by bank manager Kessel (Gert Fröbe) to be the most honest, hard-working bank security expert in the world. Unknown to Kessel, Joe has been devising a plan with his girlfriend, American expatriate prostitute Dawn Divine (Goldie Hawn), to take the contents from bank safe-deposit boxes owned by several criminals and place them into one owned by Dawn. Roger Ebert gave it three stars in his original review.

I wanted to see this one, but just ran out of time. Here's what qualifies as TCM's full synopsis: A former roughrider (Gene Hackman) matches wits with a lovely but shady lady-in-distress (Candice Bergen), as a drifting ex-cowboy (James Coburn) and a young, reckless cowboy (Jan-Michael Vincent) join in on a 700 mile journey. Ebert gave it three and a half stars in his original review.

I've actually seen this one. In fact, as we near the end of Brooks' career, I've watched two of the last three movies. As an unrelated sidenote, this year also marked the end of Brooks' 17-year marriage to Jean Simmons. If by chance you aren't familiar with this movie, think of it as sort of the Shame of the 1970s — and I don't mean the Ingmar Bergman movie. Diane Keaton stars as a teacher of deaf students whose affair with her college professor ends badly. She reacts as anyone would to a breakup — she starts cruising New York bars and picking up strangers for one-night stands while also developing a taste for drugs. The film definitely didn't belong in the genre of liberated women films of the 1970s as Keaton's character will pay. I saw this when I was a young man and I found it distasteful then, though it did have more sensible plotting than last year's Shame. Brooks directed his last performer to an Oscar nomination with Tuesday Weld getting a supporting actress nod. Keaton won the best actress Oscar for 1977 — but for Annie Hall. Brooks adapted a novel by Judith Rossen that was loosely based on a real incident, but most reviews by people who had read the novel seemed to indicate that Brooks changed key elements. Then, that matches the speech Brooks gave the movie's cast and crew on the first day of shooting, according to Douglass K. Daniel's Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks. "I'm sure that all of you have your own ideas about what kind of contributions you can make to this film, what you can do to improve it or make it better. Keep it to yourself. It's my fucking movie and I'm going to make it my way!" Daniel wrote. Goodbar also featured Richard Gere in one of his earliest roles. This clip plays off the tension of whether fun and games are at hands or something more dangerous.

Brooks referred to this film as "the biggest disaster" of his career. Later, he amended it slightly, blaming TV for purposely not coverage the film because the movie criticized "checkbook journalism." Having watched Wrong Is Right for the first time recently, this compels me to ask, "It did?" Sean Connery stars as a globetrotting reporting for what appears to be a CNN-like news station. The opening sequence contains some amusing moments, (including a young Jennifer Jason Leigh, nearly 30 years after her dad Vic Morrow played the worst punk in Brooks; Blackboard Jungle) but what could be cutting-edge satire of a media form just being born transforms into a scattershot satire involving fictional oil-rich African countries, the CIA, a presidential race and arms dealers trading suitcase nukes, Based on a novel, I hope that it had a plot, but Wrong Is Right just ends up being one of those strange satires like The Men Who Stared at Goats where once it ends you still don't know what the hell happened. This clip shows the opening sequence. Nothing after it deserves your attention.

I've got good news and bad news when it comes to Richard Brooks' final film. The good news: it brought him awards consideration again. The bad news: It was at the Razzies where it earned nominations for worst picture, worst director, worst screenplay and worst musical score. I'm not sure whether or not it relieved him that the film lost in all four categories, with Rambo: First Blood Part II taking worst picture, director and screenplay and Rocky IV winning worst score dishonors. I have not seen Fever Pitch which TCM hasn't even given a synopsis, but I know enough to tell you that Ryan O'Neal plays an investigator reporter doing a story on compulsive gambling who discovers he suffers from the problem. The subject of the movie came up on my Facebook page and Richard Brody, critic at The New Yorker, commented, "I saw Fever Pitch when it came out and loved every overheated second. Haven't seen it since then. Seeing The Connection has brought it back: no detached observer but a participant almost instantly in over his head." At the time of its release, it became one of the rare films that Ebert gave zero stars.

Following Fever Pitch, Brooks toyed with the idea of writing a screenplay about the blacklist, basing it around an incident in 1950 when fights broke out at the Directors Guild over the loyalty oath, but he didn't get around to it. The man who could be quite a bully on the set, had quite a bit of bitterness toward the industry by now as he showed in the second half of that 1985 interview.

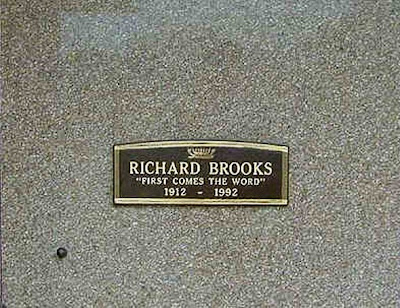

Richard Brooks died of congestive heart failure on March 11, 1992, at 79. He did have close friends, but most of them had died themselves by then. The stepdaughter he basically raised as his own when he married Jean Simmons, Tracy Granger, made certain, his tombstone bore the only appropriate epitaph for the man.

Tweet

Labels: Arthur Miller, blacklist, Books, Capote, Connery, Diane Keaton, Ebert, Hackman, Hitchcock, J.J. Leigh, James Coburn, Jean Simmons, Jewison, Mailer, N. Lear, Neil Simon, P.S. Hoffman, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

Truth be told, you two are both dragging me down

By Edward Copeland

By the time I finally found myself in a position to watch Shame, my expectations rested on two separate planes. The first, for the film itself, had settled on not anticipating being wowed, based not only on what I'd heard but also because (I must admit) I never managed to make it all the way through director Steve McQueen's first film, Hunger. The other plane existed on a much higher level, formed solely on what I'd witnessed of Michael Fassbender in 2011, giving great performances in movies that couldn't be more different — X-Men: First Class and Jane Eyre. I haven't even had a chance to catch him as Carl Jung in David Cronenberg's A Dangerous Method. However, I've witnessed many an actor or actress rise above mediocre material and I expected that if Shame turned out to be a subpar film, Fassbender still could deliver a superb performance. Unfortunately, thespians can do only so much with scripts as aimless, pointless and devoid of meaning as Shame. While Fassbender lets it all hang out in service to this lackluster screenplay, Carey Mulligan delivers the film's best performance, far better than Shame deserves, as Fassbender's character's sister.

Fassbender plays Brandon Sullivan, an Irish transplant to the U.S. who works as an executive in Manhattan. For what kind of business, it's never clearly stated, but it allows Brandon enough free time to leave the office for hours during the day to go to a hotel and have vigorous sex with multiple women. Now, sometimes Brandon does have to stay in the office. You might not be able to smoke inside public buildings in New York anymore, but masturbation breaks seem to be OK. At night, Brandon occasionally carouses with his married boss, David Fisher (James Badger Dale), who doesn't even try to hide his adultery from his employees. However, when loads of particularly nasty paid porn sites turn up on the hard drive of Brandon's work computer, Fisher immediately assumes that someone has hacked into Brandon's account or been using his computer when Brandon isn't there.

Based on the portrait painted in Shame, it seems that nearly all currently living in New York — including the women — carry attitudes toward sex that's more likely to be found in 14-year-old boys, only real 14-year-olds aren't getting laid at this high a percentage and the teens probably display more maturity and hold fewer fears of long-lasting relationships. Yes, I understand that Brandon is a sex addict, but the screenplay by director McQueen and Abi Morgan may depict the life of a sex addict but it never deals with the subject of sex addiction. Imagine a film about a heroin addict and the entire movie consists of the addict shooting up or snorting the drug, showing little in the way of consequence and no discussion of the addiction before the film finishes. That's almost what Shame amounts to as a film. Hell, the TV sitcom Cheers treated sex addiction more seriously and with laughs when in a later season Sam sought treatment for it.

The film's complication, i.e. Brandon's complication, stems from the arrival of his estranged younger sister, Sissy (Mulligan), who crashes at Brandon's apartment because she and her boyfriend are on the outs. Her arrival, according to the production notes and a couple of dialogue scenes inserted to break up the monotony of Brandon's boffing, throws his world into "chaos." As near as I can tell from the movie, chaos for Brandon (as well as McQueen and Morgan) equals having Sissy living in his apartment meaning he must go elsewhere to fuck. Poor baby. What also upsets Brandon is that Sissy gets a booking to sing at a New York club, which Brandon's boss David hears about, forcing Brandon to reluctantly accompany Fisher to see her show. The scene actually ends up being one of the film's few highlights as Mulligan performs the most downbeat version of Kander & Ebb's "New York, New York" you'll ever hear. It's reminiscent of the scene in Georgia when Jennifer Jason Leigh performs Elvis Costello's "Almost Blue." It certainly bears no resemblance to Liza Minnelli's version in Martin Scorsese's film of the same name that introduced the song or Sinatra's recording that immortalized it. Rubbing salt in Brandon's wound about Sissy interfering in his nightlife and his apartment, she and David end up going back to Brandon's place and having loud, boisterous sex, forcing a pissy Brandon to leave.

While visually, cinematographer Sean Bobbitt provides a cool blue tint that comes across as wholly appropriate to the film, Shame suffers from being overscored — not just by the original music composed by Harry Escott but the misuse of lots of Bach, mostly taken from Glenn Gould's recording of "The Goldberg Variations," alongside John Coltrane's instrumental cover of Rodgers & Hammerstein's "My Favorite Things" from The Sound of Music, Chet Baker's "Let's Get Lost" and Blondie's "Rapture" — all of which get played at near deafening levels at times to compensate for the largely dialogue-free sections. In a way, Shame sounds as if it's trying to be one of those late-night Skin-emax movies, only employing a classier soundtrack to play over the continuous coitus.

When Shame finally comes to a stopping place, they do allow Brandon and Sissy to have a conversation (more like a fight) to pretend that a point might have been hiding all along. Brandon has had it not being able to screw strangers in his own bed so he orders his sister out, telling Sissy that he's not responsible for her. He didn't give birth to her. "I'm trying to help you," Sissy tells him. "How are you helping me,

huh? How are you helping me? How are you helping me? Huh? Look at me. You come in here and you're a weight on me. Do you understand me? You're a burden. You're just dragging me down. How are you helping me? You can't even clean up after yourself. Stop playing the victim," Brandon responds bitterly. I have to agree with Brandon there. The film hasn't given any indication that Sissy has arrived to stage some sort of intervention. Hell, aside for her stumbling upon some live sex chat woman calling out for Brandon on his laptop and walking in on him beating off once, nothing indicates that Sissy has clued in on her brother's lifestyle. Then again, I don't notice much of a mess. "I'm not playing the victim. If I left, I would never hear from you again. Don't you think that's sad? Don't you think that's sad? You're my brother," Sissy declares. No, what's truly sad about this situation is watching talented actors such as Michael Fassbender and Carey Mulligan attempt to squeeze some sort of emotional truth from a movie that contained nothing but artifice up until that point. Fassbender tries his best, but he's burdened with the heavy lifting since he's in every scene and the shallow script leaves him rudderless. Carey Mulligan comes off looking so much better because her part takes up less time on screen so it's easier to give Sissy life even if the screenplay doesn't provide her any more depth than it does Brandon.

huh? How are you helping me? How are you helping me? Huh? Look at me. You come in here and you're a weight on me. Do you understand me? You're a burden. You're just dragging me down. How are you helping me? You can't even clean up after yourself. Stop playing the victim," Brandon responds bitterly. I have to agree with Brandon there. The film hasn't given any indication that Sissy has arrived to stage some sort of intervention. Hell, aside for her stumbling upon some live sex chat woman calling out for Brandon on his laptop and walking in on him beating off once, nothing indicates that Sissy has clued in on her brother's lifestyle. Then again, I don't notice much of a mess. "I'm not playing the victim. If I left, I would never hear from you again. Don't you think that's sad? Don't you think that's sad? You're my brother," Sissy declares. No, what's truly sad about this situation is watching talented actors such as Michael Fassbender and Carey Mulligan attempt to squeeze some sort of emotional truth from a movie that contained nothing but artifice up until that point. Fassbender tries his best, but he's burdened with the heavy lifting since he's in every scene and the shallow script leaves him rudderless. Carey Mulligan comes off looking so much better because her part takes up less time on screen so it's easier to give Sissy life even if the screenplay doesn't provide her any more depth than it does Brandon.That scene between the siblings toward the end of the movie reinforces what we got a slight glimpse of in an earlier scene where Brandon takes a co-worker named Marianne (Nicole Beharie) out for dinner. She's separated from her husband. While Brandon behaves meek and pliable at the restaurant, accepting every suggestion that either Marianne or the waiter (Robert Montano) makes, relationship talk brings out the opinionated side of him. He tells her that he doesn't believe in relationships — sees no point in them. When Marianne asks him how long his longest relationship lasted, Brandon answers four months. The two part for the night at her subway stop. The next day at work, we see what kind of universe Shame resides in. Marianne expressed a bit of dismissive judgment about Brandon the night before, but he takes her into the break room and kisses her passionately and Marianne willingly skips off from work with him to a hotel for a sexual tryst. This exemplifies the filmmakers' attitude toward pretty much every character in the movie.

The longer I think about Shame, the worse the film gets. If you set out to make a provocative film, it helps to have something to say. Your aim should be to provoke thought, not anger about the time wasted by talents such as Fassbender and Mulligan making it and movie lovers such as me watching it.

Tweet

Labels: 10s, Carey Mulligan, Cronenberg, Ebb, Fassbender, Hammerstein, J.J. Leigh, Kander, Liza, Music, Rodgers, Scorsese, Sinatra

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, February 13, 2012

"I am a most strange and extraordinary person"

By Michael W. Phillips Jr.

Christopher Isherwood's Sally Bowles, first seen in an eponymous 1937 novella, has been around (if you know what I mean) for 75 years in a variety of media, perpetually on the lookout for a chance to become a star. A young British girl looking for fame and fortune in Berlin in the waning days of the Weimar Republic, just before the rise of the Nazi Party, Sally found her way to the stage with John Van Druten's 1951 play I Am a Camera, then to Broadway with John Kander and Fred Ebb's 1966 musical Cabaret, and finally to the screen with Bob Fosse's film, which turns 40 today. A bewildering array of actresses have inhabited her along the way, I'm sure to varying degrees of success: Julie Harris, Natasha Richardson, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Gina Gershon, Debbie Gibson, Teri Hatcher, Molly Ringwald, Brooke Shields, Lea Thompson, Judi Dench, Jane Horrocks. But perhaps to most people, Sally Bowles is Liza Minnelli and Liza Minnelli is Sally Bowles. Sally got her most memorable actress and Liza got an Oscar.

This wasn't Minnelli's first brush with the material: Darcie Denkert, in her lavish 2005 book A Fine Romance, tells us that Kander and Ebb had wanted Minnelli for the stage back in 1966, but director Harold Prince thought she was too young, too American, and too good a singer to play the young, British, barely talented denizen of the Berlin nightlife. In a way Prince was right: Minnelli is such an astoundingly good singer that Sally's self-confident assurances that she'll make the big time someday don't seem completely groundless. But it's still obvious that Sally won't make it, perhaps for the more subtle reason that her towering talent is unfortunately coupled with an utter lack of judgment, her impetuousness covering a sea of self-doubt.

Sally Bowles may be the focus of the film, but the most interesting character is Joel Grey's Emcee, an androgynous, grease-painted sprite with a wicked grin, which Grey originated on stage. Denkert speculates that the Emcee has his roots in a 1930 Thomas Mann novella called Mario and the Magician, about an Italian mesmerist who uses his powers to control his audience. But he reminded me more of another hypnotist, Dr. Woland (Satan in disguise) in Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita, who, like the Emcee, seemed less of a fascist cheerleader than a bringer of chaos. The "decadence" of the Weimar Republic is on full display in the Kit Kat Club, and the Emcee gleefully whips his little corner of the world into increasing levels of the very things that the Nazis claimed to be so upset about. This connection is impossible, of course, since Bulgakov's novel wasn't published in English until after the Broadway run started, but I wouldn't be surprised to discover that Joel Grey had it in mind when he transferred his iconic character to the screen.

Because I've never seen or read any of its sources, questions of faithfulness or relative merit are thankfully not ones I can answer. Fosse and screenwriter Jay Presson Allen made several radical changes in transferring the story to the screen, starting with the music. They cut most of the "book" songs from the stage production, removing most of the secondary characters' vehicles for expression of their emotions, pushing them into the background and foregrounding Sally and the Emcee. Now all the songs (with one stunning exception) take place in the cabaret, and only Sally gets a traditional "book" song, wherein the singer gives voice to an inner monologue. This is the new addition "Maybe This Time," which Kander and Ebb had written for Minnelli back in 1963 and which, despite its magnificence, doesn't feel right in the film because Minnelli is unable to restrain her stupendous voice, and the scene starts to feel like she's making a statement about her talent in relation to her famous mother's instead of doing what's necessary for the character. Kander and Ebb wrote several other new songs, and a quick listen to the original cast recording tells me that I generally agree with the subtractions and additions.

From what I've read, this is less an adaptation than a reconceptualization into something that has roots on Broadway but also looks back to Isherwood's stories and forward into a radical new kind of film musical. It's a thing created from the raw material of the long-running Broadway sensation, but crafted into something that is first and foremost a film. Fosse uses his trademark abrupt editing to do something that would have been impossible on stage: by jarring cross-cutting between the stage and the outside world, he drives home the parallel between the increasing violence and decadence of the Emcee's show and the violence and decadence of the Nazis' rise to power. The boozers and good-time gals who hang out in the Kit Kat Club are there in part to escape reality, but Fosse and editor David Bretherton won't let us forget that the real world is still out there, and it's getting scarier by the measure. Kander and Ebb hated the film at first viewing because it wasn't what they had written, but gradually came to the conclusion that Fosse had created something completely new that was in fact a triumph.

The most triumphant thing for me is how deftly Fosse shrinks and expands the space of the stage. Most adaptations of musicals attempt to shed their "staginess" by setting scenes outdoors or adding new outdoor scenes, and this is no exception. But few, I think, play so adeptly with that staginess. Sometimes the Kit Kat Club seems as big as the Hollywood Bowl, packed to the gills with leering mutton-chopped men and bored women, and the stage seems like it's a tiny thing a mile away. Other times the club feels like it's the size of a telephone booth, and we can almost taste the sour sweat of the patrons and narrowly avoid the swinging limbs of the performers who loom above like giants. Sometimes the stage feels like the whole world. Fosse achieves this through camera placements and movements, use and eschewing of spotlights, and although it's not a perfect technique, it's more often than not a revelation. Much like the film itself: it's not the best musical ever made, and it has its flaws, but it's a wholly original creation that did much to clear away the big-budgeted, uncreative monstrosities that had come to characterize the genre in the late 1960s.

Michael W. Phillips Jr. is a Chicago-based film writer and programmer. He's the webmaster for Goatdog's Movies, and he programs films for the Chicago International Movies & Music Festival and the nonprofit film series South Side Projections.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Dench, Ebb, Fiction, Fosse, H. Prince, J.J. Leigh, Kander, Liza, Movie Tributes, Musicals, Oscars, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, March 12, 2011

From the Vault: Georgia

Like Leaving Las Vegas, Georgia will not be everyone's cup of tea, at least based on the astounding number of walkouts during the screening I attended. While Georgia doesn't approach Vegas' level of greatness, it is a consistently fascinating character study strengthened by both acting and singing.

Jennifer Jason Leigh stars as Sadie, younger sister to the film's title character, a hugely successful singer. Sadie aspires to be a singer as well, but she lacks Georgia's talent. Instead, Sadie concentrates more on her suffering than her singing, bouncing between jobs and gigs as well as alcohol and heroin.

Georgia (Mare Winningham) has long served as Sadie's enabler, supplying her with cash and a place to stay when Sadie bottoms out, which she does frequently. The two share a sibling affection poisoned by resentment — Sadie's jealousy of Georgia's success and Georgia's fatigue at being Sadie's savior.

Georgia was directed by Ulu Grosbard and written by Barbara Turner, Leigh's mother. The film could have been a masterpiece of observation, but it drags a bit too much in its last section once Sadie finally enters detox.

What's so fascinating about Georgia is the decision to play most of its key scenes in song instead of dialogue, culminating in an excruciating scene where a completely plastered Sadie delivers a long performance of a Van Morrison song at an AIDS benefit that Georgia is headlining.

Leigh has shown she's a master at playing this sort of desperation before, but she enlivens Sadie with humor and an enthusiasm that seems to belie the depths of her problems. Winningham's role is quieter, but her acting is just as sharp, especially with Leigh to bounce off.

Other fine performances come from Max Perlich as a young man with a crush on Sadie, Ted Levine as Georgia's husband and John Doe as Sadie's ex-lover and bandmate.

Georgia won't be for all tastes, but for discriminating moviegoers who relish finely tuned observations over easy-to-follow formula, Georgia should not be missed.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, J.J. Leigh

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Sun-baked noir drawn from a dime store novel

By Edward Copeland

As I watched After Dark, My Sweet again, in preparation for this 20th anniversary piece, I was struck once again by the melancholy that often hits people like myself who have spent much of their lives trying to

devour works in various fields of artistic endeavor. My readers realize my film obsession and my brief and expensive addiction to New York theater, as well as to various television shows. I've also tried to be a voracious reader, which I have been for most of my life except for frequent periods when severe headaches interfered. There simply isn't enough time in the day to watch and read (and listen: I like music too) and then write about them. I feel like Burgess Meredith in the classic Twilight Zone episode, though at least my eyesight is holding out so I don't have to worry about breaking my glasses after the bomb falls. Anyway, among the many regrets in my life is that I've never read any of the classic Jim Thompson pulp fiction novels, which enjoyed a resurgence in terms of film adaptations in the late 1980s and early 1990s of which James Foley's After Dark, My Sweet was the finest example. Even though my finances always hover in a precarious state and Thompson's books can't be bought for two bits anymore, after I rewatched the film, I did put out $7 to read the novel before sitting down to write this tribute. Of course, I had heard Thompson's words before because he'd also worked as a screenwriter, most notably on Stanley Kubrick's The Killing and Paths of Glory.

devour works in various fields of artistic endeavor. My readers realize my film obsession and my brief and expensive addiction to New York theater, as well as to various television shows. I've also tried to be a voracious reader, which I have been for most of my life except for frequent periods when severe headaches interfered. There simply isn't enough time in the day to watch and read (and listen: I like music too) and then write about them. I feel like Burgess Meredith in the classic Twilight Zone episode, though at least my eyesight is holding out so I don't have to worry about breaking my glasses after the bomb falls. Anyway, among the many regrets in my life is that I've never read any of the classic Jim Thompson pulp fiction novels, which enjoyed a resurgence in terms of film adaptations in the late 1980s and early 1990s of which James Foley's After Dark, My Sweet was the finest example. Even though my finances always hover in a precarious state and Thompson's books can't be bought for two bits anymore, after I rewatched the film, I did put out $7 to read the novel before sitting down to write this tribute. Of course, I had heard Thompson's words before because he'd also worked as a screenwriter, most notably on Stanley Kubrick's The Killing and Paths of Glory.What makes Foley's film work so well is its casting of Jason Patric in the lead role of former boxer and recent mental institution escapee Kid Collins. One difference between the novel and the movie: His first name in the

book is William, but the screenplay by Foley and Robert Redlin christens him Kevin, though it hardly matters since he's almost always referred to as Collins or, once he encounters the widow Fay Anderson (Rachel Ward), Collie. The book also describes him as blond, which the dark-haired Patric certainly is not. The movie, which like the novel, is narrated by Collins, doesn't make it clear what his problem is. Has he been punched a few too many times in the ring? Did guilt over killing another fighter in the ring set him off? Maybe he just has criminal tendencies, though at times he seems as gentle as Lennie in Of Mice and Men. Still, he's also prone to sudden rage that you don't want to find yourself on the receiving end of. On the first page of the novel, Collins shows the reader the classification card that has accompanied him through four mental institutions:

book is William, but the screenplay by Foley and Robert Redlin christens him Kevin, though it hardly matters since he's almost always referred to as Collins or, once he encounters the widow Fay Anderson (Rachel Ward), Collie. The book also describes him as blond, which the dark-haired Patric certainly is not. The movie, which like the novel, is narrated by Collins, doesn't make it clear what his problem is. Has he been punched a few too many times in the ring? Did guilt over killing another fighter in the ring set him off? Maybe he just has criminal tendencies, though at times he seems as gentle as Lennie in Of Mice and Men. Still, he's also prone to sudden rage that you don't want to find yourself on the receiving end of. On the first page of the novel, Collins shows the reader the classification card that has accompanied him through four mental institutions:William ("Kid") Collins: Blond, extremely handsome; very strong, agile. Mild criminal tendencies or none, according to environmental factors. Mild multiple neuroses (environmental) Psychosis, Korsakoff (no syndrome) induced by shock; aggravated by worry. Treatment: absolute rest, quiet, wholesome food and surroundings. Collins is amiable, polite, patient, but may be very dangerous if aroused...

Except for the name change and the updating of the time period, the film sticks fairly closely to the book. Both are narrated by Collins, except the book shows that he isn't the swiftest guy in the world in terms of mastery of the English language while some of the internal lines the film gives him come off as a bit too well-formed for the character. The novel also makes his motivations much clearer than the film which by leaving things out make some scenes seem like a cheat or purposely vague. In a way, the Collie of the film is even more of an unreliable narrator than the Collie of Thompson's novel.

Of course, noir purists might dismiss a story set in modern time and filmed in sun-drenched color (to match its southwestern locale, it even includes a nice score from Maurice Jarre, the great composer of Lawrence of Arabia), but it hits all the marks. Still, as good as Foley's film is, Patric holds the key to its success in his

portrayal of Collins. It's the best role of the talented actor's odd film career. Whether Collie has just been hit in the head one time too many or is just naturally mentally unbalanced (or perhaps he's smarter than we think and it's all a put on), Patric handles the turns of uncertainty in his part beautifully. The year following After Dark, My Sweet he had another good role opposite Jennifer Jason Leigh in Rush playing an undercover cop who becomes too involved in the drugs he is investigating, but that film and performance were overshadowed by Patric's tabloid fame as the man who broke up Julia Roberts and Kiefer Sutherland before they could wed. Given that Patric also is Jackie Gleason's grandson and the son of Jason Miller, Oscar-nominated actor for The Exorcist and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright of That Championship Season, I can't help if all that attention has played a role in a purposeful obscurity. If so, it's a shame, because Patric has remarkable talent that's not seen nearly enough as it's on display in After Dark, My Sweet or in a handful of other films such as Your Friends and Neighbors.

portrayal of Collins. It's the best role of the talented actor's odd film career. Whether Collie has just been hit in the head one time too many or is just naturally mentally unbalanced (or perhaps he's smarter than we think and it's all a put on), Patric handles the turns of uncertainty in his part beautifully. The year following After Dark, My Sweet he had another good role opposite Jennifer Jason Leigh in Rush playing an undercover cop who becomes too involved in the drugs he is investigating, but that film and performance were overshadowed by Patric's tabloid fame as the man who broke up Julia Roberts and Kiefer Sutherland before they could wed. Given that Patric also is Jackie Gleason's grandson and the son of Jason Miller, Oscar-nominated actor for The Exorcist and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright of That Championship Season, I can't help if all that attention has played a role in a purposeful obscurity. If so, it's a shame, because Patric has remarkable talent that's not seen nearly enough as it's on display in After Dark, My Sweet or in a handful of other films such as Your Friends and Neighbors.The plot's engine ignites simply enough. Collins steps off the hot road into a saloon to get a cold beer from a disinterested bartender named Bert (Rocky Giordani) while sitting further down the bar is an attractive woman whose name he'll learn is Fay (Ward). Collins, as is his habit, tends to ramble, but in a good-natured

way, telling about how he's lost track of his friend Jack Billingsley, but he's certain he'll wander in that bar at some point. Bert and Fay, recognizing that Collins may be a bit slow, have a bit of fun at the kid's expense, until it ceases to be fun for them anymore because Collins just won't shut up. Bert grabs the beer back before Collins can even finish it and tells him to get out. Collins insists that he hasn't done anything wrong: He's a veteran and just waiting on a friend. Bert doesn't care and reaches across the bar and grabs Collins' shirt. That's a mistake. Before you know it, Bert lies sprawled and Collins has hit the road again. He's surprised when Fay pulls up alongside him in her car, offering a ride. He thinks it's a scam and she'll take him back to the bar and the cops, but Fay insists that Bert is the last person who wants to be involved with the police. Reluctantly, Collins climbs in the vehicle and they drive to Fay's rundown plantation.

way, telling about how he's lost track of his friend Jack Billingsley, but he's certain he'll wander in that bar at some point. Bert and Fay, recognizing that Collins may be a bit slow, have a bit of fun at the kid's expense, until it ceases to be fun for them anymore because Collins just won't shut up. Bert grabs the beer back before Collins can even finish it and tells him to get out. Collins insists that he hasn't done anything wrong: He's a veteran and just waiting on a friend. Bert doesn't care and reaches across the bar and grabs Collins' shirt. That's a mistake. Before you know it, Bert lies sprawled and Collins has hit the road again. He's surprised when Fay pulls up alongside him in her car, offering a ride. He thinks it's a scam and she'll take him back to the bar and the cops, but Fay insists that Bert is the last person who wants to be involved with the police. Reluctantly, Collins climbs in the vehicle and they drive to Fay's rundown plantation.At her place, Fay reveals to Collie that she's a widow (she doesn't need to reveal that she's an alcoholic; even someone as slow as Collins can figure that out) and offers him a trailer on her property as a residence. As the two are getting acquainted in the main house, a car pulls up and Fay rushes out to see the man, almost as if she wants to steer him clear of Collie. That doesn't last long. As Collie and Fay go out that night, the man stumbles upon them again. His name is Garrett Stoker (played with a wonderful sleaze quotient by Bruce Dern), but everyone knows him as Uncle Bud. Thompson's, i.e. Collins', description of Uncle Bud in the novel truly hits the mark in a delightful introductory sequence:

You meet guys like Uncle Bud — just over a drink or a cup of coffee — and you feel like you'veknown them all your life. They make you feel that way.

The first thing you know they're writing down your address and telephone number, and the next thing you know they're dropping around to see you or giving you a ring. Just being friendly, you understand. Not because they want anything, you understand. Sooner or later, of course, they want something; and when they do it's awfully hard to say no to them. No matter what it is.

Uncle Bud says he's a former police detective and, yes, he does want Collie for something: to be part of a scheme he's been trying to sell Fay on for several months: kidnapping the young son of a wealthy family and collecting a big ransom. Fay and Collie both humor Uncle Bud, but later at Fay's house, she tells him that Uncle Bud has been trying to find a third for his cockeyed plan for a long time and it would be in Collie's best interest to get as far away from both of them as fast as he can.

Collins takes Fay's advice and stops off at a diner, where he bring his own booze much to the counterman's anger (as well as his usual spiel about waiting for Jack Billingsley). The counterman asks him to at least go wait in an out-of-the-way booth so he won't get in trouble and Collins complies, though being slightly tipsy, he

stumbles into the booth of a man who turns out to be a doctor named Goldman (George Dickerson). The doctor recognizes the signs in Collins of someone who's been in a mental health facility and offers him some help. Collins refuses, though the doctor gives him his card anyway. Later, without any prospects, Collins looks up Doc Goldman, figuring he has nothing else to lose, so he might as well work some odd jobs and maybe find a nice place to stay for awhile. The doctor, who practices out of his home, is glad to see him and lets him do yard work in exchange for room and board. He tries to talk to Collins about his past and whether or not he needs to go back to an institution or, at the very least, quit boozing, but Collins isn't receptive to the idea. The biggest problem concerning Collins is that he can't get Fay out of his mind and he wonders if she's safe from Uncle Bud's plotting. His worry eventually leads him to flee again, back to Fay and getting himself neck deep in the kidnapping plan.

stumbles into the booth of a man who turns out to be a doctor named Goldman (George Dickerson). The doctor recognizes the signs in Collins of someone who's been in a mental health facility and offers him some help. Collins refuses, though the doctor gives him his card anyway. Later, without any prospects, Collins looks up Doc Goldman, figuring he has nothing else to lose, so he might as well work some odd jobs and maybe find a nice place to stay for awhile. The doctor, who practices out of his home, is glad to see him and lets him do yard work in exchange for room and board. He tries to talk to Collins about his past and whether or not he needs to go back to an institution or, at the very least, quit boozing, but Collins isn't receptive to the idea. The biggest problem concerning Collins is that he can't get Fay out of his mind and he wonders if she's safe from Uncle Bud's plotting. His worry eventually leads him to flee again, back to Fay and getting himself neck deep in the kidnapping plan.

While After Dark, My Sweet exists at its core as a thriller and contains the many twists you'd expect, Foley's keeps his pacing loose, yet it never loses your attention. I'll spare you the details, in case you haven't seen the film or read the book, but it's riveting and suspenseful without building tension so taut it breaks. The one misstep I think Foley makes is an extended sex scene between Patric and Ward. It is important for a plot development, but the romp wastes too much screentime and almost brings the film to a halt. In the novel, Thompson accomplishes the same thing in a mere paragraph that's mostly allusion but the film's version goes on way too long. As Orson Welles once famously said, the two things that always look fake on film are praying and making love, and Foley certainly proves that adage with the length of the boinking here.

Still, that criticism is a minor one for an otherwise great film anchored by such a magnificent performance. Since I read the novel after having seen the film multiple times, it's hard to say which is better, though the book certainly makes things clearer and works more efficiently. Foley managed to come up with a more ambiguous ending than Thompson did and how often does that happen in a film? Not nearly enough anymore really, but 20 years ago it did and thank goodness that Foley cast an actor as talented as Jason Patric to pull it off. I just wish we got to see Patric put his gifts to use in worthy projects more often.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Books, Burgess Meredith, Fiction, J.J. Leigh, Jim Thompson, Julia Roberts, K. Sutherland, Kubrick, Movie Tributes, Welles

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Three strikes and you're out

By Edward Copeland

Think how much money could be saved the next time Noah Baumbach seeks financing for a film if instead of someone ponying up for a full-scale production, they simplify the process by simply giving him a cameraman and filming his sessions with his psychiatrist. Better yet: Don't actually film them and spare viewers from having to endure Baumbach working through his issues.

Many artists have worked through their neuroses in their art and done so in astoundingly great works of film, literature, theater and television. While Baumbach has been at it a while and I admit I haven't seen his earlier directing efforts, his last three films do so in such an overt way with such annoying and downright unlikable characters that you wish you could enter the film and slap the whole fucking lot of them.

With The Squid and the Whale, the ensemble of Jeff Daniels, Laura Linney, Jesse Eisenberg and even young Owen Kline were so good that their performances managed to overcome the script's deficiencies and make the experience of watching the film less painful than it might otherwise have been.

Then came Margot at the Wedding, which I would call insufferable if I weren't afraid it could come off as high praise for such a miserable waste of film.

While the screenplay for Greenberg is credited to Baumbach, surprisingly story credit is shared between him and his real-life wife, the gifted actress Jennifer Jason Leigh, who has a small role in this film. I hate to blame her for part of this mess as well, especially considering that she co-wrote and co-directed, with Alan Cumming, the underrated 2001 gem The Anniversary Party.

Ben Stiller stars as Roger Greenberg, recently released from a mental hospital in New York, who travels to Los Angeles to housesit for his brother while he and his wife take a trip to Vietnam. This brings Roger in contact with his brother's assistant Florence (Greta Gerwig), the only character in the film that doesn't come off at some point as an asshole.

I do have praise for one scene. When Roger decides to throw a party that somehow attracts throngs of twentysomethings, he launches into a coke-fueled speech about their generation that I do have to admit was quite funny. It was Stiller's best moment as well as the movie's. Also, I'll give Greenberg this much: It's not as painful as Margot at the Wedding was, where I dreamed of a Dynasty-style terrorist massacre to take out the entire wedding party.

I could delve further into the machinations of the story of Greenberg, but it's honestly not worth the effort. Once I finished the torture of watching the film, I would have ejected the DVD, but out of habit I checked to see what bonus features were offered. One was titled "Greenberg: A Novel Approach." In it, Baumbach, obviously suffering from delusions of grandeur, said he hoped to make a movie similar to a novel that would have been written by a Philip Roth or John Updike or Saul Bellow.

Of course, the only thing Greenberg has in common with those writing greats is that their books and Baumbach's screenplay were printed in English. To make the extra more ridiculous (before I shut it off) others involved in the film tried to compare it to classic films of the 1970s, such as something Hal Ashby might have made.

So, it's going to take a lot of convincing to get me to watch the next Noah Baumbach-directed project. I'll be nice and go easy on movies he only participates in the writing of, even though I've only liked one of those, Fantastic Mr. Fox. Next time Noah, maybe you should let your wife do the heavy lifting.

Tweet

Labels: 10s, Ashby, J.J. Leigh, Jeff Daniels, Laura Linney, Roth, Updike

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, May 01, 2010

From the Vault: Short Cuts

Helicopters hover in the night, spraying Los Angeles with pesticides in hopes of exterminating the dreaded Mediterranean fruit fly. In Short Cuts, Robert Altman's Raymond Carver-inspired vision of L.A., it's humanity that seems on the verge of extinction as the master director uses Carver's wonderful stories as a springboard for his epic look at modern life.

Fresh from the triumph of The Player, Altman returns to the style of filmmaking he mastered in the 1970s, creating an astounding cinematic canvas of memorable characters and sly observations.

Twenty-two main characters populate the L.A. of Altman's screenplay, co-written with Frank Barhydt. Unlike the movers and shakers of Hollywood depicted in The Player, Altman zeroes in on the people who surround Hollywood's elite in the suburbs — working- and middle-class citizens struggling with marriages and jobs, natural disasters and human tragedies. Singling out some cast members above others in this top-notch ensemble seems unfair, but the standouts in my mind are Jack Lemmon, Tim Robbins and Jennifer Jason Leigh.

Lemmon plays a long-absent father who pays a surprise visit to his estranged son and embarks on a funny, touching and wholly inappropriate confessional in a hospital cafeteria. Lemmon makes each syllable of his dialogue resonate to the point that the consonant B rings out of the word robe to hilarious effect.

Robbins similarly straddles the line between humor and pathos as a chronically unfaithful husband who hates the family dog and distrusts his cheating mistress.

Leigh, who always turns in an interesting performance, soars as a phone sex operator who works at home while taking care of her children and her husband.

Picking out those three actors should in no way diminish the accomplishments of the rest of the cast which includes memorable turns by Andie MacDowell, Bruce Davison, Julianne Moore, Matthew Modine, Anne Archer, Fred Ward, Chris Penn, Lili Taylor, Robert Downey Jr., Madeleine Stowe, Lily Tomlin, Tom Waits and still others.

The weak points of Short Cuts stem from the storyline involving a lounge singer (Annie Ross) and her cellist daughter (Lori Singer). That strand is the only one that Altman created from scratch instead of being drawn from Carver and it stands out as somewhat standard and predictable in comparison.

For Carver fans, Altman doesn't render a faithful adaptation but merely uses the writer as a launching pad for this incredible work. The story that most closely resembles its Carver origins is the one based on "A Small, Good Thing," but the quick intercutting of the various tales slightly undermines its emotional payoff in the film. However, only readers of the story will probably notice.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Altman, J.J. Leigh, Julianne Moore, Lemmon, Lily Tomlin, Robert Downey Jr., Tim Robbins

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, December 16, 2008

Can We Skip the Reception?

By Josh R

There are moments when I get why people — specifically, the sort of people who exult the virtues of “the heartland” — can’t stand all us crackpot, bleeding heart, hippy-dippy liberals. I had one of those moments watching Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married, ostensibly a film about dysfunctional family relationships but really more of a patchwork paean to multiculturalism and progressive left-wing attitudes, and a rather self-congratulatory one at that.

As the title suggests, the film takes place at a wedding — not just any wedding, mind you, but the kind that would send an over-the-hill ACLU lawyer still pining for the glory days of Ann Arbor into fits of ecstasy. The bride is white, the groom is black, the guests represent every color and creed under the sun, the theme is Indian (as in: the bridesmaids wear saris and the wedding cake is adorned with the figure of a large spangled elephant), and the guitars and tambourines are out in full force. Seemingly every musician and performance artist from within a 12 mile radius of Ulster County has been recruited to participate in the nuptial festivities — this means we hear everything from reggae music performed on kettle drums to modern indie folk rock to wailing Yoko Ono types. Basically, it’s Woodstock with place settings and a good champagne. Now, all of this might make sense in a film that was sending up the pretensions of liberalism as a cultural attitude, but Rachel is enacted with an entirely straight face and without a trace of irony. The kids who are too cool for school (but took tons of critical theory courses) are showing us how hip and evolved they are, and patting themselves on the back for it. As someone who’s been to a few Williamsburg coffee houses in my time, I can tell you that a little of this particular brand of self-absorption goes a long way — and is fairly intolerable in large quantities. By the time the Brazilian Carnivale dancers in feather headdresses arrive to form a conga line, I would have welcomed a canned recording of Karen Carpenter singing “Close to You” as if someone had tossed me a life ring.

The plot of Rachel Getting Married is virtually beside the point; it’s hard to avoid the feeling that the movie Demme really wanted to make was a concert film, until some savvy producer badgered him into padding it out with an actual storyline. Kym, played by Anne Hathaway (with badly cropped hair and raccoon-eye makeup to let us know she’s edgy, misunderstood and has tons of emotional baggage), is a recovering druggie just sprung from rehab to participate in her sister’s wedding. Old wounds are reopened and administered with heaping spoonfuls of salt en route to the big day, as Kym must confront the sins of her past and her unresolved feelings toward her nearest and dearest. Hathaway is fine in what seems like a foolproof role for an actress aiming to show that she can stretch. It’s one that’s been played so many times that it contains very little surprise at this point, and to be honest, the performance doesn’t have a fraction of the depth or originality that, say, Jennifer Jason Leigh brought to Georgia. Whenever a squeaky-clean good girl takes on an edgy bad girl role, critical hosannahs are never far behind; Hathaway is not a bad actress, but Rachel Getting Married doesn’t reveal any new wrinkles to her talent — and really, given what an attention-grabing role it is, it doesn’t really represent much of a risk for her. Better is Rosemarie De Witt as the titular bride, although the character is outlined in such vague terms that there really isn’t very much she can do with it. Lagging far behind the women is Bill Irwin, a very fine stage actor whose performance as the father is a bit too ingratiating to be entirely convincing; Anna Deveare Smith is thoroughly wasted in the role of the sympathetic stepmother.

The most interesting performance in the film is given by Debra Winger as Abby, the curiously detached mother who has withdrawn from her family to such an extent that her appearance at her own daughter’s wedding has an uncomfortable air of formality. Abby is hardly the emotionally barren, tightly wound bitch from Ordinary People — it is clear that she still loves her daughters, and still feels the tug of the parent-child bond; she has simply compartmentalized her feelings to such an extent that she can no longer comfortably acknowledge them. Winger could do wonders with this role — frankly, she does small wonders with what little she has — but is both criminally underused and badly betrayed by the film’s editing. The most loaded scene in Rachel Getting Married is the inevitable confrontation between Kym and Abby; Demme abruptly cuts away from it before it’s reached a natural conclusion, leaving both the actresses and the audiences high and dry. Ultimately, I’m not sure drama has very much place in Rachel Getting Married — it would detract too much focus from the kettle drums, the Bollywood decor and the conga line.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Anne Hathaway, Debra Winger, Demme, J.J. Leigh

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, February 25, 2008

It's meant to be funny?

At one point in Margot at the Wedding, a frustrated Malcolm (Jack Black) tells his fiancee Pauline (Jennifer Jason Leigh) that both she and her sister Margot (Nicole Kidman) are "fucking morons." When Jack Black is the voice of reason, you know you are probably in trouble and Noah Baumbach's film is the most excruciatingly bad moviegoing experience I've had among 2007 releases.

I can't imagine how much time Baumbach has spent in therapy in his life, but the bills must be astronomical. (If he hasn't been in therapy at all, The Squid and the Whale and this piece of shit are strong evidence that perhaps he should be sent forcibly to a mental health facility.)