Thursday, March 29, 2012

…I pull you back in

By Edward Copeland

Among film buffs and people coming of mature moviegoing age in the 1970s, the name John Cazale engenders sadness in many of them. Featured in prominent roles in five features between 1972 and 1978, each received a nomination for the best picture Oscar and three of them won. However, by the time The Deer Hunter, the fifth of those films, was nominated along with Cazale's fiancée, Meryl Streep, getting her first supporting actress nomination for that film, Cazale had been dead for almost a year, having lost his battle with cancer on March 12, 1978, at the age of 42, leaving behind one helluva legacy in a short span of time. In addition to The Deer Hunter, Fredo in both parts of The Godfather; Stan, the assistant to eavesdropping expert Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), in another Francis Ford Coppola masterpiece, The Conversation and, Cazale's greatest performance, in my opinion, as Sal, bank robbing partner of Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino) in Sidney Lumet's magnificent Dog Day Afternoon. This piece concerns The Godfather, so let's talk Fredo.

Cazale does fine as Fredo in The Godfather but, truth be told, his time on screen doesn't add up to a lot. His role increases in Part II, but he actually has less to do in the 1972 film than many of the non-Corleones. Fredo though has acquired a legacy almost removed from the film itself. The name has become synonymous with a ne'er do, usually a ne'er do well brother. I imagine people who can't name John Cazale as the actor who portrayed Fredo recognize what someone means if they refer to someone as a Fredo. The Urban Dictionary includes multiple definitions such as the simple "family's black sheep" to having sex with two waitresses simultaneously as Moe Greene claimed he caught Fredo doing and Vince Vaughn's character reference in Swingers. The truth of the matter just happens to be that Fredo Corleone, the middle son, can't stop fucking up. It's sad, because you see in Cazale's portrayal that Fredo wants to be a good son, but he's messed up so many times that even he understands why his family can't rely on him. His big, heartbreaking scene comes when rival gangsters make their assassination attempt on his father and Fredo bobbles his own gun, unable to shoot back. He ends up sitting on the curb, next to his critically wounded dad, the gun dangling from his hand, weeping like a child.

You'd think that Talia Shire had the easiest path to landing her role as Corleone daughter Connie, given that her brother Francis was directing the film, but Coppola says he almost didn't consider her for the part because he thought his kid sister was "too beautiful." Connie isn't much more than a plot point in The Godfather — a Corleone daughter to get wed, beaten and, finally, to lash out at her brother for killing her no-good husband. Shire and Connie don't get to grow into interesting characters until the sequels, for certain Part II and, reportedly, a re-edited Part III on DVD and Blu-ray that drastically improves that misfire, including her character's motivations. Walter Murch is said to have led the restoration and re-cutting of Part III, which was rushed in 1990 in order to qualify for the Oscars. Reported rumors that the new cut of Part III replaces Sofia Coppola with Andy Serkis have not been verified. The other major female role in The Godfather got more to do but, like Connie, developed even further in Part II. This was Diane Keaton's second feature film after Lovers and Other Strangers co-starring Richard Castellano (Clemenza). While Keaton proved often that she's adept at drama, she's always better in comedies as Woody Allen utilized with great success.

The don's oldest son and his adopted one represent fire and ice, and James Caan and Robert Duvall excel at those elemental levels as Sonny Corleone and Tom Hagen. One moment I noticed this time that I'd never observed before occurs when Sonny, after finding Connie beaten and bruised by Carlo, beats the hell out of his brother-in-law in the street. When Carlo grabs hold of a railing, Sonny actually bites into

Carlo's hands to make him let go (in front of a Thomas Dewey campaign poster no less). Going back to Coppola's concern about guys sitting around talking, you don't get tired of these two doing that, especially in scenes such as debating what actions to take following the attempt on their father's life. When Michael comes home with a swollen jaw courtesy of the crooked police captain, it sets Sonny off again, ready to go to war against Sollozzo. Tom, functioning as the levelheaded consigliere, tries to explain to his adopted brother that even the man upstairs recovering from his bullet wounds would understand that it wasn't personal.

Carlo's hands to make him let go (in front of a Thomas Dewey campaign poster no less). Going back to Coppola's concern about guys sitting around talking, you don't get tired of these two doing that, especially in scenes such as debating what actions to take following the attempt on their father's life. When Michael comes home with a swollen jaw courtesy of the crooked police captain, it sets Sonny off again, ready to go to war against Sollozzo. Tom, functioning as the levelheaded consigliere, tries to explain to his adopted brother that even the man upstairs recovering from his bullet wounds would understand that it wasn't personal.TOM: Your father wouldn't want to hear this, Sonny. This is business, not personal.

SONNY: They shoot my father and it's business, my ass!

TOM: Even shooting your father was business not personal, Sonny!

Caan dances through the movie, all energy, sometimes comic, sometimes violent, sometimes sexual. When brother Michael (Al Pacino) decides he doesn't want to be the straight-arrow civilian anymore, Sonny laughs at his kid brother, even using Hagen's words. "Hey,

whaddya gonna do, nice college boy, eh? Didn't want to get mixed up in the family business, huh? Now you wanna gun down a police captain. Why? Because he slapped ya in the face a little bit? Hah? What do you think this is the Army, where you shoot 'em a mile away? You've gotta get up close like this and — bada-BING! — you blow their brains all over your nice Ivy League suit. You're taking this very personal. Tom, this is business and this man is taking it very, very personal," Sonny teases. Of course, Duvall's path to success had been forming prior to The Godfather, but this did earn him his first Oscar nomination as supporting actor. Caan, Duvall and Pacino all earned supporting nominations, one of the rare times a single film grabbed three slots in an acting category. The Godfather Part II repeated the feat in the same category. It also had been achieved by On the Waterfront. The movie Tom Jones accomplished it in supporting actress and the 1935 Mutiny on the Bounty did it in best actor (out of four nominees), but this was prior to the creation of the supporting categories.

whaddya gonna do, nice college boy, eh? Didn't want to get mixed up in the family business, huh? Now you wanna gun down a police captain. Why? Because he slapped ya in the face a little bit? Hah? What do you think this is the Army, where you shoot 'em a mile away? You've gotta get up close like this and — bada-BING! — you blow their brains all over your nice Ivy League suit. You're taking this very personal. Tom, this is business and this man is taking it very, very personal," Sonny teases. Of course, Duvall's path to success had been forming prior to The Godfather, but this did earn him his first Oscar nomination as supporting actor. Caan, Duvall and Pacino all earned supporting nominations, one of the rare times a single film grabbed three slots in an acting category. The Godfather Part II repeated the feat in the same category. It also had been achieved by On the Waterfront. The movie Tom Jones accomplished it in supporting actress and the 1935 Mutiny on the Bounty did it in best actor (out of four nominees), but this was prior to the creation of the supporting categories.

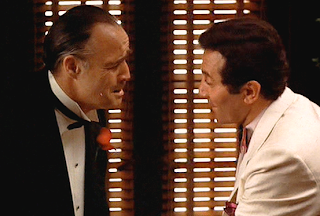

Which leaves us with the film's two most important characters who also happen to be its most important actors as well. One of the first practitioners of the Method who had set the world on fire and a brash newcomer with a new generation's take on the same style meeting together. The old master Marlon Brando, showing the world that he still had power, while the rising star Al Pacino makes his presence known loudly (back in the days when Pacino did this without being literally loud). Before watching the movie this time, I read someone commenting how as Michael shifts into Vito's role, Pacino subtly transforms physically. That swollen jaw from McCluskey's punch starts to resemble those cotton-stuffed jowls Brando gave Vito. When I did watch it, especially when you really pay attention to that great contribution from Robert Towne, it's as if Vito and Michael undergo a Persona-like transference. I believe the key moment of Michael's switch happens when he protects his father at the hospital, hiding his bed in the stairwell and

clutching his hand, whispering, "I'm with you now, pop." The don, who hasn't regained consciousness since the shooting, does then and gives his son the sweetest smile. It's a touching moment — if you forget the family business. Everyone debates whether Brando has the movie's lead role or if that title really belongs to Pacino. I always swear that I'm gonna add up minutes of screentime, but I can never do it because I get too involved. To me, it feels more or less as if it's an ensemble piece. Brando disappears for awhile after he's shot, but so does Pacino immediately after he flees the country. (It's worth pointing out that even the greatest films ever made have flaws. As I feel the Paris flashbacks in my beloved Casablanca come off as hokey, Michael's Sicily scenes and sudden marriage may be The Godfather's Achilles' heel.) What I know for certain is that both actors deliver great performances. You see very little of the Brando silliness that sometimes pop up with the most obvious example being when singer Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) seeks his help at the wedding at the don unmercifully mocks him as Fontane practically cries acting what he can do to get that movie part. Corleone shakes him vigorously and shouts, "You can act like a man!" He then slaps him and ridicules him further. "What's the matter with you? Is this what you've become, a Hollywood finocchio who cries like a woman?" Then the funny Brando comes out as he does a little girl voice, "'Oh, what do I do? What do I do?' What is that nonsense? Ridiculous!" You spot Tom Hagen laughing in the background, but part of me suspects that really was Duvall trying not to crack up. Other than that, Brando plays things remarkably straight and truthfully as when he calls in the favor the undertaker Bonasera owes him to clean up Sonny for his funeral. "Look how they massacred my boy," he cries.

clutching his hand, whispering, "I'm with you now, pop." The don, who hasn't regained consciousness since the shooting, does then and gives his son the sweetest smile. It's a touching moment — if you forget the family business. Everyone debates whether Brando has the movie's lead role or if that title really belongs to Pacino. I always swear that I'm gonna add up minutes of screentime, but I can never do it because I get too involved. To me, it feels more or less as if it's an ensemble piece. Brando disappears for awhile after he's shot, but so does Pacino immediately after he flees the country. (It's worth pointing out that even the greatest films ever made have flaws. As I feel the Paris flashbacks in my beloved Casablanca come off as hokey, Michael's Sicily scenes and sudden marriage may be The Godfather's Achilles' heel.) What I know for certain is that both actors deliver great performances. You see very little of the Brando silliness that sometimes pop up with the most obvious example being when singer Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) seeks his help at the wedding at the don unmercifully mocks him as Fontane practically cries acting what he can do to get that movie part. Corleone shakes him vigorously and shouts, "You can act like a man!" He then slaps him and ridicules him further. "What's the matter with you? Is this what you've become, a Hollywood finocchio who cries like a woman?" Then the funny Brando comes out as he does a little girl voice, "'Oh, what do I do? What do I do?' What is that nonsense? Ridiculous!" You spot Tom Hagen laughing in the background, but part of me suspects that really was Duvall trying not to crack up. Other than that, Brando plays things remarkably straight and truthfully as when he calls in the favor the undertaker Bonasera owes him to clean up Sonny for his funeral. "Look how they massacred my boy," he cries.Looking at the young Pacino engenders the same kind of sadness that recent appearances by Robert De Niro do — did their love of the craft give way totally to monetary concerns? Pacino actually hasn't been quite as bad as De Niro, but to see his Michael, when Pacino knew the word subtlety…sigh. My God — I didn't see it, but what in the hell was he doing playing himself opposite Adam Sandler in Jack and Jill? To Pacino's credit, at least I can believe he appears in that kind of shit so he can keep returning to the stage. Michael Corleone's arc allows viewers to see a master class in screen acting over the first two movies. You can accomplish this with the first film alone, watching as he slinks further into the darkness. Another thing I've always loved that I'm grateful I found a YouTube clip to use is the strut Michael develops once he's completed his turn and just watched Carlo ride off to his demise. What an evocative, physical symbol of a man's change.

At the beginning of this post (I apologize that happened so long ago) I promised that I would be discussing things new to me about The Godfather. That time has arrived. In case it's slipped your mind, what I began this piece by saying was that sometimes you know a movie so well that when you actually watch it closely and purposefully, you'll notice things or have ideas that haven't occurred to you before.

Don't get me wrong. The reason I've spent so much space talking about the acting, writing and directing after the setup before I got to the crux of this assessment was meant to reassure those out there that The Godfather remains one of my favorite films of all time before I described a shift in my outlook on it. Back in the previous posts, as I detailed all the chaos endured to get the film made, I mentioned briefly how Paramount pursued some of the top directors at that time but all turned the project down, citing a fear of glamorizing or glorifying the Mafia. That's a criticism that gets hurled at most mob-related entertainments. Some said that about Martin Scorsese's Goodfellas. Even larger numbers lodged that complaint against The Sopranos. Reflexively, I've always responded that those accusations were nothing but a load of crap — and they are when it comes to Goodfellas and The Sopranos, which don't try to hide the fact that these people steal, kill and basically don't contribute to a civil society. Watching The Godfather this time, a light suddenly illuminated its depiction of the Corleones as whitewashed, to say the least. It starts from the very first scene when the undertaker Bonasera asks the don to kill the men who attacked his daughter, but Vito refuses. When Bonasera leaves, Vito even says to Tom Hagen, "We're not murderers, no matter what he thinks." Except mobsters are murderers. That line only marks the first example of the film turning the criminal family into reputable heroes. These photos are just for contrast. At left, we have Corleone family soldier Luca Brasi (Lenny Montana) being strangled in an ambush set up by the "bad gangsters"

Sollozzo (Al Lettieri) and Bruno Tattaglia (Tony Giorgio). In the photo on the right, the star of The Sopranos, James Gandolfini as Tony, personally throttles Fabian Petrulio (Tony Ray Rossi), who used to be a gangster but became a "rat" when he testified for the feds and went into the Witness Protection Program. This took place in "College," the heralded fifth episode of the series. They wasted no time showing that Tony would commit a hands-on murder. Examine Goodfellas in comparison to The Godfather. Goodfellas came from Nicholas Pileggi's well-researched nonfiction book Wiseguys. While Mario Puzo's novel played the guessing game of "Who could this character be based on?", Puzo never asserted it to be anything but a fictionalized portrait and the film version watered down the Corleones even further. Coppola openly admits he wanted to use the story to be less about organized crime but a comment on American capitalism as well as being about a family in the generic sense. While corporate businessmen may not call their mistresses goomahs, they have them. You'd have to watch very closely to notice that a wife exists that Sonny cheats on (You never see a ring on his finger). They show him having a vigorous sex life, but certainly downplay that it's an adulterous one. We get a few brief shots of his spouse and one comment from his dad when Sonny comes into his father's office following a sexual encounter and his dad talks with Fontane. When Vito sees Sonny enter, he asks the singer but looks pointedly at his son, "Are you good to your family?" In Goodfellas, the girlfriends existed as part of the gangster lifestyle with, separate nights set aside for them at the Copacabana. By the era of The Sopranos, the wives know they exist and accept them somewhat as long as they keep the benefits of their lifestyle.

Sollozzo (Al Lettieri) and Bruno Tattaglia (Tony Giorgio). In the photo on the right, the star of The Sopranos, James Gandolfini as Tony, personally throttles Fabian Petrulio (Tony Ray Rossi), who used to be a gangster but became a "rat" when he testified for the feds and went into the Witness Protection Program. This took place in "College," the heralded fifth episode of the series. They wasted no time showing that Tony would commit a hands-on murder. Examine Goodfellas in comparison to The Godfather. Goodfellas came from Nicholas Pileggi's well-researched nonfiction book Wiseguys. While Mario Puzo's novel played the guessing game of "Who could this character be based on?", Puzo never asserted it to be anything but a fictionalized portrait and the film version watered down the Corleones even further. Coppola openly admits he wanted to use the story to be less about organized crime but a comment on American capitalism as well as being about a family in the generic sense. While corporate businessmen may not call their mistresses goomahs, they have them. You'd have to watch very closely to notice that a wife exists that Sonny cheats on (You never see a ring on his finger). They show him having a vigorous sex life, but certainly downplay that it's an adulterous one. We get a few brief shots of his spouse and one comment from his dad when Sonny comes into his father's office following a sexual encounter and his dad talks with Fontane. When Vito sees Sonny enter, he asks the singer but looks pointedly at his son, "Are you good to your family?" In Goodfellas, the girlfriends existed as part of the gangster lifestyle with, separate nights set aside for them at the Copacabana. By the era of The Sopranos, the wives know they exist and accept them somewhat as long as they keep the benefits of their lifestyle.I don't know how this could come as such a shock to me now, having seen The Godfather so many times over so many years other than my love for Goodfellas superseding it and subliminally planting seeds in my mind which The Sopranos watered, allowing the realization to blossom. The recent Blu-ray release The Godfather Coppola Restoration includes a special feature in which Sopranos creator David Chase says he intended his series to be about the first generation of gangsters actually influenced by Coppola's film. I'm sure that's true (the characters made lots of references to the trilogy), but their lives more closely resemble those of the real gangsters in Henry Hill's universe in Goodfellas than they do the Corleones, with their huge family compound. Even Paulie (Paul Sorvino), the boss in Goodfellas, lived a

more middle-class-looking lifestyle, at least in terms of appearance. The fictional Tony got to move into upper middle-class suburbs, but those who worked for him lived much more meagerly. Hell, when you compare them, the brief shot in The Godfather of the home where Clemenza lives looks much nicer than the Belleville, N.J. residence of Corrado Soprano (Dominic Chianese). While not a gangster, even Walter White (Bryan Cranston) lived in a much nicer house when his salary came solely from teaching chemistry than Uncle Junior's or most of Tony's crew's places did, but the cost-of-living in Albuquerque probably is a lot less expensive than New Jersey. What's more relevant than the living arrangements of the various fictional and nonfictional criminals comes from my recognition of the unwillingness to show the true nature of the Corleone family unlike Scorsese did with the criminals in Goodfellas, Chase showed with his characters on The Sopranos and Vince Gilligan does on Breaking Bad charting, as he's said often, "Mr. Chips turning into Scarface." In Goodfellas and the TV shows, you see the innocent who pay the price for their crimes. In The Godfather, we don't see a single instance of how the Corleones conduct their criminal enterprises. The Godfather board game that I mentioned having in the first post, "America's first family," explicitly references bookmaking, extortion, bootlegging, loan sharking and hijacking though those activities never cross the lips of the Corleones or anyone who works for them (though it's doubtful that by 1945, bootlegging draws much revenue for the New York-based family). Are we to presume the Corleones actually built the mansion with profits from selling Genco Olive Oil?

more middle-class-looking lifestyle, at least in terms of appearance. The fictional Tony got to move into upper middle-class suburbs, but those who worked for him lived much more meagerly. Hell, when you compare them, the brief shot in The Godfather of the home where Clemenza lives looks much nicer than the Belleville, N.J. residence of Corrado Soprano (Dominic Chianese). While not a gangster, even Walter White (Bryan Cranston) lived in a much nicer house when his salary came solely from teaching chemistry than Uncle Junior's or most of Tony's crew's places did, but the cost-of-living in Albuquerque probably is a lot less expensive than New Jersey. What's more relevant than the living arrangements of the various fictional and nonfictional criminals comes from my recognition of the unwillingness to show the true nature of the Corleone family unlike Scorsese did with the criminals in Goodfellas, Chase showed with his characters on The Sopranos and Vince Gilligan does on Breaking Bad charting, as he's said often, "Mr. Chips turning into Scarface." In Goodfellas and the TV shows, you see the innocent who pay the price for their crimes. In The Godfather, we don't see a single instance of how the Corleones conduct their criminal enterprises. The Godfather board game that I mentioned having in the first post, "America's first family," explicitly references bookmaking, extortion, bootlegging, loan sharking and hijacking though those activities never cross the lips of the Corleones or anyone who works for them (though it's doubtful that by 1945, bootlegging draws much revenue for the New York-based family). Are we to presume the Corleones actually built the mansion with profits from selling Genco Olive Oil?you got whacked. Everybody knew the rules. But sometimes, even if people didn't get out of line, they got whacked.

I mean, hits just became a habit for some of the guys. Guys would get into arguments over nothing and before you knew it,

one of them was dead. And they were shooting each other all the time. Shooting people was a normal thing. It was no big deal."

— Ray Liotta as Henry Hill in Goodfellas

Where The Godfather goes to the greatest length to make the Corleones "good gangsters" can be viewed by the people they do kill. Every single one of them has wronged them first and/or been shown as someone worthy of elimination. You never see any incident such as in Goodfellas where psycho Tommy (Joe Pesci) kills the waiter Spider (Michael Imperioli) because he told him to "go fuck himself" (since Spider justifiably nurses a grudge after Tommy shot him in the foot before for not serving him a drink fast enough). You don't see

anything like on The Sopranos where a waiter follows Paulie (Tony Sirico) and Christopher (Imperioli again) out to the parking lot to ask why he didn't get a tip and they smash him in the head, causing convulsions and then shoot him to finish him off. Don Vito plays the peacemaker, despite being nearly killed and losing a son. The movie perpetuates the myth that the American Mafia likes to perpetuate that they stayed hands off narcotics trafficking (even Paulie Cicero in Goodfellas, based on the real-life Paulie Vario, peddles that line though, like the fictional Corleone, it isn't so much a moral objection as a fear of losing friends in high positions). It sounds particularly ridiculous since Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky already had started dealing heroin in the 1920s, something being depicted in the TV series Boardwalk Empire which may be set prior to the time period of The Godfather but by far pays the most obvious homages to the movie. This sudden realization raises questions in my mind: Does it matter? Should it matter? If The Godfather glamorizes gangsters, does that mean I should consider it a lesser movie? My answer has to be no to all of the above. It doesn't change its artistry and I already loved Goodfellas more anyway (and it only glamorizes their food). How can I really penalize a fictional film for not being more truthful? In the wake of The Godfather, did organized crime grow and get a bunch of new recruits eager to join mob ranks? Hardly. It's just interesting that it took me this long to notice this, but the film hasn't changed, I have.

anything like on The Sopranos where a waiter follows Paulie (Tony Sirico) and Christopher (Imperioli again) out to the parking lot to ask why he didn't get a tip and they smash him in the head, causing convulsions and then shoot him to finish him off. Don Vito plays the peacemaker, despite being nearly killed and losing a son. The movie perpetuates the myth that the American Mafia likes to perpetuate that they stayed hands off narcotics trafficking (even Paulie Cicero in Goodfellas, based on the real-life Paulie Vario, peddles that line though, like the fictional Corleone, it isn't so much a moral objection as a fear of losing friends in high positions). It sounds particularly ridiculous since Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky already had started dealing heroin in the 1920s, something being depicted in the TV series Boardwalk Empire which may be set prior to the time period of The Godfather but by far pays the most obvious homages to the movie. This sudden realization raises questions in my mind: Does it matter? Should it matter? If The Godfather glamorizes gangsters, does that mean I should consider it a lesser movie? My answer has to be no to all of the above. It doesn't change its artistry and I already loved Goodfellas more anyway (and it only glamorizes their food). How can I really penalize a fictional film for not being more truthful? In the wake of The Godfather, did organized crime grow and get a bunch of new recruits eager to join mob ranks? Hardly. It's just interesting that it took me this long to notice this, but the film hasn't changed, I have.Besides, it's a damn great movie that gets referenced constantly. Chase should make something for the Blu-ray given the amount of times The Sopranos references Coppola's films. They did it so many times, I couldn't even begin to recall them all. I remember my personal favorite: Paulie Walnut's car horn which plays The Godfather theme instead of beeping. As I mentioned, Boardwalk Empire might take place in the 1920s, but it seems to me to pay the most homages even if they can't be specific. Look at the character of Nucky Thompson's brother Eli (Shea Whigham) and tell me he doesn't have Fredo written all over him. In the final episode of the second season, they did an explicit reference with their version of the baptism scene with prosecutor Esther Randolph (Julianne Nicholson) preparing her opening statement as Nucky (Steve Buscemi) and Margaret (Kelly Macdonald) get married and Jimmy and Richard (Michael Pitt, Jack Huston) take care of one of Nucky's enemies.

Most of The Sopranos' references tended to be verbal, but they did do a visual one that I loved in the second episode of the third season "Proshai, Livushka" dealing with the death of the incomparable character of Tony's mom Livia Soprano (the late, great Nancy Marchand). The image below on the left comes from The Godfather when Don Vito and Tom visit Bonasera about fixing up Sonny for his funeral. Below on the right, Tony and his sisters Barbara and Janice (Danielle Di Vecchio, Aida Turturro) go to Coscarelli's to discuss arrangement for Livia, who didn't even want a service.

The fact remains, no matter the dubious way they tried to steer audience sympathy to the Corleones without acknowledging the truth of their dark dealings, The Godfather always will be a damn well-made piece of motion picture art. My philosophy always has been to judge movies on their artistic and entertainment grounds and to try to forego extraneous concerns. I've managed to do that for this long with The Godfather. I'm not changing my mind now, especially since, when it comes to film criticism, I'm about as far from a moralist as you'll find. Besides, we started these posts with that brilliant opening. "I believe in America." You think I wouldn't close with one of the all-time best endings in cinema?

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Boardwalk Empire, Brando, Breaking Bad, Buscemi, Caan, Coppola, De Niro, Diane Keaton, Duvall, Hackman, Liotta, Lumet, Pacino, Pesci, Scorsese, Streep, The Sopranos, Towne, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

Boardwalk Empire No. 24: To the Lost Part I

By Edward Copeland

"I'm not looking for forgiveness." That's what Nucky says before he commits the shocking act toward the end of the second season finale. I've read an interview Hitfix's Alan Sepinwall did with creator/executive producer Terence Winter and, from a storytelling perspective, I can buy Winter's argument for why what happened had to happen, but as good as the past few episodes of Boardwalk Empire have been, they played liked the end to a series instead of the end to a season. A good friend of mine, who always has been very critical of the show, complained that it never seemed to find its voice. I disagreed because what I was watching, I mostly enjoyed. Now, I think he may have been right. Where does it go from here? What mystifies me is how the finale lifted a shroud that must have been cloaking my critical thinking all season long. I've loved most of the show, with far more positive things to say than negative, and the finale followed a run of four episodes where each installment built on the momentum and quality of the one that preceded it. Then in the finale, which was well made — can't argue that it wasn't — Boardwalk Empire rushed to resolve plot strands and did it so haphazardly and with ham-handedness so it could set up its surprise that upends the entire series that it also managed to undermine the season as a whole, revealing cracks and fissures that weren't apparent before. Where does Boardwalk Empire go in season three? What can be one of the most entertaining and enriching hours of television appears after its second season finale, to me at least, to be an unsalvageable mess and part of that feeling stems from that simple line of dialogue: "I'm not looking for forgiveness." This comes with the second week in a row when Nucky tells a character, "Then you never knew me at all." He may have been addressing Margaret and Jimmy onscreen, but he might as well have been speaking to the faithful viewer because the line that he's "not looking for forgiveness" completely contradicts what we've known and seen about Nucky Thompson in the preceding 23 episodes, or at least reveals a completely inconsistent character. That got me thinking about how many of the show's characters behave inconsistently — doing things because the plot requires them to at that moment not because it's in their nature. Last week, I joked that next season's cast could end up having more turnover than Law & Order did in all of its 20 seasons combined, but now that seems neither funny nor out of the realm of possibility. As a result, I feel I need to split this finale recap in half and do a separate season in review just to get these thoughts started out there.

The series’ usually most reliable team handled "To the Lost," with Winter doing the writing and the show's main director and another of its quarter-million executive producers, Tim Van Patten, directing. Things get off to an exciting start as two masked men in a beat-up vehicle who obviously are Jimmy and Richard drive up a country where some Ku Klux Klan members have gathered. When they get out bearing weapons, one of the Klansmen clad in his robes but not his hood (Tim House) asks, “Who are you two jokers?” Jimmy responds by shooting the racist son-of-a-bitch. The other white bigots, if they hadn’t noticed they had visitors, know it now. “Good — we have your attention. Names and addresses of the three men who shot up Chalky White’s warehouse,” Jimmy demands. When none of the organized hatemongers seem forthcoming, Richard steps forward with his shotgun and unloads into another robe-wearing asshole. “Five seconds gentlemen,” Richard croaks. “There’s Herb Crocker — he was one. And Dick Heatherton,” a man wearing normal clothes (Denny Dale Bess) tells them. Behind the line of vehicles, Jimmy and Richard don’t notice someone wearing Klan robes and another man high-tailing it up the road. Jimmy steps closer to the only man talking, keeping his gun aimed straight at his face. “Who else?” A Klansman kneeling on the ground, blood splattered all over his robe, tries to run for it. Jimmy jumps him and the screen goes dark.

In Philadelphia, Manny Horvitz certainly has looked better. He hasn’t shaved, has a cigarette butt dangling from his lips and appears to be in a dark basement somewhere, speaking in a hoarse whisper. “Everyone’s a crook. Little crooks take from who they can. Nobodies stealin’ from nobodies. Then the middle player — how many nobodies does it take to feed him? Seven? Ten? The middle man is always

hungry, always worried. From the middle, it’s always easier to fall down than to climb up. But the big crooks — the macher — the big crooks does nothing," Horvitz rambles on about how the biggest crooks take all the perks while the underlings do all the work and we see that he isn't talking to himself but that his meandering address is being given to Mickey, Nucky and Owen. Manny begins to reminisce about his childhood in Odessa in the Ukraine, telling how sometimes he forgets what's going on and imagines that he's 12 again with his whole life ahead of him. "But then I realize I'm in America — that world is gone. You have to make the best of it," he declares. "I understand. We've both had a rough time of it recently," Nucky says just so another voice can be heard. "I sketched it out for him," Mickey tells Manny while fanning himself with his hat, apparently because the basement isn't particularly cool. I think this every time I see Mickey: How the hell has he survived? This is a major part of the inconsistency in Nucky's "I'm not seeking forgiveness" line. Nucky knows that Doyle was involved in the plot against him (He did have Owen blow up his warehouse after all). Mickey screwed him over before with the D'Alessio brothers, but he let him get away with it. Jimmy means so much more to Nucky than Mickey Doyle ever would and when Jimmy attempts genuine reconciliation, he gets no forgiveness but Mickey, who betrays every person he works with, has turned on Nucky twice (and the D'Alessio plot also involved an

hungry, always worried. From the middle, it’s always easier to fall down than to climb up. But the big crooks — the macher — the big crooks does nothing," Horvitz rambles on about how the biggest crooks take all the perks while the underlings do all the work and we see that he isn't talking to himself but that his meandering address is being given to Mickey, Nucky and Owen. Manny begins to reminisce about his childhood in Odessa in the Ukraine, telling how sometimes he forgets what's going on and imagines that he's 12 again with his whole life ahead of him. "But then I realize I'm in America — that world is gone. You have to make the best of it," he declares. "I understand. We've both had a rough time of it recently," Nucky says just so another voice can be heard. "I sketched it out for him," Mickey tells Manny while fanning himself with his hat, apparently because the basement isn't particularly cool. I think this every time I see Mickey: How the hell has he survived? This is a major part of the inconsistency in Nucky's "I'm not seeking forgiveness" line. Nucky knows that Doyle was involved in the plot against him (He did have Owen blow up his warehouse after all). Mickey screwed him over before with the D'Alessio brothers, but he let him get away with it. Jimmy means so much more to Nucky than Mickey Doyle ever would and when Jimmy attempts genuine reconciliation, he gets no forgiveness but Mickey, who betrays every person he works with, has turned on Nucky twice (and the D'Alessio plot also involved an assassination attempt) yet Thompson lets Mickey live but feels his surrogate son must die? "I must stay away from home for the safety of my family. Close my shop. I'm living like a beggar," Manny explains. "Bit of bad luck — happen to anyone," Sleater comments from the corner. "My bad luck has a name — Waxey Gordon," Manny says. "Let me stop you right there. Whatever your problems, Waxey Gordon is a business partner of mine," Nucky informs Horvitz. "Are you sure about this, Mr. Thompson?" Manny asks as he takes another drink. "Do you know something I don't?" Nucky inquires. "The question answers itself," Manny responds cryptically. "Nucky's a busy fellow, Manny," Mickey says when Nucky gives him a look. "And I have nothing better to do?" Horvitz responds. "You're hiding in the basement of a synagogue. Don't waste his time," Mickey tells him. "Your partner Waxey Gordon is in business with James Darmody. Would you say we have something in common?" Manny asks Nucky. "We might," Nucky admits. "Then let us help each other. You give me Waxey, I give you Darmody and we make business together," Horvitz proposes. "You'll give him to me? In all honesty, you don't look to be in a condition to do anything," Nucky says. "Well, if the boychik's wife could still talk, she'd tell you otherwise," Manny drops into the talk as he pours another drink. Realizing that Manny just admitted to killing Angela pushes Nucky back on his heels somewhat — at least it appears to do so. "Maybe we have less in common than you think, Mr. Horvitz," Nucky changes his tune. "You said he was open to discussion," Manny addresses Mickey. "I said I'd broker the meet," Mickey replies. "So you're too big a crook to be seen with the likes of me," Horvitz accuses. "According to the federal prosecutor, yes, but I will consider your proposition" Nucky answers. Nucky leaves, saying that Mickey knows how to get in touch. "He's heading to jail and this is the look he gives me?" Manny growls to Mickey. "He ain't in jail yet," Mickey replies. "He would be nothing in Odessa," Manny declares as he takes another drink.

assassination attempt) yet Thompson lets Mickey live but feels his surrogate son must die? "I must stay away from home for the safety of my family. Close my shop. I'm living like a beggar," Manny explains. "Bit of bad luck — happen to anyone," Sleater comments from the corner. "My bad luck has a name — Waxey Gordon," Manny says. "Let me stop you right there. Whatever your problems, Waxey Gordon is a business partner of mine," Nucky informs Horvitz. "Are you sure about this, Mr. Thompson?" Manny asks as he takes another drink. "Do you know something I don't?" Nucky inquires. "The question answers itself," Manny responds cryptically. "Nucky's a busy fellow, Manny," Mickey says when Nucky gives him a look. "And I have nothing better to do?" Horvitz responds. "You're hiding in the basement of a synagogue. Don't waste his time," Mickey tells him. "Your partner Waxey Gordon is in business with James Darmody. Would you say we have something in common?" Manny asks Nucky. "We might," Nucky admits. "Then let us help each other. You give me Waxey, I give you Darmody and we make business together," Horvitz proposes. "You'll give him to me? In all honesty, you don't look to be in a condition to do anything," Nucky says. "Well, if the boychik's wife could still talk, she'd tell you otherwise," Manny drops into the talk as he pours another drink. Realizing that Manny just admitted to killing Angela pushes Nucky back on his heels somewhat — at least it appears to do so. "Maybe we have less in common than you think, Mr. Horvitz," Nucky changes his tune. "You said he was open to discussion," Manny addresses Mickey. "I said I'd broker the meet," Mickey replies. "So you're too big a crook to be seen with the likes of me," Horvitz accuses. "According to the federal prosecutor, yes, but I will consider your proposition" Nucky answers. Nucky leaves, saying that Mickey knows how to get in touch. "He's heading to jail and this is the look he gives me?" Manny growls to Mickey. "He ain't in jail yet," Mickey replies. "He would be nothing in Odessa," Manny declares as he takes another drink.Three of Chalky's men stand armed outside a warehouse as some vehicles approach. One of his workers (Donte Bonner) inside watches through slats in the garage door and tells Chalky and Dunn, "They're here." With absolute calm, Chalky says, "Open it on up." The worker slides open the doors and Jimmy drives his beat-up vehicle inside while Richard stays in another with his gun ready. Purnsley snaps his fingers as Jimmy hands Chalky a bag. "There's twenty thousand in cash. Five thousand for the families of each victim," Jimmy says. "I only asked for three," Chalky replies. "I know you did," Jimmy responds. He then walks around to the back of the flatbed and pulls the canvas

off three bound, gagged and whimpering men. "The three pieces of shit who shot this place up," Jimmy informs Chalky. "You sure about that?" Chalky asks. "Ask them yourself," Jimmy suggests. "That gonna be my pleasure," Purnsley salivates as he toys with a switchblade. "Governor office dropped my case. You can tell your daddy I'll call off the strike," Chalky declares. "I will. You can do something for me — tell Nucky I want to talk," Jimmy says. Chalky nods in the affirmative. Jimmy leaves the warehouse and Chalky turns his attention to the tied-up Klansmen. "Welcome back fellas," Chalky grins. The Klansmen all moan, "No" as they get pulled off the truck and Chalky and his men proceed to beat on them. Jimmy gets in the car with Richard. "Whatever you do to try to change things, you know he'll never forgive you," Richard tells him. "Let's go to Childs. I feel like a steak," Jimmy says. Would there not be the possibility that Chalky will be pissed off when he finds out that Nucky executed Jimmy? He delivered more money to the families than Chalky asked for and after months of Nucky putting him off, Jimmy actually took it upon himself to off some Klansmen and bring the guilty parties to him, something that Thompson would never have done. The businessmen and the deservedly dead Commodore might have mocked him for urging them to settle the strike and be fair to their workers, but he actually was setting out to be a fairer leader. When Mayor Bader said at the meeting that he thought Jimmy had the right idea, he might have been telling the truth if you read up on what the real Edward Bader was like.

off three bound, gagged and whimpering men. "The three pieces of shit who shot this place up," Jimmy informs Chalky. "You sure about that?" Chalky asks. "Ask them yourself," Jimmy suggests. "That gonna be my pleasure," Purnsley salivates as he toys with a switchblade. "Governor office dropped my case. You can tell your daddy I'll call off the strike," Chalky declares. "I will. You can do something for me — tell Nucky I want to talk," Jimmy says. Chalky nods in the affirmative. Jimmy leaves the warehouse and Chalky turns his attention to the tied-up Klansmen. "Welcome back fellas," Chalky grins. The Klansmen all moan, "No" as they get pulled off the truck and Chalky and his men proceed to beat on them. Jimmy gets in the car with Richard. "Whatever you do to try to change things, you know he'll never forgive you," Richard tells him. "Let's go to Childs. I feel like a steak," Jimmy says. Would there not be the possibility that Chalky will be pissed off when he finds out that Nucky executed Jimmy? He delivered more money to the families than Chalky asked for and after months of Nucky putting him off, Jimmy actually took it upon himself to off some Klansmen and bring the guilty parties to him, something that Thompson would never have done. The businessmen and the deservedly dead Commodore might have mocked him for urging them to settle the strike and be fair to their workers, but he actually was setting out to be a fairer leader. When Mayor Bader said at the meeting that he thought Jimmy had the right idea, he might have been telling the truth if you read up on what the real Edward Bader was like.Lillian and Katy help Emily practice walking by trying to lure her a few steps to get to her doll Beatrice when Nucky and Owen return from Philadelphia. Nucky asks where Margaret is and Lillian tells him she left about 20 minutes ago, but didn't say where she was going. Sleater greets everyone, but gives Katy a noticeably cold shoulder.

Margaret's current location happens to be the Post Office where she's about to speak with Esther Randolph — but she didn't come alone. Father Brennan has accompanied her. "She brings a priest? I'm surprised she doesn't have an infant suckling at her breast," Dick Halsey, the clerk, comments. "Bring me back a shaved cherry ice. I'm boiling," Randolph tells him as she enters and introduces herself. "This is Father Brennan," Margaret says. "I'm here for moral support," the priest tells the prosecutor. "I don't think I'll need it," Randolph replies. "She understood that, Father," Margaret keys Brennan in on Esther's wit when the priest clarifies that he meant he's there to support Mrs. Schroeder. "Mrs. Schroeder has left her children — including her sickly daughter — to be here today," Brennan informs Randolph. "What's wrong with her?" she inquires. "Polio," Margaret answers. "I'm terribly sorry," Esther says. "Mrs. Schroeder is a widow and a devoted mother. She is active in the church and ignorant of any charges in this case," Brennan preaches on Margaret's behalf. "I didn't realize they taught law in the seminary. Perhaps we should let Mrs. Schroeder speak for herself," Randolph suggests. "There's nothing she — " Margaret cuts Brennan off. "I'd like to speak with Miss Randolph alone," she says. "I'm not sure — Margaret shuts the priest down in midsentence again. "Thank you, father," Margaret tells him, giving him the hint to take a hike. "Well, I suppose I'll buy some stamps,"

Father Brennan announces as he leaves. When we first heard mention of Father Brennan, it was in the season's first episode when Sister Bernice informed Margaret that Teddy didn't get expelled over the matches because Brennan was a good friend of Nucky's and intervened. Of late, Nucky hasn't spoken kindly of the priest, but could he have planted him there to keep a watch on what Margaret was saying or is this another example of characters being inconsistent? "Is it difficult to become a lawyer?" Margaret asks Randolph. "Not if you set your mind to it — and don't take no for an answer," she replies. "I doubt it was that simple," Margaret declares. "You're right. I started as a public defender. As you might imagine, my only clients were women," Randolph shares. "What kind of women?" she asks the prosecutor. "The kind who don't have any other choice," Randolph replies. "Are you saying I did?" Margaret asks her. "Why don't you tell me? You cleared the room," Randolph suggests. "My husband beat me. He beat our children. He was a drunkard and a philanderer," Margaret tells her. "And now you've moved up in the world," Randolph states. "Do you hate Mr. Thompson?" Margaret inquires, a curious and lilting tone in her voice. "No, I rather like him. Not that it matters. Do you hate him?" Esther parries. Margaret doesn't answer immediately. "Your feelings are complicated," Randolph guesses. "The truth is complicated as well," Margaret replies. "Then I'd be very interested in hearing what you have to say," Randolph tells her. "Would I have to appear in court?" Margaret inquires. "I'll compel you to testify whether you cooperate with me or not. I can paint you either way on that witness stand. It's really up to you: the helpless widow, unwittingly drawn in by her husband's killer or the shameless gold-digger seduced by money," Randolph lays it out for Margaret. "Does it matter to you that

Father Brennan announces as he leaves. When we first heard mention of Father Brennan, it was in the season's first episode when Sister Bernice informed Margaret that Teddy didn't get expelled over the matches because Brennan was a good friend of Nucky's and intervened. Of late, Nucky hasn't spoken kindly of the priest, but could he have planted him there to keep a watch on what Margaret was saying or is this another example of characters being inconsistent? "Is it difficult to become a lawyer?" Margaret asks Randolph. "Not if you set your mind to it — and don't take no for an answer," she replies. "I doubt it was that simple," Margaret declares. "You're right. I started as a public defender. As you might imagine, my only clients were women," Randolph shares. "What kind of women?" she asks the prosecutor. "The kind who don't have any other choice," Randolph replies. "Are you saying I did?" Margaret asks her. "Why don't you tell me? You cleared the room," Randolph suggests. "My husband beat me. He beat our children. He was a drunkard and a philanderer," Margaret tells her. "And now you've moved up in the world," Randolph states. "Do you hate Mr. Thompson?" Margaret inquires, a curious and lilting tone in her voice. "No, I rather like him. Not that it matters. Do you hate him?" Esther parries. Margaret doesn't answer immediately. "Your feelings are complicated," Randolph guesses. "The truth is complicated as well," Margaret replies. "Then I'd be very interested in hearing what you have to say," Randolph tells her. "Would I have to appear in court?" Margaret inquires. "I'll compel you to testify whether you cooperate with me or not. I can paint you either way on that witness stand. It's really up to you: the helpless widow, unwittingly drawn in by her husband's killer or the shameless gold-digger seduced by money," Randolph lays it out for Margaret. "Does it matter to you that neither one of those is true?" Margaret asks. "It matters that Enoch Thompson goes to jail," Randolph suddenly shouts. Esther lowers her voice and leans across the desk. "What has he given you besides money?" she wants to know. The camera, already close on Margaret, zooms in tighter. "He's never been cruel to me," she answers. "He's been plenty cruel to others," Esther says, almost in a whisper. "I've never seen it," Margaret responds. "But you know it anyway," Randolph accuses Margaret. "I have children," she offers as a defense for willful blindness. "And does their well-being trump everyone else's? The victims' as well as the criminals'?" Esther raises the questioning, hitting Margaret on her already overactive guilt complex. "If you had your own, you'd never ask," Margaret declares. "If I had my own, I couldn't bear knowing their comfort was bought with the blood of others because sooner or later they'll find out themselves and that won't be a happy day," Randolph responds. "If I did what you ask, what becomes of me?" Margaret inquires. "You'd never have to see him again. Set yourself free, Mrs. Schroeder. You'll be amazed how much better you feel," Randolph pledges. I'm probably alone in this, but this might be favorite scene of this episode for a couple of reasons. First, it's the only time in the show's history that I can recall that they had a scene predominantly between two intelligent women. Second, it's another example of one of my favorite aspects of the show — riveting dialogue scenes they let go on, in this case, for nearly four minutes.

neither one of those is true?" Margaret asks. "It matters that Enoch Thompson goes to jail," Randolph suddenly shouts. Esther lowers her voice and leans across the desk. "What has he given you besides money?" she wants to know. The camera, already close on Margaret, zooms in tighter. "He's never been cruel to me," she answers. "He's been plenty cruel to others," Esther says, almost in a whisper. "I've never seen it," Margaret responds. "But you know it anyway," Randolph accuses Margaret. "I have children," she offers as a defense for willful blindness. "And does their well-being trump everyone else's? The victims' as well as the criminals'?" Esther raises the questioning, hitting Margaret on her already overactive guilt complex. "If you had your own, you'd never ask," Margaret declares. "If I had my own, I couldn't bear knowing their comfort was bought with the blood of others because sooner or later they'll find out themselves and that won't be a happy day," Randolph responds. "If I did what you ask, what becomes of me?" Margaret inquires. "You'd never have to see him again. Set yourself free, Mrs. Schroeder. You'll be amazed how much better you feel," Randolph pledges. I'm probably alone in this, but this might be favorite scene of this episode for a couple of reasons. First, it's the only time in the show's history that I can recall that they had a scene predominantly between two intelligent women. Second, it's another example of one of my favorite aspects of the show — riveting dialogue scenes they let go on, in this case, for nearly four minutes."How do you order someone to commit murder? It's fucking ludicrous," Nucky says to Fallon as they meet in his home office. "That's my position," Fallon agrees. "If I ordered them to step in front of a train, would they do that too?" Nucky asks rhetorically. "If they would, your troubles would be over," Fallon replies. "Goddammit! Eddie!" Nucky shouts. Kessler marches in. "Why is this bourbon empty?" Nucky asks. "Someone drank it," Eddie replies dryly. "You're cracking wise now?" Nucky responds. "I will refill it immediately," Eddie promises. "We should discuss your brother. If you could talk to him —" Nucky interrupts Fallon's suggestion. "He's in protective custody," Thompson informs his lawyer. "Get word through his lawyer. Make him some kind of offer," Fallon suggests. "Which is swell except we both know he's not the real problem," Nucky replies. "I suppose there is an elephant in the room," he says. "If you're referring to the woman who sleeps in the bed in which I'm no longer welcome, then yes, there certainly is," Nucky growls. "It's her testimony that'll sink ya," Fallon warns. Thompson insists that Margaret doesn't know anything but his attorney tells him that won't matter as far as the jury is concerned — her presence would be enough to corroborate Eli and Halloran's story. "The bottom line: If your lady friend testifies," Fallon doesn't finish his sentence, he just shakes his head. Eddie reappears to inform Nucky that Chalky is on the phone.

Jimmy sits by an open door in the attic of the beachhouse having a smoke when he hears a car approach. He looks down and spots Nucky's familiar blue Rolls-Royce. Nucky exits the back while Owen, who Jimmy has never met, gets out of the driver's seat and both approach the house. Uncertain of what to expect, Jimmy gets his gun ready and descends the stairs while Nucky and Owen already have entered the dwelling with Nucky calling out, "Hello." Jimmy comes into the dining room where they are and places his gun on the table. "The door was open. This is Owen Sleater," Nucky says. "You could wait outside. It's OK. I used to do your job," Jimmy tells Owen. "You're the reason I'm doin' it now," Sleater replies. Except when facing off against his old Irish foes, Owen always has been portrayed affably, even in fights. Now that they've decided to just toss out the political side of Nucky's life, I guess they decided that Sleater must be portrayed as rough, tough and nasty at all times now, whether he's in a scene with Jimmy or the young maid who was boffing. Of course, last week he still was the old Owen trying to come on to Margaret. Nucky nods to Owen that he can leave and he does. Nucky offers Jimmy his condolences about Angela. "Manny Horvitz. Philadelphia," Jimmy informs Nucky. "Never heard of him," Nucky lies. "He used to work for Waxey Gordon. He came for me. Found her instead," Jimmy explains as he pours drinks. "If I hear anything, I'll let you know," Nucky promises before passing up a drink. Jimmy spills part of the booze onto the floor. "To the lost," he toasts alone. When he finishes the drink, he takes a seat. "My father's dead. I should have killed him the moment he suggested betraying you. I thought about it since I was a kid — killing him. I don't know what stopped me," he confesses to

Nucky. "He was your father, James. Nothing looms larger," Nucky tells him. "Last year when he was sick, I went to see him. He looked — pathetic. He was scared and he was trembling. I put my hand on his chest. I looked into his eyes and he said, 'You're a good son.' Knocked the wind out of me. I know there's nothing I can say, Nuck. Maybe there's something I can do," Jimmy offers. "For me? How about telling the truth?" Nucky suggests, a glimmer of spite showing. "I was angry," Jimmy admits. "About what?" Nucky asks, not hiding his anger anymore. "Who I was. Who you are. What I'd been through — over there. The shooting — I never meant for that to happen," Jimmy admits. "Then why did it?" Nucky demands to know. If you really want to get down to it, it's because your driver/bodyguard was busy killing somebody else and then boinking your common-law wife. Your brother, Capone, Lansky and Luciano liked the idea of capping you. Jimmy resisted. Mickey was there and didn't say yea or nay — but he didn't warn you either. Yet, you think that his involvement in TWO attempts on your life isn't enough to warrant his execution, but Jimmy's reluctant participation in one (which he subliminally warned you about) earned him a death sentence. Explain the consistency there. Jimmy gets up and looks out his favorite window at the beach and the ocean. Nucky tosses his hat on the table. "You said you wanted to talk, James, and suddenly you're very quiet," Nucky says. "It was Eli," he finally answers. "And you had nothing to do with it?" Thompson queries. "Let me make things right or as right as they can be. Just tell me how to help you." Sure, everything develops that Jimmy knows that he's going off to his doom, so why go to the trouble of trying to help Nucky first? Richard even tells him that he'll never forgive him. More unforgivingly, since Jimmy says all his goodbyes (They scripted and shot a final scene between him and Capone that they ended up not using), would he in good conscience not figure out a plan for Tommy that didn't result in leaving his rearing in his mother's hands?

Nucky. "He was your father, James. Nothing looms larger," Nucky tells him. "Last year when he was sick, I went to see him. He looked — pathetic. He was scared and he was trembling. I put my hand on his chest. I looked into his eyes and he said, 'You're a good son.' Knocked the wind out of me. I know there's nothing I can say, Nuck. Maybe there's something I can do," Jimmy offers. "For me? How about telling the truth?" Nucky suggests, a glimmer of spite showing. "I was angry," Jimmy admits. "About what?" Nucky asks, not hiding his anger anymore. "Who I was. Who you are. What I'd been through — over there. The shooting — I never meant for that to happen," Jimmy admits. "Then why did it?" Nucky demands to know. If you really want to get down to it, it's because your driver/bodyguard was busy killing somebody else and then boinking your common-law wife. Your brother, Capone, Lansky and Luciano liked the idea of capping you. Jimmy resisted. Mickey was there and didn't say yea or nay — but he didn't warn you either. Yet, you think that his involvement in TWO attempts on your life isn't enough to warrant his execution, but Jimmy's reluctant participation in one (which he subliminally warned you about) earned him a death sentence. Explain the consistency there. Jimmy gets up and looks out his favorite window at the beach and the ocean. Nucky tosses his hat on the table. "You said you wanted to talk, James, and suddenly you're very quiet," Nucky says. "It was Eli," he finally answers. "And you had nothing to do with it?" Thompson queries. "Let me make things right or as right as they can be. Just tell me how to help you." Sure, everything develops that Jimmy knows that he's going off to his doom, so why go to the trouble of trying to help Nucky first? Richard even tells him that he'll never forgive him. More unforgivingly, since Jimmy says all his goodbyes (They scripted and shot a final scene between him and Capone that they ended up not using), would he in good conscience not figure out a plan for Tommy that didn't result in leaving his rearing in his mother's hands? Margaret knits a scarf in the kitchen when Nucky asks to speak with her. "We were both raised Catholic, but I suppose it is fair to say that we have fundamental differences in our approach to religion," Nucky says. "You lost your faith," Margaret responds. "If there really is a God, would he have given me this mug? Look, maybe there is some being in the sky who sits in judgment. We'll all find out soon enough.

But my relationship to whatever that is, it doesn't need rules," Nucky explains. "So your version of God asks nothing?" Margaret comments. "It asks that I love my family. That I care for them and protect them. There is more God in the love I feel for you and those children than in all the churches in Rome. I know you're in pain and I know how hard it's been, but it will get better. We just need to stick together. I adore you, Margaret. I adore our family. My entire universe — it's within these walls. The rest can disappear," Nucky tells her. "And if I were to believe all that?" Margaret asks. "I need you to marry me," Nucky says. "Need?" she responds quizzically. "So you won't have to testify," he explains. "I want you to marry me." She looks at him suspiciously. "Then why did you not say that?" Nucky musters as sincere a look as possible. "Because I didn't want to insult you by pretending you wouldn't be saving my life. I've done bad things — horrible things — that I convinced myself were justified. I can see how wrong that was. God or no God — no one is sorrier than I am. I'm afraid, Margaret. I don't want to die or spend the rest of my life in jail. I'd never admit that to anyone but you," Nucky declares. Margaret gets up to turn off the whistling teapot. "You are always surprising. I will grant you that," she tells him before leaving the kitchen. The problem with Margaret and Nucky in a scene like this is that Steve Buscemi and Kelly Macdonald are such damn good actors, your instinct is to believe them, but are Nucky and Margaret as good as actors

But my relationship to whatever that is, it doesn't need rules," Nucky explains. "So your version of God asks nothing?" Margaret comments. "It asks that I love my family. That I care for them and protect them. There is more God in the love I feel for you and those children than in all the churches in Rome. I know you're in pain and I know how hard it's been, but it will get better. We just need to stick together. I adore you, Margaret. I adore our family. My entire universe — it's within these walls. The rest can disappear," Nucky tells her. "And if I were to believe all that?" Margaret asks. "I need you to marry me," Nucky says. "Need?" she responds quizzically. "So you won't have to testify," he explains. "I want you to marry me." She looks at him suspiciously. "Then why did you not say that?" Nucky musters as sincere a look as possible. "Because I didn't want to insult you by pretending you wouldn't be saving my life. I've done bad things — horrible things — that I convinced myself were justified. I can see how wrong that was. God or no God — no one is sorrier than I am. I'm afraid, Margaret. I don't want to die or spend the rest of my life in jail. I'd never admit that to anyone but you," Nucky declares. Margaret gets up to turn off the whistling teapot. "You are always surprising. I will grant you that," she tells him before leaving the kitchen. The problem with Margaret and Nucky in a scene like this is that Steve Buscemi and Kelly Macdonald are such damn good actors, your instinct is to believe them, but are Nucky and Margaret as good as actors as the performers playing them? Based on what's been going on, it's easy to doubt Nucky in this scene. However, earlier in the season when Nucky expressed his feelings for Margaret and her kids, he seemed heartfelt. Was Nucky lying then or is this just the new Nucky? Margaret — poor Margaret. The character somersaults they have put poor Kelly Macdonald through this season. At the beginning, she was played as a savvy co-conspirator for Nucky who could scheme rationally without reacting emotionally. They even set up the idea that she might have a mysterious past. Instead, we get the low point of the season in "Peg of Old" where we waste time with her visiting her siblings in Brooklyn and trying to play the headstrong lass against her stick-in-the-mud brother. The trip affected her so much that she rushes home and has sex with Owen. Then, Emily develops polio and she not only rediscovers her religion, she becomes convinced it's divine retribution and flies over the cuckoo's nest. Then, her guilt over how she and Nucky got together over her evil husband's corpse gets her to consider testifying against him, but instead she willingly weds him, knowing full well it's a ploy and he's lying to her and part of the old scheming Margaret comes back and signs over the deed to all that land that Nucky has tied up most of his money in to the church. I guess it's Margaret that Nucky never knew at all. Now what I want to know is this: If they're determined to turn Nucky into a full-blown badass gangster, if Margaret had refused to marry him and planned to testify instead, would he have had the balls to kill her? When he finds out about her and Owen (and you know that shoe will drop), will only Owen pay the price or would he be willing to kill a woman?

as the performers playing them? Based on what's been going on, it's easy to doubt Nucky in this scene. However, earlier in the season when Nucky expressed his feelings for Margaret and her kids, he seemed heartfelt. Was Nucky lying then or is this just the new Nucky? Margaret — poor Margaret. The character somersaults they have put poor Kelly Macdonald through this season. At the beginning, she was played as a savvy co-conspirator for Nucky who could scheme rationally without reacting emotionally. They even set up the idea that she might have a mysterious past. Instead, we get the low point of the season in "Peg of Old" where we waste time with her visiting her siblings in Brooklyn and trying to play the headstrong lass against her stick-in-the-mud brother. The trip affected her so much that she rushes home and has sex with Owen. Then, Emily develops polio and she not only rediscovers her religion, she becomes convinced it's divine retribution and flies over the cuckoo's nest. Then, her guilt over how she and Nucky got together over her evil husband's corpse gets her to consider testifying against him, but instead she willingly weds him, knowing full well it's a ploy and he's lying to her and part of the old scheming Margaret comes back and signs over the deed to all that land that Nucky has tied up most of his money in to the church. I guess it's Margaret that Nucky never knew at all. Now what I want to know is this: If they're determined to turn Nucky into a full-blown badass gangster, if Margaret had refused to marry him and planned to testify instead, would he have had the balls to kill her? When he finds out about her and Owen (and you know that shoe will drop), will only Owen pay the price or would he be willing to kill a woman?Tweet

Labels: Boardwalk Empire, Buscemi, HBO, Law and Order, TV Recap

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Boardwalk Empire No. 22: Georgia Peaches

By Edward Copeland

NOTE TO READERS: This Boardwalk Empire recap will be the final one I'll be able to post as the show finishes airing in the Eastern and Central time zones. Because of fears that spoilers will leak out, HBO isn't sending out advance screeners for the final two episodes of the second season airing Dec. 4 and 11. Because of my physical limitations and the extensive and detailed recaps I do, the recaps for those two episodes won't be completed until at least a day or two after those episodes premiere. Sorry for the inconvenience.

In a way, I'm surprised that they didn't hold back tonight's episode as well because it does have a shocker of an ending. I always put my spoiler warning up top, but I mean it this time. The only hint I'll give you in this introduction is that I've been surprised that we've gone through almost two seasons without a major character being killed (and by that, I mean someone listed in the opening credits). That changes tonight — and I certainly was surprised by who ends up wearing the toe tag, but it definitely promises some big changes for other characters and storylines in the future. Aside from that twist, tonight's episode, with a teleplay by Dave Flebotte, whose previous writing credits have been almost exclusively on comedic series such as Desperate Housewives, Will & Grace, 8 Simple Rules and Ellen as well as one of the weaker episodes of The Sopranos (season 4's "Calling All Cars"), does a great job on his first Boardwalk Empire script, building on the momentum that's been growing in the past two weeks. Though "Georgia Peaches" runs nearly 10 minutes longer than last week's installment, director Jeremy Podeswa moves it along at a pace that makes it seem that it ends even more quickly. Since Podeswa helmed this season's good "The Age of Reason" and last year's "Anastasia," which remains one of the best episodes in the series' history, he may be second only to Tim Van Patten in the show's regular stable of directors that you can depend on turning in a quality effort.

We ended last week's episode at an Irish port while a mournful tune in the style of traditional Irish music played. Tonight, we open at the Port of Hoboken and the song "Strut, Miss Lizzie" provides a much jauntier start to the mini-montage that opens the show. The song originally was recorded in 1920 by The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, but the version on the show is a cover by David Johansen (and my link goes to a 1930 cover of the song). Netting sets many boxes of Feeney's Irish Oats from Belfast onto the docks. Sleater supervises the arrival and checks his watch. Trucks carry the boxes of oats elsewhere where a man in a tux greets their arrival. Workers haul the crates down basement steps and open them — not surprisingly to find bottles of Irish whiskey. Babette smokes on a cigarette and watches. We begin to hear a preacher quoting from the Bible as the song slips into the background and more boxes of "oats" are wheeled into a tavern. "From The Book of Deuteronomy 24:14, Thou shalt not oppress a hired servant that is poor and needy, whether he be of thy brethren, or of thy strangers — " The scene switches to the Boardwalk where

the pastor's words can be heard more clearly, though we don't see him yet. A bored operator sits next to his empty rolling chair. "that are in thy land within thy gates," the preacher finishes the verse. We then see Owen carrying a box of those Irish oats. As he walks along, we see that the pastor (Helmar Augustus Cooper) preaches to the striking black workers on the Boardwalk, bearing picket signs that read "ON STRIKE," "UNFAIR" and "HONEST PAY FOR AN HONEST DAY." "Brothers, the Lord knew that fairness was not something to be tossed out by those in power like so many crusts of bread. The Lord knew that decency and fairness were a commitment, a promise to those who serve faithfully that they too will be served in turn. Amen. And the strong and the weak have no color, and they shall know the truth," the preacher continues. Leaning against a bench by the railing next to the beach is Deputy Raymond Halloran and another member of the Sheriff's Department. "The strong are not as mighty as they think and the weak have mercy," his sermon begins to be drowned out by the music and the crowd's chants. Sleater walks through the strikers toward the Ritz Carlton, but two men block his path. The men look to Dunn Purnsley who gives a nod and then they let Owen proceed.

the pastor's words can be heard more clearly, though we don't see him yet. A bored operator sits next to his empty rolling chair. "that are in thy land within thy gates," the preacher finishes the verse. We then see Owen carrying a box of those Irish oats. As he walks along, we see that the pastor (Helmar Augustus Cooper) preaches to the striking black workers on the Boardwalk, bearing picket signs that read "ON STRIKE," "UNFAIR" and "HONEST PAY FOR AN HONEST DAY." "Brothers, the Lord knew that fairness was not something to be tossed out by those in power like so many crusts of bread. The Lord knew that decency and fairness were a commitment, a promise to those who serve faithfully that they too will be served in turn. Amen. And the strong and the weak have no color, and they shall know the truth," the preacher continues. Leaning against a bench by the railing next to the beach is Deputy Raymond Halloran and another member of the Sheriff's Department. "The strong are not as mighty as they think and the weak have mercy," his sermon begins to be drowned out by the music and the crowd's chants. Sleater walks through the strikers toward the Ritz Carlton, but two men block his path. The men look to Dunn Purnsley who gives a nod and then they let Owen proceed.Owen carries his box into the dark, empty kitchen of the Ritz where its manager sits by himself. "Are you the man to see?" he asks. "Unless there's someone else in here with his thumb in his ass?" the kitchen manager replies. Sleater tells the morose man that Nucky Thompson sent him. "Thought they hung him up," the manager says. Owen opens the box and shows the man what it really contains. "Is that real?" the manager asks. "Straight from the old girl's tit," Owen tells him. The manager quickly finishes what remains in his coffee cup and then holds it out for Owen to pour a sample of the whiskey into and starts to sip. "Thirty dollars a case — that's less than half the going rate," Owen tells him as he drinks. "Who's going to serve it?" the manager wonders out loud. "Someday this strike will end sir — and so will this deal on this fine — Irish — whiskey," Sleater tells him, stretching out the words. The manager nods in contemplation before agreeing to buy 400 cases.

Sigrid rocks and feeds Baby Abigail as Van Alden drinks his morning coffee. He compliments her for how natural she seems to be at her job and she tells him that she’s the oldest of seven children. She also shares the story that her mother told her about when Sigrid was 6-years-old and tried to feed her baby sister from her bosom. Nelson puts his cup in the sink and leaves some money for groceries when he spots a letter addressed to him from Rose. “When did this come? Why didn’t I get this?” he asks. “Yesterday. I leave it for you there,” Sigrid replies. Nelson’s aggravation bursts out. “I am to receive all correspondence from Mrs. Van Alden immediately,” he emphasizes as he rips open the envelope. “Ya. I thought you’d see it,” Sigrid says. The envelope contains a Petition for Divorce from the U.S. District Court of New York, Westchester County. Rose Van Alden vs. Nelson Van Alden. Rose also inserted a handwritten note that reads, "Nelson, Please attend to this as soon as your activities allow. Rose."

Dr. Holt exits Emily's room as Margaret. Nucky and Teddy arrive. Margaret asks Holt how Emily is doing. "She's sleeping — a bit of a rough patch, nausea and such," he tells her. "Why did no one ring me? I would've stayed the night," Margaret says. "I know how hard this is for you, but she's in good hands here. She'll need your love and patience later on," Holt assures Margaret. "Later when?" she inquires. The

doctor gives a half-hearted smile and let's Nucky and Teddy know that they can go in and see Emily if they like. FYI: I couldn't find a direct link to this information, so I typed it. Patients infected with the poliovirus can pass the virus on seven to 10 days before the onset of disease. In addition, they can continue to shed the virus in their stool for three to six weeks. "Come on son — be very quiet. Like cat feet," Nucky instructs Teddy as the two enter Emily's room and leave Margaret to talk to Dr. Holt. "Her lungs are sound, nerves to the heart and upper limbs seem unaffected, but the damage to her legs could be extensive," Holt informs Margaret. "Will she be crippled?" Margaret asks. "At this stage, it's impossible to say. I've seen children worse than her make a complete recovery," Holt answers. "Mr. Thompson is a man of means. If there's anything to be done — " Holt cuts Margaret off so she doesn't think that money will solve the problem. "I wish it were simple as money. There are things that are out of our control, much as I want to tell you otherwise," the doctor says. Margaret looks in Emily's room and watches Nucky speak to her and tenderly pat the girl on the head while Teddy sits in a chair fiddling with his cap in his hands. "I have a little girl — she's 9. She says a prayer for these kids every night. She doesn't know them. I never taught her to do it," Holt shares with Margaret. “You’re meant to ask