Friday, May 18, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part I

By Edward Copeland

"First comes the word, then comes the rest" might be the most famous quote attributed to Richard Brooks, who began his life 100 years ago today in Philadelphia as Ruben Sax, son of Jewish immigrants Hyman and Esther Sax. He wrote a lot of words too — sometimes using only images. In fact, too many to tell the story in a single post. so it will be three. His parents came from Crimea in 1908 when it belonged to the Russian Empire. Like the parents of a great director of a much later generation and an Italian Catholic heritage, Hyman and Esther Sax also worked in the textile and clothing industry. Sax's entire adult working life revolved around the written word — even while he busied himself with other tasks. “I write in toilets, on planes, when I’m

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

Though Brooks' legend derives predominantly from his film legacy, he experienced his first rush of acclaim with the publication of his debut novel, written while stationed at Quantico at night in the bathroom, according to the account in Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks by Douglass K. Daniel. Several publishers rejected it until Edward Aswell at Harper & Brothers, who also edited Thomas Wolfe, agreed to take it — and he shocked Brooks further by telling him (after a few suggestions) they planned to publish in May 1945. This news flabbergasted Brooks who obtained a weekend pass to go to New York because Aswell insisted on informing him in person. Now Brooks had to return to Quantico where the top officers of the Corps about shit bricks when The New York Times published a big review of The Brick Foxhole soon after it hit shelves. (Orville Prescott's take was mixed, assessing it as compulsively readable but weak on characterization.) Its story of hate and intolerance within the Marines brought threats of court-martialing Brooks, since he'd ignored procedure and never submitted the novel to Marine officials for approval ahead of time. They wanted to avoid bad publicity, especially with all the good feelings as the war wound down. "There was nothing in that book that violated security, but their rules and regulations were not for that purpose alone," Brooks told Daniel. Aswell prepared to launch a P.R. counteroffensive with literary giants such as Sinclair Lewis and Richard Wright ready to stand by Brooks. In case you don't know the story of the novel, it concerns a Marine unit in its barracks and on leave in Washington. Through their wartime experiences, some of the men truly turned ugly, suspecting cheating wives and tossing hate against any non-white Christian. It turns out, though the real Marines let the matter drop, what bothered them

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

While he didn't want to make a movie of The Brick Foxhole himself, another former newspaperman turned socially conscious film artist met with Brooks about working with his independent production company. At first, Mark Hellinger tried to lure Brooks away from Universal with the promise of doubling his salary if he'd adapt a play he liked into a movie, but before Brooks could consider that offer, Hellinger called with a more pressing matter. He was producing an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's famous short story The Killers. The problem: someone had to dream up what happened after the brief tale ends because it certainly wouldn't last 90 minutes otherwise. Hellinger flew Brooks out to meet Papa himself, but he didn't get much out of him but he did come up with an idea for what would happen after the story ends. Hellinger liked it and sent it to John Huston, who wrote the screenplay as a favor. Since both Brooks and Huston had contracts at other studios, neither got screen credits, so Ernest Hemingway's The Killers' official screenplay credit goes to Anthony Veiller, who received an Oscar nomination for best screenplay. He'd previously shared a nomination in the same category for Stage Door. The film also made a star out of Burt Lancaster, who would work with Brooks several times and be his lifelong friend. In fact, Lancaster would star in the next screenplay that Brooks wrote, a Mark Hellinger production directed by one of those people Edward Dmytryk eventually would name before the House Un-American Activities Committee. The film, of course, would be the still-powerful Brute Force, the director, Jules Dassin.

John Huston wasn't happy. Producer Jerry Wald called him, excitement in his voice, to tell him he'd secured the rights to Maxwell Anderson's Broadway play Key Largo for Huston to direct. This didn't thrill Huston, who thought the play gave new meaning to the word awful. Written in blank verse, Anderson's play concerned a deserter from the Spanish-American War. People at a hotel do get taken hostage, but by Mexican hostages. Essentially, Huston tossed the play in the trash bin. Huston hired Brooks to co-write an in-title only version and, still pissed at Wald, barred him from the set. Part of Huston's anger stemmed from the HUAC nonsense, (His outrage would drive him to move to Ireland for a large part of the 1950s.) so he couldn't stomach adapting a play by Anderson whom he considered a reactionary because of his hate of FDR. Despite Huston's distaste for the project, he

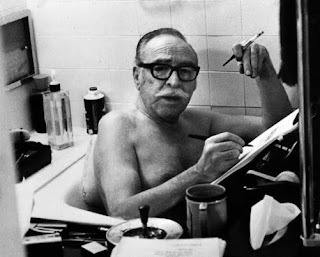

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.While I would have liked to have viewed more of Brooks' work that I've never seen (and to re-visit some which I have), time and availability, combined with his prolific nature and the industry's increasingly cavalier willingness to let both old and recent films fade into oblivion, proved to be a problem. After Huston's generosity, Brooks' directing debut would arrive two years later. Four films where Brooks worked

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.

enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.With 1955, Brooks wrote and directed the first film that truly garnered him an identity as more than a writer who directs but as a director with Blackboard Jungle, a film that admittedly manages to look both dated and timely simultanouesly, First, as so many old films did, it had to start with a long scroll explaining that American schools maintain high standards, but we need to worry about these juvenile

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk.

desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk. Tweet

Labels: blacklist, Bogart, Capra, Cary, Dassin, Doris Day, Edward G., Fiction, Fitzgerald, Fuller, Ginger Rogers, Glenn Ford, Hemingway, Huston, Lancaster, Liz, Mazursky, Poitier, Robert Ryan, Widmark