Monday, May 21, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part III

By Edward Copeland

It isn't often that a masterpiece of literature begets a masterpiece of cinema yet both retain distinct identities all their own, but that's the case with In Cold Blood, Truman Capote's "nonfiction novel" and Richard Brooks' stunning film adaptation of his book. Capote often gets credit for inventing the genre of adapting the techniques of a novelist to that of straight reporting, but earlier attempts existed — Capote's stood out because In Cold Blood 's excellence made everyone forget any other examples (at least until more than a decade later when Norman Mailer added his own brilliant take on the genre with The Executioner's Song). Brooks, with his job as a crime reporter in his past, on the surface appears to follow Capote's approach, but the director, forever the activist, skips the objectivity that Capote tried to evoke in his book. Brooks didn't want to minimize the horror of the crime that occurred at the Clutter farm in Holcomb, Kans., but he also wanted to humanize the killers, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. In a way, Brooks' film inspired the path for the two films made decades later telling the story of Capote's writing of the book and his getting to know the killers first-hand as they waited on Death Row. Even today, Brooks' 1967 film remains more powerful and better made than the two more recent tales. Undoubtedly, In Cold Blood remains Brooks' greatest film. If you got here before reading either Part I or Part II of this tribute, click on the respective links.

The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call "out there." Some seventy miles east of the Colorado border, the countryside, with its hard blue skies and desert-clear air, has an atmosphere that is rather more Far West than Middle West. The local accent is barbed with a prairie twang, a ranch-hand nasalness, and the men, many of them, wear narrow frontier trousers, Stetsons, and high-heeled boots with pointed toes. The land is flat, and the views are awesomely extensive; horses, herds of cattle, a white cluster of grain elevators rising as gracefully as Greek temples are visible long before a traveler reaches them.

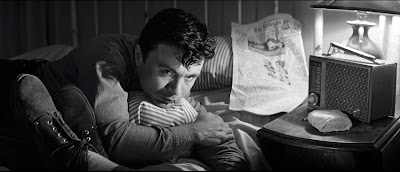

Capote begins his book with that paragraph in the first chapter titled The Last to See Them Alive. Brooks begins the film of In Cold Blood introducing us to The Last to See Them Alive in the forms of Robert Blake as newly paroled inmate Perry Smith and Scott Wilson as an acquaintance he met in prison who had been freed earlier, Dick Hickok. Brooks gives Blake — and the movie — a memorable entrance, especially thanks to his decision to go against the grain of the time and film in black-and-white Panavision. We see a bus driving down a two-lane highway, passing signs showing the distance to different Kansas towns, including the horrific Olathe. On the bus, a young female stumbles down the aisle to get a closer look at the pair of pointed-toe cowboy boots with buckles on its heels before creeping back. The shadowy man who wears the boots also has a guitar strung around his neck. A flame suddenly illuminates Robert Blake's face as he lights a cigarette and Quincy Jones' ominous yet jazzy score kicks in to start the credits. The sequence not only sets the tone for the film that follows, it also introduces us to the movie's most important participant — cinematographer Conrad L. Hall (though he didn't need to use the L. yet since his son, Conrad W. Hall, wasn't old enough to follow his dad into the business).

The movie spends its opening minutes introducing us to the soft-spoken Perry and getting him hooked up with Dick. Whereas Blake's Perry comes off as a puppy repeatedly kicked by his owner, Scott Wilson portrays Hickok as a cocky, livewire and a chatterbox — and Brooks gives him great lines, especially in the scenes where he and Blake drive around. "Ever seen a millionaire fry in the electric chair? Hell, no. There's two kinds of laws, one for the rich and one for the poor," Dick imparts as wisdom to Perry. When the two buy supplies for the planned robbery of the Clutter farm, Dick shoplifts some razorblades for no good reason, leading Perry to chastise him for taking such a risk for something so small. "That was stupid — stealin' a lousy pack of razor blades! To prove what?" Perry asks. Smiling, Dick replies, "It's the national pastime, baby, stealin' and cheatin'. If they ever count every cheatin' wife and tax chiseler, the whole country would be behind prison walls." Though in the two recent biographical films about Truman Capote's research into the case, it's strongly implied that Capote at least developed a crush on Smith and that Perry may have been gay. In Cold Blood never explicltly claims that Perry Smith was gay, but throughout the film Dick taunts him by

calling him "honey," "baby" or something along those lines. Hickock on the other hand chases every skirt he gets near and during the robbery/murder, Perry intervenes to stop Dick from raping the Clutters' 16-year-old daughter Nancy (Brenda Currin). Wilson made his first two feature films in 1967 and he landed roles in two of the biggest — this one and the eventual Oscar winner for best picture, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night. The jaws of younger readers should hit the floor when they see Wilson's great work here and it slowly dawns on them that playing Dick Hickok is a younger incarnation of Herschel on AMC's The Walking Dead. When Perry and Dick do get together, they meet at Dick's father's house where Dick tries to aid his old man, who's slowly losing his battle with terminal cancer. (Veteran character actor Jeff Corey, who co-starred in the Brooks-scripted 1947 classic Brute Force, plays the elder Hickock.) Contrasting Capote's take with Brooks' version fascinates in the ways the works reflect each other yet, like a mirror, many things appear on the opposite side. The book introduces its readers to the Clutter family first before Perry and Dick enter the story (by name anyway). Brooks' screenplay reverses the order, beginning with the killers then letting us meet the Kansas family. However, both aim to draw parallels between the victims and their eventual murderers. "That morning an apple and a glass of milk were enough for him; because

calling him "honey," "baby" or something along those lines. Hickock on the other hand chases every skirt he gets near and during the robbery/murder, Perry intervenes to stop Dick from raping the Clutters' 16-year-old daughter Nancy (Brenda Currin). Wilson made his first two feature films in 1967 and he landed roles in two of the biggest — this one and the eventual Oscar winner for best picture, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night. The jaws of younger readers should hit the floor when they see Wilson's great work here and it slowly dawns on them that playing Dick Hickok is a younger incarnation of Herschel on AMC's The Walking Dead. When Perry and Dick do get together, they meet at Dick's father's house where Dick tries to aid his old man, who's slowly losing his battle with terminal cancer. (Veteran character actor Jeff Corey, who co-starred in the Brooks-scripted 1947 classic Brute Force, plays the elder Hickock.) Contrasting Capote's take with Brooks' version fascinates in the ways the works reflect each other yet, like a mirror, many things appear on the opposite side. The book introduces its readers to the Clutter family first before Perry and Dick enter the story (by name anyway). Brooks' screenplay reverses the order, beginning with the killers then letting us meet the Kansas family. However, both aim to draw parallels between the victims and their eventual murderers. "That morning an apple and a glass of milk were enough for him; because he touched neither coffee or tea, he was accustomed to begin the day on a cold stomach. The truth was he opposed all stimulants, however gentle. He did not smoke, and of course he did not drink; indeed, he had never tasted spirits, and was inclined to avoid people who had — a circumstance that did not shrink his social circle as much as might be supposed, for the center of that circle was supplied by the members of Garden City's First Methodist Church, a congregation totaling seventeen hundred, most of whom were as abstemious as Mr. Clutter could desire," Capote described the Clutter patriarch. A few pages later in the first chapter, Perry Smith makes his entrance into Capote's book. "Like Mr. Clutter, the young man breakfasting in a cafe called the Little Jewel never drank coffee. He preferred root beer. Three aspirin, cold root beer, and a chain of Pall Mall cigarettes — that was his notion of a proper "chow-down." Sipping and smoking, he studied a map spread on the counter before him — a Phillips 66 map of Mexico — but it was difficult to concentrate, for he was expecting a friend, and the friend was late. He looked out a window at the silent small-town street, a street he had never seen until yesterday. Still no sign of Dick," Capote wrote. Brooks uses a visual link to draw victim and killer together, showing Herbert Clutter (John McLiam) performing his morning shave. As Clutter leans into the sink to rinse the remaining shaving cream from his face, the face that rises up and looks in the mirror sees Perry Smith, excising his excess whiskers as well.

he touched neither coffee or tea, he was accustomed to begin the day on a cold stomach. The truth was he opposed all stimulants, however gentle. He did not smoke, and of course he did not drink; indeed, he had never tasted spirits, and was inclined to avoid people who had — a circumstance that did not shrink his social circle as much as might be supposed, for the center of that circle was supplied by the members of Garden City's First Methodist Church, a congregation totaling seventeen hundred, most of whom were as abstemious as Mr. Clutter could desire," Capote described the Clutter patriarch. A few pages later in the first chapter, Perry Smith makes his entrance into Capote's book. "Like Mr. Clutter, the young man breakfasting in a cafe called the Little Jewel never drank coffee. He preferred root beer. Three aspirin, cold root beer, and a chain of Pall Mall cigarettes — that was his notion of a proper "chow-down." Sipping and smoking, he studied a map spread on the counter before him — a Phillips 66 map of Mexico — but it was difficult to concentrate, for he was expecting a friend, and the friend was late. He looked out a window at the silent small-town street, a street he had never seen until yesterday. Still no sign of Dick," Capote wrote. Brooks uses a visual link to draw victim and killer together, showing Herbert Clutter (John McLiam) performing his morning shave. As Clutter leans into the sink to rinse the remaining shaving cream from his face, the face that rises up and looks in the mirror sees Perry Smith, excising his excess whiskers as well.

The biggest difference between the book and the movie came with Brooks' introduction of a Truman Capote surrogate, a magazine reporter named Jensen, who travels to Holcomb to cover the case. Jensen isn't played in a way similar to the extremely distinctive Capote — such as the way that won Philip Seymour Hoffman an Oscar for Capote, that Toby Jones played even better in Infamous or that Tru himself played best of all as Lionel Twain in Neil Simon's 1976 mystery spoof Murder By Death. Brooks wrote the Jensen character straight (no pun intended) and conventionally, even giving him a narrator's function at times. He doesn't precisely follow how Capote researched the story though because Capote didn't arrive in Kansas until after Smith and Hickok had been apprehended. In the movie, Jensen arrives almost from the beginning of the investigation. For the role of Jensen, Brooks cast another veteran character actor — Paul Stewart, whose first credited screen role was the butler Raymond in Citizen Kane. His 42-year film and television career ended in 1983 with an episode of Remington Steele and he died three years later, a month shy of his 88th birthday. After starting with Kane, a few of Stewart's eclectic highlights included Champion, Brooks' Deadline-U.S.A., The Bad and the Beautiful, Kiss Me Deadly, Hell on Frisco Bay, King Creole, Opening Night, Revenge of the Pink Panther,

S.O.B. and appearances on nearly every episodic police or detective show between the 1950s and the 1970s, including The Mod Squad. The Jensen character arrives around the same time that the Kansas Bureau of Investigation joins the case led by John Forsythe as Alvin Dewey, what may be Forsythe's best performance. Brooks gives him a lot of speeches — and some come off as less pristine than others, but Forsythe succeeds at selling most of them. Forsythe gets so identified with Dynasty or as a voice on Charlie's Angels that I think people forget that he really act when the material was there for him as it was here or in the short-lived and underrated Norman Lear sitcom The Powers That Be and having fun with Hitchcock in The Trouble With Harry (though no one could help Topaz much). He also was a replacement performer of one of the major roles in Arthur Miller's All My Sons on Broadway. Granted, didn't see him, but he had to show some chops to land that one. Of his filmed work though, I think In Cold Blood stands as the best. Sure, this speech reads as overwrought, but he pulled it off as he delivered it to Jensen. "Someday, someone will have to explain the motive of a newspaper to me. First, you scream, 'Find the bastards.' Till we do find 'em, you want to get us fired. When we find 'em, you accuse us of brutality. Before we go

S.O.B. and appearances on nearly every episodic police or detective show between the 1950s and the 1970s, including The Mod Squad. The Jensen character arrives around the same time that the Kansas Bureau of Investigation joins the case led by John Forsythe as Alvin Dewey, what may be Forsythe's best performance. Brooks gives him a lot of speeches — and some come off as less pristine than others, but Forsythe succeeds at selling most of them. Forsythe gets so identified with Dynasty or as a voice on Charlie's Angels that I think people forget that he really act when the material was there for him as it was here or in the short-lived and underrated Norman Lear sitcom The Powers That Be and having fun with Hitchcock in The Trouble With Harry (though no one could help Topaz much). He also was a replacement performer of one of the major roles in Arthur Miller's All My Sons on Broadway. Granted, didn't see him, but he had to show some chops to land that one. Of his filmed work though, I think In Cold Blood stands as the best. Sure, this speech reads as overwrought, but he pulled it off as he delivered it to Jensen. "Someday, someone will have to explain the motive of a newspaper to me. First, you scream, 'Find the bastards.' Till we do find 'em, you want to get us fired. When we find 'em, you accuse us of brutality. Before we go into court, you give them a trial in the newspaper, When we finally get a conviction, you want to save 'em by proving they were really crazy in the first place. All of which adds up to one thing — you've got the killers," Dewey tells Jensen as he's taking down to the basement of the Clutter house. Dewey also serves as Mr. Exposition, explaining why these two numbskulls just out of prison would decide to go to this one particular farmhouse and rob this family, making sure to "leave no witnesses," even though Dick and Perry only gain $40 from the crime. A fellow investigator asks Dewey if Clutter might have been rich and Alvin sort of laughs knowingly. "Ahh — the old Kansas myth. Every farmer with a big spread is supposed to have a secret black box with lots of money in it." It isn't until the ending that you realize the Brooks gave Dewey some of that dialogue because he's supposed to symbolize the parts of the system that disgust him. Brooks ardently opposed capital punishment and he made no secret that he wanted the ending to make clear that it was murder. At Smith's hanging, another reporter asks Dewey about how much the executioner makes. "Three hundred dollars a man," Dewey answers. "Who does he work for? Does he have a name?" the reporter follows up and then poor John Forsythe has to deliver the clunkiest line of dialogue in the entire film. "Yes. We the people." Earlier, it had been the topic of discussion between Jensen and an imprisoned Hickock.

into court, you give them a trial in the newspaper, When we finally get a conviction, you want to save 'em by proving they were really crazy in the first place. All of which adds up to one thing — you've got the killers," Dewey tells Jensen as he's taking down to the basement of the Clutter house. Dewey also serves as Mr. Exposition, explaining why these two numbskulls just out of prison would decide to go to this one particular farmhouse and rob this family, making sure to "leave no witnesses," even though Dick and Perry only gain $40 from the crime. A fellow investigator asks Dewey if Clutter might have been rich and Alvin sort of laughs knowingly. "Ahh — the old Kansas myth. Every farmer with a big spread is supposed to have a secret black box with lots of money in it." It isn't until the ending that you realize the Brooks gave Dewey some of that dialogue because he's supposed to symbolize the parts of the system that disgust him. Brooks ardently opposed capital punishment and he made no secret that he wanted the ending to make clear that it was murder. At Smith's hanging, another reporter asks Dewey about how much the executioner makes. "Three hundred dollars a man," Dewey answers. "Who does he work for? Does he have a name?" the reporter follows up and then poor John Forsythe has to deliver the clunkiest line of dialogue in the entire film. "Yes. We the people." Earlier, it had been the topic of discussion between Jensen and an imprisoned Hickock.DICK: Perry's the only one talking against capital punishment.

JENSEN: Don't tell me you're for it.

DICK: Hell, hangin' only getting revenge. What's wrong with revenge? I've been revenging myself all my life.

Part of the film's brilliance stems from the way Brooks structures the scenes detailing the crime itself. Toward the beginning of the movie, he presents what probably remains the greatest sequence of his directing career without actually showing the murder. Then, as the film winds down, he shows us what we didn't see and it's horrifying. Through a window of the farmhouse, we can see Nancy kneeling beside her bed saying her prayers. At that moment, it isn't made clear who could be seeing that — are Dick and Perry outside her window or are we simply the voyeurs right then? A split second later we spot Dick and Perry still sitting in the car beneath the cover of night. I guess it was us. The discordant sound of a doorbell suddenly fills the soundtrack and the viewer realizes he or she has moved inside the Clutter house — and sunlight shines through the windows. The camera tracks slowly around the furniture of the living room as it makes its way toward the front door. A woman and some other people open the door calling out for the Clutters. We faintly hear church bells tolling and the visitors wear their Sunday best. The woman continues to call out the Clutters by their first names as she ascends the stairs to the second floor. The film cuts quickly to the house's

exterior just as we hear the woman let out a horrified scream. Coming on the heels of The Professionals, it's as if somehow Brooks transformed himself from a competent director and damn good writer into a master of both. I don't know if the fact he had Conrad Hall working as his d.p. on both films made any sort of difference or if that proved to be just fortuitous, but that one-two punch sealed Brooks' artistic reputation forever beyond what respect he'd earned before. I've never been fortunate enough to see In Cold Blood on the big screen and allow Hall's haunting and beautiful mix of light and shadow to bathe me in its glow, but I did get the next best thing when in 1993 at the Inwood Theater in Dallas I saw Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy and Stuart Samuels' documentary Visions of Light, a film devoted to the art of cinematography and highlighting some of its greatest practitioners and their best moments. One of the highlighted scenes comes from In Cold Blood when Robert Blake as Perry gives an emotional monologue about his father in his prison cell while he looks out the window at the rain coming down. The reflection of the raindrops cast shadows on Blake's face that make it appear as if he's crying. The moment stuns in its beauty — even when you learn that as so many say, accidents ends up producing some of the best parts of film. Hall admitted it hadn't been planned but the humidity in the prison set had pumped up the window's perspiration so much (as well as everyone else's) that's how the magic happened. Thankfully, YouTube had that clip.

exterior just as we hear the woman let out a horrified scream. Coming on the heels of The Professionals, it's as if somehow Brooks transformed himself from a competent director and damn good writer into a master of both. I don't know if the fact he had Conrad Hall working as his d.p. on both films made any sort of difference or if that proved to be just fortuitous, but that one-two punch sealed Brooks' artistic reputation forever beyond what respect he'd earned before. I've never been fortunate enough to see In Cold Blood on the big screen and allow Hall's haunting and beautiful mix of light and shadow to bathe me in its glow, but I did get the next best thing when in 1993 at the Inwood Theater in Dallas I saw Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy and Stuart Samuels' documentary Visions of Light, a film devoted to the art of cinematography and highlighting some of its greatest practitioners and their best moments. One of the highlighted scenes comes from In Cold Blood when Robert Blake as Perry gives an emotional monologue about his father in his prison cell while he looks out the window at the rain coming down. The reflection of the raindrops cast shadows on Blake's face that make it appear as if he's crying. The moment stuns in its beauty — even when you learn that as so many say, accidents ends up producing some of the best parts of film. Hall admitted it hadn't been planned but the humidity in the prison set had pumped up the window's perspiration so much (as well as everyone else's) that's how the magic happened. Thankfully, YouTube had that clip.It must be said how good a performance Blake gives while at the same time acknowledging that it can't be viewed the way many of us assessed it originally. When a Naked Gun movie pops up and you see O.J. Simpson play an idiot and constantly take a beating, somehow that's OK. When you watch In Cold Blood again and see Blake give such a convincing and chilling performance as a mass murderer (especially when Forsythe's Alvin Dewey engages him in conversation during the ride to jail and Perry tells him, "I thought Mr. Clutter was a very nice gentleman. I thought it right till the moment I cut his throat."), you can't help but recall that a few decades later, the actor stood trial and received an acquittal for killing his wife. It doesn't stand out as groundbreaking now, when last night's Mad Men said shit twice, but in 1967, In Cold Blood became the first major release to utter the word bullshit. For the second year in a row, Brooks received Oscar nominations for directing and adapted screenplay and Hall got one for cinematography. Quincy Jones also picked up a nomination for original score, though Jones didn't receive one for his music for In the Heat of the Night. I don't understand how the nimrods at the Academy left it out of the top five for best picture. They nominated two films that deserved to be there: Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate. The film that won, a fine film but certainly expendable: In the Heat of the Night. A perceived prestige project of social significance that's overrated as hell: Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. The fifth nominee that would make no sense in any year: Doctor Dofuckinglittle. Basically, three out of the five films could have been tossed to make room for In Cold Blood. A few other more deserving 1967 titles: Cool Hand Luke, The Dirty Dozen, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, Accident, Wait Until Dark, Point Blank, The Jungle Book. The National Board of Review did honor Brooks' direction. Brooks also received his sixth Directors Guild nomination and his sixth Writers Guild nomination. With the exception of the WGA, Brooks would never be named for any of the top awards again. In Cold Blood marked his best, but from there things went downhill fast.

One of the most difficult films to find (I've never seen it) for that recent a film with a best actress nomination. Brooks wrote his first original screenplay since Deadline-U.S.A. as a vehicle for wife Jean Simmons. From descriptions I've read, Simmons plays Mary Wilson, who was raised on romantic notions of marriage from the movies, finds herself in a funk on her anniversary and flies to the Bahamas on a whim, running into a free spirit (Shirley Jones) while there.

I missed this one as well. From TCM's web site; "In Hamburg, Germany, American Joe Collins (Warren Beatty) is considered by bank manager Kessel (Gert Fröbe) to be the most honest, hard-working bank security expert in the world. Unknown to Kessel, Joe has been devising a plan with his girlfriend, American expatriate prostitute Dawn Divine (Goldie Hawn), to take the contents from bank safe-deposit boxes owned by several criminals and place them into one owned by Dawn. Roger Ebert gave it three stars in his original review.

I wanted to see this one, but just ran out of time. Here's what qualifies as TCM's full synopsis: A former roughrider (Gene Hackman) matches wits with a lovely but shady lady-in-distress (Candice Bergen), as a drifting ex-cowboy (James Coburn) and a young, reckless cowboy (Jan-Michael Vincent) join in on a 700 mile journey. Ebert gave it three and a half stars in his original review.

I've actually seen this one. In fact, as we near the end of Brooks' career, I've watched two of the last three movies. As an unrelated sidenote, this year also marked the end of Brooks' 17-year marriage to Jean Simmons. If by chance you aren't familiar with this movie, think of it as sort of the Shame of the 1970s — and I don't mean the Ingmar Bergman movie. Diane Keaton stars as a teacher of deaf students whose affair with her college professor ends badly. She reacts as anyone would to a breakup — she starts cruising New York bars and picking up strangers for one-night stands while also developing a taste for drugs. The film definitely didn't belong in the genre of liberated women films of the 1970s as Keaton's character will pay. I saw this when I was a young man and I found it distasteful then, though it did have more sensible plotting than last year's Shame. Brooks directed his last performer to an Oscar nomination with Tuesday Weld getting a supporting actress nod. Keaton won the best actress Oscar for 1977 — but for Annie Hall. Brooks adapted a novel by Judith Rossen that was loosely based on a real incident, but most reviews by people who had read the novel seemed to indicate that Brooks changed key elements. Then, that matches the speech Brooks gave the movie's cast and crew on the first day of shooting, according to Douglass K. Daniel's Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks. "I'm sure that all of you have your own ideas about what kind of contributions you can make to this film, what you can do to improve it or make it better. Keep it to yourself. It's my fucking movie and I'm going to make it my way!" Daniel wrote. Goodbar also featured Richard Gere in one of his earliest roles. This clip plays off the tension of whether fun and games are at hands or something more dangerous.

Brooks referred to this film as "the biggest disaster" of his career. Later, he amended it slightly, blaming TV for purposely not coverage the film because the movie criticized "checkbook journalism." Having watched Wrong Is Right for the first time recently, this compels me to ask, "It did?" Sean Connery stars as a globetrotting reporting for what appears to be a CNN-like news station. The opening sequence contains some amusing moments, (including a young Jennifer Jason Leigh, nearly 30 years after her dad Vic Morrow played the worst punk in Brooks; Blackboard Jungle) but what could be cutting-edge satire of a media form just being born transforms into a scattershot satire involving fictional oil-rich African countries, the CIA, a presidential race and arms dealers trading suitcase nukes, Based on a novel, I hope that it had a plot, but Wrong Is Right just ends up being one of those strange satires like The Men Who Stared at Goats where once it ends you still don't know what the hell happened. This clip shows the opening sequence. Nothing after it deserves your attention.

I've got good news and bad news when it comes to Richard Brooks' final film. The good news: it brought him awards consideration again. The bad news: It was at the Razzies where it earned nominations for worst picture, worst director, worst screenplay and worst musical score. I'm not sure whether or not it relieved him that the film lost in all four categories, with Rambo: First Blood Part II taking worst picture, director and screenplay and Rocky IV winning worst score dishonors. I have not seen Fever Pitch which TCM hasn't even given a synopsis, but I know enough to tell you that Ryan O'Neal plays an investigator reporter doing a story on compulsive gambling who discovers he suffers from the problem. The subject of the movie came up on my Facebook page and Richard Brody, critic at The New Yorker, commented, "I saw Fever Pitch when it came out and loved every overheated second. Haven't seen it since then. Seeing The Connection has brought it back: no detached observer but a participant almost instantly in over his head." At the time of its release, it became one of the rare films that Ebert gave zero stars.

Following Fever Pitch, Brooks toyed with the idea of writing a screenplay about the blacklist, basing it around an incident in 1950 when fights broke out at the Directors Guild over the loyalty oath, but he didn't get around to it. The man who could be quite a bully on the set, had quite a bit of bitterness toward the industry by now as he showed in the second half of that 1985 interview.

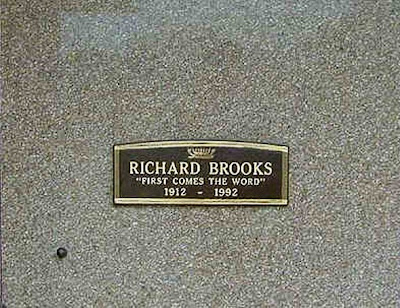

Richard Brooks died of congestive heart failure on March 11, 1992, at 79. He did have close friends, but most of them had died themselves by then. The stepdaughter he basically raised as his own when he married Jean Simmons, Tracy Granger, made certain, his tombstone bore the only appropriate epitaph for the man.

Tweet

Labels: Arthur Miller, blacklist, Books, Capote, Connery, Diane Keaton, Ebert, Hackman, Hitchcock, J.J. Leigh, James Coburn, Jean Simmons, Jewison, Mailer, N. Lear, Neil Simon, P.S. Hoffman, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, April 16, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Catherine Scorsese

around the world, there would be no need for social workers."

— Nicholas Pileggi on Catherine Scorsese at a family-style dinner serving her recipes

held in her honor following her death at 84 in 1997.

By Edward Copeland

Pileggi, the author of the nonfiction books Wiseguy and Casino, and co-writer of their film versions, Goodfellas and Casino, with Martin Scorsese was speaking of the director's late mother, who engendered that feeling in many in Martin Scorsese's extended film family. At the same time, her frequent appearances in her son's films (and other directors' movies as well) made Catherine Scorsese one of the most

recognizable filmmaker's mothers who didn't work in show business to make a living. When Mrs. Scorsese did hold a job, she worked as a seamstress in New York's Garment District where she met Marty's father, Charles Scorsese, who toiled there as a clothes presser and also frequently appeared in their son's films as well until his death in 1993. Catherine Cappa, born 100 years ago today in New York to parents who emigrated from Sicily, also was a helluva cook, a gift passed down through generations of her family and Charles'. In fact, Catherine's culinary talents inspired the memorial dinner party that Suzanne Hamlin wrote about in The New York Times in February 1997. Catherine had gathered some of the best of the Scorsese and Cappa family recipes and published them in Italianamerican: The Scorsese Family Cookbook, which reached store shelves in December 1996. Unfortunately, her bout with Alzheimer's had advanced too far to allow her to promote the cookbook and she passed away the following month. I love Italian food and imagine consuming one of her dinners would have been one of the highlights of my life. However, her family recipes' reputation ring up resounding endorsements, but I imagine that her greatest creation of all goes by the name of Martin Charles Scorsese and her role in delivering that gift to the world prompted me to write this tribute to her today.

recognizable filmmaker's mothers who didn't work in show business to make a living. When Mrs. Scorsese did hold a job, she worked as a seamstress in New York's Garment District where she met Marty's father, Charles Scorsese, who toiled there as a clothes presser and also frequently appeared in their son's films as well until his death in 1993. Catherine Cappa, born 100 years ago today in New York to parents who emigrated from Sicily, also was a helluva cook, a gift passed down through generations of her family and Charles'. In fact, Catherine's culinary talents inspired the memorial dinner party that Suzanne Hamlin wrote about in The New York Times in February 1997. Catherine had gathered some of the best of the Scorsese and Cappa family recipes and published them in Italianamerican: The Scorsese Family Cookbook, which reached store shelves in December 1996. Unfortunately, her bout with Alzheimer's had advanced too far to allow her to promote the cookbook and she passed away the following month. I love Italian food and imagine consuming one of her dinners would have been one of the highlights of my life. However, her family recipes' reputation ring up resounding endorsements, but I imagine that her greatest creation of all goes by the name of Martin Charles Scorsese and her role in delivering that gift to the world prompted me to write this tribute to her today. In the 1990 American Masters episode "Martin Scorsese Directs," Charles and Catherine discussed what their son's early life was like growing up in New York's Little Italy. The sound in this clip is missing at the beginning, but then it kicks in.

Martin Scorsese started putting his mother into small roles in his films from the beginning (Charles didn't show up on camera until Scorsese's 1974 short documentary on them, Italianamerican) for financial reasons: He couldn't afford to pay actors. Catherine's personality not only proved made for the camera but she also displayed a charming gift for improvising dialogue. She appeared in her son's very first short, a 1964 comedy called It's Not You, Murray, which co-starred Mardik Martin who co-wrote the short with Scorsese and would go to co-write the screenplays for Mean Streets, New York, New York and Raging Bull. The comedy short about an accidental crook also featured future SCTV star Andrea Martin (no relation to Mardik). Catherine turned up again in Who's That Knocking at My Door? and Mean Streets, both of which starred Harvey Keitel who attended that memorial dinner and said of Mrs. Scorsese, "In my memory, Catherine was the epitome of a warm, loving Italian mother. She enjoyed watching me eat as much as I enjoyed eating her cooking." Then, as his feature filmmaking career had started to really take off, Martin took some time to make that 45-minute short documentary Italianamerican where the real Catherine Scorsese shines in all her glory. This segment details his parents' recent visit to Italy.

The end credits for Italianamerican actually ran the family recipe for spaghetti sauce and meatballs. The next time that Catherine contributed to one of her son's films, she only put in a vocal appearance as Rupert Pupkin's hector mother constantly yelling at him from upstairs in the great The King of Comedy with longtime fan of her homemade pizza, Robert De Niro.

Catherine Scorsese's next two film roles actually occurred in films that weren't directed by her son. First, in 1986 she played a birthday party guest in Brian De Palma's alleged comedy starring Danny DeVito and Joe Piscopo. The next year, she waited to be served as a customer at the bakery in Norman Jewison's Moonstruck. Later, she would play a woman in a cafe in Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather Part III. She also appeared in a 1994 movie called Men Lie that played a lot of film festivals, but I'm not sure if it ever received a theatrical release. Watch this promo and try to count how many actors in it eventually showed up on The Sopranos.

Catherine's next appearance in one of her son's film remains her longest and most memorable role as the lovable mother of Joe Pesci's psychotic mobster Tommy DeVito in Goodfellas. Pesci also attended the memorial dinner party for Katherine and told The Times, "Katie was one of the sweetest ladies I ever met. She was a true innocent. She never did anything bad; she never knew anything bad. In terms of her cooking, it's a toss-up as to who's a better cook, Katie or my mother." The hysterical scene where Tommy, Jimmy Conway (De Niro) and Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) drop by her house in the middle of the night looking for tools to dispose of a body in the trunk of Henry's car and she wakes up and insists on feeding them remains a classic scene in a film that's wall-to-wall classics. Of course, embedding Goodfellas clips from YouTube strictly won't be allowed, so you'll just have to click on that word "scene" to watch it again. However, we do have a clip from an AFI special where Jim Jarmusch interviews Martin Scorsese about his mother's role in the scene.

The next movie her son made, the role wasn't as plum as Tommy's mother — she merely shopped at a fruit stand in his Cape Fear remake. To promote the film, Marty appeared as a guest on Late Night with David Letterman in November 1991, and even took Catherine along to make some of that homemade pizza that De Niro loves so much for Marty, Dave and another guest we all know and love.

I so dearly wish I could have found a screenshot or YouTube clip of her appearance in 1993's The Age of Innocence because it's such a touching gift to his parents. Charles Scorsese died on Aug. 22, 1993 and The Age of Innocence would end up being his last appearance in one of his son's movies. The movie itself didn't get released until Oct. 1, but the image Scorsese filmed of his parents, showing them moving slowly toward the camera in a snowy, white haze couldn't have been a lovelier image. His mother managed to appear in a character role in a scene in Casino, his next movie, and that would be her last appearance.

What a gift Catherine Cappa Scorsese and Charles Scorsese gave the world. It's the American story. They were first-generation Italian Americans, struggling to raise two sons in New York while eking out livings in the Garment District. Keeping careful watch on the one boy, an asthmatic child who couldn't go play sports as the other children could but discovered a grand universe in the movies his father took him to at a young age. Charles Scorsese's centennial doesn't occur until next year, but honestly this tribute belongs to both of them (Catherine couldn't have created Marty by herself or we would have an entirely different story on our hands). If you haven't seen it, try to watch Italianamerican. I'm not the biggest believer in otherworldly things, but I'm grateful for fate, higher powers or whatever joined Charles and Catherine together to give us the unbelievably wonderful gift of their son.

Tweet

Labels: Books, Coppola, De Niro, De Palma, DeVito, Documentary, Jewison, Keitel, Letterman, Liotta, Murray, Pesci, Scorsese, The Sopranos

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, November 03, 2011

Scratching Out a Tune Without Breaking One's Neck

By Damian Arlyn

Anyone who knows me fairly well is aware of the fact that I not only have a tremendous love of cinema but of theatre. My infatuation with the stage came in high school when I was cast in four (count ‘em, four) roles in a production of Nicholas Nickleby. That’s when I was, as the saying goes, “bitten by the bug,” and ever since I’ve taken as many opportunities as I can to participate in local plays as an actor or director. One of the highlights of my theatrical “career” was playing Motel the tailor in a production of Fiddler on the Roof during my mid-20s. It was not the first time I’d been involved in a staging of this show, having helped out with a production done by my old high school a few years earlier. It was also not the last time I would ever see it performed on stage since my fellow cast members and I attended another production of it about a year later. Needless to say, it’s a show with which I am very familiar. It has been, for a long time now, one of my favorite musicals, and it all began with my exposure to the 1971 film. I watched it at a young age and fell in love with it immediately. It has become one of my favorite movie musicals and in celebration of its 40th anniversary today, I thought I’d share a few thoughts on it.

Fiddler on the Roof began as a series of stories written by the “Jewish Mark Twain,” Sholem Aleichem, and published in 1894. They told of a poor milkman named Tevye and his hardships dealing with his six daughters. The stories served as the basis for several plays in both English and Yiddish as well as a 1939 film simply entitled Tevye. However, in 1964 playwright Joseph Stein, along with composer Jerry Bock and lyricist Sheldon Harnick, created what would be the most popular incarnation of this story as well as the most successful and beloved Broadway musical of its day. It was a foregone conclusion then that it would eventually become a big-screen musical (in a time when Hollywood was still making those), and so in 1970 United Artists hired director Norman Jewison to adapt the musical. Having directed such gritty, mature films such as The Thomas Crown Affair, In the Heat of the Night and The Cincinnati Kid, he seemed an odd choice to bring such family friendly fare to the screen. (Indeed, the story goes he was chosen because the producers mistakenly thought he was Jewish.) As luck would have it, however, it was an inspired choice. People tend to forget that while the first half of Fiddler is bright and joyous, the second half is darker and more melancholy, and while the tone of the second half seems more in keeping with Jewison’s sensibilities, he actually handles both halves with incredible deftness.

Jewison’s first stroke of genius was casting the Israeli actor Chaim Topol in the lead role of Tevye. The choice was somewhat controversial because, although Topol had played the part in London, the great Zero Mostel originated the role on Broadway (even winning a Tony for it) and was expected to reprise it for the film just as he had done with the reprisal of his other Tony Award-winning performance of Pseudolus the slave in 1966’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. Jewison, however, felt that Mostel’s style, though perfectly suited for the stage, would’ve been too broad and unrealistic for film. He was absolutely right. Mostel was, of course, pretty disappointed with the decision; in fact, two years later, when Jewison directed the film version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar and wanted Zero Mostel’s son Joshua to play King Herod, Mostel’s reaction was, “Tell him to get Topol’s son!” Topol is a revelation in the part of Tevye, displaying a warmth and wisdom well beyond his years (only being 35 at the time). Indeed, he was rewarded with a Best Actor nomination for his performance. Much of the rest of the cast also comes from the stage and are uniformly good (including the Oscar-nominated Leonard Frey, Norma Crane, Molly Picon, Rosalind Harris and a “pre-Starsky” Paul Michael Glaser, billed simply as “Michael Glaser”).

Jewison’s shrewdness extends beyond casting, however. Wanting to give the film an earthy “period” look (something that is commonplace now but back then was more innovative), Jewison and cinematographer Oswald Morris made the unconventional choice of shooting the entire picture with a stocking over the lens; it can even be seen in a sequence where Tevye is remembering his second oldest daughter as a little girl. Another brilliant decision on the part of Jewison was to get a relatively unknown composer named John Williams to adapt the music for the film. Most of the songs from the show are incredibly memorable (“Tradition,” “Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” “If I Were a Rich Man,” “Sunrise, Sunset”) but when Williams brings his intimate knowledge of the orchestra and bombastic personality to the melodies, helped in no small part by the virtuoso fiddling of the late Isaac Stern, the result is thrilling. Williams won his first Oscar (best adaptation score) for the work he did on the film, and it was a harbinger of things to come for the composer.

The story to Fiddler is by now quite well known. In a little village in tsarist Russia called Anatevka, a close-knit community of Jews lives in safety and solitude, trying desperately to preserve their way of life in the face of persecution and socio-political change. This struggle is typified in Tevye, who finds himself constantly warring internally over what to do regarding his five daughters and whom they wish to marry. He expresses these struggles in numerous monologues, songs and prayers to God, usually in the form of an “on the one hand, on the other hand” debate. He often finds himself in precarious situations that he likens to the image of a fiddler on a roof, a musician who is trying to scratch out a pleasant, simple tune without breaking his neck in the process. By the end of the film, Tevye’s three oldest daughters are married (one to a poor tailor, one to a Marxist revolutionary and one to a Catholic) and everyone in the village is driven out by the Cossacks. In the film’s final shot, Tevye invites the symbolic fiddler to follow him and his family to America, indicating that wherever the Jewish people go they bring their traditions, their heritage and their rich cultural and religious identity with them.

When I saw Fiddler on the Roof, I didn’t know much about Judaism and the film served as more or less my introduction to it, but I still connected with the humanity of the characters and their obstacles. One of the things that makes Fiddler work so well is, paradoxically, its universality. Although it is a distinctly Jewish story, all societies can relate to the ongoing battle to hold on to more “traditional” values in the face of an ever-changing world, and this has no doubt contributed to the film’s enduring popularity. (Norman Jewison has said that he is surprised how well the film has been received in various, culturally diverse countries.) The film tends to be absent from “100 Greatest Films” lists that critics, cinephiles and bloggers compile, but then so are a number of other films that are almost universally beloved. (I’ve never seen Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory on these lists either but I’ve yet to meet someone who doesn’t love that film.) To this day it remains a staple of community theater and high school drama productions all across the land. Topol has become indelibly associated with the character of Tevye and continued to play the role on stage for decades after the film’s release. In fact, a good friend of mine, Bob (the fellow who beautifully portrayed Tevye in the production where I was Motel), got to go see Topol in his farewell tour two years ago. After the show he told the aging actor that Tevye was one if his favorite roles and that he was soon going to be auditioning to play it yet again in another local production. Topol simply said to him, “Be good.”

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Awards, Fiction, Jewison, John Williams, Movie Tributes, Musicals, Theater, Twain

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, July 18, 2011

Centennial Tributes: Hume Cronyn Part II

Hume Cronyn

By Edward Copeland

We continue our tribute to Hume Cronyn as the decade turns to the 1950s. If you started here by mistake and missed Part I, click here. Cronyn continued to appear steadily on the various live theatrical programs on TV but only two feature films the entire decade. He definitely turned his focus to the stage, especially behind-the-scenes work. In March 1950, he directed his first Broadway play, the original comedy Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep whose cast included Fredric March. In November, he and his wife did their first New York stage collaboration when he directed her as the title character in the original drama Hilda Crane. In April 1951, he helped produce The Little Blue Light which reunited him with Burgess Meredith and had Melvyn Douglas in the cast. In August, his sole feature film of the year was released: the underrated Joseph L. Mankiewicz gem People Will Talk starring Cary Grant. Grant and Cronyn play professors at a medical school with diametrically opposed views on just about everything and Cronyn's character leads a crusade to get Grant removed from the faculty because of his unorthodox views.

Beginning Oct. 24, 1951, Cronyn and Tandy appeared on Broadway together for the first time in a play that became such a hit, that it managed to be spun off into radio, TV and movie versions with Cronyn and Tandy starring in all but the movie version because they were still enjoying the successful Broadway run at the time. The original comedy The Fourposter by Jan De Hartog is a two-character play where spouses Michael and Agnes re-enact their marriage around their four-poster bed and took place between 1890 and 1925. José

Ferrer directed the production and both he and De Hartog won Tonys (meaning it won best play). Since Cronyn and Tandy stayed with the play until May 1953, their roles in the 1952 film version directed by Irving Reis went to Rex Harrison and Lili Palmer. Its only Oscar nomination was for black-and-white cinematography. When Cronyn and Tandy finished their run in the play, Cronyn produced an NBC radio sitcom version of the play, changing the title to The Marriage, the characters' names to Ben and Liz and losing the period element. While they worked on this during the play's run, the radio show didn't begin airing until October 1953. A total of 26 episodes aired and then The Marriage made history, albeit short-lived. It moved to NBC TV where it became the first sitcom broadcast in color, though it only lasted eight episodes when, tragically, Tandy suffered a miscarriage and live broadcasts ceased never to start again. The Fourposter would come back throughout Cronyn and Tandy's careers though in the form of revivals and tours (including a 15-performance Broadway revival in 1955). In fact, in the summer of 1955, Cronyn and Tandy performed The Fourposter on an episode of Producers' Showcase and Tandy received her first Emmy nomination for actress in a single performance.

Ferrer directed the production and both he and De Hartog won Tonys (meaning it won best play). Since Cronyn and Tandy stayed with the play until May 1953, their roles in the 1952 film version directed by Irving Reis went to Rex Harrison and Lili Palmer. Its only Oscar nomination was for black-and-white cinematography. When Cronyn and Tandy finished their run in the play, Cronyn produced an NBC radio sitcom version of the play, changing the title to The Marriage, the characters' names to Ben and Liz and losing the period element. While they worked on this during the play's run, the radio show didn't begin airing until October 1953. A total of 26 episodes aired and then The Marriage made history, albeit short-lived. It moved to NBC TV where it became the first sitcom broadcast in color, though it only lasted eight episodes when, tragically, Tandy suffered a miscarriage and live broadcasts ceased never to start again. The Fourposter would come back throughout Cronyn and Tandy's careers though in the form of revivals and tours (including a 15-performance Broadway revival in 1955). In fact, in the summer of 1955, Cronyn and Tandy performed The Fourposter on an episode of Producers' Showcase and Tandy received her first Emmy nomination for actress in a single performance.Throughout the 1950s, movies didn't see much of Cronyn as he kept busy with productions on TV and the stage. Other than People Will Talk, the only other feature film IMDb lists for that decade is something called Crowded Paradise in 1956 of which IMDb contains the bare minimum of information. Part of the reason for this may have been that Hume Cronyn may have been one of the few people in this country's sordid history of the blacklist to keep himself busy so constantly that he didn't know he'd been blacklisted. Another reason was that it seemed inconceivable to him since he was never very active politically, never called before HUAC or ever attended any "suspect" meetings. It turned out eventually that his particularly puzzling blacklisting was because he had hired people who were blacklisted, not that he knew or even if he did he would have cared. Cronyn didn't suffer too much because by the time he became aware of his status, others had started breaking the blacklist anyway by doing what got him on the list in the first place.

In December 1953, he and Norman Lloyd inaugurated The Phoenix Theatre by co-directing and co-starring in Madam, Will You Walk? which also featured Tandy. Interestingly, the play with the same opening and closing dates is listed in both the Internet Broadway Database and the Internet Off-Broadway Database and I can find nothing in a quick look to settle where it belongs — not even number of seats or an address. Cronyn didn't spend all his stage time in New York though, he started doing a lot of tours, including a series of concert readings with Tandy in 1954 called Face to Face which were later turned into a recording. In 1955, Cronyn hit The Great White Way with Tandy twice: the aforementioned short revival of The Fourposter and an original farce by Roald Dahl called The Honeys. Sometime that year he had time to act in A Day By The Sea at the American National Theatre and Academy Theatre — and that's not counting 13 TV acting jobs between 1953 and 1955.

The remainder of the decade was even more dominated by work on television, to the exclusion of actual stage work in 1956 though he did make the first of two appearances (the second coming in 1958) on Alfred Hitchcock Presents. He returned to Broadway in 1957 to direct longtime friend Karl Malden in The Egghead. Cronyn and Tandy also toured several cities across the U.S. in 1957 with the new comedy The Man in the Dog Suit ahead of its Broadway premiere in 1958. Cronyn followed the same pattern in 1958, touring with Tandy and other actors in a production he both starred in and directed called Triple Play that consisted of three one-act plays and a monologue, which was considered an original one act play when it opened on Broadway in 1959, though it was written by the long dead Anton Chekhov. The one acts were Tennessee Williams' Portrait of a Madonna, two by Sean O'Casey: A Pound on Demand and Bedtime Story, and the Chekhov monologue which Cronyn performed Some Comments on the Harmful Effects of Tobacco. Cronyn and Tandy closed out the 1950s with a television movie adaptation of Somerset Maugham's novel The Moon and Sixpence with a cast led by Laurence Olivier and featuring Judith Anderson, Denholm Elliott, Geraldine Fitzgerald and Jean Marsh. IMDb actually had a link to the original Time magazine review of it.

As the 1960s began, movies began to enter Cronyn's life again and television receded a bit, mainly because the popularity of programs that televised plays were on the wane. Theater maintained its prominence in his life, and he started to see some award recognition for it. In the fall of 1960, he played Louis Howe to Ralph Bellamy's FDR and Greer Garson's Eleanor when Sunrise at Campobello was released. In early 1961, Cronyn opened on Broadway as Jimmie Luton, the main character of the new farce Big Fish, Little Fish by Hugh Wheeler, his first work on Broadway though he'd go on to write the books for A Little Night Music, Candide and Sweeney Todd, winning a Tony for all three. Cronyn was directed in Big Fish, Little Fish by John Gielgud, who won the Tony for best direction in a play. Cronyn received his first Tony nomination as actor in a play and the cast included Jason Robards, George Grizzard (Tony nominee for featured actor in a play) and Martin Gabel (Tony winner for featured actor in a play). The show proved to be such a success that

the following year Cronyn made his London stage debut when he played Jimmie Luton again when Big Fish, Little Fish opened at the Duke of York's Theatre. While overseas he helped his friend Joe Mankiewicz by taking the part of Sosigenes in the out-of-control Cleopatra, which finally opened in 1963. When he was back in the U.S. in 1963, he helped inaugurate the premiere season of the Tyrone Guthrie's Minnesota Theatre Company at the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis by appearing in three productions: Harpagon in Moliere's The Miser, Tchebutkin in Chekhov's The Three Sisters and Willy Loman in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. In 1964, Cronyn scored a coup — playing Polonious in a Broadway production of Hamlet starring Richard Burton and nearly stealing the show from the melancholy Dane. Directed by Gielgud as if the company were in rehearsal clothes, it also was filmed and aired on TV the same year. Cronyn's performance won him a Tony for featured actor in a play. Here is a YouTube clip of Cronyn and Burton at work.

the following year Cronyn made his London stage debut when he played Jimmie Luton again when Big Fish, Little Fish opened at the Duke of York's Theatre. While overseas he helped his friend Joe Mankiewicz by taking the part of Sosigenes in the out-of-control Cleopatra, which finally opened in 1963. When he was back in the U.S. in 1963, he helped inaugurate the premiere season of the Tyrone Guthrie's Minnesota Theatre Company at the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis by appearing in three productions: Harpagon in Moliere's The Miser, Tchebutkin in Chekhov's The Three Sisters and Willy Loman in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. In 1964, Cronyn scored a coup — playing Polonious in a Broadway production of Hamlet starring Richard Burton and nearly stealing the show from the melancholy Dane. Directed by Gielgud as if the company were in rehearsal clothes, it also was filmed and aired on TV the same year. Cronyn's performance won him a Tony for featured actor in a play. Here is a YouTube clip of Cronyn and Burton at work.A few months after his triumph in Hamlet, Cronyn returned to the Broadway stage with Tandy in tow in The Physicists opposite Robert Shaw. Two days after that show closed, Cronyn was one of the producers of the play Slow Dance on the Killing Ground, which earned Cronyn his third Tony nomination, his first as producer of a best play nominee. In late 1966, Cronyn and Tandy created the roles of Tobias and Agnes in a bona fide classic: Edward Albee's Pulitzer Prize-winning A Delicate Balance and Cronyn received another Tony nomination as actor in a play as Tobias. In 1967, Cronyn took A Delicate Balance on tour. He stayed on the road performing in productions in L.A. and Ontario in 1968 and 1969. He squeezed out two films in 1969: Elia Kazan's adaptation of his own novel The Arrangement and Norman Jewison's comedy Gaily, Gaily starring Beau Bridges. Somehow, in this busiest of schedules, Cronyn also had to recover from a bout of cancer that cost him one of his eyes in 1969 and left him with a glass eye for the rest of his life.

Now, we do draw near the end of the theatrical careers of Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy, but Cronyn wraps it up very actively and the couple will follow it up with prolific television and film work. First in 1977, Cronyn co-produced with Mike Nichols the two-person play The Gin Game for he and Tandy to star in and Nichols to direct. After an initial tryout in Long Wharf, Conn., they moved to Broadway to much success, running 517 performances. Cronyn received Tony and Drama Desk nominations for both best actor and best play while Tandy won both those awards for best actress. The play's author, D.L. Coburn, won the Pulitzer. Nichols received play and directing nominations from both groups. Cronyn and Tandy then took The Gin Game on tour, not just in the United States but throughout Canada, the United

Kingdom and some cities in the Soviet Union as well through 1979. Then, they made a television version of the play that aired in a version made for Showtime in 1981. During this time period, dating back to 1977, Cronyn also was collaborating with writer Susan Cooper on what would become Cronyn and Tandy's penultimate stage project. Before they got to that, Cronyn managed to return to feature films three times and took Tandy along on two of them. They had small parts in the odd ensemble assembled for John Schlesinger's wacky satire Honky Tonk Freeway, Cronyn re-teamed alone with his Parallax View director Alan J. Pakula for an economic thriller called Rollover starring Jane Fonda and Kris Kristofferson and then he and Tandy had brief roles as the parents of the one-of-a-kind Jenny Fields (Glenn Close) in the movie adaptation of The World According to Garp.

Kingdom and some cities in the Soviet Union as well through 1979. Then, they made a television version of the play that aired in a version made for Showtime in 1981. During this time period, dating back to 1977, Cronyn also was collaborating with writer Susan Cooper on what would become Cronyn and Tandy's penultimate stage project. Before they got to that, Cronyn managed to return to feature films three times and took Tandy along on two of them. They had small parts in the odd ensemble assembled for John Schlesinger's wacky satire Honky Tonk Freeway, Cronyn re-teamed alone with his Parallax View director Alan J. Pakula for an economic thriller called Rollover starring Jane Fonda and Kris Kristofferson and then he and Tandy had brief roles as the parents of the one-of-a-kind Jenny Fields (Glenn Close) in the movie adaptation of The World According to Garp.Susan Cooper also hailed from England, but came to the U.S. when she married an American, though the marriage didn't work out. She primarily wrote novels and children's books until she developed an interest in

playwriting and somehow began collaboration with Cronyn a long-gestating work called Foxfire about the end of an Appalachian family's way of life. It added to Cronyn's resume because not only was he co-author of the play, he, Cooper and Jonathan Holtzman wrote lyrics for songs for which Holtzman wrote the music, though it wasn't strictly a musical. After debuting first at The Stratford Festival in Stratford, Ontario and The Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis, it opened on Broadway in November 1982. Playing Cronyn and Tandy's characters' son in the play was Keith Carradine. Tandy won both the Tony and the Drama Desk awards for best actress in a play. Five years later, it aired on CBS where Tandy again won outstanding actress, this time in a miniseries or special. Cronyn was nominated as outstanding actor and he and Cooper received a solo writing nomination. The movie itself was nominated as outstanding drama or comedy special and John Denver took Carradine's role. Below is a YouTube clip of the TV movie.

playwriting and somehow began collaboration with Cronyn a long-gestating work called Foxfire about the end of an Appalachian family's way of life. It added to Cronyn's resume because not only was he co-author of the play, he, Cooper and Jonathan Holtzman wrote lyrics for songs for which Holtzman wrote the music, though it wasn't strictly a musical. After debuting first at The Stratford Festival in Stratford, Ontario and The Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis, it opened on Broadway in November 1982. Playing Cronyn and Tandy's characters' son in the play was Keith Carradine. Tandy won both the Tony and the Drama Desk awards for best actress in a play. Five years later, it aired on CBS where Tandy again won outstanding actress, this time in a miniseries or special. Cronyn was nominated as outstanding actor and he and Cooper received a solo writing nomination. The movie itself was nominated as outstanding drama or comedy special and John Denver took Carradine's role. Below is a YouTube clip of the TV movie.After having seen Foxfire, Cronyn's co-star in Rollover, Jane Fonda, asked if he and Susan Cooper would adapt the novel The Dollmaker into a script for a TV movie for her. They did and received Emmy nominations for writing the 1984 telefilm and Fonda won outstanding actress in a miniseries or special for it. It was (and remains) only the second time Fonda appeared in a TV production, the previous one being when she was just starting out in 1961. Cronyn started heading back to the cinema in the 1984 thriller Impulse and Richard Pryor's surprise relative who gives him the challenge of spending $30 million in 30 days if he wants to inherit his vast fortune of $300 million in the umpteenth remake of Brewster's Millions in 1985. However, Cronyn, with Tandy beside him, had another 1985 release that really made the veteran actors stars to an entirely new generation.

Joining Cronyn and Tandy as the leads of Ron Howard's Cocoon were Wilford Brimley, Maureen Stapleton, Gwen Verdon, Jack Gilford, Herta Ware and Don Ameche, who took home an Oscar for supporting actor for

the film even though he wasn't even the best supporting actor in the film. A sci-fi comedy and meditation on aging and dying, it was made when Big Blue was a swimming pool loaded with extra-terrestrial magic making the seniors horny instead of a pill for erectile dysfunction. Cronyn and Tandy had particularly good moments as the pool awakened his character's libido and his wandering eye, reminding his wife of his younger days when he was far from faithful. Of course, they had to make an awful sequel, but to have that a big a hit with that many older actors as leads was quite something. It's not like Steve Guttenberg was the draw. The following year, 1986, Cronyn and Tandy were honored together as that year's batch of Kennedy Center honorees alongside Lucille Ball, Ray Charles, Yehudi Menuhin and Antony Tudor. Cronyn and Tandy would appear in two more feature films togethers (three counting the Cocoon sequel): 1987's *batteries not included and 1994's Camilla, Tandy's final film released after her death. Among the many televison and feature films we won't still talk about that Cronyn would go on to make the most notable were The Pelican Brief and Marvin's Room.

the film even though he wasn't even the best supporting actor in the film. A sci-fi comedy and meditation on aging and dying, it was made when Big Blue was a swimming pool loaded with extra-terrestrial magic making the seniors horny instead of a pill for erectile dysfunction. Cronyn and Tandy had particularly good moments as the pool awakened his character's libido and his wandering eye, reminding his wife of his younger days when he was far from faithful. Of course, they had to make an awful sequel, but to have that a big a hit with that many older actors as leads was quite something. It's not like Steve Guttenberg was the draw. The following year, 1986, Cronyn and Tandy were honored together as that year's batch of Kennedy Center honorees alongside Lucille Ball, Ray Charles, Yehudi Menuhin and Antony Tudor. Cronyn and Tandy would appear in two more feature films togethers (three counting the Cocoon sequel): 1987's *batteries not included and 1994's Camilla, Tandy's final film released after her death. Among the many televison and feature films we won't still talk about that Cronyn would go on to make the most notable were The Pelican Brief and Marvin's Room.

In 1986, Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy appeared in their last Broadway show, fittingly together. The Petition was a two-person play and earned each of them Tony nominations. In 1994, they received the very first Tony Awards ever given for lifetime achievement. It was just a few months before Tandy's death. Though their stage work considerably lessened and Broadway work ceased, movie and TV worked soared. Cronyn became a regular presence at the Emmys, being nominated five times between 1990 and 1998 and winning three times. He won lead actor for HBO's Age-Old Friends, which allowed him to act opposite daughter Tandy Cronyn. He won that, his first Emmy, the same year that Tandy won the best actress Oscar for Driving Miss Daisy. During this time, the pair went on 60 Minutes and had fun putting Mike Wallace on.

Cronyn earned two 1992 Emmy nominations, one for lead actor in a miniseries or special in Christmas on Division Street and one for supporting actor in a miniseries or special for Neil Simon's Broadway Bound, which he won. His third win was bittersweet. Written by Susan Cooper, To Dance With the White Dog co-starred Tandy who also was nominated, and dealt with a widower working through the grief over the loss of his wife. The awards ceremony took place shortly after Tandy's death. Cronyn's final Emmy nomination came for supporting actor in a miniseries or special for Showtime's version of 12 Angry Men in 1998. Two years after Tandy's death, Cronyn married Susan Cooper who remained his wife until his death in 2003. The only other writing project they worked on together was a screenplay adaptation of Anne Tyler's novel Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant, which they didn't complete. Cronyn completed one other bit of writing: his memoir A Terrible Liar which was published in 1991. Hume Cronyn only missed his own centennial by eight years, but with as much as he accomplished, he might as well have lived 200 years. It helps when you have a partner as simpatico to you as Jessica Tandy was to him.

SOURCES: Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy: A Register of Their Papers in the Library of Congress,, The Digital Deli Too, thelostland.com, film reference.com, Internet Accuracy Project, Superiorpics.com, Wikipedia, Lortel Archives: Internet Off-Broadway Database, The Internet Broadway Database and the Internet Movie Database.

Tweet

Labels: Albee, Beau Bridges, Bellamy, blacklist, Burgess Meredith, Cary, Ferrer, Fredric March, Garson, Gielgud, Glenn Close, J. Fonda, Jewison, K. Carradine, Kazan, Malden, Mankiewicz, Nichols, Olivier, Robards

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, July 01, 2009

Karl Malden (1912-2009)

In the flood of recent celebrity passings, one would wish that TV would grant an appropriate amount of time to noting the career of Oscar winner Karl Malden, who died today at 97. Certainly he's been in the public eye a lot longer than others. He may not have set records like others did, but I guess your death only deserves real notice if you managed to become tabloid fodder in your lifetime first. Malden didn't have that foresight. He just did his job and did it damn well, working up until the year 2000 and making public appearances well past that.

Malden made his Broadway debut in 1937 in the original production of Golden Boy. While his film career began in 1940, he continued to appear on Broadway until 1957, including the original productions of Key Largo, All My Sons, The Desperate Hours and, of course, A Streetcar Named Desire. Amazingly, he never earned a Tony nomination.

His first notable film came with 1947's Kiss of Death. Though occasionally he got to show a darker side, he usually was the on the side of right such as the police commander in Otto Preminger's Where the Sidewalk Ends. In 1951, he got to repeat his Broadway role as Mitch in A Streetcar Named Desire and was given the Oscar for his performance.

He worked with Hitchcock in 1953's I Confess! In 1954, he reunited with director Elia Kazan and co-star Marlon Brando playing Father Barry and earning a second Oscar nomination in On the Waterfront. Kazan and Tennessee Williams brought out his darker side in 1956 when he played the oddly overprotective husband in Baby Doll.

Brando brought him along when he directed his Western One-Eyed Jacks. He played the no-nonsense warden in Birdman of Alcatraz the same year he was part of the all-star cast of How the West was Won. That same year, he even went musical, playing Herbie in the film version of Gypsy.

He usually dealt the cards in Norman Jewison's The Cincinnati Kid. While George C. Scott steamrolled over the screen as Patton, Malden was at his side as Gen. Omar Bradley.

As the 1970s came in, Malden found most of his work on television (aside from disaster flicks such as Beyond the Poseidon Adventure and Meteor). He had a successful run as Detective Lt. Mike Stone, originally opposite Michael Douglas, on The Streets of San Francisco, which earned him four consecutive Emmy nominations.

One of my favorite TV roles of Malden's was one which won him an Emmy as the father in-law in the miniseries Fatal Vision, who at first defends his son-in-law in the murders of his daughter and grandchildren before coming to believe him guilty.

Of course, for many his most famous role will come from a TV commercial as American Express pitchman in the 1970s with the famous tagline, "Don't leave home without it."

His last screen appearance, appropriate given the large numbers of roles where he played members of the clergy, was as a minister on The West Wing in 2000. He also served once as the president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

He did achieve one record that few ever accomplish: He was married to the same woman for 70 years. RIP Mr. Malden.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Brando, George C. Scott, Hitchcock, Jewison, Kazan, M. Douglas, Malden, Obituary, Preminger, Television, Tennessee Williams, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE