Monday, May 21, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part III

By Edward Copeland

It isn't often that a masterpiece of literature begets a masterpiece of cinema yet both retain distinct identities all their own, but that's the case with In Cold Blood, Truman Capote's "nonfiction novel" and Richard Brooks' stunning film adaptation of his book. Capote often gets credit for inventing the genre of adapting the techniques of a novelist to that of straight reporting, but earlier attempts existed — Capote's stood out because In Cold Blood 's excellence made everyone forget any other examples (at least until more than a decade later when Norman Mailer added his own brilliant take on the genre with The Executioner's Song). Brooks, with his job as a crime reporter in his past, on the surface appears to follow Capote's approach, but the director, forever the activist, skips the objectivity that Capote tried to evoke in his book. Brooks didn't want to minimize the horror of the crime that occurred at the Clutter farm in Holcomb, Kans., but he also wanted to humanize the killers, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. In a way, Brooks' film inspired the path for the two films made decades later telling the story of Capote's writing of the book and his getting to know the killers first-hand as they waited on Death Row. Even today, Brooks' 1967 film remains more powerful and better made than the two more recent tales. Undoubtedly, In Cold Blood remains Brooks' greatest film. If you got here before reading either Part I or Part II of this tribute, click on the respective links.

The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call "out there." Some seventy miles east of the Colorado border, the countryside, with its hard blue skies and desert-clear air, has an atmosphere that is rather more Far West than Middle West. The local accent is barbed with a prairie twang, a ranch-hand nasalness, and the men, many of them, wear narrow frontier trousers, Stetsons, and high-heeled boots with pointed toes. The land is flat, and the views are awesomely extensive; horses, herds of cattle, a white cluster of grain elevators rising as gracefully as Greek temples are visible long before a traveler reaches them.

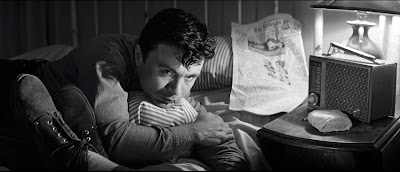

Capote begins his book with that paragraph in the first chapter titled The Last to See Them Alive. Brooks begins the film of In Cold Blood introducing us to The Last to See Them Alive in the forms of Robert Blake as newly paroled inmate Perry Smith and Scott Wilson as an acquaintance he met in prison who had been freed earlier, Dick Hickok. Brooks gives Blake — and the movie — a memorable entrance, especially thanks to his decision to go against the grain of the time and film in black-and-white Panavision. We see a bus driving down a two-lane highway, passing signs showing the distance to different Kansas towns, including the horrific Olathe. On the bus, a young female stumbles down the aisle to get a closer look at the pair of pointed-toe cowboy boots with buckles on its heels before creeping back. The shadowy man who wears the boots also has a guitar strung around his neck. A flame suddenly illuminates Robert Blake's face as he lights a cigarette and Quincy Jones' ominous yet jazzy score kicks in to start the credits. The sequence not only sets the tone for the film that follows, it also introduces us to the movie's most important participant — cinematographer Conrad L. Hall (though he didn't need to use the L. yet since his son, Conrad W. Hall, wasn't old enough to follow his dad into the business).

The movie spends its opening minutes introducing us to the soft-spoken Perry and getting him hooked up with Dick. Whereas Blake's Perry comes off as a puppy repeatedly kicked by his owner, Scott Wilson portrays Hickok as a cocky, livewire and a chatterbox — and Brooks gives him great lines, especially in the scenes where he and Blake drive around. "Ever seen a millionaire fry in the electric chair? Hell, no. There's two kinds of laws, one for the rich and one for the poor," Dick imparts as wisdom to Perry. When the two buy supplies for the planned robbery of the Clutter farm, Dick shoplifts some razorblades for no good reason, leading Perry to chastise him for taking such a risk for something so small. "That was stupid — stealin' a lousy pack of razor blades! To prove what?" Perry asks. Smiling, Dick replies, "It's the national pastime, baby, stealin' and cheatin'. If they ever count every cheatin' wife and tax chiseler, the whole country would be behind prison walls." Though in the two recent biographical films about Truman Capote's research into the case, it's strongly implied that Capote at least developed a crush on Smith and that Perry may have been gay. In Cold Blood never explicltly claims that Perry Smith was gay, but throughout the film Dick taunts him by

calling him "honey," "baby" or something along those lines. Hickock on the other hand chases every skirt he gets near and during the robbery/murder, Perry intervenes to stop Dick from raping the Clutters' 16-year-old daughter Nancy (Brenda Currin). Wilson made his first two feature films in 1967 and he landed roles in two of the biggest — this one and the eventual Oscar winner for best picture, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night. The jaws of younger readers should hit the floor when they see Wilson's great work here and it slowly dawns on them that playing Dick Hickok is a younger incarnation of Herschel on AMC's The Walking Dead. When Perry and Dick do get together, they meet at Dick's father's house where Dick tries to aid his old man, who's slowly losing his battle with terminal cancer. (Veteran character actor Jeff Corey, who co-starred in the Brooks-scripted 1947 classic Brute Force, plays the elder Hickock.) Contrasting Capote's take with Brooks' version fascinates in the ways the works reflect each other yet, like a mirror, many things appear on the opposite side. The book introduces its readers to the Clutter family first before Perry and Dick enter the story (by name anyway). Brooks' screenplay reverses the order, beginning with the killers then letting us meet the Kansas family. However, both aim to draw parallels between the victims and their eventual murderers. "That morning an apple and a glass of milk were enough for him; because

calling him "honey," "baby" or something along those lines. Hickock on the other hand chases every skirt he gets near and during the robbery/murder, Perry intervenes to stop Dick from raping the Clutters' 16-year-old daughter Nancy (Brenda Currin). Wilson made his first two feature films in 1967 and he landed roles in two of the biggest — this one and the eventual Oscar winner for best picture, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night. The jaws of younger readers should hit the floor when they see Wilson's great work here and it slowly dawns on them that playing Dick Hickok is a younger incarnation of Herschel on AMC's The Walking Dead. When Perry and Dick do get together, they meet at Dick's father's house where Dick tries to aid his old man, who's slowly losing his battle with terminal cancer. (Veteran character actor Jeff Corey, who co-starred in the Brooks-scripted 1947 classic Brute Force, plays the elder Hickock.) Contrasting Capote's take with Brooks' version fascinates in the ways the works reflect each other yet, like a mirror, many things appear on the opposite side. The book introduces its readers to the Clutter family first before Perry and Dick enter the story (by name anyway). Brooks' screenplay reverses the order, beginning with the killers then letting us meet the Kansas family. However, both aim to draw parallels between the victims and their eventual murderers. "That morning an apple and a glass of milk were enough for him; because he touched neither coffee or tea, he was accustomed to begin the day on a cold stomach. The truth was he opposed all stimulants, however gentle. He did not smoke, and of course he did not drink; indeed, he had never tasted spirits, and was inclined to avoid people who had — a circumstance that did not shrink his social circle as much as might be supposed, for the center of that circle was supplied by the members of Garden City's First Methodist Church, a congregation totaling seventeen hundred, most of whom were as abstemious as Mr. Clutter could desire," Capote described the Clutter patriarch. A few pages later in the first chapter, Perry Smith makes his entrance into Capote's book. "Like Mr. Clutter, the young man breakfasting in a cafe called the Little Jewel never drank coffee. He preferred root beer. Three aspirin, cold root beer, and a chain of Pall Mall cigarettes — that was his notion of a proper "chow-down." Sipping and smoking, he studied a map spread on the counter before him — a Phillips 66 map of Mexico — but it was difficult to concentrate, for he was expecting a friend, and the friend was late. He looked out a window at the silent small-town street, a street he had never seen until yesterday. Still no sign of Dick," Capote wrote. Brooks uses a visual link to draw victim and killer together, showing Herbert Clutter (John McLiam) performing his morning shave. As Clutter leans into the sink to rinse the remaining shaving cream from his face, the face that rises up and looks in the mirror sees Perry Smith, excising his excess whiskers as well.

he touched neither coffee or tea, he was accustomed to begin the day on a cold stomach. The truth was he opposed all stimulants, however gentle. He did not smoke, and of course he did not drink; indeed, he had never tasted spirits, and was inclined to avoid people who had — a circumstance that did not shrink his social circle as much as might be supposed, for the center of that circle was supplied by the members of Garden City's First Methodist Church, a congregation totaling seventeen hundred, most of whom were as abstemious as Mr. Clutter could desire," Capote described the Clutter patriarch. A few pages later in the first chapter, Perry Smith makes his entrance into Capote's book. "Like Mr. Clutter, the young man breakfasting in a cafe called the Little Jewel never drank coffee. He preferred root beer. Three aspirin, cold root beer, and a chain of Pall Mall cigarettes — that was his notion of a proper "chow-down." Sipping and smoking, he studied a map spread on the counter before him — a Phillips 66 map of Mexico — but it was difficult to concentrate, for he was expecting a friend, and the friend was late. He looked out a window at the silent small-town street, a street he had never seen until yesterday. Still no sign of Dick," Capote wrote. Brooks uses a visual link to draw victim and killer together, showing Herbert Clutter (John McLiam) performing his morning shave. As Clutter leans into the sink to rinse the remaining shaving cream from his face, the face that rises up and looks in the mirror sees Perry Smith, excising his excess whiskers as well.

The biggest difference between the book and the movie came with Brooks' introduction of a Truman Capote surrogate, a magazine reporter named Jensen, who travels to Holcomb to cover the case. Jensen isn't played in a way similar to the extremely distinctive Capote — such as the way that won Philip Seymour Hoffman an Oscar for Capote, that Toby Jones played even better in Infamous or that Tru himself played best of all as Lionel Twain in Neil Simon's 1976 mystery spoof Murder By Death. Brooks wrote the Jensen character straight (no pun intended) and conventionally, even giving him a narrator's function at times. He doesn't precisely follow how Capote researched the story though because Capote didn't arrive in Kansas until after Smith and Hickok had been apprehended. In the movie, Jensen arrives almost from the beginning of the investigation. For the role of Jensen, Brooks cast another veteran character actor — Paul Stewart, whose first credited screen role was the butler Raymond in Citizen Kane. His 42-year film and television career ended in 1983 with an episode of Remington Steele and he died three years later, a month shy of his 88th birthday. After starting with Kane, a few of Stewart's eclectic highlights included Champion, Brooks' Deadline-U.S.A., The Bad and the Beautiful, Kiss Me Deadly, Hell on Frisco Bay, King Creole, Opening Night, Revenge of the Pink Panther,

S.O.B. and appearances on nearly every episodic police or detective show between the 1950s and the 1970s, including The Mod Squad. The Jensen character arrives around the same time that the Kansas Bureau of Investigation joins the case led by John Forsythe as Alvin Dewey, what may be Forsythe's best performance. Brooks gives him a lot of speeches — and some come off as less pristine than others, but Forsythe succeeds at selling most of them. Forsythe gets so identified with Dynasty or as a voice on Charlie's Angels that I think people forget that he really act when the material was there for him as it was here or in the short-lived and underrated Norman Lear sitcom The Powers That Be and having fun with Hitchcock in The Trouble With Harry (though no one could help Topaz much). He also was a replacement performer of one of the major roles in Arthur Miller's All My Sons on Broadway. Granted, didn't see him, but he had to show some chops to land that one. Of his filmed work though, I think In Cold Blood stands as the best. Sure, this speech reads as overwrought, but he pulled it off as he delivered it to Jensen. "Someday, someone will have to explain the motive of a newspaper to me. First, you scream, 'Find the bastards.' Till we do find 'em, you want to get us fired. When we find 'em, you accuse us of brutality. Before we go

S.O.B. and appearances on nearly every episodic police or detective show between the 1950s and the 1970s, including The Mod Squad. The Jensen character arrives around the same time that the Kansas Bureau of Investigation joins the case led by John Forsythe as Alvin Dewey, what may be Forsythe's best performance. Brooks gives him a lot of speeches — and some come off as less pristine than others, but Forsythe succeeds at selling most of them. Forsythe gets so identified with Dynasty or as a voice on Charlie's Angels that I think people forget that he really act when the material was there for him as it was here or in the short-lived and underrated Norman Lear sitcom The Powers That Be and having fun with Hitchcock in The Trouble With Harry (though no one could help Topaz much). He also was a replacement performer of one of the major roles in Arthur Miller's All My Sons on Broadway. Granted, didn't see him, but he had to show some chops to land that one. Of his filmed work though, I think In Cold Blood stands as the best. Sure, this speech reads as overwrought, but he pulled it off as he delivered it to Jensen. "Someday, someone will have to explain the motive of a newspaper to me. First, you scream, 'Find the bastards.' Till we do find 'em, you want to get us fired. When we find 'em, you accuse us of brutality. Before we go into court, you give them a trial in the newspaper, When we finally get a conviction, you want to save 'em by proving they were really crazy in the first place. All of which adds up to one thing — you've got the killers," Dewey tells Jensen as he's taking down to the basement of the Clutter house. Dewey also serves as Mr. Exposition, explaining why these two numbskulls just out of prison would decide to go to this one particular farmhouse and rob this family, making sure to "leave no witnesses," even though Dick and Perry only gain $40 from the crime. A fellow investigator asks Dewey if Clutter might have been rich and Alvin sort of laughs knowingly. "Ahh — the old Kansas myth. Every farmer with a big spread is supposed to have a secret black box with lots of money in it." It isn't until the ending that you realize the Brooks gave Dewey some of that dialogue because he's supposed to symbolize the parts of the system that disgust him. Brooks ardently opposed capital punishment and he made no secret that he wanted the ending to make clear that it was murder. At Smith's hanging, another reporter asks Dewey about how much the executioner makes. "Three hundred dollars a man," Dewey answers. "Who does he work for? Does he have a name?" the reporter follows up and then poor John Forsythe has to deliver the clunkiest line of dialogue in the entire film. "Yes. We the people." Earlier, it had been the topic of discussion between Jensen and an imprisoned Hickock.

into court, you give them a trial in the newspaper, When we finally get a conviction, you want to save 'em by proving they were really crazy in the first place. All of which adds up to one thing — you've got the killers," Dewey tells Jensen as he's taking down to the basement of the Clutter house. Dewey also serves as Mr. Exposition, explaining why these two numbskulls just out of prison would decide to go to this one particular farmhouse and rob this family, making sure to "leave no witnesses," even though Dick and Perry only gain $40 from the crime. A fellow investigator asks Dewey if Clutter might have been rich and Alvin sort of laughs knowingly. "Ahh — the old Kansas myth. Every farmer with a big spread is supposed to have a secret black box with lots of money in it." It isn't until the ending that you realize the Brooks gave Dewey some of that dialogue because he's supposed to symbolize the parts of the system that disgust him. Brooks ardently opposed capital punishment and he made no secret that he wanted the ending to make clear that it was murder. At Smith's hanging, another reporter asks Dewey about how much the executioner makes. "Three hundred dollars a man," Dewey answers. "Who does he work for? Does he have a name?" the reporter follows up and then poor John Forsythe has to deliver the clunkiest line of dialogue in the entire film. "Yes. We the people." Earlier, it had been the topic of discussion between Jensen and an imprisoned Hickock.DICK: Perry's the only one talking against capital punishment.

JENSEN: Don't tell me you're for it.

DICK: Hell, hangin' only getting revenge. What's wrong with revenge? I've been revenging myself all my life.

Part of the film's brilliance stems from the way Brooks structures the scenes detailing the crime itself. Toward the beginning of the movie, he presents what probably remains the greatest sequence of his directing career without actually showing the murder. Then, as the film winds down, he shows us what we didn't see and it's horrifying. Through a window of the farmhouse, we can see Nancy kneeling beside her bed saying her prayers. At that moment, it isn't made clear who could be seeing that — are Dick and Perry outside her window or are we simply the voyeurs right then? A split second later we spot Dick and Perry still sitting in the car beneath the cover of night. I guess it was us. The discordant sound of a doorbell suddenly fills the soundtrack and the viewer realizes he or she has moved inside the Clutter house — and sunlight shines through the windows. The camera tracks slowly around the furniture of the living room as it makes its way toward the front door. A woman and some other people open the door calling out for the Clutters. We faintly hear church bells tolling and the visitors wear their Sunday best. The woman continues to call out the Clutters by their first names as she ascends the stairs to the second floor. The film cuts quickly to the house's

exterior just as we hear the woman let out a horrified scream. Coming on the heels of The Professionals, it's as if somehow Brooks transformed himself from a competent director and damn good writer into a master of both. I don't know if the fact he had Conrad Hall working as his d.p. on both films made any sort of difference or if that proved to be just fortuitous, but that one-two punch sealed Brooks' artistic reputation forever beyond what respect he'd earned before. I've never been fortunate enough to see In Cold Blood on the big screen and allow Hall's haunting and beautiful mix of light and shadow to bathe me in its glow, but I did get the next best thing when in 1993 at the Inwood Theater in Dallas I saw Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy and Stuart Samuels' documentary Visions of Light, a film devoted to the art of cinematography and highlighting some of its greatest practitioners and their best moments. One of the highlighted scenes comes from In Cold Blood when Robert Blake as Perry gives an emotional monologue about his father in his prison cell while he looks out the window at the rain coming down. The reflection of the raindrops cast shadows on Blake's face that make it appear as if he's crying. The moment stuns in its beauty — even when you learn that as so many say, accidents ends up producing some of the best parts of film. Hall admitted it hadn't been planned but the humidity in the prison set had pumped up the window's perspiration so much (as well as everyone else's) that's how the magic happened. Thankfully, YouTube had that clip.

exterior just as we hear the woman let out a horrified scream. Coming on the heels of The Professionals, it's as if somehow Brooks transformed himself from a competent director and damn good writer into a master of both. I don't know if the fact he had Conrad Hall working as his d.p. on both films made any sort of difference or if that proved to be just fortuitous, but that one-two punch sealed Brooks' artistic reputation forever beyond what respect he'd earned before. I've never been fortunate enough to see In Cold Blood on the big screen and allow Hall's haunting and beautiful mix of light and shadow to bathe me in its glow, but I did get the next best thing when in 1993 at the Inwood Theater in Dallas I saw Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy and Stuart Samuels' documentary Visions of Light, a film devoted to the art of cinematography and highlighting some of its greatest practitioners and their best moments. One of the highlighted scenes comes from In Cold Blood when Robert Blake as Perry gives an emotional monologue about his father in his prison cell while he looks out the window at the rain coming down. The reflection of the raindrops cast shadows on Blake's face that make it appear as if he's crying. The moment stuns in its beauty — even when you learn that as so many say, accidents ends up producing some of the best parts of film. Hall admitted it hadn't been planned but the humidity in the prison set had pumped up the window's perspiration so much (as well as everyone else's) that's how the magic happened. Thankfully, YouTube had that clip.It must be said how good a performance Blake gives while at the same time acknowledging that it can't be viewed the way many of us assessed it originally. When a Naked Gun movie pops up and you see O.J. Simpson play an idiot and constantly take a beating, somehow that's OK. When you watch In Cold Blood again and see Blake give such a convincing and chilling performance as a mass murderer (especially when Forsythe's Alvin Dewey engages him in conversation during the ride to jail and Perry tells him, "I thought Mr. Clutter was a very nice gentleman. I thought it right till the moment I cut his throat."), you can't help but recall that a few decades later, the actor stood trial and received an acquittal for killing his wife. It doesn't stand out as groundbreaking now, when last night's Mad Men said shit twice, but in 1967, In Cold Blood became the first major release to utter the word bullshit. For the second year in a row, Brooks received Oscar nominations for directing and adapted screenplay and Hall got one for cinematography. Quincy Jones also picked up a nomination for original score, though Jones didn't receive one for his music for In the Heat of the Night. I don't understand how the nimrods at the Academy left it out of the top five for best picture. They nominated two films that deserved to be there: Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate. The film that won, a fine film but certainly expendable: In the Heat of the Night. A perceived prestige project of social significance that's overrated as hell: Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. The fifth nominee that would make no sense in any year: Doctor Dofuckinglittle. Basically, three out of the five films could have been tossed to make room for In Cold Blood. A few other more deserving 1967 titles: Cool Hand Luke, The Dirty Dozen, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, Accident, Wait Until Dark, Point Blank, The Jungle Book. The National Board of Review did honor Brooks' direction. Brooks also received his sixth Directors Guild nomination and his sixth Writers Guild nomination. With the exception of the WGA, Brooks would never be named for any of the top awards again. In Cold Blood marked his best, but from there things went downhill fast.

One of the most difficult films to find (I've never seen it) for that recent a film with a best actress nomination. Brooks wrote his first original screenplay since Deadline-U.S.A. as a vehicle for wife Jean Simmons. From descriptions I've read, Simmons plays Mary Wilson, who was raised on romantic notions of marriage from the movies, finds herself in a funk on her anniversary and flies to the Bahamas on a whim, running into a free spirit (Shirley Jones) while there.

I missed this one as well. From TCM's web site; "In Hamburg, Germany, American Joe Collins (Warren Beatty) is considered by bank manager Kessel (Gert Fröbe) to be the most honest, hard-working bank security expert in the world. Unknown to Kessel, Joe has been devising a plan with his girlfriend, American expatriate prostitute Dawn Divine (Goldie Hawn), to take the contents from bank safe-deposit boxes owned by several criminals and place them into one owned by Dawn. Roger Ebert gave it three stars in his original review.

I wanted to see this one, but just ran out of time. Here's what qualifies as TCM's full synopsis: A former roughrider (Gene Hackman) matches wits with a lovely but shady lady-in-distress (Candice Bergen), as a drifting ex-cowboy (James Coburn) and a young, reckless cowboy (Jan-Michael Vincent) join in on a 700 mile journey. Ebert gave it three and a half stars in his original review.

I've actually seen this one. In fact, as we near the end of Brooks' career, I've watched two of the last three movies. As an unrelated sidenote, this year also marked the end of Brooks' 17-year marriage to Jean Simmons. If by chance you aren't familiar with this movie, think of it as sort of the Shame of the 1970s — and I don't mean the Ingmar Bergman movie. Diane Keaton stars as a teacher of deaf students whose affair with her college professor ends badly. She reacts as anyone would to a breakup — she starts cruising New York bars and picking up strangers for one-night stands while also developing a taste for drugs. The film definitely didn't belong in the genre of liberated women films of the 1970s as Keaton's character will pay. I saw this when I was a young man and I found it distasteful then, though it did have more sensible plotting than last year's Shame. Brooks directed his last performer to an Oscar nomination with Tuesday Weld getting a supporting actress nod. Keaton won the best actress Oscar for 1977 — but for Annie Hall. Brooks adapted a novel by Judith Rossen that was loosely based on a real incident, but most reviews by people who had read the novel seemed to indicate that Brooks changed key elements. Then, that matches the speech Brooks gave the movie's cast and crew on the first day of shooting, according to Douglass K. Daniel's Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks. "I'm sure that all of you have your own ideas about what kind of contributions you can make to this film, what you can do to improve it or make it better. Keep it to yourself. It's my fucking movie and I'm going to make it my way!" Daniel wrote. Goodbar also featured Richard Gere in one of his earliest roles. This clip plays off the tension of whether fun and games are at hands or something more dangerous.

Brooks referred to this film as "the biggest disaster" of his career. Later, he amended it slightly, blaming TV for purposely not coverage the film because the movie criticized "checkbook journalism." Having watched Wrong Is Right for the first time recently, this compels me to ask, "It did?" Sean Connery stars as a globetrotting reporting for what appears to be a CNN-like news station. The opening sequence contains some amusing moments, (including a young Jennifer Jason Leigh, nearly 30 years after her dad Vic Morrow played the worst punk in Brooks; Blackboard Jungle) but what could be cutting-edge satire of a media form just being born transforms into a scattershot satire involving fictional oil-rich African countries, the CIA, a presidential race and arms dealers trading suitcase nukes, Based on a novel, I hope that it had a plot, but Wrong Is Right just ends up being one of those strange satires like The Men Who Stared at Goats where once it ends you still don't know what the hell happened. This clip shows the opening sequence. Nothing after it deserves your attention.

I've got good news and bad news when it comes to Richard Brooks' final film. The good news: it brought him awards consideration again. The bad news: It was at the Razzies where it earned nominations for worst picture, worst director, worst screenplay and worst musical score. I'm not sure whether or not it relieved him that the film lost in all four categories, with Rambo: First Blood Part II taking worst picture, director and screenplay and Rocky IV winning worst score dishonors. I have not seen Fever Pitch which TCM hasn't even given a synopsis, but I know enough to tell you that Ryan O'Neal plays an investigator reporter doing a story on compulsive gambling who discovers he suffers from the problem. The subject of the movie came up on my Facebook page and Richard Brody, critic at The New Yorker, commented, "I saw Fever Pitch when it came out and loved every overheated second. Haven't seen it since then. Seeing The Connection has brought it back: no detached observer but a participant almost instantly in over his head." At the time of its release, it became one of the rare films that Ebert gave zero stars.

Following Fever Pitch, Brooks toyed with the idea of writing a screenplay about the blacklist, basing it around an incident in 1950 when fights broke out at the Directors Guild over the loyalty oath, but he didn't get around to it. The man who could be quite a bully on the set, had quite a bit of bitterness toward the industry by now as he showed in the second half of that 1985 interview.

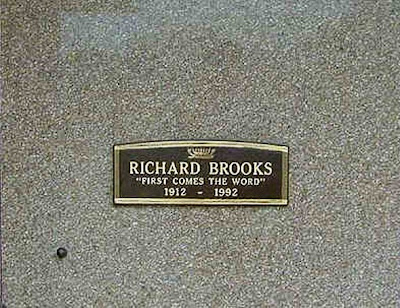

Richard Brooks died of congestive heart failure on March 11, 1992, at 79. He did have close friends, but most of them had died themselves by then. The stepdaughter he basically raised as his own when he married Jean Simmons, Tracy Granger, made certain, his tombstone bore the only appropriate epitaph for the man.

Tweet

Labels: Arthur Miller, blacklist, Books, Capote, Connery, Diane Keaton, Ebert, Hackman, Hitchcock, J.J. Leigh, James Coburn, Jean Simmons, Jewison, Mailer, N. Lear, Neil Simon, P.S. Hoffman, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, January 31, 2012

That's how you fictionalize your life

By Edward Copeland

While watching 50/50, screenwriter Will Reiser's fictionalized account of being diagnosed with a rare form of cancer when he was in his late 20s, I thought of Godard's famous quote about the best way to criticize a movie is to make another movie. Now, I don't think that Reiser and director Jonathan Levine set out to do this, but 50/50 displays an exceptional example of how not to get so locked in by one's life that your movie can't breathe as was the case with Beginners.

Joseph Gordon-Levitt stars as Adam Learner, an NPR employee who has been complaining of back pain for quite some time. When he finally gets it checked out, it turns out to be a malignant tumor on his spine. Doing the modern research technique — Adam turns to the Internet to learn what he can and finds that if the cancer hasn't metastasized, the online information gives the person with his type of cancer a 50 percent chance of surviving. When he shares that information with his best friend and NPR co-worker Kyle (Seth Rogen), Kyle likes the odds, telling Adam they are better than he'd get in a casino.

Adam's overbearing mom Diane (Anjelica Huston, in her best role in a long time) eagerly offers to take over and care for Adam despite the fact that she's already dealing with his father Richard (Serge Houde), who has Alzheimer's disease. However, Adam's live-in girlfriend Rachael (Bryce Dallas Howard) steps up and says she'll stand by Adam through his treatment. Given the turn his young life takes, Learner understandably sinks into depression, prompting his doctor (Andrew Airlie) to refer Adam to a therapist (Anna Kendrick), only she still has her training wheels on, so to speak, as she hasn't completed her doctorate and Adam is only her third patient.

50/50 contains a lot of laughs, but it's more dramatic than I was expecting. In fact, given that Rogen basically plays a fictionalized version of himself (and when isn't Seth Rogen playing a fictionalized version of himself. Keep in mind, I never saw The Green Hornet.), I can't help but wonder if Will Reiser's story inspired Judd Apatow when he came up with Funny People where Rogen becomes best friends with Adam Sandler's comic character with cancer. Of course, 50/50 contains many major differences from Funny People, the most important being that we care what happens to Gordon-Levitt's character while I suffered some disappointment that they didn't kill Sandler off.

Gordon-Levitt continues to have one of the most amazing careers for actors who began plying their craft at an early age, dating back to TV sitcom work on the short-lived The Powers That Be from Norman Lear when he was 11 and a recurring role on Roseanne a year later. At 14 or 15, he gave the best performance in the wretched film The Juror starring Demi Moore, Alec Baldwin and James Gandolfini. Then he more than held his own as part of the comic ensemble of 3rd Rock From the Sun for six seasons.

Since he's grown into adulthood, he's completely missed the curse that often afflicts child actors, giving good to great performances in films such as Mysterious Skin, Brick, The Lookout, (500) Days of Summer, Inception and now 50/50. Reiser's screenplay delicately blends comedy and pathos and Gordon-Levitt has shown that he's adept at both forms with his previous choices, but 50/50 may be his first vehicle that allows him to display his range realistically within the same film.

Rogen, with the exception of the creepy and defiantly unfunny Observe and Report always plays himself more or less. The Rogen you see in Knocked Up simply is an R-rated version of Seth Rogen the talk show guest or Seth Rogen, award show presenter. In most circumstances, an actor like this would drive me up the wall, but I never hold it against Rogen because from the moment I first saw him on the great TV show Freaks and Geeks, he so strongly reminded me of a friend of mine from high school that each time I see him it's like seeing that friend again.

Huston, as you'd expect, turns in a great performance, even if you don't get that much of her. Howard also does the best job I've seen her do, though she never seems to look the same from one film to the next.

The other real bright spot of 50/50 belongs to Kendrick. She was so good (and Oscar-nominated) in Up in the Air. She also popped up in the fun Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World ss Scott's sister and I first noticed her in her film debut, the underrated and underseen musical Camp.

From all the praise that 50/50 received, it didn't turn out to be quite the movie I was expecting. It's good, but not in the ways it had been sold to me.

Tweet

Labels: 10s, A. Huston, Alec Baldwin, Apatow, Demi, Gandolfini, Godard, Gordon-Levitt, N. Lear, Seth Rogen

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, January 14, 2012

“That’s S-A-N…F-O-R-D…period.”

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

In 1968, despite never having watched an episode, television producer Norman Lear purchased the rights to Till Death Us Do Part, a landmark U.K. sitcom that featured an unapologetic bigot as its main character. Lear was convinced that such a show could catch hold on the American side of the pond, and after two pilots were turned down by all three major networks he succeeded with All in the Family, which premiered on CBS in January 1971. The program would come to revolutionize television comedy in the U.S., eventually (after a slow start) leaping to the No. 1 position in the Nielsen ratings.

Lear and his partner Bud Yorkin, who produced All in the Family through their company Tandem Productions, decided to follow up Family’s success by adapting another sitcom that had a British pedigree; Steptoe and Son, a series about a father-and-son team of “rag and bone” (junk) merchants, had been a favorite of U.K. audiences since 1962 and both men were certain that the show could accommodate the viewing habits of U.S. viewers. Yorkin, with the help of veteran TV scribe Aaron Ruben, put together two separate pilots in mid-1971; one that starred Lee Tracy and Aldo Ray as the American versions of the Steptoes, the other with Barnard Hughes and Paul Sorvino as père et fils. It was only after seeing stand-up comedian Redd Foxx in his scene-stealing role as a junk dealer in Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970) that Yorkin and Ruben realized changing the ethnicity of the main characters to African-American was the way to go with their adaptation…and with that, the stage was set for the premiere of Sanford and Son 40 years ago on this date.

Redd Foxx’s birth name was John Elroy Sanford — and that surname was soon adopted as the same handle of the television character that would make the actor-comedian famous (the “Fred” was a tribute to Foxx’s older brother). Not that Redd Foxx was an unknown in show business; it’s just that he was more popular among black audiences as a familiar fixture in the 1940s and 1950s on the “Chitlin’

Circuit” (a nickname given to some famed black nightclubs of that era) in addition to recording a series of ribald (rated XXX for the times) “party” albums in the 1960s. At age 48, Foxx would be playing a 65-year-old widowed junk dealer but could no doubt be convincing due to his years of hard living (booze, cigarettes and drugs). Yorkin observed of the Man Who Would Be Sanford: “He was gray, and the way he walked on the show was pretty much the way he walked in real life. He had beaten himself up too much.” The role of Redd’s 30-year-old television son — to be dubbed Lamont Sanford — went to 24-year-old Demond Wilson, a young actor whose résumé included both Broadway and off-Broadway productions and who had made a favorable impression on Lear when Wilson guest-starred on an episode of All in the Family as one of two burglars (the other played by Cleavon Little, who had been approached originally by Yorkin to appear on the series but wound up recommending Foxx instead) ransacking the Bunker house. With the cast in place, Yorkin worked on a third pilot with Foxx and Wilson and after CBS President Fred Silverman passed on the show (a situation he once said was “one of the stupidest things I did at CBS”), it was snapped up by NBC executives Herb Schlosser and Mort Werner, who scheduled Sanford and Son as a mid-season replacement for The D.A. in January 1972.

Circuit” (a nickname given to some famed black nightclubs of that era) in addition to recording a series of ribald (rated XXX for the times) “party” albums in the 1960s. At age 48, Foxx would be playing a 65-year-old widowed junk dealer but could no doubt be convincing due to his years of hard living (booze, cigarettes and drugs). Yorkin observed of the Man Who Would Be Sanford: “He was gray, and the way he walked on the show was pretty much the way he walked in real life. He had beaten himself up too much.” The role of Redd’s 30-year-old television son — to be dubbed Lamont Sanford — went to 24-year-old Demond Wilson, a young actor whose résumé included both Broadway and off-Broadway productions and who had made a favorable impression on Lear when Wilson guest-starred on an episode of All in the Family as one of two burglars (the other played by Cleavon Little, who had been approached originally by Yorkin to appear on the series but wound up recommending Foxx instead) ransacking the Bunker house. With the cast in place, Yorkin worked on a third pilot with Foxx and Wilson and after CBS President Fred Silverman passed on the show (a situation he once said was “one of the stupidest things I did at CBS”), it was snapped up by NBC executives Herb Schlosser and Mort Werner, who scheduled Sanford and Son as a mid-season replacement for The D.A. in January 1972.

At 9114 S. Central Ave., in the Watts section of Los Angeles, Fred G. Sanford and his son Lamont operate a combination junk/salvage/second-hand antiques store, and often struggle to make ends meet. Though both men ostensibly are partners in the business, Lamont did most of the work — driving the company’s pickup and doing the heavy lifting while father Fred functions as the “coordinator” of their inventory. Fred is, in many ways, the more childlike of the duo, often shirking his duties (like many adolescents) in favor of watching TV (his preferences lean to soap operas, game shows and Godzilla movies), playing cards and/or checkers and just generally goofing off. When called on his goldbricking by Lamont, Fred would complain about his “arthur-itis” (holding one hand up in a claw-like motion) and when that failed, would fake a heart attack at the drop of a hat, clutching his chest and hollering out “You hear that, Elizabeth? I’m comin’ to join you, honey!” (Elizabeth was Fred’s late wife.) Fred also possessed an irascible nature that often threatened to cleave the strong family ties between he and his son. He refers to Lamont as “you big dummy” and would raise his fist frequently to ask threateningly: “How would you like one ‘cross your lips?”

The stormy relationship between Fred and Lamont in the early years of Sanford and Son parallels that of its British counterpart (not surprisingly, since many of its scripts were retooled versions of the U.K. originals). Despite their incessant bickering, both father and son demonstrate real affection for one another and both could be out-and-out schemers when it came to the junk business. This gradually was phased out in later seasons, as Fred became more of a Ralph Kramden-like plotter determined to find ways to make a quick and easy buck, and Lamont morphed into a more level-headed individual patiently trying to get his dad to be more open-minded and accepting of people’s cultural differences. For Fred Sanford also was, in the tradition of his white All in the Family counterpart Archie Bunker, an unrepentant bigot, whose contempt for other races, sexes and creeds — whites, Latinos, Asians, women and even gays — knew no bounds and, as such, his prejudicial views frequently caused son Lamont endless headaches.

However, there was a subtly subversive characteristic in Fred Sanford’s detrimental make-up: Sanford and Son, like All in the Family, may have satirized prejudice by lampooning its bigoted main character and emphasized its absurdity by making certain those individuals suffered the consequences of their backward thinking, but it often seemed as if Fred got off a little easier than Archie. Bunker would be challenged by other characters on his offensive remarks but with Sanford, not so much. The “lessons” that Family placed special emphasis on weekly weren’t always in full force on Sanford. It seemed to eschew topicality in favor of what author Paul Mavis calls “guilt-free racial humor.” Re-visiting episodes of Sanford and Son reveals that much of the show’s insult-based comedy is most assuredly un-P.C., and if anyone attempted to offer up a series cultivating such a freedom of expression to a network today, they would most definitely be on the receiving end of a media backlash, despite the groundbreaking nature of the show’s portrayal of an integrated neighborhood in the 1970s. Fred and Lamont may have resided in lower-income environs but they shared the same square-foot yardage with Jews, Latinos (Gregory Sierra’s Julio Fuentes) and Asians (Pat Morita’s Ah Chew).

To emphasize how pioneering Sanford and Son was in its five years on the air, film critic Gene Siskel once wrote, “What All in the Family did for the Caucasian race in our nation with television, Sanford and Son did for African Americans. It is one of the two most noted and significant African-American sitcoms since the invention of television.” I don’t know which other sitcom Siskel references, but even though Sanford was awarded recognition by many scholars for its innovations, a second look at the series reveals that it was in many

ways an updated Amos ‘n’ Andy for the 1970s. The lead character of Fred Sanford, with his endless conniving and scheming, wasn’t too far removed from George “Kingfish” Stevens, and Fred’s nemesis on the show, sister-in-law “Aunt Esther” Anderson (LaWanda Page), was a direct descendant of Kingfish’s shrewish spouse Sapphire. Many of Fred’s pals on the show — Melvin (Slappy White), Bubba (Don Bexley), Leroy (Leroy Daniels), “Skillet” (Ernest Mayhand), etc. — could all be members-in-good-standing “of that great fraternity, the Mystic Knights of the Sea.” Fred’s best buddy, the eternally befuddled Grady Wilson (Whitman Mayo), was interchangeable as both the show’s resident Andrew H. Brown and the Mystic Knights’ slow-witted janitor, Lightnin’. The minstrelsy of Sanford could be attributed to the fact that the series, like the earlier A&A, was written mostly by white comedy scribes, including a young Garry Shandling before he turned to standup comedy, (a sore point with star Redd Foxx, who fiercely lobbied for more black writers and directors on the show) but when you also take into consideration that Foxx was an Amos ‘n’ Andy fan (he often waved away that series’ controversial nature by simply arguing that “funny is funny”) the comparison isn’t perhaps all that coincidental.

ways an updated Amos ‘n’ Andy for the 1970s. The lead character of Fred Sanford, with his endless conniving and scheming, wasn’t too far removed from George “Kingfish” Stevens, and Fred’s nemesis on the show, sister-in-law “Aunt Esther” Anderson (LaWanda Page), was a direct descendant of Kingfish’s shrewish spouse Sapphire. Many of Fred’s pals on the show — Melvin (Slappy White), Bubba (Don Bexley), Leroy (Leroy Daniels), “Skillet” (Ernest Mayhand), etc. — could all be members-in-good-standing “of that great fraternity, the Mystic Knights of the Sea.” Fred’s best buddy, the eternally befuddled Grady Wilson (Whitman Mayo), was interchangeable as both the show’s resident Andrew H. Brown and the Mystic Knights’ slow-witted janitor, Lightnin’. The minstrelsy of Sanford could be attributed to the fact that the series, like the earlier A&A, was written mostly by white comedy scribes, including a young Garry Shandling before he turned to standup comedy, (a sore point with star Redd Foxx, who fiercely lobbied for more black writers and directors on the show) but when you also take into consideration that Foxx was an Amos ‘n’ Andy fan (he often waved away that series’ controversial nature by simply arguing that “funny is funny”) the comparison isn’t perhaps all that coincidental.

Sanford and Son’s premiere in 1972 gave NBC a solid hit on its Friday night schedule (long considered by industry wags to be a “death sentence”); it finished as the sixth-rated TV series in the Nielsen ratings in its first short season and for three seasons after that, was second only to All in the Family in viewership. Foxx’s instant celebrity from the sitcom eventually led to his dissatisfaction with what he was being paid for his role (he started out at $7,500 an episode, the same salary that Carroll O’Connor started out with on Family) and midway during the 1973-74 season, he walked off the show in protest. To explain Foxx's departure, the show introduced a storyline where Fred was away in his native St. Louis attending a cousin’s funeral and Grady had been put in charge of the business (and Lamont) in his absence. When Sanford’s ratings remained consistent despite its missing star, however, Foxx returned to the fold. While the show continued its ratings dominance for a time afterward, the seams already were starting to show; the plots got a bit sillier (Sanford fell back on the same gambit that was prevalent on The Lucy Show, making each outing a “guest star of the week”) and more outlandish. Foxx’s longtime cocaine addiction didn’t do him any favors, and co-star Wilson also developed a substance abuse problem (as well as numerous disagreements with the show’s production staff). Occasionally, the sitcom indulged in a bit of self-reflexive almost meta-humor as in an episode when Fred enters a Redd

Foxx look-a-like contest and plays both parts. The best example was the fifth season episode "Steinberg and Son" when Fred and Lamont discover a new TV sitcom appears to be based on their life, except all the characters are Jewish. They file suit, but then Fred sees it as his chance for stardom and gives tips to the actor play the Jewish Fred Sanford (Lou Jacobi) on how to react to the Aunt Esther equivalent. John Larroquette plays the Jewish Lamont. Robert Guillaume appears as Fred and Lamont's lawyer. The final inside joke comes when it turns out the show was written by a cousin of Rollo's and they asks the young African-American man why he didn't make the characters black, but he says no one would buy that. It's one of the more clever later episodes. In its final season, Sanford and Son was ranked No. 27 in the ratings, still respectable for a renewal, but by that time Foxx had been lured away to ABC for more money and a comedy-variety hour bearing his name. Demond Wilson couldn’t come to terms with Sanford’s producers so he called it quits as well. The result was a spin-off series (the show’s second; its first was a program starring the Whitman Mayo character, Grady, in 1975-76) entitled The Sanford Arms that starred Teddy Wilson as Phil Wheeler, who buys the rooming house next door that Fred and Lamont rented out to boarders for supplemental income. Sanford returnees who made appearances included Mayo, and Bexley. (Eight episodes were filmed, but the series was canceled after four.)

Foxx look-a-like contest and plays both parts. The best example was the fifth season episode "Steinberg and Son" when Fred and Lamont discover a new TV sitcom appears to be based on their life, except all the characters are Jewish. They file suit, but then Fred sees it as his chance for stardom and gives tips to the actor play the Jewish Fred Sanford (Lou Jacobi) on how to react to the Aunt Esther equivalent. John Larroquette plays the Jewish Lamont. Robert Guillaume appears as Fred and Lamont's lawyer. The final inside joke comes when it turns out the show was written by a cousin of Rollo's and they asks the young African-American man why he didn't make the characters black, but he says no one would buy that. It's one of the more clever later episodes. In its final season, Sanford and Son was ranked No. 27 in the ratings, still respectable for a renewal, but by that time Foxx had been lured away to ABC for more money and a comedy-variety hour bearing his name. Demond Wilson couldn’t come to terms with Sanford’s producers so he called it quits as well. The result was a spin-off series (the show’s second; its first was a program starring the Whitman Mayo character, Grady, in 1975-76) entitled The Sanford Arms that starred Teddy Wilson as Phil Wheeler, who buys the rooming house next door that Fred and Lamont rented out to boarders for supplemental income. Sanford returnees who made appearances included Mayo, and Bexley. (Eight episodes were filmed, but the series was canceled after four.)Foxx’s ABC effort may have lasted longer (four months) than Sanford Arms but since the comedian remained out of work, he returned to NBC in March 1980 to try and halt the network’s slide into third place with a revival of his hit '70s series re-titled Sanford (no “and Son” because Demond Wilson wasn’t interested; the Lamont character was sent up north to work on the Alaskan Pipeline). Fred Sanford was just as cranky as ever but he had a new partner in the junk business (the go-to thespian for rednecks, Dennis Burkley) and a new girlfriend (Marguerite Ray) whose wealthy family detested him. (The whereabouts of Fred’s old girlfriend on Son, Donna “The Barracuda” Harris — played by actress Lynn Hamilton — went unexplained.) Lamont’s best friend from the previous series, Rollo Larson (Nathaniel Taylor), was now a regular on the show and the characters of Aunt Esther, Grady and Officers “Smitty” (Hal Williams) & “Hoppy” (Howard Platt) turned up from time to time as well but without Demond Wilson’s participation, the series fizzled after two attempts (both of its seasons were as mid-season replacements). Foxx would go on to two other attempts to re-create the sitcom magic of Sanford and Son, notably with The Royal Family in 1991. Midway through this Eddie Murphy-produced sitcom (which paired Foxx with co-star Della Reese), Redd suffered a heart attack while filming an episode. Sadly, the cast and crew mistakenly thought he was gagging it up with his old Sanford “Comin’-to-join-ya-Elizabeth” routine. (When they figured out it was no joke, it came too late to save the comedian’s life.)

One of the longest-lasting legacies of Sanford and Son takes less than a minute. Composed by Quincy Jones, the series' theme (its official title is "The Streetbeater") has such an infectious beat that even people who have never seen an episode of the sitcom can likely make a good attempt at humming it. In fact, on Scrubs, J.D. did exactly that once to try to get Turk into a good mood. Thanks to YouTube, here is the series' opening with Jones' track.

The stars of Steptoe and Son, Wilfrid Brambell and Harry H. Corbett, might have made small screen magic during their long TV partnership but according to several sources, their relationship off-screen was quite acrimonious. The same charge has been leveled at Sanford and Son’s Redd Foxx and Demond Wilson — but in re-visiting the series, one can’t help but marvel at the chemistry between the two actors in their roles. Lamont, despite suffering from the indignities and difficulties generated by his cantankerous father, really does love and respect Fred and you can see it in how actor Wilson will sometimes grin at Foxx when Redd does a bit of business that tickles him. A character like Fred G. Sanford probably would be intolerable in real life, but Foxx exhibits a pixie-ish temperament (his apologetic wave at a person he’s gone too far insulting or his petulant pout at being scolded like a mischievous kid) that makes him endearing despite his shortcomings. A genuine artifact of the 1970s; Sanford and Son’s uncompromising humor still resonates with audiences today both on DVD and in endless reruns; furthermore, it laid the groundwork for future hits from the Norman Lear stable, including Good Times and The Jeffersons. And in the words of the immortal Redd Foxx: funny is funny. That’s all you need to know, you big dummy.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Eddie Murphy, N. Lear, Shandling, Theater, TV Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, November 01, 2011

Short walks on different piers

Throughout the years when I truly harbored an Oscar obsession, I seldom had an opportunity to see any of the nominees for best live action short or even the winner. Recently, I happened to have been contacted by representatives of three short films that have all qualified to be a potential nominee for the 2011 award, though we have no idea if any or all of the shorts will even make the preliminary cut let alone the final list at this point. Rather by coincidence or something in the air, the three films share some common traits: each features an Oscar-nominated performer (in one case, a winner), each deals, to some extent, with ways people escape and all three feature piers and bodies of water, even if only in passing. What fascinated me the most was the huge differences in running times. To qualify in the category, you have to be less than 40 minutes long. These films clock times that run about a half-hour, 18 minutes and six minutes in length. I'm reviewing them alphabetically, which happens to coincide from shortest to longest.

Six minutes wouldn't seem like much time to tell a story or create a character, but writer-director Brent Roske more or less accomplishes this through the use of the third skill he employs on his short African Chelsea: editing. (He filmed it as well.) In that brief amount of time, Roske manages to tell his complete story through the judicious cutting of quick shots whose juxtaposition and order let us know what we need to about the character of Chelsea (Corinne Becker), a young woman who fled her dysfunctional homelife to live alone and work as an exotic dancer.

The home she ran away from is headed by her overbearing mother Anna (Sally Kirkland, 1987 best actress nominee for a completely unrelated Anna). Playing the third character who carries any significance is Tosa Oghbagado as Tosa, the bodyguard for the dancers at the club in which Chelsea works. Kirkland also wrote and sings the short's recurring song "Indian Man."

While you might expect the editing to be frenetic from beginning to end, African Chelsea contains frequent slow, sometimes moving passages. The short played at Cannes and has earned praise from a wide-range of sources, including none other television pioneer Norman Lear (All in the Family), who hailed it as a "wonderful film" and called Baker "a lovely actress."

Roske received a Daytime Emmy nomination in 2006 with director Chuck Bowman in the category of outstanding achievement in video content for nontraditional delivery platforms for Sophie Chase. Anyone who would like to watch African Chelsea can see it for free at IMDb here.

While writer-director Elfar Adalsteins' Sailcloth might be nearly three times as long as African Chelsea, the six-minute short could contain about 300 times as much dialogue. Actually, I'm not being mathematically truthful with that statement for there isn't any dialogue in Sailcloth. Then again, when your film focuses on the wonderfully expressive face of the actor John Hurt, who needs words anyway?

The 71-year-old two-time Oscar nominee (for best supporting actor in Alan Parker's 1978 film Midnight Express and for best actor in David Lynch's 1980 take on The Elephant Man) plays an unnamed resident of a nursing home in Sailcloth. Our first glimpse of him pans on his aged hand as a nurse checks his pulse while he lies in bed. Her simple action awakens the man to a fully vibrant state and soon he's out of bed, shaving, dressing and doing some other things I best not share because part of the short's joy comes from deciphering the man's motives and the movie's direction.

Granted, eventually what the man has in mind becomes clear, but until we get there, Adalsteins steers us between moments of humor as well as poignancy, all played pitch perfectly through Hurt's masterful facial expressions. He never utters a word, though he does let out a laugh at one point. Adalsteins' writing and direction couldn't be better served than they are by Hurt. The filmmaker also gets help from Karl Oskarsson's cinematography.

If Sailcloth contains any element that works against it, that would be the original score by Richard Cottle, which has a tendency to underline the mood of every moment in which its music plays. Sailcloth would work just as well — if not better — if its score were less obvious or not noticeable at all. In one of the film's best sequences involving Hurt, a bathroom, a cigar and an umbrella, the score isn't used at all and by using solely the natural sounds of the environs, the sequence delights even further.

Sailcloth received the Grand Jury Prize as best short film at the Rhode Island Film Festival and was an official selection at the Raindance Film Festival in London. It has been named an official selection for the Brest European Short Film Festival to be held Nov. 8-13 in France. The short, which was filmed in the coastal village of St Mawes in Cornwall will return to the region for the Cornwall Film Festival this Friday-Sunday for a screening and Q&A. It also has been named an official selection of the St. Louis International Film Festival to be held Nov. 13-23.

The longest of the three shorts stars Melissa Leo, last year's Oscar winner for best supporting actress for The Fighter and an Emmy nominee this year for her work in the HBO miniseries adaptation of Mildred Pierce. (Of course, Leo was snubbed by the Emmys for the second year in a row for her best work — as Toni Bernette on the criminally neglected HBO drama Treme.)

Leo plays Sara, the primary caregiver for her daughter Angelina (Kelly Hutchinson), who is dying of an unspecified disease. Sara gets an unwelcome visit from her estranged fisherman husband Sonny (Peter Gerety). The Sea Is All I Know marks a reunion of sorts for Gerety and Leo as both were regulars on the NBC series Homicide: Life on the Street, though not at the same time. However, the story that introduced Gerety's Stu Gharty character did have Gerety as a guest interact with Leo's memorable Detective Kay Howard.

As if Sara and Sonny's relationship weren't already fraught with tension, a new debate and crisis arises as Angelina begs her parents to help her end her life. It not only sparks a new argument between the two over the issue of dying with dignity but ignites questions of faith and spirituality within each of them as well. Leo, as you would expect, turns in a solid performance, but for me Gerety ends up as the standout here. It especially comes out when he's discussing his problems with fellow fishermen Ghent (Michael Graves). Sonny says that it just isn't right for a child to die before the parent and Ghent comments, "Who are we to understand the reason for our suffering? Jesus suffered." This sets Sonny off and Gerety performs the speech masterfully. “Fuck that! Fuck that! I don’t want to hear about Jesus suffering. For how long? A couple of hours? Just for a few hours? You know what I think? Jesus suffered because his friends abandoned him. Jesus suffered because God abandoned him for a few hours. You look at my baby up there — suffering in that house for months. You look over, you see people eatin’ shit all their lives — that’s suffering. Jesus suffered — it ain’t natural to send your own son to the gallows.” Gerety’s speech, for me anyway, ends up being the film’s best moment.

The Sea Is All I Know was written, directed, co-produced and even partly scored by Jordan Bayne who, prior to turning to filmmaking, worked as an actress since the 1990s. Anyone who has read me on a regular basis knows how important a topic Death With Dignity is to me, being bedridden myself. While the short certainly has strong performances, I believe it has the misfortune of coming on the heels of two superior works that looked at the subject: You Don't Know Jack, the HBO biographical film about Jack Kevorkian starring Al Pacino and the superb HBO documentary How to Die in Oregon.

What separates the long-form biographical feature and the documentary and make them superior to The Sea Is All I Know while covering similar subject matter is that the other two films tackle the issue without getting bogged down in melodramatic flourishes. The short film does it to such an extent that the issue becomes a sidenote. Sara mentions Angelina's desire to Sonny once and he objects. The two then have separate theological moments, a confrontation about their own relationship, end up in bed together and then seem to be feeding her a fatal elixir. If there were a ccnversation between them settling the matter or even something that said explicitly what state they lived in or how they would obtain the lethal dose, the short omits that scene. There is no volunteer from any agency assisting them with their daughter's final exit as there would be in most states that have had the foresight to legalize Death With Dignity.

Perhaps The Sea Is All I Know plays differently to people who aren't as familiar with the issue as I am, but the distractions and discrepancies took me out of the short with the exception of that one great Gerety speech. When it premiered at the Palm Springs International ShortFest, it was awarded Best of Fest by the audience and Melissa Leo won the Grand Jury Prize for best actress at the Rhode Island Film Festival, the festival where Sailcloth won the Grand Jury Prize for best short. I believe those Rhode Island voters recognized the same things I did since of the two shorts (though I assume others I haven't seen also competed), the better short won.

Tweet

Labels: 10s, A. Parker, Awards, Documentary, HBO, Homicide, John Hurt, Lynch, Melissa Leo, N. Lear, Oscars, Pacino, Shorts, Treme

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

Those were the days

By Edward Copeland

Forty years ago tonight, CBS put extra operators in place at switchboards across the United States, anticipating the commotion that would rock the world when a new situation comedy called All in the Family made its debut. With its lead character, a loudmouth, blue-collar bigot in constant conflict with his liberal son-in-law, and broaching prejudice and other touchy topics, the network feared that they wouldn't hear the end of it. Surprisingly, most of the calls they received were favorable, Archie Bunker became a household name and new ground was broken on what could be discussed on a network television series. Unfortunately, when you scan across the dial today, I fear that much of that ground has been lost and a series such as Norman Lear's American take on the British comedy Till Death Do Us Part would never make the network air today.

When All in the Family debuted, its immediate lead-in, unbelievably, was the country music variety series Hee-Haw. Before we "Meet the Bunkers" (the title of the first episode), CBS placed a note on the screen that read as follows:

"The program you are about to see is All in the Family. It attempts to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show — in a mature fashion — just how absurd they are."

Then viewers were treated to that familiar opening number, re-shot several times over the years as the characters and actors aged, of Carroll O'Connor and Jean Stapleton as Archie and Edith Bunker sitting at the piano and warbling the words to "Those Were the Days."

songs that made the hit parade,

guys like us we had it made,

those were the days.

And you knew where you were then,

girls were girls and men were men,

mister we could use a man like Herbert Hoover again.

Didn't need no welfare state,

everybody pulled his weight,

gee our old Lasalle ran great,

those were the days!"

There were other verses, but those were the ones audiences would come to know. Something I'd long forgotten until I started re-watching episodes for this piece is that this song was written by composer Charles Strouse and lyricist Lee Adams, the team best known for the Broadway musicals Bye Bye Birdie and Annie, among many others. Strouse even composed some film scores solo including Bonnie and Clyde and Ishtar. Strouse also scored the movie The Night They Raided Minsky's, which was co-written and produced by Norman Lear, the mastermind who brought All in the Family to the small screen.

For such nervous executives, All in the Family had an extraordinarily long and fruitful run of nine seasons and 201 episodes and that doesn't count its mutation into the four-season, 97 episode run of Archie Bunker's Place. It, alongside other 1970s hits Happy Days and The Mary Tyler Moore Show, proved extraordinarily successful when it came to spinning off characters into their own series. All in the Family begat Maude (which itself begat Good Times), The Jeffersons (which begat the short-lived Florence spinoff Checking In) and, even though they were less successful or downright flops, a much later series called Gloria and a brief one called 704 Hauser Street, which only took place in the same house in which the Bunkers had lived but was now occupied by an African-American family with a old-style liberal father (John Amos) clashing with his conservative college-age son.

Since it began midseason, that first season had a mere 13 episodes and, as still is the case with most shows today, it usually takes a few episodes for a new series to find its sea legs. Various reference sources will give you different titles for some of the episodes. The episode titles on the DVD won't necessarily match those in the book Archie & Edith, Mike & Gloria by Donna McCrohan or the IMDb or episode guides Web site. Regardless of its title, having re-watched the entire first season (time constraints prevented me from re-visiting all the episodes (at least that's my excuse for avoiding the Danielle Brisebois season), the fourth episode, which I'll call "Judging Books By Covers," is the episode when they really had all the cylinders humming. Archie finds himself annoyed when Mike's flamboyant friend Roger (Anthony Geary in his pre-General Hospital days) visits and Archie assumes by his dress and the way he carries himself that Roger

must be gay, despite Mike and Gloria's insistence that he's straight. Archie finally seeks refuge at his favorite place of refuge, Kelsey's Bar, where he gets to hang with his old friend and former football star Steve (the late Phil Carey, in his pre-One Life to Live days) who now runs a photography store and knows Roger through it. When Mike and Roger drop by, Kelsey (Don Hastings) pulls Mike aside just to be reassured that Roger isn't gay, because he doesn't want Kelsey's to become known as one of those bars because Steve is gay, even though Archie is utterly clueless about it. Eventually, Mike and Archie argue and Mike blurts out the truth and Archie sees Steve again and is laughing, saying that Steve will want to sock Mike for what he said about him. Then Steve tells Archie that it's true and turns Archie's world asunder. It's a landmark episode. Compare it to the very funny first season Cheers episode "The Boys in the Bar," where rumors of gay men frequenting the bar prompt fears that the whole bar could go gay. It's a very good episode and while there is an element of homophobia addressed, less than 11 years after "Judging Books By Covers," it's a sort of defanged homophobia, afraid to push the boundaries of hate and ignorance that dwells beneath.

must be gay, despite Mike and Gloria's insistence that he's straight. Archie finally seeks refuge at his favorite place of refuge, Kelsey's Bar, where he gets to hang with his old friend and former football star Steve (the late Phil Carey, in his pre-One Life to Live days) who now runs a photography store and knows Roger through it. When Mike and Roger drop by, Kelsey (Don Hastings) pulls Mike aside just to be reassured that Roger isn't gay, because he doesn't want Kelsey's to become known as one of those bars because Steve is gay, even though Archie is utterly clueless about it. Eventually, Mike and Archie argue and Mike blurts out the truth and Archie sees Steve again and is laughing, saying that Steve will want to sock Mike for what he said about him. Then Steve tells Archie that it's true and turns Archie's world asunder. It's a landmark episode. Compare it to the very funny first season Cheers episode "The Boys in the Bar," where rumors of gay men frequenting the bar prompt fears that the whole bar could go gay. It's a very good episode and while there is an element of homophobia addressed, less than 11 years after "Judging Books By Covers," it's a sort of defanged homophobia, afraid to push the boundaries of hate and ignorance that dwells beneath.Despite the expected controversy, All in the Family did not become a ratings juggernaut during its initial run and it wasn't even certain that a renewal was in the offing. Critical reaction was mixed. Some thought it was endorsing Archie's prejudice, while others felt it was soft-pedaling it by having him use "softer" epithets for various groups instead of harsher terms. Still, as the series stayed on, its numbers grew and at the Emmys

(which actually were held in May back then), it picked up outstanding comedy series and outstanding actress in a comedy series for Jean Stapleton as well as the defunct Emmy category of outstanding new series. When the 13 episodes were rerun during the summer, its numbers skyrocketed and by the time of its second season premiere in September, it was the No. 1 rated series on television. It stayed at the top or near the top for most of the rest of its run and retained much Emmy love. The following year, it practically swept the Emmys, winning series, actor (O'Connor), actress (Stapleton), supporting actress (Sally Struthers in a tie with Valerie Harper for The Mary Tyler Moore Show), writing (for "Edith's Problem") and directing for the classic "Sammy's Visit" when none other than Sammy Davis Jr. winds up in Archie Bunker's living room. Over the course of its nine seasons, it won four Emmys for comedy series, O'Connor won four times, Stapleton won three times, Rob Reiner and Struthers each won twice, it won three times for writing and twice for direction.

(which actually were held in May back then), it picked up outstanding comedy series and outstanding actress in a comedy series for Jean Stapleton as well as the defunct Emmy category of outstanding new series. When the 13 episodes were rerun during the summer, its numbers skyrocketed and by the time of its second season premiere in September, it was the No. 1 rated series on television. It stayed at the top or near the top for most of the rest of its run and retained much Emmy love. The following year, it practically swept the Emmys, winning series, actor (O'Connor), actress (Stapleton), supporting actress (Sally Struthers in a tie with Valerie Harper for The Mary Tyler Moore Show), writing (for "Edith's Problem") and directing for the classic "Sammy's Visit" when none other than Sammy Davis Jr. winds up in Archie Bunker's living room. Over the course of its nine seasons, it won four Emmys for comedy series, O'Connor won four times, Stapleton won three times, Rob Reiner and Struthers each won twice, it won three times for writing and twice for direction.What remains astounding though are the topics that it worked so openly into conversation as part of an overriding story. Sex probably is the only topic the networks still feel safe in touching in the same way.

Are there any other open atheists on network television now other than Dr. Gregory House since Dr. Perry Cox and Scrubs left the air? When there was a report that The Simpsons discussed religion more than any other series, there was more truth in that than you know. Certainly, no series would attempt an episode such as All in the Family did when Archie, concerned that his new grandson's soul was doomed because of nonbelieving father Mike, sneaked the infant to a church to perform his own baptism. Nor would they tackle the loss of faith the truly religious Edith faced when their friend, the cross-dressing Beverly LaSalle, was murdered. (Archie, for all his bluster about about the Bible and his misquoting of it, seldom actually attended a service.) Vietnam came up in the Bunker household far more often and earlier than it got any serious treatment in films. Once again, Scrubs was one of the few recent series to touch on that sort of subject when it had an episode where the staff took sides on the Iraq war.

Are there any other open atheists on network television now other than Dr. Gregory House since Dr. Perry Cox and Scrubs left the air? When there was a report that The Simpsons discussed religion more than any other series, there was more truth in that than you know. Certainly, no series would attempt an episode such as All in the Family did when Archie, concerned that his new grandson's soul was doomed because of nonbelieving father Mike, sneaked the infant to a church to perform his own baptism. Nor would they tackle the loss of faith the truly religious Edith faced when their friend, the cross-dressing Beverly LaSalle, was murdered. (Archie, for all his bluster about about the Bible and his misquoting of it, seldom actually attended a service.) Vietnam came up in the Bunker household far more often and earlier than it got any serious treatment in films. Once again, Scrubs was one of the few recent series to touch on that sort of subject when it had an episode where the staff took sides on the Iraq war. Of course, the topic that came up the most frequently was Archie's bigotry, but the secret is that Archie doesn't know that he's a bigot. When he and Edith sing "Those Were the Days," they are referring to the Great

Depression and World War II, back when Bunker thought the future would be great and before he realized that his blue-collar life would be a struggle. He would never be the type to burn a cross, though he'd sign petitions to try to keep blacks and Jews out of his neighborhood. In fact, when a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan comes to Queens and sees Archie as a potential recruit, they want him to pressure Mike by burning a cross on Stivic's lawn because Mike wrote a letter to a newspaper that the racists didn't agree with. Archie, in one of those rare moments of being on the right (as in correct) side of things, stands up for Mike, refusing to aid them or join them, telling them he's part black because he once received a blood transfusion from a black person, meaning he wasn't "pure white." In the episode that more or less served as a pseudo-pilot for The Jeffersons, The Bunkers and the Stivics attend an engagement party for Lionel (Mike Evans) and Jennie (though Jennie and her parents are all played by different actors than the ones who would play them in The Jeffersons) where George (Sherman Hemsley) learns for the first time that Jennie is the product of a mixed marriage. Being as prejudiced against whites as Archie is against blacks, George stirs up a hornet's nest to the point that Tom and Helen Willis start arguing. George is the first person in the series to use the 'N' word when he suggests that Tom will call Helen that at any moment as Archie proudly makes an aside to Edith that he hasn't used that word in years.