Friday, May 18, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part I

By Edward Copeland

"First comes the word, then comes the rest" might be the most famous quote attributed to Richard Brooks, who began his life 100 years ago today in Philadelphia as Ruben Sax, son of Jewish immigrants Hyman and Esther Sax. He wrote a lot of words too — sometimes using only images. In fact, too many to tell the story in a single post. so it will be three. His parents came from Crimea in 1908 when it belonged to the Russian Empire. Like the parents of a great director of a much later generation and an Italian Catholic heritage, Hyman and Esther Sax also worked in the textile and clothing industry. Sax's entire adult working life revolved around the written word — even while he busied himself with other tasks. “I write in toilets, on planes, when I’m

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

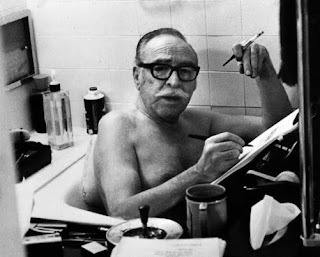

Though Brooks' legend derives predominantly from his film legacy, he experienced his first rush of acclaim with the publication of his debut novel, written while stationed at Quantico at night in the bathroom, according to the account in Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks by Douglass K. Daniel. Several publishers rejected it until Edward Aswell at Harper & Brothers, who also edited Thomas Wolfe, agreed to take it — and he shocked Brooks further by telling him (after a few suggestions) they planned to publish in May 1945. This news flabbergasted Brooks who obtained a weekend pass to go to New York because Aswell insisted on informing him in person. Now Brooks had to return to Quantico where the top officers of the Corps about shit bricks when The New York Times published a big review of The Brick Foxhole soon after it hit shelves. (Orville Prescott's take was mixed, assessing it as compulsively readable but weak on characterization.) Its story of hate and intolerance within the Marines brought threats of court-martialing Brooks, since he'd ignored procedure and never submitted the novel to Marine officials for approval ahead of time. They wanted to avoid bad publicity, especially with all the good feelings as the war wound down. "There was nothing in that book that violated security, but their rules and regulations were not for that purpose alone," Brooks told Daniel. Aswell prepared to launch a P.R. counteroffensive with literary giants such as Sinclair Lewis and Richard Wright ready to stand by Brooks. In case you don't know the story of the novel, it concerns a Marine unit in its barracks and on leave in Washington. Through their wartime experiences, some of the men truly turned ugly, suspecting cheating wives and tossing hate against any non-white Christian. It turns out, though the real Marines let the matter drop, what bothered them

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

While he didn't want to make a movie of The Brick Foxhole himself, another former newspaperman turned socially conscious film artist met with Brooks about working with his independent production company. At first, Mark Hellinger tried to lure Brooks away from Universal with the promise of doubling his salary if he'd adapt a play he liked into a movie, but before Brooks could consider that offer, Hellinger called with a more pressing matter. He was producing an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's famous short story The Killers. The problem: someone had to dream up what happened after the brief tale ends because it certainly wouldn't last 90 minutes otherwise. Hellinger flew Brooks out to meet Papa himself, but he didn't get much out of him but he did come up with an idea for what would happen after the story ends. Hellinger liked it and sent it to John Huston, who wrote the screenplay as a favor. Since both Brooks and Huston had contracts at other studios, neither got screen credits, so Ernest Hemingway's The Killers' official screenplay credit goes to Anthony Veiller, who received an Oscar nomination for best screenplay. He'd previously shared a nomination in the same category for Stage Door. The film also made a star out of Burt Lancaster, who would work with Brooks several times and be his lifelong friend. In fact, Lancaster would star in the next screenplay that Brooks wrote, a Mark Hellinger production directed by one of those people Edward Dmytryk eventually would name before the House Un-American Activities Committee. The film, of course, would be the still-powerful Brute Force, the director, Jules Dassin.

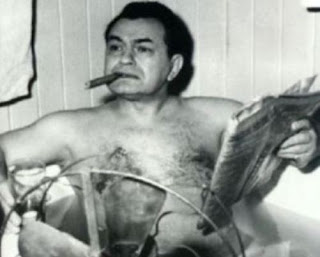

John Huston wasn't happy. Producer Jerry Wald called him, excitement in his voice, to tell him he'd secured the rights to Maxwell Anderson's Broadway play Key Largo for Huston to direct. This didn't thrill Huston, who thought the play gave new meaning to the word awful. Written in blank verse, Anderson's play concerned a deserter from the Spanish-American War. People at a hotel do get taken hostage, but by Mexican hostages. Essentially, Huston tossed the play in the trash bin. Huston hired Brooks to co-write an in-title only version and, still pissed at Wald, barred him from the set. Part of Huston's anger stemmed from the HUAC nonsense, (His outrage would drive him to move to Ireland for a large part of the 1950s.) so he couldn't stomach adapting a play by Anderson whom he considered a reactionary because of his hate of FDR. Despite Huston's distaste for the project, he

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.While I would have liked to have viewed more of Brooks' work that I've never seen (and to re-visit some which I have), time and availability, combined with his prolific nature and the industry's increasingly cavalier willingness to let both old and recent films fade into oblivion, proved to be a problem. After Huston's generosity, Brooks' directing debut would arrive two years later. Four films where Brooks worked

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.

enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.With 1955, Brooks wrote and directed the first film that truly garnered him an identity as more than a writer who directs but as a director with Blackboard Jungle, a film that admittedly manages to look both dated and timely simultanouesly, First, as so many old films did, it had to start with a long scroll explaining that American schools maintain high standards, but we need to worry about these juvenile

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk.

desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk. Tweet

Labels: blacklist, Bogart, Capra, Cary, Dassin, Doris Day, Edward G., Fiction, Fitzgerald, Fuller, Ginger Rogers, Glenn Ford, Hemingway, Huston, Lancaster, Liz, Mazursky, Poitier, Robert Ryan, Widmark

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Centennial Tributes: Jules Dassin Part II

By Edward Copeland

As we dive into the second half of this tribute to Jules Dassin, we're on an uphill climb artistically and a downhill slide personally as we talk about when he made his best films, including two out-and-out masterpieces, and when the witch-hunting politicians froze him out of movie work by getting Hollywood to blacklist him because of his youthful flirtation with communism. Never mind that he resigned from the Communist Party soon after joining when Stalin signed his 1939 pact with Hitler, once a commie, always a commie, right? At least that was the attitude then. We haven't reached that point yet. First, following making the great Brute Force, Dassin re-teams with producer Mark Hellinger for The Naked City, a landmark because it was the first sound film to shoot entirely in New York. Henry Hathaway had filmed some scenes of 1945's The House on 92nd Street on the streets of New York, but not the entire movie. Another film had shot partly on the streets of New York, but The Naked City became the first movie to film its entire production there. If you started here accidentally and missed Part I, click here.

Hellinger's role in The Naked City extended beyond producing — he also narrated the film which, to me at least, turns out to be a demerit at times. In his 1948 New York Times review, Bosley Crowther, mixed on the movie overall, referred to the narration as "a virtual Hellinger column on film." Not all the narration is cringeworthy (Two examples: "How many things this sky has seen that man has done to man"; "Milk! Isn't there anything else for ulcers except for milk?") Some come off fine such as when

Hellinger notes, "There's a pulse to a city that never stops beating." When the narration grates the most are the times when it sounds like a talkative moviegoer asking their companion annoying questions such as, "Is Henderson the murderer? Did a taxicab take him to the Pennsylvania Railroad Station? Who is Henderson? Where does he live? Who knows him?" The movie itself starts with an overhead shot of the city skyline as Hellinger waxes on about the city as the daytime shots turn into nighttime images and he tells us, "This is the city when it's silent or asleep, as if it ever really is." After his narration introduces us to various inhabitants of the city who work nights, he also shows us people resting at home or out on the town (cleverly introducing people who will be major characters later without pointing that out) "And while some people work and most sleep, others are at the close of an evening of relaxation — " We see a night club getting ready to close and its attendees departing before the camera switches to a young woman's apartment where we see her being murdered by two men. "And still another — is at the close of her life." The killers try to fake her death as a bathtub drowning and we see the movie's destination at last. After some more wandering around the city the next morning (including one killer getting drunk and nervous about the crime and his co-conspirator offing him and dumping his body in the river), once the dead woman's maid discovers her body, they show a particularly nice sequence of the chain of calls through switchboard operators going from hospital to a police precinct to the medical examiner before finally ending up at the homicide squad.

Hellinger notes, "There's a pulse to a city that never stops beating." When the narration grates the most are the times when it sounds like a talkative moviegoer asking their companion annoying questions such as, "Is Henderson the murderer? Did a taxicab take him to the Pennsylvania Railroad Station? Who is Henderson? Where does he live? Who knows him?" The movie itself starts with an overhead shot of the city skyline as Hellinger waxes on about the city as the daytime shots turn into nighttime images and he tells us, "This is the city when it's silent or asleep, as if it ever really is." After his narration introduces us to various inhabitants of the city who work nights, he also shows us people resting at home or out on the town (cleverly introducing people who will be major characters later without pointing that out) "And while some people work and most sleep, others are at the close of an evening of relaxation — " We see a night club getting ready to close and its attendees departing before the camera switches to a young woman's apartment where we see her being murdered by two men. "And still another — is at the close of her life." The killers try to fake her death as a bathtub drowning and we see the movie's destination at last. After some more wandering around the city the next morning (including one killer getting drunk and nervous about the crime and his co-conspirator offing him and dumping his body in the river), once the dead woman's maid discovers her body, they show a particularly nice sequence of the chain of calls through switchboard operators going from hospital to a police precinct to the medical examiner before finally ending up at the homicide squad.

The Naked City follows the investigation of that young lady's murder in an almost documentary style. Originally, Hellinger intended to use Homicide as the title but then decided to borrow The Naked City from the books of photographs by famous crime scene photographer Weegee, whose life was fictionalized in the 1992 film The Public Eye starring Joe Pesci, because he wanted the movie to have the feel of Weegee's photos. Playing the men leading the investigation were Barry Fitzgerald as Det. Lt. Dan Muldoon, the veteran with two decades of experience, and Don Taylor as Det. Jimmy Halloran, the greenhorn who'd only been working homicide for three months. Muldoon always has to explain to Halloran the right way to solve a case such as the one they are in, giving Fitzgerald the chance to say things like "That's the way you run a case, lad — step by step" and sound even more Irish than usual as he does it. When

they determine that the murder had to be committed by two people, Muldoon pins it on "Joseph P. MacGillicuddy," his version of John Doe. Since The Naked City strives for realism, one thing sticks out that I tend not to notice in other pre-1966 police movies or TV shows: There were no such things as Miranda rights so you never hear anyone told, "You have the right to remain silent, etc." The fine cast also includes Howard Duff, reuniting with Dassin from Brute Force, as a compulsive liar who was involved with both the dead woman and her best friend (Dorothy Hart). If you look closely, the film overflows with familiar faces in brief, mostly uncredited roles including Paul Ford, John Marley, Arthur O'Connell, David Opatoshu and, making their film debuts, Kathleen Freeman, James Gregory and John Randolph. There also is a very funny scene where Halloran seeks information from a sidewalk store clerk selling soda on the whereabouts of the suspected killer and the vendor is played by the comic great Molly Picon. However, the film's true star is New York.

they determine that the murder had to be committed by two people, Muldoon pins it on "Joseph P. MacGillicuddy," his version of John Doe. Since The Naked City strives for realism, one thing sticks out that I tend not to notice in other pre-1966 police movies or TV shows: There were no such things as Miranda rights so you never hear anyone told, "You have the right to remain silent, etc." The fine cast also includes Howard Duff, reuniting with Dassin from Brute Force, as a compulsive liar who was involved with both the dead woman and her best friend (Dorothy Hart). If you look closely, the film overflows with familiar faces in brief, mostly uncredited roles including Paul Ford, John Marley, Arthur O'Connell, David Opatoshu and, making their film debuts, Kathleen Freeman, James Gregory and John Randolph. There also is a very funny scene where Halloran seeks information from a sidewalk store clerk selling soda on the whereabouts of the suspected killer and the vendor is played by the comic great Molly Picon. However, the film's true star is New York.

While The Naked City gets lumped into the noir category, personally I don't think it belongs there. While The Naked City turns out mostly fine, the film doesn't approach the greatness of Brute Force or Dassin's films that follow. What makes The Naked City stand out from other films has little to do with its story or acting, but its landmark use of New York — and I mean the real New York, not Toronto. Dassin employed several tricks to film on the streets without crowds getting in the way because word always leaked as to where they would be shooting. In one of the Criterion interviews, he tells of a fake portable newsstand they had to conceal the camera as well as a flower delivery van with a mirror on the side that they could see out of but outsiders couldn't see in. They also employed jugglers to distract onlookers so they wouldn't disrupt shooting.

On the DVD interview, Dassin said his favorite method was to place this guy a bit down the street from where they were shooting, have him climb up a pole, wave a flag and give patriotic speeches. While he mesmerized crowds, the film crew got their work done. Some of that location shooting still amazes. Taylor as Halloran does most of the running throughout the city, on and off subways and buses, past landmarks still familar today and, most especially, the climactic foot chase after the killer that leads to awesome shots on the Williamsburg Bridge. The movie ended up winning the Oscar for best black & white cinematography for William H. Daniels and best film editing for Paul Weatherwax. Now, Dassin contended that elements of the films that put more of an emphasis on class differences within the city and other social issues were cut from the film before release. In many interviews, he said that by the time filming had been completed, rumor already had begun to swirl that he might be called before HUAC to testify about his former membership in the Communist Party. He also didn't believe Hellinger would make those cuts, mainly because Universal didn't want to release The Naked City because they didn't know how to market it. However, Hellinger's contract with the studio had a clause requiring them to release it — and a good thing that it did because three months before The Naked City finally did reach theaters, Hellinger died of a heart attack at 44, another reason Dassin doubted the cuts were his. To paraphrase the film's famous closing line of Hellinger narration, "There are eight million stories from the Hollywood blacklist. This just leads to a much bigger one."

Before Dassin found a new home in Hollywood, he finally got that chance to direct some theater again, staging two Broadway productions in 1948. First, he directed the original play Joy to the World by Allan Scott, the screenwriter of six Astaire-Rogers musicals including Top Hat and Swing Time as well as other films. The comedy takes aim at Hollywood and the difficulty one has maintaining his integrity in the movie business. The play, which ran from March 18 to July 3 at the Plymouth Theatre, also has a strong plea for intellectual freedom and against censorship. Produced by John Houseman, its cast included Morris Carnovsky, who would appear in Dassin's next film and on the blacklist, being named by both Elia Kazan and Sterling Hayden; Bert Freed, TV's first Columbo; and Marsha Hunt, who starred in two of Dassin's MGM films — The Affairs of Martha and A Letter to Evie. The second production was the musical Magdalena which ran from Sept. 20 through Dec. 4. The songs were by lyricists Robert Wright and George Forrest and composer Heitor Villa-Lobos. It was John Raitt's first show following Carousel and choreographed by the most influential yet least-known dance master Jack Cole, subject of an in-development musical project with its eye on Broadway today. One of his two assistant choreographers on Magdalena was Gwen Verdon.

When Dassin headed back west, Darryl F. Zanuck and 20th Century Fox came calling, seeking to sign him to direct A.I. Bezzerides' adaptation of his own novel Thieves' Market, renamed Thieves' Highway. Before that project got rolling, Dassin received an urgent phone call from Zanuck with a very important question: "Are you now or were you ever familiar with the fundamentals of playing baseball?" Dassin told him yes. In an interview recorded in New York in 2000 and on the Criterion Collection DVD of Rififi, shared this fun little anecdote. It seems that the MGM vs. Fox baseball game was coming up the following weekend and Fox was short a player and Zanuck wanted to see if Dassin could be the one. According to Dassin, he turned out to be the MVP of the game as Fox beat MGM, which apparently was an unusual occurrence. Dassin's agent called him in a rush, wanting to know if Dassin had signed the contract for Thieves' Highway yet. Dassin told him that he had. The agent told him that was too bad — after his performance in the ballgame, he could have negotiated him a higher salary for the film.

While The Naked City didn't really seem like noir to me, Thieves' Highway most definitely does, though it's noir in a setting I never imagined before — crooks run amok among those who sell fresh fruit and vegetables. Richard Conte stars as Nick "Nico" Garcos, a veteran who traveled the world following the war and brings home gifts from everywhere to his proud Greek family. His father Yanko (Morris

Carnovsky) is even joyfully singing a Greek song when his boy shows up unannounced, surprising him. (Interesting that as important as Greece will become in Dassin's life later that it's a distinct element of this film.) While the mood overflows with happiness in the Garcos house, Nick discovers that things haven't gone well during his absence when one of his presents turns out to be a special pair of shoes for his father and he urges him to try them on. There's a problem — Yanko can't wear shoes anymore. He rolls away from the table to reveal to his son that he no longer has legs. His father tells him the story about how he had a huge load of the season's first crop of juicy tomatoes and one of the biggest produce dealers on the San Francisco market Mike Figlia (Lee J. Cobb) had agreed to buy them but as he asked for his money, Figlia insisted they have a drink to celebrate first. That drink turned into more drinks and the next thing Yanko knew, he was on the side of the road under his wrecked truck minus his legs. Figlia claims he paid him and someone must have taken the money from the truck. To make matters worse, since he couldn't use the truck anymore, he sold it and the man he sold it to has stiffed him on payment as well. While Nick's mom (Tamara Shayne) tries to calm things down and argues that perhaps Figlia told the truth, Nick can tell that Figlia was lying and his dad never got paid. First though, he's getting the truck back.

Carnovsky) is even joyfully singing a Greek song when his boy shows up unannounced, surprising him. (Interesting that as important as Greece will become in Dassin's life later that it's a distinct element of this film.) While the mood overflows with happiness in the Garcos house, Nick discovers that things haven't gone well during his absence when one of his presents turns out to be a special pair of shoes for his father and he urges him to try them on. There's a problem — Yanko can't wear shoes anymore. He rolls away from the table to reveal to his son that he no longer has legs. His father tells him the story about how he had a huge load of the season's first crop of juicy tomatoes and one of the biggest produce dealers on the San Francisco market Mike Figlia (Lee J. Cobb) had agreed to buy them but as he asked for his money, Figlia insisted they have a drink to celebrate first. That drink turned into more drinks and the next thing Yanko knew, he was on the side of the road under his wrecked truck minus his legs. Figlia claims he paid him and someone must have taken the money from the truck. To make matters worse, since he couldn't use the truck anymore, he sold it and the man he sold it to has stiffed him on payment as well. While Nick's mom (Tamara Shayne) tries to calm things down and argues that perhaps Figlia told the truth, Nick can tell that Figlia was lying and his dad never got paid. First though, he's getting the truck back.

When he finds Ed Kinney (Millard Mitchell), the man who bought the truck, Nick demands the keys to the truck or the money. Kinney complains that he can't pay right now because the truck has been giving him fits but he needs it to pick up a load of golden delicious apples. Nick makes a deal that he'll be his partner to pick up the apples and take them to San Francisco for the sale. The one hitch — Kinney already had a deal set with two guys Slob and Pete (Jack Oakie, Joseph Penney) so Kinney has to make up a story about how he can't make the run. The men go away disappointed — but they also tail him and see that he's lying and make it a point to harass them. If Mitchell looks familiar, he's probably best known for his role three years later as movie exec R.F. Simpson in Singin' in the Rain. Mitchell's career was cut short. A heavy smoker, lung cancer claimed his life at the age of 50 in 1953. Another interesting tale that comes out of the Dassin interviews on DVD is that Oakie, the longtime comic actor who scored an Oscar nod for his Mussolini spoof in Chaplin's The Great Dictator, was completely deaf when he made Thieves' Highway, something that Dassin didn't realize for weeks because Oakie was so good at picking up cues from other actors and never missed his mark or messed up a take. After Kinney and Nick team up, the first portion of the film concentrates on the long haul to San Francisco after they pick up the apples with Nick driving the decrepit truck, Kinney following in another and Slob and Pete harassing them along the way. As Dassin said, the enemy for these men is fatigue and drivers employed many tricks to stay wake on the roads at night.

After a near disaster, Kinney decides it's best if he and Nick switch trucks, letting him, the more experienced driver, try to hold it together while Nick takes the better rig with the first half of the load on to San Francisco. As in The Naked City, Dassin breaks some ground here by doing some amazing location shooting in San Francisco's market area with crowded streets and lots of activity. When we

arrive there, that's when Cobb appears playing the most diabolical produce salesman in the history of film. Cobb's centennial was Dec. 8, but I got so backed up with other projects I wasn't able to do a proper salute to this towering actor. In the 2005 interview on the DVD, Dassin said that Cobb truly "enjoyed his villainy." During the work on this piece, I uncovered more and more names of actors and directors who named names before HUAC that I had never known about before. I mentioned Sterling Hayden earlier, which was news to me. I also didn't know about Cobb. It's odd

arrive there, that's when Cobb appears playing the most diabolical produce salesman in the history of film. Cobb's centennial was Dec. 8, but I got so backed up with other projects I wasn't able to do a proper salute to this towering actor. In the 2005 interview on the DVD, Dassin said that Cobb truly "enjoyed his villainy." During the work on this piece, I uncovered more and more names of actors and directors who named names before HUAC that I had never known about before. I mentioned Sterling Hayden earlier, which was news to me. I also didn't know about Cobb. It's odd how all the ire and bile aimed at people who did name names seemed to be reserved for Elia Kazan. In Cobb's case, the pressure on the actor when he was called to testify before HUAC had nearly brought his wife to a nervous breakdown so Cobb felt compelled to name names to preserve his wife's sanity. Regardless, that doesn't take away from the fact that Cobb was a great actor and not just anyone can turn a produce dealer into a plausible bad guy. Conte matches him well as the good guy without turning Nick into a bland opponent. When things heat up between Nick and Figlia and Figlia suggests they go off to his office, one man comments that Figlia will "eat that kid alive." A buyer named Midge who's seeking golden delicious apples and is played by Hope Emerson, who will be a memorable villain herself the following year as the women's prison matron in Caged, responds, "I'll take odds on the kid." One of Figlia's deceptive tricks against Nick involves utilizing a local hooker named Rica (played by Valentina Cortese, best known for her Oscar-nominated turn in Truffaut's Day for Night, in only her second English-language film and her first shot in the U.S, though her last name is spelled Cortesa). Rica keeps Nick occupied while his truck, which is stuck in front of Figlia’s stand because of flat tires, gets raided and has its apples sold off by Figlia. In the 2005 interview, Dassin told of how Zanuck was a very hands-on producer. Since Rica would inevitably turn out to be the proverbial hooker with a heart of gold who would end up aiding Nick, Zanuck insisted that they write in a part of "a bourgeois fiancée who betrays Nick" to justify the hero falling for the hooker. Barbara Lawrence played that role, Polly Faber.

how all the ire and bile aimed at people who did name names seemed to be reserved for Elia Kazan. In Cobb's case, the pressure on the actor when he was called to testify before HUAC had nearly brought his wife to a nervous breakdown so Cobb felt compelled to name names to preserve his wife's sanity. Regardless, that doesn't take away from the fact that Cobb was a great actor and not just anyone can turn a produce dealer into a plausible bad guy. Conte matches him well as the good guy without turning Nick into a bland opponent. When things heat up between Nick and Figlia and Figlia suggests they go off to his office, one man comments that Figlia will "eat that kid alive." A buyer named Midge who's seeking golden delicious apples and is played by Hope Emerson, who will be a memorable villain herself the following year as the women's prison matron in Caged, responds, "I'll take odds on the kid." One of Figlia's deceptive tricks against Nick involves utilizing a local hooker named Rica (played by Valentina Cortese, best known for her Oscar-nominated turn in Truffaut's Day for Night, in only her second English-language film and her first shot in the U.S, though her last name is spelled Cortesa). Rica keeps Nick occupied while his truck, which is stuck in front of Figlia’s stand because of flat tires, gets raided and has its apples sold off by Figlia. In the 2005 interview, Dassin told of how Zanuck was a very hands-on producer. Since Rica would inevitably turn out to be the proverbial hooker with a heart of gold who would end up aiding Nick, Zanuck insisted that they write in a part of "a bourgeois fiancée who betrays Nick" to justify the hero falling for the hooker. Barbara Lawrence played that role, Polly Faber.

In addition to Thieves' Highway's noirish elements, which basically get segregated to San Francisco once Nick arrives and Figlia and Rica join the film, the movie's other half covers Kinney's treacherous drive in the truck that's barely holding together. Dassin builds genuine suspense in these scenes, aided by Alfred Newman's score. His journey isn't helped by the constant taunting by Slob and Pete, but as he steers the truck through curvy, mountainous highways, the sequences seem to foreshadow what would come several years later in Henri-Georges Clouzot's The Wages of Fear. When the drive finally goes fatally wrong, the truck crashes and rolls down an embankment, apples going everywhere. Even Slob and Pete rush down, but it's too late as the truck bursts into flames. "From that angle, apples rolling down the hill into the camera. I said to myself, 'That's a good shot.' I think that's one of the shots I've enjoyed most in films I've made," Dassin said in 2005. One thing in Thieves' Highway that didn't particularly please Dassin was that Zanuck shot an entirely new ending that he didn't know about because he already was in London prepping Night and the City. When Nick finally gets his physical revenge on Figlia, Zanuck's ending added police coming in to make the point that people "shouldn't take the law into their own hands." However, given what Zanuck did for Dassin overall when the witchhunters came calling, he couldn't complain that much. When the shit really started to hit the fan, it didn't sound as if Zanuck was someone who would be as helpful as he was during Dassin's crisis. In 1949, word came down that HUAC was going to call Dassin to testify and Zanuck and other Fox executives had a meeting about "the problem." In the 2004 L.A. County Museum of Art interview, Dassin said that Zanuck told him, "He was going to step on my neck because I was a dirty red."

is to be a nice guy, but you can't make it.'" — Jules Dassin

As Dassin went on to tell in that 2004 interview, after Zanuck's "threat," he was surprised to find the producer at his front door — not something you'd expect from someone at Zanuck's level. He informed Dassin that he was flying to London the next day and handed him the novel Night and the City by Gerald Kersh. Dassin told Zanuck he couldn't rush off on a moment's notice like that — he had family

problems. Zanuck disagreed with the director, saying that he also had family needs and this could end up being the last film he ever made. Zanuck advised him to get shooting on the film as fast as he could and to do the most expensive scenes first so the studio wouldn't have an excuse to shut the production down. Dassin followed Zanuck's advice and was in London readying the shoot when he learned that he'd been called to

problems. Zanuck disagreed with the director, saying that he also had family needs and this could end up being the last film he ever made. Zanuck advised him to get shooting on the film as fast as he could and to do the most expensive scenes first so the studio wouldn't have an excuse to shut the production down. Dassin followed Zanuck's advice and was in London readying the shoot when he learned that he'd been called to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Zanuck informed the panel that he was abroad and got his scheduled hearing postponed. When Dassin was about two weeks away from the start of shooting on the film, Zanuck called. He asked Dassin if he agreed that he owed him one. Yes, he did owe him, Dassin said in the 2004 interview. Zanuck requested a favor — he wanted Dassin to cast Gene Tierney in a role. Dassin was confused, since there wasn't a role in the movie that she could really play, but Zanuck explained that a love affair had just ended very badly for the actress and she was almost suicidal. When she got in those states, Zanuck said, the only thing that snaps her out of it is work. Quickly, the role of Mary Bristol was written into the script of Night and the City and Tierney joined Richard Widmark and the rest of the talented cast in one of the two best films Dassin ever made. Kersh, the author of the novel the film was based on, did not agree. Dassin never admitted it until an interview in 2005, but Zanuck had encouraged him to everything in such a rush, he never read the book. Many years later, when he did, he could see why Kersh got mad — Night and the City the movie had no resemblance to Night and the City the novel whatsoever.

appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Zanuck informed the panel that he was abroad and got his scheduled hearing postponed. When Dassin was about two weeks away from the start of shooting on the film, Zanuck called. He asked Dassin if he agreed that he owed him one. Yes, he did owe him, Dassin said in the 2004 interview. Zanuck requested a favor — he wanted Dassin to cast Gene Tierney in a role. Dassin was confused, since there wasn't a role in the movie that she could really play, but Zanuck explained that a love affair had just ended very badly for the actress and she was almost suicidal. When she got in those states, Zanuck said, the only thing that snaps her out of it is work. Quickly, the role of Mary Bristol was written into the script of Night and the City and Tierney joined Richard Widmark and the rest of the talented cast in one of the two best films Dassin ever made. Kersh, the author of the novel the film was based on, did not agree. Dassin never admitted it until an interview in 2005, but Zanuck had encouraged him to everything in such a rush, he never read the book. Many years later, when he did, he could see why Kersh got mad — Night and the City the movie had no resemblance to Night and the City the novel whatsoever.

I haven't read the novel but if the godawful 1992 film with the same title starring Robert De Niro and Jessica Lange hewed closer to its narrative, I'm glad that I haven't. If, on the other hand, the 1992 Night and the City just provides more evidence that nine times out of 10, when you try to remake a classic film, you only end up with the celluloid equivalent of diarrhea, Kersh should be grateful he died in 1968. I actually saw the disaster of a remake before I ever saw the original and once I saw the original, I couldn't believe that they were supposed to have come from the same source material. When ranking Dassin's films, I'm always torn between Night and the City and Rififi as to which I think is the greatest. Preparing for this tribute, I watched the films on consecutive nights. It's such a close call, but for today anyway, I give Rififi the slight edge. However, that doesn't mean I love Night and the City any less. What a script. What a cast. Every detail done to perfection. "Night and the city. The night is tonight, tomorrow night or any night. The city is London." Those are the words that open the film then we see Widmark's Harry Fabian running like hell through a square — and running will be what he's doing for a lot of the movie when he doesn't slow down long enough to try to make his Greco-Roman wrestling scheme work or to make time for Mary or listen to offers from the likes of Francis L. Sullivan's Philip Nosseross, a nightclub owner who resembles a more genial Jabba the Hutt, or his wife Helen (the wonderful Googie Withers, who just passed away in July), who wants her own action and to escape her husband.

When Night and the City opened in 1950, it depended where you lived what music accompanied Fabian's film-opening sprint. Britain, still recovering from the damage of World War II, had laws in place to ensure that it kept a certain amount of the profits of films made there

and provide workers jobs as well. As a result, there were two versions of Night and the City, and Dassin wasn't allowed to participate in the editing of either one — one because he wasn't British, the other because when he returned to the United States, he was banned from the 20th Century Fox lot. The British cut runs longer, adding some more character scenes, and contains a moodier score by Benjamin Frankel, who would go on to score John Huston's Night of the Iguana and Ken Annakin's Battle of the Bulge. The American cut, which Dassin says he prefers, has music composed by the great and prolific Franz Waxman, who composed many scores for Hitchcock

and provide workers jobs as well. As a result, there were two versions of Night and the City, and Dassin wasn't allowed to participate in the editing of either one — one because he wasn't British, the other because when he returned to the United States, he was banned from the 20th Century Fox lot. The British cut runs longer, adding some more character scenes, and contains a moodier score by Benjamin Frankel, who would go on to score John Huston's Night of the Iguana and Ken Annakin's Battle of the Bulge. The American cut, which Dassin says he prefers, has music composed by the great and prolific Franz Waxman, who composed many scores for Hitchcock including Rear Window as well as Billy Wilder's Sunset Blvd., and previously wrote the music for Dassin's Reunion in France. Waxman uses a variety of styles throughout Night and the City, parts with a jazz tinge, other moments matching the kinetic nature of various chase sequences. I've not seen the entire British version to know how it works, but I know that Nick De Maggio edited the American cut superbly. He also edited Thieves' Highway and would go on to cut another classic Widmark noir, Samuel Fuller's Pickup on South Street. Max Greene was responsible for the great cinematography. Some of the greatest movies seem as if they come into existence by accident. When you consider what a rush job Night and the City was, how Dassin didn't even read the book (though presumably the credited screenwriter Jo Eisinger had), how a role for Gene Tierney had to be created out of thin air and shoehorned into the story at the last minute, how a lot of the roles had to be cast with British actors by law and Dassin didn't know any (one of his casting directors turned out to be Douglas Fairbanks Jr.) and that Zanuck, who liked to meddle with his directors' pictures, didn't reshoot anything or change the editing when he really could have since Dassin was barred from the editing room because of the blacklist, it's a fucking miracle how brilliantly Night and the City turned out. Some things are just fucking meant to be. Even with the character of the huge old Greco-Roman wrestler Gregorious. Dassin drew a picture of a wrestler he'd seen once and said that's how he envisioned the person they got to play the part. Someone recognized the drawing as Stanislaus Zbyszko, but thought he was dead. Another person knew that Zbyszko actually was not only alive but had a farm in Missouri. They contacted him and he ended up playing the part of Gregorious. At a moment of professional and personal crisis for Jules Dassin, the stars truly aligned when it came to Night and the City.

including Rear Window as well as Billy Wilder's Sunset Blvd., and previously wrote the music for Dassin's Reunion in France. Waxman uses a variety of styles throughout Night and the City, parts with a jazz tinge, other moments matching the kinetic nature of various chase sequences. I've not seen the entire British version to know how it works, but I know that Nick De Maggio edited the American cut superbly. He also edited Thieves' Highway and would go on to cut another classic Widmark noir, Samuel Fuller's Pickup on South Street. Max Greene was responsible for the great cinematography. Some of the greatest movies seem as if they come into existence by accident. When you consider what a rush job Night and the City was, how Dassin didn't even read the book (though presumably the credited screenwriter Jo Eisinger had), how a role for Gene Tierney had to be created out of thin air and shoehorned into the story at the last minute, how a lot of the roles had to be cast with British actors by law and Dassin didn't know any (one of his casting directors turned out to be Douglas Fairbanks Jr.) and that Zanuck, who liked to meddle with his directors' pictures, didn't reshoot anything or change the editing when he really could have since Dassin was barred from the editing room because of the blacklist, it's a fucking miracle how brilliantly Night and the City turned out. Some things are just fucking meant to be. Even with the character of the huge old Greco-Roman wrestler Gregorious. Dassin drew a picture of a wrestler he'd seen once and said that's how he envisioned the person they got to play the part. Someone recognized the drawing as Stanislaus Zbyszko, but thought he was dead. Another person knew that Zbyszko actually was not only alive but had a farm in Missouri. They contacted him and he ended up playing the part of Gregorious. At a moment of professional and personal crisis for Jules Dassin, the stars truly aligned when it came to Night and the City.The ensemble does the best job at selling the movie, foremost Widmark as the smooth yet smarmy Fabian. You can see how some people buy into his dreams just as you easily as others see right through him. As Mary's friend Adam (Hugh Marlowe) so accurately describes him, "Harry's an artist without an art." Tierney does fine given that she's playing a role that really has no reason for being there. Herbert Lom manages to be both frightening and unctuous as a crooked wrestling promoter who still has concerns about his father, Gregorious (Zbyszko) when Fabian manages to bring him into the machinations. Above them all though are Sullivan and Withers as Philip and Helen, the husband and wife who don't quite know how they got together but can't figure out a way to split up. When Helen makes plans to pin her exit on Fabian's scheme, Philip warns, "You don't know what you're getting into." Helen knows deep down, but she doesn't care. "I know what I'm getting out of," she tells him. Night and the City, despite the turmoil going on on the outside, is by far the best film Dassin had made until that point. Some good ones will still come, but now he'll face the toughest time of the blacklist.

Tweet

Labels: Astaire, blacklist, Chaplin, D. Zanuck, Dassin, De Niro, Fuller, G. Tierney, Ginger Rogers, Hayden, Hitchcock, Huston, J. Lange, Kazan, Lee J. Cobb, Remakes, Truffaut, Widmark, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, December 09, 2011

Centennial Tributes: Broderick Crawford

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

In 1949, Columbia Pictures brought Robert Penn Warren’s classic novel All the King’s Men to the big screen in an adaptation that deviated a great deal from the source material (as most films are wont to do) but nevertheless made for a compelling movie about idealism and political corruption in telling the tragic story of the rise and fall of a populist demagogue named Willie Stark. In casting the film, director Robert Rossen first offered the role of Stark to John Wayne who — not surprisingly — turned down the part, thinking the script unpatriotic. Rossen then decided upon Broderick Crawford, a burly character actor whose prolific if undistinguished cinematic career was comprised of playing tough guys and Runyonesque hoods in vehicles such as Tight Shoes (1941) and Butch Minds the Baby (1942). The role of Willie Stark fit Crawford like a glove, however; he won an Oscar for his performance in King’s Men beating out the Duke, who also had been nominated that same year for his starring turn in Sands of Iwo Jima.

Crawford’s triumph for All the King’s Men has often acted as a litmus test where Academy Awards are concerned; many film historians and critics argue that the Best Actor Oscar should not have gone to someone whose movie career, with the exception of King’s Men and Born Yesterday (1950), was marked by admittedly one-note performances in B-pictures, alternately playing heroes and villains. Is the purpose of Academy Awards to single out meritorious individual performances, or are they largely recognition for an entire distinguished body of work? I suppose it matters very little in the final analysis, because there are no mulligans when it comes to Oscars: Crawford won his, and in all honesty I think it was most deserved. The actor, who would become one of Hollywood’s most cantankerous character thespians, was born 100 years ago today, and now is good as time as any to see if his stage, screen and television legacy holds up.

Broderick Crawford was born in Philadelphia in 1911 to a second generation of performers, vaudevillians Lester Crawford and Helen Broderick. The latter name is familiar to many classic film buffs that’ve seen the comedienne in such Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers vehicles as Top Hat (1935) and Swing Time (1936). Before her movie career, she and her husband were a successful comedy duo in vaudeville, with an act that occasionally featured their young son in small roles. Brod graduated from the Dean Academy in Franklin, Mass., (where he was a well-regarded athlete) and was accepted at Harvard but his further academic pursuits came to a halt when he dropped out after three months to find work in New York. He became a jack-of-all-trades (longshoreman, seaman, etc.) though eventually the show business bug consumed him and he landed a number of radio jobs in the 1930s; reportedly appearing from time to time on Flywheel, Shyster and Flywheel — the 1932-33 half-hour comedy series starring Groucho and Chico Marx.

With performing in his blood, Broderick made his Broadway debut in 1934 as a football player in She Loves Me Not (he had made his stage debut in the same production in 1932 in London, where his talents attracted the notice of Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, who in turn introduced him to Noel Coward) and later appeared in such productions as Coward’s Point Verlaine, Sweet Mystery of Life and Of Mice and Men. It was for the latter play that Crawford earned exceptional critical acclaim, though when it came time for Hollywood to do its adaptation Brod was overlooked for the part in favor of Lon Chaney, Jr. By that point in his show business career, Crawford had set stage work aside in favor of the movies; his film debut was in the Samuel Goldwyn-produced Woman Chases Man (1937; with Miriam Hopkins and Joel McCrea) and he continued to appear in such B-flicks as Submarine D-1, Undercover Doctor and Eternally Yours. On occasion, Broderick would land roles in “A” productions such as Beau Geste, The Real Glory, Seven Sinners and Slightly Honorable but his rough-hewn manner and less-than-matinee-idol looks (in later years he remarked that his cinematic countenance resembled that of “a retired pugilist”) usually relegated him to character parts in scores of shoot-‘em-up Westerns like The Texas Rangers Ride Again and When the Daltons Rode. He did, however, prove versatile and adept at humorous turns in films like The Black Cat (Brod’s actually one of the “heroes” in this horror comedy, teamed with cinematic toothache Hugh Herbert) and Larceny, Inc.; he supported Edward G. Robinson in this last one as the lunkheaded Jug Martin, who assists Eddie and Ed Brophy in their attempts to rob a bank by purchasing and operating a luggage store next to it. (A decade later, Crawford paid homage to Robinson by re-creating a role that Eddie G. had played in the 1938 crime comedy A Slight Case of Murder but unfortunately, Stop, You’re Killing Me can’t quite measure up to the original.)

Crawford’s film career was interrupted briefly by World War II; he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and while in Europe saw action in the Battle of the Bulge. He later was assigned to the Armed Forces Radio Network in 1944, where as Sergeant Crawford he fell back on his previous radio experience to serve as an announcer for Glenn Miller’s band. Back in Hollywood by 1946, Brod returned to the B-picture grind with occasional bright spots such as Black Angel, The Time of Your Life (as a melancholy policeman) and Night unto Night. His gig in All the King’s Men transformed him into a box-office draw and made him the most unlikely leading man since Wallace Beery; signing a contract with Columbia that same year, he also nabbed the plum role of tyrannical junk tycoon Harry Brock opposite Judy Holliday in Born Yesterday — a part that actor Paul Douglas had played to great acclaim on stage.

Crawford’s brilliant comic turn in Yesterday had an unfortunate side effect in that it earned him enmity from critics who have argued that, for the most part, he played variations of Harry Brock in practically every film in its wake. The success of both King’s Men and Yesterday nevertheless earned him considerable cache to appear in “A” productions such as Night People (1954) and Not as a Stranger (1955) —the latter film once described by one critic as “the worst film with the best cast.” His turn as Capt. “Waco” Grimes in Between Heaven and Hell (1956) features some of his best work, and his approach to the character may remind you of Col. Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. That same year, he surprised critics again by scoring as a petty thief seeking redemption in Federico Fellini’s Il Bidone.