Friday, May 18, 2012

Centennial Tributes: Richard Brooks Part I

By Edward Copeland

"First comes the word, then comes the rest" might be the most famous quote attributed to Richard Brooks, who began his life 100 years ago today in Philadelphia as Ruben Sax, son of Jewish immigrants Hyman and Esther Sax. He wrote a lot of words too — sometimes using only images. In fact, too many to tell the story in a single post. so it will be three. His parents came from Crimea in 1908 when it belonged to the Russian Empire. Like the parents of a great director of a much later generation and an Italian Catholic heritage, Hyman and Esther Sax also worked in the textile and clothing industry. Sax's entire adult working life revolved around the written word — even while he busied himself with other tasks. “I write in toilets, on planes, when I’m

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when

walking, when I stop the car. I make notes. If I am working at a studio, I work at the studio in the morning, then come home. I am really writing two days instead of one. After the studio, I have my second day (at home). I write whenever I can,” Brooks said in an interview with Patrick McGilligan for his book Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. After high school, he entered Temple University where he majored in journalism, though he left early when he realized the financial hardship that his tuition put on his parents. After drifting around the eastern half of the U.S. for a while by train, Sax returned to Philadelphia and got a job as s sports reporter at The Philadelphia Record where he first adopted the name of Richard Brooks. When he later got hired by The Atlantic City Press-Union, he met another reporter with an independent streak who would eventually make his way to Hollywood by the name of Samuel Fuller. Shortly after moving to New York for a job with that city's World Telegram newspaper, only leaving the sports beat behind for crime reporting. Brooks discovered that radio jobs provided bigger paychecks so he took a job at the 24-hour radio station WNEW, first as a disc jockey. "Played records 23 of those hours," McGilligan described in the introduction to his interview. Later, the station promoted him to news where he edited four news broadcasts a day newspaper jobs and wrote one. His work there led to a news job at NBC Radio's Blue Network where he also got to do commentary. At the same time, in 1938, Brooks tried his hand at playwriting, which led in 1940 to co-founding The Mill Pond Theater in Roslyn, N.Y., with David Loew. It's on that stage that Brooks made his debut as a director, taking turns with Loew helming productions at the summer theater. A falling out with other members of the theater sent Brooks to California where he worked for NBC Radio from the other coast. Among his duties was writing and directing the broadcast Richard Sands. Brooks also began writing a short story every day and reading it on air. “I’d written some short stories before, but none was published. Anyway, every day, another short story. Everything became grist for a short story. It began to drive me crazy…a different plotline every day. My ambition: write one story a week instead of a different story every day. In about 11 months, I wrote over 250 stories. I even devised a system whereby on Fridays I wouldn't have to write a short story. I called that day 'Heels of History.' I would take a fable and convert it. As a matter of fact, I used one afterwards in The Blackboard Jungle,” Brooks told McGilligan. Brooks gave the example of how he took the story of "Jack and the Beanstalk," citing how while he's portrayed as a hero, Jack's actually a dumb, bad kid who ignores his mother's order, shows little concern for an ailing fire and steal, even if it's from a giant. Granted, it doesn't appear to have been broadcast nationally but I wonder if Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine came across this when conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

conceiving Into the Woods?. Witches can be right, giants can be good… Brooks, like what happened when he learned radio paid more than newspapers, discovered in California that screenwriters earned bigger paychecks than broadcasters. He set up a meeting with George Waggner at Universal, where Waggner — who later would direct The Wolf Man and much episodic TV including many installments of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Batman — was the assistant producer of White Savage, a Maria Montez film directed by Arthur Lubin. Waggner asked if Brooks wrote because they desperately needed a rewrite. It was his first movie job and Brooks made "$100 (weekly) plus a day or two prorated, and they put my name on (the screen) as 'additional dialogue,'" Brooks told McGilligan. White Savage wasn't the first film Brooks worked on to be released though — two others and a serial came first. He also hung on to the NBC gig and got the chance to write for Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre. Brooks produced countless sentences and paragraphs and but still lacked a "written by" credit on a screenplay credit. Once he did and, later, when he directed, he'd impact filmmaking both during and beyond his life, often with social themes few would touch (though occasionally in a heavy-handed way). He also managed to write some novels on the side — while with the Marines during World War II, where he'd also crank out a couple of screenplays (including his first credited one on Cobra Woman, directed by Robert Siodmak and again starring Montez) and report for Stars & Stripes as well while learning about filmmaking from Frank Capra's motion picture unit and eventually on his own editing combat footage into documentaries while attached to the 2nd Marines, Photographic Unit. If the Allies only needed a typewriter to defeat the Axis, Brooks might have been a good option for the weapon. First comes the word…

Though Brooks' legend derives predominantly from his film legacy, he experienced his first rush of acclaim with the publication of his debut novel, written while stationed at Quantico at night in the bathroom, according to the account in Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks by Douglass K. Daniel. Several publishers rejected it until Edward Aswell at Harper & Brothers, who also edited Thomas Wolfe, agreed to take it — and he shocked Brooks further by telling him (after a few suggestions) they planned to publish in May 1945. This news flabbergasted Brooks who obtained a weekend pass to go to New York because Aswell insisted on informing him in person. Now Brooks had to return to Quantico where the top officers of the Corps about shit bricks when The New York Times published a big review of The Brick Foxhole soon after it hit shelves. (Orville Prescott's take was mixed, assessing it as compulsively readable but weak on characterization.) Its story of hate and intolerance within the Marines brought threats of court-martialing Brooks, since he'd ignored procedure and never submitted the novel to Marine officials for approval ahead of time. They wanted to avoid bad publicity, especially with all the good feelings as the war wound down. "There was nothing in that book that violated security, but their rules and regulations were not for that purpose alone," Brooks told Daniel. Aswell prepared to launch a P.R. counteroffensive with literary giants such as Sinclair Lewis and Richard Wright ready to stand by Brooks. In case you don't know the story of the novel, it concerns a Marine unit in its barracks and on leave in Washington. Through their wartime experiences, some of the men truly turned ugly, suspecting cheating wives and tossing hate against any non-white Christian. It turns out, though the real Marines let the matter drop, what bothered them

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

about the book wasn't the anti-Semitism or racist tendencies of the characters but the murder of a Marine some of the other Marines learn is gay. The U.S. Marines didn't want to promote the idea there might be homosexuals serving in the military. Ironically, they got their wish when The Brick Foxhole transferred to the big screen in 1947 as Crossfire. Brooks wasn't involved in the film version, but they made the murdered Army (The Marines even got to toss it off to another military branch entirely) soldier Jewish in the film. The film actually happens to be very good and was nominated for best picture and earned Robert Ryan his only Oscar nomination ever as supporting actor. What's even sadder is that Crossfire ends up being a much more powerful film against anti-Semitism than the creaky Gentleman's Agreement that took on the same subject that year and won best picture. If there weren't already enough ironic twinges in that story for you, Gentleman's Agreement, probably the grandfather of that tried-and-true staple "let a white guy be the hero of a story about another ethnic group" with Gregory Peck playing a Christian going undercover as a Jew to learn about anti-Semitism, won Elia Kazan his first directing Oscar. Edward Dmytryk, one of The Hollywood Ten, directed Crossfire, which dealt straight on with anti-Semitism and the effects of warfare on men. Then again, once Dmytryk served his jail time, he became the only one of the 10 to name names to HUAC because he wanted to work again.

While he didn't want to make a movie of The Brick Foxhole himself, another former newspaperman turned socially conscious film artist met with Brooks about working with his independent production company. At first, Mark Hellinger tried to lure Brooks away from Universal with the promise of doubling his salary if he'd adapt a play he liked into a movie, but before Brooks could consider that offer, Hellinger called with a more pressing matter. He was producing an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's famous short story The Killers. The problem: someone had to dream up what happened after the brief tale ends because it certainly wouldn't last 90 minutes otherwise. Hellinger flew Brooks out to meet Papa himself, but he didn't get much out of him but he did come up with an idea for what would happen after the story ends. Hellinger liked it and sent it to John Huston, who wrote the screenplay as a favor. Since both Brooks and Huston had contracts at other studios, neither got screen credits, so Ernest Hemingway's The Killers' official screenplay credit goes to Anthony Veiller, who received an Oscar nomination for best screenplay. He'd previously shared a nomination in the same category for Stage Door. The film also made a star out of Burt Lancaster, who would work with Brooks several times and be his lifelong friend. In fact, Lancaster would star in the next screenplay that Brooks wrote, a Mark Hellinger production directed by one of those people Edward Dmytryk eventually would name before the House Un-American Activities Committee. The film, of course, would be the still-powerful Brute Force, the director, Jules Dassin.

John Huston wasn't happy. Producer Jerry Wald called him, excitement in his voice, to tell him he'd secured the rights to Maxwell Anderson's Broadway play Key Largo for Huston to direct. This didn't thrill Huston, who thought the play gave new meaning to the word awful. Written in blank verse, Anderson's play concerned a deserter from the Spanish-American War. People at a hotel do get taken hostage, but by Mexican hostages. Essentially, Huston tossed the play in the trash bin. Huston hired Brooks to co-write an in-title only version and, still pissed at Wald, barred him from the set. Part of Huston's anger stemmed from the HUAC nonsense, (His outrage would drive him to move to Ireland for a large part of the 1950s.) so he couldn't stomach adapting a play by Anderson whom he considered a reactionary because of his hate of FDR. Despite Huston's distaste for the project, he

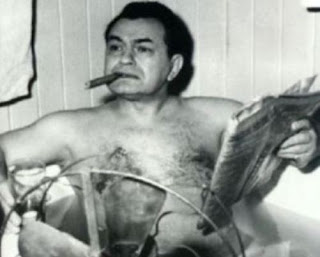

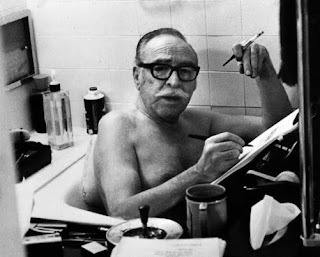

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.

turned it into a classic film with a little help from Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Lionel Barrymore, Claire Trevor in her Oscar-winning role and, last but certainly not least, Edward G. Robinson as exiled mobster Johnny Rocco, who likes to brag about the power he used to wield. "I made 'em — like a tailor makes a suit of clothes," he tells a former associate. Knowing the story of what happened prior to filming makes you chuckle when you see the credit that reads, "As Produced on the Spoken Stage." It's great to watch Robinson and Bogart go toe-to-toe. Rocco makes a particularly memorable first appearance, lounging upstairs in a hotel bathtub, looking in a way like a prediction of that famous photo of Dalton Trumbo that would be taken decades later. Bogart, updated to a returning WWII veteran, perfectly plays his role of Frank McCloud so that you never know if he's being savvy or scared of the crimnals terrorizing them. "You don't like it, do you Rocco, the storm? Show it your gun, why don't you? If it doesn't stop, shoot it," Frank says at one point, but when he gets a chance to grab a gun and take him out (though Rocco's men would certainly finish Frank afterward), he nonchalantly declares, "One Rocco more or less isn't worth dying for." The script's dialogue crackles and for additional fun touches we get a great Max Steiner score and the multitalented German émigré Karl Freund as cinematographer. The most remarkable thing that Huston did though was to invite Brooks to stay on the set during the film's shooting, something he'd never done as a writer and that he talked about in this YouTube video in 1985.While I would have liked to have viewed more of Brooks' work that I've never seen (and to re-visit some which I have), time and availability, combined with his prolific nature and the industry's increasingly cavalier willingness to let both old and recent films fade into oblivion, proved to be a problem. After Huston's generosity, Brooks' directing debut would arrive two years later. Four films where Brooks worked

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting

solely as a writer remained — the Paris-set spy thriller To the Victor; Any Number Can Play with Clark Gable as an underground casino owner advised by his doctor to get out of the business because of his heart disease; Mystery Street with detectives Ricardo Montalban and Wally Maher consult a Harvard forensics expert (Bruce Bennett) to solve a mystery when a decomposed body washes ashore; and Storm Warning, where model Ginger Rogers goes to visit her sister in a particularly unfriendly town and secretly witnesses a mob lynch a man that her sister (Doris Day) tells her was a reporter who denounced the KKK. Rogers' character gets a bigger shock when she realizes baby sis' husband participated in the lynching. After 1951, every film Brooks worked on he at least held the title of director, beginning with 1950's Crisis with Cary Grant as a doctor vacation with his wife in a small country when the dictator (José Ferrer) kidnaps them to force the doctor to treat his life-threatening condition. The doctor's ethics get tested by his oath and the idea that if he lets the man die, life for the country's people will improve. For a writing-directing debut, Brooks makes a pretty good start even if it doesn't come close to some of the films he wrote. His next four films as director and writer or co-writer I haven't seen, though I tried to watch the last one. The next film, The Light Touch (1952). starred George Sanders and Stewart Granger a collector of stolen art and an art thief, respectively, trying to get their hands on the masterpiece Granger stole and that his wife Pier Angeli stays busy counterfeiting enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.

enters their lives. At the time, Granger was married in real life to Jean Simmons, who would become Brooks' second wife about 10 years later. The next two films both starred Bogart. First came Deadline-U.S.A. with Bogie playing an investigative reporter trying to expose a gangster as his paper faces imminent closing followed by Battle Circus co-starring June Allyson where they played medical personnel at a MASH unit during the Korean War. The final film, which I almost watched, was The Last Time I Saw Paris, based on a story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and co-written by Brooks and the Epstein brothers, Van Johnson plays a former soldier returning to the city he liberated in the war, now despondent over his attempts to be a writer. He gets invited to parties with the city's beautiful people and finds one (Elizabeth Taylor) who enchants him. Unfortunately, the DVD transfer on Netflix’s rental copy proved abysmal. The Technicolor has faded beyond belief and it was filmed in an odd 1:75:1 spherical ratio, so every image looked distorted because they just flattened it full screen. After a few minutes, I had to shut it off. Apparently, it's a Warners Archive title now, but of course, they don't offer those for rental so the shitty DVDs will remain for people who don't believe in buying blind. I haven't caught his next two directing efforts either, but they stand out because they marked the first two times (and it only occurred three times) that Brooks directed screenplays written by someone else. In 1953, he directed Richard Widmark as a Korean War vet now serving as a tough drill instructor for new GIs bound for Korea while he's bitter that his request to return to Korea keeps being denied in Take the High Ground! In 1954, Brooks helmed Flame and the Flesh with Lana Turner as unlucky woman trying to get what she can for nothing visiting Europe who finds herself wooed by a gigolo.With 1955, Brooks wrote and directed the first film that truly garnered him an identity as more than a writer who directs but as a director with Blackboard Jungle, a film that admittedly manages to look both dated and timely simultanouesly, First, as so many old films did, it had to start with a long scroll explaining that American schools maintain high standards, but we need to worry about these juvenile

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a

deliquents before this gets out of hand. It gets off to a rockin' start — literally — with opening credits that can't help but make you think of the original beginning to TV's Happy Days as Bill Haley and the Comets get everything moving to "Rock Around the Clock" as new English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) arrives to work at all-boys high school North Manual Street. Most of the school overflows with miscreants, especially his class who start calling him "Daddy-O" to avoid pronouncing his name. (Though it's never been confirmed, many assume that the movie inspired Leiber & Stoller's lyric "Who called the English teacher Daddy-O?" in The Coasters' huge late '50s hit "Charlie Brown.") The ensemble Brooks assembled, including some of the "teens" who would make their names much later included Anne Francis as Dadier's pregnant (and, quite frankly, neurotic) wife; Louis Calhern as a veteran teacher left with nothing but cynicism and a desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk.

desire to beat the crap out of the punks; Richard Kiley as a nerdy math teacher with a love for jazz; Margaret Hayes as another new teacher who doesn't think about how she's dressing and nearly pays for it; Sidney Poitier as a student who appears to be one of the delinquents yet practices playing the piano and singing hymns; and Vic Morrow as the worst kid in the school, a downright criminal. Also, look for appearances by future writer-director Paul Mazursky as a student, Richard Deacon as a teacher and Jamie Farr as another student when he acted using the name Jameel Farah. While Blackboard Jungle offers much to praise, at times it comes off as too simplistic. It did dare to tackle bigotry and use the epithets. Sometimes, it feels eerily like the awful 1984 film Teachers. I kept expecting Calhern to turn out to be like the Royal Dano character and drop dead at his desk. I wonder what Brooks would have thought if he'd seen The Wire's fourth season. Blackboard Jungle earned Brooks his first Oscar nomination for best screenplay. Brooks' competition consisted of Millard Kaufman (who wrote Take the High Ground!) for Bad Day at Black Rock, Paul Osborn for East of Eden, Daniel Fuchs and Isobel Lennart for Love Me or Leave Me and Paddy Chayefsky, who wrote the teleplay that would be the basis for one of Brooks' 1956 films, for Marty. Chayefsky won his first Oscar. Nearly the entire cast excels in spite of some of the weaker parts of Blackboard Jungle (except Francis, burdened with a thankless role) but Morrow stands out in the ensemble as the worst punk. Tweet

Labels: blacklist, Bogart, Capra, Cary, Dassin, Doris Day, Edward G., Fiction, Fitzgerald, Fuller, Ginger Rogers, Glenn Ford, Hemingway, Huston, Lancaster, Liz, Mazursky, Poitier, Robert Ryan, Widmark

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, March 31, 2012

The World is Yours

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

Around my home base at Thrilling Days of Yesteryear, the “Gangster Trilogy” is the nickname assigned to the three movies that for many kicked off the crime film genre in the 1930s: Little Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and Scarface (1932). The first of these films starred Edward G. Robinson in what has commonly been called his “breakout” role, and Enemy did likewise for James Cagney…making both actors silver screen legends. Though there are variances in the plots of each movie, they feature a unifying theme of a racketeer who rises to the top of his profession stealing, killing and plundering all the way…only to achieve his comeuppance before the lights in the theater come up and the second show begins.

Scarface — which at the time of its release 80 years ago on this date was subtitled “The Shame of a Nation” — also made veteran stage actor Paul Muni a household name among theatergoers, though his starring turn in I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang equally boosted his cinematic stature (he received an Oscar nomination for the role, and was soon signed to a long-term contract by Warner Bros.) as well. While both Caesar and Enemy were Warner releases, Scarface was an independent production funded by the deep-pocketed Howard Hughes (and released by United Artists) and as such it’s often the overlooked feature of the three. (At one time, the movie even was withdrawn from release and didn’t resurface until 1979.) If it’s remembered at all today, it’s probably because it was the inspiration for the 1983 Brian De Palma cult classic with Al Pacino as the lead. But there’s much more than meets the eye in the Howard Hawks-directed original. (Much more.)

Crime boss “Big” Louis Costillo (Harry J. Vegar) is gunned down by a mysterious assailant shortly after he’s thrown one of his impressive shindigs, and as dedicated police inspector Ben Guarino (C. Henry Gordon) has been instructed to round up the usual suspects, he brings in Antonio “Tony” Camonte (Muni) and Guino “Little Boy” Renaldo (George Raft), two lieutenants who work for one of Costillo’s rivals, Johnny Lovo (Osgood Perkins). Lovo gets both men released with writs of habeas corpus, and we learn that Tony was responsible for croaking Big Louie at the behest of Lovo. Johnny then informs his now second-in-command that they’ll be taking over the beer concession on the city’s South Side, selling illegal suds to speakeasies and squeezing out those bars owned by rival gangs. Lovo has specifically ordered the ambitious Camonte to leave the North Side operation (run by a hood named O’Brien) alone, because that’s just asking for trouble.

Tony’s stock starts to rise in the beer rackets, and he finds himself constantly trying to attract the attention of Poppy (Karen Morley), Lovo’s girlfriend. He’s also earned the disapproval of his mother (Inez Palange), who scolds Tony’s sister Francesca (Ann Dvorak) when she accepts her brother's “dirty” money. Tony has a rather unhealthy (and suggestively incestuous) relationship with “Cesca” to the point that he gets enraged when he sees her in the company of eligible men. Finally, the impatient Tony makes a bid for the North Side operation by having Little Boy “eliminate” O’Hara in his flower shop, and this stunt earns him both the disapproval of Lovo and the enmity of Gaffney (Boris Karloff), the hood who takes over for the deceased O’Hara. Tony and his men wage a full assault on Gaffney and the other gangs…and seeing that Camonte is consolidating his power, Lovo orders a hit on Tony. The attempt fails, and Tony (with the help of Little Boy) exacts swift retribution.

The forces of good beat their collective breasts at the lawlessness exhibited by Tony, who is now king of all he surveys, and despite increased pressure by the newspapers and law enforcement, there seems to be little that will stop him. His downfall comes when he shoots and kills Little Boy after finding him in the same apartment with Cesca, not knowing that they have secretly wed. Returning to his stronghold (his sidekick Angelo, played by Vince Barnett, also has been killed as a result) as the police close in, Cesca arrives to Tony's surprise; she had planned to kill him for revenge but now realizes that “you’re me and I’m you” and she agrees to hold them off, but she’s felled by a stray bullet, and tear gas drives the now abandoned Tony out of his hideout to face Guarino and two detectives downstairs. Camonte agrees to come quietly, but bolts from his captors at the last minute and ends up gunned down in the street.

W.R. Burnett, the author responsible for the novel on which Little Caesar was adapted, was one of several credited scribes who supplied dialogue and continuity for Scarface, along with Seton I. Miller and John Lee Mahin (with uncredited contributions from producer Hawks and Fred Pasley) — but the bulk of the screenplay was penned by old newspaper hand Ben Hecht, who adapted Armitage Trail’s 1929 novel of the same name. “Scarface” also was the well-known nickname of racketeer Al Capone, and concerned that the film might possibly portray him in a negative light, he supposedly sent a couple of his boys around to see Hecht, hoping to discourage him from finishing the project. But Hecht, being a veteran ink-stained wretch, was not an easy man to scare…and according to legend, not only did he convince Capone’s goombahs that the movie was not about their boss, but he called upon them as consultants. (Further legend states that the end result pleased Al so much that he later obtained a print of the film for his very own.)

At the time of Scarface’s release, a vocal faction of individuals, concerned that others might be having more fun than they were, decried the product coming out of Hollywood…and the Hawks-Hughes movie was one on which they complained the longest and loudest. The accusations claimed the film glamorized gangsters and crime, and that this might be a bad influence on impressionable minds. Most of the time, this was true — it’s what was known as the “sin-and-salvation” approach to filmmaking. Cecil B. DeMille mastered this; presenting sequences of immorality and debauchery in his silent epics (which he got away with provided the characters received their just deserts at the end). Many of the later “message” movies that tried to warn innocent dupes away from sex or drugs (such as Reefer Madness) also took the same approach…and you often have to wonder how effective that was, showing kids having the time of their lives drinking and partying while frowning upont this type of behavior to be frowned.

I don’t think anyone would ever emulate the onscreen conduct in Scarface, however. The main character, Tony Camonte, isn’t a particularly admirable role model — as played by Muni, he’s positively primal; at times it’s as if someone shaved a simian and forced him into a nice suit. (Critic Danny Peary once observed that Muni’s Tony is essentially Fredric March’s Mr. Hyde, only without the fangs.) Camonte is constantly in a state of macho swagger, thinking himself sophisticated (but he’s not) and like a 1930s Donald Trump, judges the quality of what he buys by how much it costs. “That’s pretty hot” proves to be the highest praise he can bestow upon any item or individual, proving that Paris Hilton didn’t just come up with that asinine catchphrase by her lonesome. And like James Cagney’s Cody Jarrett in White Heat, Tony Camonte has some serious psychological problems. Man, has he got it bad for his sister Cesca. Of the film's many elements, the incest theme intrigues the most in what I consider to be the best gangster movie of the 1930s, addressed in the uncomfortable familial relationship between brother and sister Camonte. Hecht based the characters on the Borgia family, making actress Ann Dvorak a delightfully slutty carbon copy of Lucretia and while Muni received many of the critical kudos for his performance in the film, I think Dvorak walks away with the picture. Scarface made me a huge fan of the underrated actress; her tantalizing dance moves and naughty double entendres (not to mention that unmistakable glint she gets in her eye when she talks to Muni’s Tony) no doubt concerned the censors more than the violence.

I also became a Karen Morley fan because of this film, even though I’ll certainly concede that Dvorak gets the showier role and makes much more of an impression. (Morley was an underrated thesp, often on the receiving end of static from the industry about her personal life and politics, all coming to a boil in 1947 with her blacklisting in the motion picture industry after testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee.) As Poppy, the fair-weather bitch who switches her romantic allegiance to Tony when she’s able to read the tea leaves that Johnny Lovo hasn’t much of a future, I like her blasé responses to Camonte’s advances (“I’m nice with a lot of dressing”), and how at times it seems as if she’s having difficulty holding it in and not laughing at the jerk. Scarface also served as a breakout vehicle for actor George Raft, who had danced his way to fame on Broadway (under the tutelage of Texas Guinan) before venturing out to Hollywood to crash the movie business. Raft had appeared in films before Scarface but his “Little Boy” character in the picture really cemented his stature in the motion picture industry; during the 1930s he was the go-to individual for gangster portrayals alongside Cagney and Robinson. George was quite cozy with a number of real-life hoods (including Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky), which led many people to speculate that he actually might have been in the mob at one time (he wasn’t). A bit of business performed by Raft — flipping a nickel in the air and catching it while never looking at the coin — soon became a trademark and even provided a hilarious in-joke in 1959’s Some Like It Hot, in which he had a nice comic (and menacing) turn as hood Spats Columbo.

The actor who wasn’t quite as convincing as Raft playing a gangster was Boris Karloff, who also had a small role in Scarface as Gaffney. Personally, I welcome Boris in any movie but the man was just a little too cultured and refined to play a hood. Be that as it may, Boris does get a memorable death scene in which he’s gunned down by Muni and his mob while bowling…and though he leaves this world having bowled a strike, the “kingpin” symbolically takes a little time to fall before finally doing so. Symbolism plays a large part in Scarface; director Hawks came up with an interesting motif in that all of the gangsters who are “rubbed out” are designated as such with an “X” visible onscreen. Hawks thought this great fun, even to the point of offering crew members $200 for each creative suggestion to allow him to present this. Scarface originally had been scheduled to be released in September 1931, but producer Hughes still was getting grief from the Hays’ Office about the movie’s violent content. In an attempt to pacify the censors, the producer had Richard Rosson shoot an alternate ending, one in which Muni doesn’t die in a hail of bullets at the end but gets taken into custody, tried and convicted by a judge (who gives Muni’s character a lecture though you never see the actor) and sentenced to hang by the neck until he’s really most sincerely dead. (This scene also was shot without Muni’s participation; a double was used in long shots.) The censors weren’t wild about this ending either so Hughes finally threw up his hands and just did an end run around them, releasing the movie in states where there were no censorship boards. (It did great box office and received positive critical reviews.) The “alternate ending” has survived and is available on Universal’s 2007 DVD release…but seeing as how they also eliminated some of the more overt sexual attraction between the Muni and Dvorak characters, I’m glad Hughes stuck to his guns and kept Ending A.

That stand-alone disc release of Scarface provided the best news a classic film fan could get in that before that DVD, the only way you could purchase a copy of the Hawks original was on a 2003 “Anniversary Edition” box set of the 1983 Brian De Palma version…and that’s a purchase I simply wasn’t capable of justifying. There’s even more bad news on the horizon in that Universal has got another remake of the film in the works (this was announced last year) that will combine elements of the 1932 and 1983 films…but as a cinematic British barrister once observed: “Is that really desirable?” Classic film fans can take solace in that the one-and-only original is being looked after; having been added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 1994. Otherwise I’d have no other recourse than to respond with one of Tony Camonte’s most memorable quips: “Get out of my way, Johnny…I’m gonna spit!”

Tweet

Labels: 30s, blacklist, Cagney, De Palma, Edward G., Fredric March, Hawks, Hecht, Howard Hughes, Karloff, Movie Tributes, Pacino, Raft

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, December 25, 2011

A human life is strictly as frail and fleeting as the morning dew

"There was not a lot of dialogue. The titles were just to keep you up. It's the visual stimulation that hits the audience. That's the reason for film. Otherwise, we might as well turn the light out and call it radio." — Robert Altman

By Edward Copeland

Akira Kurosawa was 40 years old when he made the film that truly made moviegoers outside his native Japan take notice. Rashomon began filming July 7, 1950, and, in amazing turnaround time, debuted in Japan on Aug. 25 of that same year. However, the rest of the world didn't get to see Rashomon until 1951, starting with the Venice Film Festival in September where it won both the Golden Lion and the Italian Film Critics Award for best film. It unspooled next in the U.S., where it premiered 60 years ago today.

The Altman quote that I began this piece with comes from an introduction he taped for the Criterion Collection DVD release of Rashomon in 2002. While Altman certainly had it right about the visual wonders that Kurosawa summons in Rashomon, with the invaluable help of cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, with whom Kurosawa was working with for the first time, ironically (given the movie's subject), I

believe the other much-missed filmmaker's memory may have been faulty when it came to the amount of dialogue. Granted, Rashomon isn't overly chatty, but the film says nearly as much verbally as visually, not that I fault Altman — those images beckon you to lose yourself in them, even if subtitles get missed as a consequence. After all, Kurosawa himself admitted in his autobiography Something Like an Autobiography that he tried in Rashomon to recapture the spirit of silent movies that film had lost when sound came along. Criterion printed an excerpt of his memoir in the booklet that accompanied the DVD. "Since the advent of the talkies in the 1930s, I felt, we had misplaced and forgotten what was so wonderful about the old silent movies. I was aware of the aesthetic loss as a constant irritation. I sensed a need to go back to the origins of the motion picture to find this peculiar beauty again; I had to go back into the past," Kurosawa wrote. "In particular, I believed that there was something to be learned from the spirit of the French avant-garde films of the 1920s. Yet in Japan at this time we had no film library. I had to forage for old films, and try to remember the structure of those I had seen as a boy, ruminating over the aesthetics that had made them special. Rashomon would be my testing ground, the place where I could apply the ideas and wishes growing out of my silent-film research."

believe the other much-missed filmmaker's memory may have been faulty when it came to the amount of dialogue. Granted, Rashomon isn't overly chatty, but the film says nearly as much verbally as visually, not that I fault Altman — those images beckon you to lose yourself in them, even if subtitles get missed as a consequence. After all, Kurosawa himself admitted in his autobiography Something Like an Autobiography that he tried in Rashomon to recapture the spirit of silent movies that film had lost when sound came along. Criterion printed an excerpt of his memoir in the booklet that accompanied the DVD. "Since the advent of the talkies in the 1930s, I felt, we had misplaced and forgotten what was so wonderful about the old silent movies. I was aware of the aesthetic loss as a constant irritation. I sensed a need to go back to the origins of the motion picture to find this peculiar beauty again; I had to go back into the past," Kurosawa wrote. "In particular, I believed that there was something to be learned from the spirit of the French avant-garde films of the 1920s. Yet in Japan at this time we had no film library. I had to forage for old films, and try to remember the structure of those I had seen as a boy, ruminating over the aesthetics that had made them special. Rashomon would be my testing ground, the place where I could apply the ideas and wishes growing out of my silent-film research."

Know what tickles me about writing a tribute to this film? Rashomon liberates me to go into excruciating detail (if I desire) about scenes — for instance, I can describe the scene where The Woman (Machiko Kyô) turns on both her husband, the samurai (Masayuki Mori), and the infamous bandit Tajômaru (Toshirô Mifune), accusing them both of being weak and egging them on to fight to the death over who gets to keep her — because that's merely one version of what happened that led to the samurai's death. No character in the movie nor any viewer in the audience can declare with 100% certainty which version, if any, depicts the truth. Rashomon makes the need for giving readers spoiler warnings moot, praise be not only to Kurosawa but to his co-writer Shinobu Hashimoto and especially Ryûnosuke Akutagawa, who wrote the two short stories, "In a Grove" and "Rashomon," which inspired Kurosawa to make the film in the first place. Once Kurosawa had all his elements in place — cast, crew, shooting locations, set being constructed — even his assistant directors came to the director and admitted that the screenplay "baffled" them and asked Kurosawa to explain its meaning. In his autobiography, Kurosawa wrote, “'Please read it again more carefully,' I told them. 'If you read it diligently, you should be able to understand it because it was written with the intention of being comprehensible.' But they wouldn’t leave. 'We believe we have read it carefully, and we still don’t understand it at all; that’s why we want you to explain it to us.' For their persistence, I gave them this simple explanation:

"Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves. They cannot talk about themselves without embellishing. This script portrays such human beings–the kind who cannot survive without lies to make them feel they are better people than they really are. It even shows this sinful need for flattering falsehood going beyond the grave — even the character who dies cannot give up his lies when he speaks to the living through a medium. Egoism is a sin the human being carries with him from birth; it is the most difficult to redeem. This film is like a strange picture scroll that is unrolled and displayed by the ego. You say that you can’t understand this script at all, but that is because the human heart itself is impossible to understand. If you focus on the impossibility of truly understanding human psychology and read the script one more time, I think you will grasp the point of it.

"After I finished, two of the three assistant directors nodded and said they would try reading the script again. They got up to leave, but the third, who was the chief, remained unconvinced. He left with an angry look on his face. (As it turned out, this chief assistant director and I never did get along. I still regret that in the end I had to ask for his resignation. But, aside from this, the work went well.)" It saddens me the number of books I'll never find time to read. I wish I'd read Kurosawa's autobiography at a younger age — I have

so many unfinished and unstarted books lying around the house as it is. I digress. Rashomon may have puzzled Kurosawa's assistant directors, but I grasped it from the first time I saw it as a teen. Then again, perhaps geographical differences explain the comprehension gap. Sure — they shared a common country of origin with Kurosawa, but the director had immersed himself so deeply into Western culture through movies and literature, he might as well have hailed from the U.S. as Altman and I did, despite the large differences in our three ages. In fact, in my sophomore year of high school, not long after seeing Rashomon for the first time, my English teacher gave us an assignment to write something about our own time period based on the form of Letters from an American Farmer by J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, which we'd just studied in clsss. The teacher made no requirement that our piece be true or realistic so I titled mine Rashomon, American Style and fabricated an attack on a classmate and wrote five letters by different people, each giving different accounts of what took place, though my piece didn't dwell remotely in philosophical realms — it aimed solely at the satirical side of life. I'm proud to say I received an A on the assignment. With that little anecdote, I've finally remembered to give a broad outline of the plot of Rashomon, which I've neglected to do so far. As much as I do love Rashomon, it might not make the top five if I ranked my favorite Kurosawa films. I know it doesn't make the top four. For Altman, it and Throne of Blood were his two favorites. In that introduction, Altman said:

so many unfinished and unstarted books lying around the house as it is. I digress. Rashomon may have puzzled Kurosawa's assistant directors, but I grasped it from the first time I saw it as a teen. Then again, perhaps geographical differences explain the comprehension gap. Sure — they shared a common country of origin with Kurosawa, but the director had immersed himself so deeply into Western culture through movies and literature, he might as well have hailed from the U.S. as Altman and I did, despite the large differences in our three ages. In fact, in my sophomore year of high school, not long after seeing Rashomon for the first time, my English teacher gave us an assignment to write something about our own time period based on the form of Letters from an American Farmer by J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, which we'd just studied in clsss. The teacher made no requirement that our piece be true or realistic so I titled mine Rashomon, American Style and fabricated an attack on a classmate and wrote five letters by different people, each giving different accounts of what took place, though my piece didn't dwell remotely in philosophical realms — it aimed solely at the satirical side of life. I'm proud to say I received an A on the assignment. With that little anecdote, I've finally remembered to give a broad outline of the plot of Rashomon, which I've neglected to do so far. As much as I do love Rashomon, it might not make the top five if I ranked my favorite Kurosawa films. I know it doesn't make the top four. For Altman, it and Throne of Blood were his two favorites. In that introduction, Altman said:

"Rashomon is the most interesting, for me, of Kurosawa's films.…The main thing here is that when one sees a film you see the characters on screen.…You see very specific things — you see a tree, you see a sword — so one takes that as truth, but in this film, you take it as truth and then you find out it's not necessarily true and you see these various versions of the episode that has taken place that these people are talking about. You're never told which is true and which isn't true which leads you to the proper conclusion that it's all true and none of it's true. It becomes a poem and it cracks this visual thing that we have in our minds that if we see it, it must be a fact. In reading, in radio — where you don't have these specific visuals — your mind is making them up. What my mind makes up and what your mind makes up…is never the same."

Since I've avoided, not on purpose mind you, giving even a cursory synopsis or Rashomon's plot, I suppose now offers as good a place as any other to pen a brief summary for anyone unfamiliar with the film (in the unlikely event that their eyes remain fixed on this Web page this deep into the post). The title refers, according to Kurosawa's autobiography, the main gate to the outer precincts of Japan's 11th century capital city. As the movie opens, a Commoner (Kichijirô Ueda) seeks refuge from a heavy downpour of rain beneath the gate where a Buddhist Priest (Minoru Chiaki) and a Woodcutter (Takashi Shimura) sit visibly shaken, repeating variations of how they just don't understand and never have encountered a story as strange as this one. This intrigues The Commoner, who pumps both men for information about their rambling. "War, earthquakes, winds, fire, famine, the plague — years where it's been nothing but disasters. And

bandits…every night. I've seen so many men getting killed like insects, but even I have never heard a story as horrible as this," The Priest tells him. "This time, I may finally lose my faith in the human soul." When The Priest says that, The Commoner starts to lose interest. He just wanted to get out of the rain, not listen to a sermon, he responds, then The Woodcutter shares his involvement in the story and we get our first flashback, filmed as a long tracking shot through mountainous woods behind from behind the Woodcutter before it circles around him and continues as he walks toward it — stopping when he discovers a woman's white hat and veil hanging off a bush. He continues on and finds another item on the path until he finally stumbles upon the corpse of The Man and runs back to report it to the police. The Commoner learns that The Priest and The Woodcutter had come to the gate after being at the courthouse where they listened to the testimony of the famous bandit Tajômaru (Toshirô Mifune), who was apprehended by a Policeman (Daisuke Katô); The Woman (Machiko Kyô), who was discovered at a temple; and even The Man (Masayuki Mori), who may have been murdered, but tells his version of events through a Medium (Noriko Honma). No one's version of the events matches the others' completely and The Woodcutter believes everyone, even the dead man, lied. "Dead men tell no lies," The Priest insists. "It's human to lie. Most of the time we can't even be honest with ourselves," The Commoner replies, repeating nearly verbatim what Kurosawa told his confused assistant directors. Most character lists you'll find for Rashomon agree to call Chiaki and Shimura's characters The Priest and The Woodcutter, but you'll find many names Ueda's role such as The Commoner, The Peasant, The Beggar, etc. Within the movie itself, only Mifune's bandit receives a name, Tajômaru. Somehow though IMDb gives full names to The Man and The Woman who could be called The Husband and The Wife or The Samurai and The Wife, but never get proper names.

bandits…every night. I've seen so many men getting killed like insects, but even I have never heard a story as horrible as this," The Priest tells him. "This time, I may finally lose my faith in the human soul." When The Priest says that, The Commoner starts to lose interest. He just wanted to get out of the rain, not listen to a sermon, he responds, then The Woodcutter shares his involvement in the story and we get our first flashback, filmed as a long tracking shot through mountainous woods behind from behind the Woodcutter before it circles around him and continues as he walks toward it — stopping when he discovers a woman's white hat and veil hanging off a bush. He continues on and finds another item on the path until he finally stumbles upon the corpse of The Man and runs back to report it to the police. The Commoner learns that The Priest and The Woodcutter had come to the gate after being at the courthouse where they listened to the testimony of the famous bandit Tajômaru (Toshirô Mifune), who was apprehended by a Policeman (Daisuke Katô); The Woman (Machiko Kyô), who was discovered at a temple; and even The Man (Masayuki Mori), who may have been murdered, but tells his version of events through a Medium (Noriko Honma). No one's version of the events matches the others' completely and The Woodcutter believes everyone, even the dead man, lied. "Dead men tell no lies," The Priest insists. "It's human to lie. Most of the time we can't even be honest with ourselves," The Commoner replies, repeating nearly verbatim what Kurosawa told his confused assistant directors. Most character lists you'll find for Rashomon agree to call Chiaki and Shimura's characters The Priest and The Woodcutter, but you'll find many names Ueda's role such as The Commoner, The Peasant, The Beggar, etc. Within the movie itself, only Mifune's bandit receives a name, Tajômaru. Somehow though IMDb gives full names to The Man and The Woman who could be called The Husband and The Wife or The Samurai and The Wife, but never get proper names.While I didn't intend for this anniversary tribute to end up reading as if it were a paid advertisement for the Criterion DVD of Rashomon, the disc also contains excerpts from the documentary The World of Kazuo Miyagawa where the late director of photography explains how he pulled off the complicated dolly shot of the Woodcutter's trek through the woods as well as other tricks on Rashomon. The movie marked his first teaming with Kurosawa. The Woodcutter's walk was one of the very first shots scheduled, so Miyagawa set out to impress the director. He had the track built so the camera could do a 180-degree turn and then at the proper time had Takashi Shimura cross over the track to allow the camera to view the actor from the front. Some other Rashomon secrets that Miyagawa (and Kurosawa) share

in the excerpt involve what tricks they employed to get desired effects in the woods of the Nara, Japan, region where they filmed because the trees stood unusually tall. As a result, it interfered with Kurosawa's wish for shadows and light reflecting on the actors' faces at various times. Miyagawa used the same tool to help with both problems — mirrors. To deflect the distant rays of the suns on to the performers, Miyagawa stole the full-length mirror from the costume department and set it up so it would catch the sunlight and direct it exactly where Kurosawa sought to aim it. The director also sought to darken portions of the actors' faces with tree branches — which would have been fine if the cast all had been about 8 feet tall. Since they weren't, they jerry-rigged some mesh out of sight of the camera and attached branches to it. After that, they again made use of the mirror to reflect the shadows of the standalone branches where they wanted on the actors. One other detail the documentary excerpt includes came only from Kurosawa, who talked about the trouble of filming rain. He said that when you want to film rain, it always had to be a downpour otherwise, the rain never shows up on the film. Even then, in the case of Rashomon, he admits that they tinted the color of the rain to make certain it could be seen. Though Miyagawa and Kurosawa worked together well, they only teamed up two more times since the two men seldom worked at the same Japanese studio at the same time. Their next collaboration didn't occur until Yojimbo and, though he wasn't the d.p., Miyagawa did consult on the photography for Kagemusha. Since Miyagawa served as cinematographer on more than 80 features between 1938 and 1991, he did work with many of the biggest names in Japanese cinema at least once (often multiple times) including Kon Ichikawa, Takashi Imai, Hiroshi Inagaki, Teinosuke Kinugasa, Kenji Mizoguchi(including Sansho the Bailiff and Ugetsu), Yasujirô Ozu (on Floating Weeds) and Masahiro Shinoda, among many others.

in the excerpt involve what tricks they employed to get desired effects in the woods of the Nara, Japan, region where they filmed because the trees stood unusually tall. As a result, it interfered with Kurosawa's wish for shadows and light reflecting on the actors' faces at various times. Miyagawa used the same tool to help with both problems — mirrors. To deflect the distant rays of the suns on to the performers, Miyagawa stole the full-length mirror from the costume department and set it up so it would catch the sunlight and direct it exactly where Kurosawa sought to aim it. The director also sought to darken portions of the actors' faces with tree branches — which would have been fine if the cast all had been about 8 feet tall. Since they weren't, they jerry-rigged some mesh out of sight of the camera and attached branches to it. After that, they again made use of the mirror to reflect the shadows of the standalone branches where they wanted on the actors. One other detail the documentary excerpt includes came only from Kurosawa, who talked about the trouble of filming rain. He said that when you want to film rain, it always had to be a downpour otherwise, the rain never shows up on the film. Even then, in the case of Rashomon, he admits that they tinted the color of the rain to make certain it could be seen. Though Miyagawa and Kurosawa worked together well, they only teamed up two more times since the two men seldom worked at the same Japanese studio at the same time. Their next collaboration didn't occur until Yojimbo and, though he wasn't the d.p., Miyagawa did consult on the photography for Kagemusha. Since Miyagawa served as cinematographer on more than 80 features between 1938 and 1991, he did work with many of the biggest names in Japanese cinema at least once (often multiple times) including Kon Ichikawa, Takashi Imai, Hiroshi Inagaki, Teinosuke Kinugasa, Kenji Mizoguchi(including Sansho the Bailiff and Ugetsu), Yasujirô Ozu (on Floating Weeds) and Masahiro Shinoda, among many others.

Though the importance of the visual ingredients of Rashomon shouldn't be understated, I believe that ultimately the film's success depends on the two separate trio of performers. First, we have Shimura, Chiaki and Ueda as The Woodcutter, The Priest and The Commoner, essentially static characters that function as narrators of a sort as well as our surrogates, debating the philosophical ideas that the movie raises. The Priest struggles with his faith in light of what he has heard while The Woodcutter already has abandoned his on the basis of what he has heard and saw. The Commoner, who receives all the information about the events in the woods second hand, serves both as the audience surrogate and as

someone who long ago realized that the world doesn't function in black-and-white terms and that horrible things happen every day. When he first arrives, The Priest informs him that a man has been murdered. "So what? Only one? Why, up on top of this gate, there's always five or six bodies. No one worries about them," The Commoner responds. At a later point, The Priest seems unable to listen to any more. "I don't want to hear it. No more horror stories," The Priest pleads. The Commoner fails to react with the shock of the other two men. "They are common stories these days. I even heard that the demon living here in Rashomon fled in fear of the ferocity of man," The Commoner tells him. That part always reminds me whenever a news anchor reports on a workplace shooting somewhere and leads his or her report with someone being "shocked." How many of these over how many decades do these news readers have to talk about until they feel it's OK for them to drop the illusion of being shocked by them? I've also heard there's gambling at Rick's. All three actors serve their roles well but, as always, I'm amazed at the physical changes Takashi Shimura undergoes in his various Kurosawa roles. From a "modern" detective his own age in Stray Dog to The Woodcutter here, from the old dying civil servant in Ikiru to the main samurai in Seven Samurai — I'd be hard-pressed at any time to tell you how old he really was or what he looked like in everyday life. By cheating, I can find his age. He was 45 when he made Rashomon. He died in 1982 at 76.

someone who long ago realized that the world doesn't function in black-and-white terms and that horrible things happen every day. When he first arrives, The Priest informs him that a man has been murdered. "So what? Only one? Why, up on top of this gate, there's always five or six bodies. No one worries about them," The Commoner responds. At a later point, The Priest seems unable to listen to any more. "I don't want to hear it. No more horror stories," The Priest pleads. The Commoner fails to react with the shock of the other two men. "They are common stories these days. I even heard that the demon living here in Rashomon fled in fear of the ferocity of man," The Commoner tells him. That part always reminds me whenever a news anchor reports on a workplace shooting somewhere and leads his or her report with someone being "shocked." How many of these over how many decades do these news readers have to talk about until they feel it's OK for them to drop the illusion of being shocked by them? I've also heard there's gambling at Rick's. All three actors serve their roles well but, as always, I'm amazed at the physical changes Takashi Shimura undergoes in his various Kurosawa roles. From a "modern" detective his own age in Stray Dog to The Woodcutter here, from the old dying civil servant in Ikiru to the main samurai in Seven Samurai — I'd be hard-pressed at any time to tell you how old he really was or what he looked like in everyday life. By cheating, I can find his age. He was 45 when he made Rashomon. He died in 1982 at 76.

The second trio's task provides a more difficult acting challenge for Mifune, Kyô and Mori. The three performers aren't simply portraying The Bandit Tajômaru, The Woman and The Man — the film requires them to play widely divergent versions of those characters while still staying within the roles' essential frameworks. All three do well but, as you'd expect, Mifune stands out, though Kyô gives him a run for his money as The Woman. When Tajômaru gives his version of events, he testifies about The Woman's reaction, saying, "Her face turns pale. She stares at me with frozen eyes, her expression intense like a child's." However, when The Woman gives her own testimony, The Woodcutter and The Priest who were at the courthouse say she was docile and nothing like Tajômaru described. The Man's tale given through The Medium paints yet another portrait.

When The Woodcutter finally comes clean about witnessing the events instead of just finding The Man's body afterward as he said before, he draws a sketch of The Woman as completely manipulative and evil. Kyô excels at all these variations. There comes a moment in one version where she's lying on the ground sobbing and suddenly sits bolt upright and lambastes both men that will send a chill down your spine. Mifune's most consistent quality is The Bandit's maniacal laugh, but his face seems incapable of exhausting possible expressions. He can be menacing, romantic, insane, sad — you name it, he probably plumbs it as Tajômaru. They even go so far as to show the difference in fighting abilities in the different version. In Tajômaru's testimony, he claims that he and The Man had a spirited sword fight and that no man had fought him as well as this samurai so he felt he owed it to him that he die admirably. In the account told by The Woodcutter only to The Priest and The Commoner, The Woman forces the two men to fight and their swordplay is sloppy and not done very well. Altman says in his intro that when Tajômaru's interrogation takes place, we never see anyone asking him questions because the audience is doing the interrogation and he was on the money about that. It's not as clear in the testimony from The Woman and through The Medium, but Tajômaru looks right into the camera and speaks to us. In that respect, Kurosawa achieved his goal of going back to the past and recapturing the days of silent movies because in many ways, that's how what divides the film and its two trios. The three men at the gate reside in the talkie and while dialogue exists in the woods, much of what happens, each time that it happens, occurs on the actors' faces.

The pair of prizes Rashomon picked up in Venice were just the first two in a long string of honors and nominations the film received stretching from September 1951 through the spring of 1953. Before Rashomon officially opened on Christmas Day 1951, the always-and-forever mysterious National Board of Review, shortly after changing its name from The Illuminati, awarded Kurosawa best director and gave the movie best foreign film more than a week earlier. The Oscars didn't have a competitive foreign language film category until 1956

so at the ceremony for 1951 films (held in early 1952), Rashomon became the fifth foreign language film to receive an honorary Oscar from the Academy's Board of Governors "as the most outstanding foreign language film released in the United States in 1951." The previous four went to Vittorio De Sica's Shoeshine and The Bicycle Thief in 1947 and 1949, respectively; Maurice Cloche's Monsieur Vincent (1948) and René Clément's The Walls of Malapaga (1950). (Three additional foreign language films receive honorary Oscars before the regular category was added: Clément's Forbidden Games in 1952, Teinosuke Kinugasa's Gate of Hell in 1954 and Hiroshi Inagaki's Samurai, The Legend of Musashi aka Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto in 1955.) Apparently, Rashomon didn't make it to England until 1952, because it was for that year that it received a nomination for best film from any source from the British Academy Film Awards, handed out in spring 1953 (and not yet merged with the British TV Academy to form BAFTA). What doesn't make sense is that NBR and the Academy both recognized that Rashomon's U.S. release occurred in 1951. Somehow though when the 1952 Oscars rolled around, the Academy nominated production designer Takashi Matsuyama and set decorator H. Motsumoto for their black-and-white art direction. Forget for the moment the question of how they ruled Rashomon eligible again but consider that being eligible the Academy ONLY nominated it for art direction in 1952, that year The Greatest Show on Earth won best picture. Also for the year 1952, Kurosawa received a Directors Guild of America nomination, the only DGA nomination he ever received, though he lost to John Ford for The Quiet Man — one of the 17 other contenders in the category. Hell, we’re already spending too much time talking about this year’s awards, I’ll stop talking about awards six decades ago now.

so at the ceremony for 1951 films (held in early 1952), Rashomon became the fifth foreign language film to receive an honorary Oscar from the Academy's Board of Governors "as the most outstanding foreign language film released in the United States in 1951." The previous four went to Vittorio De Sica's Shoeshine and The Bicycle Thief in 1947 and 1949, respectively; Maurice Cloche's Monsieur Vincent (1948) and René Clément's The Walls of Malapaga (1950). (Three additional foreign language films receive honorary Oscars before the regular category was added: Clément's Forbidden Games in 1952, Teinosuke Kinugasa's Gate of Hell in 1954 and Hiroshi Inagaki's Samurai, The Legend of Musashi aka Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto in 1955.) Apparently, Rashomon didn't make it to England until 1952, because it was for that year that it received a nomination for best film from any source from the British Academy Film Awards, handed out in spring 1953 (and not yet merged with the British TV Academy to form BAFTA). What doesn't make sense is that NBR and the Academy both recognized that Rashomon's U.S. release occurred in 1951. Somehow though when the 1952 Oscars rolled around, the Academy nominated production designer Takashi Matsuyama and set decorator H. Motsumoto for their black-and-white art direction. Forget for the moment the question of how they ruled Rashomon eligible again but consider that being eligible the Academy ONLY nominated it for art direction in 1952, that year The Greatest Show on Earth won best picture. Also for the year 1952, Kurosawa received a Directors Guild of America nomination, the only DGA nomination he ever received, though he lost to John Ford for The Quiet Man — one of the 17 other contenders in the category. Hell, we’re already spending too much time talking about this year’s awards, I’ll stop talking about awards six decades ago now.