Tuesday, June 30, 2009

Two Fists, One Body

By Jonathan Pacheco

It’s been widely reported that on his first date with his eventual wife, President Barack Obama took Michelle to see Spike Lee’s electrifying film, Do the Right Thing. It’s not only possible, but likely that the thought-provoking movie affected the thinking of the man who would become this country’s first black president some twenty years later. Many may not admit it, but there was an unconscious Utopian consensus that the beginning of the Obama Era represented a devastating blow to racism in America. While it marks a historical step forward, rewatching Do the Right Thing reminds me how far we still have to go; the film has lost little of its power and relevance in 20 years as it presents complex characters capable of good and evil, and raises more questions than answers regarding our solutions to racism.

Do the Right Thing is razor thin on plot: all we have are situations. Brooklyn blazes in the hot summer and tensions — specifically racial — rise to an all-time high. Sal (Danny Aiello) opens his pizzeria just as he’s done every day for the last 25 years, but his son Pino (John Turturro) is fed up with the black and Hispanic patrons of the neighborhood, warning his brother Vito (Richard Edson) to never trust them, specifically the restaurant’s black delivery guy, Mookie (Spike Lee). A myriad of other characters populate this neighborhood, pontificating on stoops, playing in the streets, observing from the sidewalks.

It’s difficult for me to call Spike Lee “subtle” as his characters exhibit many of the same qualities made me fume during Paul Haggis’s Crash. I was just a toddler in 1989, but it’s hard for me to believe that so many people coexisting in the same area simply walked around all day throwing racial slurs in everyone’s face. Isn’t that what people bashed Crash for? For being unrealistically and offensively blatant in its portrayal of the people of Los Angeles? Working in Lee’s favor is the fact that, despite the filmmaker’s insistence that the whole city of New York existed under this climate at the time, his story only centers around a single neighborhood in Brooklyn. It’s much easier to believe that one small area could be so outwardly racist than it is to believe that all of Los Angeles is that way, as Haggis would have you believe.

So while Lee uses heavy-handed storytelling frameworks and techniques to provoke (with the racial slur montage being the chief example), he takes the blatant and makes it feel subtle by enabling each character to possess both racist and non-racist qualities. Pino does nothing but complain all day about the blacks that come into the restaurant, yet Mookie points out that all of his celebrity heroes are indeed black, from Magic Johnson to Prince. Da Mayor (Ossie Davis) rants at the local Koreans in the morning, but ends up being one of the sole voices of reason in the evening. Even Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), who seems to be a hardnosed menace with his boom box continuously blasting “Fight the Power,” shows some wisdom during his famous Love/Hate monologue.

More importantly, climactic character events don’t pop up out of nowhere. When Mookie breaks the dam by tossing the trash can into Sal’s window, it was not only the result of Raheem’s death, but also smaller, additional things. You must remember that throughout the entire film, Mookie’s been walking the line between Pino and the blacks, trying to keep the peace and not take offense at the man’s ignorance, but at the same time wanting to stand up for himself and his race. Also remember that, although Sal has generally been good to Mookie, even calling him a son, the owner of the pizzeria takes a liking to Mookie’s sister that makes the young man uncomfortable with his boss. By the time Lee shows Mookie rubing his face outside of the pizzeria, the mob raging over Raheem’s death, the weight of the entire day is finally pressing down upon him.

Because of the nature of the plot and the giant cast of vibrant characters, entire sequences don’t stand out nearly as much as the moments and monologues. Danny Aiello’s performance deserves its Oscar nomination, particularly for Sal’s conversation with Pino, as the father explains to his son why he’ll never move his restaurant. He points out that those kids, those young adults sitting out there in the neighborhood — they grew up on his food. They love his pizza, and that makes them valuable — not because of their business, but because they fulfill the old man’s purpose in life. Do some of them want him and his Italian family to get out of their predominantly black neighborhood? Sure. But most of them love the family and appreciate the service they provide. Aiello’s Sal has his own prejudices, but he’s intelligent and human enough to mostly ignore his own racism and that of others because he knows that there are more important things than skin color and countries of origin. I get the feeling that he hopes he can be an example to his sons and his patrons in that respect. What’s heartbreaking is that at the end of this conversation, Pino stomps out to scare off a pestering patron, completely ignoring his father’s words.

The most moving speech comes from the great Ossie Davis’s Da Mayor, the neighborhood’s mainstay drunk. He ambles through the streets flirting with Mother Sister (Ruby Dee) and dishing words of wisdom (ambiguously telling Mookie to “always do the right thing”), but when some teens heckle the old man, calling him a bum, his well-hidden anger bursts through. As he shares his stories of being unable to feed his starving children and wife, he does so with fire, fury, and guilt. Spike Lee incorporates themes of fathers unable or unwilling to provide in many films — from Crooklyn to He Got Game — but Davis takes this short soliloquy and carves such a painful, affecting, special moment out of the film.

However, the movie’s most famous speech belongs to Radio Raheem as he relates the theme-defining conflict between Love and Hate, symbolized by his giant brass knuckles. The young man tells of Love’s struggles with Hate, but also of Love’s ultimate victory. But through the tragic death of Raheem at the hands of negligent cops, Lee tells us that Love can’t always get the knockout. When Raheem falls to the ground dead, Lee frames the shot so that we only see his right hand — the one with the Love brass knuckles — lying there next to him, dead as well. And when Mookie has made his choice of violence shortly afterward, it’s with a yell of “HATE!” that he sends the trash can crashing through Sal’s window.

Now, some people still question whether Mookie “did the right thing,” claiming the film leaves this ambiguous. This view is fueled by the seemingly conflicting quotes that Lee adds at the end of the film — one from Martin Luther King, Jr. (representing the Love fist), stating that no violence is ever justified, and one from Malcolm X (representing the Hate fist), claiming that violence in self-defense isn’t necessarily violence — it can be seen as intelligence. But the question isn’t whether Mookie did the right thing by smashing the trash can into Sal’s window, inciting a riot that would burn the business to the ground. Lee has made it clear that he doesn’t question Mookie’s decision, as he’s said many times that only white people raise that question; black people seem to “get it” already. By smashing that window, Mookie chose Hate as a declaration of self-defense; they will not tolerate what happened to Radio Raheem. Not only is it intelligent in that it refuses to give the oppressors the upper hand, but I would argue that it benefits Sal and his family (seen by most as the enemy, despite the fact that they weren’t responsible for Raheem’s death). By leading the charge to tear down the pizzeria, Mookie, consciously or not, directs the hate-fueled energy of the mob towards a building, and not a human. Mookie could just as easily have thrown that trash can at Sal or Pino or Vito, and the crowd would have followed. Instead, the Italians are able to stand across the street in relative safety, the mob having no interest in them at all.

The true question that Lee asks is this: when is Love “the right thing,” and when is it Hate? Immediately after Raheem’s death, Mookie stood with Sal and his family, facing the mob in apparent union, but he finally decided that these circumstances called for him to choose the other side. The next morning, when Sal expresses his anger at Mookie’s choice to smash the restaurant window, Mookie shoots back with, “Motherfuck a window, Radio Raheem is dead.” Or, as Lee puts it, it’s a black man’s life vs. a white man’s property. Does Mookie’s decision solve everything? No. Vito, at one point feeling that Mookie was his only friend, now feels betrayed by Mookie, and Pino feels vindicated in his racist beliefs. Most of all, Sal has been betrayed after serving and loving the neighborhood, with his business of 25 years sitting in ashes. But a man’s life was carelessly taken. Hate was the right thing in that situation. “Motherfuck a window,” indeed.

The philosophies of Dr. King and Malcolm X aren’t meant to be presented as opposing, “one or the other” decisions. Lee believes that it’s important to incorporate both, as they are not mutually exclusive, just as the Love and Hate fists both belong to the same body. If there were any doubt, just look at the final image of the film as it fades to black: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X — the two fists — shaking hands, smiling.

Just like the Obama presidency, Do the Right Thing doesn’t contain the cure for racism; that was never Lee’s intention. The man just wants you to open your eyes and think about what you’re really seeing. These vibrant, well-played characters represent the problems that we still face in full force today. The eventual solution to racism will most likely contain ambiguity and shades of grey, but Lee challenges us to look at our individual situations, observe them, then do the right thing.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, John Turturro, Movie Tributes, Spike Lee

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, June 26, 2009

The Wright stuff

By Edward Copeland

After having sat so recently through the pointlessness of the "thriller" Taken, Tom Tykwer's The International engaged my brain and my senses more than it probably had any right to, but I'll take two hours of riveting, if muddled at times, intelligent thrillmaking to an hour of mindless violence (let's face it: Taken's first half-hour was just domestic squabbling to stretch out the running time) any day.

Tykwer, who had showed his stuff with films such as Run Lola Run and The Princess and the Warrior, teams Clive Owen and Naomi Watts as an Interpol agent and an investigator in the NYC district attorney's office trying to take down an international bank involved in some worldwide arms dealing. Get this: the film doesn't even try to shoehorn a romance between its attractive leads into its compelling story.

The film also works as a wonderful travelogue bouncing to recognizable sites around the world. I hate to keep going back to Taken since the plots of the two films are so different, but where Liam Neeson's character never runs into any roadblocks in his quest in that film, Owen and Watts seem to be thwarted every moment they start to get somewhere and it only ratchets up the suspense.

What's even braver of Tykwer and the script by Eric Warren Singer is that it has the guts for ambiguity in its ending.

All the actors are strong in the film, including supporting turns by Armin Mueller-Stahl and Jack McGee, but Owen really powers the enterprise. His obsessed, running-on-fumes agent with a checkered past is a great character turn instead of your standard leading man action hero turn. Watts doesn't get as much to do, but she does fine as well.

Tykwer's direction is taut and the film's fabled Guggenheim Museum setpiece deserves the kudos it received. It earns comparisons to Hitchcock, not because the film, as good as it is, is anywhere near his level but by using such a recognizable landmark for an exciting piece of cinema.

If the thought of a new Michael Bay-directed large-pieces-of metal-blow- things-up-real-good turd deafening theatergoers this weekend depresses you, stay home and save your ears and your brain cells by watching The International instead.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Clive Owen, Hitchcock, Liam Neeson, Naomi Watts

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Farrah Fawcett (1947-2009)

It seems as if most eras have their pinup girls and in the mid-'70s, that title undoubtedly belonged to Farrah Fawcett (who had a hyphenated Majors on the end of her name at the time). Fawcett lost her battle with cancer today at 62. The famous poster at the left sold a mind-boggling 8 million copies and led to her most famous role. Skyrocketing to superstardom as one of the original of Charlie's Angels in television's T&A era, like many sudden stars, she overestimated her fame and left the show after a single season, though she did return as Jill Munroe for a handful of episodes in later seasons as settlement of a breach of contract lawsuit. Her TV career didn't actually begin with that series though. She'd earlier appeared on Harry-O and The Six Million Dollar Man (with then-husband Lee Majors) as well as appearances on many other series and in feature films, most notably Logan's Run. Once she left Charlie's Angels, she tried her luck on the big screen, but critics and audiences were skeptical of the poster star as an actress or a movie star. She did work with talented performers (Jeff Bridges in Somebody Killed Her Husband, Charles Grodin and Art Carney in Sunburn and Kirk Douglas in Saturn 3), but none of it seemed to help. Around 1979, she and Majors separated and soon she dropped his last name.

She did get a hit with a film that didn't require acting opposite Burt Reynolds and Dom DeLuise in The Cannonball Run. Three years later though, she showed some acting chops when she went back to TV for the telefilm The Burning Bed, which earned her an Emmy nomination.

Two years after that, she repeated a success she'd had on stage with the film version of Extremities about a woman getting revenge on a rapist. She continued to prove her doubters wrong, earning two more Emmy nominations and making more features, good and bad, most notably Robert Duvall's The Apostle and Robert Altman's Dr. T and the Women.

Her perseverance was impressive given her off-screen travails with on-again/off-again love Ryan O'Neal, an abusive boyfriend and flaky talk show appearances before the devastating cancer that claimed her life. It was a long, hard climb from poster joke to respected actress, but Farrah Fawcett made it.

RIP Ms. Fawcett. You deserve the rest.

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Burt Reynolds, Duvall, Grodin, Jeff Bridges, K. Douglas, Obituary, Television

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, June 24, 2009

They have a hard time coming up with 5 some years

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts of Sciences in its continued quest to move closer to something like the MTV Movie Awards and away from its original mission when it was created to promote the quality of its industry has announced that it is doubling the number of the best picture nominees from five to 10 beginning this year.

Of course, in the early years sometimes the best picture category had as many as 12 nominees, but don't fool yourself into thinking there is some nobility involved in this move. Academy President Sid Ganis said part of the impetus was that ratings were up for the last Oscarcast which included tributes to popular films that weren't nominated. I have to ask though: How did viewers know ahead a time that the show was going to have these things and decide to tune in ahead of time? Let's just go the whole nine yards and have the Max Fischer players re-enact the picture nominees instead of clips.

While we're at it, let's start lobbying for the return of the Artistic Quality of Production category now.

Tweet

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

Ed McMahon (1923-2009)

While Ed McMahon will inevitably be connected with the man seated to his right in the photo above, McMahon also was an omnipresent figure throughout most of my lifetime right up until his death early today at 86, and it wasn't always as sidekick, though he may as well have invented the term and future dictionaries should include his picture next to the definition of the word.

His relationship with Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show lasted for 30 years beginning in 1962, but their partnership actually began five years earlier on a quiz show called Who Do You Trust? (which was originally called Do You Trust Your Wife?)

Even earlier TV work for McMahon included being the announcer on a show called Bandstand before it was later rechristened American Bandstand.

He did some acting as well, on episodic television and in film, including Butterfly, the movie that brought Pia Zadora into our consciousness and ruined the Golden Globes' reputation forever. Personally, I remembered his role most vividly in the original Fun With Dick and Jane.

Still, McMahon's greatest role was himself as sidekick, announcer, host and pitchman from TV's Bloopers and Practical Jokes, Star Search, promiser of large checks, Warren Beatty's remake of Love Affair, many sitcoms and perhaps my favorite, showing up drunk at Hank's bachelor party on The Larry Sanders Show.

Sadly, McMahon's final years were rough ones, caught up in the collapse of Countrywide and threatened with foreclosure on his home despite severe health and back problems until Donald Trump swooped in to help save the day.

RIP Mr. McMahon. Hi-yo!

Tweet

Labels: Carson, Larry Sanders, Obituary, Television, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post contains spoilers for both the novel, the movie and even the movie The Reader. You've been warned.

By Edward Copeland

When I reviewed the movie of Revolutionary Road, it seemed as if I was one of the few who found the film great. A lot of the criticism came from people stuck on the idea that it was merely another critique of suburban life when to me the setting was merely backdrop for its story. However, other negative reviews countered that it paled next to the novel upon which it was based by Richard Yates. Therefore, I took it upon myself to read the novel. I finished it quite awhile ago, but I wanted to re-watch the movie to refresh my memory and it just recently came out on DVD. Now that I've read the book and seen the movie twice and feel safe in saying that both are great, though the adaptation proves to be a curious one, being both fairly faithful to Yates' novel while at the same time deviating on crucial points.

The novel dives directly into the play that April Wheeler is starring in, beginning with a dress rehearsal that goes well. One of the reasons I wanted to

make sure to watch the movie again is that the book makes it clear that the play being performed is The Petrified Forest and so little is shown of the play in the film, I wanted to see if there was a switch. There doesn't seem to be, though why the performance goes so badly in the novel involves a misfire of the special effects machine guns, almost to comic effects and I can see why the filmmakers went another way because it would have been a type of humor completely out of place in Sam Mendes' film version.

make sure to watch the movie again is that the book makes it clear that the play being performed is The Petrified Forest and so little is shown of the play in the film, I wanted to see if there was a switch. There doesn't seem to be, though why the performance goes so badly in the novel involves a misfire of the special effects machine guns, almost to comic effects and I can see why the filmmakers went another way because it would have been a type of humor completely out of place in Sam Mendes' film version. After reading the novel, I do think (at least in my interpretation) that even the filmmakers missed the real point of Yates' book. On the DVD extras, director Mendes and screenwriter Justin Haythe emphasize that Revolutionary Road is about the splintering of a marriage and while that is certainly a theme and they recognize that the suburbs is just a setting, not the point, the novel made it clear to me (especially after reading Richard Price's introduction about Yates) the larger issue is mental illness. Marriage is certainly pivotal (especially since the novel looks more closely at the marriages of the neighbors the Campbells, who seem completely happy and content on the surface though Shep longs for April, and the older Givings, whose son is in a psych ward and where the husband has learned to deal with his wife's yammering simply by turning off his hearing aid.) It takes a while in the movie for Frank Wheeler (Leonardo DiCaprio) to become a sympathetic character, but you feel for him almost from the beginning of the novel which makes it clear from the outset that this isn't just a couple at the breaking point, it's a couple where the wife needs serious psychiatric help.

It also makes more sense as to why the character of John Givings (Oscar nominee Michael Shannon) is introduced and is viewed by April as some sort of truthteller. While I still love the movie, it gives the false impression that the failure of the play started the Wheelers' problems, when they began almost from the beginning since April has a hard time feeling anything. While the movie Frank asks her if she considered aborting either of their other two children, the book makes it clear that she did want to abort their first child, with Frank making the point that she's been pregnant three times and wanted to have abortions twice.

The other major difference between novel and film is that the book paints deeper portraits of the neighbors Shep and Milly and especially of Frank's mistress Maureen, including scenes with her roommate and the difficulties that Frank has ending the affair. Otherwise, I found the novel and film remarkably similar.

Certainly, the movie took some shortcuts for time reasons that the book didn't need to, but I got the same feeling from the book that I did from the movie, a feeling that must be common to most of Yates' works.

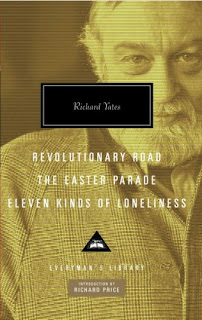

As Richard Price writes in the introduction of the Everyman edition of Revolutionary Road (which also includes The Easter Parade and the short story collection Eleven Kinds of Loneliness):

"...in his no-exit, unblinking honesty, in his bone-deep sorrowful conviction that loneliness is our inescapable lot, Yates pities his characters but has no choice but to doom them."

As in the movie, when April and Frank hit upon their Paris plan, you really want them to succeed, even though you know it's unlikely. I stick by my assertion that Kate Winslet won the Oscar for the wrong movie. What does it say about audiences that they are more willing to forgive a women who let Jews burn to death because she happened to be illiterate as in The Reader than they are a woman who needs psychological help?

Richard Yates' novel is well worth the read whether or not you've seen the movie (or whether or not you liked it for that matter). His prose is sharp, straight-forward and heartbreaking and overflowing with scenes that ring so truthful they hurt.

It's a great novel and while I still liked the film a lot the second time, I think the filmmakers didn't quite get at the essence of his story.

Tweet

Labels: Books, DiCaprio, Fiction, Michael Shannon, Winslet

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, June 22, 2009

All of Us Under Its Spell

By Jonathan Pacheco

It’s tempting to believe that nostalgia fuels most of the lasting appeal of The Muppet Movie as so many people literally grew up with these characters. I, however, watched the movie for the first time a few years ago as a nearly blank slate, enabling me to objectively see that, after 30 years, the film still captivates. Gushing with more puns than your grandpa, the film's intoxicating charm bursts from its anchor, Kermit D. Frog, and the virtuoso behind the Muppet, the late Jim Henson.

Meant as a “fictionalized account” of how the Muppets came to be, the film chronicles Kermit’s journey from an unassuming swamp to the glamorous streets of Hollywood, picking up Muppets along the way at clubs, fairs, churches, and used car dealerships.

The movie’s humor lives and dies by the pun, so from beginning to end, the jokes, idioms, and wordplays require enough sharpness to keep things fresh for the entire film. The Muppet Movie unabashedly dives into the silly and absurd, but it never feels lazy. The slapstick never overwhelms and the characters mix things up with self-aware humor that breaks the barrier between the film and the audience; Kermit points out running gags and characters literally pull out the screenplay for the film to find out what to do next.

The writing and delivery of these jokes and banter evoke the same vaudevillian sensibility that powered The Muppet Show (at the height of its popularity when the film came out in 1979), and three decades later, it seems to be a nearly lost comedy form. This film isn’t funny simply because the characters act silly, look funny, and yell a lot; this isn’t Spongebob. No, The Muppet Movie has actual jokes — with punchlines. When Kermit asks Fozzie to make a left at a fork in the road, he obliges, pointing out a 7-foot utensil jammed in the concrete. Kermit voices our thoughts: “I don’t believe that.” There’s something comforting and homey about the distinct “setup/payoff” rhythm to the exchanges between Fozzie and Kermit.

While Fozzie and the other Muppets serve their purposes in the film, everything hinges on Kermit’s character. Jim Henson’s performance as the frog not only carries the weight of the film, but it completely takes off with it. As played in The Muppet Movie, Kermit exhibits the sincerity and straight-forwardness of Jimmy Stewart, the articulation of Steve Martin, the stature and female prowess of Woody Allen, and the timing and charm of Billy Crystal before Billy Crystal even had them. Henson gives us a surprisingly emotive character, considering every facial expression must stem only from the frog’s flapping mouth. You can see this in the amazing mileage he gets out of pursed lips, in the way he rolls his fingers when Kermit enunciates “al-ee-gay-tors,” or in the slight tilt of the wrist and pressing of the fingers to let you know that the frog is nervous. Best of all, Henson’s Kermit has presence. When the frog walks into the room, even in his seeming meekness, he commands attention. He’s the definite leader of the group, and adoration comes his way both from the characters on the screen and the viewers in the audience.

Now, the average kid isn’t clever enough to get the majority of the puns or punchlines in this movie. I doubt they appreciate Henson’s masterful handwork behind the Muppet, and they probably don’t care too much for the cameos from Steve Martin, Mel Brooks, James Coburn, Richard Pryor or Orson Welles. This means that despite the nature of its characters, The Muppet Movie needs to connect on an adult level more than anything, otherwise the film is a failure. However, beyond the jokes and cameos that only the older crowd would understand, Kermit continues to shine as a protagonist who, despite being made of fabric, has a soul. As a bittersweet establishment of the character’s yearning for adventure and exploration, Kermit’s opening song, “The Rainbow Connection,” reaches further than the superfluous singing bogging down nearly every musical we see today. As the most dense bit of development in the entire film, “The Rainbow Connection” forms Kermit’s character completely and immediately. Paul Williams, co-songwriter on the film, had this to say about writing “The Rainbow Connection”:

"Kenny Ascher and I sat down to write these songs, and we thought ... Kermit is … he’s like "every frog." He’s the Jimmy Stewart of frogs. So how do we show that he’s a thinking frog, and that he has an introspective soul, and all that good stuff? We ... also wanted to show that he would be on this spiritual path, examining life, and the meaning of life.

The thing I love best about the lyric, I think, is that in the first two lines, you know that he’s been to the movies. “Why are there so many songs about rainbows? And what’s on the other side?” It tells you that he’s been exposed to culture. I think the song works because it’s more about questions than answers."

As this film’s equivalent to “Over the Rainbow,” “The Rainbow Connection” is a paramount example of how a song can explore a film’s character — silly or serious, Muppet or human — so thoroughly.

The weak point of the film lies in one half of its plot as Doc Hopper, creator of Hopper’s French Fried Frog Legs, sees Kermit’s talent and charisma and decides he must have the Muppet as the face of his franchise. The plot line gives the film a villain but he never feels like a relevant one. Kermit’s goals involve going to Hollywood so he can potentially make millions of people happy with his talents, and Hopper is trying to stop him every step of the way because...he wants to sell frog legs? The connection between Kermit’s altruistic motivations and Hopper’s exploitative intentions lacks the kind of effectiveness that would warrant such a prominent placement in the story. But as only a portion of the plot, it annoys more than it derails.

The Muppet Movie’s positives simply steamroll minor plot flaws with momentum generated by Jim Henson’s soaring performance as Kermit. Truly the heart of the film, Kermit, with all his sincerity and genuineness, appeals as much today as he did 30 years ago. Attributing the film’s charm to nostalgia ignores the fact that the bright, fast, clever humor and overall energy of the film will always appeal equally to the Muppet faithful and the newcomers.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, J. Stewart, James Coburn, Jim Henson, Mel Brooks, Movie Tributes, Musicals, Steve Martin, Welles

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

When time ceases to exist

By Edward Copeland

Back in the 1980s, when HBO had the comedy series Not Necessarily the News, they had a running gag on one episode about Ingmar Bergman where the punchline always was, "I think this represents death." My friends and I though this was funny, but we were early adolescents at the time and hadn't seen any Bergman films. Now that I have, and I love a great many of them, I still giggle at the line even though I know it's an oversimplification, though death's spectre does hover over the aging life of Professor Isak Borg in Wild Strawberries, which opened in the U.S. 50 years ago today.

In an interview, Bergman once said that by the time he was done making Wild Strawberries, the film really belonged more to Victor Sjöström, who played Borg. The film marked Sjöström's return from semi-retirement, but he already was a legend as the first true acting-directing star from the Swedish era. It's easy to see how Bergman came to that conclusion since

Sjostrom is in nearly every scene of the film either by his presence or from the perspective of his eyes. The story of Wild Strawberries is a simple one: Borg, a renowned professor and once a lauded physician, is about to receive an honorary degree. On the morning of the event, much to the chagrin of his longtime housekeeper/nanny (Jullan Kindahl), Borg decides that he is going to drive his old Packard to the event instead of flying to meet his son. The journey is more than just a road trip for the professor, but a metaphysical trek through his past as he questions what led him to this moment. When we first meet Isak, he is writing at his desk, his faithful dog lying at his feet, contemplating how evaluating behavior forced him to withdraw into old age and loneliness and turned him into a man who preferred the love of science to that of human interaction. This semi-solitary life has begun to take its toll on Isak, as his dreams have become odder and more frightening (and evidence of Bergman's own love of German Expressionism).

Sjostrom is in nearly every scene of the film either by his presence or from the perspective of his eyes. The story of Wild Strawberries is a simple one: Borg, a renowned professor and once a lauded physician, is about to receive an honorary degree. On the morning of the event, much to the chagrin of his longtime housekeeper/nanny (Jullan Kindahl), Borg decides that he is going to drive his old Packard to the event instead of flying to meet his son. The journey is more than just a road trip for the professor, but a metaphysical trek through his past as he questions what led him to this moment. When we first meet Isak, he is writing at his desk, his faithful dog lying at his feet, contemplating how evaluating behavior forced him to withdraw into old age and loneliness and turned him into a man who preferred the love of science to that of human interaction. This semi-solitary life has begun to take its toll on Isak, as his dreams have become odder and more frightening (and evidence of Bergman's own love of German Expressionism).For the viewer, Isak seems a nice enough fellow, which is why it's a bit of surprise when the trip begins and he's joined by his daughter-in-law Marianne (Ingrid Thulin) who

honestly tells him that she and her son (as well as others) view him as selfish and ruthless, hidden behind his charm and manners. Professor Borg seems particularly surprised, since he's been praised so much throughout his life, be it from a gas station attendant in a town where he used to practice medicine (Max von Sydow) who named a son after him) or from a trio of young hitchhikers who join the journey. The most interesting of the youths is Sara (Bibi Andersson) who also plays another Sara in flashbacks, a long lost love that Isak lot to his brother many years before. As the car winds closer to the ceremony, Borg's inner journey does as well as he comes to realize that for all his scientific training, the only thing he can't analyze is himself. "The day's clear reality dissolves into even clearer remnants of memory," he says at one point.

honestly tells him that she and her son (as well as others) view him as selfish and ruthless, hidden behind his charm and manners. Professor Borg seems particularly surprised, since he's been praised so much throughout his life, be it from a gas station attendant in a town where he used to practice medicine (Max von Sydow) who named a son after him) or from a trio of young hitchhikers who join the journey. The most interesting of the youths is Sara (Bibi Andersson) who also plays another Sara in flashbacks, a long lost love that Isak lot to his brother many years before. As the car winds closer to the ceremony, Borg's inner journey does as well as he comes to realize that for all his scientific training, the only thing he can't analyze is himself. "The day's clear reality dissolves into even clearer remnants of memory," he says at one point.The fact is that he feels as if he's a walking corpse and he wishes he could get that spark back, the spark he sees in the hitchhikers. I'd be remiss if I didn't praise the gorgeous black-and-white cinematography of Gunnar Fischer, who makes stunning use of light and shadows. Wild Strawberries represents Bergman when he was really growing into his powers as a filmmaker and while it may concern a 78-year-old man examining his life, the subject is as timeless for people of any age as the film itself is.

Tweet

Labels: 50s, Foreign, HBO, Ingmar Bergman, Movie Tributes, Ray Top 100, Von Sydow

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Your word isn't what counts, it's who you give it to

By Edward Copeland

You know a film is powerful when it's controversial when it opens and when a restored version is planned for re-release 25 years later, an MPAA ratings dispute over its violent images delays the re-release until it was 26 years old. Now 40 years old, Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch not only retains its power, the film grows in magnificence. If re-watching it evokes anything negative, it's the sadness that great films such as this hardly ever get re-releases anymore, affording movie fans the chance to see movies made before their time in a theater. As theaters move toward digital, it's probably sadly passed. Still, DVD and a good home setup keep The Wild Bunch vibrantly alive, if not ideally viewed.

You can't begin any conversation about The Wild Bunch (or Sam Peckinpah) without inevitably hitting the topic of violence and whether or not the film glorifies it or not but watching it again, it's beyond me how

anyone can see it that way. In fact, this time it seemed to me that Peckinpah builds the violence in the film to the crescendo of its finale. There is some use of slow-motion in the film's earlier gunbattles, the killings are quicker, more typical of what audiences are used to seeing in normal Westerns, without lingering on the wounds or carnage. Each subsequent encounter ups the ante leading to the famous finale, where the bloodshed contains the most meaning because the fight has the most meaning. When the bunch goes out in their blaze of glory, they aren't involved in a theft or running from a heist or a quick act of revenge, they are doing it because morally it's the correct thing for them to do, no matter that it is a suicide mission. That final melee is where you see the agony, the anguish and the pain. It's the way Peckinpah has set it up and the way it had to go because it needs to unfold this way for the characters to become flesh-and-blood people the audience cares about instead of just outlaws of a dying breed trying to hang on to a dying lifestyle in a fast-changing era.

anyone can see it that way. In fact, this time it seemed to me that Peckinpah builds the violence in the film to the crescendo of its finale. There is some use of slow-motion in the film's earlier gunbattles, the killings are quicker, more typical of what audiences are used to seeing in normal Westerns, without lingering on the wounds or carnage. Each subsequent encounter ups the ante leading to the famous finale, where the bloodshed contains the most meaning because the fight has the most meaning. When the bunch goes out in their blaze of glory, they aren't involved in a theft or running from a heist or a quick act of revenge, they are doing it because morally it's the correct thing for them to do, no matter that it is a suicide mission. That final melee is where you see the agony, the anguish and the pain. It's the way Peckinpah has set it up and the way it had to go because it needs to unfold this way for the characters to become flesh-and-blood people the audience cares about instead of just outlaws of a dying breed trying to hang on to a dying lifestyle in a fast-changing era.As The Wild Bunch opens, the viewer can't really be certain what time period they are in. The military uniforms that the bunch are wearing seem to

be early 20th century Army issue, but everything else seems to be from any Old West time period. It isn't until nearly an hour into the film when the would-be Mexican despot arrives in a fancy automobile and the bunch reacts with amazement and speak of reports of vehicles like birds that might be used in the next war that you realize we are several years into the 20th century and the Western lifestyle the bunch has enjoyed is passing the aging men by. Pike Bishop (William Holden), the group's leader admits that they aren't getting any younger and it's time they start "thinking beyond their guns." The impetus for this reappraisal of their lifework comes after the gang's latest assault on their favorite archenemy, the railroad. Peckinpah's opening setpiece really gets the movie galloping as we are introduced to the ruthlessness of the gang, taking the railroad's office as well as the equal ruthlessness of the railroad, who have staged a setup involving a team of bounty hunters in place to take out the bunch once and for all. There is no easy route taken of making the violent gang likable protagonists from the beginning. They are willing to leave an accomplice behind to almost certain death and kill another one with emotionless efficiency. This is their job and fun times come later. The fly in the ointment turns out to be the unexpected temperance union parade by a local church. When the siege is over, there are far more dead civilians than there are crooks or bounty

be early 20th century Army issue, but everything else seems to be from any Old West time period. It isn't until nearly an hour into the film when the would-be Mexican despot arrives in a fancy automobile and the bunch reacts with amazement and speak of reports of vehicles like birds that might be used in the next war that you realize we are several years into the 20th century and the Western lifestyle the bunch has enjoyed is passing the aging men by. Pike Bishop (William Holden), the group's leader admits that they aren't getting any younger and it's time they start "thinking beyond their guns." The impetus for this reappraisal of their lifework comes after the gang's latest assault on their favorite archenemy, the railroad. Peckinpah's opening setpiece really gets the movie galloping as we are introduced to the ruthlessness of the gang, taking the railroad's office as well as the equal ruthlessness of the railroad, who have staged a setup involving a team of bounty hunters in place to take out the bunch once and for all. There is no easy route taken of making the violent gang likable protagonists from the beginning. They are willing to leave an accomplice behind to almost certain death and kill another one with emotionless efficiency. This is their job and fun times come later. The fly in the ointment turns out to be the unexpected temperance union parade by a local church. When the siege is over, there are far more dead civilians than there are crooks or bounty hunters and the clergyman (Dub Taylor) lets the railroadman know it, but he's indifferent as big businessmen continue to be to this day as his interests and bottom line supersede the public's. This "do it on the cheap" mentality extends to the bounty hunters that the railroad hires. The leaders is a former member of the bunch, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), who has been promised an end to his prison sentence if he brings them back dead. Unfortunately, as help he's been given a motley group of misfits led by Strother Martin, who aren't above pillaging the corpses of the accidentally slain. Martin proves to be comic relief extraordinaire, especially with his large crucifix hanging around his neck. Ryan's performance as Thornton, the bounty hunter whose heart lies with his prey, grows deeper and better with each viewing.

hunters and the clergyman (Dub Taylor) lets the railroadman know it, but he's indifferent as big businessmen continue to be to this day as his interests and bottom line supersede the public's. This "do it on the cheap" mentality extends to the bounty hunters that the railroad hires. The leaders is a former member of the bunch, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), who has been promised an end to his prison sentence if he brings them back dead. Unfortunately, as help he's been given a motley group of misfits led by Strother Martin, who aren't above pillaging the corpses of the accidentally slain. Martin proves to be comic relief extraordinaire, especially with his large crucifix hanging around his neck. Ryan's performance as Thornton, the bounty hunter whose heart lies with his prey, grows deeper and better with each viewing. The actors who comprise the bunch are a strong ensemble. Three had won Oscars by the time The Wild

Bunch was made and a fourth would win one two years later. In nearly every case, it's one of the actors' strongest performances and, in one case, I consider it his best. Holden is great as Pike and of course the list of great roles he played are legendary spanning from Sunset Blvd. to Network and many in between. Pike Bishop belongs in that hallowed company as Holden gives him a taciturn strength but isn't afraid to show his vulnerabilities and the toll time has taken on the robber. Often forgotten, since he's not as active in the gang's criminal exploits, is the great Edmond O'Brien as Sykes, who used to ride and kill with the best of them but now basically holds down the fort while the bunch is away. O'Brien is a riot, even if at times he borders on cliche and seems to be channelling Walter Huston in Treasure of the Sierra Madre. More comedy is provided by Warren Oates and

Bunch was made and a fourth would win one two years later. In nearly every case, it's one of the actors' strongest performances and, in one case, I consider it his best. Holden is great as Pike and of course the list of great roles he played are legendary spanning from Sunset Blvd. to Network and many in between. Pike Bishop belongs in that hallowed company as Holden gives him a taciturn strength but isn't afraid to show his vulnerabilities and the toll time has taken on the robber. Often forgotten, since he's not as active in the gang's criminal exploits, is the great Edmond O'Brien as Sykes, who used to ride and kill with the best of them but now basically holds down the fort while the bunch is away. O'Brien is a riot, even if at times he borders on cliche and seems to be channelling Walter Huston in Treasure of the Sierra Madre. More comedy is provided by Warren Oates and Ben Johnson as the drinkin', whorin' Gorch brothers. (In the DVD commentary, one of the Peckinpah experts mentions that Johnson's wife never let him return to the sites of their Mexican scenes because of the scenes of his character's lechery depicted there. TV's Buffy the Vampire Slayer even saluted Oates' character with a vampire bounty hunter with cowboy sensibility named Lyle Gorch on a couple of episodes. The youngest and newest member of the gang, the one who gets them in trouble and helps them find their moral compass, is Angel (Jaime Sanchez), a Mexican who wants to help his people get out from under the thumb of the minidictators who ruled Mexico at the time. Politics is anathema to the others but when they witness the mistreatment that goes on of the poor, eventually even the aging crooks discover there are some fights worth joining. Of course, the

Ben Johnson as the drinkin', whorin' Gorch brothers. (In the DVD commentary, one of the Peckinpah experts mentions that Johnson's wife never let him return to the sites of their Mexican scenes because of the scenes of his character's lechery depicted there. TV's Buffy the Vampire Slayer even saluted Oates' character with a vampire bounty hunter with cowboy sensibility named Lyle Gorch on a couple of episodes. The youngest and newest member of the gang, the one who gets them in trouble and helps them find their moral compass, is Angel (Jaime Sanchez), a Mexican who wants to help his people get out from under the thumb of the minidictators who ruled Mexico at the time. Politics is anathema to the others but when they witness the mistreatment that goes on of the poor, eventually even the aging crooks discover there are some fights worth joining. Of course, the second most important member of the bunch is Dutch (Ernest Borgnine). Though Borgnine has given many good performances, including his Oscar-winning one in Marty, it's clear to me after watching The Wild Bunch again that this is easily his greatest performance. He's always the one who seems to have the smartest take, the most regrets, and Dutch gets the others to realize their obligations when the final battle comes about. The grin that Borgnine lets loose before the gunfire is a sight to behold as are his quieter moments, turning his back when he's afraid to admit something tender to Pike or he's just sitting on a stoop whittling waiting for the others to finish their debauchery.

second most important member of the bunch is Dutch (Ernest Borgnine). Though Borgnine has given many good performances, including his Oscar-winning one in Marty, it's clear to me after watching The Wild Bunch again that this is easily his greatest performance. He's always the one who seems to have the smartest take, the most regrets, and Dutch gets the others to realize their obligations when the final battle comes about. The grin that Borgnine lets loose before the gunfire is a sight to behold as are his quieter moments, turning his back when he's afraid to admit something tender to Pike or he's just sitting on a stoop whittling waiting for the others to finish their debauchery.As all conversations about The Wild Bunch inevitably focus on the violence, I think we should end this anniversary discussing those aspects that are too often overlooked. In addition to the performances, not

enough is made of the comic relief (the last images of the bunch are of them laughing at better times) as when the Mexican generale lets a machine gun go wild despite his German visitor's plea that he must place it upon a tripod. There's also the imagery. The kids torturing the scorpions gets cited often, but there also are nice touches such as a shot of a mother breastfeeding her baby while a belt of ammunition hangs across her torso. Finally, there is the suspense. Like all great suspense scenes, no matter how many times you see them, you still wonder what will happen, as when that wagon gets stuck on the bridge that's already set to detonate. I'd also be remiss if I didn't shower some praise on some of the film's other collaborators such as Peckinpah's co-writer Walon Green, the vivid photography of Lucien Ballard, the fine score by Jerry Fielding and the absolutely irreplaceable editing of Lou Lombardo.

enough is made of the comic relief (the last images of the bunch are of them laughing at better times) as when the Mexican generale lets a machine gun go wild despite his German visitor's plea that he must place it upon a tripod. There's also the imagery. The kids torturing the scorpions gets cited often, but there also are nice touches such as a shot of a mother breastfeeding her baby while a belt of ammunition hangs across her torso. Finally, there is the suspense. Like all great suspense scenes, no matter how many times you see them, you still wonder what will happen, as when that wagon gets stuck on the bridge that's already set to detonate. I'd also be remiss if I didn't shower some praise on some of the film's other collaborators such as Peckinpah's co-writer Walon Green, the vivid photography of Lucien Ballard, the fine score by Jerry Fielding and the absolutely irreplaceable editing of Lou Lombardo.

Tweet

Labels: 60s, B. Johnson, Borgnine, Dub Taylor, Holden, Movie Tributes, Oates, Peckinpah, Robert Ryan, W. Huston

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, June 15, 2009

“There’s no reason to shoot at me! I’m a dentist!”

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.“Comedy is subjective,” goes the old saw — and what this basically says in a nutshell that something humorous enough to make soda pop come out of my nose might very well leave you stone-faced in the bargain. Take me and my sister Kat … I consider myself a connoisseur of film comedy, enjoying the antics of Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, Laurel & Hardy, the Marx Brothers, Fields and practically everyone else from the golden age of mirthmaking. Kat will have none of that, preferring the modern-day antics of comic actors like Will Ferrell or Steve Carell — both of whom leave me completely pokerfaced.

On this date 30 years ago, a feature film was released by Warner Bros. that provides the exception to my and my sibling’s “rules of comedy” — in fact, to this day I’ve yet to come across any individual who has something bad to say about it. That movie is The In-Laws (1979), an early example of the “buddy” film starring Alan Arkin as a mild-mannered Manhattan dentist who, upon meeting prospective in-law Peter Falk (who claims to work for the CIA), finds his world completely turned topsy-turvy when he’s helplessly enmeshed in Falk’s outlandish scheme to rob the U.S. Treasury while in the service of a Latin American dictator (Richard Libertini) with a Senor Wences fetish.

Dr. Sheldon Kornpett (Arkin) invites the parents (Falk, Arlene Golonka) of his soon-to-be son-in-law (Michael Lembeck) over for an introductory party days before the wedding, and when “businessman” Vince Ricardo regales his audience with peculiar tales of his days in Guatemala (“They have tsetse flies down there the size of eagles,” he claims), Sheldon is suspicious that Vince may be a few sandwiches shy of a picnic (he tells his wife played by Nancy Dussault that he would have read about the giant flies in National Geographic). When Vince stops by Sheldon’s practice and asks him for a favor (removing the contents from a safe in a nearby office) the dentist good-naturedly agrees to help him out…and finds himself on the receiving end of assassin’s bullets and a series of incredible adventures that lead to a hysterical climax in which he and Vince face a dictator’s firing squad (“We have no blindfolds, Senor — we are a poor country!”).

The first element in The In-Laws that is ultimately responsible for its incredible comedy payoff is the falling-down funny script by writer Andrew Bergman (one of several scribes who worked on the classic screenplay of Blazing Saddles), who was asked by the Warners studio to create a film in the same vein as an earlier Alan Arkin film (one in which he co-starred with James Caan as a pair of unconventional cops), Freebie and the Bean (1974). It soon became obvious that Bergman’s concept for the new film didn’t completely jibe with Warners’ original Freebie follow-up idea but Bergman delivered such a masterpiece of understated comedy that it really made no difference. The In-Laws’ script is that rare piece of material that triumphs over the other flaws in the film (the lackluster direction by Arthur Hiller, for starters), frequently coming across as improvised and off-the-cuff.

Part of that off-the-cuff improvisation can be attributed to the participation of Alan Arkin (one of the original members of Chicago’s Second City troupe), one of the cinema’s finest character actors and an individual with an amazing performing range that includes comedic roles (The Russians are Coming, the Russians are Coming, Little Murders) and dramatic turns (Wait Until Dark, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter) as well. But his co-star Falk is no slouch in the funny bone department, either; though known to audiences primarily as the eccentric TV detective Columbo, Peter also demonstrated a fine pair of comedic chops in films such as Murder by Death and The Cheap Detective. Watching both these actors play off one another is a thing of beauty, with Arkin’s sardonic Sheldon the perfect foil to the slightly egomaniacal Vince (“I’m such a great driver…it’s incomprehensible that they took my license away”).

Everyone who’s watched The In-Laws at least one time has a favorite bit or scene: some of the highlights include Falk’s instructions to Arkin on how to avoid being shot at (“Serpentine, Shel, serpentine!”) — which is made all the funnier when Arkin’s character runs back to his original starting point and then takes Falk’s advice as if he were going for a second take; Arkin’s hysteria at discovering someone has done irreversible customizing on his vehicle (“I have flames on my car!”); and the bit in the chartered airplane where flight attendant James Hong gives Arkin the customary pre-flight instructions…entirely in Chinese. As for myself, I still get a hearty chuckle when Arkin announces he was down in the hotel lobby looking for Mexican porn (“El Hustlero”) and sister Kat and I have been known to make ourselves sick with laughter when we reconstruct the scene where Falk, at the wheel of the car, is describing a delicious Mexican dish (“They serve it with a large orange juice…grande”) and then interrupts himself with “Oh, Jesus…PIGS!” as he’s forced to stomp the brakes to avoid a procession of swine crossing the road.

Writer Andrew Bergman tried to collect lightning in a bottle a second time when he wrote the screenplay (as Warren Bogle) for Big Trouble (1985), a comedy that re-teamed Arkin and Falk in what would turn out to be a disappointing reunion (even the fact that the movie had a better director in Falk’s old compadre John Cassavetes couldn’t save it). He would, however, bring his quirky writing style to two successful comedies that followed in the wake of In-Laws’ success: The Freshman (1990) and Honeymoon in Vegas (1992). Bergman also received screen credit in the 2003 remake of In-Laws, a loose adaptation from the bigger-is-funnier school of comedy (have we learned nothing from 1941?) that recast Albert Brooks and Michael Douglas in the Arkin and Falk roles and served as little less than a reminder how much better the first film was and that, 30 years since it was introduced to the big screen, it still manages to find appreciative audiences…particularly those who are watching it for the very first time.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Albert Brooks, Caan, Cassavetes, Chaplin, Falk, Fields, Keaton, M. Douglas, Marx Brothers, Movie Tributes

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, June 09, 2009

Taken not stirred

By Edward Copeland

For some reason in the past few years, comedies keep getting longer. Most of the best ones are usually never much longer than 90 minutes, but they've been stretching that clock. So I was surprised when I rented the thriller Taken, figuring it would be closer to the usual 2 hour or 2 hour plus range, to see that it only came in at an hour and a half. I hoped that perhaps this foretold a taut tale to come but while the film unspooled quickly, not much of an impression was left behind.

Liam Neeson is fine as a former CIA agent whose experience in the agency has made him a bit of an overprotective father, especially after a bitter divorce. When he reluctantly agrees to allow his daughter and her friend to go on a trip to Paris, he happens to overhear their abduction and soon he's back into superagent mode to get his daughter back.

Some of the action scenes composed by director Pierre Morel are nice, but they all seem to run together and Neeson seems to put together what's happened to his daughter far too easily. Wouldn't he ever stumble upon a false lead or go down a road that leads nowhere? I guess that's a little hard to cover in 90 minutes.

In its own none-too-subtle way, Taken also seems to be made by a P.R. firm working for Dick Cheney, showing the efficacy of getting accurate information out of torture. Now, I'd be lying if I didn't admit that there is part of me (and probably part of a lot more people than would like to admit it too) that enjoys the vicarious thrill of beating the shit out of people who have harmed your loved ones, but that alone does not a movie make.

It also seems so determined to get to its final destination that some essentials get lost in the shuffle (Don't blink or you'll miss the fate of Neeson's daughter's traveling companion, not that anyone seems too worried about her).

By the time they get to the inevitable ending, I almost expected one of those fake freeze frame laugh endings they used to have at the end of Police Squad.

There's a reason films such as Taken get released early in a new year where they'll soon be forgotten.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Liam Neeson

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, June 01, 2009

2008-2009 Broadway Plays, Part 1

By Josh R

May is not a time of year that holds pleasant associations for anyone who’s ever survived a college education. Cramming for exams, grinding out term papers, fighting off the urge to procrastinate…to say that it can be overwhelming is the height of understatement (I would describe my mood at the tail end of my final semester as falling somewhere between immoderately frazzled and thoroughly deranged). It was never my intention to revisit this dreaded state of emotional dystopia, and yet, with a whole season’s worth of plays to discuss, and the Tony Awards looming on the not-too-distant horizon, I find myself in more or less the same spot as when I had to pull 30-odd pages on Dalton Trumbo and The Blacklist out of thin air in about 48 hours in order to graduate. The best approach — really, the only realistic approach at this point — is address everything as briefly as possible, with apologies to the shows I omit due to considerations of time, space and exhaustion.

The straight play reigned supreme on Broadway this year, with more than 20 revivals and a smattering of new works. Theatres that have traditionally housed musicals played host to tried-and-true favorites by Coward and O’Neill, as producers tried to adjust to a less friendly economy. Musicals cost money; with smaller casts and lower overheads, plays are here to stay — at least for the immediate future.

First up — the early-season entries that premiered in the fall, as well as the current crop of “new” plays (note the use of quotation marks) in contention for Tony Awards.

The most surprising production of the 2009-2010 season may well have been Ian Rickson’s glorious staging of The Seagull, in a production that transferred from London. Chekhov can be a rather dry affair, and The Seagull, while indisputably a classic, can seem pretty parched in the absence of a fresh directorial perspective. This was very much the case with the last Seagull I’d seen — a star-studded debacle in Central Park helmed by Mike Nichols featuring Meryl Streep, Kevin Kline, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Natalie Portman and a phalanx of other big-name talents. The fact that Nichols

seemed more interested in throwing an A-list party than in interpreting the text was the least of that show’s problems — everyone seemed to be acting in a different play (and frankly, all but a few seemed mismatched with their roles). This was most assuredly not the case in Rickson’s masterful staging, which, while remaining entirely true to the spirit of the piece and the intentions of its author, didn’t treat the play like the kind of lofty classical opus to be treated with kid gloves and kept under glass like a priceless museum artifact. In much the same manner as Louis Malle’s Vanya on 42nd Street, this was The Seagull brought down to earth and demythologized — a naturalistic staging which captured the emotional truth behind the words without getting wrapped up in the profundity of them, or aiming for the formal gloss of a Masterpiece Theatre production. With his complex portrayal of a woman who can be both passionate and aloof, engaging and off-putting, breathtakingly assured and wildly insecure, Chekhov seemed to have imagined the actress Arkadina as a Molotov cocktail blended from equal parts fire and ice — and that’s exactly the way Kristin Scott Thomas played her, embodying the myriad contradictions of the character with wit, verve, and a laser-like emotional acuity. Since the production ended its limited engagement way back in December — and since Tony nominators have notoriously short memories — The Seagull and its star were conspicuously absent from the list of contenders for the big prizes.

seemed more interested in throwing an A-list party than in interpreting the text was the least of that show’s problems — everyone seemed to be acting in a different play (and frankly, all but a few seemed mismatched with their roles). This was most assuredly not the case in Rickson’s masterful staging, which, while remaining entirely true to the spirit of the piece and the intentions of its author, didn’t treat the play like the kind of lofty classical opus to be treated with kid gloves and kept under glass like a priceless museum artifact. In much the same manner as Louis Malle’s Vanya on 42nd Street, this was The Seagull brought down to earth and demythologized — a naturalistic staging which captured the emotional truth behind the words without getting wrapped up in the profundity of them, or aiming for the formal gloss of a Masterpiece Theatre production. With his complex portrayal of a woman who can be both passionate and aloof, engaging and off-putting, breathtakingly assured and wildly insecure, Chekhov seemed to have imagined the actress Arkadina as a Molotov cocktail blended from equal parts fire and ice — and that’s exactly the way Kristin Scott Thomas played her, embodying the myriad contradictions of the character with wit, verve, and a laser-like emotional acuity. Since the production ended its limited engagement way back in December — and since Tony nominators have notoriously short memories — The Seagull and its star were conspicuously absent from the list of contenders for the big prizes.Also lost in the shuffle was Thea Sharrock’s hugely successful revival of Peter Shaffer’s Equus — although whether that success owed itself more to

the merits of the production than to Daniel Radcliffe’s highly publicized nude scene can remain a subject of debate (or not — something tells me all those teenage girls in attendance the day that I saw it were not hardcore Shaffer mavens). No matter how many times I see it, I’m never quite sure what to think of Equus as a play; while frequently fascinating and unfailingly provocative, it never quite seems to come together in the way that it should. Its central conflict is built around the contention that true liberation can be achieved only through madness — a conceit that the narrative doesn’t really seem to support, given that the lunatic in question seems less a free spirit than a desperately unhappy prisoner of his own warped mind. That notwithstanding, Sharrock’s highly polished staging kept the action moving even though the play’s overly cerebral passages, and Richard Griffiths delivered a performance admirable for its understatement (resisting the urge to mine so many flashy monologues for the stuff of actorly tour-de-force is no small thing). Inevitably, it was Radcliffe — in clothes and out of them — who attracted the lion’s share of the attention, although the performance lacked something in terms of shading and nuance. I’m not averse to an element of theatricality — but portraying a character who functions in a state of angry delirium doesn't necessitate shouting all of one’s lines.

the merits of the production than to Daniel Radcliffe’s highly publicized nude scene can remain a subject of debate (or not — something tells me all those teenage girls in attendance the day that I saw it were not hardcore Shaffer mavens). No matter how many times I see it, I’m never quite sure what to think of Equus as a play; while frequently fascinating and unfailingly provocative, it never quite seems to come together in the way that it should. Its central conflict is built around the contention that true liberation can be achieved only through madness — a conceit that the narrative doesn’t really seem to support, given that the lunatic in question seems less a free spirit than a desperately unhappy prisoner of his own warped mind. That notwithstanding, Sharrock’s highly polished staging kept the action moving even though the play’s overly cerebral passages, and Richard Griffiths delivered a performance admirable for its understatement (resisting the urge to mine so many flashy monologues for the stuff of actorly tour-de-force is no small thing). Inevitably, it was Radcliffe — in clothes and out of them — who attracted the lion’s share of the attention, although the performance lacked something in terms of shading and nuance. I’m not averse to an element of theatricality — but portraying a character who functions in a state of angry delirium doesn't necessitate shouting all of one’s lines.The shouting was appropriate in Neil Pepe’s fall revival of David Mamet’s Speed-the-Plow, a marvelously cynical look at Hollywood power players and the ambitious hangers-on who love them (or, at least, want to ride to glory on their coattails). As a play, Speed-the-Plow isn’t quite as rich in scope as some of Mamet’s more celebrated works — nevertheless, it is a smartly calibrated, vastly entertaining example of the playwright’s craft. The action is streamlined and concise, while the dialogue, consisting mainly of sentence fragments, manages to be blunt yet elliptical at the same time. In some of his plays — particularly, it must be said, in the ones where female characters are placed front and center — Mamet’s fragmented style seems to be at odds with characterization. It feels perfectly right in Speed-the-Plow, which centers around the interactions of two jittery, over-caffeinated studio execs whose motors run so fast they can only pause long enough to communicate in sound bites. When I saw the production, these two titans of industry were played by Jeremy Piven and Raul Esparza, while the role of the seemingly demure office temp who gets caught in the crossfire was performed by Elisabeth Moss. Piven left the production mid-run amidst some controversy — something about mercury poisoning after having eaten too much salmon — and was subsequently replaced by Norbert Leo Butz and Mamet stalwart William H. Macy. Better Piven had departed under fishy circumstances than Mr. Esparza, who, I suppose, may be capable of giving a performance that is less than brilliant — I only say “may” because his most recent performances haven’t provided any evidence to that effect. On the heels of his triumphs in Company and The Homecoming, the protean star of plays and musicals delivered yet another galvanizing star turn — one which went for the jugular, and hit its target like a guided missile.

As for new plays, the story remained much as it always has on Broadway — which is to say, ‘twas slim pickins. The season’s best and most interesting new works could be found in non-for-profit off-Broadway houses — venues where the risk factor is considerably less from a financial standpoint, and greater risks can be taken on the artistic front as a result. Female playwrights made a particularly strong showing this year. Lynn Nottage’s Ruined, a modern-day version of Mother Courage set in war-torn Congo, deservedly won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, while Gina Gionfriddo’s Becky Shaw was a sharply observed comedy of manners with a sleek contemporary twist. Sarah Kane’s Blasted — an audacious compendium of unspeakable behaviors — was perversely fascinating, while Annie Baker’s clever, inquisitive Body Awareness marked a particularly auspicious debut for an emerging playwright. If the women commanded the spotlight, the men were not entirely lacking in action; Lorenzo Pisoni’s Humor Abuse, an autobiographical account of growing up in the circus, and Chris Durang’s absurdist trifle Why Torture is Wrong and The People who Love Them were particular standouts in a off-Broadway season that offered more than its share of high points (the lows were there too…but that’s a discussion for another day).

To say that no new works to be seen on Broadway quite matched that standard is a bit misleading, since all but a few could be accurately termed “new.” The late Horton Foote’s Dividing the Estate, written and first performed in the late 1980s, made its belated Broadway bow in a limited engagement at The Booth Theatre last fall. A kindler, gentler cousin to August: Osage County, featuring a gaggle of contentious Texan siblings squabbling over their inheritance, it was warmly received by critics — if generating little in the way of excitement beyond that. Foote’s homespun, elegiac style can work to beguiling effect when plied in service of gentle stories about gentle subjects — Trip to Bountiful and Tender Mercies are the two that immediately spring to mind. It doesn’t seem entirely appropriate, though, when the subject is something as thorny as a family feud. As with many of Foote’s later works, Dividing the Estate seemed to consist mainly of rose-tinged anecdotes strung together to create a sort of careworn, dog-eared scrapbook — while the fire-and-brimstone antics of Osage County would have seemed completely out-of-place, the proceedings could have used a bit more in the way of tension and urgency. Still, the play did furnish the occasion for pitch-perfect ensemble work by cast led by Elizabeth Ashley and Gerald McRaney; deserving of special praise (and receiving the show’s lone acting nomination) was Hallie Foote, the playwright’s daughter and frequent collaborator, making a memorable impression as the passive-aggressive sister determined to grab off the biggest piece of the pie. Another “new” play — at least according to Tony eligibility rulings — was Richard Greenberg’s The American Plan, originally performed off-Broadway in the early '90s. The Manhattan Theatre Club revival, directed by David Grindley, featured expert performances by Lily Rabe, Keiran Campion and particularly the acerbic, husky-voiced Mercedes Ruehl as an imposing, fatalistic Teutonic mama who alternately coddles and smothers her hapless offspring. Fine acting aside, you could see The American Plan’s surprise twist coming from a mile away, and the pretensions of the dialogue weighed the proceedings down to a certain degree — it didn’t quite make sense for Jews on vacation in The Catskills to spend quite as much time waxing philosophical.

Something called Impressionism quickly established itself as the biggest belly-flop of the year — not even the marquee value of Jeremy Irons and Joan Allen, making their first Broadway appearances since The Real Thing and The Heidi Chronicles respectively, could keep it from closing two months ahead of schedule. Not all the news was bad, however, and other instances of starry casting paid big dividends. There was no reason to assume that Jane Fonda, who hadn’t set foot on a Broadway stage in some 40-odd years, would deliver one of the breakout performances of the season. She did just that in 33 Variations, a strange, diffuse work by I Am My Own Wife scribe Moises Kaufman, rising above the limitations of the script and showing that she’s still got the goods to take on multi-faceted roles of the non-monster-in-law variety. Fonda’s most exciting quality as a performer has always been her bracing, prickly intelligence — the performances that stand as her career high-water marks always examined the manner in which intellect can exist at odds with naked emotionalism. It’s a formula that still retains its potency; as a dying scholar trying to unravel the mysteries of Beethoven’s life and work, she was never less than compelling, even when the play itself seemed unfocused and inconsistent in its ambitions. A cutesy subplot involving a burgeoning romance between Colin Hanks and Samantha Mathis — appealing performers who work a bit too hard to be ingratiating — could have excised altogether without altering the narrative framework considerably.

If 33 Variations was, at least, a work of considerable ambition, the season’s one true non-musical smash was blissfully unencumbered by anything of the kind. I didn’t see Art, Yasmina Reza’s previous Broadway hit, or Life x 3, which did very well abroad but was less kindly received in its 2004 New York debut. Based on everything I’ve gleaned about the prolific French playwright and her oeuvre, God of Carnage doesn’t represent much of a departure for her. It’s simplistic in its aims, which is to say it has about as much depth to it as pan of water; if that statement smacks of reproach, bear in mind that, in certain instances, shallowness can be a virtue. Reza has a remarkably assured grasp of the mechanics of playwriting — one can’t fault her sense of structure, and God of Carnage is, above all things, a shrewdly constructed work of theater. It knows exactly where it’s going and exactly how to get there, moving along smoothly from start to finish without hitting any speed bumps or permitting itself to stall for a fraction of a second. If it is, essentially, a glorified sitcom given the illusion of sophistication by virtue of an upscale milieu and highbrow cultural references (a pigeon dressed up as a peacock), that doesn’t prevent it from qualifying as the most entertaining new work of the season. Two couples meet to discuss an altercation their children have had on the school playground — what begins as an informal meeting for dessert and cocktails, largely characterized by strained civility and forced politeness, quickly degenerates into a drunken, screaming free-for-all, with the type of juvenile antics that might embarrass Albee’s George and Martha (in case you were wondering, it is a comedy). It’s a foolproof recipe for success — everyone loves seeing grown-up people behaving like children, especially when those cell-phone-stealing, flower-throwing, projectile-vomiting heathens in Armani are played by actors as resourceful as the four person cast assembled by director Matthew Warchus. His rollicking, immaculately executed production gives each performer his or her moment to shine in turn — James Gandolfini and Jeff Daniels are perfectly matched as wildly contrasting combatants in what turns out to be the silliest of pissing contests, Hope Davis’ drippy passivity mutates into a kind of maniacal glee all the more hysterical for its unexpectedness, while the indispensable Marcia Gay Harden all but steals the show as the kind of self-important, highly strung culture vulture who couldn’t let any imagined slight pass if her life — or her sanity — depended upon it. You can insult her husband, but don’t dare to insult her taste.