Thursday, November 30, 2006

Don't ask about Don't Tell

By Edward Copeland

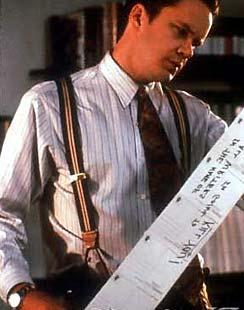

As I mentioned yesterday, I'd recently watched Don't Tell, Italy's Oscar-nominated submission last year for foreign language film, meaning the only one of the five nominees I haven't seen yet is France's Joyeux Noel. Of the four I've seen though, Don't Tell definitely ranks fourth.

This completely unfocused drama would seem to focus on adults dealing with sexual abuse by their father when they were young, but there also are digressive story strands such as a blind lesbian, a middle-age woman whose husband leaves her for a younger woman and the filming of a movie, not to mention surprise pregnancies and cheating lovers.

It's not that all this plot is confusing, it's just not that interesting, despite an acceptable lead performance by Giovanna Mezzogiorno as Sabina, the struggling young actress who recovers memories of her past abuse, and Angela Finocchiaro as her director who faces life alone when her husband splits.

To me, the most interesting question raised by Don't Tell is how many Europeans make their livings dubbing films and television shows, as Sabina does here in the opening scene. It seems as if I've seen a helluva lot of European films over the years that contain scenes and characters in a dubbing room (How many of those has Pedro Almodóvar produced alone?).

In Don't Tell, Sabina points out the metaphor late in the film so that you can't miss it that perhaps everyone has two voices, just like the characters she dubs. Unfortunately, Don't Tell has too many voices and none of them are interesting enough to hold your interest.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Almodóvar, Foreign

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

German film needed fleshing out

By Edward Copeland

I've now seen four of the five nominees for the 2005 Academy Award for foreign language film. I've written about Tsotsi previously and will write about Don't Tell soon. I also saw Paradise Now, but that predated this blog. So far, I think it's fair to say that by picking Tsotsi, the Academy made the right choice.

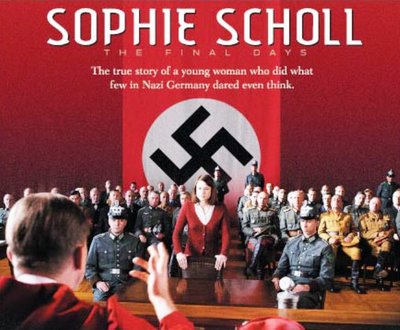

This isn't to say that Sophie Scholl: The Final Days isn't good — in fact it has lots of things to offer, principally a fine lead performance by Julia Jentsch as the title character and telling a World War II story that I was unfamiliar with. Sophie and her brother Hans (Fabian Hinrichs) were college students and members of The White Rose, an anti-Nazi movement in Germany during Hitler's reign. I'd never known about The White Rose prior to this film — I knew there were opponents to Hitler within Germany, but this group was new to me. In a way, it shows another example of how college activism can change things and questions why the U.S. outcry against the Iraqi debacle hasn't been more pronounced in universities as it was during Vietnam.

Director Marc Rothemund certainly keeps Sophie Scholl moving and if there is much of a flaw to the film it may be that it is too linear. The narrative follows a straight line from the opening incident that gets the Scholls in trouble to their ultimate punishment at the hands of the Nazis.

A better movie might have been made if there were more details about the formation of The White Rose and what led them to their actions: We all know Hitler was evil, but what clued these students in that other Germans missed?

Jentsch's performance and the Cliff's Notes version of an underreported historical chapter makes the movie worthwhile.

Tweet

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, November 27, 2006

The Wire No. 48: A New Day

BLOGGER'S NOTE: As always, know that spoilers lie below, so don't venture further unless you've seen the episode or don't care if you know what happens.

By Edward Copeland

A sense of optimism has washed over the Baltimore Police Department in the wake of Tommy Carcetti's victory as mayor, a sense that perhaps it's "a new day in Baltimore" where the days of juking the stats are over and officers can anticipate a return to real police work. This is The Wire — what are the odds that is really going to happen, do you think?

As newly minted Col. Cedric Daniels and his now-public significant other Assistant State's Attorney Rhonda Pearlman give a pep talk to the detectives about what changes lie ahead, the detectives beam with hope at a new day dawning. Daniels even asks Lester if he's willing to go back to the Major Crimes Unit, though Freamon hesitates, since Lt. Marimow still runs the squad. Daniels even dangles the chance for Lester to select his own boss. Still languishing at MCU and worrying about his missing camera problem, Herc faces more problems thanks to Bubs' tricking him into taking down a well-connected minister — and the ripple effects have reached Carcetti, who is torn between letting a true internal investigation occur or firing Herc to please the ministers and risk alienating the rank-and-file officers. The buck is passed down the line as Rawls, who finally has been clued into Daniels' golden boy status by Valchek, dumps the problem at Daniels' desk and urges him to "do the right thing." Daniels expresses surprise, since the right thing isn't usually recommended. "I know. It doesn't happen often," Rawls responds.

Burrell and state Sen. Davis still plot how to get Burrell into Carcetti's good graces and see an opportunity presenting itself thanks to Carcetti's Herc problem. "Am I the only one who knows how to play this game?" Burrell asks Clay while sinking a putt on a golf course. Soon, Burrell has shown up in Carcetti's office with a large book of department regulations, offering Carcetti other options for getting rid of his Herc problem with a lower risk of alienating constituents or city employees. "I know what a mayor needs," Burrell says. While Carcetti rushes around trying to get city workers to start solving various municipal problems, he's hit with an unwelcome surprise: The school district is running a $54 million deficit and with few good options for solving it, when advisers pooh-pooh the idea of using the city's Rainy Day Fund. "Feels like a rainy day to me," Carcetti comments. "Cloudy like a motherfucker," Norman adds.

For the students at Tilghman Middle School, most of the outlook is for storms as well. It starts optimistically enough with Namond, flush with cash from his corner gig, showing off by buying dinner for his friends. Though he's also facing other problems from the continued overbearance of his mom, who insists he cut his hair, and his disappointment at learning that Bunny's class is

being discontinued when he'd rather stay in there than be sent back to a normal classroom. He even faces a slight twinge of conscience when Michael's junkie mom comes to him on the street for a fix, which he reluctantly supplies. Namond and his friends also are outraged when they learn of what the sadistic Officer Walker did to Donut, so they make plans for revenge — a relatively nonviolent variety which ends up with Michael taking possession of the ring that must have passed through more Baltimore hands than any in its history having started with Old Face Andre, gone to Marlo, been taken by Omar and then purloined by Walker before Michael takes it for himself.

being discontinued when he'd rather stay in there than be sent back to a normal classroom. He even faces a slight twinge of conscience when Michael's junkie mom comes to him on the street for a fix, which he reluctantly supplies. Namond and his friends also are outraged when they learn of what the sadistic Officer Walker did to Donut, so they make plans for revenge — a relatively nonviolent variety which ends up with Michael taking possession of the ring that must have passed through more Baltimore hands than any in its history having started with Old Face Andre, gone to Marlo, been taken by Omar and then purloined by Walker before Michael takes it for himself.

The kids aren't the only ones contemplating revenge as Bubbles makes plans to concoct some tainted drugs to give to his tormenter — and welcomes the return of Sherrod as well. Back at school, Michael chooses to stand up for Randy at school when his snitch reputation leads to a beatdown — and the failure of his once-lucrative candy business. Randy also learns about the fate of Little Kevin and fears for his own life. Dukie gets what should be good news — he's being promoted to ninth grade, but the quiet teen seems reluctant at leaving his friends and his school for an uncertain place, though Prez reassures him he'd still help him if he needs his clothes washed or access to a shower. Prez isn't pleased when he sees what has happened to Randy, feeling he betrayed the boy by trusting Carver and Daniels before he and Carver realize that, once again, Herc has let someone down by not delivering the news about Randy's information about Lex's disappearance to Bunk, prompting Bunk to read Herc the riot act as Lester is getting settled back in at MCU. Omar, still trying to figure out who is working with whom and who set him up for the convenience store murder, learns that Slim Charles now works for Prop Joe and, suspecting that Joe set him up with the poker game now that he knows who Marlo is, takes it straight to Joe — demanding his help in taking down Marlo's stash and asking him to repair a clock for him at the same time.

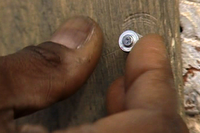

Meanwhile, a re-energized Lester and a determined Bunk return to the Lex hunt, searching the area near where he was told to go by Randy. Suddenly, Lester spots something out of the corner of his eye — the line of abandoned rowhouses. Upon further inspection, Lester's keen eye notices that the boards sealing the buildings sometimes contain different screws and recalls that when Herc pulled Chris and Snoop over, he mentioned a nail gun. At long last, Lester and Bunk have found Lex — and the whereabouts of many other victims of Marlo's reign whose bodies had seemed to have vanished.

Tweet

Labels: David Simon, HBO, The Wire, TV Recap

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, November 24, 2006

Betty Comden (1917-2006)

What a career. Betty Comden acted, wrote screenplays and, most importantly, was responsible for many memorable tunes with her late writing partner Adolph Green. The team's most lasting contribution to American popular entertainment will most certainly be their brilliant screenplay for Singin' in the Rain, for my money still the best movie musical that Hollywood ever produced.

The Comden and Green team didn't write most of the songs made famous by the film, but they did contribute the lyrics to "Moses Supposes." Comden and Green also wrote the script for one of the other great musicals — the first collaboration between co-directors Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, On the Town, adapted from the Broadway musical they wrote the lyrics and book for, including the classic "New York, New York." They also wrote The Band Wagon starring Fred Astaire, the script for the nonmusical Auntie Mame and the wacky and darkly comic Shirley MacLaine comedy What a Way to Go!

On Broadway, the Comden and Green team wrote the book and the music for On the Twentieth Century, Bells Are Ringing, the lyrics for Leonard Bernstein's Wonderful Town, the lyrics for Cy Coleman's The Will Rogers Follies and the book for Applause, the musical adaptation of All About Eve. Along the way, she won seven Tony Awards.

As an actress, she appeared in the Merchant Ivory botch of Slaves of New York and even did an uncredited turn as Garbo in Garbo Talks. Hell, she even acted on an episode of Frasier.

Tweet

Labels: Astaire, Awards, Comden and Green, Donen, Garbo, Gene Kelly, MacLaine, Merchant Ivory, Musicals, Obituary, Television, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, November 23, 2006

The Lay of the Land by Richard Ford

With The Lay of the Land, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Richard Ford sets out to turn his character of Frank Bascombe into a New Jersey version of Rabbit Angstrom, complete with asides to current events (in this case, the contested 2000 presidential election) and to give Bascombe a trilogy following his great debut in The Sportswriter and his masterful return in the novel that won him the Pulitzer, Independence Day. Unfortunately, the third time is not the charm for Ford or Bascombe, as The Lay of the Land seems aimless and meandering and lacks the forward momentum that made the first two Bascombe novels, especially Independence Day, so superb.

This time out, Bascombe still works in real estate, though his second marriage has disintegrated thanks to unexpected arrival of his wife's long-missing first husband. On top of that, Bascombe himself still is dealing with the death of a son and his own brush with mortality with a case of prostate cancer.

While Ford still has great skills as a writer of both prose and dialogue and creates many memorable scenes throughout The Lay of the Land, the novel as a whole fails to come together and while you muddle through its 400-plus pages you spend a great deal of time being reminded of other authors who have covered similar territory and better. In addition to the obvious parallels to John Updike's Rabbit Angstrom, the health plight of New Jerseyan Bascombe can't help but recall many of Philip Roth's works and, as good as Ford can be, he can't compete with those two giants.

Part of the problem I think stems from the fact that the previous two Bascombe novels were great as novels, not necessarily because of the Bascombe character. Since this novel seems lacking, the character alone can't carry it. I was a big fan of The Sportswriter and Independence Day, so The Lay of the Land proved particularly disappointing to me.

Tweet

Labels: Books, Fiction, Roth, Updike

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

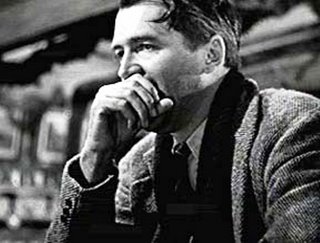

Robert Altman (1925-2006)

This is an appreciation that I hoped I would never have to write but one that I knew would come eventually. I’m grateful that the Academy gave him his due, albeit honorary, last year before it was too late because film lovers are unlikely to know a true original like Robert Altman ever again. His revelation about his heart transplant also made for one of the most touching moments on one of the Oscar telecasts in years.

I was fortunate enough to interview the great man in 1994 for a press junket for Ready to Wear, one of his least successful efforts but one which he repeated a line he often said about many of his films:

"I think it's a lot better film than anyone will discover until about a month after it's opened and played. I find that all of these films are like your children and you tend to love your least successful children the most, but they're finished and the cord's cut and it's out there and it ... doesn't belong to me anymore."

Now, Altman himself belongs to the ages as well.

When I wrote about A Prairie Home Companion earlier this year, I said how the film, though light in tone, seemed like a career summation of sorts for Altman. The Associated Press even reported that at the Minnesota premiere of the film earlier this year, Altman said, "This film is about death." Even though he had made plans for a fictional version of the documentary Hands on a Hard Body, I guess this has proved to be the case.

I’ve written so often on this site about Altman and many of his films, that I feel as if I’d be repeating myself if I went much into specifics here when you can readily access my thoughts in my indexes. I do think it’s worth remembering his contribution as the director of Tanner ’88, which really was the first great HBO series when he collaborated with Garry Trudeau on a fictional Democratic presidential candidate and got many real-life politicos to play along. It even earned him an Emmy. Sadly, its sequel, Tanner on Tanner, didn’t reach the same heights. I’ve never talked about some of his other works such as The Long Goodbye, Secret Honor and California Split.

I think in many ways Altman stands alone among our greatest filmmakers in that for every masterpiece he produced, he also conjured up real clunkers like Quintet and Beyond Therapy, but I think it was more a symptom of his willingness to take chances more often that most working directors would ever dare. So many moments from so many films rush through my mind. Barbara Harris finally getting her shot in the spotlight in the most tragic of circumstances in Nashville. The hilarious reveal that Tim Robbins is a cop in Short Cuts. Elliott Gould feeding his cat as Philip Marlowe in The Long Goodbye. Warren Beatty slowly, ultimately fruitlessly, fleeing gunmen in the snow of McCabe & Mrs. Miller. The long closing in on the diner at the opening of A Prairie Home Companion accompanied by Kevin Kline's hilarious voiceover.

I’ve mentioned it before but in that same 1994 interview, Altman said that he always felt that most movies, especially his own, improved on a second viewing because the viewer could relax and stop worrying about the plot and just let the movie unfold. Now that Altman’s entire career is before us, it’s a good time for those of us who loved him and those unfamiliar with much of his work to take the opportunity with the prolific body of work he’s left us. This doesn't even take into account all the films he produced for others, especially Alan Rudolph, such as Afterglow and Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle, or films I didn't even realize he produced such as Rich Kids and The Late Show.

The online tributes should be plentiful so I'll include some as I learn of them. Also, please leave some thoughts here as well and join in the communal mourning. Dennis Cozzalio at Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule has a superb remembrance up. Keith Uhlich has one as well at The House Next Door. John Maguire at Confessions of a Film Critic also joins in the mourning. David Hudson at GreenCine Daily is compiling a multitude of salutes. For links to my writings on Altman and some of his films:

Beyond Therapy

Brewster McCloud

Buffalo Bill and the Indians or Sitting Bull's History Lesson

Fool for Love

interview (1994)

MASH

McCabe & Mrs. Miller

Nashville

O.C. and Stiggs

A Perfect Couple

The Player

A Prairie Home Companion

quick takes

Quintet

Ready to Wear

Short Cuts

Tanner '88

A Wedding

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Awards, HBO, Kevin Kline, Obituary, Oscars, Television, Tim Robbins, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

A Less Than Singular Sensation

“She walks into a room and you know she’s uncommonly rare, very unique, peripatetic, poetic and chic…”

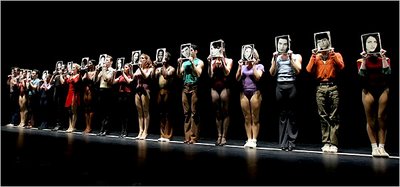

By Josh R

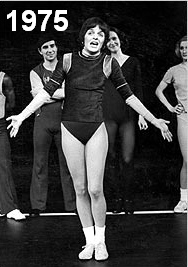

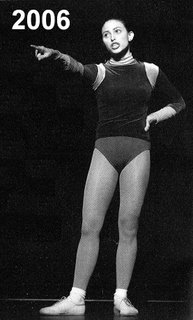

This lyric from the song “One,” penned by Edward Kleban, might well be used to describe the reaction which greeted the 1975 off-Broadway premiere of A Chorus Line. Hailed by critics of the day as an instant classic, it quickly transferred to the Shubert Theater on Broadway, where it ran and ran and ran, amassing an incredible total of 6,137 performances before hanging up its well-worn taps and fraying ballet slippers in 1990. Its storied run ensured its status as the most successful American musical of all time, although its tally was eventually eclipsed by some frolicsome felines and a disfigured opera buff imported from Great Britain (the less said about that, the better). Thirty years after its initial premiere, A Chorus Line is back on Broadway in a sleek new production helmed by Bob Avian, who co-directed the original version with Michael Bennett. While offering fleeting indications of what made the original a self-described Singular Sensation and cultural touchstone, this new incarnation ultimately falls short of duplicating that effect.

It’s still peripatetic, to be sure — the Bennett choreography, recreated by original cast member Baayork Lee (Bennett's longtime assistant), is among the very best to be seen on Broadway in this or any season, and the chic factor provided by the show’s bold concept still retains much of its galvanizing punch. In a certain respect it achieves a simple kind of poetry, thanks to the well-crafted lyrics of the late Mr. Kleban and the kinetic pop rhythms of Marvin Hamlisch. As to the qualities prescribed by the remainder of the lyric, uncommonly rare and very unique ... well, three out of five ain’t bad. When this lady walks into the room, even if you haven’t seen her before, you may very well wind up feeling as though you have. A Chorus Line can still strut its high-kicking stuff as well as any show in town, with dancers who can fly through the air with the greatest of ease — but apart from a few moments, the production as whole remains disappointingly earthbound.

If my disappointment seems more pronounced than it would with just any other revival, it need be stated that A Chorus Line is not just any show. To understand how and why it remains among the most celebrated of all stage musicals, it’s worth noting how revolutionary it was for its time. Michael Bennett, arguably the most revered director-choreographer of his generation, gathered together several Broadway dancers to discuss their lives and experiences, both on and offstage, in a series of taped sessions over the course of several years. The show that emerged as a result was culled directly from their anecdotal testimony (litigation continues to this day as to who’s owed what in terms of royalties), creating a startlingly honest portrait of a community of working professionals who practiced their trade not as stars, but as background players. The show introduced an element of realism to the Broadway musical that had previously been absent — other shows that had diverged from the template of escapist entertainment, such as Fiddler on the Roof, Hair and Company, had always seemed to favor a theatrical style based in a heightened, alternative reality. In chronicling an audition for a Broadway chorus that took place in a single afternoon in real time, A Chorus Line, with its pared-down look and naturalistic sound and feel, was a marked departure from what had come before.

The expectations in 1975 were minimal at best — the show had no built-in commercial appeal to speak of, with no name-brand stars nor element of spectacle, and sexually frank subject matter that was hardly conducive to attracting family audiences and the tourist trade (it may have been the first hit musical to feature gay characters who existed outside the realm of comic caricature). The reviews were uniformly enthusiastic. While the off-Broadway run quickly sold out, the show was still not considered a likely candidate for mainstream success. Original cast member Robert LuPone later recalled that he knew it had struck some kind of deeper nerve when he looked out his dressing room window one night an hour before curtain and saw an endless line of limousines pulling up to the tiny downtown Public Theater, stretching for blocks and blocks as far as he could see. When, within a matter of weeks, the likes of John Lennon, Jackie O, Katharine Hepburn and Henry Kissinger could all be seen in attendance, it was clear that the show had taken on a life of its own in the media and beyond. The practice of ticket scalping may have actually been born out A Chorus Line’s success off-Broadway.

Does the show live up to its exalted reputation? Not entirely — it hasn’t aged nearly as well as Chicago, the Kander and Ebb musical that had the misfortune to make its Broadway bow in the same season as A Chorus Line and was more or less trampled in its wake (the irony here is that the current Broadway revival of Chicago stands a good chance of surpassing the original Chorus Line’s performance total). While A Chorus Line has many merits, not the least which are its outstanding score and choreography, you can’t help catching a whiff of mothballs in the air when the characters stop dancing and start talking. The retro attitudes of the script hardly derail the show, but they do make what once looked like a home run look more like what is, at best, a three-base hit. Still, the show still has the potential to deliver the goods — a potential that goes sadly unrealized for the most part at Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre.

I saw the original Chorus Line late into its run, so I can’t really testify as to what the effect may have been with the inaugural cast. However, it bears mentioning that, with few exceptions, all of the principal performers in the production that opened at the Public Theatre in 1975 were playing characters directly based on themselves — the bulk of the dialogue from the show had come verbatim from the taped sessions. This clever conceit lent an element

of authenticity to the proceedings that couldn’t have been faked. For the new mounting, Avian and Lee have in many cases chosen actors who sound (and often look) to a remarkable degree like their original counterparts — they’re a capable bunch, and entirely credible on their own terms, but at the same time, you’re aware that something is missing. When Natalie Cortez sings the wonderful ballad of comic frustration entitled “Nothing,” based on Tony-winner Priscilla Lopez’s wounding real-life experiences at Manhattan’s High School for the Performing Arts in the early 1960s, her delivery is assured and vocally precise. If it lacks the urgency of Lopez’s rendition, which can be heard in all its splendor on the 1976 recording, the fault can’t really be charged to Cortez. We can and should take Avian to task, however, for not encouraging his new discovery to put her own distinctive stamp on the material, rather than delivering a reasonable facsimile of the original version.

of authenticity to the proceedings that couldn’t have been faked. For the new mounting, Avian and Lee have in many cases chosen actors who sound (and often look) to a remarkable degree like their original counterparts — they’re a capable bunch, and entirely credible on their own terms, but at the same time, you’re aware that something is missing. When Natalie Cortez sings the wonderful ballad of comic frustration entitled “Nothing,” based on Tony-winner Priscilla Lopez’s wounding real-life experiences at Manhattan’s High School for the Performing Arts in the early 1960s, her delivery is assured and vocally precise. If it lacks the urgency of Lopez’s rendition, which can be heard in all its splendor on the 1976 recording, the fault can’t really be charged to Cortez. We can and should take Avian to task, however, for not encouraging his new discovery to put her own distinctive stamp on the material, rather than delivering a reasonable facsimile of the original version. That, in a nutshell, is the problem with this Chorus Line — in its slavish insistence on creating an exact replica of the original production, it more or less gives up the ghost as far as spontaneity is concerned. In addition to Avian and Lee, who recreate the Bennett staging right down to the poster poses, Robin Wagner and Theoni V. Aldredge have also been recruited to recreate (with minimal modification) their original sets and costumes. It’s an understandable impulse not to tamper with a winning formula, but it also indicates a certain lack of confidence in the material. It would have been a mistake to make a radical departure from the template by going in a completely different direction — Richard Attenborough’s misbegotten 1985 film version bore about as much relation to the world of Broadway musicals as a broadcast of Dance Party USA — but the anti-revisionist sentiment that fuels this production seems to have been motivated more by anxiety and trepidation than by any nobler impulse. Would contemporary audiences accept a modernized version of a piece that is, both in terms of style and execution, so specific to the 1970s? Avian’s solution is not just to treat the show as a period piece, but by maintaining it like some sort of holy shrine, its relics not to be disturbed a fraction of an inch. This is less objectionable than Gus Van Sant’s frame-by-frame reshooting of Psycho in terms of intention: this is, after all, the original creative team trying to preserve their work rather than a bunch of would-be mimics pirating someone else's vision — but their efforts only serve to make the material seem more dated than it otherwise would have. The only way this questionable strategy might have worked is if the show had been cast with performers who were charismatic enough to make the roles their own. As they are, these Broadway babies look right and sound right, but there’s no sense of genuine personality in evidence to make them come across as more than stock figures (This is a problem given that the entire point of the show is to bring human dimension to people who are traditionally written off as singing-and-dancing clones). Some of the best lines in the show belong to the acerbic Sheila — they were not the work of the show’s librettist, but came directly from the mouth of Kelly Bishop, the actress who eventually played the role in 1976 and won a Tony for her performance (as with Lopez, she was playing a character based on herself and essentially telling the audience her own life story). Deirdre Goodwin, who plays Sheila in this production, delivers the character’s dry putdowns and zingers with the requisite hauteur, but fails to make the character interesting — her behavior feels like so much empty posturing, and she commands less attention as a result. It doesn’t help if you know Bishop from her standout work on Gilmore Girls, playing a similarly caustic character — you can actually hear the actress’ natural inflections in the lines even while they’re being spoken by someone else.

The creators’ dilemma is understandable — realistically, they had no chance of recapturing the excitement of the original production, even if they had made more of an effort to bring something fresh to the proceedings. But the strategy of immaculate preservation ultimately does more harm than good — rather than living up to its billing as a Singular Sensation, this Chorus Line feels more like something off the assembly line.

Tweet

Labels: Ebb, K. Hepburn, Kander, Musicals, Theater, Van Sant

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, November 20, 2006

The Wire No. 47: Misgivings

BLOGGER'S NOTE: As always, know that spoilers lie below, so don't venture further unless you've seen the episode or don't care if you know what happens.

By Edward Copeland

With each passing week, The Wire is packing so much into each episode that these recaps seem to grow longer and longer, so I have left some things out regrettably. Thomas Carcetti now is officially the mayor-elect — having won 82% of the vote in the general election. We even finally learn (in passing) that Col. Cedric Daniels' ex-wife Marla won her race for a council seat.

Still, the official campaign may be over but the political maneuvering doesn't even stop to take a breath, especially with State Sen. Clay Davis

, who continues to play all sides against one another for whatever his true aims may be which, in reality, may be just to fuck with people. He tells Burrell that he'll take care of his interests and recommend he reassert himself as commissioner since it's clear that Carcetti doesn't have the guts to fire him. Burrell asks Clay what he should do, since all his actions are supposed to go through Rawls now. "Some kind of police shit — I don't know," Clay tells him. Soon, Burrell has embarked on a new round of "quality of life" street sweeps. Lt. Mello (the real-life Jay Landsman) takes his complaints about the needless police actions to Col. Daniels, who then goes to Carcetti, to make certain the order didn't come from him. Carcetti is understandably furious — and this comes after Davis pops up in his office offering apologies for his actions during the campaign. "You gonna give the money back?" Norman asks sarcastically. Clay smiles and then plays along that he's on board with plans to rid the department of Burrell, but neither Carcetti nor Norman buy it, Norman pointing out that Davis is apologizing for the short con in one sentence before laying out the long one in the next. Later, Davis and Burrell huddle with Council President Campbell, with Davis particularly expressing concern that Daniels be stopped before he rises too far. Burrell tries to assuage their fears commenting that Daniels is "less the saint that he pretends to be."

, who continues to play all sides against one another for whatever his true aims may be which, in reality, may be just to fuck with people. He tells Burrell that he'll take care of his interests and recommend he reassert himself as commissioner since it's clear that Carcetti doesn't have the guts to fire him. Burrell asks Clay what he should do, since all his actions are supposed to go through Rawls now. "Some kind of police shit — I don't know," Clay tells him. Soon, Burrell has embarked on a new round of "quality of life" street sweeps. Lt. Mello (the real-life Jay Landsman) takes his complaints about the needless police actions to Col. Daniels, who then goes to Carcetti, to make certain the order didn't come from him. Carcetti is understandably furious — and this comes after Davis pops up in his office offering apologies for his actions during the campaign. "You gonna give the money back?" Norman asks sarcastically. Clay smiles and then plays along that he's on board with plans to rid the department of Burrell, but neither Carcetti nor Norman buy it, Norman pointing out that Davis is apologizing for the short con in one sentence before laying out the long one in the next. Later, Davis and Burrell huddle with Council President Campbell, with Davis particularly expressing concern that Daniels be stopped before he rises too far. Burrell tries to assuage their fears commenting that Daniels is "less the saint that he pretends to be."

Meanwhile, some in the police department are actually doing their work. While the silly sweeps continues, McNulty manages to piece together a pattern to a series of church break-ins and brings in the culprit. Later, while sharing dinner with his sons and Bunk and his son, his ex-wife (Callie Thorne) pays a visit and comments on the new nondrinking McNulty. "If I'd known you were going to grow up to be a grownup...," she says, an interesting contrast given her role on Rescue Me opposite another sometimes recovering alcoholic, though at least Thorne's ex character on The Wire isn't insane. The efforts of others in the department aren't nearly as fruitful. Carver busts Namond for the first time, though he displays a soft side for the lad when he learns his mom has left him alone to travel to New York to see the musical of The Color Purple and instead of sending him to "baby booking" when Namond expresses concerns about the environment there, Carver lets him stay on the bench in the squad room before Namond eventually mentions Colvin as a possibility and Bunny agrees to take him for a night. Namond stays on his best behavior, though he doesn't get Colvin's Eddie Haskell reference. Colvin has his own problems as well as he and Dr. Parenti find nothing but skepticism from the school district superintendent as they attempt to save their class and avoid her order that everyone drill for the standardized tests.

Herc brings food to Bubbles, trying to make amends for letting him down before and gives Bubbles a cell phone so he can call him immediately if the thug whom Bubs describes as being "like some Terminator and shit" arrives again, though of course Herc's real preoccupation remains the missing video camera. Sydnor finally talks Herc into confessing to Marimow to avoid worse problems which Herc can't get out thanks to Marimow's wandering mind — but he manages to leave Bubs in the lurch again, though Bubbles later unleashes a revenge on Herc that could have repercussions on the sergeant's career.

The police officer behaving the absolute worst is Officer Walker (Jonnie Brown), a character that has been built slowly in the background as a bad egg, first by taking Randy's cash in the premiere and later by stealing from Bubbles. This time though, his corruption leaves a mark — on junior car thief Donut's hand. Just talking with police takes its toll on other characters when Little Kevin returns from his incarceration and Bodie and Poot urge him to talk to Marlo — though Marlo doesn't seem convinced that Kevin stayed silent and offs him anyway. Kevin also clued Marlo in to Randy's role, but Marlo tells Chris and Snoop that Randy is no threat — but he should be tagged as a snitch, which he is at school. Later, Slim gives Bodie the bad news about his "boy" and Bodie begins to question once again the way Marlo works, recalling with Poot when they killed Wallace, but making the distinction that Wallace actually snitched and Kevin didn't say a thing.

Following Michael's appeal to Marlo about Bug's father, he explains in vague terms to Chris and Snoop that he just wants him gone and Chris seems to understand the implication, suggesting that Chris himself has been a victim of sexual abuse in the past. When Chris and Snoop finally meet up with the man who insists that he hasn't been out of prison long enough to piss anyone off, Chris grills him about his interest in boys before beating the man to death with such force that even the usual stoic and cold-hearted Snoop seems horrified by the ferocity of the fatal assault.

Tweet

Labels: David Simon, HBO, The Wire, TV Recap

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, November 18, 2006

Murder on the Environmental Express

By Edward Copeland

During the course of this excellent documentary, the filmmakers put up title cards detailing the possible suspects for the crime mentioned in their title Who Killed the Electric Car? Since they couldn't know it at the time, I wonder if another suspect could be the documentary branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences which, as in the case of the great film Anytown USA, left this spectacular documentary off their short-list for the documentary feature prize as well.

At barely more than 90 minutes long, I can't recall any documentary that moves with as much speed as this one. Though it does seem at times to be repeating the same points, it still proves to be a fascinating tale about the multitudes of people and industries who, while not necessarily in collusion, ended up conspiring by their actions in eliminating a sleek, practical electrical vehicle from the roadways.

Ironically, the man who initially ordered the development and manufacturing of the EV1 (initially given the unfortunate name of Impact) was none other than former GM CEO Roger Smith (Yes — that Roger Smith, from Roger & Me fame), though unfortunately his successors at GM didn't share this enthusiasm for the vehicle, setting out to try to fudge numbers showing actual consumer demand for the project and refusing to allow anyone to buy the vehicles, letting them only lease them so that once the leases were up, though the people driving them wanted to buy, they were not given that option and all the vehicles were reclaimed before heading off to their eventual destruction.

However, it wasn't the auto industry itself that killed its own baby — the oil companies, the government and even to some extent skeptical consumers played a hand in striking the many fatal blows of what looks like a great product that now is no longer available. Writer-director Chris Paine's documentary is as sleek as the car itself and truly illuminating. It shouldn't be missed.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Documentary

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

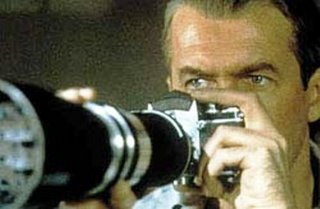

What if George Bailey had vertigo?

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post is part of the Hitchcock Blog-a-Thon being coordinated at The Film Vituperatem.

By Edward Copeland

As a blizzard bears down on him, a despondent George Bailey stares off a bridge into a storm-tossed river, contemplating what it would be like if he'd never been born. Before he can take his final plunge though, another man slices through the air and into the water, prompting George to save the stranger's life, much as Scottie Ferguson would save Madeleine from the San Francisco drink 12 years later in a different film by a different director. George and Scottie were brought to screen life by the same actor, James Stewart, but the films in which these two characters debuted came courtesy of two very different directors — Frank Capra and Alfred Hitchcock.

Capra used Stewart first and, when examined, the director's development of an all-American image for Stewart as the embodiment of the everyman Hitchcock needed to fully explore the average person's darker side. If it weren't for Capra's work in three films, most specifically Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and It's a Wonderful Life, Hitchcock would have had more work to do when he used Stewart in four films. As it turned out, Capra's part in generating Stewart's image lent Stewart added dimensions that Hitchcock ran with from the very first time he aimed his camera on him. Donald Spoto wrote in The Art of Alfred Hitchcock:

Stewart's professional persona is strikingly inverted in the Hitchcock films, and that is a perfect paradigm for the surprise his audience should feel in locating a similar darkness within themselves. We do not generally see James Stewart in these terms. But of course in Hitchcock's film, what you see isn't what you get.

It was Stewart's second film for Capra, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in 1939, that Stewart firmly established himself as the ultimate Capra hero. Jefferson Smith was a slightly dull but completely kind-hearted man who finds himself the pawn of powerful politicians' power games. He suddenly finds himself a senator, basking in the glow of serving the public good in the world's symbolic center of democratic principles, principles that he soon learns are slightly perverted. As this good man attempts to stand his moral ground, his loss of innocence and growing cynicism turns into a battle-cry filibuster for freedom. One popular misconception about Capra's works, commonly referred to as "Capracorn," is that everything in is goodness and light in the Capra universe, when nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the presence of corruption and dark elements in Capra's films with Stewart and in general could be seen as sowing the seeds in Hitchcock's head to explore his own areas of interest through an appealing and sympathetic actor such as Stewart.

It can be no accident that the time lapse between the ultimate fruition of the Capra-Stewart relationship (It's a Wonderful Life) and Stewart's first work with Hitchcock (Rope) was only two years. In fact, the way Hitchcock inverted and expanded on Stewart's Capra-created screen image may be best exemplified when comparing those two specific films. A minor technical difference between Capra and Hitchcock's use of Stewart could be read as symbolic. All of Stewart's work with Capra was in black-and-white, in a universe where good men can have bad times but where they always triumph in the end, a world where heroes and villains are clearly delineated. When Stewart prepared to work for Hitchcock, the Master of Suspense chose this film as the time for his first venture into color filmmaking, a move that could be said to "color" the characters Stewart played for Capra and paint more layers onto them.

The subtexts of these two films are quite interesting. Consider that George Bailey believes that life would have been better if he'd never been born. Rope's Rupert Cadell wouldn't go that far, but theoretically he holds the view that murder should be a privilege reserved for the superior. Both Cadell and Bailey have their beliefs proven wrong: Bailey through a journey through a world that never knew him, Cadell by having his theories fulfilled and thrown back in his face. Both journeys, one fantasy and one real, horrify in their own ways but both end with the same result — both characters end up with a renewed sense of life. However, whereas George Bailey's is one of optimism and restored faith in himself and mankind, Cadell's is one of questioning one's own philosophy. George Bailey realizes powerfully that every life touches others in important ways. Rupert Cadell finds that book-learned approaches to meaningless lives can have results deadly to all of mankind if put into action.

Another interesting overlap between Cadell and another Capra-Stewart creation, Jefferson Smith, are similar professions or former professions of the two characters. Smith was a scoutmaster, leading a group of faithful boys who helped carry out his noble civic duties. The implication clearly is that these kids will grow up to serve society well. In Rope, Cadell was a former housemaster to the characters of Brandon and Philip and the theories and philosophies he passed on to them ended up creating two men who test Cadell's beliefs out by murdering one of their fellow pupils. Another similarity between George Bailey and three Hitchcock characters Stewart created (in Rope, Rear Window and Vertigo) is that all four characters sustained injuries in some sort of arguably heroic duty. The young George Bailey suffered a hearing loss following his ice rescue of his younger brother. Rupert Cadell's handicap has become a limp, one attributed to service during wartime. The limp became a broken leg for the overzealous photographer Jeffries in Rear Window before Vertigo transformed an injury that required a corset or cane into a purely psychological wound for Scottie Ferguson.

It seems perfectly appropriate that Stewart's progression through his Hitchcock films should eventually become completely psychological, since Hitchcock's method of working focused on implications from the actors, not actualizations. Stewart's performances, albeit among the greatest of his career, in Hitchcock's movies grew more and more subtly. In contrast, the Stewart of Capra's films wears his emotions on his sleeve. Take this piece of dialogue from It's a Wonderful Life: "Now you listen to me. I don't want any plastics and I don't want any ground floors and I don't want to get married EVER to ANYONE. Do you understand that? I want to do what I want to do!"

Comparatively, these lines could just have as easily been spoken by Rear Window's Jeff to Grace Kelly's Lisa instead of George Bailey saying them to Donna Reed's Mary. Therein lies a crucial component of Stewart's Capra persona that Hitchcock appropriates. Jeff's aversion to marriage doesn't have to be spelled out because Stewart has brought that part of his persona to the movie with him from his earlier role as George Bailey. Coincidentally or not, both George and Jeff end up involved despite themselves. Also, in an amusing side note, both Rear Window and It's a Wonderful Life contain sequences involving Stewart's characters engaging in the practice of girlwatching. Stewart's cinematic baggage was important to the Hitchcock films for more reasons than just placing a dark spin on a likable performer. Stewart was more than just someone associated with Capra, he was the epitome of and symbolic representation of the entire Capra universe which, to some extent, Hitchcock tried to expose throughout his career. One can't help but wonder if Shadow of a Doubt had been made later and Stewart agreed to play a killer, whether he could have made for an interesting Uncle Charley. Granted, Joseph Cotten was perfect in the role, but it could have carried so much more weight to see the idyllic Stewart playing a serial murderer of widows. Stewart's transformation in the Hitchcock films even shows signs of pervading past the obvious twists seen in Stewart's characters.

Early in Rope, before Rupert Cadell has entered the picture, John Dall's character of Brandon shows definite signs of Stewart-like behavior as he tries to calm his accomplice's fears. In fact, in some early scenes where he talks of Rupert, Dall's facial expressions even suggest Stewart's trademark intelligent "aw, shucks" quality quite explicitly. Hitchcock seems quite enamored of the world Capra creates, loving to show its dark underbelly. It is difficult to find a reverse process in Capra's films — except for the strange presence of a crow in practically every scene set in the Bailey Building and Loan in It's a Wonderful Life. While birds represent chaos to Hitchcock, it remains unclear what significance the black bird provides for Capra in his holiday classic, though it seems unlikely the crow flew off with the missing funds that George's uncle misplaced.

The most important aspect of what Stewart brings to a Hitchcock film could be what Spoto describes in The Dark Side of Genius as an attempt for Hitchcock to develop a successful surrogate for himself. Spoto wrote in reference to Rear Window:

James Stewart would serve as Hitchcock's chair-bound alter ego, a photographer whose mobility is limited by head-to-toe plaster cast. Stewart is clearly a Hitchcock surrogate in Rear Window. The character's wheelchair resembles a director's chair; with a long lens he spies on his neighbors (seen through the rectangular "screens" of their open windows). ... Also like Hitchcock, he watches and admires as a woman models a dress and a nightgown for him.

Also, as Spoto points out later in the same book:

Stewart was closer to a representation of Hitchcock himself than any presence until Sean Connery's in Marnie. Elsewhere one of Hollywood's clearest exponents of the ordinary man as hero, Stewart's image was reshaped by Hitchcock to conform to much in his own psyche. He is in important ways what Hitchcock considered himself: the theorist of murder (in Rope); the protective but decidedly manipulative husband and father (in The Man Who Knew Too Much); the obsessed, guilt-ridden romantic pursuer (in Vertigo).

Stewart, thanks to Capra's grooming as that ordinary, upstanding American, gave Hitchcock the perfect platform to show the ironies and dark side of the

charmed life. A patriotic man can leer at women just as well as a corrupt man can. Similarly, the oppressed masses can plot murder just as well as suicide, even though they both know that neither act is morally justified. The most important ingredient that Hitchcock added to the Capra recipe were the psychological elements. In Capra's films, Stewart never was haunted by hangups or lost loves, he just had everyday burdens. It is part of Hitchcock's genius that he could play off this image and expand on it. If Capra had explored these elements, George Bailey might have been the one suffering from vertigo and he would never have been able to save Clarence on his way to helping Clarence earn his wings. Regardless of the differences and similarities, what remains are great examples of cinema by two very different directors. The audience should be grateful to Hitchcock and Stewart for allowing the audience to synthesize both Stewarts and see both sides of the same coin. For all of its glory, black-and-white situations and people don't happen often, usually merging into areas of gray and Hitchcock explored this to great success by putting James Stewart in color.

charmed life. A patriotic man can leer at women just as well as a corrupt man can. Similarly, the oppressed masses can plot murder just as well as suicide, even though they both know that neither act is morally justified. The most important ingredient that Hitchcock added to the Capra recipe were the psychological elements. In Capra's films, Stewart never was haunted by hangups or lost loves, he just had everyday burdens. It is part of Hitchcock's genius that he could play off this image and expand on it. If Capra had explored these elements, George Bailey might have been the one suffering from vertigo and he would never have been able to save Clarence on his way to helping Clarence earn his wings. Regardless of the differences and similarities, what remains are great examples of cinema by two very different directors. The audience should be grateful to Hitchcock and Stewart for allowing the audience to synthesize both Stewarts and see both sides of the same coin. For all of its glory, black-and-white situations and people don't happen often, usually merging into areas of gray and Hitchcock explored this to great success by putting James Stewart in color.Tweet

Labels: Blog-a-thons, Capra, Connery, Hitchcock, J. Stewart, Joseph Cotten

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Fearing we are powerful beyond measure

"Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. We ask ourselves, Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? We were born to make manifest the glory of God that is within us. And as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same."

Marianne Williamson

By Edward Copeland

Dr. Larabee (Laurence Fishburne) has young Akeelah Anderson (Keke Palmer) read the quote that he has framed on the wall of his home office as he tries to connect with the 11-year-old, a spelling prodigy from inner-city Los Angeles he's coaching for a hopeful trip to the national spelling bee in Washington. Akeelah and the Bee is a very good film that fails to make the leap to greatness only because of the cliches and formula turns that can be seen coming a mile away in writer-director Doug Atchison's screenplay (and about three musical montages too many).

Despite these handicaps though, Akeelah and the Bee still soars, thanks especially to young Palmer who really carries the entire film on her young shoulders.

Sure, there are many fine actors around her (Fishburne, Angela Bassett and Curtis Armstrong, to name a few), but the entire enterprise wouldn't prove as riveting and touching as it is if not for Keke Palmer. She's got the sass and the smarts of her character down pat and truly makes a viewer care for her plight even while the film's structure makes it clear how the beats of the story are going to play out.

Fishburne, who also was one of the film's producers, plays Larabee well, as you'd expect, but it's very reminiscent of characters he's played before. Bassett is good, though she's saddled with the role of the skeptical mom who predictably comes to cheer on her daughter's spelling quest.

For fans of HBO's great television series The Wire, there is much in Akeelah and the Bee that will play as if it's a companion piece to this season's story arc, with failing inner-city schools and even the presence of Julito McCullum (Namond on The Wire) as Akeelah's would-be gang-banger older brother.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Fishburne, HBO, The Wire

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, November 13, 2006

The Wire No. 46: Know Your Place

BLOGGER'S NOTE: As always, know that spoilers lie below, so don't venture further unless you've seen the episode or don't care if you know what happens.

By Edward Copeland

Omar asks Bunk if he is his ride when he meets him after being released from the gates of the county lockup. "I'm your motherfucking savior," Bunk spits acidly back at Omar. In this week's episode of The Wire, a lot of characters could use saviors, for issues both serious and trivial.

Bunk makes it clear to Omar that he could still come back at him since Stringer Bell remains one of his open cases, but he makes Omar promise: No more killings and no more bodies and no vengeance against those who set him up. The rip 'n' run artist reluctantly agrees, realizing that he's indebted to Bunk but that doesn't stop him from scouting out the convenience store to try to figure out why Old Face Andre set him up and at whose behest.

Old Face Andre has decided it's best to lie low, since he knows it's only a matter of time until Marlo figures out that he backed out of his story and will send Chris and Snoop his way. Omar isn't even a consideration — but he figures he needs help, so he finds his way to Prop Joe's repair shop to appeal for help selling his store. Joe advises Andre that his best solution is to get the hell out of Baltimore, but Andre claims he doesn't know anything but this city before accepting Joe's offer of $2,000 for his store and a northbound ride. Unfortunately for Andre, Slim takes him for that ride — and it leads straight to Marlo, Chris and Snoop and the end of Old Face Andre. Prop Joe has other business with Marlo this week, giving him Herc's card and warning him that he's with the Major Crimes Unit that took down Barksdale and had Stringer's cell phone. He advises Marlo to dump his cell phones, either not realizing (or choosing not to tell Marlo) that MCU ain't what it used to be and Herc is a major league numbskull. He also informs him that the New Yorkers have fled the city after Chris and Snoop dropped enough of their numbers to make them retreat.

More evidence of Herc's indifference and incompetence happens to come down on poor Bubbles' head. He seeks help from Kima to deal with the street thug who keeps ripping him off, but Kima tells Bubs there's not much she can do now that she's with homicide. "If bad boy happens to kill me, then you could help me?" Bubs asks Kima sarcastically and she suggests he help Herc out and then Herc can help him. Bubs, as always, delivers on his end, helping Herc identify Little Kevin (Tyrell Baker) in his continued quest to serve up Lex's murder to cover up for his lost video camera. Of course, Herc's obsession leads him to ignore Bubs' call for help and leads to another beating while his interrogation of Little Kevin leads to nothing more than Kevin figuring out that Randy gave him up. Little Kevin's "boss," Bodie gets a welcome visitor back to his staff with the return of Poot (Tray Chaney) who has been released from prison after serving a short sentence related to the Barksdale takedown. Bodie also has to contend with Namond, not so much for the young man's performance as for the constant pestering he receives from his mother and he begs Namond to keep her away.

Namond ends up on the winning team of a model-building contest in Bunny's experimental class and is rewarded with a dinner out to Ruth's Chris Steak House, where Namond and his classmates feel particularly out of place. Also on the school front, Randy, thanks to Dukie's Internet skills, realizes he can get cheaper candy — if he buys it online, only he lacks a credit card, which he talks Prez into supplying if Randy gives him cash up front — cash Randy makes playing craps using the probability skills that Prez has taught him. Prez and the other teachers at Tilghman Middle School also get the unfortunate news that no matter what their subject is, the district superintendent has mandated that all classes drill the students in language arts in preparation for a standardized test that will determine the school's future and funding under No Child Left Behind. Prez realizes that the order is reminiscent of "juking the stats" back in the police department. Elsewhere, Carver inquires to Cutty about Namond and learns his connection to Wee-Bey. Cutty insists that Namond may carry the same blood as Wee-Bey, but not the same heart.

Michael continues to express disdain at the return of Bug's father (Cyrus Farmer) and gives more hints of the abuse that must have occurred by his hands as he expresses his mistrust of most men, including Cutty, who he deems "too friendly." Out of desperation, Michael turns to the only person who thinks might be able to help him with his problem — Marlo. On the other side of the law, Carcetti continues to face resistance to any plans to remove Burrell from power, this time from City Council President Nerese Campbell (Marlyne Afflack) who feels Mayor Royce betrayed her by running again when she felt she was next in the mayoral line of succession and Carcetti jumped ahead of her. Norman floats the idea to Carcetti that maybe they can get Burrell to quit of his own accord, especially after Carcetti orders that Rawls will have actual operational control of the department and anything Burrell does must go through Rawls and Carcetti first. Burrell has no intention of going quietly, especially once he realizes that Carcetti doesn't have the political strength to take on the ministers and the black community and fire him. "If you want me to go, you have to shitcan me," Burrell tells Carcetti with a grin as he makes plans to regain strength and thwart the moves he's seeing by Carcetti to elevate Daniels through the department.

Tweet

Labels: David Simon, HBO, The Wire, TV Recap

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, November 10, 2006

Jack Palance (1919-2006)

The man who began his career as Walter Jack Palance but later dropped the Walter and went on to score three Oscar nominations and a win was a unique screen presence almost from the moment he stepped onto it. Sudden Fear opposite Joan Crawford was just his third feature film when he received his first Oscar nomination for

supporting actor in 1952 as the young cad out to scam the lonely older woman. He repeated the feat the following year with a role that couldn't have been more different but which really cemented the Palance image we know today in Shane. His Oscar-winning turn decades later in the comedy City Slickers couldn't have existed if he hadn't left an indelible impression as Jack Wilson back in 1953 first. Yet Palance, even if his style in his later years could somewhat lend itself to parody was much more multi-faceted than that, whether it be as a struggling actor in Robert Aldrich's 1955 potboiler The Big Knife or his work for Aldrich the following year in Attack, which Wagstaff recently wrote about during the Aldrich Blog-a-Thon, "Jack Palance’s performance in Attack is a revelation. What kid scared out of his wits by Palance’s portrait of an evil killer in Shane would ever guess that the actor could show the kind of tenderness and anguished vulnerability that he does here. Outside, Jack Palance looks like the perfect dogface grunt — his face and large presence look like they were carved from a block of granite by blasting it with dynamite — but inside, a sensitive soul that the heart aches for shines through." His great work wasn't limited to features either, as anyone who has had the chance to see his touching portrayal of an addled boxer in Rod Serling's television version of Requiem for a Heavyweight will tell you. For me, not the biggest fan of Jean-Luc Godard's work, Palance was the best thing about Godard's movie about movies, 1963's Contempt. He even brought grace to a miscast role as a Mexican bandit in Richard Brooks' The Professionals.

supporting actor in 1952 as the young cad out to scam the lonely older woman. He repeated the feat the following year with a role that couldn't have been more different but which really cemented the Palance image we know today in Shane. His Oscar-winning turn decades later in the comedy City Slickers couldn't have existed if he hadn't left an indelible impression as Jack Wilson back in 1953 first. Yet Palance, even if his style in his later years could somewhat lend itself to parody was much more multi-faceted than that, whether it be as a struggling actor in Robert Aldrich's 1955 potboiler The Big Knife or his work for Aldrich the following year in Attack, which Wagstaff recently wrote about during the Aldrich Blog-a-Thon, "Jack Palance’s performance in Attack is a revelation. What kid scared out of his wits by Palance’s portrait of an evil killer in Shane would ever guess that the actor could show the kind of tenderness and anguished vulnerability that he does here. Outside, Jack Palance looks like the perfect dogface grunt — his face and large presence look like they were carved from a block of granite by blasting it with dynamite — but inside, a sensitive soul that the heart aches for shines through." His great work wasn't limited to features either, as anyone who has had the chance to see his touching portrayal of an addled boxer in Rod Serling's television version of Requiem for a Heavyweight will tell you. For me, not the biggest fan of Jean-Luc Godard's work, Palance was the best thing about Godard's movie about movies, 1963's Contempt. He even brought grace to a miscast role as a Mexican bandit in Richard Brooks' The Professionals.For many younger moviegoers out there, Palance will be best remembered for his work as a crime boss opposite another legendary screen Jack in 1989's Batman and for his Oscar-winning turn in 1991's City Slickers and its ill-advised sequel. I hope no one remembers him for missteps like the Chevy Chase misfire Cops and Robbersons and surely no one out there knows him solely as the host of TV's Ripley's Believe It or Not. He deserves much better remembrance than that — though, if only for a smile, it's worth remembering him for his one-armed pushups following his Oscar win and the comic goldmine they gave to Billy Crystal for the 1992 Oscarcast.

RIP Jack Palance.

Tweet

Labels: Aldrich, Crawford, Godard, Obituary, Oscars, R. Brooks, Television

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Oscar's cross to bear

By Edward Copeland

I recently re-visisted The Ruling Class, getting to see it for the first time letterboxed, the way God intended, and while the film itself is even odder (and much longer than I remember), one thing remains unchanged: I still believe Peter O'Toole was robbed in 1972 when he lost best actor to Marlon Brando for The Godfather.

Don't get me wrong — Brando is great and I know some argue that he's actually supporting and Pacino is lead in Coppola's masterpiece, but his win to me has seemed another example of the Oscar ripple effect where a mistake one year, bubbles over into the next year and beyond.

If O'Toole had won, they wouldn't have had to finally break down and give him an honorary Oscar (buzz for his current film Venus notwithstanding) and then Brando could have won the following year for his even more substantial turn in Last Tango in Paris. I'm sure Sacheen Littlefeather could have waited a year for her classic Oscar moment.

As for The Ruling Class itself, I still enjoy it despite its bloated length and bizarre tale. I imagine if I were British and lived in England, I'd get even more out of Peter Barnes' adaptation of his play about the maneuverings in the upper crust of British society when a bonkers man (O'Toole) inherits his father's seat in the House of Lords and his estate — much to the chagrin of his uncle (William Mervyn), who doesn't think an Earl who believes he's Jesus Christ will be a good thing for the family and conspires to gain control of the estate.

However, the film doesn't play like a straight-forward game of machinations as director Peter Medak's film frequently goes on bizarre tangents, frequent musical numbers and, finally, a particularly dark turn in the latter half of the film.

O'Toole is not alone in the excellent cast — there also are great performances by Arthur Lowe as the estate's boozy butler and closet leftist and Alastair Sim, the best screen Scrooge ever in 1951's A Christmas Carol, as a befuddled bishop.

The Ruling Class certainly is not made for everyone, but it is a fascinating artifact and I still think O'Toole was robbed.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Brando, Coppola, O'Toole, Pacino

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Sam sows his wild Oates

By Edward Copeland

Leave it to Peckinpah to fashion a love story between a man and his friend's severed head, but that's exactly what he did with 1974's Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. More importantly, he took one of his most dependable character actors, Warren Oates, and lifted him from his usual supporting roles as a heavy and gave him a lead that truly showed the range of which he was capable.

While Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia doesn't quite rise to the level of Peckinpah's greatest works such as The Wild Bunch or Straw Dogs, it is quite good. It also seems grittier and dirtier than many of Peckinpah's efforts from this same time period. It's almost as if they took the celluloid and ground it into the mud.

It's not the case of making a DVD from a bad print, it seems very purposeful. Compare it to Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid from the previous year, an inferior film to Alfredo Garcia, but which looked great. However, given the tale Peckinpah is telling in Alfredo Garcia, shimmering cinematography would have been wholly inappropriate.

There are some weaknesses — some of Peckinpah's trademark slow-motion violence starts to overstay its welcome here and aside from brief turns by Robert Webber and Gig Young, there isn't much in the way of performances to back up Oates' great work — though there is one helluva great final shot. This is the Warren Oates' show and in this case that is more than enough.

It's a shame he didn't get more opportunities to carry a film, because Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia certainly shows he could.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Movie Tributes, Oates, Peckinpah

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

Anytown USA — from the port side

By Edward Copeland

Actually, the title of this post (which chose nautical terms to avoid sounding like annoying cable news shoutfests) is a bit of a misnomer for two reasons: 1) I'm more a moderate than a doctrinaire lefty (not that Dubya hasn't been doing his best to push me that direction) and 2) This great documentary, Anytown USA, while about a 2003 New Jersey mayoral race where the candidates are identified by party really doesn't have a lot to do with partisan politics in the way national partisan politics are identified. Directed by Kristian Fraga, Anytown USA explores a contentious mayoral election in the town of Bogota, N.J., where the GOP incumbent, the legally blind Steve Lonegan, seems reviled by most of the town for his determination to send the town's high school into another school district which could result in the death of the town's high school football team.

The documentary has been making the festival rounds for quite some time and played a week in Los Angeles earlier this year, making it eligible for the Academy Award for documentary feature. Hopefully, it will be on the short list announced by the Academy later this month — because it certainly deserves it.

Enlisted to try to bounce Lonegan from office is Democrat Fred Pesce, who seems truly less than enthusiastic about joining the race. The candidates let the filmmakers' cameras seemingly watch them everywhere and whether it's due to them forgetting that the cameras were there or the prevalence of reality television programming where being seen as manipulative and villainous can prove to be assets, the camera captures them, warts and all. It is especially amazing in the case of Lonegan, who comes off as a true prick — and doesn't seem to mind. This would probably have made for a fairly interesting film alone, but while the filmmakers were in Bogota assembling their film, a wrench was thrown into the tale in the form of Dave Musikant, who decides to launch an independent write-in candidacy for the office. In a great irony, Musikant, who suffered from a brain tumor, also is legally blind (insert your own blind-leading-the-blind joke here).

Musikant's enthusiasm is almost infectious, even when it doesn't seem clear exactly what his issues are other than being anti-Lonegan. Being anti-something may be enough to help the Democrats take back power today, but in this tiny N.J. microcosm in 2003, it probably would help to be for something as well. The documentary also is great at showing how politics almost can work as a virus as you watch the likable Musikant start to play the game as any normal pol would. Part of the joys of this film is watching it unfold, uncertain of the outcome, so I'm going to avoid much further detail of what happens in the film and what the election's outcome was. However, Fraga, producer Juan Dominguez and the rest of the crew associated with this documentary have created a truly mesmerizing film. It generates more suspense that many fiction films, more laughs that a lot of comedies. If I have any criticisms of the film, they are minor ones. I for one, living in a state where write-in votes are illegal, would have liked to have seen the actual mechanics of casting a write-in ballot, since we see people going behind the curtain of the old-fashioned lever voting machines but don't see how people who vote for Musikant actually do it.

As you head to the polls this Election Day (hopefully knowing what the hell you are doing, otherwise — stay home), Anytown USA might make for a nice palate cleanser before the actual election results roll in. It is readily available on DVD for both rental and sale and includes an illuminating commentary by Fraga and our good friend Matt Zoller Seitz. Give Anytown USA — fans of documentaries and politics shouldn't be disappointed and good luck to the filmmakers. Let's hope they make that Academy short list later this month.

To read a take on the film from the conservative side of things, click here for Wagstaff's take.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Documentary

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE