Wednesday, January 30, 2008

Snapping Gyro

Teeth is a flick about a chick with choppers in her chocha. With a concept like this, you'd hardly expect the filmmakers to take this premise as seriously as they do. It’s a pretentious affair, with a first act that takes unrewarded swipes at abstinence-only programs, and a third act that lazily drags the film to its final punchline. Writer-director Mitchell Lichtenstein never finds the right note for this Vagina Monologue, sapping much of the fun out of the film in the process.

He punctuates the film with gory dismemberment, but he smothers the money shots with a constant need to justify his actions and their reasons. This is a movie that screams for a B-movie director with a sense of camp and/or terror, not a guy so terrified of his premise that he won’t even show the monster in his monster movie. I went in expecting an exercise in over-the-top Grand Guignol and walked out somewhat disgusted by Teeth’s missed opportunities and lack of a consistent tone. For all the disembodied dicks the MPAA conveniently missed when they rated this film R, Teeth is surprisingly without balls.

Dawn (a very game Jess Weixler) is part of a dysfunctional blended family living in the shadow of a nuclear reactor. Her stepbrother Brad (John Hensley) is a pierced terror who abuses his girlfriends and mooches off his father and stepmother. Brad resents Dawn because he wants to sleep with her but can’t because they are “related.” He also dislikes her because, during a game of “I’ll show you mine if you show me yours,” Dawn’s “yours” bites his finger.

Dawn is also the leader of an abstinence-only group, a dropped plotline whose Citizen Ruth-style potential is never mined. During one of her meetings, she finds herself drawn to Tobey (Hale Appleman), a fellow who, in the world of sexual activity, has stroked but not inhaled. Dawn has done nothing with her goodies, for if she did, she’d have realized that she has incisors inside her. Tobey finds this out the hard way when, after apologizing for knocking Dawn unconscious while trying to rape her, decides to continue raping her anyway. Tobey winds up dickless, drowned and dead. Dawn freaks out, wondering if this is what’s supposed to happen when you have sex.

So far, so good. But Dawn, like the film, doesn’t even bother to look in her secret box. How can a film be about female empowerment if it’s too afraid to have its heroine merely investigate her own femininity? It treats it with repulsion, not curiosity. Even the men in the dentata myth want it, no matter how nasty it turns out to be. In his attempt to be reverent for fear of misogyny, Lichtenstein kills all suspension of disbelief. If you (to use Matt Seitz’s term) de-cockified some guy with your punany, wouldn’t you be inclined to examine what’s going on in there? Dawn never does, yet later in the film, she inexplicably and suddenly figures out how to control her snapping gyro thanks to a man. Give me a break.

Teeth has nowhere to go once Dawn realizes she’s an inadvertent murderess, and its sharp right turn toward revenge drama is as abrupt as it is underwritten. Dawn meets another guy Ryan (Ashley Springer) who seems like a nice kid but who, for screenplay convenience, turns out to be a doomed to be dickless dude. Her pervert gynecologist also gets a big surprise while investigating the crack of Dawn. As for her stepbrother, well never mind, but when you see this scene, you’ll realize just how much a missed opportunity Teeth is.

Teeth, like its victims, is mercifully short. Weixler must be commended for doing her best to bring Dawn to life. I wish the film had either been a major exploitation quickie or, in its present incarnation, had the guts to give me a woman coping with the real problems a flytrap coochie. What Mary Harron or Stuart Gordon could have done with this picture! Hell, even crazy-ass Catherine Breillat would have crafted a more interesting, quirkier, and more fearless film than what’s on the screen.

Early in the film, Dawn’s class gets a censored sex-ed book. The vagina drawing is hidden by a huge gold star. That’s the perfect metaphor for Teeth.

Tweet

Labels: 00s

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

It's not always best to go second

I got through the second part of the surgically altered DVD of Grindhouse, finally seeing the extended version of Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof. Aside from Kurt Russell's fun performance as Stuntman Mike, the movie is a real letdown.

I doubt if I'd seen the shorter version I would have felt that much more favorably toward Death Proof.

In Planet Terror, all the actors seemed to be on the same page as to what type of movie they were in. In Death Proof, few of the characters have any sort of distinct personality outside of Russell, especially in the case of the first group of young women Stuntman Mike terrorizes.

Most of the actresses in the early sequence are really bad, and not in a good way. Since we spend nearly an hour with them, it gets to be unbearable.

The second group of women, which includes Rosario Dawson, are slightly better, but their repartee comes off as very tired. On top of that, Tarantino seems to have grown bored with his own movie.

Whereas the first portion of the film functions with the same spirit as Planet Terror in terms of washed-out colors and scratched-up prints, when he leaps ahead to the second batch he films an entire sequence in vivid black-and-white for no apparent reason. Then, when he switches back to color, the film seems like just any other reasonably well-shot color film.

Russell's hilarious performance can only take you so far and by the time Death Proof finally wraps up, it seems as if it had been running on empty for quite some time. It did remind me of something I meant to write in my Planet Terror review that has been driving me crazy ever since: I remember clearly going to the movie theater chain in the 1970s that played that clickety little tune that you hear over the "Feature Presentation" card of both films, but for the life of me I can't remember which chain it was.

Anyone out there have any idea?

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Kurt Russell, Tarantino

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, January 28, 2008

Twisting the Night Away

By Josh R

Blame it on the Irish.

The element of surprise has always been a crucial component of the art of storytelling — in recent years, it may have evolved from an incidental pleasure to a raison d’etre. Ever since Irish filmmaker Neil Jordan pulled both the rug and the floorboards out from under shell-shocked audiences with his 1992 film The Crying Game, screenwriters the world over have burned out their brains cells trying to devise and execute similar feats of shock and awe. The Jordan film, a gender-bending confidence trick which became a phenomenon by keeping audiences in the dark, only to jolt them out of their seats (and their complacency) by blinding them with high-wattage floodlights before they even knew what had hit them, ushered in the age of The Twist. Since then, films such as The Usual Suspects, The Sixth Sense, or seemingly anything released in the past two years involving a magician, have been conceived and marketed specifically in terms of their proclaimed ability to subvert audience expectations. In a way, the architects of these brain-teasers seem to be throwing down the gauntlet, daring us gullible boobs to crack the riddle before we wind up with as much egg on our faces as the slow-witted characters over whose eyes the proverbial wool is being pulled.

In the more rarified world of theater, writers don’t have quite as many options at their disposal when it comes to prompting jaws to drop. Without the benefit of sophisticated technology and quick-cutting scenes to cover the element of implausibility, or the ability to do rapid-fire flashbacks to tie everything together when the truth is revealed, playwrights can’t make as many abrupt about-faces. This is not to say contemporary playwrights don’t do their fair share of twisting — August: Osage County, the new work by Tracy Letts, features enough in the way of jaw-dropping surprise to cause O. Henry’s brain to short-circuit — but building suspense in the theater requires more in the way of dramatic substance. The story — the journey, really — needs to create as much interest as the place to which it’s taking us.

There’s more to Conor McPherson’s The Seafarer, the well-lubricated black comedy of drunkenness and supernatural skullduggery currently guzzling, stumbling and hiccupping its way across the stage of The Booth Theatre, than the clever, carefully revealed conceit on which its story hinges, or the 11th-hour curveball it nails squarely over the plate. Each act ends with a twist; the first one jump-starts the action (too late), while the latter — and it’s a good one, mind you — is intended as a fun coda to leave audiences with a nice buzz. This is not a play fashioned around a single instance of sleight-of-hand, and with no other reason for being — but somehow, it still manages to feel that way. Chalk this up to the fact that it simply takes too long before what we’re seeing begins to feel relevant, and the play exhausts our patience in getting to the payoffs. While the characters may be three sheets to the wind, certain elements of McPherson’s play are delivered with sober clarity — but by the time the playwright has put the finishing touches on his cocktail, he’s already past the legal limit in terms of how much latitude thirsty theatergoers will give him while waiting at the bar. If you want to keep a roomful of drunks happy, you gotta keep those drinks coming.

Lest I be accused of going overboard with the drinking references, please be assured that The Seafarer is as much about intoxication — and its uncomfortable proximity to mortality — as it is about anything else. The play observes the inebriated interactions of a group of blue-collar friends who congregate on Christmas Eve allegedly for the purpose of playing poker — but really just as an excuse for getting drunk, and staying that way for as long as they can maintain consciousness (or until their much-abused livers go on strike). The site of their revels is the depressingly run down home of Richard Harkin (Jim Norton), a puckish, nattering blind man being cared for by his joyless brother Sharky (David Morse), a slump-shouldered hulk whose hangdog countenance bespeaks having accepted failure in all things as a fate preordained. Their guests include Nicky (Sean Mahon), a handsome, cocky imbecile sharing a lovenest with Sharkey’s estranged wife and children; Ivan (Conleth Hill), a bumbling family man who looks like Dilbert’s less suave cousin and spends much of the evening searching for his glasses; and an unexpected guest, the well-heeled, cagey Mr. Lockhart (Ciaran Hinds), who is there for purposes that no one expecting a straight-faced exercise in realism should be able to divine. It turns out that the stakes of this poker game are much higher than its gin-soaked participants could ever have imagined.

It’s hard to find much fault with the basic structure of the play; as any good poker player knows, the surest way to come up short is to tip your hand right off the bat. Perhaps by necessity, there isn’t much real action to speak of during the opening act — McPherson uses it to establish the characters and their relationships, create a sense of the world in which they live, and lull the audience into a false sense of security. ‘Lull’ being the operative term here; not until the end of the first act did anything occur to pique my interest. Granted, it isn’t easy to bring a sense of cogency to the behavior of characters who function in a diminished state of clarity. With the exception of Mr. Lockhart, who is the last person to arrive, and Sharkey, who doesn’t have much to say in the beginning (he’s basically there to keep people from bumping into furniture), no one is exactly lucid. The conversation unfolds much in the same way that conversations do in bars after a few drinks; it’s hazy, far-ranging and without much sense of purpose. McPherson isn’t the kind of writer who can always hold you on the strength of his language, which is unpretentious while at the same time containing an element of ambiguity. Part of this has to do with the fact that his characters are not particularly sophisticated and can’t always put their feelings into words — but it’s also a reflection of the playwright’s reluctance to reveal too much too soon by spelling things out for the audience. When he’s at his best — as he was with the spellbinding ghost story Shining City — he draws you in by revealing the characters’ anxieties through their inability to communicate exactly what they mean to say, and acknowledging that struggle as the source of their vulnerability and isolation. The language in The Seafarer has the same basic properties — it’s elliptical, while at the same time colloquially casual — but in terms of what’s actually being said, the characters aren’t revealing much of anything. Hearing these men rattle on about nothing in particular has the effect of listening to a succession of inside jokes that you’re not quite inside enough to get, or the kind of anecdotes that usually end with the proviso “I guess you had to be there.” After a few minutes in, I was having flashbacks to mind-numbing evenings at the dinner table listening to my father and brother talking about people I didn’t know, sports I didn’t care about, and stories that seemed specifically engineered to rile my inner snob (did we have nothing more stimulating to talk about that people named Vinny being punched, or punching someone else?). As a result, the opening act feels like so much filler, as if the playwright is simply marking time before playing his trump card. It’s believable enough, and often humorous, but it has nothing in the way of tension or a sense of dramatic purpose.

To his credit, McPherson does manage to move the action forward, albeit fitfully, in the second act, when the focus is on the battle of wills between Sharkey and Mr. Lockhart — only then is the audience is drawn into a conflict with real stakes. Unfortunately, too much has been sacrificed in getting to that point, and the final coup de grace, while gracefully executed, doesn’t have as much impact as it would otherwise. When things finally start popping, it’s difficult to be fully engaged since so much of what's occured before has had the effect of alienation.

The five members of the cast certainly give it their all, and for the most part, they make the action believable even when it isn’t particularly interesting — although not all of them seem to be acting in the same play. Norton, who received the Olivier Award for his performance in London and seems poised to reap similar tributes on these shores, dominates the scenes he’s in and gets the lion’s share of the laughs. That said, one can’t shake the sense that he’s playing more to the audience than to anyone else on stage. The actor bears a physical resemblance to George Carlin, and his broad performance style evokes nothing so much as Carlin doing his drunk/stoner act. Sean Mahon does a fine job of suggesting the insecurity and defensiveness behind his vain idiot’s swagger, while Conleth Hill — Tony-nominated a few years ago for Stones in His Pockets, yet another Irish import — brings surprising credibility to a performance based in comic exaggeration. It would be very easy for the character, as he plays it, to exist solely on the level of caricature, but Hill finds creative ways to make the mannerism seem like an authentic reflection of a real personality.

As stated, it is the clash between the play’s two most compelling characters — Sharkey and Lockhart — which drives the action, and as a natural consequence, it is the actors portraying them who make the strongest impression. David Morse, a performer who achieves his effects with remarkable economy, makes the extent to which his character has been defeated by life explicit through passive physicality. When Sharkey finds the resolve to fight, Morse’s posture straightens as if an unexpected current had snapped him back to attention, and the droopy-eyed look hardens into a tight expression of coiled determination. He is well matched with Ciaran Hinds, who pulls off a sly feat of sorcery as a character who would seem to exist on a very conceptual level, but is brought to three-dimensional life with astonishingly vivid strokes. Like Morse, his transformation takes a physical form — without benefit of makeup, his bland, nondescript features sharpen into a mask of menacing terror as the layers of Lockhart’s surface geniality are being methodically peeled away. Once Hinds flips the switch, a character who has faded into the background becomes a truly frightening presence, as detached amiability gives way to reveal acid rage — one which scalds with a white-hot intensity without ever being taken over the top.

It is only in the scenes between these two actors in which McPherson’s considerable talent as a writer pierces through the prevailing sense of aimlessness that keeps The Seafarer in check. Hinds is assigned a chilling aria of torment and despair which is as hauntingly evocative as anything the playwright has ever written — my companion remarked that she was likely to have nightmares about it (I’m guessing she won’t be alone). Like Martin McDonagh, another playwright who is part of what has justifiably been hailed as a new renaissance in the Irish theater, McPherson has a keen sense of structure, and knows how to use a surprise twist to tie everything together in a way that makes dramatic sense. In Mr. McDonagh’s most recent Broadway offering, The Lieutenant of Inishmore, the final twist seemed like the punchline to a beautifully sustained, infinitely engrossing two-hour joke. The twist that wraps up the McPherson play is just as funny and feels just as right, but the time it takes in getting there isn’t as well spent. The Seafarer has much to recommend it — while its most successful passages pack the sting that can be felt after two or three hastily imbibed shots of good Irish whisky, the play as a whole may leave you feeling just about as blurry in the hours to follow.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Carlin, D. Morse, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, January 24, 2008

1 divided by 2 + footage=Planet Terror

I never got a chance to see Grindhouse in the theater though I really wanted to, but the odd way they've handled its DVD release means I will never see what others did. The much-talked about trailers between Robert Rodriguez's Planet Terror and Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof might be on bonus discs, but I didn't rent those. Of course, I also have no way of knowing what's been added to Planet Terror. I can say though that, for what it is, I enjoyed it quite a lot.

For the most part, Rodriguez really nails the look and feel of a '70s-type exploitation film and the great ensemble cast all play it just right, from Jeff Fahey as the chili cook to Josh Brolin as the asshole doctor, from Naveen Andrews' crooked scientist to Freddy Rodriguez's ostensible hero.

If I had any complaint about Planet Terror, it's when it inserts timely references such as Osama bin Laden and 9/11. They seem out of place since the film plays as if it were made in the 1970s and come off sounding like anachronisms.

The action scenes come off suitably over-the-top as does the gore, since this is a zombie film. I wish I could have seen it as Grindhouse, especially with those fake trailers in between, though the Machete preview at the opening is fun in itself.

Death Proof is up next in my rental queue, so I'll get to see the second half of Grindhouse soon, sort of.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Josh Brolin, Rodriguez, Tarantino

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Heath Ledger (1979-2008)

Here's an obit I never expected to write. I thought Ledger was among the more talented of the younger crop of actors, not only for his Oscar-nominated performance in Brokeback Mountain, but in light fare such as 10 Things I Hate About You or A Knight's Tale. I actually thought he didn't get the praise he deserved for his small role in Monster's Ball. Of course, I looked forward to see him play The Joker in Christopher Nolan's Batman sequel, but that's going to be an eerie experience now. RIP Heath.

To read The New York Times story, click here.

To read an appreciation in The Washington Post, click here.

Tweet

Labels: Christopher Nolan, Obituary

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, January 21, 2008

Up through the ground came a bubblin' crud

By Edward Copeland

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously said that there are no second acts in American lives. I was thinking about coining the phrase, "There are no third acts in Paul Thomas Anderson films," except that in the case of There Might Be Blood, there isn't much of a first or second act either.

I think my father, who saw the film with me, summed it up best. "At first, I thought it was going to be about an oil war, then I thought it was going to be him versus the preacher, but eventually I realized it wasn't going to be about anything."

To paraphrase Bob Dylan's "Maggie's Farm," Anderson has a head full of ideas that may be drivin' him insane.

This isn't to say that There Will Be Blood lacks any positive qualities, because the cinematography by Robert Elswit is phenomenal. However, the film really is a thudding bore, so much so that parts of the annoying score by Jonny Greenwood seem to actually drone like an amplified tuning fork and bear an uncanny resemblance to that sound that used to accompany the old THX "The Audience Is Listening" promos played in movie theaters.

For most of the film, Daniel Day-Lewis' performance held my attention, despite the film's ponderous pacing and lack of focus. In fact, I was at first puzzled by the people who complained that Day-Lewis was over the top. I wished I'd never read whoever said Day-Lewis was aping John Huston, because every time he spoke that image did come to mind. Unfortunately, Day-Lewis' performance goes off the rails as the film drags on and he suddenly starts devouring the scenery as if he needed it for nourishment.

I can pinpoint the exact moment when he goes wrong: The scene where he's dining with his son and a group of rival oil executives are seated at a nearby table. For some reason, Day-Lewis begins talking out loud so they can hear while a cloth napkin covers his face.

I can only assume that by this point Day-Lewis was as bored with the movie as I was. The ham gets the better of him from that point on so by the time we get to the scenes of him as an aging recluse in a large Kane-esque mansion in 1927, he's stooping and shuffling around as if he's a cousin to Marion Cotillard's Edith Piaf, dancing across the two-lane bowling alley he's built in his home. Of course, as soon as we see the bowling alley, you have to know what's coming. It's not placed there by accident, so as Day-Lewis meanders around the bowling lane, you know that balls will be employed and pins will be used for other purposes.

So much is wrongheaded about There Will Be Blood, that I hardly know where to start. Do I complain about how the portion of the film involving Paul Dano's character covers 16 years, yet the actor looks no different in age in the 1911 scenes than he does in the 1927 ones? Do I ask why Daniel Plainview makes such unnecessary complications for himself? Do I ask what is the true deal about Paul and Eli Sunday? Are they twins? The same person with multiple personalities? It hardly matters anyway.

At one point, Plainview says that he doesn't like to explain himself and that seems to apply to Paul Thomas Anderson's film as well. Now many great films have been made that toiled in the soil of the ambiguous, but they aren't all as goddamn boring as There Will Be Blood. Do I debate whether the film is asking whether it's Daniel or preacher Eli Sunday who is truly the false prophet? Perhaps Anderson is the false prophet at work here and his proponents, many of whom I know well, like and admire, are the ones being hoodwinked.

One thing I never quite understand is the insistence some of his fans have about calling him P.T. Anderson. The credit on There Will Be Blood clearly says it was written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. Is it possible some of his fans could be more pretentious than the filmmaker himself? During one outburst, Eli Sunday yells at his father that God doesn't love stupid people. I don't know if any part of that is true, but my guess is that if there is a God, he doesn't love stupid movies.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Cotillard, Day-Lewis, Dylan, Finney, Fitzgerald, Huston

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, January 20, 2008

Suzanne Pleshette (1937-2008)

That smoky voice is what I always think of when I think of Suzanne Pleshette. The years of cigarettes that produced that though claimed the actress in the end, less than a year after her husband, Tom Poston, passed away. Actually, the voice isn't really what I remember: It's her part in perhaps the greatest TV series finale ever: Reprising Emily Hartley, her character in the great sitcom The Bob Newhart Show, on the last episode of Newhart.

Her role there alone would be worth paying tribute to, but Pleshette did other things as well.

She appeared in Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds. She acted in not one, but two canine-themed Disney live-action films: The Ugly Dachsund and The Shaggy D.A.

She was a mom concerned about her daughter's mental health in Oh, God! Book II. Her extensive TV work included an Emmy-nominated turn as Leona Helmsley in The Queen of Mean.

Her distinctive voice also was one of the many used in the English-language version of Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away. She, along with James Garner, was one of the old pros called in to try to save 8 Simple Rules after John Ritter's untimely death.

On Broadway, she followed Anne Bancroft in the role of Annie Sullivan in The Miracle Worker. Still, it's Emily Hartley that will hold her place in most people's memories, and deservedly so.

RIP Ms. Pleshette.

Tweet

Labels: Animation, Awards, Bancroft, Disney, Hitchcock, Obituary, Television, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, January 18, 2008

The Best on Broadway in 2007

Compiling a list of the Top 10 achievements in Theater for 2007 presented me with a bit of a challenge. Theatergoing is not a poor man’s pursuit, so the number of things I’ve been able to see has been limited, to say the least — sadly, I wasn’t able to come up with the cash to pay for a full price ticket to the critically lauded production of Cyrano de Bergerac with Kevin Kline that just wrapped up its limited run on Broadway (the news that it was taped by PBS for a Great Performances airing sometime later this year provides some consolation). The fact that many of the productions which received Tony Awards and nominations this past June technically premiered in 2006 further winnowed down the field. Well there were many shows I liked, it was difficult coming up with ten that I genuinely loved.

Since two of the fall season’s most well-reviewed productions, Tom Stoppard’s Rock 'N' Roll and Conor McPherson’s The Seafarer, while not without merit, didn’t impress me to the extent they did others — and I have yet to see the revival of The Homecoming that everyone is raving about — I’ve decided instead to focus on the performances that made 2007 such a memorable year on the Broadway stage. Paring down that field necessitated some difficult cuts.

With apologies to the egregiously overlooked — including the legend at whose altar I worship, Ms. Angela Lansbury (it hurts me more than it does you, babe) - here are the 10 Best Broadway Performances of 2007, listed in ascending order:

Ms. Perez’s gut-busting, go-for-broke turn as a tone-deaf diva constituted the only compelling reason to make a trip to Roundabout Theater Company’s somewhat mildewed revival of the 1975 Terence McNally farce set in a gay bathhouse. In the midst of so many half-naked men, it was a woman — albeit one frequently mistaken for a transvestite — who stood out.

While the luminous Jennifer Ehle gets MVP honors for her sterling work over the entire 8½ span of Tom Stoppard’s ambitious three-play cycle, Salvage was the only one to premiere in 2007. The standout performance in the trilogy’s concluding installment was giving by Ms. Plimpton who, as the emotionally volatile Natasha, confirmed her status as a stage actress of remarkable presence and charisma.

In Mark Twain’s cross-dressing farce, the Tony-winning Mr. Butz once again proves himself to be a clown par excellence, with a talent for slapstick that transforms run-of-the-mill sight gags into bravura feats of comic ingenuity. If his scenes as a man don’t give him quite as much opportunity to really let loose, once he straps on the hoopskirts, he’s pretty much unstoppable.

The sublime Ms. Cusack performs double duty in Tom Stoppard’s intriguing examination of rise and fall of communism in his native Czechoslovakia. As the scholar Eleanor, who refuses to loosen her grip on life even as her body is failing her, she provides the play with its emotional touchstone; as Eleanor’s daughter Esme, she offers an equally poignant consideration of a former flower child struggling to find her place in the modern world.

Ms. Redgrave breathed life into Joan Didion’s dramatization of her prize-winning book, investing it’s chilly prose with such resonance that she seemed to alter the very space around her. The words may have communicated steely intellectual control, the principle of mind of matter, but the actress was working from a place of pure feeling. The thinking was unmistakably Didion’s — but the magic was all Redgrave’s.

Mr. Gaines’ quietly shattering turn as the battle-weathered embodiment of stiff-upper-lip decency beautifully anchored Michael Grandage’s heartbreaking revival R.C. Sheriff’s decades-old play, an astonishingly clear-eyed view of the insanity of warfare and its unbearable cost. The actor was the best thing among many great things in a Tony-winning production that deserved a much longer life than it ultimately enjoyed.

In Peter Morgan’s somewhat slick recapitulation of the saga of David Frost’s legendary interviews with the disgraced former President, Mr. Langella delivered a ferocious performance which went much further toward unraveling the mysteries of Nixon than any amount of academic postulation could. Beyond giving a mere impersonation, the actor skillfully revealed harrowing psychological wreckage of a vanquished warrior who could neither comprehend nor accept his fall from grace.

If anyone thought the four-time Tony winner was in danger of coasting on her reputation for the remainder of her career, the glorious working of talent and emotion being unleashed nightly in Roundabout’s revival of this 1964 musical unequivocally and permanently put the matter to rest. Since she burst onto the Broadway scene some 13 years ago, Ms. McDonald’s talent has matured and her command of the stage has become more absolute — while her burnished soprano remains as coruscating as ever.

In Robert Falls’ searing revival of Eric Bogosian’s 1988 play, Mr. Schreiber was truly remarkable in a performance that made brilliant use of the aloof, mercurial qualities that have distinguished many of the actor’s screen appearances, yet revealed terrifying depths of pain and self-loathing as the character’s descent into hell was made physically and verbally explicit. As tormented as he is tormenting, his radio shock-jock was rendered with a searing clarity that ripped right through the fourth wall and grabbed the audience by the throat.

Some will accuse me of cheating by citing the entire cast of Tracy Letts’ brilliant, biting family drama/mystery/black comedy currently baring its fangs (and tickling the funny bone) in a sensational staging at The Imperial Theater — but singling out any one member of its 15-member cast, which functions on such a miraculous level that it makes the nonexistence of an Best Ensemble Tony Award seem criminally negligent, just wouldn’t be fair. I’ve decided I can’t do any justice to this singularly inspired piece of work — or its spectacular gallery of performances — until I’ve seen it again, so my full review will be pending. Brace yourself for an onslaught of superlatives.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Kevin Kline, Lansbury, Lists, Musicals, Stoppard, Theater Tribute, Twain, Vanessa Redgrave

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, January 17, 2008

Two trips to Yuma

My general rule is to avoid remakes of good movies, but when 3:10 to Yuma was opening last year, it was a case of a remake where I hadn't seen the original. So I waited. I finally caught up with the 1957 version and while it was good enough, I saw room for improvement and watched the 2007 edition. Now that I've seen both, I can say that each film does some things better than its cinematic sibling.

The things I liked better in Delmer Daves' 1957 3:10 to Yuma is its stark black-and-white cinematography and great use of shadows. It also happens to contain what may be the best Glenn Ford performance I've ever seen as the bad guy Ben Wade. He's smooth and though Ford was cast against type as the villain, his Wade doesn't chew the scenery in a sinister way as you might expect. He's charming and seductive and you can really see how the underlying bond of mutual respect develops between him and the rancher Dan Evans (Van Heflin).

In the 2007 version, while Russell Crowe is very good as Ben Wade, his rendering of the character actually pales a bit when compared to Ford's. On the other hand, Christian Bale's Dan Evans does develop better and shows more shadings than Heflin's model.

Daves' 1957 version also is great in its efficiency. It runs less than 90 minutes and doesn't seem to suffer for it. In contrast, director James Mangold's 2007 version, while paced very well and more than a half-hour longer, seems to skimp on some of the details that the 1957 version had the time to explore.

What 2007's version has going for it, in addition to filmmaking advances, is just the sheer Western spectacle of it all. It sacrifices the intimacy of the 1957 film, but adds the scope. Also, Ben Foster makes a much bigger impression as Wade's main henchman Charlie Prince than Richard Jaeckel did in the earlier movie.

I haven't read the Elmore Leonard story upon which both films were based, but I've heard the 2007 3:10 to Yuma adheres more closely to its source in terms of its ending.

Of course, the surprise element was lost on me in the 2007 version since I'd seen the 1957 one first, but I think the darker ending of Mangold's version actually doesn't work as well as Daves' film.

Both versions end up being good, but of the two films, I prefer the 1957 film.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, 50s, Glenn Ford, Remakes, Russell Crowe, Van Hefiin

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, January 16, 2008

Brad Renfro (1982-2008)

Another case of sad news to report from a member of young Hollywood. Brad Renfro made quite an impression as the young murder witness in The Client, holding his own against Susan Sarandon and Tommy Lee Jones.

He appeared in some good films after that, most notably Ghost World, flawed but interesting ones such as Apt Pupil, and major films such as Sleepers. He also appeared in one of Larry Clark's pseudo-kiddie porns, Bully.

Still, he never quite reached the promise he showed as a young teen, eventually getting more attention for his run-ins with the law and drug problems, problems that are apparently the cause of his untimely death at 25.

RIP Brad.

To read Matt Zoller Seitz's obit of Renfro in The New York Times, click here.

Tweet

Labels: Obituary, Susan Sarandon, Tommy Lee Jones

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

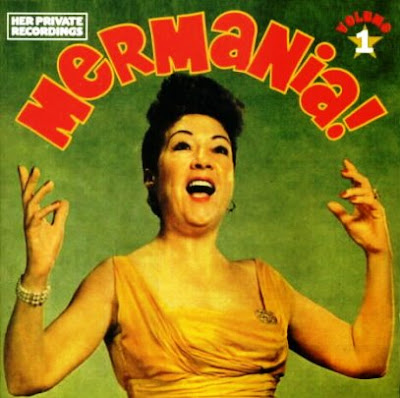

Centennial Tributes: Ethel Merman

By Josh R

Stephen Sondheim tells a great story about Ethel Merman — it draws laughs when he repeats it at speaking engagements, although it must have been hard to find much humor in the event in question when it originally occurred. For those whose knowledge of the musical theater doesn’t extend much beyond the recent film adaptations of Hairspray and Dreamgirls, a bit of background information may be required:

Along with composer Jule Styne and bookwriter Arthur Laurents, Sondheim had created a musical based on the memoirs of Gypsy Rose Lee, the celebrity stripper who had been pushed, prodded and essentially bullied into show business by her domineering mother, Rose Hovick — the kind of stage parent who could vaporize her children's rivals with as little as a withering stare. The show was conceived as a vehicle for its star; it

was Merman, in fact, who had put the kibosh on the idea of Sondheim penning the score for Gypsy in addition to its lyrics (nervous about the prospect of putting her fate in the hands of an untested composer, she insisted on the involvement of someone more experienced). Since the idea of Ethel playing a stripper was appealing to absolutely no one — she was built rather like a defensive linebacker — the part of the mother was built up into the star role. As conceived by Laurents and Sondheim, it amounted to a complex, multifaceted character study with enough psychological wrinkles built into it to keep a team of Freudian scholars intrigued for years. The real Rose had been something of a monster, with behavior ranging from moderately abusive to downright sadistic. While Lee had soft-pedaled the more repellent aspects of her mother’s character in her autobiography, the peculiar forces that drove Mama — a relentless, monolithic ambition to make her daughters into stars, the need to experience vicarious fulfillment through their success, and the barely suppressed rage of someone all too achingly aware of her own lost opportunities — were still present and accounted for.

was Merman, in fact, who had put the kibosh on the idea of Sondheim penning the score for Gypsy in addition to its lyrics (nervous about the prospect of putting her fate in the hands of an untested composer, she insisted on the involvement of someone more experienced). Since the idea of Ethel playing a stripper was appealing to absolutely no one — she was built rather like a defensive linebacker — the part of the mother was built up into the star role. As conceived by Laurents and Sondheim, it amounted to a complex, multifaceted character study with enough psychological wrinkles built into it to keep a team of Freudian scholars intrigued for years. The real Rose had been something of a monster, with behavior ranging from moderately abusive to downright sadistic. While Lee had soft-pedaled the more repellent aspects of her mother’s character in her autobiography, the peculiar forces that drove Mama — a relentless, monolithic ambition to make her daughters into stars, the need to experience vicarious fulfillment through their success, and the barely suppressed rage of someone all too achingly aware of her own lost opportunities — were still present and accounted for. Sondheim had conceived of a pivotal moment during the show-closing number “Rose’s Turn,” a climatic soliloquy in which the character’s roiling emotions came bubbling to the surface in what amounted to a mental meltdown set to music. Toward the end of the song, Rose — who is exorcising the accumulated grief, anger and disappointment of 50-odd years — gets to the point where she is reduced to stammering. Sondheim was inspired by seeing Jessica Tandy in Elia Kazan’s legendary production of A Streetcar Named Desire; as Blanche DuBois, Tandy began tripping over her words in helpless, babbling hysteria once the character’s sanity had irrevocably deteriorated. In Gypsy, Merman was to struggle with the word “Mama”. In the script, it appeared as “M-m-m-mama, M-m-m-mama.”

When it came time to rehearse the scene, Merman had one question. “Here, where it says M-m-m-mama, with the stutterin’….d’ya want that on a upbeat or a downbeat?”

Sondheim and Laurents stared at her incredulously. It was carefully explained to Merman that “the stutterin’” represented a moment of extreme emotional distress, during which the character was literally fighting to get her words out. Not only was she confronting the harsh realities of an entire existence spent observing from the sidelines, but her daughter’s ultimate rejection of her awakens dormant memories of Rose’s abandonment by her own mother.

Merman listened stone-faced, her blank expression unchanging, while her director and the lyricist patiently outlined the character’s fragile emotional state and the significance of the peculiar speech pattern. When their detailed presentation had reached its conclusion, she offered this in response:

“So didja want that on an upbeat or a downbeat?”

At that moment, Sondheim realized that while he had fought the good fight, there was little point in persevering — “Do it on an upbeat, Ethel,” he responded in weary resignation. Great entertainers are not necessarily great actors, just as the reverse is often frequently the case. For better or worse, Merman was Merman, and tutoring her on the basics of character development had about as much practical utility as there would have been in stationing Jessica Tandy downstage center to belt out “Everything’s Coming Up Roses.”

Unlike film, the stage is not a permanent record; instances of performers attaining legendary status solely for their work in the theater are few and far between. It takes

a big talent — and an even bigger personality — to make an impression so forceful that their accomplishments not only stand the test of time, but define a style of performance so completely that it becomes their legacy. It is doubtful that Merman made any kind of study of the tenets of “method” acting; if the name Stanislavski had come up in conversation, she might be forgiven for mistaking it for that of the maitre'd at The Russian Tea Room. She was not an intellectual — nor, by all accounts, was she naturally curious. Really, there is nothing to suggest that she was even remotely interested in the complexities of human behavior, at least as far as her work was concerned (she infamously made a bargain with Jerry Orbach, with whom she worked in the 1966 revival of Annie Get Your Gun, that if he wouldn’t react to her performance, she wouldn’t react to his.) What she had was a clarion voice, as pure and as powerful as an entire brass section, a killer sense of comic timing, and an intuitive understanding of what it took to hold an entire audience in the palm of her hand. People flocked to her performances with the expectation of seeing a force of nature in action; for her part, Merman saw no reason to do anything other than plant her two little feet on the edge of that stage, and let 'em have it.

a big talent — and an even bigger personality — to make an impression so forceful that their accomplishments not only stand the test of time, but define a style of performance so completely that it becomes their legacy. It is doubtful that Merman made any kind of study of the tenets of “method” acting; if the name Stanislavski had come up in conversation, she might be forgiven for mistaking it for that of the maitre'd at The Russian Tea Room. She was not an intellectual — nor, by all accounts, was she naturally curious. Really, there is nothing to suggest that she was even remotely interested in the complexities of human behavior, at least as far as her work was concerned (she infamously made a bargain with Jerry Orbach, with whom she worked in the 1966 revival of Annie Get Your Gun, that if he wouldn’t react to her performance, she wouldn’t react to his.) What she had was a clarion voice, as pure and as powerful as an entire brass section, a killer sense of comic timing, and an intuitive understanding of what it took to hold an entire audience in the palm of her hand. People flocked to her performances with the expectation of seeing a force of nature in action; for her part, Merman saw no reason to do anything other than plant her two little feet on the edge of that stage, and let 'em have it. The woman destined to become known, both affectionately and otherwise, as “The Merm,” was born Ethel Agnes Zimmerman in Astoria, Queens on Jan. 16, 1908. She worked as a secretary for the B-K-Booster Vacuum Cleaner Company before embarking on a career in vaudeville. Her Broadway debut came with a featured role in Gershwin’s 1930 Girl Crazy — while a 19-year-old named Ginger Rogers was the alleged star of the production, it was Merman who set Broadway on its ear. The high point of her performance came during her rendition of “I Got Rhythm,” in which she held a C-note for 16 earth-shattering bars. The audience went berserk, demanding multiple encores — as the proverb goes, a star was born.

Cole Porter was to become her greatest champion over the course of the next decade; all together, they collaborated on six productions, mostly hits. If it seemed like an unlikely union — the urbane sophisticate and the brass-lunged belter — Merman’s earthy forcefulness brought an element of substance to the material, which was often whimsical if not wispy in nature. Anything Goes was her first leading role, and a roaring success; audiences responded to her vocal virtuosity and her take-no-prisoners approach to putting over a number. Subsequent hits included Red, Hot and Blue and Something for the Boys, both opposite Jimmy Durante, and two genuine smashes — DuBarry Was a Lady, in which she and Bert Lahr routinely stopped the show with the comic duet “Friendship,” and Panama Hattie. In the late 1940s, she began her association with Irving Berlin, who provided the star with her two best vehicles to date. Annie Get Your Gun, a highly fictionalized account of the life and loves of legendary sharp-shooter Annie Oakley, was about as close to perfection as a musical can get; a big, jubilant glorification of a mythological Wild West that never was, and with nary a bad song in it, it fashioned Merman with what was to become her signature song, “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” Call Me Madam, which cast her in a tailor-made role as a brassy society hostess appointed ambassador to a fictional European nation, was almost as good, and won her the Tony Award. After announcing her intention to retire after Gypsy, she reprised her role in the 1966 Broadway revival of Annie Get Your Gun — referred to by theater insiders as “Granny Get Your Gun”. It didn’t matter that she was nearly 60 years old at the time; her voice remained as strong and clear as it always had, and audiences happily bought into the illusion. She closed out the storied run of Hello, Dolly!, winning a special Drama Desk Award for a role she had originally taken a pass on.

For all the success that Merman had on the stage — and not even her chief rival, Mary Martin, really came close to matching her track record — her film career never really got off the ground. It went beyond the fact that Merman was not, to put it delicately, attractive in the conventional sense or particularly photogenic. The camera doesn’t lie, and what works on a stage doesn’t necessarily translate onto the screen — film is fundamentally an actor’s medium, not an entertainer’s. In close-up, it was apparent how limited Merman’s dramatic skills were, and the extent to which she was dependent on a live audience to work her special brand of magic. Call Me Madam and a radically reworked version of Anything Goes (which had Ethel playing second banana to Bing Crosby) were the only two of her Broadway triumphs which she repeated on film. Panama Hattie and DuBarry were assigned by MGM to two non-singers, Ann Sothern and Lucille Ball, while Judy Garland was replaced on Annie Get Your Gun by Betty Hutton. In a way, this last piece of casting must have been more galling to Merman than the others. Hutton had played a secondary role in the original 1939 production of Panama Hattie — the fact that she was cited as a scene-stealer by many critics did not sit particularly well with the show’s leading lady.

The loss of her lead role in the film adaptation of Gypsy, undoubtedly the greatest triumph of her career, to Rosalind Russell was particularly painful, if arguably justified. On stage, the role may have required a great singer more than it needed a great actress, but on film, the opposite may have well proved the case (it has been suggested that the reason she lost the Tony to Mary Martin, who won for The Sound of Music, was that she didn’t quite do the role justice from an acting standpoint). What remained of Merman’s film career was eclectic, to say the least. She was stranded on a desert island with Crosby, Carole Lombard, George Burns and Gracie Allen in We’re Not Dressing, a bizarre curio of the early '30s, and had a small role in Alexander’s Ragtime Band. 1954’s There’s No Business Like Show Business was a splashy, trashy 20th Century Fox musical which seemed more interested in Marilyn Monroe than it was with Merman. Her best film performance came, rather predictably, with a one-note role in the raucous ensemble comedy It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; she played the shrill archetype of the monstrous mother-in-law for what it was worth, and was the only woman in the film to make any kind of impression. Fans of the 1980 cult classic Airplane! would have my head if I didn’t make some mention of her brief cameo as the soldier suffering from head injuries who believes himself to be Ethel Merman. Her Lieutenant Hurwitz has to be strapped down and sedated to be stopped from belting out “Everything's Coming Up Roses” — a fitting metaphor for the irrepressible energy and drive of a woman who believed, above all other things, that the show must go on.

Behind the talent, the triumphs, and the legend lies the story of a woman whose personality was just as forceful offstage as it was on. She was, by common consensus, a vulgar, overbearing figure whose consummate professionalism didn’t necessarily allow

for a spirit of generosity, or camaraderie with others. It's possible that she made more enemies than friends during her four decades as a star; her co-workers frequently described her in less than flattering terms. Sondheim referred to her as “The Talking Dog” — possibly in reference to her acting ability, but certainly a reflection of the mutual animosity that existed between them. Fernando Lamas, her leading man in the 1955 Broadway musical Happy Hunting, likened kissing her to “kissing a truck driver,” and made a point of ostentatiously wiping his mouth with the back of his hand during one performance to drive the point across; Merman filed a complaint with Actors Equity over the incident, and her co-star was forced to issue a formal apology and pay a fine. Her personal life was no less without its share of unpleasantness and intrigue. A chapter of her autobiography entitled “Ernest Borgnine,” in reference to her marriage to the Oscar-winning actor (which ended in a hasty annulment after 32 days), consisted of one blank page. As a mother, she may or may not have been a more nurturing presence than Rose Hovick; her only daughter died of a drug overdose, which the star firmly stipulated was not a suicide. There was no end to speculation surrounding her sexual orientation, although this seemed to be more a product of rumor than a reflection of genuine fact. It is known that her friendship with pulp novelist Jacqueline Susann ended with an acrimonious falling-out, although there is little hard evidence to support the claim that they were ever romantically involved. There was an element of malice involved with these rumors — while many of her detractors charged her with being “unfeminine,” she made some enemies in the gay community with what were ocassionally perceived as homophobic attitudes.

for a spirit of generosity, or camaraderie with others. It's possible that she made more enemies than friends during her four decades as a star; her co-workers frequently described her in less than flattering terms. Sondheim referred to her as “The Talking Dog” — possibly in reference to her acting ability, but certainly a reflection of the mutual animosity that existed between them. Fernando Lamas, her leading man in the 1955 Broadway musical Happy Hunting, likened kissing her to “kissing a truck driver,” and made a point of ostentatiously wiping his mouth with the back of his hand during one performance to drive the point across; Merman filed a complaint with Actors Equity over the incident, and her co-star was forced to issue a formal apology and pay a fine. Her personal life was no less without its share of unpleasantness and intrigue. A chapter of her autobiography entitled “Ernest Borgnine,” in reference to her marriage to the Oscar-winning actor (which ended in a hasty annulment after 32 days), consisted of one blank page. As a mother, she may or may not have been a more nurturing presence than Rose Hovick; her only daughter died of a drug overdose, which the star firmly stipulated was not a suicide. There was no end to speculation surrounding her sexual orientation, although this seemed to be more a product of rumor than a reflection of genuine fact. It is known that her friendship with pulp novelist Jacqueline Susann ended with an acrimonious falling-out, although there is little hard evidence to support the claim that they were ever romantically involved. There was an element of malice involved with these rumors — while many of her detractors charged her with being “unfeminine,” she made some enemies in the gay community with what were ocassionally perceived as homophobic attitudes.

Whatever people felt about her, either as an actress or an individual, there was no denying the power and the impact of what she accomplished onstage. Her performance on the original cast recording of Gypsy represents something that will never be duplicated or equaled — it is, quite simply, the greatest vocal interpretation of a role ever captured in sound. You can hear Merman’s influence to this very day — on Broadway, community and high school stages in this country and around the world. When Idina Menzel belted out “Defying Gravity” on the 2004 Tony Awards — transforming a power ballad into a vocal tour-de-force through shear physical stamina, practically muscling the song into submission — you could all but see the ghost of Ethel Merman hovering overhead, nodding in motherly approval. The truth was that Merman didn’t need to be a great actress; she was less concerned with complexity of characterization than with the act of giving a performance. That meant giving something to the audience who came for the purpose of witnessing a once-in-a-lifetime event. Merman felt the obligation to deliver such an experience very keenly, and she always gave it her all. As the song says, who could ask for anything more?

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Borgnine, Cole Porter, Garland, Ginger Rogers, Kazan, L. Ball, Lombard, Marilyn, Merman, Musicals, Orbach, Roz Russell, Sondheim, Tandy, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, January 15, 2008

Everyone looks out his own window

When Amy Ryan began her near clean sweep of the supporting actress awards for Gone Baby Gone, I was a little puzzled, since she is hardly a household name and the film itself seemed to have garnered little notice. Now that I've finally seen the film, I can see that Ryan's awards were more than justified and Ben Affleck's directing debut really hasn't been given the praise it richly deserves.

I feel ashamed of myself for not recognizing Ryan by name when she first started getting attention, since she plays Officer Beatrice Russell on the great HBO series The Wire (which I'm missing greatly, given that my evil cable company took HBO away from me and sent it to the digital ghetto). However, you won't find any trace of the hardworking single mom Beadie within the drug-addicted single mother of a kidnapping victim in Gone Baby Gone.

It's easy to see how Ryan's powerhouse work got notice, but the rest of her film and fellow actors deserve kudos as well. Adapted from the novel by Dennis Lehane, who also wrote the book Mystic River and is a writer on The Wire, Gone Baby Gone plays in some ways as if it's a sequel to Clint Eastwood's film, only Gone Baby Gone is much better.

Gone Baby Gone doesn't go on past the point where it shouldn't and, by and large, the Boston accents in Gone Baby Gone are done much better than in Mystic River.

Affleck taps his younger brother Casey as the lead here and it's not a case of nepotism run amok. Casey Affleck is quite good as Patrick Kenzie, a private investigator hired by the missing girl's aunt (Amy Madigan) (along with his girlfriend, played by Michele Monaghan) to help the police with their investigation.

Leading the investigation on the police side are too veteran detectives (Ed Harris and John Ashton) under the supervision of the police chief (Morgan Freeman), whose own child was lost long ago.

While it's hardly noteworthy to expect good work from Freeman, this is by far the best performance Harris has given in ages.

As a director, Ben Affleck moves the film along nicely, even though its complicated story would have been easy to muck up and end up confusing the viewer. Still, there is a reason Ryan has burst into the consciousness with her work here. She is superb.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Amy Ryan, B. Affleck, C. Affleck, Eastwood, HBO, Morgan Freeman, The Wire

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, January 14, 2008

Lasse comes home

When The Hoax opened in early 2007, most of the praise it received was for Richard Gere. While Gere does give one of his better performances, the surprise to me when I caught up with it on DVD is that Lasse Hallstrom directed it. In a way, the movie is a bigger comeback for Hallstrom than Gere, now that the director, though still working for Miramax, has been freed from the Weinsteins' serfdom that produced lame and worse films such as The Shipping News, Chocolat and The Cider House Rules.

While The Hoax isn't a great film, it's more indicative of the career that made Hallstrom one to watch when he was making movies such as My Life as a Dog, What's Eating Gilbert Grape and, my personal favorite, Once Around.

I wonder if Hallstrom had a great moment when he realized that he didn't have Harvey and Bob controlling his chains that looked like that moment when the Wicked Witch's henchmen realized Margaret Hamilton was now a pool of water. Back to the movie at hand.

The Hoax does a fairly good job telling the story of the writer Clifford Irving, who almost fooled the world that he had an exclusive autobiography of Howard Hughes, done with the loony tycoon's cooperation, back in the early 1970s. Gere plays Irving well, especially in the film's later passages, where you're never quite sure as a viewer what is real and what isn't.

Gere though is just one small part of a solid cast which includes Marcia Gay Harden as Irving's wife, Hope Davis as his editor and Stanley Tucci as a publishing exec.

The best part though goes to Alfred Molina as Dick Suskind, Irving's friend and eventual co-conspirator who, in some ways, reminded me of Molina's Tony-nominated role in Yasmina Reza's play Art. Molina manages to wring laughs and pathos from his role as a man unwittingly over his head but who's still able to enjoy it at times.

The Hoax does hit some speedbumps over the course of its running time, but for the most part it is enjoyable. Let's hope it's just the first stage in Lasse Hallstrom's emancipation.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, H. Weinstein, Howard Hughes, Theater, Tucci

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, January 11, 2008

The Lady is a Scamp

By Josh R

Miss Daisy Tillou is all atwitter — and when she starts fussing and chirping, she’s practically her own ornithological kingdom. Fluttering around her well-appointed drawing room like a skittish butterfly fretting over where to alight, her manner — consisting of equal parts daintiness and dizziness — represents a perfect marriage of the Victorian ideal of feminine behavior and the combustible nervous energy of a born drama queen. When people pay her compliments, she bills and coos like a puffed-up pigeon, batting her eyelashes in giddy delight. Swathed in reams of ruffles and frills, her round little face framed by mountains of ringlets which bob up and down as she moves (she looks rather like a giant dessert), she primps and flounces with the self-satisfied air of a plump turkey flaunting its plumage with the certainty of a peacock. When something occurs to offend her delicate sensibilities, her eyes widen in horror as she clasps a lace handkerchief to her ample bosom (she’s as well-upholstered as the plush Victorian furnishings that surround her) while her heart-shape mouth contracts into a taut little circle from which a high-pitched squeak of disapproval is emitted. She’s the kind of dish that once inspired poets to reel off verses extolling “the delicate flower of womanhood.”

It may come as a mild shock, then, to realize that Daisy is the creation of two men, born over a hundred years apart but working together with the conspiratorial delight of long-lost twins. The first is Mark Twain, whose previously unproduced play Is He Dead? is receiving its belated Broadway premiere at the Lyceum Theatre, in a spiffy adaptation by contemporary playwright David Ives. The second is Norbert Leo Butz, the delightfully nimble comic actor who prances, preens and pouts his way through the role of Daisy as if the concept of cross-dressing for laughs had just been invented. As to the question posed by the play’s title, the answer is a decisive no — but the coming together of Mr. Twain and Mr. Butz does represent a match made in heaven.

Twain’s play — which was only recently discovered among musty volumes in a university archive — is built around the kind of far-fetched contrivances that would never fly in an enterprise that took itself seriously. Since its author is justly renowned as one of the greatest vernacular satirists this country ever produced, there isn’t much risk of that; the surprise is how effortlessly Twain adapts his style to the creation of a work that functions as pure farce. The featherweight plot is really little more than an excuse to put a man in a dress; still, the central conceit is a clever one. Jean-Francois Millet is a struggling Parisian painter in dire financial straits; since there is no market for the work of living artists, he can’t sell a painting to save his life. That being the case, he fakes his own death and assumes the guise of his only surviving heir — a fictitious sister named Daisy, who supervises bidding wars over the work of her deceased brother and makes a killing from the proceeds. Complications naturally ensue — mostly as an excuse for the kind of comic hijinks that would embarrass the likes of Aristophanes. Unlike the recent revival of The Ritz, Is He Dead? finds ways to make the antiquated devices of farce seem fresh and inventive; the gags, which involve an empty coffin stocked with limburger cheese to keep suspicious mourners at a distance and an ingénue with detachable limbs, are so patently ridiculous that you feel like a sucker for laughing at them; but then, low comedy, when done correctly, can transform silliness into sophistication with disarming sleight-of-hand.

The lion’s share of the credit for this must be conferred upon Michael Blakemore, who directed the original production of Noises Off! and clearly understands the ins and outs of farce as well anyone who’s ever attempted the genre. His entire cast, which features nary a weak link, seems to be acting in clover. It includes Michael McGrath, John Alan Robbins and Jeremy Bobb as Millet’s motley collection of cohorts, who help him to perpetrate the ruse; veteran character actor John McMartin as a respectably dirty old man; LoveMusik’s David Pittu, who triples in three different roles with a deliciously florid array of accents; Bridget Regan as a jealous girlfriend who thinks Daisy is poaching on her turf, and winds up in drag for reasons too silly to explain; and Patricia Connolly and Marylouise Burke as an addlepated pair of landladies. Best of all are Byron Jennings, who does everything but twirl his mustache as the kind of villain who would make Basil Rathbone snicker with delight, and Jennifer Gambatese as the dewy-eyed ingénue, who looks like Olivia de Havilland in Gone With the Wind and speaks in the same soothing, honeyed tones. “Your kisses are so like Jean-Francois’,” she marvels in perplexed befuddlement, demurely oblivious to the fact that she is all but being ravished on a divan chair by her newfound best friend.

But the evening belongs, as it should, to its leading lady — or rather, its leading man. As Mr. Butz so ably demonstrated in his Tony-winning turn in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, he is a clown par excellence, with a talent for slapstick that transforms run-of-the-mill sight gags into bravura feats of comic ingenuity. If his scenes as Jean-Francois don’t give him quite as much opportunity to really let loose, once he straps on the hoopskirts, he’s pretty much unstoppable.

The critical reaction to Is He Dead?, it should be noted, has been one of mild shock. The fact that it has become, however unexpectedly, one of the most well-received new productions of the season, shouldn’t prompt too much head-scratching. Is He Dead? isn’t a work of any historic importance such as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court — but it has the same trademark wit that distinguished both the best and the least of Mark Twain’s oeuvre. It’s been many years since Mr. Twain went off to his heavenly reward — but on the stage of the Lyceum Theatre, darned if he isn’t alive and kicking.

Tweet

Labels: de Havilland, Theater, Twain

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, January 10, 2008

A Sucker for Cox

The double entendre jokes in Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story don't get any better than my title, but they share the screen with one of the more committed performances in a genre-spoofing movie. Walk Hard marks the third film in 2007's Judd Apatow triple crown, following the amusing but misogynistic Knocked Up (which he wrote and directed) and the hilarious and sweet Superbad (which he produced). Walk Hard also proved that the man who brought us The 40-Year-Old Virgin is not box-office infallible; this movie was a flop, and I'll bet it had something to do with the poster. Similar to Virgin's goofy Steve Carrell picture, Hard's poster features John C. Reilly, shirtless and goofy, paying homage to Jim Morrison. Of course, you need to be about 40 to get the reference, and most moviegoers hover around the age of 12. To them, Reilly must have looked like the poster boy for middle-age gay porn and I'm sure the title did nothing to disprove it: The Dewey Cox Story.

Perhaps the other reason why Walk Hard's box office numbers were flaccid is its marketing. I thought the film was going to be another in the seemingly endless line of bad parody movies such as Date Movie, Epic Movie and the way past its prime Scary Movie series. Walk Hard is definitely a spoof, but it's more than a series of gags thrown together haphazardly. It's closer to Blazing Saddles than Airplane!, a movie that tries to be a credible example of its target. Reilly is a good singer and an even better vocal mimic, and his performance anchors the film by becoming the one constant joke to which all the spoofy material sticks. For the most part, Walk Hard doesn't suck.

Cox comes onscreen first as a young boy who, true to musical biopic fashion, does something as a child that will haunt him until the final frame of film shoots out of the projector: He accidentally cuts his younger brother in half with a machete. The smaller Cox, who was far more brilliant than Dewey could ever be, doesn't survive, and Pa Cox (Raymond J. Barry) spends the rest of the film telling Dewey "the wrong son died." This gives Dewey a complex the film will use to explain his descent into the standard biopic excesses of sex, drugs and booze.

When Dewey is 14 (and played by the 42-year old Reilly), he runs off with his 12-year-old-girlfriend, Edith (played by 34-year-old Kristen Wiig). In order to make money, Cox waits tables at a juke joint where, according to Coming to America's Paul Bates, "people come to dance erotically." As men and women throw themselves into every sexual position imaginable while driven to frenzy by the club's soul singer, Cox wants a piece of the action on stage. He gets his big break when the club entertainment suffers several big breaks at the hands of a bookie. Dewey performs the singer's act verbatim, which, considering the Black-themed lyrics, comes off as surreal and hilarious. The people dance erotically anyway, and Cox is on the rise.

The Walk Hard of the title makes its appearance in a scene lifted from the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line. Dewey's audition goes horribly, and just when it looks like his career may be over, he channels his inner Man in Black and sings the song that will become his signature. Reilly sounds more like Johnny Cash than Joaquin Phoenix, and the song works as both parody and a country western tune. With the studio musicians (Chris Parnell, Matt Besser and Tim Meadows) behind him, Dewey hits the concert circuit and his song becomes a hit. Unfortunately, Dewey's familial guilt worsens as a result of a tragic accident occurring while his parents were dancing to his hit song, "The Wrong Son Died," Pa Cox shows up to inform him.

Once his career takes off, Cox is repeatedly seduced by temptation, which takes the guise of his bandleader Sam (Meadows). Every time Cox goes to the bathroom, he finds Sam behind the door partaking in some form of drugs. "You don't want none of this, Dewey!" Sam says, all the while making it impossible for Dewey to say no. As a result, Cox becomes an alcoholic and a drug addict, plowing through groupies both male and female while his fertile wife Edith (who must have 25 kids in this short period of Dewey's life) remains at home. While partaking in his affairs, Dewey meets his June Carter Cash clone, Darlene Madison (Jenna Fischer). This leads not only to the dissolution of his marriage to Edith, but also to a filthy song called "Let's Duet," where Dewey and Darlene sing more double entendres than can fit on a 45. "In my dreams, you're blowin' me," sings Dewey, "...some kisses..."

Like that which it mocks, Walk Hard takes us through various stages in Dewey's career, including his run-ins with famous people such as Elvis (played by Jack White of the White Stripes) and the Beatles (Paul is played by an actor you'd never expect). The swipes at the aforementioned are brutal enough (the Beatles wind up in what looks like a bad UFC match), but Apatow and director Jake Kasdan mine a small gem of genius when Cox pays tribute to Bob Dylan. Reilly's Dylan makes Cate Blanchett's imitation look like the bad Harpo Marx on drugs clone it is, and the song, "Royal Jelly," is a mishmash of nonsense that sounds a lot like some of Dylan's lousier material.

Walk Hard is full of little moments like these, ones that seem like throwaway gags but actually have some thought and construction behind them. Several times, the film reaches for a level of absurdity that is raucous and enjoyable, smoothing over some of its rougher patches. The songs are more than just jokes, and Reilly's versatility carries him from the deep rumble of Johnny Cash to the high notes of Roy Orbison (the Orbison song may be the best one in the movie). Reilly even gets to sing a disturbing yet touching song about his character's death during the credits. All the songs are first rate and perhaps we'll see Cox performing on Oscar night. (Don't we always?)

For all Walk Hard's verbal Cox jokes ("I need Cox," is one of the first lines we hear in the film), the piece de resistance has to be a completely gratuitous extended scene of male frontal nudity that somehow got past the prudes at the MPAA. As Dewey sits on the floor talking to his first wife during a hotel room orgy, his roadie Bert occupies the frame behind him. Or rather, a certain part of Bert. Reilly carries on a conversation with Bert's favorite toy, whose owner asks him for information and at one point, shares a beer with him. Reilly deserves his Golden Globe for not cracking up while carrying on a conversation with a guy while his junk is inches from his face. This scene is so popular that on NPR, one of the sleepy-voiced female hosts asked Jake Kasdan how he came up with the idea. Kasdan said he had seen an old Rolling Stones documentary where the entire band was full frontal nude for no reason. Bert's penis is far less scary than I'd imagine Keith Richards' to be. Richards' jammy was probably smoking a cigarette.

If you can only get to one Apatow movie from 2007, I suggest you get some McLovin, but if you can get to two, feast your eyes on some Cox.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Apatow, Beatles, Blanchett, Dylan, Elvis, John C. Reilly

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, January 09, 2008

A Bird in the hand

Could it be possible that Brad Bird could single-handedly save Pixar from the movie rut it's been in of late with efforts such as Cars? Ratatouille, much like Bird's The Incredibles, is another winning animated film, even if, like The Incredibles, it's a bit too long. Overall though, Ratatouille proves even more satisfying that Bird's previous film.

You would think at some point, the depth and astounding capabilities of this type of animation would stop surprising a veteran moviegoer, but Ratatouille produces many, truly astounding images.

What makes the films of Brad Bird so special is that they seem to avoid most of the formulaic pitfalls that other animated movies, be they Disney or Pixar or someone else, plunge into. If you just think about the plot of Ratatouille: a rat living in the sewers of Paris wants to abandon his family's scavenger ways and become a renowned chef. It's reminiscent of my recent talk about Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, with its elf who wants to be a dentist.

Another aspect that I loved about Ratatouille is that, though its main rat Remy (voiced by Patton Oswalt) can read and speak, he never speaks to the human characters: Only his fellow rodents can hear him.

The other great thing about Ratatouille is its talented vocal cast, including the superb Peter O'Toole as a food critic who lives to slay chefs and restaurants. Using only his voice, O'Toole's turn as Anton Ego might be a better performance than the one in Venus he was nominated for last year.

Ratatouille is just a joy and here's hoping more animators learn from Bird and the cookie-cutter plots start to fall by the wayside in other animated films.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Animation, Disney, O'Toole, Pixar

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, January 08, 2008

We know how this ends

Telling the story of well-known events can be a tricky thing, especially in a story as well known as what happened to Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl when he was abducted in Pakistan.

Angelina Jolie gives a solid performance as Pearl's wife Marianne, but A Mighty Heart seems stuck in neutral for its entire running time since we know where it's headed.

I was hoping that Michael Winterbottom's film of Marianne Pearl's book would teach me something new about the efforts to find Daniel Pearl, but it is presented in such a dry way, that it didn't do much for me.

Compare it to David Fincher's great Zodiac from last year, and as a procedural it just can't compete.

A Mighty Heart doesn't really add much on the emotional side either. Jolie's performance is mostly good (you forget that it's her for the most part), but once she gets the devastating news of Daniel's death, her shrieking scene reminded me of Grace Zabriskie's reaction to the news of Laura's death in the very first episode of Twin Peaks: It just goes on and on and you know A Mighty Heart didn't mean it to be funny on some level, but it's so over the top, you just can't help but react that way, despite the tragic truth of the story that lies beneath.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Fincher, Jolie, Twin Peaks

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, January 07, 2008

It ain't easy being Greene

Overlooked for the most part in year-end lists and awards, I caught up with Talk to Me on DVD and this fun biopic provides more evidence that not only are Don Cheadle and Chiwetel Ejiofor two of our best actors, they also are among the most chameleon-like, giving distinct performances in nearly everything they do.

Directed by Kasi Lemmons, who made the great Eve's Bayou and the interminable Caveman's Valentine, Talk to Me tells the true story of Petey Greene (Cheadle), a would-be hustler of the 1960s who develops a following as a disc jockey while he's imprisoned and schemes his way to a job at Washington radio station WOL once he gets out.

At first, the execs at the station don't know what to make of Petey, including Dewey Hughes (Ejiofor), who first meets Petey while visiting his own incarcerated brother, and the station's owner (Martin Sheen), whose tolerance is tested by this hip, profane bundle of energy that shows up on his airwaves.

Soon, Greene has a true following and Hughes recognizes that he could be so much more, quitting his job to become Petey's manager and selling him as a TV personality and a stand-up comic. While this is a true story, I wasn't familiar with it and it doesn't play like your typical biopic: the screenplay by Michael Genet and Rick Famuyiwa is funny, lively and infectious.

Cheadle and Ejiofor are both great, with Cheadle giving one of his loosest, funkiest performances ever and Ejiofor creating another vivid character, one who really undergoes more transformation than Petey does.

Also lending able support is the great Taraji P. Henson, who was robbed of an Oscar nomination for Hustle & Flow, as Petey's longtime girlfriend Vernell.

The film's weakness comes in the last act, when the focus shifts almost entirely to Hughes instead of Petey. Another problem is that for a film that spans the years 1966 to 1983, there is scant evidence of aging among the characters (or even in the settings).

When Vernell arrives late in the film to tell Dewey that a lifetime of hard living has taken its toll on Petey, she doesn't look any older and when you see Petey again, he doesn't look any worse for the wear either.