Saturday, February 27, 2010

Centennial Tributes: Joan Bennett

By Josh R

The more one sees of Joan Bennett, the more there is to like — that is, if one is willing to undertake a cineaste’s version of a search-and-recovery effort. Of the major credits discussed in this piece, only a handful are readily available for viewing — most notably three of the four films she made for Fritz Lang, the German auteur who saw past her nondescript prettiness and found something both unique and uniquely unsettling simmering beneath her unperturbed ingénue’s countenance. The roles on which her reputation was based were atypical of American cinema of the 1940s. Her best work came for European directors, in films that were decidedly European in character, while her depiction of unvarnished feminine carnality was markedly different from anything Hollywood had attempted since the pre-Code era (and it should be noted that not even Harlow or Stanwyck in their pre-Code days can match the coarseness of Scarlet Street's ‘Lazy Legs’ — but more on that to follow).

Fittingly, she wound up plying her trade more often than not on the margins of the commercial filmmaking establishment, if not altogether outside of it; there is no other leading lady of the 1940s whose resume can boast outings for Lang, Renoir and Ophuls. The films she made for the latter pair, as well as the fourth she did for Lang, remain stubbornly out of reach, consigned to the scrap heap of films deemed unworthy of release on video or DVD. If Joan Bennett’s career is one that has been sadly overlooked, with but a fraction of its treasures assigned their rightful value, the impression created by the remaining pieces testifies to an uncommonly adventurous and challenging body of work, at once both singular in character and aching for rediscovery.

In life, as on film, she proceeded to the beat of her own drummer, and her personal history was not without

its share of incident and scandal. She was the younger sister of the platinum-haired Constance Bennett, a top box office attraction of the early 1930s — it took several years and a change of hair color for Joan to emerge from her sibling’s shadow. By 16, she was married to a millionaire; by 18, a divorced single mother with a few silent film credits under her belt. She was Katharine Hepburn’s petulant pre-adolescent sister in Cukor’s adaptation of Little Women. Quite literally, there was more to Joan Bennett than this and other early roles revealed — flouncy blonde ringlets and masses of ruffles could only partially disguise the fact that she was noticeably pregnant at the time of the film’s shooting. She made a lot of costume pictures and minor melodramas and was serviceably winsome, even though at times she seemed to be struggling to suppress a yawn — romantic ingénue roles did nothing to test her, and by the end of the decade, her boredom was becoming increasingly evident.

its share of incident and scandal. She was the younger sister of the platinum-haired Constance Bennett, a top box office attraction of the early 1930s — it took several years and a change of hair color for Joan to emerge from her sibling’s shadow. By 16, she was married to a millionaire; by 18, a divorced single mother with a few silent film credits under her belt. She was Katharine Hepburn’s petulant pre-adolescent sister in Cukor’s adaptation of Little Women. Quite literally, there was more to Joan Bennett than this and other early roles revealed — flouncy blonde ringlets and masses of ruffles could only partially disguise the fact that she was noticeably pregnant at the time of the film’s shooting. She made a lot of costume pictures and minor melodramas and was serviceably winsome, even though at times she seemed to be struggling to suppress a yawn — romantic ingénue roles did nothing to test her, and by the end of the decade, her boredom was becoming increasingly evident. If she had staked her claim to semi-stardom as an innocuous, diffident little blonde, raising her naturally husky voice several octaves to a strained helium-induced squeak so as not to seem abrasive, it didn’t take Joan Bennett too long to wise up, get practical and allow caution to fall by the wayside. When her second husband left her for the raven-haired exotic Hedy Lamarr, she dispensed with both the peroxide and the inhibitions, reinventing herself as a worldly brunette with enough sexual swagger to put any other screen siren, French or otherwise, in her place. The transformation literally occurred onscreen — in the opening scenes of 1938’s Trade Winds, she is a guileless, flaxen-haired debutante draped in ermine and demurely playing Chopin on the piano. Ten minutes into the film, she has shot a man in cold blood, eluded capture by the police by driving her roadster into San Francisco Bay and resurfaced on a Shanghai steamer with a forged passport, a survivalist mentality, and hair the identical shade of her ex-husband’s new paramour. Even her makeup was reminiscent of Lamarr’s, in a manner that could hardly be chalked up to coincidence; at the time, her defiant response to being jilted, in the form of a thinly veiled swipe at her romantic rival, was regarded as one of Hollywood’s better inside jokes.

She made a brave try for the coveted role of Scarlett O’Hara, and impressed David O. Selznick enough to have briefly been considered a leading contender for the assignment. Without the backing of a major studio, her

_03.jpg) opportunities were limited; nevertheless, she landed a plum role in Lang’s 1941 noirish chase film Man Hunt, as a cockney streetwalker trying to help Walter Pidgeon evade capture by Nazi pursuers. It was a fruitful collaboration from the start; the affecting blend of toughness and vulnerability Lang was able to extract from his new muse was enough to convince Bennett that she had found her champion. With her third husband, producer Walter Wanger, she and Lang formed a production company. 1944’s The Woman in the Window played almost like the flip side of Preminger’s Laura — a variation on the same theme, but observed in a much more fatalistic vein and without any concessions to conventional sentimentality. Edward G. Robinson’s buttoned-down psychology professor becomes enamored of a portrait of Bennett he sees in a gallery window; once he encounters the model in the flesh, he is drawn into a web of murder, blackmail and treachery that sends his life into a tailspin. In contrast to Tierney’s goddess figure, Bennett’s equally enigmatic Alice Reed is both angel and demon rolled into one — temptation personified, she leads men to their doom without even having any obvious designs on doing so.

opportunities were limited; nevertheless, she landed a plum role in Lang’s 1941 noirish chase film Man Hunt, as a cockney streetwalker trying to help Walter Pidgeon evade capture by Nazi pursuers. It was a fruitful collaboration from the start; the affecting blend of toughness and vulnerability Lang was able to extract from his new muse was enough to convince Bennett that she had found her champion. With her third husband, producer Walter Wanger, she and Lang formed a production company. 1944’s The Woman in the Window played almost like the flip side of Preminger’s Laura — a variation on the same theme, but observed in a much more fatalistic vein and without any concessions to conventional sentimentality. Edward G. Robinson’s buttoned-down psychology professor becomes enamored of a portrait of Bennett he sees in a gallery window; once he encounters the model in the flesh, he is drawn into a web of murder, blackmail and treachery that sends his life into a tailspin. In contrast to Tierney’s goddess figure, Bennett’s equally enigmatic Alice Reed is both angel and demon rolled into one — temptation personified, she leads men to their doom without even having any obvious designs on doing so. The theme of temptation was revisited by Robinson, Bennett and Lang — Man, Woman and The Devil, if you will — to even more stunning effect in 1945’s Scarlet Street. Adapted from Renoir’s La Chienne (once again, the European influence at work), the film observes a masochistic weakling who falls prey to the machinations of a particularly slovenly specimen of femme fatale, of a strain that would make Double Indemnity's Phyllis

Dietrichson seem downright genteel by comparison. Indeed, Bennett’s Kitty March — nicknamed ‘Lazy Legs’ by the smarmy, abusive pimp she dotes upon — had the dubious distinction of being the most graceless, classless and altogether vulgar piece of cheap fluff ever to make an appearance in high-grade film noir (due in no small part to the influence of Scarlet Street, she wouldn’t be the last.) Lolling about her filthy walk-up in a tacky negligee, scattering candy wrappers and cigarette butts on the floor while waiting for her worthless boyfriend to materialize for rough sex and even rougher treatment, Lazy Legs is indolent to the point of inactivity; lack of ambition would be her most salient characteristic if not for her total lack of sensitivity or scruple. Stretching her whisky-soaked alto into a slatternly drawl, Bennett embellished the role with subversive flashes of humor; seductive and repellent at the same time, Lazy Legs is all the more alluring for her lack of any appealing trait beyond her beauty. It amounted to a revelatory performance, in a film not only startling for its stylistic brilliance, but for its unmistakably sadomasochistic undertones (of her unsuspecting quarry, who treats her with affection bordering on reverence, Kitty asserts that “If he were mean or vicious or if he balled me out or something, I’d like him better.”)

Dietrichson seem downright genteel by comparison. Indeed, Bennett’s Kitty March — nicknamed ‘Lazy Legs’ by the smarmy, abusive pimp she dotes upon — had the dubious distinction of being the most graceless, classless and altogether vulgar piece of cheap fluff ever to make an appearance in high-grade film noir (due in no small part to the influence of Scarlet Street, she wouldn’t be the last.) Lolling about her filthy walk-up in a tacky negligee, scattering candy wrappers and cigarette butts on the floor while waiting for her worthless boyfriend to materialize for rough sex and even rougher treatment, Lazy Legs is indolent to the point of inactivity; lack of ambition would be her most salient characteristic if not for her total lack of sensitivity or scruple. Stretching her whisky-soaked alto into a slatternly drawl, Bennett embellished the role with subversive flashes of humor; seductive and repellent at the same time, Lazy Legs is all the more alluring for her lack of any appealing trait beyond her beauty. It amounted to a revelatory performance, in a film not only startling for its stylistic brilliance, but for its unmistakably sadomasochistic undertones (of her unsuspecting quarry, who treats her with affection bordering on reverence, Kitty asserts that “If he were mean or vicious or if he balled me out or something, I’d like him better.”)If Scarlet Street marked Bennett’s crowning achievement, it wouldn’t be the actress’s last successful foray into the realm of film noir. Based on a short story by Ernest Hemingway, The Macomber Affair cast Gregory Peck as a typically Hemingway-esque great white hunter/rugged individualist hired to lead a wealthy American

couple on a Kenyan safari, only to find that he has been drawn into an elaborate game of recrimination and cruelty. An unsettling examination of passion and betrayal told against the backdrop of the African wild, Zoltan Korda’s vastly underrated film furnished its leading lady with a role of even greater emotional complexity than the Lang films had; Margaret Macomber’s cool, patrician exterior masks long-held resentments and deeply destructive impulses, neither of which can be prevented from bubbling to the surface in an isolated wilderness where the rules of civilization no longer apply. Just as the character cannot fully comprehend how she allowed herself to be trapped in a dysfunctional marriage of convenience built on lies, her efforts to avoid being poisoned by years of accommodation and denial have ended in futility. Even as the film moves to its inevitable conclusion, Margaret’s motives remain clouded in ambiguity — we’re never really sure how many of her actions are intentional, and to what extent she’s simply at the mercy of her own subconscious. It was another striking, unusual performance that deserved — and still deserves — a wider audience than it ultimately received.

couple on a Kenyan safari, only to find that he has been drawn into an elaborate game of recrimination and cruelty. An unsettling examination of passion and betrayal told against the backdrop of the African wild, Zoltan Korda’s vastly underrated film furnished its leading lady with a role of even greater emotional complexity than the Lang films had; Margaret Macomber’s cool, patrician exterior masks long-held resentments and deeply destructive impulses, neither of which can be prevented from bubbling to the surface in an isolated wilderness where the rules of civilization no longer apply. Just as the character cannot fully comprehend how she allowed herself to be trapped in a dysfunctional marriage of convenience built on lies, her efforts to avoid being poisoned by years of accommodation and denial have ended in futility. Even as the film moves to its inevitable conclusion, Margaret’s motives remain clouded in ambiguity — we’re never really sure how many of her actions are intentional, and to what extent she’s simply at the mercy of her own subconscious. It was another striking, unusual performance that deserved — and still deserves — a wider audience than it ultimately received. The Macomber Affair, like Trade Winds, is among the aforementioned films not to be found on VHS or DVD. Renoir’s The Woman on the Beach was butchered on the cutting room floor by anxious studio executives, and occasionally appears in its bastardized form on television (sadly, not soon enough for the writing of this piece). Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door is cited by film historians as one of her better vehicles; given Bennett’s track record with Lang, such assertions can be readily believed, even if circumstance requires they must be accepted on faith.

The postwar era marked a shift in values — once the boys were back and Ike was in, many of the no-good dames of the 1940s were expected to shove their trashy heels to the back of the closet and forsake their wayward ways. Implausible as it may seem, a scant five years after Lazy Legs had vamped her way to infamy,

Bennett found herself at the side of Spencer Tracy, embodying the values of bland suburban matronhood and fussing over Elizabeth Taylor’s trousseau in Father of the Bride. The film was profitable enough to merit a sequel, Father’s Little Dividend — to say that Bennett was wasted in these films would qualify as an understatement. After that flush of mainstream success, her career fell by the wayside; once the temptress had been domesticated, no one thought to inquire just what kind of a wild life Ellie had led prior to becoming Mrs. Stanley Banks — worse still, no one seemed to be particularly interested. In real life, the reverse may have proved to be the case; in 1951, Walter Wanger shot his wife’s agent, asserting that the latter “was breaking up my home”, and was briefly imprisoned. The ensuing scandal did his wife’s career no favors, and she worked sparingly in films for the remainder of career. She found renewed life on television in the gothic horror soap opera Dark Shadows, earning an Emmy nomination for her efforts, and with a supporting role in Dario Argento's cult classic Suspiria.

Bennett found herself at the side of Spencer Tracy, embodying the values of bland suburban matronhood and fussing over Elizabeth Taylor’s trousseau in Father of the Bride. The film was profitable enough to merit a sequel, Father’s Little Dividend — to say that Bennett was wasted in these films would qualify as an understatement. After that flush of mainstream success, her career fell by the wayside; once the temptress had been domesticated, no one thought to inquire just what kind of a wild life Ellie had led prior to becoming Mrs. Stanley Banks — worse still, no one seemed to be particularly interested. In real life, the reverse may have proved to be the case; in 1951, Walter Wanger shot his wife’s agent, asserting that the latter “was breaking up my home”, and was briefly imprisoned. The ensuing scandal did his wife’s career no favors, and she worked sparingly in films for the remainder of career. She found renewed life on television in the gothic horror soap opera Dark Shadows, earning an Emmy nomination for her efforts, and with a supporting role in Dario Argento's cult classic Suspiria. In a day and age when film buffs and writers speak at length about glory deferred — Jeff Bridges is frequently cited as one of our most underrated actors — a case can be made for Joan Bennett as one of the more egregiously overlooked talents in the annals of film history. Academy Award nominations are often judged to be the barometer of career success; Bridges, it must be said, has been honored on five such occasions (and if people are still referring to him as underrated now, I suspect they won’t be after next Sunday night). Joan Bennett never received an Oscar nomination; but then, her best film work was ahead of its time. Sadder still is the realization that time has yet to catch up with her. Had she received a nomination or two, it’s tempting to wonder whether or not she’d enjoy a higher profile than she does now. ‘Lazy Legs’ stands as one of the more daring film noir performances of its era; her other efforts testify to the fact that she was more than a one-hit wonder. With or without the recognition she deserved, it must be asserted that she made an indelible mark on the American cinema. For whatever reason, The American Cinema has yet to recognize her true worth.

Tweet

Labels: Cukor, Edward G., G. Tierney, Gregory Peck, Harlow, Hemingway, Jeff Bridges, Joan Bennett, K. Hepburn, Lang, Liz, Ophuls, Preminger, Renoir, Selznick, Stanwyck, Television, Tracy

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, February 26, 2010

The Solid Guy

By Jonathan Pacheco

You knew a guy back in high school, a pleasant, smart, occasionally clever guy. Not a brainiac, not a clown, not a jerk, not a socialite, just a solid guy. He possessed few faults (as far as you cared), and you never thought of him as "average"; he was more interesting than that. But these days, you really don't remember him unless someone else brings him up, and you say, "Oh yeah, that guy."

A solid, decent guy typically doesn't claim a lot of real estate from your memory landscape. And why is that? Well...because his intelligence didn't frighten you like the kid with the 4.5 GPA. Because you two didn't have an ongoing comic strip featuring characters like "Super Cow" and "The Snoogan." Because he never soiled a friend's pillow with his precious bodily fluids at summer camp. You meet a lot of people through the years, and as time goes by, this solid guy just doesn't jump out at you nearly as much as some of the more memorable or extreme people. Isn't that a shame?

Roman Polanski's The Ghost Writer is that solid guy, and finding something wrong with the film is proving difficult for me. Its story of an author (Ewan McGregor) penning the memoirs of a former British prime minister (Pierce Brosnan) engages and entertains, slowly spinning us and our protagonist through a political vortex. The acting ensemble shows few cracks and the muted cinematography pleasantly understates without resorting to "easy shots." It's a solid film.

And yet...there just isn't enough to set it apart. I applaud a film that resists the urge to "spice up" subtle roles, that avoids unnecessarily active camerawork, that refrains from shoehorning misfit car chases. These choices aren't unadventurous, they're intelligent. But if The Ghost Writer had hoped to claim greatness, it should've taken more risks, particularly with its script. The plausible story (in movie terms) doesn't take itself too seriously (something I love), but as it unfolds, it opts for security over potential. I wouldn't call the developments and twists clichéd, but they're only a notch or two above that, which perks-up but doesn't truly refresh a mostly familiar plot.

That's a bummer, because The Ghost Writer has got a lot of positives. It visually employs hues of blues, sandy beiges, and sterile metallics more creatively than the typical political thriller (reminding me a little of Tom Tykwer's work in The International), and it showcases charismatic performances from McGregor — loose, funny, and never in the way — as well as Olivia Williams — sexy and comfortable as the former prime minister's loyal but secretive wife. Really, I'm aching to hail The Ghost Writer as a great film; it's not. Worse, I sound like I'm bashing the film when I say that.

After finishing a draft of this review, I read Roger Ebert's thoughts on the film. We both praise it for pretty much the same things: strong acting, entertaining storytelling, filmmaking built on "craft, not gimmicks," as Roger puts it. Yet he gives The Ghost Writer his highest rating — four stars — and I'm struggling not to call Polanski's film "forgettable." The difference, as I've written in the past, is that someone such as Ebert feels that the height of filmmaking is not making mistakes, and while I respect that opinion, it seems a little soft and unchallenging for my own personal definition. A film that makes no mistakes is usually a film that plays things safely. The Ghost Writer, when it really counts, does just that.

You see, it is a strong film, just not strong enough to distance itself from the pack, dooming it to live on as "the solid guy." It's that pleasant film that you watch, enjoy, and forget about in a few weeks. Months — perhaps years — later, a friend of yours spots the DVD in the bargain bin. "Hey, you seen this one? Ghost Writer?"

"Which one?"

He holds up the case for you. "Here. Look."

"Oh yeah, that movie."

Tweet

Labels: 10s, Ebert, Ewan McGregor, Polanski

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

This is a love story

By Edward Copeland

Not the boy-meets-girl story told in (500) Days of Summer: The film is upfront about that. This is a love story between a man and a movie. I first saw (500) Days of Summer during the days when this blog was on hiatus and I didn't want to write about it from memory. Besides, I wanted to watch it again. Now, I have and I'm ready to share my affection for the film with the reading world.

One regret that I've always had, one I imagine that is common to all movie lovers, is that same regret Burgess Meredith's character's had in the Twilight Zone episode "Time Enough at Last:" There just isn't enough time for him to read all the books that he wants to and even a nuclear holocaust won't help. For me, it's worse. Not only am I losing the battle with time to see all the movies ever made that I want to see, they keep making

more of them. Pile on top of that that I'm a voracious reader as well, so when am I going to find time to read all those books? It's a good thing there are very few series on TV I pay attention to and they usually have short seasons and long hiatuses. Mortality can prove to be a definite hindrance and I can just imagine how difficult it must be for people who share my affliction and aren't bedridden and actually have to hold down jobs to work for a living. Granted, the movie industry has done their part by producing so much garbage that my radar usually detects titles not worth my time. However, what makes things even more complicated is that when the great movies get made, be they classics such as Rules of the Game or Casablanca, I want to revisit them, eating up more of my life. While I'm not remotely prepared to place (500) Days of Summer close to that rarefied company, after seeing it a second time, I know this is one of those films that I will want to see many more times in what remains of my existence.

more of them. Pile on top of that that I'm a voracious reader as well, so when am I going to find time to read all those books? It's a good thing there are very few series on TV I pay attention to and they usually have short seasons and long hiatuses. Mortality can prove to be a definite hindrance and I can just imagine how difficult it must be for people who share my affliction and aren't bedridden and actually have to hold down jobs to work for a living. Granted, the movie industry has done their part by producing so much garbage that my radar usually detects titles not worth my time. However, what makes things even more complicated is that when the great movies get made, be they classics such as Rules of the Game or Casablanca, I want to revisit them, eating up more of my life. While I'm not remotely prepared to place (500) Days of Summer close to that rarefied company, after seeing it a second time, I know this is one of those films that I will want to see many more times in what remains of my existence.When (500) Days of Summer first opened, I feared it might be too gimmicky (those unnecessary parentheses may have helped that impression along). As with nearly every film, I didn't get to see the film until it hit DVD

and I was bowled over. What people who disliked the film might dismiss as gimmicks played as perfect grace notes to me, from the funny opening assurance that any resemblance to real people was purely coincidental to the great narration that would recur throughout the film by Richard McGonagle. His opening set the stage perfectly and cast the film's spell over me as he explained the back story of Tom Hansen (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), who thanks to an early exposure to sad British pop music and a misreading of The Graduate, believed that the search for love always leads to The One. Though he set out to be an architect, Tom works as a greeting card writer and it is there where he meets Summer Finn (Zooey Deschanel), the woman he knows is his soulmate. They soon begin dating (what else do you call spending lots of time together and having sex?) despite Summer being crystal clear from the outset that she just wants to be friends because she believes love is a fantasy and relationships are messy. Tom hears what she is saying, but because he loves everything about her, he's sure he has the power to change her mind.

and I was bowled over. What people who disliked the film might dismiss as gimmicks played as perfect grace notes to me, from the funny opening assurance that any resemblance to real people was purely coincidental to the great narration that would recur throughout the film by Richard McGonagle. His opening set the stage perfectly and cast the film's spell over me as he explained the back story of Tom Hansen (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), who thanks to an early exposure to sad British pop music and a misreading of The Graduate, believed that the search for love always leads to The One. Though he set out to be an architect, Tom works as a greeting card writer and it is there where he meets Summer Finn (Zooey Deschanel), the woman he knows is his soulmate. They soon begin dating (what else do you call spending lots of time together and having sex?) despite Summer being crystal clear from the outset that she just wants to be friends because she believes love is a fantasy and relationships are messy. Tom hears what she is saying, but because he loves everything about her, he's sure he has the power to change her mind.My curiosity naturally wonders how couples who saw this movie together viewed it because to me, despite it basically being a comedy, albeit one with touching moments, it seems to be one destined to be a conversation

starter and films such as that are far too rare these days. While Summer never misleads Tom about her feelings, she certainly acts as if she's his girlfriend and I've never heard of a best friendship that functions the way she thinks hers does with Tom, so it's understandable when things come to their end why Tom becomes so confused and devastated. Then again, I'm a guy. I wonder if a woman watching the film would have a completely different reaction. One reason I think (500) Days of Summer affected me so is that, though these characters are much younger than me, I feel as if I know these people, as if I grew up with them. Director Marc Webb is five years younger than me and I don't know how old screenwriters Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber are, but they look a lot younger than me. Of the many laughs I had watching the movie, one of the biggest was when Summer tells Tom that lately they've basically been acting like Sid and Nancy. He objects, saying Sid Vicious stabbed Nancy Spungen. "No, I'm Sid Vicious," Summer replies. For someone my age, whose high school years included Alex Cox's Sid & Nancy as an extremely pivotal film, it's a spot-on gutbuster. In an odd way, it reminds me of Heathers. Not in terms of plot obviously, but that it's one of those films that I could imagine myself making, not better mind you, just the type of movie that could spring from my mind.

starter and films such as that are far too rare these days. While Summer never misleads Tom about her feelings, she certainly acts as if she's his girlfriend and I've never heard of a best friendship that functions the way she thinks hers does with Tom, so it's understandable when things come to their end why Tom becomes so confused and devastated. Then again, I'm a guy. I wonder if a woman watching the film would have a completely different reaction. One reason I think (500) Days of Summer affected me so is that, though these characters are much younger than me, I feel as if I know these people, as if I grew up with them. Director Marc Webb is five years younger than me and I don't know how old screenwriters Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber are, but they look a lot younger than me. Of the many laughs I had watching the movie, one of the biggest was when Summer tells Tom that lately they've basically been acting like Sid and Nancy. He objects, saying Sid Vicious stabbed Nancy Spungen. "No, I'm Sid Vicious," Summer replies. For someone my age, whose high school years included Alex Cox's Sid & Nancy as an extremely pivotal film, it's a spot-on gutbuster. In an odd way, it reminds me of Heathers. Not in terms of plot obviously, but that it's one of those films that I could imagine myself making, not better mind you, just the type of movie that could spring from my mind.Webb's direction smoothly handles the endless time shifts and bits of whimsy in Neustadter and Weber's screenplay. So many movies play with chronology, especially in the wake of Tarantino, that many times it can play as a cliche, but the way (500) Days uses it, it not only seems fresh but necessary. At the very beginning,

we are informed that while it is a boy-meets-girl story, it is not a love story, so we know that by the film's end, Tom and Summer will not be a couple. If it followed standard, chronological order, this would be a bit of a bore as well as a downer. What also makes the technique great here is why it's so good in a masterpiece such as Citizen Kane: you are never certain which scene comes next so each viewing seems fresh. In fact, though some may classify the film as an unusual romantic comedy, it's more akin to a crime procedural with Tom going back over the clues in his head to try to solve the mystery of how what were the happiest moments of his life turned into the lowest moments. His really smart younger sister Rachel (Chloe Grace Moretz) more often than not turns out to be Tom's voice of reason and she's the one who gets him to think back to the times that weren't good in order to realize that Summer wasn't The One she thought he was. It's not just the dialogue that sparkles. The script's ingenuity extends to the aforementioned narration (He describes the unusual effects Summer's presence always has had including a 212% spike in sales when she worked at a particular ice cream parlor and an average 18.2 doubletakes on each commute she took to and from work) and a scene where a despondent Tom imagines himself and Summer in scenes from classic foreign films. It's really in great contrast to the similar scene in Precious, because you are supposed to laugh in (500) Days whereas in Precious, the scene is just ridiculous and terribly out of place. Of course, the film's most unexpected moment, which could have easily fallen into disaster, is Tom's post-coital exuberance which begins with him looking at his reflection in a car window and seeing Harrison Ford as Han Solo grinning back before it turns into a full-fledged musical number (to Hall & Oates no less) throughout the park. It's glorious, especially its denouement which starts with him entering an elevator in joy and exiting on another day in the doldrums.

we are informed that while it is a boy-meets-girl story, it is not a love story, so we know that by the film's end, Tom and Summer will not be a couple. If it followed standard, chronological order, this would be a bit of a bore as well as a downer. What also makes the technique great here is why it's so good in a masterpiece such as Citizen Kane: you are never certain which scene comes next so each viewing seems fresh. In fact, though some may classify the film as an unusual romantic comedy, it's more akin to a crime procedural with Tom going back over the clues in his head to try to solve the mystery of how what were the happiest moments of his life turned into the lowest moments. His really smart younger sister Rachel (Chloe Grace Moretz) more often than not turns out to be Tom's voice of reason and she's the one who gets him to think back to the times that weren't good in order to realize that Summer wasn't The One she thought he was. It's not just the dialogue that sparkles. The script's ingenuity extends to the aforementioned narration (He describes the unusual effects Summer's presence always has had including a 212% spike in sales when she worked at a particular ice cream parlor and an average 18.2 doubletakes on each commute she took to and from work) and a scene where a despondent Tom imagines himself and Summer in scenes from classic foreign films. It's really in great contrast to the similar scene in Precious, because you are supposed to laugh in (500) Days whereas in Precious, the scene is just ridiculous and terribly out of place. Of course, the film's most unexpected moment, which could have easily fallen into disaster, is Tom's post-coital exuberance which begins with him looking at his reflection in a car window and seeing Harrison Ford as Han Solo grinning back before it turns into a full-fledged musical number (to Hall & Oates no less) throughout the park. It's glorious, especially its denouement which starts with him entering an elevator in joy and exiting on another day in the doldrums.

Even with the great writing and great direction, this movie wouldn't work if it didn't have a cast up to the task and (500) Days does. Few actors who began working as children have developed into such dependable

adult actors as Gordon-Levitt has (and what range). His dramatic turns in films such as Brick, Mysterious Skin and most especially The Lookout really show no preparation for the range here, mostly light, but more complicated than that. (This isn't 3rd Rock From the Sun-level comedy either.) The look he gets when Summer kisses Tom by the copy machine unexpectedly is a thing of wonder. Deschanel has the tougher assignment because she has to play multiple impressions of Summer. She has to be the charming girl that Tom falls for and the cold woman who thinks it's OK to lead him on because she established to him that they aren't a couple from the outset and she accomplishes all this without ever earning the viewer's scorn. While she's been fine in some good films before, (500) Days is by far her best work on the big screen. I could go on forever talking about (500) Days of Summer, but I don't want to give all its wonderfulness away. In the end, this is less a film about love than about the role of fate in all of our lives and really that's what happens with all movies as well. If all the creative forces hadn't aligned in the right way, the world would have been deprived of (500) Days of Summer and that would be a much sadder world indeed.

adult actors as Gordon-Levitt has (and what range). His dramatic turns in films such as Brick, Mysterious Skin and most especially The Lookout really show no preparation for the range here, mostly light, but more complicated than that. (This isn't 3rd Rock From the Sun-level comedy either.) The look he gets when Summer kisses Tom by the copy machine unexpectedly is a thing of wonder. Deschanel has the tougher assignment because she has to play multiple impressions of Summer. She has to be the charming girl that Tom falls for and the cold woman who thinks it's OK to lead him on because she established to him that they aren't a couple from the outset and she accomplishes all this without ever earning the viewer's scorn. While she's been fine in some good films before, (500) Days is by far her best work on the big screen. I could go on forever talking about (500) Days of Summer, but I don't want to give all its wonderfulness away. In the end, this is less a film about love than about the role of fate in all of our lives and really that's what happens with all movies as well. If all the creative forces hadn't aligned in the right way, the world would have been deprived of (500) Days of Summer and that would be a much sadder world indeed.Tweet

Labels: 00s, Burgess Meredith, Gordon-Levitt, Harrison Ford, Tarantino

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, February 22, 2010

The Song remains the same

By Edward Copeland

Living in the United States, we're destined to get a skewed view of any other country's film output. You have to assume that primarily the best of their product and the work of their most prestigious filmmakers are more likely to land on our shores and they probably produce mediocre and awful movies just the way we do here. However, I have to say that I don't think I have ever seen a bad Iranian film. Certainly, the quality of the films vary in degrees and The Song of Sparrows falls toward the lower end of the spectrum, but it's another example of my experience that watching an Iranian film always ends up being worthwhile.

The Song of Sparrows was co-written and directed by Majid Majidi, who also made the great films Children of Heaven, Baran and The Color of Paradise. It isn't as strong as those previous works, but it plays on a lighter level thanks to a delightful lead performance by Reza Najie.

Najie plays Karim, an ostrich rancher, whose life takes many unexpected turns when his daughter's hearing aid falls into a water storage tank, rendering it useless. Also, an ostrich escapes, causing him to lose his job. While it may not be apparent to all viewers, The Song of Sparrows actually tells a spiritual Islamic fable. As Karim heads to Tehran and stumbles accidentally into odd jobs that he hopes will fund a new hearing aid for his daughter, he also faces the temptations of the modern world.

Still, the film is not remotely preachy and it almost plays like a light comedy. I didn't even recognize its spiritual underpinnings until the story got to the third act and even then it doesn't beat you over the head with them. The key to tying all the disparate elements together (the differing tones, the fable elements, the spirituality) is Najie, a man gifted with a wonderfully expressive face.

As the country of Iran goes through its problems with anti-government protesters being beaten and killed in the streets while its theocratic bullies at the top use their militaristic thugs to keep themselves in power, it's truly an amazing thing that the country can produce such great films and that the rest of the world can see them. When we see scenes of a bustling Tehran, it doesn't seem as if it's propaganda.

With filmmaking this good coming out of there, protesters putting their lives on the line for a principle and scenes of daily life as this film shows, perhaps there is hope that the evil that strangles the country will be toppled. Let's hope it is soon.

Tweet

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, February 19, 2010

You can't handle the truth

By Edward Copeland

One of the first times I held the infant daughter of a good friend of mine, I commented how sweet she was and how she wasn't even old enough to have told her first lie. Ricky Gervais' The Invention of Lying exists in an imaginary world of that sort of universe, where everyone always tells the truth, no matter how harsh or cruel. In fact, no one even know what a lie is. They couldn't define the word if they tried. It makes for a very funny premise and a mostly very funny movie, one that is sure to piss off the extremely religious among us.

Gervais not only stars, he co-wrote and co-directed the comedy with Matthew Robinson. Gervais plays Mark Bellison, a screenwriter for Lecture Films. Since only truth exists in this universe, the only movies that are made are recounting of historical events and Bellison's assignments are stuck in the 13th century and the black plague just isn't producing boffo box office, so the poor schlub is about to lose his job. He's honest about it on his first (and what she tells him, will be their, because of his weight, only) date with Anna (Jennifer Garner), a woman even the waiter informs him is out of his league.

The all-truth universe proves very funny, right down to many sight gags. The nursing home where Mark's mother resides is called "A Sad Place for Hopeless Old People." It truly makes a case that absolute truth isn't all it's cracked up to be. Then again, living in a world where there are more lies going on than truthtelling (and bad attempts at lying at that), it's really hard to judge. Still, it's funny to watch as everyone constantly speaks the absolute truth, not to be cruel, but because they simply have no other choice. I marvel at how he got Coke to agree to its mock ad, though I think the film missed an opportunity to portray what politics looks like in this kind of universe.

Mark, out of a job and unlucky in love, also faces eviction from his apartment, so he goes to his bank to close his account to have enough money to rent a truck to clear out his apartment. Unfortunately, the bank's system is down and they can't access his information. At that moment, something happens in Mark's brain that has never occurred in another human's brain before: When the teller asks how much he needs from his account, he lies. Since everyone assumes every word uttered by every person is the truth, no questions are asked and she gives him the excess cash, and Mark discovers he may well be the most powerful person in the world.

First, he uses his newfound ability to lie to acquire money at a casino (even though the odds are rigged toward the house, they are blatantly honest about it — they can't help it). Mark then realizes that he can write screenplays that aren't true as well and his universe's first fictional feature is born. However, the real phenomenon occurs by accident.

As his mother (Fionnula Flanagan) lies dying after a series of severe heart attacks, she expresses fright at disappearing into nothingness. Seeking to comfort her, Mark manufactures an afterlife, a wonderful place where she will find eternal happiness and be reunited with her late husband an all her old friends. Unfortunately, the doctor and some nurses overhear this and, as all people in this world do, assume every word uttered is the absolute truth and the Mark knows something no one else has ever revealed. By accident, Mark has invented religion.

As crowds gather outside the hospital to demand answers, Mark holes up inside with Anna and his best friend Greg (Louis C.K.) to devise the rules for his lie, all involving the "invisible man in the sky." Gervais, an open atheist, has reached the point of the movie that will piss the pious off. For me however, it is very funny. In fact, as time goes on, I think that The Invention of Lying is the type of film whose reputation will grow as more discover it.

The only problem with the film is that it begins to peter out in the third act as it concentrates on Ben's desire to win Anna's heart and convince her that there is more to love and marriage than just picking the right genetic match (personified by an unctuous rival screenwriter played by Rob Lowe). Ben begins to feel guilty about some of his lies and chooses not to at times when he could, because he doesn't want to trick Anna into wanting him, he wants her to make the right decision.

Still, most of The Invention of Lying is very funny and it is populated by many funny cameos by actors in small parts. I almost wish that Gervais had went a little stronger with his points, but it seems as if he shies away from truly shoving the made-up aspect of religion in his audience's face and as a result, comes up with a weaker ending.

Tweet

Labels: 00s

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, February 18, 2010

A stitch in time

By Edward Copeland

Some movies can give critics the equivalent of writer's block: We really can't find much to say. That's the way I felt after watching Jane Campion's Bright Star. It is a well-made movie, if not a particularly compelling one, and it does contain a strong lead performance from Abbie Cornish, but its failure to engage me on pretty much any level, leaves me at a loss for much to say about it. It's not that it's a particularly bad film or even a particularly mediocre one, it's just comatose.

Aside from The Piano, I've never warmed to most of Campion's work, despite her recent declaration that she "doesn't make shit." I'm not implying that some of Campion's films should be tossed into an excrement pile, but the vast majority of them that I've seen have simply bored me and Bright Star falls into that realm.

Bright Star tells the story of the doomed romance between young Fanny Brawne (the great Cornish) and the legendary 19th-century poet John Keats (Ben Whishaw), though his acclaim didn't come until long after his early death at the age of 25.

I think the real problem with Bright Star may well be the casting of Keats. Paul Schneider portrays Keats' friend, the ever-suspicious Charles Armitage Brown, and he gives a rich, lively performance that puts Whishaw's work to shame. I realize that Keats was a sickly man, but that doesn't mean that the actor playing him should disappear into the scenery. As a result, the romance between Fanny and John almost seems one sided because Cornish gives such a full-bodied performance and Whishaw is so wan.

Still, the scenery that Whishaw disappears into is quite stunning thanks to the work of cinematographer Greig Fraiser and costume designer Janet Patterson, so at least you'll have pretty things to look at should your mind begin to wander as mine did.

Tweet

Labels: 00s

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

More of this is bad than you would believe

By Edward Copeland

When a strange movie starts out promisingly but soon starts plummeting further and further into an abyss of awfulness, you get that feeling of plunging off a cliff yourself. The Men Who Stare at Goats seems to set out to be a wild, absurdist comedy supposedly inspired by true events. Its talented (and wasted) cast is led by Ewan McGregor and part of the story concerns a top secret Army program named for Jedis after the Star Wars films. To give you an indication of how truly bad this film is, seeing McGregor and hearing Jedi made me wish that I instead were watching The Phantom Menace — even with Jar-Jar Binks. Yes, it's that bad.

Co-starring with McGregor are George Clooney and Jeff Bridges, the two leading contenders in this year's Oscar race for best actor. They better hope no Academy members found time to watch this stinker of a screener or their deserving performances in Up in the Air and Crazy Heart respectively might get reflexively punished. Clooney even helped produce this mess so he might have even more to lose.

McGregor plays Bob Wilton, a newspaper reporter whose wife leaves him for his editor. After interviewing a man (Stephen Root) who tells of a secret Army project he was a part of that investigated the use of psychic powers in warfare. Aimless and depressed, Bob does the natural thing for a reporter from a midsize paper at the beginning of the Iraq War: He finances his own way to Kuwait to try to find a story to convince his estranged wife that he's worthwhile.

While stuck in a Kuwaiti hotel covering some sort of contractor convention, he stumbles upon Lyn Cassady (Clooney), one of the most gifted of the secret program who feels some connection to Bob and fills him in on the program's past and takes him into Iraq. At least I think he's the one who tells Bob the story. Bob narrates the entire tale in all-knowing voiceover, but it's really unclear how he happened upon most of the details.

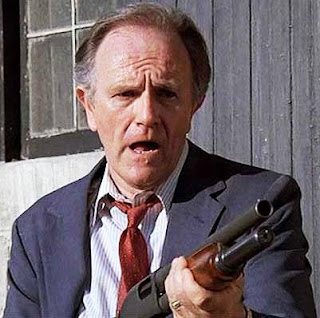

As I lie here trying to recount the events of this turd, it seems like such a waste of time to even try to describe the plot. This could have worked if the right talents had written and directed it, creating a sort of Fear and Loathing in Ramadi, but the longer it goes on, the stupider and more pointless it becomes. Kevin Spacey shows up as some kind of writer, I think, who gets into the Army project and hates everyone.

Bridges, bless his heart, manages to give the best performance as a trippy leader of the unit who fell out of a helicopter in Vietnam and came up with the idea for the project, which he hoped would actually lead to warfare that really was peace, but Spacey is the villain (again, I think) who wants to keep things lethal. Eventually, it returns in the form of private contractors working for the U.S. in Iraq.

The movie's sheer badness reaches such a level that I have no qualms about revealing spoilers about the climax: It involves LSD slipped into eggs and the water supply while Clooney and Bridges escape and no, I'm not sure what the hell that means.

The Men Who Stare at Goats was directed by Grant Heslov, who co-wrote Good Night, and Good Luck. with Clooney. Peter Straughan wrote the adaptation of Jon Ronson's book. Neither made a positive career move.

As I suffered through the 90 minutes of this nonsense, watching George Clooney running around sand dunes, I did turn meditative as some of the operatives did and developed my own mantra to help me cope: "Why aren't I watching Three Kings? Why aren't I watching Three Kings? Why aren't I watching Three Kings..."

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Ewan McGregor, George Clooney, Jeff Bridges, Spacey, Star Wars

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, February 15, 2010

If it's really funny, I'll laugh

By Edward Copeland

As a writer-director, Albert Brooks had a period where he was mistakenly labeled the West Coast Woody Allen, but his output was never that prolific (which probably saved him from falling into the ruts Allen eventually did). However, he has been a reliable character actor and when he was regularly making his own movies, he made three good ones and three absolutely great ones, the second of which, Lost in America, turns 25 today.

Brooks and co-writer Monica Johnson turned a satiric eye on the yuppie craze sweeping middle-age America in the early 1980s as Brooks and Julie Hagerty starred as David and Linda Howard, two L.A. residents about to move to a new custom-built $450,000 home on the strength of the promotion to senior vice president David expects to receive at his powerful ad agency. Linda also works, a slightly less prestigious job as a personnel manager at a department store. David is so certain of the prize soon within his grasp he's pricing a new Mercedes with Hans on the phone at the auto dealership for a model that comes with everything except leather. (It has Mercedes leather, which Hans describes as "thick vinyl." Brooks plays both sides of the phone call.) His confidence is emphasized further with some wonderful tracking shots through the halls of the ad agency.

It's a slightly more reckless side of David than we see in the opening scene when he and Linda are in bed listening to Larry King interview Rex Reed (that's where this post's title comes from), where David second-guesses having the moving company do their packing. Linda believes they've become a "little too responsible" but David counters that he's insane and responsible and that's a potent combination. A combination that causes problem when instead of getting that expected promotion, he gets what his boss considers better news: the agency has landed the Ford account and wants him to move to New York to help the man assigned to handle it. David goes ballistic, at first thinking it's a joke, then getting angry and hurling epithets before being escorted out of the building by security declaring, "I've seen the future and it's a bald-headed man from New York!" When I originally saw this movie in 1985, I was puzzled by its R rating. There is no graphic violence or nudity and I didn't recall major profanity, but rewatching this scene, there are two "fuck you"'s, one more than would be allowed for a PG-13, new to the MPAA the year before. It's still a dumb rating for the film.

At Linda's workplace, she's depressed already. Picking out tile that morning for the new house, she feels that her life is in stasis and that nothing ever changes. She doesn't like anything anymore and she already knows what the next 10 years will be like with or without David's promotion. When David bursts in, urging her to quit right then so the two of them can drop out of the work-a-day world of society and "touch Indians," her mind is more open to the idea than it might be on a different day.

So launches the yuppie version of Easy Rider and one of the funniest comedies of the 1980s, only when "Born to Be Wild" plays on the soundtrack, the camera pans along a Winnebago instead of motorcycles. ("It's better than the new house and it has wheels too," David insists.") Their plan begins by liquidating everything they own, losing what little they've put into the new house and taking he healthy profit they are making by selling their current home. Even after the $45,000 cost of the RV, they have nearly $150,000 in cash (the nest egg) which they believe is more than enough to live on simply as they drop out and get back to the baby boomer ideals they once held so dear back in college. To mark their new start, David and Linda decide there could be no better way than to renew their wedding vows, which they plan to do in a cheesy Las Vegas chapel.

Once they arrive though, Linda cites fatigue and hedges on David's plan to camp out under the stars, suggesting they wed in the morning and have one last night of decadence: Checking into a casino's bridal suite, bathing

together in one of those big tubs and ordering room service. Unfortunately, bribery is not a skill that comes easily to David and what they get at the now-defunct Desert Inn is the Junior Bridal Suite, which contains two heart-shaped beds you can't push together and a shower. "If Liberace had children, this would be their bedroom" is David's assessment. As someone who actually stayed at the Desert Inn in the mid-1980s and went back to Vegas later, the film serves as a bit of a time capsule as to what a stark difference the Vegas Strip of today looks like compared to the strip of the 1980s. David awakes around 2:30 in the morning to discover that Linda isn't to be found. He wanders in a stupor to the casino floor to find her hovering over the roulette table chanting, "Twenty-two, twenty-two." The floor manager (a hysterical performance by director Garry Marshall) insists he needs to talk with her, that she's way down. At that moment, 22 hits and David is momentarily caught in the euphoria until Linda pushes all her chips back onto 22 again and it's all gone.

together in one of those big tubs and ordering room service. Unfortunately, bribery is not a skill that comes easily to David and what they get at the now-defunct Desert Inn is the Junior Bridal Suite, which contains two heart-shaped beds you can't push together and a shower. "If Liberace had children, this would be their bedroom" is David's assessment. As someone who actually stayed at the Desert Inn in the mid-1980s and went back to Vegas later, the film serves as a bit of a time capsule as to what a stark difference the Vegas Strip of today looks like compared to the strip of the 1980s. David awakes around 2:30 in the morning to discover that Linda isn't to be found. He wanders in a stupor to the casino floor to find her hovering over the roulette table chanting, "Twenty-two, twenty-two." The floor manager (a hysterical performance by director Garry Marshall) insists he needs to talk with her, that she's way down. At that moment, 22 hits and David is momentarily caught in the euphoria until Linda pushes all her chips back onto 22 again and it's all gone.(FILM BUFF TRIVIA: For those who don't already know, the significance of the number 22 comes from Casablanca. It's the number Rick rigs the roulette wheel to hit so the young woman and her husband can win on his gaming tables and thwart Capt. Renault.)

David drags Linda into the all-night restaurant to try to figure out what happened and his worst fears are realized: She blew the entire nest egg. Brooks' outrage not only is understandable, it's monstrously funny. "Why

didn't you tell me when we got married that you were this horrible gambling addict? It's like when you have a venereal disease — you tell somebody!" "I've only gambled twice in my life. This was the second time," Linda replies. Desperate to try to salvage this disaster, David visits the casino manager in his office. He's very sympathetic to the Howards, realizing they've lost a lot of money and says that the room and food will be comped. That's not enough for David, who tries to go back into ad salesman mode, trying in vain to sell the manager on an ad campaign where the casino gives the Howards their money back to show that "The Desert Inn has heart" and to separate people like them from "schmucks who come to see Wayne Newton." The manager doesn't bite, but the duet between Brooks and Marshall remains one of the funniest scenes of the 1980s.

didn't you tell me when we got married that you were this horrible gambling addict? It's like when you have a venereal disease — you tell somebody!" "I've only gambled twice in my life. This was the second time," Linda replies. Desperate to try to salvage this disaster, David visits the casino manager in his office. He's very sympathetic to the Howards, realizing they've lost a lot of money and says that the room and food will be comped. That's not enough for David, who tries to go back into ad salesman mode, trying in vain to sell the manager on an ad campaign where the casino gives the Howards their money back to show that "The Desert Inn has heart" and to separate people like them from "schmucks who come to see Wayne Newton." The manager doesn't bite, but the duet between Brooks and Marshall remains one of the funniest scenes of the 1980s.From there, Lost in America does admittedly lose a little bit of its steam, but Brooks is such a comic powerhouse and he adheres to the cardinal rule of keeping a comedy to less than 90 minutes, so it doesn't overstay its welcome. At its essence, the screenplay has been devised as a series of interconnected setpieces. Alas, it doesn't keep building in comedic firepower, but it never stops making you laugh and that is more than

enough. It might seem an odd comparison, but many critics always made much of the slow burn Joe Pesci can make as an actor, from calm to explosive and in at least one scene here, I'd argue that Albert Brooks is the comic equivalent of that turn-on-a-dime Pesci skill. After the Howards exit Vegas, they head out in the RV, uncertain of where to go or how to make do with a little more than $800 left to their name. Linda keeps apologizing profusely, but David stays eerily calm — until they arrive at the Hoover Dam and Linda suggests they stop and check it out. "Nice dam, huh?" David says. "Do you want to go first, or should I?" The dam doesn't burst, but boy does David, first outside and then inside the Winnebago, when Linda insists the public not watch the fight. She actually suggests that they just split what money is left and go their separate ways and that she feels as if she's better now. David is incredulous. "You're better now? I think I was the sickest one to begin with." He then informs her that he obviously failed to explain the concept of the nest egg to her which they will go over in a series of many lectures. He even forbids her from using either part of the word nest egg. From now on, a bird lives in a round stick and she has things over easy with toast.

enough. It might seem an odd comparison, but many critics always made much of the slow burn Joe Pesci can make as an actor, from calm to explosive and in at least one scene here, I'd argue that Albert Brooks is the comic equivalent of that turn-on-a-dime Pesci skill. After the Howards exit Vegas, they head out in the RV, uncertain of where to go or how to make do with a little more than $800 left to their name. Linda keeps apologizing profusely, but David stays eerily calm — until they arrive at the Hoover Dam and Linda suggests they stop and check it out. "Nice dam, huh?" David says. "Do you want to go first, or should I?" The dam doesn't burst, but boy does David, first outside and then inside the Winnebago, when Linda insists the public not watch the fight. She actually suggests that they just split what money is left and go their separate ways and that she feels as if she's better now. David is incredulous. "You're better now? I think I was the sickest one to begin with." He then informs her that he obviously failed to explain the concept of the nest egg to her which they will go over in a series of many lectures. He even forbids her from using either part of the word nest egg. From now on, a bird lives in a round stick and she has things over easy with toast.Quickly running out of cash just to keep the RV gassed up, the Howards roll into a small Arizona town to look

for work. For David, needless to say, his resume makes him horribly overqualified for anything. When he visits the employment agency and mentions his previous salary was usually around $100,000 a year, but he and his wife decided to change their lives, the agency employee reasonably asks, "You couldn't change your life on a 100,000 a year?" Linda lucks into an assistant manager position — at Der Wienerschnitzel, where she impresses her teenage boss Skippy on the very first day by spotting that the french fries were still frozen in the fryer. "That's why I married her," David says sarcastically. "That's why I hired her!" Skippy adds in complete seriousness. David has to make do with a job as a crossing guard where the idea of benefits is a ride to and from the corner. He's not only taunted by the kids, he's taunted when a man in a Mercedes stops to ask for directions to the interstate and he smells that thick vinyl. I'll spare you from the final denouement of the film, in case you haven't seen it, but you can probably guess what happens.

for work. For David, needless to say, his resume makes him horribly overqualified for anything. When he visits the employment agency and mentions his previous salary was usually around $100,000 a year, but he and his wife decided to change their lives, the agency employee reasonably asks, "You couldn't change your life on a 100,000 a year?" Linda lucks into an assistant manager position — at Der Wienerschnitzel, where she impresses her teenage boss Skippy on the very first day by spotting that the french fries were still frozen in the fryer. "That's why I married her," David says sarcastically. "That's why I hired her!" Skippy adds in complete seriousness. David has to make do with a job as a crossing guard where the idea of benefits is a ride to and from the corner. He's not only taunted by the kids, he's taunted when a man in a Mercedes stops to ask for directions to the interstate and he smells that thick vinyl. I'll spare you from the final denouement of the film, in case you haven't seen it, but you can probably guess what happens. Still, Lost in America is a jewel alongside the other Brooks classics Modern Romance, Defending Your Life and Mother. Real Life and The Muse are worth watching as well. Alas, the same can't be said for Brooks' last writing-directing effort, 2005's Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World. While I might long for more writing-directing baubles from Brooks, at least we've received a wide range of acting performances from him. His feature film debut was Scorsese's Taxi Driver. He was Dan Aykroyd's partner in the prologue to Twilight Zone: The Movie. He received a much deserved Oscar nomination for Aaron Altman in Broadcast News. He also gave great character parts in mediocre films such as Critical Care and sleepers such as My First Mister. He lent his voice many times to characters in The Simpsons. In fact, his voice has been used a lot from the opening in Terms of Endearment as Aurora's husband to the frenzied fish father in Finding Nemo. Albert Brooks is a treasure and Lost in America is one of his most precious gems.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Albert Brooks, Aykroyd, Movie Tributes, Pesci, Scorsese, The Simpsons, Woody, Zemeckis

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, February 12, 2010

Denim dreams, design superstars

By Edward Copeland

In the opening scene of HBO's newest comedy How to Make It in America, which premieres Sunday night at 10 p.m. eastern, 9 p.m. central, a young New York entrepreneur tries to re-sell peanut M&Ms as he tells the captive passengers on the elevated train it's just a small step on his way to success. The new series takes all levels of that arduous journey as its focus as it examines an assortment of New Yorkers on various rungs of the social ladder with something to prove and dreams to achieve. Based on the first four episodes of the series' eight-episode first season, it's difficult to tell whether the show itself will similarly succeed as it's just finally starting to hit a groove as the preview episodes run out.

Bryan Greenberg and Victor Rasuk star as the series' ostensible leads Ben and Cam, two young New Yorkers who dream of finding their footing in the fashion industry. Ben pretty much has abandoned his dreams, content to work at Barney's and moon over his ex (Lake Bell, late of Boston Legal) while Cam still has the street hustler in him ready to take on "The Man" to become "The Man." Unfortunately, it takes money to make money, especially when you're living in a city with the cost of living of New York. Complicating the friends' plan is the release from prison of Cam's loan shark cousin Rene (the great Luis Guzman), whom the pair already owes $5,000. Rene has dreams of his own, namely becoming a high-energy drink king by taking on the NY franchise of a new product, though it's difficult to change his old business habits.

Some of their circle of friends have smaller dreams to achieve. David Kaplan (Eddie Kaye Thomas, best known for American Pie) is a hedge fund manager on his way to master of the universe status but his immediate goal is seeing if his high school friend Ben has enough pull to get him past the doorman at an exclusive Manhattan nightclub.

One of the executive producers for How to Make It in America is Mark Wahlberg, who brought Entourage to HBO. While I never warmed to Entourage, the new series shows some potential, despite a slow start. If the characters really want to make it, they might look into television. I've never seen credits such as the ones on How to Make It in America. There are seven credited actors but listed in the same size and font and each with their own screen are five executive producers, one co-executive producer, two producers and a casting director. The poor creator, Ian Edelman, gets a slightly smaller credit of his own.

Viewing the first four episodes, a lot of what transpires feels like exposition and while it produces sporadic laughs, it all seems like setup. Knowing that only four episodes remain in the premiere season, I have to wonder how far the story can go before the season is over. Most of the cast is likable, especially Greenberg and Masuk, but some of the main characters such as Scott "Kid Cudi" Mescudi's Domingo and Shannyn Sossamon's Gingy still aren't clearly drawn by the end of the first four episodes.

One actress who is not a regular and only appears in the third and fourth episodes though makes a quick and devastating impression and that is Martha Plimpton as Rachel's boss Edie Weitz in a interior design business. When Rachel feels as if she's wasting her life after visiting an old friend who has been helping in Africa with the HIV epidemic, Edie sets her straight. Anyone can find awful places to help in Africa, "We're saving this city 300 square feet at a time. We are design superstars." When Plimpton's on screen, her creation of Edie is so great that everyone else vanishes in her wake.

Whether any of the other wannabes will achieve superstar status is anyone's guess, but the How to Make It in America certainly shows potential, even if it's nowhere near the level of the great comedies of HBO's past.

Tweet

Labels: HBO, Television, Wahlberg

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, February 11, 2010

An unexpectedly cinematic life

By Edward Copeland

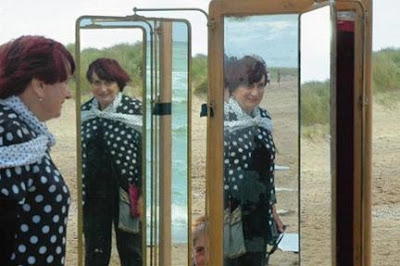

Director Agnes Varda was concentrating on her young life as a photographer when she was struck by the thought of making a movie, intrigued by the ideas of adding words to her pictures. She admits she was no film buff: She was 25 and recalled having seen only about 10 films in her lifetime. The new artform would shape her life both professionally and privately as she reflects in her unusual and personal autobiographical film The Beaches of Agnes.

As the film opens, Varda confesses that when she tells stories of other people, she always visualizes landscapes, but for this self-written, self-directed, self-narrated examination of her own life and career, she sees beaches. So that's where this highly stylized, truly unique sort of documentary begins as Varda takes us on tours of France and Los Angeles, recounting pivotal moments in her upbringing and how she broke into the film business and found love with her husband, the similarly celebrated filmmaker, the late Jacques Demy.

Varda's films have been a combination of documentaries and fictional features and The Beaches of Agnes seems to fuse both in a sometimes whimsical way, complete with a cartoon cutout of a cat asking Varda questions or the filmmaker practicing her driving in a stage prop of a car. Interspersed are scenes from both the locations of the filmographies of Varda and Demy as well as clips from the films, often projected in the most unusual of ways. Nothing is standard or typical about the way Varda presents this project.

Also included are some home movies, particularly touching ones made while Demy was dying and Varda was rushing to complete a film of his life story while he could still see it, Jacquot de Nantes. It's easily the most powerful part of a film that tends to the light side throughout most of its length, even as Varda marks her own 80th birthday. It does leave some questions unanswered. Varda mentions when she and Demy reconciled, yet if the film referred to a separation, it escaped me.

Even if you've never seen a film by Agnes Varda (or Jacques Demy for that matter), The Beaches of Agnes proves to be a wonderful portrait of the film artist as a young and old woman along with everything in between.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Documentary, Foreign

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

I'll have a Gogol with a twist

By Edward Copeland

When a movie year ends, more often than not, I tend to conclude that it was another weak one, especially since my situation takes me a long time to catch up with a sizable crop of a year's output. Still, with many films from 2009 that I've still yet to see, I have to say I'm hard pressed to come up with a recent year that has produced so many great original screenplays. Cold Souls is just the latest example of that group that I've managed to see.

While I still find it supremely silly that the Oscars expanded best picture to 10 nominees, as I do my usual rough draft of my own awards, it's the original screenplay category that is giving me fits. There have been far too many scripts beyond the usual number of five that it pains me each time I have to consider making a cut. Best picture itself hasn't been as difficult (and adapted screenplay hasn't been remotely that hard) but original screenplay 2009 is a heartbreaker for me (with director a close second).

Cold Souls is the latest film to toss that original screenplay category asunder. At first description, writer-director Sophie Barthes' film seems as if it's the newest film off what I like to call the Being John Malkovich assembly line, but it's so much deeper and better than that, thanks mainly to its phenomenal lead, Paul Giamatti playing a film version of himself. Giamatti is busily rehearsing the lead in a stage production of Chekhov's Uncle Vanya, but all that Russian angst and gloom has finally begun to take its toll on the actor as he attempts to go about the rest of his normal day.

His agent turns him on to an article in The New Yorker about a company that offers the temporary removal of one's soul, to allow for the removal of that unbearable metaphysical weight for a period of time so people can get through difficult moments of their lives. Giamatti, understandably, is skeptical at first, but the lead doctor on the process (a wonderfully droll David Strathairn) talks him into giving it a try. Then things get complicated.

To describe much more of the film's twists would ruin its joys but let's just say it involves crooked Russians who traffic in human souls, the completely bearable nature of soullessness and donor souls to serve other functions.

Instead, it's best to just let Cold Souls unfold before you at its own leisurely pace and marvel at Giamatti's work. He isn't just playing a fictionalized version of himself, he's playing multiple fictionalized versions of himself all while maintaining his own essence. It's a work of wonder.

In addition to the able help of Strathairn, the cast also gets a lift from Emily Watson as a fictionalized version of Giamatti's wife and, most especially, Dina Korzun as Nina, a Russian woman who earns her living as a mule shepherding souls back and forth between New York and St. Petersburg.

Barthes finds both the perfect tone and pace for her movie that complements brilliantly her intelligent script. Still, in the end, this is Paul Giamatti's show from beginning to end.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Giamatti, Malkovich

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, February 09, 2010

Got no strings to hold this film down

By Edward Copeland

Even though my own circumstances confine practically all my moviewatching to home viewing, I think something was lost when Disney stopped its practice of re-releasing its animated classics to theaters every seven years or so with the idea that each new generation would get the chance to experience the magic of something like Pinocchio, which turns 70 today, in a darkened movie theater. With such a constant complaint of a lack of solid films for family viewing, you'd know there would be an audience and don't you expect that as great as Pinocchio remains today, 70 years after its debut, is not going to apply to an animated film such as Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs (or going further back a Ferngully or Rock-a-Doodle) decades down the road?

Watching Pinocchio again, probably for the first time since I was a youngster, it's quite amazing to remember that this was only the second animated feature Walt Disney had made following 1937's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Talk about remarkable achievements for essentially uncharted territories, his directors,

writers and animators worked wonders with the Carlo Collodi dark 1873 fable. All of the voice talent went uncredited as well, as opposed to today where it can sometimes be distracting as stars bring characters to life and often front-end billing. (One of the uncredited voices on Pinocchio for some of the minor parts happened to be one Mel Blanc, whom I bet they heard more from in the future.) The supervising directors are credited as Hamilton Luske and Ben Sharpsteen, whose supervising directing credits would appear collectively and separately on such future Disney classics as Fantasia, Dumbo, Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp and 101 Dalmatians. Much is made of the amazing detail that can be achieved with computer-generated animation today, whether it be a Beauty and the Beast or any Pixar effort, but for 70 years ago, the team assembled by Disney for Pinocchio produced some remarkably rendered images. Whether it's simple scenes as Pinocchio's large eye peering in a keyhole as Jiminy Cricket attempts to pick a lock or when Pinocchio is goaded into take a huge puff of a cigar on Pleasure Island and his face goes from every possible shade of red, to purple before his eyes fill with pools of water before he collapses in a shade of green.

Let's not give short shrift to the story while I wax on about the art. Pinocchio isn't a simple retelling of a fable that every child would know, it goes deeper than most of those because it has a real message about avoiding