Monday, December 18, 2006

Company Worth Keeping

By Josh R

The first time I saw Citizen Kane, I probably was about 14 years old. I didn’t see what the big deal was. Listening to classical music was about as much fun as sitting through a Yom Kippur service, and following televised election returns produced nearly as many thrills as shopping for school supplies. Wine tasted like the kind of bitter over-the-counter medicine your mom had to force down your throat when you had the flu, and shellfish — I don’t count shrimp — wasn’t something I was even willing to look at, let alone ingest (let’s be honest…no matter how they taste, the tentacled bastards still look like overgrown insects). From the moment I first heard them, the vocal stylings of Billie Holiday brought to mind visions of singing Muppets. Personal tastes are subjective, formed in the early stages of our development, and aren’t always subject to change.

Stephen Sondheim’s Company, initially presented on Broadway in 1970 and the winner of the following year’s Tony Award for best musical, is one of those shows I’ve managed to remain resolutely blasé about since it first popped up on my radar screen. I’ve listened to the score countless times since I got the original cast recording some 15 years ago, and have seen several productions of it, most notably the 1996 Roundabout Theater Company revival directed by Scott Ellis. While the score includes two of Sondheim’s most indelible compositions — the acid-laced skewering of “The Ladies Who Lunch” and that bittersweet anthem of longing, “Being Alive” — as a whole it doesn’t qualify as one of the composer’s most interesting or memorable.

The essentially plotless book by George Furth, generally acknowledged as one the weakest for any Sondheim show, feels like a series of second-rate sketches from The Carol Burnett Show — the kind where Carol reported for duty in plain clothes and played it relatively straight. Basically, it’s a series of vignettes linked together by the presence of Bobby, a commitment-phobic bachelor, who is alternately intrigued and horrified by what he observes of the state of matrimony, as embodied by his circle of married friends. I’ve always maintained that it’s a show I’d rather listen to than watch on a stage.

If I remember correctly, I was 16 when I saw Citizen Kane for the second time in a high school journalism class and recognized it for the masterpiece that it is. I don’t remember how old I was when I developed a taste for chardonnay and shellfish — just put a steamed lobster in front of me and I’m as happy as a clam. I can listen to Dvorak’s New World Symphony over and over again for hours on end, and election night usually finds me glued to the television set parsing over returns with the feverish intensity of Madame Curie trying to isolate radium.

I’m not entirely sure how and when most of these reversals came about; some must have been the result of gradual persuasion as my tastes reached maturity, while others took the form of abrupt about-faces. I can however pinpoint Dec. 5, 2006, as the day when Company not only finally made sense, but made a believer out of me. A character in the show, the tart-tongued Joanne, says toward the end of the evening: “You’re not a kid anymore. I don’t think you’ll ever be a kid again, kiddo.” I guess I’ve done my share of growing up since mixed drinks went down like Nyquil and listening to Tchaikovsky produced about as many fissions of delight as hearing a policeman outline the specifics of car safety for my fifth grade class. From this point on, I don’t think I’ll ever be able to be blasé about Company again, or regard it with anything close to indifference.

Lest you infer that my tastes are as changeable as the winds, I’d like to state for the record that Billie Holiday still sounds like a Muppet. And somewhere deep down, I suspect that Company still has as much depth as a television special featuring The Muppets. The brilliance of the current Broadway revival, directed with bracing clarity by John Doyle, is that it not only minimizes the flaws — and I have to believe, based on my previous experiences with the show, that those flaws still exist — but succeeds in making them incidental to the point of irrelevance. Doyle’s interpretation marks a radical departure from any Company that’s come before, and not just because the actors double as the orchestra. This is Company deconstructed, re-imagined, and enthrallingly revitalized before our very eyes — all this while remaining fairly faithful to the original text, which now re-emerges through the fog of previous productions with a startling sense of urgency.

If my reaction borders on incredulity, it must be noted how inexorably trite Company has always seemed in previous incarnations — seeing it shoot off sparks on the stage of the Barrymore Theatre is like watching the least coordinated kid in gym class team pull off a gravity-defying double play worthy of Derek Jeter. The other Companies I’ve seen — even the good ones — never really solved the problem of how to transcend the problems of the George Furth book, which still gets slammed by critics some 30-odd years after it was first unveiled (neither Ben Brantley nor Clive Barnes could resist taking potshots at it in what otherwise amounted to glowing raves for this production). If the Sondheim score is challenging and intricate, the Furth book is facile and undernourished. The 1996 Roundabout production — cast within an inch of its life with a veritable dream team of past and future Tony winners and nominees — played like period kitsch, complete with shag carpeting. If it allowed each of its cast members to shine in turn when given their moment in the spotlight — particularly Veanne Cox as an anxious bride-to-be, and La Chanze, performing that classic ode to urban alienation “Another Hundred People” — it never really made a case for Company as anything more than a tuneful cabaret on the subject of marriage with corresponding skits.

The skits are still present and accounted for — the wife who demonstrates her karate moves on her husband for the benefit of a dinner guest, the couple who decide to spice up their marriage by getting divorced, the parents who experiment with pot after the kids have gone to bed and the bride who wants out of her own wedding — and they still manage to prompt a few mild titters. But there’s something else going on beneath the surface — if not flat-out desperation, than a growing sense of unease. Company doesn’t look or sound the way it has before, something which informs and deepens the material in unexpected ways. As directed by John Doyle, who helmed last season’s acclaimed revival of Sweeney Todd, it’s still set in Manhattan, but in a very different Manhattan than the one Neil Simon imagined — and it’s one that most of us seldom if ever get to see.

If you’re seen the city as a tourist or moviegoer and are only familiar with bright lights, busy sidewalks, honking horns and colorfully noisy “Noo Yawk” types, it may surprise you to know that there are two very different civilizations co-existing on one little island — and they can be defined by their proximity to sea level. The world of tastefully furnished penthouses and rooftop VIP lounges might as well exist on a different planet from the hustle and bustle of the street some 40-odd stories below — and if you live in the world of $500 a plate benefits, trust-fund legacies, personal shoppers and corporate board memberships, the most you see of that other planet on the ground is the distance between the doorman and the limousine (Yes, Virginia, there are lifelong city-dwellers who have never set foot in a subway station). Doyle has jettisoned the day-glo colors, the shag carpeting, and the element of bourgeois boisterousness that has characterized previous Companies, and turned the volume down to a hush, dulcet tone. The stage is a spartan expanse of icy blacks and silvers aligned in sharp geometric patterns, populated by elegant figures subtly clad in black-and-white Armani, with transparent Lucite boxes serving as all-purpose furnishing and props. A spirit of well-heeled cosmopolitan lugubriousness hovers in the air; subdued and sophisticated to the point of reverence, it’s almost like looking into a post-modern museum installation. A classical white column with a wraparound radiator extends upwards like a lone barren tree — tellingly, the character of Bobby stands on the radiator, which serves as a perch, clinging to the column when what’s going on below becomes too frightening to bear. Noise and energy can be intimidating, but it’s silence and tact — that oppressive underpinnings of that peculiar brand of sophistication that used to make me squirm in my seat when my grandfather took me to dinner at The Harvard Club — that can truly inspire discomfort and dread. By taking Company away from its Neil Simon-ish origins and steering it firmly toward the realm of John Cheever, Doyle has removed any shred of triviality from a work, on paper, would seem to consist of nothing but.

This infusion of chilly elegance alone only partially accounts for the transformation of Company. As in his production of Sweeney Todd, Doyle’s cast doubles as the orchestra. Although that production had many admirers — myself among them — the device felt more like a gimmick (albeit an effective one) than a dramatic necessity. The opposite proves to be the case in this context. The actors who played married couples are paired up with corresponding instruments — a violinist is mated with a cellist, a trumpeter with a trombonist, etc. — creating a sort of Noah’s Ark of matching musicians. The only one who doesn’t play an instrument is Bobby — incapable of making music on his own, he watches from the sidelines, sometimes with a visible relief at not having to participate, and at other times with a wistful yearning to be included.

A show requires a compelling central character in order to hold an audience’s interest, and until now, it’s an area in which Company has been noticeably lacking. The character of Bobby has always existed as something of a cipher, with few distinguishing traits and no clear motivation beyond some general fear of commitment — his pathology isn’t any more complex that than which can be encapsulated in an hour-long episode of Oprah. The part is usually played in a vein of bland affability, as a benign sort of everyman onto whom anything can be projected. This approach always seems to beg the question of how Bobby can exist as the object of all of the other characters’ attentions, when he’s just not that interesting on his terms.

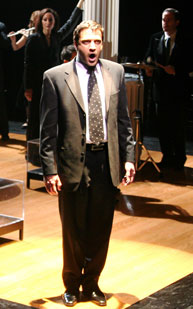

In the current Broadway production, the role is played by Raul Esparza. For several years, I have been familiar with the actor by reputation, although this marks the first time I’ve seen him onstage — and I sincerely hope it won’t be the last. While Esparza is a remarkably polished singer, it need be mentioned that he is first and foremost a supremely gifted dramatic actor — he invests the role with such depth of feeling and unearths so much unsuspected complexity that it blows the lid off whatever you thought you knew about the superficially charming child-man torn between playing it safe and Being Alive. Glib and avuncular at one moment, guarded and defensive in the next, he’s a man who’s struggling to find his bearings, a prisoner of his own self-imposed isolation and both comforted and frightened by his own capacity for detachment. Finally, the character makes sense. Watching Esparza burrow into the tangled web of emotions that inform his concept of Bobby marks the first time I’ve ever truly understood the character as damaged — and damaging to others (particularly the women he comes into contact with).

If Doyle and Esparza rightly restore the focus of the show to where it needs to be and always should have been — on Bobby, as to opposed to the gallery of colorful kooks surrounding him — then it’s perhaps only right that the peripheral characters don’t register as strongly as they have before (and in The Roundabout production, Bobby was almost an afterthought). The one exception is the martini-soaked Joanne, expertly rendered by Barbara Walsh, a Tony nominee for her memorable turn in 1992’s Falsettos. The actress wisely steers clear of trying to imitate the role’s originator, Elaine Stritch — this Joanne is less a volatile, brass-knuckled firecracker than equal parts high-fashion vampire and louche siren. With the stony features and heavy-lidded sensuality of a young Anjelica Huston, she expertly navigates her way through the curdled cocktail of “The Ladies Who Lunch.” With all due respect to her formidable predecessor, I doubt anyone watching the original production thought the brassy, ballsy Ms. Stritch was ever really in any danger of turning into one of those caftan-wearing, Life-Magazine-clutching ladies trying on hats at Bergdorf’s while trying not to fade into the meaninglessness of their own existence. You can tell Walsh’s Joanne has not only been there, but that she’s scared of going back — and would probably disappear altogether, if she didn’t work so hard to stay drunk and catty. The rest of the casting is not always as successful — Heather Laws struggles mightily with the rapid-fire pace of “Getting Married Today” — although a trio of saxophone-toting lovelies named Angel Desai, Elizabeth Stanley and Kelly Jeanne Grant do a bang-up version of “You Could Drive a Person Crazy” (for those familiar with the song, it’s wittily orchestrated so that the celebrated “do-do, do-do, dos!” are saxed instead of sung). Desai makes a refreshingly spiky Marta and gets optimum mileage from “Another Hundred People,” while Stanley makes the flight attendant April a more touching figure than she would normally be, given how the character is essentially a walking dumb blonde joke. The other performers are essentially just along for the ride, although they more than justify their presence with their prodigious skill as musicians.

As capable as many of the other performers are, it’s Esparza’s Bobby who takes this Company out of the realm of shallow cabaret and makes it a thoughtful, occasionally harrowing consideration of one man’s inner turmoil. At the show’s climax, Bobby finally sits down at the piano, and begins to play the opening notes of “Being Alive”, haltingly, painfully at first and with visible effort. The song gradually grows into a genuine, haunting plea for deliverance from a life half-lived and self-imposed exile from the realm of human contact. Esparza invests the song with such pain and yearning that it eclipses any other rendition you may have heard in terms of its dramatic impact. Instead of ending with a reprise of the jaunty title song, the show ends with the lone figure of Bobby onstage, gazing up into a spotlight, blowing out his birthday candles in the fervent wish of being able to love and be loved. Growing up is about change, a realignment of interests and priorities. More than coming to recognize the merits of things you were never able to appreciate as a kid — Citizen Kane, alcoholic beverages, Company, whatever — it’s about arriving at the realization that whatever it is which frightens you the most, that which you’ve been holding at arm’s length, may be the one thing you truly need.

Tweet

Labels: Musicals, Neil Simon, Sondheim, Theater

Comments:

<< Home

I wish I could see this. I've seen two productions of Company, including the 1996 Roundabout revival, and the score has always seemed better than the show itself. I have three Company cast albums. Will I need to acquire a fourth?

As I say in the review, it's a show I've always said I'd rather listen to than watch on a stage...that is, until now. I don't know how much of what makes this production so great will come through in the cast album - aurally, it's not markedly different from other Companies, with the notable exception of "You Could Drive a Person Crazy" for the reasons described in the post. I would probably only reccommend the purchase of the OCR to Sondheim cultists who really, really love this particular score, since (sadly)listening to it out of context isn't going to communicate the effect of seeing it on stage. I'm afraid this particularly true of Mr. Esparza's performance - as accomplished a singer as he is, the brilliance of his Bobby lies in the acting.

Post a Comment

<< Home