Wednesday, March 31, 2010

David Mills (1961-2010)

I thought about writing a tribute to David Mills, the gifted television writer (check out his credits on IMDb) and blogger, to go with the shocking news of his death, but I knew I couldn't do it justice, no matter how much I worshipped The Wire and loved Homicide: Life on the Street and looked forward to Treme, the new HBO series he was working on with David Simon, where Mills passed away on the set at the far too young age of 48. I never met the man, though he is my first Facebook friend to die. However, Alan Sepinwall did know him and I read his lovely piece at What's Alan Watching and he put everything so much better than I could ever hope to, that I thought just linking to that would be the best tribute of all. RIP, Mr. Mills.

Tweet

Labels: David Simon, HBO, Homicide, Obituary, The Wire, Treme

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, March 29, 2010

You talk too much

By Edward Copeland

As the saying goes, clothes make the man. It also can be said that in the case of some movies, an actor makes the film and that's the case of Matt Damon's hysterical performance in Steven Soderbergh's The Informant!

Based on a book which tells the true story of one Mark Whitacre, an executive for Archer Daniels Midland, who turns FBI informant to tell about an international price-fixing scheme, only things aren't as simple as they seem.

What makes The Informant! so unusual is that this isn't a film along the lines of a whistle-blower drama such as The Insider. No, Soderbergh and the screenplay by Scott Z. Burns have opted for a wild, comical approach to the material based on the character of Whitacre himself, an approach that would have likely fallen flat if not for Damon's acerbically funny performance as a deluded man who believes he's doing everything for the right reasons and also has the unfortunate habit of sharing most details of his work with anyone in his vicinity.

At first, it appears as if Whitacre's motives are pure, sparked by fear he'll be caught up in the malfeasance his company is committing, so he becomes very close to the FBI agents he's working with (Joel McHale and a spectacular Scott Bakula). Unfortunately for the FBI, while Mark likes to flap his lips a lot, he doesn't tell the right people the right things at the right time, namely that his cooperation is part of his insane plot to decapitate the top executives at ADM so he will be appointed head of the company. It doesn't occur to him that the board won't be eager to reward the man who gives the company a huge legal black eye.

Whitacre isn't completely dumb though: He's got a plan for that as well, when it's uncovered he's been secretly embezzling millions from the company for his own "severance" package should things go awry, but he thinks he's in the right there as well since what he's taken is a pittance to what is being ripped off in the price-fixing scheme.

All the performers do well, but it's Damon's remarkable turn that powers the movie and holds your attention. He gives a side-splittingly funny deadpan performance and it may well be the best he's ever given.

Soderbergh moves the action along swiftly and continues his reputation as the major director you simply can't define. The Informant! is the 20th feature film Soderbergh has made since he caught the film world's attention with sex, lies, and videotape in 1989 and you can't pigeonhole him in a genre or a style. He's made great films, awful films, experimental films and everything in between. He may be our most compulsive filmmaker. He just can't be stopped.

The Informant! certainly won't land in Soderbergh's greatest pile and there's nothing experimental about it, but Damon is so much fun, there are worse ways to spend an hour and 45 minutes.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Matt Damon, Soderbergh

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, March 26, 2010

Don't let the past remind us of what we are not now

By Edward Copeland

It's an old joke among some baby boomers (of which I'm very proudly not a member) that if they are of the right age and background, they all claim to have attended Woodstock in 1969. Of course, we know this simply isn't mathematically possible, but I think what confused the issue was Michael Wadleigh's remarkable Oscar-winning documentary of the event, released on this date in 1970. I think it's the pervasiveness of the images from that film that accounts for the collective memory of a generation.

Woodstock functions as a true documentary, it documents an event as well as a time and a place. For film buffs, there also is a bit of movie history at work as well. It earned film editor Thelma Schoonmaker her first Oscar nomination while she worked alongside a young assistant director and editor named Martin Scorsese,

+1.JPG) which began a collaboration that continued through every feature Scorsese has made as a director. It also earned an Oscar nomination for sound in addition to its documentary feature win. Something must have been in the air at the Academy that year: the original song score Oscar went to The Beatles for the documentary Let It Be. In the process of chronicling Woodstock, more than 100 miles of films were exposed and 16 cameras were employed, which seems as if it's that an amazingly small number given how much is captured on screen as the images hover, float and glide above and through the crowds, around the stage, take side trips into the neighboring town and that's not even mentioning the infamous split screens (sometimes divided into three).

which began a collaboration that continued through every feature Scorsese has made as a director. It also earned an Oscar nomination for sound in addition to its documentary feature win. Something must have been in the air at the Academy that year: the original song score Oscar went to The Beatles for the documentary Let It Be. In the process of chronicling Woodstock, more than 100 miles of films were exposed and 16 cameras were employed, which seems as if it's that an amazingly small number given how much is captured on screen as the images hover, float and glide above and through the crowds, around the stage, take side trips into the neighboring town and that's not even mentioning the infamous split screens (sometimes divided into three).While the movie's reputation is that of a concert film, it's often the nonmusical portions that prove most fascinating. The film opens with one Sidney Westerfield, owner of an antique tavern in Mongaup Valley, N.Y.,

expressing amazement about the event, when 50,000 concertgoers and nearly a million people who showed up. He even had nothing but praise for the young people, finding them nothing but polite. The congestion and traffic tie-ups didn't even bother him, even though that meant he couldn't get out for food and had to live on corn flakes for two days. It was "too big for the world," Westerfield said. In fact, the film was so big that despite its reputation and acclaim, Wadleigh added unused footage (including a performance by Janis Joplin) and released a director's cut which is now the only version of the film available. It's just as great as the original but the changes are almost imperceptible except for the epitaph at the end listing all those who have died since Woodstock was held in August 1969.

expressing amazement about the event, when 50,000 concertgoers and nearly a million people who showed up. He even had nothing but praise for the young people, finding them nothing but polite. The congestion and traffic tie-ups didn't even bother him, even though that meant he couldn't get out for food and had to live on corn flakes for two days. It was "too big for the world," Westerfield said. In fact, the film was so big that despite its reputation and acclaim, Wadleigh added unused footage (including a performance by Janis Joplin) and released a director's cut which is now the only version of the film available. It's just as great as the original but the changes are almost imperceptible except for the epitaph at the end listing all those who have died since Woodstock was held in August 1969.

Since I was a mere infant at the time, learning of the turbulent late '60s through history and other documentary artifacts, it's always surprising to see how peaceful and what a lack of conflict occurred during the Woodstock Festival, which took place just a little more than a year after the chaos of the Democratic Convention in Chicago. While Vietnam is certainly present, the peace part of the event predominates as

much as the music and the few citizens in the nearby town who complain seem to be the exception rather than the rule. All of the other adults seem to find these mostly long-haired young people taking over their area "like an army invading a nation" charming and polite. The businesspeople welcomed the economic boost, others reveled in delight at the politeness of the young people and even took offense when one young man referred to himself as a freak, believing he was being critical of himself. "From what I've heard from the outside sources for many years I was very, very much surprised and I'm very happy to say we think the people of this country should be proud of these kids, not withstanding the way they dress or the way they wear their hair, that's their own personal business," one man said, "but their, their inner workings, their inner selves, their, their self-demeanour cannot be questioned; they can't be questioned as good American citizens." The official who said that was the police chief. Given the lack of civility that has developed in this country over issues as innocuous as health care, I wonder if these sort of reactions would even be possible today. Would people have welcomed and complimented large groups of Iraq war protesters attending a concert like Woodstock like this if one had been held? Somehow, I doubt it.

much as the music and the few citizens in the nearby town who complain seem to be the exception rather than the rule. All of the other adults seem to find these mostly long-haired young people taking over their area "like an army invading a nation" charming and polite. The businesspeople welcomed the economic boost, others reveled in delight at the politeness of the young people and even took offense when one young man referred to himself as a freak, believing he was being critical of himself. "From what I've heard from the outside sources for many years I was very, very much surprised and I'm very happy to say we think the people of this country should be proud of these kids, not withstanding the way they dress or the way they wear their hair, that's their own personal business," one man said, "but their, their inner workings, their inner selves, their, their self-demeanour cannot be questioned; they can't be questioned as good American citizens." The official who said that was the police chief. Given the lack of civility that has developed in this country over issues as innocuous as health care, I wonder if these sort of reactions would even be possible today. Would people have welcomed and complimented large groups of Iraq war protesters attending a concert like Woodstock like this if one had been held? Somehow, I doubt it.Max Yasgur, owner of the farm where the concert was held

It took nine months of planning to bring off the concert at a cost of a couple of million dollars and it began as a paid event but as it became a cultural event and young people trampled the fences, the organizers decided to let it be a free event and take the monetary loss, deciding that the people's welfare and the music were "a helluva lot more important than the dollar." Imagine something like that occurring in the Age of TicketMaster.

The original crowd expectation ranged from 50,000 to 200,000 but no one has ever nailed down an exact count, with somewhere north of half a million people being the best guess. With interstates tied up, artists had to be flown in by helicopter. With so many cameras roaming the grounds, you get a lot of great nonsequitur images: nuns flashing peace signs; an interview by kazoo; a naked guy standing in the crowd and dancing with a sheep. One of the film's most compelling moments is a lengthy interview with a young couple, though they might not call themselves a couple. "We ball and everything but we're not in love or anything," the girl explains. The boy gets deeper, speaking of his immigrant father who doesn't understand his aimlessness in America, the land of opportunity. Why aren't you playing the game? his father wants to know. The sincere young man displays a degree of insight when he says that most people at Woodstock are looking for an answer when there really isn't one and they are all sort of lost.

The original crowd expectation ranged from 50,000 to 200,000 but no one has ever nailed down an exact count, with somewhere north of half a million people being the best guess. With interstates tied up, artists had to be flown in by helicopter. With so many cameras roaming the grounds, you get a lot of great nonsequitur images: nuns flashing peace signs; an interview by kazoo; a naked guy standing in the crowd and dancing with a sheep. One of the film's most compelling moments is a lengthy interview with a young couple, though they might not call themselves a couple. "We ball and everything but we're not in love or anything," the girl explains. The boy gets deeper, speaking of his immigrant father who doesn't understand his aimlessness in America, the land of opportunity. Why aren't you playing the game? his father wants to know. The sincere young man displays a degree of insight when he says that most people at Woodstock are looking for an answer when there really isn't one and they are all sort of lost.The sincerity of the participants is why the film holds up so well 40 years later after all the mockery and parodies of the 1960s youth culture and mindset. Even the moments that lend themselves to laughter are unmistakably real as the P.A. announcements (somewhat reminiscent of those in the same year's fictional

film, Robert Altman's MASH) warning concertgoers to steer clear of the brown acid but later adding that the acid isn't poison, it's just bad and if one felt the need to experiment, it's best to try just half a tab. Then when a downpour of rain turns the field into a muddy mess, there are some conspiratorial-minded attendees who are convinced that helicopters they see hovering overhead are really the government seeding the clouds to spoil their party. It's ironic, because the Army National Guard helicopters that were there were brought medical teams to help with anyone who need medical aid (a baby was born at the festival after all). Pretty incredible considering that this was during Vietnam and the Nixon Administration. Compare that to how slow the response was to a national disaster such as Hurricane Katrina but a hand was lent to natural opposition attending a concert. The times, they have-a-changed, and not for the better. Could Nixon have been the real compassionate conservative?

film, Robert Altman's MASH) warning concertgoers to steer clear of the brown acid but later adding that the acid isn't poison, it's just bad and if one felt the need to experiment, it's best to try just half a tab. Then when a downpour of rain turns the field into a muddy mess, there are some conspiratorial-minded attendees who are convinced that helicopters they see hovering overhead are really the government seeding the clouds to spoil their party. It's ironic, because the Army National Guard helicopters that were there were brought medical teams to help with anyone who need medical aid (a baby was born at the festival after all). Pretty incredible considering that this was during Vietnam and the Nixon Administration. Compare that to how slow the response was to a national disaster such as Hurricane Katrina but a hand was lent to natural opposition attending a concert. The times, they have-a-changed, and not for the better. Could Nixon have been the real compassionate conservative?

As for the film's techniques itself, it is the use of split screens that are understandably most celebrated. Unlike films such as Mike Figgis' Time Code, the use of the device comes off appropriate instead of as a gimmick or a distraction. In fact, often the juxtapositions prove quite perfect as in one section where the left half shows an interview with a concert organizer talking quite seriously about what's going on while on the right an anonymous couple prepares to lay down in tall grass to make love. The device is used extensively during the musical acts, showing the same performer from different angles or different members of the band or

contrasting the performer with the crowd enjoying the show. You get different ways of seeing Crosby, Stills and Nash perform instead of a simple three shot. One thing I had forgotten was how new an act the trio was. "This is the second time we've ever played in front of people, man, we're scared shitless," Stephen Stills told the crowd. Even though Woodstock is a long film, there still isn't enough room to include all the musical acts who participated or all the songs they played because the movie is first and foremost a documentary and that's what makes it superb. As the festival did, it begins with Richie Havens, it includes a young Arlo Guthrie (whom I never noticed before, but bears a striking resemblance to Bob Geldof), Joan Baez speaks of her imprisoned husband and federal inmates hunger striking his imprisonment over the draft, Country Joe McDonald and the Fish perform (and the film adds a sing-along bouncing ball and lyrics), Joe Cocker does what he does and makes John Belushi's spasmodic impression seem like less of a parody, The Who hits the stage and Pete Townshend forgoes smashing his guitar in favor of giving it as a gift to the audience and, for some reason, Sha Na Na sings "At the Hop." To close the festival, Jimi Hendrix shows his absolute mastery of the guitar with a unique rendition of the "Star-Spangled Banner" which then blends seamlessly into "Purple Haze" as the camera captures the messy aftermath once everyone had left.

contrasting the performer with the crowd enjoying the show. You get different ways of seeing Crosby, Stills and Nash perform instead of a simple three shot. One thing I had forgotten was how new an act the trio was. "This is the second time we've ever played in front of people, man, we're scared shitless," Stephen Stills told the crowd. Even though Woodstock is a long film, there still isn't enough room to include all the musical acts who participated or all the songs they played because the movie is first and foremost a documentary and that's what makes it superb. As the festival did, it begins with Richie Havens, it includes a young Arlo Guthrie (whom I never noticed before, but bears a striking resemblance to Bob Geldof), Joan Baez speaks of her imprisoned husband and federal inmates hunger striking his imprisonment over the draft, Country Joe McDonald and the Fish perform (and the film adds a sing-along bouncing ball and lyrics), Joe Cocker does what he does and makes John Belushi's spasmodic impression seem like less of a parody, The Who hits the stage and Pete Townshend forgoes smashing his guitar in favor of giving it as a gift to the audience and, for some reason, Sha Na Na sings "At the Hop." To close the festival, Jimi Hendrix shows his absolute mastery of the guitar with a unique rendition of the "Star-Spangled Banner" which then blends seamlessly into "Purple Haze" as the camera captures the messy aftermath once everyone had left.

Woodstock, both the event and the documentary, was a once in a lifetime occurrence. There have been similar attempts such as the massive charity concert Live Aid, but those were all so prepackaged that they lacked the certain improvisational feel that came with the Woodstock Nation. Of course, that didn't stop them from trying to spawn a sequel. If followups are good for Hollywood and Broadway and books, why not try to re-create a once-in-a-lifetime zeitgeist, which is precisely what they attempted on the 25th anniversary in 1994, broadcast on MTV of course. At the time, I dreamed of making a documentary of the event, though it would have been of a particularly satirical bent. I envisioned a three-way split screen with a featured artist in the center, a twentysomething decked out in the proper corporate wardrobe and drinking the right sponsor's beverage on the right and an aging baby boomer on the left, watching at home on television while working out on his or her StairMaster. Alas, I didn't make that film. It's difficult to make the same history twice, and it shouldn't be tried, but it's a great thing Michael Wadleigh and his crew were there in August 1969 to record a lasting document of what happened on Max Yasgur's farm. The documentary already resides in the Library of Congress' collection of historic films and it is great for future generations to have this movie to learn from and look back on. The music isn't too bad either.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Altman, Beatles, Documentary, Movie Tributes, Music, Oscars, Scorsese

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Robert Culp (1930-2010)

His best-known roles always placed Robert Culp as part of a team or in the role of a sidekick, but that gives a bit of short shrift to the career of the actor, who has died at age 79 after taking a fall at his home.

His first big hit was as the agent teamed with Bill Cosby on the landmark 1960s series I Spy. In the 1980s, he aided the unlikely hero in the campy sensation The Greatest American Hero. Those were far from the only things on Culp's resume however.

Beginning in the early 1950s, he worked on many of the standard dramatic and episodic television series such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and the various theatrical series. His first regular series, Trackdown, was a western where Culp played a Texas ranger tracking down an assortment of bad guys. The series lasted 70 episodes over three years and its main director was a man named Sam Peckinpah.

His first feature film appearance didn't arrive until 1963 in PT 109, the story of JFK's experiences in World War II. Perhaps his best-known film role was in 1969's Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice. He also played the president opposite Julia Roberts and Denzel Washington in the adaptation of John Grisham's The Pelican Brief.

For me though, some of my favorite Culp memories are his four appearances on various episodes of Columbo, particularly the one where he played a motivational expert who used subliminal messages to lead to a murder. R.I.P. Mr. Culp.

Tweet

Labels: Denzel, Hitchcock, Julia Roberts, Obituary, Peckinpah, Television

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

The most versatile monsters around

By Edward Copeland

With as much as is being written about vampires in light of the Twilight books and movies and HBO's True Blood and countless other vampire-theme tales (Don't forget Elton John's short-lived Broadway musical Lestat), I know I'm not the only one who wishes someone would drive a stake through the heart of the whole genre (and I loved the TV show Buffy, the Vampire Slayer). That's why it's so amazing that whether it is played for straight horror or for pure laughs, zombie movies almost always turn out well as is the case with the fun as hell Zombieland. Maybe it's because none of these undead spend time mooning over unrequited love: they want to eat humans and humans want to bash their heads in. It's as simple as that. Zombies aren't into boinking and long, poignant kisses.

Zombieland definitely belongs to the "we're here to entertain" school of undead flicks and it easily receives a passing grade thanks to its cast and its efficient pacing by director Ruben Fleischer and wry script by Rhett Reese & Paul Wernick.

As with pretty much every zombie flick, you can guess the plot: some sort of virus has turned a location (this time the U.S.) into a wasteland populated by the undead and the few survivors cling together to hang on to their humanity.

Jesse Eisenberg stars as Columbus (the survivors choose to go by their home cities to avoid attachments to survivors they encounter), a neurotic college student who has somehow survived thanks to a handy list of rules he's developed to stay alive against the marauding ghouls. While on the road, he hooks up with the Twinkie-obsessed redneck Tallahassee (Woody Harrelson) and the two make a fine zombie-killing team, even if Columbus does grind on Tallahassee's nerves at time.

The two do make one mistake when they are hoodwinked by a pair of young female grifters (Emma Stone, Abigail Breslin), but they eventually find them and the four form an uneasy resistance squad.

Since the release of Zombieland last year, the cameo by Bill Murray was one of the movie industry's worst-kept secrets, but thankfully if it was leaked what his cameo entailed, I missed it, and it is such a hilarious joy, I'm not ruining it for anyone else who doesn't know.

You would think by this point zombie comedies would have run dry in terms of gags that elicit laughs and funny, surprise moments, but Zombieland produces more than enough to make watching it worthwhile. Now if we could only get some of these zombies to take out this glut of vampires.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Harrelson, Murray

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Centennial Tributes: Akira Kurosawa

By Edward Copeland

When Akira Kurosawa received his honorary Academy Award at the ceremony 20 years ago, nearly blind, he said in his acceptance speech that he still had a lot to learn about cinema. Imagine the reaction of myself and a friend who were watching as this master of the medium, then 80 years old, said he was still a student while two 21-year-olds who still harbored movie dreams had yet to film a frame of anything. Originally setting out to be a painter, frequent visits to Western movies with his father turned Kurosawa's thoughts to cinema. Today, Kurosawa would have turned 100 and he left behind an amazing body of work, such a prolific body of work that try as I may, I certainly haven't seen it all, but I'll try to provide a tour of as many of them as I can. I wanted to watch what is available of his work, but I simply ran out of time, so the only one from the 1940s I've seen is Stray Dog (which didn't even reach the U.S. until 1963). I also didn't get to revisit all of his films that I wanted to or attempt to see the versions made in other countries such as The Magnificent Seven or based on one of his screenplays such as 1985's Runaway Train.

You know if you've seen Stray Dog simply from the unforgettable image that Kurosawa places beneath the opening credits: a panting dog, tongue lapping furiously to indicate the heat of the day as Toshiro Mifune's police detective character does his best imitation of hard-boiled voiceover narration to begin this tale of a cop in search of his weapon, stolen from him while riding a streetcar. In addition to the striking opening shot, it also has Kurosawa using the image he loved so much in his next film, Rashomon, aiming the camera directly at the sun, a shot that wowed Robert Altman so much he tried to copy it in his early TV work. The film has many things you don't expect in a Kurosawa film: dancing girls, baseball games. There is a great suspense sequence involving a hotel pay phone, a phonograph and two locations. It's slightly silly how they keep counting down the bullets left in the stolen gun as if no new ammunition could be obtained, but otherwise it's a fairly suspenseful, unusual film of the Kurosawa canon.

The first Kurosawa feature to really make a splash in the U.S. asks a basic question, "What is truth?" In an introduction to the Criterion Collection DVD, Robert Altman calls the film "the most interesting of Kurosawa's films" along with Throne of Blood and a big influence on his own career. As Dr. Gregory House is fond of saying, "Everybody lies" and in Rashomon, everything is true and nothing is true at the same time as a man seeking respite from the rain hears the many versions of the truth behind a samurai's brutal death and the sexual assault of his wife. Even by film's end, we don't know for certain what happened, but Kurosawa still manages in his small way to reassure us of faith in mankind. The film also is fleet and efficient, quite a departure from the epic lengths that will mark most of the rest of Kurosawa's filmography. Since the Oscars hadn't established a foreign language category yet, the board of governors voted it an honorary Oscar.

Unlike Kurosawa's later takes on Shakespeare tales, where he transfers them to feudal times in Japan, he adapts Dostoyevsky's novel to post-war Japan and makes the title character a convicted war criminal who got a reprieve from a U.S. death sentence but because of terrible shock and what he calls "epileptic dementia," becomes an "idiot." While, as you would expect from Kurosawa, there are some striking images, it hardly ranks as one of his most successful films. In the beginning, it is literal exposition — written on the screen, explaining that goodness and idiocy are often equated and this story tells of the destruction of a pure soul by a faithless world. So, if you didn't know the basics of the tale, you'd have to wade through nearly three hours of uneven pacing and often over-the-top acting to get to the finish. It all comes off very mannered, sapping the tale of the humanity it desperately needs.

When I compiled my top 100 films of all time back in 2007, I ended up having two films titled To Live on it: Zhang Yimou's and Kurosawa's, which is better known by its Japanese name, Ikiru. Perhaps it's my own more frequent focus on mortality, but each time I watch Ikiru, I find that it becomes closer to being my favorite Kurosawa over the more rousing Seven Samurai. Takashi Shimura gives a touching performance as Watanabe, the sad, beaten bureaucrat who finds new purpose when he learns he's dying of stomach cancer and chooses not to leave this world without leaving a positive mark on it. It's an uphill struggle, exemplified by a wonderful sequence as citizens trying to solve a cesspool problem get shuffled from department to department without any answers or resolution. Watanabe tries to fight his illness to overcome the roadblocks, uncaring children and the world in general to renew his faith in life before there's none of his left. He's wonderful and so is the film.

However, no matter how much I love Ikiru, once I see Seven Samurai again, I'm instantly back in its camp. All films this long should be able to hold their length as this rollicking adventure tale does. Each time I see it, it transfixes me from beginning to end. Hacks such as Michael Bay should look to a film such as Seven Samurai and see how much more important character is to a great action-adventure film than stunts, explosions and special effects. It's amazing that with such a large cast, not just of the title samurai but of the farmers they are defending as well, the actors and Kurosawa develop so many distinct and worthy portraits. Granted, the running time helps, but the characters are established rather quickly from Takashi Shimura (unrecognizable from his role as the dying bureaucrat in Ikiru) as the lead samurai organizing the mission to the great Toshiro Mifune as Kikuchiyo, a reckless samurai haunted by his past as a farmer's son. There is even Kamatari Fujiwara as Manzo, one of the farmers, and Fujiwara has a mug that was made for movies. Full of action, humor, sadness, a bit of romance and plenty of heart, its influence on so many films that have come since is incalculable. Mifune and Shimura both received British Academy Award nominations as did the film and the movie picked up the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

Kurosawa's interest in the literature of the West finally led him to The Bard in this Japanese take on MacBeth. The story adheres fairly closely to the outlines of the Scottish play with Mifune taking the role of Washizu, a lord's faithful warrior who takes a spirit's prophecy and the evil prodding of his wife Asaji (a frightening performance by Isuzu Yamada) to ignore his inner morality and begin a bloody rise to power. Mifune gives another great, distinct performance and the images are striking as the forest surrounding the fortress to bring about Washizu's inevitable downfall. On his intro to Rashomon, Altman said this was his other favorite Kurosawa and while I wouldn't go that far, it is a great one.

It isn't that often that you can compare the takes of two masters of the cinema on the same classic work, in this case Russian author Maxim Gorky's play The Lower Depths. The original play told of the Russian underclass seeking refuge in a shelter during a harsh winter and a better spring, trying to deceive themselves as to the bleakness of their lives and doing what needs to be done to survive, engaging in romantic nonsense and other play while avoiding the upper class who find them a nuisance. The great French director Jean Renoir brought the play to the screen first in 1936, changing the setting to France and starring the great Jean Gabin. While not as awe inspiring as Renoir's greatest works, it's still good. Two other film versions were made before Kurosawa tackled the play in a 1957 version, moving the story to mid-19th century Japan and placing Mifune in the Gabin role. While I've not seen the original Gorky play, what I've read seems to indicate that Kurosawa's version seems more faithful to the play but as films, I did prefer the Renoir version. The Criterion Collection did film buffs an invaluable service by packaging both directors' versions in a single DVD set, so you may judge for yourself.

Certainly, most film buffs already know that the inspiration for C-3PO and R2-D2 can be found here, not as droids, but as bumbling would-be thieves in this fun Kurosawa lark that George Lucas freely credits as a major inspiration for Star Wars. A princess is trapped in enemy territory and dependent on these two unlikely heroes and a renowned general to make it back to safe ground to restore her shattered clan. Jonathan plans to write on this film in more depth later this year, so I'm being skimpy here but it's worth noting that this was Kurosawa's first film in widescreen.

The Bad Sleep Well, like many Kurosawa efforts, is too long, but it is quite good telling the story of a man (Toshiro Mifune) determined to bring down corrupt bureaucrats and corporate bosses for reasons that aren't spelled out initially. It's always interesting to see a Kurosawa film that is set in the time in which it was released, and The Bad Sleep Well is a good example of a non-period piece from him, even if it's not quite up to the level of something truly great like Ikiru. It wouldn't be fair to delve too much into the story for those who may want to see it eventually, but then this film aspires to being much more than just a simple revenge tale, exploring various issues of guilt, justice and the risk of becoming what you hate in the single-minded pursuit of vengeance. The Criterion print (the only way to see it: Beware bad prints with awful subtitle translations) presents the film in crisp, clear images, showing some of Kurosawa's best technical work and cinematography.

While Kurosawa was influenced greatly by the West, he probably sent as much inspiration the other way and this incredibly entertaining tale provides ample evidence of that as Mifune plays a nameless samurai who comes to a town terrorized by two feuding criminal gangs and plays them against each other to make it a place worth living again. Sergio Leone transferred the tale to American West in A Fistful of Dollars and transformed Mifune's samurai into Clint Eastwood's Man with No Name. Mifune is an absolute stoic riot as the town's rescuer and while Leone's trilogy is fantastic, it's hard not to love the Japanese version even more. Mifune received a well-deserved best actor prize at the Venice Film Festival.

Yojimbo was such a success that it spawned a sequel, Sanjuro. While Mifune and the movie is great fun, it isn't the equal of the original. Also, while Yojimbo and Leone's Fistful of Dollars shared many similarities, Leone's No Name Trilogy went in its own direction and Sanjuro and For a Few Dollars More have next to nothing in common (and there isn't a third Kurosawa in the series). This time, Mifune's samurai is caught between sparring officials instead of brawling criminal gangs. For fans of gore, the film's climax is a must-see in terms of blood-splattering goodness, but pay attention to the lengthy shot of stillness and silence that precedes it as well.

Of all his ventures into "modern" crime and suspense tales, High and Low by far is his most successful and compelling as far as I'm concerned, deftly combining the worlds of corporate intrigue and family life with deeper moral questions. Again, he turns to Mifune as a successful executive who finally has achieved the means to buy out a company at the same time kidnappers snatch his son, demanding a ransom roughly equal to the same amount needed for his business deal. However, there is an even bigger hitch: the kidnappers took the wrong boy, grabbing the son of Mifune's chauffeur instead. Everything clicks here, from the police procedural to the internal conflicts and office politics. It's a wonder.

It isn't unusual to find a lengthy Akira Kurosawa film, but it is unusual to find one (for me at least) that I didn't find myself compelled to finish. Given that, under normal circumstances, I would have left it out as one of his works that I failed to see, but since it is such a pivotal work in his career, its presence demands remarks. It was the last time, after 16 films spanning from 1948 to 1965, that Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune worked together. There have been many great actor-director teams in the history of film: John Ford and John Wayne, Robert De Niro and Martin Scorsese, James Stewart with Anthony Mann or Frank Capra or Alfred Hitchcock. Still, I'd argue that none match the achievements or output that came out of the Kurosawa-Mifune collaboration. It spawned time periods, genres and most always proved a success. Red Beard, with Mifune as an honorable older doctor at a charity hospital in the 19th century teaching a young doctor life lessons, for me at least, didn't end the team on a high note, but it didn't diminish the Kurosawa/Mifune team's greatness either. For their last teaming, Mifune and Kurosawa each received separate awards at Venice. I wish time and circumstances had allowed me to revisit this film again to its conclusion.

Following the release of Red Beard in 1965, Kurosawa had completed 23 films in roughly 22 years and earned international acclaim. Unfortunately, his career as a filmmaker was about to hit some real bumps in the road. Having felt he'd accomplished all he wanted to in black and white, Kurosawa was ready to film in color and produced the script for The Runaway Train, which he envisioned as a 70mm, Technicolor action extravaganza filmed in America. He secured American investors, but disagreements over the approach eventually scuttled the plans for the film. The script was eventually filmed by Andrei Konchalovsky in 1985 and earned Jon Voight and Eric Roberts both Oscar nominations. Next, Kurosawa was lured into helming the Japanese half of the planned U.S.-Japanese co-production on World War II, Tora! Tora! Tora! Despite the building of some amazing sets, Kurosawa was a bit at sea without the aid of his usual crew and communication problems with the crew he was given eventually led to his dismissal from the project. To make matters worse, rumors spread through tabloids that Kurosawa had suffered a nervous breakdown, putting future work in jeopardy. He had to get a new project off the ground, finished on time and fast. A little acclaim wouldn't hurt either.

So, this became Kurosawa's first color film. It's also the only film I watched for the first time while preparing this piece. Based on a series of short stories, Dodes'ka-den is unlike any other Kurosawa film I can think of. In a way, it reminded me of his version of Robert Altman's Short Cuts, only 23 years before that film's birth, only instead of taking place in Los Angeles, it's set among the denizens of an urban shantytown. Some characters' paths cross, others don't. The film doesn't add up to a lot, but it's fascinating to watch. It did receive an Oscar nomination as best foreign language film, but it still took another five years for Kurosawa to get a film made and this time he had to go to Russia to do it.

It seems weird to think that a Kurosawa film took an Oscar for foreign language film for the Soviet Union and was shot in the Russian language, but that's where Dersu Uzala was filmed and where Kurosawa had to go to get a film made. I wish I could say I enjoyed the film as much as the Academy did. It tells the tale of the title character, who lives in the Mongolian/Siberian countryside, when he comes across a Russian exploration party and regales them with tales of his life and his hunting skills, even saving a captain's life at one point. The grateful captain takes Dersu Uzala back to the city, but metropolitan life isn't for him and he eventually returns to the frontier he knows so well. The film has its moments, but much of it bored me.

Another five years pass. As Kurosawa was entering the winter of his filmmaking career and his eyesight began to fail, financing still was difficult to achieve. An international group of financiers, including Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, got together and helped him launch Kagemusha, an epic in the spirit of some of his most famous, only with the added twist of glorious color images. The film tells the story of a three-way civil war where the head of one of the clans is slain and, in an effort to keep his death a secret, his lieutenants recruit a lookalike thief to masquerade as the fallen man. While there are many great sequences and touches, this almost seems as if it's a rough draft for what's to come next in the Kurosawa canon, a film that will turn out to be his greatest in decades. Kagemusha did mark the world community wrapping its arms around the filmmaker. It earned an Oscar nomination and a Golden Globe nomination for foreign language film, Kurosawa won best director at the BAFTAs, won foreign film at France's Cesar awards and took the Golden Palm at Cannes in addition to many other accolades around the planet.

Many great Shakespearean stage actors, when they reach a certain age, feel it's time for them to tackle King Lear. As a film director, Kurosawa felt similarly, though Ran was, as would be expected, a decidedly Japanese take on The Bard's classic. It also proved to be Kurosawa's late-inning epic masterpiece and the first time I ever had the opportunity to see a Kurosawa film in a commercial movie theater. Despite its length, it was a spellbinding experience. Rewatching it now, it remains one. Of course, some changes had to be made for the Japanese version. Instead of Lear's three daughters, Lord Hidetora Ichimonji (Tatsuya Nakadai) has three sons, two of whom are more than eager to betray him when he announces his attention to abdicate and let the next generation run the show. Kurosawa even tosses in a little bit of Lady MacBeth in the form of Lady

Kaede (Mieko Harada), an evil, manipulative wife of one of the sons who is so bad she'd make the worst femme fatale in any film noir quake in her heels. This beautiful film boasts vibrant colors, vivid images and luscious costumes. Due to the always messy rules for the Oscar for foreign language film, it was ineligible, but it did win for costumes and earned nominations for art direction and cinematography and gave Kurosawa his only Oscar nomination for best director ever. Among his competition was John Huston, nominated for his penultimate film, Prizzi's Honor. With two of the greatest film directors of all time in the Oscar audience (this is back when the broadcast acknowledged and honored film history), the Academy wasn't about to waste the opportunity to put them on stage to present an award. They even added the non-nominated Billy Wilder and the trio of master filmmakers presented the award for best picture. Those were the days of Oscar shows that were about film, not ratings and teenyboppers.

Kaede (Mieko Harada), an evil, manipulative wife of one of the sons who is so bad she'd make the worst femme fatale in any film noir quake in her heels. This beautiful film boasts vibrant colors, vivid images and luscious costumes. Due to the always messy rules for the Oscar for foreign language film, it was ineligible, but it did win for costumes and earned nominations for art direction and cinematography and gave Kurosawa his only Oscar nomination for best director ever. Among his competition was John Huston, nominated for his penultimate film, Prizzi's Honor. With two of the greatest film directors of all time in the Oscar audience (this is back when the broadcast acknowledged and honored film history), the Academy wasn't about to waste the opportunity to put them on stage to present an award. They even added the non-nominated Billy Wilder and the trio of master filmmakers presented the award for best picture. Those were the days of Oscar shows that were about film, not ratings and teenyboppers.

To me, whether it be by multiple filmmakers or a singular genius such as Kurosawa, a film made up of vignettes always ends up being a crapshoot. Inevitably, some segments will turn out to be more compelling than others and as a result, the film will fail to end up forming a satisfying, cohesive unit and that's what happened here, despite some truly striking images and the odd fun of seeing Martin Scorsese pop up portraying Vincent van Gogh.

Kurosawa's final feature to receive a timely release in the United States had a subject matter that should have made it a riveting, personal tale, dealing with the lingering effects of Japanese families after the dropping of the atomic bombs that ended World War II. However, the product turned out muddled and was not helped in the least by the insertion of Richard Gere as a half-Japanese American seeking out his Japanese relatives for the first time. It could have been something great and I imagine it's something that Kurosawa had long wanted to tackle (it had been previewed in a way in one of the segments of his previous film Dreams), but the aging master and his failing eyesight couldn't pull this one off.

Originally released in 1993, it didn't show in the U.S. until 1998 and didn't get a theatrical release, albeit a cursory one, until 2000, two years after the legendary director had died. While it does have nice moments and visuals you'd expect from Kurosawa, this quiet but overlong film plays like most of his post-Ran movies: As a lesser effort. When compared to Kurosawa's past works, it's definitely a more forgettable effort. The simple tale begins with the retirement of a much-loved professor (Tatsuo Matsumura) who quits teaching to concentrate on writing during the middle of World War II, only to see his home destroyed during a bombing raid. His ever-faithful students set out to celebrate the man's birthday each year with a special event where he always shouts back, "Madadayo," which translates to "Not yet," meaning he wasn't ready to die. It's hard not to read Kurosawa's own thoughts on mortality into that aspect of the story, but unfortunately there isn't much more to the film, including a sequence that seems to go on forever concerning the professor's lost cat. As director's swan songs go, Madadayo doesn't really cut it and you're best sticking to the master's earlier films.

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Capra, Coppola, De Niro, Eastwood, Hitchcock, Huston, J. Stewart, John Ford, Leone, Lucas, Mifune, Oscars, Renoir, Scorsese, Shakespeare, Star Wars, Wayne, Wilder, Zhang Yimou

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Toshiro Mifune: an appreciation

By Edward Copeland

The first time I ever saw Toshiro Mifune in a movie was when I was a child and my dad took me to see the World War II behemoth Midway "in Sensurround." I have little memory of my reaction to his portrayal of the Japanese admiral other than I knew he was on a ship with Arnold from Happy Days. Later, I'd see him again as another member of the WWII Japanese navy in Steven Spielberg's bloated comedy 1941. Eventually, I did see Mifune at his best, in his many collaborations with director Akira Kurosawa. Revisiting so many of those films in a short time span for today's centennial of Kurosawa's birth, I've truly come away amazed at Mifune's range and am asking myself, "Is Toshiro Mifune the greatest film actor of all time?"

As the thought crossed my mind at how underappreciated Mifune's versatility as an actor has been, it reminded me of another actor with a similar reputation who recently received his overdue Oscar reward for Crazy Heart, Jeff Bridges. As I checked Mifune's filmography, to see if by chance there were any other non-Kurosawas that I had seen Mifune in, of all things, the only other title turned out to be the underrated Jeff Bridges gem Winter Kills, though it's been a long time since I've seen it and I can't recall Mifune's role in it.

I wish I'd seen more of Mifune's non-Kurosawa work, if only to reassure myself that the director didn't have some special gift for bringing out the very best in Mifune, but I find that very hard to believe. The vast differences in the roles Mifune played for Kurosawa definitely indicate an actor of great talent, not merely a director who knew how to coax the best out of his performers.

It didn't matter if Mifune was in a period piece or a modern drama: He was always good and he was always different. He played many feudal warriors and samurais, but they were all distinct from one another. You don't confuse the heavily drinking scarred farmer turned samurai in Seven Samurai with the stoic, dry-witted cool operator in Yojimbo and Sanjuro. Of course, they aren't even closely related to his Japanese version of MacBeth in Throne of Blood or escaping general protecting a princess and fooling beggars in The Hidden Fortress.

That's not even to mention the distinction between the various thieves he played in film such as The Idiot, Rashomon and The Lower Depths. I haven't even mentioned his wise old doctor in Red Beard, since it's the only Kurosawa I couldn't finish, even though in what I watched of it he was quite good as well.

His modern roles were equally dissimilar from the frantic young detective trying to retrieve his stolen gun before it kills more innocent people in Stray Dog to the son of a man who committed suicide seeking revenge of the members of the corporation he holds responsible in The Bad Sleep Well to the shoe executive ready to buyout his company when kidnappers unexpectedly abduct his driver's son, believing it belongs to the executive in High and Low.

His skills, as is the case with most great actors, weren't limited to characterization or the way he used his voice, but extended to his body language, the way he'd rub his head or scratch his face, a bored yawn or, in a great bit in Sanjuro, the way he absent-mindedly traces a painted character on a wall with his finger as two ladies ramble about a peaceful plan to rescue an abducted official.

With outside events and limited time, I wasn't even able to do as thorough a review of Kurosawa's canon as I would have liked for today's centennial, but I so wish I could have explored Mifune's work in non-Kurosawa's work in other directors' films more thoroughly to see if my theory holds any water. It seems hard to declare that someone is the greatest screen actor of all time when I'm basing that judgment solely on working with a single director and there are so many other gifted performers who can make a worthy claim to that title, but I think it's worth a debate. Let the arguments begin.

Tweet

Labels: Jeff Bridges, Kurosawa, Mifune, Spielberg

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, March 20, 2010

Pedro paints a puzzle

By Edward Copeland

Early in his career, Pedro Almodóvar's best films were usually no more than entertaining trifles, funny and full of color but not much else. However, if any director has ever come close to the idea of the auteur theory, this Spanish filmmaker may be the one. Granted, each film he makes now isn't better than the one that came before it but since he leaped into the newer phase of his career, each subsequent work has fit into that same level of newfound maturity and fascination. That's why I'm doubly surprised that Broken Embraces didn't garner more notice than it did when it was released last year. Perhaps we have begun to take Pedro's new style and skills for granted.

While Broken Embraces doesn't reach the heights of Almodóvar's creative upsurge such as Talk to Her or All About My Mother, I do think it's his best since those, topping his fine, but marginally lesser work on Bad Education and Volver.

It also shows once again that though Woody Allen was able to secure a great, Oscar-winning performance out of Penélope Cruz in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, no one harnesses the actress's talent as well as Almodóvar does. I haven't seen Nine, but I'm willing to wager she was much more deserving of an Oscar nomination for her outstanding work in Broken Embraces than the nomination she got for Rob Marshall's misguided musical adaptation. Working in her native language, really allows her acting chops to flow and flourish, be they a comic, romantic or emotional bent or just priceless facial reactions as reflected following a sexual romp with an older lover that simultaneous shows disgust, temporary relief and then shock.

Cruz plays Magdalena, or Lena for short, in Broken Embraces, but she really is not the main character of this romantic thriller. That role goes to Lluis Homar as Mateo Blanco, a once successful film director, who still writes, though his skills have been limited by his blindness. How he became blind is just one of the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that Almodóvar is creating here which, in its own way, is his homage to Hitchcock. The score by Alberto Iglesias unmistakably apes classic Bernard Herrmann works at crucial points in the story, which leaps between different time periods as it tells its tale. The story even includes a character who in his younger days (Ruben Ochiandiano) reminded me of one out of Brian De Palma's Dressed to Kill, so Pedro could be doing an homage to an homage.

Without giving too much away, what sets the plot in motion is that Lena, whose father is dying of cancer but is evicted from a hospital, becomes mistress to a powerful magnate (Jose Luis Gomez) who arranges for her dad to be placed in a private clinic. After two years of boredom and unhappiness with the older man, Lena seeks a life of her own and auditions for one of Mateo's movies where she not only lands the part but the director's love as well.

In addition to Cruz, the entire cast is excellent, especially Blanca Portillo as Judit, Mateo's production manager. As to be expected in an Almodóvar film, it's full of colorful, vibrant images, but the amount of intrigue and suspense is a bit of a departure and he handles it well.

It's a shame more notice wasn't given upon the release of Broken Embraces, because it certainly deserved it and now that it's on DVD, it should not be missed.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Almodóvar, De Palma, Foreign, Herrmann, Hitchcock, Penélope Cruz, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

The Craic 2010

By M.A. Peel

There is a special annual festival in New York that doesn’t get as much attention as it should, The Craic, Irish for an Irish sense of the word crack meaning fun, entertainment, and good conversation. For 12 years now producers Terrence Mulligan and the Fleadh Foundation have brought Irish film (and music) to the forefront near the feast of St. Patrick. It’s where I saw the excellent Irish language film Kings last year.

This year it was Conor McPherson’s ghost story The Eclipse (which debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival last year), and a documentary on Liam Clancy from Alan Gilsenan. (I missed the Friday night documentary on Gabriel Byrne, Stories from Home.)

The rain was pelting, hard, fast, with an angry force. At the crossroads by the canal the winds swirled in powerful eddies as the banshees howled and screamed relentlessly. Those daring to cross felt nearly a solid wall of wind against them, barring their way.

No, that’s not the film. That’s my experience getting to Tribeca Cinema to see The Eclipse on Saturday in the middle of the Nor’easter.

Conor McPherson is an Irish playwright deeply connected to the mystical side of his people’s race. The Weir, Shining City, The Seafarer, Dublin Carol all have characters haunted by obvious, rational memories, but McPherson knows that which lies beneath. He brings Satan into the poker game, not some metaphor for evil, but Satan himself. It’s not a matter of belief; for McPherson the elements of the religious and supernatural simply exist. Some people are conscious of them, others aren’t.

The Eclipse is based on a short story by playwright Billy Roche, who co-wrote the film with McPherson. It’s set in the seaside town of Cobh, Cork, during a literary festival. The great Ciaran Hinds (whom I saw as Mr. Lockhart in the Broadway Seafarer) plays Michael Fahr, a widower raising two children after losing his wife to cancer who volunteers for the festival. His father-in-law (his old Seafarer colleague Jim Norton) is not happy in the nursing home Michael has put him in. And so there’s some rational haunting going on.

Michael feels a connection to an English author he’s been driving to festival venues (the glamorous Iben Hjejle) who writes ghost stories. She’s being dogged by a fool of an American author played by Aidan Quinn. A triangle of sorts, and then there are “the others.”

It’s an appealing, seductive contemporary Irish film. The dialogue is witty, the stunning scenery beautifully shot, and the soundtrack an appropriately haunting new composition from Fionnuala Ni Chiosain, think of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Requiem meets Enya. Kyrie eleison. Agnus Dei.

But it’s Ciaran who draws you in with his natural, beguiling gravitas. And as John Anderson said in Variety, “That the drunkest person in an Irish film is an American (Quinn) will have to be considered payback for what we did to Barry Fitzgerald.”

O yellow bittern! I pity your lot,

Though they say that a sot like myself is curst -

I was sober a while, but I'll drink and be wise

For I fear I should die in the end of thirst.

The documentary filmmaker Alan Gilsenan chose this Irish-language 18th century poem as the title of his intimate portrait, The Yellow Bittern: The Life and Times of Liam Clancy. It was five years in the making, with Liam on a huge sound stage, perched on a stool with his guitar and signature cap, regaling us with a lifetime of stories and clips shown on a large screen in front of him. It’s fascinating to see the threads of his life come together.

What a life it was, blessed by “the sound.” The Clancy Brothers’s singing is bracing in its perfect harmonies, exuberant in sound and spirit. Each of the brothers had a distinctive voice highlighted by particular songs. Liam’s voice was the purest, the sweetest, light and piercing.

The youngest of 11 Clancys, he was brought to New York by Diane Hamilton, the Guggenheim in hiding who went to Ireland to research and capture folk singing in 1955. Diane had met Paddy and Tom Clancy in NY, and they told her to go see their mother in Tipperary. There she met Liam, and took him on her journey to around Ireland and Scotland, and to the home of Sarah Makem, where Liam met Tommy Makem for the first time.

Liam tells the story of his involvement with Diane, and does not shy away from the later alcoholic nervous breakdown he had. It’s an honest look at the life behind the performer, the ups and the downs. And Gilesnan broadens the scope of the film to see the Clancys in relation to what was going on the in 1960s.

Even if you aren’t Irish, Liam is a good raconteur who spins a tale that draws you in. And he has some universal words of wisdom about “growing up, growing old.” Here he is with his brothers and Tommy Makem, from their 1984 reunion tour, and “The Shoals of Herring.”

Liam Clancy died on Dec. 4, 2009, the last of the quarter to leave us.

Cross posted at M.A. Peel

Labels: 10s, Documentary, Misc., Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, March 14, 2010

Peter Graves (1926-2010)

Peter Graves had a long career in film and television, but as word spreads of the actor's passing, just days shy of his 84th birthday, it seems almost inevitable that what will be cited first will be a series of his most famous lines: "Have you ever been in a Turkish prison?" "Do you like movies about gladiators?" "Have you ever seen a grown man naked?" All come courtesy of his role as Capt. Clarence Oveur in the original Airplane! They've pushed "Your mission, should you choose to accept it..." and "This tape will self destruct in ..." way down the line in Graves' list of most famous utterances.

His first notable film role was that of the rat in Billy Wilder's Stalag 17. He bounced back and forth between many western features and lots of episodic television though he did catch a part in Charles Laughton's great The Night of the Hunter, the same year he appeared in Otto Preminger's The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell.

In 1967, he created the role which really cemented his fame: Jim Phelps on Mission: Impossible, which he played until the series' end in 1973 and reprised again in an attempt to revive the series from 1988-1990.

Many TV movies and miniseries followed including a chance to play George Washington in 1979's The Rebels and a role in both The Winds of War and War and Remembrance.

Then 1980 brought Airplane! where he and other actors best known for playing it straight such as Leslie Nielsen, Robert Stack and Lloyd Bridges got to do what they do and create one of the all-time laugh riots. Graves also appeared in the decidedly mediocre sequel.

One of his longest runs came from playing himself as host of A&E's Biography from 1994-2006. Among his most notable recent TV appearances was a recurring role on 7th Heaven and a guest spot on House as an oversexed senior citizen.

Among his survivors is his older brother, actor James Arness. RIP Mr. Graves.

Tweet

Labels: House, Laughton, Nielsen, Obituary, Preminger, Television, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Say you want a revolution?

By Edward Copeland

When I wrote about Ninotchka for its anniversary last year, I titled the post Capitalism: a love story, so I gave serious thought now that I'm reviewing Michael Moore's Capitalism: A Love Story of calling it Ninotchka, but I figured too few would get the joke.

Unlike Moore's last film, Sicko, Capitalism: A Love Story has a more scattershot theme, namely the decline and fall of the American middle class due to the avarice of the richest of the rich and the politicians who enable them (or is that the other way around?) Thankfully, Moore doesn't distract himself too far afield as he has done in previous efforts such as Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11, but while everything he shows is related to the same idea that capitalism has warped into an inherent evil, the film lacks an overarching throughline to really drive the anecdotes home.

Since I'm not a particularly religious person, why aren't more religious leaders quoting the Bible passages that the clergy in the film do to show that Christianity embraced the poor, not the wealthy, especially when the wealthy have so hoodwinked the religious to be on their side over social issues? I've always known about the days when the top income tax bracket was 90 percent and how amazingly ridiculous that sounded until JFK cut it, but the rich still lived liked kings in those days and the middle class lived good lives as well with four weeks of paid vacation a year being the standard. Today, the highest incomes whine about an increase to a 39 percent tax bracket? Forgive me if I can't work up any sympathy tears for having to give back more of their million dollar bonuses. Boo-fucking-hoo.

Not that the stories aren't effective (or downright depressing) or that he doesn't find some fascinating footage (most notably FDR's call for a Second Bill of Rights), but somehow the film just doesn't quite come together. It's not that it isn't illuminating at times or that it doesn't get your ire up, but when it gets to what should be the film's inspiring climax with the victory of the laid-off workers at the Chicago window and door plant, the viewer more likely will be exhausted and depressed than inspired to join the fight to change things.

Sadly, that's how the power brokers always end up winning and the rest of us get stepped on time and time again. In the film's final scene, Moore is spreading crime scene tape around one of the many Wall Street banks that looted the American taxpayers and got richer as a result and avoided any new regulations to avoid future financial calamities that affected we poor peasants. Moore looks exhausted and even says that he can't do it anymore, it's up to us. Not exactly a rousing endnote.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Documentary

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, March 09, 2010

Old Altmans never die (or fade away)

visions of the things to be

the pains that are withheld for me

I realize and I can see...

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

By Edward Copeland

It began life as a novel by Richard Hooker, then Robert Altman transferred MASH into a movie and made his reputation. Later, Larry Gelbart transformed that film into a television comedy and made it a landmark series, adding the asterisks to the title M*A*S*H. Altman's film had its New York premiere in January 1970, but back in those days of slow, platform releases, there was no one day when it spread to the rest of the U.S. at once. The best I can find is that it was in March, so I pick today to mark the movie's 40th anniversary.

all our little joys relate

without that ever-present hate

but now I know that it's too late, and...

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

When Johnny Mandel's theme played week after week on the CBS series for 11 seasons, I often wondered what it would have been like if they'd kept Altman's son's Mike's lyrics for "Suicide Is Painless" as well. The sitcom may have taken MASH as its essential template, but they had to draw the line somewhere. (Even an iconoclastic risk taker such as Altman had to let some things from the novel go that early in his career, so we weren't treated to scenes of Elliott Gould as Trapper John dressed as Christ, flying around Korea on a cross suspended from a helicopter and signing autographs to raise money for Ho-Jon's college fund.)

Still, Altman's movie certainly broke ground as far as war movies were concerned and definitely formed the

initial portrait of what a Robert Altman film usually was like: large casts, overlapping dialogue using unusual recording techniques, largely plotless and when they worked, as they did with MASH, great films that changed the medium and that couldn't be mistaken as the work of another director. Watching MASH again for this piece, with its dizzying overheads of helicopters bringing the wounded to the 4077th, I thought of a comparison to another Altman opening for the very first time that came 23 years later: Short Cuts. Only in that instance, the helicopters weren't bearing the injured, they were spraying the injured with pesticide as part of California's battle with the Mediterranean fruit fly.

initial portrait of what a Robert Altman film usually was like: large casts, overlapping dialogue using unusual recording techniques, largely plotless and when they worked, as they did with MASH, great films that changed the medium and that couldn't be mistaken as the work of another director. Watching MASH again for this piece, with its dizzying overheads of helicopters bringing the wounded to the 4077th, I thought of a comparison to another Altman opening for the very first time that came 23 years later: Short Cuts. Only in that instance, the helicopters weren't bearing the injured, they were spraying the injured with pesticide as part of California's battle with the Mediterranean fruit fly.I'm gonna lose it anyway

The losing card I'll someday lay

so this is all I have to say.

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

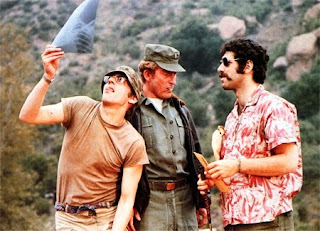

People who know the 4077th only from the TV series will certainly recognize the essential elements in the Altman movie, but they also will discover quite a few differences that follow the novel more closely. Only one cast member from the movie became a regular on the series and that was Gary Burghoff repeating his role as Radar. While the series began basically as Hawkeye (the great Donald Sutherland in the film) and Trapper

against the world, the movie had a third surgeon: Duke, played by Tom Skerritt. While many of the MASH characters share names with the M*A*S*H characters, in many areas they bear little resemblance. Hawkeye is a married man in the movie, not that it prevents his playing around, not Alan Alda's single lothario from the series. Robert Duvall's Frank Burns lives light years away from the buffoonish character Larry Linville grew tired of playing on TV. He's a strictly religious, nondrinker who is teaching Ho-Jon to learn English through the Bible. ("Were you on this religious kick at home or did you crack up over here?" Sutherland's Hawkeye asks Frank as he prays beside his cot.) That doesn't prevent Frank from falling prey his lust for Maj. Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan (Sally Kellerman). However, in the movie, Burns gets carted away early in a strait-jacket after a single prank.

against the world, the movie had a third surgeon: Duke, played by Tom Skerritt. While many of the MASH characters share names with the M*A*S*H characters, in many areas they bear little resemblance. Hawkeye is a married man in the movie, not that it prevents his playing around, not Alan Alda's single lothario from the series. Robert Duvall's Frank Burns lives light years away from the buffoonish character Larry Linville grew tired of playing on TV. He's a strictly religious, nondrinker who is teaching Ho-Jon to learn English through the Bible. ("Were you on this religious kick at home or did you crack up over here?" Sutherland's Hawkeye asks Frank as he prays beside his cot.) That doesn't prevent Frank from falling prey his lust for Maj. Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan (Sally Kellerman). However, in the movie, Burns gets carted away early in a strait-jacket after a single prank.And lay it down before I'm beat

and to another give my seat

for that's the only painless feat.

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

MASH is neither a conventional comedy nor a conventional war film and, since this a Robert Altman movie, you shouldn't expect a conventional climax either. Besides, in a film that is essentially untethered from any

plot, how could there be? So, the big finish for the film's third act is anything but obvious: It's a football game (Shades of the Marx Brothers' Horse Feathers). The 4077th gets challenged to a game by the commander of the 325th Evac. As General Hammond (G. Wood) tells Col. Henry Blake (Roger Bowen) in proposing the game, football is one of the "best gimmicks to keep the American way of life going in Asia." Wood did re-create his role as Hammond in a couple of guest appearances in the early seasons of the TV series. In an eerie coincidence, when McLean Stevenson, the sitcom's memorable Henry Blake died, the following day Bowen died. It almost was like Bowen knew that his death would get little notice unless he piggybacked on Stevenson's as the other Henry Blake. Hammond, of course, has his own ringer, so Trapper and Hawkeye set out to obtain one for their team, a neurosurgeon named Dr. Jones who was better known in his college football days as Spearchucker

plot, how could there be? So, the big finish for the film's third act is anything but obvious: It's a football game (Shades of the Marx Brothers' Horse Feathers). The 4077th gets challenged to a game by the commander of the 325th Evac. As General Hammond (G. Wood) tells Col. Henry Blake (Roger Bowen) in proposing the game, football is one of the "best gimmicks to keep the American way of life going in Asia." Wood did re-create his role as Hammond in a couple of guest appearances in the early seasons of the TV series. In an eerie coincidence, when McLean Stevenson, the sitcom's memorable Henry Blake died, the following day Bowen died. It almost was like Bowen knew that his death would get little notice unless he piggybacked on Stevenson's as the other Henry Blake. Hammond, of course, has his own ringer, so Trapper and Hawkeye set out to obtain one for their team, a neurosurgeon named Dr. Jones who was better known in his college football days as Spearchucker Jones (the film debut of Fred Williamson). They try to brush off the racist nickname by having some ask him why he's called Spearchucker and having him answer that he used to throw the javelin. While I worship Altman, one thing I never quite understood was his insistence that the TV show was racist, specifically against the Koreans, but if anyone can notice any appreciable difference betweeen the film and TV show on that count, I'd love to hear the argument. One of the biggest cheerleaders for the game is Hot Lips and if I have a problem with the film, it's the quick and inexplicable conversion of the Margaret Houlihan character. She's introduced as a no-nonsense, by-the-book Army major, constantly being humiliated by the pranksters of The Swamp (and a wonderful Oscar-

Jones (the film debut of Fred Williamson). They try to brush off the racist nickname by having some ask him why he's called Spearchucker and having him answer that he used to throw the javelin. While I worship Altman, one thing I never quite understood was his insistence that the TV show was racist, specifically against the Koreans, but if anyone can notice any appreciable difference betweeen the film and TV show on that count, I'd love to hear the argument. One of the biggest cheerleaders for the game is Hot Lips and if I have a problem with the film, it's the quick and inexplicable conversion of the Margaret Houlihan character. She's introduced as a no-nonsense, by-the-book Army major, constantly being humiliated by the pranksters of The Swamp (and a wonderful Oscar- nominated performance from Kellerman). When Hawkeye first meets her, always out to put the make on some new female flesh, he gives it to her for putting him off his lust and that she's just a regular Army clown and he's going back to his tent to drink scotch. Houlihan vents her outrage to the film's Father Mulcahy (Rene Auberjonois), known here as Dago Red, asking how someone so crass as Hawkeye could reach a position of responsibility in the Army. "He was drafted," the priest replies. When the gang exposes her shower and nudity to the camp, she has a breakdown to Henry, insisting that, "This is not a hospital, it's an insane asylum!" Then, before you know it, she's fooling around with Duke and playing cheerleader. It's odd, but it's still a minor criticism in an otherwise great film. (I'm just thinking off the top of my head, but has any great movie been turned into an almost equally great television show the way MASH was?)

nominated performance from Kellerman). When Hawkeye first meets her, always out to put the make on some new female flesh, he gives it to her for putting him off his lust and that she's just a regular Army clown and he's going back to his tent to drink scotch. Houlihan vents her outrage to the film's Father Mulcahy (Rene Auberjonois), known here as Dago Red, asking how someone so crass as Hawkeye could reach a position of responsibility in the Army. "He was drafted," the priest replies. When the gang exposes her shower and nudity to the camp, she has a breakdown to Henry, insisting that, "This is not a hospital, it's an insane asylum!" Then, before you know it, she's fooling around with Duke and playing cheerleader. It's odd, but it's still a minor criticism in an otherwise great film. (I'm just thinking off the top of my head, but has any great movie been turned into an almost equally great television show the way MASH was?)It doesn't hurt when it begins

But as it works its way on in

The pain grows stronger...watch it grin, but...

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

As I mentioned before, MASH is the first example of the Robert Altman ensemble that he'd become famous for and many of the actors who would become part of the unofficial Altman repertory company would make appearances here. Elliott Gould would follow his great work as Trapper John with similarly solid work in Altman's The Long Goodbye and California Split and would appear as himself in Nashville and The Player.

Skerritt returned to Altman for Thieves Like Us. Kellerman returned for Brewster McCloud and Ready to Wear and as herself in The Player. Duvall first appeared in Altman's Countdown and then reunited with him on The Gingerbread Man. Rene Auberjonois rejoined the director for Brewster McCloud, McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Images. David Arkin also appeared in The Long Goodbye, Nashville and Popeye. Last, but certainly not least, MASH marked the appearance of Michael Murphy who may have been the most regular of Altman regulars, appearing in McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville, Brewster McCloud, Kansas City, Countdown, That Cold Day in the Park, Tanner '88, Tanner on Tanner, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial and even episodes of TV's Combat, Kraft Suspense Theater and the 1964 TV movie Nightmare in Chicago. It also marked the film debut of Bud Cort who returned in Brewster McCloud. Surprisingly, the actor who gave the best performance in MASH never worked with Altman again. I always go back and forth as to whether or not Donald Sutherland's Hawkeye Pierce is lead or supporting but in either case, it is brilliant and yet another example of the outrage that this man has never received an Oscar nomination for anything. His little whistle as Hawkeye alone is a thing of wonder.