Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Doing that Woo-do that Woo does so well

By Edward Copeland

Far too often in Hollywood history, acclaimed directors from abroad come to the U.S. to make films and find what made the artists special disappear along with their careers. I've often wondered where John Woo has been for the past several years and now I know: He returned to Asia to make a true epic, the most expensive film ever made on that continent and broke the box office record held by Titanic in mainland China (and this has more than just special effects, it even has a script), telling a famous story of warfare dating back to 208 A.D.

Released here in a shortened version, Red Cliff was shown abroad as a two-part, nearly five-hour wonder (as well as a single, long feature). This isn't your father's John Woo, but it is a helluva comeback.

After Woo became a favorite for his Hong Kong action films such as Hard-Boiled, the studios lured him to the states where he first tried to enliven a Van Damme film (Hard Target), made Broken Arrow, got to make one really fun film (Face/Off) then got stuck in a rut of forgettable Hollywood product such as Mission: Impossible II, Windtalkers and Paycheck, which came out in 2003 and was the last I'd heard of him.

Given my limited stamina of late, at first I thought of renting the 2 hour, 28 minute version of Red Cliff released in U.S. theaters, but I heard so many raves of the two-part, international cut, that I bit the bullet and put that version in my queue. Now that I've seen it, though I wasn't able to watch it in one sitting due to time and fatigue constraints, I wonder what in the world they could have cut out. The climactic battle alone is more than 30 minutes long. I definitely made the right decision. Maybe, out of curiosity, I will check out the abridged Red Cliff someday, but I'm damn glad I didn't get introduced to it.

In Kenneth Turan's review of the shortened version in the Los Angeles Times, he said the film employed three editors, two directors of photography, 300 horses and a cast and crew that came close to 2,000. After seeing what Woo put on the screen I have to ask, is that all? The scale of Red Cliff truly astounds with all manner of combat scenes that would make Akira Kurosawa jealous if he were alive. Woo even gets to do some ancient fighting scenes I don't think Kurosawa ever got a chance to depict, unless I missed a film where he directed ancient naval warfare.

Based on some legendary books about Chinese history, Red Cliff takes place near the end of the Han dynasty when its power-hungry prime minister Cao Cao (Zhang Fengyi) looks to cement his power by squelching some rebellious warlords who stand in the way of his seizing control of territory critical to uniting the land and its people, despite the Han emperor's so-so endorsement of the plan. When Cao Cao succeeds in forcing one of the warlords, Liu Bei (You Yong), and his forces into retreat, Liu Bei's chief strategist Zhuge Liang (Takeshi Kaneshiro) realizes their only plan for success is to align with rival warlord Sun Quan (Chang Chen), forming a particularly strong bond with Sun Quan's military superstar Zhou Yu (Tony Leung, reuniting with Woo for the first time since Hard-Boiled).

It's not all a man's world though, as Zhou Yu's wife (Chi-Ling Lin) proves both a catalyst for Cao Cao's campaign and for some of the war tactics as does Sun Quan's sister (Zhao Wei), who turns out to be a most effective spy and provides the film's most touching subplot.

That's the basic outline and the rest of the film, aside from a quiet and touching moment here and there, moves swiftly from one battle to a strategy session to the next battle and back again, hardly pausing to take a breath yet still finding time to delineate characters, keep the action clear and never allowing the viewer to get lost in the nonstop melees. In fact, the planning sessions on both sides end up being some of the most fascinating parts and reminded me of a film you wouldn't readily think of in relation to an ancient war epic: the great boxing documentary When We Were Kings.

I'd never thought of boxers thinking of strategies before that film and while I've obviously always been aware of planning involved in warfare, Red Cliff's tricks somehow makes it seem fresh. Even though it was the fighting style of the particular eras, when you compare to any Edward Zwick film such as Defiance or The Last Samurai, it usually ends up being two sides marching toward each other. In Red Cliff, the weather comes into play as does the use of disease, using sunlight to your advantage and tricky subterfuge to steal weapons from the enemy during their own attacks.

Woo's camera, always fluid, turns practically liquid in Red Cliff, but never in a distracting way, smoothly soaring over gorgeous landscapes and grisly battles alike, even ending the first half with a pigeon's eye view of the path from one side's camp to the other's. If this film had been made in another era in English and produced by David O. Selznick, its scope alone would have guaranteed an Oscar sweep.

The fighting scenes also play as a throwback to an old style, with little evidence of the trendy type of martial arts that was exciting in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon but soon got tired by loads of imitators. These fierce warriors don't let a little thing such as an arrow in the chest interrupt their fighting. In a way, it reminded me of Joanne Dru in Howard Hawks' Red River, but they do much more than talk with the weapon protruding from their torso.

The performers don't get lost in the spectacle with especially fine work turned in by Zhang Fengyi and Takeshi Kaneshiro. Still, it's the production itself that provides the biggest star turns from the cinematography of Lu Yue and Zhang Li to the editing of Robert A. Ferretti, Angie Lam and Yang Hong Yu; from the production and costume design by Tim Yip to the art direction by Eddie Wong; not to mention the extensive sound, stunt and special effects teams.

Still, the greatest accolades must go to Woo for serving as ringmaster for this cinematic circus. Here's hoping Red Cliff marks the return of a great director to films worthy of his talent.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Foreign, Hawks, Kurosawa, Selznick, Woo, Zwick

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, April 26, 2010

40 years ago, phones rang, doors chimed

By Edward Copeland

On this date in 1970, the Broadway legend of Stephen Sondheim really began to be cemented as Company, the first musical that teamed Sondheim as both lyricist and composer with Hal Prince as director (though Prince had previously produced Sondheim's A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum) opened on the Great White Way.

Granted, Sondheim already was well respected for his lyrics for West Side Story and Gypsy as well as for serving as lyricist and composer for Forum, Company's look at an active bachelor named Robert (or Bobby) surrounded by the relationships of his married friends was a bit of a groundbreaker in terms of subject matter for a big Broadway musical. Some later versions even hint at his bisexuality, though he is strictly a heterosexual lothario in the show. It also began an incredible run for the Sondheim-Prince team in the 1970s. The following season brought Follies and two seasons after that A Little Night Music premiered.

As is sadly too often the case with Sondheim musicals, the score for Company proves much stronger than the show itself. In fact, the show's book by George Furth really has no plot and is more a series of skits. Still, the original production earned 14 Tony nominations and won six, including one for Furth's book.

I've personally only seen two productions of the show live: the 1995 Roundabout revival starring Boyd Gaines and a local production in Daytona Beach, Fla. Our own Josh R., not a big fan of the show, did think that John Doyle's radical rethinking of the musical in Doyle's 2006 revival made him see the show in ways he'd never imagined before. "From this point on, I don’t think I’ll ever be able to be blasé about Company again, or regard it with anything close to indifference," Josh wrote in his review.

Fortunately, Doyle's production was filmed and is available on DVD and I was able to see it that way and I wholeheartedly concur. Company isn't near the top of my favorite Sondheims, but its anniversary is worth marking as a key point in the artist's evolution as arguably the greatest gift musical theater fans have ever received. Sondheim recently turned 80 and a Broadway theater will be bearing his name, a rare honor for someone still living, but a much deserved one.

The Company score includes "The Little Things You Do Together," "Sorry-Grateful," "You Could Drive a Person Crazy," "Another Hundred People," "Getting Married Today," "Marry Me a Little" (which actually didn't join the show until later revivals) and probably the two best songs, "The Ladies Who Lunch," which originally was sung by the incomparable Elaine Stritch, and the powerful "Being Alive." Here is Raul Esparza performing the song from the 2006 John Doyle revival.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, H. Prince, Musicals, Sondheim, Theater Tribute

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Mr. Monk and the Hilarious Hooey

By M.A. Peel

I saw the revival of Ken Ludwig’s Lend Me a Tenor this weekend with Mater. The New York Times didn’t like it either in 1989 (Frank Rich) nor today (Charles Isherwood). I’m not usually a fan of farce (high or low) or slapstick, or endless double entendres or playing broad, but this show is a delight.

I got excellent orchestra seats nine rows from the stage thanks to a 50% discount code that appeared on the Monk Facebook page just as after the series ended. Thanks very much, Mr. Monk. It’s a thrill to sit close to a Broadway stage because you really feel the live energy. If you sit in the back, it’s like watching TV.

Isherwood and Rich quibble about the plot of Tenor. Kind of makes them look silly. They are SO missing the point. Let me explain it to them and you with a perfect, appropriated description from Gary Giddins (via James Wolcott): it’s “absolute hooey, but it is a hooey of master craftspeople, working together like apprentice in a Renaissance studio, each one a specialist in light or fabric or hands or eyes, held in balance by their master’s supervision. In this instance, the master was director Stanley Tucci.” (OK, Giddins was actually talking about Joan Crawford’s film Sadie McKee directed by Clarence Brown.)

Sparkling hooey isn’t about plot. It’s about ridiculous set-ups that play out in inane ways, with just a soupcon of wit. It’s actually the ensemble of pros that make for the laughter. For me, Tony Shalhoub is the master of the subtle look within the over-the-top lunacy going on around him.

Shalhoub’s impresario is a man used to giving orders and getting what he wants. It’s the control of his performance that I loved. He is a very elegant man, and you can feel the intelligence below the reaction shots. I find that very rich and appealing.

Anthony LaPaglia had the harder role, Il Stupendo. He looked less at ease in his roll than Shalhoub, although his confusion in the second act was very, very funny.

The discovery for me was the young Justin Bartha who plays Max, the nerd factotum who blossoms before our eyes. He’s in The Hangover, which I now must see, and the National Treasure series with Nicolas Cage where he plays Riley Poole. Don’t think too many of his under 30 film friends have the chops for the stage that he has.

And so I found myself laughing and laughing at stupid lines and silly moments in my own willing suspension of disbelief.

It was a beautiful day in Gotham, and this hilarious hooey shared with Mater felt like such a gift. I don’t laugh enough (with a notable exception on my recent trip to China): I’m an Ox, and so I got a of cosmic dose seriousness (with a little artistry thrown in from the Libra side). Performing art of any kind that makes people laugh is extremely important to the human condition. It literally helps to lighten our load, to counterbalance the veil of tears that is so much of our human equation.

Preston Sturges knew this. That scene at the end of Sullivan’s Travels when the convicts and churchgoers start laughing while watching the 1934 Walt Disney cartoon Playful Pluto with Mickey Mouse and Pluto is one of the great moments in cinema.

The dedication at the film’s beginning:

"To the memory of those who made us laugh: the motley mountebanks, the clowns, the buffoons, in all times and in all nations, whose efforts have lightened our burden a little, this picture is affectionately dedicated."

The film’s last line, spoken by John L. Sullivan

"There's a lot to be said for making people laugh! Did you know that's all some people have? It isn't much but it's better than nothing in this cockeyed caravan! Boy!"

Labels: Crawford, Disney, Nicolas Cage, P. Sturges, Television, Theater, Tucci

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, April 25, 2010

From the Vault: Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould

This biography of the late, controversial Canadian pianist plays as unconventionally as the pianist himself, or at

least as unconventionally as director Francois Girard makes Gould out to be since I had little knowledge of the musician before seeing this film. That hardly mattered though because using a startlingly original structure, the movie paints such a vivid portrait of Gould that I felt like I'd always known who he was.

least as unconventionally as director Francois Girard makes Gould out to be since I had little knowledge of the musician before seeing this film. That hardly mattered though because using a startlingly original structure, the movie paints such a vivid portrait of Gould that I felt like I'd always known who he was.Girard, who co-wrote the screenplay with Don McKellar, uses a style that is part documentary and part re-creation but eschews a standard chronological narrative for small vignettes that depict various aspects of Gould. Taking its structure from Bach's "The Goldberg Variations," these shorts combine into 32 mini-movies that together only run a little more than 90 minutes.

Perhaps the strongest thing the film has in its favor is Colm Feore, who plays Gould at various ages and makes Gould the individual come off sounding as great as his musical performances.

The ideas contained in the movie fascinate to such an extent that no short review can do them justice such as Gould's obsession with the notion that artists need anonymity and isolation, not adoring fans, a notion that led Gould to abandon public performances in the 1960s.

Listening to Gould talk about piano music in general, downplaying his own importance, truly provokes thought since Gould views everything as music — from the radio documentaries he develops to overheard conversations in a diner.

For film lovers, Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould may well be one of the most inspired uses of film in recent memory and it shouldn't be missed.

Tweet

Labels: 90s

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, April 24, 2010

From the Vault: Manhattan Murder Mystery

After two films that played like warmed-up leftovers (Husbands and Wives, Alice) and one failed exercise in style (Shadows and Fog), Woody Allen returns to form with an entertaining comic mystery.

Allen fuses disparate elements of his films and concocts Manhattan Murder Mystery, a joyously light romp that succeeds both on its own terms and as an homage to a classic genre.

The film marks the first screen teaming of Allen and Diane Keaton since 1979's Manhattan and they easily slip back into the comic rapport they generated in Annie Hall and other great comedies from the 1970s.

Keaton and Allen play a long-married Manhattan couple whose son has left the nest, leaving their lives with a bit less spark. Allen busies himself with his work as a book editor while Keaton toys with the idea of opening a restaurant.

Keaton soon finds a new diversion when the day after the spouses are invited to a neighbors for drinks for the first time, the wife drops dead and Keaton, aided by a newly divorced playwright friend (Alan Alda) becomes convicted that it was murder, not a heart attack, that did in the woman.

To divulge much more would ruin some of the mystery's fun, which is rather satisfying for what is essentially a light comedy. The details — disappearing bodies, etc. — come straight out of films like Hope and Crosby's Road pictures and various Abbott and Costello flicks. Allen and Keaton dive into neurotic modern takes on these character types with criminal glee.

Allen's direction moves the film briskly along and he does have some great sequences, ranging from the climax in a movie house while Lady from Shanghai plays in the background to an investigative trip to a molten steel warehouse.

Nice, quieter moments abound as well such as a speculative dinner with Allen, Keaton, Alda and Anjelica Huston, playing one of Allen's writers, and another where Huston teaches Allen how to play poker.

One demerit to Allen's direction comes from his continued misuse of hand-held cameras. While the effect doesn't jar the viewer as much as in Husband and Wives, it seems even more out of place here.

Alda and Huston lend able comic support while Keaton's funny performance is infectious, especially when combined with Allen's priceless expressions. The script, co-written by Marshall Brickman and actually predating Annie Hall, provides a higher number of one-liners than most Allen films of late.

While Manhattan Murder Mystery doesn't rank in the highest tier of Allen's films, it is by far the funniest he's made since Broadway Danny Rose.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, A. Huston, Abbott and Costello, Alda, Diane Keaton, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, April 23, 2010

Solid Laughs Serve as Strong 'Back-up' to Formula

By Liz Hunt

How times have changed.

Until the Summer of Love, a single woman having a baby was something kept a family secret. From that time, single moms went from being divorced with children to the current situation where any woman who wants a child can pretty well have one and no one cares.

The Back-up Plan takes advantage of the great number of woman, who, if they aren't married or have a steady guy, can plan to have a baby by using a sample from any sperm bank.

Zoe (Jennifer Lopez) is a woman who has reached that point. She owns a pet store and has just been inseminated by donated sperm from a bank. As she leaves the doctor's office in the pouring rain, she grabs a cab and slides into the back seat at the same time a soaked guy enters from the other side. After a crabby conversation, both get out and lose the cab.

Stan (Alex O'Loughlin) likes what he sees, Zoe is more hesitant since she already has what she wants. Days later, they meet again at a farmer's market, where Zoe learns Stan works at his family cheese farm and is selling goat cheeses. Another misfire between the two, but Stan has learned more about Zoe and finally catches her at her pet shop.

Zoe gives Stan a chance, still not mentioning her pending pregnancy. Their first date starts well but goes bad quickly in a really funny way. The rest of Zoe and Stan's story is pretty predictable with some insanely funny moments.

Stan falls for Zoe and her unborn baby and together they experience the time when her regular sexy clothes don't fit any more, her membership is a diverse and hilarious group of single mothers in a support group, shopping for baby clothes and a big surprise during an ultrasound.

Yes, The Back-up Plan is a totally formulaic romantic comedy, but its comedic set pieces are simply hilarious, making this an OK date movie, but a truly great chick flick, especially for mothers. While the first date is lovely, then funny, as the pregnancy progresses, a few scenes set new standards with what's funny to a woman.

Meg Ryan's pivotal scene in When Harry Met Sally... is topped in a make-out scene between Zoe and Stan. A scene with a woman having a water birth in a New York apartment living room in a kiddie pool sets a new standard in how hard a woman can laugh and cry at the same time. Men will laugh as well, because the woman in the tub does an amazing array of funny faces and sounds. Lopez and O'Loughlin's faces play into the scene with their varying amounts of horror and disbelief.

For the most part, The Back-up Plan succeeds on Lopez's acting. She does humor well and has picked a film that will give her movie career a boost, and perhaps launch O'Loughlin's career as a leading man.

There is a slight twist at the end, and try to stay through the credits for the outtakes. It's worth it.

Tweet

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, April 22, 2010

After 75 years, she's still alive

By Edward Copeland

Some films belong to a very exclusive club and James Whale's Bride of Frankenstein, which was released 75 years ago today, holds a membership card: sequels whose excellence actually exceeds the original.

Like a sequel to another classic horror film (though admittedly one with fewer defenders), Bride of Frankenstein resembles the path Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 would take more than 50 years later, downplaying the fright in favor of frivolity. Now, as much as I love Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, I don't mean to imply it's anywhere near the league of Bride of Frankenstein, because Whale's sequel is a masterpiece.

The humor starts in the very beginning with a funny prologue that finds Lord Byron (Gavin Gordon) marveling at an approaching storm with his friends, the Shelleys (Douglas Walton, Elsa Lanchester), and being surprised that the thunder and lightning can so frighten Mary when she produced as horrifying tale as the novel Frankenstein, even though she can't find anyone willing to publish it. Mary Shelley expresses her frustration that her book has been dismissed as merely a monster tale when she set out to tell a morality lesson of the punishment of a mortal man who chose to act as God. This leads to what would commonly be a "Last time on" summary on a television show that one rarely finds in movies. In fact, the only other sequel that springs to mind that ever did this was Superman II. (Since I originally wrote this, the second part of John Woo's Red Cliff also takes this approach.)

Lord Byron expresses regret that the story ended as it did but Mary insists that it wasn't really the end (undermining her punishment for Henry Frankenstein since he now survives the cataclysm) and she begins to

spin the tale of the sequel where the first film left off at the burning wreckage of the mill where the villagers cheer the flames, assuming the monster is dead and take an unconscious Henry (Colin Clive) back to his castle. Even though it undercuts her argument for the meddler paying for acting as God, at least he feels guilty about it. Compare that to the completely stupid ending of Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park. I never read Michael Crichton's novel, so I don't know how it ended, but it's bad enough the film version ended with what seems like an endless shot of the survivors staring at each other in a helicopter as they get away, Richard Attenborough's character didn't suffer any punishment at all. Hell, they didn't even give us a throwaway shot of a T-Rex back on the island standing and screaming as they flew away.

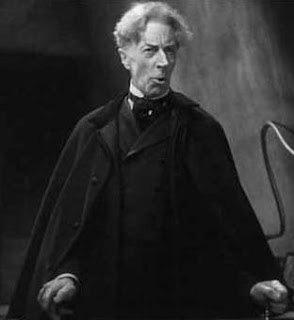

spin the tale of the sequel where the first film left off at the burning wreckage of the mill where the villagers cheer the flames, assuming the monster is dead and take an unconscious Henry (Colin Clive) back to his castle. Even though it undercuts her argument for the meddler paying for acting as God, at least he feels guilty about it. Compare that to the completely stupid ending of Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park. I never read Michael Crichton's novel, so I don't know how it ended, but it's bad enough the film version ended with what seems like an endless shot of the survivors staring at each other in a helicopter as they get away, Richard Attenborough's character didn't suffer any punishment at all. Hell, they didn't even give us a throwaway shot of a T-Rex back on the island standing and screaming as they flew away.I digress. Let's get back to discussing the good movie. While Frankenstein itself was quite a good movie, it's amazing how much more confidence Whale shows as a director in the follow-up. It moves at a breakneck pace and, like the original, is barely more than an hour long yet the viewer isn't shortchanged. Even in the credits, Whale lets his own name come out of the fog at a smaller size before revealing itself in full to the audience. Then Boris Karloff is credited solely as KARLOFF for his work and Lanchester's dual work as Mary Shelley and the bride isn't acknowledged since the bride's portrayer is depicted as a question mark, so even the credits serve as a platform for fun and experimentation.

While much of the film definitely leans to the funny side, Whale doesn't completely omit the shocks and

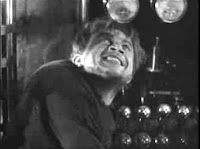

shudders moviegoers would have been expecting from the monster story, especially in the opening (helped by Franz Waxman's atmospheric and, at times, downright bouncy score). As the townspeople celebrate over the burning mill (including the great Una O'Connor as Minnie declaring that it's "the best fire ever") and the burgomaster ordering villagers to go back to their homes and relax, the parents of the young girl the monster accidentally drowned in the first film remain behind, determined to see the remains of the creature who stole the life of their little girl. Minnie even tries to convince them to let it be, but after she leaves, one wrong step plunges the grieving father into the mill wreckage. The slow appearance of the monster's hand from the shadows is one of the creepiest moments of the entire film and for Twin Peaks fans, the scene is tellingly witnessed by an owl. Still, viewers aren't left to settle in the scare mode for too long as after the monster frees himself from the wreckage and gets on the move once again, it's impossible not to laugh at how silent the previous bloodthirsty Minnie goes when she turns and sees the very not-dead creature hovering above her. O'Connor's performance provides a great deal of the comic relief in a horror film that almost survives by coming up with periods of horror relief to break up the laughs.

shudders moviegoers would have been expecting from the monster story, especially in the opening (helped by Franz Waxman's atmospheric and, at times, downright bouncy score). As the townspeople celebrate over the burning mill (including the great Una O'Connor as Minnie declaring that it's "the best fire ever") and the burgomaster ordering villagers to go back to their homes and relax, the parents of the young girl the monster accidentally drowned in the first film remain behind, determined to see the remains of the creature who stole the life of their little girl. Minnie even tries to convince them to let it be, but after she leaves, one wrong step plunges the grieving father into the mill wreckage. The slow appearance of the monster's hand from the shadows is one of the creepiest moments of the entire film and for Twin Peaks fans, the scene is tellingly witnessed by an owl. Still, viewers aren't left to settle in the scare mode for too long as after the monster frees himself from the wreckage and gets on the move once again, it's impossible not to laugh at how silent the previous bloodthirsty Minnie goes when she turns and sees the very not-dead creature hovering above her. O'Connor's performance provides a great deal of the comic relief in a horror film that almost survives by coming up with periods of horror relief to break up the laughs.In reality, Karloff's moments as the monster are the main ones that do shy away from laughs as he deepens his alternately sad and menacing performance from the first film in this one, beginning to learn rudimentary speech and to understand what he is and what his place in the world is. His self-examination, something most of the main characters undergo here save the film's new and greatest creation, Dr. Pretorius (Ernest

Thesiger), includes a moment when the monster sees his reflection for the first time in a stream. One thing I noticed upon watching the film again that I always forget is some of the Christ imagery they place upon the monster (he was raised from the dead, after all). As an angry mob recapture the monster and bind him to a large wooden log, it lacks only the crossbeam to resemble a crucifix. It's even more explicit at another point when he escapes and hides in a graveyard's mausoleum that lies beneath a large crucifix sculpture complete with Jesus. The real pathos comes in the film's most famous scene when the monster receives refuge from a kind blind hermit (O.P. Heggie), whose violin music attracts the monster to the hermit's cabin. The sweet scene, which does have some tension when the blind man unwittingly lights a cigar, turns into a tutoring session as the blind man begins to teach the monster speech and to realize, as the monster puts it, "Alone bad. Friend good." The one sad note about the scene is that, as great as it is, it is impossible now to watch it without thinking of the hysterical spoof version from Young Frankenstein with the brilliant comic duet between Peter Boyle and Gene Hackman in the classic Mel Brooks satire. Also, look for a brief appearance from John Carradine.

Thesiger), includes a moment when the monster sees his reflection for the first time in a stream. One thing I noticed upon watching the film again that I always forget is some of the Christ imagery they place upon the monster (he was raised from the dead, after all). As an angry mob recapture the monster and bind him to a large wooden log, it lacks only the crossbeam to resemble a crucifix. It's even more explicit at another point when he escapes and hides in a graveyard's mausoleum that lies beneath a large crucifix sculpture complete with Jesus. The real pathos comes in the film's most famous scene when the monster receives refuge from a kind blind hermit (O.P. Heggie), whose violin music attracts the monster to the hermit's cabin. The sweet scene, which does have some tension when the blind man unwittingly lights a cigar, turns into a tutoring session as the blind man begins to teach the monster speech and to realize, as the monster puts it, "Alone bad. Friend good." The one sad note about the scene is that, as great as it is, it is impossible now to watch it without thinking of the hysterical spoof version from Young Frankenstein with the brilliant comic duet between Peter Boyle and Gene Hackman in the classic Mel Brooks satire. Also, look for a brief appearance from John Carradine.Now the mad scientist of the first film, Henry Frankenstein, has come to see the error of his ways and is ready to resume plans to wed Elizabeth (Valerie Hobson), who is beside herself as how the events of the

first film undermined the nuptial plans. "What a terrible wedding night," Elizabeth says with more than a little understatement when Henry is brought home and first thought dead. However, without even the use of lightning, Henry comes back around and confides to Elizabeth how wrong he'd been to meddle with matters of life and death. "Perhaps death is sacred and I've profaned it," he tells her. He only wanted to give the world the secret that God is so jealous of. In order to move the story forward, even though it's been established that neither Henry nor the monster perished as moviegoers had once thought, the story better find a new mad scientist stat. They find a great creation in one Dr. Pretorius. Pretorius, especially as portrayed by Ernest Thesiger, truly is a brilliant creation from the very first moment he appears at Henry's bedside to try to lure him back into the monster-making business. Henry knows Pretorius from university where Pretorius was a doctor of philosophy until he got "booted out." Pretorius agrees that booted out is the correct term that the university forced him to leave for "knowing too much." He also emphasizes that he's a medical doctor as well. Still, Henry stays strong during Pretorius' first two visits, refusing his entreaties to see his work, but finally he caves, setting the stage for one of the funniest bits.

first film undermined the nuptial plans. "What a terrible wedding night," Elizabeth says with more than a little understatement when Henry is brought home and first thought dead. However, without even the use of lightning, Henry comes back around and confides to Elizabeth how wrong he'd been to meddle with matters of life and death. "Perhaps death is sacred and I've profaned it," he tells her. He only wanted to give the world the secret that God is so jealous of. In order to move the story forward, even though it's been established that neither Henry nor the monster perished as moviegoers had once thought, the story better find a new mad scientist stat. They find a great creation in one Dr. Pretorius. Pretorius, especially as portrayed by Ernest Thesiger, truly is a brilliant creation from the very first moment he appears at Henry's bedside to try to lure him back into the monster-making business. Henry knows Pretorius from university where Pretorius was a doctor of philosophy until he got "booted out." Pretorius agrees that booted out is the correct term that the university forced him to leave for "knowing too much." He also emphasizes that he's a medical doctor as well. Still, Henry stays strong during Pretorius' first two visits, refusing his entreaties to see his work, but finally he caves, setting the stage for one of the funniest bits.

When Pretorius unveils his creations to Henry, it is a laugh riot. The film leaves out the details of how he created them beyond growing them from cultures, but who cares? He has made miniature people that he keeps in glass bottles, but not just any people. Pretorius has flair: there's a king (and a horny king at that), a queen, an archbishop and another. The king even manages to escape his glass confines to try to get at the queen. Pretorius finds great delight in his work and the prospect of "a new world of gods and monsters," the crucial line from which Bill Condon took the title of his great 1998 biographical film of James Whale. It's never explained why if Pretorius was able to produce these marvels he'd need to team with Henry for what to me would seem to be a step backward involving graverobbing and piecing together corpses to reanimate the

dead, but as Pretorius says, "Science, like love, has her little surprises." Henry finds enough intrigue, especially with the idea of a man-made race and finding his monster a mate so they can be fruitful and multiply, that he's back in business. Pretorius recruits some condemned men (one played by everyone's favorite 1930s henchman, Dwight Frye), and even they have trepidations about the plan, expressing that graverobbing is no life for murderers and perhaps they should turn themselves in to be hung. Henry still has his qualms but Pretorius stumbles upon the good fortune of finding the escaped monster and has him hold Elizabeth as leverage to keep Henry in line. The monster, it goes without saying, finds the concept of a new friend made just for him very exciting.

dead, but as Pretorius says, "Science, like love, has her little surprises." Henry finds enough intrigue, especially with the idea of a man-made race and finding his monster a mate so they can be fruitful and multiply, that he's back in business. Pretorius recruits some condemned men (one played by everyone's favorite 1930s henchman, Dwight Frye), and even they have trepidations about the plan, expressing that graverobbing is no life for murderers and perhaps they should turn themselves in to be hung. Henry still has his qualms but Pretorius stumbles upon the good fortune of finding the escaped monster and has him hold Elizabeth as leverage to keep Henry in line. The monster, it goes without saying, finds the concept of a new friend made just for him very exciting.

So as one would-be bride becomes a prisoner, another would-be bride lies on the slab, awaiting the storm that will bring her to life and introduce her to her new after-death mate. Of course, neither romance nor arranged

marriages usually go that smoothly and as the bride awakens, with her wacky hairdo which has no rational explanation, especially since her skull seems bald while wrapped on the operating table, Elsa Lanchester returns. Her head movements resemble that of a chicken's. In fact, I couldn't help but think of Mark McKinney doing The Chicken Lady on The Kids in the Hall as I watched Lanchester's movements. The monster is giddy, the bride less so. While her look isn't nearly as horrifying as his, he doesn't look like a handsome fellow to her and she shrieks like there's no tomorrow and the poor monster finds himself rejected once again. The monster, in a rare moment of self-realization, accepts that he doesn't belong on earth and sees the worry that Henry expresses for Elizabeth through the window. The monster admits he should be dead, but allows Henry to escape before destroying the lab and taking the bride and Pretorius with him. Of course, we know there were countless Frankenstein sequels to come, so they'd write themselves out of this ending as well, but they'd never come up with a sequel with as much flair, fright and life as Whale did in this first one.

marriages usually go that smoothly and as the bride awakens, with her wacky hairdo which has no rational explanation, especially since her skull seems bald while wrapped on the operating table, Elsa Lanchester returns. Her head movements resemble that of a chicken's. In fact, I couldn't help but think of Mark McKinney doing The Chicken Lady on The Kids in the Hall as I watched Lanchester's movements. The monster is giddy, the bride less so. While her look isn't nearly as horrifying as his, he doesn't look like a handsome fellow to her and she shrieks like there's no tomorrow and the poor monster finds himself rejected once again. The monster, in a rare moment of self-realization, accepts that he doesn't belong on earth and sees the worry that Henry expresses for Elizabeth through the window. The monster admits he should be dead, but allows Henry to escape before destroying the lab and taking the bride and Pretorius with him. Of course, we know there were countless Frankenstein sequels to come, so they'd write themselves out of this ending as well, but they'd never come up with a sequel with as much flair, fright and life as Whale did in this first one.Tweet

Labels: 30s, Hackman, J. Carradine, Karloff, Mel Brooks, Movie Tributes, Sequels, Spielberg, Twin Peaks, Whale, Woo

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

From the Vault: True Romance

When Reservoir Dogs came out last year, some critics suggested writer-director Quentin Tarantino had spent too much time working in a video store. While I still admire Reservoir Dogs, those critics may have had a point based on Tarantino's screenplay for Tony Scott's film True Romance.

A strange puree of various genres and memorable plot devices, True Romance frequently is a likable though ultimately unsatisfying romp.

Christian Slater stars as Clarence, a young Detroit man who spends his life working in a comic book store until an apparent chance encounter with a woman named Alabama (Patricia Arquette) begins a strange chain reaction of events.

As the plot unfolds, so much deja vu washes over the audience that the viewer risks drowning in nostalgia. The script snatches bits from Easy Rider, bits from countless on-the-run films and a final result that plays like a poor man's Wild at Heart, including a dream Elvis (Val Kilmer) who offers Slater advice.

Scott downplays his usual glitzy style for this low-end road picture but as is usually the case, the Top Gun director fails to deliver anything substantial.

True Romance does have some merit. It contains some strong acting, especially a small role by Bronson Pinchot, James Gandolfini as a ruthless gangster named Virgil, and, in the film's most memorable scene, a memorable duet between Dennis Hopper and Christopher Walken.

On the whole, True Romance ends up being a quirky film whose positive factors can't overcome its negative attributes.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Elvis, Gandolfini, Hopper, Meg Ryan, T. Scott, Tarantino, Val Kilmer, Walken

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

NY theater flashbacks: 1995

It took me a year to get around to writing my second installment of my New York theater memories (if you missed the 1994 installment, click here). Of course many things have interfered in the interim and, quite honestly, the second installment doesn't contain shows that generated the excitement in me as a novice N.Y. theatergoer as the ones I saw in 1994 did. Still, I want all the years chronicled and as they go forward, the titles will become somewhat of a misnomer as well as they are identified by year but they really cover season, which always are split years in Broadway parlance. The first two outings just happened to actually occur in the post title years.

Tom Stoppard is one of the most clever, cerebral playwrights working today and sometimes that can be a hindrance. It had been so long since I'd seen this play, I was fortunate that the Playbill had some notes to give me a vague idea of its subject matter which spanned time periods and concerned itself with geometry and styles of English garden landscaping. I do remember the cast, who all did a good job with the very dense subject matter, and included Blair Brown, Paul Giamatti, Robert Sean Leonard and the play's standout, a relative newcomer on the scene named Billy Crudup. Even with the help of the notes though, my memories are but a fog beyond Crudup and Jennifer Dundas and the fact that my seats in the Vivian Beaumont Theatre at Lincoln Center were directly behind the late Garson Kanin and his wife Marian Seldes, whom I'd seen the year before in Edward Albee's Three Tall Women.

Shakespeare's great play lured Ralph Fiennes to Broadway and he picked up a much-deserved Tony for his effort. For me at least, it's damn hard to screw up Hamlet (though Kenneth Branagh tried with some of his stunt casting in his uncut film version). Admittedly, this Broadway production was the first time I'd ever seen the play staged and, as one would expect, cuts were made which I'm sure set purists' hair on fire. However, Fiennes' work was a wonder to me. Far too often, it seems to me that when people perform the Bard, they speak too deliberately, as if they are afraid the poetry will shatter in their mouths if they act too much. For the first time, Fiennes' Hamlet seemed to me as if he were spontaneously thinking the things he was saying, not just regurgitating memorized text. You can fake that on film sometimes, but in a live production, you can't and I was very impressed, even if the rest of the production didn't quite live up to Fiennes' standard.

When I was in elementary school, my first contact with Frank Loesser's musical How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying was the movie version with Robert Morse repeating his Tony Award-winning Broadway

role as J. Pierrepont Finch and I loved it. I'd seen it many times since, so I was anxious to see a stage version. Matthew Broderick now had the Morse role and Megan Mullally, who was new to me last year in the lame revival of Grease with Rosie O'Donnell, had the role of Rosemary that Michele Lee played in the film. For added fun, the narration of the book that gives the musical its title was recorded by none other than Walter Cronkite. The entire cast proved to be a blast from Victoria Clark as Smitty and Jeff Blumenkrantz as Bud Frump to Ron Carroll as J.B. Biggley and Jonathan Freeman as Bert Bratt. Plus, it's a show that's so entertaining with so many great songs by Loesser, that it's nearly impossible for someone to undermine it too badly, even though I thought Broderick mugged a little too much and his singing voice did leave something to be desired. The showstopper turned out to be a surprise when Lillias White, playing the secretary Miss Jones, really belted out her part of "The Brotherhood of Man" and brought the house down, despite it being a number that involved the entire company. On the celebrity sighting side, seated directly in the row behind me in the Richard Rodgers Theatre were Meat Loaf, his wife and his (I'm guessing) teenage daughter.

role as J. Pierrepont Finch and I loved it. I'd seen it many times since, so I was anxious to see a stage version. Matthew Broderick now had the Morse role and Megan Mullally, who was new to me last year in the lame revival of Grease with Rosie O'Donnell, had the role of Rosemary that Michele Lee played in the film. For added fun, the narration of the book that gives the musical its title was recorded by none other than Walter Cronkite. The entire cast proved to be a blast from Victoria Clark as Smitty and Jeff Blumenkrantz as Bud Frump to Ron Carroll as J.B. Biggley and Jonathan Freeman as Bert Bratt. Plus, it's a show that's so entertaining with so many great songs by Loesser, that it's nearly impossible for someone to undermine it too badly, even though I thought Broderick mugged a little too much and his singing voice did leave something to be desired. The showstopper turned out to be a surprise when Lillias White, playing the secretary Miss Jones, really belted out her part of "The Brotherhood of Man" and brought the house down, despite it being a number that involved the entire company. On the celebrity sighting side, seated directly in the row behind me in the Richard Rodgers Theatre were Meat Loaf, his wife and his (I'm guessing) teenage daughter.Terrence McNally's play about a group of gay men who gather together during three separate holiday weekends at a remote lake house about two hours outside of Manhattan won the Tony for best play. It's not a

bad play, but it did have the misfortune, in my mind, of following on the heels of the epic two-part Angels in America. Love! Valour! Compassion even played in the same theater that Angels did, the Walter Kerr, and its director was Joe Mantello, one of the Tony-nominated actors from Angels in America. As I mentioned in my 1994 theater flashback, Angels remains my greatest Broadway experience, so returning to the same theater and, though McNally's play's ambitions were nowhere near that of Tony Kushner's, it couldn't help but feel as if I were watching Neil Simon opening a comic take on The Seagull the week after Chekhov opened his original. Granted, McNally's play leans toward the comic, but it has its serious moments as well and it really was only the strength of its cast that lifted it for me. Justin Kirk was very good as the blind member of the group and Anthony Heald did a very good job in the role that Stephen Spinella had originally played when the show began off-Broadway at the Manhattan Theatre Club. By the time I saw the show, Nathan Lane had left the show and been replaced by Mario Cantone, probably still best known for his work on HBO's Sex and the City as Anthony, Charlotte's wedding planner friend. I wasn't familiar with his work at the time and it seemed to me that Cantone was trying too hard to do a Nathan Lane impression. The show's standout (for which he deservedly won a Tony) was John Glover in the role of twin brothers, one a bitter man, the other a sweetheart dying of AIDS. It was a wonder to see him pull off a scene with himself when he's doing it live. He was even more impressive in the film version when you saw how he modulated the characters for the new medium and was still just as great.

bad play, but it did have the misfortune, in my mind, of following on the heels of the epic two-part Angels in America. Love! Valour! Compassion even played in the same theater that Angels did, the Walter Kerr, and its director was Joe Mantello, one of the Tony-nominated actors from Angels in America. As I mentioned in my 1994 theater flashback, Angels remains my greatest Broadway experience, so returning to the same theater and, though McNally's play's ambitions were nowhere near that of Tony Kushner's, it couldn't help but feel as if I were watching Neil Simon opening a comic take on The Seagull the week after Chekhov opened his original. Granted, McNally's play leans toward the comic, but it has its serious moments as well and it really was only the strength of its cast that lifted it for me. Justin Kirk was very good as the blind member of the group and Anthony Heald did a very good job in the role that Stephen Spinella had originally played when the show began off-Broadway at the Manhattan Theatre Club. By the time I saw the show, Nathan Lane had left the show and been replaced by Mario Cantone, probably still best known for his work on HBO's Sex and the City as Anthony, Charlotte's wedding planner friend. I wasn't familiar with his work at the time and it seemed to me that Cantone was trying too hard to do a Nathan Lane impression. The show's standout (for which he deservedly won a Tony) was John Glover in the role of twin brothers, one a bitter man, the other a sweetheart dying of AIDS. It was a wonder to see him pull off a scene with himself when he's doing it live. He was even more impressive in the film version when you saw how he modulated the characters for the new medium and was still just as great.

Glenn Close owes me tickets to The Late Show With David Letterman. Let me explain. At this point, my Broadway obsession had grown beyond reason. Ignoring the fact that I disliked pretty much all things Andrew Lloyd Webber and that every instinct in my body told me that a musical made out of Billy Wilder's classic film,

one of my 10 favorite movies of all time, was a bad idea and sacrilegious, when they opened up ticket orders, which had to be done by mail, I sent one in. The minute I received my ticket and knew the date, knowing Letterman tickets also were hard to get, I wrote off for tickets to his show for that same time period and I got them. Then damn Glenn Close decided to take a vacation for that week. If I was spending that kind of money to see the damn show, I better see her, so I canceled my tickets and asked for replacement ones. Not only did that mean I lost my chance to see Letterman live, the replacement ticket they sent me was for summer, once Betty Buckley had replaced her as Norma in the show. To make matters worse, George Hearn also was gone and I had to sit through the god-awful show as well. At the time, I used to frequent the Playbill chat room on AOL and there would be endless debates about "Who was the best Norma?" Glenn Close? Patti LuPone? Faye Dunaway? Karen Mason? Betty Buckley? Screw them all. The best Norma still is and always will be Gloria Swanson. As far as the musical goes, have you ever seen the classic Simpsons episode "A Streetcar Named Marge?" That's what I couldn't get out of my mind because a lot of the lyrics were like that, trying to incorporate the film's classic lines into songs. She's still big/it's the pictures that got small. As for Buckley as Norma, all she really played was the vulnerability. You didn't get any sense of the manipulator, let alone the psycho. An impressive staircase does not a show make. What a waste.

one of my 10 favorite movies of all time, was a bad idea and sacrilegious, when they opened up ticket orders, which had to be done by mail, I sent one in. The minute I received my ticket and knew the date, knowing Letterman tickets also were hard to get, I wrote off for tickets to his show for that same time period and I got them. Then damn Glenn Close decided to take a vacation for that week. If I was spending that kind of money to see the damn show, I better see her, so I canceled my tickets and asked for replacement ones. Not only did that mean I lost my chance to see Letterman live, the replacement ticket they sent me was for summer, once Betty Buckley had replaced her as Norma in the show. To make matters worse, George Hearn also was gone and I had to sit through the god-awful show as well. At the time, I used to frequent the Playbill chat room on AOL and there would be endless debates about "Who was the best Norma?" Glenn Close? Patti LuPone? Faye Dunaway? Karen Mason? Betty Buckley? Screw them all. The best Norma still is and always will be Gloria Swanson. As far as the musical goes, have you ever seen the classic Simpsons episode "A Streetcar Named Marge?" That's what I couldn't get out of my mind because a lot of the lyrics were like that, trying to incorporate the film's classic lines into songs. She's still big/it's the pictures that got small. As for Buckley as Norma, all she really played was the vulnerability. You didn't get any sense of the manipulator, let alone the psycho. An impressive staircase does not a show make. What a waste.Widely considered the first modern American musical, Show Boat has long been a mainstay of musical theater since 1927 with its book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein but music by Jerome Kern prior to his more famous

pairing with Richard Rodgers. While I was more than familiar with the many famous songs from the show, I'd never seen it staged and hadn't even seen a film version. When I read that director Hal Prince had done some tinkering with the book to modernize it even further, I guess I was thinking even more broadly than anyone else. With the character of Julie (well-played by Lonette McKee), a light-skinned African-American passing for white, I kept expecting the revelation that Cap'n Andy, the owner of the title Show Boat, would turn out to be her father, but the show wasn't that far ahead of its time. Staged in the cavern that is the Gershwin Theatre, the talented cast did their best to overcome the hurdles of such a mammoth room. Unfortunately, Prince directs the show as if he wants to make sure you know it has a director. It always was busy to the point that you weren't sure where to look. Some of the montages to cover the passage of time truly were impressive, but much of it was just too frenetic so it was a relief when it slowed down and allowed its cast to sing its great songs. It also was no way to use the unique talent that is Elaine Stritch. In another celebrity sighting, the still alive-and-kicking (then anyway) Sylvia Sidney was in the audience.

pairing with Richard Rodgers. While I was more than familiar with the many famous songs from the show, I'd never seen it staged and hadn't even seen a film version. When I read that director Hal Prince had done some tinkering with the book to modernize it even further, I guess I was thinking even more broadly than anyone else. With the character of Julie (well-played by Lonette McKee), a light-skinned African-American passing for white, I kept expecting the revelation that Cap'n Andy, the owner of the title Show Boat, would turn out to be her father, but the show wasn't that far ahead of its time. Staged in the cavern that is the Gershwin Theatre, the talented cast did their best to overcome the hurdles of such a mammoth room. Unfortunately, Prince directs the show as if he wants to make sure you know it has a director. It always was busy to the point that you weren't sure where to look. Some of the montages to cover the passage of time truly were impressive, but much of it was just too frenetic so it was a relief when it slowed down and allowed its cast to sing its great songs. It also was no way to use the unique talent that is Elaine Stritch. In another celebrity sighting, the still alive-and-kicking (then anyway) Sylvia Sidney was in the audience.

Who would think that the most satisfying theater experience I would have in this series of flashbacks would come in the revival of a 1947 play based on an 1880 Henry James novel and best known for its 1949 film

version, but that was indeed the case in 1995. Granted, a great deal of the credit for how wonderful a night of theater The Heiress turned out to be belongs to Cherry Jones in the title role, but the entire cast shone and the play held up well. Jones won a Tony for her work as did Frances Sternhagen as her aunt and both prizes were very much deserved in this Lincoln Center production that played at the Cort Theatre and also starred Donald Moffat and Michael Cumpsty. Praise needs to be given to Gerald Gutierrez's inspired direction as well. (He also won a Tony for his work, a prize he'd win again the following year for an even greater revival.) It seems funny that when I think of Jones, this is what I think of first while nowadays, what first comes to mind for most people is the president on TV's 24. If they'd seen Jones here, that wouldn't be the case. She'd make them forget Olivia de Havilland as well: Her work as the targeted spinster was that strong; it's forever seared in my memory. As for Sternhagen, as great as she was in the play, part of her was still Cliff's mom on Cheers to me, with some left over as Charlotte's awful mother-in-law Bunny on Sex and the City.

version, but that was indeed the case in 1995. Granted, a great deal of the credit for how wonderful a night of theater The Heiress turned out to be belongs to Cherry Jones in the title role, but the entire cast shone and the play held up well. Jones won a Tony for her work as did Frances Sternhagen as her aunt and both prizes were very much deserved in this Lincoln Center production that played at the Cort Theatre and also starred Donald Moffat and Michael Cumpsty. Praise needs to be given to Gerald Gutierrez's inspired direction as well. (He also won a Tony for his work, a prize he'd win again the following year for an even greater revival.) It seems funny that when I think of Jones, this is what I think of first while nowadays, what first comes to mind for most people is the president on TV's 24. If they'd seen Jones here, that wouldn't be the case. She'd make them forget Olivia de Havilland as well: Her work as the targeted spinster was that strong; it's forever seared in my memory. As for Sternhagen, as great as she was in the play, part of her was still Cliff's mom on Cheers to me, with some left over as Charlotte's awful mother-in-law Bunny on Sex and the City.

The final play I took in for 1995 (or at least 1995 as far as this piece goes) was my only visit to off-Broadway for this year and it was a trip to the Manhattan Theatre Club at City Center to see A.R. Gurney's comedy about a romantic triangle between a husband (John Cunningham), his wife (Mariette Hartley) and his dog (Sarah Jessica Parker). Yes, Parker played a dog and this would seem, even if I were mean-spirited, an appropriate place to insert some sort of South Park joke. The play was very funny and Parker did play the bitch very well and you would think the gimmick of an actress pretending to be a dog would grow old after awhile, but Gurney and the rest of the cast managed to make it work for the entire evening. That doesn't mean Sylvia isn't a lightweight play, but I've certainly had worse nights at the theater. The real find of the evening though and the show's highlight was the least well-known member of the cast: Derek Smith. Smith played three roles, two of which were women, and he was an absolute riot. I would later to get to see him in other plays and it wasn't a fluke: Smith was a true comic acting find. Overall, my theatergoing experiences certainly were a letdown compared to 1994, but it didn't dim my enthusiasm. What's more, I was still traveling to New York from the middle of the country, which cut down on what I could see. However in the next year, I would move to Florida during the 1995-96 season, making N.Y. jaunts much easier, much more frequent and begin to spiral out of control. Hopefully, it won't take me a year to write about that year.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Branagh, de Havilland, Dunaway, Frank Loesser, Giamatti, Glenn Close, Gloria Swanson, Hammerstein, HBO, Letterman, Matthew Broderick, Neil Simon, Ralph Fiennes, Rodgers, Shakespeare, Stoppard, The Simpsons, Theater, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

I'm so tired

By Edward Copeland

As most readers know, either through references here or on Facebook, I am a bedridden man. I don't get to see first-run (or any really) films in a theater anymore. Because of other health situations in my family, I also have caregivers here with me 11 hours a day, 7 days a week, which doesn't interfere much with writing, but does with watching.

On top of that, a variety of concerns have made the ever-growing list of contributors in the left-hand column unable to pitch in so, though ideally I'd love to have at least one original post Monday-Friday, there are more and more blank days and I fear more are to come. New mysterious pains are hitting me and I find myself wanting to do nothing more than sleep when I can, further blocking my ability to watch things that I can then write about.

That's not even mentioning that I wanted to expand my contributors in the first place to free some time to work on a book while I still could. I'm coming close to a breaking point. The short reviews I manage to get out I know aren't of the quality I used to be able to do and the longer pieces I try to spend some time on aren't coming off much better. I'm starting to question the point.

Still, with the dark turn my life has taken over the past two years, this blog really is the only thing that keeps me going. Sure, I wish I got more reader comments, but what blogger doesn't? What worries me more is that my ego recognizes the decline in my own work and when I do produce something I'm proud of, it barely registers much more in the way of feedback than the posts I feel are just throwaway fillers.

As I try to gather more and more contributors to help me out, something difficult to do since this is a nonprofit place and no money is involved, hardships seem to be hitting everyone at once: Health problems, viruses that destroy computers, real life woes and just regular life. I know it comes off as selfishness on my part to expect this blog to mean as much to others as it does to me, but it's not an understatement to say that it really is one of the few things I have left that give me any semblance of joy.

With the new, unbearable pain hitting my legs and some other problems too disgusting to share with the blogosphere, this really is the only distraction I have left, yet all I want to do is sleep. When I sleep, at least until the pain wakes me up again, the pain is gone and outside worries such as fraudulent doctors and quickly diminishing savings, not to mention people in real life who turn out to be disappointments when they had renewed your faith in humanity, sleep turns out to be the only good. The more I sleep, the less time I have to watch anything, let alone write about them.

That doesn't even include the book I haven't worked on in months because I haven't had time or energy. I live in a strange paradox where I have nothing but time on my hands yet I don't have the time to get done anything I want to get done. It doesn't help that another birthday approaches this week and that April in general is a miserable month for me. T.S. Eliot got that one right.

This rant really serves no purpose, but if you see a dearth of new copy here, you'll know why. I need to write. I always have, but right now, I've neither the stamina nor the inspiration to do much beyond things I've already done in advance. I have the two discs of the international version of John Woo's Red Cliff sitting on my DVD player. Who knows how long it will take me to get to that or what kind of disservice it will do to the film since there is no practical way for me to watch it in one sitting.

Tweet

Labels: Misc.

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

He has his bad days

By Edward Copeland

When I heard that Werner Herzog was doing a "reimagining" of Abel Ferrara's over-the-top 1992 Harvey Keitel vehicle Bad Lieutenant starring Nicolas Cage, the last adjective I thought would enter my mind when watching it would be the one that did: conventional.

Actually, that adjective only applies to the first hour or so of The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call — New Orleans, but even with a glorious cinematic madman such as Herzog at the helm and an actor with a penchant for extremes such as Cage in the lead, this take doesn't come close to touching the 1992 version, which I was never that big a fan of to begin with.

This version is set "in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina," though it's hard to see why since aside from the opening scene where Cage's Terence McDonagh saves an inmate from a flooding jail cell and severely injures his back, it never comes up as an issue again and very little of the places the film takes place in shows signs of the disaster. It seemed particularly odd to me coming so soon after I had just watched the first three episodes of the great new HBO series Treme, which begins in New Orleans three months after Katrina.

McDonagh's heroism not only leaves him with a lifetime of back pain but earns him a promotion to lieutenant and the cravings for any sort of drug that might make the pain go away, though it seems more likely that he prefers the crack, cocaine, heroin, pot and pills just so he can act crazy as the film requires and up the ante on his gambling addiction.

While I wasn't a huge fan of Ferrara's earlier film, what made that film more worthwhile, other than Keitel's fearlessness in his go-for-broke performance, is that Keitel's bad cop started out corrupt, drug addicted and a gambling fiend. However, that film's central case, the brutal rape of young nun in a church sparks Keitel's character on a journey not only to solve her case but to seek his own redemption.

In The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call — New Orleans, the central case of the drug-related slayings of an immigrant family plays almost as an afterthought, an excuse just so McDonagh can run wild through various encounters with lowlifes and power brokers while trying to protect his prostitute girlfriend (Eva Mendes). The ridiculous ending, where somehow he bungles into solving all his problems, makes it all the more ridiculous. Cage certainly can be entertaining in the film at times, but it all adds up to a big case of "What's the point?"

The film also manages to wastes the talents of Brad Dourif as a bookie, Jennifer Coolidge as Cage's stepmom and Val Kilmer in a truly thankless role that does little more than present more evidence that his reputation of being such a pariah to work with has made him have to settle for thankless roles such as this.

Not only did this film need not be made, it is a true disappointment coming from a director of the caliber of Werner Herzog. As I sat through this, all I could picture in my head was a vulnerable, nude Harvey Keitel, arms outstretched, walking toward the camera in tears. Its not an image I particularly wanted to have, but I could relate to why he was crying.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Herzog, Keitel, Meg Ryan, Nicolas Cage, Remakes, Treme, Val Kilmer

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, April 12, 2010

A Ghost Story Without a Ghost

By Ali Arikan

In Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and The Whale, Jeff Daniels’ character glibly — and, dare I say, wrongly — dismisses A Tale of Two Cities as minor Dickens. Similarly, Rebecca, Alfred Hitchcock’s Academy Award-winning 1940 film of the Daphne Du Maurier novel, has a reputation amongst informed acolytes of the director as not being emblematic of his best work. Without fully disowning it, Hitchcock also eventually came to regard the film with slight unease. Talking to François Truffaut in 1967, he famously remarked,

“It's not a Hitchcock picture; it's a novelette, really. The story is old-fashioned; there was a whole school of feminine literature at the period; and though I’m not against it, the fact is that the story is lacking in humour.”

While it’s certainly true that Rebecca is not vintage Hitchcock (Robin Wood flat out dismissed it in his 1989 classic Hitchcock’s Films Revisited), it’s impossible not to be drawn into the spectral presence of the past in the movie’s subtext, as well as the romantic melodrama. On the surface, the film is a ghost story without a ghost. The Elizabethan façade of Manderley, the centerpiece of the de Winter country estate, harbours within it a gothic interior, where the triumphs and tragedies of the past linger behind every nook and cranny as characters find themselves haunted by menacing memories. The interiors, photographed in a wonderful black and white chiaroscuro by George Barnes (for which he won an Oscar), take a life of their own, and Hitchcock hints — with his first Hollywood budget — at the sort of technical wizardry that would come to define him in the zenith of his career.

Released 70 years ago today, Rebecca’s story is familiar to most. After a particularly bizarre whirlwind romance in Monte Carlo, a young lower-middle class girl (Joan Fontaine) marries Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier), a recently widowed English aristocrat, and goes back with him to his magnificent Cornish mansion, managed by the domineering Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson), a taciturn authoritarian of a housekeeper, who revels in tormenting the new lady of the house. The young bride soon starts to suspect that something, as they say, is rotten in the estate of Manderley, as she gets enveloped in the mystery of the house, and of what happened to the former Mrs. de Winter.

Seeing it for the first time in 15 years, and aware of just what it was that happened to Rebecca that fateful night, I noticed a few personal touches that Hitchcock weaved through the narrative. The obsession with a dead woman (and her “doppelganger”), for example, would be a motif that Hitchcock would revisit in his masterwork, Vertigo (1958). Similarly, the psycho-sexual tension between the characters would be a running theme in many of the directors’ best films (though never quite as overtly sapphic or pedophilic as here). In his 1986 book, The Films of Alfred Hitchcock, Neil Sinyard compares the relationship between the unnamed heroine and the sinister housekeeper Mrs. Danvers to that of the heroine and the housekeeper in Under Capricorn (1949), the tennis-star and the psychopath in Strangers on a Train (1951), or the thief and the traffic cop in Psycho (1960). In fact, the way Hitchcock fashions a character from Manderley itself anticipates the similar approach he would employ for the Bates Motel 20 years later (both buildings are “haunted” by the presence of a woman long gone).

Hitchcock had apparently read the original novel when it was still in galleys, and tried to buy the rights, which proved too costly for the director. They were eventually purchased by David O. Selznick, who saw in the story yet another opportunity to turn an international best seller into a major hit (in fact, the film’s release was delayed by a year to clear the way for Gone With the Wind at the 1939 Oscars — or, rather, vice versa). Soon after, Hitchcock moved to the United States, and signed a seven year contract with Selznick, under which he made three films, including Rebecca (1946's Notorious began as a Selznick project, but he sold it midway through production, and was never involved in the film creatively).

Like the marriage of the central couple in the film, the relationship between the star-producer and hot-shot director was no bed of roses. Selznick wanted to stick as closely to the novel as he possibly could (there are entire paragraphs directly lifted from the novel), interfered when flourishes of Hitchcock’s style became too overt, and eventually edited the film himself. While the eventual film does contain a few nice allusions to the director’s pre-war work (the skewed close-ups of Olivier and his interrogator during the inquest are particularly delightful), it is, nonetheless, a tightly controlled Selznick picture.

Still, though, there was one thing that neither David Selznick nor Maxim de Winter could get away with in the film: murder. In the novel, Maxim admits to his bride to having murdered Rebecca, but the inquest brings a verdict of suicide, reinforced, as in the film, by the later revelation that Rebecca was suffering from cancer and would have been dead in a few months. Hollywood Production Code at the time stipulated that a murderer must be punished at the end of a film, which caused Selznick and his writers, Joan Harrison and Robert E. Sherwood, to turn Rebecca’s death into an accident. A necessity of the time, this change, nonetheless, makes the final 20 of the film following Maxim’s confession in the cottage rather anticlimactic and undramatic.

The actors also did not get along. Olivier thought Fontaine was inexperienced and wrong for the part, a feeling Hitchcock refused to alleviate. In fact, Fontaine once said that Hitchcock deliberately created strife on the set, not least to keep the novice ill at ease:

“To be honest, Hitchcock was divisive with us. He wanted total control over me, and he seemed to relish the cast not liking one another, actor for actor, by the end of the film. Now of course this helped my performance, since I was supposed to be terrified of everyone and it gave a lot of tension to my scenes. It kept him in command and it was upheaval he wanted.”

However questionable his methods were, Hitchcock, nonetheless, managed to get the best out of his actors. Fontaine is the true revelation of the film, playing with precocious gusto a flibbertigibbet with daddy issues. Olivier is a delight to watch throughout the couple’s coquetry in Monaco, especially during the breakfast scene at the hotel where Maxim is more paternal and patronising than flirtatious, which adds to the general creepiness of the couple’s relationship. I also love that particularly symbolic earlier scene at the hotel lobby with Maxim, the embonpoint Mrs. Van Hopper (Florence Bates), and Maxim’s future wife — old money, new money, and no money. If Maxim seems uncharacteristically distant and boorish during the later scenes in Manderley, surely that’s a conscious decision on Olivier’s part. Most memorable of all, though, is Judith Anderson, who, through her stern presence and economical movements, dominates every scene she is in.

Also gripping are the weird psycho-sexual themes Hitchcock hints at, to which the censors at the time seem to have turned a blind eye. Hitchcock strongly implies a lesbian relationship between Mrs. Danvers and Rebecca: look at the way Mrs. Danvers recounts how Rebecca used to undress for bed, as she shows off the draw with her knickers, and caresses Rebecca’s diaphanous silk negligee. Later, she rubs Rebecca’s fur coat on the new Mrs. de Winter’s face, a not-so-subtle allusion to cunnilingus. As we find out more about Rebecca’s penchant for playing the field, we even sympathise with Mrs. Danvers, who seems to have been nothing but a sexual plaything for Rebecca.

In fact, as in many of Hitchcock’s later works, the women in Rebecca are treated as either gauche simpletons or manipulative harpies. The men don’t come off any better; the three male leads are a distant boor, a lackey and a blackmailer. Rebecca began production just as the Second World War broke out, and maybe this unsympathetic look at the human race was a conscious creative choice by Hitchcock. We’ll never know.

Equally captivating, if bloody weird, is the relationship between Maxim and his new wife. The former proposes to her in the shower of his hotel room; “I’m asking you to marry me you little fool,” he says, charmingly. He treats her like a child, asking her to promise him never to be 36. She takes this in her stride, with Maxim as a proxy replacement for her father. As Germaine Greer observed in a 2006 article to coincide with the film’s re-release, “She has nothing else going for her. Maxim wants to marry her - not despite the fact that she is, in his phrase, a "little fool", but because of it. When she snivels, which is often, he provides the handkerchief. He orders her about unmercifully. When she knocks over a glass of port and fusses to clean it up, he orders her to leave it, as if she were a dog sniffing excrement. Every now and then, he kisses her on the top of the head, just as she does Jasper the dog. By way of endearment, he calls her ‘you sweet child’ or ‘my good child’.” This is not a relationship between two equal partners — this is two people projecting their freakish fantasies at each other (asking his wife to wear a wrap because it’s chilly, Maxim intones, “you can’t be too careful with children”). Now I am the last person on earth to talk about relationships and such, but I’ll go out on a limb and characterise this as being really rather unhealthy.

But there is one theme that Hitchcock visits in Rebecca that he would generally shy away from in his Hollywood career (except, perhaps, in 1964's Marnie), and that is, of course, issues of class. Opening Rebecca’s monogrammed address book, the new bride is terrified to see a list of honorifics. She is suppressed both by the memory of the titular ex-Mrs. de Winter and what she considers to be her social ineptitude: her fear of inadequacy, of being unable to live up to the standards set by Rebecca the person, and Rebecca the institution. The film is as much about class struggle as it is about being haunted by the past, and the ambiguous ending makes this even more blatant. And if Rebecca is, finally, not quite the perfect marriage of form and technique, it’s most certainly not for any lack of trying.

Tweet

Labels: 40s, Dickens, Fontaine, Hitchcock, Jeff Daniels, Movie Tributes, Olivier, Oscars, Selznick, Truffaut

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, April 10, 2010

Dixie Carter (1939-2010)

Tennessee native Dixie Carter, whose feisty Southern charm was used to greatest effect in perhaps her most famous role as Julia Sugarbaker in the long-running television comedy Designing Woman, has died at 70.

Though the strongly opinionated designer will most likely be the role for which Carter is best remembered, it is far from the only work on her resume.

Her early television work include work on the soap operas The Doctors and Edge of Night. The first time I noticed her was an early effort by Linda Bloodworth-Thomason, the creator of Designing Woman, called Filthy Rich, a Dallas-spoof that first teamed Carter and Delta Burke.

She ended up being Conrad Bain's wife and Gary Coleman's stepmom in the waning days of Diff'rent Strokes. She did guest appearances on many episodic shows and following the success of Designing Woman found a minor hit in the drama Family Law starring Kathleen Quinlan, which lasted three seasons.