Monday, May 31, 2010

Treme No. 6: Shallow Water, Oh Mama

By Edward Copeland

Davis gives a colorful launch to his half silly/half serious campaign hitting the neighborhood on the back of a flatbed truck with loudspeakers, signs that say "Davis Can Save Us" and "McAlary A Desperate Man for Desperate Times as well as a bevy of strippers. He even gives a shoutout to his new friends, the gay neighbors he used to terrorize but he now has embraced since they pulled him off the street unconscious. He also sells copies of his campaign album. It's a fun beginning to a mostly fun episode. Forgive the tardiness in the recap, though actually only one episode of Treme has aired since this one, since it took a week off for the Memorial Day weekend. Still, given my unusual situation, I will have to wait until the series' conclusion to recap the season.

Delmond Lambreaux, Albert's son, takes his Crescent City Carnivale tour to Arizona where some of his fellow

players suggest some other New Orleans standards but Delmond, who resisted the whole idea of this tour in the first place, insists that they stick to the playlist. Rob Brown is fine in his role and I see his connection to the show more clearly than Sonny and Annie, who I've decided bore me to the point that I'm not going to bother to cover them anymore, but his scenes don't have the same charge than the others do. A great show such as Treme can have weak links, but I have more faith that Delmond will pay off down the line than Sonny and Annie ever will, especially now that it's turning into a rather typical melodramatic story of an abusive, drug addicted man jealous of his more talented girlfriend.

players suggest some other New Orleans standards but Delmond, who resisted the whole idea of this tour in the first place, insists that they stick to the playlist. Rob Brown is fine in his role and I see his connection to the show more clearly than Sonny and Annie, who I've decided bore me to the point that I'm not going to bother to cover them anymore, but his scenes don't have the same charge than the others do. A great show such as Treme can have weak links, but I have more faith that Delmond will pay off down the line than Sonny and Annie ever will, especially now that it's turning into a rather typical melodramatic story of an abusive, drug addicted man jealous of his more talented girlfriend.In her continued search for clues to the whereabouts of David Brooks, Toni travels to Port Arthur, Texas, where she has tracked down one of the two remaining former New Orleans cops who were on duty when David

was apprehended. The ex-officer expresses reluctance at first to cooperate but eventually admits that he did stop David for running a red light. Toni smiles a satisfied smile for making some progress and is almost prepared to leave when it dawns on her that no one is usually jailed for running a traffic light. She turns around and the ex-cop realizes she isn't done and she asks why he took him to jail for a traffic violation. The former officer says he had to because he had an outstanding warrant for failure to appear. Toni realizes the original would be lost, but wonders if the officer's carbon might be somewhere. He admits that the reason he quit the force was the eight days after the storm he spent living out of his patrol car, scavenging for food and supplies. Having had enough, he just abandoned his patrol car in Lake Charles and if the patrol car is still there, his arrest log should be as well.

was apprehended. The ex-officer expresses reluctance at first to cooperate but eventually admits that he did stop David for running a red light. Toni smiles a satisfied smile for making some progress and is almost prepared to leave when it dawns on her that no one is usually jailed for running a traffic light. She turns around and the ex-cop realizes she isn't done and she asks why he took him to jail for a traffic violation. The former officer says he had to because he had an outstanding warrant for failure to appear. Toni realizes the original would be lost, but wonders if the officer's carbon might be somewhere. He admits that the reason he quit the force was the eight days after the storm he spent living out of his patrol car, scavenging for food and supplies. Having had enough, he just abandoned his patrol car in Lake Charles and if the patrol car is still there, his arrest log should be as well.Antoine pays a visit to his former musical mentor who lost his trombone during Katrina and gives him the gift of the brand new instrument that the Japanese benefactor purchased for him. Now that he's recovered his own bone, he's more than satisfied to keep using that. The old man is reluctant at first to accept such an expensive gift, but Antoine encourages him to take it and keep moving straight ahead.

Creighton picks up his agent Carla at the airport (played by Talia Balsam, the real-life Mrs. John Slattery who plays his ex-wife on Mad Men) and he tries to beat her to the punch, certain that she's been sent because his publisher wants their advance back for the long overdue book on the 1927 flood. Actually, nothing could be further from the truth. They still want that book, but they are interested in a different kind of book. His YouTube rants have made him hot and they want to incorporate the current New Orleans plight into the story. Creighton rejects the idea and promises that they will have the manuscript in six weeks, but it will only cover the 1927 flood. Later, a still annoyed Creighton spots Sofia with one of Davis' campaign bumper stickers. At first, he can't believe it's the same guy who has been giving Sofia piano lessons, then he gets mad that Davis is turning such a serious matter as an election into a joke.

Davis, meanwhile, brings his coterie of strippers with him as he shows up to a televised candidates forum. He's disappointed to learn that the format doesn't allow him to sing one of his campaign songs, but he does prove entertaining with his campaign platform, which includes Greased Palm Sunday which will give a new meaning to transparency by televising bribes live on television. When he watches the broadcast later at a bar, he encounters a local pol who is intrigued by McAlary's unorthodox campaign and offers him some help to gain more traction. A surprised Davis asks if that means the man thinks he has a chance to win to which the pol replies, "No way."

Despite the rave reviews and usually packed houses, Desautel's, still faces financial struggles causing Janette no end of heartaches. Janette even finds herself hiding out from suppliers who are now insisting on cash payments for supplies and she knows she doesn't have enough cash to pay the employees for the week. She

asks Jacques (Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine) if he thinks, if she asked, the staff would be willing to work a week without pay in hopes of keeping the restaurant afloat. Jacques says that all she can do is ask. Kim Dickens just breaks your heart in these scenes as her passion runs into the brick wall of financial realities and how it will affect the livelihoods of people she views as family. Later, after the dinner crowd departs, Janette gathers the staff and is about to ask them the week-without-pay question, but she can't bring herself to do it. She realizes the futility of one week without pay toward solving long-term problems. She tries to be strong, but tells the staff that the restaurant has to close indefinitely. She hopes that if she can get things back in order, she'll be able to re-open soon, but if they find new work and can't return, she understands. Much later, alone at the restaurant, Janette has a glass of wine, ignores a ringing phone and exits her restaurant with her knives. Dickens' performance has been good throughout the entire run of the series, but this scene marks the best she's been, even besting anything she got to do on Deadwood.

asks Jacques (Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine) if he thinks, if she asked, the staff would be willing to work a week without pay in hopes of keeping the restaurant afloat. Jacques says that all she can do is ask. Kim Dickens just breaks your heart in these scenes as her passion runs into the brick wall of financial realities and how it will affect the livelihoods of people she views as family. Later, after the dinner crowd departs, Janette gathers the staff and is about to ask them the week-without-pay question, but she can't bring herself to do it. She realizes the futility of one week without pay toward solving long-term problems. She tries to be strong, but tells the staff that the restaurant has to close indefinitely. She hopes that if she can get things back in order, she'll be able to re-open soon, but if they find new work and can't return, she understands. Much later, alone at the restaurant, Janette has a glass of wine, ignores a ringing phone and exits her restaurant with her knives. Dickens' performance has been good throughout the entire run of the series, but this scene marks the best she's been, even besting anything she got to do on Deadwood.Even though Antoine and his "bone" have been reunited, Batiste still is finding it hard to find paying gigs and he's drowning his sorrows at a bar about it when Kermit Ruffins offers him a spot at the Mardi Gras Ball. It comes with a catch: Antoine will have to wear a tuxedo. He even manages to land a spot for his aging mentor, Nelson. When Antoine shares the news with Nelson, he tells him the catch is that both of them will have to undergo a medical checkup, though it's really just Antoine's concern for his old friend. The nurse who looks them over tells Antoine that he needs to lose weight, but she just thinks Nelson is depressed. "Ain't we all," Antoine sighs. When he gets home, he has more to be depressed about. Desiree didn't take his tux to a dry cleaner, she put it in the washing machine, so Antoine ends up at the ball as the only musician not in black tie.

Like a bloodhound hot on an escaped prisoner's trail, Toni's quest takes her to Lake Charles in pursuit of the ex-cop's patrol car. She fudges the truth, telling an officer there she's come to pick up the unit which relieves the officer who has been waiting for it to be picked up for months. Toni scrounged through the patrol car's back seat and finds what she's looking for: the carbons and proof of David Brooks' arrest. She then begins to leave, telling the officer someone will be back the next day to finally retrieve the vehicle.

The lack of housing for his tribe still is burning Albert up as he and his second chief, Franklin, sift through costumes. Albert heads out later because Delmond's tour has brought him to New Orleans so Albert goes to see him. At the club, Delmond notices his father paying more attention to people coming to wish him well than to Delmond's music. Between sets, Delmond let's his father know what he thinks about his lack of respect. Albert tells his son he can't stay for the second set. The following day, as the tribe continues to work on costumes, the councilman's aide arrives with what he thinks is good news: the councilman has secured a FEMA trailer to house the tribal member. Albert tosses him out.

Relaxing at home in Baton Rouge, LaDonna gets a call that her mother is having trouble breathing, so she's off to New Orleans wishing once again that she could convince the old woman to move to Baton Rouge. When she arrives at the hospital, she can't answer all the nurse's questions about her mother's medical history and when the nurse suggest her mom's pharmacy could help, LaDonna informs her it is closed.

Back from her Lake Charles triumph, Toni shares her good news with Creighton while Sofia comes in to show off her parade costume. She asks her mom what she is, but Toni is puzzled. After several guesses, Sofia says she's sperm. A shocked Toni asks her husband when exactly he abandoned his role as parent. Creighton explains the Krewe du Vieux centerpiece will be a mockup of Mayor Ray Nagin masturbating. Creighton offers to make Toni a costume, but she declines. She has to face the police and City Attorney with her new evidence afterward and that could make things more difficult.

We get a glimpse of where Davis McAlary sprang from as he visits his family to discuss his campaign. He comes from money. His parents are racists who do their best to hide it and are down on his platform, mainly for the class of people their son surrounds himself with, but Davis insists that the city is broke and the city is broken and someone must make a stand. One relative on his side is his fun, martini-swilling Aunt Mimi, played by the great Elizabeth Ashley, who is completely on board with her nephew's plans.

Before the parade takes place, Toni manages to get an early meeting with Assistant District Attorney Renee Dufossat and shows her the new evidence, including that the warrant David was arrested on was outdated. She proposes that the two of them make a joint motion for an emergency rehearing, but Dufossat brushes it off. Toni is appalled. Doesn't Renee care that an innocent man has been languishing in jail for six months? The ADA's hands are tied: the new policy is that there are no joint motions for emergency hearings. The outrage is enough to change Toni's mind about the parade that night and she joins her husband and daughter in costume ahead of the float of Nagin pleasuring himself beside a sign that reads "Mandatory ejaculation." Another thing written on the float pleads, "Buy us back Chirac." Despite the horrors the city has endured, the fun of Carnival has returned. My writings about Treme will too as well once the season has ended. With more than half its season over, Treme certainly has proven itself as one of the best dramas airing, but I've got the feeling this HBO drama will meet the same Emmy fate as David Simon's previous dramas, The Wire and Homicide: Life on the Street, which filmed in Baltimore. Somehow if a show doesn't base itself in New York or Los Angeles, it's looked down upon by those voters who tend to mimeograph the previous year's nominees. Hope springs eternal, but I stopped dreaming of Emmys doing the right thing a long, long time ago.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, David Simon, Deadwood, E. Ashley, HBO, John Slattery, Kim Dickens, Mad Men, The Wire, Treme, TV Recap

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

It's Real and It's Spectacular

By Jonathan Pacheco

By Jonathan Pacheco"The greatest show ever" or "overrated"? "Cynical" or "postmodern"? Whatever you choose to label Seinfeld, there's no denying its well-documented impact on television and popular culture, and 20 years after its inaugural season, the brainchild of comedians Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David remains relevant thanks to its unconventionally simple approach to the sitcom genre, its cleverness and catchiness, and its memorable fleet of characters, from the core to the fringe. Seinfeld is instantly recognizable, incessantly memorable, and downright iconic; not bad for "a show about nothing."

The project actually dates back to 1989 when its pilot, The Seinfeld Chronicles, debuted on NBC in a slightly different incarnation, with the three male leads (Jerry as himself, Jason Alexander as George, and Michael Richards as Kramer), but missing its token female, Elaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus). Feared to be "too New York," "too Jewish," and "too male," the show was passed on, but in a gutsy show of faith, network exec Rick Ludwin used part of his late-night and special events budget to fund four more episodes of the show, and almost a year after its pilot premiered, Seinfeld had its brief first season.

It began as a meek, leisurely, conversational show, feeling its way through the darkness with Seinfeld and David leading the way on all fronts (they're often referred to as "Lennon and McCartney"). Dead-set on showcasing things once thought too mundane to put on TV, scenes took their time as we watched Jerry in his apartment alone, untucking his shirt, grabbing a bowl of cereal, sitting down to watch a baseball game.... Because the show was in its infancy, it hadn't quite found its identity, so it borrowed heavily from the observational tone of Seinfeld's standup and the dialogue-heavy strategy of fellow Jewish New Yorker Woody Allen. Characters spoke "natural" dialogue in thick New York accents and Jerry always stood on deck, ready with pre-planned sarcastic one-liners. These early episodes are almost adorable in their earnestness to literally be "a show about nothing" and to stand out as quirky and unique. What thin plots they did have were simple and low-key: did Jerry misinterpret "signals" from a woman? Should Jerry move into a new apartment? How does Jerry tell Elaine he doesn't want her to move into his building? How does Jerry "break up" with a male friend? These episodes often ended with very cute punch-lines to tie things together, sometimes more cringe-worthy than endearing.

By the 3rd season, episodes began to speed up as Larry and Jerry started to get the hang of this television thing, leading to Seinfeld's watershed 4th season when the show, characters, and writers really found their voices. They discovered the perfect level of self-hatred and neurosis for George, learned Kramer could be much more than simply the clichéd hipster doofus next door, realized Elaine offered more than just her history as Jerry's ex-girlfriend, and found that Jerry's jokes worked best as clever, rapidly conjured zingers as opposed to slow, quaint observations. Possibly most importantly, Jerry, Larry, and all involved realized that a show about nothing doesn't need to be a show where characters do nothing. Celebrated episodes from this time period like "The Contest" (a bold turning point for the show, launching it into the stratosphere, and responsible for the euphemism "master of your domain"), "The Outing" (you know, the "not that there's anything wrong with it" show), "The Switch" (one of the strongest episodes of the show's entire run, paying homage to classic noir and heist films), and "The Soup Nazi" (possibly Seinfeld's most recognizable and memorable episode) gave these characters more to do at a quicker pace, developing them through their reactions to the ridiculous problems surrounding them. It's also no coincidence that Seinfeld's two strongest seasons — the 4th and the 7th — were the two seasons that featured prominent season-long plots (with the 4th season revolving around Jerry and George pitching, writing, and filming their TV show pilot, and the 7th centering on George's proposal and engagement to Susan).

When Larry David left Seinfeld as co-showrunner after Season 7 (the equivalent of Carlton Cuse or Damon Lindelof stepping down from Lost after its 4th season), Seinfeld shifted into its 3rd distinct era. While seasons 4 through 7 featured exceptionally notable writing and a fun but jaded view of the world typical of Larry David, the final two seasons truly felt more like Jerry: exceedingly silly and absurd, but meticulously planned out. Interestingly, the earlier seasons always felt like Jerry and Larry's babies, but seasons 8 and 9 felt more like Seinfeld's babies, with the show bringing on board many talented writers from other TV shows — people who knew and loved Seinfeld — and let them do their own thing, essentially creating episodes out of their collective fan fiction. (Seinfeld featured other writers for many years, but the final scripts would always make a stop at Larry and Jerry's office for final revisions. Not so in the final seasons with Larry stepping down and Jerry overloading with other responsibilities.) The show shifted from belonging to the two creators to belonging to the world of the show, a world created over seven or eight years, accumulating its own set of rules and traits. Anyone who'd been a fan of the show could tell you what a sort of Seinfeld Bible might look like: this is who the characters are, this is how they react, this is how we tie stories together, and this is what we never, ever, do. Anything else, you can pretty much get away with — and the writers did. The show became more self-aware as the new writers brought fresh perspectives to the team, and that's we ended up with episodes such as "The Betrayal" (the backward episode), "The Bizarro Jerry" (perhaps the most meta episode out of all nine seasons), and "The Chicken Roaster" (for years my favorite Seinfeld episode, full of goofiness, great lines, and fun plot connections and resolutions).

Moving along the same line of the show's style, the core characters evolved from quirky and quaint to lovable and relatable to iconic, and they grew as a group. Scene-stealing supporting characters like Newman, the Soup Nazi, and J. Peterman are remembered for their individual performances, and Kramer truly transcends the show entirely (more on that later), but it's very difficult to look at Jerry, Elaine, George, and Cosmo without identifying them as one entity. Dating back to the pilot episode, several of the weaker episodes suffered from missing a character or two, the lone exception being "The Chinese Restaurant", a classic despite not having Kramer in it at all. But generally speaking, remove any leg from this table, and it comes crashing down.

As a tangent to that, one of the reasons Jerry's apartment and Monk's, the coffee shop, became so iconic was because they were places of convergence and came to represent the show's nucleus. These were settings where all four would meet, complain, scheme, banter, bicker, muse, reflect, and bond. The masturbation contest was conceived at Monk's, and in that same booth we got George's classic marine biologist monologue to the group, while Jerry's apartment was a hub for pontificating social guidelines like breakup etiquette. ("To the victor belong the spoils.") These locations were the group.

But admittedly, Kramer lives on as the most recognized, beloved, and memorable character of the bunch, typical of the "buffoon" in comedies. (Who was more memorable in Shakespeare's As You Like It: Orlando, the romantic lead, or the court fool Touchstone?) With his trademark hair and vintage clothing, the jobless cigar-smoking ladies' man elicits a strong and immediate reaction on-sight because of his countless legendary moments, from his patented entrance to his butter shaving to his scenes as a supposed pimp. The layperson may not know much about Seinfeld but he definitely knows Cosmo Kramer, who's become a sort of archetype for the modern clown. (In a production of You Can't Take It With You, I was instructed to incorporate many elements of the K-Man into my role of Mr. DePinna. Years later, a friend of mine was directed to play Verges as Kramer in Much Ado About Nothing. I've yet to hear a director say, "Play him more like Joey Tribbiani.")

The success of the character comes from so many different factors, but one musn't underplay the impact of the professionalism of Michael Richards. Despite his silly role, he was the one on set taking his job most seriously, sometimes to a fault, and his dedication elevated his performance. He drew inspiration for his physical antics from classic and silent comedies, with so much of that style hinging on harnessing and communicating true weight — bouncing off objects that strike you, using your weight to create harder falls, conveying the heaviness of everything you carry. Richards was fearless in this respect, sacrificing himself like a workhorse running back, punishing his body just to get that extra yard. To watch him tumble across a couch, lug a real air conditioner around a parking garage, or slide down a baggage chute is to marvel at his commitment to bringing as much weight to Kramer as possible.

Larry and Jerry have said that they always had a rule of "no hugging, no learning," and I think that was a big part of Seinfeld's appeal during and after its run, ensuring that viewers would avoid the vomit-inducing "serious moments" that other sitcoms feel obligated to provide. Think of an episode of Friends; do any of us really have such blatant and sweet lesson-learning moments like they do every week on that show? Seinfeld works for the audience that cringes during these moments, recognizing that maybe some people don't want to be "learning lessons" from their sitcoms. Maybe they just want to laugh. It's not that Costanza, Seinfeld, Benes, and Kramer don't love each other, because their affection is beautifully obvious; it's that real people don't conveniently and explicitly express their feelings at the 19-minute mark. Sometimes it's enough to let your loyalty, rapport, and insults do the loving.

Keeping the "no hugging, no learning" credo in mind also helps make the show's finale highly appropriate. We can quibble about how the last episode was acted and executed, but it's hard to deny that having all four characters end up in jail, still not hugging, still no lessons learned, but still together, is nothing if not a logical and somewhat poetic ending to what we saw for nine years. (Not convinced? Go back and watch Season 4's "The Handicap Spot.") Nevertheless, many people take issue with it because the episode had that blatant finale feel, but not the patented TV series happy ending. Moreover, many elements such as the "final group vacation" and throwback to ancient jokes just felt out of place; it was almost as if every character was aware that he was in a finale. The episode was written by Larry David, who hadn't done a Seinfeld script since the Season 7 finale, and consequently this one proved to be a bit out of place with the flow and comedic groove of the ninth season. Instead of feeling like a true Seinfeld episode, it felt like someone trying to write a Seinfeld episode.

The finale did feature a few final masterstrokes, namely its ending mirroring the show's beginning, all the way back to the beginning of The Seinfeld Chronicles. As the four characters sit in a jail cell, Jerry and George repeat the first conversation we ever hear them have, bringing the show full circle (you're not the only one who can do that, Lost), and as a nice little coda, we get to see Jerry do stand-up for the show one last time, this time with an audience of prison-mates.

But in what could be the most brilliant move of all, Larry David made up for the shortcomings of the Seinfeld finale by writing a season-long plot for Curb Your Enthusiasm last year revolving around the Seinfeld cast getting back together for one more episode. David managed to make a reunion show without actually making a reunion show, instead letting it exist as merely a fictional storyline. Slyly winking at itself and even poking fun at the much-maligned finale (a running joke has characters claiming the reunion episode would make up for "screwing up" the Seinfeld ending while Larry vehemently defends it), this move ultimately gave audiences what they wanted without the awkwardness and lameness of a typical reunion show.

Seinfeld continues to live on via DVD and TBS reruns, and has aged remarkably well since it ended its run in 1998. Though the latter seasons, with lots of newer, younger writers, featured a few pop culture references that seem a little dated today (jabs at Titanic, the impending new millennium, and tentative talk of the Internet), many of the show's jokes, especially in the middle seasons, have a timeless quality because they don't focus so much on up-to-date references, but rather on lasting historical allusions, such as the most unattractive world leaders of all time, favorite explorers, the Kennedy family, and Bud Abbott. In retrospect, Seinfeld feels like it gave more to modern pop culture than it took from it. I mean, do I have to get into how many catchphrases the show has contributed or popularized? (Answer: Yes, I do. "Yadda yadda yadda," "spongeworthy," "double-dip," "shrinkage," "these pretzels are making me thirsty," "no soup for you," "the [blank] Nazi," "man-hands," "mimbo," the aforementioned "master of your domain" and "not that there's anything wrong with it" — just to name a few.)

Seinfeld's legacy with me personally, as I've written before, is about much more than its entertainment value. The show is a litmus test, something to bond over, and a way for me to relate to people. (You'll know that you and I have gotten close when I stop prefacing my jokes and references with, "There's this one Seinfeld episode".) The show helped me socialize in high school, and taped reruns and DVDs have helped put me to sleep every night for nearly 10 years. My brother and I even express moments of pride when our significant others deliver flawless Seinfeld references all on their own. Yes, I know, "no hugging, no learning," but I'm making an exception; the show is a dear, dear friend to me.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Larry David, Lost, Seinfeld, Shakespeare, TV Tribute, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, May 29, 2010

Dennis Hopper (1936-2010)

How many odd turns can one man's life and career take? There's probably no limit, but Dennis Hopper, who died at 74 after a long battle with cancer, took a lot of them: From young actor of film and TV in the 1950s to counterculture icon of the 1960s and '70s (while adding director to his resume and still working with the likes of John Wayne); from nearly unemployable because of drugs to a career comeback in the mid-1980s before frequent returns to TV. On the side, he managed to find time to be a prolific photographer, painter and sculptor. His later years also brought the strangest twist for the hippie hero: he became a Republican. Still, it's his film and TV work that will be his legacy.

An interest in acting led Hopper to the fabled Actors Studio in New York where he studied under Lee Strasberg for five years. As was the case with many of the studio's actors, much of his early work was on 1950s television, but he made his film debut with friend and fellow student James Dean in 1955's Rebel Without a

Cause. He worked again with Dean in the last of Dean's three films, Giant, in 1956. Much of his early work both on television and on film was spent in westerns including 1957's Gunfight at the O.K. Corral as Billy Clanton opposite Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster. The same year, Hopper got to be an emperor, Napoleon no less, in Irwin Allen's The Story of Mankind. For the next several years, his work was restricted mainly to television, including The Twilight Zone and The Defenders. His first crossover toward the counterculture might have occurred in 1964, when he played the title role in an episode of Petticoat Junction titled "Bobbie Jo and the Beatnik." Hopper still did plenty of westerns, appearing opposite John Wayne for the first time in 1965's The Sons of Katie Elder. Two years later brought Hopper's first full-fledged entrance into the drug culture as far as movies were concerned as he co-starred with Peter Fonda in The Trip, which was directed by Roger Corman and written by Jack Nicholson. That same year, he appeared in Cool Hand Luke. In 1968, Hopper appeared in Clint Eastwood's Hang 'Em High.

Cause. He worked again with Dean in the last of Dean's three films, Giant, in 1956. Much of his early work both on television and on film was spent in westerns including 1957's Gunfight at the O.K. Corral as Billy Clanton opposite Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster. The same year, Hopper got to be an emperor, Napoleon no less, in Irwin Allen's The Story of Mankind. For the next several years, his work was restricted mainly to television, including The Twilight Zone and The Defenders. His first crossover toward the counterculture might have occurred in 1964, when he played the title role in an episode of Petticoat Junction titled "Bobbie Jo and the Beatnik." Hopper still did plenty of westerns, appearing opposite John Wayne for the first time in 1965's The Sons of Katie Elder. Two years later brought Hopper's first full-fledged entrance into the drug culture as far as movies were concerned as he co-starred with Peter Fonda in The Trip, which was directed by Roger Corman and written by Jack Nicholson. That same year, he appeared in Cool Hand Luke. In 1968, Hopper appeared in Clint Eastwood's Hang 'Em High.With 1969, Hopper embarked on his first directing project: starring with Peter Fonda and Jack Nicholson in the counterculture classic Easy Rider. The same year, he also got to be one of the bad guys opposite Wayne's Rooster Cogburn in True Grit. Two years later, he starred and directed again (and provided the story) in The

Last Movie, which even featured an acting turn by director Samuel Fuller. Following a few other films, he became the second of many actors to put their stamp on Patricia Highsmith's famed serial killer Tom Ripley in Wim Wenders' 1977 The American Friend. During his days of heavy real life drug use, Hopper danced through the role of a photojournalist in Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now. Despite his out-of-control private life, Hopper still managed to snag roles, though nothing of real significance either on film or television, despite small roles for major directors such as Coppola's Rumble Fish, Sam Peckinpah's The Osterman Weekend and Robert Altman's O.C. and Stiggs. Then came 1986 and Hopper's huge comeback. Two roles brought him back on the radar and earned him respect. First, came what may end up being his most memorable role as Frank Booth in David Lynch's Blue Velvet. Booth was one of the most bizarre villains ever dreamed up for a movie, frightening and funny, prone to use nitrous oxide as he assaults the woman he's obsessed with and seldom producing a sentence without at least one use of the F word. The second film was far more conventional. Hoosiers, the tale of an Indiana high school basketball team, gave Hopper the role of an alcoholic assistant coach opposite Gene Hackman. Both movies were the stuff of Oscar buzz and come nomination day, Entertainment Tonight even set up cameras and watched with Hopper as the nominations were announced on TV. "They went with Hoosiers," he said as his name was announced. You could tell he was happy to be nominated but at the same time slightly disappointed that the Academy went with the safer choice. There was a third 1986 film, one which Hopper publicly disowned, but which I think he shouldn't be ashamed of. He gave an over-the-top turn in an over-the-top and absolutely great satire Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. He should be proud of the avenging Texas ranger, venturing through caves with mini-chainsaws in a holster while he sang, "Bringing in the Sheaves."

Last Movie, which even featured an acting turn by director Samuel Fuller. Following a few other films, he became the second of many actors to put their stamp on Patricia Highsmith's famed serial killer Tom Ripley in Wim Wenders' 1977 The American Friend. During his days of heavy real life drug use, Hopper danced through the role of a photojournalist in Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now. Despite his out-of-control private life, Hopper still managed to snag roles, though nothing of real significance either on film or television, despite small roles for major directors such as Coppola's Rumble Fish, Sam Peckinpah's The Osterman Weekend and Robert Altman's O.C. and Stiggs. Then came 1986 and Hopper's huge comeback. Two roles brought him back on the radar and earned him respect. First, came what may end up being his most memorable role as Frank Booth in David Lynch's Blue Velvet. Booth was one of the most bizarre villains ever dreamed up for a movie, frightening and funny, prone to use nitrous oxide as he assaults the woman he's obsessed with and seldom producing a sentence without at least one use of the F word. The second film was far more conventional. Hoosiers, the tale of an Indiana high school basketball team, gave Hopper the role of an alcoholic assistant coach opposite Gene Hackman. Both movies were the stuff of Oscar buzz and come nomination day, Entertainment Tonight even set up cameras and watched with Hopper as the nominations were announced on TV. "They went with Hoosiers," he said as his name was announced. You could tell he was happy to be nominated but at the same time slightly disappointed that the Academy went with the safer choice. There was a third 1986 film, one which Hopper publicly disowned, but which I think he shouldn't be ashamed of. He gave an over-the-top turn in an over-the-top and absolutely great satire Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. He should be proud of the avenging Texas ranger, venturing through caves with mini-chainsaws in a holster while he sang, "Bringing in the Sheaves."After that, he worked steadily, though often as the broadest of villains. There were still textured performances to be found such as the hermit with the blowup doll in 1987's River's Edge. He got to be one of Theresa Russell's wealthy victims in Black Widow. In 1988, he returned to the director's chair with Colors, a police vs. gang drama starring Sean Penn and Robert Duvall. When Penn took his first try at directing, Hopper snagged a role in Penn's The Indian Runner. One of his most enjoyable later turns comes in the very

underrated 1990 film Flashback, where he played a long-on-the-lam '60s activist who is being taken back to jail by FBI agent Kiefer Sutherland. The movie is funny and full of fresh twists and deserves a better reputation than it has — hell, it deserves a reputation, period. In 1993, he was a truly busy man with a mix of good and goofy performances in films that ranged from the sublime to the ridiculous. He was charming in the so-so Boiling Point, part of the solid ensemble in John Dahl's Red Rock West and the evil King Koopa in Super Mario Bros. His finest 1993 moment though came in a superb acting duet with Christopher Walken in the Quentin Tarantino-scripted, Tony Scott-directed True Romance, really the best part of the entire film.

underrated 1990 film Flashback, where he played a long-on-the-lam '60s activist who is being taken back to jail by FBI agent Kiefer Sutherland. The movie is funny and full of fresh twists and deserves a better reputation than it has — hell, it deserves a reputation, period. In 1993, he was a truly busy man with a mix of good and goofy performances in films that ranged from the sublime to the ridiculous. He was charming in the so-so Boiling Point, part of the solid ensemble in John Dahl's Red Rock West and the evil King Koopa in Super Mario Bros. His finest 1993 moment though came in a superb acting duet with Christopher Walken in the Quentin Tarantino-scripted, Tony Scott-directed True Romance, really the best part of the entire film.

Following the next year, he created another memorable screen villain in the surprise hit thriller Speed staring Keanu Reeves and boosting Sandra Bullock to stardom. His 1995 villain was not nearly something to be as proud of, but then neither was the movie as he got trapped in the Kevin Costner disaster

Waterworld. The next year, he got a smaller role as a bigwig in art in artist Julian Schnabel's directing debut, Basquiat. 1999 brought him parts in EdTV and the nearly forgotten Jesus' Son starring Billy Crudup. One of his last memorable villains came late in the run of the first season of television's 24, when the writers realized they had killed off all their villains too early and needed a big one to fill out the remaining hours in their first day. Hopper filled the part as Victor Drazen, a Serbian war criminal with a bad accent and a grudge against Jack Bauer. Most of his films after that were forgettable, though he did appear in another installment in George Romero's zombie series, Land of the Dead, a right-wing try at making a satire about a Michael Moore-type character called An American Carol, a short-lived TV series titled E-Ring and a part in a TV version of the movie Crash. Despite his late turn toward the GOP, Hopper did admit, as did many Republicans, that in the 2008 election that after voting for Bush twice, he was voting for Obama. During the long final months of his illness, Hopper did manage to make a public appearance March 26 looking very frail to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. According to IMDb, an unconfirmed report places him in a completed film and another one in post-production, so there may be some more Dennis Hopper to see. As prolific as he was though, I doubt anyone has seen all his work that's out there now. R.I.P. Mr. Hopper. In dreams, we walk, with you.

Waterworld. The next year, he got a smaller role as a bigwig in art in artist Julian Schnabel's directing debut, Basquiat. 1999 brought him parts in EdTV and the nearly forgotten Jesus' Son starring Billy Crudup. One of his last memorable villains came late in the run of the first season of television's 24, when the writers realized they had killed off all their villains too early and needed a big one to fill out the remaining hours in their first day. Hopper filled the part as Victor Drazen, a Serbian war criminal with a bad accent and a grudge against Jack Bauer. Most of his films after that were forgettable, though he did appear in another installment in George Romero's zombie series, Land of the Dead, a right-wing try at making a satire about a Michael Moore-type character called An American Carol, a short-lived TV series titled E-Ring and a part in a TV version of the movie Crash. Despite his late turn toward the GOP, Hopper did admit, as did many Republicans, that in the 2008 election that after voting for Bush twice, he was voting for Obama. During the long final months of his illness, Hopper did manage to make a public appearance March 26 looking very frail to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. According to IMDb, an unconfirmed report places him in a completed film and another one in post-production, so there may be some more Dennis Hopper to see. As prolific as he was though, I doubt anyone has seen all his work that's out there now. R.I.P. Mr. Hopper. In dreams, we walk, with you.

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Coppola, Corman, Duvall, Eastwood, Fuller, Hackman, James Dean, K. Douglas, K. Sutherland, Lancaster, Lynch, Nicholson, Obituary, Peckinpah, Sean Penn, T. Scott, Tarantino, Walken, Wayne

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

The John Williams Blog-a-thon

Please see below all the entries we've received for the John Williams Blog-a-thon. Feel free to post a link to your pieces in the comments section or send me an e-mail — we’ll update the links accordingly. If you do not have a blog of your own, send your pieces to me in Word; and we’ll edit ‘em and put them up on the site.

Yub Nub!

Bobby "Fatboy" Roberts kicks off the festivities with a beautiful story from his childhood.

Matt Zoller Seitz and Ali Arikan have a conversation about John Williams's role in the Star Wars saga.

Jeff Graebner offers an appreciation of the Amazing Stories soundtracks.

The Modernish Father and his modernish son had a blast last fall at Star Wars In Concert.

Drake Lelane turns environmentalist by reusing John Williams and the Crystal Skull Persuasion that he wrote for Ali's Indiana Jones blog-a-thon a couple of years ago.

Neil Sarver jazzes with the master.

Peter Nellhaus listens to the score for Paul Wendkos's Gidget Goes to Rome (1963), and sees the portrait of the composer as a young man.

Kenji Fujishima salutes Williams for opening the door to a personal awareness of music in film.

Sean Ferguson talks about three of his favourite movie scores. Two out of three ain't too bad, Johnny.

Tony Dayoub wants to remind everyone of other pieces of music for sci-fi works the composer created when he was going by the first name Johnny.

Jimmy J. Aquino writes about Williams' first score for Spielberg, The Sugarland Express.

George Myers writes about an early score for 1965's John Goldfarb, Please Come Home starring Shirley MacLaine which he saw once but which legal problems prevent the rest of us from hearing.

THE FUTURIST! remembers the evocative, emotional score to The Cowboys.

Dennis Cozzalio sings the praises of his favorite Williams score for a Spielberg movie: 1941.

Bob Glickstein thankfully had the soundtrack of The Empire Strikes Back to tide him over until the film opened.

Larry Aydlette rounds up his own brief contribution to say goodbye to the blog-a-thon on its last day.

Tweet

Labels: Blog-a-thons, John Williams, Music

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

The Music of the Prequels: A Conversation

By Matt Zoller Seitz

and Ali Arikan

Matt Zoller Seitz: We gather here today to celebrate the talent, longevity and all-around wonderfulness of John Williams, whose work is being examined in a blog-a-thon. We're focusing on the Star Wars prequels because, after talking pretty extensively about Williams' long and prolific career, we mutually concluded that his work on the prequels represents his greatest conceptual achievement, and very possibly the summation of everything he knows about traditional film scoring.

And I suppose we should specify what we mean by traditional. I don't believe we're talking, Ali, about his more subtly colored, modernist work on such films as The Long Goodbye, or his historical spelunking in Steven Spielberg's historical epics (Schindler's List especially). We're talking about Williams in full-on Erich Korngold/Franz Waxman/Max Steiner mode, although personally I think Williams is more versatile and imaginative than any of them. More specifically, though, we're talking about what Williams does with that talent. We all know he's a master of a certain type of brash, rousing film score, the kind of score that's deployed in the service of what score composers often refer to, often disparagingly, as "Mickey Mousing." You know, Mickey Mouse sneaks across the screen and the score plays "sneaky" music. This composer (and conductor) is the absolute king, the Satchmo, the Hendrix, the Satchel Paige of Mickey Mousing. Nobody in film history can touch the guy. But what's different about the prequels is that he's doing what could be called, for a lack of a phrase, postmodern Mickey Mousing. He's doing what he did in the original Star Wars movies, even revisiting certain themes, but he's doing so with a really specific intent, you know?

Ali Arikan: One of my favorite moments in the history of the Oscars is the soundtrack medley of 2002 conducted by John Williams. In a fairly low key ceremony, the grandeur and awe of classic Hollywood cinema was briefly captured as Williams played a host of classic themes by Bernard Herrmann, Malcolm Arnold, Elmer Bernstein, etc. When it came to Alfred Newman’s 20th Century Fox fanfare, everyone knew exactly what piece of music it would be followed by: the main theme from Star Wars. To this day, every time I watch a Fox film and hear those magnificent horns, the nerd in me expects (hopes?) that it would be followed by Williams’ most famous Wagnerian fanfare. It is unrelenting, brash, and cheeky. Has any modern film composer been so bold with the brass section?

Interestingly, the theme begins almost in media res, which is fitting since so does the “first” film. Williams usually has a way of building up the melody, building up the eventual motif, but he forfeits this for the Star Wars Main Theme. In contrast, his Welcome to Jurassic Park, for example, has a lengthy and gentle piano, woodwind and string intro that eventually gives way to those majestic horns. Not so here. John Williams’s work in Star Wars is not just a part of the film, it is almost a metatextual narrator.

And this becomes even more apparent during the prequels. The way he manages to work in motifs from the original trilogy to new pieces of music is almost like the way Puccini played around with various themes in his operas. I think it’s safe to say that we can call the Star Wars scores — and I believe he scored around 15 hours of music for the entire saga — his magnum opus.

Matt: Yeah, absolutely. And maybe before we go deep-dish on Williams' contribution to the prequels, we should establish that in no way is this article meant to suggest that the prequels themselves are without flaw, or even especially consistent. On the micro level, they pretty much suck, in the way that the original Star Wars movies pretty much sucked.

Weak dialogue, wooden performances, too obvious symbolism. Harrison Ford's complaint to Lucas, "You can type this shit but you can't say it," was painfully true in a lot of cases. Where the original films excel is in creating an imaginative space, a mythology that plugs into nearly every culture and belief system — which is to say they excel at the macro level. That's no small achievement, and I don't think George Lucas gets enough credit for it. That's the pinnacle of popular art, creating something that enters the minds, the experiences, of hundreds of millions of people and becomes a reference point for, well, their lives. (Just the other day my son was asking me how long he would have to go to school and study science to learn how to build his own lightsaber. He's 25. I'm kidding, he's six.)

Weak dialogue, wooden performances, too obvious symbolism. Harrison Ford's complaint to Lucas, "You can type this shit but you can't say it," was painfully true in a lot of cases. Where the original films excel is in creating an imaginative space, a mythology that plugs into nearly every culture and belief system — which is to say they excel at the macro level. That's no small achievement, and I don't think George Lucas gets enough credit for it. That's the pinnacle of popular art, creating something that enters the minds, the experiences, of hundreds of millions of people and becomes a reference point for, well, their lives. (Just the other day my son was asking me how long he would have to go to school and study science to learn how to build his own lightsaber. He's 25. I'm kidding, he's six.)The prequels have even more problems at the micro level than the originals. In my New York Press review of Revenge of the Sith, I described Lucas as a filmmaker for whom the impossible seems to come easily, yet who can't seem to master, or else has no real interest in, the basics. I compared him to a prophesied sci-fi manchild who can levitate entire continents with his mind but can't master the use of a knife and fork. That said, there's some heavy-duty world creation, some heavy duty mythologizing, going on in the prequels, and if anything the films are much more conceptually sophisticated than the originals, and frankly more conceptually sophisticated than any other sci-fi or fantasy series, in terms of how they're constructed and what they're trying to accomplish. The trilogies mirror each other in all sorts of ways. And the mirroring is not only intentional, it's fiendishly exact.

To give you just one example, the scene in Revenge of the Sith where Mace Windu, the Emperor and Anakin have a three-way showdown in the emperor's throne room, the scene where Anakin turns to the dark side by turning against Mace.

The situation and the characters' predicaments evoke the throne room scene that ends Return of the Jedi: Vader's redemption. But if you watch the two scenes in succession, you'll see that Lucas hasn't just mirrored the throne room showdown from Return of the Jedi in Sith at a narrative level — the compositions and blocking often mirror Jedi's as well. Williams' score contributes mightily toward strengthening Lucas' mythic architecture. It sells the whole thing, makes it more energetic and heartfelt and persuasive. Williams does this by raiding his own cues for the original trilogy — doing with music what Lucas does pictorially. He doesn't just do it in the two big throne room scenes. He does it all through the prequels. He takes you down memory lane and says, "This scene is the cousin of another scene from the original series, or an ironic inversion of it, or contains elements of it, or is an answer to it." It's like he's superimposing the trilogies on top of one another by way of his own score.

The situation and the characters' predicaments evoke the throne room scene that ends Return of the Jedi: Vader's redemption. But if you watch the two scenes in succession, you'll see that Lucas hasn't just mirrored the throne room showdown from Return of the Jedi in Sith at a narrative level — the compositions and blocking often mirror Jedi's as well. Williams' score contributes mightily toward strengthening Lucas' mythic architecture. It sells the whole thing, makes it more energetic and heartfelt and persuasive. Williams does this by raiding his own cues for the original trilogy — doing with music what Lucas does pictorially. He doesn't just do it in the two big throne room scenes. He does it all through the prequels. He takes you down memory lane and says, "This scene is the cousin of another scene from the original series, or an ironic inversion of it, or contains elements of it, or is an answer to it." It's like he's superimposing the trilogies on top of one another by way of his own score.Ali: Definitely. Especially to the point that the main character, Anakin Skywalker, has two funerals. One, in Revenge of the Sith, when he is robbed of his former self by being turned into Darth Vader: we witness the fear in his eyes as the mask is lowered onto his face. The next is in Return of the Jedi, when, outwardly, he is Vader, but he has redeemed himself: the funeral pyre, lit by his son, signifying a sort of latter-day baptism with fire. Separately, both scenes work wonderfully well — together, they have a mythic quality.

The prequels were always going to be a hard sell. One of the most enigmatic lines from the original trilogy is Vader’s “Obi Wan never told you what happened to your father.” When I hear that, I think of grandeur and dragons and knights and all that good stuff. I don’t think of “YIPPEE!” Even though I do enjoy The Phantom Menace more than anyone I know, it was definitely not what I was expecting. Then again, and this might be a lot of fanwanking on my part, maybe that was the point.

Allow me to argue this from a musical point. John Williams obviously tried something different with the prequels. He wrote three overriding themes for each: Duel of the Fates for The Phantom Menace, Across The Stars for Attack of the Clones, and Battle of the Heroes for Revenge of the Sith. Nonetheless, I think if we were to name a secondary theme for the saga – the first one being the Force Theme — it would be Duel of the Fates. When the soundtrack for The Phantom Menace was first released, and I heard it, I remember thinking: “This sounds nothing like a Star Wars score, and yet it sounds exactly like a Star Wars score.” It was bizarre: first of all, you had that intimidating chorus in Sanskrit: “KORAH MAHTAH, KORAH, RAHTAMAH.” Apparently it means “Under the tongue root a fight most dread, and another raging behind, in the head,” but either Sanskrit is terribly economical, or that’s an apocryphal interpretation. Either way, even though Williams had used choral arrangements in Star Wars scores before (most notably during Luke’s final assault on Darth Vader in Return of the Jedi), never had they been in such prominence. Then you have this sense of inevitability, a sense of dread. Even though Duel of the Fates represents a constant struggle between good and evil, nonetheless, it seems rather certain that the bad guys will win: it’s no wonder that the only time it plays during the second prequel is when Anakin is searching for the Tusken Raiders who kidnapped his mother, and just before he massacres the lot of them. The way the strings and the horns crescendo is nothing short of breathtaking.

But I especially love the way it seems to end — and then doesn’t. Both the strings and the chorus continue subtly, as they give way to a final, much more violent crescendo, as if to reinforce Mace Windu’s rhetorical question to Yoda after the death of Darth Maul: “But which one was destroyed? The master or the apprentice?” Once again, Williams has worked into the music pieces from the narrative: you think this is over, but it’s only just begun.

Matt: Speaking of Duel of the Fates, one of my very favorite Williams moments is in the opening action sequence of Revenge of the Sith, maybe Lucas' peak as a choreographer of large-scale mayhem.

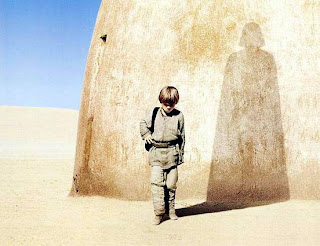

Anakin has rescued the Emperor, or at that point in the story the Chancellor, from General Grievous, and he has briefly saved Obi Wan as well. And now the chancellor's ship is crashing, burning up in the atmosphere, and Anakin has to pilot it safely down to a landing strip as it's crumbling. It's an amazing sequence in itself. But what pushes the whole thing up a notch — what makes it intelligent as opposed to just spectacular — is Williams' music. He's doing what I talked about earlier, superimposing one trilogy on top of the other. As you can see at the 10:38 mark in this clip, as the ship is making its final ascent, when we're seeing Anakin at the peak of his physical prowess and bravery, and he's saving the life of the man who will later rule the galaxy, and him, what do we hear? Duel of the Fates, which as you say is about the push-pull between the dark side and the light, and layered over that, The Force Theme, which I believe we heard for the first time in A New Hope in that iconic shot of Anakin's son Luke, the one who was really prophesied to restore balance to the force (sorry, Mace Windu!), staring out at the twin suns of Tattooine.

Anakin has rescued the Emperor, or at that point in the story the Chancellor, from General Grievous, and he has briefly saved Obi Wan as well. And now the chancellor's ship is crashing, burning up in the atmosphere, and Anakin has to pilot it safely down to a landing strip as it's crumbling. It's an amazing sequence in itself. But what pushes the whole thing up a notch — what makes it intelligent as opposed to just spectacular — is Williams' music. He's doing what I talked about earlier, superimposing one trilogy on top of the other. As you can see at the 10:38 mark in this clip, as the ship is making its final ascent, when we're seeing Anakin at the peak of his physical prowess and bravery, and he's saving the life of the man who will later rule the galaxy, and him, what do we hear? Duel of the Fates, which as you say is about the push-pull between the dark side and the light, and layered over that, The Force Theme, which I believe we heard for the first time in A New Hope in that iconic shot of Anakin's son Luke, the one who was really prophesied to restore balance to the force (sorry, Mace Windu!), staring out at the twin suns of Tattooine.  The Force Theme is such an optimistic, hopeful piece of music. It indicates great promise. And Williams is using it ironically and knowingly here, as if to say, "All the promise this kid displayed is about to cause untold harm to the galaxy — and this is it, folks. You're seeing the exact moment when everything turned to shit. It was the moment when he saved the chancellor."

The Force Theme is such an optimistic, hopeful piece of music. It indicates great promise. And Williams is using it ironically and knowingly here, as if to say, "All the promise this kid displayed is about to cause untold harm to the galaxy — and this is it, folks. You're seeing the exact moment when everything turned to shit. It was the moment when he saved the chancellor."Ali: I’m glad you bring up The Force Theme, because I’d love to hear your take on its significance over the entire saga. I would argue that this is the primary leitmotif of the films, and its appearance throughout the films triggers almost a sense memory. The first time we hear it is my favorite scene in the entire saga: Luke gazing into the binary sunset, as the melancholy motif subtly gives way to a perpetually progressive melody (it’s evocative of Jean Sibelius’ Symphony Number 4, the way it seems to tiptoe between joy and sorrow). It’s the epitome of the saga, isn’t it? The hero’s quest: not being content with the vagaries of life, the hero looks to the horizon, and the worlds unseen. What does Yoda say in The Empire Strikes Back: “A long time this one have I watched. All his life has he looked away to the future, to the horizon. Never his mind on where he was. What he was doing.” Luke wants more from life, he wants to be freed of the shackles of his surroundings: he seeks adventure. Despite being scolded by his uncle, despite his belief that he is never leaving Tattooine, despite the burden of mediocrity weighing down on his shoulders, a lingering feeling still remains in Luke as he gazes and imagines endless possibilities, and that feeling is hope. The hope that tomorrow will be better; that when adventure calls, he will prove his mettle. Ultimately, The Force Theme represents hope. Well, a new hope.

Matt: Yeah, and it's that hope that gets dashed in the prequels. That yin-yang you talk about in Duel of the Fates, the push-pull, is the thrust of the series, all six films. Nearly every major setpiece in the original trilogy is revisited in the prequels with a different conclusion, a different meaning. The original trilogy is the light side, the prequels are the dark side. And looming over all of it is Williams.

You know, in Japanese cinema there was a tradition, during the silent era, of this person called the benshi, or the explainer. He'd stand up at the front of the theater and interpret or almost mediate, if you will, between the story happening onscreen and the receptive audience out there in the dark. Williams is the benshi of the Star Wars movies, the explainer. He's not just italicizing and underlining things to make sure we get them — although this is a very old fashioned type of film storytelling, so there's an aspect of that in his mission. He's also teasing out deeper resonances, and perhaps — though a part of me hates to say this because I've already stated that I don't think Lucas gets enough credit as a mythmaker — maybe Williams is adding a lot as well.

There are times when I feel like he's the second editor on the series, perhaps over and above the editing team that put the footage together. He's an editor in the publishing sense — an eye in the sky who isn't trying to make a writer into a clone of himself, but who appreciates the writer for what he is, and wants to help him be the best him that he can possibly be. Williams' music helps Lucas be Lucas. I feel almost as if Williams figured out what Lucas was trying to say in particular moments and sequences and found a way, musically, to say it for him.

Ali: Funny you should mention the benshi, because the piece of music that plays as the Federation cruiser crashes into Coruscant is the same one that does during the final salvo of the space battle in The Phantom Menace. Whereas Anakin infiltrated the belly of the beast to destroy it in the first prequel, in Revenge of the Sith, he is saving the very beast that orchestrated the whole thing. Once again, the theme, the modern-day benshi, is doing the narration.

Another favorite is the aforementioned Across The Stars theme from Attack of the Clones. As Anakin and Padme are being wheeled into the Geonosian arena to be executed, Padme admits her love with the clumsiest dialogue in the entire saga (which is a feat, in itself): “I truly, deeply, madly, other-pointless-adverbly love you,” she says, and kisses Anakin. Despite the shortcomings of the dialogue, it is, nonetheless, a magnificent shot: the camera stays behind the two prisoners, who are initially obscured in the shadows, as they emerge into the sun-drenched arena. The camera then follows Anakin’s pov as he surveys the insectoid crowd voracious for their bloody demise. Across The Stars, in D minor (saddest of all keys), plays throughout the scene, and lends it a sense of tragedy: not because of any instantly impending doom (since we know they get out of this alive), but because of how their love will end: one will turn into an evil cyborg, the other will perish. Unlike the love theme from The Empire Strikes Back, Across The Stars has no hint of frivolity: it is a tragic theme for a pair of star-crossed lovers. So sad. It’s a classic.

On the whole, the prequels represent something truly bizarre: a seemingly child-like tale that ultimately gives way to despair. The most colourful locales, juvenile characters, and — on the surface, at least — whimsical stories end with total destruction. Lucas is a master storyteller, and, obviously, the Star Wars saga is his life's work. But he would not have been able to create such a universal fable out of it were it not for his most consistent lieutenant: John Williams.

Tweet

Labels: Blog-a-thons, Harrison Ford, John Williams, Lucas, Music, Spielberg, Star Wars

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Childhood cacophony

By Bobby "Fatboy" Roberts

I was 4, and visiting The Dalles, Oregon, during the first Christmas I can consciously remember. It was the first time anyone in my family had owned a VCR as a present. Those Ford Granada-size, top loading behemoths were a sign that one had made it in this world. My uncle, who had a satellite dish and a 21 inch TV, had bought this VCR for his family. And along with the VCR, he had obtained a bootleg copy of a movie I hadn't yet heard about. A movie called Star Wars.

I was 4. I didn't understand half of what was flying off the 21 inch screen. I was 3 feet in front of it, close enough to be lost in the scan lines. I don't remember much, but I remember that I was remembering everything. I was committing it all to memory. It was weird, even then, realizing I was recording these memories as they happened, half toddler, half computer, clad in corduroy and orange, staring at walking carpets and drowning in the wonderful combination of strings and drums and wrenches on guy-wires and gargoyle scuba tanks, the beautiful cacophony spilling from 3 inch speakers on either side of that 21 inch TV.

I remembered the hamburger ship. I remember the one-eyed garbage monster. I remembered the X ships blowing up the O base and the football player teasing the hell out of the blond dude in the bathrobe. I remember the giant dog with the diagonal belt yelling in time with the drums and the trumpets as they all won Olympic medals for blowing up big gray basketballs. I remember that, and the view out the window.

I was 4, and I couldn't pay attention to anything after 5 minutes. There was this strange, beautiful mish-mash of visuals on my uncle's TV. And there was the window, with a klieg light just outside of the door. And it illuminated every single fat snowflake descending from the clouds. And to my 4 year old mind, watching this movie with a hamburger ship speeding through Mylar tunnels in something called "hyperspace," the light glinting off those crystalline, utterly unique flakes flitting from the darkened clouds denoted speed. The snow wasn't falling. The house was flying. And as the Falcon blasted toward Yavin, I fully believed my uncle's house was ascending towards the cosmos. The Christmas lights bouncing off the white walls, softened by the shaggy brown carpet I was laying on, blending with the light diffusing through the window and melting into the sounds and images vibrating off the TV...

I was 7. It was my birthday. It was December and I had spent the last month and a half circling Star Wars toys in the Sears catalogue. Return of the Jedi had been out for about a year and a half, and I still hadn't seen it. We couldn't afford the family outing into the big city where it was playing. I had checked out the read-along book from the Marion County bookmobile whenever it was available. I deprived so many kids in that county from any visits to that galaxy far, far way. I read along, and listened along, at least once every day. I colored over the read-along book. I fell asleep with the cassette playing on my Fisher-Price tape-deck. The film had just moved to the Star Cinema in Stayton, Ore., December 1984. It was a surprise birthday present from my parents, after constant nagging to tape making-of specials and buy me action figures they couldn't afford. December 16th rolled around, and my dad showed me the newspaper listings for movies. My eyes zeroed in on the Star Wars logo. I looked up at him, unblinking, unbelieving. He smiled back. I was in the car. I was in the theater. I was cracking up my parents because months and months of falling asleep to the read-along meant I was humming themes as they spilled out of the speakers. Tiny hands were conducting the London Symphony from thousands of miles, years in the future. I was saying the lines a second before the actors could recite them. I was a 7 year old affecting a shit British accent and stepping on Ian McDiarmid's dialogue. "So be it...Jedi."

It was awesome.

We heard the Star Wars theme, as the snow blew across the windshield on the way home, like hyperspace, on the AM radio in the car. I fell asleep in the backseat. John Williams in my ears. It's why whenever it snows outside, I put in the soundtrack. The one that comes in the plain black cover with the plain white letters that say Star Wars on it. I let Williams play full blast. And I imagine my car is chasing after my Uncle's house, and if I catch that house, there's a 4 year old in corduroy and orange, resting his head on his hands, elbows dug into a shaggy carpet, with wide-eyes, awakening to the concept of imagination, and realizing the majesty in it.

The visuals of my childhood may look like Jim Henson. But the audio? It's all John Williams.

Roberts is co-host of "Cort and Fatboy" at http://pdx.fm/in Portland, creator of the Geek: Remixed series of mashups, and part-time pop-culture critic for both Cracked.com and The Portland Mercury

Tweet

Labels: Blog-a-thons, Jim Henson, John Williams, Music, Star Wars

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

A Tale of Two Losts

By Alex Ricciuti

"They all die and go to heaven? Seriously?"

That was one of the first comments I read online after the finale was over.

Yes, and apparently some people can take a cab there, but still, don't forget to tip the driver with American money. And remember, heaven's official language is English. I was half-expecting to see Betty White make an appearance as Jack's grandmother, chiding him for never calling while she was still alive.

But at least the sentimentality wasn't half as annoying as those peaceful, knowing looks the characters were going around with in the afterlife universe like they had just been inducted into some kind of cult. Lost usually kept its distance from the excessively saccharine for most of its run only to make its final episode a 100-minute tearjerker experiment (out of a 2 and 1/2 hour run-time. Did all those commercial breaks ruin it for you?) with a juvenile ecumenical message. Honestly, the acting was good, but only because it was obvious that it was the actors themselves saying goodbye to each other after six years of being castmates.

Maybe that's a little too harsh. The execution was far better than I've just implied, but this Six Feet Under-miming ending begs the question — What kind of show was Lost?

There were really two Losts. One was a mystery/fantasy/sci-fi show meant to keep you watching week after week, and the other was, as the show's producers never failed to tell us, all about character. Well, they wrapped up the character arcs pretty neatly, with horse-pill doses of redemption and resolution.

I would have liked to believe that it was always about the characters but Lost painted its characters in the typical broad strokes of a classical (read: mythological) storytelling style; their actions were always bent more toward plot pivots than anything related to realistic character development. Just think about all the episodes spent moving characters around the island just to get them into place for an action set-piece or to have a surprising character-popping-out-of-the-jungle moment. There were literally dozens of these contrivances — I'm going off into the jungle and won't be back for a few episodes so don't wait up for me — which, I assume, most Lost fans were perfectly willing to forgive in exchange for a thematically solid storyline payoff. This never happened. This was a mystery show that turned itself into an office farewell party in its last 100 minutes.

And what about the theme of the episode itself (titled "The End")?

Redemption, yes, transcendence, OK, I get that part — they all die and have to “move on.” But the island, the light, the monster, what were these things metaphors for? That isn't terribly clear or perhaps it's too simplistic (monster = evil, light source = gate to hell — You mean like the hell-mouth on Buffy?). The island story is an allegory for what, exactly? Please, someone fill me in because it wasn't Purgatory — that was the sideways universe. As Christian Shepherd told Jack, everything that happened on the island happened. It was real. The island is a place that characters come to and find redemption. Is that it? That's a little too high school-level drama for me.

If Lost was going to be a mystical, spiritual experience I would have gladly been on board. I like crazy stuff that doesn't make sense. I love David Lynch. I even listen to experimental jazz. But the idiom of the show was always literal and real. There were few Lynchian moments on the show (one being a Locke dream sequence

from season 3 when he built a sweat-lodge to summon an answer from the island regarding the whereabouts of Mr. Eko). The cinematography, the dialogue, the entire style of the show was never dream-like or lyrical. It was always firmly grounded in a certain realism and the mysteries were laid out in the foreground and meant to be taken literally and as central to the show. So when Kate flies off the island again in the finale it is a legitimate question to ask — since we saw scenes of the very public nature of the return of the Oceanic 6 to civilization back in Season 4 — what the hell is the lady going to tell people? She has a penchant for boarding airliners that disappear over the Pacific? And what is Richard Alpert going to say — Hi, my name is Richard and I'm 175 years old. Oh, look at that, I never imagined my native Teneriffe would turn into a haven for drunken German tourists. Thinking of it this way makes the whole thing look really ridiculous. But the show has put it in those terms.

from season 3 when he built a sweat-lodge to summon an answer from the island regarding the whereabouts of Mr. Eko). The cinematography, the dialogue, the entire style of the show was never dream-like or lyrical. It was always firmly grounded in a certain realism and the mysteries were laid out in the foreground and meant to be taken literally and as central to the show. So when Kate flies off the island again in the finale it is a legitimate question to ask — since we saw scenes of the very public nature of the return of the Oceanic 6 to civilization back in Season 4 — what the hell is the lady going to tell people? She has a penchant for boarding airliners that disappear over the Pacific? And what is Richard Alpert going to say — Hi, my name is Richard and I'm 175 years old. Oh, look at that, I never imagined my native Teneriffe would turn into a haven for drunken German tourists. Thinking of it this way makes the whole thing look really ridiculous. But the show has put it in those terms. So the fact that there were no — let's not even use the word 'answers' — let's say resolution to many of the main mysteries of the show is a huge bone of contention.

Why couldn't women bear children? How were Hugo, Jack, Kate and Sayid sucked out of a plane and landed on the island in 1977? Did the bomb change the future? If it didn't why did we spent the entirety of season 5 traveling into the past?

And what about the philosophical question upon which the whole of season 5 was based — a brilliantly set-up narrative device on the debate between free will and destiny. Can the past be changed or is it fixed? And if you travel back there and cannot change it, then doesn't that mean that destiny trumps free will?

But that question, very beautifully put by the writers, was never resolved along with almost every other mystery on Lost. The sideways world was not a construct of the split-timeline caused by the bomb going off. According to Christian, the castaways themselves created the sideways universe after they died.

The finale was all about the triumph of faith and love over reason and science. That is one question they did indeed answer and perhaps the writers feel that that negates the need for any further explanations.

One has to understand the demands of the medium. Episodes on broadcast television have to be broken into six mini-acts in order to fit the commercials in. Each of those acts has to end in a mini cliffhanger to make sure the viewer returns after the break. Each episode, every season has to end the same way -— leaving viewers wanting more and wondering about what happens next. Don't ever forget, networks are for-profit corporations and want to milk a show for as many seasons as possible.

And that left the writers in a Catch-22 predicament: Answer the mysteries too early and the audience leaves you (Twin Peaks). String them out too much and the viewers will give up and abandon the show as you go off the rails (X-Files). Replace old mysteries with new ones and they will keep watching for a while (new Lost formula). But after six seasons of doing this you will never be able to untangle the mess that is your story...so you simply don't. You do a back-flip and say it's all about the characters.

This isn't art. It's commercial television.

Now, go forth, children of the tube, and start anticipating the next season of Mad Men.

But maybe you should do yourself a favor and avail yourself of technology. Watch without the commercials — exercise your free will.

Tweet

Labels: Lost, Lynch, Mad Men, TV Recap, Twin Peaks

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Treme No. 5: Shame, Shame, Shame

By Edward Copeland

Creighton Bernette definitely is embracing his role as voice of the city, even if he'd never admit it, as he records another YouTube rant, this time aimed directly at President Bush, though he says he's appealing to the president's better angel to keep his promise and help salvage his beloved city since the next hurricane season is a mere five months away. It is one of many highlights in the fifth episode of Treme, "Shame, Shame, Shame," the best episode of the series I've seen so far.

As great as Creighton's rants are (especially as delivered by John Goodman), that's not how this episode opens. In a departure from most David Simon works we've seen so far, "Shame, Shame Shame" opens with LaDonna having a nightmare involving her still missing brother David. You don't realize it's not reality at first as a