Friday, September 29, 2006

The Greatest Story Ever Sold by Frank Rich

The other alternative, of course, is that this war of choice could prove to be an enormous victory for Iran and Al Qaeda alike, a commensurate disaster for Israel and the West, and a political boon to other jihadists worldwide (starting with those who consolidated governmental power in U.S.-endorsed elections in Iraq, Palestine, and Egypt). Should that be the case, the Bush presidency could well prove, as its most severe critics have maintained, the worst ever. Its legacy will include the destruction of America's image, credibility, and prestige abroad; record budget deficits produced by unchecked spending and tax cuts; an abused and broken military; a subversion of the Constitution achieved by rigidly ideological judicial appointments, the abridgement of civil liberties, and outright lawbreaking in the White House; an indifference to environmental imperatives, including the energy conservation urgently needed to end America's chronic economic dependence on the congenitally unstable Middle East; and the promotion of America's homegrown religious fundamentalism with both official and political assaults on medical and earth science (including evolution) and the rights of gay Americans. (And that's just the short list.)

By Edward Copeland

While that is just the short list, the focus of Frank Rich's compulsive page turner, The Greatest Story Ever Sold, only concerns how the Bush administration used P.R. and showmanship to sell the country and trick the Democrats into backing a war in Iraq that we should never have entered and which undermined our war on the real terrorists behind 9/11. The New York Times columnist (and former great, feared theater critic at the same paper) doesn't reveal anything that we didn't know about the war in Iraq, but he has done a great service by compiling it all in one place in an incredibly readable way, with frequent footnotes (real footnotes — not that kind Ann Coulter employs) and a massive timeline that lines up what the administration really knew versus what they told the public.

This corrupt and arrogant administration has committed so may breaches that it is easy to forget all of the details over time, but Rich's riveting account brings it all back to you as on page after page, it retrieves past anger and outrage from the recesses of your mind as to what atrocities Dubyaland has committed against our country, our democracy and the world, undermining the United States' long-standing moral authority around the world when we needed that authority more than ever to combat the threat of terrorism after 9/11.

Still, The Greatest Story Ever Sold is not an angry cry against George W. Bush and Rich's talent also produces many laughs along the way, especially for a subject so tragic you wouldn't think it possible to be funny. He especially accomplishes this in the book's opening pages, setting up what trivialities the U.S. was focusing on in the summer before the tragedy of 9/11, when shark attacks and Gary Condit dominated what passed for "news" on the silliness that passes for journalism most of the time on cable news. He has one particularly funny passage recalling what was supposed to have been the big summer movie of 2001, Pearl Harbor.

The vapid Pearl Harbor was an essential historical artifact anyway — not of its ostensible subject but of the tranquil American summer of 2001. The forty-minute bombing sequence looked like a state-of-the-art digital video game, with even the bloodshed sanitized to preserve the financially desirable PG-13 rating. ... Even medical miracles are effortlessly within reach: in one scene of high drama, FDR, trying to rally his Cabinet, miraculously rises from his wheelchair to stand on his own two feet, polio be damned.

The main selling point of this excellent tome though remains putting in one quick read the laundry list of misinformation, wrong assumptions and attacks on administration critics that the world has endured as neocons pursued their foreign policy visions and then were forced to defend them, despite each new fact that wagged a figurative finger in their face as to how wrong they were.

Rich also points out how Hurricane Katrina may have been the final straw to break Dubyaland's straw man's back, opening most Americans' eyes to the arrogance, corruption and incompetence of this administration.

Katrina was 9/11 deja vu with a vengeance, from the president's inattentiveness to the threat before the storm struck to his disappearing on the day itself to the reckless botching of the reconstruction efforts. ... The administration's complete obliviousness to the possibilities for civil disorder, energy failures and food and water deprivation in a major city under siege lacked only the Rumsfeld tagline of "Stuff happens." Though history is supposed to occur first as tragedy, then as farce, this time tragedy was being repeated as tragedy.

For anyone whose blood has boiled over the actions of this administration and for those who still prefer to shield their eyes from the facts, Rich's book is an essential read. Rich may well have written the finest historical textbook ever.

Tweet

Labels: Books, Nonfiction

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, September 25, 2006

The Wire No. 40: Home Rooms

BLOGGER'S NOTE: As always, know that spoilers lie below, so don't venture further unless you've seen the episode or don't care if you know what happens.

By Edward Copeland

School is back in session — and so is Omar. Oh, indeed. Keeping with The Wire's tradition of saving Omar (Michael K. Williams) until each season's third episode, the rip-and-run artist returns, complete with a new boyfriend and, in what I hope is not foreshadowing of his fate this season, living in a rowhouse apartment hidden behind one of those same plywood signs telling who to contact if there is a trapped animal — the same signs that Snoop and Chris (Gbenga Akinnagbe) hide Marlo's victims behind. In what has to be one of the funniest Omar scenes yet, he is distressed to find that he and his lover are out of his favorite cereal, so he ventures out in the street in his blue robe — unarmed — to the cries of neighborhood children shouting, "Omar's coming." Once he gets some cereal (not even the kind he wanted) and some smokes, he leans against a building only to have someone drop their drug stash to him unprovoked. You can see the disappointment in his eyes. His "job" is a game to him, and that takes all the fun out of it. As he tells his boyfriend, "It ain't what you takin', it's who you takin' it from." Later, when they pull off an actual score from a dealer working out of the same convenience store, he beams, "That's the reason we get up every morning."

Omar is not the only major character finally putting in an appearance this season. The now-retired Bunny Colvin (Robert Wisdom) returns as well. Since his exit from the Baltimore P.D., Colvin has been working security at a posh hotel, but once a cop, always a cop. When he insists on cuffing an influential businessman for roughing up a hooker, he soon finds himself unemployed again. However, opportunity comes his way again in the form of an academic at the University of Maryland School of Social Work who wants to use Colvin in a program aimed at saving kids from the thug life of the streets. The naive professor (played as being a bit too naive I thought by Dan DeLuca) originally suggests targeting youths between the ages of 18 and 22, not realizing that by that point, if they are in the game, they are long gone. An encounter with a hardened member of that age group soon changes his mind and while he still thinks high school, Bunny suggests going even younger and accepts the assignment, which will take place at Edward J. Tilghman Middle School, where Prez now is working as a math teacher. One of the episode's funniest moments comes when Assistant Principal Marcia Donnelly (Tootsie Duvall) braces herself for the opening of the school's doors for the school year, standing like a statue at the top of the stairs leading from the doors, pausing only long enough to cross herself. Prez's first day predictably is rough with his hard-to-control class, though Randy already makes nice with the teacher while he's palming a handful of hall passes so he can sneak out to other grades' lunch periods to hawk his snack foods. The real problem though comes from two of the girls, one of whom (and I wish I could find the actress's name) has one of the meanest glares I've ever seen. The class also includes Dukie, the object of much derision because of his "odor." It's not just the kids who are mean to Dukie either — when the three teens show up at Namond's house in the morning to go off to school together, Namond's mom refuses to let Dukie in. Dukie also provides one of the episode's most touching, quiet moments when after an act of violence in the class, he sits down on the floor next to the perpetrator and uses a battery-operated hand fan he found to cool her off before leaving it beside her as a gift. In one other school-related moment, we learn that McNulty didn't snag the binder for his own sons but for the children of Beatrice Russell (Amy Ryan), the port patrol officer from Season 2 whose doorstep McNulty showed up on at the end of Season 3.

Administrative changes are happening all over Baltimore, both on the streets and in the police department. Rawls lives up to his suggestion to Burrell and sends a hard-ass arrest-oriented officer, Lt. Charlie Marimow (Boris McGiver), to take over as head of the Major Crimes Unit. He even tries to sell the department switch to the retirement-obsessed former head as a promotion. Needless to say, Lester and Kima are not pleased and start immediately looking for their lifeboats, with Lester going first to homicide. Rawls — if he is to believed — tells Lester he actually respects his work, but not his gift for martyrdom. Kima seeks help from Daniels, who says she's too good to go back to the streets. Daniels asks Rawls to find a good spot for Kima, perhaps in homicide, but Rawls says he's just filled that vacancy before reconsidering and telling Daniels, "Let's see who I don't love no more." In the mayor's office, Herc finally is called into a post-fellatio meeting with Royce, who also has ordered his staff to play dirty with Carcetti, tearing down campaign signs, towing cars in front of his headquarters and sending work crews to tear up his sidewalk. Of course, neither Herc nor Royce acknowledge the true reason behind their meeting as Herc tells Royce about his low rank on the sergeant's list which Royce promises he can take care of, telling Herc that he's too good a policeman to be wasted on chauffeuring politicians around. (A sidenote: By pure happenstance, I caught a first season episode of Homicide: Life on the Street. I had forgotten that Bayless (Kyle Secor) had come to the homicide department from the mayor's security detail.)

On the street, which Bodie had to see coming, Marlo starts making noises that Bodie's lonely corner should belong to him so he should join Marlo's team or lose his spot. Bodie seeks help from his supplier, Slim Charles (Anwan Glover), the former Barksdale soldier who escaped the jail cell and now serves as Prop Joe's lieutenant. As Bodie laments the way things used to be, Slim reminds him, "The thing about the old days, they's the old days." Meanwhile, the drug co-op — the Baltimore drug equivalent of the five families in The Godfather meet to discuss an outside threat from New York interlopers — and how to get the independent-minded Marlo on their team, if only for the muscle he can provide.

Tweet

Labels: Amy Ryan, David Simon, HBO, The Wire, TV Recap

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Sven Nykvist (1922-2006)

One of the true cinematographic masters has passed away. Sven Nykvist, who collaborated with Ingmar Bergman an astounding 22 times and won two Oscars as a result, was 83.

His body of work is truly astounding. Amazingly, he only had one other Oscar nomination beside his two wins, for his exquisite work in Philip Kaufman's The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

He was a true working artist, contributing his talents not only to the exceptional films, but to lightweight (and sometimes just plain awful) movies as well such as Sleepless in Seattle, With Honors, Only You, Something to Talk About and the truly dreadful Mixed Nuts, which I hope few of you have ever had the misfortune of sitting through, despite Nykvist's contribution.

He also filmed What's Eating Gilbert Grape, Starting Over, Chaplin and Pretty Baby, a film where his contribution much outweighed the Louis Malle film which gave us Brooke Shields as jailbait.

Nykvist's name always will be remembered in conjunction with the great Ingmar Bergman. Their collaboration began in 1953 on The Naked Night and stretched for more than 30 years through After the Rehearsal. Along the way, he filmed such Bergman classics as The Virgin Spring, Through a Glass Darkly, The Silence, Persona, Shame and Face to Face. He won the first of his two Oscars for filming Bergman's (in my eyes) deadly dull but beautiful to look at Cries and Whispers. I found that film to be a depressing bore, but Nykvist's use of light and color, especially reds, made it at least watchable.

He won his second Oscar for Bergman's masterpiece Fanny and Alexander, a film unlike Cries and Whispers where the film itself equaled the wondrous cinematography Nykvist provided to Bergman's epic tale of two children raised in a theatrical family and at the mercy of a sadistic minister of a stepfather.

Woody Allen, a self-proclaimed Bergman worshipper, also got the chance to employ Nykvist's services four times, the best being on Crimes and Misdemeanors but also including Another Woman, the "Oedipus Wrecks" segment of New York Stories and the truly abysmal Celebrity, where Nykvist's black-and-white cinematography was the only thing worth recommending in what I consider Allen's worst film.

Tweet

Labels: Ingmar Bergman, Malle, Obituary, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Spike's 2nd 2006 home run

By Edward Copeland

Spike Lee has roared back in 2006 in a big way. I had all but written off the talented filmmaker, but then this year brought a one-two punch of a great documentary and a great action film. Inside Man actually preceded his great When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts, but I just caught up with it on DVD and I was impressed. It's probably the film of his I've liked best since his work in the early 1990s.

Looking back at old reviews of his films I wrote at the time, I noticed the recurring theme of fault usually lay with Spike Lee's screenwriting. In the case of Inside Man, he works from a script by first-time screenwriter Russell Gewirtz and it seems to have freed Lee up as a director and he moves this heist thriller along at a breakneck pace with much style.

Sure, he still feels required to use that damn moving sidewalk shot that he's been using in practically every film he's made for more than a decade, but it's so brief that you let it slide. Hell, Lee even manages to get a score from his favorite composer, Terence Blanchard, that enhances the film instead of serving as a suffocating distraction.

The story, which I'll only provide in the vaguest of terms in order to let the movie unfold for those who haven't seen it, concerns the takeover of a Manhattan bank by a team of thieves led by Clive Owen. Thanks to a vacationing detective, Detective Harry Frazier (Denzel Washington) and his partner Detective Bill Mitchell (Chiwetel Ejiofor) get the assignment, despite the fact that Frazier remains under suspicion for stealing some money from a case. The setup seems familiar from many other films, most notably Dog Day Afternoon and more fictional heist tales, but Lee and Gerwitz's script keeps springing surprises on the audience and makes the entire enterprise fresh. On top of the great performances by Washington and Owen, who has to act most of the time beneath a mask, Inside Man also includes a mysterious fixer played by Jodie Foster in her best role in ages and the bank's aging founder (Christopher Plummer) who secures her services to make certain that some things in the bank don't get out with the robbers. I can't recall a performance from Foster that seems less mechanical or embraces glamour the way she does here as Madeline White. Her screen time is limited, but she gives the movie a jolt every time she appears, whether she's opposite Washington, Owen or Plummer.

Still the real star of Inside Man is Spike Lee, who seems to have rediscovered his talent both in fiction and documentary. After many years of disappointments from him, it brings a smile to your face to know Lee still has it. It makes you wish Woody Allen could follow his cue and film someone else's script. Aside from the great movie itself, the DVD offers an often funny commentary by Lee (so much so that he often cracks himself up). He even offers advice (If you ever meet Christopher Plummer, do NOT bring up The Sound of Music) and gives lots of insight as to how shots were set up, asides about gangsta rap and even frequent updates about how the movie crew's baseball team performed. Inside Man provides a great ride — and I for one am grateful that Spike Lee seems to be back and I hope he gets to make his long-sought project with the 93-year-old Budd Schulberg (On the Waterfront) about Joe Louis.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Clive Owen, Denzel, Jodie Foster, Plummer, Spike Lee, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, September 18, 2006

The Wire No. 39: Soft Eyes

BLOGGER'S NOTE: As always, know that spoilers lie below, so don't venture further unless you've seen the episode or don't care if you know what happens.

By Edward Copeland

Season 4's education theme really starts to take hold in the second episode, though in this instance its focus is more on the roles of mentors, both good and bad, than on the learning itself. Again, The Wire looks mostly at the young teens we met in last week's episode. We learn that Namond not only works as a runner for Bodie, he's the son of the incarcerated Wee-Bey (Hassan Johnson), the former Barksdale soldier who went to jail for his part in shooting Kima in Season 1 — and Wee-Bey still obsesses about the care and feeding of his fish. As far as fatherly concern goes, his preoccupation during Namond and his mother's prison visit is that Namond is doing right by Bodie and providing income for his mom since dad is out of pocket.

We learn more about Michael, who is a budding boxer under the tutelage of Cutty (Chad L. Coleman) and has primary responsibility for caring for his younger sibling. Randy remains under the watchful eye of his foster mother. Dukie turns out to be living with a family of junkies. We also meet a fifth teenager — Sherrod (Rashad Orange), a homeless teen that Bubbles (Andre Royo) has taken under his wing — even going so far as to re-enroll him in school pretending he's Sherrod's uncle. Marlo also is making an effort to woo the teens, handing out big wads of cash to them for back-to-school clothes as if he were Hezbollah dumping dollars on Lebanese citizens shelled out of their homes. Michael, however, refuses to take Marlo's money, prompting a tense scene that ends up implying that Marlo respects the lad for turning his nose up at his cash. The other teens have no problem grabbing Marlo's cash. As Namond says, "I'll take any motherfucker's money if he's giving it away," a line that is echoed nearly verbatim when a furious state Sen. Clay Davis (Isiah Whitlock Jr.) goes ballistic when he's served with a subpoena questioning his financial ties to the late Stringer Bell. Davis complains to Mayor Royce, who pressures Burrell to clamp down on the Major Crimes Unit from which the subpoenas came.

Assistant State's Attorney Pearlman finally gets wise that Lester's timing for the subpoenas was no accident — he knew that with election concerns looming over everyone's heads, this was the only time they could get away with serving them without the bosses coming down on them. The bosses are still coming though — with Rawls (John Doman) suggesting to Burrell that MCU needs better supervision.

Royce also opens the show when Herc, assigned to his security detail, walks in on the mayor getting a blow job, prompting Herc to wonder if his days are numbered and seeking advice from his former partner Sgt. Carver, who steers him to a department veteran — Major Valchek (Al Brown). The transformation of Valchek's character has been one of the most fascinating in the history of The Wire. Valchek started out as a minor character, best known for protecting his son-in-law, Prez. Then, in Season 2, Valchek became a petty bureaucrat who launched a vendetta against dock union leader Frank Sobotka (Chris Bauer) over a donation to a church. Beginning in Season 3 and especially this year, Valchek has become a player and a sage, becoming almost like Yoda to Herc about what he saw and giving help to Carcetti.

Carcetti still finds himself depressed over dismal poll numbers, but thanks to a tip from Valchek via, unexpectedly, Sgt. Landesman (Delaney Williams), he manages to score big points in a debate against Royce, though it's unclear who actually is watching. Speaking of Valchek's son-in-law, Prez still is getting orientation tips from other teachers before the school year begins, advising him to keep the students busy because distractions prevent disorder.

Tweet

Labels: David Simon, HBO, The Wire, TV Recap

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, September 17, 2006

Hello Americans by Simon Callow

In the preface to the second volume in his Orson Welles bio, author Simon Callow apologizes for the 11-year wait between installments, wondering if Welles' inability to complete some projects in a timely manner may have infected his biographer. Volume 1, The Road to Xanadu, covered Welles up until the Citizen Kane premiere in 1941. The second volume, Hello Americans, amazingly only takes its subject forward another seven years until Welles' self-imposed exile overseas. Despite that small slice of Welles' history, Hello Americans actually turns out to be a better read than the first volume. Callow promises that he will cover the rest of Welles' life in a third and final volume — but who knows when we'll see that one.

The Road to Xanadu provided many fascinating details about Welles' early life as a prodigy, but it also suffered from Callow's frequent, almost hopeful, speculation that Welles might have been gay or bisexual, not that there would have been anything wrong with that if it had been true. In Hello Americans, the subject never comes up as Callow frequently points out what a heterosexual horndog Welles was, including many affairs during his marriage to Rita Hayworth (including one with Judy Garland).

Still, it's not the gossip that makes this biography worthwhile, it's the detailed rendering of how project after project in the post-Citizen Kane era were taken away from Welles, often caused just as much by Welles' short-attention span as studio interference.

Most everyone knows about the studio butchering of The Magnificent Ambersons, but that film still comes off as a masterpiece despite the interference, which was caused mostly by Welles' distraction overseas trying to put together It's All True during the editing process. However, the most fascinating case of wondering what could have been are the details of what Orson Welles wanted to do with The Stranger. It's an OK film, but if it had been made the way Welles intended, it could have been so much greater.

One of the most fascinating sections of Hello Americans details Welles' massive stage mounting of Around the World in 80 Days, including the brief involvement of producer Michael Todd, who would later make the lame film version of Jules Verne's story. Another fascinating tidbit that either I didn't know or had forgotten was that Welles sold Charlie Chaplin the idea for Monsieur Verdoux and had a brief legal fight over a promised story credit that Chaplin failed to put on the movie as promised.

If there's a weakness to Callow's second volume, it's his tendency for some reason to seek puns for chapter titles like "Wellesafloppin'", but if you ignore the titles and just read the words, it's more than worthwhile. Also, it could have used some better editing. I can excuse the British spellings of words, but there is no excuse for misspelling the names of famous people such as Katharine Hepburn or Vincente Minnelli. I just hope Callow can get us the final volume a bit more quickly than he did the second.

Tweet

Labels: Books, Chaplin, Garland, K. Hepburn, Nonfiction, Welles

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, September 16, 2006

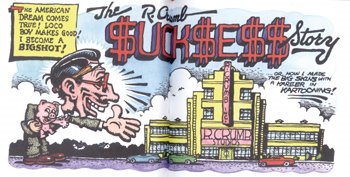

From the Vault: Crumb

Year after year, like clockwork, the annual announcement of the Oscar nominations brings the expected ritual of bellyaching about omissions. In the past decade, critics directed their most consistent shouts at the documentary branch which repeatedly overlooked films they'd actually seen and praised but didn't make the nomination cut. In the 1994 contest, most of the whining commenced on behalf of the impressive sports documentary Hoop Dreams, but there was a better documentary that similarly got the shaft: Crumb, which takes a look at the family and life of underground comic artist Robert Crumb, creator of Fritz the Cat and the "Keep on Truckin'" guy of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Crumb's revenge on the Academy may take the form of box office as it now has received wide theatrical release this year. Gaining an audience for this remarkable film is a much greater reward.

It's also indicative of how, as Hollywood's formula machine churns out more predictable, escapist fare, it has almost become the exclusive responsibility of documentarians to produce real-life stories with the ability to surprise.

David Lynch is one of the producers of Crumb, produced and directed by Terry Zwigoff, and it's easy to see the appeal of this subject matter to that unique filmmaker. The documentary doesn't just plunge into the sometimes racist and nearly always misogynistic work of the eccentric Crumb, but it also focuses on the environment that produced such a mind and shows us his brothers, also artistically inclined but lacking R.'s knack for turning his dysfunction into a career. What makes Crumb so fascinating is that it's more than just a portrait of the artist as a sick man, it's a look at family as well as the pomposity of so-called experts who pontificate about the meaning, both good and ill, in Crumb's work while Crumb stands next to them, shrugging, smiling and arching his eyebrows in humorous exasperation.

The opening shot perfectly illustrates what lies ahead as Crumb sits, rocking on the floor of his house listening to music, one of the few times, he later explains, that he feels any love for humanity. When you first hear R. Crumb's voice, it almost resembles Dustin Hoffman as Rain Man, but R. exhibits more savant than autistic.

The film chronicles Crumb's life and career as the artist and his second wife, Aline, pack up their Winters, Calif., home to move to France, which Crumb describes as "slightly less evil" than the United States, though he insists that's not why he's leaving. It's his disgust with advertising and a lack of intellectual curiosity on the part of Americans.

During the course of the film, Crumb returns to his mother's home where his older brother, Charles, dependent on antidepressants to combat suicidal tendencies, still resides with their mother. Even in Charles' chemically altered state, the hero worship that R. holds for his older brother still shows.

R. Crumb escaped the house, made a name for himself, married and had children, but he's still clearly envious of his troubled brother, something which Charles attributes to Crumb being "so detached from humanity."

What impresses most about Zwigoff's film is that even if you go into it knowing next to nothing about R. Crumb, as I did, you leave feeling you are intimate with the man and all aspects of his life. While his work easily riles a lot of people, the film clearly shows why he's worth studying and, more impressively, raises the idea that art doesn't always come from the purest of intentions.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Documentary, Dustin Hoffman, Lynch, Oscars, Terry Zwigoff

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, September 15, 2006

Pat Corley (1930-2006)

For most people, Pat Corley always will be Phil, the barkeep on Murphy Brown who seemed to know just about everything about anyone in Washington. As great as he was as Phil, to me another performance of his always stood taller — that as the coroner Wally Nydorf, stressed beyond the point of competence, on the great Hill Street Blues. That was my first exposure to the actor and I remember Wally — especially his great scenes with Daniel J. Travanti — to this date.

I also recall another character by Corley in a Steven Bochco work — as the coach in the short-lived Bay City Blues. He also turned in a memorable performance as a dying hit man trying to best an up-and-comer in an early episode of Moonlighting.

While he did appear in a handful of feature films, most of his work was confined to episodic television and he always turned in a good performance and made an impression.

Rest in peace, Pat Corley.

Tweet

Labels: Bochco, Obituary, Television

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, September 11, 2006

The heroism and tragedy of United 93

By Edward Copeland

As luck, DVD release dates, Green Cine queues and the U.S. Postal Service would have it, I caught up with United 93 just in time to review it on really the only appropriate day to review — the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. For a story, that at least in the abstract, so many of us know so well, Paul Greengrass has written and directed quite a compelling motion picture.

What's even more impressive is the approach Greengrass takes, filming it as if there had been hidden cameras in multiple locations five years ago today. At first, the lack of characterization bothered me but as it went on, I came to realize that was the most appropriate course to take — toss in background on the heroic passengers and crews and you could have wound up with a downbeat edition of the Airport franchise.

In fact, the one person who stood out to me as giving the best performance turned out to be the real head of the national air traffic control center in Herndon, Va., Ben Sliney playing himself. Greengrass filled the cast with many of the real people involved that day — air traffic controllers, military, etc. — and when he couldn't fill the parts with their real counterparts, he often looked to their profession. A real United Airlines pilot and a real United Airlines stewardess assume those roles for the film.

The professional actors who do play passengers are, for the most part, faces who look familiar but who aren't stars that would distract from the reality Greengrass presents. Included are Peter Herrmann (at left) perhaps best known as Mariska Hargitay's husband at awards ceremonies, David Rasche (who always will be TV's Sledge Hammer to me) and a don't-blink-or-you'll-miss-her appearance by Rebecca Schull (Fay on TV's Wings).

The IMDb credits also says that Chip Zien, memorable as the original baker in Stephen Sondheim's Into the Woods on Broadway, and Denny Dillon, a cast member briefly on the worst season ever of Saturday Night Live, also were in the United 93 cabin.

Actually, the plotting of the passengers to take back the plane, while suspenseful, turned out to be the least fascinating part of the movie for me, and not just because I knew how it was going to end. What really sets this apart are the scenes showing the confusion and efforts to deal with the horrifying situation on 9/11 at various air traffic control centers and NORAD. The film stays fairly apolitical, with the exception of a rather clueless military liaison that can't give Sliney any answers.

Going into United 93 I considered the question of is a movie like this "too soon," but that evolved more into a question of "is it necessary?" Everyone who knows the stories has their own ideas in their heads about what transpired on the fateful flight, so fleshing it out seems almost redundant. However, in the masterful hands of Greengrass, I ended up answering "No" to that question as well.

United 93 re-visits a horrifying day and presents it with respect and serves as a celluloid monument to that plane's heroic passengers and crew.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Sondheim, Television

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

The Wire No. 38: Boys of Summer

By Edward Copeland

An original episode of The Wire last aired Dec. 19, 2004, but thankfully we have what arguably has become the best drama on television for at least one more season. Unlike The Sopranos, whose delays and hiatuses breed impatience and contempt, each season of The Wire plays like a self-contained unit, so fans could be satisfied in case the show didn't return. Fortunately, it has returned and as in previous seasons, it keeps upping the stakes by adding layers to its complicated Baltimore universe.

Season 1 focused on the Barksdale drug crew. Season 2 added the investigation of union activities at the port. Season 3, with the port story resolved, delved into politics and a drug legalization idea implemented by a police officer nearing retirement. With Season 4, the decimated Barksdale gang has been replaced by that of rising drug kingpin Marlo Stansfield, the political campaign continues and, if that weren't enough, The Wire delves into the state of public schools. The Wire is not a show for casual viewers, but for those who pay attention the rewards are as great as a fine novel. In some ways, the show almost carries a Dickensian tone.

Since this is my first episode recap, I guess this should be the point where I warn everyone that spoilers might lie ahead if they haven't seen the episode in question yet. OK — you've been warned. Since by now the cast has grown so large, I figured before I delve into the episode itself, I'd offer brief updates on the main characters who do manage to get squeezed into the premiere — though many don't show up until later.

McNulty (Dominic West): He's still back in dress blues, working a radio car in the Western District, despite pleas from his new boss to get back to detective work because he's wasting his talents.

Cedric Daniels (Lance Reddick): Speaking of McNulty's new boss, he's the same as his old boss as Daniels has inherited command of the Western District upon Bunny Colvin's retirement.

Detectives Kima Greggs and Lester Freamon (Sonja Sohn, Clarke Peters): They are holding down the fort at the Major Crimes Unit with Sydnor (Corey Parker Robinson), Caroline (Joliet F. Harris) and a disinterested new boss who is more worried about post-retirement construction plans than any cases.

Detective Bunk Moreland (Wendell Pierce): Still as smooth as ever and picking up cases in the homicide division.

Carver and Herc (Seth Gilliam, Domenick Lombardozzi): The Laurel and Hardy of street police teams have split up, with Carver still working the streets and Herc getting a cushy job on Mayor Royce's security detail.

Roland "Prez" Pryzbylewski (Jim True-Frost): Discharged from the force after one screwup too many, Prez is beginning a career as a math teacher in a Baltimore public school.

Assistant State's Attorney Rhonda Pearlman (Deirdre Lovejoy): Still working with the MCU, she's bristling at Lester's plan to issue subpoenas on the eve of the mayoral primary.

Bodie (JD Williams): Pretty much the last man standing from the Barksdale crew, Brodie is trying to make ends meet as an independent dealer on one of the few corners that Marlo hasn't taken.

Marlo Stansfield (Jamie Hector): With the dissolution of the Barksdale crew, Marlo has cemented his hold on large segments of Baltimore drug territory.

Councilman Tommy Carcetti (Aidan Gillen): Carcetti continues his uphill climb in the mayoral race, but finds himself growing more pessimistic about his chances.

Mayor Clarence Royce (Glynn Turman): The incumbent is wielding his power as he seeks re-election, denying Carcetti access to services for his constituents.

As for the fourth season premiere itself, it's definitely setting the season's theme of education with everyone going back to school, even though we're still in the waning days of summer in the first episode. As usual, The Wire excels at contrasting the similarities between different worlds, in this case with a sequence where Prez and his new fellow teachers receive instructions on how to control their classes while Western District officers get a lecture on how to deal with possible terror threats. When a bored Officer Santangelo (Michael Salconi) dumps his binder on terror tips into the trash, McNulty immediately retrieves it, not so he can read up on the procedures but so he can pass along the binder to his kid for school. The first episode also introduces us to some of the new characters whom the bulk of the season will focus on — the kids. You can't have a school storyline without students now, can you? There's Namond (Julito McCullum), who is working as a runner for Bodie, though not to Bodie's satisfaction. "Young'uns don't have a scrap of work ethic," Bodie complains. Randy Wagstaff (Maestro Harrell) is a budding entrepreneur, planning to make some money selling snacks to kids returning to school — though he learns an important lesson when he's unwittingly used for nefarious purposes. The other two kids, Michael (Tristan Wilds) and Dukie (Jermaine Crawford), aren't fleshed out as well in the premiere, though Dukie definitely is the group's preferred target of abuse — until someone outside their group is doing the abusing.

On the streets, Carver continues to keep an eye on Bodie, though his new partner seems ready to pounce on what he perceives as disrespect from the dealer. "You bust every head, who are you going to talk to when shit happens?" Carver asks. Back at the Major Crimes Unit, Lester and Kima are in pursuit of Marlo, who they describe as a "babe in the woods" as far as telephone communications are concerned, but who also is puzzling the detectives with a lack of bodies usually associated with a drug territory takeover. Suddenly though a murder does come their way, only it's one of Marlo's men who takes the bullet and Bunk gets assigned the case.

Lester and Kima also aren't through with the Barksdale investigation, much to Assistant State's Attorney Pearlman's chagrin, as they trick their preoccupied boss into signing off on subpoenas of political figures in the midst of campaign season to solve the riddles of the Barksdale money trail. Pearlman urges them to wait because of the election, which Lester feigns ignorance of even knowing is occurring.

Then again, maybe Lester really is in the dark, if the seniors that Carcetti makes a campaign speech to are any indication. Carcetti's frustration with his campaign is growing, thanks to Royce shutting down his ability to help the constituents in his council district and a lack of money. In fact, Carcetti and Bodie both are sharing similar shortfalls in cash.

Finally, each season of The Wire seems to have a breakout character — Omar in Season 1, Frank and Ziggy Sobotka in Season 2, Bunny Colvin in Season 3. We meet who stands to be the most fascinating creation in the fourth season's very first scene — Snoop (Felicia Pearson, who a close-eyed Wire watcher at The House Next Door pointed out actually did appear in Season 3, though I didn't notice her). Snoop, as we meet her in Season 4, is looking for a better nail gun at a hardware store. It's only later that we realize she works for Marlo as part of his hit team. Snoop looks and sounds like no other character in The Wire's universe and it's interesting to see one that could develop into a rare strong female villain on the show. She — as well as the students — also exemplify what The Wire does so well — it respects its audience by letting them figure out how characters fit in without awkward introductions and exposition. It's good to have the show back and this season (at least what I've seen of it so far) promises to raise the already-great drama to yet another higher level.

Tweet

Labels: Clarke Peters, David Simon, Dickens, HBO, The Sopranos, The Wire, TV Recap, Wendell Pierce

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, September 10, 2006

The Return of The Player by Michael Tolkin

"Physics cracked the atom, biology cracked the genome and Hollywood cracked the story. ... The movies had their run and now the movies are over."

Griffin Mill in The Return of the Player

By Edward Copeland

Griffin Mill has returned, 18 years after first appearing in Michael Tolkin's novel The Player and 14 years after Robert Altman immortalized him in his great 1992 film The Player. Tolkin has written a sequel, The Return of The Player, looking at where Griffin stands today, more than a decade after he got away with killing a screenwriter he mistakenly thought had been threatening him.

I never read Tolkin's original novel but I love Altman's screen version (so it's impossible not to imagine Tim Robbins when you read the sequel, though it's easier not to imagine Greta Scacchi as his now-ex wife June, since she apparently wasn't the cool Icelandic beauty portrayed in the film).

As we pick up Griffin's story, he's now 52, still grinding out a living at a studio but becoming convinced that the world is a dying place. He's also down to his last dollars, thanks to his opulent lifestyle and alimony and child support for June and their two children plus his life with his miserable wife Lisa and their daughter.

Soon, Griffin hits upon a scheme to get into the good graces of a mysterious and rich power broker and starts taking steps to assure that it happens, including a Regina Giddens-type killing of someone who stands in his way.

What puzzles me most is that both his wives seem aware of what he did to the late screenwriter David Kahane in the original, but neither seems to care much including June, who was Kahane's girlfriend after all. Tolkin doesn't even go the trouble of making the case that they are too accustomed to a glitzy lifestyle to raise moral qualms about murder, all the more mystifying since Lisa wants out of her marriage.

Unfortunately, The Return of The Player, while a quick read, doesn't really offer much in the way of entertainment aside from the occasionally well-written passage such as when Griffin thinks to himself at a bar mitzvah:

You see actresses you love, movie stars, powerfully talented, panicked by the injustice of age lines, who go to the wrong plastic surgeon and destroy their careers more completely than death by making themselves look like female impersonators of whom they used to be, their lips puffed as though attacked by swarms of bees from an organic hive, eyelids stapled deep into the sockets, beach-ball bosoms and forehead frozen with Botox into an emotional unintelligibility useful for the championship of the World Series of Poker.

Beyond that, the novel's eventual punchline seemed obvious to me early on, despite the amusing surprise of the real-life person whom Griffin goes to to seek absolution.

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Books, Fiction, Tim Robbins

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, September 08, 2006

Considering Calhern

By Edward Copeland

Tall, debonair Louis Calhern earned his sole Oscar nomination in 1950 for portraying Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in one of the corniest biopics ever, The Magnificent Yankee. Not that Calhern isn't good (as is Ann Harding as his wife), but I can't help but feel this nomination was to make up for the one he didn't get the same year for a much more deserving role as a lawyer, the shady Lon Emmerich in John Huston's great film The Asphalt Jungle. Lon, down on his luck and his cash, hopes to fleece the thieves after their heist so he can vanish far away with his mistress (an early role for Marilyn Monroe). Despite his unscrupulous designs (What happened to honor among thieves?), thanks to Calhern, Lon managed to garner some of the audience's sympathy anyway.

In The Magnificent Yankee, Calhern's Holmes almost becomes a comic figure as it speeds through his 30 years on the Supreme Court, with very little focus on the cases themselves. You just wait for him to mention yelling fire in a crowded movie theater (though it's an opera house in the movie) but you get little more insight into his judicial thoughts as the movie focuses on how he and his wife use the revolving door of clerks to substitute for their lack of children of their own. Perhaps the most surprising thing about The Magnificent Yankee is that it was directed by John Sturges, the man who would go on to make Bad Day at Black Rock, The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape. This film definitely feels at odds with what Sturges accomplished on those films.

Calhern did have an impressive career, appearing in many notable films such as the ambassador of Sylvania in the Marx Brothers' classic Duck Soup as well as roles in The Gorgeous Hussy, The Life of Emile Zola, Dr. Ehrlich's Magic Bullet, 1943's Heaven Can Wait, Hitchcock's Notorious, the title role in 1953's Julius Caesar and his final role as Uncle Willy in High Society, the musicalization of The Philadelphia Story. For me though, The Asphalt Jungle stands as his crowning achievement. It's not that The Magnificent Yankee is bad, it's just corny as hell and seems like it's providing Cliff Notes of a life that I for one would have welcomed learning more about.

Tweet

Labels: 50s, Hitchcock, Huston, Marilyn, Marx Brothers, Musicals

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, September 07, 2006

Three balls, two strikes, two outs

By Edward Copeland

Having read some positive reviews and wondering what a Don DeLillo screenplay would be like, I looked forward to the release of Game 6 on DVD, since the film never played near me. My expectations weren't really that high, but it didn't help. While the movie contains some positive attributes, it never quite jells. Michael Keaton stars as Nicky Rogan, an award-winning playwright whose latest work is about to premiere on Broadway at the same time that his beloved Boston Red Sox are playing in the 1986 World Series. Keaton's performance really is the best thing Game 6 has going for it — he's looser and more wry than I've seen him in a long time.

The great novelist DeLillo has touched upon baseball and America before, most notably in Underworld, and this is his first filmed screenplay, but it feels more like a one-act play — and not a particularly interesting one.

Rogan frets about the play's opening, worrying about a potentially damning review from a harsh theater critic named Steven Schwimmer (Robert Downey Jr.), who has offended so many with his reviews that he basically lives in hiding out of fear for his life, and dealing with a leading man (Harris Yulin) who can't recall his lines because of a brain parasite he caught while in Africa.

Rogan also finds himself estranged from his daughter (Ari Graynor) and dealing with a down-on-his-luck theater associate (Griffin Dunne) who feels Schwimmer destroyed his career.

Directed by Michael Hoffman, Game 6 comes off more as an essay than a movie, though its thoughts on criticism, theater and baseball aren't particularly insightful or entertaining. Thankfully, the film's running time of less than 90 minutes is mercifully short.

In the end, Game 6 puzzled me more than it engaged me. Keaton does deliver his best performance in quite some time, but once the film ended, my main reaction was a ho-hum one. I've already forgotten that I've seen it.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, DeLillo, Griffin Dunne, Robert Downey Jr.

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Bob Dylan's Modern Times

BLOGGER'S NOTE: Welcome to a new contributor here, Jeffrey, proprietor of Liverputty, who contributes an assessment of the new album by the great Bob Dylan.

By Jeffrey Hill

Who came up with the idea that Modern Times was the last installment of a trilogy? I somehow doubt it was Dylan. Was it Columbia? Countless reviews have floated that angle as fact. A few others have questioned it. Certainly, there are traces of the previous two albums in Modern Times: an uptempo bluesy tune such as "The Levee's Gonna Break" would, with a working over from producer Daniel Lanois, blend right in next to Time Out of Mind's "Dirt Road Blues"; the old fashioned melodies of Modern Times' "Spirit on the Water" and "Beyond the Horizon" recall the songs from Love and Theft which gave the former that Gay '90s sound.

That this album, like Love and Theft, seems to be a living specimen encompassing the entire American musical heritage does not mean it's part of a trilogy. Suggesting so diminishes broader trends and developments in Dylan's work. For example, traditional music has always played a fundamental role in Dylan's songs, but it was elevated greatly with the two acoustic predecessors to Time Out of Mind: Good As I Been to You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993). With those two albums, Dylan made it known that he had completely absorbed the Western musical canon and would use it with abandon. Dylan once described music as his religion, and he is a religious man. He's not a preacher but a man whose well runs deep and he draws from it often. The thorough use of tradition is a defining part of this current (or past, now, I guess) "trilogy." Does that mean these last five albums make up a concerted pentalogy? If so, one could trace this trend back to the very beginning of his career, making his entire discography as one massive work without end.

Writing on Dylan can be tricky, as you are always tempted to apply specifics to otherwise vague references. Take Joe Levy, for instance, and this description on the new album:

"The Great Mississippi Flood [of 1927], along with the Charlie Chaplin movie from which the album takes its name and the Book of Revelations, form a triangle of tragedy, comedy and prophecy in which Modern Times unfolds."

Dylan's flood references are generic and apply to the idea of a deluge. He'll parrot a delta blues singer, who likely was referring to the Mississippi floods of the '20s and '30s, in one line, but then he's just as likely to turn right around and sing about the flood as if it was from the ancient world. It is essentially all floods.

And how does Joe Levy assume the album title was taken from Chaplin's film? Could it not as easily be a play on the early 20th century feel of the album — something beyond a basic reference to an iconic movie?

And then there's the Book of Revelations. Levy thinks that a flood equals the end of the world. Since Dylan uses flood metaphors throughout his work, he must always be referring to the end, right? So when Dylan alludes to a rebirth after the flood in "The Levees Gonna Break," Levy considers it an "odd promise." The idea that a flood could act as a cleanser or an agent of redemption is something Levy has seemingly not considered, despite the numerous rainbows he must have seen in his years. I believe Levy, like many other Dylan critics, overstates the apocalyptic visions of Dylan — particularly after Under the Red Sky. That's not to say there is nothing apocalyptic in his latest work, but when critics talk about the Bible, they are usually referring to Revelations. As much or more of the Bible's influence on Dylan manifests itself in harsh imagery reminiscent of the Old Testament. In "Ain't Talkin'," a revenge tale, he sings: "If I catch my opponents ever sleeping I'll just slaughter 'em where they lie" The retribution and the sheer gore of the declaration is something biblical. He often refers to his enemies in a biblical way.

Dylan is a sucker for old social structures and codes. He's constantly making allusions to feudalism, warlords, kings, crime bosses and chiefs, and mixing them into a swirl so the listener is never quite sure what time period he's in, though the emotions conveyed are crystal clear. The law of the land in Dylan's work is harsh, and the methods of survival are even harsher:

"Gonna raise me an army, some tough sons of bitches. I'll recruit my army from the orphanages..."

There's little mercy between the struggle of men in Dylan's landscape. This worldview is not confined to Modern Times or his recent work in general, but is apparent through his entire body of songs. But next to that warrior's code, Dylan maintains a coarse directness, sometimes a raunchiness, that's straight from the essence of Charlie Patton or Howlin' Wolf which he blends with an "aw shucks" 19th century etiquette. He's just as liable to ask for a little sugar in his bowl as he is to take his hat off in the presence of a lady. And then there's the cowboy swing which was front and center in Love and Theft and again is present in Modern Times. He even says he's in a cowboy band.

His talent is so great, and his presence so towering, that it is hard to describe this music in a manner that does it justice. The temptation, for me at least, is to rain down a bunch of superlatives on Modern Times, but that is exactly what I've done with his previous albums going back to Oh, Mercy. At some point superlatives are not enough. How does one convey that Dylan is bigger and greater than his contemporaries? That is the struggle that critics face. Dylan is more than just his legacy, though it is almost impossible to separate his current album from the legend, he's still a pioneering force in popular music. He doesn't try something, reject it and move on, like, say John Lennon. Influences on Dylan tend to stay with him so that the singer on Modern Times has waxed into an impenetrably deep figure. The gut can understand him, but the intellect no longer can. Or as Noel Menger cleverly admitted when alluding to the meaning of the album: "I won't begin to tell you what it's about, and can't."

Which is why you just have to hear it.

Tweet

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

They Went Hathaway

By Edward Copeland

As one of the lesser-known but still solid directors in Hollywood history, Henry Hathaway was best known for his work in Westerns such as How the West Was Won, The Sons of Katie Elder and True Grit, but his filmography was much more eclectic than that including the stiff Prince Valiant and Kiss of Death, the film that introduced the world to Richard Widmark and his Oscar-nominated cackling killer Tommy Udo. Hathaway only received one Oscar nomination for directing in his career and I finally caught up recently with that 1935 film, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and more than 70 years later, it still holds up.

Bengal Lancer, which also received an Oscar nomination for best picture, tells the story of three British soldiers serving with the 41st Bengal Lancers in India, not that any of the soldiers (played by Gary Cooper, Franchot Tone and Richard Cromwell) actually sound British. Cooper is, well, Cooper, though in this movie he goes by the name of Lt. Alan McGregor. In some ways, Cooper reminds me of Kevin Costner with more talent. When he gets really good material to work with as in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town or High Noon, he rises to the occasion. Bengal Lancer is good, but this isn't an actor's movie so not much is demanded of Cooper. Tone, who was nominated the same year for his role in Mutiny on the Bounty and always struck me as a stiff most of the time, gives one of his best performances as the smug Lt. Forsythe. Of the Tone performances I've seen, I think this stands with Billy Wilder's Five Graves to Cairo as his best work. Cromwell does what he can, but he's saddled with the role of the shallow Lt. Donald Stone, son of the regiment's commanding colonel. He's forced to play brash and naive, often turning between the two at a moment's notice and he doesn't quite pull that off.

Sir Guy Standing plays Colonel Stone and he gets some of the film's best moments, actingwise. The scene where he discusses his son with Cooper exhibits damn good acting.

However, what makes The Lives of a Bengal Lancer hold up is not the acting but the action. The Lancers are trying to hold off Muslim invaders and when one of them is captured, they defy orders to try to rescue him and are captured and tortured.

An interesting side note: Inflation must affect Islam as well. When one Muslim is sentenced to death and taunted with a pig, it's mentioned that he wants to stay pure so he can get his "48 maidens from Allah." I guess 24 extra virgins 60-some years later isn't that steep a rise in the cost of dying.

The movie manages to build some nice suspense in several sequences, especially as the Lancers scheme to escape the fortress of Mohammed Khan (Douglas Dumbrille) where they find themselves detained. The film also does something rarely seen in action films made these days — it dares not to let all of its heroes survive.

The Lives of a Bengal Lancer definitely deserves a look if you've got some spare time. For a 71-year-old actioner, it's stood the test of time well.

Tweet

Labels: 30s, Cooper, Widmark, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, September 01, 2006

Buffalo Bob's Wild West Show

By Edward Copeland

Five years after Robert Altman made his Western masterpiece McCabe & Mrs. Miller, he returned to the Old West with Buffalo Bill and the Indians or Sitting Bull's History Lesson. Whereas McCabe was dark and muddy and proved an influence on other Western tales such as HBO's Deadwood (read Matt Zoller Seitz's great interview with David Milch describing the film's influence here.)

Buffalo Bill paints a vivid, bright and colorful canvas of the Old West, focusing on Cody's Old West show, where myth begat show business. In its way, Buffalo Bill aims for a satiric puncturing of the legends, but for most of the film it just seems to lie there.

Granted, anything after Beyond Therapy is a step up, but the movie never seems to find its focus. It finally does come to life more than an hour into its running time with some hilarious scenes involving President Grover Cleveland (Pat McCormick) and produces one truly great sequence toward the end with Buffalo Bill (Paul Newman) having a drowsy conversation with Sitting Bull's ghost in the middle of the night.

In the end, Buffalo Bill and the Indians aspires to be about artifice and fame that is manufactured rather than earned, something which would seem even more relevant today than it was then (John Mark Karr, I'm looking in your general direction), but it never seems to find its footing.

It certainly contains positive attributes that make it worth a look, but it is decidedly a lesser part of the Altman canon.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Altman, Deadwood, HBO, Milch, Newman

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE