Saturday, December 31, 2011

"I never claimed to be one of the 'involved'" — Straw Dogs Part II

its 40th anniversary Thursday. If you haven't seen it and plan to at some point, best not to read this.)

By Edward Copeland

We left off Part I of my Straw Dogs tribute as I was setting up the main players. If you're starting here by accident, click here to go back to Part I first. I also should note, which I failed to do in Part I (though I doubt its specific omission confused any reader) that I'm writing about Sam Peckinpah's 1971 original, not the recent remake which I haven't seen and don't plan to since it violates my rule on remakes: Don't remake films unless the original contained such big flaws that it allowed for improvement, but people seldom remake the bad or the mediocre. Two rare examples where filmmakers remade mediocre or OK originals and ended up with superior versions are Steven Soderbergh's Ocean's Eleven and the Coens' True Grit. Of course, the most famous case belongs to The Maltese Falcon which they didn't get right until the third try directed by John Huston after the awful 1931 version and the strange 1936 adaptation called Satan Met a Lady that changed nearly every detail of the story. Warren Beatty redid Here Comes Mr. Jordan as Heaven Can Wait and it ended up almost as a draw. The most unique case of all happens to be when a very good movie, 1931's The Front Page, got transformed by Howard Hawks into one of greatest comedies of all-time, His Girl Friday. I have to admit — I've enjoyed immensely watching the unnecessary remakes of great films such as Arthur and Fright Night sink like a stone this year. You're probably wondering why I'm wasting so much space in an article about Straw Dogs discussing these other films. That's because despite the spoiler warning at the beginning, some of the art will give things away as well and I wanted to put as much distance between the beginning of Part II and the important stuff as I could since I know how hard it is for some people to use willpower to avoid ruining things they shouldn't know about in a film before they've seen it. Now, I feel I can get back to Straw Dogs after the jump. (FYI: According to IMDb, the 1971 Straw Dogs had an estimated budget of $3,251,794 and worldwide gross of $11,148,828 (and that's largely 1971-72 ticket prices); the 2011 Straw Dogs, according to Box Office Mojo, had a production budget of $25 million and a worldwide gross (at 2011 ticket prices) of $10,324,441.)

Straw Dogs contains few light-hearted moments as it is, but as the film progresses they grow scarce as the tension tightens. The players have arrived, but we aren't sure how they figure in the game yet. Who is Henry Niles and how will he figure into

anything when he shows up in the form of actor David Warner? Should we be wary of more of the villagers than just Norman Scutt, Chris Cawsey and perhaps Tom Hedden? Is Charlie Venner trying to be friendly or does he want to rekindle whatever he used to have with Amy? That will happen, but for that first night, the Sumners continue to have a playful marriage as Amy yells for David to come to bed already, since he has spent hours at work in his study. He doesn't notice that outside the study window, Janice Hedden spies on him, The teenage girl gets surprised by her brother Bobby, who wraps his arms around her. (The two have an unusually close relationship it seems to me.) "Do you fancy him?" Bobby asks his sister, who admits she thinks David is "sweet in a way." As David takes a cup and teapot to the kitchen, the Hedden siblings hike onto the roof. In what may be the most purely comical bit of physical acting Dustin Hoffman (or anyone for that matter) gets to do in Straw Dogs. As David shouts up to Amy, inquiring if she wants him to bring her anything, he throws, tosses and flings fruits and tomatoes at their cat who he clearly disdains. Some pieces he rolls as if he's bowling and as he's leaving the kitchen, he even lobs one behind his back. It's funny since the cat never gets hurt and Hoffman's expression never changes while he's doing it.

anything when he shows up in the form of actor David Warner? Should we be wary of more of the villagers than just Norman Scutt, Chris Cawsey and perhaps Tom Hedden? Is Charlie Venner trying to be friendly or does he want to rekindle whatever he used to have with Amy? That will happen, but for that first night, the Sumners continue to have a playful marriage as Amy yells for David to come to bed already, since he has spent hours at work in his study. He doesn't notice that outside the study window, Janice Hedden spies on him, The teenage girl gets surprised by her brother Bobby, who wraps his arms around her. (The two have an unusually close relationship it seems to me.) "Do you fancy him?" Bobby asks his sister, who admits she thinks David is "sweet in a way." As David takes a cup and teapot to the kitchen, the Hedden siblings hike onto the roof. In what may be the most purely comical bit of physical acting Dustin Hoffman (or anyone for that matter) gets to do in Straw Dogs. As David shouts up to Amy, inquiring if she wants him to bring her anything, he throws, tosses and flings fruits and tomatoes at their cat who he clearly disdains. Some pieces he rolls as if he's bowling and as he's leaving the kitchen, he even lobs one behind his back. It's funny since the cat never gets hurt and Hoffman's expression never changes while he's doing it.

The cat beats David to the bedroom, taking refuge in her bed. Amy lies under the covers, a miniature chessboard on her lap and a book on chess tips in her hands, contemplating what move she should make next against David. He bets her that he can get undressed and do his bedtime exercises (which consists of jumping rope 100 times) before she makes her next move. As she notices how fast he strips, Amy accuses him of cheating so he speeds through his rope jumping and leaps into bed. Amy doesn't believe he did 100, but David says he was using binary numbers. It doesn't matter because Amy makes her move and puts David in check. His response is to close the chess set and start some foreplay — unaware that the Hedden brother and sister hold each other creepily close as they act as voyeurs. David disappears beneath the covers, telling Amy he's looking for a chess piece. "I think I found a rook," he tells her. Peckinpah does another quick insert here as we very briefly pay a visit to the pub where Scutt taunts Venner with the panties that Cawsey stole. We then return to Amy and David's bedroom where they continue their love play, which Amy certainly seems to be enjoying.

Starting at this point in Straw Dogs, characters begin to act without confirmation while the film deprives others crucial information that the audience knows, but they don't. Peckinpah seems to echo this in the editing style as well as events begin to happen that make the viewer feel as if he or she has missed some scenes. The night before, when we last saw Amy and David, they were enjoying each other when the screen faded to black. The next morning, we find them arguing in the studying. "I was just trying to help," Amy tells her

husband. David's tone indicates the fight has been going on awhile as he suggests that if Amy wants to help, she'll get her friends to finish the work on the garage and leave him to his work. She gets up and draws a line with a piece of chalk through his formula, pissing David off further. "Don't play games with me. Don't do it, Amy," David threatens as she finally sticks a glob of gum on the board and leaves. The scene comes as a shock since nothing seems to have foreshadowed it, but the fragmentation has a purpose as we will see as more things develop. For we'll see that pretty much everyone plays a game of some sort. The movie goes from that scene to yet another cut of omission with Amy driving back to the farmhouse. No setup had been given to explain when she left or why — she just storms out of the study and then returns to the farmhouse. What occurred in between remains a mystery, but the scene does call back to the opening one with that inexplicable close-up of her walking braless down a village street. When she parks the car, we get a scene that could be interpreted two ways. Amy notices that her panty hose have developed a run and examines them, unwittingly giving Venner, Scutt, Cawsey and Riddaway a glimpse of her panties. Then again, perhaps she showed her legs and underwear purposely. It earns a tip of the hat from Cawsey, but it causes her to go inside and complain to David in a very important piece of dialogue.

husband. David's tone indicates the fight has been going on awhile as he suggests that if Amy wants to help, she'll get her friends to finish the work on the garage and leave him to his work. She gets up and draws a line with a piece of chalk through his formula, pissing David off further. "Don't play games with me. Don't do it, Amy," David threatens as she finally sticks a glob of gum on the board and leaves. The scene comes as a shock since nothing seems to have foreshadowed it, but the fragmentation has a purpose as we will see as more things develop. For we'll see that pretty much everyone plays a game of some sort. The movie goes from that scene to yet another cut of omission with Amy driving back to the farmhouse. No setup had been given to explain when she left or why — she just storms out of the study and then returns to the farmhouse. What occurred in between remains a mystery, but the scene does call back to the opening one with that inexplicable close-up of her walking braless down a village street. When she parks the car, we get a scene that could be interpreted two ways. Amy notices that her panty hose have developed a run and examines them, unwittingly giving Venner, Scutt, Cawsey and Riddaway a glimpse of her panties. Then again, perhaps she showed her legs and underwear purposely. It earns a tip of the hat from Cawsey, but it causes her to go inside and complain to David in a very important piece of dialogue.AMY: They were practically licking my body.

DAVID: Who?

AMY: Venner and Scutt

DAVID: I congratulate them on their taste.

AMY: Damn rat catcher staring at me.

DAVID: Why don't you wear a bra?.

AMY: Why should I?

DAVID: You shouldn't go around without one and not expect that kind of stare.

It's illustrative in this case only of the Sumners, but all the characters in Straw Dogs want to have it both ways. Those who viewed the film as being about how men must embrace their inner beast to be real men got the underlying message wrong. People who thought that

because Amy parades around without a bra and does other exhibitionist activities meant she secretly wanted to be raped got that wrong as well. First and foremost, Straw Dogs is a thriller, but it is a thriller with a message — that everyone's a hypocrite. Each character — from Dustin Hoffman's math professor to Susan George as his flirtatious wife, from the mischievous teen Janice to the various thuggish locals — wants to have it both ways on almost everything. The figurative straw dogs in Straw Dogs believe that's what's good for the goose is only good for the goose and the gander should back the hell off. That's how a thug such as Norman Scutt can rape Amy, but then help lead a lynch mob to find Henry Niles because they suspect he has molested or hurt Janice Hedden. The David-Amy argument goes on, as Amy accuses David of refusing to commit to anything, though they eventually make up but then, as if she hasn't learned a thing, she goes upstairs to take a shower, dropping her shirt down to David. He tells her to shut the curtains, but she doesn't, given Venner and the other workers a nice look at her naked bosom.

because Amy parades around without a bra and does other exhibitionist activities meant she secretly wanted to be raped got that wrong as well. First and foremost, Straw Dogs is a thriller, but it is a thriller with a message — that everyone's a hypocrite. Each character — from Dustin Hoffman's math professor to Susan George as his flirtatious wife, from the mischievous teen Janice to the various thuggish locals — wants to have it both ways on almost everything. The figurative straw dogs in Straw Dogs believe that's what's good for the goose is only good for the goose and the gander should back the hell off. That's how a thug such as Norman Scutt can rape Amy, but then help lead a lynch mob to find Henry Niles because they suspect he has molested or hurt Janice Hedden. The David-Amy argument goes on, as Amy accuses David of refusing to commit to anything, though they eventually make up but then, as if she hasn't learned a thing, she goes upstairs to take a shower, dropping her shirt down to David. He tells her to shut the curtains, but she doesn't, given Venner and the other workers a nice look at her naked bosom.

It isn't really mocking intellectuals either because every character belittles someone to prove their superiority. In one scene, Amy asks David what binary numbers are and he starts to give an explanation, but she figures out the rest, to which he responds, "You're not so dumb." With the exception of Henry Niles, who is mentally challenged in some way, every character in the movie finds someone to taunt. Even Reverend Hood (Colin Welland) takes a potshot at Tom Hedden during the church social.

REVEREND HOOD: And now for my next trick, the piece de resistance, I present to you an empty glass. I will now fill this glass with milk.

CAWSEY: Would it work better with whiskey, Vicar?

REVEREND HOOD: Nothing works better with whiskey.

TOM: I do.

REVEREND HOOD: You've never worked a day in your life, Tom.

That really, I believe, was Peckinpah's intention in using the title. Everyone selects their weaker argument (in this case, person) to knock down so they substitute themselves as the superior. Occasionally, it takes the actual form of arguments as when Maj. Scott bring Rev. Hood and his wife to the Sumners and David tries to describe his work and it turns into a discussion of the bloody record of the church that gets them to leave quickly.

DAVID: I'm an astral mathematician.

HOOD: Never heard of it.

DAVID: That's because I just made it up. I have a grant to study possible structures in stellar interiors and the implications regarding their radiation characteristics.

HOOD: Radiation. That's an unfortunate dispensation.

DAVID: Surely is. Yes, indeed.

HOOD: As long as it's not another bomb.

[beat]

HOOD: You're a scientist — can you deny the responsibility?

DAVID: Can you?

[beat]

DAVID: After all, there's never been a kingdom given to so much bloodshed as that of Christ.

Peckinpah's direction and his editing team ratchet the tension up to a boiling point, especially during the film's most controversial sequence. Venner and the other workers take David out on his first hunt (though you have to ask why he's willing to go since at this point he knows that one of them hung their pet cat to death and left her in their bedroom closet.

While David sits bored silly out in the country alone like a fool holding a shotgun, Charlie Venner sneaks back to the farmhouse to see Amy. The scene definitely begins as a rape as Amy resists Venner who smacks her around and rips her clothing. Somehow during the course of this, her attitude changes — they did have a past after all — and she even seizes part of the initiative. (It's interesting though that while they have their encounter, she has flashbacks to her encounter with her husband.)

The sequence becomes a sexual assault when Scutt enters with a shotgun. Venner shakes his head, silently urging him not to do it, but Scutt forces him to pin Amy's arms as Scutt sodomizes her, What's happening to Amy gets intercut with David who actually successfully kills a bird, but the act repulses him and he tries wiping the blood off. After they left him stranded, David decides to fire them all the next day — Amy never tells him what happened, so David doesn't realize what an inconsiderate asshole he comes home and starts attacking her over the conduct of her "friends," the workers.

They go to the church social where Amy starts having flashbacks and David decides to take her home. At the same time, Janice, who constantly teases Henry Niles, has left with him, causing an uproar. She takes him to a place and asks if he's ever kissed a girl and he says no and she kisses him. Henry gets frightened when he hears the mob searching for him and accidentally kills Janice, in a way reminiscent of Lennie with Curly's wife in Of Mice and Men and Frankenstein and the little girl by the pond. Niles flees and what brings everything together happens when David strikes Henry with his car. Feeling responsible, he takes the injured man back to the

farmhouse and tries to find the doctor. The lynch mob laid siege to the farmhouse (even though they have no idea about Janice's fate) and Maj. Scott arrives to try to bring things to an end but gets shot to death by Tom instead. What's truly amazing about the climactic siege is that it lasts 35 minutes. As great as Jerry Fielding's score is, most of the climax actually plays without any music. David doesn't have any usual weapons (except Chekhov's mantrap hanging on the wall) and as the mathematician begins thinking of ways to fight back, it's difficult not to think of Walter White and Breaking Bad. At one point, as Scutt tries to break in through a window, David puts a knife to his throat as he binds his hands to the window with wire. He asks Scutt if he's hurting him. My neck's on some glass," Scutt tells him. "Good. I hope you slit your throat," David tells him. He boils alcohol on the stove and flings it on some of the marauders. When you see some of the villager's actions, especially when Cawsey takes to wearing a fake red nose, it's difficult not to picture them as droogs out of A Clockwork Orange. Amy stays torn, wanting to just give Niles to them.

farmhouse and tries to find the doctor. The lynch mob laid siege to the farmhouse (even though they have no idea about Janice's fate) and Maj. Scott arrives to try to bring things to an end but gets shot to death by Tom instead. What's truly amazing about the climactic siege is that it lasts 35 minutes. As great as Jerry Fielding's score is, most of the climax actually plays without any music. David doesn't have any usual weapons (except Chekhov's mantrap hanging on the wall) and as the mathematician begins thinking of ways to fight back, it's difficult not to think of Walter White and Breaking Bad. At one point, as Scutt tries to break in through a window, David puts a knife to his throat as he binds his hands to the window with wire. He asks Scutt if he's hurting him. My neck's on some glass," Scutt tells him. "Good. I hope you slit your throat," David tells him. He boils alcohol on the stove and flings it on some of the marauders. When you see some of the villager's actions, especially when Cawsey takes to wearing a fake red nose, it's difficult not to picture them as droogs out of A Clockwork Orange. Amy stays torn, wanting to just give Niles to them.

AMY: David, give Niles to them. That's what they want. They just want him. Give them Niles, David!

DAVID: They'll beat him to death.

AMY: I don't care! Get him out!

DAVID: You really don't care, do you?

AMY: No, I don't.

DAVID: No. I care. This is where I live. This is me. I will not allow violence against this house.

When, against the odds, David has offed all the intruders, he looks at Amy and says, "Jesus. I got 'em all!" It's clear though that he and Amy probably are finished. As a viewer, you breathe a sigh of relief that one of tensest 30+ minute sequences on film have come to an end. David gathers Niles and puts him in his car to drive him to a doctor and lead to a perfect summation.

DAVID: "It's OK. I don't either.

While The Wild Bunch remains Peckinpah's lasting achievement, it's unfortunate that Straw Dogs, which may be his second best film, languished so long as a turkey, not because the movie failed to meet basic standards of good filmmaking but rather because Straw Dogs became a victim of its time. It was attacked unfairly for having attributes it didn't but those diatribes prevented its assessment purely as a film instead of a polemic. If I'd had more time, I'd be curious if Dustin Hoffman ever spoke at length about the film. Can anyone imagine that he would have agreed to appear in Straw Dogs if it truly were the film its 1971 critics accused it of being?

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Breaking Bad, Coens, David Warner, Dustin Hoffman, Hawks, Huston, Movie Tributes, Peckinpah, Remakes, Soderbergh, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, December 30, 2011

"I'm just glad I'm here where it's quiet…" — Straw Dogs Part I

its 40th anniversary Thursday. If you haven't seen it and plan to at some point, best not to read this.)

By Edward Copeland

When Sam Peckinpah's classic The Wild Bunch opened in 1969, its violence drew much controversy, though many critics saw past the bloodshed to recognize the movie's significance and greatness. Two years later, Peckinpah made Straw Dogs — and it received a near-universal greeting of pans, revulsion and diatribes that accused the film of being a one-dimensional attack on intellectuals and, even worse, an endorsement of the idea that rape victims "ask for it." Liking or disliking a movie always comes down to a person's subjective opinion and ideally — I believe anyway — that assessment should be formed by the artistry (or lack thereof) that's on the screen. When you read the reviews of Straw Dogs from 1971, that seldom seemed to be the case. In fact, many critics who despised the film praised Peckinpah's craft simultaneously. Straw Dogs became the victim of cinematic profiling, watched through the prism of real-world events. People projected views formed by outside experiences onto the movie and slammed it because of what they perceived it to be. There's always been a form of film criticism that chooses to judge movies in a political context and that's fine — it's a free country. However, that school of thought tries to apply that model to every movie, sometimes to the point of ridiculousness (I have good friends who believe that Forrest Gump somehow endorses Reaganism. I belong to the camp that believes if you don't think a film's good, just say so — a negative review need not be complicated with an ideological justification. A movie such as Thor sucks, but politics has nothing to do with why I formed that opinion.) I've went way off topic — this post salutes 1971's Straw Dogs. It's ironic, considering the film's title originated as a variation of the term "straw man," roughly defined as a mediocre argument or idea put out so it can be defeated by a better one. Over the decades, more have recognized the major misinterpretation that Straw Dogs received upon release. Its 40th anniversary offers an ideal opportunity for reassessment and analysis of the film as the complex, layered thriller that I believe Peckinpah made in the first place.

While I'm too young to have seen 1971's films in first run, knowing much of the history, events and certainly the movies that year, violence definitely dominated news and entertainment. Vietnam remained front and center as the South, backed by the U.S., invaded Laos and Cambodia while the war's unpopularity grew with larger protest marches (half-a-million people at one in D.C.) and bigger majorities in polls opposing it (60% in a Harris Poll); according to FBI statistics for 1971, the U.S. murder rate jumped to 8.6 people out of every 100,000, continuing the nonstop rise that began in 1964. Stats also showed that about 816,500 were victims of violent crime and there were 46,850 reports of forcible rape — a crime that often goes unreported which it did then more than it does now; Charles Manson and his followers were convicted and sentenced to death in the Tate-LaBianca murders, though a temporary repeal of capital punishment by the California Supreme Court the following year reverted the sentences to life; Wars were taking place beyond Vietnam. East Pakistan fought Pakistan for liberation, eventually becoming Bangladesh. Later, East Pakistan got into a skirmish with India, but the new country quickly surrendered. another "war" began in the U.S. that still continues when Nixon declared the "war on drugs"; Riots weren't uncommon in the U.S., including one in Camden, N.J., that began after police beat a Puerto Rican motorist to death. A more famous riot occurred at the Attica Correctional Facility in New York when nearly half of the more

than 2,000 inmates seized the prison, taking 33 staff hostages for four days until New York state police retook it. At least 39 people were killed, including 10 hostages; It also was the era of frequent airplane hijackings. Though not a violent one, it was the year the infamous D.B. Cooper got his money and parachuted into oblivion; Coups, usually of the military type, brought down the governments in Turkey, Sudan, Thailand, Bolivia and Uganda, which brought to power Idi Amin. That's not counting the coups that failed. That's just a cursory glance at what an uneasy world it was in 1971. Flowing into this situation were many, many movies, some that played on that fear, others that allowed for a release of that feeling of impotence. A few of the more high-profile examples:

than 2,000 inmates seized the prison, taking 33 staff hostages for four days until New York state police retook it. At least 39 people were killed, including 10 hostages; It also was the era of frequent airplane hijackings. Though not a violent one, it was the year the infamous D.B. Cooper got his money and parachuted into oblivion; Coups, usually of the military type, brought down the governments in Turkey, Sudan, Thailand, Bolivia and Uganda, which brought to power Idi Amin. That's not counting the coups that failed. That's just a cursory glance at what an uneasy world it was in 1971. Flowing into this situation were many, many movies, some that played on that fear, others that allowed for a release of that feeling of impotence. A few of the more high-profile examples:One of my all-time favorite critics is Pauline Kael, though I disagreed with her often, but she was completely off-base in what she wrote about Straw Dogs. I've compiled some of the key things she wrote in her New Yorker review of the film:

"Peckinpah's view of human experience seems to be no more than the sort of anecdote that drunks tell in bars."…"The actors are not allowed their usual freedom to become characters, because they're pawns in the overall scheme."…"The preparations are not in themselves pleasurable; the atmosphere is ominous and oppressive, but you're drawn in and you're held, because you can feel that it is building purposefully."…"The setting, the music and the people are deliberately disquieting. It is a thriller — a machine headed for destruction."…"What I am saying, I fear, is that Sam Peckinpah, who is an artist, has with Straw Dogs, made the first American film that is a fascist work of art."

While Kael mostly missed the mark, she came so close to acknowledging that she did see what Peckinpah's intentions were and that they were artistic ones, that it's almost sad. Let's look at those sentences separately. "Peckinpah's view of human experience seems to be no more than the sort of anecdote that drunks tell in bars." Mainly, that's Pauline doing what she loved to do best (and I admit I can be guilty of succumbing to myself) — thinking up a funny sentence and using it. In relation to Straw Dogs, Kael either was blinded by other factors as to what was on the screen or she refused to acknowledge that the story being told had more layers and complexity than a mere anecdote. I'll flesh out my rebuttal on that later. "The actors are not allowed their usual freedom to become characters, because they're pawns in the overall scheme." She's absolutely right here, but she's also being dishonest because as avid a moviegoer as she was she knew that not every film acts as a character study full of finely drawn portraits of the people inside. The woman who routinely answered the question, "What's your favorite film?" with 1932's Million Dollar Legs starring Jack Oakie and W.C. Fields isn't looking for that in every type of movie, especially a genre film and Straw Dogs belongs in the thriller family, albeit one with depth, intelligence and things to say. "The preparations are not in themselves pleasurable; the atmosphere is ominous and oppressive, but you're drawn in and you're held, because you can feel that it is building purposefully." Kael contradicts herself in the same sentence. All movies aren't designed to be pleasure rides, but they still can be enriching. It's the scenario I always posit among friends: You've gathered for a fun evening and you feel like watching Spielberg. What do you put in the DVD player — Jaws or Schindler's List? Just because you settle on Jaws doesn't mean that Schindler's isn't good, it's just not the type of movie you watch for a rollicking good time. The contradiction comes when she

describes the atmosphere as "ominous," which would seem perfectly natural for a thriller and then admitting it held her attention because she could tell it was building toward something with a purpose. As I said, she was so close. That's exactly what Peckinpah was doing and did. "The setting, the music and the people are deliberately disquieting. It is a thriller — a machine headed for destruction." Finally, Pauline acknowledges that Straw Dogs is a thriller and within those two sentences, she doesn't say anything that indicates she thinks Peckinpah violated the rules of a thriller. The last sentence of Kael's that I excerpted shows where she hopped onboard a train to crazytown. "What I am saying, I fear, is that Sam Peckinpah, who is an artist, has with Straw Dogs, made the first American film that is a fascist work of art." Again, she admits Peckinpah's artistry but she claims he has used that gift to make a "fascist work of art." No wonder she prefaced that with "I fear" because one gift Kael always had, even when you disagreed with her (other than great writing skills) is that she made you re-think your opinion. She didn't necessarily change your mind, but she gave you ideas to mull. Her Straw Dogs review provides a rare example where I didn't believe that she believed the words she placed in print. Her review reads as if she wanted Straw Dogs perceived simply as a macho appeal to give in to our violent nature and a screed against intellectuals. That's what she wanted to see, but her heart and her brain seem to be having a wrestling match for control over her writing. The adjective fascist got bandied about a lot in reviews of Straw Dogs. I can see how some slapped that label onto Dirty Harry, even if I think that was an overreaction as well, because Dirty Harry carries political overtones and a point-of-view, but, as I said before, I believe films should be reviewed as films and ideology should stay out of it. What does it say then that a true fascist film such as Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will is a staple of film studies not because of content but technique? The adjective fascist should appear if a character in the movie has fascist characteristics or is a fascist, but to label a movie one — to me that's nearly as offensive as when Tipper Gore, James Baker's wife and the rest of the PMRC wanted to interpret what songs meant in the 1980s and institute stringent record labeling. As Frank Zappa said about their plans at the time, "It's like treating dandruff with decapitation." It also reminds me of what Jon Stewart said about politicians of both parties comparing opponents to Hitler. By doing that, they do a disservice to Hitler, he said, "who worked long and hard to be that evil." With that out of the way, it's high time I start talking about what actually happens in Straw Dogs. Before I do, I will say this: a bit of a pass can be given to Kael and other critics who shared her opinion and lay siege to Straw Dogs for all its perceived sins since the version that they saw wasn't the one I did. Peckinpah had to cut footage to avoid an X rating but on home media, they restored that scene. Granted, it might have elicited the same reaction, but the fact remains that when I saw Straw Dogs the first time, I literally didn't see the same cut that the critics of 1971 did — and the scene excised in 1971 got removed from the film's most controversial and debated scene, leaving only the ambiguous sexual assault that seems to turn consensual and omitting the second thug who undeniably commits rape.

describes the atmosphere as "ominous," which would seem perfectly natural for a thriller and then admitting it held her attention because she could tell it was building toward something with a purpose. As I said, she was so close. That's exactly what Peckinpah was doing and did. "The setting, the music and the people are deliberately disquieting. It is a thriller — a machine headed for destruction." Finally, Pauline acknowledges that Straw Dogs is a thriller and within those two sentences, she doesn't say anything that indicates she thinks Peckinpah violated the rules of a thriller. The last sentence of Kael's that I excerpted shows where she hopped onboard a train to crazytown. "What I am saying, I fear, is that Sam Peckinpah, who is an artist, has with Straw Dogs, made the first American film that is a fascist work of art." Again, she admits Peckinpah's artistry but she claims he has used that gift to make a "fascist work of art." No wonder she prefaced that with "I fear" because one gift Kael always had, even when you disagreed with her (other than great writing skills) is that she made you re-think your opinion. She didn't necessarily change your mind, but she gave you ideas to mull. Her Straw Dogs review provides a rare example where I didn't believe that she believed the words she placed in print. Her review reads as if she wanted Straw Dogs perceived simply as a macho appeal to give in to our violent nature and a screed against intellectuals. That's what she wanted to see, but her heart and her brain seem to be having a wrestling match for control over her writing. The adjective fascist got bandied about a lot in reviews of Straw Dogs. I can see how some slapped that label onto Dirty Harry, even if I think that was an overreaction as well, because Dirty Harry carries political overtones and a point-of-view, but, as I said before, I believe films should be reviewed as films and ideology should stay out of it. What does it say then that a true fascist film such as Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will is a staple of film studies not because of content but technique? The adjective fascist should appear if a character in the movie has fascist characteristics or is a fascist, but to label a movie one — to me that's nearly as offensive as when Tipper Gore, James Baker's wife and the rest of the PMRC wanted to interpret what songs meant in the 1980s and institute stringent record labeling. As Frank Zappa said about their plans at the time, "It's like treating dandruff with decapitation." It also reminds me of what Jon Stewart said about politicians of both parties comparing opponents to Hitler. By doing that, they do a disservice to Hitler, he said, "who worked long and hard to be that evil." With that out of the way, it's high time I start talking about what actually happens in Straw Dogs. Before I do, I will say this: a bit of a pass can be given to Kael and other critics who shared her opinion and lay siege to Straw Dogs for all its perceived sins since the version that they saw wasn't the one I did. Peckinpah had to cut footage to avoid an X rating but on home media, they restored that scene. Granted, it might have elicited the same reaction, but the fact remains that when I saw Straw Dogs the first time, I literally didn't see the same cut that the critics of 1971 did — and the scene excised in 1971 got removed from the film's most controversial and debated scene, leaving only the ambiguous sexual assault that seems to turn consensual and omitting the second thug who undeniably commits rape.

The opening credits always remind me of parts of the beginning of The Wild Bunch, the titles themselves specifically naming that film's actors in semi-black-and-white (or more accurately, black-and-gray) freezes while they're on horseback. No actors lurk beneath the monochrome credits of Straw Dogs — where we first hear Fielding's foreboding score — but beneath the title cards, blurry images recall the ants overrunning the scorpion at the start of The Wild Bunch. When the picture comes into focus and color, we see that what's scurrying isn't insects but children, singing, dancing and playing with abandon — in a graveyard. Three of the youngsters circle a dog, which some interpret as torture. As someone who despises mistreatment of animals (I always say I've been screwed over by humans far more often than by dogs), it doesn't look that way to me. A few of the kids gaze through the cemetery fence at the activities in the center of the small Cornish village in England. American David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman) walks back toward his car carrying a box of supplies he's picked up while his wife Amy (Susan George), a native of the village, attracts leers as she struts down the street sans bra.

That shot, coming so early in the film, certainly had a lot to do with putting some of the critics in 1971 such as Kael on edge. She admits in her review that part of her reaction to the film probably stemmed from being a woman and if Peckinpah had placed that image of an extreme close-up of the actress's breasts with erect nipples for no apparent reason and it wasn't brought up again, I'd have been offended as well. When I first saw Straw Dogs, the shot took me aback. That looked like something you'd find in a cheap teen sex comedy in the wee hours of the morning on Cinemax, not in a Sam Peckinpah film starring Dustin Hoffman. Eventually though, it is discussed and you see the purpose — and it's not to say "some women want to be raped." We'll get to that later. I'll finish describing the opening sequence first. The teen Hedden siblings, Bobby and Janice (Lem Jones, Sally Thomsett), help Amy by carrying an antique mantrap that she purchased to her car. Charlie Venner (Del Henney) steps out of a phone booth when he catches sight of Amy. He dated Amy when she lived in the town with her father and the sight of her makes Venner salivate. In this very first sequence, Peckinpah and his editing team of Paul Davies, Tony Lawson (who'd go on to edit Kubrick's Barry Lyndon and every Neil Jordan film since Michael Collins) and Roger Spottiswoode (who also edited Peckinpah's Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid before turning to directing) set the quick-cut pattern that will dominate the movie. The director, stereotyped for slow-motion violence, paces much of Straw Dogs with split-second snapshots. Venner makes a beeline for David and Amy's car where Amy introduces Charlie to her husband. David puzzles over the mantrap that Amy bought and tries to place it in the backseat of the car with Bobby's help. David then tells Amy he's going to run into the pub to buy some cigarettes and David leaves her with Charlie, who shamelessly flirts with Amy and tries to get her to re-create old times.

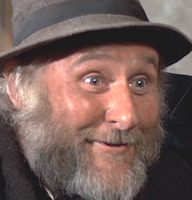

When David steps into the pub, he definitely feels and looks out of place — but it's not because he's wearing a sign that reads BRILLIANT MATHEMATICIAN STUDYING THEORIES YOU PEOPLE COULD NEVER COMPREHEND. No, his clothing, his look, his voice — they all point him out as someone who doesn't hail from that Cornish village as he asks for "Two packs of American cigarettes." However, no one taunts him or mocks him — they have a bigger troublemaker to deal with, one of their own. The burly, bearded Tom Hedden (Peter Vaughan), father to Bobby and Janice and the town drunk, somehow manages to maintain a degree of respect from those younger than him. As David has entered for his smokes, Tom wants another round after

the pub's owner, Harry Ware (Robert Keegan), announces closing time for the afternoon. Tom slams his mug down, breaking it and cutting Harry's finger. As David witnesses this, Charlie enters the pub and asks how the work on David and Amy's garage is progressing. David complains that the two men working on it seem to be dragging their feet and Charlie volunteers to come up the next day with his cousin to help them pick up the pace. Sitting quietly in the pub, observing everything, happens to be the town's magistrate, Maj. John Scott (T.J. McKenna). Tom isn't going to take no for an answer, so he flips up the opening to the bar and serves himself. Scott warns Tom that he's had his fun, but he best be off or he'll have to bring charges and Charlie and another man help the drunkard out, but not before he apologizes to Harry and leaves money for the damage as well as David's cigarettes. Vaughan plays Tom well, straddling that line between charming old lush and frightening bastard. After they've left, David gives Harry the money for the cigarettes. The pub's owner tells him he's already been paid. "You have now," David says before leaving. Most of the actor's work has been in British television productions, though he did appear in Time Bandits and Brazil for Terry Gilliam and the HBO series Game of Thrones.

the pub's owner, Harry Ware (Robert Keegan), announces closing time for the afternoon. Tom slams his mug down, breaking it and cutting Harry's finger. As David witnesses this, Charlie enters the pub and asks how the work on David and Amy's garage is progressing. David complains that the two men working on it seem to be dragging their feet and Charlie volunteers to come up the next day with his cousin to help them pick up the pace. Sitting quietly in the pub, observing everything, happens to be the town's magistrate, Maj. John Scott (T.J. McKenna). Tom isn't going to take no for an answer, so he flips up the opening to the bar and serves himself. Scott warns Tom that he's had his fun, but he best be off or he'll have to bring charges and Charlie and another man help the drunkard out, but not before he apologizes to Harry and leaves money for the damage as well as David's cigarettes. Vaughan plays Tom well, straddling that line between charming old lush and frightening bastard. After they've left, David gives Harry the money for the cigarettes. The pub's owner tells him he's already been paid. "You have now," David says before leaving. Most of the actor's work has been in British television productions, though he did appear in Time Bandits and Brazil for Terry Gilliam and the HBO series Game of Thrones.

It takes a bit of a drive to get to Amy and David's farmhouse and since she's driving, Amy takes her husband on a fast and wild ride to get there, partly as punishment for his queries about her past with Charlie Venner. Before they get to the farm, Amy finally admits that years ago when she lived there, Charlie made a pass at her. David and Amy appear a rather unlikely couple, but in rare moments like this or when they're getting romantic, the two do show signs of sexual compatibility. In other instances, not so much. The screenplay by

Peckinpah and David Zelag Goodman, based on the novel The Siege of Trencher's Farm by Gordon M. Williams, makes a point of showing that David doesn't respect Amy intellectually and, more than likely, views her as a sex object as much as the leering village thugs do. When the couple arrive at the farm, one of the two workers, Norman Scutt (Ken Hutchison) stands at attention on top of the garage. Amy makes a point of making out with David in the car in full view of Norman, though you can tell it makes her husband uncomfortable. The Sumners get out of the convertible and head separate directions — Amy to the house, David to inform Scutt of his incoming help. When David tells Scutt that Venner and his cousin will be arriving the next day to help him pick up the pace on the garage project, Scutt tells him that he and Mr. Cawsey don't have that much more to do. The name doesn't ring a bell with David, but Amy bumps into Mr. Chris Cawsey (Jim Norton) inside the farmhouse. When Cawsey steps outside, David remembers, "The rat man!" Cawsey helps Scutt on the garage, but his main skill involves exterminating rodents. Scutt asks David if he needs help unloading the mantrap (which really should be referred to as "Chekhov's mantrap" since you know its antique metal teeth shall clamp down on someone before the movie ends) and he gladly accepts. Cawsey explains that the mantraps were set them out in the field to catch poachers. As the three men stand alone outside, Straw Dogs comes as close as it ever will to explicitly discussing current world events occurring in 1971.

Peckinpah and David Zelag Goodman, based on the novel The Siege of Trencher's Farm by Gordon M. Williams, makes a point of showing that David doesn't respect Amy intellectually and, more than likely, views her as a sex object as much as the leering village thugs do. When the couple arrive at the farm, one of the two workers, Norman Scutt (Ken Hutchison) stands at attention on top of the garage. Amy makes a point of making out with David in the car in full view of Norman, though you can tell it makes her husband uncomfortable. The Sumners get out of the convertible and head separate directions — Amy to the house, David to inform Scutt of his incoming help. When David tells Scutt that Venner and his cousin will be arriving the next day to help him pick up the pace on the garage project, Scutt tells him that he and Mr. Cawsey don't have that much more to do. The name doesn't ring a bell with David, but Amy bumps into Mr. Chris Cawsey (Jim Norton) inside the farmhouse. When Cawsey steps outside, David remembers, "The rat man!" Cawsey helps Scutt on the garage, but his main skill involves exterminating rodents. Scutt asks David if he needs help unloading the mantrap (which really should be referred to as "Chekhov's mantrap" since you know its antique metal teeth shall clamp down on someone before the movie ends) and he gladly accepts. Cawsey explains that the mantraps were set them out in the field to catch poachers. As the three men stand alone outside, Straw Dogs comes as close as it ever will to explicitly discussing current world events occurring in 1971.NORMAN: I hear it's pretty rough in the States.

CHRIS: Have you seen any of it, sir? Bombing, rioting, sniping, shooting the blacks. I hear it isn't safe to walk the streets, Norman.

NORMAN: Was you involved in it, sir? I mean, did you take part?

CHRIS: See anybody get knifed?

DAVID: Only between commercials. (after some talk concerning the mantrap) No, I'm just glad I'm here where it's quiet and you can breathe air that's clean and drink water that doesn't have to come out of a bottle.

David meekly flashes a peace sign and goes inside where Amy calls for the pet cat, who is nowhere to be found. Though the scene has moved inside, we hear the first line of dialogue between Cawsey and Scutt in the yard. Cawsey asks Scutt if he plans to "have a crack" at

Amy. "Ten months inside" were enough for him," Norman replies, apparently referring to jail time. He then inquires if Cawsey saw anything in the house worth stealing and Chris answers no except for one item. He then twirls a pair of panties around his finger. Scutt calls him an idiot, but Cawsey assures him she has plenty and won't notice. "Don't you want my trophy?" Cawsey asks. Scutt says he'd rather have what goes in them. Cawsey tells him that Charlie Venner had a go at her when she lived there with her father and Scutt gets testy. "Venner's a bloody liar and so are you." Tensions in the house simmer more subtly. Amy continues her search for the cat and David mutters, "I'll kill her if she's in my study." Amy inquires as to what he said, pretending she didn't hear, but he doesn't repeat it, but she obviously did because she changes a plus sign in the equation on his study's blackboard to a minus sign. Later, Amy comes and annoys David in his study while he's trying to work. Finally getting the hint, she leaves, though David gazes out the window and sees she's laughing with Scutt and Cawsey who just sit on a wall, not working. She warns them that David will think that they're lazy.

Amy. "Ten months inside" were enough for him," Norman replies, apparently referring to jail time. He then inquires if Cawsey saw anything in the house worth stealing and Chris answers no except for one item. He then twirls a pair of panties around his finger. Scutt calls him an idiot, but Cawsey assures him she has plenty and won't notice. "Don't you want my trophy?" Cawsey asks. Scutt says he'd rather have what goes in them. Cawsey tells him that Charlie Venner had a go at her when she lived there with her father and Scutt gets testy. "Venner's a bloody liar and so are you." Tensions in the house simmer more subtly. Amy continues her search for the cat and David mutters, "I'll kill her if she's in my study." Amy inquires as to what he said, pretending she didn't hear, but he doesn't repeat it, but she obviously did because she changes a plus sign in the equation on his study's blackboard to a minus sign. Later, Amy comes and annoys David in his study while he's trying to work. Finally getting the hint, she leaves, though David gazes out the window and sees she's laughing with Scutt and Cawsey who just sit on a wall, not working. She warns them that David will think that they're lazy.

When she returns to the study, he asks what the three of them found so funny. "They think you are strange," Amy tells him. "Do you think I'm strange?" David inquires of his wife. "Occasionally," she replies. He says she's acting like she's 14, which prompts her to chomp her gum louder, and he lowers her age to 12. "Want to try for 8?" She leaves him alone to his work, though later she calls to him that she needs some lettuce to prepare dinner. David gets up to fetch some from their tiny greenhouse when he notices the change on the chalkboard. "She's playing games now? What is this — grammar school?" he mumbles as he corrects the equation. When he gets to the greenhouse, Norman Scutt informs him that Riddaway (Donald Webster) has arrived to take he and Cawsey home. Cawsey stops by to share some odd little information with David. "I feel closer to rats than to people, even though I have to kill them to make a living. Their dying is my living," Cawsey declares as he climbs into Riddaway's truck and sings a little ditty, "Smell a rat, see a rat, kill a rat/That's me — Chris Cawsey/I'd be lost without em, I suppose/Cleverest thing I've seen around these parts is a rat." Later, Amy beckons David for dinner, but he seems peeved at being dragged from his work again.

A short scene in the pub gets inserted as night falls and a man comes in. Tom Hedden calls to the man, identifying him as John Niles (Peter Arne). He tells him that his brother Henry has been seen around young girls again and he better watch him or they'll have him put away. Tom's oldest son, Bertie (Michael Mundell), says that Henry only was tossing the ball to them, earning an icy stare from his father. John promises that if Henry starts to make any mistake "like he did before" he'll put him away himself. "If you don't, I will," Norman Scutt speaks up. When Henry shows up later in the film, he will be played by an unbilled David Warner in a part that's a million miles removed from his role in the previous Peckinpah film, The Ballad of Cable Hogue.

All of the major players have been mentioned or introduced and for the first time, I'm having to split the tribute to a single film in half. I don't have anything else ready to run anyway. For Part II, click here.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Books, Caine, David Warner, Dustin Hoffman, Eastwood, Fiction, Fields, Hackman, HBO, Heston, Kael, Kubrick, Movie Tributes, Oscars, Peckinpah, Spielberg, Tarantino, Terry Gilliam

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

An antidote for the emptiness of existence — at least for 90 minutes

By Edward Copeland

Seventeen years later…

Woody Allen makes another good movie. That's not entirely true. Since Bullets Over Broadway's release in 1994, I have liked two of his films — Match Point in 2005 and Whatever Works in 2009. However, Midnight in Paris definitely deserves the label as the first great Woody Allen film since Bullets. As Donald Rumsfeld said of the Iraq war, it's been a long, hard slog for Woody fans who used to anxiously anticipate each new Allen offering before his films turned into retreads of previous works and tasted like a fifth night of leftovers. With Midnight in Paris, his muse returns and blesses us with a fully formed, funny, thoughtful piece of cinematic inspiration.

Most people heard the news that Midnight in Paris stood tall in the Allen canon months ago when the film opened, earning raves and becoming his highest-grossing film ever. I had to wait for DVD and retain a healthy skepticism until I saw it. I simply had no other choice. During the nearly two decades that Woody toiled in the artistic wilderness, people burned me far too often by insisting Allen's latest belonged in his win column only to discover the opposite when I viewed the film. After I finished watching Midnight in Paris, it seemed as if those 17 years had been erased magically. I actually had to check IMDb because my brain couldn't conjure the titles of some of the forgettable films he churned out in those years — Small Time Crooks, Melinda and Melinda, Scoop, Cassandra's Dream, You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger. That doesn't even take into account the ones so bad I couldn't bleach the stain they left on my cerebrum such as Celebrity, Curse of the Jade Scorpion and Hollywood Ending. Midnight in Paris washes away those transgressions, clears the slate and renews my hope that inside the 76-year-old filmmaker there still exists things worth saying and movies worth making.

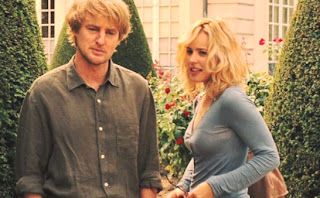

As many of Allen's films that he doesn't star in do, Midnight in Paris features a Woody surrogate and, in what might appear to be an unlikely casting choice, Owen Wilson gets to be his stand-in here. Selecting Wilson as the Woody Allen substitute turns out to be the first of many grand decisions the writer-director makes. In fact, I'll go further and declare that Owen Wilson makes the best faux screen Woody yet (and let's hope we never endure one worse than Kenneth Branagh's in Celebrity). Wilson plays Gil Pender, a successful Hollywood screenwriter with an attractive fiancée named Inez (Rachel McAdams). The couple tag along with Inez's ultra-conservative parents (Kurt

Fuller, Mimi Kennedy) on a trip to Paris where Inez plans to be lazy and sight-see while Gil hopes the City of Lights ignites his first attempt at writing a novel. Paris casts a spell on Pender almost immediately, even though it's raining at the time, something that annoys Inez. "Why does every city have to be in the rain? What's so wonderful about being wet?" asks Inez, a woman Gil unconvincingly describes to strangers as charming but who looks to outsiders as a high-maintenance, judgmental snob. It doesn't take long in France for Gil to suggest that they should move there, but Inez doesn't understand what's so terrible about living in Malibu and being a rich screenwriter, especially with as much trouble as Gil tells her he's having with his novel. "I'm having trouble because I'm a Hollywood hack who never gave literature a real chance until now," he replies. Pender hates his job because he doesn't write anything of value and before we even get to Allen's major themes in Midnight in Paris, he appears to be submitting himself for some self-criticism over his output in recent years. When he made the atrocious Hollywood Ending, the movie was a one-joke notion that the industry had devolved to the point that a director no one realized had gone blind could make a movie and still deliver a box-office smash. In Midnight in Paris, (at least I hope this is the case) he's taken the same complaint and aimed it inward and disposed of it in pieces of dialogue as appetizers to a bigger and better cinematic dinner. (Besides, as far as Hollywood Ending goes, I'd submit Kurosawa and Ran as a counterargument for what blind directors can accomplish.) Gil's novel's plot teases us as to what the main course will be as it tells the story of a man who owns a nostalgia shop, selling memorabilia relating to bygone days.

Fuller, Mimi Kennedy) on a trip to Paris where Inez plans to be lazy and sight-see while Gil hopes the City of Lights ignites his first attempt at writing a novel. Paris casts a spell on Pender almost immediately, even though it's raining at the time, something that annoys Inez. "Why does every city have to be in the rain? What's so wonderful about being wet?" asks Inez, a woman Gil unconvincingly describes to strangers as charming but who looks to outsiders as a high-maintenance, judgmental snob. It doesn't take long in France for Gil to suggest that they should move there, but Inez doesn't understand what's so terrible about living in Malibu and being a rich screenwriter, especially with as much trouble as Gil tells her he's having with his novel. "I'm having trouble because I'm a Hollywood hack who never gave literature a real chance until now," he replies. Pender hates his job because he doesn't write anything of value and before we even get to Allen's major themes in Midnight in Paris, he appears to be submitting himself for some self-criticism over his output in recent years. When he made the atrocious Hollywood Ending, the movie was a one-joke notion that the industry had devolved to the point that a director no one realized had gone blind could make a movie and still deliver a box-office smash. In Midnight in Paris, (at least I hope this is the case) he's taken the same complaint and aimed it inward and disposed of it in pieces of dialogue as appetizers to a bigger and better cinematic dinner. (Besides, as far as Hollywood Ending goes, I'd submit Kurosawa and Ran as a counterargument for what blind directors can accomplish.) Gil's novel's plot teases us as to what the main course will be as it tells the story of a man who owns a nostalgia shop, selling memorabilia relating to bygone days.

While Gil and Inez wander the city with her parents, they bump into Inez's old friends Paul and Carol (Michael Sheen, Nina Arianda) and soon the two couples visit all the sites together where Paul, an unctuous know-it-all on all subjects makes it a point to show off his expertise to anyone and everyone, even telling the tour guide at the Rodin museum (played by French first lady Carla Bruni) that she has her facts wrongs). Paul embodies a 21st century representation of the man pontificating in a movie line in Annie Hall that Alvy fantasizes about bringing Marshall McLuhan out to chastise. Watching the laid-back Wilson do the annoyed Woody dance at this character type not only proves hilarious but a refreshing twist on the familiar routine. Every word Paul utters, of course, enthralls Inez, who believes he's as brilliant as he thinks he is. It's also a nice change of pace for Sheen to play a fictional creation for a change instead of impersonating famous British people. Paul probes Gil about the subject of his novel and at first, Gil resists discussing it, but Inez spills the beans and the movie's argument gets rolling — namely, is the grass really greener in the other era? Gil romanticizes the Paris of the 1920s, when so many great artists from America and elsewhere flocked there. Paul pooh-poohs the notion immediately. "Nostalgia is denial. Denial of the painful present," Paul declares. Inez, the woman who allegedly loves Gil and wants to spend the rest of her life with him, takes Paul's side in the browbeating. "Gil is a complete romantic. I mean he would be more than happy living in a complete state of denial," she says of her fiancé. Paul isn't able to discuss any topic unless he does it at length and in long-winded lectures, so he has to show everyone what he knows of this "syndrome." "The name for this fantasy is Golden Age thinking. The erroneous notion that a different time period is better than the one one's living in now," he pronounces.

Having had enough of being a foursome one night as Paul suggests they all go dancing, Gil begs off, choosing to return to the hotel and perhaps work on his novel. Instead, he walks the streets. As he sits on some steps, a clock strikes midnight and an old yellow Peugeot pulls up as if it's the pumpkin that turned into Cinderella's carriage. The antique automobile bears '20s-era Frenchmen and Frenchwomen (who may have been mice once — who can say?) drinking champagne and beckoning Gil to climb in for a ride. That's when the real sparkle of Midnight in Paris begins and it involves another Woody Allen venture into a magical realm. Gil doesn't speak French, so he's clueless as to what his fellow passengers might be saying as they take him to a party where everyone dresses decidedly retro. Fortunately, most of the other guests appear to be American or at least speak English, so communication isn't a problem. A young man (Yves Heck) sits at a piano, playing and singing, "Let's Do It, Let's Fall in Love." He mentions to one guest that he's a writer and they introduce him to Scott (Tom Hiddleston) and his wife Zelda (Alison Pill) — the Fitzgeralds. Gil finally realizes that

somehow, that mysterious Peugeot took him on a very long drive — one that traveled nearly 100 years in reverse to his ideal Golden Age where he could mix and mingle with his long-dead artistic inspirations. In the past, when Allen employed these fantastical devices it began to feel as if, to paraphrase one of his oldest jokes, he'd resorted to cheating by looking into the soul of the guy sitting next to him, only in these instances, he wasn't seeing another person but staring at himself in a mirror. Magic tricks which first played a key role in the "Oedipus Wrecks" short of New York Stories would return in Curse of the Jade Scorpion and Scoop or, to a lesser extent, assume the form of magical herbs in Alice. Actual Greek choruses would arrive to comment on the action in Mighty Aphrodite or see-through characters would pop up in the form of Robin Williams in Deconstructing Harry. This is a well that Woody drinks from often except that it works best when he employs it in service of larger ideas such as in Zelig, The Purple Rose of Cairo (which I still consider his best film), and, now added to that list, Midnight in Paris. As Midnight in Paris enthralled me, a small detail leaped out early on. In both Purple Rose and Midnight, he names one of the leads Gil. In the case of Purple Rose, most tellingly, the actor that Jeff Daniels plays who creates the role of Tom Baxter, the movie character who steps off the screen and into 1930s New Jersey, bears the name Gil Shepherd, only that Gil embraces his burgeoning stardom and hopes a B-picture such as "The Purple Rose of Cairo" raises his stature high enough to nab the lead in a Charles Lindbergh biopic — as long as his doppelganger in the pith helmet doesn't wreck his career. Gil Pender in Midnight in Paris may work in the same industry, but he fears he's sold his soul to it and he wants out.

somehow, that mysterious Peugeot took him on a very long drive — one that traveled nearly 100 years in reverse to his ideal Golden Age where he could mix and mingle with his long-dead artistic inspirations. In the past, when Allen employed these fantastical devices it began to feel as if, to paraphrase one of his oldest jokes, he'd resorted to cheating by looking into the soul of the guy sitting next to him, only in these instances, he wasn't seeing another person but staring at himself in a mirror. Magic tricks which first played a key role in the "Oedipus Wrecks" short of New York Stories would return in Curse of the Jade Scorpion and Scoop or, to a lesser extent, assume the form of magical herbs in Alice. Actual Greek choruses would arrive to comment on the action in Mighty Aphrodite or see-through characters would pop up in the form of Robin Williams in Deconstructing Harry. This is a well that Woody drinks from often except that it works best when he employs it in service of larger ideas such as in Zelig, The Purple Rose of Cairo (which I still consider his best film), and, now added to that list, Midnight in Paris. As Midnight in Paris enthralled me, a small detail leaped out early on. In both Purple Rose and Midnight, he names one of the leads Gil. In the case of Purple Rose, most tellingly, the actor that Jeff Daniels plays who creates the role of Tom Baxter, the movie character who steps off the screen and into 1930s New Jersey, bears the name Gil Shepherd, only that Gil embraces his burgeoning stardom and hopes a B-picture such as "The Purple Rose of Cairo" raises his stature high enough to nab the lead in a Charles Lindbergh biopic — as long as his doppelganger in the pith helmet doesn't wreck his career. Gil Pender in Midnight in Paris may work in the same industry, but he fears he's sold his soul to it and he wants out.

The first night that Gil takes his trip back to the 1920s he also encounters Ernest Hemingway (played by Corey Stoll in the film's most entertaining performance). Fitzgerald introduces them and Gil gets the envious position of talking writing with Papa in the movie's best exchange on writing that'll appeal to anyone who has ever put pen to paper. It begins with Gil being self-deprecating about the subject of his novel (of course, no one in the 1920s has the faintest idea what a nostalgia shop is), calling it a terrible idea. "No subject is terrible if the story is true and if the prose is clean and honest, and if it affirms grace under pressure," Hemingway tells him. Gil then works up the nerve to ask if the author would look at what he's written and offer suggestionss.

HEMINGWAY: My opinion is I hate it.

GIL: But you haven't read it yet.

HEMINGWAY: If it's bad, I'll hate it because it's bad writing. If it's good, I'll be envious and hate it all the more. You don't want the opinion of another writer.

Hemingway does offer to give Gil's manuscript to Gertrude Stein (Kathy Bates) to read, because he's always trusted her opinion. They agree to meet the following night and Gil leaves but suddenly remembers he forgot to ask Hemingway where to meet him, but when he turns back the coffeehouse has turned into a laundromat and Gil finds himself in 2010 again.

In the morning at his hotel, he attempts to explain his adventure to Inez, asking her what she'd think if he told her he met Zelda Fitzgerald and she's exactly like they had read and Scott really loves her and worries endlessly, but she hates Hemingway because he's right that she's standing in the way of his writing. When Gil completes his enthusiastic rambling, Inez replies, "I'd think you had a brain tumor." Gil manages to convince Inez to go back with him the next night to wait for the Peugeot, but she grows impatient and takes off before the clock strikes midnight. After Inez has left, the Peugeot arrives and takes him to Gertrude Stein's apartment where Hemingway awaits and Pablo Picasso (Marcial Di Fonzo Bo) paints his current mistress Adriana (Marion Cotillard), who catches the eye of both Gil and Hemingway. Despite the many larger-than-life figures than circle Adriana's world, she finds herself just as drawn to Gil — until she learns of his engagement. She also shares Gil's Golden Age thinking, While he thinks that she lives in the greatest time period, she thinks it's awful and wishes she could have been in Paris during the Belle Epoque of the late 19th century. Meanwhile Gil's behavior in the 21st century becomes so bizarre that his father-in-law-to-be hires a private eye to tail him on his midnight walks to see what Gil does on them, since he doesn't trust anyone who says such nasty things about the Tea Party.

Even when Allen had fallen into his long slump, he still had the ability to attract some pretty solid ensembles, not that they were given much to do. In Midnight in Paris, the casting shines with a mix of lesser-known performers and bigger names, all bring their A game to Allen's greatest screenplay in 17 years. In addition to Wilson and Stoll who I've mentioned, the cast's standouts include a zany single scene by Adrien Brody as Salvador Dali, Kathy Bates, Michael Sheen, Rachel McAdams, Marion Cotillard in the first performance she's given that I've enjoyed and, most worth noting, Alison Pill as Zelda Fitzgerald. Pill to me proves again she's an actress just waiting to break out. She's funny and touching here after giving a good dramatic turn in Milk and being part of the fun ensemble in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Given how many great lines Woody's script for Midnight in Paris delivers, it's tempting to rattle them all off, but I'm resisting the urge for those who have yet to see this charmer, but I have to mention one of my favorite gags when Gil runs into a young Luis Buñuel (Adrien de Van) and gives him an idea for a movie — basically the plot of his film

If there has been any debate about Midnight in Paris, it's been where Allen comes down in the end on the question of nostalgia and Golden Age thinking. It seems pretty obvious to me based on what Gil's last line to Adriana is, even though he sends mixed signals by having Paul, the film's most pompous character, ridicule the idea of Golden Age thinking first. Also, as others have pointed out, throughout most of Allen's career his choices in music and references have screamed nostalgia, but Midnight in Paris plays as one of the most entertaining self-critical works any artist has ever made. At the same time, Allen does acknowledge the natural reflex to long for an earlier, better time — if not in another era, at least in one's own life.

Tweet

Labels: 10s, Branagh, Buñuel, Cotillard, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Jeff Daniels, K. Bates, Kurosawa, O. Wilson, Robin, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

Sex, Drugs and Quivering Holes: Cronenberg Puts Burroughs in a Straitjacket

BLOGGER'S NOTE: Naked Lunch was released 20 years ago today. Spoilers start in this essay’s first 25 words, so beware.

By Jeff Ignatius

When a rubbery former typewriter humps two lovers in David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch, and when a grinning Roy Scheider emerges from his woman suit and shouts, “Benway!” near the film’s end, it’s so excessive that the movie seems to jump the rails. Of course, that must be impossible, because the tracks don’t exist, and if there aren’t at least a few Dada moments, something has gone awry. I haven’t read William Burroughs’ 1959 classic, but I imagine one of the great appeals of attempting any adaptation is that it offers a really long leash — just make sure it isn’t conventional, comfortable, boring, straightforward, or coherent.

Cronenberg seems incapable of making conventional or comfortable films, and Naked Lunch is in no way boring or straightforward. It is, however, coherent. The rails do exist — often to the movie’s benefit but finally to its detriment.

The writer/director genetically combined elements of the seminal book with people and events from its author’s life — Burroughslunch instead of Brundlefly — and the result is an uneasy fusion; the chaos of id has been organized and annotated, and the central character has been reduced to a pawn of his addictions and his unconscious mind. The movie is, on reflection, significantly more ambiguous and textured than that, but it’s hard to escape its central contradiction: One of the 20th century’s most important and innovative writers has bizarrely been stripped of ownership.

Burroughs is presented in Cronenberg’s movie as William/Bill Lee (Peter Weller), whose drug use leads to the accidental shooting death of his wife Joan (Judy Davis) and then escalates, sending him fleeing into the fantasy world of Interzone — a place of exotic hallucinogens and fluid sexuality and ever-shifting corporate intrigue and living typewriters and…. Bill’s “reports” as an agent become the novel Naked Lunch, and as he shifts from the roach powder stolen from his exterminator job to “black meat” to alien semen, he drifts further from recognizable reality. “I feel so — oh — severed,” he says at his most wretched. At heart, Cronenberg’s adaptation riffs on the idea of the artist as vessel — a mere conduit for the work. Lee’s art here bursts from a potent potion of drugs, grief, drugs, paranoia, drugs, buried desires, drugs and guilt — although any regret he feels has to be inferred from the convoluted conspiracy built to explain his wife’s death. This conceptual choice — more about the book and author than a presentation of the novel itself — gives the film its structure and narrative resonance. William Lee sheds tears twice, recognizing what he’s done to become and later prove he’s a writer, and it’s a solid story. Yet it’s far too neat and easy, especially for this movie.

Lest it sound as if I don’t like or admire Naked Lunch, let me be clear on a few points.

First, the movie is as repulsively, giddily transgressive as one could hope for from these idiosyncratic artists. Somewhat shockingly, the most obvious barrier to bringing the script to the screen was apparently not much of a problem. Despite unmistakable erections and orifices, blowjobs and cum shots, the damned thing got financed, made, and released — with an R rating, no less. (In the MPAA’s eyes, penises and anuses aren’t penises and anuses if they belong to bugs, typewriters or Mugwumps.)

Second (and largely given), the production design — by longtime Cronenberg collaborator Carol Spier — is sharp and lovingly realized, from the mid-20th century detail to the tactile creature effects to the slightly fake/unreal look of Interzone.

Third, the movie’s eccentricity is balanced by masterful restraint of tone; the strangeness mostly just exists. Howard Shore’s score feels too ripe — the aggressive, digressive jazz sax highlights the oddness — but Naked Lunch’s otherwise-matter-of-fact presentation of outré material reflects William’s accepting mind.

So does Weller’s focused deadpan. The actor creates an aloofness that situates him as both pliant participant and hungry observer — detached but never blank, alternating between downcast eyes and keen attention. Some might see it as a one-note lead performance, but watch each of Weller’s smiles and you’ll begin to see the shadings. And notice the moment he fully surrenders to his hallucinations, when he sells his homosexual “cover” after saying the word “queer” aloud several times — trying it on — before launching into a bravura bit of storytelling. He has become an agent.

Fourth, the movie is surprisingly funny, loaded with perfect touches: the sound of a carriage-return bell when Bill’s scurrying typewriter runs into a door; the casual way a cigarette-smoking Mugwump in a bar is plainly visible but goes unnoticed by William (and likely the audience); the cheeky foreshadowing of Scheider’s reveal — “And he’s obviously got sensational cover,” “She and Benway are…intimates.”

Other humor is dark and pathetic. Bill is fully aware of and barely trying to conceal his true self, for instance offering a lame but clever excuse to an exterminator colleague whose bug powder he tried to steal: “The centipedes are getting downright arrogant.” After Scheider’s Benway suggests that Lee came to him to score dope instead of treatment, Weller fills his response to the doctor with arch insincerity: “I came here for help.” And William downplays his months-long binge and ragged mental state to friends (“Naturally, I’ve had a few odd moments”) and another Joan, also played by Judy Davis (“I suffer from, um, sporadic hallucinations”).

Then there are the careful phrases lightly reinforcing the grip of drugs. Benway describes the side effects of a roach-powder-habit treatment as “nothing that will surprise the addict”; what goes unsaid is that nothing can surprise a roach-powder junkie. A sleazy operator offers “rare services to the arts,” adding: “I have found that writers are a particularly needy group.”

Another strain of humor subtly reflects characters’ acquiescence to the ridiculousness of what’s happening — full submission to the drugs. Early in the movie, a giant bug says, “Say, Bill, do you think you could rub some of this powder on my lips?” Bill replies: “Uh, yeah. Sure.” (You can luxuriate in Peter Boretski’s bug/typewriter/Mugwump line readings. In the example above, just listen to the word “pow-der.”) When Lee’s typewriter attacks a borrowed one, he only considers the awkward social situation this puts him in: “Holy shit! That machine doesn’t belong to me.” Cronenberg’s characters assign great personality to those machines, with language more appropriate to sexual partners. “I wouldn’t use a Clark Nova myself,” says Interzone acquaintance Tom Frost (Ian Holm), the husband of the second Joan. “Too demanding.” He then suggests that William borrow his Martinelli: “Her inventiveness will surprise you.” And it would be impossible not to smile at both the writing and delivery when Bill offers an exchange of writing machines. “I’ve brought you a new typewriter which conveniently dispenses two types of intoxicating fluids when it likes what you’ve written,” he says brightly and casually.

Despite these abundant strengths, Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch feels too processed and too sane.

Least damaging is the tidy, linear progression of Bill’s visions, with each successive drug creating stronger hallucinations. Similarly, periods of lucidity are explicitly marked by the absence or scarcity of narcotics, and trips are immediately preceded by drug use. As weird as the movie is, it clings too tightly to logic, refusing to ever give itself over chaos, depravity, or even narrative messiness. This is obvious in the way the conspiracy finally comes together — in Lee’s dope-dictated universe, it makes sense — and in a pair of related over-expository bits. What William thinks is his ticket to Interzone is shown to be drugs (a touch that just barely works), and a bag that Bill thinks holds the remains of a ruined typewriter is shown to be full of spent drug paraphernalia (too much). These two disclosures serve a secondary purpose through the character of Martin (which I’ll address later in this section), but they’re primarily blunt and unnecessary reminders that drugs are transporting and expressive tools.