Wednesday, June 28, 2006

Philip and John: My two favorite writers

Whenever anyone asks me who my favorite writer is, I generally have two answers. For writing alone, no one stands above John Updike for me. However, if the subject is broadened to novelists, then Philip Roth takes the prize. As luck would have it, both authors recently released new novels, a short tome called Everyman by Roth and a novel called Terrorist by Updike. I figured the occasion was a good enough reason for me to explore my reading relationships with both greats.

My reading relationship with Philip Roth got off to a rocky start. My first exposure to him came in high school when I read Portnoy's Complaint, which I found silly and immature. I never read anything else by him for several years, but about the time American Pastoral started earning acclaim, I decided to give Roth another chance — and boy was I glad that I did. He really grabbed me with American Pastoral and it encouraged me to seek out his older works. Soon, I was immersed in the many worlds of Nathan Zuckerman through the main trilogy, The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman Unbound and The Anatomy Lesson, onto the many other works in which Roth's writer surrogate would appear. Some of my favorite Roths turned out to be ones that didn't involve Zuckerman at all — especially Sabbath's Theater, which may well be my favorite Roth novel, and the incredibly original and hard to describe Operation Shylock and the true-life memoir of his relationship with his aging and dying father, Patrimony. Roth is a great writer — he doesn't have the prose brilliance of Updike, but something about him just grabs you. Sure, some of his books that I've read have bored me, but I've completed every single one I've started. The same can't be said for Updike. What's most amazing to me is how he seems to keep getting better and better. When you think of his recent output such as American Pastoral, The Human Stain and The Plot Against America, it's quite amazing. As for his most recent novel, Everyman, it's a short, good exploration of mortality and a failing body, but it didn't grab me the way many of his other works have. Here is a list of the Roths I've read to completion, along with a three-grade assessment of fair, good or great. I'm not rating Portnoy's Complaint, because I feel I need to give it another chance and I never have.

My first brush with Updike came when he won the Pulitzer for Rabbit Is Rich. I was in junior high and I rushed out and bought the entire trilogy in paperback: Rabbit, Run, Rabbit Redux and Rabbit Is Rich. I attempted to start Rabbit, Run, but I guess I wasn't ready for it at that age yet. The next Updike I picked up was The Witches of Eastwick in high school. I bought the book because I knew a movie version with Jack Nicholson was forthcoming and because my junior English teacher rejected my choice of John Irving's The World According to Garp for a paper. It might be the biggest favor a teacher ever did for me. Once I read Witches, my thirst for Updike came to life. Around the same time, I ended up layed up (I think it was with wisdom teeth, but memory gets fuzzier with age) and my dearly missed friend Jennifer loaned me her copy of Updike's short novel Of the Farm, a beautiful chamber piece that really tossed me into the Updike universe unabated. His writing was a revelation — I don't remember ever reading a writer before him that made me gasp so frequently at the sheer power of his prose. Sometimes, he seemed to overreach, but mostly the sentences he constructed were things of wonder. After that, I threw myself back into the Rabbit Angstrom trilogy and I read all three in quick succession — a fascinating experience. Updike was great from the beginning, but by reading the three books, each written about a decade apart, in short order, you could really watch as his power as a prose stylist took hold. The trilogy, later joined by the fourth and final book, Rabbit at Rest, are considered Updike's crowning achievements and it's hard to argue with that. The four books really mark his most successful merging of his ample writing talent with his novelistic skills, which are sometimes lacking. With five Updike novels under my belt, I was a true Updike obsessive — and this was before Philip Roth had re-entered my reading life. If you've never had a chance, it's worth reading Nicholson Baker's fun book U & I, which describes his reading relationship with Updike and in many ways mirrors my own. He admits that there are some Updike novels he's just never finished and the same is true for me. His writing always is great, but some of the novels just don't hold you the way they should. There are some other great ones such as Couples, A Month of Sundays, Marry Me: A Romance (a personal favorite) and what I think may be his most underrated novel, which I worship, In the Beauty of the Lilies. In the Beauty of the Lilies represents a trend in Updike's work — the need to experiment with different subjects and forms. In the case of Lilies, it works magnificently. In other novels, such as The Coup or Toward the End of Time, I just couldn't get through them. I had intended to hold this post until I completed Terrorist, but that is taking longer than I expected due to circumstances in neither my nor Updike's control. So far, I like it. His prose is sterling as usual, though there are some digressions I've read already that don't quite seem to fit to me. I expect this is an Updike novel I'll finish, not one I abandon and once I do, I'll probably do a separate post just on it. Now, like with Roth, I'm gonna rate the Updike novels I've tried. I'm not including the myriad short story collections or books of criticism or poetry, I'm limiting it to the novels. He's just too damn prolific to go further, though technically the Bech books are collections. One other curious thing I'd like to note when comparing Updike and Roth: While Roth's characters are frequently writers, Updike seems to avoid them like the plague, aside from the Bech books. I wonder what that says about each of them.

Tweet

Labels: Books, Irving, Jennifer, Nicholson, Roth, Updike

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, June 26, 2006

The Prime of Dame Maggie Smith

By Edward Copeland

I recently audited The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie for the first time in a long time — and for the first time in its proper widescreen ratio. While the movie was about how I remembered it, what definitely stood the test of time was the Oscar-winning performance of the great Maggie Smith. While in her later years, she has settled into a certain mode of role for the most part, she's still one of our greats and I regret that I've never been able to see her perform on stage.

As for the movie itself, it's more notable for its acting than its drama, though chunks of the dialogue are quite good. In addition to the great Maggie, there is solid work from her real-life husband Robert Stephens as the caddish art teacher, Celia Johnson as the prim head of the private school and Pamela Franklin as one of her most-seemingly devoted pupils with an agenda all her own.

In fact, the final faceoff between Smith and Franklin may be one of the best acting duets ever put on screen and really gives the film an emotional payoff that it might not otherwise deserve.

Of course, by now the setup of an eccentric, iconoclastic teacher has become a cliche in films such as Dead Poets Society, The Emperor's Club, Mr. Holland's Opus and far too many others to mention by name. Jean Brodie gets by because Smith makes her into such a force of nature that you can't help but stay tuned. Nowadays Maggie Smith is probably best known to younger viewers as Minerva McGonagall in the Harry Potter films, but there is so much more to her worth looking into. (Besides, all British actors are required by law to appear in a Harry Potter film — in fact I believe Paul Scofield is fighting that in court.)

Just three years after Jean Brodie, she earned another Oscar nomination for the delightful Travels With My Aunt. Six years after that, she scored another Oscar win for supporting actress — one of the best supporting wins in my opinion — playing a boozy Oscar-nominated actress on her way to her big night — and she loses. Her scenes with Michael Caine are really about the only thing worth recommending in this otherwise lame Neil Simon outing. Smith had better luck with Simon two years earlier, playing a parody of Nora Charles in the fun spoof Murder By Death opposite David Niven.

She even showed she could do "serious" murder as well, appearing in two Hercule Poirot outings Death on the Nile and Evil Under the Sun with Peter Ustinov. Now, it seems as if Dame Maggie has settled into a groove of upper-crust British roles, earning supporting nominations for Merchant Ivory's A Room With a View and most recently Robert Altman's Gosford Park.

She's not above being a little daring as well, as in her great work in the HBO movie My House in Umbria where she seemed to have no hesitation at flashing viewers a bit of her aging bosom.

Smith is a class act, equally adept at comedy and drama. I hope she can still get some really juicy parts because she deserves them. I still regret that I've never had the chance to see her on stage, so I really hope that she's got some great screen work ahead of her to satisfy me.

Tweet

Labels: 60s, Altman, Caine, HBO, Maggie Smith, Merchant Ivory, Neil Simon, Niven, Oscars, Television

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, June 24, 2006

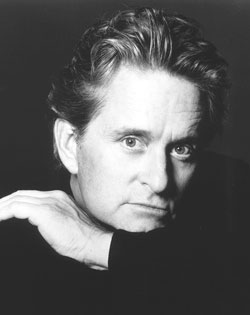

Is Michael Douglas a Male Chauvinist Pig?

By Josh R

Did that get your attention?

When Mr. Copeland enlisted me as a contributor to this forum, he probably didn’t anticipate a post such as this — I think I’m supposed to be more informative than confrontational (trusting sort that he is, he overestimates my better instincts). Well, I can’t always take the classy route. This piece may contain some actual information, but it’s mostly just an old-fashioned hatchet job. Sometimes I like to get up on my high horse and kick up a little mud in people’s faces, especially when I feel such a response is merited.

I guess we’re at the point now where we can legitimately (if somewhat grudgingly) refer to Michael Douglas as a Hollywood legend. So maybe the guy doesn’t have the acting chops of a Dustin Hoffman or a Robert De Niro — or the sex appeal and glamour of a Robert Redford or Warren Beatty. Perhaps he can’t rival any of these gentlemen in terms of old-fashioned movie star charisma. OK, he definitely can’t. Still, one can make the fair argument that he’s earned his place in the pantheon. He is an Academy Award-winning actor and producer whose career spans more than 30 years. In a business where the careers of many actors of his generation have fallen by the wayside, he has weathered an unusual number of flops and misfires to retain his status as an A-List marquee attraction. His résumé also has included its fair share of hits, of both the critical and commercial variety. If the bulk of his work hasn’t demonstrated much beyond a solid professionalism, he has, on occasion, shown himself to be a talented and resourceful actor. He is a mainstay of Hollywood social circles, a mover-and-a-shaker, son of Kirk, and husband to Catherine Zeta-Jones. Whether you like the guy or not, he is, without question, a star.

Which is why it may come as something of a surprise that the man has been rejected by more women than any other man in the history of Hollywood.

It’s not his love life I’m referring to — in fact, reputation holds that he’s done fairly well in that department (to the point that his pre-nuptial agreement with Ms. Zeta-Jones is known to include an infidelity clause). The rejection that Mr. Douglas has suffered at the hands of Hollywood’s female acting elite has been of a professional nature — and, on at least three (and possibly four) occasions, it appears to have been deserved.

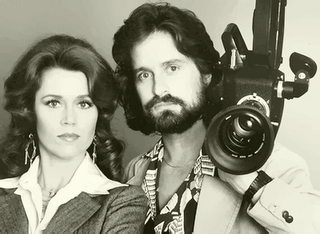

The lead role in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, produced by Mr. Douglas and for which he received the Academy Award for best picture, was turned down by (in alphabetical order) Anne Bancroft, Ellen Burstyn, Colleen Dewhurst, Faye Dunaway, Jane Fonda, Angela Lansbury, Jeanne Moreau and Geraldine Page. Most of the actresses cited personal reasons for their refusal, ostensibly because of the nature of the material.

Ken Kesey’s novel had ignited a firestorm of controversy upon its publication in 1963, mainly due to its depiction of the character often referred to only as "Big Nurse," the sadistic ogre who presides over a mental ward populated by male patients. In Nurse Ratched, whose ugly countenance was described in almost as much detail (if not as frequently referenced) as her large, fleshy tits, Kesey had fashioned an interpretation of the female authority figure as an emasculating control freak, with no attempt to understand or get to the root of her behavior. As written by Kesey, critics observed that the character had about as much dimension as the Wicked Witch of the West. Since the novel’s debut on the best seller list coincided with the advent of the women’s movement, feminist activists had a field day denouncing what they (correctly) perceived as a monstrous disservice to the cause of women’s advancement in the professional arena. At the end of the novel, Ratched is raped by McMurphy — as imagined by Kesey, the assault is less an act of violence than an act of justice, retribution for her "rape" of the inmates in her charge. It’s a rape that the reader is supposed to cheer for.

Needless to say, by 1975, this wasn’t going to fly, so Douglas and his collaborators had to soften the material considerably. The character’s fiendish, subhuman bullying (with accompanying grunting) was replaced with a more subtle form of villainy, and the rape was jettisoned in favor of strangulation. Nevertheless, no major actress of the period was willing to go anywhere near it — some demurring politely, others expressing

indignation that the film was being made in the first place. Joanne Woodward was never offered the role of Nurse Ratched — the story goes that she’d already taken herself out the running with a preemptive strike before the production team had even had the chance to approach her. Having gotten wind of the fact that her name had been bandied about in a casting session, she reportedly told Douglas that not only had she no intention of taking the role, she had no desire of even seeing the finished product. The role eventually was filled by an unknown, Louise Fletcher, who won an Academy Award for her performance before promptly returning to obscurity. The previous year’s winner, Ellen Burstyn (who had been among the first to take a pass on the film), went on television and asked Academy members not to vote in the best actress category to protest the lack of good roles for women. Fletcher later related to The New York Times, in reference to a conversation she’d had with Burstyn after the latter’s comments, “She hadn’t even seen Cuckoo’s Nest because she thought it would be too painful an experience. I told her that I thought it would have been nicer if she’d said what she said in a year when she had been nominated.”

indignation that the film was being made in the first place. Joanne Woodward was never offered the role of Nurse Ratched — the story goes that she’d already taken herself out the running with a preemptive strike before the production team had even had the chance to approach her. Having gotten wind of the fact that her name had been bandied about in a casting session, she reportedly told Douglas that not only had she no intention of taking the role, she had no desire of even seeing the finished product. The role eventually was filled by an unknown, Louise Fletcher, who won an Academy Award for her performance before promptly returning to obscurity. The previous year’s winner, Ellen Burstyn (who had been among the first to take a pass on the film), went on television and asked Academy members not to vote in the best actress category to protest the lack of good roles for women. Fletcher later related to The New York Times, in reference to a conversation she’d had with Burstyn after the latter’s comments, “She hadn’t even seen Cuckoo’s Nest because she thought it would be too painful an experience. I told her that I thought it would have been nicer if she’d said what she said in a year when she had been nominated.”

Fatal Attraction is perhaps Mr. Douglas’ best-known and most influential film as an actor — for you young’uns out there, it’s about a basically decent guy who cheats on his angelic, idealized homemaker wife with a high-powered cosmopolitan book editor who turns out to be a raving psychopath. General chaos ensues — knives are wielded, children are kidnapped, cars are splashed with acid and beloved household pets are tossed into the crock pot. The role was turned down by Isabelle Adjani, Barbara Hershey, Miranda Richardson and Debra Winger. Richardson, a relative unknown whose involvement with the film might have propelled her to stardom, publicly stated that she found the script “regressive in its attitudes.” While the LA Reader’s John Powers was among those who saw the film as being “about men’s fear and hatred of women,” The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael went a step further in declaring “the film is about men seeing feminists as witches, and the way she’s presented here, the woman is a witch…she parrots the aggressively angry, self-righteous statements that have become commonplaces of feminist fiction, and they’re so inappropriate to the circumstances that they’re proof she’s loco.”

Unlike Cuckoo’s Nest (and Basic Instinct, which I’ll discuss presently), the producers didn’t have to resort to drafting an unknown actress to fill their star role. Glenn Close, who found herself in a bit of a career cul-de-sac after being typecast as the virgin mother (The World According to Garp), the nurturing, all-giving earth mother (The Big Chill), and quite literally, a glowing Madonna (the living embodiment of goodness and decency in The Natural), was desperate to break out of the holding pattern. She aggressively courted the role in a calculated risk that paid big dividends, earning an Oscar nomination for the performance. She’s been happily playing bitches ever since.

The impetus for this piece was seeing Basic Instinct again fairly recently — Douglas’ next monster hit after Fatal Attraction. I’m not sure what I was expecting, although it seemed diverting enough way back in good old 1992. For anyone who hasn’t had the “pleasure,” it’s basically the same deal as Fatal Attraction, only with an S&M twist and a cold-blooded gal who has no ability to love instead of a pathetic one who loves too much. Once again, audiences encountered a high-powered professional woman (in this case, a best-selling author) who is a sexual predator and sick as all get-out. Sharon Stone deservedly became an overnight sensation on the strength of her performance as Catherine Tramell, the ice-pick-wielding loony/white-hot fuck machine who inspired a thousand beaver jokes, thanks to the infamous and oft-parodied scene where director Paul Verhoeven invites the audience to rubberneck his leading lady’s privates. The actress had been knocking around Hollywood for many years, getting regular work without getting anywhere in particular, until she landed the role that would vault her into the bigtime.

As good as she was, her casting probably represented the last resort of an increasingly desperate production team. Kim Basinger, Michelle Pfeiffer, Julia Roberts, Demi Moore, Meg Ryan, Virginia Madsen, Lena Olin, Greta Scacchi and Emma Thompson all said no — whether their reluctance had more to do with the copious amount of female nudity the job required than the quality of the script and the nature of the character remains to be seen. In any event, the film became the subject of much protest as the result the character’s sexual orientation — which could be more accurately described as pansexual than bi. The film’s detractors claimed that the filmmakers not only viewed bisexuality as a perversion, but went so far as to equate it with sociopathic behavior. Gay and lesbian activists picketed while the film was shooting on location in San Francisco, requiring the deployment of police riot squads, and the controversy had already gotten a great deal of coverage before the film had even opened.

Having seen the film again recently, I do not find that it is offensive to gay people. I believe that it is offensive to all people. Not surprisingly, given the participation of Mr. Douglas, it is particularly insulting to women, particularly of the white-collar working variety. In addition to its insistence that there is something inherently evil about female sexuality, the film presents us with a secondary female character, a psychologist played by Jeanne Tripplehorn, who is not only completely incompetent in a professional capacity but a total doormat in her off hours. Her irrational attachment to Douglas’ character, who treats her like shit even when he’s making love to her (if that’s what it can be called, given the rough and graphic nature of their sex scenes), not only overrules her judgment and professional code of ethics, but leads to her eventual demise. And, yeah, turns out she also swings both ways. Dude…it’s hot!

If these three films provide us with a virtual who’s who of Hollywood actresses (at least in terms of who had the good sense not to bite), they don’t represent the only contribution Mr. Douglas has made to advancement of women’s rights during his long tenure as a leading man. As far as I know, Demi Moore was the first choice for the lead in Disclosure, which would serve to reason given her status as the top female box office attraction of the early '90s, after Julia Roberts. As such, there is no list of conscientious objectors to report, which might create the false impression that the film’s content is of a less incendiary nature than the other films discussed here. Actually, it’s probably the most corrosive of the bunch. Barry Levinson’s adaptation of the Michael Crichton novel plays to the popular male paranoia that not only are women trying to take away their jobs, they want to rip off their balls in the process. Once again, Douglas plays a basically decent guy who is passed over for a promotion in favor of the castrating bitch essayed by Ms. Moore, who becomes his new boss. Prowling through the corridors of power in stiletto heels and leaving a tiny trail of stab wounds in her wake, this dragon lady has no sooner started lashing the whip than she initiates an aggressive campaign to get into Mr. Douglas’ pants…much to his discomfort and embarrassment. It’s an exercise in role reversal that actually serves to trivialize the issue of workplace sexual harassment rather than shed any new light on the subject. The scene in which Ms. Moore throws Douglas up against a desk and starts shoving his cock in her mouth above his protests would be ludicrously funny in a high-camp way if it didn’t leave such a foul aftertaste (no pun intended).

The tenor of this piece might suggest that I nurse a deep and abiding hatred for Michael Douglas — as both an actor and as a member of the human race. This is not the case — I have nothing against the guy. He has made some highly enjoyable films — Romancing the Stone and The War of the Roses always have been particular favorites of mine — and his turn as a rumpled professor experiencing a midlife crisis in Curtis Hanson’s Wonder Boys probably represents his best acting work to date (although his performance as greed incarnate in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street still commands a devoted following). I’m not really even trying to suggest that Michael Douglas actually is sexist. Putting aside the content of these films, there really isn’t anything to indicate that, as a private citizen, the man has a lack of respect for women and isn’t sympathetic to the issues that affect them. In his defense, it should be noted that he also produced The China Syndrome, which showed a strong, sympathetic female protagonist who refuses to accept the limitations imposed upon her by the powers-that-be, and proves her mettle and her integrity as a journalist.

That said, there’s no denying the fact that Michael Douglas has been involved with some of the most blatant exercises in anti-woman propaganda that the modern cinema has produced. I’m not one of those watchdogs who goes into a tizzy over any perceived instance of political incorrectness — frankly, I think most people are waaaay oversensitive about that kind of thing — but when you look at the kinds of films Michael Douglas has done, you’ve gotta wonder what’s going on in his head (beyond “Damn, I’m married to Catherine Zeta-Jones!”). If he had made just one of these films, I probably wouldn’t think much of it, but the fact is, he was involved with all four of them — and you’d be hard-pressed to find any four films made in the last 30 years which provoked more outrage on the part of feminist advocates. Whether this particular feature of Mr. Douglas’s career is the result of bad judgment or simply bad taste is open to debate, but in any event, it does seem to indicate a certain level of insensitivity (or at least lack of consideration) on his part. He seems to have been on his best behavior for the past decade or so…maybe Catherine managed to get some veto power to go along with the infidelity clause.

Tweet

Labels: B. Levinson, Bancroft, Barbara Hershey, Burstyn, Debra Winger, Demi, Dunaway, Emma Thompson, Geraldine Page, Glenn Close, J. Fonda, Julia Roberts, Kael, Lansbury, Pfeiffer, Sharon Stone

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, June 18, 2006

Terrorist by John Updike

As I promised back in June when I wrote my post about Philip Roth and John Updike, I've finally written a review of Updike's Terrorist once I finished the novel. As with most Updikes, there are multiple pleasures to be found in Terrorist and it certainly works better than some of his other ventures into uncharted (for him) territory, but as a whole it doesn't quite hold together. When I took a novel writing class in college, the professor's religion of choice was the idea that to sell a successful novel, you needed a solitary viewpoint to hold the reader. I didn't agree with him then and I don't agree with him now, but I can see his point to some extent in Terrorist.

The story's main focus is on 18-year-old Ahmad Ashmawy Mulloy, a graduating New Jersey high school student and product of an absent Egyptian father and a troubled Irish-American mother, who has embraced radical Islam and becomes part of a plot to set off explosives in New York's Holland Tunnel. Ahmad's character certainly couldn't be further from the ethnic and religious backgrounds Updike knows best, but the master novelist gives it the old college try and hits more than he misses.

What mucks up the story in Terrorist are Updike's occasional diversions into other lives. The sections dealing with Ahmad's concerned high school counselor Jack Levy do serve a purpose (and his affair with Ahmad's mother Teresa does provide the requisite adulterous sex that no Updike novel can live without), but sections that deal solely with Levy's wife and especially with the Homeland Security secretary (obviously a parody of Tom Ridge) and his secretary just slow down the story, despite their eventual integral nature to the plot, though I'd argue that Updike would have produced more suspense without those scenes.

On top of that, the novel's climax, which does produce momentum unusual for an Updike novel, has some very questionable developments that I'll avoid going into to avoid spoiling it for those who haven't read the book yet. As always, Updike provides some beautiful prose and many insights into religions of all kinds and life in modern America, but overall I think Terrorist fails more than it succeeds, though kudos to Updike for continuing to explore new territory well into his 70s.

Tweet

Labels: Books, Fiction, Roth, Updike

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, June 12, 2006

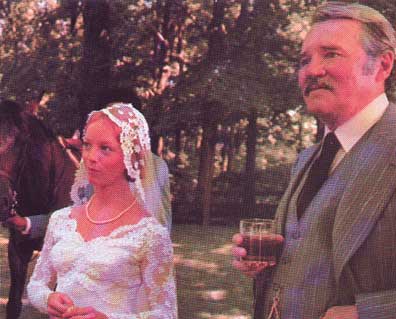

"Life is an excruciating experience — and love is worse"

By Edward Copeland

When I first accepted an invitation to Robert Altman's A Wedding, I was in the thrall of Nashville and open to loving this work, even though I was watching a faded, cropped VHS version and I knew that the critical consensus was that it was a misfire, but I fell in love with its loopy energy and its ensemble cast that doubled the number of characters in my beloved Nashville anyway. With the recent release of a DVD version, I thought it was high time to go back to A Wedding to see what I thought after many years. I still like the movie, but I think I went overboard with my praise for it at the time, though it is great to see it widescreen the way God intended.

The problem I'd always had with the movie seemed even more apparent upon re-visiting. Unlike Altman's other ensemble masterpieces like Nashville and Short Cuts, A Wedding comes up far short in the character department, with too many caricatures and, yes, too many characters for a viewer to really latch on to.

To be sure, there are good performances — Ruth Nelson as a socialist aunt, Pat McCormack as a lovestruck puppy dog of a husband, John Cromwell — better known as a director and as the father of James Cromwell — as the befuddled bishop. Then there is the luminous Lillian Gish, who manages to upstage most everyone, even though after about 20 minutes, her part consists of lying in a bed dead.

In a short documentary on the DVD, Altman admits that the whole production of the film came from a joke. A reporter asked him what he planned to do next and he jokingly said that he was just going to film someone's wedding, since that was becoming a more common thing to do at the time. As he reflected on it, he decided that would be a good idea — since he'd never gone to a wedding where something didn't go wrong.

I'm sure there is a great movie to be made from the concept of a wedding, but rewatching Altman's take, the one thing it seems to really lack is direction or point of view. It's purely a comedy — and there are some spectacular comic highlights — but for the life of me, I don't see what Altman was aiming for here.

The closest I could come up with is the idea that no one and nothing is ever what it appears to be, but at some point, particularly with the "tragic" twist toward the end, it just seems like changeups for the sake of changeups. Even though the return trip to A Wedding was a disappointment for me, I'd still take it over any of Altman's other misfires such as Ready to Wear or Dr. T. and the Women any day, if only to spend time with Howard Duff's boozy, unflappable family physician once again.

By the way, if you were wondering where I took the quote for the title of the post, that to me was one of the most memorable lines from the movie, delivered by the head-over-heels McCormack to Carol Burnett's mother of the bride.

Tweet

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, June 08, 2006

Remembering Moonlighting

By Edward Copeland

March 3, 1985, Moonlighting hit the airwaves with its two-hour pilot. I didn't see it immediately — I'm not sure when I caught on to it, but it soon became one of my favorite TV shows of the time — perhaps all time — until off-camera shenanigans and production problems helped march the show to its own self-destruction.

Just recently, I revisited Seasons 1-3 of Moonlighting and rediscovered its charms and watched the signs as the show spun out of control. To be honest, there's not much past Season 3 worth taking a look at. I also remembered the frustration that came week after week after with reruns because they couldn't pull a new episode together. Imagine if the show premiered now, on HBO perhaps, and a few weeks would seem like nothing compared to the interminable delays HBO forces on fans of its programs. Moonlighting also would have been able to get away with shorter seasons without anyone blinking an eye.

It hardly would have mattered because rewatching Season 3, with the great dramatic arc of the Dave-Maddie-Sam triangle, and you see that they really wrote themselves into a corner. The problem wasn't that everyone was impatient about Maddie and Dave getting together, it's that once they did, there wasn't much left to do. Those series of episodes were priceless and few television moments have been as sad as a rain-soaked David showing up at Maddie's door with flowers at 4 in the morning only to have Mark Harmon open the door. They also were smart by making Harmon's character of Sam such a nice guy that it didn't fall into the typical triangle where there was a bad guy. In fact, really Dave is the point of the triangle that's lacking, no matter how much viewers loved him. I take that back — really it was Maddie that was the problem. Perhaps Sam and Dave should have been the couple — they seemed more compatible.

Season 3 is priceless. Aside from the triangle episodes, it offered gems like "Big Man on Mulberry Street," with its six-minute dance scene directed by Stanley Donen, and of course what is perhaps the greatest of all Moonlighting episodes, "Atomic Shakespeare," with their take on the Bards Taming of the Shrew. It's not that Moonlighting wasn't able to mix drama with its silliness to great success, as when Maddie discovered her father had been unfaithful or in the aforementioned "Big Man on Mulberry Street" when a good friend of David's dies and leads to the revelation that he was once married to his sister. However, once the dramatic element was about Dave and Maddie and Sam, there really was no going back. They tried — somewhat successfully with the detective story that ran throughout the triangle episodes and ended in one of those crazy chases, but at the same time, it seemed out of place with the main storyline. They tried again in the season's final episode where they pushed the Dave-Maddie relationship to the background of a case, but something had been irretrievably lost.

Of course, the problems on the set didn't help with Cybill Shepherd's unexpected pregnancy, Bruce Willis' broken collarbone and whatnot. Perhaps Moonlighting was too bright a star in the firmament of great TV shows not to burn out quickly. What happened in the seasons to follow, while not without its moments, was a televised trainwreck as they fumbled with what to do, having Maddie get pregnant and run away, David mistakenly jailed and poor sidekicks Agnes Dipesto and Herbert Viola (Allyce Beasley and Curtis Armstrong) forced to pick up the slack. While they were great, they couldn't handle the load alone as faithful viewers were growing more and more annoyed by the directionless nature of the show and the frequent absences of the leads. Then, there was perhaps the most bizarre episode ever, the 5th season opener "A Womb with a View," where they transformed a clip show into a musical miscarriage. Yes, the wait for Dave and Maddie to get together wasn't the problem (hell, it was only 38 episodes spread out over a little more than two years), they should have never put them together in the first place, letting the passions go on unsatisfied. I'll always treasure those first three seasons (a mere 39 episodes) as something special and try to pretend that the series ended with Dave and Maddie rolling down the hill in their car as they broke their non-sex pact one last time.

As for the DVD extras, there are some nice commentary tracks, including ones where Cybill Shepherd does her best Rod Steiger lunatic impression, and some nice documentaries. One thing I learned that I never realized while watching the show: how many scenes were filmed with doubles, since Cybill worked better in the mornings and Bruce worked better in the afternoons. Hell, for much of their climactic lovemaking, they both weren't there at the same time. Somehow, that seems like an apt metaphor for what happened to the show in general.

Tweet

Labels: Cybill Shepherd, Donen, HBO, Shakespeare, Television, Willis

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

Give my regards to Broadway

By Josh R

Now that the film awards-giving season is well behind us, and the Emmy nominations won’t be unveiled until July, the attention of awards-watchers like myself turns to the goings-on in the world of Broadway theater. I’m aware that people such as Edward and myself are members of a diminishing breed that actually pay attention to The American Theater Wing’s annual Tony Awards presentation honoring excellence on Broadway — though televised by CBS, the show’s ratings usually fall somewhere between a first-run episode of the least-watched Law & Order spin-off (whichever one that is) and a rerun of Walker, Texas Ranger airing on cable. This is understandable given that very few members of the television audience have actually seen or even heard of the shows and performers in contention. As opposed to films, which are available for viewing just about anywhere, live theater is a site-specific entertainment; either you see it in New York, or you wait for the touring production to make its way to a theater near you — usually sans members of the original Broadway cast.

While all of the media coverage surrounding this year’s Tony Awards seems to center on the non-nomination of Julia Roberts, whose Broadway debut in Three Days of Rain landed with a resounding thud at the Jacobs Theater to the gleefully misanthropic accompaniment of widespread critical guffawing (Clive Barnes of The New York Post likened her stage presence to that of a lamppost), the awards themselves will showcase a variety of interesting and worthwhile productions. This year, I’ve seen eight of the nominated shows, and a ninth off-B’way offering that will be headed to the Great White Way this fall and will doubtless figure prominently in next year’s Tony Awards.

The most celebrated of these is The History Boys, an import from Britain’s National Theater. Written by Alan Bennett, best known to American audiences for his play The Madness of King George (and its subsequent Oscar-nominated film adaptation starring Nigel Hawthorne), the play has received the kind of glowing notices that usually guarantee a production automatic commercial success and a long life beyond Broadway. Indeed, The History Boys has sold out its entire limited New York run, and a film version already has been made by Nicholas Hytner (who also directed this production), which may be released as early as this fall. It’s regarded as the prohibitive frontrunner in the best play category, and deservedly so.

As with any work of theater which takes on complicated issues, the plot is difficult to summarize. Basically, the story centers on a group of British schoolboys being prepared to take their college entrance exams by two teachers representing radically different approaches to education. The show has drawn some comparison to Dead Poets Society, although beyond their scholastic settings, I don’t think the two have very much in common (it’s a bit like comparing Network to Murphy Brown because they both take place in the world of televised news). History Boys uses this basic premise of a teacher inspiring his pupils as a jumping off place to tackle some thorny and provocative issues about the modern cultural approach to learning, and the way that institutional education can be damaging to those who seek to gain from it. The two teachers — played by Richard Griffiths (known to fans of the Harry Potter series as the title character’s portly muggle uncle) and Stephen Campbell Moore (Bright

Young Things) — personify two radically different approaches to education. One represents the idea of learning for its own sake, the other views education as a commodity that can be parlayed into status, something to be used and exploited rather than to be enlightened by. The school's headmaster favors the latter approach since it produces "quantifiable" results — high test scores and Oxford scholarships. He prioritizes the well-being of the institution, and the prestige its pupils can bring to it, above the best interests of the people the institution exists to benefit — many critics have observed how this aspect of the play is really a metaphor for the self-serving politics of Thatcherite England (it's no accident that the play is set during Thatcher's tenure as prime minister). The "History Boys" are emerging from their education with a wealth of knowledge, but without any sense of how to apply it toward some meaningful purpose — all Moore's character has taught them how to do is to make flashy, subversive intellectual arguments that make them desirable to top universities. The scene where his character encourages his students to rationalize The Holocaust is chilling — it doesn't matter whether the students believe what they're saying or not, since (to Moore's way of thinking) perception is valued above truth.

Young Things) — personify two radically different approaches to education. One represents the idea of learning for its own sake, the other views education as a commodity that can be parlayed into status, something to be used and exploited rather than to be enlightened by. The school's headmaster favors the latter approach since it produces "quantifiable" results — high test scores and Oxford scholarships. He prioritizes the well-being of the institution, and the prestige its pupils can bring to it, above the best interests of the people the institution exists to benefit — many critics have observed how this aspect of the play is really a metaphor for the self-serving politics of Thatcherite England (it's no accident that the play is set during Thatcher's tenure as prime minister). The "History Boys" are emerging from their education with a wealth of knowledge, but without any sense of how to apply it toward some meaningful purpose — all Moore's character has taught them how to do is to make flashy, subversive intellectual arguments that make them desirable to top universities. The scene where his character encourages his students to rationalize The Holocaust is chilling — it doesn't matter whether the students believe what they're saying or not, since (to Moore's way of thinking) perception is valued above truth.The production has transferred from the 2005 National Theatre incarnation with its original cast intact. Griffiths, a marvelous character actor who handles both the play’s comic and tragic elements with equal aplomb, is likely to win best actor for his performance as the eccentric Hector — a maverick teacher in the Jean Brodie mold who isn’t above making inept advances toward his students when he’s not having them act out scenes from Now, Voyager and Brief Encounter. Frances de la Tour also is considered a strong contender in the featured category for her delightful deadpanning as Mrs. Lintott, who serves as the play’s wry, wary voice of reason, while young Samuel Barnett is nominated in the featured actor category as Posner, a desperately insecure student nursing a painful crush on his classmate, Dakin, played by Dominic Cooper. All five of the actors (Griffiths, Campbell Moore, de la Tour, Barnett, Cooper) were nominated for Drama Desk Awards — the Tony-nominated troika all won in their respective categories.

Just as it was beginning to look as if no new play could generate as much heat as the Bennett offering, an unlikely new entry arrived on the scene to rival The History Boys for critical enthusiasm. Irish playwright Martin McDonagh first achieved widespread recognition on Broadway for his 1998 critical and commercial hit The Beauty Queen of Leenane, a sort of Celtic variation on Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? with a mother and daughter wreaking havoc on each other’s lives in epic Grand Guignol fashion. Known for his penchant for shock value — startlingly violent imagery delivered with a twist of black humor — the playwright has been prolific in the years since, garnering four nominations in the best play category and winning an Oscar this past March for his short film, Six Shooter. His latest, The Lieutenant of Inishmore, has settled in for what appears to be a long run at the Lyceum Theater after an acclaimed engagement at off-Broadway’s Atlantic Theater Company.

Beauty Queen of Leenane is the only other work of McDonagh’s I’ve seen, and even though I had reservations about the play as a whole, I couldn’t help being impressed by the author’s undeniable talent and nerve; The Lieutenant of Inishmore, which is doubtless one of the outrageous spectacles

ever to be presented on a Broadway stage, is a much more ambitious and impressive piece of work, and infinitely more satisfying. A sociopathic IRA gunman, played to the hilt by the charismatic Irish actor David Wilmot, leaves his cherished pet cat, Wee Thomas, in the care of his belligerent father (Peter Gerety), who is too fearful of his son’s wrath to decline the responsibility. When Wee Thomas meets his untimely demise, ostensibly at the hands of a dull-witted teenager on a bicycle (Tony-nominated Domhnall Gleeson), it sets off a bloody chain of events that is both appallingly funny and frighteningly absurd. A brickbat pitched squarely in the direction of the reigning powers-that-be and their disciples, McDonagh’s deliciously twisted take on the senselessness of terrorism exposes (and holds up for ridicule) the sheer lunacy of warfare fought on an ideological basis. The playwright has great fun at expense of his characters’ convoluted politics — they represent various splinter groups (and even splinter groups of splinter groups) and have become so warped by their own crazed rhetoric and wayward sense of moral imperative that they’ve forgotten exactly what the ideological basis of their positions are. No one seems to be able to pin down the specifics of their various agendas — even for the most fervent advocates of a particular cause, the rationale is murky at best. Ultimately, McDonagh suggests, it all just amounts to empty posturing.

ever to be presented on a Broadway stage, is a much more ambitious and impressive piece of work, and infinitely more satisfying. A sociopathic IRA gunman, played to the hilt by the charismatic Irish actor David Wilmot, leaves his cherished pet cat, Wee Thomas, in the care of his belligerent father (Peter Gerety), who is too fearful of his son’s wrath to decline the responsibility. When Wee Thomas meets his untimely demise, ostensibly at the hands of a dull-witted teenager on a bicycle (Tony-nominated Domhnall Gleeson), it sets off a bloody chain of events that is both appallingly funny and frighteningly absurd. A brickbat pitched squarely in the direction of the reigning powers-that-be and their disciples, McDonagh’s deliciously twisted take on the senselessness of terrorism exposes (and holds up for ridicule) the sheer lunacy of warfare fought on an ideological basis. The playwright has great fun at expense of his characters’ convoluted politics — they represent various splinter groups (and even splinter groups of splinter groups) and have become so warped by their own crazed rhetoric and wayward sense of moral imperative that they’ve forgotten exactly what the ideological basis of their positions are. No one seems to be able to pin down the specifics of their various agendas — even for the most fervent advocates of a particular cause, the rationale is murky at best. Ultimately, McDonagh suggests, it all just amounts to empty posturing.The gore in Inishmore is amazingly graphic by Broadway standards, although relatively tame by Hollywood's. McDonagh has cited Quentin Tarantino as one of his influences, and the show’s frequent outbreaks of violence, abounding with gleefully gory imagery executed in a take-no-prisoners fashion, echo the highly stylized bouts of bloodletting on display in the Kill Bill films. Midway through the second act, the carnage starts to amass — the set is strewn with corpses in various states of dismemberment and the walls and floors have been liberally doused with blood. The audience response is one of shock, but there's also a fair amount of giggling — the visual is just so outrageous you can't help but laugh. It’s a brilliantly constructed play given an amazingly kinetic production by Wilson Milam, and I suspect that even the squeamish playgoers will be surprised to find themselves laughing along with the catalog of horrors on display.

The two other dramatic offerings I’ve seen this year are not quite as successful, although both qualify as worthy endeavors. Lincoln Center Theater serves up a revival of the 1935 social polemic Awake and Sing!, the most celebrated work of playwright Clifford Odets. If you’ve never heard of it, there’s a reason: although regarded as a seminal work, it doesn’t fully measure up to its exalted reputation. Although given an intelligent production by director Bartlett Sher, and expertly performed by a star-studded cast featuring Ben Gazzara, Mark Ruffalo, Zoe Wanamaker and Lauren Ambrose, there’s very little that talent could have done to disguise both the play’s age and its obvious limitations. Written in tough-talking period slang so florid it would make James Cagney blush (clearly these characters hail from the same environs as The Dead End Kids), the play wears its social indignation and political agenda-pushing a little too prominently on its careworn sleeve. The characters, members of a downtrodden Jewish family living in the squalid tenement slums of lower Manhattan, exist as an illustration of the manner in which the proletariat is oppressed by the commercial classes. By the time the idealistic young hero is exhorting his fellow men to till the earth, the combination of hokiness and preachiness has become difficult to accept with a straight face. That said, the production is very well-acted, particularly by Ruffalo as a hard-bitten realist who actually manages to make his slang-heavy dialogue plausible, and by Wanamaker as the matriarch who has been made cynical and grasping by years of struggle and compromise.

David Lindsay-Abaire’s Rabbit Hole has the rather dubious distinction of being the only work by an American playwright to be nominated in the best play category. The author became something of a critical darling for his unconventional, absurdist off-Broadway comedies Fuddy Meers and Kimberly Akimbo — for his Broadway debut, he apparently decided to make a 180 degree turn into the relative safety of poker-faced realism, and the result feels like a very calculated effort at mainstreaming (notice I didn’t say selling out, because the play is obviously a work of genuine feeling rather than a cynical concession to popular taste). To be fair, Lindsay-Abaire’s talent as a writer is clearly in evidence, which only partially serves to compensate for the rather uninspired subject matter he’s chosen to explore. The play is about two parents coping with the death of a young child and learning how to heal — if that sounds a bit Hallmark Hall of Fame, that’s sort of how it plays. The consummate skill of Cynthia Nixon, who plays the role of the grieving mother, lends emotional credibility to a play that is otherwise bogged down in what often borders on maudlin, movie-of-the-week style dramaturgy, while Tyne Daly contributes a welcome element of humor in a supporting role. Both women are nominated for Tony Awards — Nixon’s prospects for winning lead actress look very good in what is considered a rather weak category. Since Mr. Copeland and I are both card-carrying members of the Cynthia Nixon fan club — my admiration for the actress dating back to her stage work in the mid-'90s (particularly Phyllis Nagy’s avant-garde production of The Scarlet Letter at CSC in 1995), Edward having been in thrall to her charms ever since Sex & The City — this will provide us with a mutual rooting interest.

David Lindsay-Abaire’s Rabbit Hole has the rather dubious distinction of being the only work by an American playwright to be nominated in the best play category. The author became something of a critical darling for his unconventional, absurdist off-Broadway comedies Fuddy Meers and Kimberly Akimbo — for his Broadway debut, he apparently decided to make a 180 degree turn into the relative safety of poker-faced realism, and the result feels like a very calculated effort at mainstreaming (notice I didn’t say selling out, because the play is obviously a work of genuine feeling rather than a cynical concession to popular taste). To be fair, Lindsay-Abaire’s talent as a writer is clearly in evidence, which only partially serves to compensate for the rather uninspired subject matter he’s chosen to explore. The play is about two parents coping with the death of a young child and learning how to heal — if that sounds a bit Hallmark Hall of Fame, that’s sort of how it plays. The consummate skill of Cynthia Nixon, who plays the role of the grieving mother, lends emotional credibility to a play that is otherwise bogged down in what often borders on maudlin, movie-of-the-week style dramaturgy, while Tyne Daly contributes a welcome element of humor in a supporting role. Both women are nominated for Tony Awards — Nixon’s prospects for winning lead actress look very good in what is considered a rather weak category. Since Mr. Copeland and I are both card-carrying members of the Cynthia Nixon fan club — my admiration for the actress dating back to her stage work in the mid-'90s (particularly Phyllis Nagy’s avant-garde production of The Scarlet Letter at CSC in 1995), Edward having been in thrall to her charms ever since Sex & The City — this will provide us with a mutual rooting interest.

It’s become a favorite pastime of the critics to lament the state of the American musical. Such was the case a few weeks ago, when Ben Brantley wrote what amounted to an obituary for the Broadway tuner in The Sunday Times, summarily dismissing virtually every new show that opened during the 2005-2006 season while measuring them unfavorably against the two hit revivals. The response to the piece within the Broadway community was one of righteous indignation — at the Drama Desk Awards, one of the producers of The Drowsy Chaperone blasted the critic for his comments in his acceptance speech (telling Brantley he “needed to get out more”), to roars of approval from those in attendance — this despite the fact that Chaperone was just about the only new show Brantley didn’t run through the shredder.

While I appreciate many of Brantley’s points, and would certainly make no attempt to defend any season which inflicted upon the populace the likes of The Wedding Singer and Elton John’s Lestat (which I have not seen, but have heard enough about to steer well clear of), I think it’s a bit premature to sound the death knell for the Broadway musical — if anything, we’ve probably seen an upswing in recent years. Coming off the doldrums of the '90s, a decade which produced only two truly outstanding new musicals (City of Angels and Rent) wedged in between an assortment of qualified successes, outright turkeys, and innumerable revivals, 21st century Broadway has already given us The Producers, The Full Monty, Hairspray, Avenue Q, and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, plus the slight but enjoyably silly romp that is Monty Python’s Spamalot. While tourism-savvy Broadway still churns out a lamentable number of overproduced theme park rides masquerading as theater, or at the other end of the spectrum, cost-effective Lawrence Welk-style revues cobbled together from recycled Billboard hits of yesteryear, there are more interesting and worthy new shows out there today then there were ten years ago. Which is not to say that the Golden Age of the Broadway Musical isn’t already several decades behind us.

This being the case, it’s the revivals that are greeted with the most enthusiasm by contemporary critics, and the current season features two that have each drawn a great deal of praise.

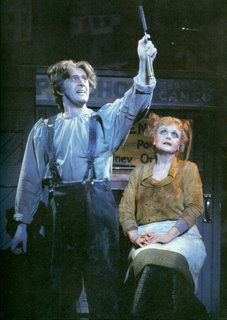

For anyone unfamiliar with Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, I implore you on bended knee to put the American Playhouse filmed version of the stage production — featuring the show’s original star, Angela Lansbury — at the very top of your Netflix queue. If you don’t have Netflix (or something comparable), then take out your credit card credit card and buy the damn thing on amazon.com (or something comparable). And if you don’t have a credit card, steal one. It’s one of the two or three greatest works ever created for the American musical theater, and even you don’t like musicals, you’ll like this one. Either that, or you’ll have forfeited the right to consider yourself a person of taste (sorry, but there are some things I can’t be practical about, and Sweeney Todd is one of them).

I can’t do full justice to the intricately devised plot of the show without testing the patience of anyone reading this, but I’ll try to sum it up as best I can: in a nutshell, the show is based on a penny dreadful — the 18th century equivalent of the kind of grisly tales kids swap around campfires — about a demonic barber in the slums of Victorian England who kills his clients and sends their bodies to his sweetheart, the owner of an establishment which makes and sells meat pies. Which implies exactly what you think it does. Composer-lyricist Stephen Sondheim and librettist Hugh Wheeler tweaked the formula by fashioning their adaptation of the gory legend as a meditation on social inequity. It’s a classic revenge fantasy in which the haves, the people who have power and abuse it, get the comeuppance they deserve for shitting all over the have-nots. These tyrants, men of wealth and consequence who take gross liberties with the privileges birth and status have given them, are served to the victims of their oppression on a plate. Literally. In this version of events, Sweeney Todd, a poor barber, is framed for a crime he didn’t commit by a corrupt judge who covets his beautiful young wife. Sweeney is conveniently dispatched to a penal colony in Australia — he returns under an assumed identity many years later to be told of how his wife suffered at the hands of his nemesis, and subsequently committed suicide. This barber doesn’t kill people merely because he gets a kick out of it — unhinged by bitterness and grief, he seeks to exact revenge on those who ruined his life. When he meets up with the cheerfully amoral Mrs. Lovett, a wily opportunist with the good sense to utilize his bloodlust to maximize her profit margins, the diabolically enterprising team successfully convert half the population of London into unwitting cannibals.

Hal Prince’s legendary 1979 staging was an elaborate spectacle done in period style with Victorian sets and costumes — most subsequent productions, though perhaps more modest in scale, haven’t made a radical departure from this template. John Doyle, who helmed the current Broadway revival, has opted for an entirely different approach — and to call it a radical departure would be an understatement. It’s a boldly minimalist staging which forgoes any attempt at realism — for starters, the actors double as the orchestra (the effect really has to be seen to be appreciated, but it involves some logistically complex stagecraft and dextrous multi-tasking by the cast). The production style is non-period-specific, and decidedly avant-garde; for those unfamiliar with the story, certain things may be a bit confusing, since this is not a literal-minded representation of the action. For example, each murder, rather than being acted out, is indicated when the actors pour quantities of blood from one bucket into another. The cast of ten actors double and triple in various roles without much in the way of costume changes, and often in ways the defy the specifications of gender or age. It’s a very conceptual approach, and one

Hal Prince’s legendary 1979 staging was an elaborate spectacle done in period style with Victorian sets and costumes — most subsequent productions, though perhaps more modest in scale, haven’t made a radical departure from this template. John Doyle, who helmed the current Broadway revival, has opted for an entirely different approach — and to call it a radical departure would be an understatement. It’s a boldly minimalist staging which forgoes any attempt at realism — for starters, the actors double as the orchestra (the effect really has to be seen to be appreciated, but it involves some logistically complex stagecraft and dextrous multi-tasking by the cast). The production style is non-period-specific, and decidedly avant-garde; for those unfamiliar with the story, certain things may be a bit confusing, since this is not a literal-minded representation of the action. For example, each murder, rather than being acted out, is indicated when the actors pour quantities of blood from one bucket into another. The cast of ten actors double and triple in various roles without much in the way of costume changes, and often in ways the defy the specifications of gender or age. It’s a very conceptual approach, and one which produces very satisfying effects, although the lushness of Sondheim’s complex and melodic score is somewhat lost without the benefit of a full orchestra. If there’s anything missing from this production, it’s the element of gleeful black humor that Sondheim, Wheeler and Prince used in the original to balance out the bleak nature of the subject matter. The original Sweeney was blissfully funny, due in no small part to the performance of Angela Lansbury as the delightfully grotesque Mrs. Lovett. While her broadly comic creation was informed by the classic traditions of the English music hall (which involves plenty of mugging and exaggerated mannerism), the Mrs. Lovett of Patti LuPone is decidedly subdued, more hard-bitten pragmatist than Grand Guignol cut-up. What this does, in effect, is to rob the show of the required element of comic relief, a necessary function the character must serve in order to keep things from getting too depressing (which is exactly why Sondheim and Wheeler conceived the character in a comic vein). Still, the actress is widely considered the favorite to win her second Tony for the performance — her first having come for playing the title role in the 1980 Broadway premiere of Evita.

which produces very satisfying effects, although the lushness of Sondheim’s complex and melodic score is somewhat lost without the benefit of a full orchestra. If there’s anything missing from this production, it’s the element of gleeful black humor that Sondheim, Wheeler and Prince used in the original to balance out the bleak nature of the subject matter. The original Sweeney was blissfully funny, due in no small part to the performance of Angela Lansbury as the delightfully grotesque Mrs. Lovett. While her broadly comic creation was informed by the classic traditions of the English music hall (which involves plenty of mugging and exaggerated mannerism), the Mrs. Lovett of Patti LuPone is decidedly subdued, more hard-bitten pragmatist than Grand Guignol cut-up. What this does, in effect, is to rob the show of the required element of comic relief, a necessary function the character must serve in order to keep things from getting too depressing (which is exactly why Sondheim and Wheeler conceived the character in a comic vein). Still, the actress is widely considered the favorite to win her second Tony for the performance — her first having come for playing the title role in the 1980 Broadway premiere of Evita.

Whereas this production of Sweeney is defiantly nontraditional, the season’s other musical revival of note is decidedly square…which makes it no less of a triumph. The Pajama Game is the kind of kitschy, cornball entertainment that probably seemed clever and witty back in 1955 — by modern standards, it’s about as sophisticated in its attitudes as Pillow Talk, the squeaky-clean sex comedy of 1959 starring Rock Hudson and Doris Day (it’s no accident that Day top-lined the 1957 film version of The Pajama Game). It’s a cute boy-meets-girl tale set in a pajama factory — since the course of true love never did run smooth, she’s a union agitator, he’s management. A proposed strike presents an obstacle to their romance — boy loses girl, boy gets girl back.

It’s the kind of sappy, precious material that really has no business working in a contemporary context — but never underestimate what a great chef can do with day-old bread. Nearly everything about the production confounds expectation; credit director-choreographer Kathleen Marshall (sister of filmmaker Rob) for sprucing up an old chestnut with style and verve. Her crackerjack production succeeds in making The Pajama Game seem less trite and coy than it actually is, while still managing to stay absolutely true to the spirit of source material. This is due in no small part to the presence of Harry Connick Jr., making a remarkably polished and assured Broadway debut as the show’s romantic lead. In additional to his sublime vocals, which capture the full vintage flavor of the Adler and Ross score, he creates a wonderful chemistry with golden-voiced leading lady Kelli O’Hara, who has an astute, knowing quality which gives her wholesome girl-next-door character a nice bit of an edge. The interplay between the two recalls classic scream teams like Hepburn & Tracy and Bogart & Bacall — it’s smart, sexy, and when they spark, it strikes just the right balance between sophistication and playfulness. The show has a lock on only one Tony (for best choreography), and looks likely to come up short in all the other categories in which it’s nominated. Still, if the production can only take home one award, it’s only right that Marshall’s dance routines should be the beneficiary. Worthy of special mention are her dizzy "Once-a-Year-Day" ballet, a nifty nod to the Fosse style with "Steam Heat", and above all, a dazzlingly staged and executed "Hernardo's Hideway" which weaves Connick's piano-playing skills seamlessly (and quite ingeniously) into the fabric of the dance.

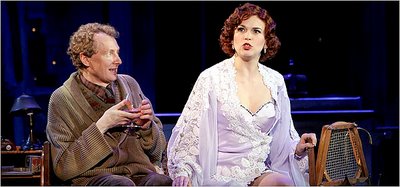

One show that is canny enough to exploit the gap between the heyday of Cole Porter and what often passes for musical theater today has become the heavy favorite to win best musical. Instead of operating on the pretense that the state of contemporary musicals is right as rain, the show emphatically and hilariously insists that the celebrated hit of today doesn’t even stack up to yesterday’s mediocrity. The central character, billed only as Man in Chair, opens by the show by telling us he hates theater (“Well, it’s always so disappointing isn’t it…please, Elton John, must we continue with this charade?”). A middle-age musical theater buff of indeterminate sexuality and multiple neuroses, The Man holds court from his cluttered studio apartment, treating the audience as his guests and extolling the virtues of his favorite 1920s musical. The show is The Drowsy Chaperone, a madcap romp involving a dewy-eyed heroine, her stalwart suitor, a tippling grand dame, a dithery socialite, a supercilious butler, an anxious Broadway producer and a pair of gangsters who crash a wedding and pose as pastry chefs — the kind of frothy, featherweight concoction that was Broadway’s stock-in-trade during the era of Ziegfeld pastiche. The twist is that while Man in Chair plays the album for us, the show comes to life before our very eyes in his apartment (with various characters making their entrances from out of the refrigerator or whatever other ports of entry are available). The narrator doesn’t dematerialize, nor is he magically transported inside the show to become a participant, ala The Purple Rose of Cairo. Instead, he sits on the sidelines, commenting on what we’re seeing, offering amusing bits of trivia about the actors (for example, one earned the moniker The “Oops” Girl for her ability to cause men to suffer accidents, while another was apparently found dead in his Italian villa partially devoured by his own poodles), and occasionally singing along when not apologizing to the audience for parts of the show that are more ludicrous than others (“please do your best to ignore the lyrics and enjoy the melody” he says of a torch song that employs the awkward metaphor of monkey love to describe a relationship gone sour). I’m always slightly skeptical of shows built around a gimmick; but the witty conceit that provides the basis of The Drowsy Chaperone proves disarmingly effective — especially when it allows for riotously funny bits of business as a dance sequence that goes slightly amiss when the record begins to skip, or the moment when The Man inadvertently plays the record from a different show when changing LPs before going off on a bathroom break (what we get is a hilariously racist song from another 1920s show bearing a striking resemblance to The King and I).

As Ben Brantley observes in his review, the show-within-a-show isn't as good as The Man's running commentary, but the flaw is hardly fatal. The music and lyrics, by a novice team, are undistinguished, but the libretto is strong throughout. Bob Martin is wonderful in the lead, while Sutton Foster makes the most of her two show-stopping numbers (one of which features her jumping through hoops, juggling plates, throwing her voice, and doing cartwheels while insisting she doesn’t want to be the center of attention). Beth Leavel, who plays the title role as a martini-soaked grand dame, is the heavy frontrunner in the featured actress category — that said, the performance is way too broad for my taste and the shtick wears thin rather quickly.

Needless to say, of all works of contemporary fiction, Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Color Purple has always been the second most obvious candidate for adaptation into a crowd-pleasing Broadway musical (the first, I’m sure we can all agree, being The Bonfire of the Vanities). Produced for the stage by the all-powerful multimedia conglomerate known as Oprah, who not un-coincidentally played the role of Sofia in Steven Spielberg’s 1985 cinematic version, the show actually works better than one might expect — which is not to say that it was ever a good idea in the first place. This Color Purple seems to draw the bulk of its inspiration from the Spielberg film rather than the source novel; this being the case, it shares many of the movie’s flaws. It was always somewhat disheartening for lovers of the novel to see the mood created by Walker’s spare, gritty prose jettisoned in favor of a heartwarming, candy-colored tearjerker populated by exaggerated stereotypes. The show attempts to replicate the effect, and just as the film did, tries to shoehorn too many narrative threads into an overly condensed format. Still and all, it works on the level of entertainment, and provides two and half hours of pleasant, if ultimately unmemorable, diversion. The standouts from the large cast are Felicia P. Fields as the brash Sofia, Elisabeth Withers-Mendes as the sensual Shug, and the lumnious LaChanze, who navigates Celie's transition from meek acquiescent to independent spirit much more convincingly than Whoopi Goldberg did. Since the combination of brass lungs and power ballads usually carry some weight with voters (as was the case when Idina Menzel’s strenuous vocal pyrotechnics in Wicked helped her to vault past Donna Murphy and Tonya Pinkins two years ago), LaChanze's powerfully sung performance considered a strong contender for the win.

The most interesting and ambitious new musical I’ve seen this past year is Grey Gardens, which played a limited engagement at Playwright’s Horizons in preparation for a Broadway run. I’ll have a lot more to say about the production and the cult documentary film on which it is based when the show opens at the Walter Kerr Theater in the fall. The performance given by the production’s lead actress, Christine Ebersole, may qualify as the best I’ve seen on any stage this year, and would surely be considered a strong contender for a Tony if off-Broadway productions were eligible for consideration. The Tonys are produced by The League of American Theatres and Producers (jointly with the American Theatre Wing). As many critics of the Tony Awards have observed, the Broadway producers are resistant to the inclusion of off-B'way productions; as far as they're concerned, the Tonys exist first and foremost as an opportunity to promote their own product, to the exclusion of all else. That being the case, the nominations don't represent a fair sampling of what the season has to offer; Broadway shows account for only a small percentage of the productions that open each year. In view of these circumstances, one might be justified in viewing the Tony Awards as more of an industry trade show than a merit-based competition. But that’s a discussion for another day….and besides, even if you know the thing is rigged, it doesn’t make it any less fun to watch.

In speaking with friends about shows I've seen, I’ve encountered many cynics who assert that theater is no longer relevant as popular culture (we call these people philistines…just kidding). It doesn’t seem as if many younger actors of my acquaintance even aspire to be stage performers; the perception seems to be that theater is something you do to hone your craft while waiting for the big break to materialize — a launchpad to film and television work. It’s true that, in an age dominated by electronic media, the audience for theater has shrunk considerably. Broadway doesn’t have the same kind of prominence that it once did, when stage-based performers such as Mary Martin or Ethel Merman could attain the status of household names, or a new discovery such as Barbra Streisand or Carol Burnett could become an overnight sensation based on a Broadway success. People of my parents’ generation grew up with an awareness of theater — the original cast recording of My Fair Lady, for example, was one of the best selling albums of its year, and its score was almost universally heard and enjoyed even before the Warner Bros. film adaptation arrived on the scene. It’s hard to imagine something like that happening today, when instances of Broadway productions blossoming into pop culture phenomena are few and far between (the Lloyd Webber shows of the '80s may come the closest). But for those who are willing and able to take the time to look, the pleasures that this art form still affords are undeniable and, I would suggest, vital. Live theater can still take you places that movies and television never could. So if you can make it to New York, for gosh sakes, see a Broadway show — it’ll only cost you an arm and a leg. Which doesn't seem like too much of a sacrfice when you consider what certain characters in The Lieutenant of Inishmore and Sweeney Todd have to part with.

Tweet

Labels: Bacall, Bogart, Cagney, Cole Porter, Cynthia Nixon, Doris Day, Fosse, Julia Roberts, K. Hepburn, Lansbury, Law and Order, Musicals, Rock Hudson, Sondheim, Spielberg, Streisand, Tarantino, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, June 02, 2006

Logan's Run for Film Critics?

By Edward Copeland

Anne Thompson of The Hollywood Reporter has an excellent column about the recent trend of newspapers dumping its seasoned film critics in their futile quest for young readers. (Full disclosure: She refers to me in the column, but I think it sparks an interesting discussion regardless of my name being mentioned).

The Chicago Tribune recently dumped longtime critic Michael Wilmington and The New York Daily News similarly dismissed Jami Bernard. Personally, I don't think it is ALL lust for youth that is leading to these changes, but more economic concerns. Just this week, The Washington Post announced more staff buyouts that included longtime television critic Tom Shales, though he will apparently write on some sort of freelance basis. Newspapers are dying — and the majority of executives at the newspapers seem utterly clueless about what to do. (Just look at how ineptly The New York Times handled its journalism scandals).

The truth is that the bulk of the journalistic elders are borderline Luddites and the Internet has long puzzled them and now it has scared the shit out of them and they don't know what to do. Marketing idiots try to convince them that the answer is to get young readers, but they ignore the history of the medium. Young people, unless they were news junkies, NEVER read newspapers until they got older and with the advent of the Web, they really aren't going to get them now. (Show of hands — how many of you reading this subscribe to an actual paper made out of newsprint — newspaper Web sites don't count.)

The truth is so obvious that it amazes me that there aren't more executives who recognize that the demographic they should be targeting are in their 30s and 40s, those who have settled down and have actual driveways that newspapers can be tossed into.

Instead, the culturally illiterate editors try to impose People magazine-style crap onto their newspapers of record. God help you if you live in the home state or hometown of an American Idol winner — those papers are likely to use any excuse to put that winner on their front page under the spurious assumption that it pumps newsstand sales. Even if that's true, it's a one-day shot at best — do they really believe that those who bought the paper to see the Carrie Underwoods, Taylor Hicks or Ruben Studdards of the world will return the next day to see what the city council did? Some of my journalist friends have reported that some papers are starting to see the light and abandoning the fruitless pursuit of the young, realizing that by doing that, they've alienated their true, older audience.

The downward slide of newspapers has been a long one. First, they made the mistake of trying to ape television, now they do everything to attract people they are never going to get. It's even more infuriating as newsholes shrink and true important local, national and world stories don't make the cut because they feel they better cover Brad and Angelina's babies or make lame attempts to turn The Da Vinci Code into a local story.