Tuesday, September 05, 2006

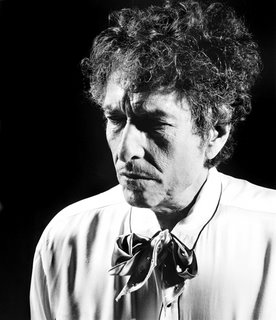

Bob Dylan's Modern Times

BLOGGER'S NOTE: Welcome to a new contributor here, Jeffrey, proprietor of Liverputty, who contributes an assessment of the new album by the great Bob Dylan.

By Jeffrey Hill

Who came up with the idea that Modern Times was the last installment of a trilogy? I somehow doubt it was Dylan. Was it Columbia? Countless reviews have floated that angle as fact. A few others have questioned it. Certainly, there are traces of the previous two albums in Modern Times: an uptempo bluesy tune such as "The Levee's Gonna Break" would, with a working over from producer Daniel Lanois, blend right in next to Time Out of Mind's "Dirt Road Blues"; the old fashioned melodies of Modern Times' "Spirit on the Water" and "Beyond the Horizon" recall the songs from Love and Theft which gave the former that Gay '90s sound.

That this album, like Love and Theft, seems to be a living specimen encompassing the entire American musical heritage does not mean it's part of a trilogy. Suggesting so diminishes broader trends and developments in Dylan's work. For example, traditional music has always played a fundamental role in Dylan's songs, but it was elevated greatly with the two acoustic predecessors to Time Out of Mind: Good As I Been to You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993). With those two albums, Dylan made it known that he had completely absorbed the Western musical canon and would use it with abandon. Dylan once described music as his religion, and he is a religious man. He's not a preacher but a man whose well runs deep and he draws from it often. The thorough use of tradition is a defining part of this current (or past, now, I guess) "trilogy." Does that mean these last five albums make up a concerted pentalogy? If so, one could trace this trend back to the very beginning of his career, making his entire discography as one massive work without end.

Writing on Dylan can be tricky, as you are always tempted to apply specifics to otherwise vague references. Take Joe Levy, for instance, and this description on the new album:

"The Great Mississippi Flood [of 1927], along with the Charlie Chaplin movie from which the album takes its name and the Book of Revelations, form a triangle of tragedy, comedy and prophecy in which Modern Times unfolds."

Dylan's flood references are generic and apply to the idea of a deluge. He'll parrot a delta blues singer, who likely was referring to the Mississippi floods of the '20s and '30s, in one line, but then he's just as likely to turn right around and sing about the flood as if it was from the ancient world. It is essentially all floods.

And how does Joe Levy assume the album title was taken from Chaplin's film? Could it not as easily be a play on the early 20th century feel of the album — something beyond a basic reference to an iconic movie?

And then there's the Book of Revelations. Levy thinks that a flood equals the end of the world. Since Dylan uses flood metaphors throughout his work, he must always be referring to the end, right? So when Dylan alludes to a rebirth after the flood in "The Levees Gonna Break," Levy considers it an "odd promise." The idea that a flood could act as a cleanser or an agent of redemption is something Levy has seemingly not considered, despite the numerous rainbows he must have seen in his years. I believe Levy, like many other Dylan critics, overstates the apocalyptic visions of Dylan — particularly after Under the Red Sky. That's not to say there is nothing apocalyptic in his latest work, but when critics talk about the Bible, they are usually referring to Revelations. As much or more of the Bible's influence on Dylan manifests itself in harsh imagery reminiscent of the Old Testament. In "Ain't Talkin'," a revenge tale, he sings: "If I catch my opponents ever sleeping I'll just slaughter 'em where they lie" The retribution and the sheer gore of the declaration is something biblical. He often refers to his enemies in a biblical way.

Dylan is a sucker for old social structures and codes. He's constantly making allusions to feudalism, warlords, kings, crime bosses and chiefs, and mixing them into a swirl so the listener is never quite sure what time period he's in, though the emotions conveyed are crystal clear. The law of the land in Dylan's work is harsh, and the methods of survival are even harsher:

"Gonna raise me an army, some tough sons of bitches. I'll recruit my army from the orphanages..."

There's little mercy between the struggle of men in Dylan's landscape. This worldview is not confined to Modern Times or his recent work in general, but is apparent through his entire body of songs. But next to that warrior's code, Dylan maintains a coarse directness, sometimes a raunchiness, that's straight from the essence of Charlie Patton or Howlin' Wolf which he blends with an "aw shucks" 19th century etiquette. He's just as liable to ask for a little sugar in his bowl as he is to take his hat off in the presence of a lady. And then there's the cowboy swing which was front and center in Love and Theft and again is present in Modern Times. He even says he's in a cowboy band.

His talent is so great, and his presence so towering, that it is hard to describe this music in a manner that does it justice. The temptation, for me at least, is to rain down a bunch of superlatives on Modern Times, but that is exactly what I've done with his previous albums going back to Oh, Mercy. At some point superlatives are not enough. How does one convey that Dylan is bigger and greater than his contemporaries? That is the struggle that critics face. Dylan is more than just his legacy, though it is almost impossible to separate his current album from the legend, he's still a pioneering force in popular music. He doesn't try something, reject it and move on, like, say John Lennon. Influences on Dylan tend to stay with him so that the singer on Modern Times has waxed into an impenetrably deep figure. The gut can understand him, but the intellect no longer can. Or as Noel Menger cleverly admitted when alluding to the meaning of the album: "I won't begin to tell you what it's about, and can't."

Which is why you just have to hear it.

Tweet