Wednesday, December 07, 2011

Harry Morgan (1915-2011)

Harry Bratsburg made his Broadway debut in the original cast of The Group Theatre production of Clifford Odets' boxing drama Golden Boy on Nov. 4, 1937. His co-stars included Lee J. Cobb, Howard da Silva, Frances Farmer, Jules Garfield (who would later act under the first name of John) and two men who would become better known later as directors: Elia Kazan and Martin Ritt. Of course, Bratsburg would change his name as well. After appearing in a total of eight original Broadway plays through 1941 (all but two Group Theatre productions) with up-and-comers such as Burl Ives, Sidney Lumet (when he started out as an actor), Karl Malden, Sylvia Sidney, Franchot Tone, Shelley Winters and Jane Wyatt, Bratsburg headed West for the start of a lengthy film and television career where he'd become much better known as Harry Morgan. Morgan died Wednesday at 96. Actually, when he made his film debut in 1942's To the Shores of Tripoli, he was credited as Henry Morgan as he was well into the 1950s when he started frequently being cited as Henry (Harry) Morgan because of the comedian Henry Morgan who was popular on radio prior to Harry's career, so his screen credit eventually became just Harry Morgan.

It didn't take long for him to land in a classic film once he left the stage for Hollywood. His sixth film was William A. Wellman's masterful 1943 warning against lynch mobs, The Ox-Bow Incident, where he played Henry Fonda's trail companion. His career kept him busy, not always in classics, but always working. Some of his other notable films:

Morgan's greatest fame came from his roles as a regular on several television series throughout his career, beginning with his role as Pete Porter on the comedy December Bride from 1954-1959, which earned him an Emmy nomination. The role was spun off into its own series Pete & Gladys, which lasted from 1960-1962. The first series that probably garnered Morgan the most recognition was when he took the role of Officer Bill

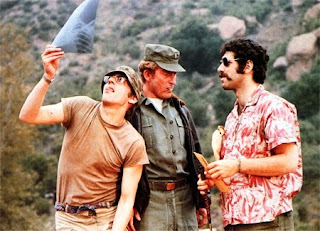

Gannon in Dragnet 1967, Jack Webb's resurrection of his early '50s police drama, that in my mind may well be the funniest show ever to appear on network television. Watching Sgt. Joe Friday square off (pun intended) with spaced-out hippies is hysterical. Morgan reprised his Gannon role in Dan Aykroyd's 1987 spoof movie and merely vocally on an episode of The Simpsons. Morgan also did many guest appearances on other series, TV movies and miniseries, most notably playing another Harry, President Truman in the miniseries Backstairs at the White House. However, the role that will hold his place in TV viewers' hearts is as Col. Sherman T. Potter, the second commanding officer of the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the last eight seasons of M*A*S*H. (We'll not talk about AfterMASH.) The role earned him eight consecutive Emmy nominations as outstanding supporting actor in a comedy series and he won once. He also received a nomination for directing an episode. For me though, I'll always love the performance he gave the year before on M*A*S*H in an Emmy-nominated guest appearance as Maj. Gen. Bartford Hamilton Steele in "The General Flipped at Dawn." Steele appears to be a by-the-book, high-ranking officer but everyone soon realizes, especially Alan Alda's Hawkeye who he tries to court-martial, that he's a raving loon. Morgan's hysterical performance was a thing of beauty. He could be just as funny as Potter but in a completely different way. Potter also frequently touched your heart as he drank a toast when the last of his old comrades died.

Gannon in Dragnet 1967, Jack Webb's resurrection of his early '50s police drama, that in my mind may well be the funniest show ever to appear on network television. Watching Sgt. Joe Friday square off (pun intended) with spaced-out hippies is hysterical. Morgan reprised his Gannon role in Dan Aykroyd's 1987 spoof movie and merely vocally on an episode of The Simpsons. Morgan also did many guest appearances on other series, TV movies and miniseries, most notably playing another Harry, President Truman in the miniseries Backstairs at the White House. However, the role that will hold his place in TV viewers' hearts is as Col. Sherman T. Potter, the second commanding officer of the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the last eight seasons of M*A*S*H. (We'll not talk about AfterMASH.) The role earned him eight consecutive Emmy nominations as outstanding supporting actor in a comedy series and he won once. He also received a nomination for directing an episode. For me though, I'll always love the performance he gave the year before on M*A*S*H in an Emmy-nominated guest appearance as Maj. Gen. Bartford Hamilton Steele in "The General Flipped at Dawn." Steele appears to be a by-the-book, high-ranking officer but everyone soon realizes, especially Alan Alda's Hawkeye who he tries to court-martial, that he's a raving loon. Morgan's hysterical performance was a thing of beauty. He could be just as funny as Potter but in a completely different way. Potter also frequently touched your heart as he drank a toast when the last of his old comrades died.We drink a toast to you, Harry Morgan. RIP.

Tweet

Labels: Alda, Awards, Aykroyd, H. Fonda, Jack Webb, Kazan, Lee J. Cobb, Lumet, Malden, Obituary, Shelley Winters, Sylvia Sidney, Television, The Simpsons, Theater, Wellman

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, July 05, 2011

The longest tracking shot ever

By Edward Copeland

OK, technically, Slacker isn't one unbroken shot, but it almost feels that way, even 20 years after it finally completed its long, arduous journey toward a major U.S. release on this date (major for an indie arthouse film anyway). It only took writer-director Richard Linklater two months to film it in the summer of 1989, but the task of getting it released took two years. On the commentary track for the Criterion DVD that Linklater recorded in 2004, he says that he wanted the film to be "one long take" and re-watching it, Slacker still stuns me by how close it comes to evoking that feel, even though it's artifice. In many ways, it's an experimental film, so it's quite remarkable that its appeal became as broad as it did, that it remains so enjoyable on repeat viewings and that it even got made in the first place, especially for that fabled budget of $23,000.

Slacker covers 24 hours in Austin, though as Linklater points out in his commentary, it's actually only a small portion of the Texas city — confined mainly to the west side of the University of Texas campus and a few downtown clubs. The film contains no plot or narrative or central characters (In fact, characters don't get names as much as descriptions.); it just follows one person who then leads to another and another and so on, as if it's a funky sort of relay race with the baton constantly being passed. Miraculously, almost every character we meet and every short scene that plays out turns out to be as entertaining or fascinating as the one that came before. Slacker truly lacks any dead spots because we're watching all forms of humanity on display and though it's fiction, it almost plays like a documentary. "It seems spontaneous, but we always knew what was coming next," Linklater says on the DVD. The writer-director also is the first character to launch the chain, playing what he says is sort of a continuation of his first full-length feature It's Impossible to Learn to Plow By Reading Books, which is on the Criterion DVD and I'd planned to watch but simply ran out of time. Linklater plays Should Have Stayed at Bus Station who gets into a cab and tells Taxi Driver (Rudy Basquez) about a dream he had, which more or less sums up the idea behind Slacker itself.

"Do you ever have those dreams that are just completely real? I mean, they're so vivid it's just like completely real. It's like there's always something bizarre going on in those.…There's always someone getting run over or something really weird.…Anyway, so this dream I just had was just like that except instead of anything bizarre going on, there was nothing going on at all.…I was just traveling around…When I was at home, I was flipping through TV stations endlessly.Reading. I mean, how many dreams do you have where read in a dream?…it was like the premise for this whole book was that every thought you have creates its own reality, you know? It's like every choice or decision you make, the thing you choose not to do, fractions off and becomes its own reality, you know, and just goes on from there, forever. I mean, it's like you know in The Wizard of Oz where Dorothy meets the Scarecrow and they do that little dance at the crossroads and they think about going in all those directions and they end up going in that one direction? All those other directions, just because they thought about them, become separate realities. I mean, they just went on from there and lived the rest of their life…you know, entirely different movies, but we'll never see it because we're kind of trapped in this one reality restriction type of thing."

His full monologue runs much longer than that, but I had to cut it down a bit, but you don't know it the first time you see Slacker, but in hindsight and later viewings, he's giving you a lot of foreshadowing. For one thing, he mentions there is "always someone getting run over" and when he exits the cab to start the first handoff, that's the first thing he sees: a mother, Roadkill (Jean Caffeine) plowed down by a car we'll learn was driven by her Hit-and-Run Son (Mark James) as a couple of witnesses gather. Which one will we follow though? The movie of the Jogger (Jan Hockey) or the

businessman Running Late (Stephen Hockey)? Maybe the third person to appear on the scene, Grocery Grabber of Death's Bounty (Samuel Dietert). Nah. They all were just links waiting for the Hit-and-Run Son's car to reappear so we can see his story which, according to Linklater, may have been based on a true story which had become sort of a neighborhood legend, since the murdering son waited around for the police — reading no less. He also talks about flipping channels endlessly and we will eventually meet Video Backpacker (Kalman Spellitich) who has flooded his room with all types of TVs showing different images — he even has one strapped to his back. Should Have Stayed at Bus Station says the book with the different realities concept he described must have been written by him since it's in his dream and the part is played by Linklater after all, who described the structure of the film as "jumping from movie to movie" and said the content of the film was of less concern to him than the form. When I first saw Slacker, I laughed when Should Have Stayed at Bus Station made the comparison to The Wizard of Oz because ever since I was a kid and saw that movie for the first time, I always wondered what would happen if Dorothy and the gang decided to follow one of those brick roads of another color. They had to lead somewhere, didn't they?

businessman Running Late (Stephen Hockey)? Maybe the third person to appear on the scene, Grocery Grabber of Death's Bounty (Samuel Dietert). Nah. They all were just links waiting for the Hit-and-Run Son's car to reappear so we can see his story which, according to Linklater, may have been based on a true story which had become sort of a neighborhood legend, since the murdering son waited around for the police — reading no less. He also talks about flipping channels endlessly and we will eventually meet Video Backpacker (Kalman Spellitich) who has flooded his room with all types of TVs showing different images — he even has one strapped to his back. Should Have Stayed at Bus Station says the book with the different realities concept he described must have been written by him since it's in his dream and the part is played by Linklater after all, who described the structure of the film as "jumping from movie to movie" and said the content of the film was of less concern to him than the form. When I first saw Slacker, I laughed when Should Have Stayed at Bus Station made the comparison to The Wizard of Oz because ever since I was a kid and saw that movie for the first time, I always wondered what would happen if Dorothy and the gang decided to follow one of those brick roads of another color. They had to lead somewhere, didn't they?

While true that the structure formed the basis for the idea for Slacker, the budding filmmaker, who celebrated his 29th birthday during shooting (It's hard to believe Linklater is 51 now), also selected the premise of a plotless film where one character leads to the next as a matter of convenience. It eliminated the need for continuity concerns. A character once they appeared wouldn't be coming back later in the film, so hairstyle changes or other things weren't a worry. However, because Linklater wanted the movie to appear seamless, every decision on where to make a cut or edit became a "big deal." Since the film aimed to cover a 24-hour period but wasn't going to run 24 hours, at some point the movie had to switch from day to night and he did that with a dissolve that, at least in 2004 when he recorded the commentary, he still felt "was a cheat" 15 years after he'd done it. He employed 16mm, Super 8 and even a Fisher-Price toy "PixelVision" cameras to film the movie which were able to produce a viewable 16mm print but, Linklater admits, did present problems getting all actors in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio frame. Otherwise, Linklater had a relatively easy shoot, even laying down dolly tracks on public streets without permits and not getting in trouble for doing so.

Linklater did have some tryouts for roles in the movie, but many were played by friends, many who seemed to have been former or future roommates. His funniest recurring comment on the DVD is that everyone in the cast is a musician unless otherwise noted. That applied to the person in the movie's most infamous scene, Teresa Taylor, who portrays Pap Smear Pusher and also was the drummer for the band The Butthole Surfers, whose song "Strangers Die Everyday" plays over the end credits. What's forgotten in the memory of someone trying to sell Madonna's pap smear is that before she brings that up, she tells a pretty hilarious story about a man speeding down a highway squawking like a chicken and firing a gun in the air with one bullet ricocheting inside the car for awhile and another lodging in a girl's ponytail and the girl "called the pigs." An interesting note from Linklater's commentary track is that he wanted to avoid references that might date the movie too much and he pondered, since it was filmed in 1989 and Madonna had only been a star for about five years at that point, if her fame would last long enough that audiences well into the future would know who she was.

Because so many in the cast are playing characters that resemble themselves, you're not certain whether to praise someone's acting because you can't be sure that acting is taking place. However, there were some real or beginning actors in the cast, including a person who played a character that made quite an impression and that's Charles Gunning as Hitchhiker. Gunning had started acting not very long before Slacker: Joel and Ethan Coen discovered him and put him in Miller's Crossing. His scenes contain so much power that I believe he's the only character who doesn't just hand off to the next person he encounters: Linklater wisely lets him

linger a little longer. In fact, Linklater liked him so much that he used him again in his underrated film The Newton Boys and Waking Life. As Hitchhiker, Gunning's off-kilter deadpan delivery truly proves riotous, whether he's telling Nova (Scott Van Horn), the passenger in the convertible he's hitched a ride in, that he's coming from a funeral and Nova says he's sorry, "Fuck it — should have let him rot." As he explains further that the dead man was his stepfather who always got drunk and beat on his mom, him and his siblings. "He was a serious fuckup. I'm glad the son of a bitch is dead. Thought he'd never die.…I couldn't wait for the bastard to die. (pause) I'll probably go back next week and dance on his grave." Once he's left the car, even though he's already bummed a cigarette off the guys in the car, he asks a man at an outdoor cafe if he can have one, palms two and sticks the extra one behind his ear. He then gets stopped by the Video Interviewer (Tammy Ringler) who wants to see if he'll answer some questions, which he agrees to do. She asks if he voted in the last election. "Hell no — I've got less important things to do." She asks what he does to earn a living. "You mean work? To hell with the kind of work you have to do to earn a living. All that does is fill the bellies of the pigs that exploit us. Hey, look at me — I'm making it. I may live badly, but at least I don't have to work to do it." Just reading his lines doesn't do justice to Gunning's delivery. Sadly, Gunning died in December 2002 due to injuries from a car wreck. He was 51.

linger a little longer. In fact, Linklater liked him so much that he used him again in his underrated film The Newton Boys and Waking Life. As Hitchhiker, Gunning's off-kilter deadpan delivery truly proves riotous, whether he's telling Nova (Scott Van Horn), the passenger in the convertible he's hitched a ride in, that he's coming from a funeral and Nova says he's sorry, "Fuck it — should have let him rot." As he explains further that the dead man was his stepfather who always got drunk and beat on his mom, him and his siblings. "He was a serious fuckup. I'm glad the son of a bitch is dead. Thought he'd never die.…I couldn't wait for the bastard to die. (pause) I'll probably go back next week and dance on his grave." Once he's left the car, even though he's already bummed a cigarette off the guys in the car, he asks a man at an outdoor cafe if he can have one, palms two and sticks the extra one behind his ear. He then gets stopped by the Video Interviewer (Tammy Ringler) who wants to see if he'll answer some questions, which he agrees to do. She asks if he voted in the last election. "Hell no — I've got less important things to do." She asks what he does to earn a living. "You mean work? To hell with the kind of work you have to do to earn a living. All that does is fill the bellies of the pigs that exploit us. Hey, look at me — I'm making it. I may live badly, but at least I don't have to work to do it." Just reading his lines doesn't do justice to Gunning's delivery. Sadly, Gunning died in December 2002 due to injuries from a car wreck. He was 51.Members of the cast who aren't actors or musicians do pretty damn well too, though I suppose being a philosophy professor at UT as Louis Mackey was at the time when he played the Old Anarchist requires performing skills as well and Mackey shares them delightfully in another of my favorite scenes. The Old Anarchist and his daughter Delia (Kathy McCarty) enter the movie as they witness the apprehension of the Shoplifter (Shelly Kristaponis) outside a grocery store. Delia tells her father that Shoplifter was in her ethics class and he comments, "Well, I'm always glad to see any young person doing SOMETHING" only he's referring to the shoplifting, not the ethics class. When they arrive home, they happen upon Burglar (Michael Laird), a

particularly inept criminal who fumbles with his gun and didn't get a chance to try to steal anything because he was reading one of the many books in the house. The Old Anarchist easily takes the gun from Burglar and befriends him immediately, telling him, "No one's going to call the police. I hate the police more than you probably. Never done me any good." Just the idea of some aging, white-haired anarchist who says the things he does was pretty damn daring for a filmmaker trying to get his career off the ground and forming his first major work around a specific city. Old Anarchist would praise Leon Czolgosz as an American hero and lament not being on campus the day Charles Whitman went up into the tower with a sniper's rifle "because my fucking wife — God rest her soul — she had some stupid appointment that day. So during this town's finest hour, where the hell was I? Way the hell out on South Congress." You would think there would still be enough survivors or relatives of Whitman's victims in Austin that the film would have been reviled there, but it was embraced. Linklater says on the DVD that he "really thought Slacker had something in it to alienate everybody on some level or another." In referring to the Whitman lines, he even referenced what I thought of when I saw it — Alan Alda's character's formula in Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors : "Comedy equals tragedy plus time." Mackey though plays the nutty old kook wonderfully as he tries to impart life lessons on the would-be thief. "It's taken my entire life, but I can now say that I've practically given up on not only my own people but for mankind in its entirety. I can only address myself to singular human beings now."

particularly inept criminal who fumbles with his gun and didn't get a chance to try to steal anything because he was reading one of the many books in the house. The Old Anarchist easily takes the gun from Burglar and befriends him immediately, telling him, "No one's going to call the police. I hate the police more than you probably. Never done me any good." Just the idea of some aging, white-haired anarchist who says the things he does was pretty damn daring for a filmmaker trying to get his career off the ground and forming his first major work around a specific city. Old Anarchist would praise Leon Czolgosz as an American hero and lament not being on campus the day Charles Whitman went up into the tower with a sniper's rifle "because my fucking wife — God rest her soul — she had some stupid appointment that day. So during this town's finest hour, where the hell was I? Way the hell out on South Congress." You would think there would still be enough survivors or relatives of Whitman's victims in Austin that the film would have been reviled there, but it was embraced. Linklater says on the DVD that he "really thought Slacker had something in it to alienate everybody on some level or another." In referring to the Whitman lines, he even referenced what I thought of when I saw it — Alan Alda's character's formula in Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors : "Comedy equals tragedy plus time." Mackey though plays the nutty old kook wonderfully as he tries to impart life lessons on the would-be thief. "It's taken my entire life, but I can now say that I've practically given up on not only my own people but for mankind in its entirety. I can only address myself to singular human beings now."As far as I can remember, Slacker never played in my city in 1991 as was often the case with many arthouse films back then. So, as would often happen, I would either drive to Dallas by myself or with friends to catch those types of movies, usually at the Inwood on Lovers Lane. That's where I saw Slacker. Austin may have been able to get past the Charles Whitman part, but I wasn't there to know if they laughed. I do know

however that Dallas moviegoers still carry sensitivity relating to JFK's assassination. The whole scene, involving the character called JFK Buff (John Slate) is pretty funny. Linklater even calls it one of, if not his favorite scene in the film. However, when JFK Buff appeared on screen wearing a T-shirt with a big picture of Ruby shooting Oswald, my visiting friends and I all laughed out loud. I don't think our laughter was particularly noisy — it just stood out from the others in the audience who were from Dallas and in complete silence. I even caught one or two people look our direction. If I weren't a strict proponent of not talking during movies, I might have said, "Relax. Neither you nor your city killed him and that was almost 30 years ago (at that time)." As you would expect, JFK Buff was an authority on all things Kennedy, conspiracy and otherwise and he's advising a young woman called Girlfriend (she's not his, but played by Sarah Harmon) who is browsing through the Kennedy section of a bookstore which are the best books to read. He's also writing his own JFK book which he wanted to call Profiles in Cowardice, but his publisher suggested issuing as Conspiracy-a-Go-Go. He suggests she "snap up" the book Forgive My Grief which has the story of how Oswald and Officer Tippet were supposed to have their "'breakfast of infamy.' Yeah, the waitresses went on the record, in the Warren Report, as saying Oswald didn't like his eggs and used bad language," JFK Buff tells her. Ironically, as recently as 2006, John Slate worked as the city archivist for Dallas so he actually works with Kennedy assassination documents.

however that Dallas moviegoers still carry sensitivity relating to JFK's assassination. The whole scene, involving the character called JFK Buff (John Slate) is pretty funny. Linklater even calls it one of, if not his favorite scene in the film. However, when JFK Buff appeared on screen wearing a T-shirt with a big picture of Ruby shooting Oswald, my visiting friends and I all laughed out loud. I don't think our laughter was particularly noisy — it just stood out from the others in the audience who were from Dallas and in complete silence. I even caught one or two people look our direction. If I weren't a strict proponent of not talking during movies, I might have said, "Relax. Neither you nor your city killed him and that was almost 30 years ago (at that time)." As you would expect, JFK Buff was an authority on all things Kennedy, conspiracy and otherwise and he's advising a young woman called Girlfriend (she's not his, but played by Sarah Harmon) who is browsing through the Kennedy section of a bookstore which are the best books to read. He's also writing his own JFK book which he wanted to call Profiles in Cowardice, but his publisher suggested issuing as Conspiracy-a-Go-Go. He suggests she "snap up" the book Forgive My Grief which has the story of how Oswald and Officer Tippet were supposed to have their "'breakfast of infamy.' Yeah, the waitresses went on the record, in the Warren Report, as saying Oswald didn't like his eggs and used bad language," JFK Buff tells her. Ironically, as recently as 2006, John Slate worked as the city archivist for Dallas so he actually works with Kennedy assassination documents. When you have a 100 minute film that's stuffed full of so many unique and interesting characters and memorable moments, you can't possibly highlight them all, no matter how much you might want to pay tribute to them on this anniversary. There's the Dostoyevsky Wannabe (Brecht Andersch) "Who's ever written the great work about the immense effort required NOT to create?"; I'd really love to write at length about the

scene with Been on Moon (Jerry Deloney) "So they must like children too, because FBI statistics since 1980 say that 350,000 children are just missing — they disappeared. There's not that many perverts around."; Bush Basher (Daniel Dugan) and his ideas on how the nonvoting majority wins ever election; Prodder (Steve Anderson) who makes Jilted Boyfriend (Kevin Whitley) perform ritual sacrifice of items related to his ex-girlfriend with Boyfriend (Robert Pierson) along to watch; Scooby-Doo Philosopher (R. Malice) explaining how the cartoon teaches kids about bribery and how he thinks Smurfs has something to do with Krishna so people will be used to seeing blue people; Having a Breakthrough Day (D. Montgomery) handing out her oblique strategy cards and I could keep going, but I'll stop with Old Man (Joseph Jones), who appears toward the end walking down a road talking into a tape recorder and saying, "When young, we mourn for one woman. As we grow old, for women in general."

scene with Been on Moon (Jerry Deloney) "So they must like children too, because FBI statistics since 1980 say that 350,000 children are just missing — they disappeared. There's not that many perverts around."; Bush Basher (Daniel Dugan) and his ideas on how the nonvoting majority wins ever election; Prodder (Steve Anderson) who makes Jilted Boyfriend (Kevin Whitley) perform ritual sacrifice of items related to his ex-girlfriend with Boyfriend (Robert Pierson) along to watch; Scooby-Doo Philosopher (R. Malice) explaining how the cartoon teaches kids about bribery and how he thinks Smurfs has something to do with Krishna so people will be used to seeing blue people; Having a Breakthrough Day (D. Montgomery) handing out her oblique strategy cards and I could keep going, but I'll stop with Old Man (Joseph Jones), who appears toward the end walking down a road talking into a tape recorder and saying, "When young, we mourn for one woman. As we grow old, for women in general."When it comes to picking the best part of Slacker, selecting that choice doesn't require any mulling or contemplation because Richard Linklater himself serves as the film's strongest and longest-lasting legacy. Slacker belongs in that same category of film as Citizen Kane (I'm not saying in terms of greatness) where its structure guarantees its freshness because it's so unique no matter how many times you see it, you're never certain what comes next. Not all of Linklater's films have turned out to be gems, but then that's the case with most great filmmakers. Robert Altman and Billy Wilder had their duds too. In fact, with the exception of School of Rock (which I love) and The Bad News Bears remake (which I still refuse to see), he reminds me of Altman in the way he avoids commercial prospects when picking projects. He's also been very prolific, to the point that I think some of his movies escaped people's notice altogether.

Look at the body of work he's compiled since Slacker: the great Dazed and Confused; the exquisite yet complete change-of-pace that was Before Sunrise, which I got to interview him about on the phone; the very good adaptation of Eric Bogosian's off-Broadway play SubUrbia; The Newton Boys, long overdue for reappraisal; Waking Life, which admittedly works better as an experiment in style than as a film; the underseen and very strong Tape featuring searing work by Robert Sean Leonard, Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke; the aforementioned blast that is The School of Rock; Before Sunset, the unlikeliest sequel ever made; turning a nonfiction best seller into a fiction film with the same message in Fast Food Nation; A Scanner Darkly, his venture into Philip K. Dick and sci-fi using the animation technique from Waking Life; Inning by Inning: A Portrait of a Coach, a documentary about Texas' baseball coach who holds the most wins in NCAA history, a film I didn't even know about until I was going through IMDb; and his most recent film, Me and Orson Welles, which is simply one of the best he's made. Later this year, there should be a new Linklater crime comedy called Bernie that reunites him with Jack Black and Matthew McConaughey and also starring Shirley MacLaine.

Back to Slacker, the film I'm saluting. On that commentary, Linklater says that much of the movie really revolves around deciding whether or not to do something or, as he put it, "To act or not to act." If that is the question Slacker poses, Linklater chose the positive response and film lovers are better off for him doing so.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Alda, Altman, Coens, Hawke, Linklater, MacLaine, Movie Tributes, Remakes, Sequels, Welles, Wilder, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, November 28, 2010

From the Vault: Crimes and Misdemeanors

"Comedy is tragedy plus time," a character says in Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors which perfectly illustrates both dramatic subjects.

Crimes takes time to get into its rhythm, but the longer it goes on, the better it gets.

It has become almost a cliche to hear people complain about Woody's recent ventures into drama (September, Another Woman). They say, "We like his earlier, funny ones." They have missed the boat. Allen is as assured a writer-director of drama as he is of comedy, and this is just one of the many levels in which this film works.

Crimes and Misdemeanors tells two loosely connected stories. The dramatic one concerns an ophthalmologist (Martin Landau) who is being blackmailed by his jealous mistress (Anjelica Huston) who wants him to leave his wife (Claire Bloom). The comic one concerns a documentary filmmaker (Allen) who is forced into making a movie about his obnoxious, successful brother-in-law, a TV producer played by Alan Alda.

Allen is unhappily married and begins to fall for the documentary's producer (Mia Farrow). The twists of the stories are part of its enjoyment, so I won't delve any further. However, whereas Hannah and Her Sisters took his typical neurotic, God-doubting Jewish New Yorker and added a dash of optimism, Crimes goes the other direction.

This is a film of and about the 1980s. It is cynical and has a lot to say on all the topics Allen has specialized in for years — religion, relationships and success.

Religion is what binds the two otherwise unrelated stories together. Landau is treating Allen's other brother-in-law, an optimistic rabbi (Sam Waterston) who is slowly going blind. Waterston's character is, in a way, the most important character in the film, in keeping with the eyes motif established early on.

Landau and Allen both view the world as harsh and devoid of values while Waterston insists that there is a real moral structure out there involving forgiveness and a higher power. Waterston's blindness helps to show the film's message that in these times, a sin seems to be a sin only if you get caught.

Another strand of this philosophical approach is a professor that Woody's character wants to make a documentary about. The professor speaks of religious optimism and how a loving God is beyond man's capacity for reason. He talks about how love is a contradiction and life is painful but we need the pain. His words, and his later off-screen action, help lend the somewhat nihilistic view the film ultimately presents: that morality only exists for those who have it.

The film is full of great lines and great performances, something one expects from a Woody Allen film, but it also is the perfect fusion of Allen's filmic styles. There is Landau, discussing his problems with Waterston (in what may or may not be an imagined conversation) where he tells the rabbi that God is a luxury he can't afford. There is a virtual cascade of classic Woody lines such as "The last time I was inside a woman was when I visited the Statue of Liberty." It also contains some perfect casting choices: There's enough of a resemblance to believe that Landau and Jerry Orbach are indeed brothers.

There are the stylistic and story elements that stem from Allen's love of Ingmar Bergman. In fact, he even uses Bergman's frequent cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, and Nykvist contributes a golden, almost mildewy look to the proceedings. Technically, this is among Woody's best.

His direction has evolved over the years and fully complements his screenplay. Woody's character spends a lot of time taking his niece (Jenny Nichols) to old movies playing in revival houses: musicals, classic gangster flicks, the works. This contributes to the idea that, as much as Woody loves these films, he can't make them in this day and age. If you want happy endings, go to Hollywood. If you want reality, go to New York, especially if Woody Allen is your chauffeur.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, A. Huston, Alda, Ingmar Bergman, Landau, Mia Farrow, Orbach, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, April 24, 2010

From the Vault: Manhattan Murder Mystery

After two films that played like warmed-up leftovers (Husbands and Wives, Alice) and one failed exercise in style (Shadows and Fog), Woody Allen returns to form with an entertaining comic mystery.

Allen fuses disparate elements of his films and concocts Manhattan Murder Mystery, a joyously light romp that succeeds both on its own terms and as an homage to a classic genre.

The film marks the first screen teaming of Allen and Diane Keaton since 1979's Manhattan and they easily slip back into the comic rapport they generated in Annie Hall and other great comedies from the 1970s.

Keaton and Allen play a long-married Manhattan couple whose son has left the nest, leaving their lives with a bit less spark. Allen busies himself with his work as a book editor while Keaton toys with the idea of opening a restaurant.

Keaton soon finds a new diversion when the day after the spouses are invited to a neighbors for drinks for the first time, the wife drops dead and Keaton, aided by a newly divorced playwright friend (Alan Alda) becomes convicted that it was murder, not a heart attack, that did in the woman.

To divulge much more would ruin some of the mystery's fun, which is rather satisfying for what is essentially a light comedy. The details — disappearing bodies, etc. — come straight out of films like Hope and Crosby's Road pictures and various Abbott and Costello flicks. Allen and Keaton dive into neurotic modern takes on these character types with criminal glee.

Allen's direction moves the film briskly along and he does have some great sequences, ranging from the climax in a movie house while Lady from Shanghai plays in the background to an investigative trip to a molten steel warehouse.

Nice, quieter moments abound as well such as a speculative dinner with Allen, Keaton, Alda and Anjelica Huston, playing one of Allen's writers, and another where Huston teaches Allen how to play poker.

One demerit to Allen's direction comes from his continued misuse of hand-held cameras. While the effect doesn't jar the viewer as much as in Husband and Wives, it seems even more out of place here.

Alda and Huston lend able comic support while Keaton's funny performance is infectious, especially when combined with Allen's priceless expressions. The script, co-written by Marshall Brickman and actually predating Annie Hall, provides a higher number of one-liners than most Allen films of late.

While Manhattan Murder Mystery doesn't rank in the highest tier of Allen's films, it is by far the funniest he's made since Broadway Danny Rose.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, A. Huston, Abbott and Costello, Alda, Diane Keaton, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, March 09, 2010

Old Altmans never die (or fade away)

visions of the things to be

the pains that are withheld for me

I realize and I can see...

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

By Edward Copeland

It began life as a novel by Richard Hooker, then Robert Altman transferred MASH into a movie and made his reputation. Later, Larry Gelbart transformed that film into a television comedy and made it a landmark series, adding the asterisks to the title M*A*S*H. Altman's film had its New York premiere in January 1970, but back in those days of slow, platform releases, there was no one day when it spread to the rest of the U.S. at once. The best I can find is that it was in March, so I pick today to mark the movie's 40th anniversary.

all our little joys relate

without that ever-present hate

but now I know that it's too late, and...

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

When Johnny Mandel's theme played week after week on the CBS series for 11 seasons, I often wondered what it would have been like if they'd kept Altman's son's Mike's lyrics for "Suicide Is Painless" as well. The sitcom may have taken MASH as its essential template, but they had to draw the line somewhere. (Even an iconoclastic risk taker such as Altman had to let some things from the novel go that early in his career, so we weren't treated to scenes of Elliott Gould as Trapper John dressed as Christ, flying around Korea on a cross suspended from a helicopter and signing autographs to raise money for Ho-Jon's college fund.)

Still, Altman's movie certainly broke ground as far as war movies were concerned and definitely formed the

initial portrait of what a Robert Altman film usually was like: large casts, overlapping dialogue using unusual recording techniques, largely plotless and when they worked, as they did with MASH, great films that changed the medium and that couldn't be mistaken as the work of another director. Watching MASH again for this piece, with its dizzying overheads of helicopters bringing the wounded to the 4077th, I thought of a comparison to another Altman opening for the very first time that came 23 years later: Short Cuts. Only in that instance, the helicopters weren't bearing the injured, they were spraying the injured with pesticide as part of California's battle with the Mediterranean fruit fly.

initial portrait of what a Robert Altman film usually was like: large casts, overlapping dialogue using unusual recording techniques, largely plotless and when they worked, as they did with MASH, great films that changed the medium and that couldn't be mistaken as the work of another director. Watching MASH again for this piece, with its dizzying overheads of helicopters bringing the wounded to the 4077th, I thought of a comparison to another Altman opening for the very first time that came 23 years later: Short Cuts. Only in that instance, the helicopters weren't bearing the injured, they were spraying the injured with pesticide as part of California's battle with the Mediterranean fruit fly.I'm gonna lose it anyway

The losing card I'll someday lay

so this is all I have to say.

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

People who know the 4077th only from the TV series will certainly recognize the essential elements in the Altman movie, but they also will discover quite a few differences that follow the novel more closely. Only one cast member from the movie became a regular on the series and that was Gary Burghoff repeating his role as Radar. While the series began basically as Hawkeye (the great Donald Sutherland in the film) and Trapper

against the world, the movie had a third surgeon: Duke, played by Tom Skerritt. While many of the MASH characters share names with the M*A*S*H characters, in many areas they bear little resemblance. Hawkeye is a married man in the movie, not that it prevents his playing around, not Alan Alda's single lothario from the series. Robert Duvall's Frank Burns lives light years away from the buffoonish character Larry Linville grew tired of playing on TV. He's a strictly religious, nondrinker who is teaching Ho-Jon to learn English through the Bible. ("Were you on this religious kick at home or did you crack up over here?" Sutherland's Hawkeye asks Frank as he prays beside his cot.) That doesn't prevent Frank from falling prey his lust for Maj. Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan (Sally Kellerman). However, in the movie, Burns gets carted away early in a strait-jacket after a single prank.

against the world, the movie had a third surgeon: Duke, played by Tom Skerritt. While many of the MASH characters share names with the M*A*S*H characters, in many areas they bear little resemblance. Hawkeye is a married man in the movie, not that it prevents his playing around, not Alan Alda's single lothario from the series. Robert Duvall's Frank Burns lives light years away from the buffoonish character Larry Linville grew tired of playing on TV. He's a strictly religious, nondrinker who is teaching Ho-Jon to learn English through the Bible. ("Were you on this religious kick at home or did you crack up over here?" Sutherland's Hawkeye asks Frank as he prays beside his cot.) That doesn't prevent Frank from falling prey his lust for Maj. Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan (Sally Kellerman). However, in the movie, Burns gets carted away early in a strait-jacket after a single prank.And lay it down before I'm beat

and to another give my seat

for that's the only painless feat.

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

MASH is neither a conventional comedy nor a conventional war film and, since this a Robert Altman movie, you shouldn't expect a conventional climax either. Besides, in a film that is essentially untethered from any

plot, how could there be? So, the big finish for the film's third act is anything but obvious: It's a football game (Shades of the Marx Brothers' Horse Feathers). The 4077th gets challenged to a game by the commander of the 325th Evac. As General Hammond (G. Wood) tells Col. Henry Blake (Roger Bowen) in proposing the game, football is one of the "best gimmicks to keep the American way of life going in Asia." Wood did re-create his role as Hammond in a couple of guest appearances in the early seasons of the TV series. In an eerie coincidence, when McLean Stevenson, the sitcom's memorable Henry Blake died, the following day Bowen died. It almost was like Bowen knew that his death would get little notice unless he piggybacked on Stevenson's as the other Henry Blake. Hammond, of course, has his own ringer, so Trapper and Hawkeye set out to obtain one for their team, a neurosurgeon named Dr. Jones who was better known in his college football days as Spearchucker

plot, how could there be? So, the big finish for the film's third act is anything but obvious: It's a football game (Shades of the Marx Brothers' Horse Feathers). The 4077th gets challenged to a game by the commander of the 325th Evac. As General Hammond (G. Wood) tells Col. Henry Blake (Roger Bowen) in proposing the game, football is one of the "best gimmicks to keep the American way of life going in Asia." Wood did re-create his role as Hammond in a couple of guest appearances in the early seasons of the TV series. In an eerie coincidence, when McLean Stevenson, the sitcom's memorable Henry Blake died, the following day Bowen died. It almost was like Bowen knew that his death would get little notice unless he piggybacked on Stevenson's as the other Henry Blake. Hammond, of course, has his own ringer, so Trapper and Hawkeye set out to obtain one for their team, a neurosurgeon named Dr. Jones who was better known in his college football days as Spearchucker Jones (the film debut of Fred Williamson). They try to brush off the racist nickname by having some ask him why he's called Spearchucker and having him answer that he used to throw the javelin. While I worship Altman, one thing I never quite understood was his insistence that the TV show was racist, specifically against the Koreans, but if anyone can notice any appreciable difference betweeen the film and TV show on that count, I'd love to hear the argument. One of the biggest cheerleaders for the game is Hot Lips and if I have a problem with the film, it's the quick and inexplicable conversion of the Margaret Houlihan character. She's introduced as a no-nonsense, by-the-book Army major, constantly being humiliated by the pranksters of The Swamp (and a wonderful Oscar-

Jones (the film debut of Fred Williamson). They try to brush off the racist nickname by having some ask him why he's called Spearchucker and having him answer that he used to throw the javelin. While I worship Altman, one thing I never quite understood was his insistence that the TV show was racist, specifically against the Koreans, but if anyone can notice any appreciable difference betweeen the film and TV show on that count, I'd love to hear the argument. One of the biggest cheerleaders for the game is Hot Lips and if I have a problem with the film, it's the quick and inexplicable conversion of the Margaret Houlihan character. She's introduced as a no-nonsense, by-the-book Army major, constantly being humiliated by the pranksters of The Swamp (and a wonderful Oscar- nominated performance from Kellerman). When Hawkeye first meets her, always out to put the make on some new female flesh, he gives it to her for putting him off his lust and that she's just a regular Army clown and he's going back to his tent to drink scotch. Houlihan vents her outrage to the film's Father Mulcahy (Rene Auberjonois), known here as Dago Red, asking how someone so crass as Hawkeye could reach a position of responsibility in the Army. "He was drafted," the priest replies. When the gang exposes her shower and nudity to the camp, she has a breakdown to Henry, insisting that, "This is not a hospital, it's an insane asylum!" Then, before you know it, she's fooling around with Duke and playing cheerleader. It's odd, but it's still a minor criticism in an otherwise great film. (I'm just thinking off the top of my head, but has any great movie been turned into an almost equally great television show the way MASH was?)

nominated performance from Kellerman). When Hawkeye first meets her, always out to put the make on some new female flesh, he gives it to her for putting him off his lust and that she's just a regular Army clown and he's going back to his tent to drink scotch. Houlihan vents her outrage to the film's Father Mulcahy (Rene Auberjonois), known here as Dago Red, asking how someone so crass as Hawkeye could reach a position of responsibility in the Army. "He was drafted," the priest replies. When the gang exposes her shower and nudity to the camp, she has a breakdown to Henry, insisting that, "This is not a hospital, it's an insane asylum!" Then, before you know it, she's fooling around with Duke and playing cheerleader. It's odd, but it's still a minor criticism in an otherwise great film. (I'm just thinking off the top of my head, but has any great movie been turned into an almost equally great television show the way MASH was?)It doesn't hurt when it begins

But as it works its way on in

The pain grows stronger...watch it grin, but...

That suicide is painless

It brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

As I mentioned before, MASH is the first example of the Robert Altman ensemble that he'd become famous for and many of the actors who would become part of the unofficial Altman repertory company would make appearances here. Elliott Gould would follow his great work as Trapper John with similarly solid work in Altman's The Long Goodbye and California Split and would appear as himself in Nashville and The Player.

Skerritt returned to Altman for Thieves Like Us. Kellerman returned for Brewster McCloud and Ready to Wear and as herself in The Player. Duvall first appeared in Altman's Countdown and then reunited with him on The Gingerbread Man. Rene Auberjonois rejoined the director for Brewster McCloud, McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Images. David Arkin also appeared in The Long Goodbye, Nashville and Popeye. Last, but certainly not least, MASH marked the appearance of Michael Murphy who may have been the most regular of Altman regulars, appearing in McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville, Brewster McCloud, Kansas City, Countdown, That Cold Day in the Park, Tanner '88, Tanner on Tanner, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial and even episodes of TV's Combat, Kraft Suspense Theater and the 1964 TV movie Nightmare in Chicago. It also marked the film debut of Bud Cort who returned in Brewster McCloud. Surprisingly, the actor who gave the best performance in MASH never worked with Altman again. I always go back and forth as to whether or not Donald Sutherland's Hawkeye Pierce is lead or supporting but in either case, it is brilliant and yet another example of the outrage that this man has never received an Oscar nomination for anything. His little whistle as Hawkeye alone is a thing of wonder.

Skerritt returned to Altman for Thieves Like Us. Kellerman returned for Brewster McCloud and Ready to Wear and as herself in The Player. Duvall first appeared in Altman's Countdown and then reunited with him on The Gingerbread Man. Rene Auberjonois rejoined the director for Brewster McCloud, McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Images. David Arkin also appeared in The Long Goodbye, Nashville and Popeye. Last, but certainly not least, MASH marked the appearance of Michael Murphy who may have been the most regular of Altman regulars, appearing in McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville, Brewster McCloud, Kansas City, Countdown, That Cold Day in the Park, Tanner '88, Tanner on Tanner, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial and even episodes of TV's Combat, Kraft Suspense Theater and the 1964 TV movie Nightmare in Chicago. It also marked the film debut of Bud Cort who returned in Brewster McCloud. Surprisingly, the actor who gave the best performance in MASH never worked with Altman again. I always go back and forth as to whether or not Donald Sutherland's Hawkeye Pierce is lead or supporting but in either case, it is brilliant and yet another example of the outrage that this man has never received an Oscar nomination for anything. His little whistle as Hawkeye alone is a thing of wonder.to answer questions that are key

'is it to be or not to be'

and I replied 'oh why ask me?'

'Cause suicide is painless

it brings on many changes

and I can take or leave it if I please.

...and you can do the same thing if you choose.

Alright, about that song. The painless it refers to is not just the idea that suicide is free from hurt but refers to a very specific character in MASH: Painless Pole the dentist, portrayed by another Altman regular, John

Schuck. Painless has a reputation not only as a Don Juan but as being particularly well endowed, so much so that when it's his turn in the shower, people take turns gazing upon his impressive manhood. The song opens the film but it is reprised again later when Painless, after a bout of impotence, becomes convinced that he may carry some latent homosexuality and even though he's never had any form of gay sex, he figures it's just a matter of time so he goes to Hawkeye for help for a way out. A last supper is arranged, where Painless will take the Black Capsule and commit suicide. Of course, Hawkeye has no intention of helping Painless to kill himself but instead enlists Lt. Dish (Jo Ann Pflug) to sleep with the unconscious Painless and restore his confidence. It works. There even is an instrumental, heavenly choir version of "Suicide Is Painless" to accompany the scene.

Schuck. Painless has a reputation not only as a Don Juan but as being particularly well endowed, so much so that when it's his turn in the shower, people take turns gazing upon his impressive manhood. The song opens the film but it is reprised again later when Painless, after a bout of impotence, becomes convinced that he may carry some latent homosexuality and even though he's never had any form of gay sex, he figures it's just a matter of time so he goes to Hawkeye for help for a way out. A last supper is arranged, where Painless will take the Black Capsule and commit suicide. Of course, Hawkeye has no intention of helping Painless to kill himself but instead enlists Lt. Dish (Jo Ann Pflug) to sleep with the unconscious Painless and restore his confidence. It works. There even is an instrumental, heavenly choir version of "Suicide Is Painless" to accompany the scene.Since MASH may well be the among the most plotless of Robert Altman's works (at least of the successful ones), I figured my appreciation of the film should be equally aimless, but I still had a few more things to say

and I've run out of stanzas to the song, so I'll just go with them. I love Altman's use of sound, already coming to life here, but particularly in the fun loudspeaker announcements. My personal favorite: the announcement that the American Medical Association had classified marijuana as a dangerous drug, despite previous studies that had found it no more harmful than alcohol. Also, it's worth noting that MASH did garner many Oscar nominations but in a tumultuous year such as 1970, there was no way that the stodgy Academy would go with the subversive Korean War comedy that everyone knew was really about Vietnam. (The Oscar went with the rah-rah jingoism of Patton.) MASH did manage to win adapted screenplay, which was particularly sweet, because its writer was Ring Lardner Jr., one of the most infamous victims of the Hollywood blacklist. Though Robert Altman had made features prior to MASH, truly this is the film that started the Altman canon and career and began to create the legend the late director became.

and I've run out of stanzas to the song, so I'll just go with them. I love Altman's use of sound, already coming to life here, but particularly in the fun loudspeaker announcements. My personal favorite: the announcement that the American Medical Association had classified marijuana as a dangerous drug, despite previous studies that had found it no more harmful than alcohol. Also, it's worth noting that MASH did garner many Oscar nominations but in a tumultuous year such as 1970, there was no way that the stodgy Academy would go with the subversive Korean War comedy that everyone knew was really about Vietnam. (The Oscar went with the rah-rah jingoism of Patton.) MASH did manage to win adapted screenplay, which was particularly sweet, because its writer was Ring Lardner Jr., one of the most infamous victims of the Hollywood blacklist. Though Robert Altman had made features prior to MASH, truly this is the film that started the Altman canon and career and began to create the legend the late director became.Tweet

Labels: 70s, Alda, Altman, blacklist, Bud Cort, D. Sutherland, Duvall, Gelbart, Marx Brothers, Movie Tributes, Television

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, December 26, 2008

Careful what you wish for

By Edward Copeland

During the numerous interviews writer-director Rod Lurie has given promoting his movie Nothing But the Truth, he talks about how much he likes films (his own and others) that provoke thought and discussion once the movie is over. This proves deadly for his own film because the more you examine it in retrospect, the more it falls apart.

If Nothing But the Truth were an episode of Law & Order, it would inevitably carry the teaser "Ripped From the Headlines" in its previews. Based loosely on the outing of CIA agent Valerie Plame as retaliation for her husband's column disputing part of the Bush Administration's case for the Iraq war, Lurie's film focuses on the idea of reporters defending their sources, in this case Kate Beckinsale who, like the real-life Judith Miller, goes to jail to protect her source.

Lurie changes his story so much for the purpose of twists and to preserve its status as fiction that he ends up undermining his mission: the need for a federal shield law for journalists. From this point on in the review, to really go into detail about how he botches the job so badly, I'm going to have reveal pretty much every twist in the film, so this is your:

OK, you can't say you haven't been warned so now I'm delving into the plot in detail.

First, a brief primer on the real life Joe Wilson/Valerie Plame case, for those who have forgotten and for those who never knew. Joe Wilson was a former ambassador dispatched to check out claims that Saddam Hussein sought uranium from the African country of Niger. Wilson came back and reported there was nothing to back up the claims. The Bush Administration ignored his report and perpetuated the myth for their own ends anyway.

Later, Wilson wrote an op-ed piece in The New York Times saying that he found no proof of the claim. Soon after, it was revealed in a Robert Novak column that Wilson's wife was Valerie Plame, a CIA operative. The CIA demanded that the Justice Department launch an investigation since the outing of a CIA operative's identity is a crime. Patrick Fitzgerald was appointed special counsel and pursued the leak, not only to Novak but to a subsequent story in Time magazine and to Judith Miller, who ironically never even wrote about Valerie Plame but went to jail to protect her source.

In the version in Nothing But the Truth, there is an assassination attempt made on the president. The attack is used as a pretense for the U.S. to launch a war against Venezuela. A noted administration critic later writes an op-ed revealing that the administration had been given an intelligence report finding no link between Venezuela and the assassination attempt.

Reporter Rachel Armstrong (Kate Beckinsale) learns that the writer's wife is Erica Van Doren (Vera Farmiga), the CIA operative who filed the report on Venezuela. Rachel and her editors are excited when she nails down further confirmation and believe Rachel will win a Pulitzer Prize for her story.

Let's stop here to examine what's wrong with all of this to this point. Now, if Erica's buried report that her husband revealed in his article (without her permission, we learn) were the subject of Rachel's story, I see the scoop, but is it jaw-dropping journalism to write a story that a thorn in a president's side is married to a CIA agent? Further, since the CIA certainly was aware of who Erica was married to, wouldn't she have been in a shitload of trouble for letting her husband either accidentally or on purpose know the details of an intelligence report and publish it?

Soon, a special counsel (Matt Dillon) is appointed and the heat begins to be put on Rachel to cough up the name of her source. Her paper stands behind her, despite their weaselly counselor (Noah Wyle) and they secure a high-powered defense attorney (Alan Alda) for Rachel. Alda, in fact, pretty much plays the only sympathetic male character in the film.

Beckinsale and especially Farmiga are very good but part of that is because the deck is so unfairly stacked against everyone in the film with a y chromosome. Dillon is supposed to be part charmer, part barracuda, but he really only comes across as an asshole. Erica's husband, the Joe Wilson equivalent, barely has any lines and inexplicably leaves his wife and takes his daughter when the newspaper outs her.

David Schwimmer plays Rachel's novelist husband, who starts out as a good guy but turns adulterer soon after his wife goes to jail because he needs to get laid regularly, First Amendment be damned. What really requires a special counsel investigation is the disappearance and reappearance of Schwimmer's facial hair throughout the film.

Of course, the ultimate point of Lurie's film is that journalists should be able to protect their sources so they can keep government in check, etc. However, that is undermined by the final twist, when we learn who Rachel's first source was. See, Erica and Rachel's kids go to the same school, though their moms never knew each other. On a field trip, Erica's young daughter inadvertently reveals who her father is, that her parents argued over something to do with her work and that mom is a spy.

First, would a reporter go this far when her story was launched with the help of a grade school student? Second, the special prosecutor repeatedly says that any government official who outs a CIA agent has committed a crime. Wouldn't this all have been over quickly if Rachel had told him and the court her source was not a government official? Hell, why wouldn't she give up the kid? Was she afraid of being embarrassed? Did she hope to get more scoops out of the kid? (Perhaps give her the code name Deep SquarePants.) Did she think they'd try to send a kid to jail? How much taxpayer money was wasted on this silliness?

A really good movie should be made about the need for a federal shield law, but Lurie seemed more attracted to tricks than truth. Beckinsale is good and Farmiga is very good, buy they deserved a better vehicle.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Alda, Law and Order

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, December 22, 2008

Robert Mulligan (1925-2008)

By Edward Copeland

Robert Mulligan, who died Saturday at 83, was a solid workman-like director. Not all of his films were good or memorable by any means but the ones that were more than merit his inclusion among the best, if for To Kill a Mockingbird alone.

That movie version of Harper Lee's great novel remains one of the most faithful adaptations of a wonderful book ever brought to the big screen in Horton Foote's screenplay. Beyond that achievement was his astonishing work with the cast, bringing great performances out of the children, including an Oscar nomination for Mary Badham as Scout. He also elicited Gregory Peck's best work ever as the noble Atticus Finch and got Peck a deserved Oscar for the performance.

Mulligan, whose brother was the late actor Richard Mulligan of Soap and Empty Nest fame, got his directing start in 1950s live television before moving into film with such efforts as Fear Strikes Out starring Anthony Perkins and two Natalie Wood vehicles: Love with the Proper Stranger and Inside Daisy Clover.

In 1978, he directed a guilty pleasure of mine: Alan Alda and the great Ellen Burstyn in Same Time, Next Year, which even now, decades after I first saw it, if I catch it on TV, I have to watch it until the end. I can hear Johnny Mathis singing right now.

Fittingly, one of his best films was his last one and also featured another great performance by a youngster when he made The Man in the Moon starring a then-14-year-old Reese Witherspoon.

RIP Mr. Mulligan.

Tweet

Labels: Alda, Books, Burstyn, Fiction, Gregory Peck, Obituary, Richard Mulligan

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, March 28, 2007

Swear to tell the truth

By Edward Copeland

Everyone has them. Call them guilty pleasures or whatever else you want, but everyone has them: Movies you really like but that you feel you'd be ostracized or ridiculed for if your affection became common knowledge. Not today. We are all under oath, myself included, and it's time to give these films our due. It's not a time for mocking others. This is a time to come clean. Besides, if you are like me and insist on broadcasting your opinions to the entire world, you shouldn't hold some back for fear that you stand alone. That also goes for you, politicians. Opinions are subjective, so no opinion of something like a movie can be wrong. (Opinions on political issues can be wrong, but you should still stand by your opinions if you enter the political arena.) Still, I'm withholding the names of the handful of movies I've selected to mention until after the jump, just to be safe.

What prompted this little column was the habit of TNT of showing the same movie multiple times in a short period of time. Catching pieces frequently and remembering how much I love My Best Friend's Wedding. Then I anticipated what would happen if I wrote of my affection for the film and the fusillade of anti-Julia Roberts missiles that would start flying in my direction. I'm not ashamed to admit it: I'm a sucker for My Best Friend's Wedding. It gets me every time. Put aside your Julia prejudices out there for a moment: Can't just about all of you identify with a friendship that you wished could be more and been saddened when you realize that opportunity is about to be lost forever? Granted, most of us don't engage in some of the downright despicable things the unstable Julianne Potter (Roberts) does to try to sever Michael and Kimberly (Dermot Mulroney, Cameron Diaz) ahead of their wedding, but still you can identify with her.

On top of that, the film also is damn entertaining, thanks in no small part to Rupert Everett as Julianne's best gay friend George. He's not only there to provide plenty of laughs but to act as the voice of reason. In the film's climax as Michael chases an upset Kimberly and Julianne chases Michael, it's George who asks Julianne the crucial question, "Who's chasing you? Nobody. There's your answer." Then he's still there in time to shore up her lagging spirits post-wedding. As he tells her, "Maybe there won't be marriage, maybe there won't be sex, but by God there'll be dancing" and My Best Friend's Wedding is a film I never tire of taking a turn on the dance floor with.

Myra: Is it really that good?

Sidney: I'll tell you how good it is. Even a gifted director couldn't hurt it.

When I decided to expand this post beyond My Best Friend's Wedding, I thought I'd try to limit myself to one film per decade, but I'm skipping the aughts, the 1930s and the 1940s. My pick for the 1980s couldn't be more different from My Best Friend's Wedding. There isn't an ounce of sentiment in Deathtrap, but damn if it isn't fun.

I'll admit it, though it's probably not nice to say so, Christopher Reeve isn't very good in this movie, but Michael Caine, Dyan Cannon and Irene Worth more than make up for it. I can see how the twists upon twists upon twists might grow tiresome after awhile, but I think Sidney Lumet's version of Ira Levin's play proves infinitely more fun than Sleuth.

As we turn the clock back to the 1970s, my hidden joy returns to the land of schmaltz in the form of Same Time, Next Year. Even from my grade school years, this adaptation of the stage comedy was nearly a yearly ritual. Ellen Burstyn is great, even if the sudden shifts her character takes defy reason and she pretty much wipes the screen with Alan Alda. Still, the romance, the passage of time and the low-rent Neil Simon-esque comedy get me every time. Though, what I think really is the key to the spell this film casts on me is that damn sappy song: Johnny Mathis and Jane Olivor singing "The Last Time I Felt Like This" over montages of crucial events in each time period always gets to me. Plus, it was easy to win an elementary age kid over in the late 1970s when the last pivotal historical photo is one of C-3PO and R2-D2.

"And then they decide I'm supposed to get a smaller share, like I'm someone extra special stupid. Even if it is a democracy, in a democracy it don't matter how stupid you are, you still get an equal share."

Contributor Jeffrey has written at his blog Liverputty about The 90-Minute Rule, which essentially says that no comedy really should go past the hour-and-a-half mark, or it's pressing its luck. By and large, I agree, though there certainly are exceptions. The 40-Year-Old Virgin neared two hours and still managed to maintain itself. Still, though I know the length of It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World is comedic overkill, I'm still a softie when it comes to this movie. It's another film that I formed a bond with at an impressionable age that is difficult to break. That cast! It's absurd, it's too long and I still love it, especially for the priceless Ethel Merman, Jonathan Winters and Dick Shawn and for that insane ending with the fire engine's ladder. I used to recreate that in my younger days with Tonka trucks and Fisher-Price Adventure People, flinging them to various spots around my room. Just about any criticism that can be made about this film I know is right, but I still can't help it.

My final confession concerns another film that hooked me at an impressionable age and that's White Christmas. For years, I always heard people say that it wasn't as good as Holiday Inn, which introduced the classic yuletide tune first. Once I finally saw Holiday Inn, I couldn't believe anyone could ever say such a ludicrous thing. For one thing, the earlier film didn't have the tag-team comedy/matchmaking pairing of Danny Kaye and Vera-Ellen or the sardonic touch of Mary Wickes. Even more importantly, White Christmas doesn't contain a salute to Lincoln's birthday with Bing Crosby in blackface which would be appalling if you weren't so shocked by what you're seeing in the first place. White Christmas is just plain fun. I still laugh when Bing and Danny lip-sync to "Sisters."

Tweet

Labels: Alda, Burstyn, Caine, Julia Roberts, Lumet, Mary Wickes, Merman, Neil Simon

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Wednesday, January 24, 2007

Golden Delicious

By Josh R

Presenting….in person….that 4 foot 11 bundle of dynamite….Kristin Chenoweth!

For those of you who don’t live and breathe musical theater, that’s a shout-out to the character of Dainty June, the aggressively adorable triple-threat vaudevillian immortalized in the definitive backstage musical, better known as Gypsy. There’s more than a little of June’s pint-size blonde ambition and overweening eagerness to please in Ms. Chenoweth, the diminutive comic sprite jauntily plucking the fruit from the boughs of Gary Griffin’s revival of The Apple Tree for The Roundabout Theatre Company. The actual line from Gypsy states June’s height as being 5 foot 2, giving her a solid three inches on the adult woman who is strutting her way deliciously through a trilogy of roles from the stage of Broadway’s Studio 54 — but she has nothing on Chenoweth when it comes to measuring star quality.

Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick’s 1966 musical, the follow-up to their smash hit Fiddler on the Roof, was originally conceived as a vehicle for the actress/comedienne Barbara Harris. A distinctive performer with a penchant for offbeat characterization, the actress enlivened many a middling Broadway entry (including 1965’s On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, the vehicle that catapulted her to the rank of leading lady) with her signature blend of wide-eyed, slightly discombobulated flakiness and flat-out comic desperation — a combination that worked to delightfully disarming effect in material that made full use of her idiosyncratic charms. The Bock-Harnick offering, director Mike Nichols’ first project after having completed The Graduate, captured her at the peak of her powers, and marked a last hurrah of sorts — after winning a Tony Award for the performance, she set her sights west, embarking on a film career that included memorable turns in films as diverse as Hitchcock’s Family Plot, Altman’s Nashville and the original Freaky Friday. Her leading man in The Apple Tree, a then 30-year-old stage actor named Alan Alda, would go on to even greater heights — in a sly reference to the original production, he can be heard in the current revival as the (pre-recorded) voice of God.

The show is a featherweight if amusing concoction comprised of three one-act musicals presented as an anthology. The first, and by far the most successful of these pieces, is adapted from Mark Twain’s “The Diaries of Adam and Eve,” a satirical re-imagining of goings-on in the Garden of Eden. The second piece, “The Lady or the Tiger?”, comes from Frank Stockton’s open-ended fable about a barbarian princess whose jealous nature may cost her secret paramour his life. The third, “Passionella,” is a frothy '60s romp by Carnal Knowledge scribe Jules Pfeiffer about a dowdy female chimney sweep whose televised fairy godfather transforms her into a Marilyn Monroe-like sex goddess. All three pieces are linked together by the theme of temptation, and the eternal love triangle between Man, Woman and The Devil.

If the sketch-comedy nature of the material doesn’t exactly qualify it as a Broadway classic, it is nevertheless a pleasant diversion that furnishes its cast with plenty of room to preen and strut. Given that the show was essentially been conceived as a series of star turns for its leading lady, Ms. Chenoweth is the most prominent beneficiary. The actress's career trajectory has been swift — she won a Tony for her scene-stealing turn in 1999’s You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, and an additional nomination for the smash hit Wicked, which cemented her status as a bona fide Broadway star. The Apple Tree marks the first time I have seen her live on a Broadway stage — at a distance of three yards away, no less — and I’m starting to understand what all the fuss has been about. With her stubborn kewpie doll features and a chipmunk’s squeak that can shift effortlessly – and somewhat freakishly — into a full-bodied lyric soprano, Chenoweth is, in her own way, as distinctive and unique a presence as either Carol Channing or Gwen Verdon. Like those performers, she knows exactly what her strengths are, and exactly how to exploit them to maximum effect. She’s a curious creature — imagine if scientists crossbred Reese Witherspoon with a smurf — and like Ms. Witherspoon, whose brisk perkiness she undoubtedly shares, there is occasionally something a little self-congratulatory in the way she twinkles and beams to up the adorability quotient and denote how cute she knows she is. That quality, however, is just right for The Apple Tree, which sends up the diva theatric while at the same time holding it up for winking glorification. Chenoweth’s timing is, to borrow the title of previous stage hit, wicked, and her talent for slapstick is just as finely honed. Whether she’s gawking in giddy delight at the wonders of Eden, cracking the whip as a royal man-eater imperious and bitchy enough to make Joan Collins cower, goofing it up as a dumpy chimneysweep with Coke-bottle glasses and a bad haircut, or sashaying around the stage while marveling at her proportions as the voluptuous bombshell, she nails her target with laser-like precision each and every time.

As Mr. Copeland is fond to say of certain actors and performances, a little of Ms. Chenoweth does indeed go a long way. Happily basking in the light of her own comic ingenuity, she might be a bit too much to take if her co-stars weren’t able to measure up to her standard. When I first saw this version of The Apple Tree in an Encores! concert staging at The City Center in 2005, she dominated the evening a little too effortlessly, all but blowing the ingratiating Malcolm Gets and a rather colorless Michael Cerveris off the stage. Fortunately, the re-casting of the two major male players restores a sense of balance to the proceedings, and makes for a much more satisfying menage-a-trois. Brian D’Arcy James scores a personal triumph in the Alda roles, demonstrating a comic versatility which make his Fall 2007 assignment — slipping into Gene Wilder’s mad scientist garb in the Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein — a tantalizing prospect. He brings an unaffected everyman charm to his performance as Adam, re-imagining him as somewhat fatuous Average Joe whose pride is wounded easily each time Eve’s savvy shows him up. His earthiness nicely complements Chenoweth’s empyreal pixie quality, and the sincerity he brings to his final scene provides the evening with its one truly moving moment. As the barbarian warrior in "The Lady and the Tiger" sequence, he does a devastatingly dead-on impression of Charlton Heston, and his posturing folk-rocker in "Passionella," sort of a cross between Bob Dylan and Elvis Presley, becomes a deliriously funny riff on Bono (as D’Arcy James demonstrated in The Lieutenant of Inishmore, an Irish accent is right in his wheelhouse).