Friday, December 30, 2011

"I'm just glad I'm here where it's quiet…" — Straw Dogs Part I

its 40th anniversary Thursday. If you haven't seen it and plan to at some point, best not to read this.)

By Edward Copeland

When Sam Peckinpah's classic The Wild Bunch opened in 1969, its violence drew much controversy, though many critics saw past the bloodshed to recognize the movie's significance and greatness. Two years later, Peckinpah made Straw Dogs — and it received a near-universal greeting of pans, revulsion and diatribes that accused the film of being a one-dimensional attack on intellectuals and, even worse, an endorsement of the idea that rape victims "ask for it." Liking or disliking a movie always comes down to a person's subjective opinion and ideally — I believe anyway — that assessment should be formed by the artistry (or lack thereof) that's on the screen. When you read the reviews of Straw Dogs from 1971, that seldom seemed to be the case. In fact, many critics who despised the film praised Peckinpah's craft simultaneously. Straw Dogs became the victim of cinematic profiling, watched through the prism of real-world events. People projected views formed by outside experiences onto the movie and slammed it because of what they perceived it to be. There's always been a form of film criticism that chooses to judge movies in a political context and that's fine — it's a free country. However, that school of thought tries to apply that model to every movie, sometimes to the point of ridiculousness (I have good friends who believe that Forrest Gump somehow endorses Reaganism. I belong to the camp that believes if you don't think a film's good, just say so — a negative review need not be complicated with an ideological justification. A movie such as Thor sucks, but politics has nothing to do with why I formed that opinion.) I've went way off topic — this post salutes 1971's Straw Dogs. It's ironic, considering the film's title originated as a variation of the term "straw man," roughly defined as a mediocre argument or idea put out so it can be defeated by a better one. Over the decades, more have recognized the major misinterpretation that Straw Dogs received upon release. Its 40th anniversary offers an ideal opportunity for reassessment and analysis of the film as the complex, layered thriller that I believe Peckinpah made in the first place.

While I'm too young to have seen 1971's films in first run, knowing much of the history, events and certainly the movies that year, violence definitely dominated news and entertainment. Vietnam remained front and center as the South, backed by the U.S., invaded Laos and Cambodia while the war's unpopularity grew with larger protest marches (half-a-million people at one in D.C.) and bigger majorities in polls opposing it (60% in a Harris Poll); according to FBI statistics for 1971, the U.S. murder rate jumped to 8.6 people out of every 100,000, continuing the nonstop rise that began in 1964. Stats also showed that about 816,500 were victims of violent crime and there were 46,850 reports of forcible rape — a crime that often goes unreported which it did then more than it does now; Charles Manson and his followers were convicted and sentenced to death in the Tate-LaBianca murders, though a temporary repeal of capital punishment by the California Supreme Court the following year reverted the sentences to life; Wars were taking place beyond Vietnam. East Pakistan fought Pakistan for liberation, eventually becoming Bangladesh. Later, East Pakistan got into a skirmish with India, but the new country quickly surrendered. another "war" began in the U.S. that still continues when Nixon declared the "war on drugs"; Riots weren't uncommon in the U.S., including one in Camden, N.J., that began after police beat a Puerto Rican motorist to death. A more famous riot occurred at the Attica Correctional Facility in New York when nearly half of the more

than 2,000 inmates seized the prison, taking 33 staff hostages for four days until New York state police retook it. At least 39 people were killed, including 10 hostages; It also was the era of frequent airplane hijackings. Though not a violent one, it was the year the infamous D.B. Cooper got his money and parachuted into oblivion; Coups, usually of the military type, brought down the governments in Turkey, Sudan, Thailand, Bolivia and Uganda, which brought to power Idi Amin. That's not counting the coups that failed. That's just a cursory glance at what an uneasy world it was in 1971. Flowing into this situation were many, many movies, some that played on that fear, others that allowed for a release of that feeling of impotence. A few of the more high-profile examples:

than 2,000 inmates seized the prison, taking 33 staff hostages for four days until New York state police retook it. At least 39 people were killed, including 10 hostages; It also was the era of frequent airplane hijackings. Though not a violent one, it was the year the infamous D.B. Cooper got his money and parachuted into oblivion; Coups, usually of the military type, brought down the governments in Turkey, Sudan, Thailand, Bolivia and Uganda, which brought to power Idi Amin. That's not counting the coups that failed. That's just a cursory glance at what an uneasy world it was in 1971. Flowing into this situation were many, many movies, some that played on that fear, others that allowed for a release of that feeling of impotence. A few of the more high-profile examples:One of my all-time favorite critics is Pauline Kael, though I disagreed with her often, but she was completely off-base in what she wrote about Straw Dogs. I've compiled some of the key things she wrote in her New Yorker review of the film:

"Peckinpah's view of human experience seems to be no more than the sort of anecdote that drunks tell in bars."…"The actors are not allowed their usual freedom to become characters, because they're pawns in the overall scheme."…"The preparations are not in themselves pleasurable; the atmosphere is ominous and oppressive, but you're drawn in and you're held, because you can feel that it is building purposefully."…"The setting, the music and the people are deliberately disquieting. It is a thriller — a machine headed for destruction."…"What I am saying, I fear, is that Sam Peckinpah, who is an artist, has with Straw Dogs, made the first American film that is a fascist work of art."

While Kael mostly missed the mark, she came so close to acknowledging that she did see what Peckinpah's intentions were and that they were artistic ones, that it's almost sad. Let's look at those sentences separately. "Peckinpah's view of human experience seems to be no more than the sort of anecdote that drunks tell in bars." Mainly, that's Pauline doing what she loved to do best (and I admit I can be guilty of succumbing to myself) — thinking up a funny sentence and using it. In relation to Straw Dogs, Kael either was blinded by other factors as to what was on the screen or she refused to acknowledge that the story being told had more layers and complexity than a mere anecdote. I'll flesh out my rebuttal on that later. "The actors are not allowed their usual freedom to become characters, because they're pawns in the overall scheme." She's absolutely right here, but she's also being dishonest because as avid a moviegoer as she was she knew that not every film acts as a character study full of finely drawn portraits of the people inside. The woman who routinely answered the question, "What's your favorite film?" with 1932's Million Dollar Legs starring Jack Oakie and W.C. Fields isn't looking for that in every type of movie, especially a genre film and Straw Dogs belongs in the thriller family, albeit one with depth, intelligence and things to say. "The preparations are not in themselves pleasurable; the atmosphere is ominous and oppressive, but you're drawn in and you're held, because you can feel that it is building purposefully." Kael contradicts herself in the same sentence. All movies aren't designed to be pleasure rides, but they still can be enriching. It's the scenario I always posit among friends: You've gathered for a fun evening and you feel like watching Spielberg. What do you put in the DVD player — Jaws or Schindler's List? Just because you settle on Jaws doesn't mean that Schindler's isn't good, it's just not the type of movie you watch for a rollicking good time. The contradiction comes when she

describes the atmosphere as "ominous," which would seem perfectly natural for a thriller and then admitting it held her attention because she could tell it was building toward something with a purpose. As I said, she was so close. That's exactly what Peckinpah was doing and did. "The setting, the music and the people are deliberately disquieting. It is a thriller — a machine headed for destruction." Finally, Pauline acknowledges that Straw Dogs is a thriller and within those two sentences, she doesn't say anything that indicates she thinks Peckinpah violated the rules of a thriller. The last sentence of Kael's that I excerpted shows where she hopped onboard a train to crazytown. "What I am saying, I fear, is that Sam Peckinpah, who is an artist, has with Straw Dogs, made the first American film that is a fascist work of art." Again, she admits Peckinpah's artistry but she claims he has used that gift to make a "fascist work of art." No wonder she prefaced that with "I fear" because one gift Kael always had, even when you disagreed with her (other than great writing skills) is that she made you re-think your opinion. She didn't necessarily change your mind, but she gave you ideas to mull. Her Straw Dogs review provides a rare example where I didn't believe that she believed the words she placed in print. Her review reads as if she wanted Straw Dogs perceived simply as a macho appeal to give in to our violent nature and a screed against intellectuals. That's what she wanted to see, but her heart and her brain seem to be having a wrestling match for control over her writing. The adjective fascist got bandied about a lot in reviews of Straw Dogs. I can see how some slapped that label onto Dirty Harry, even if I think that was an overreaction as well, because Dirty Harry carries political overtones and a point-of-view, but, as I said before, I believe films should be reviewed as films and ideology should stay out of it. What does it say then that a true fascist film such as Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will is a staple of film studies not because of content but technique? The adjective fascist should appear if a character in the movie has fascist characteristics or is a fascist, but to label a movie one — to me that's nearly as offensive as when Tipper Gore, James Baker's wife and the rest of the PMRC wanted to interpret what songs meant in the 1980s and institute stringent record labeling. As Frank Zappa said about their plans at the time, "It's like treating dandruff with decapitation." It also reminds me of what Jon Stewart said about politicians of both parties comparing opponents to Hitler. By doing that, they do a disservice to Hitler, he said, "who worked long and hard to be that evil." With that out of the way, it's high time I start talking about what actually happens in Straw Dogs. Before I do, I will say this: a bit of a pass can be given to Kael and other critics who shared her opinion and lay siege to Straw Dogs for all its perceived sins since the version that they saw wasn't the one I did. Peckinpah had to cut footage to avoid an X rating but on home media, they restored that scene. Granted, it might have elicited the same reaction, but the fact remains that when I saw Straw Dogs the first time, I literally didn't see the same cut that the critics of 1971 did — and the scene excised in 1971 got removed from the film's most controversial and debated scene, leaving only the ambiguous sexual assault that seems to turn consensual and omitting the second thug who undeniably commits rape.

describes the atmosphere as "ominous," which would seem perfectly natural for a thriller and then admitting it held her attention because she could tell it was building toward something with a purpose. As I said, she was so close. That's exactly what Peckinpah was doing and did. "The setting, the music and the people are deliberately disquieting. It is a thriller — a machine headed for destruction." Finally, Pauline acknowledges that Straw Dogs is a thriller and within those two sentences, she doesn't say anything that indicates she thinks Peckinpah violated the rules of a thriller. The last sentence of Kael's that I excerpted shows where she hopped onboard a train to crazytown. "What I am saying, I fear, is that Sam Peckinpah, who is an artist, has with Straw Dogs, made the first American film that is a fascist work of art." Again, she admits Peckinpah's artistry but she claims he has used that gift to make a "fascist work of art." No wonder she prefaced that with "I fear" because one gift Kael always had, even when you disagreed with her (other than great writing skills) is that she made you re-think your opinion. She didn't necessarily change your mind, but she gave you ideas to mull. Her Straw Dogs review provides a rare example where I didn't believe that she believed the words she placed in print. Her review reads as if she wanted Straw Dogs perceived simply as a macho appeal to give in to our violent nature and a screed against intellectuals. That's what she wanted to see, but her heart and her brain seem to be having a wrestling match for control over her writing. The adjective fascist got bandied about a lot in reviews of Straw Dogs. I can see how some slapped that label onto Dirty Harry, even if I think that was an overreaction as well, because Dirty Harry carries political overtones and a point-of-view, but, as I said before, I believe films should be reviewed as films and ideology should stay out of it. What does it say then that a true fascist film such as Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will is a staple of film studies not because of content but technique? The adjective fascist should appear if a character in the movie has fascist characteristics or is a fascist, but to label a movie one — to me that's nearly as offensive as when Tipper Gore, James Baker's wife and the rest of the PMRC wanted to interpret what songs meant in the 1980s and institute stringent record labeling. As Frank Zappa said about their plans at the time, "It's like treating dandruff with decapitation." It also reminds me of what Jon Stewart said about politicians of both parties comparing opponents to Hitler. By doing that, they do a disservice to Hitler, he said, "who worked long and hard to be that evil." With that out of the way, it's high time I start talking about what actually happens in Straw Dogs. Before I do, I will say this: a bit of a pass can be given to Kael and other critics who shared her opinion and lay siege to Straw Dogs for all its perceived sins since the version that they saw wasn't the one I did. Peckinpah had to cut footage to avoid an X rating but on home media, they restored that scene. Granted, it might have elicited the same reaction, but the fact remains that when I saw Straw Dogs the first time, I literally didn't see the same cut that the critics of 1971 did — and the scene excised in 1971 got removed from the film's most controversial and debated scene, leaving only the ambiguous sexual assault that seems to turn consensual and omitting the second thug who undeniably commits rape.

The opening credits always remind me of parts of the beginning of The Wild Bunch, the titles themselves specifically naming that film's actors in semi-black-and-white (or more accurately, black-and-gray) freezes while they're on horseback. No actors lurk beneath the monochrome credits of Straw Dogs — where we first hear Fielding's foreboding score — but beneath the title cards, blurry images recall the ants overrunning the scorpion at the start of The Wild Bunch. When the picture comes into focus and color, we see that what's scurrying isn't insects but children, singing, dancing and playing with abandon — in a graveyard. Three of the youngsters circle a dog, which some interpret as torture. As someone who despises mistreatment of animals (I always say I've been screwed over by humans far more often than by dogs), it doesn't look that way to me. A few of the kids gaze through the cemetery fence at the activities in the center of the small Cornish village in England. American David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman) walks back toward his car carrying a box of supplies he's picked up while his wife Amy (Susan George), a native of the village, attracts leers as she struts down the street sans bra.

That shot, coming so early in the film, certainly had a lot to do with putting some of the critics in 1971 such as Kael on edge. She admits in her review that part of her reaction to the film probably stemmed from being a woman and if Peckinpah had placed that image of an extreme close-up of the actress's breasts with erect nipples for no apparent reason and it wasn't brought up again, I'd have been offended as well. When I first saw Straw Dogs, the shot took me aback. That looked like something you'd find in a cheap teen sex comedy in the wee hours of the morning on Cinemax, not in a Sam Peckinpah film starring Dustin Hoffman. Eventually though, it is discussed and you see the purpose — and it's not to say "some women want to be raped." We'll get to that later. I'll finish describing the opening sequence first. The teen Hedden siblings, Bobby and Janice (Lem Jones, Sally Thomsett), help Amy by carrying an antique mantrap that she purchased to her car. Charlie Venner (Del Henney) steps out of a phone booth when he catches sight of Amy. He dated Amy when she lived in the town with her father and the sight of her makes Venner salivate. In this very first sequence, Peckinpah and his editing team of Paul Davies, Tony Lawson (who'd go on to edit Kubrick's Barry Lyndon and every Neil Jordan film since Michael Collins) and Roger Spottiswoode (who also edited Peckinpah's Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid before turning to directing) set the quick-cut pattern that will dominate the movie. The director, stereotyped for slow-motion violence, paces much of Straw Dogs with split-second snapshots. Venner makes a beeline for David and Amy's car where Amy introduces Charlie to her husband. David puzzles over the mantrap that Amy bought and tries to place it in the backseat of the car with Bobby's help. David then tells Amy he's going to run into the pub to buy some cigarettes and David leaves her with Charlie, who shamelessly flirts with Amy and tries to get her to re-create old times.

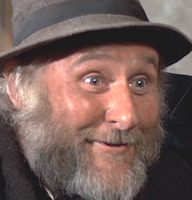

When David steps into the pub, he definitely feels and looks out of place — but it's not because he's wearing a sign that reads BRILLIANT MATHEMATICIAN STUDYING THEORIES YOU PEOPLE COULD NEVER COMPREHEND. No, his clothing, his look, his voice — they all point him out as someone who doesn't hail from that Cornish village as he asks for "Two packs of American cigarettes." However, no one taunts him or mocks him — they have a bigger troublemaker to deal with, one of their own. The burly, bearded Tom Hedden (Peter Vaughan), father to Bobby and Janice and the town drunk, somehow manages to maintain a degree of respect from those younger than him. As David has entered for his smokes, Tom wants another round after

the pub's owner, Harry Ware (Robert Keegan), announces closing time for the afternoon. Tom slams his mug down, breaking it and cutting Harry's finger. As David witnesses this, Charlie enters the pub and asks how the work on David and Amy's garage is progressing. David complains that the two men working on it seem to be dragging their feet and Charlie volunteers to come up the next day with his cousin to help them pick up the pace. Sitting quietly in the pub, observing everything, happens to be the town's magistrate, Maj. John Scott (T.J. McKenna). Tom isn't going to take no for an answer, so he flips up the opening to the bar and serves himself. Scott warns Tom that he's had his fun, but he best be off or he'll have to bring charges and Charlie and another man help the drunkard out, but not before he apologizes to Harry and leaves money for the damage as well as David's cigarettes. Vaughan plays Tom well, straddling that line between charming old lush and frightening bastard. After they've left, David gives Harry the money for the cigarettes. The pub's owner tells him he's already been paid. "You have now," David says before leaving. Most of the actor's work has been in British television productions, though he did appear in Time Bandits and Brazil for Terry Gilliam and the HBO series Game of Thrones.

the pub's owner, Harry Ware (Robert Keegan), announces closing time for the afternoon. Tom slams his mug down, breaking it and cutting Harry's finger. As David witnesses this, Charlie enters the pub and asks how the work on David and Amy's garage is progressing. David complains that the two men working on it seem to be dragging their feet and Charlie volunteers to come up the next day with his cousin to help them pick up the pace. Sitting quietly in the pub, observing everything, happens to be the town's magistrate, Maj. John Scott (T.J. McKenna). Tom isn't going to take no for an answer, so he flips up the opening to the bar and serves himself. Scott warns Tom that he's had his fun, but he best be off or he'll have to bring charges and Charlie and another man help the drunkard out, but not before he apologizes to Harry and leaves money for the damage as well as David's cigarettes. Vaughan plays Tom well, straddling that line between charming old lush and frightening bastard. After they've left, David gives Harry the money for the cigarettes. The pub's owner tells him he's already been paid. "You have now," David says before leaving. Most of the actor's work has been in British television productions, though he did appear in Time Bandits and Brazil for Terry Gilliam and the HBO series Game of Thrones.

It takes a bit of a drive to get to Amy and David's farmhouse and since she's driving, Amy takes her husband on a fast and wild ride to get there, partly as punishment for his queries about her past with Charlie Venner. Before they get to the farm, Amy finally admits that years ago when she lived there, Charlie made a pass at her. David and Amy appear a rather unlikely couple, but in rare moments like this or when they're getting romantic, the two do show signs of sexual compatibility. In other instances, not so much. The screenplay by

Peckinpah and David Zelag Goodman, based on the novel The Siege of Trencher's Farm by Gordon M. Williams, makes a point of showing that David doesn't respect Amy intellectually and, more than likely, views her as a sex object as much as the leering village thugs do. When the couple arrive at the farm, one of the two workers, Norman Scutt (Ken Hutchison) stands at attention on top of the garage. Amy makes a point of making out with David in the car in full view of Norman, though you can tell it makes her husband uncomfortable. The Sumners get out of the convertible and head separate directions — Amy to the house, David to inform Scutt of his incoming help. When David tells Scutt that Venner and his cousin will be arriving the next day to help him pick up the pace on the garage project, Scutt tells him that he and Mr. Cawsey don't have that much more to do. The name doesn't ring a bell with David, but Amy bumps into Mr. Chris Cawsey (Jim Norton) inside the farmhouse. When Cawsey steps outside, David remembers, "The rat man!" Cawsey helps Scutt on the garage, but his main skill involves exterminating rodents. Scutt asks David if he needs help unloading the mantrap (which really should be referred to as "Chekhov's mantrap" since you know its antique metal teeth shall clamp down on someone before the movie ends) and he gladly accepts. Cawsey explains that the mantraps were set them out in the field to catch poachers. As the three men stand alone outside, Straw Dogs comes as close as it ever will to explicitly discussing current world events occurring in 1971.

Peckinpah and David Zelag Goodman, based on the novel The Siege of Trencher's Farm by Gordon M. Williams, makes a point of showing that David doesn't respect Amy intellectually and, more than likely, views her as a sex object as much as the leering village thugs do. When the couple arrive at the farm, one of the two workers, Norman Scutt (Ken Hutchison) stands at attention on top of the garage. Amy makes a point of making out with David in the car in full view of Norman, though you can tell it makes her husband uncomfortable. The Sumners get out of the convertible and head separate directions — Amy to the house, David to inform Scutt of his incoming help. When David tells Scutt that Venner and his cousin will be arriving the next day to help him pick up the pace on the garage project, Scutt tells him that he and Mr. Cawsey don't have that much more to do. The name doesn't ring a bell with David, but Amy bumps into Mr. Chris Cawsey (Jim Norton) inside the farmhouse. When Cawsey steps outside, David remembers, "The rat man!" Cawsey helps Scutt on the garage, but his main skill involves exterminating rodents. Scutt asks David if he needs help unloading the mantrap (which really should be referred to as "Chekhov's mantrap" since you know its antique metal teeth shall clamp down on someone before the movie ends) and he gladly accepts. Cawsey explains that the mantraps were set them out in the field to catch poachers. As the three men stand alone outside, Straw Dogs comes as close as it ever will to explicitly discussing current world events occurring in 1971.NORMAN: I hear it's pretty rough in the States.

CHRIS: Have you seen any of it, sir? Bombing, rioting, sniping, shooting the blacks. I hear it isn't safe to walk the streets, Norman.

NORMAN: Was you involved in it, sir? I mean, did you take part?

CHRIS: See anybody get knifed?

DAVID: Only between commercials. (after some talk concerning the mantrap) No, I'm just glad I'm here where it's quiet and you can breathe air that's clean and drink water that doesn't have to come out of a bottle.

David meekly flashes a peace sign and goes inside where Amy calls for the pet cat, who is nowhere to be found. Though the scene has moved inside, we hear the first line of dialogue between Cawsey and Scutt in the yard. Cawsey asks Scutt if he plans to "have a crack" at

Amy. "Ten months inside" were enough for him," Norman replies, apparently referring to jail time. He then inquires if Cawsey saw anything in the house worth stealing and Chris answers no except for one item. He then twirls a pair of panties around his finger. Scutt calls him an idiot, but Cawsey assures him she has plenty and won't notice. "Don't you want my trophy?" Cawsey asks. Scutt says he'd rather have what goes in them. Cawsey tells him that Charlie Venner had a go at her when she lived there with her father and Scutt gets testy. "Venner's a bloody liar and so are you." Tensions in the house simmer more subtly. Amy continues her search for the cat and David mutters, "I'll kill her if she's in my study." Amy inquires as to what he said, pretending she didn't hear, but he doesn't repeat it, but she obviously did because she changes a plus sign in the equation on his study's blackboard to a minus sign. Later, Amy comes and annoys David in his study while he's trying to work. Finally getting the hint, she leaves, though David gazes out the window and sees she's laughing with Scutt and Cawsey who just sit on a wall, not working. She warns them that David will think that they're lazy.

Amy. "Ten months inside" were enough for him," Norman replies, apparently referring to jail time. He then inquires if Cawsey saw anything in the house worth stealing and Chris answers no except for one item. He then twirls a pair of panties around his finger. Scutt calls him an idiot, but Cawsey assures him she has plenty and won't notice. "Don't you want my trophy?" Cawsey asks. Scutt says he'd rather have what goes in them. Cawsey tells him that Charlie Venner had a go at her when she lived there with her father and Scutt gets testy. "Venner's a bloody liar and so are you." Tensions in the house simmer more subtly. Amy continues her search for the cat and David mutters, "I'll kill her if she's in my study." Amy inquires as to what he said, pretending she didn't hear, but he doesn't repeat it, but she obviously did because she changes a plus sign in the equation on his study's blackboard to a minus sign. Later, Amy comes and annoys David in his study while he's trying to work. Finally getting the hint, she leaves, though David gazes out the window and sees she's laughing with Scutt and Cawsey who just sit on a wall, not working. She warns them that David will think that they're lazy.

When she returns to the study, he asks what the three of them found so funny. "They think you are strange," Amy tells him. "Do you think I'm strange?" David inquires of his wife. "Occasionally," she replies. He says she's acting like she's 14, which prompts her to chomp her gum louder, and he lowers her age to 12. "Want to try for 8?" She leaves him alone to his work, though later she calls to him that she needs some lettuce to prepare dinner. David gets up to fetch some from their tiny greenhouse when he notices the change on the chalkboard. "She's playing games now? What is this — grammar school?" he mumbles as he corrects the equation. When he gets to the greenhouse, Norman Scutt informs him that Riddaway (Donald Webster) has arrived to take he and Cawsey home. Cawsey stops by to share some odd little information with David. "I feel closer to rats than to people, even though I have to kill them to make a living. Their dying is my living," Cawsey declares as he climbs into Riddaway's truck and sings a little ditty, "Smell a rat, see a rat, kill a rat/That's me — Chris Cawsey/I'd be lost without em, I suppose/Cleverest thing I've seen around these parts is a rat." Later, Amy beckons David for dinner, but he seems peeved at being dragged from his work again.

A short scene in the pub gets inserted as night falls and a man comes in. Tom Hedden calls to the man, identifying him as John Niles (Peter Arne). He tells him that his brother Henry has been seen around young girls again and he better watch him or they'll have him put away. Tom's oldest son, Bertie (Michael Mundell), says that Henry only was tossing the ball to them, earning an icy stare from his father. John promises that if Henry starts to make any mistake "like he did before" he'll put him away himself. "If you don't, I will," Norman Scutt speaks up. When Henry shows up later in the film, he will be played by an unbilled David Warner in a part that's a million miles removed from his role in the previous Peckinpah film, The Ballad of Cable Hogue.

All of the major players have been mentioned or introduced and for the first time, I'm having to split the tribute to a single film in half. I don't have anything else ready to run anyway. For Part II, click here.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Books, Caine, David Warner, Dustin Hoffman, Eastwood, Fiction, Fields, Hackman, HBO, Heston, Kael, Kubrick, Movie Tributes, Oscars, Peckinpah, Spielberg, Tarantino, Terry Gilliam

Comments:

<< Home

I'm British and have to say that 'Straw Dogs' is a pretty racist American film, based on US ideas of superiority... "American cigarettes"!!!

Archibald Knox

Post a Comment

Archibald Knox

<< Home