Tuesday, November 21, 2006

A Less Than Singular Sensation

“She walks into a room and you know she’s uncommonly rare, very unique, peripatetic, poetic and chic…”

By Josh R

This lyric from the song “One,” penned by Edward Kleban, might well be used to describe the reaction which greeted the 1975 off-Broadway premiere of A Chorus Line. Hailed by critics of the day as an instant classic, it quickly transferred to the Shubert Theater on Broadway, where it ran and ran and ran, amassing an incredible total of 6,137 performances before hanging up its well-worn taps and fraying ballet slippers in 1990. Its storied run ensured its status as the most successful American musical of all time, although its tally was eventually eclipsed by some frolicsome felines and a disfigured opera buff imported from Great Britain (the less said about that, the better). Thirty years after its initial premiere, A Chorus Line is back on Broadway in a sleek new production helmed by Bob Avian, who co-directed the original version with Michael Bennett. While offering fleeting indications of what made the original a self-described Singular Sensation and cultural touchstone, this new incarnation ultimately falls short of duplicating that effect.

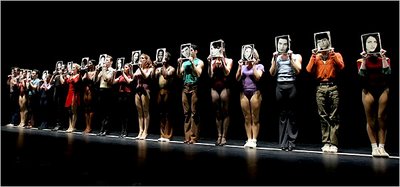

It’s still peripatetic, to be sure — the Bennett choreography, recreated by original cast member Baayork Lee (Bennett's longtime assistant), is among the very best to be seen on Broadway in this or any season, and the chic factor provided by the show’s bold concept still retains much of its galvanizing punch. In a certain respect it achieves a simple kind of poetry, thanks to the well-crafted lyrics of the late Mr. Kleban and the kinetic pop rhythms of Marvin Hamlisch. As to the qualities prescribed by the remainder of the lyric, uncommonly rare and very unique ... well, three out of five ain’t bad. When this lady walks into the room, even if you haven’t seen her before, you may very well wind up feeling as though you have. A Chorus Line can still strut its high-kicking stuff as well as any show in town, with dancers who can fly through the air with the greatest of ease — but apart from a few moments, the production as whole remains disappointingly earthbound.

If my disappointment seems more pronounced than it would with just any other revival, it need be stated that A Chorus Line is not just any show. To understand how and why it remains among the most celebrated of all stage musicals, it’s worth noting how revolutionary it was for its time. Michael Bennett, arguably the most revered director-choreographer of his generation, gathered together several Broadway dancers to discuss their lives and experiences, both on and offstage, in a series of taped sessions over the course of several years. The show that emerged as a result was culled directly from their anecdotal testimony (litigation continues to this day as to who’s owed what in terms of royalties), creating a startlingly honest portrait of a community of working professionals who practiced their trade not as stars, but as background players. The show introduced an element of realism to the Broadway musical that had previously been absent — other shows that had diverged from the template of escapist entertainment, such as Fiddler on the Roof, Hair and Company, had always seemed to favor a theatrical style based in a heightened, alternative reality. In chronicling an audition for a Broadway chorus that took place in a single afternoon in real time, A Chorus Line, with its pared-down look and naturalistic sound and feel, was a marked departure from what had come before.

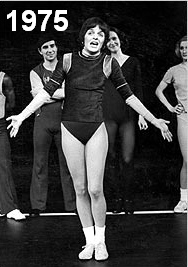

The expectations in 1975 were minimal at best — the show had no built-in commercial appeal to speak of, with no name-brand stars nor element of spectacle, and sexually frank subject matter that was hardly conducive to attracting family audiences and the tourist trade (it may have been the first hit musical to feature gay characters who existed outside the realm of comic caricature). The reviews were uniformly enthusiastic. While the off-Broadway run quickly sold out, the show was still not considered a likely candidate for mainstream success. Original cast member Robert LuPone later recalled that he knew it had struck some kind of deeper nerve when he looked out his dressing room window one night an hour before curtain and saw an endless line of limousines pulling up to the tiny downtown Public Theater, stretching for blocks and blocks as far as he could see. When, within a matter of weeks, the likes of John Lennon, Jackie O, Katharine Hepburn and Henry Kissinger could all be seen in attendance, it was clear that the show had taken on a life of its own in the media and beyond. The practice of ticket scalping may have actually been born out A Chorus Line’s success off-Broadway.

Does the show live up to its exalted reputation? Not entirely — it hasn’t aged nearly as well as Chicago, the Kander and Ebb musical that had the misfortune to make its Broadway bow in the same season as A Chorus Line and was more or less trampled in its wake (the irony here is that the current Broadway revival of Chicago stands a good chance of surpassing the original Chorus Line’s performance total). While A Chorus Line has many merits, not the least which are its outstanding score and choreography, you can’t help catching a whiff of mothballs in the air when the characters stop dancing and start talking. The retro attitudes of the script hardly derail the show, but they do make what once looked like a home run look more like what is, at best, a three-base hit. Still, the show still has the potential to deliver the goods — a potential that goes sadly unrealized for the most part at Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre.

I saw the original Chorus Line late into its run, so I can’t really testify as to what the effect may have been with the inaugural cast. However, it bears mentioning that, with few exceptions, all of the principal performers in the production that opened at the Public Theatre in 1975 were playing characters directly based on themselves — the bulk of the dialogue from the show had come verbatim from the taped sessions. This clever conceit lent an element

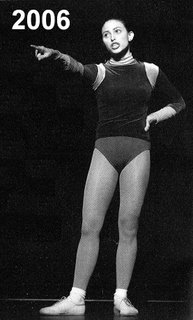

of authenticity to the proceedings that couldn’t have been faked. For the new mounting, Avian and Lee have in many cases chosen actors who sound (and often look) to a remarkable degree like their original counterparts — they’re a capable bunch, and entirely credible on their own terms, but at the same time, you’re aware that something is missing. When Natalie Cortez sings the wonderful ballad of comic frustration entitled “Nothing,” based on Tony-winner Priscilla Lopez’s wounding real-life experiences at Manhattan’s High School for the Performing Arts in the early 1960s, her delivery is assured and vocally precise. If it lacks the urgency of Lopez’s rendition, which can be heard in all its splendor on the 1976 recording, the fault can’t really be charged to Cortez. We can and should take Avian to task, however, for not encouraging his new discovery to put her own distinctive stamp on the material, rather than delivering a reasonable facsimile of the original version.

of authenticity to the proceedings that couldn’t have been faked. For the new mounting, Avian and Lee have in many cases chosen actors who sound (and often look) to a remarkable degree like their original counterparts — they’re a capable bunch, and entirely credible on their own terms, but at the same time, you’re aware that something is missing. When Natalie Cortez sings the wonderful ballad of comic frustration entitled “Nothing,” based on Tony-winner Priscilla Lopez’s wounding real-life experiences at Manhattan’s High School for the Performing Arts in the early 1960s, her delivery is assured and vocally precise. If it lacks the urgency of Lopez’s rendition, which can be heard in all its splendor on the 1976 recording, the fault can’t really be charged to Cortez. We can and should take Avian to task, however, for not encouraging his new discovery to put her own distinctive stamp on the material, rather than delivering a reasonable facsimile of the original version. That, in a nutshell, is the problem with this Chorus Line — in its slavish insistence on creating an exact replica of the original production, it more or less gives up the ghost as far as spontaneity is concerned. In addition to Avian and Lee, who recreate the Bennett staging right down to the poster poses, Robin Wagner and Theoni V. Aldredge have also been recruited to recreate (with minimal modification) their original sets and costumes. It’s an understandable impulse not to tamper with a winning formula, but it also indicates a certain lack of confidence in the material. It would have been a mistake to make a radical departure from the template by going in a completely different direction — Richard Attenborough’s misbegotten 1985 film version bore about as much relation to the world of Broadway musicals as a broadcast of Dance Party USA — but the anti-revisionist sentiment that fuels this production seems to have been motivated more by anxiety and trepidation than by any nobler impulse. Would contemporary audiences accept a modernized version of a piece that is, both in terms of style and execution, so specific to the 1970s? Avian’s solution is not just to treat the show as a period piece, but by maintaining it like some sort of holy shrine, its relics not to be disturbed a fraction of an inch. This is less objectionable than Gus Van Sant’s frame-by-frame reshooting of Psycho in terms of intention: this is, after all, the original creative team trying to preserve their work rather than a bunch of would-be mimics pirating someone else's vision — but their efforts only serve to make the material seem more dated than it otherwise would have. The only way this questionable strategy might have worked is if the show had been cast with performers who were charismatic enough to make the roles their own. As they are, these Broadway babies look right and sound right, but there’s no sense of genuine personality in evidence to make them come across as more than stock figures (This is a problem given that the entire point of the show is to bring human dimension to people who are traditionally written off as singing-and-dancing clones). Some of the best lines in the show belong to the acerbic Sheila — they were not the work of the show’s librettist, but came directly from the mouth of Kelly Bishop, the actress who eventually played the role in 1976 and won a Tony for her performance (as with Lopez, she was playing a character based on herself and essentially telling the audience her own life story). Deirdre Goodwin, who plays Sheila in this production, delivers the character’s dry putdowns and zingers with the requisite hauteur, but fails to make the character interesting — her behavior feels like so much empty posturing, and she commands less attention as a result. It doesn’t help if you know Bishop from her standout work on Gilmore Girls, playing a similarly caustic character — you can actually hear the actress’ natural inflections in the lines even while they’re being spoken by someone else.

The creators’ dilemma is understandable — realistically, they had no chance of recapturing the excitement of the original production, even if they had made more of an effort to bring something fresh to the proceedings. But the strategy of immaculate preservation ultimately does more harm than good — rather than living up to its billing as a Singular Sensation, this Chorus Line feels more like something off the assembly line.

Tweet

Labels: Ebb, K. Hepburn, Kander, Musicals, Theater, Van Sant