Thursday, August 08, 2013

Karen Black (1939-2013)

Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, Karen Black occupied a singular place in movies, hovering in that rarefied atmosphere that placed her somewhere between character actress and star. It landed her roles in many of the decade's classics as well as some of its silliness (such as Airport 1975) As the '80s came along, more of her work came on television and in low-budget horror films, but her early work kept her a recognizable name. Black died today at 74 after a battle with ampullary cancer diagnosed in 2010.

Born Karen Ziegler in Park Ridge, Ill., the actress attended Northwestern University before heading east and attending The Actors Studio with Lee Strasberg. She appeared in several off-Broadway plays and as an understudy in the 1961 comedy Take Her, She's Mine starring Art Carney before making her starring debut in 1965's The Playroom whose cast also included Bonnie Bedelia and Richard Thomas. Her second feature film made a mark for many people when she joined the cast of Francis Ford Coppola's 1966 comedy You're a Big Boy Now starring Elizabeth Hartman, Geraldine Page, Rip Torn and Tony Bill, among others. She made lots of episodic television appearances until she gained noticed in the small role of a hooker named Karen who drops acid in a cemetery with Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda in 1969's Easy Rider. Her counterculture journey continued the following year when she played the role of Rayette, the country-music loving waitress who becomes crazy in love with the alienated Robert Dupea (Jack Nicholson) in Bob Rafelson's Five Easy Pieces. The part earned Black her sole Oscar nomination as supporting actress.

Black teamed with Nicholson again the following year, only Nicholson sat in the director's chair as she starred opposite Bruce Dern in Drive, He Said. She soon followed that by assuming the part of the Claire Bloom surrogate Mary Jo Reid or The Monkey opposite Richard Benjamin in Ernest Lehman's adaptation of Philip Roth's comic novel Portnoy's Complaint. In 1974, she joined Zero Mostel when he brought his Tony-winning role from Eugene Ionesco's Rhinoceros to the big screen co-starring Gene Wilder. That same year she assumed the role of Tom Buchanan's mistress, Myrtle Wilson, in Jack Clayton's version of The Great Gatsby starring Robert Redford and Mia Farrow and the film won Black a Golden Globe for best supporting actress — and she did it in two dimensions! Finally, she completed 1974 by playing the scrappy stewardess trying to fly a crippled jumbo jet whose flight crew got taken out when a small plane crashed into its side in the funniest of the Airport movies, Airport 1975 (which I'll always love for having Gloria Swanson playing herself dictating her memoirs into a tape recorder as the plane is going down).

Black found herself busy again in 1975, beginning with the cult classic horror film Trilogy of Terror where she starred in three shorts all based on stories by the recent passed Richard Matheson. She also co-starred in John Schlesinger's film of the Nathanael West classic novella Day of the Locust. Her epic piece for that year though involved her first collaboration with Robert Altman in his masterpiece Nashville. Black played country superstar Connie White, filling the bill for another ailing star Barbara Jean (Ronee Blakeley), during events surrounding the political campaign of Replacement Party candidate Hal Philip Walker. In 1976, Black worked again with Nashville co-star Barbara Harris and frequent co-star Bruce Dern as well as William Devane to appear in what would be the final film of the Master of Suspense, Alfred Hitchcock's darkly funny tale of crooks, con men and kidnapping, Family Plot. In 1982, she returned to Broadway under Altman's direction as part of the ensemble of Come Back to the Five & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean. Altman's impossible-to-see film version featuring Black came out later that same year. Aside from some notable television appearances, most of her post-1982 career has been in horror and science fiction, but Karen Black delivered so much great work when her career was hot, she won't soon be forgotten. RIP Ms. Black.

Tweet

Labels: Altman, Awards, Coppola, Geraldine Page, Gloria Swanson, Hitchcock, Hopper, Mia Farrow, Nicholson, Obituary, Oscars, Redford, Rip Torn, Roth, Television, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, January 30, 2012

When radio was at its most beautiful

By Jonathan Pacheco

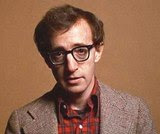

Roger Ebert once pointed out that Robert Altman kept track of time by the films he’d made. Similarly, I imagine the average cinephile has a mental timeline for his own life’s events based on the movies he’s seen and when he saw them. (I know that my first kiss came in late 1999 because it was with a girl I’d met earlier in the year through our mutual love for The Phantom Menace.) For the narrator of Radio Days (Woody Allen), childhood’s milestones are marked by memories of radio shows, newscasts and tunes.

As the film opens, he sets the scene of his youth — Rockaway Beach, N.Y., late 1930s — by first asking us to forgive him for his tendency to romanticize the past. Speaking of the rain-swept streets of his neighborhood, the overcast beaches a stone’s throw away and the peeling paint of the massive walls surrounding a nearby amusement park, he says, “I remember it that way because that was it at its most beautiful.” The same applies for the many personal memories he recounts throughout Radio Days, which turns 25 years old today.

Refreshingly, Woody leaves much of his trademark pessimism and sarcasm out of Radio Days, allowing Allen to spend less time trying to be funny and more time simply gushing with affection for Joe, his on-screen childhood persona (played by a young and tiny Seth Green), and his working-class family of parents, aunts, uncles and cousins all living beneath one roof. Sure, Joe’s mother (Julie Kavner) and father (Michael Tucker) still have their share of pointless fights typical of Allen’s autobiographical portrayals of his family life (arguing, for example, about which ocean is superior: the Pacific or the Atlantic), but there’s an endearment that still shows through the animosity, a sweetness that’s absent in some of his other films. In Radio Days, Allen depicts parents capable of simultaneously insulting and expressing love. After arguing in front of a radio relationship counselor and being told they “deserve each other,” the couple is taken aback, the mother saying, “I love him, but what did I do to deserve him?”

Sprinkled throughout the film are memories unadulterated by Allen’s wit or sarcasm, such as Joe’s remembrance of his parents’ anniversary, significant for being the only time he can recall them sharing a kiss. Or when he wakes up late one evening to find his aunt Bea (Dianne Wiest), permanently on an unsuccessful quest to find love, returning home with a date who, as she soon learns, still hasn’t recovered from the recent death of his fiancé, who also happened to be a man. Bea is crushed by this revelation, but she hides her emotions in favor of supporting a man still dealing with a lot of pain.

Allen ingeniously integrates stories of the actual radio personalities as tangential anecdotes to Joe’s childhood memories. His recollections of his family members’ favorite radio programs leads to memories of the programs themselves, leading to accounts of the personalities behind the microphones. Allen smartly resists the temptation to portray them as the “movie stars of their day,” instead depicting them as he imagined them as a child: earnest and sincere entertainers and newsmen, somehow already aware of how quickly their time in the spotlight will fade.

Having Joe’s family anchor the stories brings a cohesion to Radio Days’ many vignettes; no matter how far off topic the stories get, they all lead back to the core group, to the film’s heart. That’s why the subplot of Mia Farrow’s Sally White stands out as the film’s weakest element. It doesn’t really stem from the family’s experiences with radio the way the other stories do. Instead, the narrator’s recollections of Sally are presented as secondhand gossip, “insider” stories of how this aspiring radio star slept and lucked her way into the industry. Though her stories provide some vintage Woody Allen scenes (she escapes execution at the hands of a mob hit man when he discovers that they grew up in the same neighborhood in Brooklyn), they feel emotionally detached from Allen’s other wonderfully personal recollections.

In The Purple Rose of Cairo, Allen warns us of the dangers of escaping into the mediums we love, and in Midnight in Paris, he recognizes the folly of being too engrossed in the past. However, the director seems to have little desire in drawing any such lessons from Radio Days. In this film, he simply wants to hold on to his nostalgia, to cherish the highs and lows radio provided him. As Radio Days closes, our narrator worries that the ghosts of the radio era fade more and more with each passing year, but by making this film, Allen chooses not to let them go without a fight.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Altman, Ebert, Mia Farrow, Movie Tributes, Wiest, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

From the Vault: Husbands and Wives

Into every life a little rain must fall and in Husbands and Wives, Woody Allen summons a sizable storm. The inclement weather take many forms in Allen's new and much talked-about film and Rain (Juliette Lewis) is just one of the cloud formations in this documentary-style look at the aftermath of one couple's decision to split.

Jack and Sally (Sydney Pollack and Judy Davis) start a chain reaction when they tell their longtime friends Gabe and Judy (Allen and Mia Farrow) that, after 15 years of marriage, they plan to separate.

That announcement causes upheaval for all involved, forcing Jack and Sally to re-enter the singles scene and Gabe and Judy to re-evaluate their own relationship. Jack pursues a relationship with a New Age aerobics instructor (Lysette Anthony) while Sally gets fixed up with Judy's co-worker Michael (Liam Neeson).

Secretly, Judy pines for Michael herself while Gabe becomes attracted to one of his students at Columbia, the 20-year-old Rain who reminds him of a long lost love.

While similar to other Allen works, Husbands and Wives diverges from his usual path in terms of its language and, at times, its harsh, unblinking ugliness. The film chronicles these events not only by showing them but through conversations the characters conduct with an off-screen interviewer. The movie never explains this device and much of the film begs questions about the movie's intentions as well.

Allen films most of Husbands and Wives with a hand-held camera that darts around rooms like a camcorder being used for the first time by a technologically inept man after the birth of a grandchild. The desired effect doesn't quite work because instead of the jerky movements subliminally mimicking the chaos on screen, it simply distracts from the content.

While few screenwriters produce as much good dialogue as Allen and he's shown success at varying script structures, each time he embarks on something adventurous in terms of direction, it comes off more as a stunt than as the proper way to convey his story.

As usual, Allen wears his symbolism on his sleeve. He not only creates a lightning storm for a pivotal scene but makes a point of explaining its significance to the audience. When he delicately suggests that time is the true enemy of all relationships, Husbands and Wives works. Too often though he beats the audience over the head with his points. The subtle moments though work, especially those dealing with truths and half-truths that cause people to be uncertain of what they know.

Pollack delivers a solid performance as the blustery Jack who finds himself drowning in his own midlife crisis. Lewis fulfills much of the promise she displayed in Cape Fear as the tempestuous Rain, getting many of the film's best lines and scenes, especially in a sequence that visualizes what she thinks as she reads Gabe's unpublished novel.

Without question, the remarkable Judy Davis earns the prize for cast MVP as the hyper and aggressive Sally. She was robbed of Oscar nominations last year for solid supporting work in David Cronenberg's Naked Lunch and the Coens' Barton Fink and for her lead role in Impromptu, but hopefully this performance will garner a stream of awards.

As for Allen and Farrow, Woody is, as always, Woody, and Farrow, who has done her best work with Allen, comes off as somewhat sad and pitiful in a role that makes her unsympathetic. Given recent events in Allen and Farrow's real life, it's impossible not to read things into much of the dialogue and situations. Despite that, Husbands and Wives hits some universal nerves. Though it fails to live up to Allen's best works, it still deserves a look.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Coens, Cronenberg, Judy Davis, Liam Neeson, Mia Farrow, Oscars, Sydney Pollack, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, February 07, 2011

Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered

By Jonathan Pacheco

"God, she's beautiful," Elliot says, welcoming us into his months-long infatuation with his sister-in-law. Weak at the knees at just the smell of his wife's youngest sister, it won't be long before he indulges his pining and horniness. Misleadingly titled, Hannah and Her Sisters isn't really about Hannah (Mia Farrow), the rock of her wealthy, successful family and an overall supportive older sibling and wife. Rather, Woody Allen's 25 year-old film concerns itself more with Hannah's husband Elliot (Michael Caine), who can't take his lustful eyes off Lee (Barbara Hershey), his wife's intelligent, cultured, but willingly impressionable sister. Meanwhile, Holly (Dianne Wiest), a year removed from a coke addiction and suffering from a bad case of middle child syndrome, needs another loan from Hannah to fund her new catering venture, started to support her floundering acting career. And then there's Allen himself in the tonally contrasting role of Mickey, a TV producer, intense hypochondriac and Hannah's ex-husband.

Mickey's run-in with mortality seemingly has little to do with the film's other stories of marital dissatisfaction and sibling rivalry. A decidedly more "comedic" thread when compared to the subtler ones of Elliot, Lee and Holly, Mickey's arc, instead of throwing off the film's balance, somehow manages to counter the weight of the other three plots all by itself while keeping in line thematically, despite my instincts insisting on the contrary. That's because my initial perceptions of Hannah and Her Sisters, as with my initial assumptions about its title, were a bit off. Its biggest themes don't reside in the realms of marital strife or personal insecurities, but rather in the ideas of acceptance and inevitability — funnily enough, best represented in this film by Mickey's suddenly fitting story.

But before acceptance, these characters have the desperate desire to change who they are, where they're at, and where they're going. Other reviews and summaries will tell you that Elliot's decision to give up on his relationship with Hannah stems from his frustration with her self-sufficiency, but that's not quite the truth. Yes, Hannah is a strong, capable, independent character, and Elliot does indeed love the feeling of "teaching" and "molding" the younger Lee (much like Alvy sought to mold Annie in Annie Hall), but I don't think that drove him to have an affair. Men obsessed with the idea of being with another woman will find an excuse to be "driven away." They'll take a relationship issue that, under normal circumstances, would be "something to work on" — "she can be a bit clingy," "sometimes it's nice to feel needed," "I wish she'd show a little more physical affection" — and turn it into a dealbreaker — "you're suffocating me," "you're too perfect and self-sufficient, and I'm useless to you," "you're a cold, frigid woman!" When Elliot yells at Hannah for being too self-sufficient and too perfect, it sounds like a husband finding a crack in the marriage and trying to chisel his way out through it.

We see this character over and over in Allen's films (as recently as Josh Brolin's Roy in 2010's You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger). He's easy to spot, as he's typically combined with the iconic "neurotic Woody Allen" persona we hear about ad nauseum. However, the director has stated that he sees most every character as representing parts of himself, quite evidently in Hannah and Her Sisters. Mickey's paralyzing paranoia as well as Elliot's overpowering lustfulness and weakness of character are traits most commonly associated with Allen. But even in Lee we see his desire for sexual and intellectual stimulation and his thirst for culture (despite coming across as a simple "Marx Brothers and New York Knicks" kind of guy, we know that Allen's interest run somewhat deeper; he was inspired to write this film after a reading of Anna Karenina, and the film itself deliberately shows traces of Fanny and Alexander and Three Sisters). Holly embodies not only Allen's insecurities but his ability as a director to move from project to project, willing and sometimes desperate to try something different. When Holly thinks it a good idea to audition for a musical, I saw visions of Everyone Says I Love You.

Holly, to me, is the most interesting role of the bunch because her life revolves around not coming in first. She deals with the insecurities of being a middle child sandwiched between two "superior" women in almost every respect. Hannah has an angelic beauty, a marriage, a beautiful home, several kids, and even a successful acting career after an acclaimed stage turn as Nora in A Doll's House. Lee has youth, looks, intelligence, and a bright future. Meanwhile, Holly, not quite "the looker" that her sisters are, takes a sloppy-seconds flyer on Hannah's ex-husband Mickey, struggles from audition to audition, jumps from side-career to side-career and requires Hannah's financial help (which she's all-too-willing to provide) in every endeavor. Her partner in catering, April (Carrie Fisher), also is an actress and a friend to Holly — a friend who, like Hannah and Lee, seems to best her in every category. Notice the scene where David (Sam Waterston), a patron at a party Holly caters, comes back into the kitchen, raving about the food. Holly and April are intent on being clear regarding which dishes were created by them individually. The Holly-David-April love triangle continues in a painfully amusing game of one-upmanship as the two women vie for this architect's interest. The story of her life, Holly doesn't win that particular competition.

No, it's not until she accepts her "never first" lot in life that she finds peace and success. A failure at her first career choice, she discovers an interest and talent in writing, with Mickey wanting to produce her second script — not the one based on Elliot and Hannah's relationship, but the one based on her own life and experiences. Soon, she accepts the idea of a relationship with the man who wasn't good enough for her "superior" sister, and in it she finds happiness (and in turn, makes him happier than he ever was).

Before they can be at peace, all these characters must realize that their lives are not going to change into the different ones they want or envisioned. Embracing the lives they've already chosen (or have been given) is the key, in Woody Allen's mind. Elliot and Lee both have to realize that their affair always will be just an affair. Lee understands this first and moves onto another relationship. Elliot must also accept that Hannah is the wife he's chosen, and she never will be the dependent, impressionable "student" Lee is to her mates. Hannah's strong and capable...Is that such a bad thing? And Mickey's seemingly disconnected troubles, in this light, now fit perfectly into the film's thematic motif. His long struggle with mortality and existentialism ultimately leads him to accept that life may be meaningless, and it very well may be permanently over once you die. But if you choose to embrace the situation, well, there's a whole lot about life that still makes it worth living.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Barbara Hershey, Caine, Josh Brolin, Marx Brothers, Mia Farrow, Wiest, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, January 10, 2011

Peter Yates (1929-2011)

As a director, the Hampshire, England-born Peter Yates embraced a wide range of genres in the stories he brought to the silver screen, running the gamut from police thrillers to science fiction tales, from relationships dramas to beautifully rendered American slices of life, earning four Oscar nominations along the way, two for directing and two for producing. Yates has died at 81.

Though he began his career as an actor, Yates found his greatest fame behind the camera. He started doing second unit and assistant directing work on such notable films as Sons and Lovers, The Entertainer with Laurence Olivier, The Guns of Navarone and The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone. He made his feature directing debut in 1963 with Summer Holiday, a musical romance starring pop star Cliff Richard. The following year, he turned to comedy with a film called One Way Pendulum.

For much of the mid-1960s, he worked in television, directing episodes of The Saint starring Roger Moore and Secret Agent starring Patrick McGoohan.

He returned to features in 1967 with a dramatization of the Great Train Robbery called Robbery, but it was the film he made in 1968 that made his name: Bullitt. Starring Steve McQueen as a San Francisco cop, Bullitt still contains one of the famous chase scenes in movie history, thanks largely to the hilly environs of its setting.

His next film couldn't have been more of a departure. In John and Mary, Dustin Hoffman and Mia Farrow play two people who meet at a bar, have a one night stand and then spend the next day getting to know one another.

In 1971, he helmed Murphy's War where Peter O'Toole played the title character, the sole survivor of a ship attacked by a German U-boat during World War II who washes up on an island and plots how to take out the U-boat all by himself.

With Robert Redford as his lead, 1972's The Hot Rock took Yates into the heist genre. With a script by William Goldman adapted from a Donald Westlake novel, Redford gathers his crew to steal a big diamond from a museum at the behest of an African doctor who wants it returned to his homeland. The problem: Every time they get it, they keep losing the damn thing and having to steal it again.

Yates filmed a crime classic the following year when Robert Mitchum starred in The Friends of Eddie Coyle. The next year, Yates went in a completely different direction again with the Barbra Streisand comedy For Pete's Sake.

Comedy was still on his plate in 1976 with Mother, Jugs and Speed about the competition between private ambulance companies which brought together the unusual trio of Bill Cosby, Raquel Welch and Harvey Keitel. The next year, he submerged himself with the adaptation of Peter Benchley's thriller The Deep.

His next film though, at least as far as I'm concerned, will be his legacy and remains his best. It brought him those first two Oscar nominations as he filmed Steve Tesich's brilliant script Breaking Away, a film that is as great today as it was the first time I saw it, if not better. He even served as executive producer for the short-lived television series of the movie.

Even though Tesich wrote the screenplay for his next film, Eyewitness, and it starred William Hurt and Sigourney Weaver, the film was a better idea than a movie and bit of a letdown. However, nothing could prepare for his next release, the monumentally silly sci-fi monstrosity Krull in 1983.

Fortunately, he had another 1983 offering to get the taste of Krull out of one's mouth and it earned him those final two Oscar nominations. The Dresser really was an actor's movie (literally) more than anything else as it told the story of an aging and dotty Shakespearean actor (Albert Finney) and his dresser (Tom Courtenay) who more or less serves as his protector. Both Finney and Courtenay were nominated as well.

Following The Dresser, Yates made several films, but nothing to equal those from the early portions of his career. There was Eleni with Kate Nelligan, Suspect with Cher, The House on Carroll Street with Kelly McGillis and Jeff Daniels, the wretched An Innocent Man with Tom Selleck, Year of the Comet, Roommates with Peter Falk and D.B. Sweeney, The Run of the Country with Finney and Curtain Call with James Spader.

His final two projects were made-for-television adaptations of Don Quixote and A Separate Peace.

Even with some dogs on that resume, Yates produced a helluva body of work and an eclectic one at that with several titles that will last for generations.

RIP Mr. Yates.

Tweet

Labels: Dustin Hoffman, Falk, Finney, Jeff Daniels, Keitel, Mia Farrow, Mitchum, Musicals, O'Toole, Obituary, Olivier, Redford, Sigourney Weaver, Streisand, Television, William Hurt

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, November 28, 2010

From the Vault: Crimes and Misdemeanors

"Comedy is tragedy plus time," a character says in Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors which perfectly illustrates both dramatic subjects.

Crimes takes time to get into its rhythm, but the longer it goes on, the better it gets.

It has become almost a cliche to hear people complain about Woody's recent ventures into drama (September, Another Woman). They say, "We like his earlier, funny ones." They have missed the boat. Allen is as assured a writer-director of drama as he is of comedy, and this is just one of the many levels in which this film works.

Crimes and Misdemeanors tells two loosely connected stories. The dramatic one concerns an ophthalmologist (Martin Landau) who is being blackmailed by his jealous mistress (Anjelica Huston) who wants him to leave his wife (Claire Bloom). The comic one concerns a documentary filmmaker (Allen) who is forced into making a movie about his obnoxious, successful brother-in-law, a TV producer played by Alan Alda.

Allen is unhappily married and begins to fall for the documentary's producer (Mia Farrow). The twists of the stories are part of its enjoyment, so I won't delve any further. However, whereas Hannah and Her Sisters took his typical neurotic, God-doubting Jewish New Yorker and added a dash of optimism, Crimes goes the other direction.

This is a film of and about the 1980s. It is cynical and has a lot to say on all the topics Allen has specialized in for years — religion, relationships and success.

Religion is what binds the two otherwise unrelated stories together. Landau is treating Allen's other brother-in-law, an optimistic rabbi (Sam Waterston) who is slowly going blind. Waterston's character is, in a way, the most important character in the film, in keeping with the eyes motif established early on.

Landau and Allen both view the world as harsh and devoid of values while Waterston insists that there is a real moral structure out there involving forgiveness and a higher power. Waterston's blindness helps to show the film's message that in these times, a sin seems to be a sin only if you get caught.

Another strand of this philosophical approach is a professor that Woody's character wants to make a documentary about. The professor speaks of religious optimism and how a loving God is beyond man's capacity for reason. He talks about how love is a contradiction and life is painful but we need the pain. His words, and his later off-screen action, help lend the somewhat nihilistic view the film ultimately presents: that morality only exists for those who have it.

The film is full of great lines and great performances, something one expects from a Woody Allen film, but it also is the perfect fusion of Allen's filmic styles. There is Landau, discussing his problems with Waterston (in what may or may not be an imagined conversation) where he tells the rabbi that God is a luxury he can't afford. There is a virtual cascade of classic Woody lines such as "The last time I was inside a woman was when I visited the Statue of Liberty." It also contains some perfect casting choices: There's enough of a resemblance to believe that Landau and Jerry Orbach are indeed brothers.

There are the stylistic and story elements that stem from Allen's love of Ingmar Bergman. In fact, he even uses Bergman's frequent cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, and Nykvist contributes a golden, almost mildewy look to the proceedings. Technically, this is among Woody's best.

His direction has evolved over the years and fully complements his screenplay. Woody's character spends a lot of time taking his niece (Jenny Nichols) to old movies playing in revival houses: musicals, classic gangster flicks, the works. This contributes to the idea that, as much as Woody loves these films, he can't make them in this day and age. If you want happy endings, go to Hollywood. If you want reality, go to New York, especially if Woody Allen is your chauffeur.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, A. Huston, Alda, Ingmar Bergman, Landau, Mia Farrow, Orbach, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, November 21, 2010

From the Vault: Alice

For his 20th cinematic trip out as writer-director, Woody Allen ventures into a whimsical galaxy reminiscent of his work in the "Oedipus Wrecks" segment of New York Stories.

Requisite actress Mia Farrow stars as Alice, a wealthy Manhattan housewife who explores the meaning and direction of her life with the help of an acupuncturist named Dr. Yang (the late Keye Luke) who specializes in magical herbs.

Much of the joy of Alice comes from the various fantastical trips that Dr. Yang's potions take Alice on, so it would be unfair to spoil them in a review.

Unlike the New York Stories segment, which shared the magical elements of Alice, Allen's new film doesn't wear out its welcome. "Oedipus Wrecks" tended to be a one-joke premise that went on too long but Alice just uses its fantasy devices to illuminate the larger story of Alice's transformation.

What sparks Alice's self-seeking quest is Joe (Joe Mantegna), the father of one of her children's classmates. For the first time in her staid married life, Alice feels the need to stray.

However, her strict Catholic upbringing and sense of duty keep her from admitting that her husband Doug (played as a jerk to the subdued hilt by William Hurt) hasn't fulfilled her needs and that Alice must live for herself before her church or her husband.

The themes in Alice are universal and have been addressed by Woody before. Infidelity, religion, family, love and dreams. It's typical Allen, only in Farrow's face.

Farrow's transformation in Woody's movies has been amazing. She has become his alter ego in many ways, serving as his surrogate in the films in which he doesn't appear. It's Catholic guilt instead of Jewish guilt, but the neuroses have become nearly one and the same.

In addition to Farrow, Hurt, Luke and Mantegna, Allen continues his trend of large, surprising casts. Cybill Shepherd is fine in her couple of scenes as a successful producer who doesn't want to be reminded of where she came from and Alec Baldwin has some of the best moments as the ghost of Alice's late love.

The funniest part of the film though belongs to Bernadette Peters' one-scene cameo as Alice's muse, desperately trying to help her write a novel.

Overall though, this is certainly a lesser effort by Allen. It is entertaining, gaining momentum as it goes along, but there still is something lacking.

Granted, it would have been nearly impossible to have anything but a letdown after 1989's excellent Crimes and Misdemeanors, but Alice is certainly not a waste.

Tweet

Labels: 90s, Alec Baldwin, Cybill Shepherd, Mia Farrow, William Hurt, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, September 06, 2010

Dance movie heaven

BLOGGER'S NOTE: Top Hat opened 75 years ago today. This piece by Dan Callahan was originally published in Slant Magazine on Aug. 1, 2005.

By Dan Callahan

Viewed objectively, the partnership of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers shouldn't have worked. He was lighter than air and obsessed with dance; she was a solid apple-cheeked chorus girl-type who wanted to prove herself as a dramatic actress. Technically, she was not up to his standard in the way of later partners like Eleanor Powell and Cyd Charisse. Rogers would be shooting other movies while Astaire rehearsed their dance numbers with choreographer Hermes Pan, and she'd have to come in to learn a dance that hadn't been set on her originally. To top things off, they didn't really like each other much in real life.

Yet on screen they're magical. Why? Katharine Hepburn's famous comment about how Astaire gave Rogers class and she gave him sex is true, if glib. Aside from a certain unexplainable X factor that has to do with the right place (RKO) at the right time (the mid-'30s), I'd say that their big dramatic dances work so beautifully because Astaire recognized the large disappointment behind Rogers' seemingly unflappable reserve. Perhaps he had little use for her off screen, but on screen he responds sensitively to her hidden pain. The way he danced away her doubts is among the most moving (and most narcotically elating) images in film. Her barely perceptible awkwardness as a dancer paid off for the audience. After seeing them together, every woman wanted to dance with Fred Astaire, and Rogers made them feel that they could.

Top Hat is their archetypal movie. Every musical number works, and the mistaken identity plot is pleasant enough, even if there's too much emphatic dithering from the supporting players toward the end (Eric Blore is a pain, but Helen Broderick's sour tolerance still gets laughs). Astaire's first solo, "No Strings," is wonderfully suited to his breezy style. His loud tapping wakes up Rogers, who is in the suite below his, and he makes it up to her by scattering some sand on the floor and putting her to sleep with some slow, caressing steps (one of the most romantic moments in their films).

Their courtship is charming, especially in their superb "Isn't It A Lovely Day To Be Caught In The Rain" number. But nothing can top "Cheek To Cheek," perhaps their best romantic dance. Rogers' feather dress makes her seem as if she's floating, especially when Astaire ends the dance with some lifts and a dreamy backbend. Woody Allen's The Purple Rose of Cairo excerpts this number when Mia Farrow's movie-mad character is ready to give up on life. Whenever I see "Cheek To Cheek," I cannot get Farrow's shy, hopeful face out of my mind. She stands in for all the Depression audiences who, like drug users, escaped into dream-world movies such as Top Hat.

Labels: 30s, Astaire, Cyd Charisse, Ginger Rogers, K. Hepburn, Mia Farrow, Movie Tributes, Musicals, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, March 01, 2010

He's Fictional, But You Can't Have Everything

By Jonathan Pacheco

It's no tall order to write a tragedy set during the Great Depression, but I imagine it takes some restraint to write one where the era's circumstances aren't the immediate sources of distress. The Purple Rose of Cairo, turning 25 today, tells a heartbreaking story that's sadness comes not from the Depression's difficult times, but from one person's antidote to these hardships. This gives the relatively simple tale much more depth, for the filmmaking occupies itself not with plot and historical accuracy, but with understanding its themes — namely, reality versus fantasy, cinematic escapism, and perhaps a slight warning against this defense mechanism. And it's because of this that, though I often cite Annie Hall as my favorite Woody Allen film, I have to side with Edward: The Purple Rose of Cairo is the director at his most masterful, focused, and wise.

I would argue that it's not Cecilia's (Mia Farrow) abusive marriage to Monk (Danny Aiello) that saddens the viewer as much as her fear of doing anything about it. She'll pack a suitcase and walk out on her husband, only to return later that night. She's a naive, submissive, meek mouse of a woman, fragile physically as well as emotionally and psychologically. Her only escape from the disheartening New Jersey world around her is the local cinema. Many people turn to movies to distract them from personal troubles, but Cecilia carries it further, captivated by the film world for days at a time. She can barely function at work without breaking plates or forgetting orders due to her enraptured state.

Imagine her excitement when, after an emotionally damaging day, she watches three straight showings of the newest film in the theater, "The Purple Rose of Cairo," only to have one of the minor characters on screen take notice of her in the audience. Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels) literally leaps off the screen and runs out of the theater with Cecilia, hopelessly in love.

Every time I watch the film, I'm impressed by Jeff Daniels' performance as Tom, straightly playing the pitch-perfect innocence the adventurer-poet is meant to embody. I'm even more amazed when Daniels shows up again as the actor who played Tom, Gil Shepherd (in town trying to convince his character to jump back into the limboed film on screen). Gil's a man desperately reaching for Hollywood stardom, making him susceptible to anyone willing to flatter him. Watch the scene where he meets Cecilia at her house to inquire about Tom's whereabouts. Gil starts the conversation with one purpose, and the next thing you know, he's taking Cecilia out for a meal, completely smitten with her; the turnaround is nothing short of astonishing, and Daniels plays it brilliantly. Every compliment Gil receives turns his character's attitude a few more degrees, and oh, how fluidly Daniels performs this transition.

Daniels' dual roles and Tom's self-aware existence aren't new to anyone who knows their Woody Allen (more recently, think of Melinda and Melinda and the literally out-of-focus Robin Williams character in Deconstructing Harry), but it's in this film that the director simply nails all of it. It's been widely quoted that this is one of the few films Allen feels turned out closest to his original vision, and I believe it. The Purple Rose of Cairo is a taut 82 minutes — always focused, even while on tangents, like when Tom unknowingly wanders into a bordello, nearly roped into an orgy. In this seemingly unrelated scene, Tom turns down sexual offers because he's completely in love with and loyal to Cecilia, and the sequence becomes an emphasis on Allen's idea that women, even working girls, desperately want to believe in the romanticism that Tom personifies. In this film, everything falls in line with the greater narrative.

Allen has often toyed with the idea of shooting films through the mind of the protagonist. Annie Hall's original cut was heavier on this concept, but the final film still supports this idea, from Alvy's words to the audience to his literal trips down memory lane. After the dead rabbit moment in the kitchen, the rest of Stardust Memories is intended to be filmed from the mind of Sandy. And everything in Deconstructing Harry, from the events to the editing, represent Harry's state of mind, not necessarily his reality. Although I never considered this during my initial viewing, I now see the events of The Purple Rose of Cairo as taking place almost exclusively in Cecilia's mind. This viewpoint takes a sad love story and turns it into a depressing tale of what this poor woman resorts to to deal with her terrible life.

Think of the film's title: "The Purple Rose of Cairo," described in the film-within-the-film as an Egyptian rose painted purple. It takes something commonly associated with romance, and perverts it to make it even more exotic. In the same way, Cecilia takes the romantic notion of escaping through movies, and one-ups it: what about escaping from a movie, or escaping into a movie? Tom relays a legend that claims the purple rose of Cairo now grows naturally within the Egyptian tomb, and so Cecilia wishes that her altered, unlikely, and unrealistic romance (first with Tom, then with Gil) can blossom into something true and natural.

When she chooses between the character of Tom and Gil the actor, she's choosing between fantasy and reality. But try to imagine her heartbreak when she realizes that her "reality," in this state of mind, is still a fantasy, as Gil jets for Hollywood the moment Tom hops back onto the screen. Cecilia's become so far removed from true reality — the reality of her trapping marriage, the reality of the depression that surrounds her — that it takes the loss of two lovers to bring her crashing back. But Allen still doesn't let us off the hook, because instead of fully accepting her true reality, Cecilia once more chooses to escape through the movies, "the true love of her life" as Edward puts it. Yes, it's sort of a beautiful tragedy when you think of it that way, but by not dealing with or fully accepting her reality, by alleviating the pain from her fantasy letdown by trying to escape into fantasy once again, Cecilia refuses to heal. She perpetuates the cycle that caused her mental breakdown to begin with. As the film fades to black, Cecilia has the same look on her face that she had shortly before Tom Baxter stepped off the screen and indulged her fantasies, and it's only a matter of time until it happens again.

While the film boasts countless laughs and even a bit of Hollywood satire, Allen firmly holds onto this one, never letting it fly apart in a wild mess. Instead, a tragic air permeates even the laughter of nearly every scene as the director crafts a balanced, cohesive film with such an emotionally important message.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Jeff Daniels, Mia Farrow, Movie Tributes, Robin, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, May 17, 2007

The heart is a very resilient little muscle

It's from an old familiar score

I know it well, that melody

It's funny how a theme

Recalls a favorite dream

A dream that brought you so close to me

I know each word, because I've heard that song before

The lyrics said: "for evermore"

For evermore's a memory

Please have them play it again

And (Then) I'll remember just when

I heard that lovely song before

"I've Heard That Song Before"

by Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn

By Edward Copeland

More than 21 years after I first saw Hannah and Her Sisters, the song is as lovely as ever and provides another sparkling example of Woody Allen when he was in his filmmaking prime.

That first title card plunges us into Hannah and Her Sisters as we learn that Elliot (Oscar winner Michael Caine) has developed a profound attraction to Lee (Barbara Hershey), wife of Lee's sister Hannah (Mia Farrow) and thus begins a myriad of interlocking tales surrounding the three sisters, their exes, lovers and friends. Woody Allen's 1986 film won him his second Oscar for original screenplay and revisiting it, I was struck how it is much less jokey than most of his films that aren't flat-out dramas. There are plenty of laughs to be sure, but they flow more from characters and situations than from punchlines. The story revolves around the three sisters: Hannah, a mostly retired actress turned housewife; Lee, a recovering alcoholic whose employment (if any) is vague who lives with a grumpy older artist named Frederick (Max von Sydow); and Holly (Dianne Wiest, in her Oscar-winning performance), an aspiring actress and a mess with a penchant for cocaine and debts.

The film also tells the story of Mickey Sachs (Woody Allen), Hannah's ex-husband who produces a Saturday Night Live-type television show and almost seems as if he could be what Alvy Singer of Annie Hall turned into years later. Tony Roberts even cameos as Mickey's former writing partner who has found success in television in L.A., just as Roberts' character did in Annie Hall. What's amazing is how fleetly the film moves when there really isn't a strong throughline to lead the action. With the use of the title cards, it's almost as if each section is a short in itself (obviously patterned on Ingmar Bergman's Scenes From a Marriage), but without leaving mixed results from sequence to sequence. The strand that holds it all together is the unpredictability of love, with a side order of fears about mortality.

One thing that never occurred to me until I watched it again is the film's unusual use of voiceovers. In most films with voiceover narration, there usually is a single voice, though there are exceptions (Both Ray Liotta

and Lorraine Bracco narrated sections of Goodfellas), but Hannah and Her Sisters offers voiceovers by five different characters: the three sisters, Elliot and Mickey. The movie may also be the best directing Allen has ever done, not only in terms of pacing and unusual shots but especially in the film's most bravura sequence where the camera circles the three sisters at lunch while each has their own agenda and crisis, some spoken, some not. It may also provide his best use of music, with a soundtrack filled with Bach and Puccini and many standards performed as recordings by the likes of Harry James or in the movie itself by Bobby Short. There's also Lloyd Nolan and Maureen O'Sullivan as the sisters' bickering parents, giving a heartfelt rendition of "Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered" by Rodgers and Hart.

and Lorraine Bracco narrated sections of Goodfellas), but Hannah and Her Sisters offers voiceovers by five different characters: the three sisters, Elliot and Mickey. The movie may also be the best directing Allen has ever done, not only in terms of pacing and unusual shots but especially in the film's most bravura sequence where the camera circles the three sisters at lunch while each has their own agenda and crisis, some spoken, some not. It may also provide his best use of music, with a soundtrack filled with Bach and Puccini and many standards performed as recordings by the likes of Harry James or in the movie itself by Bobby Short. There's also Lloyd Nolan and Maureen O'Sullivan as the sisters' bickering parents, giving a heartfelt rendition of "Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered" by Rodgers and Hart.

The performances are spectacular across the board. I always loved Wiest's work and was especially fond of von Sydow as Frederick, labeling Elliot as a "glorified accountant," telling Daniel Stern that he doesn't sell his art by the yard or to match a sofa or even just channel surfing, commenting on a documentary about the Holocaust that the question isn't "How did this happen?" but, given the way the world is, "Why doesn't it happen more often?" I still think it might be Allen's most well-rounded performance. At the time, I thought that the Oscar for Caine was overly generous, but looking at his performance again now, he is quite good, though I still would have gone with Dennis Hopper. Indeed, questions and answers seem to be at the heart of Hannah and Her Sisters. When Elliot finally confesses his feelings to Lee and realizes that she returns some of them his gleeful response is "I have my answer. I'm walking on air." When Mickey has a health scare, it prompts him to pursue a more spiritual journey, including pursuing possible interest in Catholicism and other religions, deciding that the certainty of death and the uncertainty of faith ruins everything else. His parents, who raised him as a Jew, are less than thrilled and he asks them why there were Nazis to which his father replies, "How the hell should I know why there were Nazis? I don't know how the can opener works." Mickey's search for answers leads him even to contemplate suicide, but for the second Allen film in a row (following The Purple Rose of Cairo), healing is found in a movie theater. He decides that "maybe" is a slim reed to hang your whole existence on, but it's the best we have.

The film also raises more subtle questions that make you wonder what the truth is of the story itself. When Holly laters pursues a writing career and reads her script to Mickey, you are left wondering if the story's denouement is wishful thinking as to the fate of an architect (Sam Waterston) she once pursued who ended up with her friend (Carrie Fisher) or it it actually happened. It's funny either way. Also, when Elliot is shown plying Lee with alcohol during one of their trysts, you have to wonder if he's aware of her alcoholism and if she's fallen off the wagon, but the movie never makes a point of addressing it. Finally, he leaves the biggest question for the end and really, it's really a sort of Rorschach test for the viewer as to whether they are more of a cynic or an optimist. In a flashback earlier in the movie, we learn that when Mickey and Hannah were married, they learned that Mickey was sterile and had to use artificial insemination to get Hannah pregnant. Late in the film, Mickey and Holly become an item and get married and in the final scene, Holly reveals that she's pregnant. Is it a miracle or is she cheating? The film doesn't say and that ending really is a perfect capper for the entire movie.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Barbara Hershey, Caine, Hopper, Ingmar Bergman, Liotta, Mia Farrow, Movie Tributes, Rodgers, Von Sydow, Wiest, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, April 20, 2007

Touch my heart — with your film

By Edward Copeland

I'm not certain what year it was when I first saw Annie Hall, which turns 30 years old today, but I do remember the circumstance. I was still in grade school and a local TV station was showing it late one Friday night. I decided to watch, though I'd never seen a Woody Allen film at this point and all I knew was that this was the movie that stopped my beloved Star Wars from winning the Oscar for best picture. I thought it was funny and I liked it, though it would take years for me to truly appreciate all of its charms and jokes (and about the same time before I finally admitted that yes, the best picture had won for 1977).

"I feel that life is divided into the horrible and the miserable. That's the two categories. The horrible are like, I don't know, terminal cases, you know, and blind people, crippled. I don't know how they get through life. It's amazing to me. And the miserable is everyone else. So you should be thankful that you're miserable, because that's very lucky, to be miserable."

Alvy Singer

It seems odd to me now how strongly I identified with the Woody Allen persona when I was young. Sure, I was funny and cynical, but I certainly wasn't middle-age, Jewish or a New Yorker and I hadn't endured a series of painful relationships. Hell, I was in grade school, really I had no relationship experience at all (though like Alvy Singer, I too never had a latency period). I think a great deal of my identification with Alvy came with the way I was introduced to him and, by extension, Allen: With him talking directly to the screen (i.e., me) and telling two funny jokes about relationships that seemed to make perfect sense to me even at the time. ("And such small portions" and "I would never belong to any club that would have someone like me for a member" seemed to ring particularly true to even my young self.)

Even the gags I didn't truly get upon first viewing (such as the classic Marshall McLuhan moment) were still funny, whether you knew who McLuhan was or what he stood for. The funny thing is that when I re-watched Annie Hall prior to writing this piece, I realized for the first time that the blowhard standing behind Alvy and Annie in line actually is right about Fellini being overly indulgent in terms of films such as Juliet of the Spirits and Satyricon. I could go on endlessly repeating the famous lines and memorable scenes, but I'll try to refrain myself as much as possible on the chance that some people who read this still might not have seen Annie Hall.

Instead, let me just recount some of the many reasons I love this movie. First and foremost, there is Diane Keaton in her Oscar-winning role and at her most effervescent as the charming, infuriating mess that is Annie Hall. Allen always has worked best when he has had a talented muse to center his films around. Keaton was his first great one, Mia Farrow his second. Now, Allen flounders, since Soon-Yi can't fit that bill and, as much as I like Scarlett Johansson, I don't believe she can fill that void either.

Then there are the hilarious flashbacks to his childhood though they could be anyone's childhood, to some extent). Who didn't think many of their classmates were jerks and idiots and who didn't have run-ins with teachers that you just knew intuitively didn't quite have enough on the ball? That attitude extends to adults as well (I still laugh every time Alvy describes intellectuals as people who can be completely brilliant and still not know anything). Then there is this: "Can I confess something? I tell you this as an artist, I think you'll understand. Sometimes when I'm driving... on the road at night... I see two headlights coming toward me. Fast. I have this sudden impulse to turn the wheel quickly, head-on into the oncoming car. I can anticipate the explosion. The sound of shattering glass. The... flames rising out of the flowing gasoline," which may well be the first in a seemingly endless series of great Christopher Walken movie monologues in his role as Annie's brother Duane.

Annie Hall marks the transition of Woody Allen's filmmaking from his flat-out early comedies (most of which are still priceless) to his ventures into other realms. (Allen once famously said that Annie Hall was hardly his 8½, more like his 2½. Who knew how right he was?) As great as Annie Hall was and still is, it really just laid the foundation for some of his greater works to come such as The Purple Rose of Cairo, Hannah and Her Sisters and Crimes and Misdemeanors. Even if he's been in a cinematic slump for awhile, with a few exceptions, his work from 1977-1989 is astounding.

With Annie Hall, he also experimented with the medium, not in any remarkable ways really, but still in ways that impress, from the scene where subtitles translate characters' inner thoughts, to frequent, contrasting split screens and even an animated sequence. Unlike many films from the 1970s, Annie Hall seems fairly timeless (though you do have to gulp when Alvy is outraged to learn that Annie pays $400 a month for a lousy Manhattan apartment. Those were the days...) As Roger Ebert once wrote about Citizen Kane, that film's structure is such that no matter how often you've seen it, if you come in after it's started, you are never quite certain what scene comes next. Annie Hall works much the same way. While Annie Hall above all else is a comedy (and one of the rare times the Academy saw fit to honor a comedy), Alvy Singer does, if you look hard enough, share some superficial similarities to Charles Foster Kane. Both men are described as islands unto themselves and both just want to be loved, though Woody Allen got to speak frankly about sex in a way Orson Welles couldn't be allowed. ("Don't knock masturbation — it's sex with someone I love"; "As Balzac said, 'There goes another novel.'"; "That's the most fun I've had without laughing." Alvy also has his sexual prowess described as a "Kafkaesque experience," which the woman played by Shelley Duvall insists is a compliment.)

In Alvy's final joke, again spoken directly to the audience, he tells of a man who tells a psychiatrist that his brother thinks he's a chicken. The doctor asks why the man doesn't turn him in, to which the man replies, "I would, but I need the eggs." We need eggs such as Annie Hall and I still hold out hope that Woody Allen can rebound with some more great films before his moviemaking career ends, but even if he doesn't, he's left us more than enough quality eggs with which to cook some tasty cinematic omelettes.

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Diane Keaton, Ebert, Fellini, Johansson, Mia Farrow, Movie Tributes, Walken, Welles, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, April 12, 2007

What you can do if you're a total psychotic

By Edward Copeland

Writing about The Purple Rose of Cairo recently put me in a Woody Allen state of mind, remembering back fondly to when he was in his most creatively fertile period. As a result (and with a timely sale at Deep Discount DVD), I revisited Zelig and the film is even better and more impressive than I remembered. This mockumentary is so solid that it puts all of Christopher Guest's efforts to shame and the insertion of Zelig in scenes with famous people foreshadow Forrest Gump, only it's used here to even greater effect. (I know — Orson Welles stuck Charles Foster Kane into scenes with Hitler more than 40 years prior to Zelig, but Allen really took that idea and ran with it).

It's really quite incredible to see some of the clips he's inserted Zelig into, such as the Hitler sequence where it appears that the Nazi truly is interacting with Woody Allen's character. When I first saw Zelig years ago, I thought it was fun, but mainly a one-note gimmick, but the years have only made Allen's achievement seem more impressive.

For quite a bit, Zelig acts as a straight documentary, with real-life authority figures such as Susan Sontag and Saul Bellow commenting on the phenomenon of Leonard Zelig as if he really existed. Zelig was a Depression-era man with a highly unusual condition — the ability to take on the characteristics of whomever he was around at the time.

Mia Farrow plays the only other fictional character of note, Dr. Eudora Fletcher, the psychiatrist determined to get to the bottom of Zelig's condition. It only dawns slowly on the viewer that a comedy is at play, since most of the lines are spoken through the brilliantly deadpan delivery of the narrator (Patrick Horgan). When Allen does finally speak, giving spins on some of his standard material, the spell is broken slightly but the conceit is so well constructed, especially thanks to Gordon Willis' magnificent cinematography, the film gets away with it.

The comedy is frequent, but it's so dry and droll that a lot of it may be lost on a casual viewer. There aren't really acting performances to assess, because Zelig might as well truly be a documentary. If you've never seen the film, I won't spoil the many great gags, but I do have to say that Zelig has only grown greater with age and makes the creative rut that Allen has been stuck in for the past decade or so seem even more depressing.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Mia Farrow, Movie Tributes, Welles, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, March 30, 2007

In New Jersey, anything can happen

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post is part of the Screenwriting Blog-a-Thon being coordinated by Mystery Man on Film.

"I just met a wonderful new man. He's fictional but you can't have everything."

Cecilia (Mia Farrow)

The Countess (Zoe Caldwell): "Go with the real guy, honey, we're limited."

Rita (Deborah Rush): "Go with Tom! He's got no flaws!"

Delilah (Annie Joe Edwards): "Go with SOMEBODY, child, 'cause I's gettin' bored."

By Edward Copeland

Maybe if you're a character such as Delilah, especially a Depression-era stereotype, trapped in a movie that's stalled because one of the characters has stepped off the screen and into the real world, you'd be bored as well. However, if you are a moviegoer lucky enough to be watching Woody Allen's The Purple Rose of Cairo, boredom should be impossible. As far as I'm concerned, this film is Allen's masterpiece. Others will cite Annie Hall or Manhattan or some other titles and while I love those films as well, over time The Purple Rose of Cairo is the Allen screenplay that has reserved the fondest place in my heart. The screenplay isn't saddled with any extraneous scenes and no sequence falls flat as it builds toward its bittersweet ending. For me, it's Woody Allen's greatest screenplay and one of the best ever written as well.

The Orion logo, a circle of stars in a starry sky, appears on the screen, followed by the official AN ORION PICTURES RELEASE. The screen goes black-and-white, credits pop on and off. All the while, Fred Astaire sings "Cheek to Cheek" in the background.

ASTAIRE'S VOICEOVER: (singing) Heaven, I'm in heaven/ And my heart beats so that I can hardly speak./ And I seem to find the happiness I seek/ When we're out together dancing cheek to cheek ...

While Fred Astaire continues singing in the background, the credits fade out, replaced by a large, old-fashioned movie poster, a montage of drawn faces and scenes: In the shadows, to the left of an elongated black shape, is a man wearing a pith helmet; next to his face is the Sphinx, complete with a palm tree. The camera moves past the Egyptian scene, past the black shape, to a drawing of two men in tuxedos. One holds a champagne glass. Behind them is an elegant car, a hint of city glamour next to a streetlamp in front of a faint city skyline. The camera next moves up the elongated black shape to reveal an oversize sophisticated woman; the black shape is her long slinky dress. Above her sleek, bobbed hairdo is the movie's title, THE PURPLE ROSE OF CAIRO ... As Fred Astaire croons in the background, the film cuts to Cecilia's face, staring dreamily at the now offscreen movie poster. Behind her is a parked car in the street; pedestrians pass on the sidewalk. As she gazes, lost in her own world, one gloved hand to her lips, a loud clunking sound is heard; the song abruptly stops...

That thud that interrupts Cecilia's reverie is a letter from the movie theater marquee announcing the next week's movie, The Purple Rose of Cairo. It also firmly establishes us in Woody Allen's look at Depression-era New Jersey and the escape movies offered for those barely scraping by. The Purple Rose of Cairo happens to be the first Allen film I saw in a theater, but it didn't immediately leap to the top of my list of his best movies. It took time and repeat visits to truly appreciate what a near-perfect specimen this bittersweet comedy is.

I think part of the reason is that it is truly the only Woody Allen film that, if you took those familiar black-and-white credits away, you wouldn't recognize as coming from the writer-director. He's not aping Bergman. There is no character serving as the Woody surrogate either in a good way or an embarrassing way (think Kenneth Branagh in the god-awful Celebrity). It's the perfect blend of comedy, fantasy and realism and one of the greatest depictions of the magic of movies ever put on film.

Buster Keaton might have mixed the real world and the movie world in Sherlock Jr., but it was all a dream in the end. In The Purple Rose of Cairo, when Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels) and his pith helmet step off the screen, the repercussions end up being both hilarious, touching and painfully real.

Allen manages to create several complete universes within his 1930s New Jersey. There is the comedy of the characters trapped in the black-and-white world of a movie story that has nowhere to go when Tom departs. There is the drama of Cecilia's bleak existence with her abusive husband Monk (Danny Aiello). There is the romance of Cecilia's adventure with the fictional Tom. There is the blend of satire and straight story as Hollywood descends on the town to try to put a lid on a brewing scandal and to stop Tom Baxters from leaping off the screen elsewhere in the world.

The merging of these worlds create a most unusual love triangle as Cecilia is torn between the perfect but two dimensional Tom and the real-life actor Gil Shepherd who brought him to life. Either one would be an improvement over life with Monk. Don't get me wrong that this is a "serious" Allen. There are a multitude of laughs, but very few seem to come from his usual sensibility. There are ample laughs wrung from the situation of a the fictional Tom wandering around New Jersey and encountering prostitutes and the need for real money. The characters still trapped in the film also provide plenty of opportunities for laughs.

The person though who keeps the entire film centered and deepens it beyond mere comedy is Farrow. She gets some laughs, but her plight is heartbreaking. Cecilia always found her escape from her miserable life of poverty and an abusive husband in the movies and now the movies offer her a chance for true permanent escape, either with a character who doesn't really exist or with the actor who could show her an entirely new life in Hollywood.

Daniels has the most difficult role and he handles it well. Tom is truly guileless and naive because the actor who created him just isn't that good an actor. On the other hand, Daniels' performance as the actor shows how far charm can carry you even when you're obsessed with your career. In the end, when Cecilia sees that her only future lies with Gil, not a two-dimensional character come to life, her blinders don't allow her to see that she's being played, though even Gil seems to have regrets as he quickly gets the hell out of New Jersey.

What really lifts The Purple Rose of Cairo into the realm of the transcendent is its ending. Certainly, it's sad that Cecilia loses both her leading men and has to return to Monk, but it shows the true love of her life is the movies as she wanders, despondent, into the theater and sees Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dancing up a storm again. However, she's saved by the movies and her sadness lifts, if only for that brief time that she's safe there in the dark.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Astaire, Blog-a-thons, Branagh, Ginger Rogers, Jeff Daniels, Keaton, Mia Farrow, Movie Tributes, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Friday, December 23, 2005

From the Vault: New York Stories

Scorsese's film "Life Lessons" stars Nick Nolte as Lionel Dobie, an aging artist procrastinating and worrying about his latest work for a museum exhibition. The return of his assistant Paulette (Rosanna Arquette) provides him with another preoccupation. Lionel loves her, but Paulette returns determined to leave Lionel, her artwork and the city.

The plot, skimmed to its bare essentials for the shortened format, is less a story than an examination of creativity and obsession. The interrelation between Dobie, people and his work mesmerizes and fascinates. Richard Price's screenplay does what it needs to do: It satisfies and even leaves you wanting more.

Nolte, an underrated actor, gives another fine performance as does Arquette as the aspiring artist who may or may not be using Lionel. Scorsese's work in "Life Lessons" deserves to stand with his many masterpieces such as Taxi Driver and After Hours. His dizzying camera perfectly reflects the mood and spirit of the character and his art.

Coppola's "Life Without Zoe" occupies the second slot and it disappoints the most.

Fairly incoherent and meandering, the short (written by Coppola's daughter Sofia) concerns a rich young girl (Heather McComb) who practically lives on her own in a hotel while her parents (Giancarlo Giannini, Talia Shire) spend much of their time traveling around the world. The film's interesting images often fascinate, but nothing exists beneath the shots.

The picture is an empty one, looking great but offering nothing beyond the design. The best moments belong to Don Novello (aka Father Guido Sarducci) as Zoe's butler and Chris Elliott in a brief role as a thief.

After enduring "Life Without Zoe," it is invigorating to see the familiar white-on-black credits that mark all of Allen's films.

Allen's "Oedipus Wrecks" could be called the ultimate comic examination of the Jewish mother stereotype. Allen, making his first film appearance in three years, plays a lawyer engaged to a gentile (Mia Farrow) who earns the strong disapproval of his mother (Mae Questel). Mom constantly nags and interferes in her son's life to the point that Allen tells his psychiatrist that he wishes she would "disappear."

The film takes off from here into Allen's purest piece of film comedy since Broadway Danny Rose. It frequently induces laughter but even at its short length, it may be a tad too long. The idea, which I won't spoil, is clever, but it might be better suited for a short sketch.

Still, it entertains and it is worth relishing, if only for Allen's reactions and Questel, the original voice of Betty Boop, as she makes her son's life hell. Julie Kavner also performs well as Treva, a woman into the occult who tries to help Allen's character with his rather unusual problem. Overall, New York Stories earns a pass despite its weaknesses. Besides, Scorsese's marvelous work alone is worth the admission price.

Tweet

Labels: 80s, Coppola, Mia Farrow, Nolte, Scorsese, Woody

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE