Monday, March 26, 2012

Merging art and commerce

— Pauline Kael, The New Yorker, March 18, 1972

By Edward Copeland

Picture this: The war Michael Corleone returns from at the beginning of The Godfather isn't World War II, but Vietnam. Perhaps Kay Adams looks more like a flower child (Diane Keaton had been a Member of the Tribe in the original Broadway production of Hair after all). Try to fathom what poor Fredo would be experimenting with once they sent him off to Las Vegas. If Paramount Pictures steamrolled over

Francis Ford Coppola from the minute he agreed to direct the film, these things might not be theoretical flights of fancy. On the commentary track of The Godfather DVD, Coppola tells how when he climbed aboard the project, Paramount handed him a completed screenplay that the studio had developed, much as they financed the writing of the novel, with Mario Puzo. Only for some bizarre reason, while setting the story's beginnings in 1945 satisfied Paramount for

Francis Ford Coppola from the minute he agreed to direct the film, these things might not be theoretical flights of fancy. On the commentary track of The Godfather DVD, Coppola tells how when he climbed aboard the project, Paramount handed him a completed screenplay that the studio had developed, much as they financed the writing of the novel, with Mario Puzo. Only for some bizarre reason, while setting the story's beginnings in 1945 satisfied Paramount for the 1969 novel (which, remember, wasn't the blockbuster best seller yet as production plans began), it didn't work for a studio looking to make a quick feature on the cheap. The screenplay given to Coppola moved the events to the 1970s, added hippies and, according to Coppola, this quintessentially New York story would be filmed in Kansas City (though later in the commentary, Coppola refers to a plan to shoot it in St. Louis). "There was none of that post-war ambiance," Coppola said, which was one of the major attractions for him to the project in the first place since he didn't like the novel with its graphic sex and general tawdriness until he discovered the story of the family buried underneath the trash. I imagine that few people out there now have endured the actual reading of Mario Puzo's novel, which, awful as it is, spent 67 weeks on The New York Times best-seller list. Coppola's commentary, recorded in 2004, tries to be as nice as possible about the book because Puzo became a close friend right until his death in 1999. Pauline Kael's review of the movie goes into a lot of detail about the novel before she even starts writing about how good she thinks the movie turned out to be, but a few of her words give you who haven't read it a much better idea than my fuzzy memory of it could conjure.

the 1969 novel (which, remember, wasn't the blockbuster best seller yet as production plans began), it didn't work for a studio looking to make a quick feature on the cheap. The screenplay given to Coppola moved the events to the 1970s, added hippies and, according to Coppola, this quintessentially New York story would be filmed in Kansas City (though later in the commentary, Coppola refers to a plan to shoot it in St. Louis). "There was none of that post-war ambiance," Coppola said, which was one of the major attractions for him to the project in the first place since he didn't like the novel with its graphic sex and general tawdriness until he discovered the story of the family buried underneath the trash. I imagine that few people out there now have endured the actual reading of Mario Puzo's novel, which, awful as it is, spent 67 weeks on The New York Times best-seller list. Coppola's commentary, recorded in 2004, tries to be as nice as possible about the book because Puzo became a close friend right until his death in 1999. Pauline Kael's review of the movie goes into a lot of detail about the novel before she even starts writing about how good she thinks the movie turned out to be, but a few of her words give you who haven't read it a much better idea than my fuzzy memory of it could conjure.

"The movie starts from a trash novel that is generally considered gripping and readable, though (maybe because movies more than satisfy my appetite for trash) I found it unreadable.…Mario Puzo has a reputation as a good writer, so his potboiler was treated as if it were special, and not in the Irving Wallace-Harold Robbins class which, by its itch and hype and juicy roman-à-clef treatment, it plainly belongs.…The novel…features a Sinatra stereotype, and sex and slaughter, and little gobbets of trouble and heartbreak.…Francis Ford Coppola…has stayed very close to the book's greased-lightning sensationalism and yet has made a movie with the spaciousness and the strength that popular novels such as Dickens' used to have.…Puzo provided what Coppola needed: a storyteller's output of incidents and details to choose from, the folklore behind the headlines, heat and immediacy, the richly familiar. And Puzo's shameless turn-on probably left Coppola looser than if he had been dealing with a better book…"

Of course, Coppola had a long way to go and many battles to wage before that finished film could win Pauline's seal of approval.

Before we delve deeper into some of the behind-the-scenes brouhahas, I do want to pause for a moment to mention the one detail of the novel still trapped in my brain that convinced me the book stunk. Admittedly, this stretch of Puzo's work thoroughly amused friends of mine around the same age (junior high), who found the entire sequence hysterical. On the commentary, Coppola raises this, though he can't bring himself to talk about it in clinical detail, other than to say the lengthy plot point stood as a key factor in his thinking long and

hard about whether or not he wanted to make a film version of this book. Now, the movie does show that James Caan's Sonny Corleone gets laid a lot, but that's nothing compared to Puzo's description of Santino. In the novel, covered over many pages, readers learn that Sonny isn't just a lothario, he happens to be a well-endowed lothario. Apparently, when standing at full attention, Sonny proves to be so mammoth in size that his mistress (who eventually will give birth to Andy Garcia for The Godfather Part III) requires corrective gynecological surgery because just having sex with him disfigures her vagina. (She needed the surgery or Baby Andy Garcia might have just slid out like a bowling ball through the return, dangling between her legs by the umbilical cord.) I know what you are thinking — did the Farrelly brothers help Puzo write The Godfather? I have no evidence to support such a rumor, though Peter was 15 and Bobby was 13 when the novel came out, so the two had hit the correct age for that kind of humor — and with The Godfather turning into such a huge hit, who could blame them for never wanting to abandon that mentality? Anyway, Coppola wisely decided that the film could leave out that part of the story, but what he did do borders on genius. He alludes to it by a simple, visual gag by unnamed female wedding guests after they spot Sonny sneaking off with his mistress for an assignation.

hard about whether or not he wanted to make a film version of this book. Now, the movie does show that James Caan's Sonny Corleone gets laid a lot, but that's nothing compared to Puzo's description of Santino. In the novel, covered over many pages, readers learn that Sonny isn't just a lothario, he happens to be a well-endowed lothario. Apparently, when standing at full attention, Sonny proves to be so mammoth in size that his mistress (who eventually will give birth to Andy Garcia for The Godfather Part III) requires corrective gynecological surgery because just having sex with him disfigures her vagina. (She needed the surgery or Baby Andy Garcia might have just slid out like a bowling ball through the return, dangling between her legs by the umbilical cord.) I know what you are thinking — did the Farrelly brothers help Puzo write The Godfather? I have no evidence to support such a rumor, though Peter was 15 and Bobby was 13 when the novel came out, so the two had hit the correct age for that kind of humor — and with The Godfather turning into such a huge hit, who could blame them for never wanting to abandon that mentality? Anyway, Coppola wisely decided that the film could leave out that part of the story, but what he did do borders on genius. He alludes to it by a simple, visual gag by unnamed female wedding guests after they spot Sonny sneaking off with his mistress for an assignation.

In Kael's review, she writes that Puzo claims that he wrote the novel "below my gifts" because he needed the money (other stories report that Puzo was drowning in gambling debts at the time). Coppola, Kael similarly said, told everyone he took the film for the money.

Though he never makes that case on the DVD commentary, most stories sound different depending on the storyteller and evidence exists that Kael had the story correct when she penned that Coppola sought the cash so he could make the movies that he wanted to make. In Kael's opinion, Puzo taking the dough turned out a much worse result than Coppola doing it for the money did. "(Coppola) has salvaged Puzo's energy and lent the narrative dignity," Kael opined. First, he had to land that job. Mark Seal wrote a fascinating look of the events surrounding the making of the film in the March 2009 edition of Vanity Fair titled "The Godfather Wars." In it, he chronicled Coppola's initial reluctance to take the job as well as Paramount, which back then had the oil company Gulf & Western as its parent, considering selling the property instead of ponying up the money to make it. According to Seal's article, Coppola's chief cheerleader for the job at Paramount was Peter Bart, then vice president in charge of creative affairs at the studio. Bart later would run Variety before leaving as the once powerful trade paper went into its death throes, with its probable mercy killing appearing imminent any day now.

Though he never makes that case on the DVD commentary, most stories sound different depending on the storyteller and evidence exists that Kael had the story correct when she penned that Coppola sought the cash so he could make the movies that he wanted to make. In Kael's opinion, Puzo taking the dough turned out a much worse result than Coppola doing it for the money did. "(Coppola) has salvaged Puzo's energy and lent the narrative dignity," Kael opined. First, he had to land that job. Mark Seal wrote a fascinating look of the events surrounding the making of the film in the March 2009 edition of Vanity Fair titled "The Godfather Wars." In it, he chronicled Coppola's initial reluctance to take the job as well as Paramount, which back then had the oil company Gulf & Western as its parent, considering selling the property instead of ponying up the money to make it. According to Seal's article, Coppola's chief cheerleader for the job at Paramount was Peter Bart, then vice president in charge of creative affairs at the studio. Bart later would run Variety before leaving as the once powerful trade paper went into its death throes, with its probable mercy killing appearing imminent any day now.

"Bart felt that Coppola would not be expensive and would work with a small budget. Coppola passed on the project, confessing that he had tried to read Puzo’s book but, repulsed by its graphic sex scenes, had stopped at page 50. He had a problem, however: he was broke. His San Francisco–based independent film company, American Zoetrope, owed $600,000 to Warner Bros., and his partners, especially George Lucas, urged him to accept. “Go ahead, Francis,” Lucas said. “We really need the money. What have you got to lose?” Coppola went to the San Francisco library, checked out books on the Mafia, and found a deeper theme for the material. He decided it should be not a film about organized crime but a family chronicle, a metaphor for capitalism in America."

When Robert Evans, then-head of production at Paramount, heard what Coppola thought the story should be, Evans thought the young director had lost it. More importantly, he feared that Paramount execs above him such as studio president Stanley Jaffe would sell the

rights. Burt Lancaster had offered $1 million for them because he lusted after the role of Don Corleone for himself. The top studio brass weren't as hot as Evans on making the film anyway. Seal's account says "the studio bosses didn’t want to make the movie. Mob films didn’t play, they felt, as evidenced by their 1969 flop The Brotherhood, starring Kirk Douglas as a Sicilian gangster." Evans employed a last-ditch maneuver in hopes of keeping The Godfather, Seal recounts further. "(H)e dispatched Coppola to New York to meet with (Gulf & Western Chairman Charlie) Bluhdorn. Coppola’s presentation persuaded Bluhdorn to hire him. Immediately, he began re-writing the script with Mario Puzo, and the two Italian-Americans grew to love each other.'Puzo was an absolutely wonderful man,' says Coppola. 'To sum him up, when I put a line in the script describing how to make sauce and wrote, ‘First you brown some garlic,’ he scratched that out and wrote, ‘First you fry some garlic. Gangsters don’t brown.’'" Crisis averted. Now Coppola and Paramount just had each other to fight, especially about casting.

rights. Burt Lancaster had offered $1 million for them because he lusted after the role of Don Corleone for himself. The top studio brass weren't as hot as Evans on making the film anyway. Seal's account says "the studio bosses didn’t want to make the movie. Mob films didn’t play, they felt, as evidenced by their 1969 flop The Brotherhood, starring Kirk Douglas as a Sicilian gangster." Evans employed a last-ditch maneuver in hopes of keeping The Godfather, Seal recounts further. "(H)e dispatched Coppola to New York to meet with (Gulf & Western Chairman Charlie) Bluhdorn. Coppola’s presentation persuaded Bluhdorn to hire him. Immediately, he began re-writing the script with Mario Puzo, and the two Italian-Americans grew to love each other.'Puzo was an absolutely wonderful man,' says Coppola. 'To sum him up, when I put a line in the script describing how to make sauce and wrote, ‘First you brown some garlic,’ he scratched that out and wrote, ‘First you fry some garlic. Gangsters don’t brown.’'" Crisis averted. Now Coppola and Paramount just had each other to fight, especially about casting.Since they thwarted Burt Lancaster's dream of playing Vito, Coppola and crew would need an actor to play the don. During discussions, according to Coppola's commentary track, they determined that the Don needed to be played by one of the world's greatest actors and

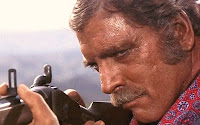

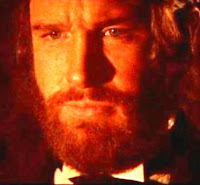

Coppola narrowed that list to two men — Brando, who being in his 40s at the time was younger than the sixtysomething Corleone, and Laurence Olivier, who was in the right age range, seen in the photo at the left as he looked in 1973 in a television production of The Merchant of Venice playing the original Shylock. When casting The Godfather though, representatives described Olivier's health to them as precarious, almost implying the bell would soon toll for the actor. Of course, this wasn't the case and Olivier recovered soon enough that when Brando won the best actor Oscar for 1972 for playing Vito, Olivier held one of the other four nominations for Sleuth and didn't die until 1989. While Brando did get the part, the studio fought like hell to prevent it. His

Coppola narrowed that list to two men — Brando, who being in his 40s at the time was younger than the sixtysomething Corleone, and Laurence Olivier, who was in the right age range, seen in the photo at the left as he looked in 1973 in a television production of The Merchant of Venice playing the original Shylock. When casting The Godfather though, representatives described Olivier's health to them as precarious, almost implying the bell would soon toll for the actor. Of course, this wasn't the case and Olivier recovered soon enough that when Brando won the best actor Oscar for 1972 for playing Vito, Olivier held one of the other four nominations for Sleuth and didn't die until 1989. While Brando did get the part, the studio fought like hell to prevent it. His reputation as difficult and eccentric superseded his reputation as brilliant in their collective minds and it took a screen test, makeup tests and many promises that he'd be on his best behavior before Paramount agreed to let him play the part. Aside from his usual pranks on the set (such as in the scene when two men carry Vito upstairs on a gurney and he secretly added hundreds of pounds of weights beneath the sheet to watch them struggle), Brando actually stayed on his best behavior. Brando saved his only stunt for Oscar night when the world met a Native American woman who called herself Sacheen Littlefeather. (Digression: Coppola won Oscars for adapted screenplay three times: for the first two Godfathers and for Patton. Twice, the films also won best actor and both times, the actors refused to accept the Oscar — though George C. Scott announced in advance he wouldn't if he won and had said the same when nominated for The Hustler.) Imagine another scenario, one Paramount considered before Coppola's hiring. At one point, they seriously planned to cast Danny Thomas as the senior Corleone. I don't know if the film's title would have changed to Make Room for Godfather.

reputation as difficult and eccentric superseded his reputation as brilliant in their collective minds and it took a screen test, makeup tests and many promises that he'd be on his best behavior before Paramount agreed to let him play the part. Aside from his usual pranks on the set (such as in the scene when two men carry Vito upstairs on a gurney and he secretly added hundreds of pounds of weights beneath the sheet to watch them struggle), Brando actually stayed on his best behavior. Brando saved his only stunt for Oscar night when the world met a Native American woman who called herself Sacheen Littlefeather. (Digression: Coppola won Oscars for adapted screenplay three times: for the first two Godfathers and for Patton. Twice, the films also won best actor and both times, the actors refused to accept the Oscar — though George C. Scott announced in advance he wouldn't if he won and had said the same when nominated for The Hustler.) Imagine another scenario, one Paramount considered before Coppola's hiring. At one point, they seriously planned to cast Danny Thomas as the senior Corleone. I don't know if the film's title would have changed to Make Room for Godfather.Casting Vito turned out to be a breeze compared to many names floated to play Michael before Coppola was involved and the director and Paramount displaying equal intransigence about who should play Michael. From the beginning, Coppola visualized the actors as certain

characters in his head, going so far as to bring them down to American Zoetrope's San Francisco offices before any discussions with the studio. In his mind, Sonny always looked like James Caan and no one but Al Pacino played Michael. Back when it looked as if Danny Thomas would be playing the Don, the Gulf & Western CEO approached Warren Beatty not only to take the part of Michael but to produce and direct the film as well, Beatty told Mark Seal. This was 1970, not even a full three years since Bonnie and Clyde. Beatty said to Bluhdorn, "Charlie, not another gangster movie!" Film lovers reaped the rewards of Beatty refusing that offer, not only because ultimately it would lead to Coppola and Pacino in The Godfather but because instead Beatty teamed with Robert Altman on McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Other actors considered for

characters in his head, going so far as to bring them down to American Zoetrope's San Francisco offices before any discussions with the studio. In his mind, Sonny always looked like James Caan and no one but Al Pacino played Michael. Back when it looked as if Danny Thomas would be playing the Don, the Gulf & Western CEO approached Warren Beatty not only to take the part of Michael but to produce and direct the film as well, Beatty told Mark Seal. This was 1970, not even a full three years since Bonnie and Clyde. Beatty said to Bluhdorn, "Charlie, not another gangster movie!" Film lovers reaped the rewards of Beatty refusing that offer, not only because ultimately it would lead to Coppola and Pacino in The Godfather but because instead Beatty teamed with Robert Altman on McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Other actors considered for Michael, some who actually received offers and turned them down included Robert Redford, Martin Sheen, Ryan O’Neal, David Carradine and Jack Nicholson. One thing became clear: Once Paramount determined that it would make the film, it fought about everything. They hated the idea of Pacino as Michael. Evans told Coppola that Pacino was too short for the part and that "a runt" couldn't play Michael. Caan called up Coppola before the film started and informed him that the studio and just offered him the part of Michael. Not only had Coppola always envisioned Caan as Sonny, he viewed the character as the Americanized one and that Michael should look more traditionally Italian which Pacino did and Caan did not, especially since Caan's ancestry was Jewish not Italian. The studio relented long enough to get production started, though Coppola just knew he'd be fired at any time so, as an insurance policy, he scheduled Michael's killing of Sollozzo and police Capt. McCluskey (Al Lettieri, Sterling Hayden) for the first week of filming. Coppola credits this memorable sequence, seen in the clip below, for selling the studio on Pacino and saving his job — temporarily, but the director continued to feel at risk as the studio tried to undermine his ideas at nearly every turn.

Michael, some who actually received offers and turned them down included Robert Redford, Martin Sheen, Ryan O’Neal, David Carradine and Jack Nicholson. One thing became clear: Once Paramount determined that it would make the film, it fought about everything. They hated the idea of Pacino as Michael. Evans told Coppola that Pacino was too short for the part and that "a runt" couldn't play Michael. Caan called up Coppola before the film started and informed him that the studio and just offered him the part of Michael. Not only had Coppola always envisioned Caan as Sonny, he viewed the character as the Americanized one and that Michael should look more traditionally Italian which Pacino did and Caan did not, especially since Caan's ancestry was Jewish not Italian. The studio relented long enough to get production started, though Coppola just knew he'd be fired at any time so, as an insurance policy, he scheduled Michael's killing of Sollozzo and police Capt. McCluskey (Al Lettieri, Sterling Hayden) for the first week of filming. Coppola credits this memorable sequence, seen in the clip below, for selling the studio on Pacino and saving his job — temporarily, but the director continued to feel at risk as the studio tried to undermine his ideas at nearly every turn.Robert Evans didn't like Nino Rota's score. Coppola decided to start playing rough with the studio. His certainty that he could be fired any moment freed him in a way so he began telling them to fire him each time the studio wanted to change something important to him. That music qualified as one of those for Coppola. Evans wouldn't budge, so they agreed to let a screening decide. The audience loved the

movie so much, no one even noticed the score, if you can believe that. Another time, the studio complained that the film didn't have enough "action" in it and told Coppola that they planned to send an action director to the set to see how to pick it up. To beat them to the punch, so to speak, he came up with the scene where Connie (Talia Shire) gets into a huge fight with Carlo (Gianni Russo) when she intercepts a phone call from a woman and assumes he's cheating on her. She starts throwing every dish in the apartment at him. Coppola's young son even got in on the fun — handing objects to his aunt from offscreen for her to let fly. If the studio

movie so much, no one even noticed the score, if you can believe that. Another time, the studio complained that the film didn't have enough "action" in it and told Coppola that they planned to send an action director to the set to see how to pick it up. To beat them to the punch, so to speak, he came up with the scene where Connie (Talia Shire) gets into a huge fight with Carlo (Gianni Russo) when she intercepts a phone call from a woman and assumes he's cheating on her. She starts throwing every dish in the apartment at him. Coppola's young son even got in on the fun — handing objects to his aunt from offscreen for her to let fly. If the studio wasn't bitching about scenes they didn't see, they'd whine about ones that they told him should be coming out. On the commentary track, Coppola refers specifically about a studio hack that he doesn't name since the man has died who constantly appeared on the set saying, "We don't need that scene" or "That scene has been cut." Fortunately, on some sequences, Coppola covered the sequences with two cameras so when this man showed up to try to stop the famous scene of the Don's death in the garden while playing with his grandson, Coppola was able to shut off one to appease him while the second camera continued to work. The studio particularly hated that scene because of the costs associated with flying in the tomatoes and the hack's belief that just

wasn't bitching about scenes they didn't see, they'd whine about ones that they told him should be coming out. On the commentary track, Coppola refers specifically about a studio hack that he doesn't name since the man has died who constantly appeared on the set saying, "We don't need that scene" or "That scene has been cut." Fortunately, on some sequences, Coppola covered the sequences with two cameras so when this man showed up to try to stop the famous scene of the Don's death in the garden while playing with his grandson, Coppola was able to shut off one to appease him while the second camera continued to work. The studio particularly hated that scene because of the costs associated with flying in the tomatoes and the hack's belief that just cutting from the previous scene to Vito's funeral would make the point just as well. The other incident when Coppola believed his firing was imminent concerned the scene where Brando as the Don met with Sollozzo. The studio only would tell Coppola that something dissatisfied them about the scene. Coppola offered to reshoot it, but he was informed that wouldn't be necessary so he knew what that meant. Then, on the commentary, he offers one of his many pieces of advice that he directs specifically for young filmmakers. They'll never fire you on a Wednesday. They'll always wait until Friday, wanting to use the weekend for a smoother transition. Coppola realized he wasn't just making a movie. If he famously described the making of Apocalypse Now as Vietnam, then shooting The Godfather paralleled mob warfare so Coppola hit them before the studio could whack him. Coppola fired four people that day — assistant directors and others that he suspected as being the traitors, and threw Paramount into disarray. With those four gone, he reshot the scene, Paramount didn't object any longer and Coppola didn't get the axe. The final battle over the film came down to the editing process itself. Coppola wanted to cut the film in his San Francisco studios, Paramount wanted to cut it in L.A. Evans relented, but warned Coppola that if he turned in a movie with a running time longer than 2 hours and 15 minutes, they'd move editing to Los Angeles. The first cut ran 2 hours and 45 minutes. Coppola got brutal, removing anything that added color or could be considered extraneous. When done, he had trimmed it to 2 hours and 20 minutes. He took his chances and delivered that to Paramount in L.A. Evans complained that he cut all the color and best stuff and they were moving the editing to L.A.. Coppola realized they would have done that no matter what, but they basically put back everything he cut and then some ending up with the cut we know that's just five minutes short of three hours.

cutting from the previous scene to Vito's funeral would make the point just as well. The other incident when Coppola believed his firing was imminent concerned the scene where Brando as the Don met with Sollozzo. The studio only would tell Coppola that something dissatisfied them about the scene. Coppola offered to reshoot it, but he was informed that wouldn't be necessary so he knew what that meant. Then, on the commentary, he offers one of his many pieces of advice that he directs specifically for young filmmakers. They'll never fire you on a Wednesday. They'll always wait until Friday, wanting to use the weekend for a smoother transition. Coppola realized he wasn't just making a movie. If he famously described the making of Apocalypse Now as Vietnam, then shooting The Godfather paralleled mob warfare so Coppola hit them before the studio could whack him. Coppola fired four people that day — assistant directors and others that he suspected as being the traitors, and threw Paramount into disarray. With those four gone, he reshot the scene, Paramount didn't object any longer and Coppola didn't get the axe. The final battle over the film came down to the editing process itself. Coppola wanted to cut the film in his San Francisco studios, Paramount wanted to cut it in L.A. Evans relented, but warned Coppola that if he turned in a movie with a running time longer than 2 hours and 15 minutes, they'd move editing to Los Angeles. The first cut ran 2 hours and 45 minutes. Coppola got brutal, removing anything that added color or could be considered extraneous. When done, he had trimmed it to 2 hours and 20 minutes. He took his chances and delivered that to Paramount in L.A. Evans complained that he cut all the color and best stuff and they were moving the editing to L.A.. Coppola realized they would have done that no matter what, but they basically put back everything he cut and then some ending up with the cut we know that's just five minutes short of three hours.Once the film had finished and it became abundantly clear that Coppola had made a hit for Paramount, they loved him. Its very limited opening weekend in merely six theaters took in $302,393 (an average of $50,398 per screen). That calculates today to $1,646,978.41 on six screens for a $274,491.86 per screen average. As The Godfather became a bigger hit, Coppola didn't get to enjoy its early success because now that Paramount valued him so much, Robert Evans begged him to come help re-write Jack Clayton's troubled adaptation of The Great Gatsby starring Robert Redford. For three weeks, Coppola says he was "pulling his hair out" trying to fix that. In the end, Coppola doesn't think that Clayton used any of his revisions in the dreadful Gatsby adaptation, which might end up looking better once Baz "Short Attention Span" Luhrmann releases his 3D version of Fitzgerald's masterpiece.

"I felt so embarrassed…I was very unhappy during The Godfather. I had been told by everyone that my ideas for it were so bad and I didn't have a helluva lot confidence in myself — I was only 30 years old or so — and I was just hangin' on by my wits…I had no idea that this nightmare was going to turn into a successful film much less a film that would become a classic."

Well, maybe directing a movie isn't always fun, at least that's Coppola's recollection of his time on The Godfather. He shot the film for $6.5 million in 52 days, but he admits he felt like an outsider on his own set. (Since it did become a huge blockbuster, Part II received a

budget bump to $11 million and they actually got to go on location for shooting.) He speaks honestly about how the great cinematographer Gordon Willis and other crewmembers wondered why Coppola got the job. They didn't quite understand things that he tried but by the sequel, that had all changed. That took some time to happen though. Willis, the man who deserves much of the credit for the film's great look, often shook his head at Coppola's ideas. He particularly disdained high shots, though Coppola made him do some anyway, specifically when they try to kill Vito so you can see the oranges roll into the street and during the Sollozzo killing. Coppola recounts one incident when nature called and as he sat in the bathroom stall, two crewmembers walked in, unaware of Coppola's presence. "What do you think of this director?" one asked the other. "Boy, he doesn't know anything. What an asshole he is!" the other replied. It didn't help Coppola's confidence. Listening to his commentary, it doesn't just illuminate the history of the film's production, you also hear Coppola react to things that still bother him because of the cheap production such as obvious stock footage of cars driving in New York in the 1940s or cheap second unit shots of signs in Las Vegas. The low budget did force some ingenuity on him as well. When it came time to

budget bump to $11 million and they actually got to go on location for shooting.) He speaks honestly about how the great cinematographer Gordon Willis and other crewmembers wondered why Coppola got the job. They didn't quite understand things that he tried but by the sequel, that had all changed. That took some time to happen though. Willis, the man who deserves much of the credit for the film's great look, often shook his head at Coppola's ideas. He particularly disdained high shots, though Coppola made him do some anyway, specifically when they try to kill Vito so you can see the oranges roll into the street and during the Sollozzo killing. Coppola recounts one incident when nature called and as he sat in the bathroom stall, two crewmembers walked in, unaware of Coppola's presence. "What do you think of this director?" one asked the other. "Boy, he doesn't know anything. What an asshole he is!" the other replied. It didn't help Coppola's confidence. Listening to his commentary, it doesn't just illuminate the history of the film's production, you also hear Coppola react to things that still bother him because of the cheap production such as obvious stock footage of cars driving in New York in the 1940s or cheap second unit shots of signs in Las Vegas. The low budget did force some ingenuity on him as well. When it came time to film the sequence where Michael goes to the hospital to see his recovering father and notices the lack of security, they didn't realize until editing that not enough suspense had been built up because where they filmed had such limited space. George Lucas searched through discarded strips of films for shots made of the hospital corridor and they strung them together to give the illusion that it was longer and to increase the suspense. Late in production, there turned out to be several scenes that Coppola realized they needed, the most important being that he'd failed to write a one-on-one scene between Pacino and Brando. Since he was in a frenzy as it was, he called up his friend Robert Towne and he quickly cranked out that memorable scene where Vito tells Michael what to watch out for and expresses regrets that he has assumed his role as don since he never wanted that life for him. He dreamed of a "Senator Corleone" or "Governor Corleone." Finally, Vito sighs, "There just wasn't enough time." "We'll get there, pop. We'll get there," Michael replies. One of the best-written scenes in the entire film came from a screenwriter who received no credit for it. Forget it Robert, it's Hollywood.

film the sequence where Michael goes to the hospital to see his recovering father and notices the lack of security, they didn't realize until editing that not enough suspense had been built up because where they filmed had such limited space. George Lucas searched through discarded strips of films for shots made of the hospital corridor and they strung them together to give the illusion that it was longer and to increase the suspense. Late in production, there turned out to be several scenes that Coppola realized they needed, the most important being that he'd failed to write a one-on-one scene between Pacino and Brando. Since he was in a frenzy as it was, he called up his friend Robert Towne and he quickly cranked out that memorable scene where Vito tells Michael what to watch out for and expresses regrets that he has assumed his role as don since he never wanted that life for him. He dreamed of a "Senator Corleone" or "Governor Corleone." Finally, Vito sighs, "There just wasn't enough time." "We'll get there, pop. We'll get there," Michael replies. One of the best-written scenes in the entire film came from a screenwriter who received no credit for it. Forget it Robert, it's Hollywood.

The Godfather comes stocked with so many memorable sequences, it's damn near impossible to list them all, but perhaps the most famous one of all, one which Coppola conceived for the movie, remains the most imitated of them all. Coppola himself tried to do variations in both of the Godfather sequels but, as with most things, it's hard to top the original. The ending killing spree montage surrounding the baptism of Carlo and Connie's newborn son with Michael standing by to be the child's godfather came about as a matter of practicality. In the novel, the revenge taken on the heads of the five families and Bugsy Siegel-stand-in Moe Green out in Vegas (played briefly but memorably by the great Alex Rocco) covered about 30 pages or so in the book. In the script, Coppola needed to condense that to two pages. As coincidence would have it, around the same time of the contemplation about how to accomplish this, Coppola's wife gave birth to future Oscar-winning screenwriter Sofia Coppola. Baby Sofia wasted no time joining the family business, even though she took on the acting challenge of portraying a baby boy. Her birth inspired Coppola to unify the killings around the baptism ceremony, something that seemed even more appropriate once he reminded himself of the specific baptism text. "Do you renounce Satan?" Still, Coppola said that the ingredient that makes the sequence truly work came courtesy of co-editor Peter Zinner who added the organ tract. Play the clip and try to imagine the sequence without that organ. I think Coppola has that exactly right.

Now, one final time I'm going to plug the Vanity Fair article from 2009 by Mark Seal called "The Godfather Wars". It's online and free and I was tempted to use a lot of material from it, but I had to cut somewhere so I didn't get into the really juicy stuff involving the real Frank Sinatra, the real mobsters and the interaction between the Mafia and the studios. Hell, I didn't even go into the story of who the real Johnny Fontane might have been. It's all in there, so it's worth reading. However, I'm not done. The Godfather was a trilogy after all, so I have one more post coming, which mostly will just me talking about what I think about the film itself with a little bit of other gangster-related entertainment thrown it. I give you my word: I'll do my damnedest to make certain that my third part turns out better than Coppola's did. I end with one last bit from Seal's piece, relating to something from the novel and what Mario Puzo said once.

"One of the most quoted lines from Puzo’s novel never made it to the screen: 'A lawyer with his briefcase can steal more than a hundred men with guns.' Before his death, in 1999, Puzo said in a symposium, 'I think the movie business is far more crooked than Vegas, and, I was going to say, than the Mafia.'”

Tweet

Labels: 70s, Altman, Brando, Caan, Coppola, Diane Keaton, Fitzgerald, George C. Scott, Hayden, Kael, Lancaster, Lucas, M. Sheen, Nicholson, Olivier, Pacino, Redford, Sinatra, Towne, W. Beatty

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Centennial Tributes: Jules Dassin Part II

By Edward Copeland

As we dive into the second half of this tribute to Jules Dassin, we're on an uphill climb artistically and a downhill slide personally as we talk about when he made his best films, including two out-and-out masterpieces, and when the witch-hunting politicians froze him out of movie work by getting Hollywood to blacklist him because of his youthful flirtation with communism. Never mind that he resigned from the Communist Party soon after joining when Stalin signed his 1939 pact with Hitler, once a commie, always a commie, right? At least that was the attitude then. We haven't reached that point yet. First, following making the great Brute Force, Dassin re-teams with producer Mark Hellinger for The Naked City, a landmark because it was the first sound film to shoot entirely in New York. Henry Hathaway had filmed some scenes of 1945's The House on 92nd Street on the streets of New York, but not the entire movie. Another film had shot partly on the streets of New York, but The Naked City became the first movie to film its entire production there. If you started here accidentally and missed Part I, click here.

Hellinger's role in The Naked City extended beyond producing — he also narrated the film which, to me at least, turns out to be a demerit at times. In his 1948 New York Times review, Bosley Crowther, mixed on the movie overall, referred to the narration as "a virtual Hellinger column on film." Not all the narration is cringeworthy (Two examples: "How many things this sky has seen that man has done to man"; "Milk! Isn't there anything else for ulcers except for milk?") Some come off fine such as when

Hellinger notes, "There's a pulse to a city that never stops beating." When the narration grates the most are the times when it sounds like a talkative moviegoer asking their companion annoying questions such as, "Is Henderson the murderer? Did a taxicab take him to the Pennsylvania Railroad Station? Who is Henderson? Where does he live? Who knows him?" The movie itself starts with an overhead shot of the city skyline as Hellinger waxes on about the city as the daytime shots turn into nighttime images and he tells us, "This is the city when it's silent or asleep, as if it ever really is." After his narration introduces us to various inhabitants of the city who work nights, he also shows us people resting at home or out on the town (cleverly introducing people who will be major characters later without pointing that out) "And while some people work and most sleep, others are at the close of an evening of relaxation — " We see a night club getting ready to close and its attendees departing before the camera switches to a young woman's apartment where we see her being murdered by two men. "And still another — is at the close of her life." The killers try to fake her death as a bathtub drowning and we see the movie's destination at last. After some more wandering around the city the next morning (including one killer getting drunk and nervous about the crime and his co-conspirator offing him and dumping his body in the river), once the dead woman's maid discovers her body, they show a particularly nice sequence of the chain of calls through switchboard operators going from hospital to a police precinct to the medical examiner before finally ending up at the homicide squad.

Hellinger notes, "There's a pulse to a city that never stops beating." When the narration grates the most are the times when it sounds like a talkative moviegoer asking their companion annoying questions such as, "Is Henderson the murderer? Did a taxicab take him to the Pennsylvania Railroad Station? Who is Henderson? Where does he live? Who knows him?" The movie itself starts with an overhead shot of the city skyline as Hellinger waxes on about the city as the daytime shots turn into nighttime images and he tells us, "This is the city when it's silent or asleep, as if it ever really is." After his narration introduces us to various inhabitants of the city who work nights, he also shows us people resting at home or out on the town (cleverly introducing people who will be major characters later without pointing that out) "And while some people work and most sleep, others are at the close of an evening of relaxation — " We see a night club getting ready to close and its attendees departing before the camera switches to a young woman's apartment where we see her being murdered by two men. "And still another — is at the close of her life." The killers try to fake her death as a bathtub drowning and we see the movie's destination at last. After some more wandering around the city the next morning (including one killer getting drunk and nervous about the crime and his co-conspirator offing him and dumping his body in the river), once the dead woman's maid discovers her body, they show a particularly nice sequence of the chain of calls through switchboard operators going from hospital to a police precinct to the medical examiner before finally ending up at the homicide squad.

The Naked City follows the investigation of that young lady's murder in an almost documentary style. Originally, Hellinger intended to use Homicide as the title but then decided to borrow The Naked City from the books of photographs by famous crime scene photographer Weegee, whose life was fictionalized in the 1992 film The Public Eye starring Joe Pesci, because he wanted the movie to have the feel of Weegee's photos. Playing the men leading the investigation were Barry Fitzgerald as Det. Lt. Dan Muldoon, the veteran with two decades of experience, and Don Taylor as Det. Jimmy Halloran, the greenhorn who'd only been working homicide for three months. Muldoon always has to explain to Halloran the right way to solve a case such as the one they are in, giving Fitzgerald the chance to say things like "That's the way you run a case, lad — step by step" and sound even more Irish than usual as he does it. When

they determine that the murder had to be committed by two people, Muldoon pins it on "Joseph P. MacGillicuddy," his version of John Doe. Since The Naked City strives for realism, one thing sticks out that I tend not to notice in other pre-1966 police movies or TV shows: There were no such things as Miranda rights so you never hear anyone told, "You have the right to remain silent, etc." The fine cast also includes Howard Duff, reuniting with Dassin from Brute Force, as a compulsive liar who was involved with both the dead woman and her best friend (Dorothy Hart). If you look closely, the film overflows with familiar faces in brief, mostly uncredited roles including Paul Ford, John Marley, Arthur O'Connell, David Opatoshu and, making their film debuts, Kathleen Freeman, James Gregory and John Randolph. There also is a very funny scene where Halloran seeks information from a sidewalk store clerk selling soda on the whereabouts of the suspected killer and the vendor is played by the comic great Molly Picon. However, the film's true star is New York.

they determine that the murder had to be committed by two people, Muldoon pins it on "Joseph P. MacGillicuddy," his version of John Doe. Since The Naked City strives for realism, one thing sticks out that I tend not to notice in other pre-1966 police movies or TV shows: There were no such things as Miranda rights so you never hear anyone told, "You have the right to remain silent, etc." The fine cast also includes Howard Duff, reuniting with Dassin from Brute Force, as a compulsive liar who was involved with both the dead woman and her best friend (Dorothy Hart). If you look closely, the film overflows with familiar faces in brief, mostly uncredited roles including Paul Ford, John Marley, Arthur O'Connell, David Opatoshu and, making their film debuts, Kathleen Freeman, James Gregory and John Randolph. There also is a very funny scene where Halloran seeks information from a sidewalk store clerk selling soda on the whereabouts of the suspected killer and the vendor is played by the comic great Molly Picon. However, the film's true star is New York.

While The Naked City gets lumped into the noir category, personally I don't think it belongs there. While The Naked City turns out mostly fine, the film doesn't approach the greatness of Brute Force or Dassin's films that follow. What makes The Naked City stand out from other films has little to do with its story or acting, but its landmark use of New York — and I mean the real New York, not Toronto. Dassin employed several tricks to film on the streets without crowds getting in the way because word always leaked as to where they would be shooting. In one of the Criterion interviews, he tells of a fake portable newsstand they had to conceal the camera as well as a flower delivery van with a mirror on the side that they could see out of but outsiders couldn't see in. They also employed jugglers to distract onlookers so they wouldn't disrupt shooting.

On the DVD interview, Dassin said his favorite method was to place this guy a bit down the street from where they were shooting, have him climb up a pole, wave a flag and give patriotic speeches. While he mesmerized crowds, the film crew got their work done. Some of that location shooting still amazes. Taylor as Halloran does most of the running throughout the city, on and off subways and buses, past landmarks still familar today and, most especially, the climactic foot chase after the killer that leads to awesome shots on the Williamsburg Bridge. The movie ended up winning the Oscar for best black & white cinematography for William H. Daniels and best film editing for Paul Weatherwax. Now, Dassin contended that elements of the films that put more of an emphasis on class differences within the city and other social issues were cut from the film before release. In many interviews, he said that by the time filming had been completed, rumor already had begun to swirl that he might be called before HUAC to testify about his former membership in the Communist Party. He also didn't believe Hellinger would make those cuts, mainly because Universal didn't want to release The Naked City because they didn't know how to market it. However, Hellinger's contract with the studio had a clause requiring them to release it — and a good thing that it did because three months before The Naked City finally did reach theaters, Hellinger died of a heart attack at 44, another reason Dassin doubted the cuts were his. To paraphrase the film's famous closing line of Hellinger narration, "There are eight million stories from the Hollywood blacklist. This just leads to a much bigger one."

Before Dassin found a new home in Hollywood, he finally got that chance to direct some theater again, staging two Broadway productions in 1948. First, he directed the original play Joy to the World by Allan Scott, the screenwriter of six Astaire-Rogers musicals including Top Hat and Swing Time as well as other films. The comedy takes aim at Hollywood and the difficulty one has maintaining his integrity in the movie business. The play, which ran from March 18 to July 3 at the Plymouth Theatre, also has a strong plea for intellectual freedom and against censorship. Produced by John Houseman, its cast included Morris Carnovsky, who would appear in Dassin's next film and on the blacklist, being named by both Elia Kazan and Sterling Hayden; Bert Freed, TV's first Columbo; and Marsha Hunt, who starred in two of Dassin's MGM films — The Affairs of Martha and A Letter to Evie. The second production was the musical Magdalena which ran from Sept. 20 through Dec. 4. The songs were by lyricists Robert Wright and George Forrest and composer Heitor Villa-Lobos. It was John Raitt's first show following Carousel and choreographed by the most influential yet least-known dance master Jack Cole, subject of an in-development musical project with its eye on Broadway today. One of his two assistant choreographers on Magdalena was Gwen Verdon.

When Dassin headed back west, Darryl F. Zanuck and 20th Century Fox came calling, seeking to sign him to direct A.I. Bezzerides' adaptation of his own novel Thieves' Market, renamed Thieves' Highway. Before that project got rolling, Dassin received an urgent phone call from Zanuck with a very important question: "Are you now or were you ever familiar with the fundamentals of playing baseball?" Dassin told him yes. In an interview recorded in New York in 2000 and on the Criterion Collection DVD of Rififi, shared this fun little anecdote. It seems that the MGM vs. Fox baseball game was coming up the following weekend and Fox was short a player and Zanuck wanted to see if Dassin could be the one. According to Dassin, he turned out to be the MVP of the game as Fox beat MGM, which apparently was an unusual occurrence. Dassin's agent called him in a rush, wanting to know if Dassin had signed the contract for Thieves' Highway yet. Dassin told him that he had. The agent told him that was too bad — after his performance in the ballgame, he could have negotiated him a higher salary for the film.

While The Naked City didn't really seem like noir to me, Thieves' Highway most definitely does, though it's noir in a setting I never imagined before — crooks run amok among those who sell fresh fruit and vegetables. Richard Conte stars as Nick "Nico" Garcos, a veteran who traveled the world following the war and brings home gifts from everywhere to his proud Greek family. His father Yanko (Morris

Carnovsky) is even joyfully singing a Greek song when his boy shows up unannounced, surprising him. (Interesting that as important as Greece will become in Dassin's life later that it's a distinct element of this film.) While the mood overflows with happiness in the Garcos house, Nick discovers that things haven't gone well during his absence when one of his presents turns out to be a special pair of shoes for his father and he urges him to try them on. There's a problem — Yanko can't wear shoes anymore. He rolls away from the table to reveal to his son that he no longer has legs. His father tells him the story about how he had a huge load of the season's first crop of juicy tomatoes and one of the biggest produce dealers on the San Francisco market Mike Figlia (Lee J. Cobb) had agreed to buy them but as he asked for his money, Figlia insisted they have a drink to celebrate first. That drink turned into more drinks and the next thing Yanko knew, he was on the side of the road under his wrecked truck minus his legs. Figlia claims he paid him and someone must have taken the money from the truck. To make matters worse, since he couldn't use the truck anymore, he sold it and the man he sold it to has stiffed him on payment as well. While Nick's mom (Tamara Shayne) tries to calm things down and argues that perhaps Figlia told the truth, Nick can tell that Figlia was lying and his dad never got paid. First though, he's getting the truck back.

Carnovsky) is even joyfully singing a Greek song when his boy shows up unannounced, surprising him. (Interesting that as important as Greece will become in Dassin's life later that it's a distinct element of this film.) While the mood overflows with happiness in the Garcos house, Nick discovers that things haven't gone well during his absence when one of his presents turns out to be a special pair of shoes for his father and he urges him to try them on. There's a problem — Yanko can't wear shoes anymore. He rolls away from the table to reveal to his son that he no longer has legs. His father tells him the story about how he had a huge load of the season's first crop of juicy tomatoes and one of the biggest produce dealers on the San Francisco market Mike Figlia (Lee J. Cobb) had agreed to buy them but as he asked for his money, Figlia insisted they have a drink to celebrate first. That drink turned into more drinks and the next thing Yanko knew, he was on the side of the road under his wrecked truck minus his legs. Figlia claims he paid him and someone must have taken the money from the truck. To make matters worse, since he couldn't use the truck anymore, he sold it and the man he sold it to has stiffed him on payment as well. While Nick's mom (Tamara Shayne) tries to calm things down and argues that perhaps Figlia told the truth, Nick can tell that Figlia was lying and his dad never got paid. First though, he's getting the truck back.

When he finds Ed Kinney (Millard Mitchell), the man who bought the truck, Nick demands the keys to the truck or the money. Kinney complains that he can't pay right now because the truck has been giving him fits but he needs it to pick up a load of golden delicious apples. Nick makes a deal that he'll be his partner to pick up the apples and take them to San Francisco for the sale. The one hitch — Kinney already had a deal set with two guys Slob and Pete (Jack Oakie, Joseph Penney) so Kinney has to make up a story about how he can't make the run. The men go away disappointed — but they also tail him and see that he's lying and make it a point to harass them. If Mitchell looks familiar, he's probably best known for his role three years later as movie exec R.F. Simpson in Singin' in the Rain. Mitchell's career was cut short. A heavy smoker, lung cancer claimed his life at the age of 50 in 1953. Another interesting tale that comes out of the Dassin interviews on DVD is that Oakie, the longtime comic actor who scored an Oscar nod for his Mussolini spoof in Chaplin's The Great Dictator, was completely deaf when he made Thieves' Highway, something that Dassin didn't realize for weeks because Oakie was so good at picking up cues from other actors and never missed his mark or messed up a take. After Kinney and Nick team up, the first portion of the film concentrates on the long haul to San Francisco after they pick up the apples with Nick driving the decrepit truck, Kinney following in another and Slob and Pete harassing them along the way. As Dassin said, the enemy for these men is fatigue and drivers employed many tricks to stay wake on the roads at night.

After a near disaster, Kinney decides it's best if he and Nick switch trucks, letting him, the more experienced driver, try to hold it together while Nick takes the better rig with the first half of the load on to San Francisco. As in The Naked City, Dassin breaks some ground here by doing some amazing location shooting in San Francisco's market area with crowded streets and lots of activity. When we

arrive there, that's when Cobb appears playing the most diabolical produce salesman in the history of film. Cobb's centennial was Dec. 8, but I got so backed up with other projects I wasn't able to do a proper salute to this towering actor. In the 2005 interview on the DVD, Dassin said that Cobb truly "enjoyed his villainy." During the work on this piece, I uncovered more and more names of actors and directors who named names before HUAC that I had never known about before. I mentioned Sterling Hayden earlier, which was news to me. I also didn't know about Cobb. It's odd

arrive there, that's when Cobb appears playing the most diabolical produce salesman in the history of film. Cobb's centennial was Dec. 8, but I got so backed up with other projects I wasn't able to do a proper salute to this towering actor. In the 2005 interview on the DVD, Dassin said that Cobb truly "enjoyed his villainy." During the work on this piece, I uncovered more and more names of actors and directors who named names before HUAC that I had never known about before. I mentioned Sterling Hayden earlier, which was news to me. I also didn't know about Cobb. It's odd how all the ire and bile aimed at people who did name names seemed to be reserved for Elia Kazan. In Cobb's case, the pressure on the actor when he was called to testify before HUAC had nearly brought his wife to a nervous breakdown so Cobb felt compelled to name names to preserve his wife's sanity. Regardless, that doesn't take away from the fact that Cobb was a great actor and not just anyone can turn a produce dealer into a plausible bad guy. Conte matches him well as the good guy without turning Nick into a bland opponent. When things heat up between Nick and Figlia and Figlia suggests they go off to his office, one man comments that Figlia will "eat that kid alive." A buyer named Midge who's seeking golden delicious apples and is played by Hope Emerson, who will be a memorable villain herself the following year as the women's prison matron in Caged, responds, "I'll take odds on the kid." One of Figlia's deceptive tricks against Nick involves utilizing a local hooker named Rica (played by Valentina Cortese, best known for her Oscar-nominated turn in Truffaut's Day for Night, in only her second English-language film and her first shot in the U.S, though her last name is spelled Cortesa). Rica keeps Nick occupied while his truck, which is stuck in front of Figlia’s stand because of flat tires, gets raided and has its apples sold off by Figlia. In the 2005 interview, Dassin told of how Zanuck was a very hands-on producer. Since Rica would inevitably turn out to be the proverbial hooker with a heart of gold who would end up aiding Nick, Zanuck insisted that they write in a part of "a bourgeois fiancée who betrays Nick" to justify the hero falling for the hooker. Barbara Lawrence played that role, Polly Faber.

how all the ire and bile aimed at people who did name names seemed to be reserved for Elia Kazan. In Cobb's case, the pressure on the actor when he was called to testify before HUAC had nearly brought his wife to a nervous breakdown so Cobb felt compelled to name names to preserve his wife's sanity. Regardless, that doesn't take away from the fact that Cobb was a great actor and not just anyone can turn a produce dealer into a plausible bad guy. Conte matches him well as the good guy without turning Nick into a bland opponent. When things heat up between Nick and Figlia and Figlia suggests they go off to his office, one man comments that Figlia will "eat that kid alive." A buyer named Midge who's seeking golden delicious apples and is played by Hope Emerson, who will be a memorable villain herself the following year as the women's prison matron in Caged, responds, "I'll take odds on the kid." One of Figlia's deceptive tricks against Nick involves utilizing a local hooker named Rica (played by Valentina Cortese, best known for her Oscar-nominated turn in Truffaut's Day for Night, in only her second English-language film and her first shot in the U.S, though her last name is spelled Cortesa). Rica keeps Nick occupied while his truck, which is stuck in front of Figlia’s stand because of flat tires, gets raided and has its apples sold off by Figlia. In the 2005 interview, Dassin told of how Zanuck was a very hands-on producer. Since Rica would inevitably turn out to be the proverbial hooker with a heart of gold who would end up aiding Nick, Zanuck insisted that they write in a part of "a bourgeois fiancée who betrays Nick" to justify the hero falling for the hooker. Barbara Lawrence played that role, Polly Faber.

In addition to Thieves' Highway's noirish elements, which basically get segregated to San Francisco once Nick arrives and Figlia and Rica join the film, the movie's other half covers Kinney's treacherous drive in the truck that's barely holding together. Dassin builds genuine suspense in these scenes, aided by Alfred Newman's score. His journey isn't helped by the constant taunting by Slob and Pete, but as he steers the truck through curvy, mountainous highways, the sequences seem to foreshadow what would come several years later in Henri-Georges Clouzot's The Wages of Fear. When the drive finally goes fatally wrong, the truck crashes and rolls down an embankment, apples going everywhere. Even Slob and Pete rush down, but it's too late as the truck bursts into flames. "From that angle, apples rolling down the hill into the camera. I said to myself, 'That's a good shot.' I think that's one of the shots I've enjoyed most in films I've made," Dassin said in 2005. One thing in Thieves' Highway that didn't particularly please Dassin was that Zanuck shot an entirely new ending that he didn't know about because he already was in London prepping Night and the City. When Nick finally gets his physical revenge on Figlia, Zanuck's ending added police coming in to make the point that people "shouldn't take the law into their own hands." However, given what Zanuck did for Dassin overall when the witchhunters came calling, he couldn't complain that much. When the shit really started to hit the fan, it didn't sound as if Zanuck was someone who would be as helpful as he was during Dassin's crisis. In 1949, word came down that HUAC was going to call Dassin to testify and Zanuck and other Fox executives had a meeting about "the problem." In the 2004 L.A. County Museum of Art interview, Dassin said that Zanuck told him, "He was going to step on my neck because I was a dirty red."

is to be a nice guy, but you can't make it.'" — Jules Dassin

As Dassin went on to tell in that 2004 interview, after Zanuck's "threat," he was surprised to find the producer at his front door — not something you'd expect from someone at Zanuck's level. He informed Dassin that he was flying to London the next day and handed him the novel Night and the City by Gerald Kersh. Dassin told Zanuck he couldn't rush off on a moment's notice like that — he had family

problems. Zanuck disagreed with the director, saying that he also had family needs and this could end up being the last film he ever made. Zanuck advised him to get shooting on the film as fast as he could and to do the most expensive scenes first so the studio wouldn't have an excuse to shut the production down. Dassin followed Zanuck's advice and was in London readying the shoot when he learned that he'd been called to

problems. Zanuck disagreed with the director, saying that he also had family needs and this could end up being the last film he ever made. Zanuck advised him to get shooting on the film as fast as he could and to do the most expensive scenes first so the studio wouldn't have an excuse to shut the production down. Dassin followed Zanuck's advice and was in London readying the shoot when he learned that he'd been called to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Zanuck informed the panel that he was abroad and got his scheduled hearing postponed. When Dassin was about two weeks away from the start of shooting on the film, Zanuck called. He asked Dassin if he agreed that he owed him one. Yes, he did owe him, Dassin said in the 2004 interview. Zanuck requested a favor — he wanted Dassin to cast Gene Tierney in a role. Dassin was confused, since there wasn't a role in the movie that she could really play, but Zanuck explained that a love affair had just ended very badly for the actress and she was almost suicidal. When she got in those states, Zanuck said, the only thing that snaps her out of it is work. Quickly, the role of Mary Bristol was written into the script of Night and the City and Tierney joined Richard Widmark and the rest of the talented cast in one of the two best films Dassin ever made. Kersh, the author of the novel the film was based on, did not agree. Dassin never admitted it until an interview in 2005, but Zanuck had encouraged him to everything in such a rush, he never read the book. Many years later, when he did, he could see why Kersh got mad — Night and the City the movie had no resemblance to Night and the City the novel whatsoever.

appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Zanuck informed the panel that he was abroad and got his scheduled hearing postponed. When Dassin was about two weeks away from the start of shooting on the film, Zanuck called. He asked Dassin if he agreed that he owed him one. Yes, he did owe him, Dassin said in the 2004 interview. Zanuck requested a favor — he wanted Dassin to cast Gene Tierney in a role. Dassin was confused, since there wasn't a role in the movie that she could really play, but Zanuck explained that a love affair had just ended very badly for the actress and she was almost suicidal. When she got in those states, Zanuck said, the only thing that snaps her out of it is work. Quickly, the role of Mary Bristol was written into the script of Night and the City and Tierney joined Richard Widmark and the rest of the talented cast in one of the two best films Dassin ever made. Kersh, the author of the novel the film was based on, did not agree. Dassin never admitted it until an interview in 2005, but Zanuck had encouraged him to everything in such a rush, he never read the book. Many years later, when he did, he could see why Kersh got mad — Night and the City the movie had no resemblance to Night and the City the novel whatsoever.

I haven't read the novel but if the godawful 1992 film with the same title starring Robert De Niro and Jessica Lange hewed closer to its narrative, I'm glad that I haven't. If, on the other hand, the 1992 Night and the City just provides more evidence that nine times out of 10, when you try to remake a classic film, you only end up with the celluloid equivalent of diarrhea, Kersh should be grateful he died in 1968. I actually saw the disaster of a remake before I ever saw the original and once I saw the original, I couldn't believe that they were supposed to have come from the same source material. When ranking Dassin's films, I'm always torn between Night and the City and Rififi as to which I think is the greatest. Preparing for this tribute, I watched the films on consecutive nights. It's such a close call, but for today anyway, I give Rififi the slight edge. However, that doesn't mean I love Night and the City any less. What a script. What a cast. Every detail done to perfection. "Night and the city. The night is tonight, tomorrow night or any night. The city is London." Those are the words that open the film then we see Widmark's Harry Fabian running like hell through a square — and running will be what he's doing for a lot of the movie when he doesn't slow down long enough to try to make his Greco-Roman wrestling scheme work or to make time for Mary or listen to offers from the likes of Francis L. Sullivan's Philip Nosseross, a nightclub owner who resembles a more genial Jabba the Hutt, or his wife Helen (the wonderful Googie Withers, who just passed away in July), who wants her own action and to escape her husband.

When Night and the City opened in 1950, it depended where you lived what music accompanied Fabian's film-opening sprint. Britain, still recovering from the damage of World War II, had laws in place to ensure that it kept a certain amount of the profits of films made there

and provide workers jobs as well. As a result, there were two versions of Night and the City, and Dassin wasn't allowed to participate in the editing of either one — one because he wasn't British, the other because when he returned to the United States, he was banned from the 20th Century Fox lot. The British cut runs longer, adding some more character scenes, and contains a moodier score by Benjamin Frankel, who would go on to score John Huston's Night of the Iguana and Ken Annakin's Battle of the Bulge. The American cut, which Dassin says he prefers, has music composed by the great and prolific Franz Waxman, who composed many scores for Hitchcock

and provide workers jobs as well. As a result, there were two versions of Night and the City, and Dassin wasn't allowed to participate in the editing of either one — one because he wasn't British, the other because when he returned to the United States, he was banned from the 20th Century Fox lot. The British cut runs longer, adding some more character scenes, and contains a moodier score by Benjamin Frankel, who would go on to score John Huston's Night of the Iguana and Ken Annakin's Battle of the Bulge. The American cut, which Dassin says he prefers, has music composed by the great and prolific Franz Waxman, who composed many scores for Hitchcock including Rear Window as well as Billy Wilder's Sunset Blvd., and previously wrote the music for Dassin's Reunion in France. Waxman uses a variety of styles throughout Night and the City, parts with a jazz tinge, other moments matching the kinetic nature of various chase sequences. I've not seen the entire British version to know how it works, but I know that Nick De Maggio edited the American cut superbly. He also edited Thieves' Highway and would go on to cut another classic Widmark noir, Samuel Fuller's Pickup on South Street. Max Greene was responsible for the great cinematography. Some of the greatest movies seem as if they come into existence by accident. When you consider what a rush job Night and the City was, how Dassin didn't even read the book (though presumably the credited screenwriter Jo Eisinger had), how a role for Gene Tierney had to be created out of thin air and shoehorned into the story at the last minute, how a lot of the roles had to be cast with British actors by law and Dassin didn't know any (one of his casting directors turned out to be Douglas Fairbanks Jr.) and that Zanuck, who liked to meddle with his directors' pictures, didn't reshoot anything or change the editing when he really could have since Dassin was barred from the editing room because of the blacklist, it's a fucking miracle how brilliantly Night and the City turned out. Some things are just fucking meant to be. Even with the character of the huge old Greco-Roman wrestler Gregorious. Dassin drew a picture of a wrestler he'd seen once and said that's how he envisioned the person they got to play the part. Someone recognized the drawing as Stanislaus Zbyszko, but thought he was dead. Another person knew that Zbyszko actually was not only alive but had a farm in Missouri. They contacted him and he ended up playing the part of Gregorious. At a moment of professional and personal crisis for Jules Dassin, the stars truly aligned when it came to Night and the City.

including Rear Window as well as Billy Wilder's Sunset Blvd., and previously wrote the music for Dassin's Reunion in France. Waxman uses a variety of styles throughout Night and the City, parts with a jazz tinge, other moments matching the kinetic nature of various chase sequences. I've not seen the entire British version to know how it works, but I know that Nick De Maggio edited the American cut superbly. He also edited Thieves' Highway and would go on to cut another classic Widmark noir, Samuel Fuller's Pickup on South Street. Max Greene was responsible for the great cinematography. Some of the greatest movies seem as if they come into existence by accident. When you consider what a rush job Night and the City was, how Dassin didn't even read the book (though presumably the credited screenwriter Jo Eisinger had), how a role for Gene Tierney had to be created out of thin air and shoehorned into the story at the last minute, how a lot of the roles had to be cast with British actors by law and Dassin didn't know any (one of his casting directors turned out to be Douglas Fairbanks Jr.) and that Zanuck, who liked to meddle with his directors' pictures, didn't reshoot anything or change the editing when he really could have since Dassin was barred from the editing room because of the blacklist, it's a fucking miracle how brilliantly Night and the City turned out. Some things are just fucking meant to be. Even with the character of the huge old Greco-Roman wrestler Gregorious. Dassin drew a picture of a wrestler he'd seen once and said that's how he envisioned the person they got to play the part. Someone recognized the drawing as Stanislaus Zbyszko, but thought he was dead. Another person knew that Zbyszko actually was not only alive but had a farm in Missouri. They contacted him and he ended up playing the part of Gregorious. At a moment of professional and personal crisis for Jules Dassin, the stars truly aligned when it came to Night and the City.The ensemble does the best job at selling the movie, foremost Widmark as the smooth yet smarmy Fabian. You can see how some people buy into his dreams just as you easily as others see right through him. As Mary's friend Adam (Hugh Marlowe) so accurately describes him, "Harry's an artist without an art." Tierney does fine given that she's playing a role that really has no reason for being there. Herbert Lom manages to be both frightening and unctuous as a crooked wrestling promoter who still has concerns about his father, Gregorious (Zbyszko) when Fabian manages to bring him into the machinations. Above them all though are Sullivan and Withers as Philip and Helen, the husband and wife who don't quite know how they got together but can't figure out a way to split up. When Helen makes plans to pin her exit on Fabian's scheme, Philip warns, "You don't know what you're getting into." Helen knows deep down, but she doesn't care. "I know what I'm getting out of," she tells him. Night and the City, despite the turmoil going on on the outside, is by far the best film Dassin had made until that point. Some good ones will still come, but now he'll face the toughest time of the blacklist.

Tweet

Labels: Astaire, blacklist, Chaplin, D. Zanuck, Dassin, De Niro, Fuller, G. Tierney, Ginger Rogers, Hayden, Hitchcock, Huston, J. Lange, Kazan, Lee J. Cobb, Remakes, Truffaut, Widmark, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Thursday, July 07, 2011

"If You Want to See the Girl Next Door, Go Next Door"

By Eddie Selover

More than anything else, it was a book that turned me into a movie buff: David Shipman’s The Great Movie Stars: The Golden Years. This was the first comprehensive set of star biographies, and in those pre-video days of the early '70s, it told tantalizing tales of films I had no hope of seeing unless they turned up on the late show. Shipman wrote marvelously about many actors and actresses, but maybe too well — his opinions had a way of soaking in. The actors he cared about (Judy Garland, Buster Keaton, Greta Garbo, Deanna Durbin) got love letters, while those he didn’t were pretty much excoriated.

Joan Crawford was one of the latter. The entry on Crawford starts with a putdown by Humphrey Bogart, and Shipman goes on to call her “not much of an actress…as tough as old boots” and to conclude that “she achieved little…her repertory of gestures and expressions was severely limited…(her shoulders) were always so much more eloquent than her face.” And that’s just the introduction. His survey of her career is peppered with words like “artificial,” “heavy,” “monotonous” and “hysterical.” So even before I’d seen most of her work, I was a bit prejudiced against Crawford.