Monday, September 30, 2013

What a ride: Bye bye 'Bad' Part I

that STILL has yet to watch Breaking Bad in its entirety, close this story now.

By Edward Copeland

Kept you waiting there too long my love.

All that time without a word

Didn't know you'd think that I'd forget

Or I'd regret the special love I have for you —

My Baby Blue.

Perfection. I don’t intend (and never planned) to spend much of this farewell to Breaking Bad discussing its finale, but it happens too seldom that a movie or a final episode wraps with the absolute spot-on song. The Crying Game did it with Lyle Lovett singing “Stand By Your Man.” The Sopranos often accomplished it with specific episodes such as using The Eurythmics’ “I Saved the World Today” at the end of the second season’s “Knight in White Satin Armor” episode. Breaking Bad killed last night with some Badfinger — and how often do you read words along those lines?

We first met Walter Hartwell White, his family and associates (or, if you prefer, eventual victims/collateral damage) on Jan. 20, 2008. Viewers anyway. As for the time period of the show, the first scene or that first episode, I’d be a fool to venture a definitive guess. I start this piece with that date because it places the series damn close to the beginning of the 2008 calendar year. In the years since Vince Gilligan’s brilliant creation graced our TV screens, five full years of movies opened in the U.S. and ⅔ of a sixth. In that time, some great films crossed my path. Many I anticipate being favorites for the rest of my days: WALL-E, (500) Days of Summer and The Social Network, to name but three. As much as I love those movies and many others released in that time, I say without hyperbole that none equaled the quality or satisfied me as much as the five seasons of Breaking Bad.

For me to make such a declaration might come off as one more person jumping on the "what an amazing time we live in for quality TV" bandwagon. As someone who from a young age loved movies to such a degree that I sometimes attended new ones just to see something, admitting this amazes even me. On some level, early on in this sea change, it felt as if I not only had cheated on my wife but become a serial adulterer as well. In my childhood days of movie love, I also watched way too much TV, but I admittedly held the medium in disdain as a whole, an attitude that, despite the shows I loved and recognized as great, didn’t change until Hill Street Blues arrived. However, I can’t deny the transfer of my affection as to which medium satisfies, engages and gives me that natural high once exclusive to the best of cinema or, in those all-too-brief years I could attend, superb New York theater productions, most consistently now. It’s not that top-notch movies no longer get made, but experiencing sublime new films occurs far less frequently than in years past. (Perhaps a mere coincidence, but the most recent year that I’d cite as overflowing with works reaching higher heights happens to be 1999 — the same year The Sopranos premiered, marking the unofficial start of this era.) Granted, television and other outlets such as Netflix expanded the number of places available for programming exponentially, television as a whole still produces plenty of time-wasting crap. However, on a percentage basis, the total of fictional TV series produced that rank among the greatest in TV history probably hits a higher number than great films reach out of each year's crop of new movies.

Close readers of my movie posts know that when I compile lists of all-time favorite films, as I did last year, I require that a movie be at least 10 years old before it reaches eligibility for inclusion. With that requirement for film, it probably appears inconsistent on my part to declare Breaking Bad the greatest drama to air on television when it just concluded last night. However, I don’t feel like a hypocrite making this proclamation. When I saw any of the 62 episodes of Breaking Bad for the first time, never once did I feel afterward as if it had just been an “OK” episode. Obviously, some soared higher than others, but none ranked as so-so. I can’t say that about any other series. As much as I love The Sopranos, David Chase’s baby churned out some clunkers. The Wire almost matched Breaking Bad's achievement, but HBO prevented this by giving it a truncated fifth season that forced David Simon and gang to rush the ending in a way that made the final year unsatisfying following its brilliant fourth. Deadwood gets an incomplete, once again thanks to HBO, for not allowing David Milch to complete his five season vision. I recently re-read the one time I wrote about Breaking Bad, sometime in the middle of its third season, and though I didn't hail it to the extent I do now, the impending signs show in my protective nature toward the series since this came

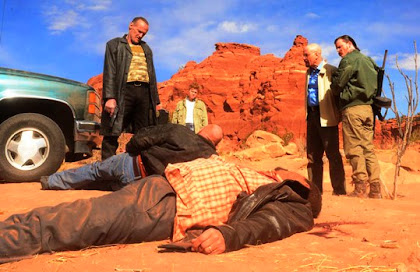

when it had a smaller, loyal cadre of fans such as myself who almost wanted to keep it our little secret. As the series moved forward, what amazed me — something that amazes me anytime it happens — was Breaking Bad’s ability to get better and better from season to season. That rarely occurs on any show, no matter how good. Programs might achieve a level of quality and maintain it, but rarely do any continue to top themselves. The Wire did that for its first four seasons but, as I wrote above, that stopped when HBO shorted them by three episodes in its final season. Breaking Bad not only grew better, it continued to experiment with its storytelling techniques right up to its final episodes. In this last batch of eight alone, we had “Rabid Dog” (written and directed by Sam Catlin) that begins with Walt, gun in hand, searching his gasoline-soaked house for an angry Jesse, whose car remains in the driveway while he can't be found. Then, well into the episode, we pick up where the previous episode ended with Jesse dousing the White residence with the flammable liquid and learn that Hank had tailed him and stopped Pinkman in the act and convinced the angry young man that the enemy of his enemy might be his friend. Then, in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson), the amazing first scene (following the pre-title card teaser scene) at To’hajiilee following the lopsided shootout between Uncle Jack, Todd and their Neo-Nazi gang versus Hank and Gomez, lasts an amazing 13½ riveting minutes. The credits don’t run until after the second commercial break, more than 20 minutes into the episode. Throughout the series, despite being on a commercial network, Breaking Bad never shied away from long scenes (and kudos to AMC for allowing them to do so) such as Skyler and Walt’s rehearsal in season 4’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) for telling Hank and Marie about Walt’s “gambling problem” and how that gave them the money to buy the car wash. The dramas on pay cable that lack commercials seldom provide scenes of that notable length. Fear of the short attention span. With as many channels as exist, I say fuck those fidgety fools. Cater to those who appreciate these scenes when done as well as Breaking Bad did them. That writing surpassed most everything else on TV most of the time and as usual at the Emmys, where I consider it a fluke if someone or something deserving wins, Breaking Bad received no nominations for writing until the two it earned this year (and lost). On Talking Bad following the finale, Anna Gunn compared each new script’s arrival to Christmas morning — and she also worked on Deadwood with a master wordsmith like David Milch.

when it had a smaller, loyal cadre of fans such as myself who almost wanted to keep it our little secret. As the series moved forward, what amazed me — something that amazes me anytime it happens — was Breaking Bad’s ability to get better and better from season to season. That rarely occurs on any show, no matter how good. Programs might achieve a level of quality and maintain it, but rarely do any continue to top themselves. The Wire did that for its first four seasons but, as I wrote above, that stopped when HBO shorted them by three episodes in its final season. Breaking Bad not only grew better, it continued to experiment with its storytelling techniques right up to its final episodes. In this last batch of eight alone, we had “Rabid Dog” (written and directed by Sam Catlin) that begins with Walt, gun in hand, searching his gasoline-soaked house for an angry Jesse, whose car remains in the driveway while he can't be found. Then, well into the episode, we pick up where the previous episode ended with Jesse dousing the White residence with the flammable liquid and learn that Hank had tailed him and stopped Pinkman in the act and convinced the angry young man that the enemy of his enemy might be his friend. Then, in the episode “Ozymandias” (written by Moira Walley-Beckett, directed by Rian Johnson), the amazing first scene (following the pre-title card teaser scene) at To’hajiilee following the lopsided shootout between Uncle Jack, Todd and their Neo-Nazi gang versus Hank and Gomez, lasts an amazing 13½ riveting minutes. The credits don’t run until after the second commercial break, more than 20 minutes into the episode. Throughout the series, despite being on a commercial network, Breaking Bad never shied away from long scenes (and kudos to AMC for allowing them to do so) such as Skyler and Walt’s rehearsal in season 4’s “Bullet Points” (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by Colin Bucksey) for telling Hank and Marie about Walt’s “gambling problem” and how that gave them the money to buy the car wash. The dramas on pay cable that lack commercials seldom provide scenes of that notable length. Fear of the short attention span. With as many channels as exist, I say fuck those fidgety fools. Cater to those who appreciate these scenes when done as well as Breaking Bad did them. That writing surpassed most everything else on TV most of the time and as usual at the Emmys, where I consider it a fluke if someone or something deserving wins, Breaking Bad received no nominations for writing until the two it earned this year (and lost). On Talking Bad following the finale, Anna Gunn compared each new script’s arrival to Christmas morning — and she also worked on Deadwood with a master wordsmith like David Milch. Looking again at the initial moments of Breaking Bad, now viewed with the knowledge of everything to come, it establishes much about Walter White even though it occurred before Heisenberg made any official appearance. Watch this clip of our introduction to both Walt and Breaking Bad and see what I mean.

From the beginning, all the elements of Walt’s delusions had planted their roots in his head: the denial of criminality, his conviction that his family justified all his actions (which, compared to what events transpire later, seem rather minor moral transgressions now). One thing I wondered: Did Hank hang on to that gas mask somewhere in DEA evidence? It had Walt's fingerprints on it since he flung it away bare-handed. If Jesse told Schrader where they began cooking, hard evidence for a case existed and things might have turned out differently. Oh, well. No use crying over spilled brother-in-laws at this point. Dipping in and out of the AMC marathon preceding the finale and watching and re-watching episodes over the years (because, among the other outstanding attributes of Breaking Bad, the show belongs on the list of the most compulsively re-watchable television series in history), I always look for the exact moment when Heisenberg truly dominated Walter White’s personality because while I’m not in any way excusing Walt’s actions the way the deranged Team Walt types do, obviously this man suffers from a split personality disorder. You spot it in the season 2 episode where they hold the celebration party over Walt's cancer news and he keeps pouring tequila into Walt Jr.'s cup until Hank tries to put a stop to it, prompting a confrontation that mirrors in many ways Hank and Walt's after Hank deduced his alter ego. It also contains dialogue where Walt apologizes in the morning, saying, "I don't know who that was yesterday. It wasn't me." What caused that split, we don’t really know. We know that Walt’s dad died of Huntington’s disease when White was young and Skyler alluded to the way “he was raised” when he resisted accepting the Schwartzes’ help paying for his cancer treatments in the early days and he has no apparent relationship with his mother. Frankly, I praise creator Vince Gilligan for not taking that easy way out and trying to explain the cause of Walter White’s madness. I find it more interesting when creators don’t try to explain what made their monsters. I didn’t need to know that young Hannibal Lecter saw his parents killed by particularly ghoulish Nazis in World War II who ate his parents. Hannibal's character remains more interesting without some traumatic back story to explain what turned him into the serial killer he became. Since I brought up

those Team Walt members, while I can't conceive how anyone still defends him, I understand how people sympathized with Walter White at first and it took different actions and moments in the series for individual viewers to accept the fact that no classification fit Walter White other than that of a monster. In the beginning, the series made it easy to feel for Walt and cheer him on. When he took action on the asshole teens mocking Walt Jr. for his cerebral palsy, who didn't think those punks deserved it? While an excessive act, when he fried the car battery of the asshole who stole his parking space, who hasn't fantasized about getting even on someone like that? Even when Walt's acts got more serious, you sided with him, such as when he bawled, sobbing "I'm sorry" repeatedly as he killed Krazy-8. Even the moment most cite as the breaking point as Walt watches Jane die plays as open to interpretation. He looks like a deer in the headlights, uncertain of what to do as much as someone who sees the advantage of letting this woman in the process of extorting him expire. The credit for that ambiguity belongs to the brilliance of Bryan Cranston's performance. However, once you get to that final season 4 reveal of the Lily of the Valley plant, I don't see how anyone defended Walt after that, if they hadn't stopped already. As Hank said at the end, Walt was the smartest guy he ever met, so why couldn't he devise a way to either save himself or kill Gus that didn't involve poisoning a child?

those Team Walt members, while I can't conceive how anyone still defends him, I understand how people sympathized with Walter White at first and it took different actions and moments in the series for individual viewers to accept the fact that no classification fit Walter White other than that of a monster. In the beginning, the series made it easy to feel for Walt and cheer him on. When he took action on the asshole teens mocking Walt Jr. for his cerebral palsy, who didn't think those punks deserved it? While an excessive act, when he fried the car battery of the asshole who stole his parking space, who hasn't fantasized about getting even on someone like that? Even when Walt's acts got more serious, you sided with him, such as when he bawled, sobbing "I'm sorry" repeatedly as he killed Krazy-8. Even the moment most cite as the breaking point as Walt watches Jane die plays as open to interpretation. He looks like a deer in the headlights, uncertain of what to do as much as someone who sees the advantage of letting this woman in the process of extorting him expire. The credit for that ambiguity belongs to the brilliance of Bryan Cranston's performance. However, once you get to that final season 4 reveal of the Lily of the Valley plant, I don't see how anyone defended Walt after that, if they hadn't stopped already. As Hank said at the end, Walt was the smartest guy he ever met, so why couldn't he devise a way to either save himself or kill Gus that didn't involve poisoning a child?With all that said, Walt, while not redeemed, did rightfully regain some sympathy in the home stretch — surrendering his precious ill-gotten gains in a fruitless plea for Hank’s life, trying to clear Skyler of culpability, ultimately freeing Jesse and, most importantly, admitting that all his evil deeds had nothing to do with providing for his family but were because he enjoyed them, they made him feel alive. Heisenberg probably left that drink unfinished at the New Hampshire bar, but I think the old Walter White returned. The people he harmed deserved it and the scare he put in Elliot and Gretchen Schwartz merely a fake-out to ensure they did what he wanted with the money. He didn’t break good at the end, but he tied up loose ends and then allowed himself to die side by side with his true love — the blue meth he created that rocked the drug-addicted world.

Alas, my physical limitations prevent me from giving the series the farewell I envisioned in a single tribute, so I must break this into parts as much remains to be discussed — I’ve yet to touch upon the magnificent array of acting talent, brilliant direction and tons of other issues so, while Breaking Bad’s story has ended, this one has not. So, regretfully, as I collapse, I must say…

Tweet

Labels: Breaking Bad, Cranston, David Chase, David Simon, Deadwood, Hannibal Lecter, HBO, Milch, Netflix, The Sopranos, The Wire, Theater, TV Tribute

Comments:

<< Home

BB has been addictive and it has been head and shoulders over any other TV (now or past)

But the seasons did not get better and better. S1,2,3 were the pinnacle.

S4 lost it's edge - it felt like too much melodrama crept in. A little overbaked if you forgive the pun.

S5a was mostly drab. Everything was predictable and the characters hardly did anything. The only decent bits were the flash-forward in the 501 and the last episode 508, when it finally picked up the pace.

S6b redeemed itself. Where 5a felt like the writers took a year off to party, 5b is where they came back and meant business once again, thank goodness. But it was not a perfect season. I found Jesse's melancholy and irrationality overdone and it detracted. Unfortunately there were only 8 episodes to get to Vinces target of tying everything up, and the runway wasnt long enough. If only they got serious in 5a we would have had a masterpiece. Overall 5a+5b redeemed itself to be on par with 4.

But the seasons did not get better and better. S1,2,3 were the pinnacle.

S4 lost it's edge - it felt like too much melodrama crept in. A little overbaked if you forgive the pun.

S5a was mostly drab. Everything was predictable and the characters hardly did anything. The only decent bits were the flash-forward in the 501 and the last episode 508, when it finally picked up the pace.

S6b redeemed itself. Where 5a felt like the writers took a year off to party, 5b is where they came back and meant business once again, thank goodness. But it was not a perfect season. I found Jesse's melancholy and irrationality overdone and it detracted. Unfortunately there were only 8 episodes to get to Vinces target of tying everything up, and the runway wasnt long enough. If only they got serious in 5a we would have had a masterpiece. Overall 5a+5b redeemed itself to be on par with 4.

Of course, the dirty secret behind splitting final seasons and calling them the same season (a trick that started with HBO and Sex and the City, then The Sopranos) is that not only do the networks get to milk their hits a little longer but by calling sets of episode divided by a year part of the same season, they don't have to give anyone (cast or crew) raises.

Post a Comment

<< Home