Tuesday, April 12, 2011

It's easy to make fun of somebody if you don't care how much you hurt them

By Edward Copeland

In the early years of the Academy Awards, repeat winners happened not only frequently but often soon after previous wins, sometimes even consecutively. For example, Frank Capra took home the directing prize three times, winning every other year from 1934 through 1938, starting with the great It Happened One Night and ending with You Can't Take It With You. The second Oscar between the two came for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, which marks its 75th anniversary today, and was the only film of the three not to also win best picture. More importantly, the movie proved to be the wonderful Jean Arthur's breakthrough.

Now Capra has a reputation as the corniest of filmmakers, a reputation I believe is a bit unfair when you look at the darkness in some of his films such as It's a Wonderful Life or Mr. Smith Goes to Washington or especially at the more unusual titles in his filmography such as The Miracle Woman or The Bitter Tea of General Yen, both starring Barbara Stanwyck. Of the films that do lead to that reputation though, Mr. Deeds might be one that's near the head of that pack. Not that Mr. Deeds isn't a good film, even if it isn't up to the level of the best Capras such as It Happened One Night, Mr. Smith and Wonderful Life, but it still holds up today as a fairly solid entertainment, if it's a tad overlong.

The story begins as we see a car take an explosive plunge off a mountain road followed by a newspaper headline announcing the death of financier Matthew Semple in Italy. In New York, his attorneys,

led by John Cedar (Douglas Dumbrille), has a team of investigators including press agent Cornelius Cobb (the delightful Lionel Stander, known to generations decades later as Max on the '70s TV show Hart to Hart), scouring the world for Semple's heir. This part seems a little confusing because apparently Semple left a will that named his heir and though there are other relatives he disdained (Jameson Thomas, Mayo Methot), it would seem all they had to do was find him, even if Matthew Semple himself had never met him. Finally, they connect the dots and identify him as one Longfellow Deeds (Gary Cooper), resident of Mandrake Falls, Vt. Soon, Cedar, Cobb and the crew are en route to meet the new rich man. Cedar, head of his firm Cedar, Cedar, Cedar and Buddington, finds himself particularly anxious to get a feeling for Deeds because he hopes to woo power of attorney from him to use part of the fortune he's inherited to help pay off some of the firm's debts.

led by John Cedar (Douglas Dumbrille), has a team of investigators including press agent Cornelius Cobb (the delightful Lionel Stander, known to generations decades later as Max on the '70s TV show Hart to Hart), scouring the world for Semple's heir. This part seems a little confusing because apparently Semple left a will that named his heir and though there are other relatives he disdained (Jameson Thomas, Mayo Methot), it would seem all they had to do was find him, even if Matthew Semple himself had never met him. Finally, they connect the dots and identify him as one Longfellow Deeds (Gary Cooper), resident of Mandrake Falls, Vt. Soon, Cedar, Cobb and the crew are en route to meet the new rich man. Cedar, head of his firm Cedar, Cedar, Cedar and Buddington, finds himself particularly anxious to get a feeling for Deeds because he hopes to woo power of attorney from him to use part of the fortune he's inherited to help pay off some of the firm's debts.

When the New Yorkers arrive in Mandrake Falls, they soon realize they aren't in Manhattan anymore. The station agent (Spencer Charters) turns out to be a very friendly chap, but people in Mandrake Falls have a tendency to be so literal that it takes awhile to get out of them the information you seek. Cedar's party get him to admit he knows Longfellow Deeds and that Deeds is very friendly and will talk to anybody but it takes about the third try, thanks to Cobb, to ask the correct question and ask if the man could take them to where Deeds resides, to which the station agent wonders why they didn't just say that in the first place. Of course, being literal, the man takes them to Deeds' home, but he also knew they wouldn't find Deeds there then because they didn't ask specifically to be taken to Deeds and are greeted only by his housekeeper (Emma Deems). They ask her if Deeds might be married, but she tells them no, he's waiting to rescue a lady in distress. Fortunately, the wait to meet Deeds

himself isn't too terribly long and Longfellow Deeds finally walks in the door (and grabs his tuba, seemingly out of habit). Cedar explains to him that Matthew Semple has left him his fortune and wonders if he knows how he's related. Deeds says that his mother's maiden name was Semple and he thinks he might have been his uncle. He then learns the amount: $20 million. That's quite a lot, he says. "It'll do in a pinch," Cobb says. Out of curiosity, they ask Deeds what he does and he informs them that he writes poems for postcards for special occasions such as Christmas, Easter, Mother's Day, etc. They tell him they need him to go back to New York with them to make all the arrangements, but Deeds already makes noises about how he doesn't need all that money and he'll probably give it away. Cobb asks the housekeeper what she thinks about her boss getting $20 million, but she's more concerned about how many people are staying for lunch. Deeds recommends they stay, just to try her orange layer cake.

himself isn't too terribly long and Longfellow Deeds finally walks in the door (and grabs his tuba, seemingly out of habit). Cedar explains to him that Matthew Semple has left him his fortune and wonders if he knows how he's related. Deeds says that his mother's maiden name was Semple and he thinks he might have been his uncle. He then learns the amount: $20 million. That's quite a lot, he says. "It'll do in a pinch," Cobb says. Out of curiosity, they ask Deeds what he does and he informs them that he writes poems for postcards for special occasions such as Christmas, Easter, Mother's Day, etc. They tell him they need him to go back to New York with them to make all the arrangements, but Deeds already makes noises about how he doesn't need all that money and he'll probably give it away. Cobb asks the housekeeper what she thinks about her boss getting $20 million, but she's more concerned about how many people are staying for lunch. Deeds recommends they stay, just to try her orange layer cake.

Mandrake Falls gives their newly wealthy son a huge sendoff — so big that the New York delegation loses Deeds and the train already has arrived. Finally they spot him. It seems he's playing his tuba with the band for the last time. When he gets on the train, he looks rather forlorn, but Cedar tries to reassure that he has nothing to worry about in regard to the fortune. Deeds tells him it's not the money that he's fretting about — he just hopes the band can find another tuba player. While Deeds is en route to New York, the wife of the other Semple henpecks her sniveling husband to do whatever possible to get what's rightfully theirs, even if Matthew Semple hated his guts. The size of Semple's mansion leaves Deeds in awe, though Cedar and the rest keep him so occupied, he fears he won't get to see sites such as Grant's Tomb and the Statue of Liberty, which he really wants to since he is in New York. Once he is in town, the newspapers salivate at the chance to cover this new millionaire and MacWade (George Bancroft), the editor of one newspaper, gathers his best reporters

in his office to tell them they have to get to the bottom of this Longfellow Deeds and make him a sensation. Among the reporters listening to the pitch is MacWade's shining star, Pulitzer Prize winner Louise Bennett (Jean Arthur), who spends most of the scene playing with a string which I think could be a yo-yo, but couldn't tell for sure. She promises him a front page story if as a reward she receives a raise and a month of paid vacation. MacWade agrees and Louise, known as Babe to her fellow reporters, takes the assignment, having been clued in to the idea that Deeds longs to find a woman in distress. Back at the mansion, Cedar continues to try to get Deeds to hire him as do many others. Deeds seems puzzled as to why so many people offer to work for him for nothing. One lawyer named Hallor (Charles Lane) does seek something, though Cedar tries to get him thrown out. He tells Deeds he represents Matthew Semple's common-law wife and that a child is involved and that entitles her to a third of the estate. Deeds thinks that's reasonable and adds up to about $7 million — until Hallor says he's willing to settle for $1 million. That convinces Deeds that if he's willing to take that much less than he's owed, he must be a fraud and physically tosses him out. Cedar tells him that's why he needs to hire him — to protect him from people like that, but Deeds says he hasn't decided if he's hiring him yet.

in his office to tell them they have to get to the bottom of this Longfellow Deeds and make him a sensation. Among the reporters listening to the pitch is MacWade's shining star, Pulitzer Prize winner Louise Bennett (Jean Arthur), who spends most of the scene playing with a string which I think could be a yo-yo, but couldn't tell for sure. She promises him a front page story if as a reward she receives a raise and a month of paid vacation. MacWade agrees and Louise, known as Babe to her fellow reporters, takes the assignment, having been clued in to the idea that Deeds longs to find a woman in distress. Back at the mansion, Cedar continues to try to get Deeds to hire him as do many others. Deeds seems puzzled as to why so many people offer to work for him for nothing. One lawyer named Hallor (Charles Lane) does seek something, though Cedar tries to get him thrown out. He tells Deeds he represents Matthew Semple's common-law wife and that a child is involved and that entitles her to a third of the estate. Deeds thinks that's reasonable and adds up to about $7 million — until Hallor says he's willing to settle for $1 million. That convinces Deeds that if he's willing to take that much less than he's owed, he must be a fraud and physically tosses him out. Cedar tells him that's why he needs to hire him — to protect him from people like that, but Deeds says he hasn't decided if he's hiring him yet.

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town wasn't just the breakthrough role for the delightful Jean Arthur, who hadn't made much of an impression before that, it also was a lucky break that she got the role in the first place. Originally, Capra wanted Carole Lombard to play the part but at the last minute, Lombard opted to make My Man Godfrey instead. In fact, Mr. Deeds being made when it was was an accident as well. Capra had planned for Lost Horizon to be his next film, but Ronald Colman had other commitments, so he moved Mr. Deeds up. Thank goodness for fate because what a less rich cinematic world we'd have if Arthur hadn't received that break and been able to delight us as much as she would. Her character Babe assumes the false identity of Mary Dawson and after Deeds sneaks out (having to lock his bodyguards in a room) she fakes a fainting spell in front of the mansion so Longfellow can come to the rescue. He takes her to a restaurant where writers and poets supposedly congregate, unaware she has photographers tailing them.

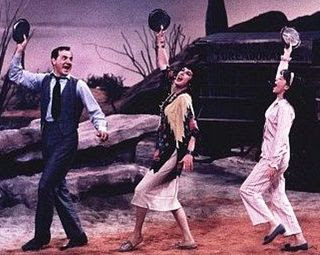

The poet in Deeds keeps looking for fellow writers and the waiter directs him to a table full of them, all of whom seem intent on making fun of him and Deeds knows they are doing it. In particular, one of his favorite poets, Brookfield (Eddie Kane), seems intent on trying to treat Longfellow as a rube. "I think your poems are swell Mr. Brookfield, but I'm disappointed by you," Deeds tells him, to no apparent effect. "I know I must look funny to you, but maybe if you went to Mandrake Falls, you'd look funny to us, only nobody would laugh at ya and make you feel ridiculous." He also tells him that if it weren't Miss Dawson being present, he'd bump their heads together, but she says she doesn't mind and Deeds proceeds to pummel the poets, only he misses one. Morrow (a hilarious bit by Walter Catlett) comes to him begging for a hit on the chin. "What a magnificent displacement of smugness. You've added 10 years to my life," a very drunken Morrow tells Deeds and proceeds to tell him all the things he should show him in the world, constantly

starting to tip backward and having Deeds pull him back upright by his tie. "You hop aboard my magic carpet and I'll show you sights that you've never seen before," Morrow tells him, suggesting they go on a binge and Deeds, who has never touched alcohol in his life, agrees. Needless to say, it gives Babe one helluva story for the paper, where she christens him Cinderella Man and tells of him feeding doughnuts to a horse and when asked why, Deeds saying he was seeing how many the horse would eat before asking for coffee. When he wakes up with a hangover the next morning, his butler Walter (Raymond Walburn) tells him he had quite a bender, but Deeds denies it, saying that Morrow said they were only going on a binge, they never got to a bender. He asks him to get Mary's number out of his pants, but Walter says he can't because he came home without pants. Deeds finds that unbelievable: If he was running around the streets without pants, the police would have picked him up. Walter informs him that it was the police who brought him home. Cornelius brings him the paper, telling him he can't go around punching people like he did at the restaurant. "Sometimes it's the only solution," Deeds insists.

starting to tip backward and having Deeds pull him back upright by his tie. "You hop aboard my magic carpet and I'll show you sights that you've never seen before," Morrow tells him, suggesting they go on a binge and Deeds, who has never touched alcohol in his life, agrees. Needless to say, it gives Babe one helluva story for the paper, where she christens him Cinderella Man and tells of him feeding doughnuts to a horse and when asked why, Deeds saying he was seeing how many the horse would eat before asking for coffee. When he wakes up with a hangover the next morning, his butler Walter (Raymond Walburn) tells him he had quite a bender, but Deeds denies it, saying that Morrow said they were only going on a binge, they never got to a bender. He asks him to get Mary's number out of his pants, but Walter says he can't because he came home without pants. Deeds finds that unbelievable: If he was running around the streets without pants, the police would have picked him up. Walter informs him that it was the police who brought him home. Cornelius brings him the paper, telling him he can't go around punching people like he did at the restaurant. "Sometimes it's the only solution," Deeds insists.

Eventually, with Cedar getting nowhere getting his hands on Deeds' money, he decides to represent the other relatives and try to get Longfellow declared insane, especially after a down-on-his-luck farmer (John Wray) comes into the mansion with a gun and then breaks down and it gives Deeds the idea to give away his fortune to people who apply for farm land and tend to it with equipment he buys for them and, if they produce, they own it after three years. Meanwhile, Cornelius learns Babe's true identity AFTER Deeds has proposed and she's begun to feel so guilty, she's quit her job because she's fallen for him. It's really the back half where the sentimentality overwhelms the comedy, but it's still good and you do get the Faulkner sisters (Margaret McWade, Margaret Seddon) to come from Mandrake Falls to testify that Deeds always has been "pixilated," but then who among us isn't pixilated?

Cooper does have some good moments, but he's stiff as he often is in just about any film he made, though it did earn him his first Oscar nomination, but with Arthur and the great comic supporting cast, especially Stander, it doesn't interfere. Probably his most timely speech comes in his sanity hearing when he asks why should he be considered crazy if he'd rather see the money go to be people who need it. "It's like I'm out in a big boat, and I see one fellow in a rowboat who's tired of rowing and wants a free ride, and another fellow who's drowning. Who would you expect me to rescue? Mr. Cedar — who's just tired of rowing and wants a free ride? Or those men out there who are drowning? Any 10-year-old child will give you the answer to that," Deeds tells the judge. Sounds like an accurate depiction of today's corporate and wealthy-favored government to me. Capra's pacing lags at time, but he does have some nice directing touches, my favorite being when Deeds is institutionalized and Cornelius urges him to fight. Capra films the entire scene in darkness with the actor silhouetted and begins it with a nice zoom.

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town is a lesser Capra, but it remains worthwhile even if he lays its message of the value of honesty, sincerity and decency on a bit too heavily.

Tweet

Labels: 30s, Capra, Cooper, Jean Arthur, Lombard, Movie Tributes, Oscars, R. Colman, Stanwyck

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, April 11, 2011

“You’re one person against the world unless you have somebody…and then it’s only half as hard…”

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

After spending some 30 years in show business strutting and fretting upon the stage, Savannah, Ga., native Charles Douville Coburn decided to try his luck in the “flickers”…and though his first onscreen appearance can be traced back to 1933, it wasn’t until his breakout performance in 1938’s Of Human Hearts that Coburn soon was able to establish himself as one of the most dependable character presences in motion pictures. His slightly stuffy and aristocratic bearing made him the ideal person to play overbearing fathers, shady con men or wealthy millionaires in screwball comedies such as Vivacious Lady (1938) and Bachelor Father (1939), and he later distinguished himself in classics such as The Lady Eve (1941) and Heaven Can Wait (1943). He would continue to entertain audiences in the 1950s in scene-stealing roles like those in Howard Hawks’ Monkey Business (1952) and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) until his death in 1961, and even though he’s mostly remembered for his frequent forays into cinematic mirthmaking he also possessed the necessary range to tackle dramatic parts in movies such as Kings’ Row (1941; in which he plays an evil physician who causes co-star Ronald Reagan to famously emote “Where’s the rest of me?”), In This Our Life (1942) and Wilson (1944).

Coburn was nominated three times for an Academy Award by his acting peers and snagged a statuette for 1943’s The More the Merrier, playing a fusty businessman who takes advantage of the housing shortage in the nation’s capital to romantically bring together co-stars Jean Arthur and Joel McCrea. It was Coburn’s second time out working with Arthur, and while Merrier has a number of devotees proclaiming it as a screwball classic I’ve never been particularly taken with the film — in fact, I think Chuck should have received the coveted Oscar trophy for his first supporting actor nomination…and first onscreen teaming with Jean. That film debuted in motion picture theaters 70 years ago today —the delightful comedic romp known as The Devil and Miss Jones (1941).

Cantankerous multimillionaire J.P. Merrick (Coburn) becomes enraged at the sight of a photo plastered on the front page of The New York Times that shows him being hung in effigy by some disgruntled employees of Neeley’s Department Store — an outfit he could have sworn he had ordered sold years before. The unhappy Neeley drones are determined to form a union, and in order to head off that sort of labor radicalism Merrick hires a detective (Robert Emmett Keane) to go undercover as an employee and report back to him on their organizing activities. But Merrick finds himself having to take on the identity of the detective himself, and upon being hired by Neeley’s is dressed down by one of the store’s managers (Edmund Gwenn) and assigned to sell slippers in the store’s children’s shoes section. Co-worker Mary Jones (Arthur) tries to offer him encouragement and boost his morale…and when she thinks that his refusal to take a lunch period is due to his not having any money to buy any (Merrick has a nervous stomach) she lends him 50 cents for food. It also is at this time that faux employee Merrick is introduced to Mary’s fellow worker in the department, Elizabeth Ellis (Spring Byington), who develops a romantic interest in Merrick, even to the point of sharing her lunch with him (tuna fish popovers!).

Having worked his way into Mary and Elizabeth’s good graces, Merrick goes with the two women to a meeting headed up by Mary’s rabble-rousing boyfriend, Joe O’Brien (Robert Cummings), who stresses the need to organize and form a union because Neeley employees are unfairly dismissed once their wages exceed those of new hires. Mary stands up at the meeting and tells all those assembled about Merrick (whose assumed name is “Tom Higgins”): how he was embarrassed about not having any money for lunch and how after she floated him the 50-cent loan refused to buy any (apparently needing it for other things). Merrick is a bit uncomfortable at being the focus of attention but realizes that it provides him with a further opportunity to spy on the discontented workers. He’s confident that his cover won’t be blown because he lives a rather reclusive existence (and hasn’t been photographed in 20 years), his every need mostly attended to by his faithful manservant George (S.Z. “Cuddles” Sakall).

Merrick is invited to spend the day at Coney Island with Mary, Joe and Elizabeth and the extended face time he’s spending with the trio begins to soften his shell; he doesn’t particularly like Joe but when the young man defends him in front of several policemen who’ve picked Merrick up for trying to sell a watch (Merrick can’t remember in which bathhouse his street clothes are in and was attempting to vend the timepiece in order to scare up some pay phone change and call George to come and get him) he begins to understand just what Mary sees in her soul mate. Merrick also begins to grow quite fond of Elizabeth but when she vocally expresses reservations about marrying a man with money he becomes concerned how she’ll react once she learns who he really is.

Such a moment comes sooner rather than later when Merrick accidentally leaves behind a card during a subway ride home signifying that “Higgins,” the detective he’s impersonating, is to be given special treatment — Mary reads the card and upon further investigation learns that “Higgins” is a spy for the store. But she’s still in the dark that Merrick is Merrick, and when she and Joe are threatened by Neely’s general manager (Walter Kingsford) with termination because of their organizing activities Merrick agrees to side with them against management, having been educated a little more about good business practices and employee relations through his personal experiences.

The part of J.M. Merrick is the kind of role in which Charles Coburn excelled; a dyspeptic crabapple whose conservative worldview undergoes a radical change (and I’ll get to the “radical” part in a minute) once he’s climbed down from his ivory tower and learned that employees aren’t just raw materials or commodities but living, breathing hard-working human beings often forced to do whatever they can to pay the bills and put groceries on the table. Much of the humor in The Devil and Miss Jones comes from how Merrick is considered just another worker ant in the store and is treated with great discourtesy; at one point during the film when Mary pleads with him not to fret about these indignities but to just push them away. He replies: “I’m an elephant, Miss Jones — a veritable elephant. I never forget a good deed done me or an ill one. I consider myself a kind of divine justice — other people in this world have to forget things...I do not.”

Much of the slings and arrows suffered by Merrick originate from Gwenn’s general manager (“Hooper”), who in one sequence embarrasses Merrick by taking over a potential sale of shoes to the father of a little girl who acts up in the store — unaware that both girl and father work for Merrick (the “dad” is faithful retainer George). Mary convinces Merrick to swallow his pride and attempt a truce with Hooper by being a big man about losing the sale…but the general manager capitalizes on this opportunity to make Merrick feel even smaller. Unable to hold his temper, Merrick tells Hooper: “I have a hunch those shoes are coming back.” Hooper haughtily informs Merrick “My sales never come back,” prompting Merrick to retort: “Wanna bet?”

It’s always difficult for me to write objectively about actress Jean Arthur because I’m a dyed-in-the-wool devotee of her work, but Miss Jones is one of my favorites of her vehicles and she establishes the reason for this from the get-go by making the titular female a truly sympathetic character…beginning with her “pep talk” to Coburn that his being assigned to slipper detail in the department is actually a plus because the job is pretty cushy (no bending down or running back and forth for shoeboxes). Her maternal instincts kick in when Merrick waves off taking a lunch and she loans him half-a-buck for some sustenance (which he dutifully notes in a record book he’s keeping of his store experiences) and she later stands up at the organizing meeting (after explaining that this is the first time she’s ever spoken publicly) to decry how the store treats its elderly employees (with Merrick as her example). There is a great deal of comedy in this, because we know Merrick is not who he claims to be, but you also develop an admiration for Arthur’s character because she’s not afraid to speak out (in those mellow chirpy, throaty tones) when confronted by injustice.

Coburn and Arthur’s scenes are among the highlights of Miss Jones, particularly a sequence where the two find themselves alone at Coney Island (well, as alone as two can be with a crowd constantly milling about around them) and she tells him of her devotion and affection to boyfriend Cummings despite Coburn’s skepticism. But Coburn has an amazingly swell rapport with Byington, too; the scene where she introduces him to her homemade concoction of “tuna fish popovers” is disarmingly charming. Gwenn’s general manager is sort of Coburn’s rival for Spring’s affections, which sort of made me chuckle because I couldn’t help but think of the two actors’ similar competition for Byington in the 1950 film Louisa.

Bob Cummings completes the star quartet of The Devil and Miss Jones, and although I’ve always considered him the cinematic equivalent of prickly heat he’s actually pretty good here in the first of his multiple teamings with Coburn — the two men would later go on to appear together in Kings’ Row, Princess O’Rourke (1943) and How to Be Very, Very Popular (1955). In fact, when I watch Miss Jones I often marvel at how Coburn and director Sam Wood put politics aside because Cummings’ character’s political leanings are a little on the “pinkish” side, and both Charlie and Sam were members-in-good-standing (Sam served as president of the outfit; Charlie was a one-time veep) of the right-wing Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. The Alliance got its act together in 1944, so maybe the sly and subversive screenplay by ace scribe Norman Krasna (which in addition to Coburn’s performance also garnered an Academy Award nomination) had some influence on them, I can’t really say. But don’t let this backstory dissuade you from watching this classic film comedy, a movie whose politics may date a tad but which contains fine performances not only from the ones already named but additionally fine turns from William Demarest (I just wish Bill had a little more screen time; his role as a store detective is a bit skimpy), Montagu Love, Richard Carle, Charles Waldron, Edwin Maxwell, Florence Bates, Regis Toomey and Matt McHugh. (And for the OTR fans that followed me over from Thrilling Days of Yesteryear, Walter Tetley has a blink-and-you’ll-miss it bit as a stock boy!) But don’t confuse this film with 1973’s The Devil in Miss Jones…because if you do you’re in for a different kind of moviegoing experience entirely.

Tweet

Labels: 40s, Hawks, Jean Arthur, Joel McCrea, Movie Tributes, Oscars

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, December 13, 2010

Centennial Tributes: Van Heflin

By Ivan G. Shreve, Jr.

In 1984, despite my father’s strenuous objections that a VCR was a “luxury and not a necessity” I purchased my very first VHS videocassette recorder with a bonus I received from my place of employment. As a movie buff, I was pretty jazzed at the thought of being able to record films for the purpose of building a library so that I wouldn’t have to wait until the next time a favorite came on — I had even purchased several dozen videocassettes from the public domain bins at our local Wal-Mart in anticipation of eventually investing in a VCR.

One of the first movies I taped was one of my all-time favorite Westerns — 1957’s 3:10 to Yuma, in which a notorious outlaw played by Glenn Ford is kept under guard by a man who’s so desperate for the $200 he’s being paid (he plans to use the money to buy water for his drought-stricken ranch) that he vows nothing will keep him from making sure Ford is put on a train that will take the two of them to the titular city…even though Ford’s gang outnumbers him and is planning to gun him down the minute he sticks his head out of the hotel in which they’ve hid. The actor playing this man who remains courageous in the face of overwhelming odds was born on this date 100 years ago today, and would not only become one of finest stage and screen actors of his generation but gain an enthusiastic fan of his work in myself long after his death in 1971: Van Heflin.

Emmett Evan “Van” Heflin, Jr. was born in Walters, Okla., in 1910 to Fannie and Dr. Emmett Heflin, Sr. — the senior Heflin being a dentist. Schooled in Oklahoma in his formative years, Heflin relocated in California after his parents separated and upon graduating from high school, answered the siren song of the sea by shipping out on a tramp steamer for a year of nautical adventure. He returned to Oklahoma in pursuit of a law degree but two years into his studies found himself yearning for salt air and sea spray once more — a pastime that would remain with him for the rest of his life.

Since childhood, Van also expressed an interest in acting, and made his stage debut in the late 1920s in a performance of Channing Pollock’s Mister Moneypenny. When that play folded after 61 performances, Heflin returned to his lady love, spending the next three years sailing up down the Pacific. After that, it was back to the footlights for a series of various short-lived stage productions until he finally landed a plum assignment in S.N. Behrmann’s End of Summer in 1936. That was also the year he made his film debut alongside Katharine Hepburn in A Woman Rebels; a job that won him a contract with RKO and led to roles in such B-pictures as The Outcasts of Poker Flat (1937), Flight from Glory (1937), Annapolis Salute (1937) and Saturday’s Heroes (1937).

Heflin’s Woman co-star Katharine Hepburn requested that he play the part of reporter Macaulay Connor in her successful stage triumph of The Philadelphia Story — but unfortunately, MGM cast Van aside in favor of James Stewart in the 1940 film version. It wasn’t a total loss for the actor, however; he got a contract with the studio out of it and began to make more movie appearances along the lines of The Feminine Touch (1941) and H.M. Pulham’s Esq. (1941). His third assignment for Leo the Lion cast him as the alcoholic, Shakespeare-spouting buddy of gangster Robert Taylor in Johnny Eager, which received a December 1941 premiere but didn't get wide release until the following year and ended up nabbing him the 1942 best supporting actor Oscar. His film career, however, did not end up suffering beneath the “Oscar curse”; although he was still making appearances in B-pictures such as Kid Glove Killer (1942) and Grand Central Murder (1942), MGM began grooming him for leading man roles — notably Tennessee Johnson (1942), an entertaining (if wildly inaccurate) biopic of the 17th president of the United States, Andrew Johnson.

Heflin’s career on the big screen took a brief hiatus during World War II to allow him to “do his bit” — though he didn’t completely stray from the business; he served as a combat cameraman with the Motion Picture Unit and also the Ninth Air Force in Europe. But he returned to pictures in 1946 with The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, a crime melodrama that featured Barbara Stanwyck, Lizabeth Scott and, in his film debut, Kirk Douglas. In Ivers, Van played the part of Sam Masterson, a vagabond whose return to his home town threatens to expose a hidden secret kept between old flame Babs and her D.A. husband Kirk (this time it was his turn to play the drunk). Ivers would establish Heflin as a frequent participant in the film style labeled by the French as “film noir”; his other films in this vein included Possessed(1947), Act of Violence (1948) and The Prowler (1951). The latter two would feature two of the actor’s most memorable performances: Violence cast him as an ex-GI-turned-successful-businessman who finds himself being stalked by a slightly unhinged Robert Ryan (also an ex-GI). In Prowler, Heflin is an ambitious cop who kills the husband of a wealthy woman (Evelyn Keyes) and then marries her in a twisted pursuit of the American Dream. Heflin’s noir credentials would even stretch over to radio; he played Raymond Chandler’s famous shamus Philip Marlowe in a summer series over NBC Radio in 1947 that, as a lifetime OTR fan, I think was superior to the better-known 1948-51 CBS version with Gerald Mohr.

As an actor, Van Heflin displayed a tremendous range and versatility — he demonstrated an ease and comfort in musicals (Presenting Lily Mars, Till the Clouds Roll By), costume pieces (The Three Musketeers, Madame Bovary) and dramas (B.F.’s Daughter, East Side, West Side).

In 1953, he would appear in what probably remains his best-known film, the classic Western Shane — Heflin plays Joe Starrett, a simple homesteader whose battle against a powerful cattle baron Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer) is joined by the titular gunfighter, played by Alan Ladd. Shane becomes Starrett’s farmhand and the idol of Joe’s young son (Brandon de Wilde)…and is also drawn to Starrett’s wife Marian, played by actress Jean Arthur in her final theatrical film appearance. One of my favorite moments in Shane occurs during a rousing fistfight between Starrett, Shane and Ryker’s hired goons — at one point during the ruckus, Starrett and Shane look at one another and grin in solidarity and then go back to punching out the lights of the villains. A similar sequence occurs earlier in the film when Shane helps Starrett remove a large stump from his property; it’s been suggested that there’s a hidden attraction between Marian and Shane but I find the camaraderie exhibited by Shane and Starrett to be every bit as interesting as well.

Shane is no doubt Helfin’s best-recognized cinematic showcase but my favorite of his film performances is in the movie I mentioned at the beginning of this essay. I’ve always been a huge fan of Van’s character, Dan Evans, and how he insists on carrying out his volunteered duty of escorting Glenn Ford’s outlaw Ben Wade to that 3:10 locomotive despite the overwhelming evidence that it’s a suicidal mission at best. It’s not about the money; Ford offers him a bribe that dwarfs the piddly two hundred clams Heflin’s signed up for — it’s all about principle and doing the right thing. The Western movie would serve Heflin’s amazing acting versatility well; among the memorable oaters he also graced include The Raid (1954), an underrated tale about a group of escaped Confederate prisoners who plan to rob a bank and set fire to a town during the Civil War; Count Three and Pray (1955), in which Heflin plays a reformed wastrel-turned-pastor who encounters trouble in the small town he’s chosen to preach; and Gunman’s Walk (1958), in which his rancher must mediate the conflict between his two strong-willed sons (Tab Hunter, James Darren).

Other outstanding performances in Heflin’s catalog include the films Battle Cry (1955), Patterns (1956), They Came to Cordura (1959), Stagecoach (1966), The Ruthless Four (1968) and his final feature film, Airport (1970) — in which he played the sympathetic but nevertheless twisted antagonist whose on-board bomb sets the film’s plot in motion. In between his film assignments, Van continued to distinguish himself onstage in productions of A Memory of Two Mondays, A View from the Bridge and A Case of Libel. He reprised his role from this last production for television in 1968 and was nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding Single Performance in a Drama; in fact, his last show business project was an appearance in a 1971 television drama entitled The Last Child. He succumbed to a heart attack (while enjoying a dip in his pool) not long afterward at the age of 61.

Heflin once memorably remarked in an interview: “Louis B. Mayer once looked at me and said, ‘You will never get the girl at the end.’ So I worked on my acting.” And fans of this remarkably talented actor are all the richer for it; Van Heflin may not have been a conventional handsome leading man by Hollywood standards — but he left behind a legacy of film performances that would make any “pretty boy” green with envy. I’m proud to call myself a fan.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Glenn Ford, J. Stewart, Jean Arthur, K. Douglas, K. Hepburn, Oscars, Robert Ryan, Stanwyck, Theater, Van Hefiin

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, October 19, 2009

The only causes worth fighting for

By Edward Copeland

Whenever I prepare to write favorably about Frank Capra, I feel as if I should don a helmet first for the inevitable brickbats that will be launched my way. However, with Mr. Smith Goes to Washington celebrating its 70th birthday, I feel it needs recognition not only because it's a great film but it's a reminder of what a disappointment our elected representatives can be. Oh, if only filibusters were still real filibusters like the one Jefferson Smith gives at the film's climax instead of the toothless maneuver we're stuck with today that denies the right to simple majority rule. (We'll forget for the moment that since the entire Senate was against Smith in the movie, a cloture vote to cut him off would have been easily attainable.) Still, whenever I catch Mr. Smith, no matter how long it has been on, I have to watch until the end. It's the curse of being both a movie buff and a

political junkie. In a way, with recent events, it seems to have a bit of timeliness beneath the treacle and idealistic love of how this country should work. (Of course, the film conveniently avoids placing any of the senators within political parties.) With all the recent Senate openings that had to be filled by appointment or fiat, Jefferson Smith (James Stewart) turns out not to be someone who can be controlled by the corrupt political boss of his home state Jim Taylor (Edward Arnold), only Smith turns out to be reverent of the job he's taken, not a loose cannon like Illinois' Roland Burris, appointed by an embattled governor like Rod Blagojevich or someone who will do what he's told. The strength of Capra's film is its fine ensemble. In addition to Stewart and Arnold, you've got Jean Arthur as a cynical reporter who schools Jefferson Smith on the ways of Washington falls for his ideals, Thomas Mitchell as her fellow reporter, Harry Carey as the president of the Senate and last, but certainly not least, Claude Rains as the senior senator from Smith's state, a once great man who, as most long-serving lawmakers unfortunately seem to do, gets corrupted by the moneymen who keep him in office and call his shots. How little sadly has changed in 70 years. There also are bits with many other recognizable character actors such as William Demarest, Guy Kibbee, H.B. Warner, Charles Lane and Beulah Bondi. It garnered a slew of Oscar nominations in 1939, Hollywood's most fabled year for great films, though

political junkie. In a way, with recent events, it seems to have a bit of timeliness beneath the treacle and idealistic love of how this country should work. (Of course, the film conveniently avoids placing any of the senators within political parties.) With all the recent Senate openings that had to be filled by appointment or fiat, Jefferson Smith (James Stewart) turns out not to be someone who can be controlled by the corrupt political boss of his home state Jim Taylor (Edward Arnold), only Smith turns out to be reverent of the job he's taken, not a loose cannon like Illinois' Roland Burris, appointed by an embattled governor like Rod Blagojevich or someone who will do what he's told. The strength of Capra's film is its fine ensemble. In addition to Stewart and Arnold, you've got Jean Arthur as a cynical reporter who schools Jefferson Smith on the ways of Washington falls for his ideals, Thomas Mitchell as her fellow reporter, Harry Carey as the president of the Senate and last, but certainly not least, Claude Rains as the senior senator from Smith's state, a once great man who, as most long-serving lawmakers unfortunately seem to do, gets corrupted by the moneymen who keep him in office and call his shots. How little sadly has changed in 70 years. There also are bits with many other recognizable character actors such as William Demarest, Guy Kibbee, H.B. Warner, Charles Lane and Beulah Bondi. It garnered a slew of Oscar nominations in 1939, Hollywood's most fabled year for great films, though of its 11 nominations, it only won for best original story by Lewis R. Foster and Stewart's loss for best actor always has been believed to lead to his win the following year for The Philadelphia Story as a "makeup Oscar." Mitchell won the Oscar for supporting actor that year but not for Mr. Smith. He was amazingly great and busy in 1939, winning for Stagecoach but also giving solid support in Gone With the Wind and Only Angels Have Wings. Other than Stewart, the other two actors nominated by the Academy were Rains and, interestingly enough, Carey. Carey is good, but in a year as competitive as 1939, it's an odd choice to be sure. It's an odd second choice to pick just from Mr. Smith. Alas, the great Jean Arthur wasn't nominated at all. In fact, she only earned a single nomination in her entire career. As for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington itself, like Capra's It's a Wonderful Life, there is such a label of corniness that has been attached to the films that people forget (or never watch) and see there is a bit of darkness as well. Both films feature protagonists who get the shit kicked out of them by life. Of course, George Bailey is a dreamer, but a realist who recognizes the evil around him. Jefferson Smith also is a dreamer, but he's an naive idealist who is surprised to learn the ways D.C. really works. In the case of Mr. Smith, the chief villain is bad enough to run trucks carrying young boys off roads and give them life-threatening injuries when they aren't just using police to turn fire hoses on them. Still, Jefferson Smith doesn't quit and he doesn't cave and the crooks are defeated and right is victorious. It's a Wonderful Life may have an angel, but Mr. Smith in its own way is a bigger fantasy when you consider the crooks and dimwits we have in Congress today. Mr. Smith can give you a little lift and make you dream of a government that could be run for the people under the principles of the Founding Fathers instead of for the powerful and the pols addicted to the perks of their seats in Congress. Oh, and the movie's damn good, too.

of its 11 nominations, it only won for best original story by Lewis R. Foster and Stewart's loss for best actor always has been believed to lead to his win the following year for The Philadelphia Story as a "makeup Oscar." Mitchell won the Oscar for supporting actor that year but not for Mr. Smith. He was amazingly great and busy in 1939, winning for Stagecoach but also giving solid support in Gone With the Wind and Only Angels Have Wings. Other than Stewart, the other two actors nominated by the Academy were Rains and, interestingly enough, Carey. Carey is good, but in a year as competitive as 1939, it's an odd choice to be sure. It's an odd second choice to pick just from Mr. Smith. Alas, the great Jean Arthur wasn't nominated at all. In fact, she only earned a single nomination in her entire career. As for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington itself, like Capra's It's a Wonderful Life, there is such a label of corniness that has been attached to the films that people forget (or never watch) and see there is a bit of darkness as well. Both films feature protagonists who get the shit kicked out of them by life. Of course, George Bailey is a dreamer, but a realist who recognizes the evil around him. Jefferson Smith also is a dreamer, but he's an naive idealist who is surprised to learn the ways D.C. really works. In the case of Mr. Smith, the chief villain is bad enough to run trucks carrying young boys off roads and give them life-threatening injuries when they aren't just using police to turn fire hoses on them. Still, Jefferson Smith doesn't quit and he doesn't cave and the crooks are defeated and right is victorious. It's a Wonderful Life may have an angel, but Mr. Smith in its own way is a bigger fantasy when you consider the crooks and dimwits we have in Congress today. Mr. Smith can give you a little lift and make you dream of a government that could be run for the people under the principles of the Founding Fathers instead of for the powerful and the pols addicted to the perks of their seats in Congress. Oh, and the movie's damn good, too.

Tweet

Labels: 30s, Capra, J. Stewart, Jean Arthur, Movie Tributes, Rains, T. Mitchell

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, October 06, 2008

Centennial Tributes: Carole Lombard

By Josh R

So well-enshrined is Carole Lombard’s reputation as one of the funniest women ever to appear in films that it is easy to forget she was also one of the most beautiful. With vaulted cheekbones made for catching shadows, pencil-thin eyebrows and shimmering white-blonde hair, she photographed as divinely as either Garbo or Dietrich – in publicity stills, she was every inch the goddess.

It is yet another example of the great and delicious paradox of human genetics (or, if you prefer, testament to the notion that The Almighty is not without sense of humor) that such pristine features should be assigned to someone with the freewheeling, improprietous imagination of a hyperactive class clown, born to exasperate the teacher and foster a spirit of anarchy in the schoolroom. In spite of Hollywood’s drab insistence that external appearance reflect character and personality, as if by some cosmic prank a dirty-minded satyr had wound up with the face of an angel. Lombard was never insensible to the ridiculousness of the situation, and in film after film, she ran with it. If the whacked-out universe of screwball comedy was the domain in which she felt most herself, what else was there to do but treat her beauty as the ultimate joke? It was almost as funny, if just as improbable, that such a rare bird would be given so prosaic a birth name as Jane Alice Peters.

The general axiom in show business has always been that broad physical comedy — making faces, taking pratfalls, etc. — is the province of those who can’t get by on looks alone. The Bert Lahrs, Fanny Brices and Carol Burnetts go in for exaggerated characterization, accompanied by a lot of mugging, because that’s their way into an audience’s heart. If they were knockouts, all they’d have to do is stand there and look gorgeous — simply put, if you have the looks, you don’t have to sweat. If that was really ever the case, then Carole Lombard never got the brief — and even if she had, she may well have crumpled it up and tossed it in the trash before the message had had the chance to make a dent in her consciousness. Other comediennes of the 1930s could be just as funny, but never with the same degree of unflagging manic energy or off-the-wall outrageousness as the woman dubbed The Daffy Duse of Comedy. Katharine Hepburn, Claudette Colbert, Rosalind Russell and Jean Arthur played similar roles, but they did it without bouncing off the furniture, squawking and squealing like deranged pigeons fighting over breadcrumbs, or generally carrying on like they’d just been sprung from the nuthouse. Pauline Kael summed up the singular performance style of Lombard best: “She threw herself into her scenes in a much more physical sense than the other women did, and her all-outness seemed spontaneously giddy. It was easy to believe that a woman who moved like that and screamed and hollered with such abandon was a natural, uninhibited cutup — naturally high-spirited.”

The riddle of Lombard’s onscreen persona — exactly how such a pretty girl could comport herself with such unbridled lack of decorum — only begins to make sense when you take into account who she was when the cameras stopped rolling. As both an actress and an individual, Lombard was blissfully unencumbered by anything ressembling a filter. She pretty much said and did whatever sprang to mind, without stopping to consider whether or not it was proper, polite or even within the bounds of good taste. The most famous quote ever attributed to her is nothing she ever said on onscreen, but a rather a comment she made about her second husband, Clark Gable: “My God, you know I love Pappy, but I can’t say he’s a hell of a lay.” Her on-set antics were as infamous as they were novel. When Fredric March began making aggressive advances towards her on the set of Nothing Sacred, she dealt with the situation by drawing him into her dressing room for a what he presumed would be a moment of passion. The actor stormed out a minute later with a stricken look of shock upon his face, after his co-star had lifted up her skirts to reveal a prosthetic appendage obtained from a novelty store of questionable reputation (the prop was, in every respect, at odds with the gender of the person wearing it). Her lack of tact reverberated in ways probably never even intended, and laid the groundwork for at least one of Hollywood’s great inside jokes. The actress’ most significant contribution to history of motion pictures came by virtue of a film in which she never even appeared, nor was in any way directly involved with; it was she who spilled the beans to Orson Welles about William Randolph Hearst’s pet name for a certain part of his lady love Marion Davies’ anatomy — “Rosebud.”

As entertaining as the lore surrounding Lombard’s private life is, it doesn’t match the value of her public works — namely, what she accomplished onscreen. She probably appeared in more great comedies of the era than anyone save for Cary Grant, and her best films haven’t lost a fraction of their appeal with the passage of time. I fully intended to revisit some her best-known flicks before writing this piece — unfortunately, an unyielding schedule has prevented me from doing so (when my ship comes in, I’ll cease to work and watch movies all day). Still, there are moments which stand out with such immediate clarity they require no reinforcement: on her back in silk pajamas, flailing her legs in the air to fend off a wild-eyed John Barrymore in Twentieth Century; explaining the pointlessness of scavenger hunts to William Powell in breathless, stream-of-consciousness fashion in My Man Godfrey; being repeatedly pushed down onto her deathbed in Nothing Sacred and popping up each time like a red-faced jack-in-the-box; feigning ecstasy after locking lips with a Nazi in To Be or Not to Be and offering up a ridiculously rhapsodic fascist salute in tribute to his kissing skills. There were other, lesser comedies in which she was just as delightful — particularly Hitchcock’s Mr. & Mrs. Smith and Leisen’s Hands Across the Table — while a handful of dramas did manage to catch some of her spark. Serious, straight-forward roles failed to engage her impudent sense of mischief; before finding her calling in farce, she more often than not seemed bored by the earnest ingenue or suffering lady roles she was required to play. It’s worth noting that, as a great beauty, she wasn’t really allowed to be funny for several years after she’d already achieved stardom; after so many bland roles in so many bland films, she was probably given to wonder why she’d been cursed with so striking a countenance. Her prettiness became the punchline once she’d figured out exactly what her true gifts were, and where they could be best applied.

It is one of the sadder ironies in Hollywood history that so celebrated a comedienne should meet with an end so tragic in nature — Carole Lombard died in a plane crash during a war bond tour a few months shy of her 35th birthday. She left behind a devestated Gable and legions of grief-stricken fans, none of who seemed able to comprehend how so mirthful a presence could be taken away in seemingly so cruel a fashion. For those who loved her — and those who love her work — her legacy of laughter and high spirits remains undiminished by the circumstances surrounding her death. Lombard’s genius lay in the fact that she never set limits for herself, or sought to put a cap on the mayhem she so enjoyed being at the center of; she seemed only too happy to go off the deep end when something struck her as being as funny. That fearlessness, along with the peerless ingenuity with which she was able to wring laughs from even the flimsiest of setups, provide an infinite source of pleasure to anyone and everyone who has or will sample her work. Ultimately, it was her talent that was the true thing of beauty.

Tweet

Labels: Fredric March, Gable, Garbo, Hitchcock, Jean Arthur, K. Hepburn, Kael, Lombard, Roz Russell, Welles

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, August 30, 2008

Centennial Tributes: Fred MacMurray

By Josh R

For the first decade of his career, Fred MacMurray was a model of gentlemanly comportment. Pleasant in manner and appearance, he provided a strong shoulder for Hollywood’s top female stars to lean and occasionally weep on in a series of films in which his function was clearly secondary. Not that MacMurray seemed to register any of the supposed indignity of playing second fiddle; he understood that his job was to show up promptly and well-pressed, corsage in hand, and execute the duties of a conscientious escort without diverting too much attention from his leading lady.

In film after film from the mid-'30s to the early '40s, MacMurray was attractive without being conspicuously so, charmingly low-key, and dutifully observant of the Boy Scout’s honor code as pertaining to relations with the opposite sex. Consider that painful dinner party sequence in Alice Adams — just one of a series of humiliations Katharine Hepburn must endure throughout the course of that film — in which, as the guest of honor, MacMurray spares the heroine’s feelings by pretending not to notice that the soup is cold, the room is sweltering and the company is decidedly bourgeois. If there had been a merit badge for chivalry, he would have won it several times over.

You can earn medals for good behavior in certain walks of life, but not many prizes are awarded for being a good team player in the film business. While a very fine actor, MacMurray may never have been a distinctive enough presence to grab the spotlight for himself. His masculinity was of the casual, nonthreatening variety; he was good-looking, without being exactly handsome; he could be very funny, but not in such a way as to give the great comic clowns of the age any reason for concern. His seeming averageness consigned him to leading man duties in light comedies and tearjerkers, the kind of films frequently referred to as “women’s pictures.” The ladies were the main attraction, and good boy scout that he was, MacMurray graciously allowed himself to be consistently upstaged by Claudette Colbert, Carole Lombard, Rosalind Russell, Jean Arthur, Paulette Goddard and gallery of others. Perhaps all that modesty and nobility — being a nice guy in a woman’s world — began to wear on him after a while, eroding his confidence and breeding a sense of dissatisfaction. For if MacMurray’s early outings never betrayed a whiff of danger — he had trained his preternaturally deep, gruff voice to speak in the hush, dulcet tones of a sympathetic Boy Friday, while his features remained frozen in a perpetual mask of wholesome credulity while comforting all those chiffon-swathed damsels in distress — he did manage to veer off course on a few occasions, forsaking the straight and narrow path just long enough to create room for doubt as to whether all that clean conduct may have little more than a put-on.

The dominant-submissive dynamic in most of his early pictures — which really made notably few demands of him as an actor — probably made him impatient for something

more challenging, less emasculating. Consider Double Indemnity’s Walter Neff, a character defined very much by a spirit of restlessness. A moral weakling who falls prey to the machinations of yet another dominant female (in this case, a genuine sociopath with metal anklets that cut into her reptilian skin without drawing blood), what makes Walter so eminently corruptible is how bored he’s become in playing by the rules. He goes from a passive observer to an active participant, and effect is just intoxicating enough to give him the false illusion of being the one in charge. The fear of getting caught becomes as much of a turn-on as the breaking of the social compact, and murder becomes the ultimate sexual act — if planning a murder may be the ultimate form of foreplay, enacting it is the ultimate form of release. Once again, a woman is really the one calling the shots — only this time, the man finally gets disgusted enough to do something about it.

more challenging, less emasculating. Consider Double Indemnity’s Walter Neff, a character defined very much by a spirit of restlessness. A moral weakling who falls prey to the machinations of yet another dominant female (in this case, a genuine sociopath with metal anklets that cut into her reptilian skin without drawing blood), what makes Walter so eminently corruptible is how bored he’s become in playing by the rules. He goes from a passive observer to an active participant, and effect is just intoxicating enough to give him the false illusion of being the one in charge. The fear of getting caught becomes as much of a turn-on as the breaking of the social compact, and murder becomes the ultimate sexual act — if planning a murder may be the ultimate form of foreplay, enacting it is the ultimate form of release. Once again, a woman is really the one calling the shots — only this time, the man finally gets disgusted enough to do something about it. The shifty anxiety and bitter fatalism MacMurray brought to his performance in the Billy Wilder film were astonishing, and not the least by virtue of their coming from such an unexpected source. It was a role he had been reticent to play, but ultimately the one in which he seemed the most thoroughly at home. Double Indemnity was the first film to show the darker side of MacMurray — happily, it wouldn’t be the last. Pushover, The Caine Mutiny, and especially The Apartment — as the embodiment of smooth-talking corporate disingenuousness — showed how effortlessly he could peel back the layers of surface geniality

to reveal cowardice, ruthlessness or just plain rottenness. Occasional forays into villainy may have given the chance to stretch, but niceness remained his stock in trade. For MacMurray, the 1960s meant paydirt. My Three Sons stayed on the air so long they started filming it in color, while a series of films for Disney established him as favorite of family audiences. He seemed to enjoy himself in his outings for Disney — most notably as the sane-mad-scientist who whips up an electro-magnetically charged form of silly putty in The Absent-Minded Professor — but his most popular successes didn’t really represent his best work. MacMurray was a whiz at doing comfort food, but his meatiest roles — especially the two for Billy Wilder — were ultimately his most satisfying. The actor wisely decided to retire after The Swarm…so many bees packing so much less sting than Stanwyck in a blonde wig and trashy heels. It is tempting to consider his a minor career — tempting, that is, until one considers that unforgettable moment when love and hate converge with the firing of a gun, the final showdown between partners in crime bound together in deed and consequence “straight down the line”. It’s a testament to the power and clarity of MacMurray’s performance the pulling of that trigger seems not so much a sordid crime of passion as the ultimate act of self-loathing punishment. As Walter Neff ruefully recounts in his recorded confession, “I didn’t get the money…and I didn’t get the woman.” MacMurray never really got the rewards, nor the recognition of the type usually accorded a major star…but then, MacMurray was the type of actor who seemingly always gave more than he got. His co-stars, directors and audiences were the chief beneficiaries.

to reveal cowardice, ruthlessness or just plain rottenness. Occasional forays into villainy may have given the chance to stretch, but niceness remained his stock in trade. For MacMurray, the 1960s meant paydirt. My Three Sons stayed on the air so long they started filming it in color, while a series of films for Disney established him as favorite of family audiences. He seemed to enjoy himself in his outings for Disney — most notably as the sane-mad-scientist who whips up an electro-magnetically charged form of silly putty in The Absent-Minded Professor — but his most popular successes didn’t really represent his best work. MacMurray was a whiz at doing comfort food, but his meatiest roles — especially the two for Billy Wilder — were ultimately his most satisfying. The actor wisely decided to retire after The Swarm…so many bees packing so much less sting than Stanwyck in a blonde wig and trashy heels. It is tempting to consider his a minor career — tempting, that is, until one considers that unforgettable moment when love and hate converge with the firing of a gun, the final showdown between partners in crime bound together in deed and consequence “straight down the line”. It’s a testament to the power and clarity of MacMurray’s performance the pulling of that trigger seems not so much a sordid crime of passion as the ultimate act of self-loathing punishment. As Walter Neff ruefully recounts in his recorded confession, “I didn’t get the money…and I didn’t get the woman.” MacMurray never really got the rewards, nor the recognition of the type usually accorded a major star…but then, MacMurray was the type of actor who seemingly always gave more than he got. His co-stars, directors and audiences were the chief beneficiaries. Tweet

Labels: Disney, Jean Arthur, K. Hepburn, Lombard, MacMurray, Paulette Goddard, Roz Russell, Stanwyck, Television, Wilder

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, June 04, 2007

Centennial Tributes: Rosalind Russell

By Josh R

The casting of the female lead in His Girl Friday represented a compromise, and one which director Howard Hawks was initially loath to make. Everyone on the filmmaker’s wish list was either uninterested or unavailable — Jean Arthur was the first choice, followed by Katharine Hepburn, Carole Lombard, Claudette Colbert, Irene Dunne and Ginger Rogers. Rosalind Russell would have been well at the bottom of the list — that is, if it had even occurred to Hawks to put her there in the first place. The actress had made a modest name for herself playing elegant ladies and frigid bitches in turgid melodramas — usually in support of another female star. The Women, another film the actress had to fight to be cast in and the first to challenge the industry’s perception of her, was still awaiting release, and there was little indication from her other work that she had the chops to meet the demands of screwball comedy.

Needless to say, Hawks was in a bad temper when filming commenced in the summer of 1939, and regarded his leading lady, who’d been forced upon him by the studio in a last ditch effort to get the film made on schedule, with no small amount of resentment. Picking up on his hostility, Russell took the director aside and told him, “I know you didn’t want me, but we’re stuck with each other.” The tension was alleviated, and Hawks would later insist that no one — not Hepburn, Lombard or any of the others — could have brought as much verve, style and wit to the part as Russell did. Viewing the finished product, no one would challenge that appraisal.

Hawks can hardly be blamed for harboring some early doubts — from the very beginning, Rosalind Russell was an unlikely candidate for stardom. The Connecticut-bred lawyer’s daughter, the product of a scrupulous Catholic upbringing, was a tall, almost ungainly woman with a raspy contralto voice and plain, sensible features. Her no-nonsense appearance, which was smart and well-tailored without being austere, suggested both a practical outlook and a bemused sense of irony. No one would ever mistake her for an ingénue or a sex goddess — which probably suited Russell just fine. Never beautiful in the conventional sense, she could generate more heat with an arched eyebrow and a deadpan retort than any of the glamour girls could with smoldering looks and coy displays of their natural assets. She could be side-splittingly funny in films that tapped into the zanier side of her nature, but made surprisingly few comedies during her four decades as a cinema fixture. It’s a testament to the impact she had in the handful of films that allowed her to cut loose that she is remembered first and foremost as a comedienne.

After making her film debut in 1934’s Evelyn Prentice, the next five years of her career proceeded without incident. Hollywood wasn’t quite sure what it had on its hands, or exactly what to do with her — she didn’t fit comfortably into any easy category, and seemed slightly embarrassed as a result. More often than not, she wound up playing patrician ladies in fussy costumes which tried to minimize her height. Typical of the period was China Seas, where she was cast as a romantic rival to Jean Harlow for the affections of Clark Gable. The cool brunette didn’t stand a chance — Harlow’s curvy, hip-swinging brashness made the lanky interloper seem like even more of a stiff than she actually was.

When the actress graduated to leads, the results were initially less than rewarding. As the title character in Craig’s Wife, she was a domestic dictator and an evil oppressor of men — somewhat surprisingly, this study in

misogyny was the work of a female director, Dorothy Arzner. From an acting standpoint, Russell failed conspicuously in a role that, as thinly conceived as it was, would seem to call for an element of shamelessness — Joan Crawford, never one to shy away from playing brass-knuckled bitches, did much better by the same material in Harriet Craig 14 years later. To be fair, no one could have brought much in the way of human dimension to the character, a soulless martinet with an only slightly more complex pathology than The Wicked Witch of the West. As someone less interested in the subtleties of film acting, Crawford probably responded to something in the material Russell didn’t — Mommie Dearest’s late-career philosophy might be best described as “when in doubt, bare fangs.” Russell fared somewhat better in her next two films, Night Must Fall and The Citadel — box office hits which helped to solidify her position, but not affording her the opportunity to do much more than adopt a reactive stance while her male co-stars delivered star turns. Roberts Montgomery and Donat were nominated for Oscars, while their leading lady remained largely an afterthought — in both outings, she affected an earnest wholesomeness which gave little indication of an arresting personality.

misogyny was the work of a female director, Dorothy Arzner. From an acting standpoint, Russell failed conspicuously in a role that, as thinly conceived as it was, would seem to call for an element of shamelessness — Joan Crawford, never one to shy away from playing brass-knuckled bitches, did much better by the same material in Harriet Craig 14 years later. To be fair, no one could have brought much in the way of human dimension to the character, a soulless martinet with an only slightly more complex pathology than The Wicked Witch of the West. As someone less interested in the subtleties of film acting, Crawford probably responded to something in the material Russell didn’t — Mommie Dearest’s late-career philosophy might be best described as “when in doubt, bare fangs.” Russell fared somewhat better in her next two films, Night Must Fall and The Citadel — box office hits which helped to solidify her position, but not affording her the opportunity to do much more than adopt a reactive stance while her male co-stars delivered star turns. Roberts Montgomery and Donat were nominated for Oscars, while their leading lady remained largely an afterthought — in both outings, she affected an earnest wholesomeness which gave little indication of an arresting personality.

If her prospects looked dim, the actress remained undaunted — she had some of Hepburn’s can-do Yankee feistiness, and an intelligence to match. She lobbied for the role of Sylvia Fowler, the loose-lipped socialite who views the dissemination of gossip as something akin to a higher calling, in George Cukor’s star-studded screen adaptation of Clare Booth Luce’s The Women. It was apparent that after years of playing it safe and fading into the scenery, she’d learned her lesson — the deliriously uninhibited comic brio that she exhibited in the role gave lie to the presumption that refinement and restraint were her salient characteristics as a performer. With her peerless talent for physical and verbal slapstick, she stole the film right out from under Crawford, Norma Shearer, Paulette Goddard and a gallery of others. It was as if someone had let loose a fox in a henhouse — untrammeled malice has never been more sublimely ridiculous.

Having finally broken out of her shell, she hit her stride. The role of Hildy Johnson in His Girl Friday was originally written for a man, and in its transmogrified incarnation could have easily come across as a shrill, insulting parody of the tough-minded career woman as a masculine (or worse still, asexual) entity, but Russell was much too smart, and far too inventive, to fall into that trap — her Hildy was one of the boys, alright, but more woman

than ever. For the first time in motion pictures, here was a truly modern woman — not only the professional equal of her male counterparts, but with a quickness and creativity that left them in the dust. The pride of The Morning Star is an ace reporter who can outtalk, outthink and out-maneuver every man in the room, and rather than resent her for it, her colleagues can only peer out from under their porkpie hats and newsman’s visors with a mixture of awe and respect as she runs circles around the rest of them. The actress was a whirling dervish of energy, sprinting through entire pages of dialogue at warp speed without missing a beat, and her inflections throughout were priceless. She threw herself into the part with the same kind of edgy, go-for-broke tenacity that the character exhibited when chasing headlines, and made it clear that, for Hildy Johnson, no other kind of life is possible. She needs the thrill of the chase, and a guy like Walter Burns who can not only keep up with her, but is only too happy to let her run with the wolves. That’s why nice, bland Ralph Bellamy had to be sent packing at the end of the picture — there’s no way he could avoid being blown away by this sonic boom in heels.

than ever. For the first time in motion pictures, here was a truly modern woman — not only the professional equal of her male counterparts, but with a quickness and creativity that left them in the dust. The pride of The Morning Star is an ace reporter who can outtalk, outthink and out-maneuver every man in the room, and rather than resent her for it, her colleagues can only peer out from under their porkpie hats and newsman’s visors with a mixture of awe and respect as she runs circles around the rest of them. The actress was a whirling dervish of energy, sprinting through entire pages of dialogue at warp speed without missing a beat, and her inflections throughout were priceless. She threw herself into the part with the same kind of edgy, go-for-broke tenacity that the character exhibited when chasing headlines, and made it clear that, for Hildy Johnson, no other kind of life is possible. She needs the thrill of the chase, and a guy like Walter Burns who can not only keep up with her, but is only too happy to let her run with the wolves. That’s why nice, bland Ralph Bellamy had to be sent packing at the end of the picture — there’s no way he could avoid being blown away by this sonic boom in heels.

Her resounding success in the Hawks entry dramatically altered her career trajectory, and the next five years saw

her playing a series of variations on the same character. She was very good in Take a Letter, Darling opposite Fred MacMurray — one of the few leading men, other than Cary Grant, with whom she managed a genuine chemistry — but My Sister Eileen was a bigger hit with audiences. Her neophyte journalist braving the wilds of the urban jungle was sort of a country cousin to Hildy Johnson, and showed how fully she’d come into her own in the realm of screwball comedy. If the film itself was an inferior showcase, it nonetheless provided her with a welcome opportunity to hone her talent for slapstick — she earned the first of her four Oscar nominations for her efforts. Her best vehicle of the 1940s, after His Girl Friday, was the comedy-drama Roughly Speaking, which revealed an element of defensiveness as a component of the super-competent, overachieving persona. Wary of being typecast, she shifted her focus to drama, to somewhat disappointing effect. Sister Kenny, concerning the heroics of an Australian bush nurse who pioneers a revolutionary treatment for polio, was a Greer Garson film with crippled children standing in for illegitimate babies and the isolation of radium. She carried the film with dignity, but no amount of solid professionalism could keep it from seeming like a step backward. The marathon theatrics of Mourning Becomes Electra, Eugene O’Neill’s Civil-War-era riff on the precepts of Greek Tragedy, made for a creaky, ponderous affair — the play was not an ideal candidate for cinematic adaptation, especially at a time when its Oedipal undertones had to be tiptoed around in order to pass muster with the censors. Russell was rather badly miscast in a role that required more volatile nervous energy than she could muster — Bette Davis would have been more appropriate — but she made a brave try nonetheless. The Velvet Touch went so far as to cast her as a sweaty murderess; the entire enterprise seemed badly in need of Hitchcock.

her playing a series of variations on the same character. She was very good in Take a Letter, Darling opposite Fred MacMurray — one of the few leading men, other than Cary Grant, with whom she managed a genuine chemistry — but My Sister Eileen was a bigger hit with audiences. Her neophyte journalist braving the wilds of the urban jungle was sort of a country cousin to Hildy Johnson, and showed how fully she’d come into her own in the realm of screwball comedy. If the film itself was an inferior showcase, it nonetheless provided her with a welcome opportunity to hone her talent for slapstick — she earned the first of her four Oscar nominations for her efforts. Her best vehicle of the 1940s, after His Girl Friday, was the comedy-drama Roughly Speaking, which revealed an element of defensiveness as a component of the super-competent, overachieving persona. Wary of being typecast, she shifted her focus to drama, to somewhat disappointing effect. Sister Kenny, concerning the heroics of an Australian bush nurse who pioneers a revolutionary treatment for polio, was a Greer Garson film with crippled children standing in for illegitimate babies and the isolation of radium. She carried the film with dignity, but no amount of solid professionalism could keep it from seeming like a step backward. The marathon theatrics of Mourning Becomes Electra, Eugene O’Neill’s Civil-War-era riff on the precepts of Greek Tragedy, made for a creaky, ponderous affair — the play was not an ideal candidate for cinematic adaptation, especially at a time when its Oedipal undertones had to be tiptoed around in order to pass muster with the censors. Russell was rather badly miscast in a role that required more volatile nervous energy than she could muster — Bette Davis would have been more appropriate — but she made a brave try nonetheless. The Velvet Touch went so far as to cast her as a sweaty murderess; the entire enterprise seemed badly in need of Hitchcock.

The New York stage paved the way for career revitalization, and the actress took Broadway by storm with her star turn in Wonderful Town, Leonard Bernstein’s musical treatment of My Sister Eileen. If her singing skills posed no threat to the likes of Martin and Merman, she could still fire off Comden and Green’s custom-crafted zingers like a champ, and earned a Tony Award for her efforts. Since Hollywood had nothing better

to offer than a supporting stint as a boozy spinster in the sodden mess of Picnic, she returned to the theater to take on the title role in Auntie Mame, a performance she repeated for the film version. The character of a madcap nonconformist, whose personality is expansive and irrepressible as her hair color is changeable, was a seven-course meal of a part, and the actress made the most of it. Everything about the globe-trotting, gin-swilling, convention-flouting Mame was writ larger than life, and Russell attacked the role with such giddy abandon as to make the entire mixed-up universe, from the Heart of Dixie to the Himalayas, seem like her own personal playground. It was her most unabashedly silly performance, and ultimately her most iconic; by thumbing her nose at conservatism, with behavior as outrageous as her wardrobe, both Mame and the actress playing her inadvertently kicked off the drag queen movement.