Tuesday, July 26, 2011

The twilight of an extraordinary life

By Edward Copeland

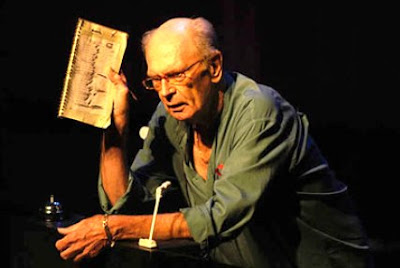

When Charles Nelson Reilly died in 2007, the percentage of people who knew who he was by name, unfortunately, already had fallen precipitously. Thankfully, in the final years of his life the theater actor turned game show fixture had developed and toured in a solo show about his life called Save It for the Stage. Even though Reilly had stopped touring with the show, The Life of Reilly's co-directors Frank L. Anderson and Barry Polterman talked him into performing it one more time in October 2004 so they could film it. As a result, they made this film record of Reilly's remarkable story as only he could tell it.

As title cards explain at the film's opening, the solo show evolved from a talk Reilly was asked to give in 1999. He didn't have anything planned and spoke extemporaneously for more than three hours, enjoying the hell out of it. After that experience, he worked with actor Paul Linke to pare down the show into a more compact running time and Save It for the Stage was born.

While the version of the solo show captured in The Life of Reilly runs half the time that original three-hour speech did, I imagine Reilly would hold your interest at the longer running time based on the nonstop cyclone

of energy he becomes as he shares an oral autobiography, beginning with his birth on Jan. 13, 1931, in The Bronx, and the difficulties growing up with his eccentric family, particularly his bigoted mother who was prone to say things such as "I should have thrown away the baby and kept the afterbirth." (She gave the stage show its name because any time young Charles would go on about something, she'd tell him to "Save it for the stage.") He was more enamored with his father who was a commercial artist, drawing beautiful color advertisements. Young Charles struggled in school, not realizing that his problem was his eyesight, not his intelligence, but he always was imaginative from an early age. A particularly poignant portion of the film comes when he describes his mom taking him to his first movie at the Loews Paradise and how he felt "so safe and warm" sitting there in the dark, gazing at those images.

of energy he becomes as he shares an oral autobiography, beginning with his birth on Jan. 13, 1931, in The Bronx, and the difficulties growing up with his eccentric family, particularly his bigoted mother who was prone to say things such as "I should have thrown away the baby and kept the afterbirth." (She gave the stage show its name because any time young Charles would go on about something, she'd tell him to "Save it for the stage.") He was more enamored with his father who was a commercial artist, drawing beautiful color advertisements. Young Charles struggled in school, not realizing that his problem was his eyesight, not his intelligence, but he always was imaginative from an early age. A particularly poignant portion of the film comes when he describes his mom taking him to his first movie at the Loews Paradise and how he felt "so safe and warm" sitting there in the dark, gazing at those images.Reilly's first taste of acting came in fourth grade when his teacher offered young Charles the role of Columbus in a class play. His mother was resistant, saying he'd never learn the lines because of his difficulties (still denying that eyesight was the problem) but the teacher talked her into it and his acting career was born in P.S. 53. Around the same time young Mr. Reilly received an opportunity, the elder Mr. Reilly missed a big one.

An artist who worked in black and white fell in love with his father's color artwork and urged him to go to California with him, but Reilly's mother nixed the move because all her relatives were on the East Coast. The man's name was Walt Disney. Soon, advertising turned more to photographs than illustrations and Reilly's father was thrown out of work and into alcoholism and eventually institutionalized, forcing young Charles and his mother to move to Hanover, Conn., to live with his uncle, aunt and grandparents, Swedish immigrants who spoke no English. Eventually, his father rejoined them and his aunt, who had her own problems, agreed to try a new medical procedure: a lobotomy. Though Reilly never dwells on his homosexuality, he tells how the neighbors to that household said that he was a "little odd."

"How do you think I felt being the odd one in that family?" he asks, adding that Eugene O'Neill wouldn't come near that house and that he spent his adolescence in an Ingmar Bergman film. However, he reminds his audience what Mark Twain said about laughter being the same in every language. Reilly's ability to tell these stories, some of them horrifying, and still be able to wring laughs from theatergoers was a great gift indeed and as he set out to act for a living in 1950, his tales of theater and show business prove even more entertaining.

A particularly astounding portion is when he discusses the acting class he attended taught by Uta Hagen at HB Studio, the school she founded with her husband Herbert Berghof. The cost was $3 a week. He reads the roll of his 11 a.m. Tuesday class and it's amazing because every name would achieve success, fame and accolades. Here is the list, minus Reilly, alphabetically:

As Reilly tells it, they all had three things in common: "We wanted to be on stage, none of us had any money and we COULDN'T ACT FOR SHIT!" Reilly adds that if they saw McQueen and Holbrook act out a scene as Biff and Happy Loman from Death of a Salesman one more time, "You'd go out of your fucking mind." He does make the point that people who wanted to act back then actually studied, something not as common as it used to be. By my count, this class (to date) has earned nine Tony Awards out of 30 nominations (11 out of 32 if you toss in Uta Hagen's two wins), six Oscars out of 16 nominations and 11 Emmys out of a whopping 61 nominations. Charles Nelson Reilly himself accounts for a Tony for featured actor in a musical as Bud Frump in the original production of Frank Loesser's How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, a nomination as Cornelius in the original Hello, Dolly! and a nomination for directing the revival of The Gin Game that starred Julie Harris and Charles Durning. Reilly earned three Emmy nominations: for The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, a guest shot on The Drew Carey Show and for reprising the Jose Chung character he created on The X-Files on an episode of Millennium.

As with all struggling actors in New York since the beginning of time, Reilly needed work to pay the bills until he started landing paying parts in production. He was excited when a female friend who worked at NBC got him a meeting with the possibility of on-air work. Reilly arrived and met Vincent J. Donahue, the NBC chief at the time, who dismissively sent him away telling him, "We don't put queers on television." Reilly admits that as hateful as that comment was, it rolled off his back. Words like that didn't bother him as much as coming home to find roaches in his Minute Rice. Though he eventually became somewhat of a gay icon, none of the autobiographical show deals with the difficulties of being a gay actor except for that anecdote and there is no mention of a romantic life. Reilly considered himself an actor first — his sexual orientation was just another aspect his life, just like his bad eyesight. Both were parts of him, but neither defined him.

Reilly lived and breathed theater and that is what he wanted to share with the audiences who came to his shows — the upbringing that got him to that point and how it always was an integral part of his life, even after he became better known for kids' TV shows and Match Game. In 1954, he appeared in 22 off-Broadway shows. His Broadway debut came, ironically, as an understudy for another actor who became a gay icon and game show staple — Paul Lynde. Lynde had to be out of Bye Bye Birdie every Thursday night because of a contract to appear on The Perry Como Show, so Reilly took his place once a week. Eventually, he also got to be Dick Van Dyke's understudy in the musical.

He discusses how his close friendship with Burt Reynolds began in New York when Reynolds was a struggling actor and then decades later, when Reynolds built his theater in Jupiter, Fla., he attached an acting school and gave Reilly a beach house to live in so he would teach.

He talks about his times in Hollywood, especially how much he enjoyed being on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson where he was a guest more than 100 times. He talks about one particular time when another guest was a woman who ran a Shakespeare in the Park program in Ohio and he said something and she responded, quite snootily, "What would someone like you know about Shakespeare?" Then he showed her.

Before he taught in Florida, he would teach acting back at that old HB Studio and in a story that particularly cracked me up because it reminded me of my days of both attending and judging high school drama contests almost 25 years ago now, he says, "If I saw one more Agnes of God…" If you've experienced high school drama contests since that play was written, you know exactly what he means (and I'd toss in 'night, Mother as well).

Reilly talks and talks and talks and you're never bored. You're usually laughing, but sometimes, as when he describes being present at 13 at an infamous Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus fire that claimed many lives, including that of one of his childhood friends, you're mesmerized. The Life of Reilly truly captivates. The biggest barrier to enjoying it is finding a way to see it. It's on streaming at Netflix but not DVD, so watch it there before you cancel and go back to DVD only. Neither GreenCine nor Blockbuster carries it on DVD or On Demand. Redbox doesn't carry it. Hulu Plus doesn't stream it. Amazon Instant Video DOES have it for $2.99, though you could buy it for $9.99. Best Buy CinemaNow doesn't have it for streaming. Comcast XfinityTV ON Demand doesn't have it either.

It's a miracle that Netflix's streaming has it right now because eventually, it won't as smaller, wonderful titles such as The Life of Reilly that are a whole FOUR years old and are perceived as having too small a niche audience disappear entirely from home rental availability. It's a shame because it means the number of people who remember Charles Nelson Reilly will decline more rapidly than it is declining already.

Tweet

Labels: 00s, Awards, Burt Reynolds, Carson, Disney, Documentary, Durning, Frank Loesser, Geraldine Page, Grodin, Holbrook, Ingmar Bergman, Lemmon, Musicals, O'Neill, Oscars, Robards, Shakespeare, Television, Twain