Monday, August 14, 2006

When Oscar Drops the Ball

By Josh R

Josh R here — after several weeks without full Internet access (and a new computer that’s been a problem child), I’ve decided to celebrate my return to cyberspace by resuming one of my favorite pastimes: Oscar-bashing. As we all know, the year’s best performances usually go home empty handed — quite often, they aren’t even nominated. I decided to try to pick out the 20 most (to borrow a phrase from Dame Julie Andrews) egregiously overlooked performances in the history of the Academy Awards — the kind of omissions that just make you scratch your head, if not bang it against the wall out of sheer frustration.

Entertainment Weekly attempted something like this a year or two ago — I believe their list went all the way up to 100 — and the results ranged from the obvious and expected to the puzzling and obscure. I’m not sure if there’s anything on my list that wasn’t included on theirs (I don’t have it in front of me to cross-reference), but I’m not going to make any strained effort at originality; all of the performances cited are, I imagine, ones that most of the visitors to this site will be familiar with, if not through first-hand viewing experience, than certainly by reputation. If this doesn’t exactly reflect what I think the best unnominated performances of all time are in the strictest of order, it’s because, in the interest of fairness, I’ve decided not to cite any individual actor more than once — if I’d chosen to do otherwise, the performances of Cary Grant and Humphrey Bogart alone might have accounted for at least 25% of what emerged from the elimination process.

Needless to say, paring down the list turned out to be very, very tough — there were a lot of painful cuts I had to make, but in the interest of time and space (and in order not to try Mr. Copeland’s patience more than I had to), I was determined to limit myself to 20. This has resulted in some bruised feelings in several quarters — No. 21, Danny Kaye from The Court Jester, still isn’t returning my phone calls. Based on the elimination process, I would not have difficulty finding enough performances to fill out a top 100, and might even make it to 200 if sanity would allow. My natural preference for older films will be is very much in evidence — the closest any “contemporary” performance came to making the cut was Gene Hackman for The Conversation — and only one of the performers cited is, in fact, still living. Feel free to agree or disagree with my choices, and mention any that you feel ought to have been included.

I realize that there are some purists out there who believe that Oscars should only be awarded for what falls under the traditional definition of “great acting” — that is to say, how an actor inhabits a role, how convincing or life-like they are as the character, how they

express themselves through their delivery of dialogue, outward displays of emotion, physical transformation, etc. I can’t fully agree with that assessment — if you want to be technical about it, the category is best performance by an actor in a lead or supporting role, and that term encompasses a whole lot more than what falls under the narrow definition outlined above. When people say that Mikhail Baryshnikov gave one of the greatest performances they’ve ever seen in Balanchine’s production of Swan Lake, or Jessye Norman in the title role in Tosca, they’re not talking about their acting, at least not in terms of what it is that makes the performance great. That being the case, I can say without hesitation that in Singin’ in the Rain, Gene Kelly gives one of the best, most skillful and most enjoyable performances in the history of motion pictures. For the record, I also think he does a good acting job, which is only incidental to what qualifies this performance for a mention on this list. Singin’ in the Rain represents Kelly at the pinnacle of his powers — the most complete and virtuosic demonstration of his ability and craft. Watching him dance the extended Broadway Rhythm ballet, lending his light, supple tenor to “You Were Meant for Me” or “You Are My Lucky Star,” navigating Hollywood traffic to get to Debbie Reynolds’ car with deftly executed acrobatics, or best of all, singing and dancing in the rain, is to understand what made Kelly one of the greatest talents the cinema has ever produced. The title number may be the purest expression of joy ever captured on film — a moment of unabashed euphoria that communicates more about the experience of being in love than anything any other actor could do with pages of dialogue. It is Kelly’s crowning achievement as an artist, and it deserved — at the very least — a nomination.

express themselves through their delivery of dialogue, outward displays of emotion, physical transformation, etc. I can’t fully agree with that assessment — if you want to be technical about it, the category is best performance by an actor in a lead or supporting role, and that term encompasses a whole lot more than what falls under the narrow definition outlined above. When people say that Mikhail Baryshnikov gave one of the greatest performances they’ve ever seen in Balanchine’s production of Swan Lake, or Jessye Norman in the title role in Tosca, they’re not talking about their acting, at least not in terms of what it is that makes the performance great. That being the case, I can say without hesitation that in Singin’ in the Rain, Gene Kelly gives one of the best, most skillful and most enjoyable performances in the history of motion pictures. For the record, I also think he does a good acting job, which is only incidental to what qualifies this performance for a mention on this list. Singin’ in the Rain represents Kelly at the pinnacle of his powers — the most complete and virtuosic demonstration of his ability and craft. Watching him dance the extended Broadway Rhythm ballet, lending his light, supple tenor to “You Were Meant for Me” or “You Are My Lucky Star,” navigating Hollywood traffic to get to Debbie Reynolds’ car with deftly executed acrobatics, or best of all, singing and dancing in the rain, is to understand what made Kelly one of the greatest talents the cinema has ever produced. The title number may be the purest expression of joy ever captured on film — a moment of unabashed euphoria that communicates more about the experience of being in love than anything any other actor could do with pages of dialogue. It is Kelly’s crowning achievement as an artist, and it deserved — at the very least — a nomination.Spencer Tracy was, in fact, nominated for best actor in 1958 — for his performance in an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea that managed to be both trite and stuffy at the same time. Right actor, right year…wrong performance. In John Ford’s

The Last Hurrah, Tracy is at his most engaged and assured — the role of an old-school, slightly shady machine politician, a shambling Irishman with a bit of the blarney in him, fits the actor like a well-worn glove, giving the Golden Age’s great naturalist the chance to show his full range. It’s a truly layered performance — irascible and slyly comic in one moment and frail and heartbreaking in the next, Tracy shows how the hyper-energized drive and charisma of an dynamic, outsized personality exists at painful odds with the weariness and strain of a body that can no longer comfortably accommodate such attributes. Several of Tracy’s 10 nominations seem more like ceremonial gestures made out of respect for the actor’s reputation than anything else — which is to say, all but a few seem to be based on the merits of the actual performances. Apart from the Hemingway adaptation, his four final best actor nominations came for playing grand old men delivering high-minded sermons; at some point, he stopped being an actor and became the nation’s conscience. The Last Hurrah brought out the mischief and the sadness in Tracy that few of his other later roles allowed him to express — it’s his most human and humane work as an actor.

The Last Hurrah, Tracy is at his most engaged and assured — the role of an old-school, slightly shady machine politician, a shambling Irishman with a bit of the blarney in him, fits the actor like a well-worn glove, giving the Golden Age’s great naturalist the chance to show his full range. It’s a truly layered performance — irascible and slyly comic in one moment and frail and heartbreaking in the next, Tracy shows how the hyper-energized drive and charisma of an dynamic, outsized personality exists at painful odds with the weariness and strain of a body that can no longer comfortably accommodate such attributes. Several of Tracy’s 10 nominations seem more like ceremonial gestures made out of respect for the actor’s reputation than anything else — which is to say, all but a few seem to be based on the merits of the actual performances. Apart from the Hemingway adaptation, his four final best actor nominations came for playing grand old men delivering high-minded sermons; at some point, he stopped being an actor and became the nation’s conscience. The Last Hurrah brought out the mischief and the sadness in Tracy that few of his other later roles allowed him to express — it’s his most human and humane work as an actor.He was known for most of his career as The Profile — a giant of the stage and an iconic figure of celebrity who never fully found his

bearings on film. He was never nominated for an Oscar, despite several successful films and a measure of standing within the film community. Truth be told, he was more than a bit past his prime by the time the medium of film came into its own, and was mostly content to coast on his reputation. At least once in the sound era, he did rise gloriously to the occasion, in a role that made full and hilarious use of his theatrical brio and larger-than-life persona. In Twentieth Century, Barrymore is pure ham — narcissistic, domineering, pompous, preening, more than slightly crazed and wickedly, wickedly funny. His Oscar Jaffe, a theatrical impresario trying to con his wayward protégé into coming back to him, has the bulging, burning eyes of a man possessed, the twisted Machiavellian grin of a cat eyeing the canary, and the ridiculously florid cadence of someone for whom the concept of going over the top exists only in theory — he’s a daffy Rasputin whose cunning and wit become even sharper with each additional marble he loses. Watching him and the peerless Carole Lombard driving each other into fits of hysteria with endlessly inventive bits of comic business is a wonder to behold.

bearings on film. He was never nominated for an Oscar, despite several successful films and a measure of standing within the film community. Truth be told, he was more than a bit past his prime by the time the medium of film came into its own, and was mostly content to coast on his reputation. At least once in the sound era, he did rise gloriously to the occasion, in a role that made full and hilarious use of his theatrical brio and larger-than-life persona. In Twentieth Century, Barrymore is pure ham — narcissistic, domineering, pompous, preening, more than slightly crazed and wickedly, wickedly funny. His Oscar Jaffe, a theatrical impresario trying to con his wayward protégé into coming back to him, has the bulging, burning eyes of a man possessed, the twisted Machiavellian grin of a cat eyeing the canary, and the ridiculously florid cadence of someone for whom the concept of going over the top exists only in theory — he’s a daffy Rasputin whose cunning and wit become even sharper with each additional marble he loses. Watching him and the peerless Carole Lombard driving each other into fits of hysteria with endlessly inventive bits of comic business is a wonder to behold.Bette Davis was just a run-of-the-mill contract player of (what was judged to be) average ability until she landed the role that put her on the map — and it was a role than nobody else wanted. Every major star in town passed on the project, and given the nature of the

material, it’s little wonder. Crass, trashy, thoroughly unremarkable in any respect other than her utter lack of sensitivity, the character of Mildred in Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage was the kind of blatantly unsympathetic role that looked and smelled like a career-killer. No shrinking violet, Davis saw it as a golden opportunity, and convinced Jack Warner (over his objections) to let her do it. The results were so startling and unnerving that they forever changed the rules for actresses in Hollywood. Screen heroines of the '20s and '30s were affected and refined — even the bad girls never succumbed to total ugliness, or raised their voices beyond a respectable decibel level. Such was the conviction and raw energy that Davis brought to her performance that it must have landed like a shovel to the stomach for audiences of the time. It still does. The actress didn’t allow vanity or caution to temper her portrayal of the role — her cockney tart is stupid and vulgar, an altogether ordinary woman incapable of any thought or feeling beyond her own narrow self-regard. She’s a nightmare version of Eliza Doolittle as imagined by Zola, only barely a level or two on the evolutionary ladder above grisly creatures risen from prehistoric muck….you can understand why Leslie Howard’s wimpy masochist doesn’t stand any kind of a chance against her. When he finally tries to break free of her clutches, Davis unleashes a raw working of anger and hostility unlike virtually any ever attempted on film. Contorting her face and body like a rabid dog pouncing on its prey while the bile issues forth from her twisted mouth, you cower in your seat at the sheer volcanic force of it. Only you can’t look away.

material, it’s little wonder. Crass, trashy, thoroughly unremarkable in any respect other than her utter lack of sensitivity, the character of Mildred in Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage was the kind of blatantly unsympathetic role that looked and smelled like a career-killer. No shrinking violet, Davis saw it as a golden opportunity, and convinced Jack Warner (over his objections) to let her do it. The results were so startling and unnerving that they forever changed the rules for actresses in Hollywood. Screen heroines of the '20s and '30s were affected and refined — even the bad girls never succumbed to total ugliness, or raised their voices beyond a respectable decibel level. Such was the conviction and raw energy that Davis brought to her performance that it must have landed like a shovel to the stomach for audiences of the time. It still does. The actress didn’t allow vanity or caution to temper her portrayal of the role — her cockney tart is stupid and vulgar, an altogether ordinary woman incapable of any thought or feeling beyond her own narrow self-regard. She’s a nightmare version of Eliza Doolittle as imagined by Zola, only barely a level or two on the evolutionary ladder above grisly creatures risen from prehistoric muck….you can understand why Leslie Howard’s wimpy masochist doesn’t stand any kind of a chance against her. When he finally tries to break free of her clutches, Davis unleashes a raw working of anger and hostility unlike virtually any ever attempted on film. Contorting her face and body like a rabid dog pouncing on its prey while the bile issues forth from her twisted mouth, you cower in your seat at the sheer volcanic force of it. Only you can’t look away.Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita features a spectacular trio of performances, with James Mason and scene-stealing Peter Sellers usually

commanding the bulk of the critical attention, but it’s Shelley Winters, in a career-best performance, that I keep coming back to. Winters’ Charlotte Haze, who has the bad luck of being the dumpy custodian to every middle-age man’s fantasy nymphette, is not, to put it mildly, the brightest bulb on the Christmas Tree. She’s a mass of silly pretensions and hormonal urges, driven in equal measure by a desire to attain of measure of sophistication and a panicky, menopausal sexual hunger. Of course, her ideas about what qualifies as sophisticated are mostly wrong, and her romantic ideals and sexual energies are woefully misplaced if not completely inappropriate. She's an clod who fancies herself the heroine in a play by Noel Coward; everything about her is based in folly, and it would be easy to write her off as a walking punchline — that is, if the actress didn’t give us such harrowing glimpses of the loneliness and desperation that have shaped her character’s ridiculousness. Of course, Winters is howlingly funny playing up her character’s vulgarity and idiocy, but what ultimately emerges is a genuinely tragic figure — one who is made all too achingly aware of her own pathetic limitations. Credit the talent and skill of Shelley Winters that Charlotte Haze is a joke that, in the end, is just too painful to laugh at.

commanding the bulk of the critical attention, but it’s Shelley Winters, in a career-best performance, that I keep coming back to. Winters’ Charlotte Haze, who has the bad luck of being the dumpy custodian to every middle-age man’s fantasy nymphette, is not, to put it mildly, the brightest bulb on the Christmas Tree. She’s a mass of silly pretensions and hormonal urges, driven in equal measure by a desire to attain of measure of sophistication and a panicky, menopausal sexual hunger. Of course, her ideas about what qualifies as sophisticated are mostly wrong, and her romantic ideals and sexual energies are woefully misplaced if not completely inappropriate. She's an clod who fancies herself the heroine in a play by Noel Coward; everything about her is based in folly, and it would be easy to write her off as a walking punchline — that is, if the actress didn’t give us such harrowing glimpses of the loneliness and desperation that have shaped her character’s ridiculousness. Of course, Winters is howlingly funny playing up her character’s vulgarity and idiocy, but what ultimately emerges is a genuinely tragic figure — one who is made all too achingly aware of her own pathetic limitations. Credit the talent and skill of Shelley Winters that Charlotte Haze is a joke that, in the end, is just too painful to laugh at.In 1940, Ginger Rogers dyed her trademark platinum tresses a dull shade of brown and got her Oscar — for serious hair and serious acting. Her earnest, unimaginative work in Kitty Foyle didn’t betray so much as an ounce of the spark and savvy that informed the performances for which she is cherished. There’s a charge and intelligence to Rogers’ work in Stage Door that the actress would never again equal in her career. Perhaps working alongside Katharine Hepburn brought out the best in her. They were the two biggest female stars at RKO in the 1930s — it was a notoriously unfriendly rivalry. Kate, along with everyone else, believed herself to be the better actress of the two,

and made it known in subtle ways that she didn’t really consider Ginger an equal — or a threat. Ginger was self-conscious, insulted, and ultimately, not one to back down from a fight. When the two trade barbs in their scenes together, what you’re hearing is an authentic battling rhythm fueled by genuine animosity and a spirit of competition. Maybe it took a slap in the face and a challenge to bring out both the toughness and the vulnerability in Ginger Rogers — whether that’s true or not, watching Stage Door, you’re glad it’s there, because the actress is unmistakably at the top of her form. As wisecracking chorine Jean Maitland, Rogers has a devastating way with a quip — her delivery of the film’s zingy one-liners is so quick, sharp and assured that it sounds like inspired improvisation. She’s a tough cookie, sure, but not immune to experiencing disappointment, or worse still, losing hope. The aspiring actresses at The Footlights Club live a precarious, uncertain existence — Rogers, more than any of the other performers, allows us to understand that comic banter is a necessary distraction from the fact that, at any moment, the girls might have their dreams and livelihoods taken away from them and fall off the grid. It’s not that Rogers simply lets us see the fear and fragility behind the snazzy retorts of these tart-tongued dames; she shows just how inextricably linked those seemingly self-contradictory properties are. She’s a smart-aleck blonde with a chip on her shoulder — as with any stand-up comedian, it’s the chip that’s the source of her comedy, even if the reality behind it is a source of hurt.

and made it known in subtle ways that she didn’t really consider Ginger an equal — or a threat. Ginger was self-conscious, insulted, and ultimately, not one to back down from a fight. When the two trade barbs in their scenes together, what you’re hearing is an authentic battling rhythm fueled by genuine animosity and a spirit of competition. Maybe it took a slap in the face and a challenge to bring out both the toughness and the vulnerability in Ginger Rogers — whether that’s true or not, watching Stage Door, you’re glad it’s there, because the actress is unmistakably at the top of her form. As wisecracking chorine Jean Maitland, Rogers has a devastating way with a quip — her delivery of the film’s zingy one-liners is so quick, sharp and assured that it sounds like inspired improvisation. She’s a tough cookie, sure, but not immune to experiencing disappointment, or worse still, losing hope. The aspiring actresses at The Footlights Club live a precarious, uncertain existence — Rogers, more than any of the other performers, allows us to understand that comic banter is a necessary distraction from the fact that, at any moment, the girls might have their dreams and livelihoods taken away from them and fall off the grid. It’s not that Rogers simply lets us see the fear and fragility behind the snazzy retorts of these tart-tongued dames; she shows just how inextricably linked those seemingly self-contradictory properties are. She’s a smart-aleck blonde with a chip on her shoulder — as with any stand-up comedian, it’s the chip that’s the source of her comedy, even if the reality behind it is a source of hurt.Sex on the silver screen has taken many different forms since the cinematic medium came into being. It can be smart and subtle, or bold and in-your-face. Sometimes it can be a tad lurid (or more than a tad) and erotically charged, other times it can be light, sophisticated fun. It can take the form of a smoldering slow-burn, creeping up on you gradually, or it can hit you right smack between the eyes like a

guided missile. At its very best, when it’s done correctly, it can encompass all of those things, and that’s where Lauren Bacall comes in. In To Have and Have Not, she is pure sex, and it’s no wonder the characters go through so many cigarettes even when they’re just making chit-chat. Foreplay never felt so good. The film marked Bacall’s film debut — not that you’d know it from watching her. Her performance is so smooth and knowing that it feels like the work of a seasoned professional. She was (by her own admission) still a virgin when she made it, and you wouldn’t know that either. Her performance is so smooth and knowing that it feels like the work of…never mind. Her character’s name is Slim, a shady lady stranded in exotic, dangerous Martinique (sort of an island stand-in for Casablanca), and when she strikes up a flirtation with Humphrey Bogart, the sparks all but burn holes in the celluloid. Her husky-voiced sultriness is utterly intoxicating, and when, in the film’s most oft-quoted sequence, she instructs Bogie’s Steve how to whistle, it’s a moment of pure magic. Even if you’ve seen the clip or heard the words before, in context, it still sends shivers down your spine. Had anyone before attempted such a forthright sexuality on the screen? Would anyone do so as successfully again? Bacall created the template for all sirens to follow, and very few (if any) have ever really measured up to it.

guided missile. At its very best, when it’s done correctly, it can encompass all of those things, and that’s where Lauren Bacall comes in. In To Have and Have Not, she is pure sex, and it’s no wonder the characters go through so many cigarettes even when they’re just making chit-chat. Foreplay never felt so good. The film marked Bacall’s film debut — not that you’d know it from watching her. Her performance is so smooth and knowing that it feels like the work of a seasoned professional. She was (by her own admission) still a virgin when she made it, and you wouldn’t know that either. Her performance is so smooth and knowing that it feels like the work of…never mind. Her character’s name is Slim, a shady lady stranded in exotic, dangerous Martinique (sort of an island stand-in for Casablanca), and when she strikes up a flirtation with Humphrey Bogart, the sparks all but burn holes in the celluloid. Her husky-voiced sultriness is utterly intoxicating, and when, in the film’s most oft-quoted sequence, she instructs Bogie’s Steve how to whistle, it’s a moment of pure magic. Even if you’ve seen the clip or heard the words before, in context, it still sends shivers down your spine. Had anyone before attempted such a forthright sexuality on the screen? Would anyone do so as successfully again? Bacall created the template for all sirens to follow, and very few (if any) have ever really measured up to it.1927 marked the inaugural year of the Academy Awards. The acting nominations were largely forgettable. It would have been a golden opportunity for the Academy to recognize one of the screen’s great comic geniuses giving, quite possibly, his very best performance. At the time of its release, however, The General was not regarded as a masterpiece, or really, as much of anything at all beyond a slight and amusing comedy that hadn’t made money. Just as Keaton’s lovelorn hero, Johnnie Gray, must suffer the indignities of rejection by

the draft board and the subsequent disdain of his prospective bride, the film’s true worth would not be recognized until it had proved itself over the course of time. Keaton’s acrobatic style, his daredevil attitude toward stuntwork and athletic enactment of the slapstick element, marked him as perhaps the most versatile physical comedian in the history of the medium. The Keaton persona functioned, on some level, as a contradiction in terms, and to glorious effect; the juxtapostion of the vibrant, hyper-animated physical comedy with a face that rarely changed expression (deadpan, dour stoicism) heightened the audience’s enjoyment of the routine. Keaton understood the value of contrast; while his body was forever in motion, contorting itself in sublime and ridiculous ways, the earnest expression always remained intact. In The General, his clowning is inspired, to be sure, but he also provides the audience with a character worth rooting for. Endearingly mawkish in his sweetheart’s presence, he must summon his inner hero when she is placed at risk. Johnnie Gray has a wistful obliviousness to everything going on around him, which only serves to enhance the comedy — his pursuit of his kidnapped ladylove is so single-minded, and his focus on his objective so intense, that he barely has time to register the dangers in his midst. It’s a deft, dextrous performance that impresses with more than just the technical skill that went into it; Keaton imbues his character with an indomitable spirit and a plucky refusal to accept defeat that put the audience firmly in his corner.

the draft board and the subsequent disdain of his prospective bride, the film’s true worth would not be recognized until it had proved itself over the course of time. Keaton’s acrobatic style, his daredevil attitude toward stuntwork and athletic enactment of the slapstick element, marked him as perhaps the most versatile physical comedian in the history of the medium. The Keaton persona functioned, on some level, as a contradiction in terms, and to glorious effect; the juxtapostion of the vibrant, hyper-animated physical comedy with a face that rarely changed expression (deadpan, dour stoicism) heightened the audience’s enjoyment of the routine. Keaton understood the value of contrast; while his body was forever in motion, contorting itself in sublime and ridiculous ways, the earnest expression always remained intact. In The General, his clowning is inspired, to be sure, but he also provides the audience with a character worth rooting for. Endearingly mawkish in his sweetheart’s presence, he must summon his inner hero when she is placed at risk. Johnnie Gray has a wistful obliviousness to everything going on around him, which only serves to enhance the comedy — his pursuit of his kidnapped ladylove is so single-minded, and his focus on his objective so intense, that he barely has time to register the dangers in his midst. It’s a deft, dextrous performance that impresses with more than just the technical skill that went into it; Keaton imbues his character with an indomitable spirit and a plucky refusal to accept defeat that put the audience firmly in his corner.Robert Walker was a very ordinary looking man with a very ordinary looking career. He spent the 1940s trading on his bland handsomeness by playing blandly wholesome boy-next-door types. He played them blandly. For anyone bored or disbelieving enough to challenge this assertion, his most notable films of the period are Since You Went Away and The Clock. The Age of Bloodless Blandness ended abruptly in

the mid-'40s when the actor’s life took a precipitous tailspin into hell. His wife, Jennifer Jones, left him for producer David O. Selznick, taking their two young sons with her. His career went nowhere. He started drinking, became paranoid and prone to suicidal depression. Alcoholism and the mental strain of believing the world was against him gradually eroded his boyish good looks. He had a breakdown, and was institutionalized briefly. Then he met Alfred Hitchcock. The rest of the industry had written him off as a bland nicety onscreen and a walking trainwreck off — but Hitch knew exactly what he was looking at, and exactly how to exploit it. For the record, Walker died within a year of having completed Strangers on a Train — it’s tempting to think that by surrendering so completely to the sad wreckage of his life and madness in order to give the performance of a lifetime, he quite simply had nothing left. In the film, Walker plays Bruno, the mercurial, demented and diabolical architect of another man’s near-undoing. Disturbed and disturbing, there’s an eerie calm to the character as Walker plays him; it’s as if he can’t help but smile, ruefully and with a certain degree of fatalistic pleasure, at the sad joke that his life has become and the misery that his mere existence can inflict on others. It’s difficult to know how much of Walker’s performance qualifies as acting and how much of it is the genuine spectacle of tortured soul giving way to his inner demons, drowning before our very eyes. Either way, it’s mesmerizing.

the mid-'40s when the actor’s life took a precipitous tailspin into hell. His wife, Jennifer Jones, left him for producer David O. Selznick, taking their two young sons with her. His career went nowhere. He started drinking, became paranoid and prone to suicidal depression. Alcoholism and the mental strain of believing the world was against him gradually eroded his boyish good looks. He had a breakdown, and was institutionalized briefly. Then he met Alfred Hitchcock. The rest of the industry had written him off as a bland nicety onscreen and a walking trainwreck off — but Hitch knew exactly what he was looking at, and exactly how to exploit it. For the record, Walker died within a year of having completed Strangers on a Train — it’s tempting to think that by surrendering so completely to the sad wreckage of his life and madness in order to give the performance of a lifetime, he quite simply had nothing left. In the film, Walker plays Bruno, the mercurial, demented and diabolical architect of another man’s near-undoing. Disturbed and disturbing, there’s an eerie calm to the character as Walker plays him; it’s as if he can’t help but smile, ruefully and with a certain degree of fatalistic pleasure, at the sad joke that his life has become and the misery that his mere existence can inflict on others. It’s difficult to know how much of Walker’s performance qualifies as acting and how much of it is the genuine spectacle of tortured soul giving way to his inner demons, drowning before our very eyes. Either way, it’s mesmerizing.Robert Mitchum had the easy, insolent manner of a guy who knew he’d never be taken seriously by the snobs and didn’t really give a shit. He was a maverick, and by Hollywood standards, a bit of a punk. The media pegged him for a dumb lug, an inarticulate slab of beefcake with biceps for brains and a bad boy attitude — it was an image that stuck for years, in spite of the fact that it bore very little relation to

the man himself; those who worked with him invariably described him as both highly intelligent and a consummate professional. He received but one nomination — as best supporting actor for an early role in The Story of G.I. Joe — while his four-plus decades of work as a star were completely ignored. As if to shame the establishment’s self-righteous sense of the natural order, the lunkhead produced a body of work which made the careers of his Oscar-winning contemporaries (such as David Niven, Hollywood’s Mr. Class President, for example) look shallow and irrelevant by comparison. From a bumper crop of egregiously overlooked performances, I submit The Night of the Hunter as his very best. As the wayward preacher whose gleaming smile disguises a black heart, the actor creates a study in villainy that manages to be both charming and chilling at the same time. Traditional movie sociopaths (and there are several on this list) are withdrawn and enclosed, wound as tightly as watches and wrapped up in their own inner torment. Mitchum’s Harry Powell has a big, expansive personality, with the engaging manner, sweeping cadence and seductive charm of a born evangelist. A not-so-distant cousin to Burt Lancaster’s Elmer Gantry, he’s equal parts false prophet and barnstorming huckster — butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth, and when he’s working his wiles on the gullible country boobs who comprise his congregation, they’re spoonfed easy-to-swallow morsels of fire and brimstone drenched in buttermilk gravy. He’s a counterfeit quarter that shines as brightly as a new silver dollar, and it’s only when you note the cold, dead look in his eyes that you can begin to hear the hollow ring of his sermons. It’s an astute, measured performance; the character is brazen, alright, but Mitchum resists the urge to turn him into a caricature. A cunning and deliberate predator as opposed to a wild-eyed maniac, Mitchum doesn’t run after his prey; whistling a tune, he strolls.

the man himself; those who worked with him invariably described him as both highly intelligent and a consummate professional. He received but one nomination — as best supporting actor for an early role in The Story of G.I. Joe — while his four-plus decades of work as a star were completely ignored. As if to shame the establishment’s self-righteous sense of the natural order, the lunkhead produced a body of work which made the careers of his Oscar-winning contemporaries (such as David Niven, Hollywood’s Mr. Class President, for example) look shallow and irrelevant by comparison. From a bumper crop of egregiously overlooked performances, I submit The Night of the Hunter as his very best. As the wayward preacher whose gleaming smile disguises a black heart, the actor creates a study in villainy that manages to be both charming and chilling at the same time. Traditional movie sociopaths (and there are several on this list) are withdrawn and enclosed, wound as tightly as watches and wrapped up in their own inner torment. Mitchum’s Harry Powell has a big, expansive personality, with the engaging manner, sweeping cadence and seductive charm of a born evangelist. A not-so-distant cousin to Burt Lancaster’s Elmer Gantry, he’s equal parts false prophet and barnstorming huckster — butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth, and when he’s working his wiles on the gullible country boobs who comprise his congregation, they’re spoonfed easy-to-swallow morsels of fire and brimstone drenched in buttermilk gravy. He’s a counterfeit quarter that shines as brightly as a new silver dollar, and it’s only when you note the cold, dead look in his eyes that you can begin to hear the hollow ring of his sermons. It’s an astute, measured performance; the character is brazen, alright, but Mitchum resists the urge to turn him into a caricature. A cunning and deliberate predator as opposed to a wild-eyed maniac, Mitchum doesn’t run after his prey; whistling a tune, he strolls.Beloved by the public, Charlie Chaplin was never fully embraced by Hollywood. Nor was he particularly trusted. His work, which always contained subtle social commentary even when it was at its most side-splittingly comic, was suspected of being subversive — even when those made most uneasy by it couldn’t fully grasp what made it so. Perhaps Hollywood wasn’t quite ready for comedy with a heart, or

worse still, a mind. He was nominated twice for best actor — first for The Circus, and again for The Great Dictator, which was deemed acceptable since it was in keeping with the political sympathies of the establishment (Hitler was the villain, as supposed to modern industry or class hypocrisy). His two undisputed masterpieces, City Lights and Modern Times, were left out in the cold. As a film, I slightly prefer the latter, but Chaplin probably gave his best and most heartfelt performance in City Lights. As one might expect, Chaplin’s talent for physical comedy is on full display in City Lights, in several ingeniously conceived and executed sequences (the boxing match is one of the funniest ever filmed). But what really makes the performance shine is its humanity — more so than in any other film he made, Chaplin’s Little Tramp exists as beacon of hope and kindness in a cold and unfeeling world. He’s a resilient everyman whose fundamental decency keeps him afloat in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. It would have been easy to cast himself as a victim — he’s bullied, batted around and generally humiliated by the callous “respectable” people he’s encounters, including the police, but he always retains his dignity and his belief in the existence of good in the world. That’s the reason people cry at the ending of the film — the sensitivity and compassion of Chaplin’s performance convince us that life, in spite of its cruelties, can truly be beautiful.

worse still, a mind. He was nominated twice for best actor — first for The Circus, and again for The Great Dictator, which was deemed acceptable since it was in keeping with the political sympathies of the establishment (Hitler was the villain, as supposed to modern industry or class hypocrisy). His two undisputed masterpieces, City Lights and Modern Times, were left out in the cold. As a film, I slightly prefer the latter, but Chaplin probably gave his best and most heartfelt performance in City Lights. As one might expect, Chaplin’s talent for physical comedy is on full display in City Lights, in several ingeniously conceived and executed sequences (the boxing match is one of the funniest ever filmed). But what really makes the performance shine is its humanity — more so than in any other film he made, Chaplin’s Little Tramp exists as beacon of hope and kindness in a cold and unfeeling world. He’s a resilient everyman whose fundamental decency keeps him afloat in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. It would have been easy to cast himself as a victim — he’s bullied, batted around and generally humiliated by the callous “respectable” people he’s encounters, including the police, but he always retains his dignity and his belief in the existence of good in the world. That’s the reason people cry at the ending of the film — the sensitivity and compassion of Chaplin’s performance convince us that life, in spite of its cruelties, can truly be beautiful.There are certain things in life I will never be able to explain or understand. I could not, for instance, explain the process by which a tennis match being played in Brazil can be viewed, live and as clear as daylight, in my living room here in Albany, NY — I take it for granted that it’s possible, but for the life of me, I have no idea how it happens. Similarly, I can’t even begin to fathom how Edward G. Robinson, in a career spanning more than 40 years, was not once ever nominated for an Academy Award. Was it the fact that no movie star has ever looked less like a movie star? Was he too old by the time he broke through, too much of a character actor as opposed to a traditional

leading man? Too much of a class act to play the campaigning game? Too Jewish? I have no idea. In any case, it’s a travesty which the Academy, bless them, attempted to correct with an honorary award toward the end of his life. I suppose it’s the thought that counts. In Billy Wilder’s classic tale of lust, murder and betrayal — generally regarded as the definitive film noir — Robinson plays Keyes, the chief claims investigator for an insurance company, who knows in his gut that “grieving widow” Barbara Stanwyck is a tarantula in sheep’s clothing. Dogged, determined, and shrewd to the point of having supernatural ability, Keyes is a bloodhound hot on the scent. He exists in the great tradition of classic sleuths such as Hercule Poirot — a keen student of human behavior with unimpeachable instincts, he doesn’t allow so much as the smallest detail to escape his bug-eyed vigilance. Such pillars of indefatigability can be one-note and wearying, often inspiring more admiration than affection, but Robinson makes Keyes such an endearingly idiosyncratic presence that you only sit back and marvel at his scowling certitude and inexhaustible vitality. Synapses clicking at warp speed, he paces back and forth while irritably chomping on his cigar in restless anticipation of a moment of clarity. When it inevitably comes, his face lights up like a kid on Christmas morning. You can understand how Fred MacMurray’s anxious murderer can’t help rooting for Keyes to figure it out, even though it means his own neck. As much fun as he is, Robinson’s performance ends on a note of almost unbearable grace and humanity. Having finally collared his criminal, all his hunches having born out, there is no room for celebration or smug self-satisfaction. Instead, Robinson shows us only disappointment, pity, and on some level, a rueful kind of empathy. Sometimes, there’s no pleasure to be had in having been right.

leading man? Too much of a class act to play the campaigning game? Too Jewish? I have no idea. In any case, it’s a travesty which the Academy, bless them, attempted to correct with an honorary award toward the end of his life. I suppose it’s the thought that counts. In Billy Wilder’s classic tale of lust, murder and betrayal — generally regarded as the definitive film noir — Robinson plays Keyes, the chief claims investigator for an insurance company, who knows in his gut that “grieving widow” Barbara Stanwyck is a tarantula in sheep’s clothing. Dogged, determined, and shrewd to the point of having supernatural ability, Keyes is a bloodhound hot on the scent. He exists in the great tradition of classic sleuths such as Hercule Poirot — a keen student of human behavior with unimpeachable instincts, he doesn’t allow so much as the smallest detail to escape his bug-eyed vigilance. Such pillars of indefatigability can be one-note and wearying, often inspiring more admiration than affection, but Robinson makes Keyes such an endearingly idiosyncratic presence that you only sit back and marvel at his scowling certitude and inexhaustible vitality. Synapses clicking at warp speed, he paces back and forth while irritably chomping on his cigar in restless anticipation of a moment of clarity. When it inevitably comes, his face lights up like a kid on Christmas morning. You can understand how Fred MacMurray’s anxious murderer can’t help rooting for Keyes to figure it out, even though it means his own neck. As much fun as he is, Robinson’s performance ends on a note of almost unbearable grace and humanity. Having finally collared his criminal, all his hunches having born out, there is no room for celebration or smug self-satisfaction. Instead, Robinson shows us only disappointment, pity, and on some level, a rueful kind of empathy. Sometimes, there’s no pleasure to be had in having been right.For the first decade of her career, Ingrid Bergman’s halo never touched the ground. She was nominated for best actress four times in the 1940s, twice for playing angelic victims of male cruelty, and twice for playing saints. Even her Ilsa in Casablanca was wholesome girl at heart whom no one would think twice about bringing home to mother. Her style was so open and natural that, as beautiful as she was, it was impossible to conceive of anything base or impure in her; in every role, she positively glowed. Thankfully, Alfred Hitchcock was either canny or perverse enough to see things in popular performers that other people hardly even dared to imagine. Cary Grant was the personification of breezy affability onscreen — his wives (there were five or so) described him as guarded and remote. Hitch was the only filmmaker ever to catch a whiff of the coldness in Grant, and in Suspicion (and even more explicitly in this film), he brought it to the forefront. Similarly, he was the only one who ever picked up on Ingrid Bergman’s inner wantonness — by the end of the '40s, the actress

would be embroiled in a tabloid sex scandal involving Italian director Roberto Rossellini, denounced on the floor of the U.S. Congress as a scarlet woman, and find herself blackballed by Hollywood for seven years. It was the kind of mess you’d expect Alicia Huberman, the character she played so memorably in Notorious, to find herself mixed up in. Unfortunately, in 1946, the Academy simply wasn’t ready to accept a more complicated version of their reigning virgin goddess. When we first encounter Bergman’s character, it comes as something of a shock. Instead of the serene enchantress we’ve come to expect, we see a dissolute, damaged woman consumed by self-loathing and working with reckless abandon towards her own self-destruction. She holds herself in even lower regard than the men whom she allows herself to be casually used by. In a cruel twist of fate, once she finally gains a measure of self-respect and a reason to reform, she must literally prostitute herself for her country’s benefit. Bergman shows us the hurt and shame her character feels when Grant refuses to acknowledge the ways in which she’s changed; his withering contempt only stiffens her resolve to prove her worth — to him and to herself. As a government spy married off to a Nazi criminal, her entire life has become a lie, but she’s never had more of a sense of purpose. In the second half of the film, Bergman registers the growing dread of someone who realizes she’s been employed as a sacrificial lamb and is walking a tightrope through a minefield; the slightest misstep could spell catastrophe, but she keeps her nerve. It’s a fearless, gutsy performance, not least because of the uninhibited sexuality Bergman gets to express — the famous single-take kissing scene, where Grant and Bergman make out for no less than four minutes while the camera orbits around them in swoony delight, is such a decadent feat of showmanship that it’s a wonder they got away with it. Bergman is no less radiant here than in her other performances, but Notorious was the only film brave enough to give her a sexual appetite.

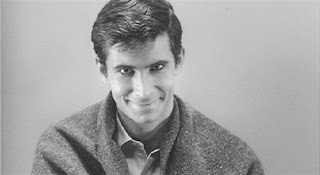

would be embroiled in a tabloid sex scandal involving Italian director Roberto Rossellini, denounced on the floor of the U.S. Congress as a scarlet woman, and find herself blackballed by Hollywood for seven years. It was the kind of mess you’d expect Alicia Huberman, the character she played so memorably in Notorious, to find herself mixed up in. Unfortunately, in 1946, the Academy simply wasn’t ready to accept a more complicated version of their reigning virgin goddess. When we first encounter Bergman’s character, it comes as something of a shock. Instead of the serene enchantress we’ve come to expect, we see a dissolute, damaged woman consumed by self-loathing and working with reckless abandon towards her own self-destruction. She holds herself in even lower regard than the men whom she allows herself to be casually used by. In a cruel twist of fate, once she finally gains a measure of self-respect and a reason to reform, she must literally prostitute herself for her country’s benefit. Bergman shows us the hurt and shame her character feels when Grant refuses to acknowledge the ways in which she’s changed; his withering contempt only stiffens her resolve to prove her worth — to him and to herself. As a government spy married off to a Nazi criminal, her entire life has become a lie, but she’s never had more of a sense of purpose. In the second half of the film, Bergman registers the growing dread of someone who realizes she’s been employed as a sacrificial lamb and is walking a tightrope through a minefield; the slightest misstep could spell catastrophe, but she keeps her nerve. It’s a fearless, gutsy performance, not least because of the uninhibited sexuality Bergman gets to express — the famous single-take kissing scene, where Grant and Bergman make out for no less than four minutes while the camera orbits around them in swoony delight, is such a decadent feat of showmanship that it’s a wonder they got away with it. Bergman is no less radiant here than in her other performances, but Notorious was the only film brave enough to give her a sexual appetite.There are other sociopaths on this list — Walker, Mitchum, and Cagney — but there was, and is, only one Psycho. For anyone who hasn’t seen it, proceed with caution — this entry includes some spoilers. As a young actor in Hollywood, Anthony Perkins never really fit in anywhere. Too skinny and self-consciously awkward to be a heartthrob, too delicately handsome to qualify as a character actor, in the 1950s he drifted with a reasonable degree of success through a series of juvenile roles, typically cast as a misunderstood adolescent. The fact that he never fully seemed comfortable in his own skin was only partially an act — Perkins was, up until the time of his death of AIDS in 1992, a closeted homosexual who was never able to shake the conviction that something was deeply wrong with him. From the late

1950s until his marriage in the 1970s, he received treatment from a controversial psychotherapist whose field of specialty was curing the “affliction” from which he suffered. Riddled with anguish and guilt, he never came to terms with who he was, nor managed to break free of the sense of stigma that was, to some degree, self-imposed. One of the themes to emerge from this assignment has been the canny ability of Alfred Hitchcock for pairing actors with roles that gave telling expression to their hidden selves. As Norman Bates, Perkins gives a painful account of an unformed personality, stunted in his growth by a cruel and overbearing mother who exerts her tyranny over him even from beyond the grave. A prisoner of his own isolation and sense of inadequacy, his attempts to reach out to another human being, Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane, are touching in their pathetic, halting ineptitude. For allowing himself to feel, whether it’s sexual attraction or simply a bond of kindred spirits, he must be punished, and the dispensing of bloody justice falls to his demonic alter ego. He simply isn’t equipped to handle the feelings that interaction with the kind, accepting Marion produces; in the end, both fall victim to Norman’s sense of shame. The way that Perkins registers the guilt and horror of what “Mother” has done is the crux of the film’s tragedy; the object of the murder is never to destroy Marion, but rather to suppress and ultimately extinguish the feelings that Norman has no means of coping with. It isn’t the celebrated shower scene that makes Psycho one of the most frightening films ever made; it’s the realization that Norman Bates isn’t a monster.

1950s until his marriage in the 1970s, he received treatment from a controversial psychotherapist whose field of specialty was curing the “affliction” from which he suffered. Riddled with anguish and guilt, he never came to terms with who he was, nor managed to break free of the sense of stigma that was, to some degree, self-imposed. One of the themes to emerge from this assignment has been the canny ability of Alfred Hitchcock for pairing actors with roles that gave telling expression to their hidden selves. As Norman Bates, Perkins gives a painful account of an unformed personality, stunted in his growth by a cruel and overbearing mother who exerts her tyranny over him even from beyond the grave. A prisoner of his own isolation and sense of inadequacy, his attempts to reach out to another human being, Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane, are touching in their pathetic, halting ineptitude. For allowing himself to feel, whether it’s sexual attraction or simply a bond of kindred spirits, he must be punished, and the dispensing of bloody justice falls to his demonic alter ego. He simply isn’t equipped to handle the feelings that interaction with the kind, accepting Marion produces; in the end, both fall victim to Norman’s sense of shame. The way that Perkins registers the guilt and horror of what “Mother” has done is the crux of the film’s tragedy; the object of the murder is never to destroy Marion, but rather to suppress and ultimately extinguish the feelings that Norman has no means of coping with. It isn’t the celebrated shower scene that makes Psycho one of the most frightening films ever made; it’s the realization that Norman Bates isn’t a monster.One of the most shocking realizations of my adult life is that “Over the Rainbow” is not, in fact, a great song. The melody is simplistic and the lyrics are sappy to the point of revulsion — that is, unless you can keep a straight face when hearing about troubles melting like lemon drops and happy little bluebirds flying over pretty rainbows. Otherwise, one must concede that it’s the kind of sugary junk that would give even the cuddliest of Care Bears a toothache. This painful realization came only after I’d heard someone other than Judy Garland try to sing it — a few other people actually, and mostly very accomplished performers. The folly lay in the attempt, for Garland’s rendition has never, and will never, be matched. It is, without question, the greatest single piece of music ever created for the screen and the most hauntingly poetic, if not for any of its own qualities, then quite simply because she sang it. Make no mistake — there’s a lot more to the performance than “Over the Rainbow.” No role, with the possible exception of A Star is Born, made more demands of Garland as an actress, and not even the 1954 film brought her vulnerability as strongly into focus. As with the majority of the performances on this list, there’s a story behind the story — and perhaps no other characterization was informed as strongly by an actor’s reality. Although she is most closely associated with the timeless children’s tale by L. Frank Baum, Garland’s own childhood bore a closer resemblance to something out of The Brothers Grimm. At the age of 13, Frances Gumm was sold to MGM by an apathetic father and

opportunistic mother, neither of whom saw any need to question the studio’s peculiar practices regarding the management and maintenance of juvenile talent. In the dark, quasi-Dickensian era before the passage of child labor laws, the rechristened Judy Garland became a full-time working professional, was prevented from pursuing much of a social life beyond the iron gates of the studio, given pills to help manage her weight, and still more pills to see her through the grueling 14 hour work days. The scars of these early years, which the actress would ruefully recall as among the most difficult in her life, would never fully heal. Life only became more complicated with the transition to adulthood. As a film, The Wizard of Oz may be about as far away from realism one can get; yet somehow, in the midst of all the Technicolor sorcery, Judy Garland creates a character based in recognizable truth. It’s a deceptively simple, natural performance; in a way, Judy Garland and Dorothy Gale are one in the same, trying to make sense of the world around them and their own unspoken fears and insecurities. There’s a scene that stands out for me – when she’s trapped in the witch’s tower, terrified and alone, she cries out for Auntie Em (“Auntie Em, I’m frightened…”). The emotion that fuels the scene is visceral and genuine — doubtless Garland could relate to the desperate need for some kind of stable, nurturing influence, not only to shield and protect, but dispel the darkness that exists just beneath the surface of the wonderful world of make-believe and fantasy (Oz could just as easily be Hollywood). When she sings “Over the Rainbow,” leaning against a haystack and gazing wistfully up to the skies, it’s the ultimate expression of the inchoate yearnings of adolescence, the need for acceptance and deliverance from isolation and loneliness. The song promises escape to a world where contentment and freedom from worry are attainable properties. Listen closely to Judy Garland when she sings the words — she means them. The simplicity and the conviction with which the character’s inner life is made explicit in this moment is a marvel to behold — sad, beguiling and utterly haunting. Whenever the actress would perform “Over the Rainbow” in numerous late-career concert appearances, she did so with a catch in her voice and a tear in her eye — on some occasions she’d be sobbing profusely by the song’s conclusion. It’s more likely than not that there was an element of showmanship in these displays, but her delivery revealed the existence of something more — a sad recognition of the fact that, unlike the character she played, Judy Garland never quite made it to that place where troubles melt like lemon drops and dreams really do come true. Real life doesn’t often afford such opportunities.

opportunistic mother, neither of whom saw any need to question the studio’s peculiar practices regarding the management and maintenance of juvenile talent. In the dark, quasi-Dickensian era before the passage of child labor laws, the rechristened Judy Garland became a full-time working professional, was prevented from pursuing much of a social life beyond the iron gates of the studio, given pills to help manage her weight, and still more pills to see her through the grueling 14 hour work days. The scars of these early years, which the actress would ruefully recall as among the most difficult in her life, would never fully heal. Life only became more complicated with the transition to adulthood. As a film, The Wizard of Oz may be about as far away from realism one can get; yet somehow, in the midst of all the Technicolor sorcery, Judy Garland creates a character based in recognizable truth. It’s a deceptively simple, natural performance; in a way, Judy Garland and Dorothy Gale are one in the same, trying to make sense of the world around them and their own unspoken fears and insecurities. There’s a scene that stands out for me – when she’s trapped in the witch’s tower, terrified and alone, she cries out for Auntie Em (“Auntie Em, I’m frightened…”). The emotion that fuels the scene is visceral and genuine — doubtless Garland could relate to the desperate need for some kind of stable, nurturing influence, not only to shield and protect, but dispel the darkness that exists just beneath the surface of the wonderful world of make-believe and fantasy (Oz could just as easily be Hollywood). When she sings “Over the Rainbow,” leaning against a haystack and gazing wistfully up to the skies, it’s the ultimate expression of the inchoate yearnings of adolescence, the need for acceptance and deliverance from isolation and loneliness. The song promises escape to a world where contentment and freedom from worry are attainable properties. Listen closely to Judy Garland when she sings the words — she means them. The simplicity and the conviction with which the character’s inner life is made explicit in this moment is a marvel to behold — sad, beguiling and utterly haunting. Whenever the actress would perform “Over the Rainbow” in numerous late-career concert appearances, she did so with a catch in her voice and a tear in her eye — on some occasions she’d be sobbing profusely by the song’s conclusion. It’s more likely than not that there was an element of showmanship in these displays, but her delivery revealed the existence of something more — a sad recognition of the fact that, unlike the character she played, Judy Garland never quite made it to that place where troubles melt like lemon drops and dreams really do come true. Real life doesn’t often afford such opportunities.Rosalind Russell was a tall, almost ungainly woman with a raspy contralto voice and plain, sensible features. Her non-nonsense appearance, which was smart and well-tailored without being austere, suggested both a practical outlook and a bemused sense of irony. No one would ever mistake her for an ingénue or a sex goddess, which probably suited her just fine. Never beautiful in the conventional sense, she could generate more heat with an arched eyebrow and a deadpan retort than any of the glamour girls could with smoldering looks and coy

displays of their natural assets. She could be delightfully over-the-top in films that tapped into the zanier side of her nature — Auntie Mame is probably still the role with which she is most identified — but it’s His Girl Friday that really showcases the full and glorious spectrum of her talent. The role of Hildy Johnson was originally written for a man, and in its transmogrified incarnation could have easily come across as a shrill, insulting parody of the tough-minded career woman as a masculine (or worse still, asexual) entity. But Rosalind Russell was much too smart, and far too inventive, to fall into that trap — her Hildy is one of the boys, alright, but she’s more woman than ever. For the first time in motion pictures, here was a truly modern woman — not only the professional equal of her male counterparts, but with a quickness and creativity that leaves them in the dust. Russell’s Hildy is an ace reporter who can outtalk, outthink and out-maneuver every man in the room, and rather than resent her for it, they can only peer out from under their porkpie hats and newsman’s visors with a mixture of awe and respect as she runs circles around the rest of them. The actress is a whirling dervish of energy, and you’ll be amazed at how fast her motor runs — she sprints through entire pages of dialogue at warp speed without missing a beat, and her inflections throughout are priceless. She throws herself into the part with the same kind of edgy, go-for-broke tenacity that her character exhibits when chasing headlines, and makes it clear that, for Hildy Johnson, no other kind of life is possible. She needs the thrill of the chase, and a guy like Walter Burns who can not only keep up with her, but is only too happy to let her run with the wolves. That’s why nice, bland Ralph Bellamy has to be sent packing at the end of the picture — there’s no way he could avoid being blown away by this sonic boom in heels.

displays of their natural assets. She could be delightfully over-the-top in films that tapped into the zanier side of her nature — Auntie Mame is probably still the role with which she is most identified — but it’s His Girl Friday that really showcases the full and glorious spectrum of her talent. The role of Hildy Johnson was originally written for a man, and in its transmogrified incarnation could have easily come across as a shrill, insulting parody of the tough-minded career woman as a masculine (or worse still, asexual) entity. But Rosalind Russell was much too smart, and far too inventive, to fall into that trap — her Hildy is one of the boys, alright, but she’s more woman than ever. For the first time in motion pictures, here was a truly modern woman — not only the professional equal of her male counterparts, but with a quickness and creativity that leaves them in the dust. Russell’s Hildy is an ace reporter who can outtalk, outthink and out-maneuver every man in the room, and rather than resent her for it, they can only peer out from under their porkpie hats and newsman’s visors with a mixture of awe and respect as she runs circles around the rest of them. The actress is a whirling dervish of energy, and you’ll be amazed at how fast her motor runs — she sprints through entire pages of dialogue at warp speed without missing a beat, and her inflections throughout are priceless. She throws herself into the part with the same kind of edgy, go-for-broke tenacity that her character exhibits when chasing headlines, and makes it clear that, for Hildy Johnson, no other kind of life is possible. She needs the thrill of the chase, and a guy like Walter Burns who can not only keep up with her, but is only too happy to let her run with the wolves. That’s why nice, bland Ralph Bellamy has to be sent packing at the end of the picture — there’s no way he could avoid being blown away by this sonic boom in heels.The cartoon shenanigans of contemporary action and horror films are pretty tame fare compared to a show of genuine violence — whether expressed through deeds, behavior, or even something as simple as an attitude. Explosions and decapitations are all fine and good, and may even prompt a few happy hours of shrieking in the dark. But real violence — when it’s given a human face — can still make audiences squirm in their seats, and the sense of discomfort it produces can be much harder to shake in the days and weeks afterward. Cagney was emblematic of the movie tough guy — the pint-size bruiser from the wrong side of the tracks whose scrappy belligerence could detonate into bloody mayhem at a moment’s notice. It took a while for the Academy to get over their initial response of shock. His star-making turn in The Public Enemy was ignored, and an even more galvanizing performance in Angels with Dirty Faces was pushed to the

side in favor of Spencer Tracy’s benign Father Flannagan in Boys Town. It was only when Cagney stopped being scary and starting playing nice — for his spry, ingratiating turn in Yankee Doodle Dandy — that the Academy relented and awarded him his Best Actor trophy. The award was deserved, certainly, but the impact of that performance pales in comparison to what would become the actor’s most frightening and indelible creation. Once again, Oscar was too busy averting his gaze, most likely out of fear, to give the devil his due. For the role of Cody Jarrett, for whom the term ‘mentally imbalanced’ would only barely scratch the surface, Cagney dug deeper than he ever had before, and revealed a naked emotionalism that was all the more startling for its proximity to his character’s psychotic impulses. Jarrett is a ticking time bomb of a human being, given to panic attacks and fainting spells (shades of Tony Soprano) and apt to unleash his volcanic anger upon anyone or anything in his path at any given moment. He’s defensive, defiant, and gleefully unhampered by anything akin to a moral compass. Unable to experience anything like joy or remorse, he is almost equally incapable of love….almost, that is, because of the pathological attachment he has toward his rotten old crone of a mother. When he hears of her death in prison, Cagney’s trademark sneer gives way to a working of grief and pain that is so raw in its intensity that it tears right through the fourth wall and grips the audience by the throat. The time bomb has finally gone off, and it keeps going off over and over again. Reduced to a wounded animal, Cagney rages blindly through his despair, moaning, howling, punching at the wind. It’s unthinkable that any other actor of the golden era would be willing to make himself so utterly pathetic and wretched in service to his concept of character — nowadays, it’s used as the kind of flashy pyrotechnical trick employed to garner nominations. With Cagney, it amounted to sheer nerve.

side in favor of Spencer Tracy’s benign Father Flannagan in Boys Town. It was only when Cagney stopped being scary and starting playing nice — for his spry, ingratiating turn in Yankee Doodle Dandy — that the Academy relented and awarded him his Best Actor trophy. The award was deserved, certainly, but the impact of that performance pales in comparison to what would become the actor’s most frightening and indelible creation. Once again, Oscar was too busy averting his gaze, most likely out of fear, to give the devil his due. For the role of Cody Jarrett, for whom the term ‘mentally imbalanced’ would only barely scratch the surface, Cagney dug deeper than he ever had before, and revealed a naked emotionalism that was all the more startling for its proximity to his character’s psychotic impulses. Jarrett is a ticking time bomb of a human being, given to panic attacks and fainting spells (shades of Tony Soprano) and apt to unleash his volcanic anger upon anyone or anything in his path at any given moment. He’s defensive, defiant, and gleefully unhampered by anything akin to a moral compass. Unable to experience anything like joy or remorse, he is almost equally incapable of love….almost, that is, because of the pathological attachment he has toward his rotten old crone of a mother. When he hears of her death in prison, Cagney’s trademark sneer gives way to a working of grief and pain that is so raw in its intensity that it tears right through the fourth wall and grips the audience by the throat. The time bomb has finally gone off, and it keeps going off over and over again. Reduced to a wounded animal, Cagney rages blindly through his despair, moaning, howling, punching at the wind. It’s unthinkable that any other actor of the golden era would be willing to make himself so utterly pathetic and wretched in service to his concept of character — nowadays, it’s used as the kind of flashy pyrotechnical trick employed to garner nominations. With Cagney, it amounted to sheer nerve.Where was the love for Humphrey Bogart? It finally revealed itself in 1951 when the criminally neglected actor received his one and only Oscar for his delightful performance in The African Queen. Taking nothing away from his acting in that film, it would have been just as nice if they’d acknowledged him when he’d really deserved it. His one prior nomination had been for Casablanca; history shows that he lost to someone named Paul Lukas, whose performance in Watch on the Rhine now registers as a complete zero — neither good nor bad enough to be memorable in any way, shape or form (it’s the kind of performance you’ll forget about even while you’re watching it). Bogart was not nominated for — among other things — The Maltese Falcon, High Sierra, To Have and Have Not,

The Big Sleep, In a Lonely Place and most shockingly of all, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. John Huston’s masterpiece, an unlikely fusion of film noir and western, is an intricately structured morality tale examining the corruptive influence of greed; as observed here, not only does it take away men’s souls, it erodes their sanity as well. Bogart plays Fred C. Dobbs, a down-and-out wastrel who is reduced to a state of twitching paranoia when he hits the mother lode, a mountain rich with untapped gold deposits. As the wealth accumulates, it brings with it an atmosphere of tension and mistrust. The actor creates an unflinching, harrowing study of a man unraveling before our very eyes, struggling to hold onto whatever clarity he may still possess and losing the battle in a spectacular fashion. Bogart’s monologues, when the character begins talking to himself (often referring to himself in the third person), are stunningly executed — they build in intensity as the character’s incipient hysteria bubbles to the surface and a sense of crazed panic overtakes his instincts. This was a Bogart no one had seen before — the consummate movie tough guy as the living embodiment of weakness…a loser. The physical transformation alone is striking, and not because the actor’s appearance was radically altered for the role, the change has more to do with body language. Whereas other Bogart performances are remarkable for their calm self-possession — their stillness, if you will — here the actor is a mass of tics and twitches, a walking catalog of the visible markings of human frailty. His slumped shoulders, the halting step of his walk, the slight tremor in his hands, and his darting eye movements communicate volumes about where Fred C. Dobbs has been, and the even darker depths toward which he’s bound.

The Big Sleep, In a Lonely Place and most shockingly of all, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. John Huston’s masterpiece, an unlikely fusion of film noir and western, is an intricately structured morality tale examining the corruptive influence of greed; as observed here, not only does it take away men’s souls, it erodes their sanity as well. Bogart plays Fred C. Dobbs, a down-and-out wastrel who is reduced to a state of twitching paranoia when he hits the mother lode, a mountain rich with untapped gold deposits. As the wealth accumulates, it brings with it an atmosphere of tension and mistrust. The actor creates an unflinching, harrowing study of a man unraveling before our very eyes, struggling to hold onto whatever clarity he may still possess and losing the battle in a spectacular fashion. Bogart’s monologues, when the character begins talking to himself (often referring to himself in the third person), are stunningly executed — they build in intensity as the character’s incipient hysteria bubbles to the surface and a sense of crazed panic overtakes his instincts. This was a Bogart no one had seen before — the consummate movie tough guy as the living embodiment of weakness…a loser. The physical transformation alone is striking, and not because the actor’s appearance was radically altered for the role, the change has more to do with body language. Whereas other Bogart performances are remarkable for their calm self-possession — their stillness, if you will — here the actor is a mass of tics and twitches, a walking catalog of the visible markings of human frailty. His slumped shoulders, the halting step of his walk, the slight tremor in his hands, and his darting eye movements communicate volumes about where Fred C. Dobbs has been, and the even darker depths toward which he’s bound.In a career filled with wonderful characters and performances, Katharine Hepburn always was her own greatest creation. In the 1930s, she stood apart from the crowd; none of her contemporaries could touch her for originality, incisiveness or audacity. Very few films she made in the early stages of her career had the courage to run with her — at her worst, and sometimes even at her best, she could seem hopelessly affected and refined, too rare a bird to be credible as a mere mortal. She was occasionally a tomboy, but always with an element of idiosyncratic New England exoticism — a haughty Bryn Mawr elitism coupled with an air of high-starch Yankee breeding. She was not the obvious choice for the role of a dizzy heiress in a screwball comedy directed by Howard Hawks — that would have been Carole Lombard. Offbeat casting decisions often yield the highest dividends. Bringing Up Baby is nearly everyone’s favorite Katharine Hepburn

film, and features arguably the best performance she ever gave. As Susan Vance, Hepburn decided to throw caution to the wind and let down her hair — there’s a spirit of giddy abandon in her performance, a willingness to act silly and be silly, that frees the actress from her own confining persona while at the same time referencing it in sly, nodding fashion. In a way, Hepburn spends much of the film poking fun at Hepburn. Susan has a refinement of manner and speech — doubtless the product of years of scrupulous training at the tawny prep schools and top-drawer society functions — but there’s a brittle frivolity to her cadence and attitudes that makes it impossible to take her too seriously (I could listen to clipped delivery of “No…to drop an olive…” all day long). Acting on whim and a freewheeling improvisatory logic that she alone can follow, she’ll say and do whatever pops into her head, with a blithe indifference to the precepts of decorum or any measure of reason. She seems to thrive on chaos - it brings out the romantic, adventurous side of her nature, and makes her impulsiveness that much more pronounced. When ever she utters her chirpy catchphrase — the ominous “Everything’s going to be alright” — the other characters hold their breath, waiting for the other show to drop. Breezing through the din like a typhoid Mary on roller skates, Hepburn is blissfully uninhibited and deliriously funny from start to finish; her teamwork with Cary Grant, as the bespectacled paleontologist who becomes the hapless object of her unwanted attentions, is one of the most exhilarating examples of great comic teamwork in all of films. There are so many moments to cherish — perhaps none more so when Hepburn dons the persona of ‘Swingin’ Door Susie,’ an East Side debutante’s hilariously off-kilter approximation of a hard-bitten gun moll. As much fun as she seems to be having, the actress never loses sight of what drives Susan’s eccentric and erratic behavior; at heart, she’s just a lovestruck, sentimental goof who just can’t keep her emotions in check long enough to act like a normal human being. Thank God.