Saturday, March 26, 2016

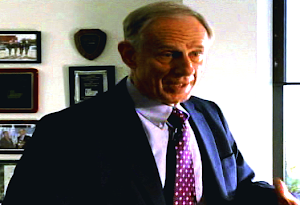

Memories of Edward Copeland

For a time at my home blog, Thrilling Days of Yesteryear, I meticulously documented the passings of people in the entertainment industry in the form of personal obituaries. This is not as easy as it sounds: a good percentage of those who had gone on to their greater reward were individuals with whose body of work I often had no familiarity…and so I would have to think of some clever way to write a few lines of regret that they were no longer working and living among us. Eventually, all this reporting on death got in the way of my regular writing at TDOY…and as such, I reluctantly phased it out.

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, December 08, 2014

I read the news today — oh boy

Sunday, February 02, 2014

Philip Seymour Hoffman (1967-2014)

Boogie Nights marked Hoffman's second film with Anderson following Hard Eight. They would team again in Magnolia, Punch-Drunk Love and The Master, which earned Hoffman an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor, his fourth overall. He also received supporting nods for Doubt and Charlie Wilson's War and won on his first try, his only nomination in the lead category, for Capote.

Though his film career only began in 1991, it proved to prolific. Once his fame and reliability grew, even if some of the films he appeared in weren't so great, I never saw him give a bad performance. A cattle call of some of my favorite Hoffman performances: Happiness, The Talented Mr. Ripley, 25th Hour, The Savages, Before the Devil Knows You're Dead, Moneyball and The Ides of March.

The performance perhaps closest to my heart was his turn as legendary rock journalist Lester Bangs in Cameron Crowe's Almost Famous. I also loved his work in two less well-known films: Owning Mahowny and Jack Goes Boating, a role he originated in the off-Broadway production and he also directed the film.

He appeared on Broadway three times and received a Tony nomination each time. His first came in the inaugural Broadway production of Sam Shepard's True West, where he and John C. Reilly alternated the lead roles at different performances. He earned a featured actor nod in the star-studded, highly praised revival of O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night starring Brian Dennehy and Vanessa Redgrave. His third nomination came for taking on Willy Loman in a revival of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman.

RIP Mr. Hoffman.

Tweet

Labels: Arthur Miller, O'Neill, Obituary, Oscars, P.S. Hoffman, Shepard, Theater, Vanessa Redgrave

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Saturday, February 01, 2014

Maximilian Schell (1930-2014)

Schell received two other Oscar nominations in his film career as best actor: in 1975's The Man in the Glass Booth and as supporting actor in 1977's Julia. He also received two Emmy nominations for the TV films Stalin and Miss Rose White in the early '90s. He appeared on Broadway three times, the first time in 1958 in Interlock, the same year his first English-language film, The Young Lions, came out. His third appearance came in 2001 in a stage production of Judgment at Nuremberg, this time playing the role of Dr. Ernst Janning whom Burt Lancaster played in the 1961 film.

Shortly after his Oscar win, he joined the cast of thieves in Jules Dassin's 1964 Topkapi. The first exposure to Schell's work for many in my generation probably came from silly 1979 sci-fi flick The Black Hole. He also played the erstwhile villain opposite James Coburn in one of the lesser Sam Peckinpah effort, 1977's Cross of Iron. He appeared in many films and roles for television both in the U.S. and abroad, including a six-episode stint on Wiseguy.

He also directed, most notably the remarkable 1984 documentary Marlene, where Marlene Dietrich reflected on her life without ever letting herself be seen in her current state.

Of all Schell's roles though, I always maintain a soft spot in my heart for his role as eccentric chef Larry London in Andrew Bergman's great comedy The Freshman with Marlon Brando doing a pitch-perfect parody of his own Vito Corleone.

RIP Mr. Schell.

Tweet

Labels: Awards, Brando, Dassin, Documentary, James Coburn, Lancaster, Marlene, Obituary, Oscars, Peckinpah, Television, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, January 12, 2014

Love Hurts

Why do we always hurt the ones we love?

Anyone who’s been a part of any kind of significant relationship, whether of the familial or romantic variety, has been given to ponder the paradoxical nature of those thorny, forged-in-fire entanglements. As evidenced by the brutal, bruising verbal brickbats the family members of August: Osage County lob at each other’s heads like hand grenades, no one can inflict quite as much damage as one’s nearest and dearest. This axiom may be most commonly applied in reference to human interaction, but it holds equally true when considering a writer and his work.

Anyone who’s ever put pen to paper — or, in this modern age, spent hours staring at a blinking monitor — knows that the peculiar bond between a scribe and his prose can be as complex and as intimate as that of any of the human variety. Many playwrights and novelists have likened their labors to the birthing process, and discuss their work in the same way that parents talk about their children. By that definition, writers who do harm to their own creations can be charged — at least, on some metaphysical plane — with child abuse.

This is not to cast aspersions on the character of Tracy Letts, who has adapted his Pulitzer Prize-winning play for the screen, and whom I suspect is only minimally to blame for what has happened to it (nothing good) en route. Still and all, it begs the eternal question: Why do we hurt the ones we love? As far as selling a book or a play to the movies is concerned, nine times out of ten, the road to perdition is paved with good intentions.

Rather than veering too far off course into the realm of psychoanalytic introspection, it may be best to consider the history of the property in question. August: Osage County premiered in the summer of 2007 at The Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago. The production subsequently moved to Broadway in the fall of 2008, with most of its original cast intact. It remained ensconced on The Beltway for a year and a half — a rare feat for a non-musical production not featuring a movie or TV star — picking up virtually every major award along the way. I saw the production three times over the course of its run — anyone familiar with Broadway pricing will recognize that this represents a sacrifice — and reviewed it for this site in 2009. It is not an overstatement to say that, then as now, I regard it as one of the highlights of my life’s theatergoing experience. Admittedly, I am not the ideal person to review the film adaptation, since I cannot approach the material with any kind of objectivity. Nor would I want to. Even if it’s a fundamental part of our nature to hurt the ones we love, it doesn’t follow that we enjoy doing it.

Nevertheless, when the owner and proprietor of this blog calls me up for active duty, I do my best to answer the call. In interest of full disclosure, I must state that while I tried to approach the assignment with an open mind, personal prejudice (did I mention how much I loved the show on Broadway?) has gotten the better of me to some degree. Oddly enough, without that pre-existing prejudice, my response toward the film might have been even less felicitous than it is now.

It’s bad form when reviewers reference other critics’ opinions to reinforce and/or validate their own position. The mere act of doing so suggests lack of confidence in one’s opinion. That said, one of the things I’ve been struck (and depressed) by is the manner in which many non-theatergoing critics have suggested, based solely on their reaction to the film version, that August: Osage County is not, and in fact never could have been, much of a play. The critic for The New York Times, while allowing that that the material may have been “mishandled…(in its) transition from stage to screen,” pondered whether that transition may have “exposed weak spots in (Letts’) dramatic architecture and bald spots in his writing.” On the opposite coast, the scribe for The Los Angeles Times took it a step further in declaring that while he had not seem the stage incarnation, “nothing about this film version makes me regret that choice.”

I suspect many people on the receiving end of years’ worth of glowing testimonials will react in much the same fashion. Anyone experiencing director John Wells’ hamfisted, ultimately rather conventional Hollywood treatment of family dysfunction without a suitable frame of reference may well be given to wonder, “Is this what all the fuss was about?” Advance reports suggested that the filmmakers made a deliberate effort to brighten things up, even going so far as to tack on a happy ending. That’s not the case. While truncated, the play has not been radically revised. In a certain sense, that’s good news. The bad news is that fundamental fidelity to the text doesn’t bring this baby snugly into port. You could rewrite every line and still arrive at something that felt closer in spirit and purpose to what Letts created for the stage than what Wells and company have come up with. As played for cozy camp by a cast of Hollywood heavyweights, the material has not been softened as much as it has been neutered.

For a sharp-fanged predator used to trolling the wild with confidence, this has an effect of bland domestication, despite the fact that its path through the jungle remains essentially the same. What sets the plot in motion is the mysterious disappearance of Beverly Weston (Sam Shepard), the craggy, alcoholic patriarch of an extended clan that includes three daughters, one grandchild and an assortment of in-laws. A noted poet whose output didn’t extend beyond one fledgling success, Beverly has a habit of going missing without so much a heads up to his nearest and dearest. This time, however, his absence has an unmistakable air of finality. No one can be quite certain whether he’s alive or dead, but the likelihood of his coming back seems slim to none. One by one, the far-flung Weston children, two of whom have wisely chosen to get themselves as far away from Mom and Dad as humanly possible, descend upon the family homestead en masse to try to piece together exactly what happened to Dad, and what in hell to do about mother Violet (Meryl Streep), a chain-smoking, pill-popping, cancer-riddled gorgon who shows no signs of becoming more manageable now that her chief antagonist has vanished without a trace. Leading the charge is pragmatic, sardonic Barbara (Julia Roberts, keeping that million-dollar smile firmly under wraps), who isn’t about to let Mom off the hook without answering a few questions. Of course, when you start digging for the truth, there’s no telling what sort horrors you may uncover. As it turns out, there are good and plenty festering away in the crypt of family secrets, and Violet is perfectly willing to invite them out to dance.

Even as I lavished praise upon the play and the production in my original review, I did so with the caveat that August: Osage County was not a revolutionary work of theater, nor even a particularly original one. Borrowing liberally from Eugene O’Neill, Lillian Hellman and Sam Shepard, among others, the play harks back to the classic traditions of American drama while reinvigorating the tried-and-true machinery of melodrama with brazen, jolting theatricality. The chief mistake Wells has made for the purposes of the film version – besides some critically misjudged casting choices — is in his confusion of theatricality with camp. He encourages his cast members to go for the easy laughs whenever they can, and irons out the characters’ idiosyncrasies to the point that their behavior seems almost quaint. When Violet and Barbara literally come to blows in the climatic dinner table scene, it’s like watching Joan Collins and Linda Evans wrestling on the marble foyer at Carrington Manor. It’s outrageous, to be sure, but not particularly shocking. Without the emotional resonance that original stage players Deanna Dunagan and Amy Morton brought to the proceedings, under the skillful direction of Anna D. Shapiro, what you’re left with feels more along the lines of a live action cartoon.

While the sins of the director shouldn't be heaped at feet of the playwright, Letts' screenplay adaptation doesn’t help matters much. The clunky efforts at opening up the piece for the screen, taking the action out of doors at select intervals, never feel like an organic extension of the action. The element of claustrophobia that contributed so much to the proceedings onstage, in the rambling Pawhuska, Okla., farmhouse with its shades drawn tight to keep out light and air, has been jettisoned in favor of woebegone glimpses of parched prairies. Certain nuances inevitably fall by the wayside when condensing a 3 hour play into a 2 hour film, and while the cuts do not fundamentally alter the dramatic structure, the action occasionally feels rushed, as if the filmmakers were working on a limited budget and needed to hit all the major plot points before running out of film stock. Some characters have been whittled down to near non-existence (the Native American housekeeper, here played by Misty Upham, has been reduced to a virtual extra), while the participation of others has been severely curtailed so as not to distract from the main event of the Streep-Roberts smackdown.

About that smackdown. Judging by the posters for the film, which flaunt a scrunch-faced, teeth-baring Ms. Roberts wrestling a very harassed-looking Ms. Streep to the ground, the battle royal between two living legends already has been designated as the chief selling point for this film. I won’t argue the point. The tattered Baby Jane template still has some blood coursing through its skeletal remains, and I suspect it isn’t just camp-starved audiences who will pony up the cash to see the two biggest female stars of their respective generations going at each other like a pair of fabulously plumed Japanese fighting fish. Both actresses seem to have taken their cues from that WWE poster aesthetic, and while the ham they serve up may be to many people’s taste, the meal as a whole is less than nourishing.

At this point, we’re really not supposed to say anything bad about Meryl Streep, since certain things are to be accepted without questioning. Remember that thing they taught us in school about Democracy being the best form of government? Well, even if a few dozen Tea Party crackpots can force a complete shutdown of the entire federal shebang, you can’t fault the model, God dammit. Likewise, I’ve discovered that in certain quarters, if you broach any contradiction to the edict that Meryl Streep is The Greatest Actress Who Ever Was, people will react as if you said something bad about America. I’ve spoken this blasphemy before, and I’ve been unfriended on Facebook for doing it. I’m not exactly sure why certain folks seem to have so little sense of proportion when it comes to Our Lady of the Accents, but this is not to imply that their insistence upon her genius is entirely lacking in merit. Ms. Streep is unquestionably great. She has given some of the best and most memorable performances of the last 30-odd years. That her talent level is through the roof, residing somewhere in the stratosphere, is beyond reproof. I suspect she’s abundantly aware of this.

It isn’t that Streep has become complacent as a performer; she doesn’t just coast on her abilities, though at times, she seems to be responding more to her characters as Great Acting Opportunities than as flesh-and-blood human beings. By default, she is undoubtedly the best thing in August: Osage County. Her performance is the most finely honed and easily the most convincing of the bunch, even if the favored mannerisms and inflections are starting to look so precise and polished that they might as well be kept under glass at Tiffany’s. Where the performance loses credibility (and probably, this is the director’s fault as much as hers) is in her rendering of Violet as a lip-smacking Diva turn. Part of the fun of watching Deanna Dunagan onstage was the slow reveal of Violet’s true nature; behind the drug-induced haze and tortured insecurities lie an ineffably shrewd, twisted, Machiavellian mind, sharp as a tack and ready to do battle. By contrast, Streep takes to the screen like she’s warming up to play Eleanor of Aquitaine. When it’s crystal clear from the outset exactly who’s pulling the strings, a vital element of suspense is lost. Frankly, given who’s she up against, it isn’t as though she has much in the way of competition, anyway.

Lest anyone misunderstand my intentions, I must duly assert that I am not a snob when it comes to acting pedigree. Range and/or skill set, whether acquired by classical or method training, does not necessarily place one person on a higher pedestal than anyone else. Talent is talent, and I’ve always had a soft spot for performers who can make assembly-line crap compulsively watchable by sheer force of personality. Julia Roberts has her limitations as an actor, and her fair share of detractors (and boy, are they emphatic), but she’s also given some of the great movie star performances of her era. It’s not a knock on Audrey Hepburn to say that she probably didn’t have the chops for Albee, or that Barbra Streisand might have been absolutely disastrous in Pinter. Nor should it be perceived as a negative reflection on Ms. Roberts to say that what is required of her in this context is simply beyond her abilities. Unfortunately, that negative balance takes a lot of the charge out of the material, and gives the mother-daughter skirmish the appearance of a lopsided battle.

On stage, Amy Morton’s cornhusk-dry delivery, powerful physicality and searing emotional transparency went a long way towards revealing the deep reserves of anger and pain which informed Barbara’s metamorphosis from defeated, resentful onlooker to fully engaged combatant. While Barbara is nominally the protagonist, she’s not really the hero. That she is very much her mother’s daughter, as damaged and damaging as Violet and with the same capacity for unleashing icy torrents of cold, hard fury, is made abundantly clear as soon as Mama starts turning up the heat. You have to believe, as one character asserts, that in spite of surface appearances, there’s “no difference” between the two. Roberts endeavors diligently to embody the complexities and contradictions of the role, but going to the dark places is not the most comfortable place to be when one has made a career out of flooding the screen with sunshine. She overcompensates by punching up her sassy, feisty Erin Brockovich shtick, but what worked like gangbusters in a miniskirt and push-up-bra does not here dimension make. It’s an uncharacteristically flat, colorless performance. There’s never any risk of Barbara turning into her mother, not does it ever seems as though she is willing or able to take Violet to the mats.

No one else meandering through the din makes much of an impression, although a few of the performers — notably Chris Cooper, Margo Martindale and Juliette Lewis, who brings some nice flashes of hysteria to her marginalized role as the most clueless and least functional of the three sisters — are at least better suited to the material. While Benedict Cumberbatch has carved out a nice niche for himself in recent years as the thinking girl’s sex symbol, and Ewan McGregor likely will remain boyishly handsome well into his 60s, their presence here as, respectively, a sad-sack, slow-witted underachiever and an unprepossessing middle-age college professor, defies all measure of reason. Julianne Nicholson, Dermot Mulroney and Abigail Breslin are among those also caught in the cross-hairs, although everyone not named Meryl or Julia is essentially treated as window-dressing. While it’s something we’ve come to expect of the movies, casting so many extremely photogenic performers was probably a mistake. Quiet desperation, romantic neglect and midlife crisis have never looked more red-carpet-ready.

That red carpet will doubtless unfurl in the months to come for at least one member, and possibly more, of August: Osage County’s creative team. Tracy Letts may reap some of the rewards for his contribution here. Of course, nominations are nice, and so is the money…but reading between the lines of the playwright’s recent comments to The New York Times, he’s not entirely satisfied with the finished product. A writer’s life is one of compromise when the camera comes into the picture, and based on Letts’ statements, he probably realized that trying to maintain too much control over the film version would have been fighting a losing battle. At least, by doing the adaptation himself, he could still score a few points and protect some of what needed to be preserved. Why do we hurt the ones we love? If August: Osage County is any indication, the answer may be to prevent others from hurting them instead.

Tweet

Labels: 10s, A. Hepburn, Albee, Chris Cooper, Ewan McGregor, Harold Pinter, Julia Roberts, O'Neill, Shepard, Streep, Streisand, Theater

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Monday, December 09, 2013

Treme No. 33: This City

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This recap contains spoilers, so if you haven't seen the episode yet, move along.By Edward Copeland

Albert (Clarke Peters) seems unusually upbeat, pacing about his doctor's office, glancing out his window and commenting upon the unusually warm December day. He even tells Dr. Powell (Cordell Moore) that he feels as if he's overflowing with energy, but the doctor insists Lambreaux sit down. He describes Albert's mood as the "Indian Summer" effect and reports that the latest scans indicate that his cancer has spread to his liver. Albert shuffles out to the lobby where Davina (Edwina Findley) waits for him. She senses that her father didn't get good news, but Albert stays silent and gives his daughter a pat and a grin as the leave the building. (The credits give the first onscreen indication of the final season's cost-cutting measures as India Ennenga who plays Sofia and Michiel Huisman who portrays Sonny don't have their names present in the credits since they don't appear in this episode.)

Antoine (Wendell Pierce) to find all the students gathered in a circle and chattering. Robert (Jaron Williams) informs him that Cherise's boyfriend was shot and the teen girl (Camryn Jackson) was with him at the time. Batiste asks if her boyfriend had been involved in anything bad, but Jennifer (Jazz Henry) tells him that Cherise said no. Cherise isn't in class, hiding at home and frightened. Antoine urges the class to take their seats.

After the trip to the doctor's, Albert makes Davina drive him to some of his old haunts from growing up, beginning with the Seventh Ward, though he tells his daughter that no one called it that. "Some called it Creoleville…There were whites here, blacks too. Folks with Choctaw Indian in 'em, French blood too. High yellows," he tells her. Davina asks if this preceded segregation and he answers in the affirmative, explaining it really got bad in the 1960s when a white friend sat with them at the back of the bus and set off the driver who threw them all off. In the middle of Albert's tour, the show interrupts the flow with Toni (Melissa Leo) arriving at the home of the Gildays, the parents of

the man who died in the Orleans Parish jail. A short scene of Toni at the door before returning to Albert and Davina. We do return to the Gilday home where Toni convinces Mr. and Mrs. Gilday (John Joly, Julie Ann Doan) to let her launch a wrongful death inquiry, including bringing in an outside coroner for an outside coroner. "We can't rely on the coroner's office, not in Orleans Parish," Toni tells the Gildays. This episode, "This City" (written by George Pelecanos, directed by Anthony Hemingway), repeats the exact bizarre cutting technique in the sequence that follows. We see Antoine knocking on Cherise's door, but — instead of just going in and seeing the scene where he talks to the girl and warns her to be aware of her surroundings — we cut to the shortest of scenes where Janette (Kim Dickens) and Jacques (Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine) shop for produce at a cart and Janette gets served a cease-and-desist order from Tim Feeny, ordering her not to use Desautel's in the name of her new restaurant. (Granted, drive time might have been needed to account for the different sites Albert points out to Davina, but it's pointless to show both Toni and then Antoine at separate doors and then play the short scenes in the entirety later. The Janette scene really sticks out. She could have been served anywhere, anytime. In fact, the scene isn't even necessary. The information gets conveyed completely in a scene at the restaurant with Davis later. These quick, separated scenes occur a lot in this outing but I'm ignoring them here on out in this no-frills recap. Thankfully, of the final five episodes, "This City" happens to be the only one reminiscent of the worst of Season Two.)

the man who died in the Orleans Parish jail. A short scene of Toni at the door before returning to Albert and Davina. We do return to the Gilday home where Toni convinces Mr. and Mrs. Gilday (John Joly, Julie Ann Doan) to let her launch a wrongful death inquiry, including bringing in an outside coroner for an outside coroner. "We can't rely on the coroner's office, not in Orleans Parish," Toni tells the Gildays. This episode, "This City" (written by George Pelecanos, directed by Anthony Hemingway), repeats the exact bizarre cutting technique in the sequence that follows. We see Antoine knocking on Cherise's door, but — instead of just going in and seeing the scene where he talks to the girl and warns her to be aware of her surroundings — we cut to the shortest of scenes where Janette (Kim Dickens) and Jacques (Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine) shop for produce at a cart and Janette gets served a cease-and-desist order from Tim Feeny, ordering her not to use Desautel's in the name of her new restaurant. (Granted, drive time might have been needed to account for the different sites Albert points out to Davina, but it's pointless to show both Toni and then Antoine at separate doors and then play the short scenes in the entirety later. The Janette scene really sticks out. She could have been served anywhere, anytime. In fact, the scene isn't even necessary. The information gets conveyed completely in a scene at the restaurant with Davis later. These quick, separated scenes occur a lot in this outing but I'm ignoring them here on out in this no-frills recap. Thankfully, of the final five episodes, "This City" happens to be the only one reminiscent of the worst of Season Two.)Delmond (Rob Brown) travels to New York and records with Terence Blanchard, who offers the younger Lambreaux more upcoming work on his tour for the album, but Del hedges, given the latest news on Albert's health and his impending fatherhood.

Annie (Lucia Micarelli) attends the Best of the Beat Awards held at the House of Blues on Decatur Street and wins best song. Marvin (Michael Cerveris) congratulates her, but Annie brushes it off as being fortunate while Frey tells her hard work earned her that honor. He also brings up the subject of dumping Bayou Cadillac for his Nashville musicians, insisting that Annie's band will understand. "I'm gonna make this record my way. That's why you hired me," Frey declares when Annie resists firing the musicians before taking the stage to perform "This City" in memory of Harley.

In that scene I referred to, Janette informs Davis (Steve Zahn) of Feeny's legal move and the two (mostly McAlary) unleash new, creative vulgar phrases for the businessman. They also discuss the costs with removing Janette's last name from the restaurant's sign, its menu and even her chef's uniform. Janette makes Davis smile though when she informs him that she's going home with him that night.

When Del returns to New Orleans, he finds his sister quite upset. Albert won't take any more chemotherapy, intent instead on concentrating on his outfit for Mardi Gras and the impending birth of his grandchild, which he insists will be a boy. Davina can't understand why Del isn't more upset, but he tells her that the doctor told them further

chemo might not help much and they should honor Albert's wishes. "We should start preparing for what's inevitable," Delmond says as he takes his sobbing sister in his arms. Antoine stops by GiGi's to give her some child support for Randall and Alcide, but asks LaDonna (Khandi Alexander) why she still gives him that suspicious look now that he holds a regular job. "I've had a habit of doubting you for a long time. Maybe too long," LaDonna admits. As they talk about overcharges for the wiring, a tune playing by Gary Walker and the Boogie Kings and how Larry has carried the load for far too long when it comes to caring for the boys, LaDonna confesses to Antoine, "I like you better now than when we were married." Antoine smiles. "I had a growth spurt, I guess," he responds as the two do a little dance to the "Who Needs You So Bad?" with the bar separating them. During another meeting with LaFouchette (James DuMont) about the high amount of deaths in the Orleans Parish jail, Officer Billy Wilson (Lucky Johnson) stops by to taunt Toni (Melissa Leo) over her inability to nail him in the death of Joey Abreu.

chemo might not help much and they should honor Albert's wishes. "We should start preparing for what's inevitable," Delmond says as he takes his sobbing sister in his arms. Antoine stops by GiGi's to give her some child support for Randall and Alcide, but asks LaDonna (Khandi Alexander) why she still gives him that suspicious look now that he holds a regular job. "I've had a habit of doubting you for a long time. Maybe too long," LaDonna admits. As they talk about overcharges for the wiring, a tune playing by Gary Walker and the Boogie Kings and how Larry has carried the load for far too long when it comes to caring for the boys, LaDonna confesses to Antoine, "I like you better now than when we were married." Antoine smiles. "I had a growth spurt, I guess," he responds as the two do a little dance to the "Who Needs You So Bad?" with the bar separating them. During another meeting with LaFouchette (James DuMont) about the high amount of deaths in the Orleans Parish jail, Officer Billy Wilson (Lucky Johnson) stops by to taunt Toni (Melissa Leo) over her inability to nail him in the death of Joey Abreu.

(One thing I love is when series with disparate casts — or castes — create situations where these characters interact. My So-Called Life and Freaks and Geeks stand as just two examples of shows that do this well as does Treme, which creates one of the best in the scene that follows.) Nelson (Jon Seda) takes C.J. (Dan Ziskie) to lunch to meet Davis, proposing he might make a good liaison for them between the local music scene and the jazz center project, though he admits he's rough around the ages. McAlary does his best to be on his best behavior, citing his record label, disc jockey job and musical heritage tour as qualifications. He warns Liguori that he speaks his mind, but C.J. tells him he would expect nothing less. The banker then recalls McAlary's quixotic political campaign (in Season 1) when Davis planned to renamed the New Orleans Hornets the New Orleans Mormon Tabernacle Choir to shame Utah into returning the name Jazz back to the team. Davis also reminds him of his plan of Pot for Pot Holes. Unfortunately, Davis remembers who C.J. Liguori is as well — the banker who is one of the biggest GOP fund-raisers in the state and was involved in the Greendot program. Davis admits to boycotting his bank for 10 years. "I was wondering where that three hundred dollars went," C.J. comments drily while continuing to eat.

Hey Twin Peaks fans, a club exists in New Orleans called One Eyed Jacks and Annie goes there to see Lucero perform (in front of red curtains no less) before hooking up with her occasional boyfriend, its lead singer, Ben Nichols.

Nelson finds Janette's new place, where Davis happens to be, and remarks how much better her food is than what's being served at her old place. She fills him in on the Feeny details and how she's going to try to appeal to his humanity to use her name. McAlary asks Hidalgo how he thinks his chances for being a community liaison for C.J went, but Nelson admits that he thinks Liguori plans to go another way. Davis gulps when realizing he lost a $30,000 job.

Murder never stops in New Orleans and when Colson (David Morse) arrives at another crime scene to discover his men fiddling about he also learns the victim is Cherise.

Toni tries to get FBI Special Agent Collington (Colin Walker) interested in the Orleans Parish in-custody deaths, but he admits to a full plate. Toni can't contain her anger since no movement has happened on the Abreu case she gave them. "Sphinx move faster than you fucking feds," she spits.

No humanity can be found in Tim Feeny (Sam Robards) who tells Janette that he plans to sue over a Times-Picayune article where she extolled fine cuisine over chain-style dining. She can forget about getting her name back as well. He even lets her pick up the tab.

"That sweet girl," Antoine says when Colson and Detective Nikolich (Yul Vazquez) question him about his meeting with Cherise two days prior. It turns out her boyfriend had been wearing one of his older brother's shirts and was killed by thugs he had a beef with from the Iberville projects. Nikolich offers the visibly shaken and upset Antoine that if it's any comfort, they've identified the killers and just have to locate them to arrest them for the crimes. "No sir, that's no comfort at all," Antoine responds. (Pierce brings to the table whatever is needed, even if that mostly ends up being Antoine's more comical side, but when he shows us Batiste's other layers, especially in this dramatic scene of devastation, he's even more of a wonder to behold. While so many members of this talented ensemble deserve award recognition, this scene reminds me that Pierce might be the most glaring Emmy oversight in addition to the series itself. Perhaps next year a going-away present.) LaDonna cooks Albert a dinner at his house as the share a dinner date alone. Later, the talk turns to mortality as Albert reminisces about many of his old friends, all gone, and even his late wife, who he admits LaDonna reminds him of in many ways. "When you get right down to it, death is an ordinary thing," Lambreaux admits while lying on his sofa, his head resting in LaDonna's lap.

Terry returns to Toni's house to find her doing the dishes. He tries to ask about her day, but she brushes it off, though he tells her about Cherise's murder and tells her they know the killer, but just have to find her. Toni erupts, asking if they'll lose the evidence and screw it up. She finally admits being shaken up by Officer Wilson's taunt and the snail-like crawl of the feds to take any action on the Abreu murder among other cases she gave them. She brings up the Orleans Parish in-custody deaths, but Colson trying to keep the situation calm says precisely the wrong thing by explaining that's the sheriff's department and not under his department's supervision. She blows up and storms up. (After all these years, even when Toni felt scared enough to send Sofia away when the NOPD harassed them, she still maintained her optimistic faith in justice winning out. Toni appears broken. (In the 33 episodes of Treme so far, Melissa Leo always has proved spectacular, but in this brief scene, seeing that tireless champion Toni Bernette break down and admits she feels the system is rigged beyond repair, Leo delivers another amazing piece of work. Morse, who stands calmly and lets her vent without trying to quell her fears or say she's wrong, performs at her level as the sounding board who knows to stay out of her way. One other note: The school Antoine teaches at, Theophile Jones Elie, was called an elementary school when introduced in the second season. The school still bears that name, but I wondered about how the school systems break down in New Orleans, since it seemed odd that 14- and 15-year-olds still would attend an elementary, but Colson describes Cherise as a middle school student. Still unclear, but who knows?)

Larry (Lance E. Nichols) carries a below-freezing demeanor when LaDonna shows up to give him Antoine's money for the boys. He balks when she suggests taking Randall and Alcide with her. Larry asks if she means to the Residence Inn or the room above the bar. They're best with him and unless she wants to talk about coming home. LaDonna asks him to tell the boys she was there and leaves.

That night, outside Theophile Jones Elie, a candlelight vigil takes place for Cherise and all the other young people slain on the streets of New Orleans. Young Jennifer even speaks on behalf of Cherise and all the other young people. "We love this city, but it hasn't loved us back," the teen tells the crowd.

BLOGGER'S NOTE: I almost got this no-frills update up last night, but my stamina and fingers failed me. Health circumstances this week make a recap of this season's third episode unlikely, but I'll try to return for the fourth episode and the finale.

Tweet

Labels: Clarke Peters, D. Morse, HBO, Kim Dickens, M. Cerveris, Melissa Leo, Treme, TV Recap, Twin Peaks, Wendell Pierce, Zahn

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Sunday, December 01, 2013

Treme No. 32: Yes We Can Can, Part I

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This recap contains spoilers, so if you haven't seen the episode yet, move along. Unfortunately, another hospitalization put the final nail in me finishing this first recap on time and places the remaining recaps in doubt and jeopardy.By Edward Copeland

As we return to our friends in New Orleans more than a year after we last looked in our their lives, it happens to be Election Day 2008, and we see the familiar trappings of any campaign — signs stacked on top of one another, long lines of citizens eager to perform their civic duty, poll workers taking their seats, ballot boxes being unlocked and set up and, finally, the actual process of voting taking place. During this montage, we catch our first sightings of

characters we know. Desiree (Phyllis Montana-Leblanc) watches news reports of the expectations of a historic day while Honoré plays at her mother’s feet. Toni and Sofia Bernette (Melissa Leo, India Ennenga) stand in line together, awaiting the college freshman’s first chance to vote in a presidential election. Playing throughout this section of the premiere’s opening, we hear “Every Man a King,” the campaign song used by Louisiana’s legendary Huey Long and currently being spun by DJ Davis McAlary (Steve Zahn) on WWOZ. As the tune ends, McAlary explains the station’s theme that day aims to play songs of political import. “The polls have indeed opened in our politically calcified and corrupt state and remember, if you want your vote to matter, the question is 'What are you doing here?' To paraphrase the great Lafcadio Hearn, better to vote once in Ohio in sackcloth and ashes than 10 times in every parish in Louisiana,” Davis tells his listeners, before switching to Allen Touissant’s own version of the song which gives this episode its title, “Yes We Can Can,” a song Touissant originally wrote as “Yes We Can” for Lee Dorsey in 1970, but which added the extra "Can" when it became a 1973 funk hit for The Pointer Sisters. (I swore I did try to avoid going overboard on the background, but I imagine I'll let up as outside forces close in on the time needed for even bare-bones recaps.)

characters we know. Desiree (Phyllis Montana-Leblanc) watches news reports of the expectations of a historic day while Honoré plays at her mother’s feet. Toni and Sofia Bernette (Melissa Leo, India Ennenga) stand in line together, awaiting the college freshman’s first chance to vote in a presidential election. Playing throughout this section of the premiere’s opening, we hear “Every Man a King,” the campaign song used by Louisiana’s legendary Huey Long and currently being spun by DJ Davis McAlary (Steve Zahn) on WWOZ. As the tune ends, McAlary explains the station’s theme that day aims to play songs of political import. “The polls have indeed opened in our politically calcified and corrupt state and remember, if you want your vote to matter, the question is 'What are you doing here?' To paraphrase the great Lafcadio Hearn, better to vote once in Ohio in sackcloth and ashes than 10 times in every parish in Louisiana,” Davis tells his listeners, before switching to Allen Touissant’s own version of the song which gives this episode its title, “Yes We Can Can,” a song Touissant originally wrote as “Yes We Can” for Lee Dorsey in 1970, but which added the extra "Can" when it became a 1973 funk hit for The Pointer Sisters. (I swore I did try to avoid going overboard on the background, but I imagine I'll let up as outside forces close in on the time needed for even bare-bones recaps.) As Toussaint’s “Yes We Can Can” glides us from WWOZ to the Lambreaux residence, Albert (Clarke Peters) sews in his driveway, mystifying his children Delmond and Davina (Rob Brown, Edwina Findley) that he lacks interest in joining their trip to the polls. Del emphasizes that the chance to vote for a black man for president might not come again soon, but his father stoically replies, “You really think that’s going to change some shit?” Though the last time we saw the big chief, chemo had left him bald. Now, his hair has returned and he’s regrown his mustache. After voting, Antoine Batiste (Wendell Pierce) and Desiree come upon a musical garden party of sorts, where John Boutté sings Sam Cooke’s classic “A Change Is Gonna Come.” Sonny (Michiel Huisman) drops Linh and her father Tran (Hong Chau, Lee Nguyen) off to vote, but Tran questions why he isn’t coming in order to tell his wife how to vote. Sonny

explains he isn’t a citizen, so Tran says he’ll tell Linh what to do this time. Tran plans to vote for McCain. “Democrats in Vietnam — they quit, give up. Republicans for me, always,” Tran says. Sonny shrugs to his wife and asks, “McCain?” Linh just grins and replies, “Father knows best.” When Antoine asks James Andrews who’s paying him for the gig with Boutté, he tells Batiste that all the gathered musicians are working for free. Antoine decides to go home and retrieve his bone. While Albert expressed disinterest to his children, he sits on his couch and watches the television reports of the long lines that began early on this Election Day. Once Antoine has joined Boutté and the other musicians, they burst forth with “Glory Glory Hallelujah.” When no one watches, Albert himself turns up at a polling station. As the day turns into night, the celebratory atmosphere intensifies as Toni and Sofia join an Obama rally outside Kermit Ruffins’ Sidney’s Saloon, also attended by Antoine and Desiree and presided over by Ruffins himself, where all watch Barack Obama’s acceptance speech from Chicago. “That’s your president, baby,” Antoine tells Honoré. “He looks just like you.” Back at home, Albert again watches alone, still with an uncertain sadness about him. Ruffins blows his trumpet and makes his ways through the crowd shouting, “Yes we can” repeatedly until he gets to the middle of St. Bernard Avenue alone, clear of the crowd, and sees the flashing lights of police cars in the distance. Some things remain the same. The entire opening sequence of the premiere (written by David Simon & Eric Overmyer & George Pelecanos, directed by Anthony Hemingway) runs for nearly seven minutes. It’s a beautiful sight to behold and a great beginning to our final hours with our friends in Treme.

explains he isn’t a citizen, so Tran says he’ll tell Linh what to do this time. Tran plans to vote for McCain. “Democrats in Vietnam — they quit, give up. Republicans for me, always,” Tran says. Sonny shrugs to his wife and asks, “McCain?” Linh just grins and replies, “Father knows best.” When Antoine asks James Andrews who’s paying him for the gig with Boutté, he tells Batiste that all the gathered musicians are working for free. Antoine decides to go home and retrieve his bone. While Albert expressed disinterest to his children, he sits on his couch and watches the television reports of the long lines that began early on this Election Day. Once Antoine has joined Boutté and the other musicians, they burst forth with “Glory Glory Hallelujah.” When no one watches, Albert himself turns up at a polling station. As the day turns into night, the celebratory atmosphere intensifies as Toni and Sofia join an Obama rally outside Kermit Ruffins’ Sidney’s Saloon, also attended by Antoine and Desiree and presided over by Ruffins himself, where all watch Barack Obama’s acceptance speech from Chicago. “That’s your president, baby,” Antoine tells Honoré. “He looks just like you.” Back at home, Albert again watches alone, still with an uncertain sadness about him. Ruffins blows his trumpet and makes his ways through the crowd shouting, “Yes we can” repeatedly until he gets to the middle of St. Bernard Avenue alone, clear of the crowd, and sees the flashing lights of police cars in the distance. Some things remain the same. The entire opening sequence of the premiere (written by David Simon & Eric Overmyer & George Pelecanos, directed by Anthony Hemingway) runs for nearly seven minutes. It’s a beautiful sight to behold and a great beginning to our final hours with our friends in Treme.Following the credit sequence, we slowly pan from a group of chickens gathered behind the back of a small gray station wagon until we see the vehicle’s door ajar while two roosters near the door seem to be attempting to converse with Davis on his knees in front of his mode of transportation, taken out by a very large pothole. McAlary, in a moment that could be lifted from a Werner Herzog film, unemotionally says, “Fuck you” to the fowl as if they mocked his misfortune.(In the early years of Treme, I felt Zahn received undue criticism for his portrayal of Davis McAlary, many seeing him as little more than a caricature, but I’ve never thought that to be the case. Perhaps part of my defense stems from being an early fan of Zahn’s work both on stage and in films, but the Davis detractors give neither the character nor the actor who inhabits him the credit each deserves or recognize McAlary’s many layers of emotional depth and serious intent when it comes to the musical heritage of New Orleans. Davis McAlary as a whole exists neither as a cartoon nor a buffoon. Now that I recall, Herzog directed Zahn in Rescue Dawn, the feature version of Herzog’s documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly.) Meanwhile, it appears that last season’s tensions between Tim Feeny (Sam Robards) and Janette Desautel (Kim Dickens) reached a boiling point and Janette no longer works at the restaurant which continues to operate using her name, Desautel’s on the Avenue. Not one to give up, Janette currently paints her own sign for a new restaurant she’s about to open on Dauphine Street at Louisa Street in the Bywater area of New Orleans. Only selecting a name for her new eatery stumps Janette. Her sous chef (and lover when last we saw them) Jacques Jhoni (Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine) suggests she call it Desautel’s, the only word she’s completed on the sign, but Janette nixes that since it was the name of her first restaurant. She floats the idea of Desautel’s on the Bywater, but Jacques says it summons the image of byproducts and might not be an appetizing image. For now, Janette remains stuck, but Davis’ vehicle does not as a tow truck comes to its rescue, if not McAlary’s. Once the station wagon leaves the scene, the viewer truly realizes what a monster the pothole that ensnared its front wheel is. It must be at least three feet wide, if not more, and who knows how deep, judging by the pooled water flooding to its surface. Davis yells in vain as the tow truck driver vanishes down the road about what should be done about the gaping hole. With no response forthcoming, McAlary surveys the surroundings. We leave New Orleans for a moment to check in on Nelson Hidalgo (Jon Seda), back home in Texas, Galveston to be precise, with his cousin Arnie (Jeffrey Carisalez) in tow, looking for new projects in the wake of Hurricane Ike. Hidalgo also busies himself cursing at not getting through to one of his brokers, telling Arnie that the elusive man has “Five mil of mine under this guy’s ass and I can’t get him on the phone like he’s just some discount broker? What the fuck is that?” Nelson meets with two businessmen, Jimmy Staunton and Doug McCreary (Patrick Kirton, John Niesler), about getting involved in the demolition game in Texas. McCreary asks how big a slice Hidalgo might like and Nelson tells him he already has 15 crews ready to work and can get more if needed. “You didn’t like New Orleans much?” McCreary inquires. “Work was good, but I’m home now and damn glad to be back in the Lone Star State, believe you me,” Nelson replies. Staunton declares that if Nelson is tight with Bobby (a reference to a character named Bobby Don Baxter, a Texas demolition baron that Nelson enlisted to help tear down the Lafitte Projects in Season 3), he’s tight with Staunton. However, in order to get the contracts, Nelson must use the Houston bank that McCreary happens to own. Back in the Crescent City, it first appears as if Davis plans to repair the pothole himself as he wheels a shopping cart out to it filled with buckets and what appear to be supplies. Instead, he uses the cart, buckets and various other tools to create an almost modern art sculpture tall enough to warn motorists and to cover the road hazard. “My work here is done,” Davis proclaims as he walks away. (This section of the episode — and you could include the Galveston scene I’m about to recap as part of it as well — cuts from one short scene to the next in ways that often proved disruptive in many Season 2 episodes but, as in Season 3, they’ve fixed that flow problem so it doesn’t feel as if the viewer constantly hits a road bump for no good reason. They don’t have an underlying connection as the magnificent collection of short scenes in this episode’s pre-credit sequence does, but that segment had Election Day to serve as the cake for which those disconnected moments could be frosted into confectionery perfection, giving us one of the greatest openings of a Treme episode ever in the first of its final five. However, even when they don’t feel superfluous, because of health difficulties and other interruptions that barely allowed me to post this first recap on time and put the timeliness of the remaining four in question, I will be leaving many scenes I deem of lesser importance out of these pieces entirely.)

Back in Galveston, Nelson's broker finally returns his call and gets an earful from Hidalgo as to why he hasn't sold his stocks yet. "We are shedding like a thousand points on the Dow in the two days since the election. I can't take anymore," a more subdued Nelson tells his broker on the other end of the line before erupting again, "Get me out of this fuckin' market now!" As Nelson pockets his phone, he joins Arnie at a food stand selling Tex-Mex cuisine where Arnie and Nelson's lunch orders wait on the counter. "What do you think happened?" Arnie asks. "It's Obama, I guess," the erstwhile Republican Hidalgo speculates. "Wall Street doesn't like the guy or something, but this shit started two months ago when they let Lehman Brothers go under," Nelson declares, pointing at his cousin for emphasis. Arnie asks how much of a hit Nelson has taken so far from the economic collapse. "Between yesterday and today, what I lost about two months ago — about a million four and climbing," Hidalgo replies. "Don't worry. These are on me," Arnie reassures his cousin about paying for lunch. A somewhat clumsy instrumental version of the children’s gospel classic “This Little Light of Mine” (composed by Harry Dixon Loes around 1920 and recorded in numerous styles and genres with its lyrics.) plays us out of Galveston and into the Theophile Jones Elie band room. Antoine circles the young teens before urging his budding musicians to stop,

telling them that the notes emanating from their instruments are "cacophonous — from the Greek word caca." Antoine asks the kids why they aren't coming prepared as they'd discussed and one replies that they are trying. "Not hard enough," Mr. Batiste tells his class. One of the students, Markell (Markell Henderson), admits to missing the former lead instructor, Mr. LeCoeur, who left for a post at a New Orleans high school. Antoine tells the band that LeCoeur isn't coming back and the students have him as their instructor year-round now. As Batiste lectures the kids about coming to class "correct," Cherise (Camryn Jackson) disassembles her saxophone, places it in its case and prepares to leave. Antoine inquires about her destination and Cherise tells him that she has to pick up her little brother, though Jennifer (Jazz Henry) teases that Cherise plans to hook up with her boyfriend. The bell rings for the day, so most everyone exits anyway. Antoine shakes his head and mutters to himself about someone as young as Cherise already having a boyfriend. Then he notices Robert (Jaron Williams) still sitting in his desk, staring down and shaking. Antoine asks Robert what's wrong because he knows it couldn't have been him playing that horn. "It hurts, Mister Batiste," Robert replies, indicating his groin area as his trumpet bounces up and down off his jittery legs. Antoine asks the boy if he's been "pulling on it" and his student offers the additional information that "it burns when I pee. It's sticky down there." Pierce delivers a great empathetic cringe once he realizes what afflicts one of his best students. Antoine inquires as to whether Robert has had sex and the prodigy once nick-named Bear tells of one girl in his neighborhood and "she's been bothering me." Antoine sighs, "They all do." He learns, to no great surprise, that Robert lacks both a family doctor or any kind of health insurance. "Gather your things, boy — your horn, too," Batiste tells his student as he puts his coat and cap on, a grin of wistful STD-related nostalgia crossing his face. (As has been the case throughout Treme’s run, Pierce’s portrayal of Antoine remains the series’ heart and soul. Pierce finds new ways to make Antoine funny and serious, often simultaneously, and reveals new sides to Batiste each season. The show manages to give most members of its ensemble cast moments to shine, but I can’t remember a wasted moment involving Pierce.)

telling them that the notes emanating from their instruments are "cacophonous — from the Greek word caca." Antoine asks the kids why they aren't coming prepared as they'd discussed and one replies that they are trying. "Not hard enough," Mr. Batiste tells his class. One of the students, Markell (Markell Henderson), admits to missing the former lead instructor, Mr. LeCoeur, who left for a post at a New Orleans high school. Antoine tells the band that LeCoeur isn't coming back and the students have him as their instructor year-round now. As Batiste lectures the kids about coming to class "correct," Cherise (Camryn Jackson) disassembles her saxophone, places it in its case and prepares to leave. Antoine inquires about her destination and Cherise tells him that she has to pick up her little brother, though Jennifer (Jazz Henry) teases that Cherise plans to hook up with her boyfriend. The bell rings for the day, so most everyone exits anyway. Antoine shakes his head and mutters to himself about someone as young as Cherise already having a boyfriend. Then he notices Robert (Jaron Williams) still sitting in his desk, staring down and shaking. Antoine asks Robert what's wrong because he knows it couldn't have been him playing that horn. "It hurts, Mister Batiste," Robert replies, indicating his groin area as his trumpet bounces up and down off his jittery legs. Antoine asks the boy if he's been "pulling on it" and his student offers the additional information that "it burns when I pee. It's sticky down there." Pierce delivers a great empathetic cringe once he realizes what afflicts one of his best students. Antoine inquires as to whether Robert has had sex and the prodigy once nick-named Bear tells of one girl in his neighborhood and "she's been bothering me." Antoine sighs, "They all do." He learns, to no great surprise, that Robert lacks both a family doctor or any kind of health insurance. "Gather your things, boy — your horn, too," Batiste tells his student as he puts his coat and cap on, a grin of wistful STD-related nostalgia crossing his face. (As has been the case throughout Treme’s run, Pierce’s portrayal of Antoine remains the series’ heart and soul. Pierce finds new ways to make Antoine funny and serious, often simultaneously, and reveals new sides to Batiste each season. The show manages to give most members of its ensemble cast moments to shine, but I can’t remember a wasted moment involving Pierce.)We’ve already witnessed changes in several characters’ lives: Janette working on another new restaurant; Nelson feeling the financial impact of the 2008 Wall Street collapse and Antoine becoming the year-round, lead instructor for young band students. The biggest upheaval though may have happened in the life of LaDonna Batiste-Williams (Khandi Alexander). LaDonna and Larry have separated and LaDonna visits with Alcide and Randall (Renwick Scott, Sean-Michael Bruno), her sons by Antoine, on the porch of Larry’s Mid-City home. She asks if the teens if their stepdad treats them well and they tell their mom that Larry even has improved as a cook, though they have breakfast for dinner a lot. “Larry’s a good man and he loves you two like you’re his own,” LaDonna tells the boys, though the oldest, Alcide, immediately fires back with the question, “Then why did you leave?” LaDonna tries to explain to the adolescents that sometimes things

just don’t work out between people, but she promises the three of them will be together again soon — though she emphasizes that the reunion won’t occur in the house that holds the porch on which they currently sit. Alcide remains skeptical, having heard LaDonna’s promises before, but she insists that once she gets the bar up and running again that she’ll find a home for the three of them. “You finish the school year out here. It’s what’s best for you,” she tells her hardened oldest son. “Until things sort themselves out.” Alcide looks decidedly unconvinced and unmoved while Randall lets LaDonna cradle him in her arms on the porch swing. Antoine reunites unexpectedly with a former member of his Soul Apostles when he finds Sonny working part-time at The New Orleans Musicians’ Clinic that helps professional musicians who catch the sort of STDs that young Robert has. Sonny tells Antoine that he took this part-time job and does some gigs out of fear he’ll spend so much time on his father-in-law’s fishing boat that he’ll speak Vietnamese better than he does. Unfortunately, the clinic can’t help Robert since he not only isn’t a professional musician, but hasn’t reached the age of 15 yet, though Sonny says The Daughters of Charity at Ochsner will help him. “Fourteen and already burned, huh?” Sonny comments. “Yep. The kid’s a prodigy in more ways than one,” Antoine adds before sharing the hardest aspect about being a New Orleans musician to Sonny: “Having to explain to your girlfriend why she has to take penicillin for your kidney infection. The former bandmates erupt in hearty laughter. Even young Robert grins, though that prompts Batiste to swat him and ask, “What you laughing at, boy?”

just don’t work out between people, but she promises the three of them will be together again soon — though she emphasizes that the reunion won’t occur in the house that holds the porch on which they currently sit. Alcide remains skeptical, having heard LaDonna’s promises before, but she insists that once she gets the bar up and running again that she’ll find a home for the three of them. “You finish the school year out here. It’s what’s best for you,” she tells her hardened oldest son. “Until things sort themselves out.” Alcide looks decidedly unconvinced and unmoved while Randall lets LaDonna cradle him in her arms on the porch swing. Antoine reunites unexpectedly with a former member of his Soul Apostles when he finds Sonny working part-time at The New Orleans Musicians’ Clinic that helps professional musicians who catch the sort of STDs that young Robert has. Sonny tells Antoine that he took this part-time job and does some gigs out of fear he’ll spend so much time on his father-in-law’s fishing boat that he’ll speak Vietnamese better than he does. Unfortunately, the clinic can’t help Robert since he not only isn’t a professional musician, but hasn’t reached the age of 15 yet, though Sonny says The Daughters of Charity at Ochsner will help him. “Fourteen and already burned, huh?” Sonny comments. “Yep. The kid’s a prodigy in more ways than one,” Antoine adds before sharing the hardest aspect about being a New Orleans musician to Sonny: “Having to explain to your girlfriend why she has to take penicillin for your kidney infection. The former bandmates erupt in hearty laughter. Even young Robert grins, though that prompts Batiste to swat him and ask, “What you laughing at, boy?”Tweet

Labels: Clarke Peters, David Simon, HBO, Herzog, Kim Dickens, Melissa Leo, Overmyer, Treme, TV Recap, Wendell Pierce, Zahn

TO READ ON, CLICK HERE

Treme No. 32: Yes We Can Can Part II

BLOGGER'S NOTE: This recap contains spoilers, so if you haven't seen the episode yet, move along.By Edward Copeland

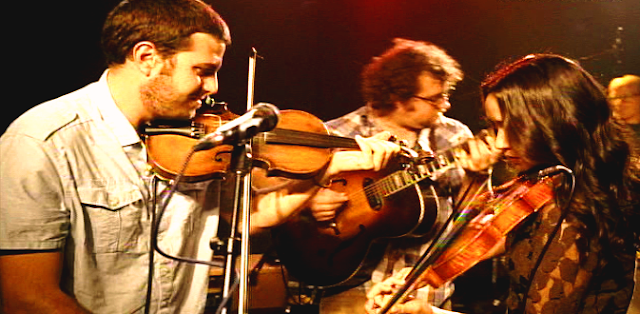

We finally see Annie (Lucia Micarelli) doing what she does best — playing the hell out of the fiddle with her band Bayou Cadillac on “Do You Wanna Dance” (with French lyrics, no less) on a Lafayette, Louisiana stage. When the set ends, Annie gets a big bear hug from Michael Doucet, founder of the band BeauSoleil, whose group had an album that bore the name Bayou Cadillac. He tells her he loves the name of the band and while Annie worries that he might take offense, Doucet assures her he takes it as a compliment. She tries to spread her exuberance to her manager Marvin Frey (Michael Cerveris), insisting it’s the best show ever and wishing they taped it or the concert in Mobile for a live album. “You might even sell a few copies in Lafayette or Mobile or even New Orleans,” Frey responds unenthusiastically. As Frey and Annie watch Doucet take the stage and Annie imagines being that big in a few years, Frey walks away. “Why do I get the sense that you are trying to tell me something?” Annie asks her manager. Frey tells her that in the music industry, it’s getting harder to survive on the margins. Her album did what it did but once they get north of a certain point geographically, it goes nowhere. “Doing rock ‘n’ roll dance hall tunes en francais in Lafayette?” Frey poses. “What the fuck Marvin? We’re in Lafayette,” Annie replies. “That’s right. You’re in Lafayette. I just thought you were hungrier than that,” Frey tells his client.

Terry (David Morse) looks quite comfortable reading the Times-Picayune sports section in Toni’s living room as he complains about the Atlanta Falcons who will face off against the hometown Saints with a 4-4 record. He fears he’s boring Toni with the football talk, but she surprises him with her pigskin player knowledge. Sofia breezes through the room, as she prepares to return east to school, and notes how comfy Colson seems in the house, asking if the living arrangement is permanent. Her mom informs Sofia that the city demolished Terry’s house. “I was too late getting started. Mold and rot had its way with everything,” Terry tells Sofia, who asks what she should call him now — Terry? Detective Colson? Colson suggests The Tall Guy. Colson inquires of Toni if she’d mind if he’d spend Thanksgiving with her and Sofia in New Orleans. He’d already asked his sons in Indianapolis and they approved, though Colson realizes he should’ve broached the subject with Toni first. Toni insists that both she and Sofia would love to have him there. (Morse has been so great in so many roles since his first splash on St. Elsewhere, that he truly was a welcome sight in his recurring role in the first season, even more so once he became a regular in Season Two) Annie seeks advice from ex-boyfriend Davis about Marvin’s advice that she dump Bayou Cadillac in favor of Nashville studio musicians. “I should tell him to go fuck himself, right? Isn’t that what I’m supposed to say?” Annie asks McAlary. While Davis agrees with her problems with Frey, he also admits that his relationship with the Lost Highway record label beats any local label, including his own. Annie thanks him for lending her his ear. “What else are psychically wounded ex-lovers for?” Davis replies before hopping on a bicycle and heading to his own label. He asks Don B. if his Aunt Mimi might be on the premises, but Don says between the two of them, most days he feels as if he’s holding down the fort by himself. He then gives Davis his paycheck, which McAlary complains will go to more than $800 in repairs for the pothole debacle. He also asks Don to admit that most days Bartholomew would pay to keep Davis out of the office. Before McAlary scampers off, Don gives him a demo of “the next big thing” that will come out of New Orleans, which turns out to be a new work by Trombone Shorty.

(Micarelli, the only regular cast member who came to the show with no acting experience, truly grew in her acting prowess over the course of these 36 episodes. Her musical abilities always were present. I wonder if she’ll return exclusively to the world of music or she’ll continue to pursue acting work. I hope she does.) Nelson returns to the Big Easy to check on his remaining investments there and to see if any opportunities remain that might help him rebuild his losses. He checks in with banker and business partner C.J. Liguori (Dan Ziskie) to see if he took a hit, but Liguori admits that most New Orleans businessmen always act more conservatively. In fact, he appears to be channeling the late, Creighton Bernette (John Goodman), despite the vast differences in Toni's late husband and C.J.'s political leanings, when he responds, "Hold the Corps accountable. Down here in New Orleans, we've lost our naiveté. We're several years past believing anything but spit, chewing gum and dumb luck keeps anyone high and dry." Liguori tells Hidalgo to relax and reminds him that most Mid-City properties should turn over soon and he holds pieces of that and that he wouldn't bet against the jazz center, the plans for which sit on Mayor Ray Nagin's desk. C.J. suggests Nelson get a good meal and a few drinks, but Hidalgo asks if there is anything immediate he could do for Liguori. C.J. informs him of a community meeting in the Treme about the jazz center that he could monitor for them since he'd be less likely to be recognized.

(Micarelli, the only regular cast member who came to the show with no acting experience, truly grew in her acting prowess over the course of these 36 episodes. Her musical abilities always were present. I wonder if she’ll return exclusively to the world of music or she’ll continue to pursue acting work. I hope she does.) Nelson returns to the Big Easy to check on his remaining investments there and to see if any opportunities remain that might help him rebuild his losses. He checks in with banker and business partner C.J. Liguori (Dan Ziskie) to see if he took a hit, but Liguori admits that most New Orleans businessmen always act more conservatively. In fact, he appears to be channeling the late, Creighton Bernette (John Goodman), despite the vast differences in Toni's late husband and C.J.'s political leanings, when he responds, "Hold the Corps accountable. Down here in New Orleans, we've lost our naiveté. We're several years past believing anything but spit, chewing gum and dumb luck keeps anyone high and dry." Liguori tells Hidalgo to relax and reminds him that most Mid-City properties should turn over soon and he holds pieces of that and that he wouldn't bet against the jazz center, the plans for which sit on Mayor Ray Nagin's desk. C.J. suggests Nelson get a good meal and a few drinks, but Hidalgo asks if there is anything immediate he could do for Liguori. C.J. informs him of a community meeting in the Treme about the jazz center that he could monitor for them since he'd be less likely to be recognized.Colson arrives at a crime scene where a man lies shot dead in his front yard. He summons one of his detectives, Cappell (Dexter Tillis), to discern what they know. He isn’t happy to learn that neither the young detective nor the

silent Detective Silby (JD Evermore), seen at a distance, have bothered to canvass the neighborhood for potential witnesses. Terry notices a surveillance camera above the street. Cappell tells him that it’s unlikely the camera even works. Colson orders Cappell to start knocking on doors while he checks in on any possible security footage. When Colson gets to the office that monitors the cameras, the officer on duty watching them (Carl Palmer) confirms that the camera in question no longer works, as is the case with most of the surveillance equipment in the 6th District. “Why am I not surprised?” Terry sighs. The officer suggests that even though the cameras don’t work, they still serve as a deterrent, adding that even if all the security cameras worked, understaffing would prevent monitoring all of them. Colson asks how many continued to function. The officer guessed that in the 6th District, perhaps 10 to 12. “Out of how many?” Terry inquires. The officer gives him the total of 38. He suggests that Colson talk to the head of IT in Nagin’s office, if he wants to make any progress, but he thanks him for dropping by. He doesn’t get many visitors apparently.

silent Detective Silby (JD Evermore), seen at a distance, have bothered to canvass the neighborhood for potential witnesses. Terry notices a surveillance camera above the street. Cappell tells him that it’s unlikely the camera even works. Colson orders Cappell to start knocking on doors while he checks in on any possible security footage. When Colson gets to the office that monitors the cameras, the officer on duty watching them (Carl Palmer) confirms that the camera in question no longer works, as is the case with most of the surveillance equipment in the 6th District. “Why am I not surprised?” Terry sighs. The officer suggests that even though the cameras don’t work, they still serve as a deterrent, adding that even if all the security cameras worked, understaffing would prevent monitoring all of them. Colson asks how many continued to function. The officer guessed that in the 6th District, perhaps 10 to 12. “Out of how many?” Terry inquires. The officer gives him the total of 38. He suggests that Colson talk to the head of IT in Nagin’s office, if he wants to make any progress, but he thanks him for dropping by. He doesn’t get many visitors apparently.Albert works as part of the team rebuilding GiGi’s for LaDonna. She also allows the Guardians of the Flame to practice there, which they do when the rest of the tribe arrives. LaDonna asks Big Chief Lambreaux how late they

plan to rehearse, hinting that she’s thinking of other activities, though both she and Delmond watch the Indians go through their paces. Antoine arrives home and tells Desiree about Robert’s STD and Cherise’s boyfriend. Batiste admits that he didn’t sign up to be a father figure when he took the job. Sonny stopped for a quick drink at B.J.’s but when he has to take a leak, he finds the bar’s bathroom out of order. He steps outside to relieve himself but gets promptly greeted by the flashing lights of a patrol car. Sonny insists he consumed a single drink, but that doesn’t concern NOPD Capt. Jack Malatesta (Tony Senzamici). “Son, you can flash your titties if you have ‘em. You can lie down in the street in your own vomit, but one thing you cannot do in the City of New Orleans is pull out your pecker and piss on our hallowed ground,” the officer declares as he shuts the patrol car’s door on Sonny. (One of the great pleasures of Treme always has been its dialogue, especially when it allowed itself longer speeches. I don’t know if David Simon, Eric Overmyer or George Pelecanos gets the credit for that line, but I love it.) Shortly after his arrival in lockup. another man (Garrett Kruithof) get shoved in the holding cell, promptly collapsing, asking for help or a doctor and telling Sonny that he needs his inhaler for his asthma. Sonny calls a deputy for help, saying the man needs a doctor. The law enforcement official asks Sonny if he is a doctor, which Sonny obviously replies in the negative. “Then what the fuck do you know about it?” he spits before walking away, leaving the man writhing on the cell floor.

plan to rehearse, hinting that she’s thinking of other activities, though both she and Delmond watch the Indians go through their paces. Antoine arrives home and tells Desiree about Robert’s STD and Cherise’s boyfriend. Batiste admits that he didn’t sign up to be a father figure when he took the job. Sonny stopped for a quick drink at B.J.’s but when he has to take a leak, he finds the bar’s bathroom out of order. He steps outside to relieve himself but gets promptly greeted by the flashing lights of a patrol car. Sonny insists he consumed a single drink, but that doesn’t concern NOPD Capt. Jack Malatesta (Tony Senzamici). “Son, you can flash your titties if you have ‘em. You can lie down in the street in your own vomit, but one thing you cannot do in the City of New Orleans is pull out your pecker and piss on our hallowed ground,” the officer declares as he shuts the patrol car’s door on Sonny. (One of the great pleasures of Treme always has been its dialogue, especially when it allowed itself longer speeches. I don’t know if David Simon, Eric Overmyer or George Pelecanos gets the credit for that line, but I love it.) Shortly after his arrival in lockup. another man (Garrett Kruithof) get shoved in the holding cell, promptly collapsing, asking for help or a doctor and telling Sonny that he needs his inhaler for his asthma. Sonny calls a deputy for help, saying the man needs a doctor. The law enforcement official asks Sonny if he is a doctor, which Sonny obviously replies in the negative. “Then what the fuck do you know about it?” he spits before walking away, leaving the man writhing on the cell floor.Nelson visits Desautel’s on the Avenue, disappointed that his favorite dishes prove M.I.A. Tim Feeny stops by and glad-hands him and Hidalgo pretends he’s enjoying the pork loin he’s consuming. He asks Feeny if “chef” might be available for a brief chat and Feeny says “he” is. Nelson inquires about Janette, but Feeny just mentions the new chef being a great hire from Atlanta. When Feeny asks the woman serving behind the bar about how long Janette has been absent and she tells him about two months. Nelson pushes the rest of his meal aside and finishes his drink. Colson goes to Deputy Chief of Operations Marsden (Terence Rosemore) and demands a transfer, which Marsden refuses. Terry’s anger grows and he tells Marsden that he’s documented all the attempts to screw him over and jack him up, but he’s not going to quit. Marsden suggests that Colson take his pension and retire. He also reminds him that for all the years Colson served in the 6th District, he can’t quite call himself a virgin.

When Toni gets Sonny out of jail the next morning, she senses something happened. Sonny tells him that nothing to him but shares the tale of the neglected asthmatic. He tells her EMTs eventually showed up after he wasn’t breathing and was blue and tried to revive him, but they were too late — the man was dead. Davis brings a box bearing gifts of liquor to Janette for that night’s opening. “How many times will I get to see you open a new place in my lifetime — six, seven tops,” McAlary proclaims. Janette welcomes the present. She can’t obtain credit from any liquor distributors to make running a full bar possible. She offers Davis a free opening night meal, but McAlary opts for a rain check citing his interest in the community meeting concerning closing the live clubs on Rampart in order to make way for the jazz center followed by Trombone Shorty’s big show at the Howlin’ Wolf. Toni makes a date to talk with sheriff’s department Capt. Richard LaFouchette (James DuMont) to learn more about the man, whose name she learned was William Gilday, who died in his department’s cell. LaFouchette shares the list of in-custody deaths, but Gilday’s name doesn’t appear. Toni asks what the hell is going on over there. “It’s jail, Toni. Shit happens,” LaFouchette responds. (It’s always easier to play a villain, but Melissa Leo amazes with her ability to play such a force of good as Toni as spectacularly as Leo throughout the run of Treme. Of course, as with the rest of the talented cast and show itself, she received no Emmy recognition just as she failed ever to be nominated for her great work on Homicide: Life on the Street. Perhaps that Oscar win for The Fighter and her recent Emmy win for her great guest spot on the hysterical Louie takes the sting out, despite entertainment awards being honors and pointless simultaneously. Speaking of Louie, while Dan Ziskie always displays a dry wit as C.J. Liguori, since I started watching Louie late I can’t help but picture C.J. as the Southern lawman who requests Louis C.K. reward him with a kiss on the lips for saving him from some thugs.)